I. Introduction

The information stored within a cell is composed of genetic information and epigenetic information. Genetic information is in the form of sequential DNA sequences, while epigenetic information is contextual information that modulates the expression of genes.

Genetic information is the blueprint for the cell’s structure and function, and is responsible for the inheritance of traits from one generation to the next. This information is encoded in the DNA sequence, which is made up of four nucleotides (adenine, thymine, guanine, and cytosine) arranged in a specific order. The sequence of these nucleotides determines the sequence of amino acids in proteins, which in turn determine the structure and function of the cell.[

1,

2]

Epigenetic information, on the other hand, refers to modifications that occur to the DNA or the proteins of that package DNA (histones). It does not change the underlying DNA sequence, but can influence gene expression. These modifications can be heritable and can be passed down from cell to cell during cell division, and from one generation to the next. Epigenetic modifications can be influenced by environmental factors such as diet, stress, and exposure to toxins.[

3,

4,

5]

It is reasonable to think of epigenetic information as a contextual layer that is added onto the sequential layer of genetic information, and which continuously changes over time to modulate cellular function. Epigenetic modifications can affect how genes are expressed and can be influenced by a variety of factors, such as environmental cues and developmental signals, leading to a complex interplay between genetic and epigenetic information.

Epigenetic memory refers to the ability of cells to maintain past epigenetic information over time, even after cell division or changes in environmental conditions. This memory is thought to be important for past cellular experiences and can be passed down through generations of cells. [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]

When epigenetic modifications accumulate in cells, they combine with genetic information in the nucleus to regulate complex cellular activities. Epigenetic modifications, such as changes in DNA methylation or histone modification, can alter the accessibility of DNA and influence gene expression patterns, ultimately affecting cellular behavior.

The current state of epigenetic modifications can be thought of as an additional information layer stored on top of genetic information in the form of context-specific information. This information layer affects gene expression and regulates various cellular activities. While current epigenetic information can be stored and inherited, it is not known if past epigenetic information is remained in a cell and how it can be retrieved in the form of memory in a cell.

Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms involved in the storage and recall of epigenetic memory with past epigenetic information. [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]

The term of Epigenetic Archive is distinct from the epigenetic memory. While epigenetic memory refers to the biological material that remains in nucleus of the cell, Epigenetic Archive refers to the biological information encoded somewhere in the past. Epigenetic Archive specifically denotes a data repository where information about all past epigenetic modifications, even those that may have changed or disappeared by now, is recorded. [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]

This concept bears similarities to the characteristics of blockchain, emphasizing data immutability and a distributed ledger to maintain a continuous record of epigenetic modifications over time. By combining another term of ‘cellular blockchain’, this study seeks to illustrate the biological mechanism of how ‘Epigenetic Archive’ is formed and preserved in a cell population.

II. Cellular Blockchain Concept

Blockchain is a decentralized database technology used to securely record and manage data across a peer-to-peer network of computers. It ensures transparency, security, and immutability of recorded information. [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]

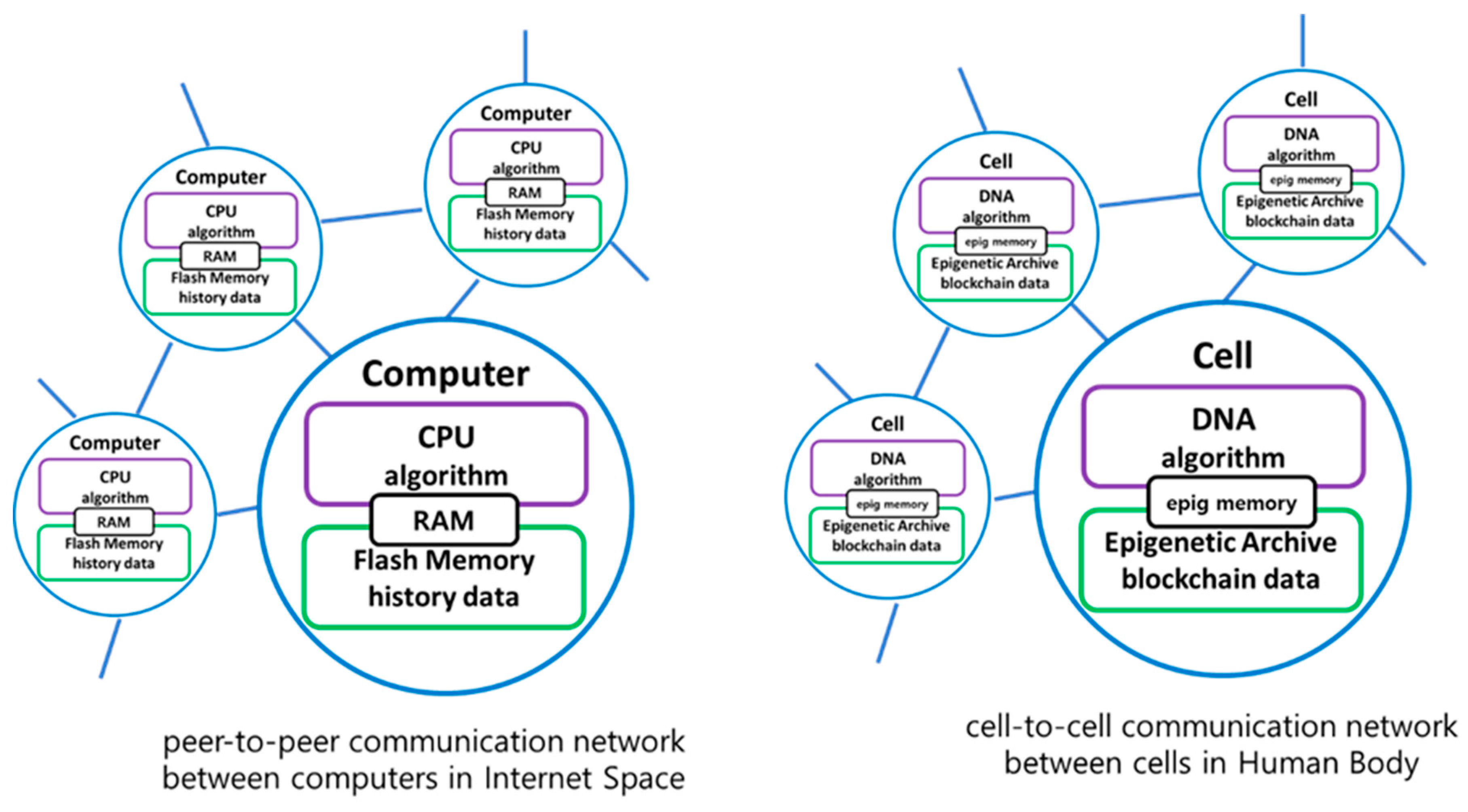

A cellular blockchain concept is inspired from the analogy between digital computers and biological living cells.

Figure 1 shows its analogy of the peer-to-peer network between computers in the internet space and the cell-to-cell network between cells in human body. It is assumed that the algorithm in CPU of the digital computer corresponds to the genetic algorithm in DNA of the cell, and history data in memory of the computer to epigenetic data in cellular blockchain of the cell.

The current epigenetic modifications on DNA can be likened to the role of RAM(Random Access Memory) in a computer, as both serve to store immediately needed information for the cell or process. Being volatile, both can undergo rapid changes. On the other hand, the Epigenetic Archive, responsible for storing past epigenetic data, can be compared to Flash Memory in a computer. Both act as non-volatile storage, capable of preserving data for extended periods. Therefore, in internet space, data created through a peer-to-peer network is distributed and stored in a blockchain manner. Similarly, in the human body, epigenetic data created through a cell-to-cell network between cells is distributed and stored in Epigenetic Archive using a blockchain manner.

Epigenetic Archive is a blockchain-like database of the cell that connects epigenetic information from the origin of cells to the present by making it a long chain of data blocks. The current epigenetic information is implemented through the accumulated epigenetic modification and is attached to the nuclear DNA with genetic information in the form of methylation. This is implemented as a biochemical material, affects cellular activity, and can be passed on to the next generation. At the same time, during modification, data is stored in the Epigenetic Archive as a blockchain, that is, as a Current Block, using biological data logic. Afterwards, when modification is updated, a new data block is created, and the old data block becomes the Previous Block. As blocks are added in this way, a long cellular blockchain is created. This blockchain becomes an Epigenetic Archive. Here, only the data in the Current Block remains in the DNA in the form of modification and affects cellular activities such as gene expression.

However, Epigenetic Archive must include all data related to modification of other cells in the cell population. In other words, the blockchain collects all modifications, including those of surrounding cells, that occurred within the same time period, creates one block, and shares it with a common ledge. Therefore, all cells have the same blockchain, but they attach their own to DNA, causing an epigenetic effect.

III. Epigenetic Archive Inheritance

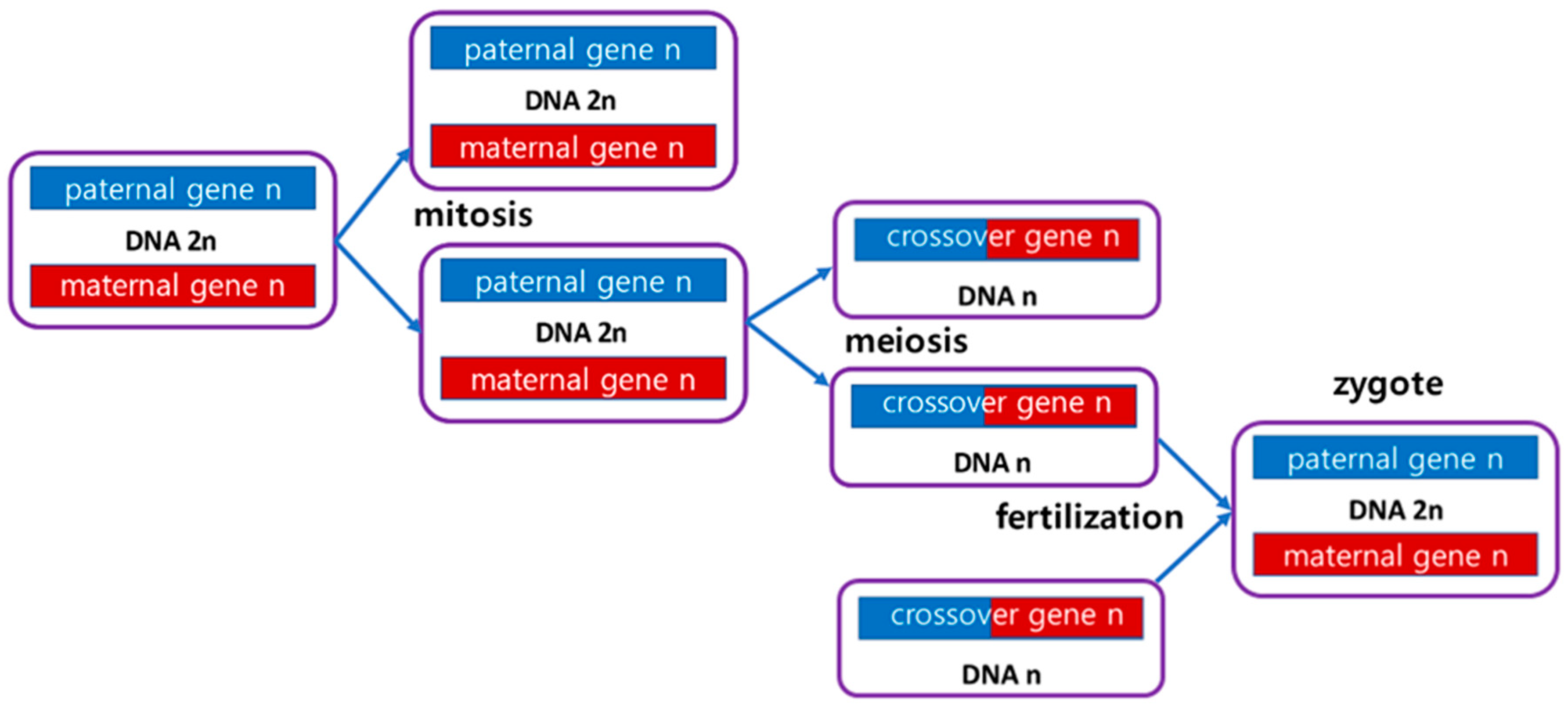

Human life begins with a fertilized egg, zygote and ends with death. As shown in

Figure 2, the zygote undergoes division, differentiation, and growth through mitosis, and finally becomes an adult composed of 40 trillion cells. Here, the sperm and egg produced through meiosis of the germ cells combine to form a new fertilized egg, and life continues.

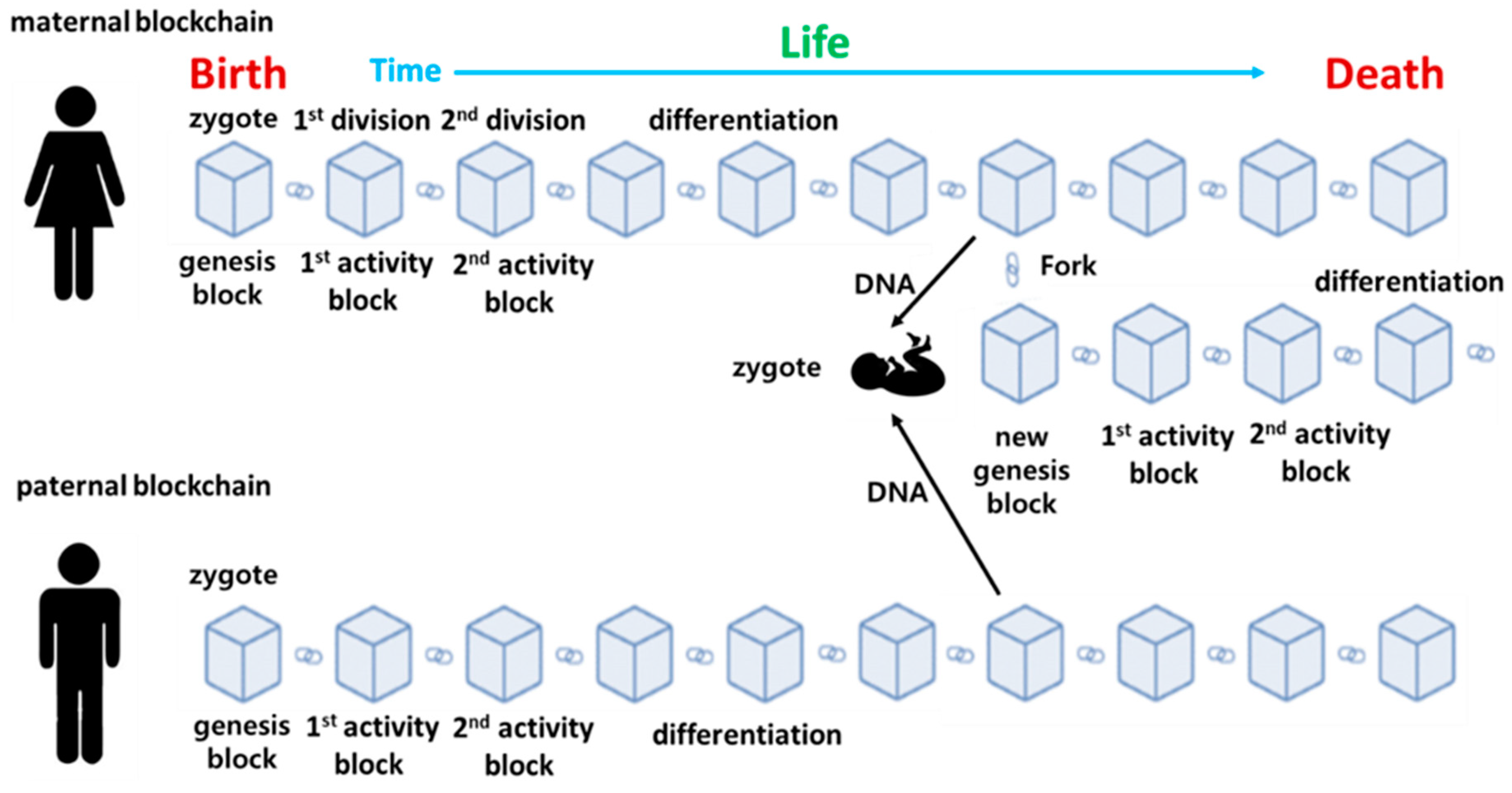

In

Figure 3, assume that human life from birth to death is recorded as a cellular blockchain in Epigenetic Archive. The starting point is the genesis block, which records the cellular activity of a single cell fertilized egg. It divides into two identical cells through the first mitosis. The description of this process is linked to the genesis block as the 1st activity block. As cell activity continues through further cell division and differentiation, corresponding data blocks are sequentially created and connected, and the blockchain ends at the moment when life activity ends.

In other words, the connected blockchain records the life activities is stored equally in all cells. Here, through reproduction, this process can be passed on to the offspring. At this time, the new fertilized egg receives half and half of the DNA from the mother and father, and starts life activities again from the new fertilized egg. From this point on, the child cell division, differentiation, and growth process repeats the process of the parent cell. In other words, the genesis block for the fertilized egg of the parent cell starts through a fork in the parent cell blockchain, and it is connected to the parent cell before the fork and continues to extend the blockchain. Therefore, if you trace it back, the blockchain of the child cell is connected to the genesis block of the parent cell, which is again connected to the blockchain of the grand parent cell, which is ultimately connected to the genesis block of the first human ancestor.

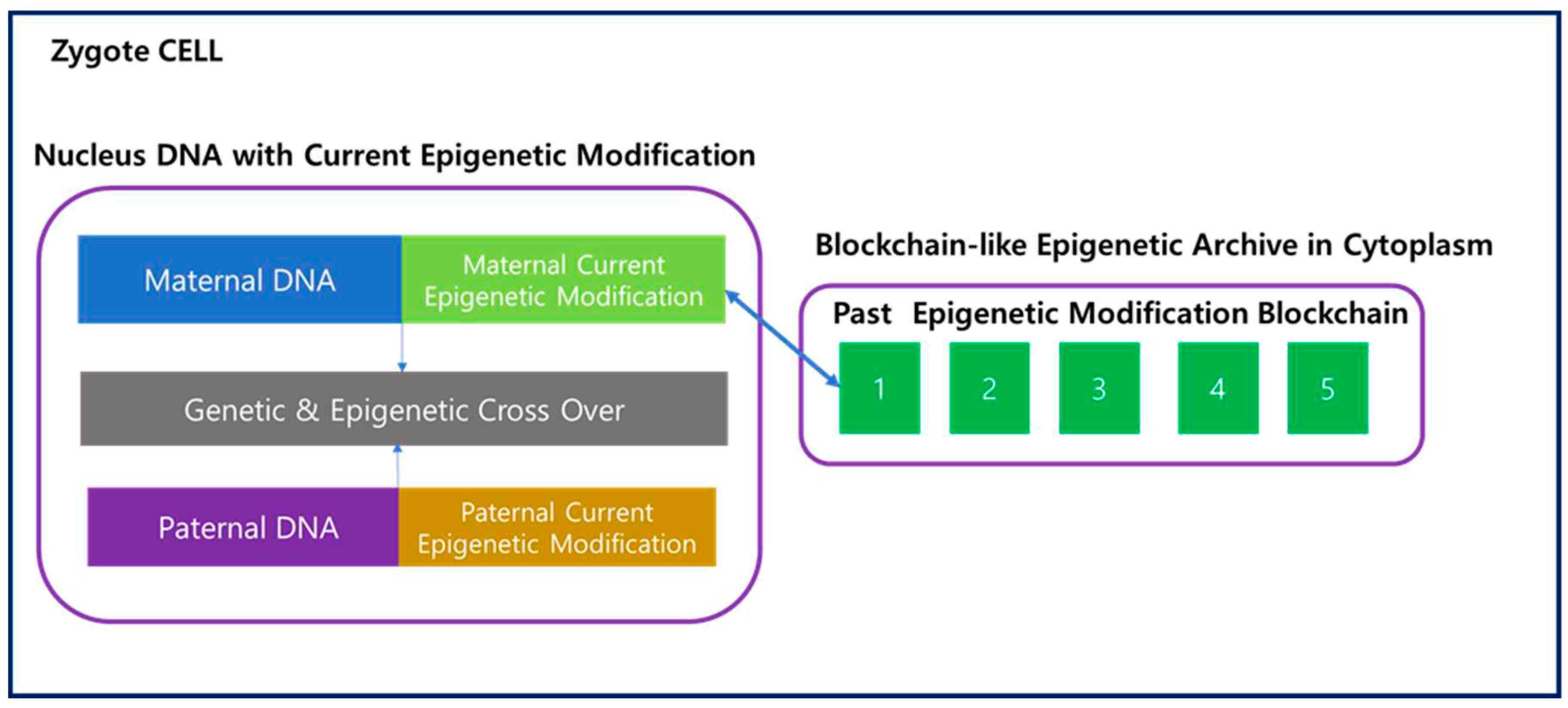

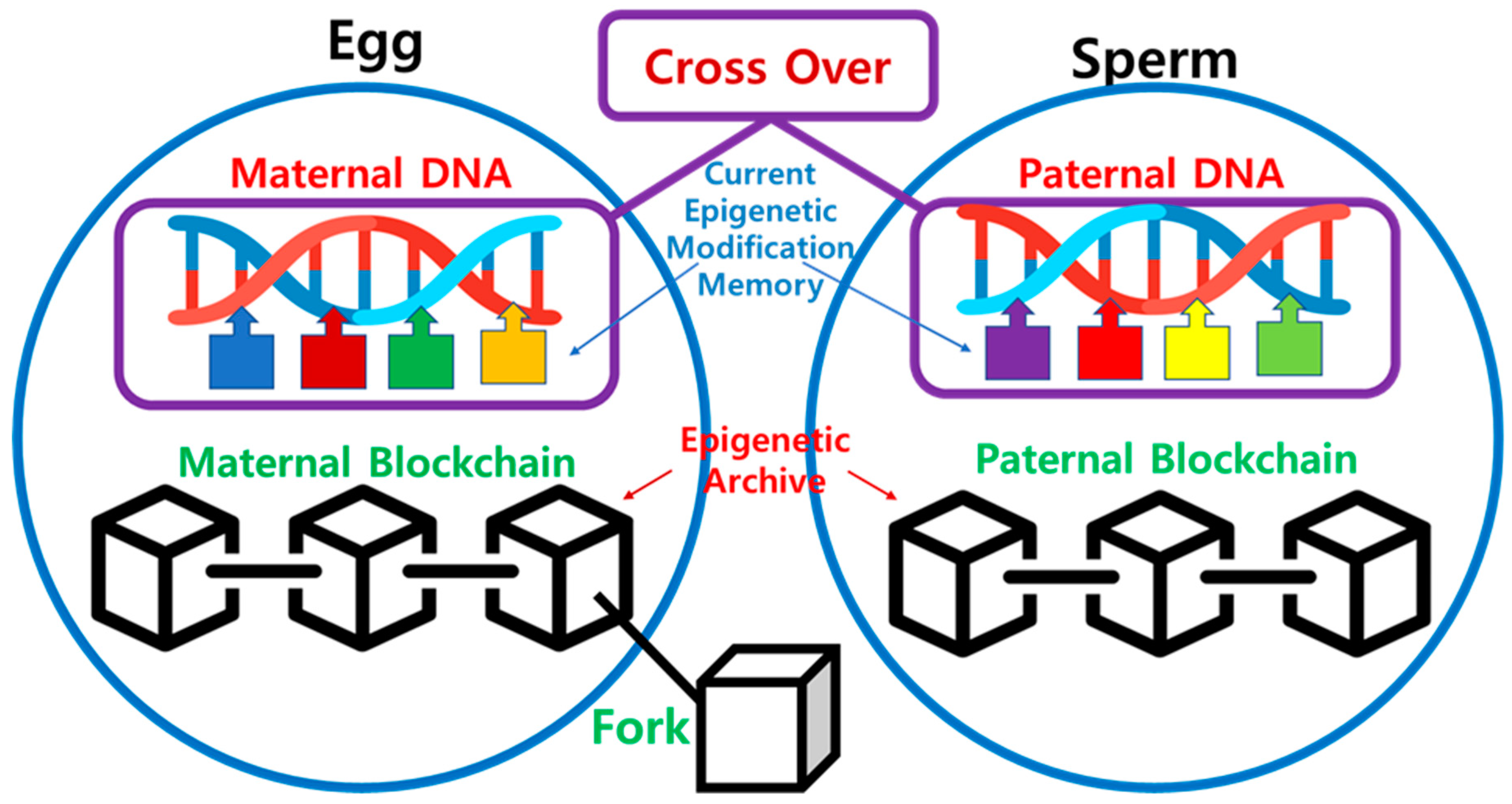

As shown in

Figure 4, when the egg and sperm merge to form a zygote, not only nucleus genetic DNA but active epigenetic modifications undergo crossover, with data from both the maternal and paternal lineages. On the other hand, information about past epigenetic modifications is stored in the Epigenetic Archive within the cytoplasm in a blockchain-like fashion. The merging of these two blockchains in the zygote is practically challenging, and it is reasonable to consider a Fork scenario, where one of the blockchains diverges to start a new one. Consequently, the transmission of information to the next generation through Fork occurs via the maternal lineage, while the paternal lineage loses its blockchain. Therefore, in the zygote, the maternal epigenetic blockchain is replicated, and new blocks are added, extending the chain. This process takes place in the maternal uterus, and the existing maternal blockchain continues to be connected even after the Fork.

IV. Results

As the results, two illustrative demonstrations are presented for a new term of “Epigenetic Archive” with cellular blockchain concept.

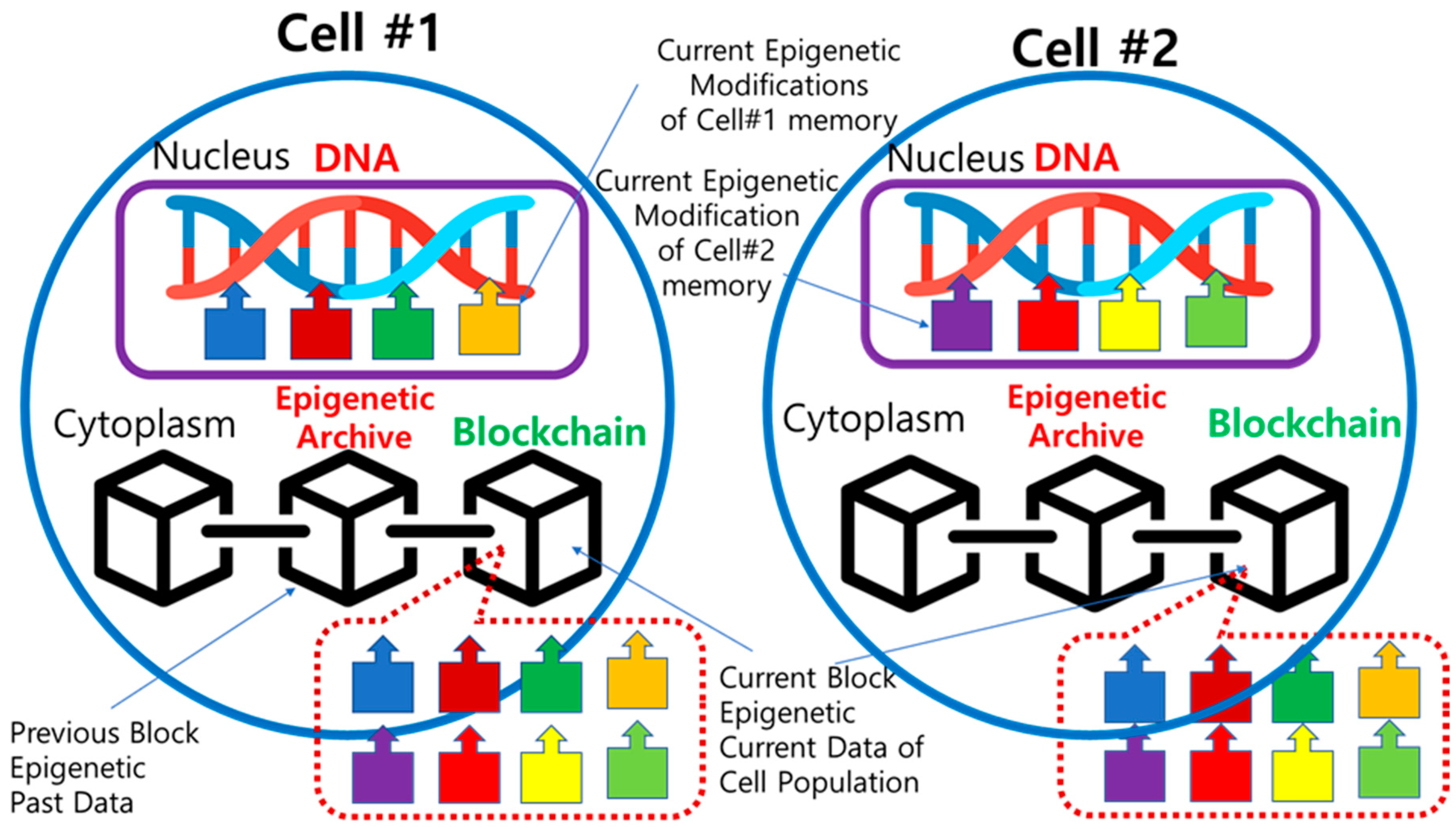

First in

Figure 5, there is a cell population consisting of Cell#1 and Cell#2. In each cell, four different epigenetic modifications occurred in nucleus during the current time period. They are attached to DNA in the form of biological memory and affect cell activity and heredity. At the same time, all modifications are copied as epigenetic information into Epigenetic Archive in cytoplasm. Throughout the whole population, the eight epigenetic modifications data are collected in the common ledger and stored as the Current Block of the blockchain in Epigenetic Archive of each cell. When a new block is created, the Current Block moves to the Previous Blocks and continue to extend the blockchain. Therefore, both cells #1 and #2 have a common blockchain, while each cell has its own current epigenetic modifications attached to DNA.

Second in

Figure 6, during the formation of the zygote, the merging of active epigenetic modifications occurs alongside the crossover of nucleus DNA, blending maternal and paternal. On the other hand, information about past epigenetic modifications is stored in the Epigenetic Archive within the cytoplasm in a blockchain-like manner. It involves a Fork scenario with the maternal lineage serving as the continuous epigenetic chain. The maternal epigenetic blockchain is preserved and expanded, while the paternal lineage loses its blockchain. This scenario, mirrors the mitochondrial inheritance pattern.

V. Conclusion

This study offers a novel perspective on the question of "life," defining it as the harmonious interplay between immutable genetic algorithms and continuously updating epigenetic historical records within the activities of cells. Unlike the static genetic algorithms, the intriguing focus here is on the less understood Epigenetic Archive. Drawing inspiration from the similarity between the data characteristics of Epigenetic Archive and the blockchain concept, the study endeavors to elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

The conclusion drawn from this study is that a new introduced term of “Epigenetic Archive” serves as a record of epigenetic modifications, spanning from the initial cell, preserving data securely up to the present moment, encompassing not only individual cells but the entire cell population. The data characteristics of Epigenetic Archive, akin to a vast, spatiotemporally updated database, bear a striking resemblance to the principles of blockchain technology, an insight crucially derived from the study.

Furthermore, the study postulates an argument that Epigenetic Archive unlike genetic algorithms, is conveniently preserved within the cell’s cytoplasm, potentially influencing the heredity process. By presenting this innovative conceptual model, the research opens the door to further groundbreaking studies, suggesting a promising avenue for future research in biology and genetics.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Lander, Eric S., et al. "Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome." Nature 409.6822 (2001): 860-921. [CrossRef]

- Venter, J. Craig, et al. "The sequence of the human genome." Science 291.5507 (2001): 1304-1351. [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, Andrew P., and Randy L. Jirtle. "Epigenetics: a means to explore the interface between genetics and the environment." Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 983.1 (2003): 154-165.

- Cedar, Howard, and Yehudit Bergman. "Linking DNA methylation and histone modification: patterns and paradigms." Nature Reviews Genetics 10.5 (2009): 295-304. [CrossRef]

- Kundaje, Anshul, et al. "Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes." Nature 518.7539 (2015): 317-330. [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, Andrew P., and Randy L. Jirtle. "Epigenetics: a means to explore the interface between genetics and the environment." Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 983.1 (2003): 154-165.

- Holliday, Robin. "Epigenetics: an overview." Developmental genetics 31.2 (2002): 173-177.

- Agustina D’Urso, Jason H. Bricknerrends, Mechanisms of epigenetic memory, trends in Genetics, Volume 30, Issue 6, June 14, Pages 230-236. [CrossRef]

- Allis, C. David, and Thomas Jenuwein. "The molecular hallmarks of epigenetic control." Nature Reviews Genetics 17.8 (2016): 487-500. [CrossRef]

- Zentner, Gabriel E., and Steven Henikoff. "Regulation of nucleosome dynamics by histone modifications." Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 20.3 (2013): 259-266. [CrossRef]

- Weinhold, Bob. "Epigenetics: the science of change." Environmental health perspectives 114.3 (2006): A160-A167. [CrossRef]

- Jablonka, Eva, and Marion J. Lamb. "The inheritance of acquired epigenetic variations." International Journal of Epidemiology 41.1 (2012): 10-13.

- Jiang, Yidong, and Randy Jirtle. "Environmental epigenomics in human health and disease." Environmental and molecular mutagenesis 49.1 (2008): 4-8. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, Aaron D., et al. "Epigenetic memory of transcriptional gene silencing and reprogramming in plants." Nature 447.7143 (2007): 88-91.

- Ma, D., et al. "Epigenetic memory in plants." BBA - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms 1860.1 (2017): 140-147.

- Kimura, Hiroshi. "Histone modifications for human epigenome analysis." Journal of Human Genetics 58.7 (2013): 439-445. [CrossRef]

- Fields, Alexander P., and David J. Waxman. "Establishment of epigenetic memory in the hematopoietic lineage during development." Epigenetics & Chromatin 8.1 (2015): 1-12.

- Goldberg, Aaron D., et al. "Distinct factors control histone variant H3.3 localization at specific genomic regions." Cell 140.5 (2010): 678-691. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, Aaron D., et al. "Epigenetic memory of transcriptional gene silencing and reprogramming in plants." Nature 447.7143 (2007): 88-91.

- Ma, D., et al. "Epigenetic memory in plants." BBA - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms 1860.1 (2017): 140-147.

- Kimura, Hiroshi. "Histone modifications for human epigenome analysis." Journal of Human Genetics 58.7 (2013): 439-445. [CrossRef]

- Fields, Alexander P., and David J. Waxman. "Establishment of epigenetic memory in the hematopoietic lineage during development." Epigenetics & Chromatin 8.1 (2015): 1-12.

- Allis, C. David, and Thomas Jenuwein. "The molecular hallmarks of epigenetic control." Nature Reviews Genetics 17.8 (2016): 487-500. [CrossRef]

- Zentner, Gabriel E., and Steven Henikoff. "Regulation of nucleosome dynamics by histone modifications." Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 20.3 (2013): 259-266. [CrossRef]

- Weinhold, Bob. "Epigenetics: the science of change." Environmental health perspectives 114.3 (2006): A160-A167. [CrossRef]

- Jablonka, Eva, and Marion J. Lamb. "The inheritance of acquired epigenetic variations." International Journal of Epidemiology 41.1 (2012): 10-13. [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, S. (2008). Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System.

- Antonopoulos, A. M. (2014). Mastering Bitcoin: Unlocking Digital Cryptocurrencies.

- Drescher, D. (2017). Blockchain Basics: A Non-Technical Introduction in 25 Steps.

- Antonopoulos, A. M. (2016). The Internet of Money.

- Tapscott, D., & Tapscott, A. (2016). Blockchain Revolution: How the Technology Behind Bitcoin and Other Cryptocurrencies is Changing the World.

- Narayanan, A., et al. (2016). Bitcoin and Cryptocurrency Technologies: A Comprehensive Introduction.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).