Submitted:

17 December 2023

Posted:

18 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

2.1.1. The Experiment Was Conducted at the National Crops Resources Research

2.1.2. Experimental Layout

2.1.3. Data Collection

2.1.4. Identification of Parasitoids

2.1.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Leaf Damage Due to Spodopptera frugiperda in 2020A

3.2. Leaf Damage Due to Spodoptera frugiperda in 2021A

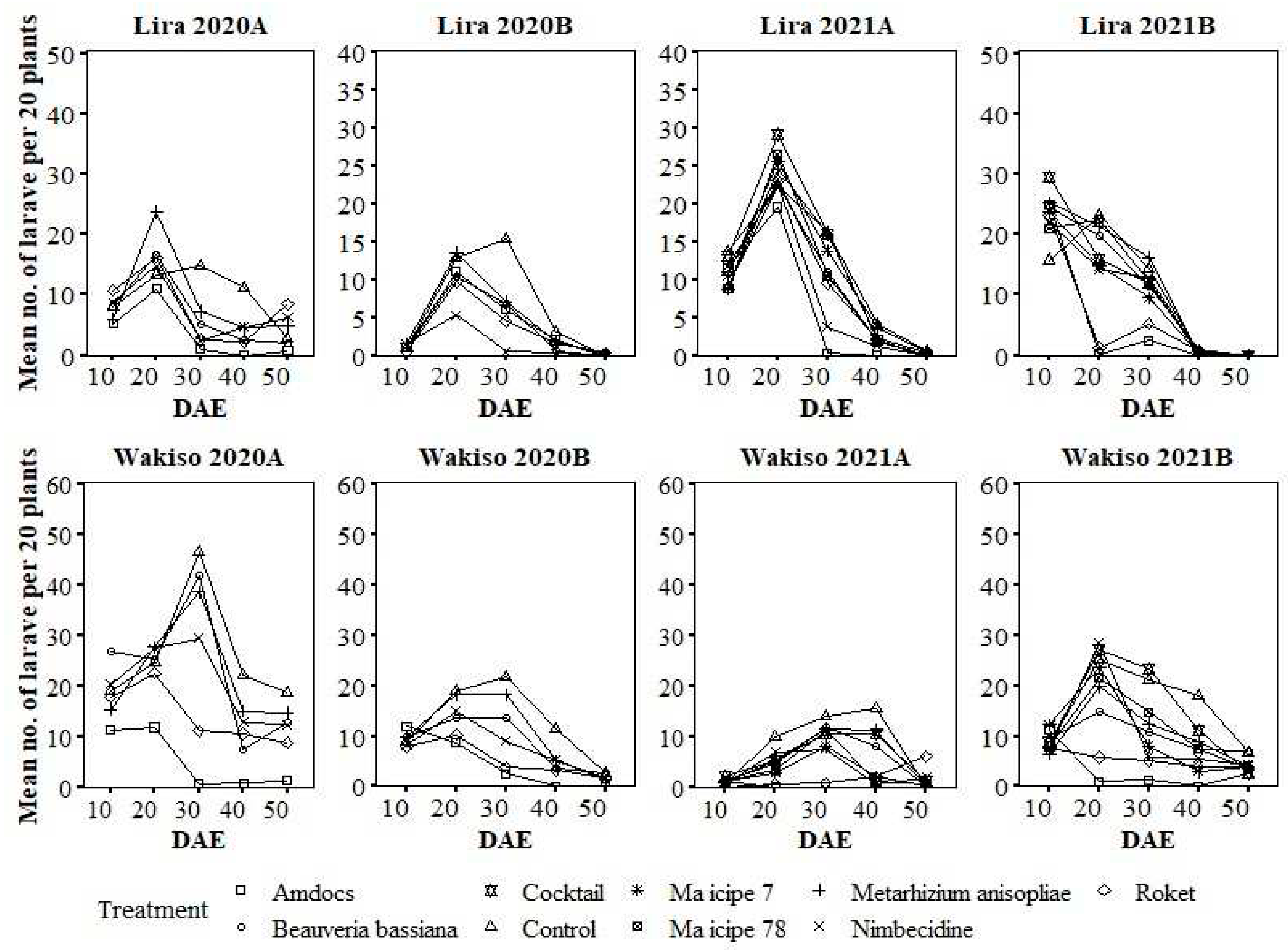

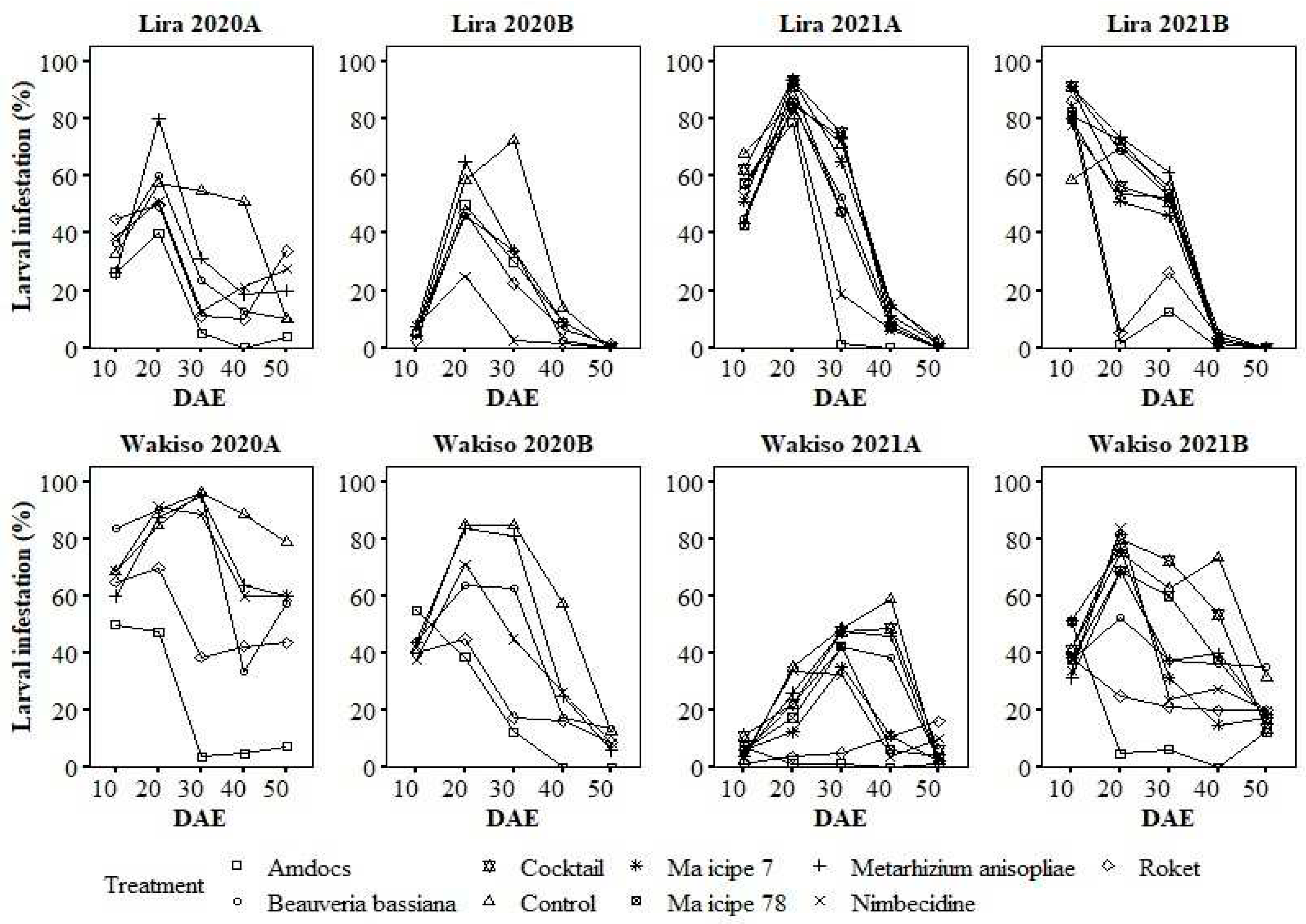

3.3. Larval Abundance and Incidence of Plants Infested with Larvae of Spodoptera frugiperda in 2020

3.4. Larval Abundance and Incidence of Plants Infested with Larvae of Spodoptera frugiperda in 2021

3.5. Abundance of Spodoptera frugiperda Egg Batches and Adults

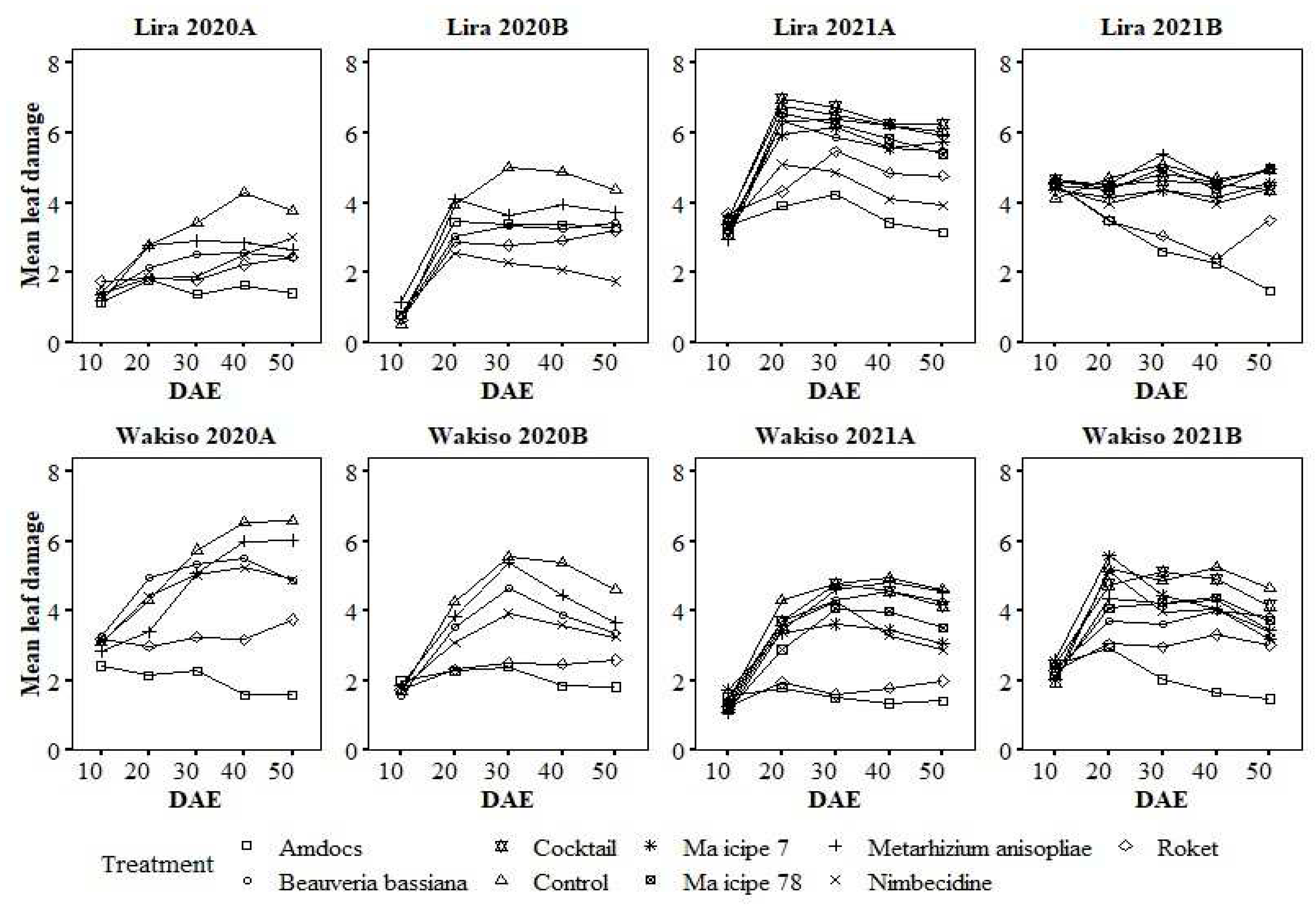

3.6. Variation in Leaf Damage Severity with the Age of Maize Plants under Different Treatments

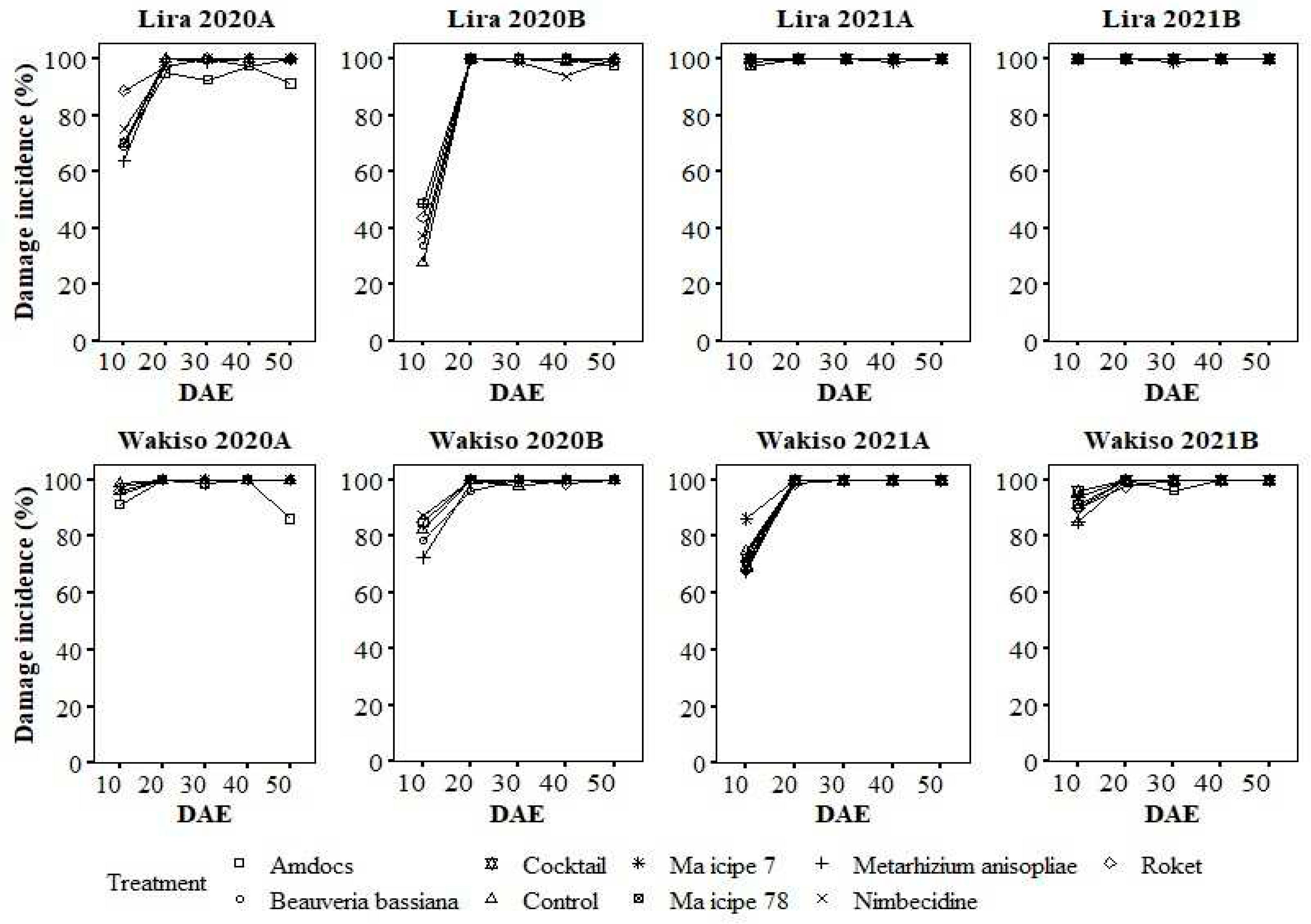

3.7. Variation in the Incidence of Damaged Plants with the Age of Maize Plants under Different Treatments

3.8. Variation in the Abundance of Larvae of Spodoptera frugiperda with the Age of Maize Plants under Different Treatments

3.9. Variation in the Percent of Infested Plants with the Age of Maize Plants under Different Treatments

4. Grain Yield of Maize in Different Locations and Seasons

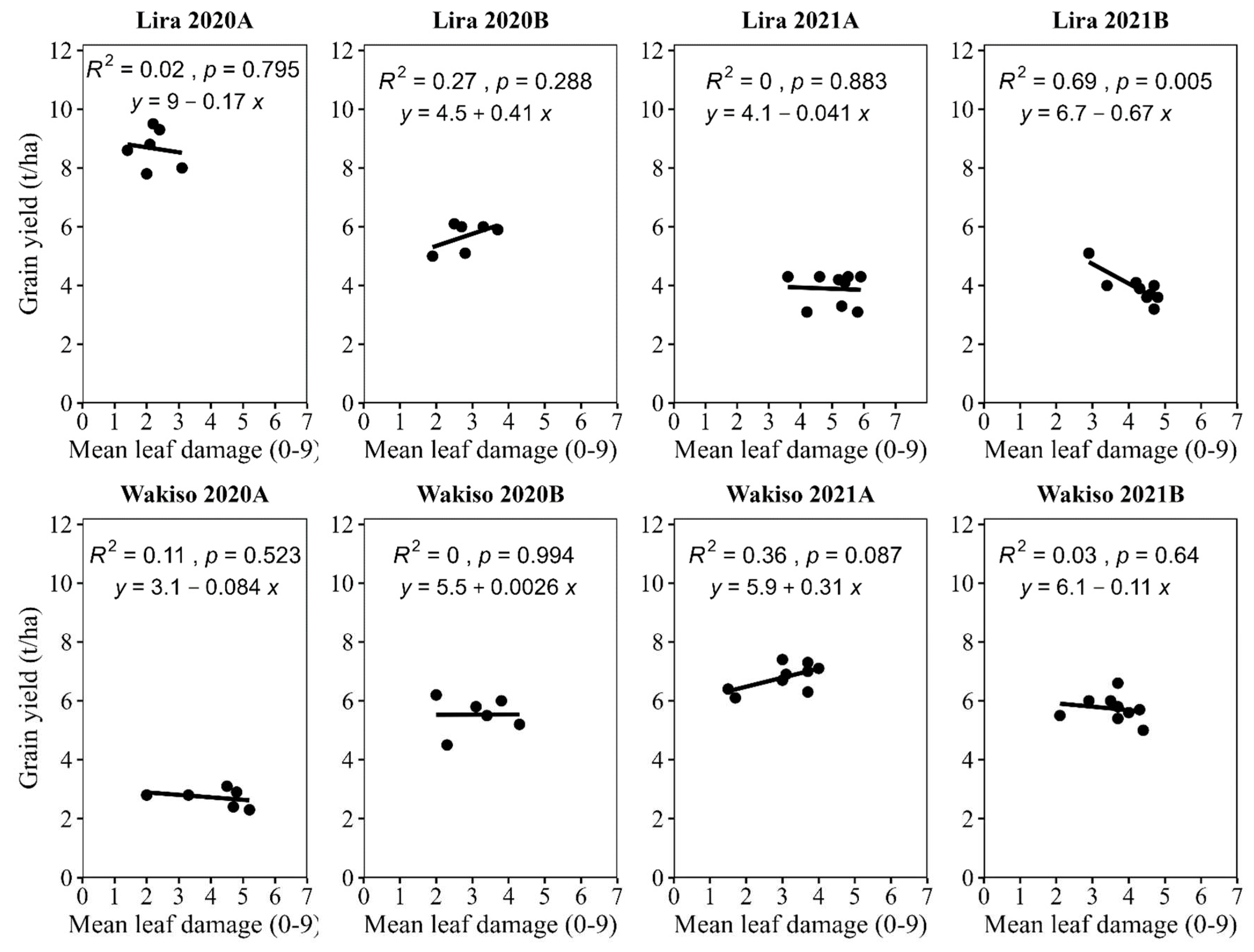

4.1. The Relationship between Grain Yield and Leaf Damage

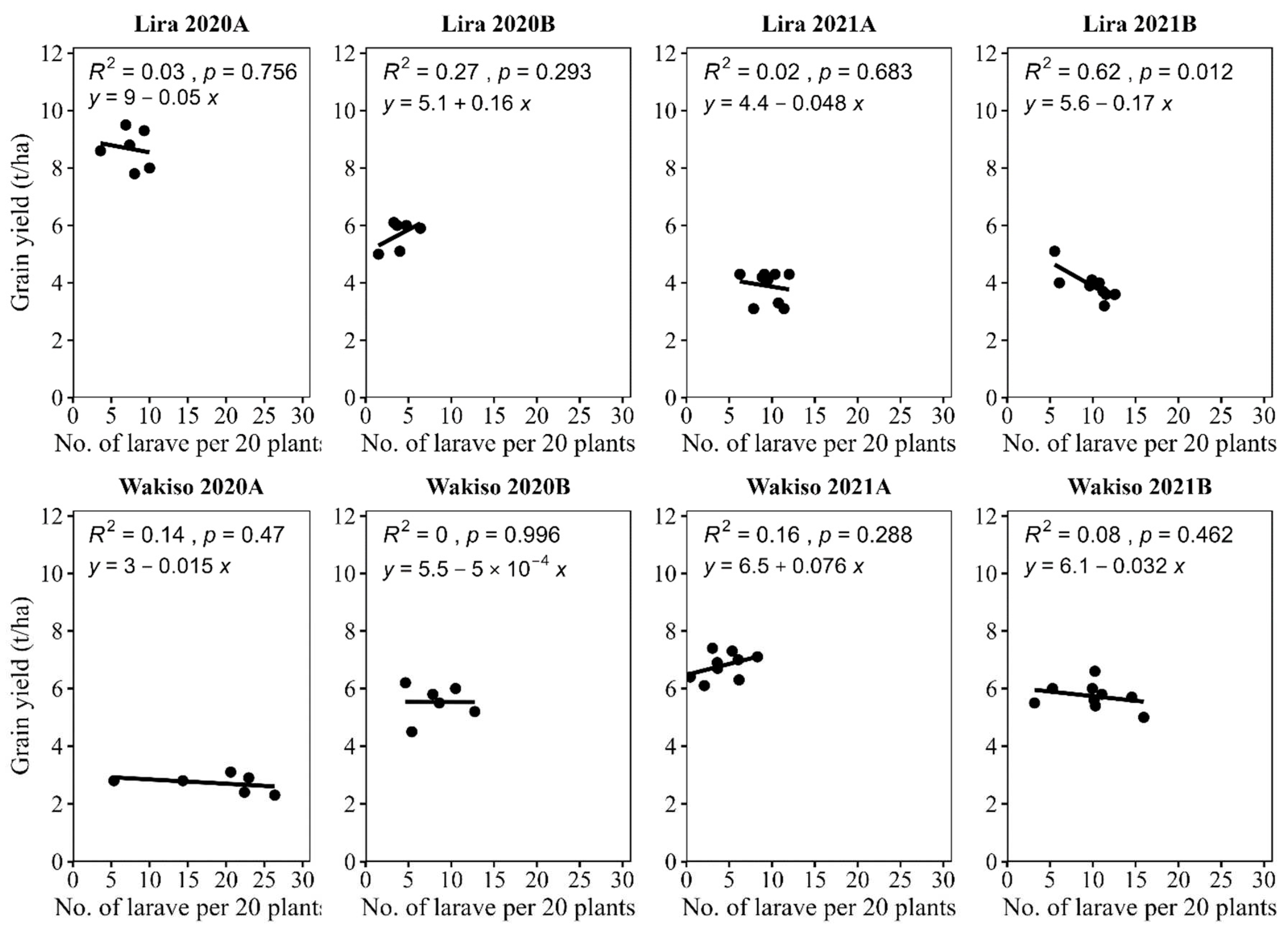

4.2. The Relationship between Grain Yield and Larval Numbers

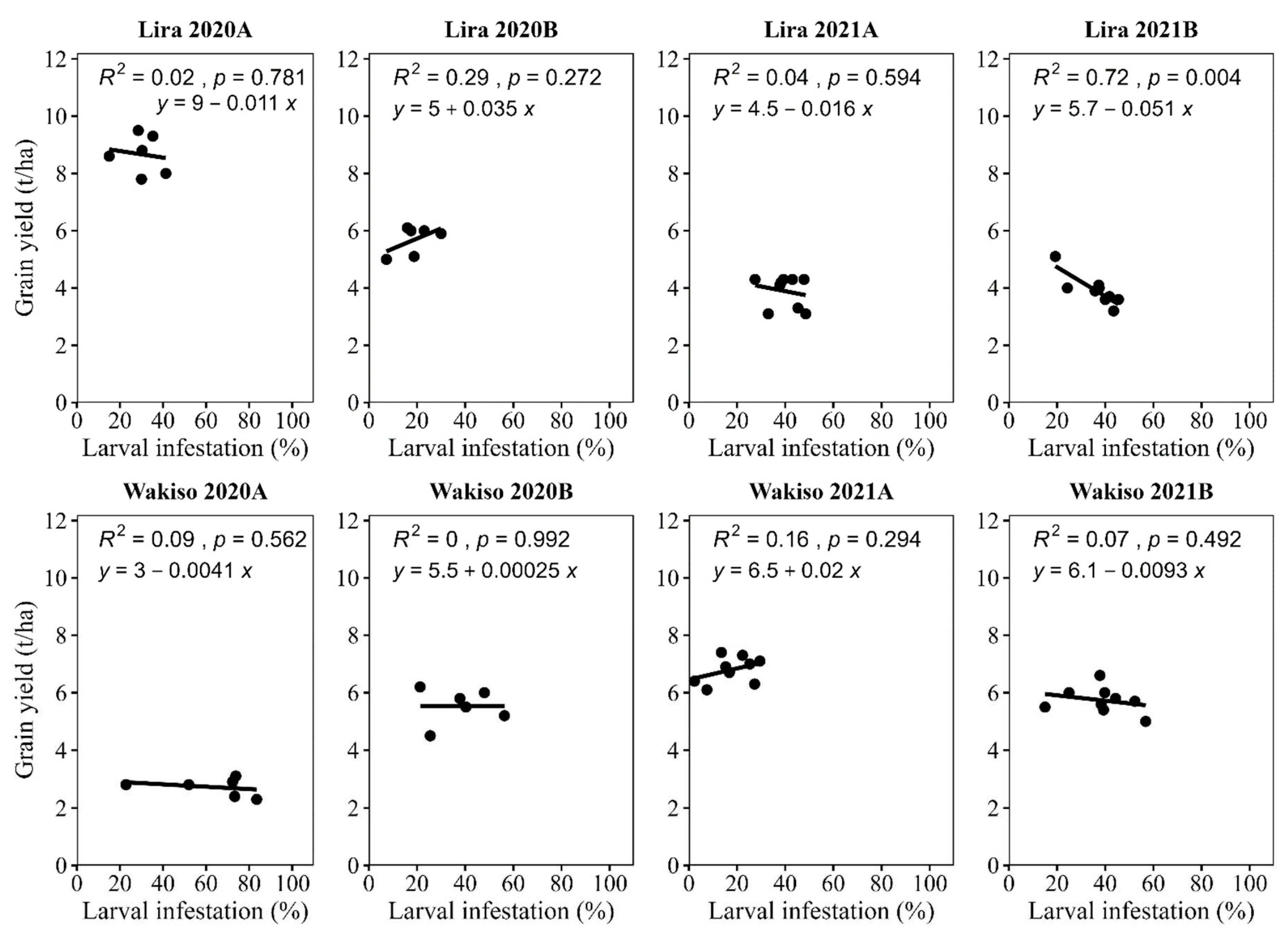

4.3. The Relationship between Grain Yield and Percentage of Infested Plants

4.4. Parasitoids Recovered from Spodoptera frugiperda Eggs and Larvae

4.4.1. Parasitism of Eggs of Spodoptera frugiperda

4.4.2. Parasitism of Larvae of Spodoptera frugiperda

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Erenstein, O.; Jaleta, M.; Sonder, K.; Mottaleb, K.; Prasanna, B.M. Global maize production, consumption and trade: Trends and R&D implications. Food Secur. 2022, 14, 1295–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO FAOSTAT Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat.

- BoU Composition of exports available online: https://www.bou.or.ug/bouwebsite/Statistics/.

- Matama-Kauma, T.; Schulthess, F.; Ogwang, J.A.; Mueke, J.M.; Omwega, C.O. Distribution and relative importance of Lepidopteran cereal stemborers and their parasitoids in Uganda. Phytoparasitica 2007, 35, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekamatte, M. Options for integrated management of termites (Isoptera: Termitidae) in smallholder maize-based cropping systems in Uganda, Makerere University, 2001.

- Goergen, G.; Kumar, P.L.; Sankung, S.B.; Togola, A.; Tamò, M. First report of outbreaks of the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae), a new alien invasive pest in west and central Africa. PLoS One 2016, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahams, A.P.; Bateman, M.; Beale, T.; Clottey, V.; Cock, M.; Colmenarez, Y.; Corniani, N.; Day, R.; Early, R.; Godwin, J.; et al. Fall armyworm: Impacts and implications for Africa. 2017.

- Otim, M.H.; Tay, W.T.; Walsh, T.K.; Kanyesigye, D.; Adumo, S.; Abongosi, J.; Ochen, S.; Sserumaga, J.; Alibu, S.; Abalo, G.; et al. Detection of sister-species in invasive populations of the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) from Uganda. PLoS One 2018, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudron, F.; Zaman-Allah, M.A.; Chaipa, I.; Chari, N.; Chinwada, P. Understanding the factors influencing fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda J.E. Smith) damage in African smallholder maize fields and quantifying its impact on yield. A case study in eastern Zimbabwe; Elsevier Ltd, 2019; Vol. 120;

- Dowd, P.F. Insect management to facilitate preharvest mycotoxin management. J. Toxicol. - Toxin Rev. 2003, 22, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansiime, M.K.; Mugambi, I.; Rwomushana, I.; Nunda, W.; Lamontagne-Godwin, J.; Rware, H.; Phiri, N.A.; Chipabika, G.; Ndlovu, M.; Day, R. Farmer perception of fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda J.E. Smith) and farm-level management practices in Zambia. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2840–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, M.L.; Day, R.K.; Luke, B.; Edgington, S.; Kuhlmann, U.; Cock, M.J.W. Assessment of potential biopesticide options for managing fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) in Africa. J. Appl. Entomol. 2018, 142, 805–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.J. Insecticide resistance in the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 1991, 39, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, R.A.; Omoto, C.; Field, L.M.; Williamson, M.S.; Bass, C. Investigating the molecular mechanisms of organophosphate and pyrethroid resistance in the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutirrez-Moreno, R.; Mota-Sanchez, D.; Blanco, C.A.; Whalon, M.E.; Terán-Santofimio, H.; Rodriguez-Maciel, J.C.; Difonzo, C. Field-evolved resistance of the fall armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) to synthetic insecticides in Puerto Rico and Mexico. J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaventura, D.; Martin, M.; Pozzebon, A.; Mota-Sanchez, D.; Nauen, R. Monitoring of target-site mutations conferring insecticide resistance in Spodoptera frugiperda. Insects 2020, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, B.; Zheng, W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, S.; Li, Z.; Xu, P.; Wilson, K.; Withers, A.; et al. Genetic structure and insecticide resistance characteristics of fall armyworm populations invading China. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2020, 20, 1682–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, F.; Zhang, J.; Shen, H.; Wang, X.; Padovan, A.; Walsh, T.K.; Tay, W.T.; Gordon, K.H.J.; James, W.; Czepak, C.; et al. Whole-genome sequencing to detect mutations associated with resistance to insecticides and Bt proteins in Spodoptera frugiperda. Insect Sci. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnemann, J.A.A.; James, W.J.J.; Walsh, T.K.K.; Guedes, J.V.C.V.C.; Smagghe, G.; Castiglioni, E.; Tay, W.T.T. Mitochondrial DNA COI characterization of Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) from Paraguay and Uruguay. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, J.R.; Carvalho, G.A.; Moura, A.P.; Couto, M.H. .; Maia, J.B. Impact of insecticides used to control Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) in corn on survival, sex ratio, and reproduction of Trichogramma pretiosum riley offspring. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 73, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.; Ullah, F.; Khan, M.A.; Ahmad, S.; Jamil, M.; Sardar, S.; Tariq, K.; Ahmed, N. Efficacy of various natural plant extracts and the synthetic insecticide cypermethrin 25EC against Leucinodes orbonalis and their impact on natural enemies in brinjal crop. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2022, 42, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akutse, K.S.; Kimemia, J.W.; Ekesi, S.; Khamis, F.M.; Ombura, O.L.; Subramanian, S. Ovicidal effects of entomopathogenic fungal isolates on the invasive fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Appl. Entomol. 2019, 143, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngangambe, M.H.; Mwatawala, M.W. Effects of entomopathogenic fungi (EPFs) and cropping systems on parasitoids of fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) on maize in eastern central, Tanzania. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2020, 30, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisay, B.; Tefera, T.; Wakgari, M.; Ayalew, G.; Mendesil, E. The efficacy of selected synthetic insecticides and botanicals against fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda, in Maize. Insects 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Ochoa, J.; Carpenter, J.E.; Heinrichs, E.A.; Foster, J.E. Parasitoids and parasites of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in the Americas and Caribbean basin: An inventory. Florida Entomol. 2003, 86, 254–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abang, A.F.; Nanga, S.N.; Kuate, A.F.; Kouebou, C.; Suh, C.; Masso, C.; Saethre, M.G.; Mokpokpo Fiaboe, K.K. Natural enemies of fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in different agro-ecologies. Insects 2021, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agboyi, L.K.; Goergen, G.; Beseh, P.; Mensah, S.A.; Clottey, V.A.; Glikpo, R.; Buddie, A.; Cafà, G.; Offord, L.; Day, R.; et al. Parasitoid complex of fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda, in Ghana and Benin. Insects 2020, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durocher-Granger, L.; Mfune, T.; Musesha, M.; Lowry, A.; Reynolds, K.; Buddie, A.; Cafà, G.; Offord, L.; Chipabika, G.; Dicke, M.; et al. Factors influencing the occurrence of fall armyworm parasitoids in Zambia. J. Pest Sci. (2004). 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laminou, S.A.; Ba, M.N.; Karimoune, L.; Doumma, A.; Muniappan, R. Parasitism of locally recruited egg parasitoids of the fall armyworm in Africa. Insects 2020, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenis, M.; du Plessis, H.; Van den Berg, J.; Ba, M.N.; Goergen, G.; Kwadjo, K.E.; Baoua, I.; Tefera, T.; Buddie, A.; Cafà, G.; et al. Telenomus remus, a candidate parasitoid for the biological control of Spodoptera frugiperda in Africa, is already present on the continent. Insects 2019, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amadou, L.; Baoua, I.; Malick, N.B.; Karimoune, L.; Muniappan, R. Native parasitoids recruited by the invasive fall armyworm in Niger. Indian J. Entomol. 2018, 80, 1253–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agboyi, L.K.; Nboyine, J.A.; Asamani, E.; Beseh, P.; Badii, B.K.; Kenis, M.; Babendreier, D. Comparative effects of biopesticides on fall armyworm management and larval parasitism rates in northern Ghana. J. Pest Sci. (2004). 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munywoki, J.; Omosa, L.K.; Subramanian, S.; Mfuti, D.K.; Njeru, E.M.; Nchiozem-Ngnitedem, V.-A.; Akutse, K.S. Laboratory and field performance of Metarhizium anisopliae isolate ICIPE 41 for sustainable control of the invasive fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Agronomy 2022, 12, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepkemoi, J.; Fening, K.O.; Ambele, F.C.; Munywoki, J.; Akutse, K.S. Direct and indirect infection effects of four potent fungal isolates on the survival and performance of fall armyworm larval parasitoid Cotesia icipe. Sustain. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis FM, W.W. Visual rating scales for screening whorl- stage corn for resistance to fall armyworm. Mississippi Agricultural & Forestry Experiment Station, Technical Bulletin 186, Mississippi State University, MS39762, USA. 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otim, M.H.; Aropet, S.A.; Opio, M.; Kanyesigye, D.; Opolot, H.N.; Tay, W.T. Parasitoid distribution and parasitism of the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in different maize producing regions of Uganda. Insects 2021, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. Sequence assembly using the Staden package (Babraham Bioinformatics). 2008, 3, 1–31.

- Sayers, E.W.; Beck, J.; Brister, J.R.; Bolton, E.E.; Canese, K.; Comeau, D.C.; Funk, K.; Ketter, A.; Kim, S.; Kimchi, A.; et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D9–D16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratnasingham, S.; Hebert, P.D.N. BOLD: The Barcode of life data system: Barcoding. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2007, 7, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, A.; Young, M.; Quinn, J.; Perez, K.; Sobel, C.; Sones, J.; Levesque-Beaudin, V.; Derbyshire, R.; Fernandez-Triana, J.; Rougerie, R.; et al. Biodiversity inventories in high gear: DNA barcoding facilitates a rapid biotic survey of a temperate nature reserve. Biodivers. Data J. 2015, 3, e6313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alex Smith, M.; Fernández-Triana, J.L.; Eveleigh, E.; Gómez, J.; Guclu, C.; Hallwachs, W.; Hebert, P.D.N.; Hrcek, J.; Huber, J.T.; Janzen, D.; et al. DNA barcoding and the taxonomy of microgastrinae wasps (Hymenoptera, Braconidae): Impacts after 8 years and nearly 20,000 sequences. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2013, 13, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrcek, J. , Miller, S.E., Quicke, D.L. and Smith, M.A. Molecular detection of trophic links in a complex insect host-parasitoid food web. Mol Ecol Resour 2011, 11, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jousselin, E.; Van Noort, S.; Berry, V.; Rasplus, J.; Rønsted, N.; Erasmus, J.C.; Greeff, J.M. one fig to bind them all: host conservatism in a fig wasp community unraveled by cospeciation analyses among pollinating and nonpollinating Fig wasps. Evolution (N. Y). 2008, 62, 1777–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babendreier, D.; Koku Agboyi, L.; Beseh, P.; Osae, M.; Nboyine, J.; Ofori, S.E.K.; Frimpong, J.O.; Attuquaye Clottey, V.; Kenis, M. The efficacy of alternative, environmentally friendly plant protection measures for control of fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda, in maize. Insects 2020, 11, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, S.; Pavithra, H.B.; Kalleshwaraswamy, C.M.; Shivanna, B.K.; Maruthi, M.S.; Mota-Sanchez, D. Field efficacy of insecticides for management of invasive fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) (lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on maize in India. Florida Entomol. 2020, 103, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, R.K.; Brown, R.; Cartwright, B.; Cox, D.; Dunbar, D.M.; Dybas, R.A.; Eckel, C.; Lasota, J.A.; Mookerjee, P.K.; Norton, J.A.; et al. Emamectin Benzoate: A novel Avermectin derivative for control of Lepidopterous pests. In Proceedings of the 3rd international workshop: The management of diamondback moth and other crucifer pests; 1997; pp. 171–177. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L.A.D.; Mansingh, A. The insecticidal and acaricidal actions of compounds from Azadirachta indica (A. Juss.) and their use in tropical pest management. Integr. Pest Manag. Rev. 1996, 1, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Kanwar, R.K.; Sehgal, A.; Cahill, D.M.; Barrow, C.J.; Sehgal, R.; Kanwar, J.R. Progress on Azadirachta indica based biopesticides in replacing synthetic toxic pesticides. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.S.; Idrees, A.; Majeed, M.Z.; Majeed, M.I.; Shehzad, M.Z.; Ullah, M.I.; Afzal, A.; Li, J. Synergized toxicity of promising plant extracts and synthetic chemicals against fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Pakistan. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, A.; Qadir, Z.A.; Afzal, A.; Ranran, Q.; Li, J. Laboratory efficacy of selected synthetic insecticides against second instar invasive fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Larvae. PLoS One 2022, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulashie, S.K.; Adjei, F.; Abraham, J.; Addo, E. Potential of neem extracts as natural insecticide against fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2021, 4, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisay, B.; Simiyu, J.; Malusi, P.; Likhayo, P.; Mendesil, E.; Elibariki, N.; Wakgari, M.; Ayalew, G.; Tefera, T. First report of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), natural enemies from Africa. J. Appl. Entomol. 2018, 142, 800–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kfir, R. Parasitoids of the African stem borer, Busseola fusca (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), in South Africa. Bull. Entomol. Res. 1995, 85, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valerio, A.A.; Whitefield, J.B.; Kole, M. Parapanteles rooibos, n. Sp. (Hymenoptera: Braconidae: Microgastrinae): The first record of the genus from the African continent. Zootaxa 2005, 855, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisay, B.; Simiyu, J.; Mendesil, E.; Likhayo, P.; Ayalew, G.; Mohamed, S.; Subramanian, S.; Tefera, T. Fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda infestations in East Africa: Assessment of damage and parasitism. Insects 2019, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abang, A.F.; Fotso Kuate, A.; Nanga Nanga, S.; Okomo Esi, R.M.; Ndemah, R.; Masso, C.; Fiaboe, K.K.M.; Hanna, R. Spatio-temporal partitioning and sharing of parasitoids by fall armyworm and maize stemborers in Cameroon. J. Appl. Entomol. 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniço, A.; Mexia, A.; Santos, L. First report of native parasitoids of fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda Smith (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Mozambique. Insects 2020, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osae, M.Y.; Frimpong, J.O.; Sintim, J.O.; Offei, B.K.; Marri, D.; Ofori, S.E.K. Evaluation of different rates of Ampligo insecticide against fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith); Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in the coastal savannah agroecological zone of Ghana. Adv. Agric. 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruska, A.J. Fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) management by smallholders. CAB Rev. Perspect. Agric. Vet. Sci. Nutr. Nat. Resour. 2019, 14, 0–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, M.; Shimalis, T. Outbreak, distribution and management of fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda J. E. Smith in Africa: The status and prospects. 2019, 1–16.

- Nboyine, J.A.; Asamani, E.; Agboyi, L.K.; Yahaya, I.; Kusi, F.; Adazebra, G.; Badii, B.K. assessment of the optimal frequency of insecticide sprays required to manage fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda J. E Smith) in maize (Zea mays L.) in northern Ghana. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2022, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatments | Category | Active ingredients | Application rate (per 20L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated control | - | - | |

| Beauveria bassiana (Bb) | Biopesticide | Beauveria bassiana spores | 20 g |

| General Insecticide Cocktail (GIC) | Biopesticide | Combination of biopesticides | 20 g |

| Metarhizium anisopliae (Ma) | Biopesticide | Metarhizium anisopliae spores | 20 g |

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 7 (Ma ICIPE 7) | Biopesticide | Metarhizium anisopliae strain ICIPE 7 | 20 ml |

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 78 (Ma ICIPE 78) | Biopesticide | Metarhizium anisopliae strain ICIPE 78 | 20 ml |

| Nimbecidine | Botanical | Azadirachtin 0.03% EC | 120 ml |

| Roket® | Synthetic insecticide | Profenofos 40% + Cypermethrin 4% EC | 30 ml |

| Amdocs | Semi-synthetic insecticide | Emamectin benzoate 2% + Abamectin 1% | 35 ml |

| 2020 | |||||

| Location | Treatments | FAW Leaf damage score | Damage incidence (%) | ||

| 2020A | 2020B | 2020A | 2020B | ||

| Lira | Amdocs | 1.4 ± 0.104d | 2.8 ± 0.521bc | 89.3 ± 2.931b | 89.3 ± 4.789 |

| Roket® | 2 .0 ± 0.138c | 2.5 ± 0.462cd | 97.3 ± 1.427a | 88.8 ± 5.836 | |

| Beauveria bassiana | 2.2 ± 0.222bc | 2.7 ± 0.516bc | 93.3 ± 3.105a | 86.5 ± 6.284 | |

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 2.4 ± 0.318ab | 3.3 ± 0.551ab | 92.5 ± 3.508a | 89.8 ± 4.953 | |

| Nimbecidine | 2.1 ± 0.274c | 1.9 ± 0.297d | 94.5 ± 2.922a | 86.0 ± 5.799 | |

| Control | 3.1 ± 0.485a | 3.7 ± 0.829a | 94.0 ± 3.453a | 85.3 ± 6.732 | |

| Mean | 2.2 | 2.8 | 93.5 | 87.6 | |

| SE | 0.1418 | 0.2317 | 2.0741 | 4.4713 | |

| X2 | 38.24 | 28.89 | 11.93 | 1.24 | |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.03577 | 0.9406 | |

| Wakiso | Amdocs | 2.0 ± 0.173c | 2.1 ± 0.116c | 95.3 ± 2.392 | 97.0 ± 2.334 |

| Roket® | 3.3 ± 0.126b | 2.3 ± 0.154c | 99.0 ± 0.585 | 96.8 ± 1.508 | |

| Beauveria bassiana | 4.8 ± 0.392a | 3.4 ± 0.514ab | 99.5 ± 0.344 | 95.0 ± 2.460 | |

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 4.7 ± 0.657a | 3.8 ± 0.580ab | 98.8 ± 0.714 | 94.3 ± 4.505 | |

| Nimbecidine | 4.5 ± 0.378a | 3.1 ± 0.363b | 99.3 ± 0.547 | 97.5 ± 2.251 | |

| Control | 5.2 ± 0.674a | 4.3 ± 0.697a | 99.8 ± 0.250 | 96.0 ± 2.422 | |

| Mean | 4.1 | 3.2 | 98.6 | 96.1 | |

| SE | 0.2666 | 0.2238 | 0.5582 | 1.3911 | |

| X2 | 62.29 | 40.98 | 9.02 | 2.79 | |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.1084 | 0.7327 | |

| 2021 | |||||

| Location | Treatments | FAW Leaf damage score | Damage incidence (%) | ||

| 2021A | 2021B | 2021A | 2021B | ||

| Lira | Amdocs | 3.6 ± 0.203d | 2.9 ± 0.529c | 100 ± 0.000 | 100 ± 0.000 |

| Roket® | 4.6 ± 0.299c | 3.4 ± 0.348bc | 100 ± 0.000 | 100 ± 0.000 | |

| General Insecticide Cocktail | 5.9 ± 0.623a | 4.5 ± 0.055a | 100 ± 0.000 | 100 ± 0.000 | |

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 7 | 5.3 ± 0.505b | 4.3 ± 0.077a | 99.8 ± 0.250 | 99.8 ± 0.250 | |

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 78 | 5.4 ± 0.620b | 4.6 ± 0.144a | 99.5 ± 0.500 | 100 ± 0.000 | |

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 5.6 ± 0.658ab | 4.8 ± 0.163a | 99.8 ± 0.250 | 100 ± 0.000 | |

| Beauveria bassiana | 5.2 ± 0.549b | 4.7 ± 0.101a | 99.8 ± 0.250 | 100 ± 0.000 | |

| Nimbecidine | 4.2 ± 0.326cd | 4.2 ± 0.101ab | 100 ± 0.000 | 100 ± 0.000 | |

| Control | 5.8 ± 0.586ab | 4.7 ± 0.163a | 100 ± 0.000 | 100 ± 0.000 | |

| Mean | 5.1 | 4.2 | 99.9 | 100.0 | |

| se | 0.1897 | 0.1190 | 0.0713 | 0.0278 | |

| X2 | 59.66 | 62.12 | 5.09 | 8.0 | |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.7484 | 0.4335 | |

| Wakiso | Amdocs | 1.5 ± 0.075d | 2.1 ± 0.269c | 94.5 ± 3.097 | 98.5 ± 0.896 |

| Roket® | 1.7 ± 0.139d | 2.9 ± 0.174bc | 93.5 ± 3.366 | 97.5 ± 1.333 | |

| General Insecticide Cocktail | 3.7 ± 0.624ab | 4.3 ± 0.485a | 94.0 ± 3.004 | 99.3 ± 0.547 | |

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 7 | 3.0 ± 0.344c | 4.0 ± 0.517a | 97.3 ± 1.559 | 98.8 ± 1.018 | |

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 78 | 3.1 ± 0.530bc | 3.7 ± 0.409ab | 94.3 ± 2.816 | 98.3 ± 1.271 | |

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 3.7 ± 0.701ab | 3.7 ± 0.442ab | 93.5 ± 3.346 | 97.0 ± 2.334 | |

| Beauveria bassiana | 3.7 ± 0.569abc | 3.5 ± 0.299ab | 93.5 ± 3.405 | 98.0 ± 1.376 | |

| Nimbecidine | 3.0 ± 0.512c | 3.7 ± 0.495ab | 94.8 ± 3.023 | 98.8 ± 0.801 | |

| Control | 4.0 ± 0.664a | 4.4 ± 0.628a | 95.0 ± 2.487 | 97.0 ± 1.598 | |

| Mean | 3.0 | 3.6 | 94.5 | 98.1 | |

| SE | 0.1987 | 0.1641 | 1.6969 | 0.5914 | |

| X2 | 61.55 | 53.49 | 0.93 | 3.28 | |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.9986 | 0.9159 | |

| 2020 | |||||

| Location | Treatments | Number of larvae per 20 plants | Percentage larval infestation (%) | ||

| 2020A | 2020B | 2020A | 2020B | ||

| Lira | Amdocs | 3.6 ± 1.381b | 4.0 ± 1.154 | 15.0 ± 7.756b | 18.8 ± 9.337 |

| Roket® | 8.1 ± 1.644a | 3.3 ± 0.853 | 30.0 ± 8.339a | 16.0 ± 8.745 | |

| Beauveria bassiana | 6.9 ± 1.423a | 3.7 ± 1.093 | 28.5 ± 9.146a | 17.5 ± 9.429 | |

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 9.3 ± 2.123a | 4.8 ± 1.252 | 35.3 ± 11.411a | 23.0 ± 11.941 | |

| Nimbecidine | 7.4 ± 1.257a | 1.5 ± 0.759 | 30.3 ± 6.771a | 7.30 ± 4.617 | |

| Control | 10 ± 1.629a | 6.4 ± 1.546 | 41.3 ± 8.962a | 30.0 ± 14.869 | |

| Mean | 7.5 | 3.9 | 30.0 | 18.8 | |

| SE | 0.667 | 0.475 | 3.6042 | 4.0374 | |

| X2 | 15.78 | 9.99 | 15.30 | 10.02 | |

| P value | 0.007517 | 0.07536 | 0.009151 | 0.07458 | |

| Wakiso | Amdocs | 5.4 ± 1.570c | 4.7 ± 1.326c | 22.8 ± 10.639c | 21.3 ± 11.011c |

| Roket® | 14.4 ± 2.173b | 5.4 ± 1.022bc | 52.0 ± 6.430b | 25.5 ± 7.144bc | |

| Beauveria bassiana | 23.0 ± 3.064a | 8.6 ± 1.491ab | 72.3 ± 11.669a | 40.3 ± 10.676ab | |

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 22.4 ± 2.630ba | 10.5 ± 1.781ab | 73.3 ± 7.475a | 48.0 ± 15.287ab | |

| Nimbecidine | 20.6 ± 2.332ab | 7.9 ± 1.270ab | 73.8 ± 6.835a | 37.8 ± 10.364ab | |

| Control | 26.4 ± 2.728a | 12.8 ± 1.915a | 83.5 ± 4.650a | 56.3 ± 13.773a | |

| Mean | 18.7 | 8.3 | 62.9 | 38.2 | |

| SE | 1.173 | 0.651 | 4.8702 | 4.8796 | |

| X2 | 40.77 | 17.10 | 43.94 | 17.79 | |

| P value | <0.0001 | 0.004319 | <0.0001 | 0.003216 | |

| 2021 | |||||

| Location | Treatments | Number of larvae per 20 plants* | Percentage larval infestation (%) | ||

| 2021A | 2021B | 2021A | 2021B | ||

| Lira | Amdocs | 6.3 ± 1.975 | 5.6 ± 2.272 | 27.5 ± 16.924 | 19.3 ± 15.986 |

| Roket® | 9.1 ± 2.130 | 6.1 ± 2.045 | 39.3 ± 15.928 | 24.3 ± 16.166 | |

| General Insecticidal Cocktail | 12 .0± 2.589 | 11.6 ± 2.722 | 47.8 ± 18.677 | 40.0 ± 17.491 | |

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 7 | 10.8 ± 2.269 | 9.7 ± 2.151 | 45.3 ± 16.777 | 35.8 ± 15.455 | |

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 78 | 9.5 ± 2.359 | 11.2 ± 2.330 | 37.8 ± 16.310 | 41.8 ± 17.368 | |

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 10.4 ± 2.310 | 12.6 ± 2.595 | 43.0 ± 16.525 | 45.5 ± 18.931 | |

| Beauveria bassiana | 8.9 ± 2.017 | 11.4 ± 2.437 | 38.3 ± 15.439 | 43.5 ± 17.851 | |

| Nimbecidine | 7.9 ± 2.128 | 9.9 ± 2.176 | 33.0 ± 15.903 | 37.3 ± 15.362 | |

| Control | 11.4 ± 2.130 | 10.8 ± 2.669 | 48.5 ± 16.646 | 37.5 ± 14.984 | |

| Mean | 9.6 | 9.9 | 40.0 | 36.1 | |

| SE | 0.734 | 0.797 | 5.0985 | 5.1790 | |

| X2 | 7.92 | 6.54 | 7.59 | 7.15 | |

| P value | 0.4418 | 0.5868 | 0.4746 | 0.5204 | |

| Wakiso | Amdocs | 0.5 ± 0.170d | 3.2 ± 0.978c | 2.3 ± 1.335d | 15.0 ± 9.279c |

| Roket® | 2.1 ± 1.183cd | 5.3 ± 0.692bc | 7.5 ± 2.739cd | 25.0 ± 3.558bc | |

| General Insecticidal Cocktail | 6.2 ± 1.265a | 14.6 ± 2.567a | 27.3 ± 8.922a | 52.3 ± 11.802a | |

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 7 | 3.1 ± 1.072bc | 10.2 ± 1.889ab | 13.5 ± 5.665bc | 38.3 ± 11.474ab | |

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 78 | 3.6 ± 1.150abc | 11.1 ± 1.690ab | 15.3 ± 7.218abc | 44.3 ± 9.097ab | |

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 6.1 ± 1.434ab | 10.3 ± 1.857ab | 25.3 ± 9.790ab | 39.3 ± 8.241ab | |

| Beauveria bassiana | 5.4 ± 1.326ab | 10.0 ± 1.141ab | 22.3 ± 8.276ab | 39.8 ± 3.221ab | |

| Nimbecidine | 3.7 ± 1.069abc | 10.3 ± 2.362abc | 16.8 ± 6.785abc | 37.8 ± 11.722abc | |

| Control | 8.3 ± 2.016ab | 16.0 ± 2.534a | 29.5 ± 11.65ab | 56.8 ± 8.791a | |

| Mean | 4.3 | 10.1 | 17.7 | 38.7 | |

| SE | 0.447 | 0.668 | 2.6362 | 3.2852 | |

| X2 | 31.41 | 37.27 | 30.83 | 37.41 | |

| P value | 0.000119 | <0.0001 | 0.0001504 | <0.0001 | |

| Location | Insecticide treatment | Number of egg batches | Number of adults* | |||||||

| 2020A | 2020B | 2021A | 2021B | 2020A | 2020B | 2021A | 2021B | |||

| Lira | Amdocs | 12.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 | |

| Roket® | 11.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 9.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Beauveria bassiana | 19.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | ||

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 11.0 | 6.0 | 2.0 | 6.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 7 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 78 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | ||||||

| General Insecticidal Cocktail | 6.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Nimbecidine | 11.0 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | ||

| Control | 2.0 | 7.0 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Total | 66 | 26 | 35 | 42 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 5 | ||

| Wakiso | Amdocs | 19.0 | 14.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | |

| Roket® | 16.0 | 7.0 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | ||

| Beauveria bassiana | 14.0 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 15.0 | 8.0 | 2.0 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | ||

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 7 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 78 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | ||||||

| General Insecticidal Cocktail | 4.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Nimbecidine | 17.0 | 7.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | ||

| Control | 11.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 7.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Total | 92 | 45 | 22 | 32 | 19 | 4 | 9 | 14 | ||

| Overall total | 158 | 71 | 57 | 74 | 26 | 6 | 14 | 25 | ||

| Location | Treatments | Grain yield (t/ha) | Yield advantage over control (%) | ||||||

| 2020A | 2020B | 2021A | 2021B | 2020A | 2020B | 2021A | 2021B | ||

| Lira | Amdocs | 8.6 ± 0.627 | 5.1 ± 0.206 | 4.3 ± 0.370 | 5.1 ± 0.328 | 7.5 | -13.6 | 38.7 | 27.5 |

| Roket® | 7.8 ± 0.392 | 6.1 ± 0.136 | 4.3 ± 0.385 | 4.0 ± 0.683 | -2.5 | 3.4 | 38.7 | 0.0 | |

| General Insecticidal Cocktail | 4.3 ± 0.398 | 3.6 ± 0.142 | 38.7 | -10.0 | |||||

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 7 | 3.3 ± 0.095 | 3.9 ± 0.718 | 6.5 | -2.5 | |||||

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 78 | 4.1 ± 0.116 | 3.7 ± 0.206 | 32.3 | -7.5 | |||||

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 9.3 ± 0.544 | 6.0 ± 0.499 | 4.3 ± 0.608 | 3.6 ± 0.606 | 16.3 | 1.7 | 38.7 | -10.0 | |

| Beauveria bassiana | 9.5 ± 0.460 | 6.0 ± 0.389 | 4.2 ± 0.501 | 3.2 ± 0.674 | 18.8 | 1.7 | 35.5 | -20.0 | |

| Nimbecidine | 8.8 ± 0.660 | 5.0 ± 0.238 | 3.1 ± 0.531 | 4.1 ± 0.287 | 10.0 | -15.3 | 0.0 | 2.5 | |

| Control | 8.0 ± 0.420 | 5.9 ± 0.296 | 3.1 ± 0.303 | 4.0 ± 0.466 | |||||

| Mean | 8.67 | 5.68 | 3.88 | 3.906 | |||||

| SE | 1.110 | 0.404 | 0.649 | 1.010 | |||||

| Lsd | 2.519 | 1.519 | 2.0302 | 2.532 | |||||

| %cv | 12.17 | 11.182 | 20.769 | 25.729 | |||||

| P value | 0.202 | 0.085 | 0.125 | 0.442 | |||||

| Wakiso | Amdocs | 2.8 ± 0.966 | 6.2 ± 0.496 | 6.4 ± 0.595 | 5.5 ± 0.391 | 21.7 | 19.2 | -9.9 | 10.0 |

| Roket® | 2.8 ± 0.501 | 4.5 ± 0.539 | 6.1 ± 0.659 | 6.0 ± 0.850 | 21.7 | -13.5 | -14.1 | 20.0 | |

| General Insecticidal Cocktail | 6.3 ± 0.616 | 5.7 ± 0.458 | -11.3 | 14.0 | |||||

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 7 | 7.4 ± 0.638 | 5.6 ± 0.448 | 4.2 | 12.0 | |||||

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 78 | 6.9 ± 0.861 | 5.8 ± 0.670 | -2.8 | 16.0 | |||||

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 2.4 ± 0.526 | 6.0 ± 0.507 | 7.0 ± 0.290 | 5.4 ± 1.098 | 4.3 | 15.4 | -1.4 | 8.0 | |

| Beauveria bassiana | 2.9 ± 0.873 | 5.5 ± 0.825 | 7.3 ± 0.392 | 6.0 ± 0.264 | 26.1 | 5.8 | 2.8 | 20.0 | |

| Nimbecidine | 3.1 ± 0.533 | 5.8 ± 0.891 | 6.7 ± 0.866 | 6.6 ± 0.272 | 34.8 | 11.5 | -5.6 | 32.0 | |

| Control | 2.3 ± 0.415 | 5.2 ± 1.124 | 7.1 ± 0.550 | 5.0 ± 0.997 | |||||

| Mean | 2.70 | 5.515 | 6.81 | 5.732 | |||||

| SE | 1.787 | 2.355 | 1.603 | 1.812 | |||||

| Lsd | 3.195 | 3.668 | 3.190 | 3.391 | |||||

| %cv | 49.36 | 27.825 | 18.591 | 23.482 | |||||

| P value | 0.933 | 0.652 | 0.823 | 0.881 | |||||

| Order and Family | Species | Location | Host Stage Attacked |

Species with the Closest Nucleotide Sequence Match |

Percent Identity, and Reference GenBank Accession Number and iBoL Entries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hymenoptera: Platygastridae |

Telenomus remus Dixon | Wakiso and Lira | Eggs | Telenomus remus | 100% (ON923739.1) [30] |

| Hymenoptera: Eurytomidae | Eurytomidae sp. | Wakiso | Egg/Larval | Eurytoma asphodeli | 87.16% KT623736.1 [41] |

| Hymenoptera: Braconidae | Coccygidium luteum | Wakiso and Lira | Larvae | Coccygidium luteum | 99.64% MT784187 [36] |

| Coccygidium sp | Wakiso and Lira | Larvae | Coccygidium sp | ||

| Cotesia icipe | Wakiso and Lira | Larvae | Cotesia icipe | 100% MN900735.1 [27], 100% MT780217 [36] | |

| Parapanteles sp. | Wakiso | Larvae | Parapanteles athamasae | 100% HM397613.1 [42] | |

| Chelonus sp. | Wakiso and Lira | Egg/Larval | Chelonus insularis | 97.42% XM_035078068 | |

| Dolichogenidea sp. | Wakiso | Larval | Dolichogenidea sp. | 93.28% JF271344.1 [43] | |

| Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae | Micranisa sp | Wakiso | Larvae | Micranisa sp | 87.34% MK530760.1 [44] |

|

Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae |

Charops cf. diversipes | Wakiso and Lira | Larvae | Charops cf. diversipes | 100% (MT784182.1), 100% (MT784181.1), 100% (MT784179.1) [36], 100% (MT784183.1) [27] |

| Diptera: Tachinidae | Tachinidae sp. | Wakiso and Lira | Larvae/pupae | Tachinidae sp. | 99.35% (MT784176.1) [36] |

| Treatment | No. of Egg batches collected | No. of parasitoids |

No. of Egg batches parasitized | Overall parasitism (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020A | 2020B | 2020A | 2020B | 2020A | 2020B | 2020A | 2020B | |

| Lira | ||||||||

| Amdocs | 12 | 3 | 113 | 20 | 6 | 2 | 50.0 | 66.7 |

| Roket® | 11 | 2 | 65 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9.1 | 0.0 |

| Beauveria bassiana | 19 | 2 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 0.0 | 50.0 |

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 11 | 6 | 16 | 23 | 1 | 1 | 9.1 | 16.7 |

| Nimbecidine | 11 | 6 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 1 | 0.0 | 16.7 |

| Control | 2 | 7 | 14 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| Wakiso | ||||||||

| Amdocs | 19 | 14 | 77 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 15.8 | 0.0 |

| Roket® | 16 | 7 | 32 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 18.8 | 0.0 |

| Beauveria bassiana | 14 | 6 | 140 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 35.7 | 0.0 |

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 15 | 8 | 22 | 25 | 2 | 2 | 13.3 | 25.0 |

| Nimbecidine | 17 | 7 | 103 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 29.4 | 0.0 |

| Control | 11 | 3 | 63 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 18.2 | 0.0 |

| Treatment | No. of Egg batches collected | No. of parasitoids | No. of Egg batches parasitized | Overall parasitism (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021A | 2021B | 2021A | 2021B | 2021A | 2021B | 2021A | 2021B | |

| Lira | ||||||||

| Amdocs | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Roket® | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Beauveria bassiana | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 2 | 6 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 50.0 | 0.0 |

| Metarhizium anisopliae icipe 7 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Metarhizium anisopliae icipe 78 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| General Insecticidal Cocktail | 6 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 16.7 | 0.0 |

| Nimbecidine | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Control | 6 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Wakiso | ||||||||

| Amdocs | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Roket® | 1 | 6 | 20 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| Beauveria bassiana | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Metarhizium anisopliae icipe 7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Metarhizium anisopliae icipe 78 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| General Insecticidal Cocktail | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Nimbecidine | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Control | 2 | 7 | 22 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| Treatment and district | No. of larvae collected | No. of parasitoids |

Overall parasitism %) |

2020A | 2020B | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020A | 2020B | 2020A | 2020B | 2020A | 2020B | Chd | Chs | Col | Cos | Coi | Mic | Tas | Chd | Col | Cos | Coi | ||

| Lira | ||||||||||||||||||

| Amdocs | 4 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 25 | |||||||||||

| Beauveria bassiana | 14 | 47 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| Control | 50 | 52 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 | ||||||||||

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 31 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| Nimbecidine | 23 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| Roket® | 18 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| Wakiso | ||||||||||||||||||

| Amdocs | 7 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 42.9 | 0 | 14.3 | 14.3 | 14.3 | |||||||||

| Beauveria bassiana | 51 | 35 | 29 | 4 | 27.4 | 11.5 | 3.9 | 7.8 | 9.8 | 3.9 | 2.0 | 8.6 | 2.9 | |||||

| Control | 94 | 46 | 13 | 4 | 17.1 | 8.7 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 3.2 | 9.6 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 4.3 | 2.2 | ||||

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 52 | 40 | 12 | 0 | 23.0 | 0 | 3.8 | 11.5 | 5.8 | 1.9 | ||||||||

| Nimbecidine | 58 | 28 | 13 | 0 | 22.3 | 0 | 3.4 | 8.6 | 3.4 | 6.9 | ||||||||

| Roket® | 21 | 12 | 5 | 0 | 23.8 | 0 | 9.5 | 4.8 | 9.5 | |||||||||

| District and Treatment |

No. of FAW larvae collected |

No. of parasitoids | Parasitism (%) | 2021A | 2021B | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21A | 21B | 21A | 21B | 21A | 21B | Chs | Col | Cos | Coi | Tas | Chd | Chs | Col | Coi | Tas | |

| Lira | ||||||||||||||||

| Amdocs | 22 | 28 | 1 | 0 | 3.6 | 3.6 | ||||||||||

| Roket® | 43 | 67 | 3 | 0 | 4.5 | 1.5 | 3 | |||||||||

| Beauveria bassiana | 43 | 110 | 1 | 3 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 2.7 | ||||||||

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 62 | 107 | 1 | 3 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 1.8 | |||||||

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 7 | 44 | 88 | 4 | 0 | 4.5 | 4.5 | ||||||||||

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 78 | 51 | 124 | 3 | 0 | 2.4 | 2.4 | ||||||||||

| General Insecticidal Cocktail | 49 | 113 | 4 | 0 | 3.6 | 0.9 | 2.7 | |||||||||

| Nimbecidine | 28 | 81 | 2 | 0 | 2.4 | 2.4 | ||||||||||

| Control | 62 | 98 | 1 | 2 | 1.6 | 2 | 1.6 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Wakiso | ||||||||||||||||

| Amdocs | 11 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Roket® | 13 | 33 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | |||||||||

| Beauveria bassiana | 37 | 44 | 1 | 2 | 2.7 | 6.8 | 2.7 | 4.5 | 2.3 | |||||||

| Metarhizium anisopliae | 38 | 47 | 5 | 3 | 13.1 | 4.5 | 2.6 | 7.9 | 2.6 | 4.5 | ||||||

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 7 | 29 | 46 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2.2 | 2.2 | |||||||||

| Metarhizium anisopliae ICIPE 78 | 16 | 59 | 1 | 2 | 6.3 | 3.4 | 6.3 | 3.4 | ||||||||

| General Insecticidal Cocktail | 34 | 55 | 3 | 0 | 8.7 | 0 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 2.9 | |||||||

| Nimbecidine | 37 | 53 | 1 | 1 | 16.2 | 1.9 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 1.9 | |||||||

| Control | 40 | 58 | 3 | 4 | 7.5 | 6.8 | 7.5 | 3.4 | 1.7 | 1.7 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).