Submitted:

25 December 2023

Posted:

26 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction

II. Background of Soc in Hevs

A. Definition and Significance of SOC

- (1)

- Energy Management: HEVs operate by seamlessly switching between the internal combustion engine and the electric motor, depending on driving conditions and power demands. Accurate SOC estimation is instrumental in determining when to engage the electric motor or the internal combustion engine to ensure optimal energy management [3].

- (2)

- Battery Health and Longevity: Inaccurate SOC estimation can lead to inadequate charging or discharging of the battery, potentially causing overcharging or deep discharging. Both of these scenarios can compromise battery health and significantly reduce its lifespan. Proper SOC management helps maintain battery health and prolong its operational life [5].

- (3)

- Fuel Efficiency: Precise SOC estimation is crucial for maximizing fuel efficiency in HEVs. It ensures that electric power is used effectively during low-load conditions, reducing the reliance on the internal combustion engine and minimizing fuel consumption [6].

- (4)

- Emissions Reduction: HEVs are renowned for their reduced emissions compared to traditional vehicles. Accurate SOC estimation plays a pivotal role in enabling the vehicle to operate in electric-only mode when possible, further reducing emissions and promoting environmental sustainability [9].

B. Challenges in SOC Estimation

- (1)

- Inaccuracies: Traditional methods often result in inaccurate SOC estimates, particularly when the battery's discharge and charge patterns are nonlinear. These inaccuracies can lead to suboptimal vehicle performance, reduced fuel efficiency, and decreased battery utilization [10].

- (2)

- Environmental Variability: SOC estimation is sensitive to environmental factors, especially temperature. Variations in temperature can significantly affect battery performance and, consequently, SOC estimation. Traditional methods may not adequately account for these variations, resulting in estimation errors [14].

- (3)

- Complex Battery Chemistry: HEV batteries employ various chemistries, each with its unique characteristics [17]. Traditional methods may not adapt well to the specific behaviors of different battery types, limiting their versatility.

- (4)

- Dynamic Operating Conditions: HEVs frequently operate in diverse and dynamic conditions, including regenerative braking, fast acceleration, and variations in load. Traditional methods may not accurately capture these dynamic changes in SOC, potentially leading to inaccurate estimations [19].

III. Machine Learning for SOC Estimation in HEVs

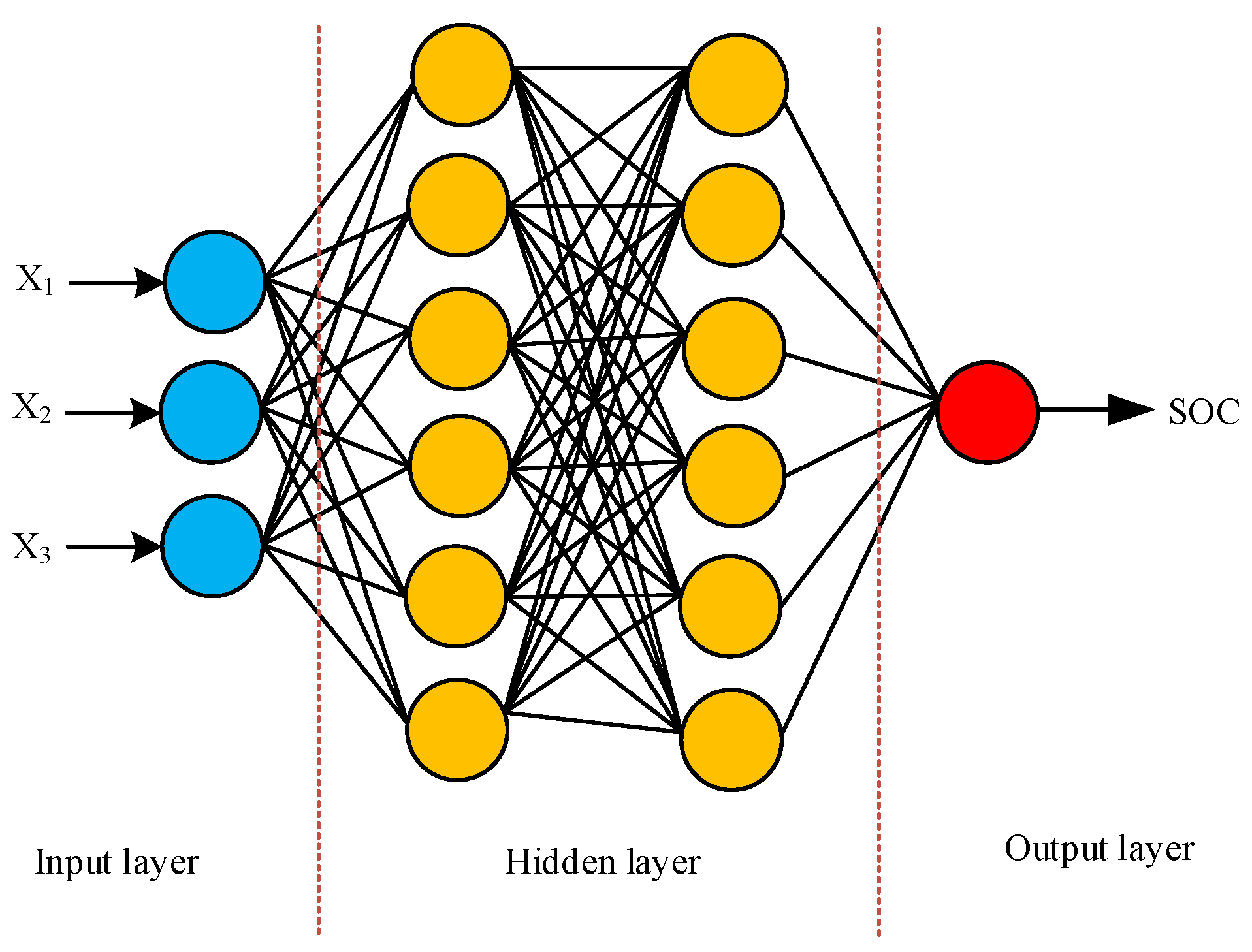

A. The Essence of Machine Learning in SOC Estimation

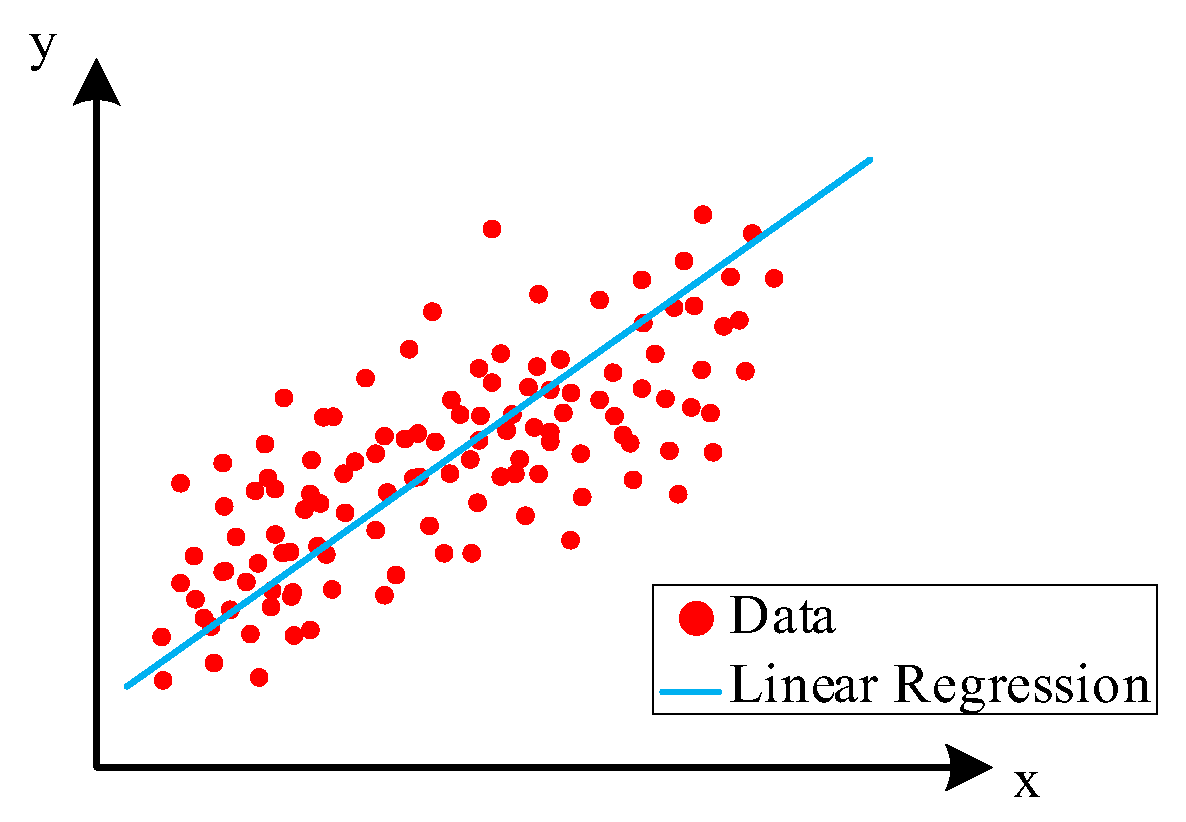

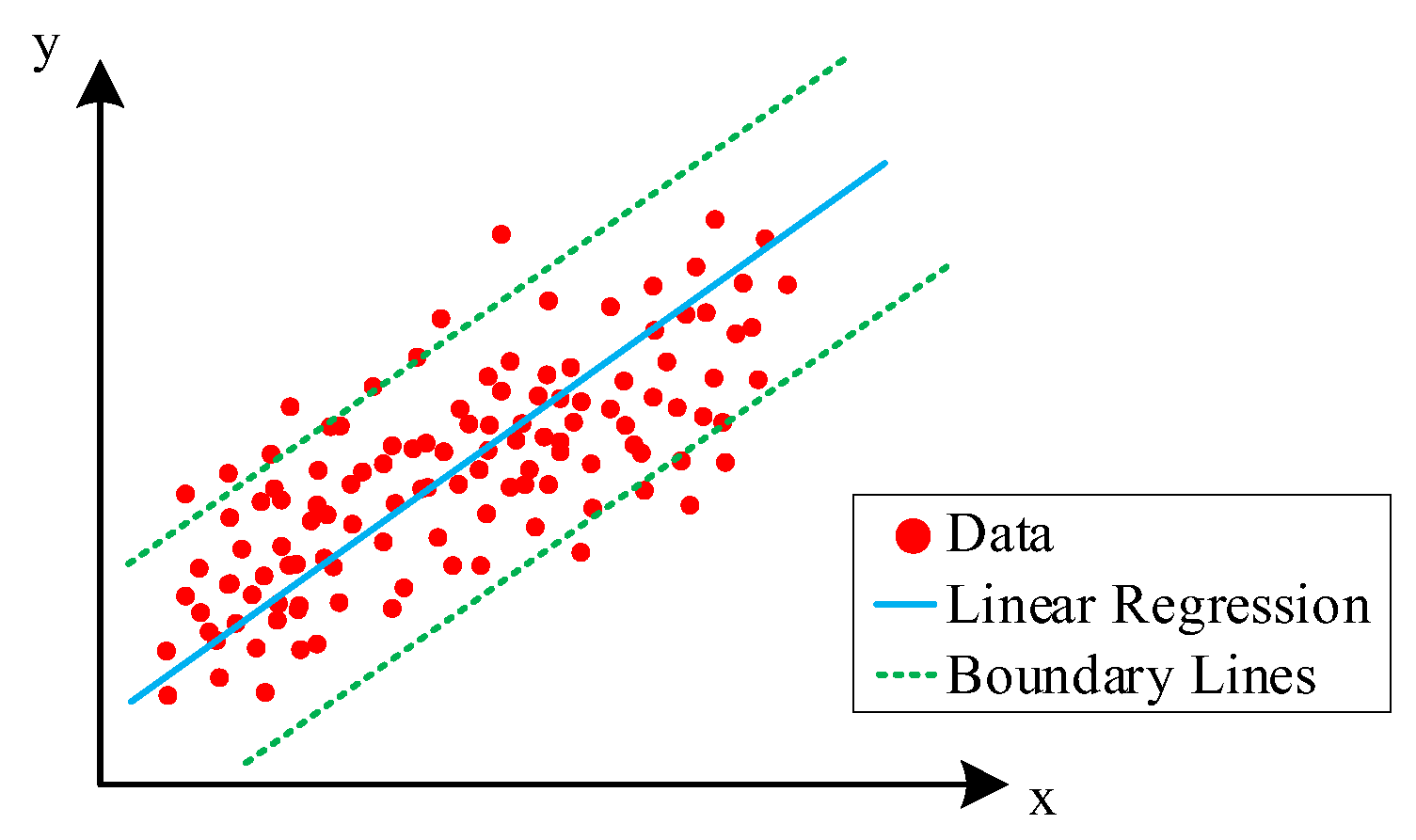

B. The Significance of Regression Models in SOC Estimation

C. Evaluation Metrics

| Ref. | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| [36] | Nonlinear Mapping | Complexity and Overfitting |

| Highly Adaptive | Data Requirement | |

| [37] | Feature Learning | Computational Intensity |

| Ability to Model Interactions | Difficulty in Interpretability | |

| [38] | Parallel Processing | Hyperparameter Tuning Complexity |

| Robustness to Noisy Data | Dependency on Quality of Data | |

| Capacity for Representation Learning | Vulnerability to Outliers | |

| Adaptation to Changes | Limited Sample Efficiency | |

| [39] | Integration of Temporal Information | Potential for Vanishing or Exploding Gradients |

| [40] | Ability to Handle Large Datasets | Dependency on Initialization |

| [41] | End-to-End Learning | Lack of Uncertainty Estimation |

| [42] | Versatility | Ethical and Bias Concerns |

| [43] | Flexibility in Model Architecture | Limited Interpretability |

| [44] | Automatic Feature Extraction | Data Preprocessing Challenges |

| [45] | Adaptability to Dynamic Environments | Difficulty with Non-Continuous Variables |

| [46] | Capability for Transfer Learning | Lack of Guarantees on Convergence |

| [47] | Integration with Temporal Dependencies | Limited Handling of Missing Data |

| [48] | Robustness to Irrelevant Features. | Dependency on Batch Size |

IV. Conclusion

References

- Mohammed, A.S.; Atnaw, S.M.; Salau, A.O.; Eneh, J.N. Review of optimal sizing and power management strategies for fuel cell/battery/super capacitor hybrid electric vehicles. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 2213–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yao, M.; Sun, X. An Overview of Modelling and Energy Management Strategies for Hybrid Electric Vehicles. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5947–5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousaei, A.; Gheisarnejad, M.; Khooban, M.H. Challenges and opportunities of FACTS devices interacting with electric vehicles in distribution networks: A technological review. J. Energy Storage 2023, 73, 108860–108860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Tian, S.; Lin, X. Recent Advances and Applications of AI-Based Mathematical Modeling in Predictive Control of Hybrid Electric Vehicle Energy Management in China. Electronics 2023, 12, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Fu, J.; Yang, H.; Xie, M.; Liu, J. An energy management strategy for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles based on deep learning and improved model predictive control. Energy 2023, 269, 126772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilberforce, T.; Anser, A.; Swamy, J.A.; Opoku, R. An investigation into hybrid energy storage system control and power distribution for hybrid electric vehicles. Energy 2023, 279, 127804–127804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, M.Y.; Shaltout, M.L.; Hegazi, H.A. Multi-objective optimum energy management strategies for parallel hybrid electric vehicles: A comparative study. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 277, 116683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousaei, A.; Rostami, N.; Sharifian, M.B.B. Design a robust and optimal fuzzy logic controller to stabilize the speed of an electric vehicle in the presence of uncertainties and external disturbances. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control. 2023, 46, 482–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolucci, L.; Cennamo, E.; Cordiner, S.; Mulone, V.; Pasqualini, F.; Boot, M.A. Digital twin of a hydrogen Fuel Cell Hybrid Electric Vehicle: Effect of the control strategy on energy efficiency. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2022, 48, 20971–20985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z. Energy management for hybrid electric vehicles based on imitation reinforcement learning. Energy 2023, 263, 125890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousaei, A.; Naderi, Y. Optimal Predictive Torque Distribution Control System to Enhance Stability and Energy Efficiency in Electric Vehicles. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hu, H.; Tan, J.; Lu, C.; Xuan, D. Deep reinforcement learning based energy management strategy for range extend fuel cell hybrid electric vehicle. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 277, 116678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Li, Q.; He, H. Cooperative energy management and eco-driving of plug-in hybrid electric vehicle via multi-agent reinforcement learning. Appl. Energy 2023, 332, 120563–120563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Ruan, J.; Cui, H.; Zhang, B.; Li, T.; Zhang, K. The application of machine learning based energy management strategy in multi-mode plug-in hybrid electric vehicle, part I: Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient algorithm design for hybrid mode. Energy 2023, 262, 125084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, P.; Karimi, H.R.; Xie, H.-H.; Chen, F.; Huang, C.; Yang, S. A deep reinforcement learning approach to energy management control with connected information for hybrid electric vehicles. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 123, 106239–106239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, B. A comparative study of 13 deep reinforcement learning based energy management methods for a hybrid electric vehicle. Energy 2023, 266, 126497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, P.M.; Daniela; Bauer, P. ; Mammetti, M.; Bruno, J.C. Deep learning in the development of energy Management strategies of hybrid electric Vehicles: A hybrid modeling approach. Appl. Energy 2023, 329, 120231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Ruan, S.; Han, L.; Liu, H.; Guo, L.; Chen, X. Reinforcement learning-based real-time intelligent energy management for hybrid electric vehicles in a model predictive control framework. Energy 2023, 270, 126971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arash Mousaei and, H. Peng, A new control method for the steadiness of electric vehicles with 2-motor in rear and front wheels. Int. J. Emerg. Electr. Power Syst. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, A.E.-D. Extended-deep Q-network: A functional reinforcement learning-based energy management strategy for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2023, 43, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zhang, J.; Pilla, S.; Rao, A.M.; Xu, B. Application of a new type of lithium-sulfur battery and reinforcement learning in plug-in hybrid electric vehicle energy management. J. Energy Storage 2023, 59, 106546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Hong, J.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J. Energy management strategy of a novel parallel electric-hydraulic hybrid electric vehicle based on deep reinforcement learning and entropy evaluation. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 403, 136800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Han, L.; Li, R.; Wei, Z.; Liu, H.; Xiang, C. Multiobjective Intelligent Energy Management for Hybrid Electric Vehicles Based on Multiagent Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 9, 4294–4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Han, L.; Li, R.; Wei, Z.; Liu, H.; Xiang, C. Multiobjective Intelligent Energy Management for Hybrid Electric Vehicles Based on Multiagent Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 9, 4294–4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, Q.; Tang, A.; Zhang, Z. A comparative study of state of charge estimation methods of ultracapacitors for electric vehicles considering temperature characteristics. J. Energy Storage 2023, 63, 106908–106908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, J.; et al. The application of machine learning-based energy management strategy in a multi-mode plug-in hybrid electric vehicle, part II: Deep deterministic policy gradient algorithm design for electric mode. Energy 2023, 269, 126792–126792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Peng, J.; Dong, H.; Tan, H.; Ding, F. Hierarchical reinforcement learning based energy management strategy of plug-in hybrid electric vehicle for ecological car-following process. Appl. Energy 2023, 333, 120599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, J.; Qing, X.; Wang, B.; Li, K. Deep Reinforcement Learning-based Hierarchical Energy Control Strategy of a Platoon of Connected Hybrid Electric Vehicles through Cloud Platform. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 10, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Tao, F.; Fu, Z.; Sun, H. Battery-degradation-involved energy management strategy based on deep reinforcement learning for fuel cell/battery/ultracapacitor hybrid electric vehicle. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 220, 109235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Guo, G.; Tang, B.; Hu, G.; Tang, X.; Li, T. Data-driven transferred energy management strategy for hybrid electric vehicles via deep reinforcement learning. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 2680–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Li, Z.; Outbib, R.; Gao, F. Function approximation reinforcement learning of energy management with the fuzzy REINFORCE for fuel cell hybrid electric vehicles. Energy AI 2023, 13, 100246–100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhang, S.; Liu, B. A hybrid algorithm combining data-driven and simulation-based reinforcement learning approaches to energy management of hybrid electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 10, 1257–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhar, T.; et al. Electric Vehicle Charging System in the Smart Grid Using Different Machine Learning Methods. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosuru, V.S.R.; Venkitaraman, A.K. A Smart Battery Management System for Electric Vehicles Using Deep Learning-Based Sensor Fault Detection. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Huo, Q.; Wang, W.; Zhang, T. Voltage-temperature aware thermal runaway alarming framework for electric vehicles via deep learning with attention mechanism in time-frequency domain. Energy 2023, 278, 127747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, D.; Wang, Y.; Hua, W.; Strbac, G. Reinforcement learning for electric vehicle applications in power systems:A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 173, 113052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, A.; Chabaan, R.C. Metaheruistic Optimization Based Ensemble Machine Learning Model for Designing Detection Coil with Prediction of Electric Vehicle Charging Time. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zeng, P.; Cui, S.; Song, C. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Charging Scheduling of Electric Vehicles Considering Distribution Network Voltage Stability. Sensors 2023, 23, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Tao, F.; Fu, Z.; Gao, A.; Sun, H. Driving-Behavior-Aware Optimal Energy Management Strategy for Multi-Source Fuel Cell Hybrid Electric Vehicles Based on Adaptive Soft Deep-Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 4127–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, N.; Cui, W.; Shi, Y. Deep Reinforcement Learning Based PHEV Energy Management with Co-Recognition for Traffic Condition and Driving Style. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 8, 3026–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji, B.P. A Multivariable Output Neural Network Approach for Simulation of Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle Fuel Consumption. Green Energy Intell. Transp. 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millo, F.; Rolando, L.; Tresca, L.; Pulvirenti, L. Development of a neural network-based energy management system for a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle. Transp. Eng. 2023, 11, 100156–100156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Zhang, Z.; Liao, H.; Pan, J.; Xiao, Y. Prediction of cold start emissions for hybrid electric vehicles based on genetic algorithms and neural networks. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 420, 138403–138403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, F.; Li, A.; Shi, J. Real-Time Energy Performance Benchmarking of Electric Vehicle Air Conditioning Systems Using Adaptive Neural Network and Gaussian Process Regression. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Mokhtari Mehmandoosti and F. Kowsary, Artificial neural network-based multi-objective optimization of cooling of lithium-ion batteries used in electric vehicles utilizing pulsating coolant flow. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 219, 119385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, Z.; Li, L. An Energy Management Strategy for Hybrid Energy Storage System Based on Reinforcement Learning. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji, B.P.; Kabir, G. A feedforward deep neural network for predicting the state-of-charge of lithium-ion battery in electric vehicles. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 8, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji, B.P. Electric vehicles survey and a multifunctional artificial neural network for predicting energy consumption in all-electric vehicles. Results Eng. 2023, 19, 101283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| [26] | Interpretability | Linearity Assumption |

| Simplicity | Sensitivity to Outliers | |

| Real-time Predictions | Limited Complexity | |

| Adaptability | Overfitting/Underfitting | |

| [27] | Data Utilization | Assumption of Independence |

| [28] | Resource Efficiency | Limited to Numeric Data |

| Versatility | Limited in Handling Non-Gaussian Residuals | |

| Cost-Effectiveness | Data Quality Dependency | |

| [29] | Ease of Implementation | Static Nature |

| [30] | Versatile in Variable Types | Multicollinearity |

| [31] | Model Transparency | Limited for Time-Series Data |

| [32] | Assumes Homoscedasticity | Dependence on Training Data |

| [33] | Efficient for Large Datasets | Assumption of Normality |

| [34] | Facilitates Hypothesis Testing | Limited for Complex Systems |

| [35] | Ease of Model Interpretation | Limited Feature Engineering |

| [36] | Useful for Exploratory Analysis | Limited in Handling Missing Data |

| [37] | Robust to Irrelevant Features | Difficulty with Non-Continuous Variables |

| [38] | Facilitates Model Comparison | Vulnerability to Changes in Data Distribution |

| Ref. | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| [26] | Nonlinearity Handling | Computational Intensity |

| [27] | High-Dimensional Spaces | Model Complexity |

| [28] | Kernel Trick | Interpretability |

| [29] | Robustness to Outliers | Memory Usage |

| [30] | Global Optimization | Sensitivity to Noise |

| [31] | Flexibility in Kernel Selection | Black-Box Nature |

| [32] | Tuning Parameters | Data Scaling Importance |

| [33] | Effective in Small Sample Sizes | Large Parameter Search Space |

| [34] | Prediction Accuracy | Limited Handling of Categorical Data |

| [35] | Generalization Capability | Overfitting Risk |

| [36] | Resource Efficiency | Resource Requirements |

| [37] | Ease of Model Comparison | Limited Interpretability |

| [38] | Adaptability to Various Distributions | Data Preprocessing Challenges |

| [39] | Robust to Irrelevant Features | Limited Handling of Time-Series Data |

| [40] | Facilitates Hypothesis Testing | Assumption of Homoscedasticity |

| [41] | Versatility in Problem Types | Dependency on Kernel Choice |

| [42] | Ease of Hyperparameter Tuning | Limited Handling of Missing Data |

| [43] | Robustness to Nonlinearities | Difficulty with Non-Continuous Variables |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).