1. Introduction

Olive groves have been a prominent crop in the Mediterranean region for over 6500 years, holding significant sociocultural and economic importance [

1,

2]. With a global area of approximately 10 million hectares, over 90% of olive groves are concentrated in the Mediterranean Basin, [

3]. The expected olive oil production for 2021/2022 is 3 116 x 10

3 Mg, with Spain (38%), Italy (11%), Greece (11%), and Portugal (9%) being the largest producers [

3]. Notably, worldwide olive oil production has experienced significant growth in the past five years, with Portugal and Italy recording increases of 78% and 15%, respectively, while Spain and Greece witnessed declines of 6% and 18%, respectively [

3].

Traditionally, olive groves in the Mediterranean were rainfed and had low tree densities (50-100 trees per hectare) in marginal agricultural areas [

4,

5,

6]. These groves thrived in conditions less suitable for other crops, such as water scarcity [

7]. The productivity of rainfed olive groves was relatively low, yielding 500 to 600 kg of olives per hectare, and relied heavily on manual labor [

8]. However, since the 1980s, olive grove cultivation has undergone significant changes to enhance economic performance and address labor shortages. This shift involved adopting irrigation, mechanization (all the cultural operations, from plantation to harvest are mechanized), higher planting densities (1800 to 2200 trees per hectare), and the use of fertilizers and phytopharmaceuticals [

9,

10,

11,

12]. These changes led to substantially higher and more stable yields, reaching 12 000 to 14,000 kg of olives per hectare.

Nevertheless, this intensification of olive grove production has generated considerable controversy, with critics highlighting various concerns. One primary criticism revolves around the decrease in biodiversity due to the transformation of traditional rainfed groves into super-intensive ones [

13,

14,

15]. Additionally, the relatively high water consumption of new production systems, approximately 3000 m

3 per hectare, raises sustainability concerns in the face of increasing water scarcity due to the climate crisis [

10,

16].

The impact of these new production systems on soil properties is also a subject of debate [

9]. Potential impacts include increased soil erosion risk in sloped areas, compaction from machinery traffic, decreased soil organic matter content due to irrigation-induced mineralization, changes in soil pH through cations bases leaching and acidifying fertilizers, increased salinity from irrigation water and fertilizers, and surface and groundwater contamination from leaching of fertilizers and phytopharmaceuticals [

17,

18,

19,

20]. However, there are contrasting opinions regarding the impacts of super-intensive olive groves. In the case of rainfed areas converted to irrigated groves, the changes in soil physical, chemical, and biological characteristics are notable but primarily associated with the introduction of irrigation rather than a specific crop [

21,

22,

23]. When super-intensive olive groves replace other crops under irrigation, some argue that the negative effects may be less pronounced compared to alternative crops. Super-intensive olive groves generally use less water and fewer fertilizers than other irrigated crops, resulting in potentially lower impacts on soil properties such as pH, salinity, and organic matter content [

20,

24,

25,

26]

Given the ongoing expansion of super-intensive olive groves in the southern Iberian Peninsula and the lack of consensus among researchers regarding their impact on soil properties, our study aims to investigate the changes in the chemical composition of a Fluvisol soil (most representative of the region) under two different crop systems (super-intensive olive groves and rainfed olive orchards) over a decade. We will also compare the impacts of hedgerow olive orchards with other irrigated crops, such as maize, tomato, and cereals, on selected soil chemical properties.

By conducting this study, we aim to contribute to the understanding of the effects of super-intensive olive groves on soil chemistry and provide valuable insights for sustainable olive grove management practices in the context of evolving agricultural systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sampling

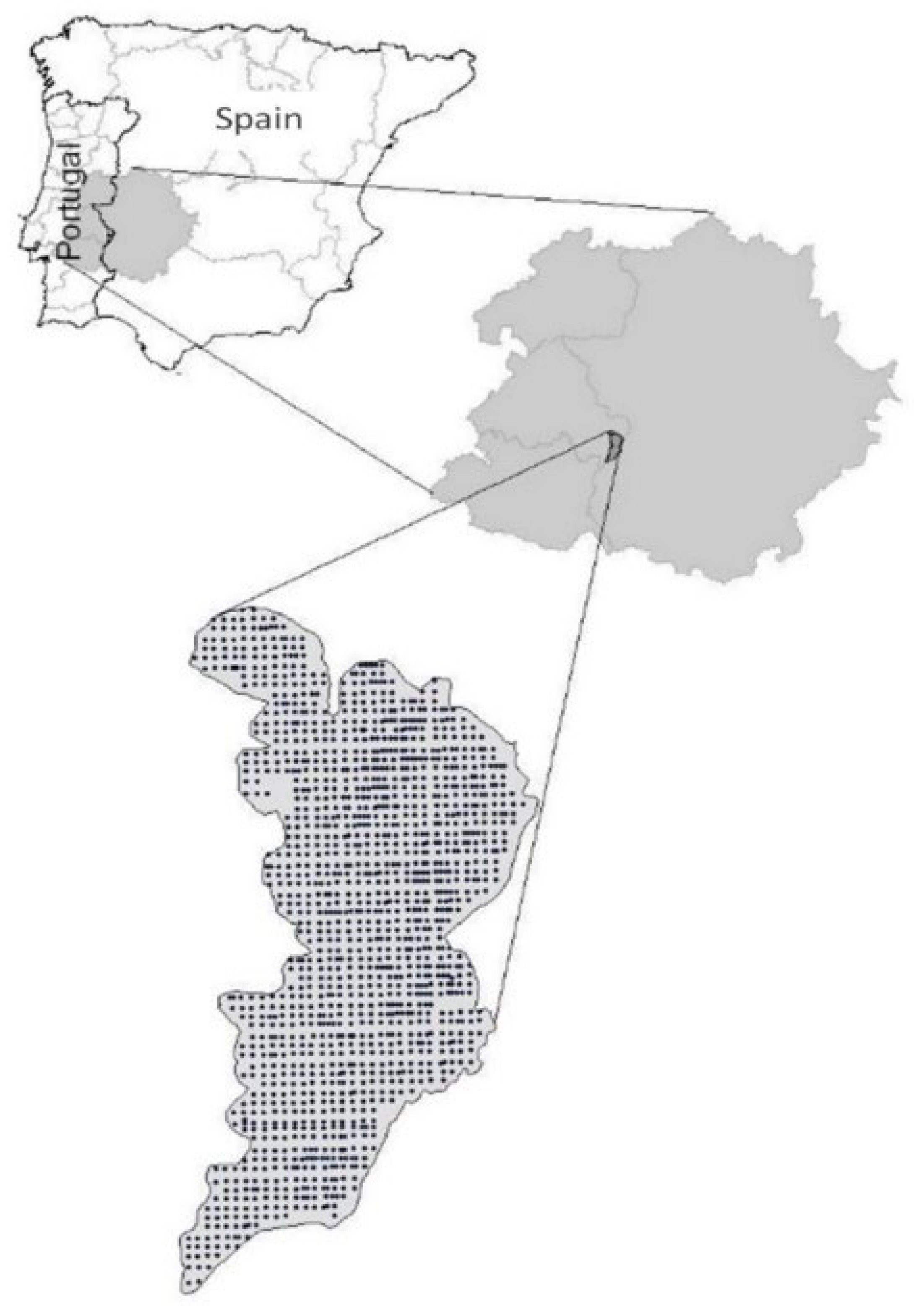

The region in which we developed our study is located in the Center-South of the Iberian Peninsula, in the Portuguese region called Alentejo, covering part of the Municipalities of Campo Maior and Elvas (

Figure 1). The study was carried out in the Caia Irrigation Perimeter, which has 7240 ha, and the agricultural areas surrounding the Irrigation Perimeter were also used in this study, totaling 15030 ha. The region's climate is characterized by hot, dry summers and mild winters with high rainfall (average annual rainfall of 457.4 mm and a mean annual evapotranspiration of roughly 813.2 mm – data in the 1991 – 2020 climate normal). The month with the highest temperature is August, with an average monthly maximum temperature of 34.9 °C and the coldest month is January, with an average monthly minimum temperature of 4.5 °C. According to Koppen, the region's climate classification is Csa and according to Thornthwait it is DB2db4, i.e. mesothermal semi-arid, with little or no excess water in the winter and very low thermal efficiency in the summer.

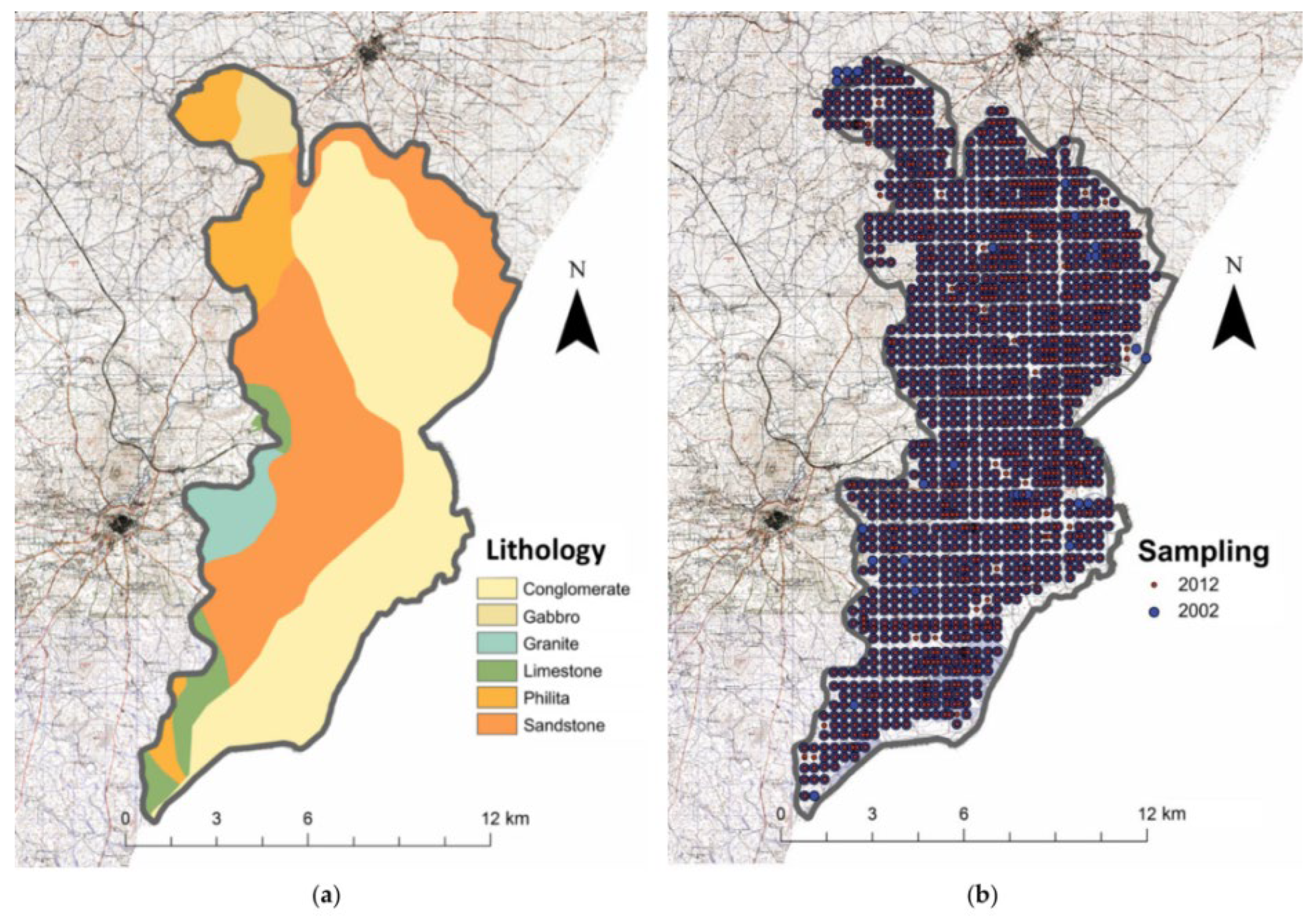

The region is geologically heterogeneous, consisting of Quaternary conglomerates, Paleogene sandstones, Neoproterozoic phyllites, Devonian gabbros, Carboniferous granites, and Cambrian limestones (

Figure 2). The soils of the study area, classified according to the World Base of Reference (WRB) of the FAO Soil Resource are mainly divided into 4 groups: Fluvisols, Luvissols, Calcisoils and Cambisols, and in this work, due to their greater representativeness, which allows us to carry out a more consolidated statistical analysis, we will only consider fluvisols.

Source: Telo da Gama et al., 2021 [

28]

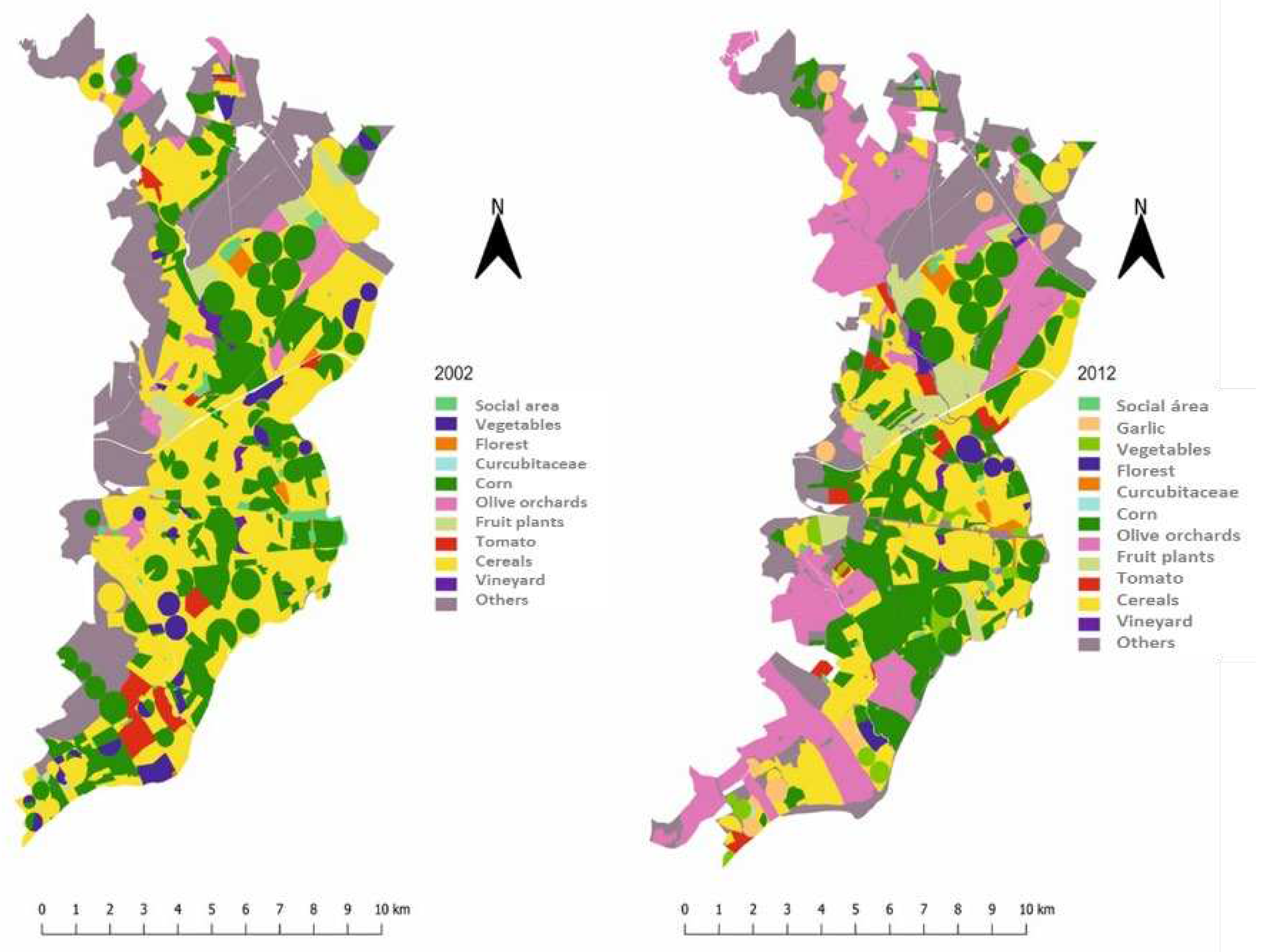

The most representative crops in the study area in 2012 are olive groves (Olea europaea L.) with 35%, corn (Zea mays L.) with 20%, tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) with 15% and garlic (Allium sativum L.) with 15% (

Figure 3). The olive groves considered in this study have more than 10 years after plantation. The irrigation water used in the Perimeter and adjacent areas is of good quality, classified according to the FAO classification as C1S1 and in the summertime as C1S2, which means water of low salinity and sodicity. The quality remained approximately unchanged over the decade under review.

In

Table 1 we present the average, min and max value for several water quality parameters measured monthly over the decade under analysis

2.2. Characterization of agronomic techniques

In

Table 2 we present a short characterization of the water and fertilizers amounts used in the main crops of the region, as well as their average yield

2.3. Soil data and analysis

A total of 631 and 526 topsoil samples were analyzed in 2002 and 2012 (each one of these samples came from the combination of 10 subsamples randomly collected in the area they represent), respectively, in the Fluvisols of the study area. Ten soil samples were collected using a stainless steel drill at a depth of 20 cm per sampling unit. Sampling sites were chosen to cover some of the existing variability in the sampling area. The soil samples were carefully mixed into one composite sample and sent to the laboratory after proper inventory and labeling. The samples were then air-dried in the laboratory and sieved through a 2 mm square mesh stainless steel sieve. After this phase, the corresponding analysis was performed. A brief description of the topsoil dominant properties of this reference soil group (RSG) for 2012 is presented in Telo da Gama et al. (2021) [

28]. For the 2002 edaphic description please refer to Telo da Gama et al. (2019) [

23].

2.4. Analytical methods

The pH (water) and Ec were determined in a 1:5 (w/v) solution. The PH by potentiometry (pH/ion MTROHM 692) and Ec with a conductivity meter (WPA CMD 8.500) [

29]. Soil organic matter was obtained using the method of wet oxidation with dichromate potassium, with measurement of excess dichromate by titration with ferrous sulfate. [

30].

The assimilable Ca and Mg values were extracted with a buffered ammonium acetate solution at pH 7.0, with the addition of 10% of lanthanum chloride solution, and their determination was carried out by atomic absorption spectrophotometry with flame atomization in an apparatus Perkin Elmer Analyzer A300 [

31]. Data for assimilable K, P and Na were extracted with a solution of ammonium lactate and acetic acid buffered at pH 3.65–3.75 and their determination was obtained by atomic absorption spectrophotometry with flame atomization on a Perkin Elmer Analyzer A300 apparatus. Exchange cations were extracted with ammonium acetate solution (1N) buffered to pH 7.0 and assayed by flame atomization atomic absorption spectrophotometry on a Perkin Elmer Analyzer A300 apparatus.

The Extractable metals were determined using the method described by USDA (1996) [

31], extraction with DTPA + CaCl

2 + triethanolamine and quantification by flame atomization atomic absorption spectrophotometry with a Perkin apparatus Elmer Analyzer A300.

2.5. Statistical analysis

To determine whether the sample data from 2002 and 2012 were normally distributed, statistical analyses were carried out using the software package SPSS (v.25). These analyses included tests of normality (by Shapiro-Wilk) [

33,

34], examination of kurtosis, skewness, and standard errors [

35,

36,

37], as well as visual inspection of the histograms, normal Q-Q plots, and box plots. In this subset, tests for homogeneity of variances (Levene's) [

38,

39] were also conducted to determine the homoscedasticity/heteroscedasticity of the data. When we have more than 30 samples per subgroup and our data are non-normally distributed but with homogeneity of variances, we performed Independent Sample T-Tests on all normally distributed with homogeneity of variances data in the 2002 and 2012 sample data and we applied the Central Limit Theorem. Mean Rank (MR) performed a direct analysis of data using the Mann-Whitney U Test (U) or the Kruskal-Wallis H test (H) on data with non-normal distribution and no homogeneity of variances. If p < 0.05, all null hypotheses were rejected.

3. Results

3.1. Traditional olive orchards versus hedgerow olive orchards#

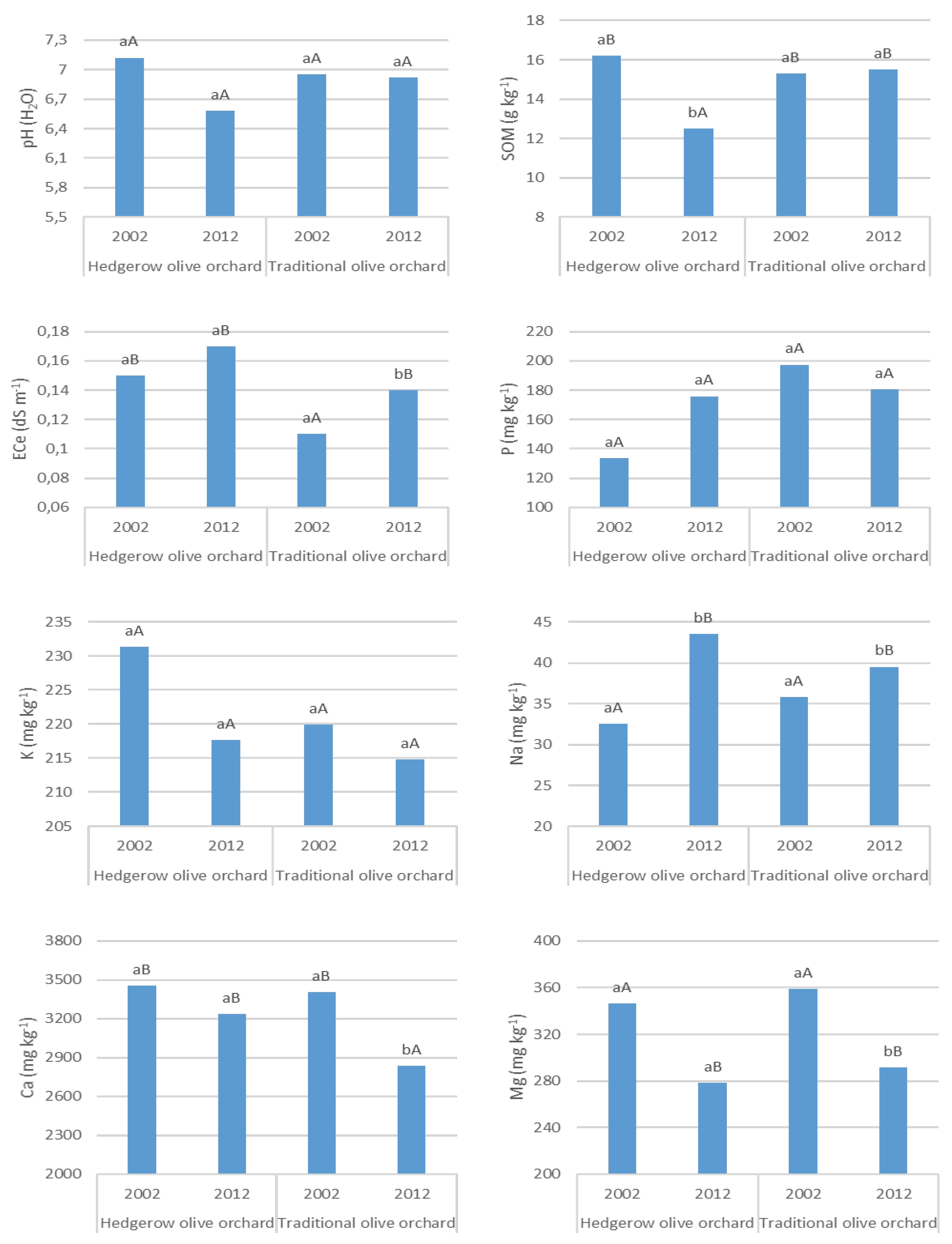

The main results about this topic can be found in

Figure 4.

3.1.1. pH

As can be seen in the results, although not significantly, there is a slight decrease in soil pH in both crop systems under analysis (

Figure 4). However, while in rainfed olive groves this decrease is only 0.03, in the case of irrigated olive groves this decrease is 0.54.

3.1.2. Soil Organic Matter (SOM)

Regarding soil organic matter, there is a significant difference between traditional rainfed olive orchards and hedgerow-irrigated olive orchards. While in the first case the SOM content remains almost constant during the period under analysis, even registering a slight, non-significant, increase, in the second case the SOM content decreases significantly (a decrease of 22.8%). This result is important given the importance that this soil component, normally with very low levels throughout the Mediterranean Basin, has in soil physical, chemical, and biological properties [

40]. This result is also important when we analyze the different influences of these two agro-systems on carbon sequestration and, consequently, on the climate crisis [

41].

3.1.3. Electrical Conductivity (Ec)

Concerning electrical conductivity, we obtained results contrary to what would be expected, and to the ones reported by, for example, Ramos et al., (2019) [

19]. Thus, while in hedgerow olive groves the values of this parameter did not change significantly during the decade under analysis, in the case of rainfed olive groves this value rose significantly.

3.1.4. Extractable P, K, Ca, Mg and Na

In the case of extractable phosphorus and potassium, there are no significant differences, either over time or between cropping systems. Regarding extractable Ca and Mg in the soil, there is a highly significant decrease in the levels of these elements in traditional rainfed olive groves. In super-intensive irrigated olive groves, although there is a slight decrease, this result is not statistically significant.

Regarding extractable Sodium, directly related to the sodium content in the exchange complex [

23], an important element that can have a harmful effect on the soil structure when and if it exists in the soil exchange complex in excessive amounts (more than 10%), we found a significant increase in both production systems. In the case of super-intensive olive groves, this increase is highly significant (p<0.001) and corresponds to an increase of 33.8%. In the case of traditional rainfed olive groves, this increase is also significant (p<0.05) and corresponds to an increase of 10.3%. It should also be noted that in 2002 the rainfed olive groves had a slightly higher amount of soil extractable sodium content than the irrigated olive groves (3% lower). However, this trend was reversed in just a decade. Nowadays the super-intensive irrigated olive grove presents a soil extractable sodium content 10% higher than the non-irrigated ones.

3.1.5. Extractable Cd, Cu, Fe, Zn, Pb, Ni and Mn

Regarding Cd, Cu, Fe, Zn, Ni, Pb and Mn, as we can see in

Table 3, in the case of super-intensive irrigated olive groves, the content of these elements grew for all of them over the decade considered, with this growth having statistical significance in the cases of Cu, Fe and Ni. In the case of traditional rainfed olive groves, the levels of Cd and Ni decreased, with statistical significance, and the levels of Zn and Mn increased significantly.

3.2. Hedgerow olive orchard versus other irrigated crops (corn, tomato, cereals, others)

When we analyze the evolution, over a decade, in the soil chemical composition as a function of the crop installed in the irrigated area (

Table 4), several results are worth to be mentioned.

3.2.1. pH

Regarding soil pH, we found that most crops grown in the Caia Irrigation Perimeter region led to soil alkalinization, which is significant in the case of corn, tomato, and cereals. This alkalization is particularly evident in the case of tomato, with increases of 1.13 units.

The exception to this scenario occurs in the olive orchards. In this crop, there is a small decrease, not statistically significant, in pH.

3.2.2. Electrical Conductivity (Ec)

Although not reaching potentially dangerous values for the crops, the electrical conductivity of the soil increased over the decade under analysis in all crops, and these differences were significant in the case of corn, cereal crops and “other crops”.

3.2.3. Soil Organic Matter (SOM)

Regarding soil organic matter, we can see that in the case of corn, tomato and autumn/winter cereal crops there were no significant changes over the decade considered. In the irrigated olive orchards, the result is different, with a significant decrease in soil organic matter content over the decade under analysis.

3.2.4. Extractable P, K, Ca, Mg and Na

In the case of extractable phosphorus and potassium, the results obtained are closely dependent on the application of fertilizers, given that these parameters have an anthropogenic influence much higher than those observed for the parameters treated above, with a strong inter-annual and intra-annual variation. However, we can refer to a trend towards the growth of soil phosphorus levels in the considered crops over the decade under analysis, which is significant in the case of corn and tomato.

For extractable potassium, the dependence on fertilizers application is similar to the one we described for phosphorus. In the results, we can notice a significant increase in the potassium content of soils occupied with corn (the crop that receives the greatest amounts of fertilizers) and a significant decrease in the levels of potassium in soils occupied with olive orchards.

Regarding Extractable Ca, there were no general trends in their content variation. So, in the case of corn and olive orchards, no significant variation occurs. Nevertheless, in the case of tomato we can verify a significant increase in extractable Ca concentration, which could be explained by the specific needs for this nutrient of this particular crop.

In soil extractable Mg content, in regard to corn and tomato we couldn’t verify any significant variation over the decade under analysis, in the case of olive orchards we can notice a significant decrease in extractable Mg content.

Regarding extractable sodium, directly related, as we previously mentioned, in exchange sodium, we can notice that it rises significantly in all crops analyzed during the considered decade. It’s important to notice that there is a greater increase in sodium levels in olive and cereal crops and, although equally significant, a smaller increase in tomato and corn crops.

4. Discussion

4.1. Traditional olive orchard versus hedgerow olive orchards

4.1.1. pH

The difference registered in pH values between the two systems under analysis, although not significant, can be due to the nitrogen fertilizer applied, which is practically not used in rainfed olive groves and is used in high amounts in irrigated olive groves (150 to 170 kg N ha

-1 year

-1). When nitrogen is applied in the ammoniacal form, which often happens as a way to reduce the losses of this nutrient by leaching, the natural process of nitrification leads to acidification of the soils [

23]. Other explanations, such as the leaching of basic cations do not apply here, since irrigation is strictly controlled, and there is no possibility of a significant increase in the leaching process due to the irrigation practice.

Also, the organic matter mineralization can have some influence on this result, because, as we have seen before, the SOM mineralization is bigger in the irrigated olive groves and therefore can contribute to soil acidification.

4.1.2. Soil Organic Matter (SOM)

The organic matter content in the soil depends, among other aspects, on two antagonist mechanisms. On the one hand, mineralization, on the other hand the production and deposition of organic matter [

21]. The problem arises because the factors that lead to an increase in organic matter mineralization, among which soil tillage and the introduction of irrigation, are the same factors that lead to an increase in the production and deposition of organic matter. Besides this, it becomes extremely difficult to completely separate each of the factors that lead to an increase or decrease in SOM, given that, for example, the introduction of irrigation is almost always associated with an intensification, with more soil tillage and/or use of fertilizers, and the introduction of new crops or varieties, and it is not possible to know exactly which of these changes is the most influential one in the variation of soil organic matter content [

40].

It's important to note that, when we go from traditional rainfed olive groves to irrigated olive groves, many factors affecting soil organic matter content must be considered, besides the introduction of irrigation and fertilizers, also the type of tillage carried out, the existence or lack of intergrass between the rows and the incorporation or absense of pruning firewood [

42]. What we have in use today are these SOM ways of preservation, but this was not always the case and organic matter loss by mineralization was a recurring factor. Nevertheless, according to Yu et al. (2019) soil moisture has the highest correlation with soil organic matter mineralization, explaining between 54.8 and 62.2% of this process in Mediterranean regions. If we consider temperature and soil moisture, according to Rey et al. (2002) [

44], the two factors can explain about 91% of the soil mineralization process in semi-arid conditions.

While worldwide the introduction of irrigation seems to lead to an increase in the SOMcontent, with an increment between 11 and 35% as reported by Trost et al. (2013) [

45], at a more local level the results are very distinct and vary according to the particular situation. McGill et al., (2018) [

46], report increases in soil organic matter content, of 1% per year, for 12 years at least, in an irrigated maize crop, when compared with rainfed plots in the same crop.

Nevertheless, according to Francaviglia et al. (2017) [

47], the introduction of irrigation leads to greater water availability in the soil, especially in the hottest period of the year, which promotes biological activity and, consequently, organic matter mineralization. This author, while working on a cambisol, noticed that the introduction of irrigation water into a previously rainfed agricultural system leads to a much higher organic matter oxidation, which does not happen in rainfed systems due to the lack of humidity during the summer, when the organic matter mineralization process practically ceases. Also, Rotenberg et al., (2005) refer to reductions of 18 % in SOM content when moving from rainfed to irrigated wheat production. Evrendilek et al. (2004) [

49], working on a Tipic Haploxeroll, report that cultural intensification caused by irrigation led to a 50% decrease in soil organic matter content, which led to an increase in bulk density and erosion risk of, respectively, 10.5% and 46.2%.

It's also important to notice that the new intensive irrigated olive orchards are fertilized, unlike traditional rainfed olive orchards where fertilization was very low or non-existent. The effect of fertilization depends, however, on factors such as the fertilizer used, amounts applied and the pH of the soil. Works such as those by Álvaro-Fuentes et al. (2012) [

50], unlike our work, arrive at results that the application of nitrogen in the amounts of 60 and 120 kg N ha

-1, leads to increases in the SOM content, both in the no-tillage system and in conventional tillage system, due to the increase in biomass production, an important aspect that we already mentioned before. An opposite result arrives from Deng et al. (2017) which claims that the addition of fertilizers, namely nitrogen fertilizers, accelerates the decomposition of organic matter by soil microorganisms and therefore the SOM content tends to decrease.

4.1.3. Electrical Conductivity (Ec)

The introduction in soil of ions by irrigation water and fertilization would lead to the assumption that Ec values would increase more in olive groves managed in hedgerows, where these inputs are used to a greater extent [

52]. However, our results showed that traditional olive groves, without irrigation or fertilization in most cases, although with lower values, had a more pronounced increase in the Ec in this period. This result may be due to a greater evaporation in the latter system, bringing to the more superficial soil layers ions that were not washed away during the winter period [

53], because of the lack of rain enhanced by climate change [

2,

54], which led to a precipitation decrease in this region of around 20% in a decade. To this result also contributes the fact that the irrigation water used in a very controlled quantity, as previously mentioned, was of good quality and therefore the potential Ec increase in irrigated areas was not so evident. In addition to this, olive groves grown under hedges, with greater growth and production potential, inevitably have a greater uptake of ions when compared to traditional rainfed olive groves [

52], and therefore the ions concentration in the top layer of the soil in the first system can be lower. Nevertheless, the registered values, in both cases, are very low and without any possibility of negatively affecting the development of this crop.

4.1.4. Extractable P, K, Ca, Mg and Na

In the case of extractable phosphorus and potassium, these two elements whose levels depend a lot on the fertilization carried out, we believe this type of variation to be normal, since a greater application certainly corresponds to a greater consumption. These two nutrients are very important in the quality of the olive oil produced [

55].

The variation registered in Extractable Ca and Mg content is, in our opinion, related to the pH corrections, using CaCO

3 or MgCO

3, to which the olive orchards in the super-intensive production system are frequently subjected to in order to optimize the production conditions, which do not happen in the traditional rainfed olive groves. The supply of Ca and Mg by these alkaline products counteracts the decrease in the levels of these elements caused by the consumption of plants and possible leaching. The Ca and Mg transported by irrigation water could also contribute to this result, namely in the last years, when the water carbonates content in the irrigation water increased substantially (from 64 to 98 mg L

-1) [

23].

According to Abdel Kawy and Ali (2012) the result obtained for extractable Na can be explained by the sodium transported by irrigation water. In our case, given that the water used in irrigation has an average content of 11.2 mg L

-1 of Na (

Table 1) and taking into account that the super-intensive olive grove receives, on average, 3000 m

3 ha

-1 year

-1 (table 2), this corresponds to a sodium input into the soil of approximately 33.6 kg of Na year

-1 ha

-1, which, in a highly controlled irrigation system and with reduced leaching, can, also due to the low natural rainfall, lead to the accumulation of sodium in the soil.

These results coincide with other works carried out in the Mediterranean Basin, such as those by Bouaroudj et al. (2019) Gonçalves and Martins (2015) and Telo da Gama et al., (2019) [

23], these authors also highlight this result, stating that this is a result that deserves our utmost attention and should be constantly monitored, since, in their opinion, soil sodization in the Mediterranean Basin seems to be something inevitable, taken into account that the amount of precipitation in this region is insufficient to carry out an effective leaching of salts, and there is also the tendency for a sharp decrease in these precipitations, given the climate change scenario.

4.1.5. Extractable Cd, Cu, Fe, Zn, Pb, Ni and Mn

The quantity of extractable heavy metals and semimetals in soil depends on the total content of the element, the adsorption capacity of the soil and physicochemical factors such as pH and redox potential, which control the balance between the adsorbed fractions and those of the soil solution [

58]. As these elements are, in general, not applied in the form of fertilizers (nevertheless, the fertilizers could contain some amounts of these elements, although the application of these elements is not a goal of fertilization) and their concentration in phytopharmaceuticals, except for copper, is much reduced, the explanation for the variation of their content will be related to the natural conditions of the soil Rodríguez-[

59]. For example, in some Mediterranean soils, according to Jebreen et al. (2018) [

60], rocks are composed of three main minerals: calcite with impurities of Mn, Fe, Zn, Co, Sr, Pb, Mg, Cu, Al, Ni, V, Cr and Mo, dolomite with impurities of Fe, Mn, Co, Pb and Zn and aragonite with common impurities of Sr, Ba, Pb and Zn.

For instance, in the case of Fe, a very important nutrient for olive trees, we found a substantial accumulation of Fe oxides in the soils where CO32- concentrations were higher than 50%.

It´s also important to note that the bioavailability of these elements is affected by many factors, including pH, redox potential, SOM, CEC, macronutrient levels, available water content, temperature, etc., and therefore the presence of water can have some influence in the bioavailability of these elements, namely because of their influence in the redox potential of the soil. In our results, this influence wasn't clear. Nevertheless, the heavy metals content of the soil is far from the limits presented by Portuguese legislation (

Table 5)

4.2. Hedgerow olive orchards versus other irrigated crops (corn, tomato, cereals, others)

4.2.1. pH

The soil alkalinization, common in arid and semi-arid climates, depends on factors such as the irrigation period, the volume of water applied and the composition of the irrigation water, especially its balance in basic cations and bicarbonates, as well as the oxidation of organic compounds and ammonium ion nitrification [

62]. In this particular case, since the water used for irrigation is of good quality (C1S1 or C1S2 according to the USDA classification), but with high levels of calcium, magnesium and carbonates, this result can be easily explained. To this composition of irrigation water, which enhances alkalisation, we can add a low annual precipitation that leads to a low leaching of basic cations (Ca

2+, Mg

2+, K

+ and Na

+), thus meeting the conditions for an increase in pH values.

In olive orchards, the explanation for the result obtained, contrary to other irrigated crops, lies in the smaller amount of basic cations introduced by the irrigation water (less amount of water applied) and in the acidification caused by the mineralization of soil organic matter, given that, as we will see below, this is the only crop with a significant reduction in this soil compound and these facts are significantly correlated (data not presented in this work). We can notice, in

Table 4, that the initial pH value was higher in olive orchards. This fact is common in Mediterranean regions, where farmers select more alkaline soils to install the olive orchards. This trend was completely reversed during the decade under analysis.

4.2.2. Electrical Conductivity (Ec)

The Ec values depend mainly on anthropic issues. Both fertilizers, used in larger quantities in irrigated agriculture, and the ions transported by irrigation water [

63], even in good quality irrigation water as in this case, introduce high amounts of salts into the soil, leading to an increase in soil salinity [

57]. This fact is particularly relevant in the soils of the Mediterranean Basin where winter rainfall is insufficient to promote the leaching of excess salts. This is a particularly important aspect, given that about 25% of the soils in the Mediterranean Basin are salinized [

64], putting the agricultural productivity of these regions at serious risk [

65]. This phenomenon depends on irrigation water quality, soil geology, climate, physiographic position, and agricultural practices [

66]. This same result was obtained by several authors such as Ayars et al. (1993) who found that, after 6 years of continuous irrigation, the irrigated plots had a significantly higher Ec than the rainfed plots and that this result was more evident when the irrigation water used had a greater amount of salts. Ferjani et al. (2013) while working on clayey soils, reported a strong variation in EC throughout the year, decreasing from 8.40 dS m

-1 in the summer to 2.00 dS m

-1 in the winter. This decrease is due to salts that were washed away by the rainduring this period. In our results, we can also verify that the crops that received the highest volumes of irrigation water, such as corn, are those whose EC values have grown the most over a decade, which is in agreement with the consulted bibliography. It´s also important to notice, as we can see in

Table 4, that there is a close relationship between irrigation water consumption and fertilizers used in the different crops. Therefore, a possible explanation to this variation in Ec values may be a greater use of fertilizers in crops such as corn or tomato.

4.2.3. Soil Organic Matter (SOM)

Maintaining soil organic matter levels in corn, tomato and cereal crops is of great importance for the sustainability of irrigation agroecosystems in the Mediterranean regions. For this result, it was very important the implementation of conservation agriculture practices, which began around 15 to 20 years ago in the region. Leaving the crop residues, after being destroyed, in the soil and the practice of no-tillage are thus giving visible results, contrary to the trend that occurred in previous decades in this same region and reported in Nunes (2003) [

21].

This result is shared by several authors, namely Martinez-Mena et al. (2002) who mentioned that in the Mediterranean region, the practice of conservation agriculture, without tillage and the incorporation of crop residues, over the span of 9 years, led to a 0.31 times increase in SOM content, when compared to systems of conventional agriculture, with tillage and removal of crop residues. This result is very important, given that irrigation is generally seen as a technique that reduces SOM levels, as the water supplied during the hottest season of the year positively influences the mineralization process [

47,

70]. Our results proved that in semi-arid climates, especially with conservation agriculture practices, as it occurs mainly in mays and cereal production, it is possible to maintain this important soil compound. This last result is confirmed by the work of Álvaro-Fuentes et al. (2009) who concluded, in a study carried out in a Calciorthid Xerollico with a clayey texture, in the region of Zaragoza-Spain, that if the cultural intensification is carried out in non-tillage systems, the SOM content can increase significantly. Of course, all these results are highly dependent on the type of soil, the volume of water used for irrigation, quality of irrigation water and fertilization, but also on the climate and the initial content of SOM [

45].

Several explanations can be found for the result obtained in the intensive olive orchards; which in-depth knowledge of the region's agricultural systems allows us to highlight. Firstly, the amount of residues produced in the olive grove is substantially lower than the residues produced in the aforementioned crops, and the practice of cover crops between the rows is recent. In fact, according to Lal (2005) corn, wheat and tomato crops annually produce about 10.1, 5.0 and 5.0 Mg ha

-1 year

-1, respectively, of organic residues, while, in olive groves, if we remove pruning residues, a common practice until a few years ago, the amount of residues left in the soil will be less than 1 Mg ha

-1 year

-1, clearly not enough to replace the organic matter that disappears through mineralization [

73]. As previously mentioned, this scenario tends to be inverted due to the practices of conservation agriculture implemented in recent years, which foresees the incorporation into the soil of the pruning residues and the herbaceous vegetation existing between the rows – cover crops.

4.2.4. Extractable P, K, Ca, Mg and Na

The results obtained for extractable P, which may indicate an over-fertilization with this nutrient, are particularly evident in crops that receive larger amounts of fertilizers, namely in corn and tomato crops, as mentioned above. This fact is mentioned in the work by Monteiro and Torent (2010) Where they refer that over-fertilization with phosphorus has been happening in the Mediterranean Basinand the work by Butusov and Jernelov (2013) who also mention the environmental risks of this practice.

In the case of extractable potassium, the anthropogenic influence is also the main influence on the levels of these nutrients. Adequate potassium content in plants is of enormous importance for the adequate control of transpiration and for increasing the efficiency of water use in irrigation and should be one of the nutrients monitored in these production systems [

76].

It should be noted that according to the soil nutrient content classification produced for the Egner-Riehm extraction method (0-25 mg kg-1 – very low; 25-50 mg kg-1 – low; 50 – 100 mg kg-1 medium; 100-200 mg kg-1 – High and > 200 mg kg-1 – very high), the laboratory method used in this work, extractable phosphorus and potassium contents are always presented as high and very high, thus not constituting, in general, any obstacle to the productivity of the plants.

In the case of Ca and Mg, we emphasize the enormous increase in the concentration of calcium in the soil, significant in statistical terms, observed in the tomato crop. This result is explained by the supplementary application of calcium in this crop, as a way of reducing the risk of tomato apical rot. The explanation for the results obtained in soil extractable Na lies mainly in the sodium transported by the irrigation water, and this same fact has been stated by Bouaroudj et al. (2019) [

22]. This result was also verified in studies conducted by Belaid et al. (2010) who found that, after 15 years of continued irrigation, the physical properties of the soil were degraded due to the increase in sodium content in the soil, which was particularly evident when water with a higher sodium content was used.

In our study, we found a greater increase in sodium levels in olive and cereal crops and, although equally significant, a smaller increase in corn crops. On the one hand, since the corn crop receives the largest volume of irrigation water, applied almost always using sprinkler irrigation, we believe that the amount of sodium supplied to the soil by the irrigation water would be greater, but, on the other hand, this volume of water will also have led to some leaching of salts, which did not happen, for example, in olive groves, where drip irrigation provides a much greater control over the amount of water supplied and, consequently, a greater irrigation efficiency. We had already found a similar result when we analyzed the Ce of soils occupied with traditional olive groves versus hedged olive groves, exactly for the same reasons.

5. Conclusions

The main conclusion of this work is that the hedgerow olive grove leads to impacts on the chemical characteristics of the soil, different from the impacts caused by the traditional olive grove. Firstly, we can verify that the hedgerow olive grove promotes soil acidification and a significant decrease in SOM content when compared with traditional olive groves. On the other hand, this new production system doesn’t affect soil Ec values, when this parameter rises significantly in the traditional production system. Soil sodification happens significantly in both production systems. Nevertheless While the increase is about 33% in hedgerow olive groves, it's only 10% for rainfed olive groves.

Unlike the other irrigated crops analyzed (corn, tomato and cereals), the hedgerow olive grove led to a significant decrease in soil pH and SOM content. Regarding electrical conductivity and extractable sodium content, the increase in both parameters is generalized among various crops, and there were no significant differences between the crops analyzed.

Using a large quantity of soil samples can be really helpful to better grasp the impact on soil chemical characteristics caused by new olive production systems? For that reason, it's important to keep monitoring parameters such as pH, SOM, Ec and Na content, to guarantee the sustainability of these new and more intensive production systems.

References

- Montanaro, G.; Xiloyannis, C.; Nuzzo, V.; Dichio, B. Orchard management, soil organic carbon and ecosystem services in Mediterranean fruit tree crops. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 217, 92-101. [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Castro, S.; Gonçalves, J.F.; Moreno, M.; Villar, R. Projected climate changes are expected to decrease the suitability and production of olive varieties in southern Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 709, 136161. [CrossRef]

- FAO. World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2022. Rome. [CrossRef]

- Loumou, A.; Giourga, C. Olive groves: “The life and identity of the Mediterranean”. Agric. Hum. Values, 2003, 20, 87–95. [CrossRef]

- Connor, D. J.; Ferreres, E. 2010. The physiology of adaptation and yield expression in olive Horticultural Reviews, 2010, 31. [CrossRef]

- Tous, J.; Romero, A.; Hermoso, J.F. New trends in olive orchard design for continuous mechanical harvesting. Adv. Hortic. Sci., 2010, 24, 43–52.

- Connor, D.J. Adaptation of olive (Olea europaea L.) to water-limited environments. Aust. J. Agric. Res., 2005, 56, 1181–1189. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez Escobar. R.; De la Rosa, R.; Leon, L.; Gomez, J. A.; Testi, F.; Orgaz, M.; Gil-Ribes, J. A.; Quesada Moraga, E.; Trapero, A. Evolution and sustainability of the olive production systems, N. Arcas (Ed.), Present and future of the Mediterranean olive sector. Zaragoza: CIHEAM / IOCF.N. Arroyo López, J. Caballero, R. D'Andria, M. Fernández, R. Fernandez Escobar, A. Garrido, ..., R. Zanoli (Eds.), Options Méditerranéennes: Série A. Séminaires Méditerranéens; n. 106, 2013, pp. 11-42.

- Gómez, J., Sobrinho, T., Giráldez, J., Fereres, E. Soil management effects on runoff, erosion and soil properties in an olive grove of Southern Spain. Soil and Tillage Research, 2009, 102: 5-13. [CrossRef]

- Cameira, M. R.; Pereira, A.; Ahuja, L.; Ma, L. Sustainability and environmental assessment of fertigation in an intensive olive grove under Mediterranean conditions, Agricultural Water Management, 2014, 146, 346-360, ISSN 0378-3774. [CrossRef]

- Rallo, L.; Caruzo, T.; Diez, C.M.; Campisi, G. Olive growing in a time of change: From empiricism to genomics. In The Olive Tree Genome; Rugini, L.B., Muleo, R., Sebastiani, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016, pp. 55–64.

- Kavvadias, V.; Papadopoulou, M.; Vavoulidou, E.; Theocharopoulos, S.; Repas, S.; Koubouris, G.; Psarras, G.; Kokkinos, G. 2018. Effect of addition of organic materials and irrigation practices on soil quality in olive groves. Journal of Water and Climate Change 1 December 2018; 9 (4): 775–785. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Sousa, A.A.; Barandica, J.M.; Rescia, A. Ecological and Economic Sustainability in Olive Groves with Different Irrigation Management and Levels of Erosion: A Case Study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4681. [CrossRef]

- Morgado, R., Santana, J., Porto, M., Sanchez-Oliver, ´ J. S., Reino, L., Herrera, J. M., Rego, F., Beja, P., & Moreira, F. A Mediterranean silent spring? The effects of olive farming intensification on breeding bird communities. Agriculture Ecosystems and Environment, 2020, 288, Article 106694. [CrossRef]

- Morgado, R.; Ribeiro, P. F.; Santos, J. L.; Rego, F.; Beja, P.; Moreira, F. Drivers of irrigated olive grove expansion in Mediterranean landscapes and associated biodiversity impacts, Landscape and Urban Planning, 2022, 225, 104429, ISSN 0169-2046. [CrossRef]

- Vila-Traver, J., Aguilera, E., Infante-Amate, J.; de Molina, M. G. Climate change and industrialization as the main drivers of Spanish agriculture water stress. Science of The Total Environment, 2021, 760, Article 143399. [CrossRef]

- Palma, P., Kuster, M., Alvarenga, P., Palma, V. L., Fernandes, R. M., Soares, A. M. V. M., Lopez ´ de Alda, M. J., Barcelo, ´ D., & Barbosa, I. R. Risk assessment of representative and priority pesticides, in surface water of the Alqueva reservoir (South of Portugal) using on-line solid phase extraction-liquid chromatographytandem mass spectrometry. Environment International, 2009, 35, 545–551. [CrossRef]

- Vanwalleghem, T., Amate, J. I., de Molina, M. G., Fernandez, D. S., & Gomez, J. A. Quantifying the effect of historical soil management on soil erosion rates in Mediterranean olive orchards. Agriculture Ecosystems and Environment, 2011, 142, 341–351. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, T. B., Darouich, H., Sim ˇ ůnek, J., Gonçalves, M. C., & Martins, J. C. Soil salinization in very high-density olive orchards grown in southern Portugal: Current risks and possible trends. Agricultural Water Management, 2019, 217, 265–281. [CrossRef]

- Michalopoulos, G.; Kasapi, K.A.; Koubouris, G.; Psarras, G.; Arampatzis, G.; Hatzigiannakis, E.; Kavvadias, V.; Xiloyannis, C.; Montanaro, G.; Malliaraki, S.; Angelaki, A.; Manolaraki, C.; Giakoumaki, G.; Reppas, S.; Kourgialas, N.; Kokkinos, G. Adaptation of Mediterranean Olive Groves to Climate Change through Sustainable Cultivation Practices. Climate, 2020, 8, 54. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J. Los suelos del perimetro regable del Caia (Portugal): Tipos, fertilidad e impacto del riego en sus propriedades químicas. Ph.D Thesis, Universidad de Extremadura, Badajoz, Spain. 2003.

- Bouaroudj, S.; Menad, A.; Bounamous, A.; Ali-Khodja, H.; Gherib, A.; Weigel, D. E.; Chenchouni, H. Assessment of water quality at the largest dam in Algeria (Beni Haroun Dam) and effects of irrigation on soil characteristics of agricultural lands, Chemosphere, 2019, 219, 76-88, ISSN 0045-6535. [CrossRef]

- Telo da Gama, J.; Rato Nunes, J.; Loures, L.; Lopez Piñeiro, A.; Vivas, P. Assessing Spatial and Temporal Variability for Some Edaphic Characteristics of Mediterranean Rainfed and Irrigated Soils. Agronomy, 2019, 9, 132. [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, A.; Dell’Aquila, R. Effects of irrigation with saline waters, at different concentrations, on soil physical and chemical characteristics, Agricultural Water Management, 2005, 77 (1–3), 308-322, ISSN 0378-3774. [CrossRef]

- Chemura, A. , Kutywayo, D. , Chagwesha, T. and Chidoko, P. An Assessment of Irrigation Water Quality and Selected Soil Parameters at Mutema Irrigation Scheme, Zimbabwe. Journal of Water Resource and Protection, 2014, 6, 132-140. [CrossRef]

- Bogunovic, I.; Leon T.; Pereira, P.; , Vilim, F.; Lana, F.; Aleksandra, P.; Boris, D.; Márta, B.; Igor, D.; and Comino, J. R. Land management impacts on soil properties and initial soil erosion processes in olives and vegetable crops. Journal of Hydrology and Hydromechanics, 2020, 68-4, 328-337. [CrossRef]

- FAO. World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2014: International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. ISBN 978-92-5-108369-7.

- Telo da Gama, J., Loures, L., López-Piñeiro, A., & Nunes, J. R. Assessing the Role of Phosphorus as a Macropollutant in Four Typical Mediterranean Basin Soils. Sustainability, 2021, 13(19), 10973. [CrossRef]

- Buurman, P., Van Lagen, B., y Velthorst, E. J. Manual for soil and water analysis. Backhuys, 1996.

- Nelson, D. W., y Sommers, L. Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter 1. Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 2. Chemical and Microbiological Properties, (methodsofsoilan2), 1982. 539–579.

- USDA. Soil Survey Laboratory Methods Manual. Soil Survey Investigation Report no 42, Version 3 (p. 692). USA: United State Department of Agriculture. 1996.

- Egnér, H., Riehm, H., y Domingo, W. R. Investigations on chemical soil analysis as the basis for estimating soil fertility. II. Chemical extraction methods for phosphorus and potassium determination. Kungliga Lantbrukshögskolans Annaler, 1960, 26, 199–215.

- Shapiro, S. S., y Wilk, M. B. An Analysis of Variance Test for Normality (Complete Samples). Biometrika, 1965, 52(3/4), 591. [CrossRef]

- Razali, N. M., y Wah, Y. B. Power comparisons of shapiro-wilk, kolmogorov-smirnov, lilliefors and anderson-darling tests. Journal of Statistical Modeling and Analytics, 2011, 2(1), 21–33.

- Cramer, D. Fundamental statistics for social research: Step-by-step calculations and computer techniques using SPSS for Windows. Routledge. 2003.

- Cramer, D., y Howitt, D. L. The Sage dictionary of statistics: A practical resource for students in the social sciences. Sage. 2004.

- Doane, D. P., y Seward, L. E. Measuring skewness: A forgotten statistic? Journal of Statistics Education, 2011, 19(2).

- Nordstokke, D. W., y Zumbo, B. D. A new nonparametric Levene test for equal variances. Psicologica: International Journal of Methodology and Experimental Psychology, 2010, 31(2), 401–430.

- Nordstokke, D. W., Zumbo, B. D., Cairns, S. L., y Saklofske, D. H. The operating characteristics of the nonparametric Levene test for equal variances with assessment and evaluation data. Practical Assessment, Research y Evaluation, 2011, 16.

- Wiesmeier, M., Poeplau, C., Sierra, C. A., Maier, H., Frühauf, C., Hübner, R., Kühnel, A., Spörlein, P., Geuß, U., Hangen, E., Schilling, B., von Lützow, M., & Kögel-Knabner, I. Projected loss of soil or-ganic carbon in temperate agricultural soils in the 21(st) century: effects of climate change and carbon input trends. Scientific Reports, 6, 32525. 2016.

- Ziska, L.H.; Bradley, B.A.; Wallace, R.D.; Bargeron, C.T.; LaForest, J.H.; Choudhury, R.A.; Garrett, K.A.; Vega, F.E. Climate Change, Carbon Dioxide, and Pest Biology, Managing the Future: Coffee as a Case Study. Agronomy, 2018, 8, 152. [CrossRef]

- Franco-Luesma, S.; Cavero, J.; Plaza-Bonilla, D.; Cantero-Martínez, C.; Arrúe, J.L.; Álvaro-Fuentes, J. Tillage and 605 Irrigation System Effects on Soil Carbon Dioxide (CO2) and Methane (CH4) Emissions in a Maize Monoculture 606 under Mediterranean Conditions. Soil Tillage Res. 2020, 196, 104488. [CrossRef]

- Yu, O.T.; Greenhut, R.F.; O’Geen, A.T.; Mackey, B.; Horwath, W.R.; Steenwerth, K.L. Precipitation Events, Soil Type, and Vineyard Management Practices Influence Soil Carbon Dynamics in a Mediterranean Climate (Lodi, 597 California). Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2019, 83, 772–779. [CrossRef]

- Rey, A.; Pegoraro, E.; Tedeschi, V.; De Parri, I.; Jarvis, P.G.; Valentini, R. Annual Variation in Soil Respiration 593 and Its Components in a Coppice Oak Forest in Central Italy. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2002, 8, 851–866, 594. [CrossRef]

- Trost, B., Prochnow, A., Drastig, K.; Meyer-Aurich, A.; Ellmer, F.; Baumecker, M. Irrigation, soil organic carbon and N2O emissions. A review. Agron. Sustain. 2013. Dev. 33, 733–749. [CrossRef]

- McGill, B. M., Hamilton, S. K., Millar, N., & Robertson, G. P. The greenhouse gas cost of agricultural intensification with groundwater irrigation in a Midwest US row cropping system. Global Change Biology, 2018, 24(12), 5948–5960. [CrossRef]

- Francaviglia, R.; Di Bene, C.; Farina, R., Salvati L. Soil organic carbon sequestration and tillage systems in the Mediterranean Basin: a data mining approach. Nutr Cycl Agroecosyst, 2017, 107, 125–137. [CrossRef]

- Rotenberg, D., Cooperband, L., & Stone, A. Dynamic relationships between soil properties and foliar disease as affected by annual additions of organic amendment to a sandy-soil vegetable production system. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2005, 37(7), 1343-1357.

- Evrendilek, F.; Celik, I.; Kilic, S. Changes in soil organic carbon and other physical soil properties along adjacent Mediterranean forest, grassland, and cropland ecosystems in Turkey, Journal of Arid Environments, 2004, 59 - 4, 743-752, ISSN 0140-1963. [CrossRef]

- Álvaro-Fuentes, J.; Morell, F.; Plaza-Bonilla, D.; Arrúe, J.; Cantero-Martínez, C. Modelling tillage and nitrogen fertilization effects on soil organic carbon dynamics. Soil and Tillage Research, 2012, 120, 32-39, ISSN 0167-1987. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Hui, D.; Dennis, S.; Reddy, K.C. Responses of terrestrial ecosystem phosphorus cycling to nitrogen addition: A meta-analysis. Global Ecol. Biogeogr., 2017, 26, 713-728. [CrossRef]

- Sobreiro, J.; Patanita, M.I.; Patanita, M.; Tomaz, A. Sustainability of High-Density Olive Orchards: Hints for Irrigation Management and Agroecological Approaches. Water, 2023, 15, 2486. [CrossRef]

- Tekaya, M.; Mechri, B.; Dabbaghi, O.; Mahjoub, Z.; Laamari, S.; Chihaoui, B.; Boujnah, D.; Hammami, M.; Chehab, H. Changes in key photosynthetic parameters of olive trees following soil tillage and wastewater irrigation, modified olive oil quality. Agricultural Water Management, 2016, 178, 180-188, ISSN 0378-3774. [CrossRef]

- Corwin, DL. Climate change impacts on soil salinity in agricultural areas. Eur J Soil Sci. 2021; 72: 842– 862. [CrossRef]

- Erel, R., Yermiyhu, Y., Ben-Gal, A. and Dag, A. Olive fertilization under intensive cultivation management. Acta Hortic., 2018, 1217, 207-224. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Kawy, W.; Ali, R.R. Assessment of soil degradation and resilience at northeast Nile Delta, Egypt: The impact on soil productivity. The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science, 2012, 15-1, 19-30, ISSN 1110-9823. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M. C.; Martins, J. C. A salinização do solo em Portugal. Causas, extensão e soluções, 13, 2015.

- Alloway, B. J. Heavy metals in soils: Trace metals and metalloids in soils and their bioavailability (3. ed). Dordrecht: Springer. 2013.

- Martín, J. A., Ramos-Miras, J. J., Boluda, R., y Gil, C. Spatial relations of heavy metals in arable and greenhouse soils of a Mediterranean environment region (Spain). Geoderma, 2013, 200–201, 180–188. [CrossRef]

- Jebreen, H., Wohnlich, S., Banning, A., Wisotzky, F., Niedermayr, A., y Ghanem, M. Recharge, geochemical processes and water quality in karst aquifers: Central West Bank, Palestine. Environmental Earth Sciences, 2018, 77(6), 261. [CrossRef]

- Carreira, J., Lajtha, K., y Niell, X. Phosphorus transformations along a soil/vegetation series of fire-prone, dolomitic, semi-arid shrublands of southern Spain Soil P and Mediterranean shrubland dynamic, 1997,34.

- Ayoub, S.; Al-Shdiefat, S.; Rawashdeh, H.; Bashabsheh, I. Utilization of reclaimed wastewater for olive irrigation: Effect on soil properties, tree growth, yield and oil content. Agricultural Water Management, 2016, 176, 163-169, ISSN 0378-3774. [CrossRef]

- Ghassemi, F. ; Jakeman, A. J. ; Nix, H. A. Salinisation of land and water resources: human causes, extent, management and case studies. pp. 544. ISBN. 0851989063, 1995.

- Lagacherie, P.; Álvaro-Fuentes, J.; Annabi, M.; Bernoux, M.; Bouarfa, S.; Douaoui, A.; Grunberger, O.; Hammani, A.; Mrabet, R.; Sabur, M.; Raclot, D. Managing Mediterranean soil resources under global change: expected trends and mitigation strategies. Reg Environ Change, 2018, 18, 663–675. [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, R. Soil Salinity and Water Quality. Routledge. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.; Carvalho, J.; Souza, K.; Vasconcelos, C.; Andrade L. Efeitos da salinidade da água de irrigação na brotação e desenvolvimento inicial da cana-de-açúcar (Saccharum spp) e em solos com diferentes níveis texturais. Ciência e Agrotecnologia 2007, 31-5, 1470-1476. [CrossRef]

- Ayars, J.E.; Hutmacher, R.B.; Schoneman, R.A. Vail S. S.; Pflaum, T. Long term use of saline water for irrigation. Irrig Sci., 1993, 14, 27–34. [CrossRef]

- Ferjani, N.; Daghari, H.; Hammami, M. Assessment of Actual Irrigation Management in Kalâat El Andalous District (Tunisia): Impact on Soil Salinity and Water Table Level. Journal of Agricultural Science, 2013, 5(5) 46. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Mena, M.; Alvarez Rogel, J.; Castillo, V.; Albadalejo, J. Organic carbon and nitrogen losses influenced by vegetation removal in a semiarid mediterranean soil. Biogeochemistry, 2002, 61, 309–321. [CrossRef]

- Singh, B. Are Nitrogen Fertilizers Deleterious to Soil Health? Agronomy, 2018 8, 48. [CrossRef]

- Álvaro-Fuentes, J.; López, M. V.; Arrúe, J.; Moret, D.; Paustian, K. Tillage and cropping effects on soil organic carbon in Mediterranean semiarid agroecosystems: Testing the Century model. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2009, 134 (3–4), 211-217, ISSN 0167-8809. [CrossRef]

- Lal. R. World crop residues production and implications of its use as a biofuel, Environment International, 2005, Volume 31, Issue 4, Pages 575-584, ISSN 0160-4120. [CrossRef]

- Pena D., Albarran A., Lopez-Pineiro A., Rato-Nunes J.M., Sanchez-Llerena J., Becerra D. Impact of oiled and de-oiled olive mill waste amendments on the sorption, leaching, and persistence of S-metolachlor in a calcareous clay soil, Journal of Environmental Science and Health - Part B Pesticides, Food Contaminants, and Agricultural Wastes, 2013, 48 (9) , 767-775. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, M.; Torent, J. Dinâmica do fósforo no solo: Prespeivas agronómica e ambiental. Castelo Branco: IPCB. ISBN 978-989-8196-10-1, 2010, 97p.

- Butusov, M.; Jernelöv A. Phosphorus: An Element that could have been called Lucifer. Springer Briefs in Environmental Science eds., 2013. [CrossRef]

- Abd El–Mageed, T. SA.; El-Sherif, A.; Ali, M.; Abd El-Wahed, M. 2017 Combined effect of deficit irrigation and potassium fertilizer on physiological response, plant water status and yield of soybean in calcareous soil, Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science, 2017, 63:6, 827-840. [CrossRef]

- Belaid, N.; Neel, C.; Kallel, M.; Ayoub, T.; Ayadi, A.; Baudu, M. 2010. Effects of treated wastewater irrigation on soil salinity and sodicity in Sfax (Tunisia): A case study. Journal of Water Science, 2010, 23 (2), 133–146. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).