1. Introduction

Lumbar disc herniation is a prevalent lumbar disease, often manifesting as sciatica, low back pain, and neurological dysfunction [

1]. In cases where conservative treatment fails, surgical intervention becomes imperative [

2]. Historically, classical open discectomy, largely supplanted by microdiscectomy [

3], was the standard treatment. However, in recent years, minimally invasive surgery has gained favor as the preferred surgical option for this condition, owing to its numerous advantages including reduced muscle injury, lower blood loss, minimized scarring, and shorter hospital stays [

4,

5,

6].

Fully endoscopic techniques have become increasingly popular worldwide for its efficacy in treating lumbar disc herniation. This technique has evolved into two primary categories: the uniportal and the biportal (UBE) approaches [

7,

8]. Recent studies comparing these two methods have established that both are safe and effective in treating lumbar disc herniations [

8,

9,

10]. Advances in medical technology and surgical tools over the past few years have positioned endoscopy as a viable alternative to traditional surgical methods, with some considering it the new gold standard in the treatment of lumbar degenerative diseases. Notably, uniportal endoscopy, while effective, has a steep learning curve, making its adoption challenging for experienced spine surgeons [

11]. This is one reason to a resurgence of interest in biportal techniques, which align more closely with the practices of traditional spine surgeons and offer additional advantages, such as the use of standard surgical instruments, thereby impacting the cost of procedures as well.

Despite these advancements, endoscopic spine surgery, like other minimally invasive techniques, conventionally requires the use of a C-arm for guidance, presenting a significant risk of radiation exposure, particularly for the surgeon and operating staff [

12]. To mitigate this issue, innovative techniques of intraoperative navigation have been developed, though these have predominantly focused on the uniportal approach [

13,

14]. Moreover, the current solutions offered by endoscopic equipment manufacturers largely revolve around investing in additional, integrated navigation systems for the uniportal sets, further escalating the costs of procedures. Building on these developments, our article proposes the use of intraoperative CT and intraoperative navigation to optimize the trajectory for endoscope, instrument insertion, and decompression in biportal endoscopy. This approach aims to eliminate the need for C-arm guidance, reducing radiation exposure and enhancing the safety of the UBE technique for lumbar disc herniation (LDH).

The study outlined in this article was conducted with the approval of our institute's ethics committee (No. 459), and all necessary patient consents were obtained. Our findings offer a pragmatic and economically viable solution, potentially transforming the landscape of minimally invasive spine surgery by making advanced techniques more accessible and safer.

2. Case 24 years old male, L4/5 lumbar disc herniation

2.1. Patient history.

A 24-year-old man with low back and bilateral leg pain with gait disturbance was referred to our hospital. He had have conservative treatment for 12 months in another hospital before admission. However, the conservative treatment did not work for him.

2.2. Physical examination.

The patient had low back pain (VAS 4/10) and bilateral leg pain (VAS 8/10). He had muscle waekness of bilateral legs (extensor hullusis longs 4 4) and numbness of bilateral lower leg but able to can walk without any support. On examination, he had no hyperreflexia of bilateral legs. He had no urinary and bowel incontinence.

2.3. Preoperative imaging.

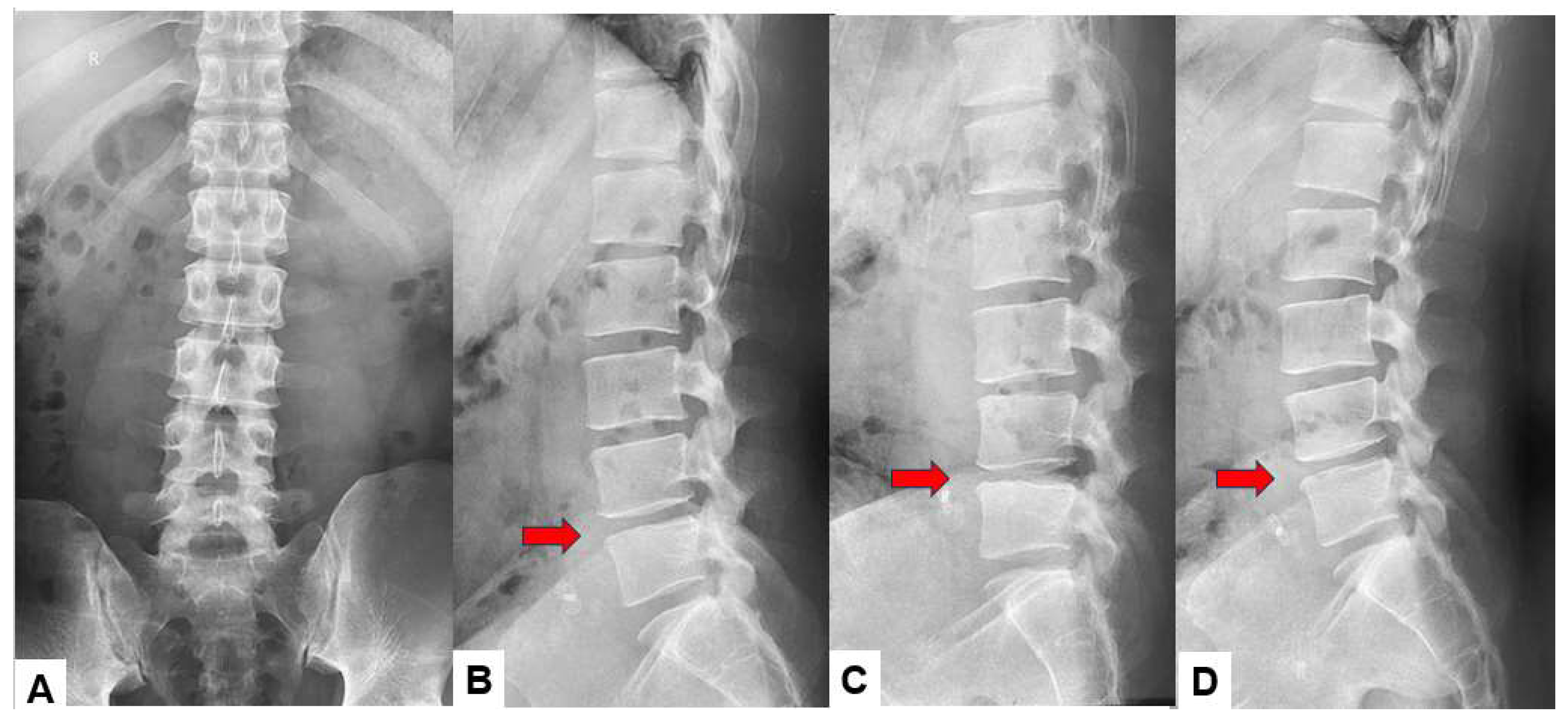

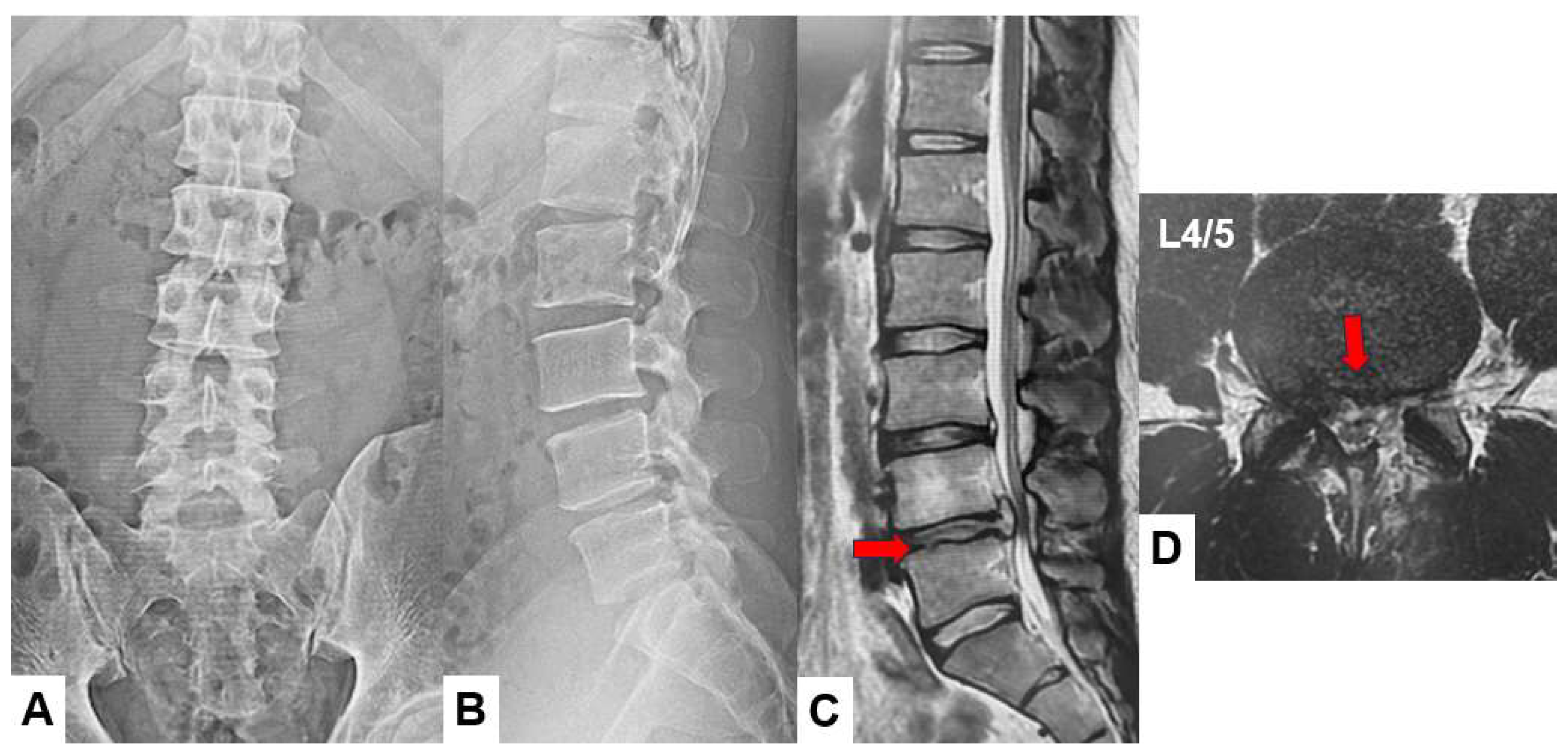

Preoperative anteroposterior lumbar radiogram indicates slight instability at L4/5 level (

Figure 1). Preoperative lumbar 3D CT showed lumbar scoliosis due to disc herniation. Preoperative MRI indicated L4/5 central disc herniation and compressing bilateral L5 nerve roots (

Figure 2).

2.4. Surgery.

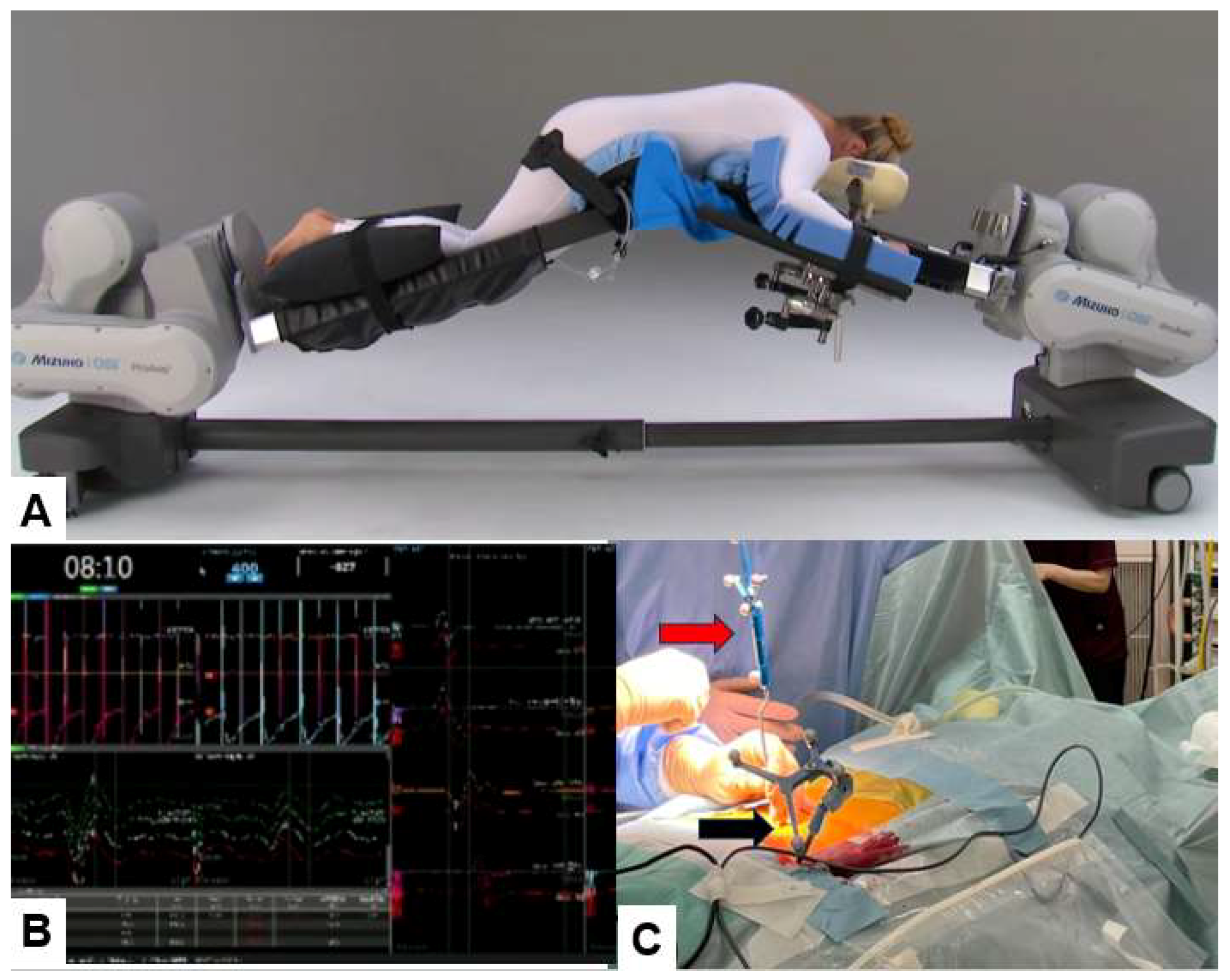

2.4.1. Patient positioning, neuromonitoring, and navigation

Patient is in a prone position on a full carbon operating table under general anesthesia. We utinely perform neuromonitoring using a multi-modality intraoperative monitoring system. For a muscle of which the innervated nerve is decompressed adequately, the amplitude of the MCV usually increases. A navigation reference frame (RF) is placed percutaneously into the contralateral side sacroiliac joint. Then intraoperative CT scan images with a mobile CT scanner (O-arm) is obtained. After that every instrument is registered such as the navigated pointer, dilater and high-speed burr (

Figure 3).

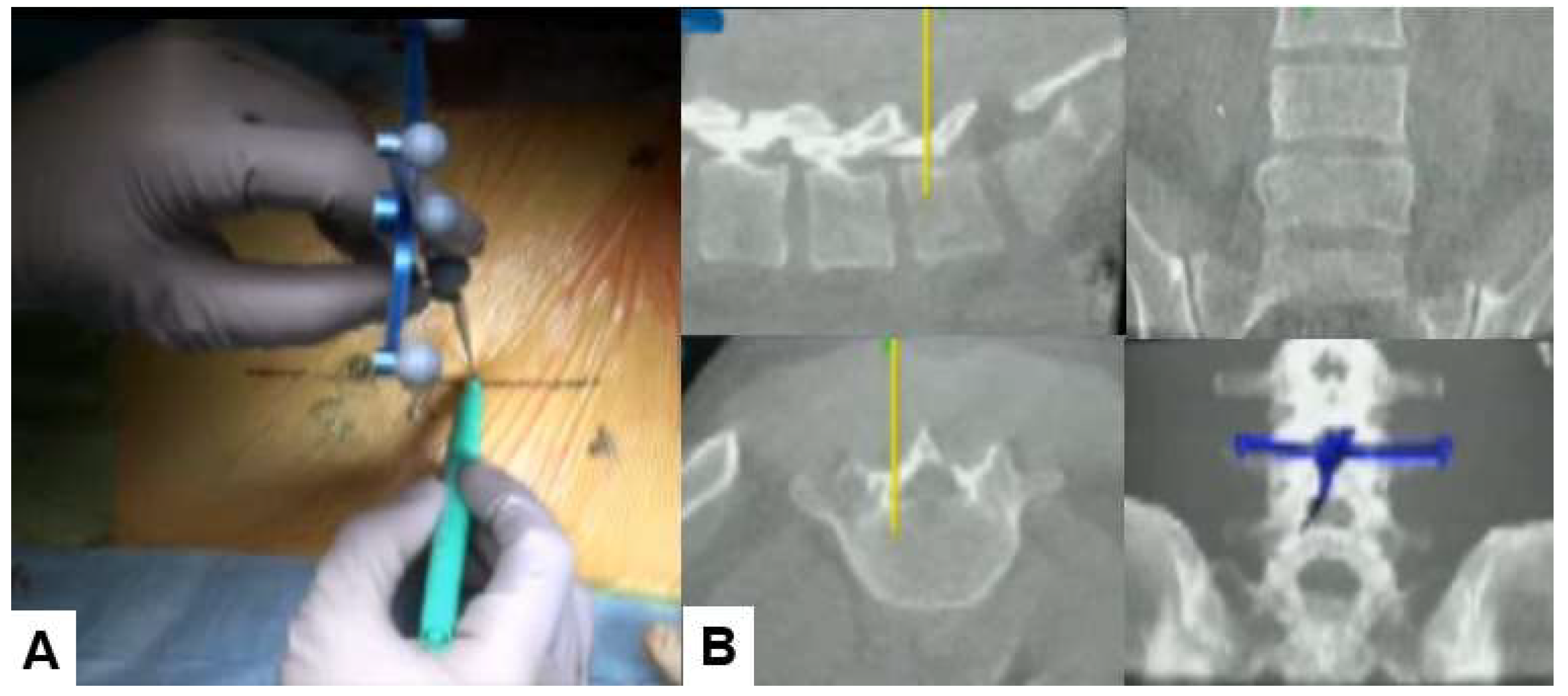

2.4.2. Skin incision and bony resection

With the help of a navigated pointer, two longitudibnal 6-7mm skin incision are marked. First line is medial pedicle line of L4-L5. One skin incision is for surgical instruments (just paralle to upper endoplate of L5,

Figure 4) and the other is for endoscopy (2 cm cranial of the first one). The working space at intelaminar spce is made by navigated first dilater. Then the endoscpy is inserted on the left side and the monopolar on the right side. The soft tissue around interlaminar space is coagulated with the monopolar and lateral edge of L5 lamina is resected with the navigated high speed burr, the ultrasonic bone cutter, and and Kerrison rongeurs. Before using the navigated instruments, the surgeon should check the accuracy of navigation because sometimes the reference frame shifts.. During bony resection, the navigated probe is used to confirm the location (

Figure 5).

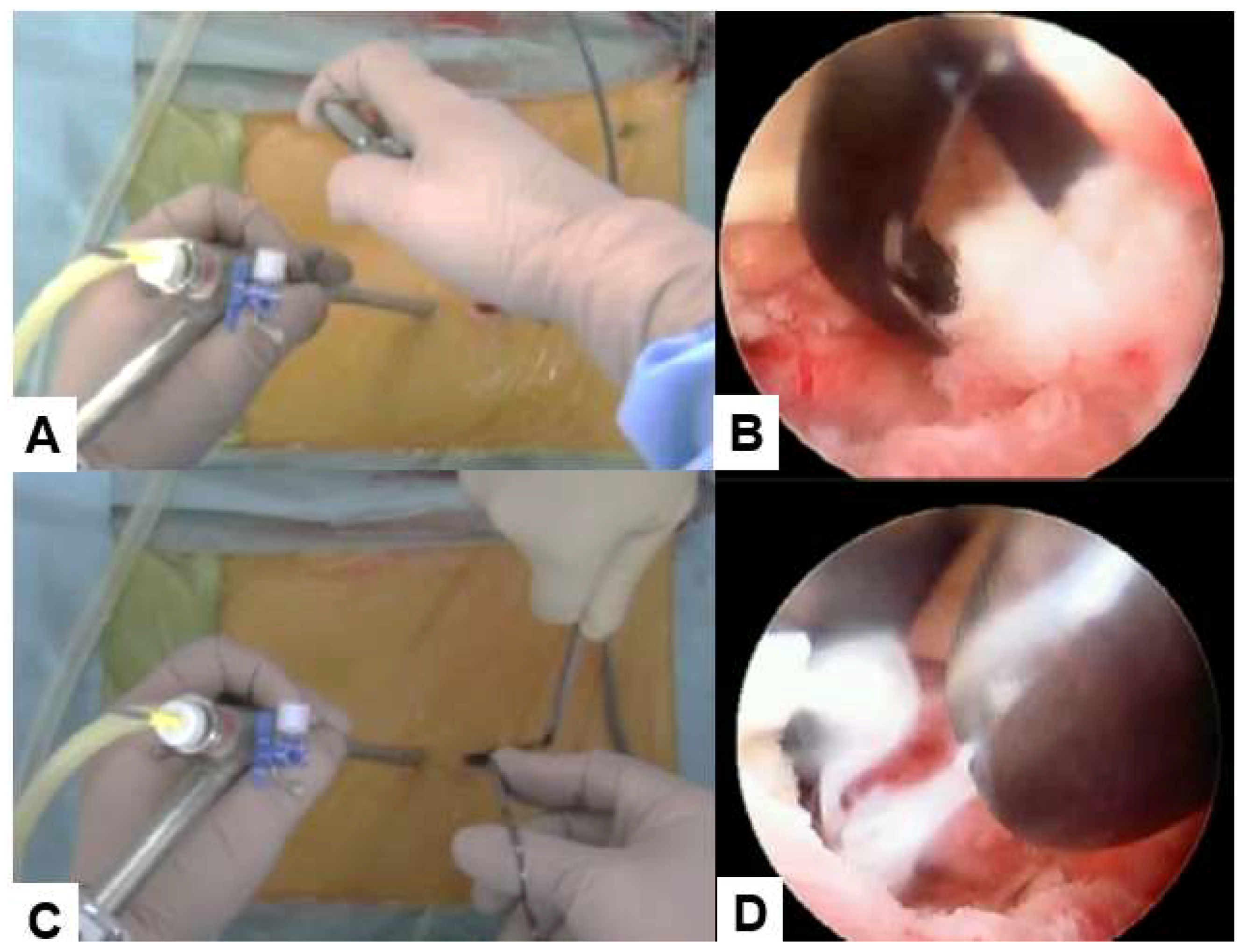

2.4.3. Ligamentum flavum resection and discectomy

After adequate bone resection, the ligamentuum flavum is removed with Kerrison and the nerve root is identified. For clear image, bleeding is coagulaed every step. The nerve is rectacted medially with the angled nerve retracter. Outer annulus is cut with a special small knife and the herniated disc is removed with pituitary forceps and a bole probe. After irrigation with saline water to remove the debris, a wound suction tube is placed.

Figure 6.

Ligamentum flavum resection and discectomy, A, B: Ligamentum flavum resection with Kerrison rongeurs, C, D: Discectomy with pituitary forceps.

Figure 6.

Ligamentum flavum resection and discectomy, A, B: Ligamentum flavum resection with Kerrison rongeurs, C, D: Discectomy with pituitary forceps.

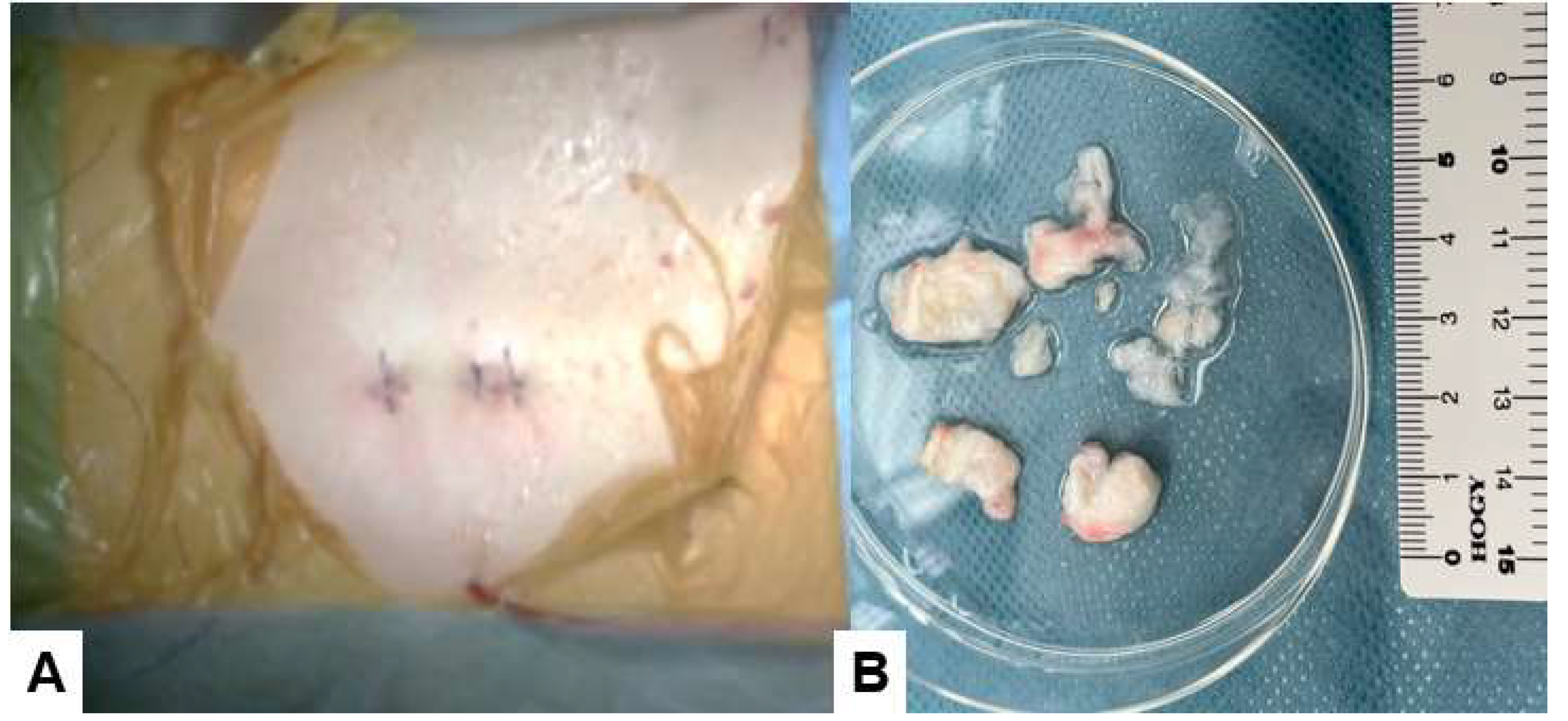

2.4.4. Skin closure

Finally, the skin is closed with an absorbable suture. Postoperatively, the drain is removed 24 hours after surgery.

Figure 7B shows the removed disc material.

2.5. Postoperative images.

Postoperative radiogram and CT showed minimum bony resection. Postoperative MRI showed a good decompression of the dural sac and nerve roots. The bony resection area was adequate (

Figure 8).

2.6. One year follow-up.

The patient recovered fully well at two months follow-up. The patient has no ADL disturbance and no herniated disc recurrence on final follow-up at one year.

4. Discussion

4.1. History of endoscopic discectomy

Endoscopic discectomy has become a standard surgical option for various disc herniation, which is one of the minimally invasive spinal surgeries (MISS). Endoscopic discectomy infers MISS with a percutaneous approach and the utilization of a surgical endoscope. The original model for this 'percutaneous endoscopic approach' was the posterolateral percutaneous discectomy. In the mid-1970s, Kambin et al. were among the first to introduce the idea of percutaneous disc decompression through nucleotomy using Craig's cannula in a posterolateral approach in 136 patients with a clinical success rate of 72% [

15]. In 1975, Hijikata et al. independently published a similar technique for posterolateral percutaneous discectomy [

16]. After then, the percutaneous endospic lumbar discectomy (PELD) technique was first introduced for contained lumbar disc herniation via the triangular operative region known as Kambin's triangle, in which there are no neurovascular structures [

17]. However, the primary surgical focus was limited to the intradiscal region surrounding the annular tear [

18].

Since the mid-1990s, there has been a shift toward a genuine transforaminal approach, incorporating the use of a working channel endoscope, which was allowed to pass completely through the intervertebral foramen into the epidural space instead of just going through the safe working zone and into the disc [

19]. This advancement enabled surgeons to directly decompress extruded disc fragments with the benefit of direct endoscopic visualization. From 2000, Kambin and Yeung independently pioneered the concept of targeted endoscopic discectomy through the transforaminal approach with advanced wide-angled endoscopy for various kinds of herniation [

20,

21]. At that time, a specific discectomy technique was developed using an interlaminar endoscopic interlaminar discectomy (PEID) in patients with L5-S1 level LDH with high iliac crests [

22]. Recently,PELD and PEID had emerged as the two most extensively used procedures in endoscopic spinal surgery [

23].

4.2. Advantages and disadvantages of UBE compared with uniportal technique.

The use of biportal endoscopy for spinal surgery was first reported in 1996 regarded as a novel method [

24]. This technique utilized two portals on one side and used a simple endoscopic system similar to a knee arthroscopy. By integrating an observation channel and an operation channel, the instrument gained a broader range of movement, thereby enhancing decompression range and exploration capability. UBE technology offers several distinctive advantages when compared with PELD/PEID technology. A significant advantage of UBE over PELD/PEID lied in its utilization of two channels instead of pipes, providing enhanced operational flexibility with freely adjustable angles. Substantial evidence indicated that UBE exhibited a relatively short learning curve, ensuring the safe performance of the procedure [

25,

26]. Moreover, when compared with the PELD, UBE closely resembled open discectomy, a method familiar to spinal surgeons.

Among minimally invasive procedures, UBE and PELD had demonstrated comparable therapeutic effectiveness to conventional open surgeries in alleviating symptoms and enhancing functional abilities in LDH patients with less trauma and fast recovery [

27,

28]. But recent evidence indicated that patients underwent PELD may face a high risk of recurrence and revision rates in comparison to those treated with traditional open surgery and microdiscectomy [

29]. Notably, the advancement of MISS in recent years had brought about the introduction of UBE with a lower LDH recurrence during follow-up compared to PLED [

30].

Despite with those advantages, there are several disadvantages for UBE compared with PELD. UBE showed comparative efficacies in improving the visual analogue scale of leg and back, or the Oswestry disability index scores with PLED [

30]. However, the levels of creatine phosphokinase and C-reactive protein in the UBE group were a little higher than those in the PELD groups. When compared for muscle damege, the high-intensity cross-sectional area of paraspinal muscle in the UBE group (mean, 481.15 mm²) was larger than that in the PELD group (mean, 97.65 mm

2) using T2-weighted axial magnetic resonance imaging {31]. In addition, there were difference of radiation exposures (dose area product [DAP]) and fluoroscopy times (seconds) between biportal and un-portal techniques. Abdullah Merter et al. reported that the highest DAP was seen in the PELD group followed by the UBE (2.46 Gy/cm

2 VS 1.39 Gy/cm

2), and the maximum mean duration of fluoroscopy usage time was 34.9 seconds in the PELD group, 19.3 seconds in the UBED group (P<0.001) [

32].

4.3. Various method of endoscopic technique without C-arm

Currently, the enthusiasm for minimally invasive interventions was growing steadily in spine surgery, and the puncture procedure in endoscopic technique was conducted under the guidance of a C-arm. As the invasiveness decreases in spine surgery, the need for C-arm increases. While radiation doesn't pose a significant risk for the treated patient, it does present a cumulative risk for the surgeon and the operating team, because they were repeatedly exposed to this radiation throughout their careers [

33]. Moreover, frequent adjustments of the puncture may lead to heightened soft tissue damage and prolonged surgical time. To avoid the negative effects, it is important to adopt various technique without C-arm.

There are several attempts to perform UBE without C-arm, such as ultrasonic technique, Robot, augmented reality (AR), and electromagnetic system. Yan-Bin Liu et al. evaluated the precision of utilizing the US V Nav technique for guiding transforaminal puncture through the fusion of real-time ultrasound and CT images [

34]. Three-dimensional CT was employed to visualize bone tissue, while real-time and non-radiation ultrasound were utilized to showcase and precisely locate the foramen. In 2021, Mengran Jin et al. illustrated that the TiRobot system, when coupled with intraoperative CT scanning, significantly enhanced puncture accuracy and reduced radiation exposure for both surgical staff and patients during PELD surgeries [

35]. Xin Huang et al. developed an augmented reality (AR) surgical navigation (ARSN) system which markedly reduced the number of punctures and excessive use of C-arm in endoscopic surgery [

36]. Moreover, some surgeons presented a novel real-time 3D electromagnetic navigation (EMN) system for percutaneous full-endoscopic foraminoplasty and discectomy.[

37,

38]

4.4. Advantages of our new technique

Previous studies had described successful navigation-assisted surgery in PELD without the use of a C-arm[

39]. However, there is no report which describes feasibility, safety, and accuracy of O-arm-based navigation in UBE. Building on these developments, we proposed this case using the standard intraoperative navigation, typically available in most neurosurgery and spine surgery departments, to optimize the trajectory for endoscope and instrument insertion and decompression in biportal endoscopy. This technique can eliminate the need for C-arm guidance, reducing radiation exposure and enhancing the safety of bone resection with navigation. There is a significant reduction with O-arm navigation in the operation time, cannula and tools placement time and learning curve of UBE. What's more important was that it can decreased the complications caused by inaccurate or improper punctures or decompression, such as leakage of cerebrospinal fluid and irreversible dura or nerve root damage [40-43].

Overall, the technique demonstrated that the O-arm-based navigation system can assist surgeons in overcoming the technical challenges associated with puncture and decompression phases, consequently reducing the procedural complexities of UBE.

4.5. Limitation

Several limitations should be noted in this technical report. First, due to the relatively small number of experienced cases, an additional number of cases will need to be studied to arrive at a solid conclusion. Second, a multicentre study with a larger sample size, longer follow-up is needed for further validation. Third, a study to compare O-arm navigation with other computer navigation systems will be helpful in fine tuning the C-arm free endoscopic approach.

5. Conclusions

The new unilateral biportal endoscopic (UBE) technique under navigation guidance is useful technique for lumbar disc herniation. This innovative technique proved to be safe, accurate, and efficient for the treatment of lumbar intervertebral disc herniation. It has reshaped the learning curve of UBE, mitigated the surgical complexity, and minimized radiation exposure for surgeons.

Author Contributions

M.T.: conceptualization, supervision; P.M. and K.L.: writing—review and editing; H.X: writing—original draft preparation, methodology; C.R., Y.F., T.T., S.A.、A.M.: data collection; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received funding from Japan Organization of Occupational Health and Safety.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional review boards at Okayama Rosai Hospital (Approval No. 459, Dec 1, 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Okayama Spine Group.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Zhang AS, Xu A, Ansari K, Hardacker K, Anderson G, Alsoof D, Daniels AH. Lumbar Disc Herniation: Diagnosis and Management. Am J Med. 2023, 136, 645–651.

- Schoenfeld AJ, Weiner BK. Treatment of lumbar disc herniation: Evidence-based practice. Int J Gen Med. 2010, 3, 209–14.

- Koebbe CJ, Maroon JC, Abla A, El-Kadi H, Bost J. Lumbar microdiscectomy: a historical perspective and current technical considerations. Neurosurg Focus. 2002, 13, E3.

- Tan Y, Tanaka M, Sonawane S, Uotani K, Oda Y, Fujiwara Y, Arataki S, Yamauchi T, Takigawa T, Ito Y. Comparison of Simultaneous Single-Position Oblique Lumbar Interbody Fusion and Percutaneous Pedicle Screw Fixation with Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion Using O-arm Navigated Technique for Lumbar Degenerative Diseases. J Clin Med. 2021, 10, 4938.

- Liu X, Yuan S, Tian Y, Wang L, Gong L, Zheng Y, Li J. Comparison of percutaneous endoscopic transforaminal discectomy, microendoscopic discectomy, and microdiscectomy for symptomatic lumbar disc herniation: minimum 2-year follow-up results. J Neurosurg Spine. 2018, 28, 317–325. [CrossRef]

- Ruan W, Feng F, Liu Z, Xie J, Cai L, Ping A. Comparison of percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy versus open lumbar microdiscectomy for lumbar disc herniation: A meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2016, 31, 86–92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li YS, Chen CM, Hsu CJ, Yao ZK. Complications of Unilateral Biportal Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy: A Systematic Review. World Neurosurg. 2022, 168, 359–368. [CrossRef]

- He BL, Zhu ZC, Lin LQ, Sun JF, Huang YH, Meng C, Sun Y, Zhang GC. Comparison of biportal endoscopic technique and uniportal endoscopic technique in Unilateral Laminectomy for Bilateral Decomprssion (ULBD) for lumbar spinal stenosis. Asian J Surg. 2023, S1015-9584(23)00738-8.

- Heo DH, Son SK, Eum JH, Park CK. Fully endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion using a percutaneous unilateral biportal endoscopic technique: technical note and preliminary clinical results. Neurosurg Focus. 2017, 43, E8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.-C.; Shim, H.-K.; Hwang, J.-S.; Shin, S.H.; Lee, D.C.; Jung, H.H.; Park, H.A.; Park, C.-K. Comparison of Surgical Invasiveness Between Microdiscectomy and 3 Different Endoscopic Discectomy Techniques for Lumbar Disc Herniation. World Neurosurg. 2018, 116, e750–e758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewandrowski KU, Telfeian AE, Hellinger S, Jorge Felipe Ramírez León, Paulo Sérgio Teixeira de Carvalho, Ramos MRF, Kim HS, Hanson DW, Salari N, Yeung A. Difficulties, Challenges, and the Learning Curve of Avoiding Complications in Lumbar Endoscopic Spine Surgery. Int J Spine Surg. 2021, 15 (suppl 3), S21–S37.

- Srinivasan, D., Than, K. D., Wang, A. C., La Marca, F., Wang, P. I., Schermerhorn, T. C., & Park, P. Radiation safety and spine surgery: systematic review of exposure limits and methods to minimize radiation exposure. World Neurosurg 2014, 82, 1337–1343. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt BT, Chen KT, Kim J, Brooks NP. Applications of navigation in full-endoscopic spine surgery. Eur Spine J. 2023.

- Hagan MJ, Remacle T, Leary OP, Feler J, Shaaya E, Ali R, Zheng B, Bajaj A, Traupe E, Kraus M, Zhou Y, Fridley JS, Lewandrowski KU, Telfeian AE. Navigation Techniques in Endoscopic Spine Surgery. Biomed Res Int. 2022, 2022, 8419739.

- Kambin P, Sampson S. Posterolateral percutaneous suction-excision of herniated lumbar intervertebral discs. Report of interim results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986, 207, 37–43.

- Hijikata, S. Percutaneous nucleotomy. A new concept technique and 12 years experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989, 238, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambin P, Brager MD. Percutaneous posterolateral discectomy. Anatomy and mechanism. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987, 223, 145–154.

- Mayer HM, Brock M. Percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy (PELD). Neurosurg Rev. 1993, 162, 115–120.

- Ditsworth, DA. Endoscopic transforaminal lumbar discectomy and reconfiguration: a postero-lateral approach into the spinal canal. Surg Neurol. 1998, 496, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kambin P, O'Brien E, Zhou L, Schaffer JL. Arthroscopic microdiscectomy and selective fragmentectomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998, 347, 150–167.

- Yeung AT, Tsou PM. Posterolateral endoscopic excision for lumbar disc herniation: Surgical technique, outcome, and complications in 307 consecutive cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002, 277, 722–731.

- Choi G, Lee SH, Raiturker PP, Lee S, Chae YS. Percutaneous endoscopic interlaminar discectomy for intracanalicular disc herniations at L5-S1 using a rigid working channel endoscope. Neurosurgery 2006, 1 Suppl), ONS59–ONS68.

- Ahn, Y. A Historical Review of Endoscopic Spinal Discectomy. World Neurosurg. 2021, 145, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Antoni DJ, Claro ML, Poehling GG, Hughes SS. Translaminar lumbar epidural endoscopy: anatomy, technique, and indications. Arthroscopy. 1996, 12, 330–334. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang W, Liu Z, Wu S, Zhang S, Bai H, Wang J. [Research of learning curves for unilateral biportal endoscopy technique and associated postoperative adverse events]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi 2022, 3610, 1221–1228.

- Xu J, Wang D, Liu J, Zhu C, Bao J, Gao W, Zhang W, Pan H. Learning Curve and Complications of Unilateral Biportal Endoscopy: Cumulative Sum and Risk-Adjusted Cumulative Sum Analysis. Neurospine 2022, 193, 792–804.

- Zhang J, Gao Y, Zhao B, Li H, Hou X, Yin L. Comparison of percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic discectomy and open lumbar discectomy for lumbar disc herniations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Surg. 2022, 9, 984868. [CrossRef]

- Xu X, Chen C, Tang Y, Wang F, Wang Y. Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Percutaneous Spinal Endoscopy versus Traditional Open Surgery for Lumbar Disc Herniation: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Healthc Eng. 2022, 2022, 6033989.

- Zhao XM, Chen AF, Lou XX, Zhang YG. Comparison of Three Common Intervertebral Disc Discectomies in the Treatment of Lumbar Disc Herniation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Based on Multiple Data. J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 6604. [CrossRef]

- He D, Cheng X, Zheng S, Deng J, Cao J, Wu T, Xu Y. Unilateral Biportal Endoscopic Discectomy versus Percutaneous Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy for Lumbar Disc Herniation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 2023, 173, e509–e520. [CrossRef]

- Choi KC, Shim HK, Hwang JS, Shin SH, Lee DC, Jung HH, Park HA, Park CK. Comparison of Surgical Invasiveness Between Microdiscectomy and 3 Different Endoscopic Discectomy Techniques for Lumbar Disc Herniation. World Neurosurg. 2018, 116, e750–e758. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merter A, Karaeminogullari O, Shibayama M. Comparison of Radiation Exposure Among 3 Different Endoscopic Diskectomy Techniques for Lumbar Disk Herniation. World Neurosurg. 2020, 139, e572–e579. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastrangelo G, Fedeli U, Fadda E, Giovanazzi A,Scoizzato L, Saia B. Increased cancer risk among surgeons in an orthopaedic hospital. Occup Med 2005, 55, 498–500. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan-Bin Liu,Yin Wang,Zi-Qiang Chen,Jun Li,Wei Chen,Chuan-Feng Wang,Qiang Fu. Volume Navigation with Fusion of Real-Time Ultrasound and CT Images to Guide Posterolateral Transforaminal Puncture in Percutaneous Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy. Pain Physician. 2018, 21, E265–E278.

- Jin M, Lei L, Li F, Zheng B. Does Robot Navigation and Intraoperative Computed Tomography Guidance Help with Percutaneous Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy? A Match-Paired Study. World Neurosurg. 2021, 147, e459–e467. [CrossRef]

- Huang X, Liu X, Zhu B, Hou X, Hai B, Li S, Yu D, Zheng W, Li R, Pan J, Yao Y, Dai Z, Zeng H. Evaluation of Augmented Reality Surgical Navigation in Percutaneous Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy: Clinical Study. Bioengineering 2023, 1011, 1297.

- Wu B, Wei T, Yao Z, Yang S, Yao Y, Fu C, Xu F, Xiong C. A real-time 3D electromagnetic navigation system for percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic discectomy in patients with lumbar disc herniation: a retrospective study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022, 231, 57.

- Lin Y, Rao S, Chen B, Zhao B, Wen T, Zhou L, Su G, Du Y, Li Y. Electromagnetic navigation-assisted percutaneous endoscopic foraminoplasty and discectomy for lumbar disc herniation: technical note and preliminary results. Ann Palliat Med. 2020, 9, 3923–3931. [CrossRef]

- Ao S, Wu J, Tang Y, Zhang C, Li J, Zheng W, Zhou Y. Percutaneous Endoscopic Lumbar Discectomy Assisted by O-Arm-Based Navigation Improves the Learning Curve. Biomed Res Int. 2019 Jan 10;2019:6509409. Tanaka M, Zygogiannnis K, Sake N, Arataki S, Fujiwara Y, Taoka T, de Moraes Modesto TH, Chatzikomninos I. A C-Arm-Free Minimally Invasive Technique for Spinal Surgery: Cervical and Thoracic Spine. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023 Oct 6;59(10):1779.

- Tanaka M, Arataki S, Mehta R, Tsai TT, Fujiwara Y, Uotani K, Yamauchi T. Transtubular Endoscopic Posterolateral Decompression for L5-S1 Lumbar Lateral Disc Herniation. J Vis Exp. 2022, 188.

- Tanaka M, Sonawane S, Uotani K, Fujiwara Y, Sessumpun K, Yamauchi T, Sugihara S. Percutaneous C-Arm Free O-Arm Navigated Biopsy for Spinal Pathologies: A Technical Note. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 636.

- Tanaka M, Sonawane S, Meena U, Lu Z, Fujiwara Y, Taoka T, Uotani K, Oda Y, Sakaguchi T, Arataki S. Comparison of C-Arm-Free Oblique Lumbar Interbody Fusion L5-S1 (OLIF51) with Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion L5-S1 (TLIF51) for Adult Spinal Deformity. Medicina 2023, 59, 838. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Preoperative radiograms, A: Antero-posterior lumbar radiogram, B: Lateral lumbar neutral radiogram, C: Lateral lumbar flexion radiogram, D: Lateral lumbar extension radiogram. L4/5 disc space narrowing and slight instability was obsered. (red arrows).

Figure 1.

Preoperative radiograms, A: Antero-posterior lumbar radiogram, B: Lateral lumbar neutral radiogram, C: Lateral lumbar flexion radiogram, D: Lateral lumbar extension radiogram. L4/5 disc space narrowing and slight instability was obsered. (red arrows).

Figure 2.

Preoperative CT and MR imaging, A: Mid sagittal 3D reconstruction CT, B: 3D CT, .C: T2 weighted mid-sagittal MR imaging, D: T2 weighted axial MR imaging at L3/4, E: T2 weighted axial MR imaging at L4/5, A large lumbar disc herniation was observed (red arrows).

Figure 2.

Preoperative CT and MR imaging, A: Mid sagittal 3D reconstruction CT, B: 3D CT, .C: T2 weighted mid-sagittal MR imaging, D: T2 weighted axial MR imaging at L3/4, E: T2 weighted axial MR imaging at L4/5, A large lumbar disc herniation was observed (red arrows).

Figure 3.

Patient positioning, neuromonitouring, and navigation, A: Prone position, B: Neuromonitouring, C: A navigation reference frame (black arrow) amd a navigated pointer (red arrow).

Figure 3.

Patient positioning, neuromonitouring, and navigation, A: Prone position, B: Neuromonitouring, C: A navigation reference frame (black arrow) amd a navigated pointer (red arrow).

Figure 4.

Skin incision, A: Intraoperative image, B: Navigation monitor.

Figure 4.

Skin incision, A: Intraoperative image, B: Navigation monitor.

Figure 5.

Bony resection, A: Intraoperative image, B: Endoscopy image, C: Navigation monitor.

Figure 5.

Bony resection, A: Intraoperative image, B: Endoscopy image, C: Navigation monitor.

Figure 7.

Skin closure, A: Postoperative ragiogram, B: Removed disc material.

Figure 7.

Skin closure, A: Postoperative ragiogram, B: Removed disc material.

Figure 8.

Postoperative images, A : Postoperative lumbar antero-posterior ragiogram, B : postopertive lumbar lateral ragiogram, C: Mid sagittal T2-weighted MR imaging, D : Axial T2-weighted MR imaging at L4/5. The herniated disc is adequately resected (red arrow).

Figure 8.

Postoperative images, A : Postoperative lumbar antero-posterior ragiogram, B : postopertive lumbar lateral ragiogram, C: Mid sagittal T2-weighted MR imaging, D : Axial T2-weighted MR imaging at L4/5. The herniated disc is adequately resected (red arrow).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).