Submitted:

13 December 2023

Posted:

14 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

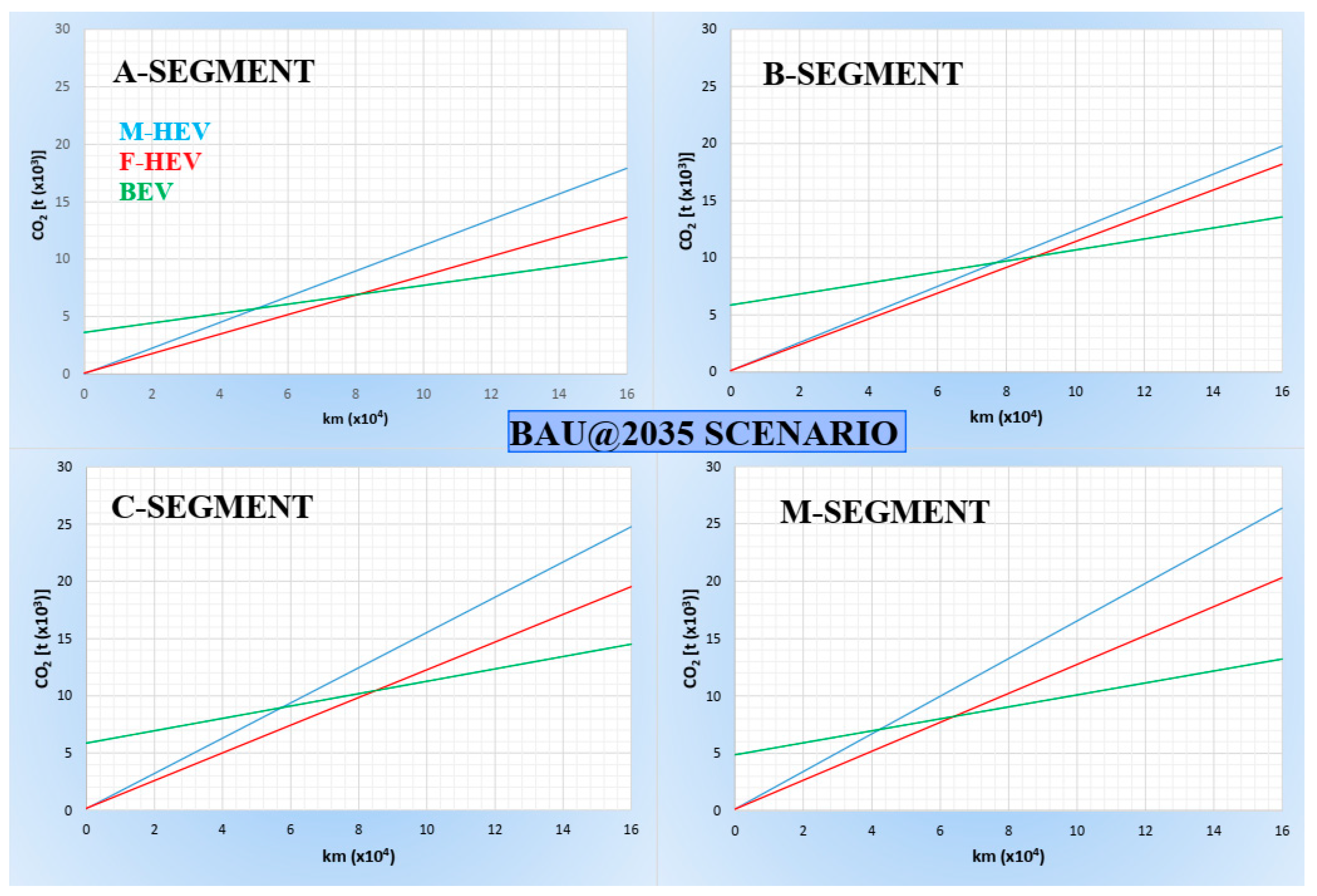

- the Business as Usual (BAU@2035) scenario (conservative), constructed considering a consolidated average growth rate (CAGR) of newly installed RES capacity over the period 2016-2021 until obtaining a total amount of RES in 2035;

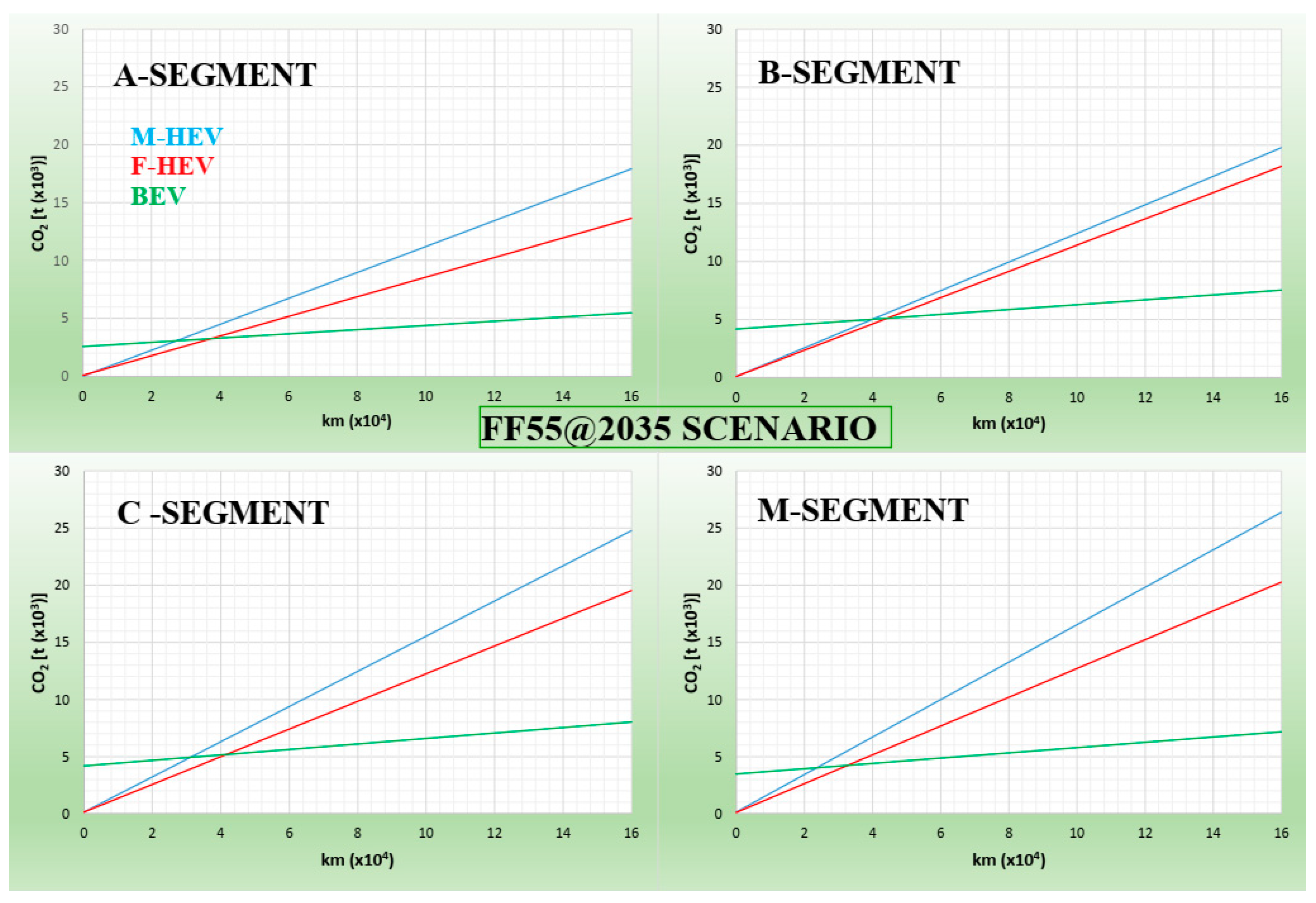

- the Fit for 55@2035 (FF55@2035) scenario (binding), constructed taking into account the same growth rate of newly installed RES capacity as stated to fulfil the Fit for 55 package objectives by 2030 until obtaining a total amount of RES in 2035

3. Results

3.1. The Italian c.i. at 2021

- The primary fuel used and the thermodynamic cycle allowable by the fuel.

- The contribution of RES, whose total incidence varies according to the season and to the different weather conditions;

- The net energy flux imported and exported through the international exchange;

3.2. The Italian c.i. at 2035

3.3. The carbon footprint related to the battery production (c.i.b)

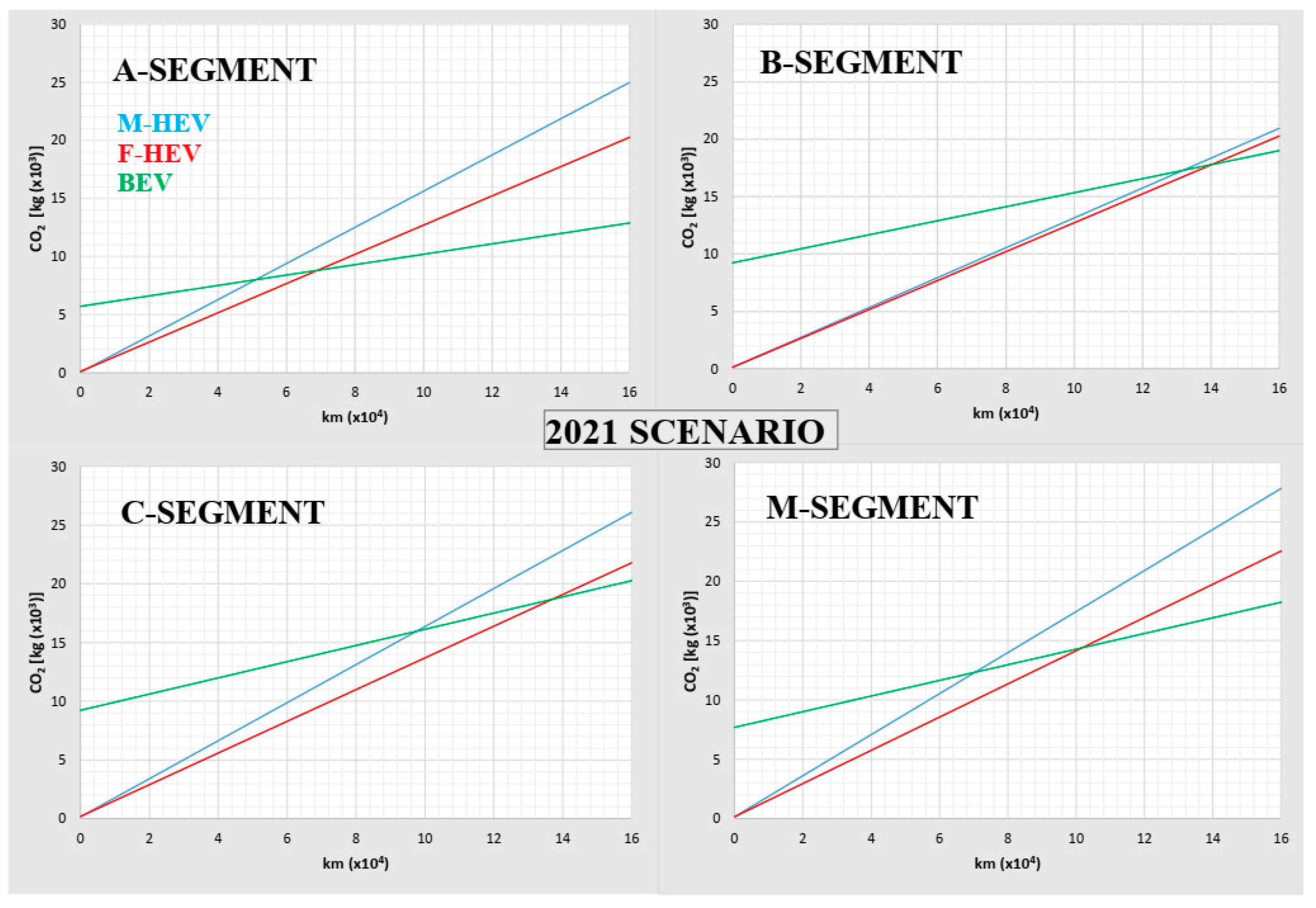

3.4. The c.i. of the vehicles’ use-phase

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdul-Manan A.F.N., Zavaleta V.G., Agarwal A.K., Kalghatgi G., Amer. A.A. Electrifying passenger road transport in India requires near-term electricity grid decarbonisation. Nat Commun 13, 2022, 2095. [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. (2023) Shedding light on energy – 2023 edition. Luxembourg: Eurostat. Available online: (https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/interactive-publications/energy-2023 (accessed: 27 October 2023) .

- McBain, S. and Teter J. (2021) Tracking transport, 2021. Paris: IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/tracking-transport-2021 (accessed on 13 September 2023).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Data Browser. Available online: https://www.iea.org/countries/italy(accessed: 15 November 2023).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). (2020) Clean Energy Innovation. Paris: IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/clean-energy-innovation (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- The European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA). (2023) Vehicles in use, Europe. Brussels: ACEA. Available online: https://www.acea.auto/publication/report-vehicles-in-use-europe-2023/ (accessed on 04 October 2023).

- Woody M., Vaishan P., Keoleian G.A., De Kleine R., Kim H.C., Anderson J.E., Wallington T.J. The role of pickup truck electrification in the decarbonisation of light-duty vehicles. Environ. Res.Lett., 17(3), 2022, 034031. [CrossRef]

- The European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA). (2021) Fuel types of new cars: battery electric 9.1%, hybrid 19.6% and petrol 40.0% market share full-year 2021. Brussels: ACEA. Available online: https://www.acea.auto/files/20220202_PRPC-fuel_Q4-2021_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2023).

- Xia X. and Li P. A review of the Life-cycle Assessment of electric vehicles: Considering the influence of batteries. Science of total environment 814, 2022, 152870. [CrossRef]

- Cox B., Bauer C., Beltran A. M., van Vuuren D.P, Mutel C.L. Life cycle environmental and cost comparison of current and future passenger cars under different energy scenarios. Applied Energy, 269, 2020, 115021. [CrossRef]

- Evrard E., Davis J., Hagdahl K.-H, Palm R., Lindholm J., Dahllöf L. (2021) Carbon footprint report – Volvo C40 Recharge. Goteborg: Volvo. Available online: https://www.volvocars.com/us/news/sustainability/Wanted-clean-energy-for-full-climate-benefits/ (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Helmers, E. , Johannes D., Weiss M. Sensitivity Analysis in the Life-Cycle Assessment of Electric vs. Combustion Engine Cars under Approximate Real-World Conditions. Sustainability, 12, 2020, 1241. [CrossRef]

- Emilsson E., Dahllof. L. (2019) Lithium-ion Vehicle Battery Production, Status 2019 on Energy use, CO2 emissions, use of metals, Products Environmental Footprint, and Recycling. Stockholm: IVL. Available online: https://www.ivl.se/download/18.14d7b12e16e3c5c36271070/1574923989017/C444.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- European Council (EU). Fit for 55. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/green-deal/fit-for-55-the-eu-plan-for-a-green-transition/(accessed 1May 2023).

- European Parliament, Council of the European Union. REGULATION (EU) 2023/1542 of the European Parliament and of the council of 12 July 2023 concerning batteries and waste batteries, amending Directive 2008/98/EC and Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 and repealing Directive 2006/66/EC. Official Journal of the European Union, 2023, 66. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/1542/oj.

- Northvolt. (2023) Sustainability and annual report, 2022. Stockholm: Northvolt. Available online: https://northvolt.com/environment/report2022/(Accessed: 01 November 2023).

- UNRAE per Quattroruote. (2022) L’automobile: Italiani a Confronto. Roma: UNRAE. Available online: https://unrae.it/files/Studio%20UNRAE%20L_automobile%20Italiani%20a%20confronto_6336ab4170253.pdf(Accessed: 15 October 2023).

- Islam, E. , Vijayagopal R., Moawad A., Kim N., Dupont B., Prada D.N., Rousseau A. A detailed vehicle modeling & simulation study quantifying energy consumption and cost reduction of advanced vehicle technology through 2050. United States. [CrossRef]

- Capaldi P. and Grimaldi F.M. The effectiveness of ICEV phase-out at 2035 in terms of CO2 emission reduction in the Italian scenario. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Energy Harvesting, Storage, and Transfer (EHST’22). Niagara Falls, Canada – June 08-10, 2022. Available online: https://avestia.com/EHST2022_Proceedings/files/paper/EHST_146.pdf.

- Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Electricity Generation: Update. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy21osti/80580.pdf(Accessed: 10 October 2023).

- Ministero della Transizione Ecologica – Dip.Energia – Direzione generale infrastrutture e sicurezza. La situazione energetica nazionale nel 2021. Italy. Available online: https://dgsaie.mise.gov.it/pub/sen/relazioni/relazione_annuale_situazione_energya_nazionale_dati_2021.pdf.

- Federazione ANIE. Sala Stampa – Comunicati stampa. Osservatorio FER. Available online: https://anie.it/sala-stampa/comunicati-stampa/(10 October 2023).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). (2023) Italy 2023 – Energy Policy Review. Paris: IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/italy-2023(Accessed 27 October 2023).

- Terna – Snam. (2022) Documento di descrizione degli scenari 2022. Roma: Terna/Snam. Available online: https://www.terna.it/it/sistema-elettrico/rete/piano-sviluppo-rete/scenari (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- EMBER. European Union – The EU accelerates electricity transition in the wake of crisis. Explore open data (Emissions intensity). Available online: https://ember-climate.org/countries-and-regions/regions/european-union/(Accessed 02 October 2023).

- Terna. (2021) Evoluzione Rinnovabile 2021. Roma: Terna. Available online: https://download.terna.it/terna/Evoluzione_Rinnovabile_8d940b10dc3be39.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Teske, S.; , Morris T., Nagrath K. (2020) 100% Renewable Energy: An Energy [R] evolution for ITALY. Report prepared by ISF for Greenpeace Italy. Available online: https://www.uts.edu.au/sites/default/files/article/downloads/100-Percent-Renewable-Energy-Italy-report.pdf(accessed 1May 2023).

- Federazione ANIE. Sala Stampa – Comunicati stampa. Osservatorio FER. Available online: https://anie.it/sala-stampa/comunicati-stampa/(15 October 2023).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). (2023) Electricity Grids and Secure Energy Transition. Paris: IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/electricity-grids-and-secure-energy-transitions (accessed on 21 October 2023).

- The international EPD system. Documentation overview for EPD and PCR. Available online: https://environdec.com/resources/documentation#generalprogrammeinstructions (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Spritmonitor.de. MPG and Cost Calculator and Tracker. Available online: https://www.spritmonitor.de/en/ (accessed on 21 October 2023).

- ADAC, Elektroautos im Test: So hoch ist die Reichweite wirklich. Available online: https://www.adac.de/rund-ums-fahrzeug/elektromobilitaet/tests/stromverbrauch-elektroautos-adac-test/.

- Edwards, R.; , Larivé J.-F., Rickeard D., Weindorf W. (2014) JEC, Well-to-Wheels analysis, Well-to-wheels analysis of future automotive fuels and powertrains in the European context”, Concawe-EUCAR-JRC. Bruxelles: JRC. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC85326/wtt_report_v4a_april2014_pubsy.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Argonne National Laboratory. Energy Systems and Infrastructure Analysis, GREET Model – The Greenhouse gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy use in Technologies Model. Available online: https://greet.es.anl.gov/(Accessed: 01 October 2023).

- Reick B., Konzept A., Kaufmann A., Stetter R., Engelmann, D. Influence of charging losses on energy consumption and CO2 emissions of battery-electric vehicles. Vehicles, 3(4), 2021, 736-748. [CrossRef]

- Genovese, A. , Ortenzi F., & Villante, C. On the energy efficiency of quick DC vehicle battery charging. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 7(4), 2015, 570-576. [CrossRef]

| Car segment | Powertrain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild HEV |

Full HEV |

BEV | |||

| A | Suzuki Ignis | Honda Jazz | VW UP | ||

| B | Mazda 2 | Toyota Yaris | Nissan Leaf | ||

| C | Ford Kuga | Hyundai Ioniq | Tesla Mod.3 | ||

| M | Suzuki Vitara | VW Tiguan | Opel Mokka | ||

| NG | OTHER NON- RES |

HYDRO | PV | WIND | OTHER RES | CURTAILMENT/ LOSSES |

Net I/E | c.i.e | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 140 | 22 | 47 | 25 | 21 | 23 | -1 | 43 | 293 |

| 2035 BAU | 155 | 7 | 51 | 35 | 30 | 23 | -4 | 53 | 249 |

| 2035 FF55 | 57 | 3 | 51 | 136 | 90 | 23 | -26 | 53 | 110 |

| Energy scenario | Electric C.I. (p.p.)1 |

Electric C.I. (m.v.)2 |

Electric C.I. (l.v.)3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 0.293 | 0.308 | 0.318 |

| 2035 BAU | 0.249 | 0.262 | 0.270 |

| 2035 FF55 | 0.110 | 0.116 | 0.120 |

| Authors | CO2 specific emissions related to the battery cell (kgCO2/kWh) |

CO2e emissions related to mining and refining processes (kgCO2/kWh) |

CO2e emissions from scrap materials (kgCO2/kWh) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cox et Al. (2017) [10] | 100 | N.C.1 | N.C. |

| IVL (2019) [13] | 80 | N.C. | N.C. |

| Helmers et Al. (2020) [12] | 90 | N.C. | N.C. |

| Woody et Al. (2021) [7] | 90 | N.C. | N.C. |

| Volvo2 (2021) [11] | 90 | 50 | 15 |

| Northvolt (2022) [16] | 1303 | // | // |

| Energy scenario | Electric C.I. (battery production plant) |

(a) CO2 for mining & refining |

(b) CO2 for battery cell production |

(c) CO2 for scrap materials production |

(d) CO2 for battery pack assembly |

(e) Total CO2 for battery pack Production |

(f) Total CO2 for enhanced battery @2035 (+ 20% energy) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 0.308 | 45 | 74 | 15 | 20 | 154 | // |

| 2035 BAU | 0.262 | 40 | 50 | 14 | 18 | 122 | 97 |

| 2035 FF55 | 0.116 | 40 | 23 | 10 | 14 | 87 | 70 |

| Energy Scenario |

C.I.E. @low voltage |

AC Charging phase efficiency |

C.I.C. @vehicle Battery (PTB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 0.318 | 0.85 | 0.374 |

| BAU@2035 | 0.270 | 0.88 | 0.307 |

| FF55@2035 | 0.120 | 0.88 | 0.137 |

| Mild HEV Car segment |

Model | Fuel consumption (dm3/km) |

WTW CO2 emissions (gCO2/km) |

Battery Capacity (kWh) |

CO2 for battery production (kgCO2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Suzuki Ignis | 0.054 | 151 | 0.13 | 20 |

| B | Mazda 2 | 0.046 | 129 | 0.90 | 138 |

| C | Ford Kuga | 0.058 | 162 | 1.20 | 185 |

| M | Suzuki Vitara | 0.062 | 174 | 1.10 | 169 |

|

Full HEV Car segment |

|||||

|

A B C M |

Honda Jazz | 0.046 | 129 | 0.75 | 115 |

| Toyota Yaris | 0.045 | 126 | 0.90 | 138 | |

| Hyundai Ioniq | 0.048 | 134 | 1.30 | 200 | |

| VW Tiguan | 0.050 | 140 | 1.20 | 185 | |

|

BEV Car segment |

Model |

Energy consumption (kWh/km) |

Plant-to-Wheel CO2 emissions (gCO2/km) |

Battery Capacity (kWh) |

Battery carbon Intensity (kgCO2) |

| A | VW UP | 0.141 | 45 | 37 | 5700 |

| B | Nissan Leaf | 0.162 | 51 | 60 | 9240 |

| C | Tesla Mod.3 | 0.184 | 59 | 60 | 9240 |

| M | Opel Mokka | 0.177 | 56 | 50 | 7700 |

| CAR SEGMENT |

POWERTRAIN | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEV | Full HEV |

Mild HEV |

BEV | Full HEV |

Mild HEV |

||

| Additional CO2 emissions for full lifespan @160.000 km |

Additional CO2 emissions for mean lifespan @120.000 km |

||||||

| 2021 | A | Ref. | +27% | +57% | Ref. | +27% | +57% |

| B | “ | +7% | +10% | “ | -8% | -5% | |

| C | “ | +7% | +29% | “ | -7% | +11% | |

| M | ” | +23% | +52% | ” | +8% | +33% | |

| BAU@2035 | A | “ | +59% | +109% | “ | +59% | +109% |

| B | “ | +34% | +45% | “ | +17% | +28% | |

| C | “ | +35% | +70% | “ | +18% | +49% | |

| M | “ | +53% | +100% | “ | +38% | +78% | |

|

FF55@ 2035 |

A | “ | +185% | +277% | “ | +185% | +277% |

| B | “ | +141% | +162% | “ | +102% | +122% | |

| C | “ | +143% | +208% | “ | +107% | +161% | |

| M | “ | +183% | +268% | “ | +145% | +219% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).