Submitted:

15 December 2023

Posted:

18 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methods and Software

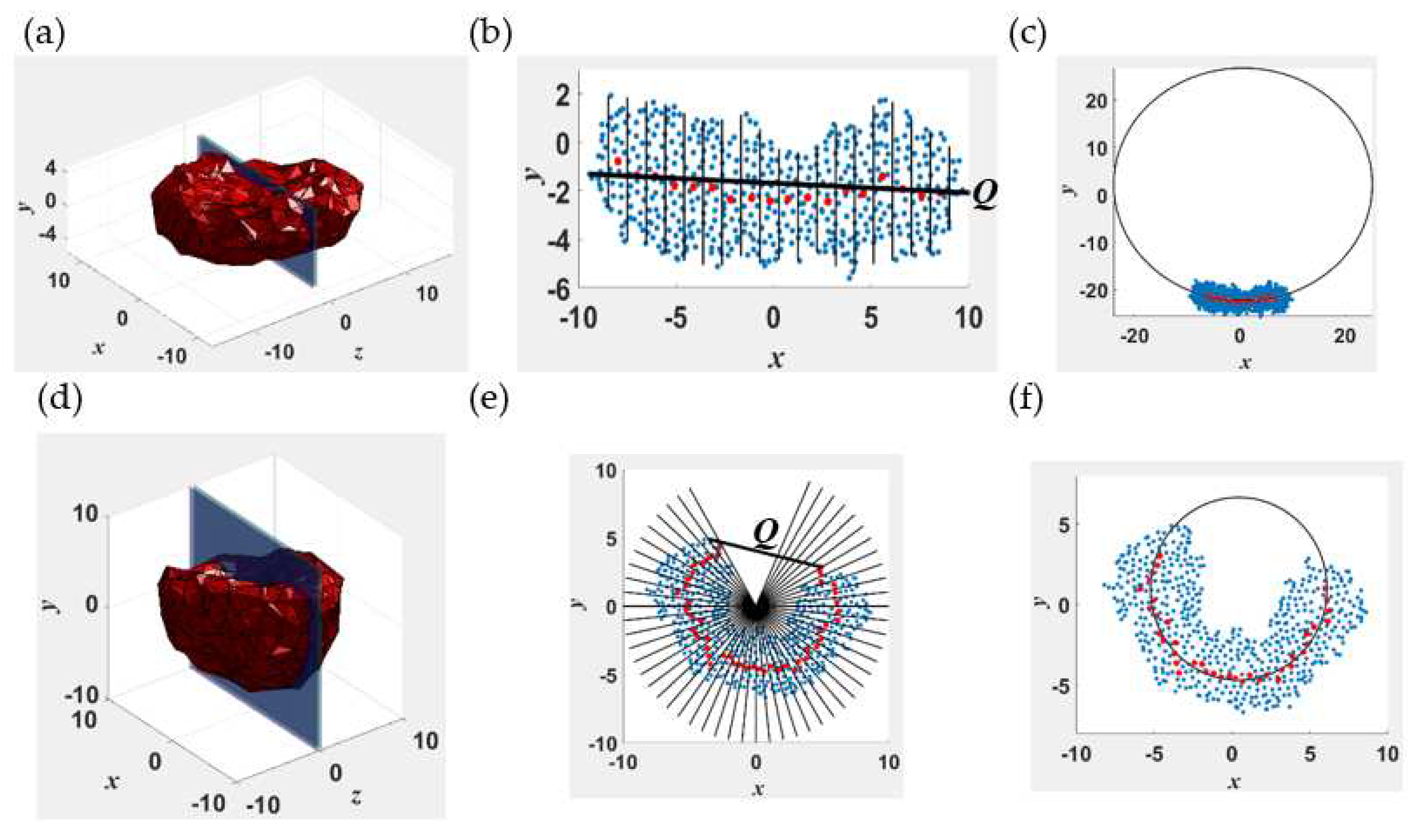

2.2. Data Analytics

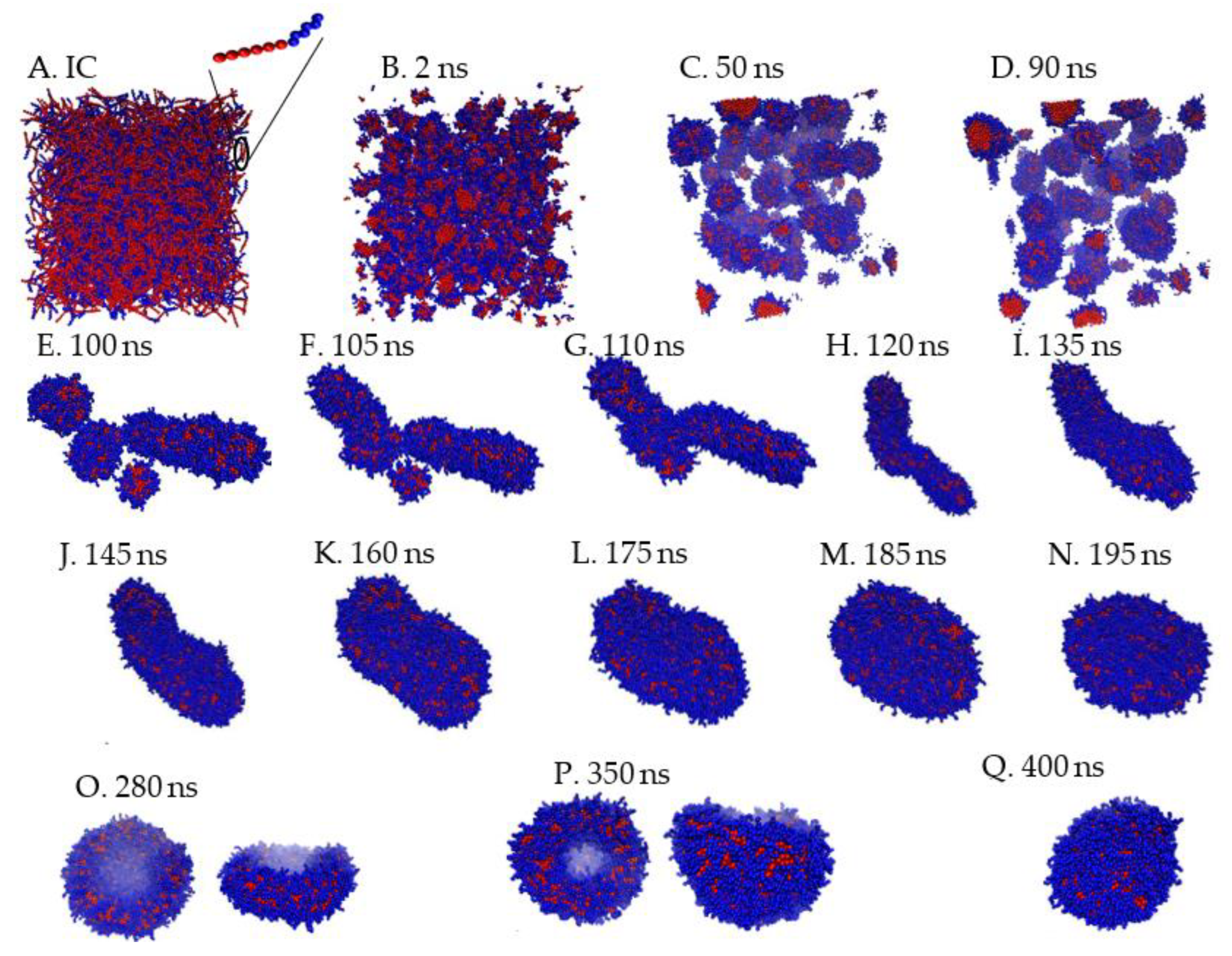

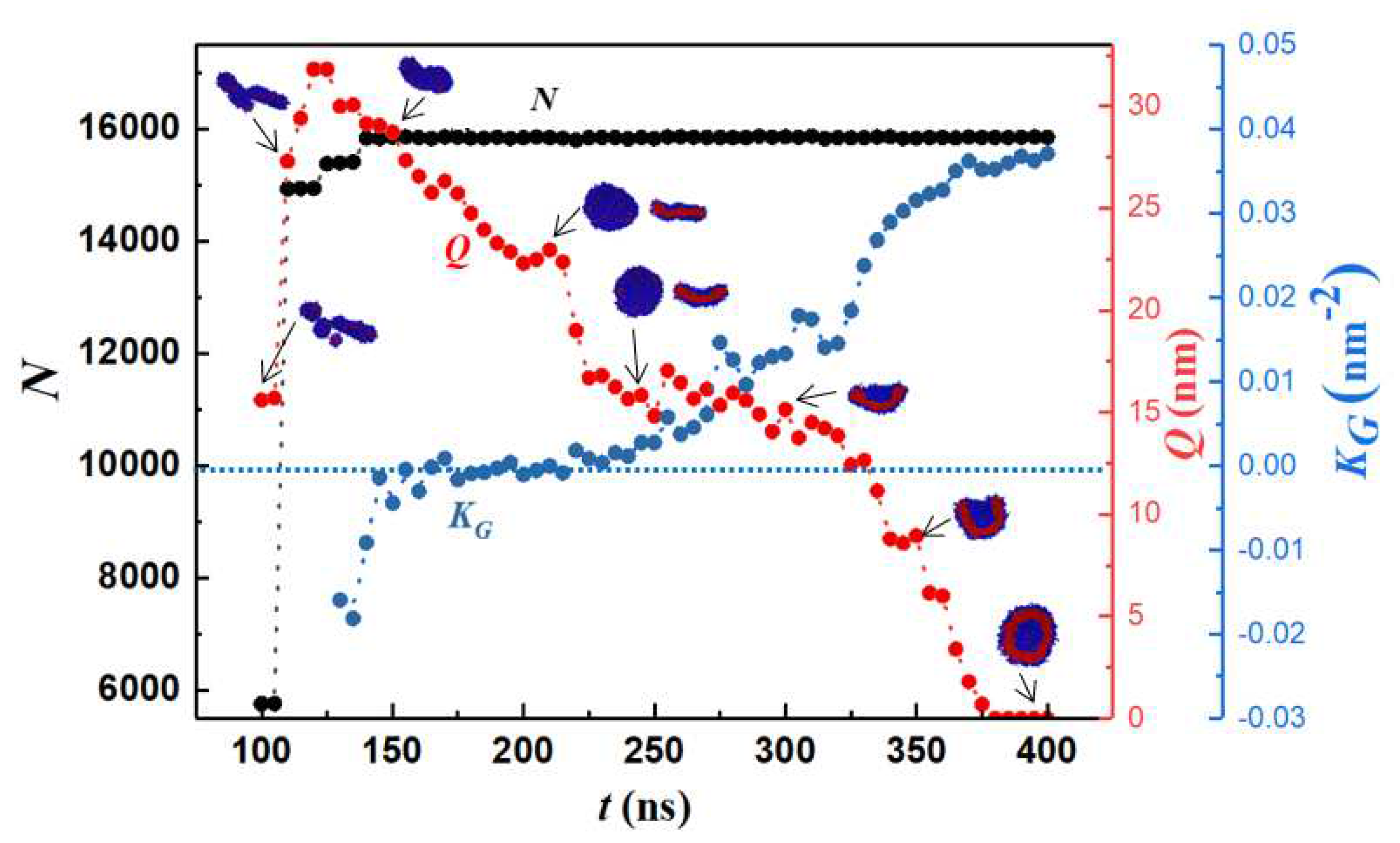

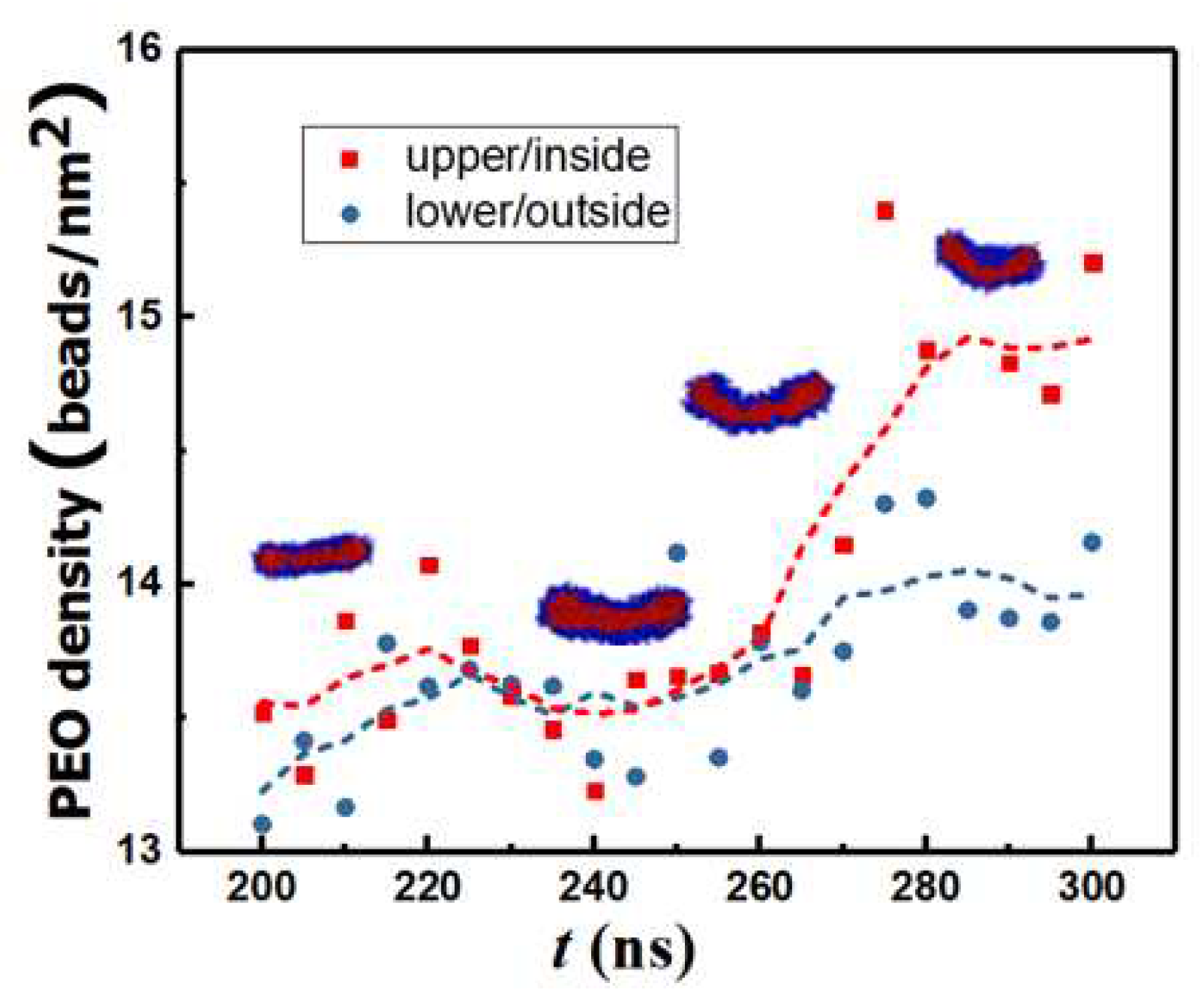

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bleul, R.; Thiermann, R.; Maskos, M. Techniques to Control Polymersome Size. Macromolecules 2015, 48 (20), 7396–7409. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Ramezani, M.; Abnous, K.; Alibolandi, M. Biocompatible Polymersomes-Based Cancer Theranostics: Towards Multifunctional Nanomedicine. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2017, 519 (1-2), 287–303. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-ying; Zhang, P.-ying. Polymersomes in Nanomedicine - A Review. Current Nanoscience 2017, 13 (2), 124–129. [CrossRef]

- Discher, D. E.; Ortiz, V.; Srinivas, G.; Klein, M. L.; Kim, Y.; Christian, D.; Cai, S.; Photos, P.; Ahmed, F. Emerging Applications of Polymersomes In Delivery: From Molecular Dynamics to Shrinkage of Tumors. Progress in Polymer Science 2007, 32 (8-9), 838–857. [CrossRef]

- Burkett, S. L.; Davis, M. E. Mechanism of Structure Direction In the Synthesis of Pure-Silica Zeolites. 2. Hydrophobic Hydration and Structural Specificity. Chemistry of Materials 1995, 7 (8), 1453–1463. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wei, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhao, D. Large-Pore Ordered Mesoporous Materials Templated From Non-Pluronic Amphiphilic Block Copolymers. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42 (9), 4054–4070. [CrossRef]

- van Hest, J. C.; Delnoye, D. A.; Baars, M. W.; van Genderen, M. H.; Meijer, E. W. Polystyrene-Dendrimer Amphiphilic Block Copolymers With a Generation-Dependent Aggregation. Science 1995, 268 (5217), 1592–1595. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Eisenberg, A. Multiple Morphologies of “Crew-Cut” Aggregates of Polystyrene-b-Poly(Acrylic Acid) Block Copolymers. Science 1995, 268 (5218), 1728–1731. [CrossRef]

- Discher, B. M.; Won, Y.-Y.; Ege, D. S.; Lee, J. C.-M.; Bates, F. S.; Discher, D. E.; Hammer, D. A. Polymersomes: Tough Vesicles Made From Diblock Copolymers. Science 1999, 284 (5417), 1143–1146. [CrossRef]

- Mai, Y.; Eisenberg, A. Self-assembly of Block Copolymers. Chemical Society Reviews 2012, 41 (18), 5969. [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Bates, F. S. On the Origins of Morphological Complexity in Block Copolymer Surfactants. Science 2003, 300 (5618), 460–464. [CrossRef]

- Won, Y.-Y.; Brannan, A. K.; Davis, H. T.; Bates, F. S. Cryogenic Transmission Electron Microscopy (Cryo-Tem) of Micelles and Vesicles Formed in Water by Poly(Ethylene Oxide)-Based Block Copolymers. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2002, 106 (13), 3354–3364. [CrossRef]

- Israelachvili, J. N. Intermolecular and surface forces; Acad. Press, 2011.

- Karayianni, M.; Pispas, S. Block Copolymer Solution Self-Assembly: Recent Advances, Emerging Trends, and Applications. Journal of Polymer Science 2021, 59 (17), 1874–1898. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Byrne, B.; Welsh, J. E.; F. Palmer, A. Self-Assembled Poly(Butadiene)-b-Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Polymersomes As Paclitaxel Carriers. Biotechnol Prog. 2007, 23(1), 278–285. [CrossRef]

- Christine Allen, Adi Eisenberg, Jas, C. A.; Maysinger, D.; Mrsic, J.; Eisenberg, A. PCL-b-PEO Micelles As a Delivery Vehicle for Fk506: Assessment of a Functional Recovery of Crushed Peripheral Nerve. Drug Delivery 2000, 7 (3), 139–145. [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.; Yu, Y.; Maysinger, D.; Eisenberg, A. Polycaprolactone-b-Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Block Copolymer Micelles As a Novel Drug Delivery Vehicle For Neurotrophic Agents Fk506 and l-685,818. Bioconjugate Chemistry 1998, 9 (5), 564–572. [CrossRef]

- Boucher-Jacobs, C.; Rabnawaz, M.; Katz, J. S.; Even, R.; Guironnet, D. Encapsulation of catalyst in block copolymer micelles for the polymerization of ethylene in aqueous medium. Nature Communications 2018, 9 (1). [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, F.; Ceglie, A.; De Leonardis, A.; Lopez, F. Polymer Capsules for Enzymatic Catalysis in Confined Environments. Catalysts 2018, 9 (1), 1. [CrossRef]

- Peters, R. J.; Marguet, M.; Marais, S.; Fraaije, M. W.; van Hest, J. C.; Lecommandoux, S. Cascade Reactions in Multicompartmentalized Polymersomes. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2013, 53 (1), 146–150. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D. A.; Nolte, R. J.; van Hest, J. C. Autonomous Movement of Platinum-Loaded Stomatocytes. Nature Chemistry 2012, 4 (4), 268–274. [CrossRef]

- Marguet, M.; Bonduelle, C.; Lecommandoux, S. Multicompartmentalized Polymeric Systems: Towards Biomimetic Cellular Structure and Function. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42 (2), 512–529. [CrossRef]

- Che, H.; van Hest, J. C. Stimuli-Responsive Polymersomes and Nanoreactors. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2016, 4 (27), 4632–4647. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, M. L.; Boyd, M. A.; Kamat, N. P. Diblock Copolymers Enhance Folding of a Mechanosensitive Membrane Protein During Cell-free Expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116 (10), 4031–4036. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cooksey, T. J.; Kidd, B. E.; Robertson, M. L.; Madsen, L. A. Mapping Coexistence Phase Diagrams of Block Copolymer Micelles and Free Unimer Chains. Macromolecules 2018, 51 (20), 8127–8135. [CrossRef]

- Holder, S. W.; Grant, S. C.; Mohammadigoushki, H. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Diffusometry of Linear and Branched Wormlike Micelles. Langmuir 2021, 37 (12), 3585–3596. [CrossRef]

- Israelachvili, J. N.; Mitchell, D. J.; Ninham, B. W. Theory of Self-Assembly of Lipid Bilayers and Vesicles. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1977, 470 (2), 185–201. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Shen, H.; Eisenberg, A. Kinetics and Mechanism of the Rod-to-Vesicle Transition of Block Copolymer Aggregates in Dilute Solution. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 1999, 103 (44), 9488–9497. [CrossRef]

- Antonietti, M.; Förster, S. Vesicles and liposomes: A Self-Assembly Principle Beyond Lipids. Advanced Materials 2003, 15 (16), 1323–1333. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Sureshkumar, R. Morphological Diversity in Diblock Copolymer Solutions: A Molecular Dynamics Study. Colloids and Interfaces 2023, 7 (2), 40. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Quinn, D.; Sadovsky, Y.; Suresh, S.; Hsia, K. J. Formation and Size Distribution of Self-Assembled Vesicles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114 (11), 2910–2915. [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, G.; Discher, D. E.; Klein, M. L. Self-Assembly and Properties of Diblock Copolymers By Coarse-Grain Molecular Dynamics. Nature Materials 2004, 3 (9), 638–644. [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, G.; Shelley, J. C.; Nielsen, S. O.; Discher, D. E.; Klein, M. L. Simulation of Diblock Copolymer Self-Assembly, Using a Coarse-Grain Model. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2004, 108 (24), 8153–8160. [CrossRef]

- Lipowsky, R. The Conformation of Membranes. Nature 1991, 349 (6309), 475–481. [CrossRef]

- Fromherz, P.; Röcker, C.; Rüppel, D. From discoid micelles to spherical vesicles. the concept of edge activity. Faraday Discuss. Chem. Soc. 1986, 81, 39–48. [CrossRef]

- Noguchi, H.; Gompper, G. Dynamics of vesicle self-assembly and dissolution. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2006, 125 (16), 164908. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Huang, C.; Li, J.; Lykotrafitis, G.; Zhang, S. One-particle-thick, solvent-free, coarse-grained model for biological and biomimetic fluid membranes. Physical Review E 2010, 82 (1). [CrossRef]

- Canham, P. B. The Minimum Energy of Bending as a Possible Explanation of the Biconcave Shape of the Human Red Blood Cell. Journal of Theoretical Biology 1970, 26 (1), 61–81. [CrossRef]

- Helfrich, W. Elastic Properties of Lipid Bilayers: Theory and Possible Experiments. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C 1973, 28 (11–12), 693–703. [CrossRef]

- Faucon, J. F.; Mitov, M. D.; Méléard, P.; Bivas, I.; Bothorel, P. Bending Elasticity and Thermal Fluctuations of Lipid Membranes-Theoretical and Experimental Requirements. Journal de Physique 1989, 50 (17), 2389–2414. [CrossRef]

- Evans, Evan.; Needham, David. Physical Properties of Surfactant Bilayer Membranes: Thermal Transitions, Elasticity, Rigidity, Cohesion and Colloidal Interactions. The Journal of Physical Chemistry 1987, 91 (16), 4219–4228. [CrossRef]

- Cooke, I. R.; Deserno, M. Coupling Between Lipid Shape and Membrane Curvature. Biophysical Journal 2006, 91 (2), 487–495. [CrossRef]

- Fogel, A. L.; Ravichandran, A.; Mani, S.; Upadhyay, B.; Khare, R.; Morgan, S. E. Water structure and mobility in acrylamide copolymer glycohydrogels with galactose and Siloxane Pendant Groups. Journal of Polymer Science Part B: Polymer Physics 2019, 57 (10), 584–597. [CrossRef]

- Walter, A.; Vinson, P. K.; Kaplun, A.; Talmon, Y. Intermediate structures in the cholate-phosphatidylcholine vesicle-micelle transition. Biophysical Journal 1991, 60 (6), 1315–1325. [CrossRef]

- Vinson, P. K.; Talmon, Y.; Walter, A. Vesicle-micelle transition of phosphatidylcholine and octyl glucoside elucidated by cryo-transmission electron microscopy. Biophysical Journal 1989, 56 (4), 669–681. [CrossRef]

- Davies, T. S.; Ketner, A. M.; Raghavan, S. R. Self-assembly of surfactant vesicles that transform into viscoelastic wormlike micelles upon heating. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2006, 128 (20), 6669–6675. [CrossRef]

- Markvoort, A. J.; van Santen, R. A.; Hilbers, P. A. Vesicle shapes from molecular dynamics simulations. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2006, 110 (45), 22780–22785. [CrossRef]

- Markvoort, A. J.; Pieterse, K.; Steijaert, M. N.; Spijker, P.; Hilbers, P. A. The Bilayer−Vesicle Transition is Entropy Driven. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2005, 109 (47), 22649–22654. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Schmid, F. Spontaneous formation of complex micelles from a homogeneous solution. Physical Review Letters 2008, 100 (13). [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Schmid, F. Dynamics of spontaneous vesicle formation in dilute solutions of Amphiphilic Diblock Copolymers. Macromolecules 2006, 39 (7), 2654–2662. [CrossRef]

- Sevink, G. J.; Zvelindovsky, A. V. Self-assembly of complex vesicles. Macromolecules 2005, 38 (17), 7502–7513. [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Khomami, B. Self-Assembly of Linear Diblock Copolymers in Selective Solvents: From Single Micelles To Particles With Tri-Continuous Inner Structures. Soft Matter 2020, 16 (26), 6056–6062. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dormidontova, E. E. Equilibrium Chain Exchange Kinetics In Block Copolymer Micelle Solutions By Dissipative Particle Dynamics Simulations. Soft Matter 2011, 7 (9), 4179. [CrossRef]

- Javan Nikkhah, S.; Turunen, E.; Lepo, A.; Ala-Nissila, T.; Sammalkorpi, M. Multicore assemblies from three-component linear homo-copolymer systems: A coarse-grained modeling study. Polymers 2021, 13 (13), 2193. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, V.; Nielsen, S. O.; Discher, D. E.; Klein, M. L.; Lipowsky, R.; Shillcock, J. Dissipative particle dynamics simulations of polymersomes. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2005, 109 (37), 17708–17714. [CrossRef]

- Shillcock, J. C. Spontaneous vesicle self-assembly: A mesoscopic view of membrane dynamics. Langmuir 2012, 28 (1), 541–547. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Liu, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, R.; Xie, D. Biomimetic membrane control of block copolymer vesicles with tunable wall thickness. Soft Matter 2013, 9 (8), 2434. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Bao, M. Micelle-vesicle transitions in catanionic mixtures of SDS/DTAB induced by salt, temperature, and selective solvents: A dissipative particle dynamics simulation study. Colloid and Polymer Science 2014, 292 (9), 2349–2360. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, B.; Jiang, J. Ph-sensitive vesicles formed by amphiphilic grafted copolymers with tunable membrane permeability for drug loading/release: A multiscale simulation study. Macromolecules 2016, 49 (16), 6084–6094. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Lu, T.; Guo, H. Dissipative particle dynamic simulation study of lipid membrane. Frontiers of Chemistry in China 2010, 5 (3), 288–298. [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Yan, N.; Jin, J.; Jiang, W. Disassembly of amphiphilic AB block copolymer vesicles in selective solvents: A molecular dynamics simulation study. Macromolecules 2023, 56 (6), 2560–2567. [CrossRef]

- Lyubimov, I.; Wessels, M. G.; Jayaraman, A. Molecular dynamics simulation and prism theory study of assembly in solutions of amphiphilic bottlebrush block copolymers. Macromolecules 2018, 51 (19), 7586–7599. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, K.; Shinoda, W.; Loverde, S. M. Molecular Simulation of the Shape Deformation of a Polymersome. Soft Matter 2020, 16 (13), 3234–3244. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Pei, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, P.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J. Coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulation study on spherical and tube-like vesicles formed by amphiphilic copolymers. Journal of Polymer Science Part B: Polymer Physics 2017, 55 (16), 1220–1226. [CrossRef]

- Marrink, S. J.; Mark, A. E. Molecular dynamics simulation of the formation, structure, and dynamics of small phospholipid vesicles. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2003, 125 (49), 15233–15242. [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Deng, M.; Kong, B.; Yang, X. Coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulation of ammonium surfactant self-assemblies: Micelles and vesicles. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2009, 113 (45), 15010–15016. [CrossRef]

- Sambasivam, A.; Dhakal, S.; Sureshkumar, R. Structure and Rheology of Self-Assembled Aqueous Suspensions Of Nanoparticles And Wormlike Micelles. Molecular Simulation 2017, 44 (6), 485–493. [CrossRef]

- Sambasivam, A.; Sangwai, A. V.; Sureshkumar, R. Self-Assembly of Nanoparticle–Surfactant Complexes With Rodlike Micelles: a Molecular Dynamics Study. Langmuir 2016, 32 (5), 1214–1219. [CrossRef]

- Sambasivam, A.; Sangwai, A. V.; Sureshkumar, R. Dynamics and Scission of Rodlike Cationic Surfactant Micelles In Shear Flow. Physical Review Letters 2015, 114 (15), 8302. [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, S.; Sureshkumar, R. Anomalous Diffusion and Stress Relaxation In Surfactant Micelles. Physical Review E 2017, 96 (1), 2605. [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, S.; Sureshkumar, R. Uniaxial Extension of Surfactant Micelles: Counterion Mediated Chain Stiffening and a Mechanism of Rupture by Flow-Induced Energy Redistribution. ACS Macro Letters 2015, 5 (1), 108–111. [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, S.; Sureshkumar, R. Topology, Length Scales, and Energetics of Surfactant Micelles. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2015, 143 (2), 024905. [CrossRef]

- Sangwai, A. V.; Sureshkumar, R. Binary Interactions and Salt-Induced Coalescence of Spherical Micelles of Cationic Surfactants From Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Langmuir 2011, 28 (2), 1127–1135. [CrossRef]

- Sangwai, A. V.; Sureshkumar, R. Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics Simulations of the Sphere to Rod Transition in Surfactant Micelles. Langmuir 2011, 27 (11), 6628–6638. [CrossRef]

- Marrink, S. J.; Risselada, H. J.; Yefimov, S.; Tieleman, D. P.; de Vries, A. H. The Martini Force Field: Coarse Grained Model For Biomolecular Simulations. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2007, 111 (27), 7812–7824. [CrossRef]

- Eisenhaber, F.; Lijnzaad, P.; Argos, P.; Sander, C.; Scharf, M. The double cubic lattice method: Efficient approaches to numerical integration of surface area and volume and to Dot surface contouring of Molecular Assemblies. Journal of Computational Chemistry 1995, 16 (3), 273–284. [CrossRef]

- Pratt, V. Direct least-squares fitting of algebraic surfaces. ACM SIGGRAPH Computer Graphics 1987, 21 (4), 145–152. [CrossRef]

- Park, S. Y.; Bera, A. K. Maximum Entropy Autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity model. Journal of Econometrics 2009, 150 (2), 219–230. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. Structure, Dynamics and Rheology of Polymer Solutions from Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics: Effects of Polymer Concentration, Solvent Quality and Geometric Confinement. Ph.D. Dissertation, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, 2015.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).