1. Introduction

Rare pediatric neurological diseases (RPND) represent one of the most complex challenges in modern medicine. It is known that more than 7,000 rare diseases have been registered, approximately 80% of which have a genetic basis and may first manifest during childhood, including various neurological pathologies. Although each individual diagnosis is rare (approximately 1 in 10,000–40,000 newborns), rare diseases collectively affect 6–8% of the population, corresponding to over 300 million people worldwide. These figures are supported by international organizations such as EURORDIS (

https://www.eurordis.org) and Orphanet (

https://www.orpha.net) [

1].

RPND are characterized by high clinical complexity, heterogeneity of presentation, often unclear etiology, and progressive course, leading to severe disability, reduced quality of life, and increased mortality in children. Traditional diagnostic methods often result in prolonged diagnostic processes involving numerous examinations, consultations, and repeated testing. According to Orphanet, approximately 70% of rare diseases begin in childhood, and the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) reports that the diagnostic odyssey may last from 3 to 7 years (

https://rarediseases.org/rare-disease-information/what-are-rare-diseases/). A study published in Genetics in Medicine showed that more than 60% of patients with rare genetic diseases underwent over five standard diagnostic procedures before receiving an accurate diagnosis, which significantly increases the financial burden on the healthcare system and exerts substantial emotional stress on families [

2,

3]. These data highlight the need to adopt new methodological approaches capable of reducing diagnostic time and resource expenditures.

In recent years, significant progress has been made in the fields of deep phenotyping and genomics, offering innovative opportunities for diagnostics. Deep phenotyping enables the identification of even subtle clinical features that may be overlooked during standard clinical assessments [

4]. Robinson (2012) emphasized that detailed phenotypic descriptions are a cornerstone of implementing precision medicine principles [

5]. When integrated with genomic technologies such as exome sequencing (ES) or genome sequencing (GS), it becomes possible to accurately correlate phenotypic manifestations with genetic mutations, thereby substantially increasing diagnostic accuracy [

6].

In several regions, access to advanced next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies remains limited [

7]. In settings where the use of costly sequencing platforms is constrained, deep phenotyping can serve as an effective pre-laboratory method for patient selection for subsequent genetic testing. This approach narrows the range of suspected genetic conditions based on clinical presentation, contributing to more rational resource utilization and reducing the overall cost of molecular genetic diagnostics.

The integration of deep phenotyping and genomics is crucial for sustainable healthcare development. Accurate and early diagnosis optimizes the use of medical resources, reduces the need for additional testing, and ensures equitable access to advanced technologies, which is particularly relevant in resource-limited settings. The application of this integrated approach facilitates the timely initiation of targeted treatment, improves clinical outcomes, and alleviates both emotional and financial burdens on patient families. This approach aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) (

https://sdgs.un.org/goals) [

8].

The Study Objective is to develop and implement an integrated diagnostic approach combining deep phenotyping using the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO), ES with laboratory interpretation following American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines, and reverse phenotyping based on OMIM data [

9]. This approach aims to shorten the time to accurate diagnosis, optimize resource utilization, and ensure equitable access to modern diagnostic methods for rare pediatric neurological diseases. Ultimately, it is expected that combining deep and reverse phenotyping with ES will increase the proportion of genetically confirmed diagnoses and reduce the duration and number of diagnostic procedures.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is best classified as a retrospective observational study. Although patients were identified and deeply phenotyped according to a standardized prospective protocol, the key clinical and procedural variables—such as time to diagnosis, number of diagnostic interventions prior to ES, and turnaround time—were collected retrospectively from medical records. This design allowed for the evaluation of real-world diagnostic trajectories in children with suspected rare neurological diseases. Such a design allowed for a comprehensive assessment of the effectiveness of a diagnostic algorithm based on deep phenotyping and ES, with a focus on reducing the time to diagnosis and minimising the diagnostic burden in children suspected of having rare neurological diseases. The choice of this design is justified by its effectiveness in studying rare diseases, as it enables the implementation of an integrated diagnostic approach with rational use of time and resources [

10].

Patients were referred from 11 healthcare institutions in South Kazakhstan between July 1 and December 20, 2023. Key stages of the study—deep phenotyping and biological sample collection—were conducted at the Clinical and Diagnostic Center of the Khoja Akhmet Yassawi International Kazakh-Turkish University.

Before patient recruitment, individual and group training sessions were conducted for outpatient physicians. These sessions focused on recognizing rare neurological diseases with suspected genetic etiology. The training covered key phenotypic features of RPND and aimed to develop physicians’ skills in the early identification of patients who may benefit from deep phenotyping and genetic testing. Upon completion, pediatric neurologists and general practitioners referred patients who met the established criteria, ensuring high-quality patient selection for further investigation.

Initially, 250 children under the age of 18 with suspected RPND were considered for inclusion. The final study sample was determined based on strict inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion Criteria: complex neurological phenotype involving a combination of syndromes (e.g., epilepsy, cognitive impairment, movement disorders, neurodegeneration, psychiatric symptoms, peripheral neuropathy), clinical suspicion of hereditary etiology, progressive or relapsing disease course with unknown etiology, lack of definitive diagnosis following clinical and instrumental investigations.

Exclusion Criteria: established non-genetic causes (infectious, toxic, vascular brain lesions), neuromuscular diseases confirmed by electromyography, muscle biopsy, or molecular genetic testing, specific nosologies (e.g., isolated epilepsy, confirmed chromosomal abnormalities), significant structural brain abnormalities detected by MRI or CT that do not require genetic confirmation.

After applying these criteria, the final study sample included 81 patients. This sample size is sufficient for the objectives of the study, given the epidemiological rarity of the conditions under investigation and the stringent inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Each patient underwent a comprehensive clinical assessment including detailed history-taking, neurological examination, and review of instrumental findings [

4]. The goal of this phase was to standardize and systematize clinical data for subsequent correlation with genetic findings. Deep phenotyping was performed using the HPO system, allowing for structured and unified documentation of clinical manifestations.

- 1.

Clinical Examination and History Taking: Each patient underwent a detailed physical and neurological examination, assessing both central and peripheral nervous systems. History taking focused on identifying neurological and somatic symptoms, their onset, progression, and dynamics.

- 2.

HPO-Based Coding of Clinical Features: Identified clinical manifestations were converted into standardized terms using the HPO system. Each symptom, its severity, and specificity were recorded using appropriate HPO codes. Special attention was paid to the correct term hierarchy: parent terms define general clinical categories, while child terms specify particular manifestations within those categories. For example, if a patient had seizures, the parent term “Seizure” (HP:0001250) was used. If generalized seizures were present, the child term “Generalized clonic seizure” (HP:0011169) provided further detail. Similarly, “Severe muscular hypotonia” was recorded as HP:0006829.

- 3.

Phenotypic Profile Formation: Based on the coded HPO terms, an individual phenotypic profile was created for each patient. This profile served as an integrated clinical map, reflecting all detected symptoms and their characteristics. For instance, if a patient presented with generalized clonic seizures and severe muscular hypotonia, their profile would include: HP:0011169, and HP:0006829. This coding ensured a standardized and precise clinical description, which is critical for subsequent genetic interpretation.

- 4.

Phenotype Verification: At this stage, the phenotypic profiles were analyzed to eliminate redundant or non-informative data. Each phenotypic feature was assessed for clinical relevance and consistency with known disease patterns. Results were discussed during interdisciplinary case reviews. All verified data were uploaded to the 3billion laboratory portal to maintain accuracy and support the precise interpretation of genetic findings.

To identify the genetic causes of the disorders, ES was performed at the 3Billion laboratory in Seoul, South Korea. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood or dried blood spots using standard protocols. Exome capture was performed using the xGen Exome Research Panel v2 (Integrated DNA Technologies), supplemented with mitochondrial and custom panels. Sequencing was carried out on the NovaSeq X (Illumina, USA), achieving an average depth of 140× and ≥20× coverage for 99.6% of the targeted regions. Sequencing quality met clinical-grade standards (CAP, CLIA certified).

Raw data were processed using 3Billion’s bioinformatics pipeline EVIDENCE v4.2, which incorporates GATK (v4.4.0) for SNV/INDEL calling, Manta for structural variant detection, 3bCNV for copy number variation analysis, and ExpansionHunter, MELT, and AutoMap for repeat expansions, mobile element insertions, and regions of homozygosity, respectively. Variant annotation was performed using Ensembl’s Variant Effect Predictor (VEP v104.2) [

11].

Variants were filtered using a multi-parameter approach. First, allele frequency thresholds were applied, excluding variants with a minor allele frequency (MAF) ≥1% in the gnomAD v4.1.0 database. Second, predicted pathogenicity was assessed, with prioritization given to protein-truncating variants such as frameshift, nonsense, and canonical splice-site changes, as well as to missense variants predicted to be deleterious by multiple in silico tools, including SIFT, PolyPhen-2, and Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD). Third, inheritance patterns were considered, taking into account family history and zygosity (e.g., homozygous, compound heterozygous, de novo). Finally, only high-confidence variants with a sequencing depth of at least 20× were retained for analysis; low-quality or ambiguous variants were subjected to orthogonal validation by Sanger sequencing.

All variants were classified according to ACMG guidelines (Richards et al., 2015), integrating evidence from population databases, computational tools, prior literature, and gene-disease relationships. Importantly, each clinically significant or uncertain variant was reviewed by a multidisciplinary team, including pediatric neurologists and certified clinical geneticists. This manual validation step ensured the clinical accuracy and contextual relevance of the automated classification output from EVIDENCE.

Reverse phenotyping—the process of correlating identified genetic variants with a patient’s clinical manifestations to clarify their significance—was conducted using the OMIM database [

12]. The clinical profile of each patient was compared with phenotypic descriptions associated with the identified genetic variants. The genetic findings were analyzed during interdisciplinary case discussions involving neurologists and neurogeneticists, during which their diagnostic relevance and interpretation were assessed, including for variants of uncertain significance (VUS).

This study assessed the effectiveness of the diagnostic approach in terms of reducing the so-called “diagnostic odyssey”—the period from the appearance of the first symptoms to the establishment of a final diagnosis.

The analysis was based on two key parameters:

Duration of the Diagnostic Process - the time interval from the onset of the first symptoms to the patient’s inclusion in the study, as well as from the time of inclusion to the final diagnosis, was examined. This allowed the evaluation of whether the new diagnostic algorithm accelerated the diagnostic process.

Diagnostic Burden - the total number of diagnostic tests (e.g., specialist consultations, MRI, biopsies, etc.) conducted before and after the patient’s inclusion in the study was analyzed. This parameter enabled the assessment of whether the new diagnostic intervention reduced the number of additional investigations or, conversely, required more.

The obtained results will help determine the extent to which the proposed approach contributes to diagnostic optimization, reduction of time and resource expenditures, and improvement in the quality of medical care for patients.

Statistical analysis was performed using R software (version 4.3.1) and JASP (version 0.18.1). Descriptive statistics for quantitative variables were presented as median, interquartile range (IQR), range, and standard deviation, depending on the distribution of the data. Categorical variables were described using absolute numbers and percentages.

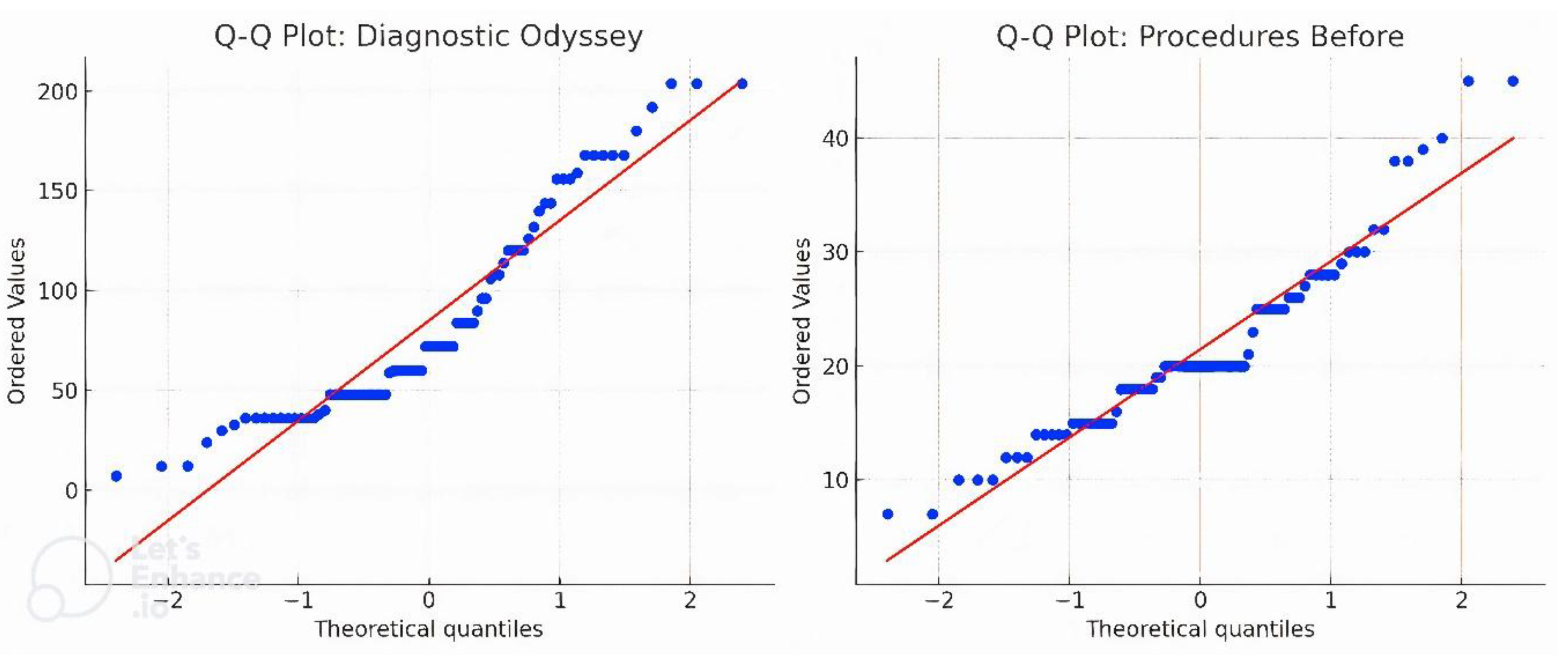

Normality of distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test and visual inspection of Q–Q plots. Due to deviations from normal distribution, Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare paired dependent samples.

To quantify the effect size, Cohen’s d coefficient (adapted for paired samples) was calculated. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for two-tailed tests. All calculations were conducted with 95% confidence intervals.

3. Results

The study included 81 patients with neurological symptoms, with a predominance of males (64.2%, male-to-female ratio: 52:29). Age at the time of evaluation ranged from 6 months to 17 years (median: 6 years; interquartile range: 4–11.5 years).

Almost all patients exhibited psychomotor developmental delay and intellectual disability: 78 out of 81 children (96.3%) had varying degrees of cognitive impairment. Severe or profound intellectual disability was observed in the majority of cases (approximately 78%), moderate in 13%, and mild in only 6%; only 2 patients demonstrated age-appropriate cognitive development.

Epileptic seizures were reported in 56 patients (67%). All participants had some degree of motor impairment: approximately 49% were unable to walk independently and had severe motor dysfunction corresponding to Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) levels IV–V, while 13% retained relatively preserved motor function (GMFCS level I).

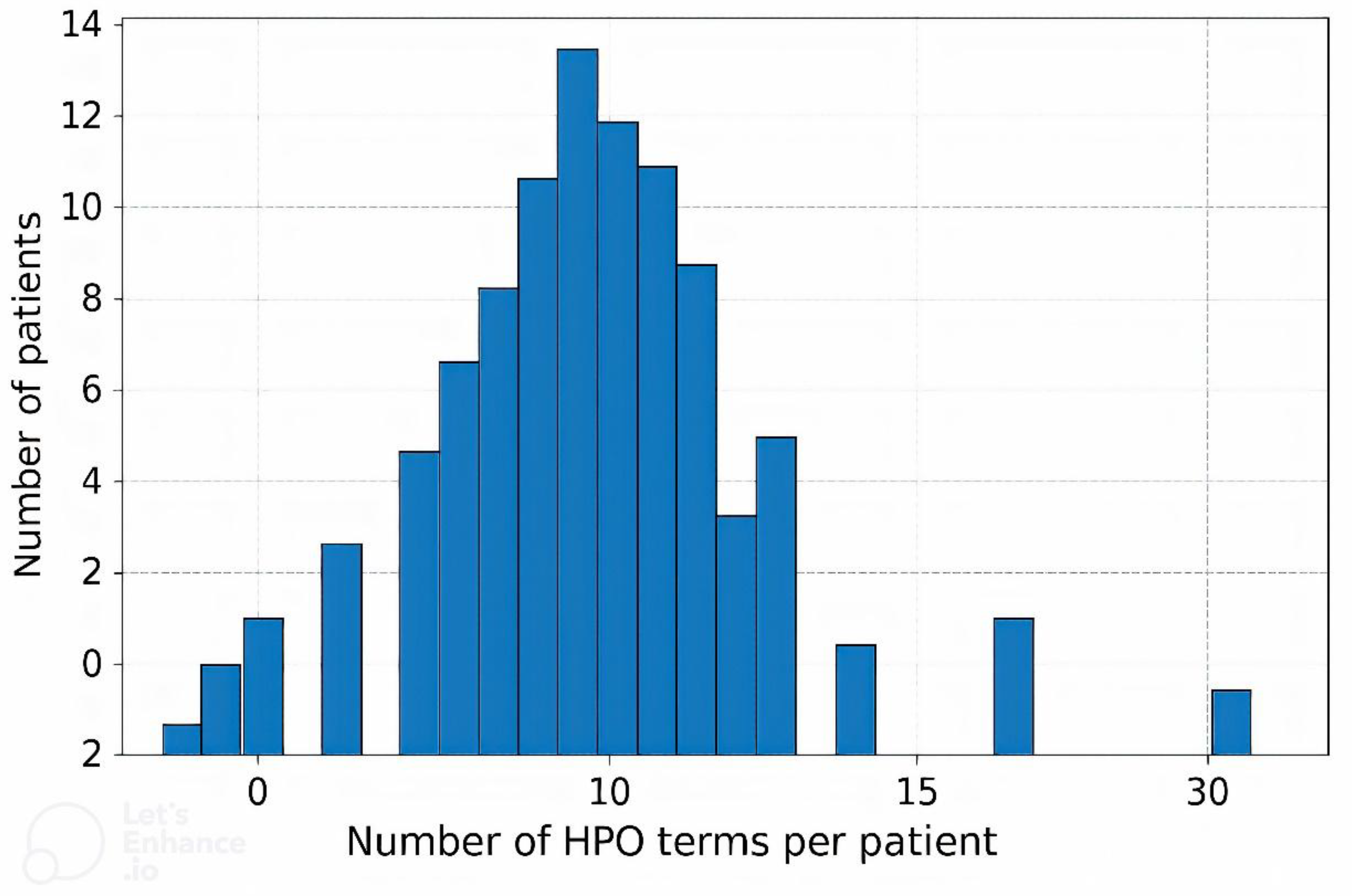

Each patient’s clinical phenotype was standardized and structured using HPO terms. On average, 12 HPO terms were assigned per patient (median: 11; range: 2–30), reflecting the spectrum of clinical manifestations. The most common neurological features included global developmental delay/intellectual disability, epilepsy, infantile hypotonia, and spastic paresis, among others. Nearly all patients exhibited complex phenotypes with multiple (two or more) manifestations, and in over half of the cases, 10 to 15 HPO terms were used to describe the phenotype.

The development of such detailed phenotypic profiles allowed for a standardized clinical description, which is essential for the interpretation of subsequent genetic testing results.

Figure 1 presents the distribution of the number of HPO terms per patient. The most frequently observed HPO terms are presented in

Figure 2. A detailed clinical characterization of the probands is presented in

Table 1 and

Table S1.

ES Results

In the study group of 81 patients, genomic variations were identified in 43 individuals (54.2%), including single nucleotide variants (SNV) in 38 patients (88.9%) and copy number variations (CNV) in 5 patients (11.1%).

Among the SNVs, a number of pathogenic / likely pathogenic and potentially significant genetic variants were identified (

Table 2,

Table S2). It should be noted that in one case, two SNVs were found — IDS and MKKS. A total of 39 rare variants were detected, of which, according to ACMG criteria, 18 were classified as pathogenic, 12 as likely pathogenic, and 9 as VUS. Mutations were found in 39 different genes, with the most frequently affected being SCN1A, TSC2, and ARID1B (two different variants identified in each gene in different patients).

A significant portion of the identified variants was associated with developmental and epileptic encephalopathies (DEE). Pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutations were identified in genes associated with DEE, including KCNQ2 (DEE7), SCN1A (Dravet syndrome, DEE type 6), SCN8A (DEE13), CDKL5 (DEE2), WWOX (DEE28), DNM1 (DEE31A), and GRIN2A (focal epilepsy with speech disorder and intellectual disability). Altogether, variants in DEE-related genes accounted for approximately 20% of all identified mutations.

Another large group of findings (35.5%) involved genes associated with neurodevelopmental disorders (intellectual disability, developmental and behavioral impairments). These included, for example, KDM6B and KCND2 (both associated with autosomal dominant forms of developmental delay), UBAP2L and BRAT1 (autosomal recessive neurodevelopmental syndromes), as well as TRIO, CUL4B, DYRK1A, and others.

In addition, a number of identified variants were linked to hereditary syndromic disorders: in our cohort, mutations were found that are associated with tuberous sclerosis (TSC1/TSC2), Costello syndrome (HRAS), Kabuki syndrome (KMT2D), Smith–Magenis syndrome (RAI1), Lowe syndrome (OCRL), Bardet–Biedl syndrome (MKKS), and other monogenic disorders.

Of particular note are the variants related to inherited metabolic diseases: in particular, pathogenic mutations were identified that cause Salla disease (SLC17A5) and L2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria (L2HGDH), as well as a mitochondrial mutation associated with MELAS syndrome (MTTL1).

The identified CNVs included deletions and duplications of various chromosomal regions associated with specific phenotypic manifestations (

Table 3). In Case 18, a duplication in 9p24.3p22.2 was detected in the patient, but it was not associated with any known syndromes. However, there have been reports of duplications partially or completely involving this genomic region, in which individuals exhibited phenotypic similarities to this patient [

13,

14,

15].

In the group of 30 patients with identified pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants, reverse phenotyping allowed for refinement of the clinical diagnosis in 100% of cases. In these cases, the patients’ clinical features were fully consistent with the identified genetic variants.

Reverse phenotyping also contributed to the identification of additional phenotypic features in 10 out of 30 patients (33.3%). During targeted re-evaluation, previously undocumented symptoms were discovered. Newly identified phenotypic manifestations included metabolic abnormalities, dysmorphic features, clinically insignificant cardiac arrhythmia, and others.

In the group of 9 patients with identified VUS, an in-depth analysis was performed using the reverse phenotyping approach combined with interdisciplinary discussion. In 88.9% of cases (8 out of 9 patients), the refined phenotypic profile was consistent with clinical features described in the literature for diseases associated with the respective gene. This enabled the formulation of a well-supported assumption regarding the likely pathogenic role of the identified variant in the patient’s clinical presentation.

When formulating the presumptive genetic diagnosis, the following factors were considered: concordance between the phenotype and known disease manifestations; results of repeated phenotypic assessment using HPO terms; and conclusions from the interdisciplinary case review. Although the formal classification of the variant remained as VUS, the obtained data strengthened its clinical relevance in the context of the individual case.

Prior to inclusion in the study, the median time interval from the onset of the first symptoms to participation in the study was 72 months (range: 6–204 months) (

Figure 3). Following participation in the study and the initiation of molecular genetic testing, this period was reduced to up to 5 months.

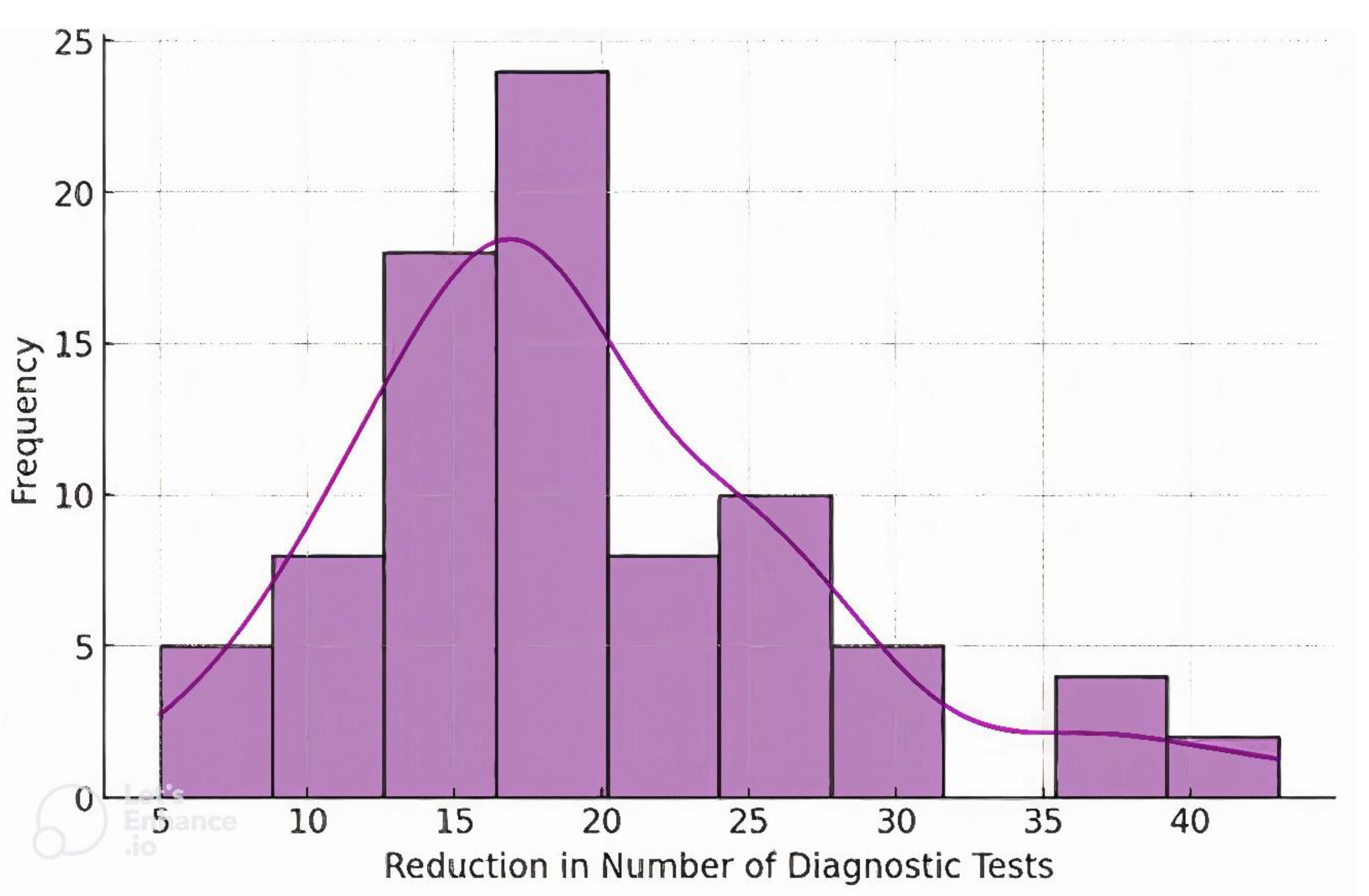

Before undergoing genetic testing, patients underwent an average of 20 different diagnostic procedures (

Figure 4). After the implementation of genetic testing and targeted confirmatory investigations, the median number of additional tests was 2 (

Table 1).

A comparison of these indicators before and after study participation demonstrates a marked reduction in the diagnostic odyssey. As a result of applying the new diagnostic approach, the average time to diagnosis was reduced by approximately 19-fold compared to the initial period, and the number of required diagnostic procedures decreased more than tenfold.

The Q–Q plots demonstrate deviations from normality in both the duration of the diagnostic odyssey and the number of diagnostic procedures before genetic testing, indicating non-normal data distribution (

Figure 5).

To assess the significance of differences in the duration of the diagnostic process before and after inclusion in the study, statistical data analysis was performed. The Shapiro–Wilk test revealed a deviation from normal distribution (p < 0.05) in both groups, which justified the use of a non-parametric comparison method. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired samples was applied to assess statistical differences.

The results showed that the median duration of the diagnostic odyssey was significantly reduced after implementation of the proposed diagnostic algorithm (p = 1.91 × 10⁻⁶). The main statistical indicators are presented in

Table 4. Effect Size Estimation: To quantitatively assess the magnitude of change, effect size (Cohen’s d) was calculated. The resulting value of d = 2.43 corresponds to a very strong effect in reducing diagnostic time.

4. Discussion

The results of our study demonstrate the high effectiveness of integrating deep phenotyping and genomic sequencing in the diagnosis of rare RPND. The diagnostic yield in our cohort reached 53% (43 of 81 patients received a genetically confirmed diagnosis), which is notably higher than that reported in studies employing genomic testing in the absence of standardized deep phenotyping approaches, such as Human Phenotype Ontology-based annotation.. Our findings are comparable to leading international outcomes—for instance, a recent genome GS study reported a diagnostic yield of 61%, underscoring the value of comprehensive clinical assessment and reverse phenotyping [

16]. Notably, to our knowledge, no similar large-scale studies integrating structured phenotyping and genomic diagnostics have been conducted in Central Asia, highlighting the novelty and regional significance of our work.

All patients in our cohort underwent systematic deep phenotyping, including thorough medical history, neurological examination, and standardized documentation using HPO. This structured approach enabled precise alignment between clinical manifestations and ES results. Reverse phenotyping further uncovered previously unrecognized features in a substantial subset of patients, thereby strengthening genotype–phenotype correlations. Such methodologies are increasingly endorsed in the current literature as effective strategies for interpreting VUS [

16].

From a healthcare delivery perspective, this integrated diagnostic model resulted in a marked reduction in the diagnostic odyssey. Prior to inclusion, the median duration of the diagnostic process was 72 months, with a median of 20 diagnostic procedures per patient. Following the implementation of our protocol, diagnoses were achieved within 4–5 months and required only two confirmatory investigations. These results align with global initiatives aimed at streamlining diagnostics for rare diseases. While genomic testing incurs initial costs, recent analyses show that early deployment of such technologies can substantially reduce cumulative diagnostic expenses [

17]. Our data reinforce this notion, demonstrating that a single, well-targeted sequencing test can replace years of fragmented, inconclusive diagnostics.

Beyond economic considerations, timely diagnosis confers significant intangible benefits—alleviating familial anxiety and enabling earlier clinical management. Thus, the integrated approach presented here not only enhances diagnostic efficacy but also supports the broader goal of sustainable healthcare by promoting more rational resource allocation and improving the lived experiences of affected families.

Comparison with other cohorts reveals that our diagnostic performance is consistent with or surpasses global benchmarks. The proportion of genetically confirmed diagnoses in neurodevelopmental disorders is reported to range between 30% and 50%, depending on clinical severity and sequencing methodology [

18]. Our study focused on patients with severe phenotypes—combinations of epilepsy, intellectual disability, and complex syndromic features—many of which are known to be monogenic, likely contributing to the high diagnostic yield.

Our findings illustrate a broad genetic spectrum, including well-established pathogenic variants (e.g., RAI1 in Smith–Magenis syndrome, KCNQ2 in early infantile epileptic encephalopathy) and less characterized gene-disease associations (e.g., a novel KDM6B variant likely linked to developmental delay). Notably, several molecular diagnoses diverged from the initial clinical hypotheses, highlighting the diagnostic value of ES in cases with atypical or overlapping phenotypes.

Despite methodological similarities to prior studies, our work is unique in its demonstration of a structured integration of deep and reverse phenotyping into routine clinical pathways in a resource-limited region, offering a reproducible model for other low-resource healthcare systems.

Despite these strengths, our study has several limitations. Approximately 47% of cases remained without a molecular diagnosis. This may be partly attributed to the inherent limitations of ES, which does not provide full coverage of the genome and may miss pathogenic variants in deep intronic regions or structural rearrangements. However, other pathogenic mechanisms—such as repeat expansions, epigenetic modifications, and somatic mosaicism—are also likely contributors and are poorly detected even by genome GS. Emerging technologies such as methylation profiling, long-read sequencing, and single-cell approaches may help close this diagnostic gap in the future. While GS is increasingly adopted in high-income countries as a first-line diagnostic tool, neither GS nor ES are routinely available in many low- and middle-income regions due to the absence of local infrastructure and accredited sequencing facilities. In such contexts, genomic analyses must be outsourced to international laboratories. Among these options, ES remains relatively more accessible owing to its lower cost, making it the more practical choice for genomic diagnostics in resource-limited settings. Second, although VUS re-evaluation was supported by reverse phenotyping and multidisciplinary discussion, confirmatory functional studies were not performed, and formal reclassification under ACMG guidelines was not feasible within the study period. Third, segregation analysis—which could significantly aid in variant interpretation—was not systematically conducted and should be incorporated into future diagnostic workflows.

In light of these limitations, we plan to expand our diagnostic platform to include GS, chromosomal microarray analysis for copy number variants, epigenetic testing, long-read sequencing, and functional validation studies. These efforts aim to increase diagnostic yield among currently undiagnosed patients and to further refine genotype-phenotype relationships.

5. Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is one of the first multi-center studies in Central Asia to demonstrate the successful integration of deep phenotyping and advanced genomic diagnostics in pediatric neurology. Unlike isolated case reports, we present a reproducible and scalable model built on interdisciplinary collaboration, standardized clinical data collection, phenotype-driven variant prioritization, and reverse phenotyping. This diagnostic framework can serve as a prototype for establishing rare disease centers in other resource-limited settings.

In settings where families affected by rare disorders face significant emotional and financial strain, shortening the diagnostic journey from years to months represents a major advancement in care. Our findings not only validate a practical diagnostic approach but also emphasize the need for continued genomic innovation in unresolved cases. Early, accurate diagnosis enables targeted management, improves outcomes, and aligns with the principles of sustainable healthcare.

In conclusion, the integration of deep phenotyping, first-line ES, and reverse phenotyping in children with rare neurological disorders yielded a high diagnostic rate (53%), well above conventional methods. This approach drastically reduced diagnostic delays and minimized unnecessary investigations, improving both patient quality of life and healthcare system efficiency. Our results support the incorporation of this model into routine practice and advocate for the broader adoption of genomics-informed, resource-conscious diagnostic strategies in pediatric neurology

6. Patents

This work resulted in the development of a diagnostic algorithm for complex neurological phenotypes using deep phenotyping methods. The algorithm is registered as a scientific intellectual property object with the Copyright Certificate No. 56915, issued on April 17, 2025, by the Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions. Conceptualization, N.Y. and R.K.; methodology, N.Y., R.K. and N.Zh.; software, R.K.; validation, N.Zh. and R.K.; formal analysis, N.Y. and A.O.; investigation, N.Y. and R.K.; resources, N.Zh. and G.N.; data curation, N.Y. and A.O.; writing—original draft preparation, N.Y. and S.A.; writing—review and editing, N.Y., S.A. and R.K.; visualization, N.Y. and G.N.; supervision, N.Zh. and R.K.; project administration, A.O.; funding acquisition, R.K., G.N. and A.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by 3Billion Inc. (South Korea), the Central Asian and Transcaucasian Rare Pediatric Neurological Diseases Genomic Consortium. (

https://www.cat-genomics.com/), and the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. BR24992814).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Khoja Akhmet Yassawi International Kazakh-Turkish University (Protocol №16, dated June 8, 2023). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision), the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and national regulations governing research involving minors.

Informed Consent Statement

Prior to inclusion in the study, all participants and their legal guardians were thoroughly informed—both verbally and in writing—about the objectives, procedures, potential risks and benefits of the research, as well as the possibility of publication of anonymized clinical and genetic data. Written informed consent for participation and publication was obtained from all legal guardians. When appropriate, verbal and written assent was also obtained from the minor participants in accordance with their age and level of understanding.

Data Availability Statement

De-identified clinical and genomic datasets generated during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to ethical and institutional review board approval.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all the families who participated in this study for their trust, time, and cooperation. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of pediatricians, pediatric neurologists, and clinical specialists involved in patient evaluation, recruitment, and phenotypic data collection.

We thank 3Billion Inc. (South Korea) for providing ES services and variant interpretation. We also acknowledge the collaborative and scientific support of the Central Asian and Transcaucasian Rare Pediatric Neurological Diseases Genomic Consortium. (CAT-RPND), coordinated by the UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology (London, UK). We are grateful to the South Kazakhstan Medical Academy (Shymkent, Kazakhstan) for administrative and logistical support, including documentation and international transport of biological samples. The authors thank the Khoja Akhmet Yassawi International Kazakh-Turkish University for its institutional support throughout the study. Finally, we acknowledge the Clinical and Diagnostic Center of Khoja Akhmet Yassawi International Kazakh-Turkish University (Turkestan, Kazakhstan) for providing facilities for clinical assessments, patient visits, and biological sample collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACMG |

American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics |

| CAT-RPND |

Central Asia and Transcaucasia Rare Pediatric Neurological Diseases Genomic Consortium |

| GMFCS |

Gross Motor Function Classification System |

| CNV |

Copy Number Variations |

| DEE |

Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy |

| ES |

Exome Sequencing |

| GS |

Genome Sequencing |

| HPO |

Human Phenotype Ontology |

| NGS |

Next-Generation Sequencing |

| NORD |

National Organisation for Rare Disorders |

| RPND |

Rare Paediatric Neurological Diseases |

| SDG |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| SNV |

Single Nucleotide Variants |

| VUS |

Variant of uncertain significance |

References

- Ferreira CR. The burden of rare diseases. Am J Med Genet A. 2019 Jun;179(6):885-892. [CrossRef]

- Stark Z, Tan TY, Chong B et al. A prospective evaluation of whole-exome sequencing as a first-tier molecular test in infants with suspected monogenic disorders. Genet Med. 2016 Nov;18(11):1090-1096. [CrossRef]

- Makarova EV, Krysanov IS, Valilyeva TP, Vasiliev MD, Zinchenko RA. Evaluation of orphan diseases global burden. Eur J Transl Myol. 2021 May 14;31(2):9610. [CrossRef]

- Köhler S, Schulz MH, Krawitz P et al. Clinical diagnostics in human genetics with semantic similarity searches in ontologies. Am J Hum Genet. 2009 Oct;85(4):457-64. [CrossRef]

- Robinson PN. Deep phenotyping for precision medicine. Hum Mutat. 2012 May;33(5):777-80. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Muzny DM, Reid JG et al. Clinical whole-exome sequencing for the diagnosis of mendelian disorders. N Engl J Med. 2013 Oct 17;369(16):1502-11. Epub 2013 Oct 2. [CrossRef]

- Kaiyrzhanov R, Zharkinbekova N, Guliyeva U et al. Elucidating the genomic basis of rare pediatric neurological diseases in Central Asia and Transcaucasia. Nat Genet. 2024 Dec;56(12):2582-2584. PMID: 39578646. [CrossRef]

- Strong K, Noor A, Aponte J et al. Monitoring the status of selected health related sustainable development goals: methods and projections to 2030. Glob Health Action. 2020 Dec 31;13(1):1846903. [CrossRef]

- Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S et al.; ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015 May;17(5):405-24. [CrossRef]

- Kernohan KD, Boycott KM. The expanding diagnostic toolbox for rare genetic diseases. Nat Rev Genet. 2024 Jun;25(6):401-415. [CrossRef]

- Seo GH, Kim T, Choi IH et al. Diagnostic yield and clinical utility of whole exome sequencing using an automated variant prioritization system, EVIDENCE. Clin Genet. 2020 Dec;98(6):562-570. [CrossRef]

- Wilczewski CM, Obasohan J, Paschall JE et al. Genotype first: Clinical genomics research through a reverse phenotyping approach. Am J Hum Genet. 2023 Jan 5;110(1):3-12. [CrossRef]

- Capkova Z, Capkova P, Srovnal J, Adamova K, Prochazka M, Hajduch M. Duplication of 9p24.3 in three unrelated patients and their phenotypes, considering affected genes, and similar recurrent variants. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2021 Mar;9(3):e1592. [CrossRef]

- Glessner JT, Li J, Wang D et al. Copy number variation meta-analysis reveals a novel duplication at 9p24 associated with multiple neurodevelopmental disorders. Genome Med. 2017 Nov 30;9(1):106. [CrossRef]

- Guilherme RS, Meloni VA, Perez et al. AB Duplication 9p and their implication to phenotype. BMC Med Genet. 2014 Dec 20;15:142. [CrossRef]

- Akgun-Dogan O, Tuc Bengur E, Ay B et al. Impact of deep phenotyping: high diagnostic yield in a diverse pediatric population of 172 patients through clinical whole-genome sequencing at a single center. Front Genet. 2024 Mar 15;15:1347474. [CrossRef]

- Runheim H, Pettersson M, Hammarsjö A et al. The cost-effectiveness of whole genome sequencing in neurodevelopmental disorders. Sci Rep. 2023 Apr 27;13(1):6904. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Tang X, Yang K, Huo X, Zhang H, Ding K, Liao S. Deep phenotyping and whole-exome sequencing improved the diagnostic yield for nuclear pedigrees with neurodevelopmental disorders. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2022 May;10(5):e1918. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).