Introduction

Neurological disorders are quite common, with congenital/inborn disorders very difficult to diagnose or detect

1. Intellectual disability, autism, and other associated disorders are known to affect 1-3% of the world population, with an incidence of 1 in 12,000 live births

2. Although the NCBI’s dbSNP (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/ last accessed on December 6, 2023) is validated, and ClinVar (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/ last accessed on December 6, 2023) has a compendium of bona fide and records, not all data is reviewed thoroughly. For example, several disease-causing genes that are known, with specific genetic diagnosis remain elusive in many cases

3, and as these are all heterogeneous groups of disorders, various mutations associated with developmental defects and dysfunction are nor properly reviewed and annotated. The last decade has led to a better understanding of disease diagnosis, owing to chromosomal breakpoint mapping, multi-omics integration, systems genomics approaches, whole-genome array-based copy-number analysis, and nanostring panels besides the emphasis on understanding the pedigree structure for molecular diagnosis

4. In this work, we attempt to identify pathogenic mutations in three neurological diseases,

viz. arthrogryposis, bilateral congenital cataracts, and Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD). The autism spectrum is a neurodevelopmental condition that is visible at the beginning of early childhood and lasts throughout a person’s life

5. As it affects the nervous system, the affected person lacks cognitive, emotional, social and physical health. The severity and duration of symptoms might vary substantially with severe communication and social interaction issues with repetitive behavior patterns. Knowing the genetic origin of ASD could be one of the most critical aspects of future diagnosis and therapy. Likewise, arthrogryposis is a condition that causes a variety of joint contractures. It is a complicated aetiological illness that affects one in 3000 live babies, although the prenatal frequency is higher, signifying a high intrauterine mortality rate

6. The disease’s genetic diversity has been demonstrated by linking it to 400 distinct genes. Intrinsic/primary/fetal etiology is caused by abnormalities in different body sections, including the brain, nerve cells, muscles, bones, tendons, joints, etc. Amongst the 400 genes implicated, nine newly found genes including

CNTNAP1, MAGEL2, ADGRG6,

ASXL3 and

STAC3 harbor pathogenic variants

7.

Summary of cases

The individuals were recruited from an outpatient clinic of Lifecare Hospitals, Amravati, Maharashtra, India. Before taking the patients’ DNA samples and subjecting them to clinical exome sequencing, informed consent was duly obtained from their parents. A clinical exome panel was chosen to check the list of pathogenic variants with an in-house pipeline benchmarked by us to screen and filter the candidate variants8. We have recently established a consensus variant pipeline for exome analysis called CONVEX, and we used it to identify variants at stringency (Ujjwal and Ranjana et al. communicated 2023). The Fastq files (paired-end reads) containing the raw reads were retrieved and utilized for downstream processing. The variants filtered were obtained in variant calling format (VCF) file, and the SNP-nexus9 yielding variants were thoroughly checked for ClinVar-mapped variations based on RefSeq (rs) IDs. GeneMANIA was used to find the genes most strongly associated with the gene responsible for these phenotypes and Phenolyzer was used to analyze distinct pathways10,11. The characteristics of the children with neurological disorders are discussed below.

Case summary 1

NV (name acronymed, anonymised), an 8-year-old male child, is referred to as having a known case of focal arthrogryposis with delayed development. He was born full term by the vaginal route and had meconium-stained liquor along with crossed leg and contracture of the elbow and bilateral right hamstring and iliotibial band. During six days of hospitalization, no hypoglycemia and convulsion were noted. For contracture, he was operated on at the age of 3 years. In antenatal ultrasonography, he was found to have a short femur and humerus, and the mother had hyperemesis during the whole pregnancy. He had global developmental delay (GDD) and microcephaly (head circumference of 50 cm) and other examination findings indicate broad nose, long toes, laxity of fingers, with hyperextensibility of knees and elbow. Our further counseling in lieu of familial history revealed that his sister was similarly but only mildly affected than him. On referral to the neurologist, an investigation showed normal karyotype, electromyography (EMG), and nerve conduction study (NCV) with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed paucity of white matter.

Case summary 2

AB (name acronymed, anonymised), aged 7, was presented with microcephaly and autism, born from a healthy labor. The clinical examination showed failure to recognize things, with significant speech delay. He was born from a non consanguineous marriage without significant family history. Previous studies revealed that chr 14:75094726 with the gene ID (EIF2B2) plays a very crucial role in pathogenesis and is found in various rare diseases like inclusion body myopathy with paget disease of bone and frontotemporal dementia, chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia, mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, isolated atrial amyloidosis, narcolepsy, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, lactic acidosis, congenital central hypoventilation syndrome and congenital myasthenic syndrome.

Case summary 3

DB (name acronymed, anonymised), an 8-month-old male, was presented for genetic evaluation i/v/o bilateral cataract, failure to thrive, and some developmental delay. The mother had a fever without a rash during the first two months of pregnancy for 2-3 days of admission. While antenatal ultrasound showed signs of early onset intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR), he was born preterm with low birth weight (1.7 kg), requiring neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission for eight days. The clinical examination showed microcephaly, failure to thrive, and small anterior fontanelle (AF) with a prominent metopic suture. He had normal motor development but had significant speech delay (only cooning) and was born of a non-consanguineous marriage without a significant family history. The ophthalmic examination showed bilateral cataracts (right > left) with intraocular calcification. Other investigations showed normal to complete hemogram, toxoplasma and other, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex (TORCH) negative, normal renal and liver function test except increased alkaline phosphatase level (567 units/L). The computerized tomography (CT) of the brain showed generalized cerebral shrinkage with prominence of cortical sulci and cisternal spaces with bilateral periventricular volume loss and ex vacuo prominence of frontal horns.

Discussions

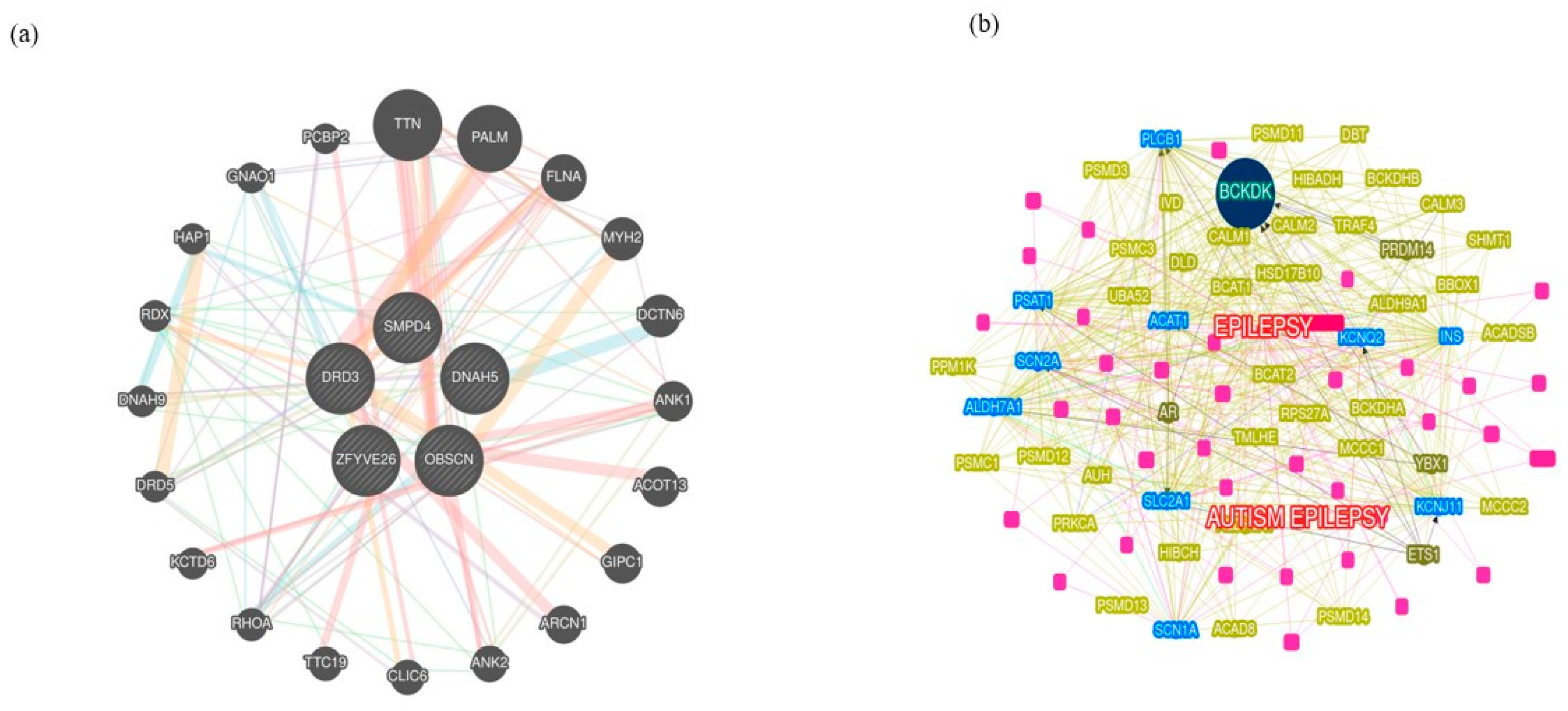

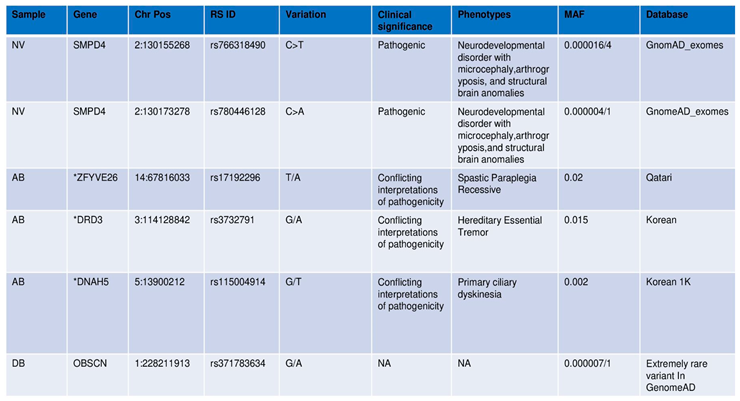

Three variants in SMPD4 are known to be associated with arthrogryposis

SMPD4 is the only known gene implicated in Arthrogryposis even as our exome sequencing and further analyses found three variants derived from the same gene,

SMPD4 (

Table 1). These are found on chromosome 2 (rs766318490, rs780446128, and rs1391542283) with minor allele frequency (MAF) for the first two variants attributing to <=0.0001%, showing that they are extremely rare variants. While the MAF of rs766318490 and rs780446128 in the GnomAD attribute minor allele to T=0.000016/4 and A=0.000004/1, respectively, the ALFA database showed T=0.000051/1 and A=0./0. rs1391542283, GeneMANIA yielded distinct interactions for

SMPD4, and many pathways,

viz. transcription regulation, factors, cell adhesion, chromatin binding, and neurodegeneration are associated (

Figure 1).

SMPD4 is associated with ceramide and is produced by sphingomyelinases as a secondary messenger in intracellular signaling pathways involved in the cell cycle, differentiation, or death.

SMPD4 mediates TNF-stimulated oxidant generation in skeletal muscle. Genomic research showed bi-allelic loss-of-function mutations in

SMPD4, which codes for the neutral sphingomyelinase-3 (nSMase-3/

SMPD4). However, we could not find any

SMPD4 variants attributing to pathogenesis from our CONVEX pipeline. Proteomics research on human Myc-tagged

SMPD4 overexpression demonstrated localization to both the outer nuclear envelope and the ER and interactions with multiple nuclear pore complex proteins. Fibroblasts from afflicted people had aberrant ER cisternae, suggesting enhanced autophagy, and were more vulnerable to apoptosis under stress circumstances, whereas

SMPD4 therapy slowed cell cycle progression. It has been demonstrated that

SMPD4 connects membrane sphingolipid homeostasis to cell fate by regulating the cross-talk between the ER and the outer nuclear envelope and that its absence indicates a pathogenic mechanism in Microcephaly

12.

Pathogenic variants associated with microcephaly and autism

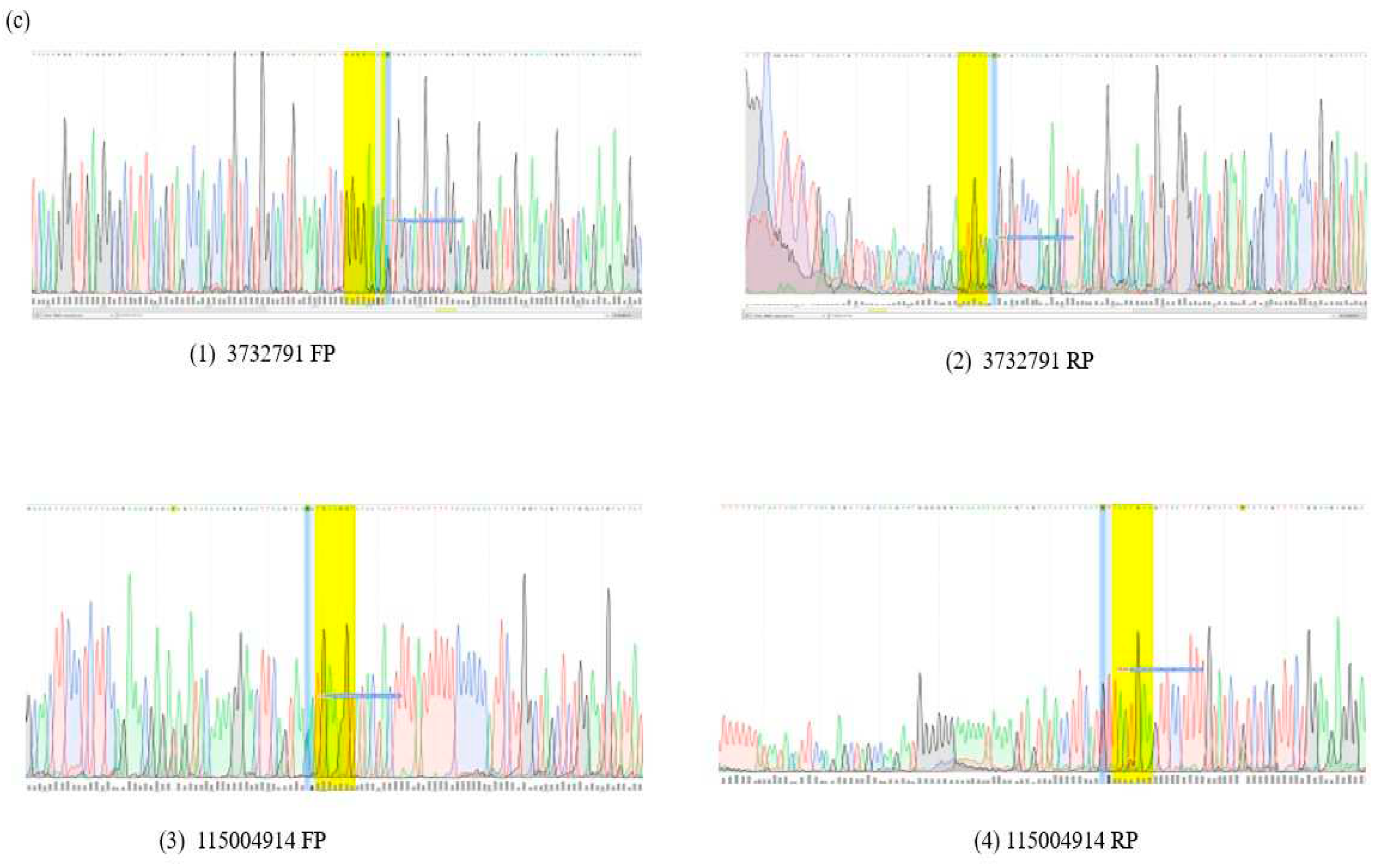

The pathogenic variants were screened for AB, and a final list of 15 variants was filtered across subpopulation databases and specific phenotype matches based on their MAF, clinical significance, and phenotypes. The four pathogenic variants,

viz. NM_001104.4(ACTN3):c.1729C>T(p.Arg577Ter); NM_015346.4(ZFYVE26):c.-70A>T; NM_000796.6(DRD3):c.1077C>T(p.His359=); NM_001369.3(DNAH5):c.2253C>A (p.Asn751Lys). All the variants mentioned above were found on chromosome positions 11,14,3,5 respectively, and were linked with neurodevelopmental disorders like Schizophrenia and structural brain anomalies. A few extremely rare variants with MAF <=0.001 were identified for the filtered set matching the index case. These variants were further searched in the Indian genome variant database, Indigen (

https://clingen.igib.res.in/indigen last accessed on December 6, 2023) in addition to ALFA and GnomAD_exomes reporting these variants (Indicated with * in

Table 1), however, from the latest ClinVar mapping, we found them to be benign.

Further shortlisting to three pathogenic variants was done and were probed to check whether they are associated with inherent pathways, The genes harboring mutations are

ACTN3 (Alpha-actinin-3),

DRD3 (Dopamine receptor D3),

DNAH5 (Dynein axonemal heavy chain 5) and

ZFYVE26 (Zinc finger five types containing 26) were the candidates inherent to CBC even as we obtained D3 subtype receptor proteins inhibiting adenylyl cyclase pathways (

Figure 1). The receptor is localized to the limbic areas of the brain, associated with cognitive, emotional, and endocrine function. Several literature studies show that this gene has some association with ASD

13. A SNP of the

DRD3 gene (rs167771) was recently associated with ASD with different polymorphisms corresponding to varying degrees of behavior. In contrast, the other two genes are the normal genes unrelated to neurological disease. We further sought to check whether or not Phenolyzer pathways revealed the diagnosis of PWS and how four genes,

viz. DRD3, DNAH5, ZFYVE26, and

ACTN3 are associated with the phenotypes represented by HPO terms. The branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase

(BCKDK) is a seed gene, on chromosome 16 associated with mitochondrial protein kinases family and regulates the catabolic pathways for valine, leucine, and isoleucine. By searching two related types of syndromic ASD-one caused by mutations in branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase and the other by mutations in branched-chain ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase. Lower BCAA levels may also be detrimental to brain development, as evidenced by the discovery of BCKDH mutations in families with ASD, ID, and seizures. Other genes

ACAT1, SLC2AL, ALDH7A1,

SCN2A, PSAT1, SCNIA, and

KCNJ11 are all connected and may likely cause some neurological disorders.

Conclusions

Genetic variation attributing to pathogenesis is a significant bottleneck. In this work, we attempted to understand rare neurological disorders in an Indian pediatric cohort using exome studies. While we used both pipelines, the CONVEX pipeline did not yield pathogenic variants for consensus variant calling tools. Nevertheless, EIF2B2 is inherently pathogenic, and the interpretations match the two pipelines. While these are the diseased correlations, we find that neuroleptic malignant syndrome may cause brain damage, which is a matching phenotype. Our study has certain limitations, viz. (a) parental genotyping or family exome analyses was not done, which could bring candidate germline mutations associated with these disorders. Despite the lack of parental data and the potential for misdiagnosis, this study identifies the inherent pathogenicity of EIF2B2 and its association with neuroleptic malignant syndrome and brain damage. However, we acknowledge that our findings are specific to a particular region in India and may not be attributable to the entire population. (b) The potential presence of intronic variants and the limited scope of exome sequencing necessitate further investigation with whole-genome sequencing and functional studies. Identifying EIF2B2 as a disease-causing gene offers a promising avenue for future research and development of targeted therapies for these rare neurological disorders. Small sample sizes may not be typical for the general population, especially in rare diseases. If the research population is not diverse, the results may not be applied to other ethnic or demographic groups. The clinical exome panel may not cover all crucial genes or areas, and variation categorization might be complex and subjective. Exome sequencing may overlook regulatory regions and non-coding variations that may play a role in illness, and variant identification methods may yield false positives or false negatives. Using ClinVar alone to evaluate variants has limits, and prediction methods may not always adequately represent in vivo biological importance. Finally, as monogenic disorders are rare and poorly understood, it hints at a general restriction in our understanding of rare diseases. Because the CONVEX pipeline is considered a consensus variant pipeline, it is critical to confirm its performance by comparing it to known standards and datasets. Because genomics is a dynamic field, new genes and variant classifications might develop, affecting study findings’ relevance and accuracy over time. This research lays the groundwork for further explorations into the genetic landscape of rare neurological disorders in the Indian population, paving the path for improved diagnosis, treatment, and, ultimately, a brighter future for those affected by these debilitating conditions.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Study reference numbers are for DB - LC/2020/11/004, FOR NW LC/2019/008 FOR AB LCO/2021/06/016.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the parents for their vivid support of samples.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Ethics clearance

Informed consent and ethical approvals were taken duly before carrying out the clinical exome panel.

References

- Campistol, J et al. “Errores congénitos del metabolismo con manifestaciones neurológicas de presentación neonatal” [Inborn errors of metabolism with neurological symptomatology in the neonatal period]. Revista de neurología vol. 40,6 (2005): 321-6. [CrossRef]

- Charman, T et al. “IQ in children with autism spectrum disorders: data from the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP).” Psychological medicine vol. 41,3 (2011): 619-27. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Maria et al. “The genetic basis of disease.” Essays in biochemistry vol. 62,5 643-723. 2 Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Suravajhala P, Kogelman LJ, Kadarmideen HN. Multi-omic data integration and analysis using systems genomics approaches: methods and applications in animal production, health, and welfare. Genet Sel Evol. 2016 Apr 29;48(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12711-016-0217-x. Faras, Hadeel et al. “Autism spectrum disorders.” Annals of Saudi medicine vol. 30,4 (2010): 295-300. doi:10.4103/0256-4947.65261.

- Bamshad M, Van Heest AE, Pleasure D. Arthrogryposis: a review and update. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009 Jul;91 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):40-6. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00281. Hall, Judith G, and Jeff Kiefer. “Arthrogryposis as a Syndrome: Gene Ontology Analysis.” Molecular syndromology vol. 7,3 (2016): 101-9. [CrossRef]

- Meena, N., Mathur, P., Medicherla, K. M. and Suravajhala, P. (2018). A Bioinformatics Pipeline for Whole Exome Sequencing: Overview of the Processing and Steps from Raw Data to Downstream Analysis. Bio-101: e2805. [CrossRef]

- Franz M, Rodriguez H, Lopes C, Zuberi K, Montojo J, Bader GD, Morris Q. GeneMANIA update 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018 Jul 2;46(W1): W60-W64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky311. Dayem Ullah AZ, Oscanoa J, Wang J, Nagano A, Lemoine NR, Chelala C. SNPnexus: assessing the functional relevance of genetic variation to facilitate the promise of precision medicine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018 Jul 2;46(W1):W109-W113. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky399.

- Yang H, Robinson PN, Wang K. Phenolyzer: phenotype-based prioritization of candidate genes for human diseases. Nat Methods. 2015 Sep;12(9):841-3. [CrossRef]

- Magini P, Smits DJ, Vandervore L, Schot R, Columbaro M, Kasteleijn E, van der Ent M, Palombo F, Lequin MH, Dremmen M, de Wit MCY, Severino M, Divizia MT, Striano P, Ordonez-Herrera N, Alhashem A, Al Fares A, Al Ghamdi M, Rolfs A, Bauer P, Demmers J, Verheijen FW, Wilke M, van Slegtenhorst M, van der Spek PJ, Seri M, Jansen AC, Stottmann RW, Hufnagel RB, Hopkin RJ, Aljeaid D, Wiszniewski W, Gawlinski P, Laure-Kamionowska M, Alkuraya FS, Akleh H, Stanley V, Musaev D, Gleeson JG, Zaki MS, Brunetti-Pierri N, Cappuccio G, Davidov B, Basel-Salmon L, Bazak L, Shahar NR, Bertoli-Avella A, Mirzaa GM, Dobyns WB, Pippucci T, Fornerod M, Mancini GMS. Loss of SMPD4 Causes a Developmental Disorder Characterized by Microcephaly and Congenital Arthrogryposis. Am J Hum Genet. 2019 Oct 3;105(4):689-705. [CrossRef]

- Staal WG, Langen M, van Dijk S, Mensen VT, Durston S. DRD3 gene and striatum in autism spectrum disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2015 May;206(5):431-2. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).