Submitted:

02 December 2024

Posted:

04 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Recruitment and Sampling

2.2. Review of Medical Records

2.3. Sampling, Sequencing, Bioinformatics Processing and Variant Filtering

2.4. Classification and Ontology Analysis of Associated Genes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

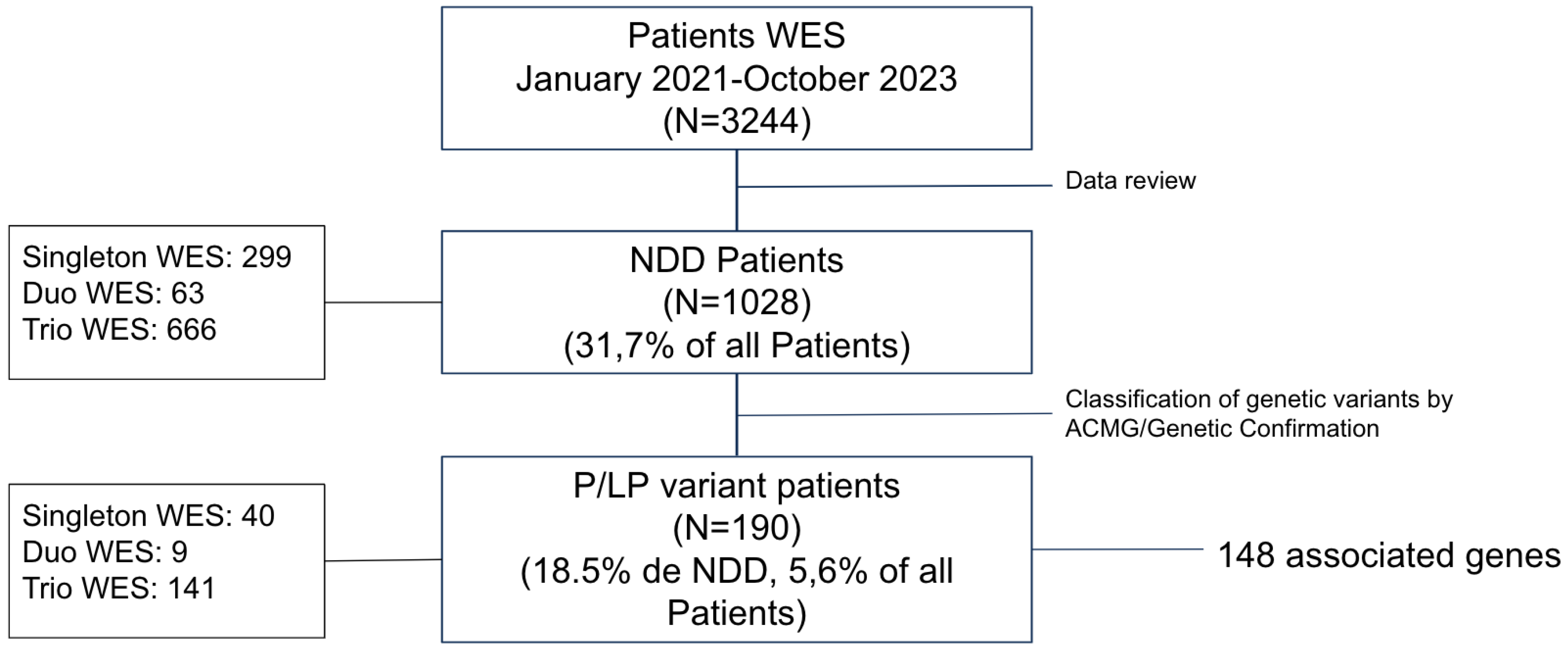

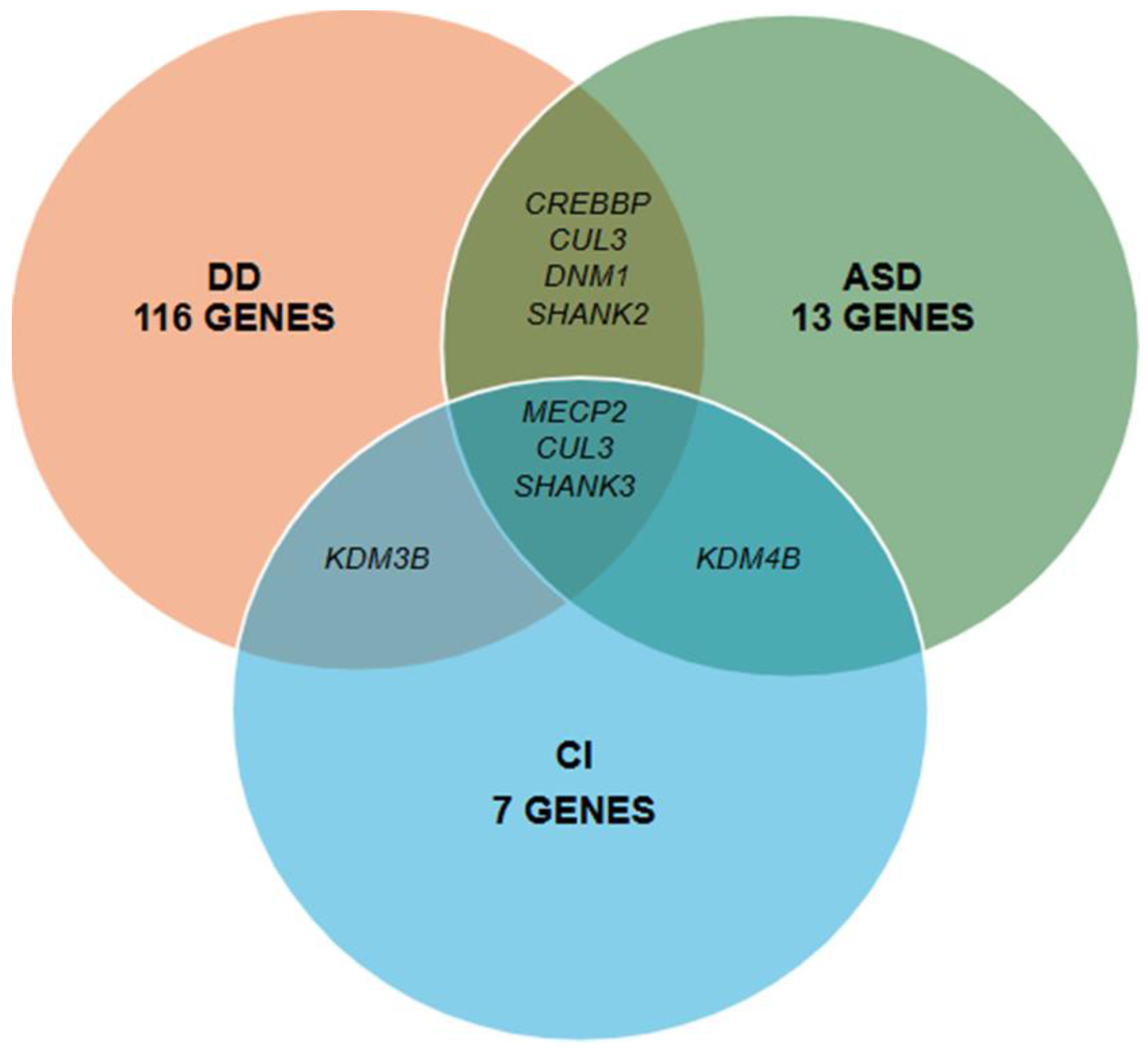

3.1. Diagnostic Yield

3.2. Characterization of Novel Variants

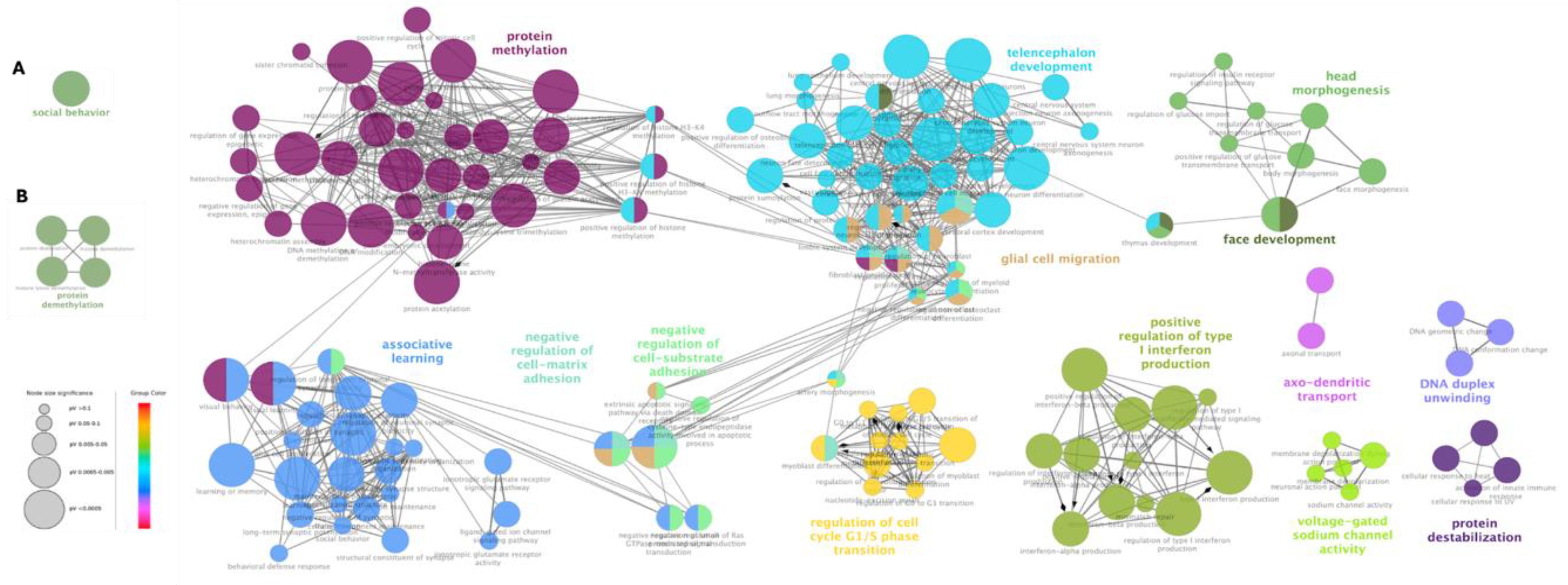

3.3. Gene Ontology Analysis

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Gidziela, A., Ahmadzadeh, Y. I., Michelini, G., Allegrini, A. G., Agnew-Blais, J., Lau, L. Y., Duret, M., Procopio, F., Daly, E., Ronald, A., Rimfeld, K., & Malanchini, M. A meta-analysis of genetic effects associated with neurodevelopmental disorders and co-occurring conditions. Nature Human Behaviour. 2023; 7(4), 642–656. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S., Love-Nichols, J. A., Dies, K. A., Ledbetter, D. H., Martin, C. L., Chung, W. K., Firth, H. v, Frazier, T., Hansen, R. L., Prock, L., Brunner, H., Hoang, N., Scherer, S. W., Sahin, M., & Miller, D. T. Meta-analysis and multidisciplinary consensus statement: exome sequencing is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders and the NDD Exome Scoping Review Work Group. Genetics in Medicine. 2019; 21, 2413–2421. [CrossRef]

- Hu, W. F., Chahrour, M. H., & Walsh, C. A. The diverse genetic landscape of neurodevelopmental disorders. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 2014; 15, 195–213. [CrossRef]

- Wayhelova, M., Vallova, V., Broz, P. et al. Exome sequencing improves the molecular diagnostics of paediatric unexplained neurodevelopmental disorders. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2024; 19, 41. [CrossRef]

- Satterstrom, F. K., Kosmicki, J. A., Wang, J., Breen, M. S., de Rubeis, S., An, J. Y., Peng, M., Collins, R., Grove, J., Klei, L., Stevens, C., Reichert, J., Mulhern, M. S., Artomov, M., Gerges, S., Sheppard, B., Xu, X., Bhaduri, A., Norman, U., … Buxbaum, J. D. Large-Scale Exome Sequencing Study Implicates Both Developmental and Functional Changes in the Neurobiology of Autism. Cell. 2020; 180(3), 568-584.e23. [CrossRef]

- Griffin A, Mahesh A, Tiwari VK. Disruption of the gene regulatory programme in neurodevelopmental disorders. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech. 2022 Oct;1865(7):194860. [CrossRef]

- Ballesta-Martínez, M.J., Pérez-Fernández, V., López-González, V. et al. Validation of clinical exome sequencing in the diagnostic procedure of patients with intellectual disability in clinical practice. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2023; 18, 201. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Granero, F., Blanco-Kelly, F., Sanchez-Jimeno, C. et al. Comparison of the diagnostic yield of aCGH and genome-wide sequencing across different neurodevelopmental disorders. npj Genom. Med. 2021; 6, 25. [CrossRef]

- Monroe GR, Frederix GW, Savelberg SM, de Vries TI, Duran KJ, et al. Effectiveness of whole-exome sequencing and costs of the traditional diagnostic trajectory in children with intellectual disability. Genet Med. 2016; 18:949–56. [CrossRef]

- Vrijenhoek T, Middelburg EM, Monroe GR, van Gassen KL, Geenen JW, Hövels AM, Knoers NV, van Amstel HK, Frederix GW. Whole-exome sequencing in intellectual disability; cost before and after a diagnosis. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2018; Nov;26(11):1566-71.

- Savatt JM, Myers SM. Genetic testing in neurodevelopmental disorders. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 2021; 19;9:526779.

- Zhou, X., Feliciano, P., Shu, C., Wang, T., Astrovskaya, I., Hall, J. B., Obiajulu, J. U., Wright, J. R., Murali, S. C., Xu, S. X., Brueggeman, L., Thomas, T. R., Marchenko, O., Fleisch, C., Barns, S. D., Snyder, L. A. G., Han, B., Chang, T. S., Turner, T. N., … Chung, W. K. Integrating de novo and inherited variants in 42,607 autism cases identifies mutations in new moderate-risk genes. Nature Genetics. 2022; 54(9), 1305–1319. [CrossRef]

- Servetti M, Pisciotta L, Tassano E, Cerminara M, Nobili L, Boeri S, Rosti G, Lerone M, Divizia MT, Ronchetto P, Puliti A. Neurodevelopmental disorders in patients with complex phenotypes and potential complex genetic basis involving non-coding genes, and double CNVs. Frontiers in Genetics. 2021; 21;12:732002. [CrossRef]

- Leite AJ, Pinto IP, Leijsten N, Ruiterkamp-Versteeg M, Pfundt R, de Leeuw N, da Cruz AD, Minasi LB. Diagnostic yield of patients with undiagnosed intellectual disability, global developmental delay and multiples congenital anomalies using karyotype, microarray analysis, whole exome sequencing from Central Brazil. PLoS One. 2022; 7;17(4):e0266493.

- Charouf, D., Miller, D., Haddad, L., White, F. A., Boustany, R.-M., & Obeid, M. High Diagnostic Yield and Clinical Utility of Next-Generation Sequencing in Children with Epilepsy and Neurodevelopmental Delays: A Retrospective Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(17), 9645. [CrossRef]

- Vissers, L., Gilissen, C. & Veltman, J. Genetic studies in intellectual disability and related disorders. Nat Rev Genet. 2016; 17, 9–18. [CrossRef]

- Wilfert, A.B., Sulovari, A., Turner, T.N. et al. Recurrent de novo mutations in neurodevelopmental disorders: properties and clinical implications. Genome Med. 2017; 9, 101. [CrossRef]

- Vanderhaeghen, P., Polleux, F. Developmental mechanisms underlying the evolution of human cortical circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2023; 24, 213–232. [CrossRef]

- Swanberg SE, Nagarajan RP, Peddada S, Yasui DH, LaSalle JM. Reciprocal co-regulation of EGR2 and MECP2 is disrupted in Rett syndrome and autism. Human Molecular Genetics. 2009; 1;18(3):525-34. [CrossRef]

- Fischer S, Schlotthauer I, Kizner V, Macartney T, Dorner-Ciossek C, Gillardon F. Loss-of-function Mutations of CUL3, a High Confidence Gene for Psychiatric Disorders, Lead to Aberrant Neurodevelopment In Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Neuroscience. 2020; 10;448:234-254. [CrossRef]

- Bruno, L. P., Doddato, G., Valentino, F., Baldassarri, M., Tita, R., Fallerini, C., Bruttini, M., Rizzo, C. lo, Mencarelli, M. A., Mari, F., Pinto, A. M., Fava, F., Fabbiani, A., Lamacchia, V., Carrer, A., Caputo, V., Granata, S., Benetti, E., Zguro, K., … Ariani, F.. New candidates for autism/intellectual disability identified by whole-exome sequencing. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(24). [CrossRef]

- Heiman P, Drewes S, Ghaloul-Gonzalez L. A familial case of CAMK2B mutation with variable expressivity. SAGE Open Medical Case Reports. 2021 Feb;9:2050313X21990982.

- Jin C, Zhang X, Lei Q, Chen P, Hu H, Shen S, Liu J and Ye S. Case report: genetic analysis of a novel frameshift mutation in FMR1 gene in a Chinese family. Front. Genet. 2023; 14:1228682. [CrossRef]

- Pande, S., Majethia, P., Nair, K. et al. De novo variants underlying monogenic syndromes with intellectual disability in a neurodevelopmental cohort from India. Eur J Hum Genet. 2024; 32, 1291–1298. [CrossRef]

- Lin P, Yang J, Wu S, Ye T, Zhuang W, Wang W, Tan T. Current trends of high-risk gene Cul3 in neurodevelopmental disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2023; 28;14:1215110. [CrossRef]

- Uchino S, Waga C. SHANK3 as an autism spectrum disorder-associated gene. Brain Dev. 2013; 35(2):106-10. [CrossRef]

| Phenotype | Gene |

|---|---|

| Developmental Delay | ACTL6B, AHDC1, ANKRD11, ARID2, ATRX, BCL11A, BCL11B, BRAF, CHD3, CREBBP, CTNNB1, CUL3, DDX3X, DNM1, DNMT3A, DPYD, DYNC1H1, FBXO11, FLNB, FOXG1, GLUD2, GNB1, GRIA2, GRIN1, H1-4, IFIH1, INTS1, IVD, JAG1, KCNT2, KDM6B, KIAA1109, KIF1A, KMT2A, KMT2C, LARP7, LARS2, LMAN2L, LZTR1, MECP2, MN1, MSTO1, NACC1, NALCN, NARS, NEXMIF, NF1, NFIB, PHF8, PIK3R1, PPM1D, PTPN11, PURA, QRICH1, RAF1, RAI1, RBMX, RPS6KA3, SATB2, SCN1A, SCN2A, SCN8A, SETD2, SETD5, SHANK2, SHANK3, SIX3, SLC13A5, SPEN, STAG2, SYNGAP1, TAOK1, TBK1, TBR1, TCF20, TCF4, TOE1, TREX1, TRIP12, TSC2, TSPAN7, TUBB, UBTF, USP7, WAC, ZMIZ1, AP1S2, ARSA, CAPN3, CDC42, COL6A2, COL6A3, CTBP1, DCX, DHTKD1, EP300, FBN2, GCDH, PMM2, POLR3B, PUF60, RTN2, RYR1, SPG11, SPG7, SPTBN2, TNPO3, TRPV4, TRIO, RNASEH2B, RFX7, KMT2E, ATP7B, ARID1B, INPP5E, KDM3B, CSNK2A1 |

| Developmental Delay & Epilepsy | ABCC8, AFF3, ANKRD17, CDKL5, CHD2, GNAO1, GRIN2B, HNRNPU, KAT6A, KCNB1, KCNMA1, PTCH1, SETD1A, SLC2A1, STXBP1, MN1 |

| Autism Spectrum Disorder | CACNA1E, CAMK2A, CHD8, CPT2, CREBBP, CSF1R, CUL3, DNM1, EBF3, KDM4B, PTEN, SHANK2, SHANK3 |

| Cognitive impairment | KDM4B, KDM5C, KDM6A, PAX8, NAA15, KDM3B, SHANK3 |

| Gene* | DNA | Protein | Variant Type | ACMG Classification | Transcripts | OMIM code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTL6B | c.521_522insA | p.Thr175Hisfs*7 | Frameshift | LP | NM_016188.4 | 612458 |

| ACTL6B* | c.991G>A | p.Gly331Ser | Missense | LP | NM_016188.5 | 612458 |

| AHDC1 | c.4294del | p.Ala1432Profs*13 | Frameshift | LP | NM_001371928.1 | 615790 |

| ANKRD11 | c.741C>A | p.Tyr247* | Nonsense | LP | NM_013275.6 | 611192 |

| ANKRD11* | c.7124_7152del | p.Glu2375Alafs*147 | Frameshift | P | NM_013275.5 | 611192 |

| ANKRD17* | c.4453_4457del | p.Lys1485Glufs*17 | Frameshift | P | NM_032217.4 | 615929 |

| AP1S2 | c.180-1G>C | Splicing site | LP | NM_001272071.2 | 300629 | |

| BCL11B* | c.2345dup | p.Gly785Argfs*100 | Frameshift | P | NM_138576.3 | 606558 |

| BRAF* | c.2030A>G | p.Asp677Gly | Missense | P | NM_004333.6 | 164757 |

| CACNA1E* | c.5365-2A>G | - | Splicing site | LP | NM_001205293.1 | 601013 |

| CHD2* | c.2822A>T | p.Gln941Leu | Missense | LP | NM_001271.4 | 602119 |

| CHD3 | c.3481C>T | p.His1161Tyr | Missense | LP | NM_001005273.3 | 7806365 |

| CHD8* | c.4987_5003del | p.Val1663Glnfs*59 | Frameshift | P | NM_020920.4 | 610528 |

| COL6A3* | c.6156+2T>C | - | Splicing site | P | NM_004369.4 | 120250 |

| COL9A3 | c.1021C>T | p.Arg341* | Nonsense | LP | NM_001853.4 | 120270 |

| CUL3* | c.769delG | p.Glu257Lysfs*5 | Frameshift | P | NM_003590 | 603136 |

| CUL3* | c.494dup | p.Leu166Ilefs*37 | Frameshift | P | NM_003590.4 | 603136 |

| DCX | c.166C>G | p.Arg56Gly | Missense | LP | NM_001195553.1 | 300121 |

| DDX3X | c.1646A>T | p.Asn549Ile | Missense | LP | NM_001356.4 | 300160 |

| DNM1* | c.1751A>T | p.His584Leu | Missense | LP | NM_004408.4 | 602377 |

| DNM1* | c.2318+2T>C | - | Splicing site | P | NM_004408.4 | 602377 |

| DYNC1H1* | c.11632C>G | p.Gln3878Glu | Missense | LP | NM_001376.5 | 600112 |

| EP300* | c.4779+1G>A | - | Splicing site | P | NM_001429.3 | 602700 |

| FBXO11* | c.1685A>G | p.Tyr562Cys | Missense | LP | NM_025133.4 | 607871 |

| GNB1* | c.310G>C | p.Ala104Pro | Missense | LP | NM_002074.5 | 139380 |

| GRIN1* | c.2248G>A | p.Gly750Arg | Missense | LP | NM_000832.7 | 138249 |

| GRIN1* | c.1824G>C | p.Trp608Cys | Missense | P | NM_007327.3 | 138249 |

| GRIN2B* | c.1990T>C | p.Ser664Pro | Missense | LP | NM_000834.3 | 138252 |

| HNRNPU | c.1484_1487del | p.Lys495Ilefs*5 | Frameshift | LP | NM_031844.3 | 602869 |

| HNRNPU* | c.1576_1580del | p.Asn526Serfs*9 | Frameshift | P | NM_031844.2 | 602869 |

| IFIH1 | c.2863C>T | p.Gln955* | Nonsense | LP | NM_022168.3 | 606951 |

| JAG1 | c.1725_1726dupTG | p.Asp576Valfs*168 | Frameshift | LP | NM_000214.3 | 601920 |

| KAT6A* | c.1019del | p.Asn340Thrfs*3 | Frameshift | P | NM_006766.4 | 601408 |

| KAT6A* | c.4140_4141insA | p.Asp1381Argfs*13 | Frameshift | P | NM_006766.4 | 601408 |

| KCNB1* | c.1223C>T | p.Pro408Leu | Missense | LP | NM_004975.3 | 600397 |

| KCNB1* | c.1202G>T | p.Gly401Val | Missense | P | NM_004975.4 | 600397 |

| KCNMA1 | c.2095A>T | p.Lys699* | Nonsense | LP | NM_001161352.1 | 600150 |

| KCNT2 | c.3118C>T | p.Arg1040* | Nonsense | LP | NM_198503 | 610044 |

| KDM3B* | c.3638dup | p.(Asp1214Ter | Nonsense | LP | NM_016604.4 | 609373 |

| KDM4B | c.2147del | p.Leu716Tyrfs*42 | Frameshift | LP | NM_015015.2 | 609765 |

| KDM5C* | c.1571A>T | p.Asn524Ile | Missense | LP | NM_004187.5 | 314690 |

| KIAA1109 | c.4118_4119del | p.Ser1373* | Nonsense | LP | NM_015312.3 | 611565 |

| KIAA1109* | c.18T>A | p.Asn6Lys | Missense | LP | NM_015312.3 | 611565 |

| KIAA1109* | c.4118_4119del | p.Ser1373* | Nonsense | LP | NM_015312.3 | 611565 |

| KMT2A* | c.7187_7188del | p.Pro2396Argfs*2 | Frameshift | P | NM_001197104.2 | 159555 |

| KMT2C* | c.5551C>T | p.Gln1851* | Nonsense | P | NM_170606.2 | 606833 |

| KMT2E | c.1944_1948del | p.Lys649GlufsTer8 | Frameshift | LP | NM_182931.3 | 608444 |

| LARP7 | c.1118_1130del | p.Val373Glufs*11 | Frameshift | LP | NM_016648.4 | 612026 |

| LARS2* | c.1420del | p.Leu474Trpfs*6 | Frameshift | P | NM_015340.4 | 604544 |

| MN1 | c.97del | p.His33ThrfsTer20 | Frameshift | LP | NM_002430.3 | 156100 |

| NAA15* | c.2214del | p.Met738IlefsTer18 | Frameshift | P | NM_057175.5 | 608000 |

| NACC1* | c.166C>T | p.Arg56Trp | Missense | LP | NM_052876.3 | 610672 |

| NEXMIF | c.1998del | p.Glu667Lysfs*5 | Frameshift | LP | NM_001008537.2 | 300524 |

| NEXMIF | c.1998del | p.Glu667Lysfs*5 | Frameshift | LP | NM_001008537.3 | 300524 |

| NF1 | c.2056A>T | p.Lys686* | Nonsense | LP | NM_001042492.2 | 613113 |

| NFIB* | c.626A>G | p.Glu209Gly | Missense | LP | NM_001190737.3 | 600728 |

| NFIX* | c.442del | p.Ile148Serfs*71 | Frameshift | P | NM_001271043.2 | 164005 |

| LPM1D* | c.1245dupT | p.Thr416Tyrfs*18 | Frameshift | P | NM_003620.4 | 605100 |

| PUF60* | c.1334C>T | p.Thr445Ile | Missense | LP | NM_014281.5 | 604819 |

| RFX7* | c.2236C>T | p.Gln746* | Nonsense | P | NM_022841.7 | 612660 |

| RPS6KA3* | c.383C>T | p.Pro128Leu | Missense | LP | NM_004586.3 | 300075 |

| SATB2 | c.1165C>A | p.Arg389Ser | Missense | LP | NM_001172509.2 | 608148 |

| SCN1A* | c.4987G>T | p.Gly1663Cys | Missense | P | NM_006920.6 | 182389 |

| SCN1A* | c.4582-1_4583del | - | Splicing site | P | NM_001165963.4 | 182389 |

| SCN1A* | c.4987G>T | p.Gly1663Cys | Missense | P | NM_006920.6 | 182389 |

| SCN2A | c.641C>A | p.Ser214* | Nonsense | LP | NM_001040143.2 | 182390 |

| SCN8A* | c.5235C>A | p.Phe1745Leu | Missense | P | NM_001330260 | 600702 |

| SETD1A* | c.5116C>G | p.Leu1706Val | Missense | LP | NM_014712.3 | 611052 |

| SHANK3* | c.352dup | p.Leu118ProfsTer28 | Frameshift | P | NM_001372044.2 | 606230 |

| SIX3* | c.221del | p.Pro74Argfs*177 | Frameshift | P | NM_005413.4 | 603714 |

| SPEN* | c.5485_5486insTTTGAAC | p.Gln1829Leufs*2 | Frameshift | P | NM_015001.4 | 613484 |

| STAG2 | c.1018-2_1018-1delinsTT | - | Splicing site | LP | NM_001042750.2 | 300826 |

| STXBP1* | c.903-1G>C | - | Splicing site | P | NM_001032221.3 | 602926 |

| SYNGAP1* | c.1713_1714delinsAC | p.Trp572Arg | Missense | LP | NM_006772.2 | 603384 |

| SYNGAP1* | c.1216_1218delins | p.Tyr406Asnfs*4 | Frameshift | P | NM_006772 | 603384 |

| TAOK1 | c.1721dupA | p.Ser575Glufs*28 | Frameshift | LP | NM_020791 | 610266 |

| TAOK1 | c.1489_1492del | p.Asp497Lysfs*42 | Frameshift | LP | NM_020791.4 | 610266 |

| TBR1* | c.893dup | p.His298Glnfs*23 | Frameshift | P | NM_006593.3 | 604616 |

| TCF20* | c.5047_5054del | p.Pro1683Valfs*34 | Frameshift | P | NM_005650.3 | 603107 |

| TCF4 | c.-20-184_72+815del | - | Splicing site | LP | NM_001083962.2 | 602272 |

| TNPO3 | c.120+2T>G | - | Splicing site | LP | NM_012470.4 | 610032 |

| TRIP12 | c.3206+1G>T | - | Splicing site | LP | NM_001348323.3 | 604506 |

| TUBB* | c.1145C>T | p.Ser382Leu | Missense | LP | NM_178014.4 | 191130 |

| TUBB* | c.1017C>G | p.Ser339Arg | Missense | LP | NM_178014.4 | 191130 |

| USP7* | c.502T>C | p.Ser168Pro | Missense | LP | NM_003470.2 | 602519 |

| WAC* | c.620del | p.Lys207Serfs*124 | Frameshift | P | NM_016628.5 | 615049 |

| ZMIZ1* | c.1413+4A>G | - | Splicing site | LP | NM_020338.3 | 607159 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).