1. Introduction

Demographic projections suggest that by 2040 there will be 16.3 million cancer deaths worldwide with 27.5 million new instances of the disease. Data also show cancer caused 10 million deaths globally, with breast, lung, colon, rectal, prostate, skin, and stomach cancer being the most common types [

1,

2]. Cancers are highly heterogenous with many subtypes and molecular profiles and thus, present complex challenges. Tumor heterogeneity at cellular levels is related to genetic, and environmental factors. Lifestyle choices, modes of preventive strategies, and modalities of therapies for cancer patients also play roles in inducing tumor heterogenicity leading to chemotherapy resistance to various anticancer drugs including topo-active drugs [

3,

4,

5]. Chemotherapy cancer drug resistance arises from gene mutations, gene amplification, or epigenetic changes that influence the uptake, metabolism, or export of drugs from cells. Acquired resistance is influenced by genetics or environmental factors, intracellular and extracellular signaling pathways, as well as metabolic adaptations [

6,

7]. Due to these extreme challenges in therapy, both the understanding of the mechanisms of topo-active drugs resistance and innovative approaches to a successful therapy are urgently needed.

Topoisomerase enzymes are crucial enzymes involved in DNA replication, chromosomal segregation, transcription, and recombination. There are two classes: Topoisomerase I, which cleaves one DNA strand, and Topoisomerase II, which cuts simultaneously on both strands [

8,

9]. Camptothecin, an alkaloid, discovered in 1958 is an inhibitor of Topo I. FDA-approved derivatives like topotecan and irinotecan target Topo I, while Topo II inhibitors like anthracycline-based drug doxorubicin cause cytotoxic DNA double-strand breaks [

10,

11,

12]. While various topo-active drugs are extremely effective in the clinic and utilized to treat a wide variety of human tumors, invariably tumor cells develop resistance to these drugs, resulting in failure to therapy. Strategies to overcome this resistance, a concerted and understanding mechanisms of topo-active drugs resistance in cancer cells is well appreciated among basic scientists, pre-clinicians, and clinicians for better management of cancer patients.

One such basis for drug resistance is suggested to involve the ABC transporter protein family that regulates drug transport, with P-glycoprotein/ABCB1 being the most studied. Common multidrug resistance mechanisms include overexpression of ABC transporter that contributes to the efflux of topo-active drugs [

13,

14,

15,

16].

Hence, combinatorial approaches that can target both ABC transporters and Topo I and Topo II enzymes concomitantly may lead to better drug responsiveness.

Glutathione (GSH) is one of the most abundant low molecular weight non-protein thiols that immensely regulates the physiological levels of ROS and in turn mediates oxidative stress response during genotoxic drug responses [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. In the wake of topo-active drug resistance, modulation of GSH-mediated oxidative stress status in cancer cells is suggested as an important step to thwart drug resistance and achieve better drug responsiveness.

Genotoxic chemicals, e.g., topo-active drugs, induce enhanced DNA repair in cancer cells, allowing damaged cancer cells to survive and proliferate. Cancer cells develop resistance mechanisms to thrive during genotoxic insults by modulating DNA repair response pathways that enhance survival [

22,

23,

24,

25].

In immunotherapy-based resistance, the primary resistance to checkpoint inhibitors occurs due to both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, preventing immune response and antigen recognition [

26,

27,

28].

However, combining immune checkpoint inhibitors along with topo-active drugs is recommended as a potential approach to minimize resistance due to both immune checkpoint inhibitors and topo-active drugs.

Cancer stem-like cells (CSCs) are essential for tumour development, growth, and resistance [

29,

30,

31,

32]. Investigating CSC pathways that influence resistance against topo-active drugs may help develop combinatorial anticancer drug treatment avenues [

33,

34]. Increased lipid metabolism, glutaminolysis, glycolysis, mitochondrial biogenesis, and the pentose phosphate pathway are all aspects of metabolic reprogramming in cancer [

35,

36]. The Warburg effect and metabolic reprogramming are crucial events during the survival and resistance strategies by cancer cells against topo-active drugs [

37,

38,

39]. Therefore, holistic understanding at molecular, preclinical, and clinical levels for both metabolic adaptations and drug resistance due to topo-active drugs is needed at this time. We believe that this will open new forms of innovative approaches by combining metabolite mimetics with topo-active drugs to achieve better responsiveness and cancer cell killing.

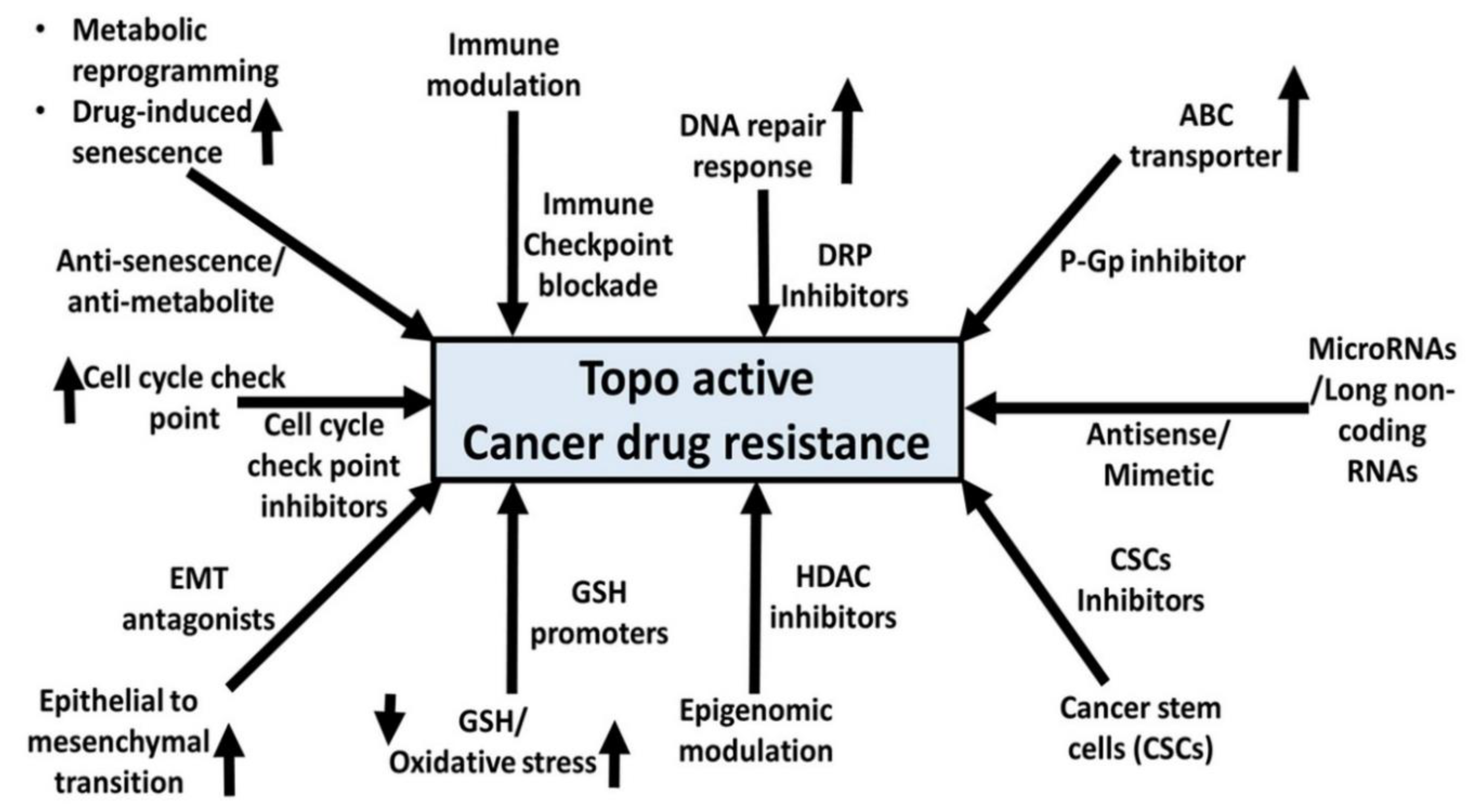

Based upon the lacunae within the comprehensive understanding of topo-active drug resistance in cancer cells, this review encapsulates fundamental, preclinical, and clinical insights about diverse adaptations undertaken by cancer cells at both molecular and cellular levels. These adaptations encompass but are not limited to ABC transporters, oxidative stress, DNA damage response mechanisms, immune heterogeneity, plasticity of cancer stem cells (CSCs), and metabolic reprogramming. Moreover, we extend prospective avenues for synergistic pharmacological strategies by combining small molecule inhibitors with topo-active agents. The overarching goal is to enhance the efficacy of cancer cell death while concurrently ameliorating adverse effects attributed to topo-active drugs.

2. Topoisomerases

DNA topoisomerases are essential enzymes for DNA replication, transcription, recombination, and chromatin remodeling because they control the topological status of the DNA double helix and cause either single-strand (Topo I) or double-strand (Topo II) DNA breaks [

40,

41,

42]. Topo I, a 100 kDa monomeric protein, is expressed by a single copy gene on chromosome 20q12-13.2 which must be phosphorylated for its catalytic activity. The topoisomerase I cleaves one strand of DNA. It is not an ATP-dependent enzyme (reverse gyrase is an exception). Type I topoisomerases can also be further divided into type IA and type IB enzymes based on whether the protein is linked at a 5′-phosphate or 3′-phosphate.

Topoisomerase II (topo II) is required for chromosome segregation and reprogramming replicons. Topo II inhibition impairs the entirety of DNA replication, accounting for replication protein A (RPA) stabilization onto ssDNA [

43]. Thus, topoisomerases have received a significant research attention, largely due to various agents e.g., irinotecan, topotecan, doxorubicin, and etoposide target these proteins [

44,

45].

3. Mechanisms of action of Topo-active drugs

Topoisomerase I (Topo I) and Topoisomerase II (Topo II), targets of many chemotherapeutic drugs, effect the structure of chromatin (a complex combination of DNA and proteins) within cells and play a crucial role in maintaining the structure and organization of DNA for proper cellular functioning in cancer cells. The drugs that actively inhibit (block the functioning of) Topo I and Topo II have distinct effects on chromatin. In the case of drugs that target Topo I, they cause a distinctive molecular reaction within the chromatin of cells. These drugs lead to the creation of single-stranded breaks in the DNA strands that make up the chromatin [

46,

47,

48].

Topo I is now a preferred target of many chemotherapeutics in addition to being a crucial indicator to assess the proliferation state of many malignant cells. The two forms of Topo I inhibitors—Topo I poison and Topo I suppressor—both specifically operate at the level of the topoisomerase I-DNA complex and promote DNA breakage. Similar to topotecan, the Topo I poison acts after the enzyme cleaves DNA and prevents ligation. The overexpression of Topo I is correlated with an increase in the susceptibility of tumor cells to Topo I toxins. Shikonin and other topo I suppressors, on the other hand, block topoisomerase I from interacting with the DNA cleavage site, preventing the completion of the remaining steps in the catalytic cycle. In tumor cells with minimal Topo I expression, Topo I suppressor activity is higher. As a result, these two types of inhibitors exhibit distinct anti-cancer therapeutic strategies [

48,

49,

50].

Topo I, which alters the topographic state of duplex DNA through single-strand breaks and relegation, is identified as the molecular target of Camptothecin (CPT) [

51]. CPT is known to stabilize the covalently bounded Topo I DNA complex (also known as cleavable complex). The CPT Inhibits Topo I by blocking the reconnecting stage of the cleavage/relegation reaction. [

52]. Nemorubicin (MMDX), a third-generation anthracycline derivative, that uses the mechanism of intercalation in DNA, is a topoisomerase I inhibitor [

53]. It is active in various tumor models, including multi-resistant cell lines, and is not cardiotoxic at therapeutic levels [

54,

55,

56].

Topoisomerase poisons, Camptothecin (CPT) and related compounds, are key drugs for treating solid tumors. The unique semisynthetic CPT derivative, containing a bulky piperidino side chain at the 10 position, is known as Irinotecan. This side chain can be cleaved enzymatically by the enzyme carboxylesterase to 7-ethyl-10-hydroxy-campthothecin (SN38), which is a potent Topo I inhibitor [

10], [

51], [

57,

58]. Topotecan and SN38 both stabilize Top1-DNA cleavage complexes (Top1cc), which are then converted into DNA damage during DNA replication and transcription [

59], inhibiting DNA strand from re-ligation, causing permanent replication fork arrest and cell death [

24].

Topoisomerase II (Top II, Top2) inhibitors have demonstrated strong clinical effectiveness against several human malignancies [

47]. Top II poisons and catalytic inhibitors are the two class of drugs target Top II. The first class consists of the most popular chemotherapeutic drug for treating human cancers, doxorubicin and etoposide (VP-16) that effectively inhibits transcription and replication and, causing apoptosis in cancer cells by forming a ternary complex with DNA and Top II [

49]. Cancer cells, in part, engage autophagy to ingest and recycle damaged macromolecules and produce energy to survive. Inhibitors of Top II have also shown excellent therapeutic efficacy against a variety of cancers by preventing transcription and replication leading to death in cancer cells. Mammalian Top2 cleaves the DNA duplex, creating the catalytic intermediate Top2 cleavage complex (Top2cc), to overcome DNA topological problems including supercoils and catenates [

60]. A derivative of nalidixic acid, 2-(1-Ethyl-7-methyl-4-oxo-1,4-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carbonyl)-N-(m-tolyl)- hydrazinecarbothioamide [

61], a potent inhibitor of both Topo IIα and Topo IIβ, induces cell cycle arrest at the G2-M phase, leading to inhibition of cell proliferation and apoptosis [

61,

62].

Nitric oxide (NO), a physiological signalling molecule, is involved in a variety of cellular activities, including cell growth, survival, and death. NO plays a substantial role in the detoxification of etoposide (VP-16) and affects functions of several critical cellular proteins, including topoisomerases [

63,

64]. A series of ciprofloxacin chalcones hybrids have been synthesized as potential anticancer agents. These hybrids exhibited significant antiproliferative activity against colon cancer cells (HCT116) and leukemia (RPMI-8226 and SR). They also showed inhibitory activity against Topo-I, Top-II, and tubulin polymerization. These new CP hybrids can be used as promising leads for further studies as multi-targeted anticancer agents for colorectal carcinoma [

65].

Resistant cells have been shown to contain altered drug binding sites on DNA or topoisomerases, leading to both decreased drug binding and inhibition of activity. Mutant epigenetic enzymes have altered enzymatic activity, which may impact the extent of histone modifications directly or indirectly. This can affect chromatin shape and function, modifying target gene expression and eventually leading to chemoresistance. Recent research has suggested that unreported mutation sites in the DOT1 domain of DOT1L are linked to lung cancer treatment resistance. It is important to note that mutations occur not just in enzymatic domains but also in non-catalytic sites [

65,

66].

Studies suggest that secondary metabolites produced by plants such as alkaloids, terpenoids, polyphenols, and quinones, can be used as an alternative to synthetic topoisomerase inhibitors for their ability to block DNA topoisomerases to overcome drug resistance and other epigenetic changes [

65,

66,

67]. Terpenoids are a diverse class of plant natural products. Taxol, a complex polyoxygenated diterpenoid was isolated from the Pacific yew Taxus brevifolia and is used in the treatment of ovarian, metastatic breast, lung, and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Taxotere is a semisynthetic derivative that is a potent anticancer drug due to improved water solubility and microtubule polymerization, leading to apoptosis [

67]. Ellipticine an alkaloid derived from the

Ochrosia elliptica labil has been previously approved as a treatment for the metastatic disease of breast cancer. Additionally, several carbazole derivatives from the species have demonstrated inhibitory activity against Topo I and Topo II [

61,

68]. It has been suggested that the tubulin inhibitors vinblastine and Taxol trap the Top1cc form in the early phase of apoptosis and leading to apoptotic process [

69].

4. Tumor Heterogeneity and Topo active drugs

Chemotherapy resistance, a prevalent issue in cancer treatment including against Topo active drugs is a complex phenomenon and often linked to the tumor heterogeneity at various molecular and cellular levels [

70,

71]. Tumor heterogeneity is known to exist at both levels of intra and inter-tumoral heterogeneity. Intra-tumoral heterogeneity is influenced by factors like genome doubling, mutational burden, and somatic copy number alterations. Intra-tumoral heterogeneity can manifest as genetic, epigenetic, neo-antigenic, metabolic, and tumor-microenvironment (TME) heterogeneity [

72]. Acidic microenvironment of tumors causes drug protonation, reduced cellular uptake, high MDR1 and P-gp gene expression, increased MDR proteins, angiogenesis, metastasis, hypoxic conditions, gene downregulation and reduced chemotherapeutic efficacy [

73,

74,

75,

76].

Studies have shown that the components of the tumor microenvironment (TME) such as cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF) and immune suppression cells participate in tumor progression. CAF has been reported to alter the extracellular matrix (ECM) during the growth of tumors. The secreted components responsible for the remodelling of the ECM are TGF-beta, HGF, certain interleukin, and metalloproteinases [

77,

78]. Also, cancer cells showing resistance to treatment including Topo active drugs are known to be supported by these secreted factors of TME such as CAF and immune suppression cells [

79,

80,

81,

82,

83].

Tumor heterogeneity also exists in the form of genetic tumor heterogeneity e.g., chromosomal instability which is known to cause cancer genome changes such as aneuploidy. Studies show aneuploidy patterns in various cancers influence tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes-related drug resistance induced by topo active [

84,

85,

86,

87]. Often, large chromosomal alterations, seen as macro-evolutionary events, can potentially lead to the development of drug resistance to topo-active agents [

71,

88].

Tumor cells exhibit high epigenetic and phenotypic plasticity, potentially causing drug-tolerant persistence and resistance through stable non-genetic changes in gene expression [

89,

90,

91]. Global epigenetic changes, like CpG island hypomethylation, may increase cell-to-cell variability in cancer cells due to genetic and microenvironmental heterogeneity [

87], [

92,

93]. The DNA methylome is a key epigenetic change in human cancers, involving promoter CpG island DNA hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes and global DNA hypomethylation. Cytosine methylation can also impact tumorigenicity through other mechanisms, as 5-methylcytosine is mutagenic and can undergo spontaneous hydrolytic deamination, leading to C → T transitions [

94,

95,

96,

97].

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is a heterogeneous disease with multiple molecular subtypes. Jiang et al., carried out a clinical study that demonstrated a novel way of developing targeted TNBC therapy. Monoclonal antibodies, small molecule inhibitors, antibody-drug conjugates, and immunotherapy are the four broad categories of targeted therapies, usually taken orally or intravenously. This study involved 7 different treatments targeting against 4 immunomodulatory subtypes of TNBC, amongst the targeted therapies with nab-paclitaxel against PD-1 and anti-VEGFR therapies gave the highest objective response rate (ORR) [

98]

. Using High-throughput technologies it was identified that the TNBC have developed diverse histone modifications, resulting in resistance to topo-active drug containing chemotherapies [

99].

5. Mutation of target enzymes

Resistance has been shown to arise from mutations in the genes encoding the topoisomerases. These mutations lead to altered enzyme structures that are less sensitive to inhibition by drugs. In SN38-resistant HCT116 clones three new TOP1 mutations were identified located in the core subdomain III (p.R621H and p.L617I), linker domain (p.E710G), and were packed together at the interface between these two domains. TOP1 mutations in SN38-resistant HCT116 cells, did not alter TOP1 expression or activity, however, they decreased TOP1-DNA cleavage complexes and double-stranded break formation [

100]. The Adriamycin-resistant breast cancer cells (OVCAR-8) cells were highly resistant to etoposide (VP-16), showing decreased DNA strand breaks [

101].

The resistance mechanisms involve multiple factors e.g., reduced drug uptake, topoisomerase II sensitivity, and decreased phosphorylation [

101,

102] which can reduce the binding affinity of topoisomerase I and II inhibitors, respectively. Humans possess two genes that encode for type II topoisomerases namely hTOP2A on chromosome 17 and hTOP2B on chromosome 3 [

103]. The encoded proteins, each serve a distinct but overlapping function. The expression of hTOP2α in proliferating cells is essential for cell viability, while hTOP2β is expressed in quiescent cells which are involved in the regulation of transcription [

104,

105,

106]. A somatic mutation in topoisomerase II seen in human tumors results in a mutator phenotype. This mutation had a specific pattern referred to as ID_TOP2α which is associated with genomic rearrangements and potential oncogenes in known driver genes [

106]. Another type of mutation can make the enzyme insensitive to inhibitors and reduce its DNA cleavage activity, increasing drug resistance frequency. These mutations are common but limited due to homozygous requirements, with specific properties being complex and context-dependent [

107].

Numerous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) was observed in both topo I and topo II coding genes. A point mutation at different regions of the topo I gene was observed, which resulted in resistance to Camptothecin derivatives. The replacement of Phe-361 or Asn-722 by Ser in topoisomerase I of cancer cells made cells insensitive against drugs like topotecan. The mutation of Ala-653 by Pro in the linker domain of topoisomerase I led to resistance against Camptothecin-related drugs [

14]

Mutations in the topo II genes have been described in many resistant cell lines. Usually, these mutations occur mainly at two places A: the nucleotide binding domain and B: the tyrosine comprised domain participating in covalent binding of topo II to the nicked DNA. The replacement of Arg 486 to Lys in topo II genes leads to resistance against the drug amsacrine in the human leukemia (HL-60) cell line [

108]. Deletion of Ala 429 resulted in the development of resistance against etoposide in the human melanoma (FEM) cell line [

109]. However, further evidence demonstrating that these mutations in the resistant cell lines are responsible for the drug resistance was confirmed utilizing the yeast expression model [

110].

Although research on these Topo I and II mutants are instructive, there appears to be some disagreement concerning their functional relevance. Therefore, it has been recommended to perform additional research on the genetic-based mechanisms of drug resistance in cancer cells for a better understanding and to circumvent resistance [

111,

112].

6. Altered drug metabolisms and topo active drugs

In addition to deregulated transportation of drugs, research suggest that the alterations in drug metabolic pathways can lead to the inactivation of topo-active drugs. This could contribute to decreased binding and or formation of inactive metabolites inducing resistance to topo-active drugs [

63], [

113,

114,

115,

116].

Metabolic conversion of DOX leads to formation of alcohol metabolites e.g., doxorubicinol (DOXol) as well as DOX deoxy aglycone and DOXol hydroxy aglycone, resulting in altered toxicity and decreased antineoplastic activity [

113,

115]. In contrast, reductive metabolism of DOX mediated by NADPH results in the formation of reactive species with enhanced cytotoxicity [

117,

118]. A study suggested the implications of polymorphism of cytochrome P450 1B1 gene to the reduced sensitivity to DNA-interacting anticancer agents, alkylators, Camptothecin, topoisomerase II inhibitors [

119]. An interesting study supported that

.NO-derived species can detoxify VP-16 through direct nitrogen oxide radical attack. This may contribute to increased drug resistance in VP-16-treated cancer patients [

63].

Pathania et al., have indicated that phase-II drug metabolism enzymes, including uridine diphospho-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs), glutathione-S-transferases (GSTs), dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenases (DPDs) and thiopurine methyltransferases (TPMTs), play significant roles in the induction of resistance to topo-active drug [

120]. Genetic variants of phase I and II enzymes, including cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 and uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A are associated with the metabolism of irinotecan and etoposide. These metabolic changes potentially may influence the outcome of efficacy and toxicity [

121,

122].

Thus, the efficacies of topo-active drugs and other anticancer drugs could be related to the generation of intracellular metabolized products which modulate both the therapeutic and toxic properties of top-active drugs. Non-enzymatic and enzymatic biotransformation of topo-active drugs by glutathione has also been suggested to potentially contribute towards anticancer drug responses [

116].

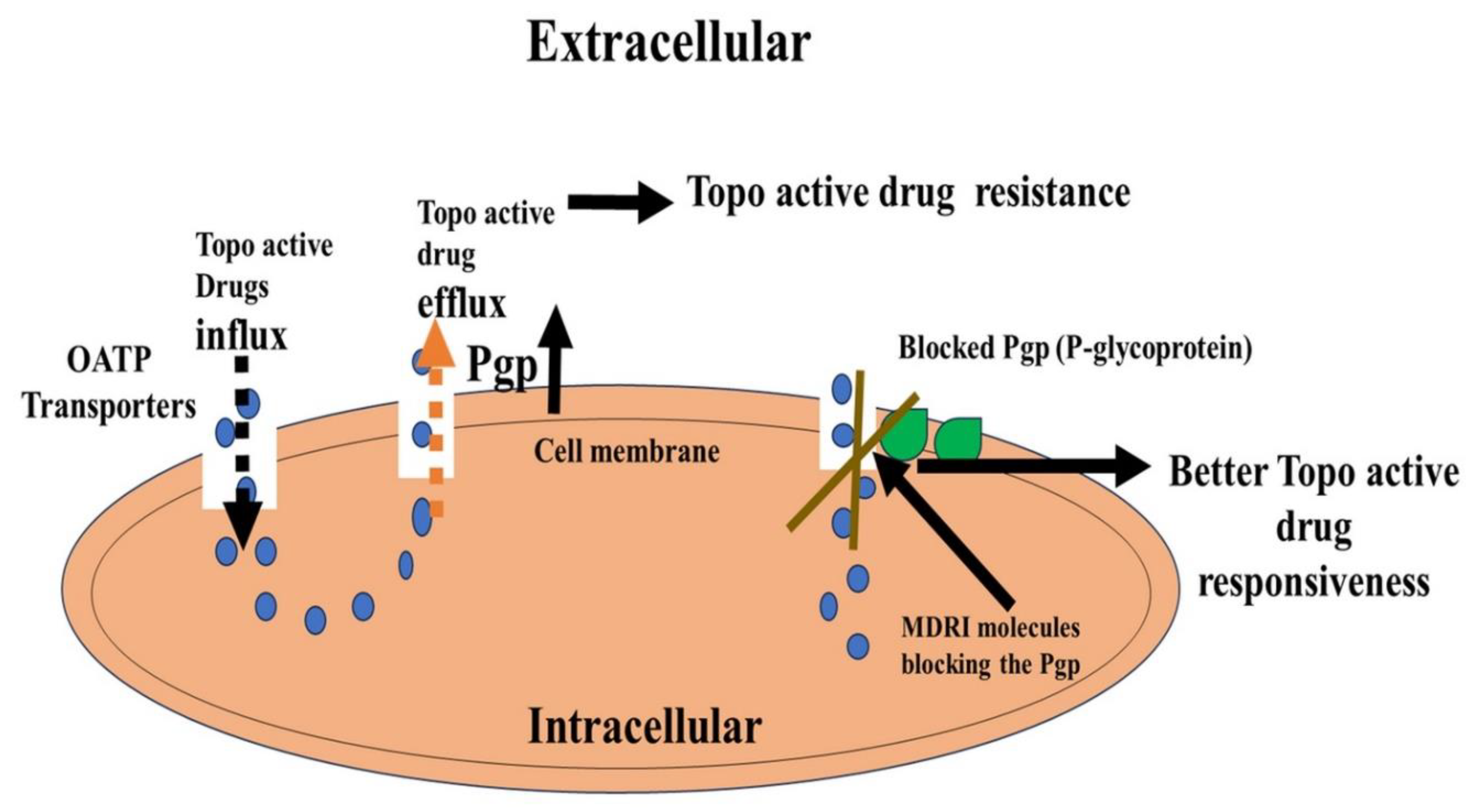

7. ABC transporters-mediated resistance of Topo drugs

In cancer cells, multidrug resistance (MDR) can significantly reduce the effectiveness of chemotherapy and raise the risk of patient death. Numerous studies have indicated that drug transport is a carefully regulated process, which was later found to be regulated by members of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter protein family. P-glycoprotein (P-gp)/ABCB1 was the first ABC transporter discovered [

13,

123,

124] and is most studied. The function of this protein is to decrease intracellular drugs from cancer cells in an energy dependent process, resulting in decreased drug concentrations. Thus, overexpression of ABC transporters in cancer cells leads to drug resistance and multi-drug resistance (MDR). Some efflux proteins (P-glycoprotein or ABCB1, multidrug proteins or MRP or ABCC, breast cancer resistance protein or BCRP or ABCG2) are expressed on the luminal membrane and are responsible for the extrusion of their substrates from the BBB endothelial cells back into blood circulation, reducing the central bioavailability of many drugs [

125]. Membrane proteins of the ABC transporter superfamily extrude a wide range of substrates across cellular membranes. Since the discovery of P-gp, an increasing number of chemotherapeutic drugs have been identified as being transported by ABC transporters. Based on sequence similarity and structural organization, the ABC transporter family has been divided into seven subfamilies [

13,

126].

Several topo-active drugs, e.g., doxorubicin, etoposide, Camptothecin and its related derivatives have shown to be substrates for ABC transporters and presence of these transporters in tumors have been shown to result in resistance to these drugs. Cancer patients with resistant disease often show presence of ATP-binding cassette transporters, conferring resistance to targeted chemotherapy.

ABC transporters undergo conformational changes during substrate translocation, requiring a comprehensive understanding of their inner workings. Advances in single-particle cryogenic electron microscopy have provided information on ABC transporter architecture, supramolecular assemblies, and mechanistic insights into their mode of action [

127]. SPP1(secreted phosphoprotein 1), also known as osteopontin (OPN), is upregulated in malignancies, and linked to treatment resistance [

128]. Exogenous OPN treatment increases ABCB1 and ABCG2 transporter expression, increasing resistance to topotecan and doxorubicin [

129].

Overexpression of ABCG2 (or Breast Cancer Resistance Protein/BCRP) in tumors also resulted in resistance. ABCG2 is an ATP-binding cassette efflux transporter that has been shown in cultured cells to cause resistance to a variety of clinically used anticancer drugs, including topotecan and irinotecan [

130,

131]. Inhibition of ABC transporters by elacridar and tariquidar, small molecule inhibitors, resulted in synergistic apoptosis and increased drug sensitivity in an etoposide- or SN-38-resistant SCLC (Small Cell Lung Cancer) cells [

132]. BCRP, an ABC half-transporter breast cancer resistance protein, is overexpressed in cancer cell lines treated with topotecan, or mitoxantrone which leads to resistance to Camptothecin derivatives like irinotecan and SN-38 [

133,

134].

ABC transporter modulators have the potential to improve the efficacy of anticancer drugs [

13,

135]. However, MDR1's development as a therapeutic target has not been unsuccessful [

136]. Recently, the hydrolytically activatable PF108-[SN22]2 has demonstrated pharmacophore enhancement, increased tumor uptake, and optimal carrier-drug association, making it a promising therapeutic strategy for patients with multidrug-resistant disease [

137,

138]. A summarized flow mode is presented in

Figure 1 [

135,

136,

137,

138].

8. GSH depletion and Topo-drug resistance

Glutathione is an important molecule in the context of cytotoxicity induced by topoisomerase-active drugs. Glutathione, a tripeptide composed of three amino acids (glutamate, cysteine, and glycine), can influence the cytotoxicity of these drugs through various mechanisms, including detoxification, conjugation, and drug inactivation. Recent research underscores the multifaceted involvement of GSH as a regulator spanning cell differentiation, ferroptosis, apoptosis, proliferation, and anticancer responsiveness. Notably, GSH perturbations correspond to tumor genesis, advancement, and treatment response, where increased GSH concentrations within neoplastic cells correlate with enhanced chemoresistance [

19,

139,

140]. Molecular modifications in the GSH antioxidant system and disturbances in GSH homeostasis have established links to resistance against cancer therapeutics. Among various potential molecular mechanisms that potentiate resistance to topo-active drugs in cancer cells, depletion of GSH and elevation of ROS leading to oxidative damage are observed. A clear association between GSH concentration and topo-active drug efficacies is shown by the enhanced anticancer effects of doxorubicin-loaded GSH-Nano sponges in the cancer cells that lead to high GSH content [

141,

142].

Data also suggested that inhibitors of GSH biosynthesis reduced the effects of topo-active drug etoposide while N-Acetylcysteine, a promoter of GSH synthesis, increased anticancer effects of Topo active drugs [

143]. Furthermore, nanoparticle loaded GSH was shown to reduce the resistance to topo-active drugs DOX and Camptothecin in cancer cells [

144,

145,

146,

147]. Topoisomerase I-active drug CPT has been reported to reduce the level of intracellular ROS whereas supplementation by N-acetylcysteine or glutathione decreased ROS production that potentially could modulate the sensitivity of CPT [

148]. Some topoisomerase-active drugs, e.g., CPT, induce the formation of ROS. Glutathione can detoxify these ROS, reducing the drug-induced oxidative stress and limiting the cytotoxic effects. It is interesting to note that topotecan has been found to enhance both ROS formation and glutathione-drug conjugation in tumor cells, resulting in synergistic cytotoxicity with ascorbic acid, a source for H2O2 formation in cells [

149,

150].

An interesting paper further supported the implications of reduced GSH-mediated oxidative stress levels toward topotecan-mediated cell death in liver cancer cells [

32]. Even antioxidant such as neobavaisoflavone is proposed to enhance depletion of GSH level which in turn may help in the potentializing of the doxorubicin effect in U-87 MG cells [

151]. Recently, data indicated that irinotecan may worsen hepatic oxidative stress by inducing formation of ROS and lipid peroxides while simultaneously lowering GSH, SOD, and CAT in cancer cells [

152]. As topo-active drugs cause decreases levels of GSH, newer derivatives with redox-sensitive targeted delivery which will maintain the GSH level in treated cancer cells are recommended to avoid drug resistance and desirable apoptotic cell death [

153,

154].

The development of MDR is suggested to result from the maintenance of H2O2 and GSH levels. Hence, monitoring GSH levels can efficiently detect the development of drug resistance and guide patient response to therapy [

143,

155]. A recent finding also suggested that a small molecule, IND-2 (4-chloro-2-methylpyrimido [1″,2″:1,5] pyrazolo[3,4-b] quinolone), significantly elevated the level of ROS in prostate cancer cells and also blocked the activity of TOPO II [

156]. This study suggested that modulation of ROS level is associated with enhanced apoptotic cell death in the case of an inhibitory approach towards TOPO II.

In line with oxidative stress, the enzyme phosphodiesterase 10A (PDE10A) is known to be elevated in cancer cells and this enzyme hydrolyzes cAMP and cGMP. The inhibition of this enzyme is linked to the proliferation of tumor cells. PDE10A deficiency or inhibition reduces the apoptosis, malfunction, and atrophy caused by DOX. Recent findings suggest that inhibition of PDE10A attenuates DOX-induced cardiotoxicity and inhibits cancer growth, and thus may be a promising strategy in cancer therapy [

157,

158].

Overall, the role of glutathione in topo-active drug cytotoxicity and resistance is complex and context-dependent. It can either enhance or reduce the effectiveness of these drugs, depending on the specific drug, the cellular environment, and the balance between drug-induced damage and cellular defence mechanisms. Understanding these interactions is important for the development of more effective cancer therapies and strategies to overcome drug resistance.

9. DNA damage response pathways and topo-active drug resistance

Many malignancies, including those that grow slowly or quickly, have developed chemotherapeutic resistance attributed to DNA integrity and replication. This increase in DNA damage has allowed a growing population of damaged cells to persist. Research shows that the most prevalent type of damage is caused by the inhibition of DNA topoisomerase II. The primary repair pathways for double-strand breaks (DSBs) are homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), whereas nucleotide excision repair (NER) is distinguished by the removal of lesions that cause significant structural distortions in the DNA double helix [

159,

160,

161,

162]. Studies have demonstrated the role of the HR and NHEJ pathways in the repair process for topoisomerase-induced damage.

However, some topo II inhibitors create DNA adducts, inter-strand crosslinks, and ROS-induced DNA damage, and evidence suggests that other DNA repair pathways are involved in removing chemotherapeutic drug damage. Various drug resistance mechanisms have been implicated to influence the success of cancer treatment, including DNA repair, which works by removing lesions before they become cytotoxic to the cells [

163,

164,

165,

166,

167]. In humans, TOP3A is linked to DNA replication forks, and a "self-trapping" TOP3A mutant (TOP3A-R364W) generates replication and induces DNA damage and genomic instability [

168]. One of the most essential DNA repair enzymes is tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase. Topoisomerase and tyrosine help reconnect and regenerate damaged DNA by forming a covalent intermediate of a tyrosine residue at the end of fragmented DNA [

169,

170].

Topo-active drugs are genotoxic and induce a huge DNA damage repair response pathway that potentially contributes to drug resistance in treated cancer cells. Therefore, a large number of studies suggest the relevance of combinatorial and dual targeting of topoisomerases and DNA repair proteins such as PARP, ATM, Rad51, and MGMT (DNA repair protein, O (6)-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferases). Previous studies have indicated a role of MGMT in the emergence of drug resistance of irinotecan, SN-38, and DX-8951f. Elevated expression of MGMT gene decreased drug sensitivity while inhibition of MGMT resulted in enhanced sensitivity of cancer cells to Topo I active drugs [

171,

172].

Topo-active drugs like topotecan and mitoxantrone (MXT) cause DNA strand breaks that in turn phosphorylate histone H2AX, which may not involve ds DNA breaks. However, double-strand DNA breaks are formed during DNA repair and analysis of H2AX phosphorylation may be indicative of extent of the repair process [

173]. Data also indicate the involvement of DNA repair proteins e.g., a mutation in BRCA1 may be related to drug responsiveness of topo-active drugs. Hence, combinations of small molecular inhibitors against specific DNA repair proteins and cytotoxic drugs such as Topo active drugs could be combined to achieve sucessful combinatorial anticancer drug approaches [

174,

175]. Topotecan- and mitoxantrone (MXT)-dependent double-strand breaks also induce activation of DNA repair proteins, ATM and Chk2, in human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells and combinatorial approaches of using small molecule inhibitors of ATM and Chk2 with Topo active drugs, therefore, were investigated as a novel anticancer approach for better sensitivity and reduced toxicity [

176,

177]. Evidence of the combinatorial approach is further supported by the combined effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors erlotinib or gefitinib with CPT that resulted in the increased anticancer effects in breast cancer cells [

178]. Additional research indicated that combinatorial role of Topo II inhibitors (idarubicin, daunorubicin, mitoxantrone, etoposide) and selinexor (a selective inhibitor of XPO1) was more effective in AML [

179].

Another finding linked the action of andrographolide analogue 3A.1, a novel topo II inhibitor in cancer cells, as an inducer of apoptosis by inducing cleavage of DNA repair protein poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases-1 (PARP-1) [

180]. A study also reported on the design of a series of 4-amidobenzimidazole acridines and other drugs as a dual inhibitor of both PARP and topoisomerase in breast cancer cells with significantly enhanced cell death [

181,

182]. There are suggestions for concomitant targeting of Tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase enzymes and Topo I/Topo II to explore new avenues of anticancer agents [

183].

There is emerging combinatorial approaches to target DNA repair proteins such as Ku70 and Topo II as effective anticancer approaches by designing platinum (II) complexes such as [PtCl(NH3)2(9-(pyridin-2-ylmethyl)-9H-carbazole)]NO3 (OPPC), [PtCl(NH3)2(9-(pyridin-3-ylmethyl)-9H-carbazole)]NO3 (MPPC), and [PtCl(NH3)2(9-(pyridin-4-ylmethyl)-9H-carbazole)]NO3 (PPPC) [

184]. 2-Amino-Pyrrole-Carboxylate (2-APC) dramatically increases doxorubicin cytotoxicity and promotes apoptosis in cancer cells at non-toxic concentrations. This was due to 2-APC's ability to inhibit DNA damage repair by reducing the amount of Rad51 recombinase via proteasomal degradation [

185,

186].

10. Metabolic reprogramming and topo active drug resistance

Metabolic reprogramming is a key feature of cancer characterized by increased lipid metabolism, glutaminolysis, glycolysis, mitochondrial biogenesis, and pentose phosphate pathway among others. In addition to energy, these metabolic programs provide cancer cells with essential metabolites to support large-scale biosynthesis, continued proliferation, and other key processes of tumorigenesis [

35]. The Warburg effect gives an illustration of a metabolic characteristic under cell-autonomous regulation by oncogenes in numerous proliferating cancer cells and tumors. The Warburg effect is a preference for glycolysis and lactate production in the presence of oxygen. Therapeutic opportunities may arise when cancer cells develop fixed dependencies on the Warburg effect or other conserved pathways, while non-malignant cells adapt to their inhibition [

37].

In the case of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), Petrella

et al reported metabolic changes with an immediate arrest of glycolysis after treatment with etoposide, followed by a gradual recovery with EMT induction and repopulation. Furthermore, it was found that oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) was initially elevated but then decreased, however, it remained above control levels. This study provides new insights into cancer cell energy metabolism during topo-active drug therapy and provides potential pharmacological targets for the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer [

187].

Through metabolic processes, nutrients are transformed into energy and vital chemicals for cells. PI3K/AKT and MAPK signaling pathways influence tumor development and immunity. Tumor development is stopped by simultaneous suppression of metabolic pathways like glycolysis and PI3K/AKT/mTOR. Immune cells change their energy consumption whereas tumor cells alter their metabolism to promote development. Tumors compete with immune cells for nutrients, thus affecting immune responses. Dual signaling pathway inhibitors targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR and other signaling pathways are being developed to improve cancer therapy [

188,

189].

Cancer cells frequently experience altered metabolic states, which may increase the aggressiveness of the tumor [

190]. Clinical studies that target metabolic pathways have shown promise, but their success depends on careful consideration of toxicity and combination therapy. As the common metabolic reprogramming routes in cancer cells are focused, it is stressed that metabolic regulators should be utilized with caution due to their potential toxicity [

191].

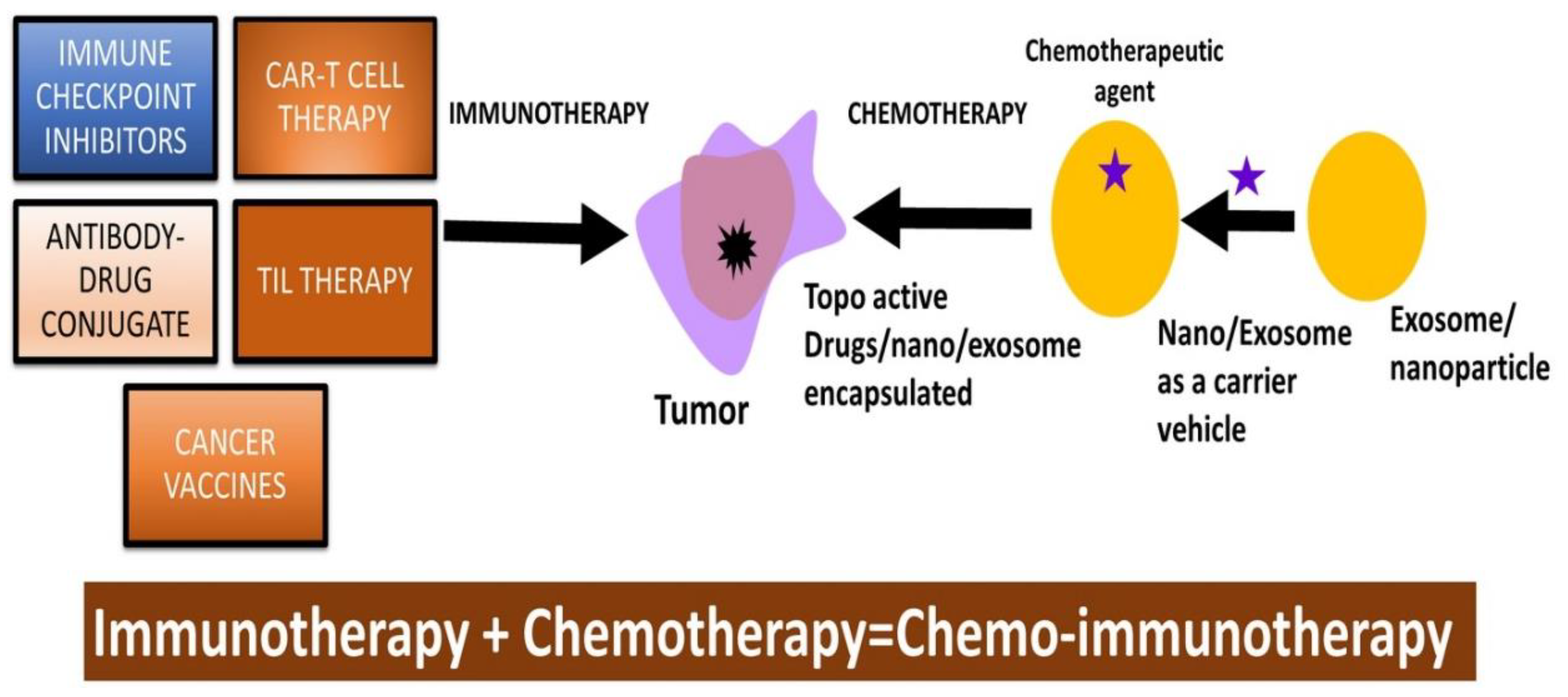

11. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and topo-active drugs

Checkpoint inhibitors (CPI) are extensively utilized in immunotherapy for the treatment of certain cancers. The immune system utilizes checkpoints to distinguish between normal cells and or diseased cells. However, cancer cells are known to exploit these checkpoints molecules to evade detection by the immune system. CPI can block these checkpoint molecules, therefore, allowing the immune system to recognize and kill cancer cells more effectively.

As CPI are active in a variety of histological cancers, and have extensive response, CPI therapy have been taken into consideration for the treatment of metastatic and chemotherapy-resistant malignancies [

192]

. The physiological immune response to tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) is hindered by the interaction between immunological checkpoints and their ligands, which negatively alters T-cell activity. In the TME of many human malignancies, immune checkpoints, and their responsive ligands are frequently increased, and they represent significant barriers to the beginning of an efficient anti-tumor immune response. [

193,

194]

.

The two most prominent checkpoint-blocking strategies are those that target the interaction between programmed cell death 1 (PD-1 or CD279) and programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1 or CD274 or B7 homolog 1) and inhibit the cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4 or CD152) [

195]. During the induction phase of the immune response, co-stimulation of CD80/CD86 via CD28 delivers crucial stimulus signals that enable T-cell proliferation and efficient differentiation [

196]. The ligands for PD1 (PDL1 and PDL2) are related proteins found in both cancer cells and antigen-presenting cells [

197]. PD1 is an immune cell-specific surface receptor. In the presence of a ligand, PD1 lowers the threshold for apoptosis, blunts T-cell receptor signalling to cause energy, and generally depletes T cells [

198,

199]. PDL1 expression is upregulated in some tumour cells, which results in a greater suppression of T-cell activity in favour of the survival of the tumour cells. A PD1-PDL1 link can be blocked by a monoclonal antibody against PD1, which will increase the immune system's response and stop tumour progression [

200,

201].

In immunotherapy, potentiation of antitumor therapy is suggested by blocking programmed death-1 (PD-1) or its ligand (programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) using various classes of inhibitors including anti-PD1 antibodies [

202]. However, uses of topo-active drugs such as SN-38 in combination with anti-PD1 antibodies are being explored at preclinical and clinical levels [

203,

204]. Another example of drug conjugate is reported by combining an immune checkpoint TDO inhibitor with irinotecan which can inhibit TDO enzyme and induce apoptosis in HepG2 cancer cells [

205]. This class of topo-active drugs e.g., irinotecan, have demonstrated their enhancing effects on T cell-based immunotherapy in melanoma [

206].

Various clinical trials have been reported utilizing antibody-drug conjugates such as Sacituzumab govitecan and SN-38 targeting against human trophoblast cell-surface antigen 2 (Trop-2), expressed in most breast cancers [

207,

208]. In these new cancer therapies, antibody-drug conjugates are explored as drug payload against Topo I and target selective tumor antigens, predominantly TROP-2. Emerging evidence supports the link between chemotherapeutic drugs as topo-acting drugs such as mitoxantrone may upregulate major histocompatibility class I (MHC-I) antigen processing and presentation [

209,

210]. In turn, a proposition on the combinatorial approaches that can combine topo-acting drugs and immune checkpoint inhibitor therapies (ICIT) such as PD-1/PD-L1 [PD-(L)1] blockade is warranted [

209,

210,

211,

212]. Another topo-active drug, SN-38, has shown augmenting efficacies in immune-checkpoint blockade therapies in a syngeneic tumor model [

204,

213].

An interesting observation suggested the use of the chemo-immunotherapeutic approach by combining topo-active drug teniposide and anti-PD1 antibodies as a better approach for enhanced antitumor efficacy in multiple types of mouse tumor models [

214]. The link between topo-active drugs and anti-PD1 antibodies is suggested to involve the STING (stimulator of interferon genes) pathway [

215]. A recent publication also emphasized the importance of antibody–drug conjugate by utilizing a human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-targeted antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) trastuzumab-L6 and novel DNA topoisomerase I inhibitor MF-6 for achieving better immunogenic tumor cell death [

216,

217].

Pancreatic cancer is highly resistant to topo active drugs due to their ability to induce intrinsic physical and biochemical stresses to cause an increase in interstitial fluid pressure, vascular constriction, and hypoxia. Immunotherapies, e.g., therapeutic vaccines, immune checkpoint inhibition, CAR-T cell therapy, and adoptive T cell therapies are also ineffective against pancreatic cancers due to their highly immunosuppressive nature. Drug-resistant and immunosuppressive nature could be overcome by the development of nanocarrier-based drug formulations [

218]. PEGylation, conjugation of polyethylene glycol (PEG) to drugs, has been employed in Doxil and Genexol-PM drug formulations that are FDA-approved nanocarrier drug formulations against PDAC and metastatic PDAC [

219]. The use of PLGA-NPs coated with Taxol led to 90% drug release, leading to decreased pancreatic tumor volume as compared to controls [

220]. Cationic poly-lysine NPs coated with HIF1alpha siRNA and GEM (gemstones) are used in siRNA-adjuvant GEM therapy in the treatment of pancreatic cancers. The chemo resistant and invasive nature of pancreatic CSCs is mediated by miRNA resulting in the manifestation of cancer recurrence and drug resistance [

221]. Micelles conjugated with GEM and miRNA mimetics were tested against pancreatic CSCs. The synergistic effect of GEM and miRNA mimetics showed decreased tumor growth in CSCs, GEM-resistant CSCs, and xenograft pancreatic cancer [

222]

Overall, therapy with checkpoint inhibitors is a significant advancement in cancer treatment, especially for treating melanoma, lung cancer, and kidney cancers (

Figure 2). While CPI have shown remarkable activities, they are not without adverse effects, as they can induce immune-related toxicity resulting from the overactivation of the immune system. These side effects are serious and could affect various organs and systems in the body, requiring close monitoring for potential side effects.

12. Topo-active drugs and cancer stem cells

Cancer stem cells (CSCs), also referred to as tumor-initiating cells, are a small fraction of tumor cells that are crucial for the development, growth, and resistance of tumors. The new CSCs, however, can be generated when therapeutic pressure and altered microenvironment are present and formed from non-CSCs or from senescent tumor cells following by therapy [

223]. Compared to non-CSCs, CSCs are more immune-resistant, and cancer immunosurveillance enhances certain populations of cancer cells with stem-like characteristics. For CSCs to maintain the tumorigenic process, CSC immune evasion is essential including elevated PD-L1 expression [

224,

225]. In addition to immune evasion, CSCs display plasticity in terms of favourable DNA repair pathways in response to genotoxic-mediated DNA damages. Therefore, the involvement of CSCs in the development of resistance against topo-active drugs is indicated and understanding pathways in CSCs that lead to resistance against topo-active drugs may be helpful to design combinational anticancer drug therapy.

In recent studies, several drugs with anti-CAFs (Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts), anti-cancer, and anti-CSC properties have been identified. Among the identified drugs aloe-emodin and digoxin exhibit anticancer and anti-CSC activity

in vitro and

in vivo, as demonstrated by the lung cancer PDX (Patient-Derived Xenograft) model. The single-cell transcriptomics analysis revealed that digoxin could suppress the CSC subpopulation and cytokine production in CAFs-cultured cancer cells [

226]. Furthermore, the combination of digoxin with chemotherapeutic drugs, including topo-active drugs results in an improved the therapeutic efficacy. It is possible that such combinations may overcome drug resistance mediated by topo-drugs and needs to be addressed in future studies.

The failure of standard cancer therapy, recurrence, and high mortality rate in the clinic is largely caused by the generation of tumour-initiating cells e.g., CSCs. Several signalling pathways including Wnt, Hedgehog (Hh), Notch, and PI3K/AKT/mTOR are aberrantly regulated in CSCs and interestingly, these signalling pathways are also involved directly or indirectly with resistance to topo-active drugs in cancer cells [

33]. In this context, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are reported to show adjustability to topoisomerase I and II inhibitors even after being exposed to high dosages of irinotecan or etoposide. Here, MSCs retain their capacity to distinguish between various cell types and effectively repair DNA double-strand breaks. The topoisomerase-resistant phenotype points to MSCs as possible therapeutic targets for addressing chemotherapy-induced bone marrow damage [

228]. Topo-II gene expression is varied between CSCs and non-CSCs in the glioma with higher levels present in CSCs. Silencing of Topo II has shown to induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in CSCs [

229]. This link between resistance and topoisomerase is clearly supported by the fact that dual treatment with Camptothecin-containing nanoparticle-drug conjugate and CRLX10, an inhibitor of HIF-1α, resulted in enhanced efficacy in breast cancer cells [

229,

230,

231].

Topo-active drug resistance is a significant problem in the treatment of cancer patients because the cancer cells develop mechanisms to thwart the effects of therapeutic drugs, giving rise to more aggressive and fit clones that worsen treatment. There are several CSC clones already present, and some of them can quickly adapt to changes in the tumor microenvironment (TME) and/or grow when exposed to radiation and chemotherapy [

223]. Targeting CSC subpopulations has been suggested to eliminate tumors and prevent their recurrence. Both ROS and RNS (reactive nitrogen species) are expertly managed by CSCs, and they use TME to their benefit. CSCs also have improved DNA repair capability, and the ability to turn off apoptotic pathways, leading to drug resistance [

223,

228,

232]. As a result, combating CSC drug resistance makes sense by using the proper medications to block both topoisomerases I and II [

233].

Recent developments in the field suggest that the utilization of topo-active drugs, such as doxorubicin and etoposide, in conjunction with an autophagy inhibitor, may lead to a favorable induction of cell death in drug-resistant CSCs (

Figure 3) [

33] [

224,

228,

234]. In addition, recent studies indicate that the deregulation of TOP2A is strongly linked to the growth and progression of CSC features with the involvement of Laminin-332 and YM-1 [

224].

DOX-resistant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) exhibited stem-related markers CD133 and OCT4 and showed strong canonical Wnt activity over DOX-sensitive cells [

235]

.

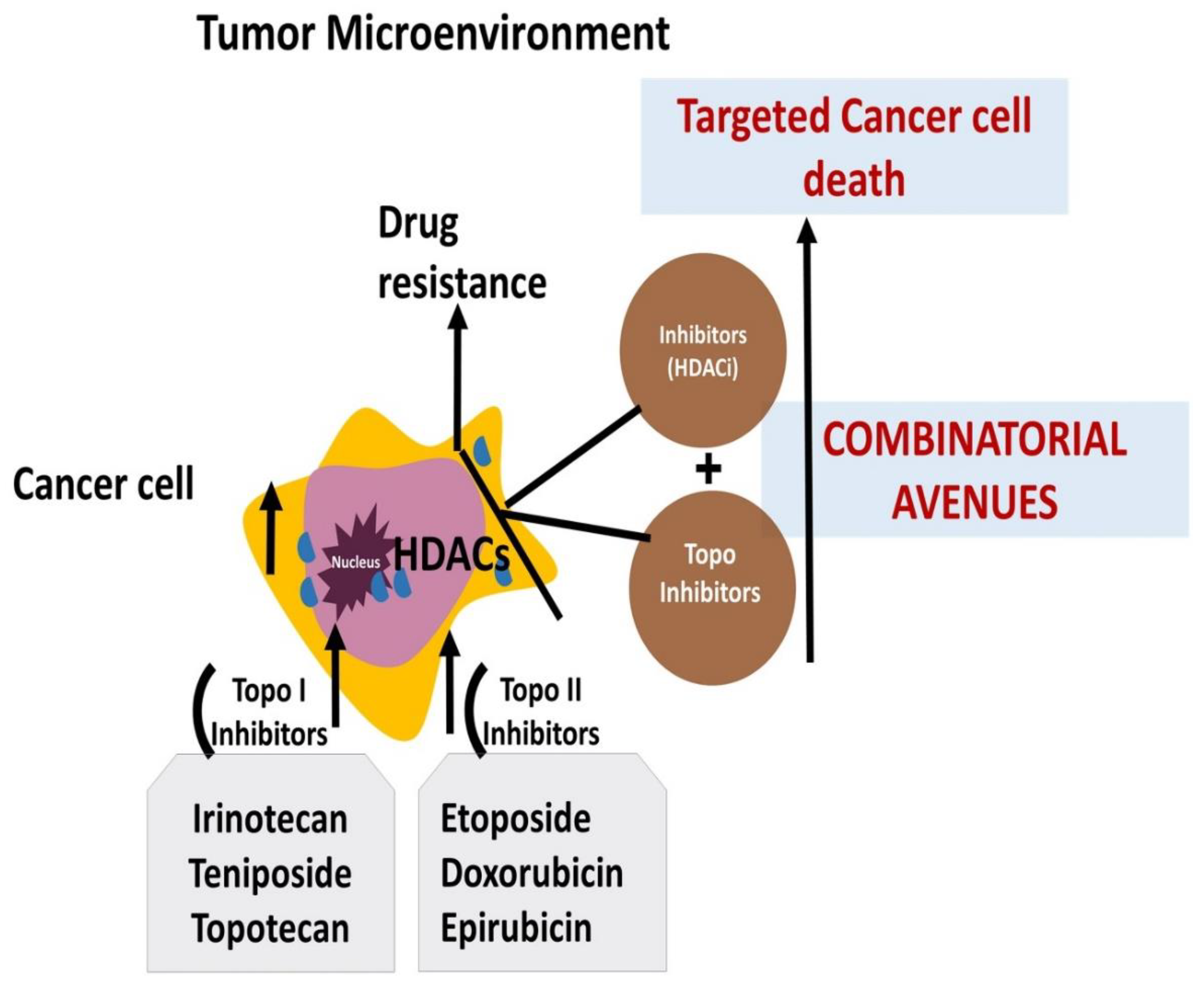

13. Epigenetic changes and Topo-active drugs

Perturbation of chromatin structure is observed in cancer-associated histone mutations, giving rise to chromatid remodeling, heightened histone exchange, and nucleosome displacement. Epigenetic changes occur through mechanisms such as DNA methylation, histone acetylation, and RNA interference. These processes serve as avenues for the occurrence of epigenetic modifications, contributing to the landscape of cancer development, progression, and cancer drug resistance [

236,

237,

238,

239].

Carcinogenesis involves genetic and epigenetic changes leading to cancer progression. Treatment strategies include cell cycle arrest, promoting apoptosis/autophagy, cell cycle control, tumor cell prevention, and immune response induction. Apigenin has demonstrated broad anticancer effects in various cancer types, including colorectal, breast, liver, lung, melanoma, prostate, and osteosarcoma. It inhibits cell proliferation, motility, immune response, and control of various protein kinases and signaling pathways including the PI3K/AKT, MAPK/ERK, JAK/STAT, NF-B, and Wnt/β-catenin pathways [

240].

In the epigenomic remodeling process, histone modification involves changes to histones, proteins around which DNA strands coil, encompassing the addition or removal of acetyl groups. The addition of acetyl groups, referred to as histone acetylation, serves to activate the corresponding chromosomal region, while its removal (deacetylation) leads to deactivation. Key enzymes in the regulation of gene expression are histone deacetylases (HDACs) [

12,

239].

The dynamic equilibrium of acetylation levels on histones’ conserved lysine residues, which controls chromatin remodeling and gene expression, is maintained by them. The connection between cancer and abnormal HDAC activity has been widely documented, and the inhibition of human tumor cell line proliferation by HDAC inhibitors has been demonstrated in vitro. Moreover, potent anti-tumor activity in human xenograft models has been observed with several HDAC inhibitors (HDACi), suggesting their potential as new cancer therapeutic agents [

241,

242].

In a typical cellular environment, HDACs play a role in promoting cell cycle progression by repressing gene transcription at the promoter level and direct deacetylation of important regulators of the cell cycle and also contribute to the development of cancer drug resistance. Novel strategies could be employed to enhance the therapeutic effectiveness of HDACi, potentially resulting in improved, targeted classes with reduced adverse effects. FDA-approved inhibitors like vorinostat and depsipeptide have demonstrated efficacy and safety in treating hematologic malignancies. However, treating both hematologic and solid tumors will likely involve combining HDACi with genotoxic drugs such as Topo-active drugs [

241,

243,

244].

Etoposide-resistant lung cancer cells have been shown to display elevated levels of histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4) and the concomitant treatment with both trichostatin A, (an HDAC inhibitor) and etoposide resulted in an enhanced cell death in lung cancer cells [

245]. Furthermore, combinations of pan HDAC inhibitor, panobinostat and topo-active drugs have demonstrated increased effects in cervical cancer cells [

246]. Results suggested that the combination of the HDACi vorinostat with DNA damaging agent topo I-active drug, SN-38, may also be beneficial and could result in enhanced cytotoxic effects [

247,

248].

The idea to develop small molecule agents that can work as dual inhibitors of both HDAC and Topo I/II have been explored [

249,

250,

251,

252,

253,

254,

255,

256,

257]. Kim et al. have also emphasized the importance of dual targeting by the combinatorial treatment of CI-994, an HDAC inhibitor with etoposide leading to synergistic anticancer effects through Topo II and Ac-H3 regulation [

258]. Studies on agents containing pyrimido [5,4-b] indole and pyrazolo[3,4-d] pyrimidine motifs as novel compounds indicated the relevance of dual inhibitors of HDAC and Topo II and such combinations have been suggested as a new avenue for enhanced anticancer responses [

259].

Thus, epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation and histone acetylation, can influence cancer cells to acquire resistance against various topo-active drugs [

248]. Modification leading to hypomethylation can either increase or decrease the sensitivity of cells against the topoisomerase inhibitors due to altered mechanisms. Also, it has been reported that the dysregulation of histone acetyltransferase (HAT) and histone deacetylases (HDACC) which plays a key role in regulating the level of acetylation in histone protein results in resistance against topo inhibitors (

Figure 4) [

12,

248,

249,

250,

251,

252,

253,

254,

255,

256,

257,

258,

259,

260].

14. Miscellaneous mechanisms of resistance and Topo-active Drug-induced senescence and drug resistance

Genotoxic drug-induced senescence is one of the many observed changes in cancer cells that correlate with drug responsiveness to various precision and targeted inhibitors, including topo- active drugs, immune checkpoint inhibitors, DNA repair protein inhibitors, and kinase inhibitors [

260]. Drug-induced senescence is often related to distinct forms of cell cycle arrest, telomere instability, and overall genomic instability.

As G2-M-phase cell cycle checkpoint play significant roles in topo-active drug-mediated responsiveness, inhibitor UCN-01 has been reported to modulate the activity of p53 which in turn potentiates toxicity in cancer cells [

261].

Furthermore, a different type of Topo I inhibitor, imidazoacridinone C-1311, and Topo II inhibitor SN 28049 have been reported to induce growth arrest and senescence in human lung cancer cells [

262,

263]

. Further studies have also shown that Topo I inhibitor SN-38 can cause the G2 arrest and lead to senescence via downregulation of Aurora-A kinase [

264,

265]

.

The relevance of the chromosome instability in cancer cells by topo-active drugs such as Topo2 inhibitor ICRF-193 was reported due to telomere dysfunction and cellular senescence [

66]. Taschner-Mandl

et al., have emphasized the action of low-dose topotecan to induce proliferative arrest and a typical senescence-associated secretome in cancer cells [

266]. Hao

et al. have also shown that TOP1 inhibitors such as irinotecan may lead to an elevation of drug-mediated senescence via the cGAS pathway [

267]. Topo-active drugs such as irinotecan modulate p53 activity and induce acetylation of several lysine residues within p53, leading to drug-induced senescence [

268]. The sequential combination of therapy-induced senescence and ABT-263 could shift the response to apoptosis. The administration of ABT-263 after either etoposide or doxorubicin also resulted in marked, prolonged tumor suppression in tumor-bearing animals. These findings support the premise that senolytic therapy following conventional cancer therapy may improve therapeutic outcomes and delay disease recurrence [

269].

Mercaptopyridine oxide, a new class of Topo II inhibitor, also demonstrated the activation of G2/M arrest and cellular senescence [

270,

271,

272]. Recent work has shown that doxorubicin treatment of cancer cells leads to the enrichment of miR-433 into exosomes, which in turn induces bystander senescence [

273]. Topo I inhibitors such as SN-38 and irinotecan have shown their abilities to induce G2 arrest and cellular senescence via modulation of activities of p21, p53, and Bcl-xL, Bcl-2 and PGC-1-related coactivator [

254,

273,

274]. These modulatory effects are associated with the drug responsiveness and potential relapse of tumors in cancer patients treated by Topo active drugs [

275,

276,

277,

278,

279,

280,

281,

282].

14.1. Regulatory RNAs and Topo active drugs

The interfering role of microRNAs and lncRNAs is suggested to modulate the level of Topo and Topo II enzymes that in turn related to the topo-active drug resistance in cancer cells. [

12] [

283,

284,

285,

286]. The regulatory role of microRNAs and lncRNAs is extensively reported and is associated with oncogenic as well as tumor suppressor roles in cancer cells. Previous studies have shown that the downregulation of Topo I observed in hepatic cancer cells is due to overexpression of miR-23a and this could be one of the factors for drug-induced effects in cancer cells [

3]. A role of miR-627 is suggested by inhibiting the intracellular drug metabolism of Irinotecan, inducing a better responsiveness [

287]. Recent findings have suggested that miR-9-3p and miR-9-5p could contribute to etoposide resistance in cancer cells by influencing the reduction of Topo II protein level [

288].

Another study investigated the role of miR-21-5p in drug resistance in colorectal cancer cells. High levels of miR-21-5p was found to be associated with poor prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Overexpressing miR-21-5p in DLD-1 colorectal cancer cells led to drug resistance against topoisomerase inhibitors. The resistance was attributed to reduced apoptosis and increased autophagy without affecting topoisomerase expression or activity. Bioinformatics analysis revealed genetic reprogramming and downregulation of proteasome pathway genes in response to miR-21-5p overexpression. These findings have provided valuable insights into the development of drug resistance in colorectal cancer and suggest potential clinical strategies to overcome it [

66], [

287,

288].

14.2. EMT and Topo-active drugs

The elevation of epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) during Topo active drug resistance have been observed as one of the many changes within the tumor microenvironment. Limited studies are available to decipher the molecular basis of EMT and topo-active drug resistance. A finding suggested that EMT genes ZEB1 and CDH2 are upregulated in colorectal cancer cells following development of resistance to doxorubicin [

289]. The role of EMT as an enhancer of doxorubicin-mediated drug resistance is indicated via mediators such as ZEB proteins, microRNAs, Twist1, and TGF-β. Combinational uses of small molecule inhibitors of EMT and topo-active drugs have been proposed as one of the newer approaches for anticancer therapy [

290]. Topoisomerase II is demonstrated to induce EMT by using a TCF (T Cell Factor) transcription inducer. To achieve combinatorial avenues, inhibitors of TCF with topo-active drugs have been explored as a new class of therapies [

291,

292]. Maximum tolerable dosing (MTD) of topotecan is suggested to cause enhanced EMT while extended exposure of topotecan induces increased long-term drug sensitivity by decreasing malignant heterogeneity and preventing EMT [

293].

The role of epidermal growth factor receptors in topo-active drugs in cancer drug resistance have also been examined. A study indicated that epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR TKIs) like gefitinib and erlotinib combined with topoisomerase I inhibitors could be a promising treatment option for resistant NSCLC [

294]. Osteoprotegerin (OPG) has been reported to be associated with various cancer types, including bladder carcinoma, gastric carcinoma, prostate cancer, multiple myeloma, and breast cancer [

295]. High levels of OPG secretion were associated with metastasis and drug resistance in aggressive breast cancer treated with topo-active drugs.

The complicated metabolism of irinotecan makes it a potential target for drug interactions, and it was shown that UGT 1A1 mediated glucuronidation of SN-38 to SN-38G resulted from the elevated levels of UGT at both the protein and mRNA levels. Overexpression of UGT at both the mRNA and protein levels can be responsible for SN-38 resistance in a human lung cancer cell line [

51]. Studies have indicated that irinotecan therapy activates nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB), a ubiquitous transcription factor with the elevation of TNF-alpha and oncogenic Ras and emergence of drug resistance in cancer cells [

296].

The modulation of Topo I expression via the ubiquitin/26S proteasome pathway is suggested for the topo I-drug resistance. Data have indicated that formation of ·NO/·NO-derived species in cancer cells can induce the reduction in the level of Topo I via the ubiquitin/26S proteasome pathway [

64]. Exploring combinatorial approaches by combining proteasome inhibitors such as MG132 and lactacystin along with Topo active drugs including SN-38 have been reported to potentiate anticancer effects in cancer cells [

261], [

297,

298].

15. Conclusion and Future Developments

As we have gained a better understanding of mechanisms involved in formation and progression of cancers, significant progress has been achieved in the treatment of human cancers in the clinic. Unfortunately, chemotherapy resistance has also remained a challenge both in the treatment of patients and in the discovery of novel cancer drugs. One main aim of this review is to describe the various mechanisms of resistance to topoisomerase-based therapies and as we also believe that with understanding of these mechanisms better topoisomerase drugs can be discovered for future treatment of patients in the clinic. The development and synthesis of novel topoisomerase active compounds may lead to the discovery of new topoisomerase inhibitors with improved efficacy and safety profiles. Recent advances in understanding of tumor transformation and progression mechanisms and their regulation by proteins have led to a new era in drug formulation and clinical evaluation. Research on developing drugs that target specific types of topoisomerases could show promising results by reducing off-target effects with better treatment accuracy and reduced side effects. Also, the use of natural compounds from various organisms or plants needs to be explored for their unique structure and mechanism of action as novel topoisomerase inhibitors.

Recent advances in the drug delivery system (s) offer also exciting opportunities for packaging active topo-active drugs. Significant progress has been made in the field of encapsulation of chemotherapeutics and FDA has now approved various liposomes for therapy which should be tried with topo-active drugs. Another area that needs to be explored is utilizing antibody-drug conjugate delivery systems as it is highly specific for a precise delivery of drugs to tumors. While exosomes for delivery of chemotherapeutics is not well studied, recent advancement would suggest chemotherapeutics drugs like doxorubicin and SN-38 can also be packaged into exosomes for the treatment of human cancers. The discovery of nanoparticles plays a key role in improved drug formulation by enhancing drug delivery, solubility, and stability of the drug. More research on nanoparticle-based cancer drugs helps in developing sustained release and targeted delivery of the topo-drug which can eventually reduce the side effects of these drugs and can also prevent development of drug resistance.

The implementation of combinatorial therapies by combining a topoisomerase inhibitor with another type of drug in a single formulation can improve efficacy and simplify treatment regimens. It is necessary for researchers and clinicians to develop combination therapies or newer drugs that target multiple mechanisms simultaneously or employ strategies to reverse or prevent resistance. Although combinatorial therapy is complex, it is recommended to conduct more investigation on different combinations of drugs for better treatment and to overcome drug resistance in the clinic. Our recent research has shown that nitric oxide generating drugs e.g., J-SK or NCX4040 are highly effective in inhibiting functions of ABC transporters, resulting in the sensitization doxorubicin and topotecan in ABC transporter-expressing cells [

299,

300]. We believe that this needs to be further explored in a clinical setting as these combinations may be highly beneficial for the treatment of patients overexpressing MDR phenotype. Another active area of research is use of combinations of ferroptosis inducers, e.g., Erastin or RSL3, with anticancer drugs to overcome resistance. We have found that such combinations of ferroptosis inducers erastin with topo-active drug doxorubicin, results in overcoming drug resistance in a Pgp-overexpressing tumor cells (Sinha et al unpublished observations).

Treatments have become precise, personalized, and targeted toward each patient, and have been widely adopted in clinical practice due to the development of techniques like next-generation sequencing (NGS), comparative proteomics, structural biology, and computational methods. As genetic mutations, chromosomal abnormalities, epigenetic alterations, and extracellular vesicles (EV) play significant roles in the growth of tumours, these also represent a vast untapped resource of knowledge with enormous potential as cancer biomarkers in precision medicine. By sequencing a patient’s genetic information, it is possible to identify any abnormal gene expressions and genetic aberrations, leading to rapid diagnosis and targeted therapy.

As precision medicine has become essential, it also has its disadvantages such as the cost of the test, reachability among the population, and ethical concerns. Therefore, for a successful precision therapy, it is necessary to obtain additional knowledge on comparative genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomics for better understanding. Furthermore, further research should be conducted on a large population model to stop adverse events, eliminate unnecessary and inefficient treatments, and to deliver more efficient targeted medicines.

In cancer, understanding the resistance mechanisms of existing drugs is crucial. Currently, the problem of multi-drug resistance in cancer is treated by implementing various strategies like combinational therapy, synthetic analogues, precision medicine, and immunotherapy. Eventually these cancer cells become resistant against new drugs by undergoing genetic alteration, epigenetic changes, and other strategies. Therefore, it is essential to study the resistant mechanisms of cancer for the development of new treatments to overcome or bypass these multi-drug-resistant cancer cells.

The development of clinical care for many cancers with poor prognoses has been made possible by the promising emergence and success of cancer immunotherapy. Despite significant advancements in immunotherapies, there still are various difficulties, e.g., low response rates, an inability to anticipate clinical effectiveness, and possible adverse effects such as cytokine storm or autoimmune responses. Therefore, it is recommended to find newer immunotherapeutic agents and immunotherapy technologies for improved treatment with a quick onset of action, reduced toxicity, and increased efficiency.

Although, cancer stem cell targeting is an interesting area of research in cancer therapy, it is essential to address the root cause of cancer for the treatment of cancer stem cells as they survive much longer than normal cells and accumulate genetic mutations. Implementation of different strategies like epigenetic therapies, personalized medicine, and combinational therapies are recommended to be further researched for the improvement of the treatment. Development of novel CSC targeting inhibitors can become a potential drug that disrupts self-renewal, and differentiation of cancer stem cells with fewer toxicity and more accuracy.

In conclusion, increased understanding of the mechanisms underlying cancer drug resistance suggests that an integrated approach to cancer therapy is needed for targeting multiple signalling pathways. Recent utilization of molecular targeting agents to effect multiple signalling pathways remains an important approach in cancer treatment, however, use of these targeted therapies is not without limitations. Further research is needed to identify approaches to repurpose drugs to optimize therapy for different human cancers.

Figure 5.

A summarized illustration of various molecular mechanisms and the scope of potential combinatorial avenues that can alleviate the Topo-active drug resistance in cancer cells.

Figure 5.

A summarized illustration of various molecular mechanisms and the scope of potential combinatorial avenues that can alleviate the Topo-active drug resistance in cancer cells.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization Birandra K. Sinha, Writing—original draft preparation, NKS, AB, GS, KK, PVS, MB, AH, Editing and writing, BKS.

Funding

This research was supported by the intramural research program (grant numbers ZIA E505013922) of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, NIH. Statements contained herein do not necessarily represent the statements, opinions, or conclusions of NIEHS, NIH, or the US Government.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no actual or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Chhikara BS, Parang K. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: The Trends Projection Analysis. Chem Biol Lett. 2023;10(1):451.

- Morgan E, Arnold M, Gini A, Lorenzoni V, Cabasag CJ, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Murphy N, Bray F. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut. 2023;72(2):338-344. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Zhang H, Chen X. Drug resistance and combating drug resistance in cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2019;2(2):141-160. [CrossRef]

- Emran TB, Shahriar A, Mahmud AR, Rahman T, Abir MH, Siddiquee MF, Ahmed H, Rahman N, Nainu F, Wahyudin E, Mitra S, Dhama K, Habiballah MM, Haque S, Islam A, Hassan MM. Multidrug Resistance in Cancer: Understanding Molecular Mechanisms, Immunoprevention and Therapeutic Approaches. Front Oncol. 2022;12:891652. [CrossRef]

- Vaidya FU, Sufiyan Chhipa A, Mishra V, Gupta VK, Rawat SG, Kumar A, Pathak C. Molecular and cellular paradigms of multidrug resistance in cancer. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 2022;5(12):e1291. [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou M, Pavlopoulou A, Georgakilas AG, Kyrodimos E. The challenge of drug resistance in cancer treatment: a current overview. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2018;35(4):309-318. [CrossRef]

- Ramos A, Sadeghi S, Tabatabaeian H. Battling Chemoresistance in Cancer: Root Causes and Strategies to Uproot Them. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(17):9451. [CrossRef]

- You F, Gao C. Topoisomerase Inhibitors and Targeted Delivery in Cancer Therapy. Curr Top Med Chem. 2019;19(9):713-729. [CrossRef]

- Nitiss JL, Kiianitsa K, Sun Y, Nitiss KC, Maizels N. Topoisomerase Assays. Curr Protoc. 2021;1(10):e250. [CrossRef]

- Singh S, Pandey VP, Yadav K, Yadav A, Dwivedi UN. Natural Products as Anti-Cancerous Therapeutic Molecules Targeted towards Topoisomerases. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2020;21(11):1103-1142. [CrossRef]

- Jang JY, Kim D, Kim ND. Recent Developments in Combination Chemotherapy for Colorectal and Breast Cancers with Topoisomerase Inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(9):8457. [CrossRef]

- Madkour MM, Ramadan WS, Saleh E, El-Awady R. Epigenetic modulations in cancer: predictive biomarkers and potential targets for overcoming the resistance to topoisomerase I inhibitors. Ann Med. 2023;55(1):2203946. [CrossRef]

- Sun YL, Patel A, Kumar P, Chen ZS. Role of ABC transporters in cancer chemotherapy. Chin J Cancer. 2012;31(2):51-7. [CrossRef]

- Wtorek K, Długosz A, Janecka A. Drug resistance in topoisomerase-targeting therapy. Postępy Higieny i Medycyny Doświadczalnej. 2018;72:1073-1083. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Qu L, Meng L, Shou C. Topoisomerase inhibitors promote cancer cell motility via ROS-mediated activation of JAK2-STAT1-CXCL1 pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):370. [CrossRef]

- Nwabufo, CK. Relevance of ABC Transporters in Drug Development. Curr Drug Metab. 2022;23(6):434-446. [CrossRef]

- Simůnek T, Stérba M, Popelová O, Adamcová M, Hrdina R, Gersl V. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity: overview of studies examining the roles of oxidative stress and free cellular iron. Pharmacol Rep. 2009;61(1):154-71. [CrossRef]

- Cai F, Luis MAF, Lin X, Wang M, Cai L, Cen C, Biskup E. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in the chemotherapy treatment of breast cancer: Preventive strategies and treatment. Mol Clin Oncol. 2019;11(1):15-23. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy L, Sandhu JK, Harper ME, Cuperlovic-Culf M. Role of Glutathione in Cancer: From Mechanisms to Therapies. Biomolecules. 2020;10(10):1429. [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, RV. GlyNAC Supplementation Improves Glutathione Deficiency, Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Inflammation, Aging Hallmarks, Metabolic Defects, Muscle Strength, Cognitive Decline, and Body Composition: Implications for Healthy Aging. J Nutr. 2021;151(12):3606-3616. [CrossRef]

- Carrasco R, Castillo RL, Gormaz JG, Carrillo M, Thavendiranathan P. Role of Oxidative Stress in the Mechanisms of Anthracycline-Induced Cardiotoxicity: Effects of Preventive Strategies. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021:8863789. [CrossRef]

- Hickman JA, Potten CS, Merritt AJ, Fisher TC. Apoptosis and cancer chemotherapy. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1994;345(1313):319-25. [CrossRef]

- Dexheimer TS, Pommier Y. DNA cleavage assay for the identification of topoisomerase I inhibitors. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(11):1736-50. [CrossRef]

- Gokduman, K. Strategies Targeting DNA Topoisomerase I in Cancer Chemotherapy: Camptothecins, Nanocarriers for Camptothecins, Organic Non-Camptothecin Compounds and Metal Complexes. Curr Drug Targets. 2016;17(16):1928-1939. [CrossRef]

- Jurkovicova D, Neophytou CM, Gašparović AČ, Gonçalves AC. DNA Damage Response in Cancer Therapy and Resistance: Challenges and Opportunities. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(23):14672. [CrossRef]

- Sharma P, Hu-Lieskovan S, Wargo JA, Ribas A. Primary, Adaptive, and Acquired Resistance to Cancer Immunotherapy. Cell. 2017;168(4):707-723. [CrossRef]

- Jackson CM, Choi J, Lim M. Mechanisms of immunotherapy resistance: lessons from glioblastoma. Nat Immunol. 2019;20(9):1100-1109. [CrossRef]