1. Introduction

Due to attached lifestyle, plants are constantly exposed to abiotic (drought, salinity, heat, cold, lack of nutrients, lack of light, high light intensity) and biotic (viruses, microorganisms, insects, herbivorous animals) environmental stressors [

1]. During evolution plants developed two main ways to coordinate generalized defense reactions: intercellular communication via plasmodesmata (PD) and signal transfer by emission and perception of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). PD serve for transport of various regulatory molecules including RNA and proteins in addition to low molecular weight compounds [

2]. PD permeability is under strict control and is regulated via several main mechanisms: (i) physical narrowing of the channel by callose depositions mediated by callose-degrading and callose synthesizing enzymes, (ii) regulation by various proteins associated and localized in PD, (iii) signals from mitochondria and chloroplasts that are transferred to the nucleus and affect expression of various genes encoding proteins the ensemble of which defines PD state [

3,

4,

5]. Therefore, PD regulation usually involves nucleus and nucleus-encoded genes. Pathogenic bacteria and viruses could interfere with plant immune response affecting nucleus and nucleocytoplasmic transport as well as PD and symplastic transport.

To realize intra- and interplant communication in the absence of physical contact, plants utilize VOCs [

6,

7]. In addition to simple molecules such as oxygen, carbon dioxide and water vapor, plants emit a huge amount of various complex compounds as terpenoids, derivatives of fatty acids and amino acids, benzoids, phenylpropanoids, etc. into the atmosphere [

8]. Gaseous methanol is a product of cell wall pectin demethylation by pectin methylesterase (PME) [

9,

10]. Methanol is one of the signal molecules that is emitted both in normal conditions [

11,

12] and in response to stress [

13,

14,

15]. It plays significant role in plant-herbivores [

16,

17] and plant-pathogen interactions [

18]. Methanol emitted by an injured plant triggers defense responses in both its own intact leaves and neighboring plants: it induces resistance to bacterial pathogens

Agrobacterium tumefaciens and

Ralstonia solanacearum [

18]. Moreover, it was shown that transgenic plants with

PME overexpression are characterized by increased level of methanol emission [

18] and resistance to polyphagous insect pests [

19]. Another research group analyzed transcriptome of transgenic tobacco plants with increased methanol emission [

17] and revealed changes in the expression of transcription factors related to plant-herbivore interactions together with cell-wall modifying enzymes. The molecular mechanisms underlying methanol-induced defense response is still mainly unknown. Methanol was demonstrated to activate specific factors, encoded by methanol-inducible genes (MIGs) which participate in the plant's resistance to both biotic stress factors [

18,

20]. Most of these genes are involved in defense reactions and intercellular transport. Plants treatment with physiological concentration of gaseous methanol leads to activation of intercellular transport of macromolecules and impeded nucleocytoplasmic transport that results in creation of favorable conditions for viral infection as an unintended consequence of the induced antibacterial resistance [

18]. Among selected MIGs are

NbAELP (a gene encoding aldose-1-epimerase-like protein, previously designated as NCAPP) and 1,3-beta-glucanase (BG) that were shown to participate in activation of intercellular transport of macromolecules and stimulation of tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) RNA accumulation [

18]. Moreover, NbAELP was demonstrated to affect nucleocytoplasmic transport [

21] as well as PME [

22].

Plasmodesmata (PD) act as pathways for transporting different compounds such as proteins, nucleic acids, hormones, and metabolites, crucial for signaling during plant development and defense [

5]. The flow through PD is controlled by various mechanisms, among which the most extensively studied is callose-dependent regulation of PD permeability via modulation of callose depositions in the cell wall near these channels. Callose turnover is maintained by several enzymes that are involved in callose synthesis, degradation, and stabilization [

23]. Furthermore, research into proteins associated with PD [

24], the interactions between the endoplasmic reticulum and the plasma membrane (PM) around these channels [

25], and the specific lipid composition of the PM within them [

26] has broadened our understanding of PD function [

27]. Recent evidence suggests that signals from different cell organelles, primarily mitochondria and chloroplasts, also play a role in controlling plasmodesmata. These signals are transmitted to the cell nucleus and impact the expression of genes involved in regulating intercellular transport and plasmodesmata function [

4,

28,

29]. However, the exact mechanisms and components involved in this signaling pathway are still to be elucidated. Therefore, regulation of plasmodesmata involves proteins within the channels themselves as well as signal pathways from organelles to the nucleus.

Previously, among MIGs we have identified gene with an unknown function, designated

NbMIG21 and demonstrated its involvement in regulation of intercellular transport of macromolecules as well as ability to stimulate TMV-based vector reproduction [

18]. In the current study we further investigated

NbMIG21 features and functions. We demonstrated that NbMIG21p has nuclear localization and is concentrated in subnuclear structures, in particular, nucleolus. Similar to NbAELP and PME, NbMIG21p interferes with nucleocytoplasmic transport as was demonstrated using GFP-NLS reporter molecule. Moreover, increased

NbMIG21 expression stimulates intercellular transport of TMV-based viral vector. Finally, we have isolated

NbMIG21 promoter region, demonstrated its sensitivity to methanol and shown, that recombinant NbMIG21p has DNA-binding properties being able to bind various promoters including its own one.

Thus we suggested that NbMIG21 could be one of the players participating in organelle-to-nucleus plasmodesmata signaling and affecting both nucleocytoplasmic and intercellular transport. We hypothesize that NbMIG21 might participate in creating favorable conditions for the viral reproduction (i) interfering with nucleocytoplasmic transport of the macromolecules that could include antiviral cellular factors, (ii) increasing plasmodesmata permeability leading to enhanced viral spread.

3. Discussion

Gaseous methanol was demonstrated to be a signal molecule that activates methanol-inducible genes (MIGs) expression. It was shown that both methanol treatment and increased expression of such MIGs as

BG,

NbAELP and

NbMIG21 stimulated intercellular transport of 2xGFP and TMV-based viral vector reproduction [

18]. However, the mechanism of MIGs activation and functioning is still to be elucidated. Here we took a closer look at uncharacterized

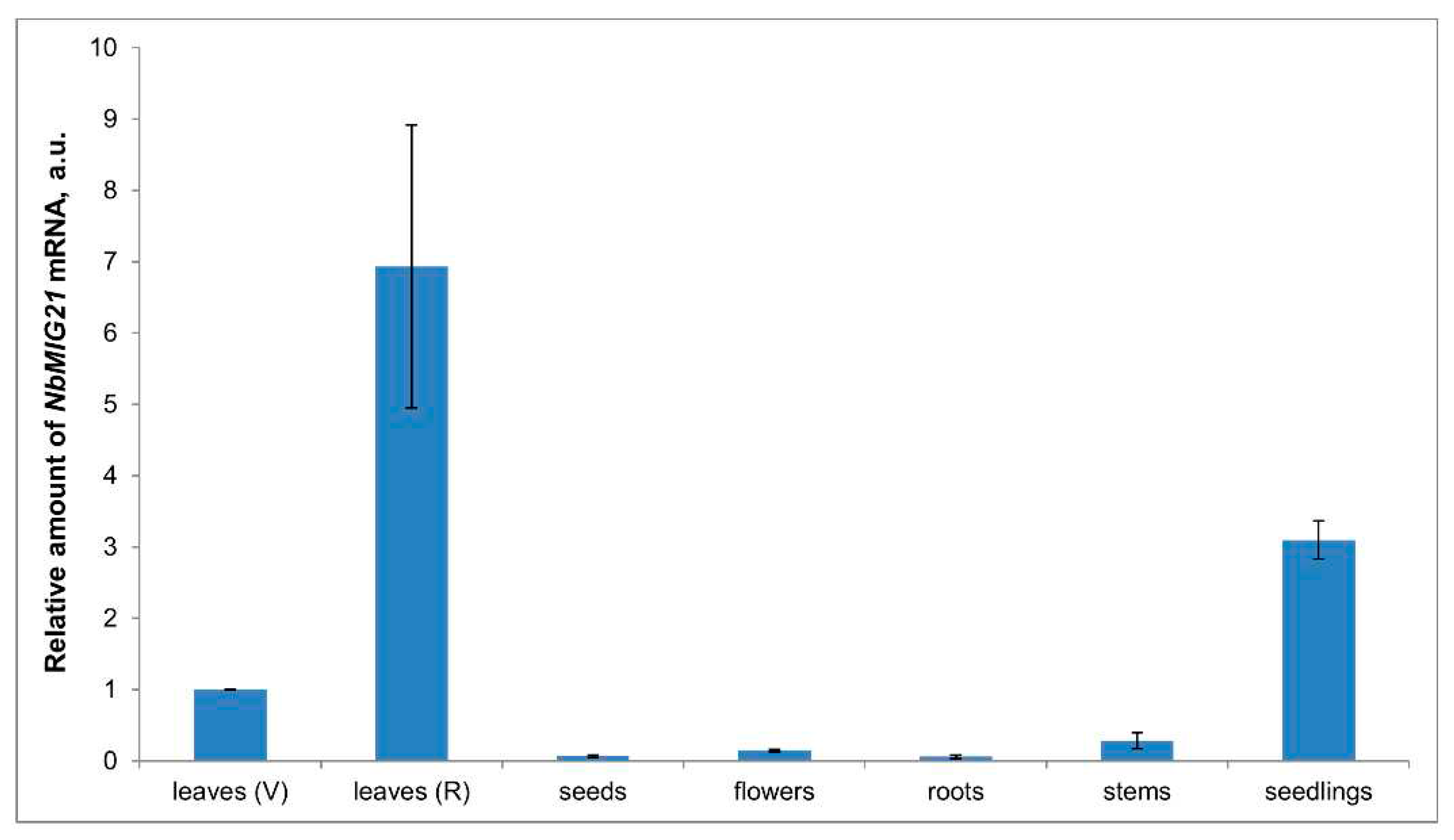

NbMIG21 identified earlier as a gene expression of which increases in response to gaseous methanol.

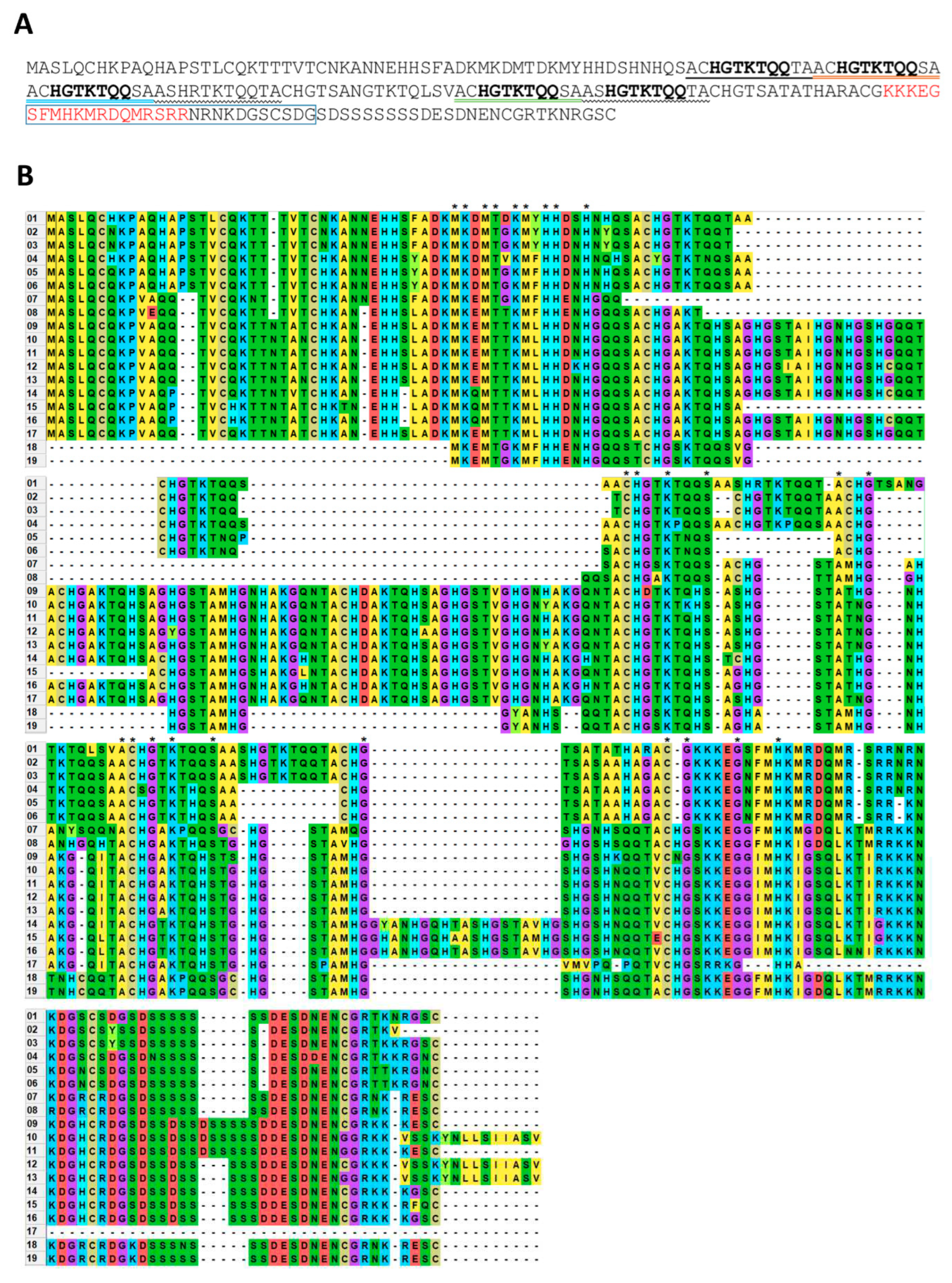

NbMIG21-encoded protein, NbMIG21p, is rich in glutamine residues, contains several amino acid repeats, predicted NLS and NoLS. We have found NbMIG21p homologues only among predicted proteins of

Solanaceae species but not among annotated proteins. Noteworthy, all aligned sequences are rather conservative, they contain repeats and arginine/lysine- and serine-rich stretches the C-terminal part (

Figure 2).

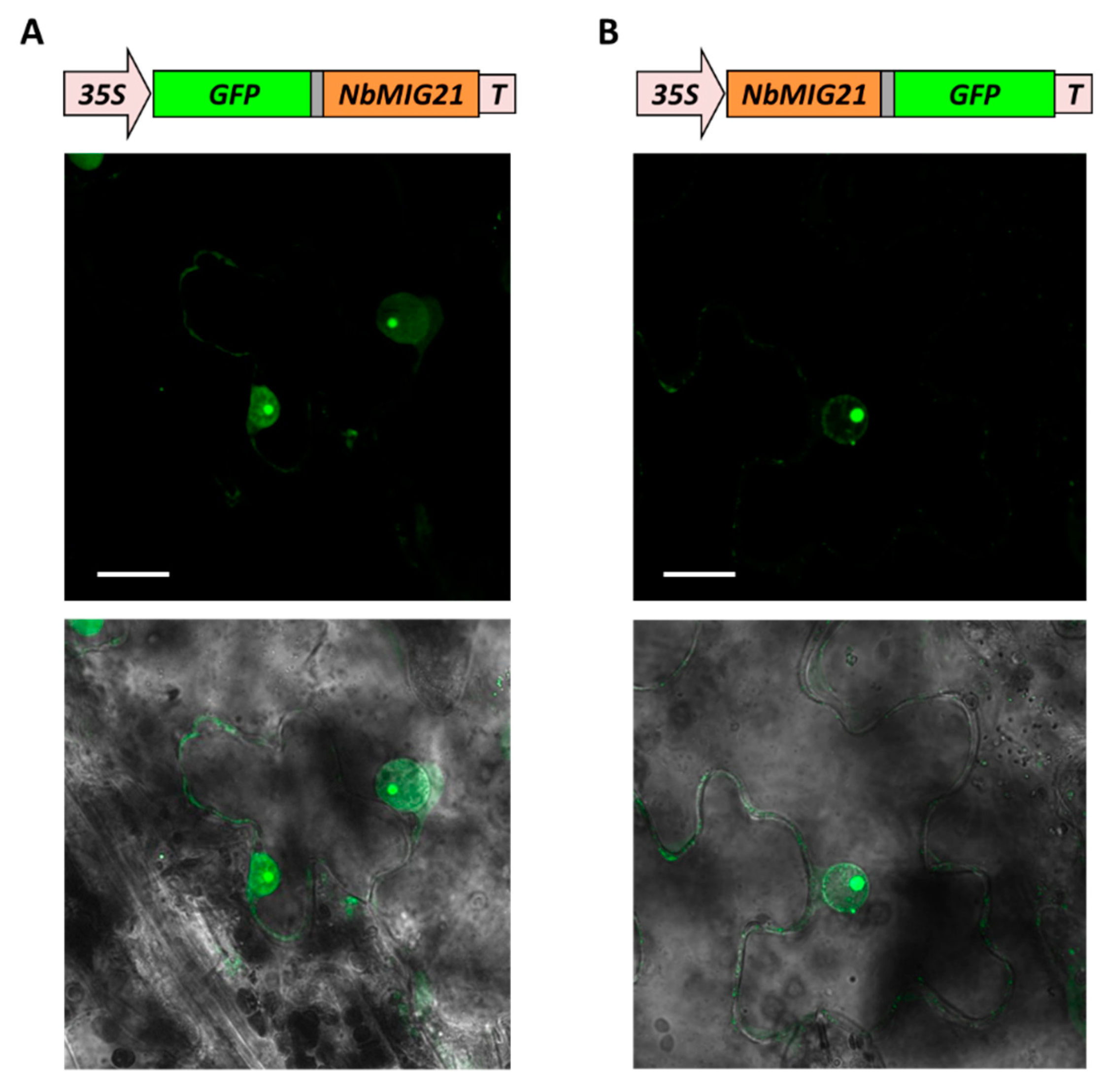

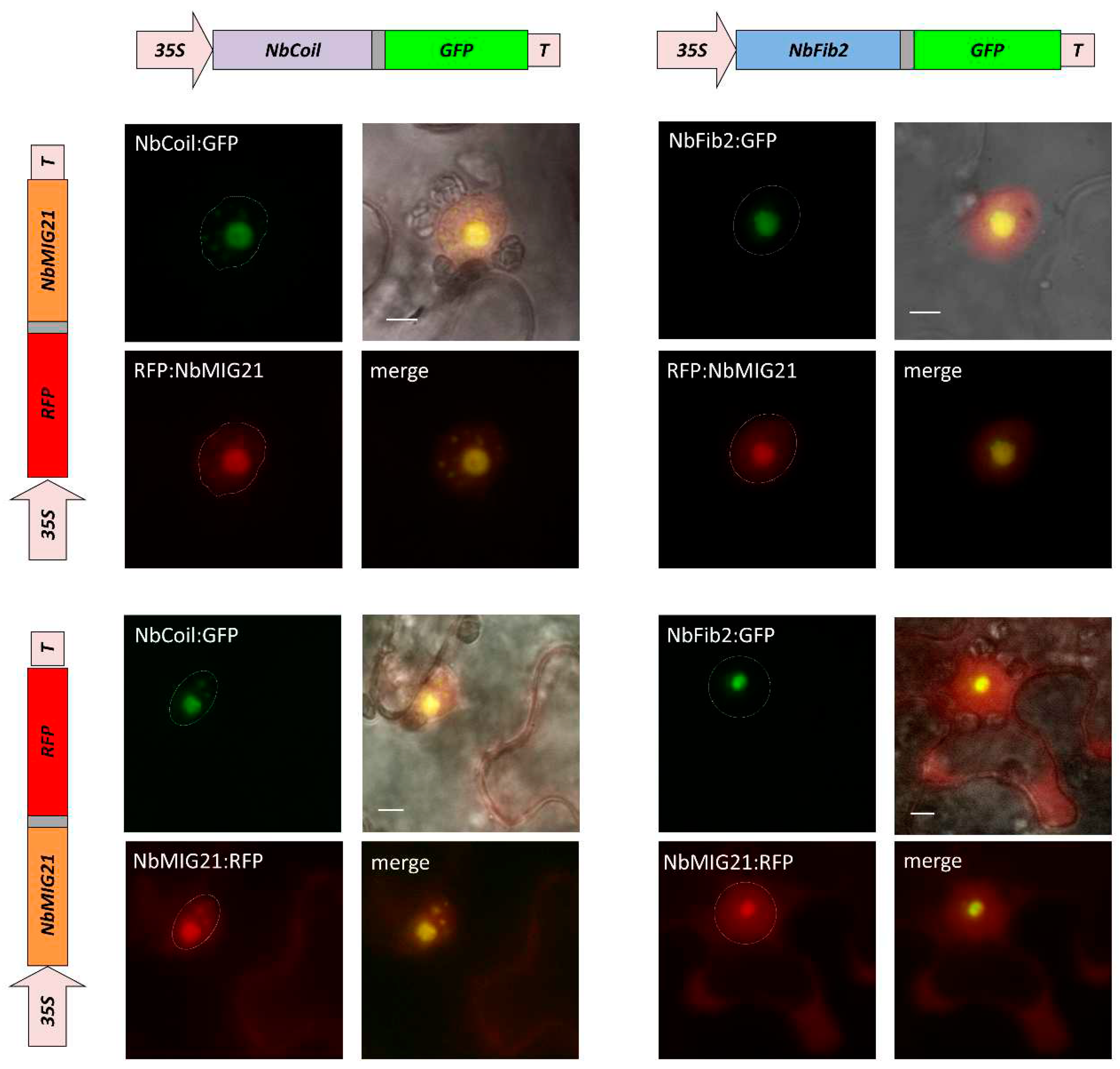

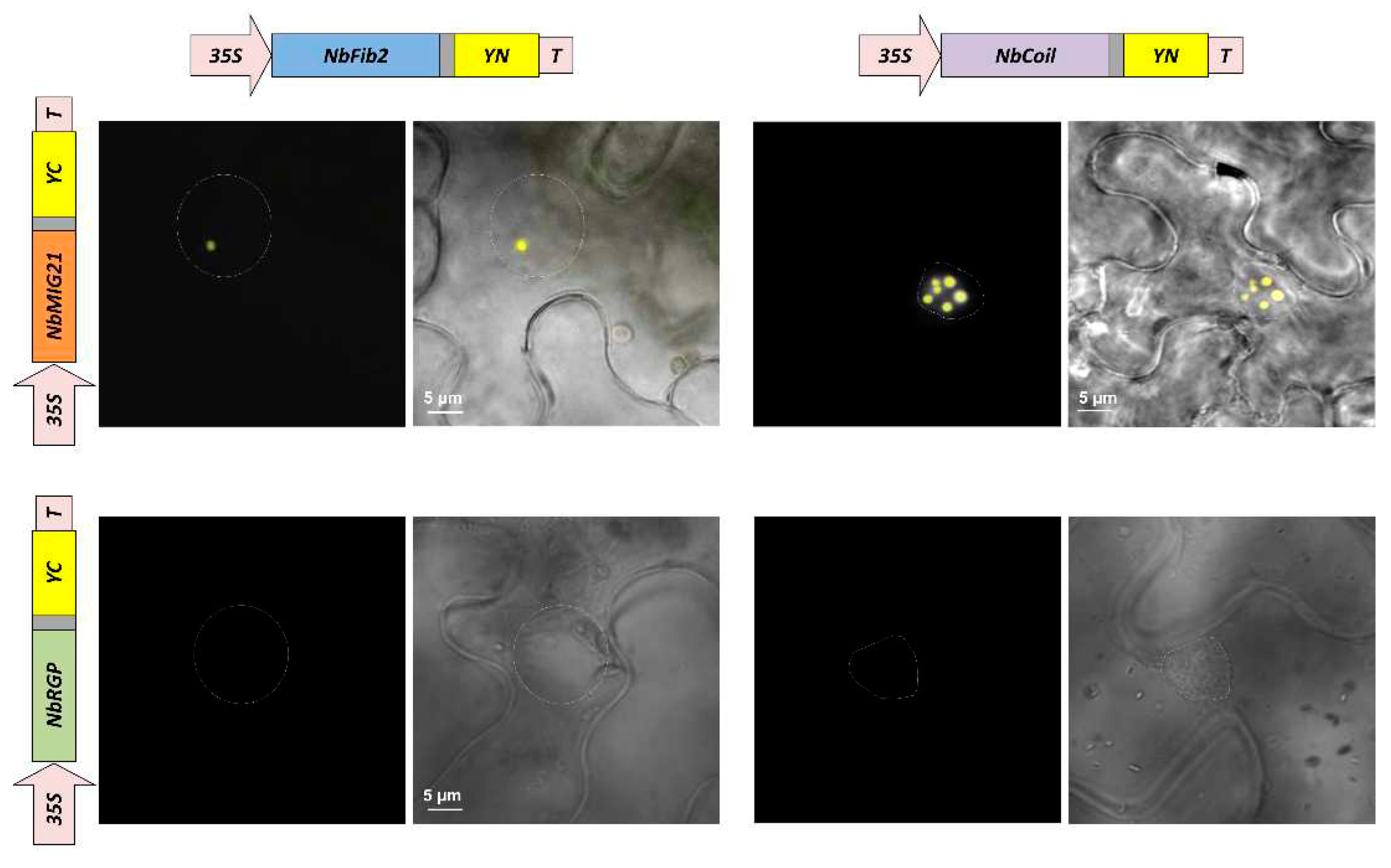

Analysis of NbMIG21p intracellular distribution revealed that it is indeed nucleus- and nucleolus-localized protein. It potentially interacts with the major nucleolus protein fibrillarin and Cajal bodies protein coilin as was shown in co-localization experiments and using BiFC system (

Figure 5). Despite fibrillarin and coilin are regarded as markers of abovementioned subnuclear structures, they are also detected in other regions of the nucleus. For example, RFP-tagged fibrillarin localized both to the nucleolus and Cajal bodies, while overexpressed coilin fused with GFP was visualized in nucleoplasm, Cajal bodies and nucleolus [

43]. Thus, based on co-localization studies we could conclude that NbMIG2p is distributed between nucleoplasm, nucleolus and Cajal bodies.

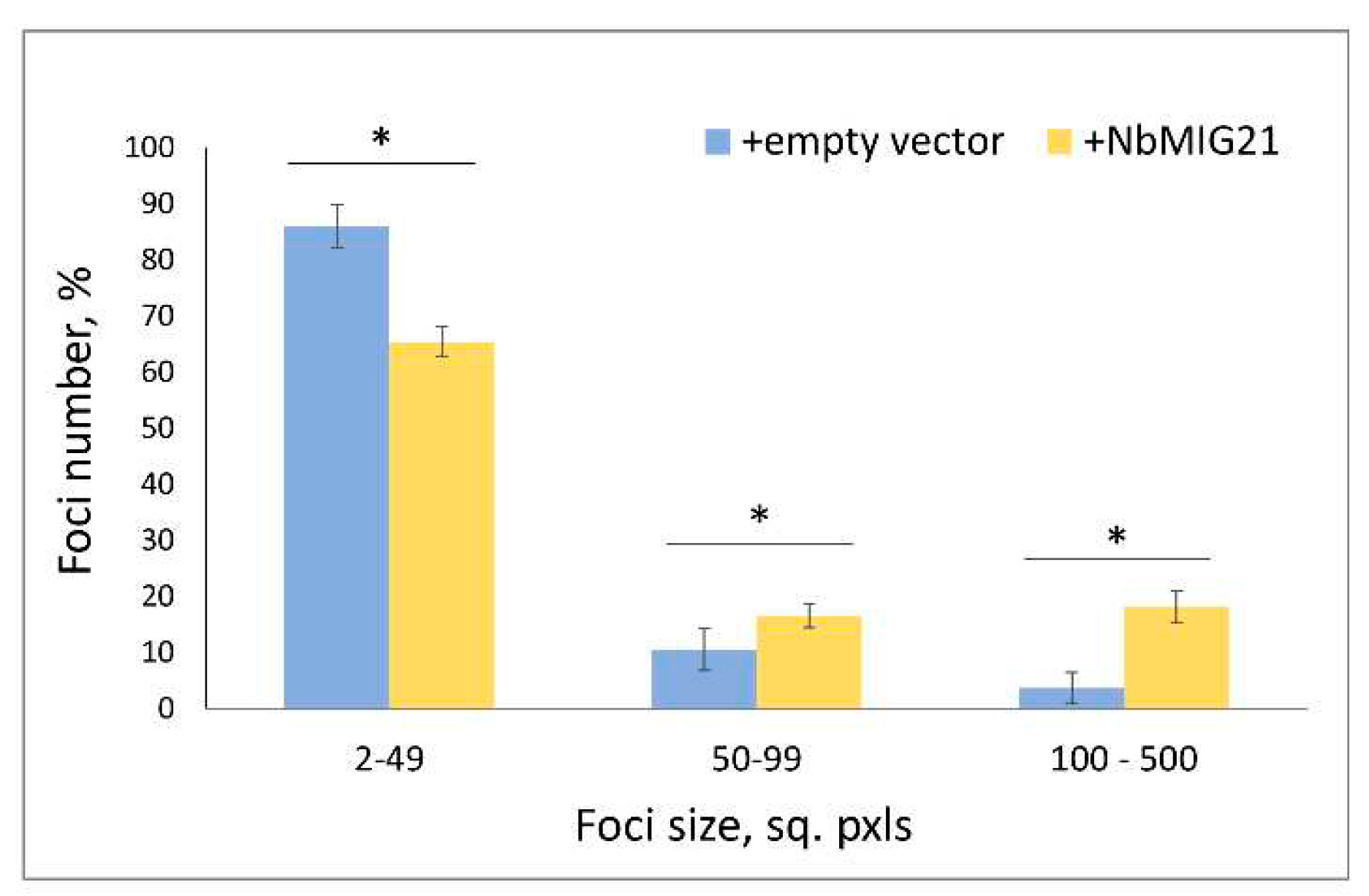

Previously it was shown that increased

NbMIG21 expression stimulates accumulation of GFP produced from TMV-based viral vector [

18]. However, viral vector reproduction is the sum of replication, RNA stability and transport, and from the reported results it was unclear whether the obtained effect was due to the facilitation of transport or stimulation of viral RNA replication and accumulation. Here we have shown that

NbMIG21 increased expression induced activation of TMV:GFP local spread leading to formation of larger GFP-expressing infection foci (

Figure 7). At the same time, GFP fluorescence intensity in the analyzed foci did not differ between experimental group and control (

Figure S4) indicating comparable levels of vector-mediated GFP expression and accumulation. Thus, conditions favorable for viral infection are created mainly due to stimulation of intercellular transport and increased efficiency of viral local spread upon increased

NbMIG21 expression.

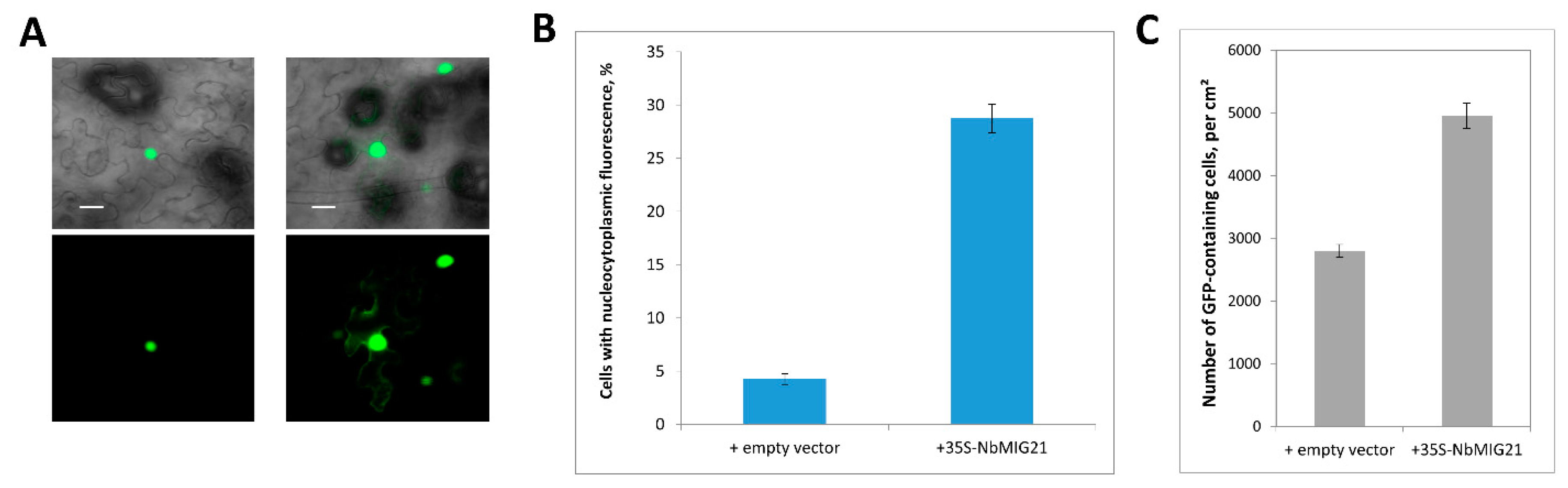

However, we could not exclude the impact of NbMIG21p effect on nucleocytoplasmic transport in stimulation of viral vector reproduction. It is known that plant viruses of different taxonomy groups (including viruses the lifecycle of which takes place in the cytoplasm) exploit nucleus of the host cell and interact with nuclear factors to facilitate infection [

44]. Moreover, the same nuclear protein could play opposite role for different viruses – stimulating or suppressing it as was shown, for example, for coilin [

43]. NbMIG21p interferes with nucleocytoplasmic transport similar to another MIG – NbAELP that was also demonstrated to impede GFP:NLS nuclear import [

21] and stimulate viral vector reproduction [

18]. PME, which is not a MIG but is a key player in methanol production, represents another example of the factor that prevents NLS-containing proteins from entering the nucleus in favor of viral infection: PME-induced inhibition of ALY nuclear import results in substantial increase in viral reproduction [

22,

45]. Thus, we suggested that one of the mechanisms of NbMIG21p-mediated facilitation of viral infection is realized via interference with nucleocytoplasmic transport.

Taking into account that the motif search engine (

https://www.genome.jp/tools/motif/) revealed a motif resembling ubinuclein conserved middle domain in NbMIG21p sequence (

Figure S2) we can speculate that NbMIG21p might be involved in chromatin reorganization processes caused by abiotic stress as was demonstrated for ubinucleins [

46]. The online resource

http://www.ebi.ac.uk/thornton-srv/databases/pdbsum/ found a list of various protein domains with rather low similarity to NbMIG21p but even though among them were nucleic acid-binding ones: Zinc finger Ran-binding domain-containing protein 2 (O95218) localized in nucleus [

47] and ADP-ribosylation factor-like protein 6-interacting protein 4 (Q66PJ3) involved in modulating alternative pre-mRNA splicing also localized in nucleus and nucleolus [

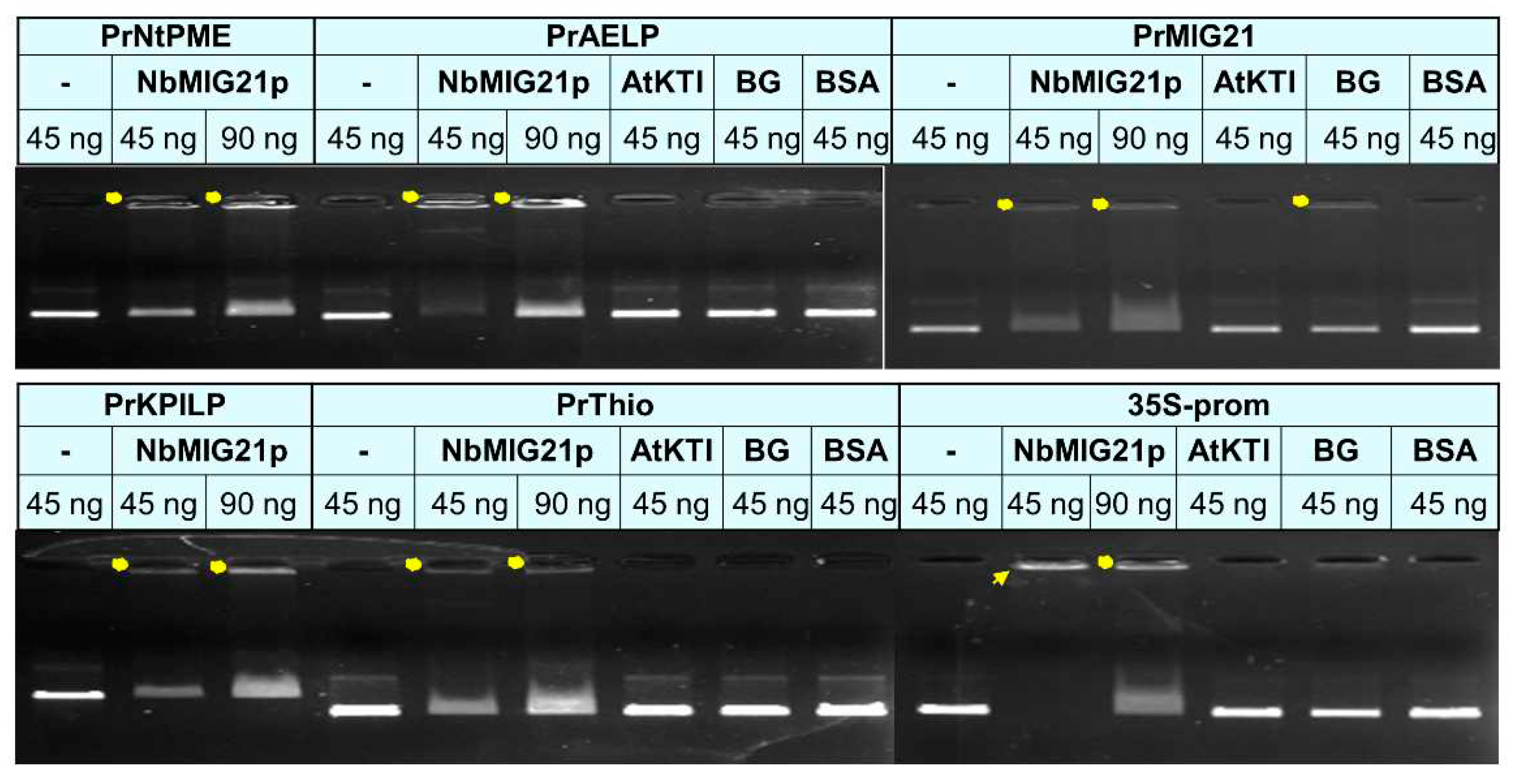

48]. Taken together NbMIG21p localization in nucleus and nucleolus could indicate nucleic acids binding properties. Indeed, NbMIG21p was shown to be able to bind nucleic acids, in particular DNA as was demonstrated

in vitro in gel retardation assay. We tested promoter regions and revealed the most efficient binding for the 35S-promoter of Cauliflower mosaic virus (

Figure 10) which is the “strongest” of all assessed sequences (i.e. provides the highest level of mRNA accumulation). Such DNA-binding property could indicate that NbMIG21p participates in regulation of intercellular transport affecting genes expression. Nucleic acid binding proteins are crucial for various biological processes, including replication, transcription, and translation [

49]. Among these proteins are transcription factors, chromatin remodelers, and RNA-binding proteins, etc. The regulation of their genes involves complex mechanisms that control their expression at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. Various regulatory elements, such as enhancers, promoters, and transcription factor binding sites, modulate the expression of these genes. Inducible promoters are often found in genes that need to be turned on or off rapidly in response to changes in the cellular environment [

50]. Inducible promoters allow dynamic control of gene expression, enabling cells to adapt to various internal and external cues, including stress, developmental signals, or environmental changes. The activators of such promoters are often small molecules or proteins. We obtained and characterized

NbMIG21 promoter, which was experimentally confirmed to be activated in response to gaseous methanol. PrMIG21-mediated

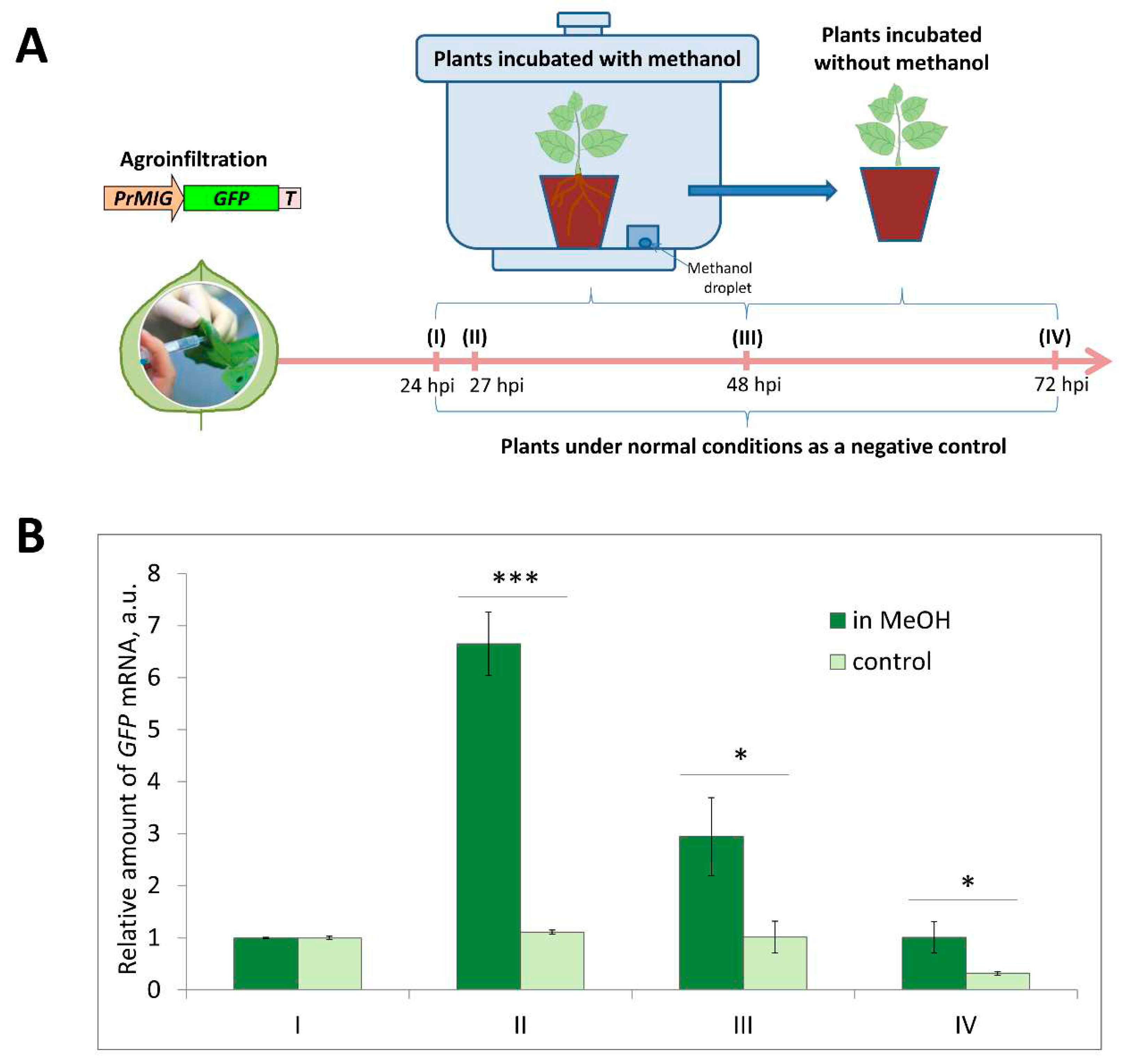

GFP mRNA accumulation significantly increased after 3-h incubation with gaseous methanol and started to decrease but still was elevated after 24-h methanol treatment (

Figure 9). This is in line with previously obtained results on endogenous

NbMIG21 expression: earlier it was shown that

NbMIG21 mRNA level increased after 3-h incubation in desiccator with methanol vapors and peak after 21-h of further plants incubation in normal conditions [

18]. According to bioinformatic analysis PrMIG21 contains various regulatory elements including stress-responsive and hormone-sensitive (

Table S1). Methanol could act directly on some unidentified sequence in PrMIG21 or indirectly via known transcription factors, however, this is the subject of further studies.

Collectively, our results on

NbMIG21 properties and functions indicate that it is one of key players that is responsible for manifestation of methanol-induced response of the plant cell. Here we focused on

NbMIG21 effect towards viral infection, however, the other important aspect of methanol action is induction of antibacterial resistance.

NbMIG21 involvement in it could be exhibited at the level of nucleocytoplasmic transport control and gene expression regulation. It is known, that bacterial pathogens exploit host cell nucleus during colonization, they possess special proteins – nucleomodulins – that can enter the nucleus and affect host gene expression interfering with plant immune response thus facilitating bacterial reproduction [

51]. Methanol-induced susceptibility to the viral infection is the reverse side of acquired resistance to bacteria. And it is not the only example of balancing between resistance and susceptibility: recently it was shown that increased production of NLS-containing proteins (as a mimetic of nucleomodulins) in plant cell leads to the induction of γ-thionin, a factor of antibacterial defense response, but the side effect of this cellular reaction is sensitivity to the virus – viral vector reproduction is stimulated both upon γ-thionin elevated expression or massive synthesis of foreign NLS-containing proteins. The exact mechanism of these effects is unknown but likely it involves interference with nucleocytoplasmic transport [

40].

Therefore, the potential role of NbMIG21 in resistance to bacterial pathogens and the mechanism of NbMIG21p functioning are the subject of further studies as well as the properties of other MIGs.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Growth Conditions

Wild type Nicotiana benthamiana plants were grown in pots with a mixture of leafy soil, humus, peat and sand under standard conditions in a temperature-controlled greenhouse at 25/18 ̊C with a day/night cycle of 16/8 hours. The 6-7-week-old plants with 5-6 true leaves were used in the experiments unless otherwise specified.

4.2. Agroinfiltration

Agrobacterium tumefaciens (strain GV-3101) was grown at 28° on LB medium with appropriate antibiotics (50µg/mL rifampicin, 25µg/mL gentamicin and 50µg/mL kanamycin or carbenicillin depending on the plasmid). Agroinfiltration buffer containing 10 mM MES (pH 5.5) and 10 mM MgCl2 was added to an aliquot of an overnight culture of A. tumefaciens to dilute it to the OD600 0.1 or 0.005 for TMV:GFP experiment. Mixtures for infiltration except TMV:GFP and GFP-NLS experiments were supplemented with agrobacteria containing plasmid for expression of p19 silencing suppressor of Tomato bushy stunt virus. Leaves of N. benthamiana plants were infiltrated with agrobacterium suspension using a syringe without needle.

4.3. Whole Plant Methanol Treatment

Fully expanded leaves of N. benthamiana were infiltrated with agrobacterium containing PrMIG21-GFP plasmid. 24 hours post inoculation (hpi), samples were collected using a hole punch, and three plants were placed into a 20-l desiccator that contained a droplet of methanol on filter paper (200µl) and sealed for 24 hours, while the remaining three plants were maintained under standard conditions. Subsequently, all plants were kept without methanol for an additional 24 hours. Samples from leaves were collected in several time points: 24, 27, 48 and 72 hpi.

4.4. GFP, RFP and YFP Imaging

GFP fluorescence in the infected leaves was observed under a handheld UV source. TMV:GFP foci were analyzed 5 days post inoculation (dpi). GFP and YFP fluorescence was visualized using an AxioVert 200M microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with an AxioCam MRc digital camera. The excitation/detection wavelength (i) for GFP and YFP was 487/525 nm; for RFP – 561/625 nm, respectively. Confocal microscopy was performed using a Nikon C2 confocal laser scanning microscope. The intracellular distribution of fluorescent proteins was observed 72 hours after infiltration. TMV:GFP foci area and fluorescence intensity were measured using open-source ImageJ software [

52].

4.5. Genomic DNA Extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from frozen in liquid nitrogen N. benthamiana leaves using the Diatom DNA Prep kit as per the manufacturer's protocol (Galart-Diagnosticum, Moscow, Russia).

4.6. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from plant tissues using TriReagent (MRC, Houston, TX, USA). The RNA concentration was determined using a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Isogen Life Sciences, Utrecht, The Netherlands). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using random hexamers, oligo-dT primer, and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

4.7. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the iCycler iQ real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Target genes were amplified using specific primers and Eva Green master mix (Syntol, Moscow, Russia), while reference genes were amplified using primers to the 18S rRNA gene and the protein phosphatase 2A gene (PP2A) (

Table S2). Each sample was run in triplicate, and a non-template control was included. At least five biological replicates were performed, and the qRT-PCR results were analyzed using the Pfaffl algorithm [

53].

4.8. Plasmid Constructs

To obtain NbMIG21 coding sequence PCR using

N. benthamiana cDNA as a template with following primers “N-NbMIG21-

Acc65I_f”/“C-NbMIG21-

SalI_r” was performed and PCR product was cloned into pAL2-T plasmid (Evrogen, Moscow, Russia). To obtain a set of constructs encoding NbMIG21 fusions with various fluorescent protein: 35S-NbMIG21:GFP, 35S-NbMIG21:RFP, 35S-NbMIG21:YC and NbMIG21:YN, a fragment encoding NbMIG21 without a stop codon and flanked by Acc65I/BamHI recognition sites was synthesized using “N-NbMIG21-

Acc65I_f”/”N-NbMIG21-

BamHI_r” pair of primers. This fragment was digested with Acc65I/BamHI and inserted into pCambia-35S vector containing either GFP-, RFP-, YN- or YC-encoding sequence without start codon [

37] using the same sites.

To obtain 35S-GFP:NbMIG21, 35S-YN:NbMIG21 and 35S-YC:NbMIG21 plasmids NbMIG21 fragment without start codon was synthesized using “C-NbMIG21-BamHI_f”/“C-NbMIG21-SalI_r” pair of primers. Corresponding fluorescent tag-encoding sequence without stop codon was amplified using “GFP-Acc65I_f”/“GFP-BamHI_r”, “YN-Acc65I_f”/“YN-BamHI_r”, “YC-Acc65I_f”/“YC-BamHI_r” pair of primers, respectively. NbMIG21 fragment was digested with BamHI/SalI, GFP, YN and YC fragments were digested with Acc65I/BamHI. Each fragment encoding the corresponding fluorescent tag together with NbMIG21 fragment was ligated into modified pCambia-35S vector digested with Acc65I/SalI enzymes.

Sequences encoding coilin (NbCoil, GeneBank accession number MK903618.1) and fibrillarin (NbFib2, GeneBank accession number AM269909.1) without a stop codon were amplified from N. benthamiana cDNA using the “NbCoilin-Acc65I_f”/“NbCoilin-BamHI_r” and “NbFib2-Acc65I_f”/“NbFib2-BamHI_r” primer pairs. The algorithm for obtaining 35S-NbCoil:GFP, 35S-NbCoil:YN, 35S-NbCoil:YN and 35S-NbFib2:GFP, 35S-NbFib2:YN, 35S-NbFib2:YC was the same as for NbMIG21-encoding constructs.

To obtain a plasmid for NbMIG21 recombinant protein production in Escherichia coli cells, NbMIG21-encoding fragment without a start codon was obtained with the “6H-NbMIG21-Acc65I_f”/“C-NbMIG21-SalI_r” primer pair and Acc65I and SalI recognition sites at the ends of the resulting fragment. The PCR product was digested with the Acc65I-SalI restriction enzymes and cloned into the pQE-30 vector (QIAGEN, Netherlands) digested with Acc65I/SalI. Therefore, 6xHis-NbMIG21 was obtained.

4.9. Production of Recombinant MIG21 Protein

NbMIG21 with N-terminal hexahistidine tag (6xHis) was obtained according to the protocol outlined in The QIAexpressionist™ handbook. E. coli (strain SG13009) was used for accumulation of the recombinant protein. 6xHis-NbMIG21 purification was performed using immobilized-metal affinity chromatography on Ni-NTA agarose resin. Eluted from Ni-NTA column 6xHis-NbMIG21 was analyzed by SDS PAAG electrophoresis and dialyzed using a dialysis tubing (Spectrum Laboratories Specpor 4, 12-14K MWCO). The initial dialysis buffer contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 4.5), 2 M urea and 80 mM NaH2PO4 with a stepwise reduction of urea and NaH2PO4 content. Dialysis was performed for 2 hours in each buffer and overnight incubation in the final buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 4.5) and 20 mM NaH2PO4) at +4ᵒC. Further samples were concentrated using Sephadex dry powder.

4.10. In vitro DNA Binding and Gel Retardation Assay

200 ng of dialyzed recombinant 6xHis-MIG21 was added to 45 or 90 ng of DNA fragments corresponding to each of the tested promoter sequences. Binding was performed in the buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT, 3 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl, for 1 h on ice. Bovine serum albumin, recombinant A. thaliana Kunitz trypsin inhibitor (AtKTI) and N. benthamiana 1,3-beta-glucanase (BG) were used as negative controls. Samples were then loaded to 1% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide and electrophoretic analysis was performed.

4.11. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis involved the use of Student’s t-test. The y-axis error bars in all histograms represent the standard error of the mean values.

Figure 3.

NbMIG21p intracellular localization. Images of 35S-GFP:NbMIG21 (A) or 35S-NbMIG21:GFP (B) expressing epidermal cells of N. benthamiana leaves 3 dpi obtained using confocal fluorescence microscopy. Projection of several confocal sections (left) superimposed on a bright field image of the same cell (right). Bars = 20 μm. 35S, Cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter; T, 35S terminator of transcription.

Figure 3.

NbMIG21p intracellular localization. Images of 35S-GFP:NbMIG21 (A) or 35S-NbMIG21:GFP (B) expressing epidermal cells of N. benthamiana leaves 3 dpi obtained using confocal fluorescence microscopy. Projection of several confocal sections (left) superimposed on a bright field image of the same cell (right). Bars = 20 μm. 35S, Cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter; T, 35S terminator of transcription.

Figure 4.

NbMIG21p co-localizes with fibrillarin and coilin. Schematic representation of genetic constructs encoding RFP-tagged NbMIG21p (left) and GFP-tagged fibrillarin or coilin (top). Fluorescent images of N. benthamiana cells 3 days after co-agroinfiltration with either 35S-NbMIG21:RFP or 35S-RFP:NbMIG21 and 35S-NbFib2:GFP or 35S-NbCoil:GFP. Nucleus is marked with a dashed line. Bar=5µm.

Figure 4.

NbMIG21p co-localizes with fibrillarin and coilin. Schematic representation of genetic constructs encoding RFP-tagged NbMIG21p (left) and GFP-tagged fibrillarin or coilin (top). Fluorescent images of N. benthamiana cells 3 days after co-agroinfiltration with either 35S-NbMIG21:RFP or 35S-RFP:NbMIG21 and 35S-NbFib2:GFP or 35S-NbCoil:GFP. Nucleus is marked with a dashed line. Bar=5µm.

Figure 5.

NbMIG21p co-localizes with fibrillarin and coilin. YFP fluorescence analyzed using fluorescent microscopy 3 days after infiltration of N. benthamiana leaves with pairs of agrobacteria containing plasmids for expression of 35S-NbMIG21:YN and 35S-NbFib2:YC (left), 35S-NbMIG21:YC and 35S-NbCoil:YN (right). For each pair fluorescence image and superimposed on visible light image are presented. 35S-NbRGP1:YC is used as a negative control. Nucleus is marked with a dashed line. Bar=5µm.

Figure 5.

NbMIG21p co-localizes with fibrillarin and coilin. YFP fluorescence analyzed using fluorescent microscopy 3 days after infiltration of N. benthamiana leaves with pairs of agrobacteria containing plasmids for expression of 35S-NbMIG21:YN and 35S-NbFib2:YC (left), 35S-NbMIG21:YC and 35S-NbCoil:YN (right). For each pair fluorescence image and superimposed on visible light image are presented. 35S-NbRGP1:YC is used as a negative control. Nucleus is marked with a dashed line. Bar=5µm.

Figure 6.

Increased expression of NbMIG21 interferes with GFP:NLS nuclear import. (A) Representative images of nuclear (left) and nucleocytoplasmic (right) GFP:NLS distribution. Fluorescent image (lower panel) and overlay on bright-field image (upper panel). Bar = 20 µm. (B) Quantification of GFP:NLS subcellular localization 48 h after infiltration with 35S-GFP:NLS and 35S-NbMIG21 or “empty” vector. (C) Number of GFP:NLS-containing cells per square cm.

Figure 6.

Increased expression of NbMIG21 interferes with GFP:NLS nuclear import. (A) Representative images of nuclear (left) and nucleocytoplasmic (right) GFP:NLS distribution. Fluorescent image (lower panel) and overlay on bright-field image (upper panel). Bar = 20 µm. (B) Quantification of GFP:NLS subcellular localization 48 h after infiltration with 35S-GFP:NLS and 35S-NbMIG21 or “empty” vector. (C) Number of GFP:NLS-containing cells per square cm.

Figure 7.

NbMIG21 increased expression stimulates TMV:GFP intercellular transport. The percentage of TMV:GFP-expressing foci of different sizes quantified at 5th day after agroinfiltration of TMV:GFP and “empty” vector or 35S-NbMIG21. *, p<0.05 (Student’s t-test).

Figure 7.

NbMIG21 increased expression stimulates TMV:GFP intercellular transport. The percentage of TMV:GFP-expressing foci of different sizes quantified at 5th day after agroinfiltration of TMV:GFP and “empty” vector or 35S-NbMIG21. *, p<0.05 (Student’s t-test).

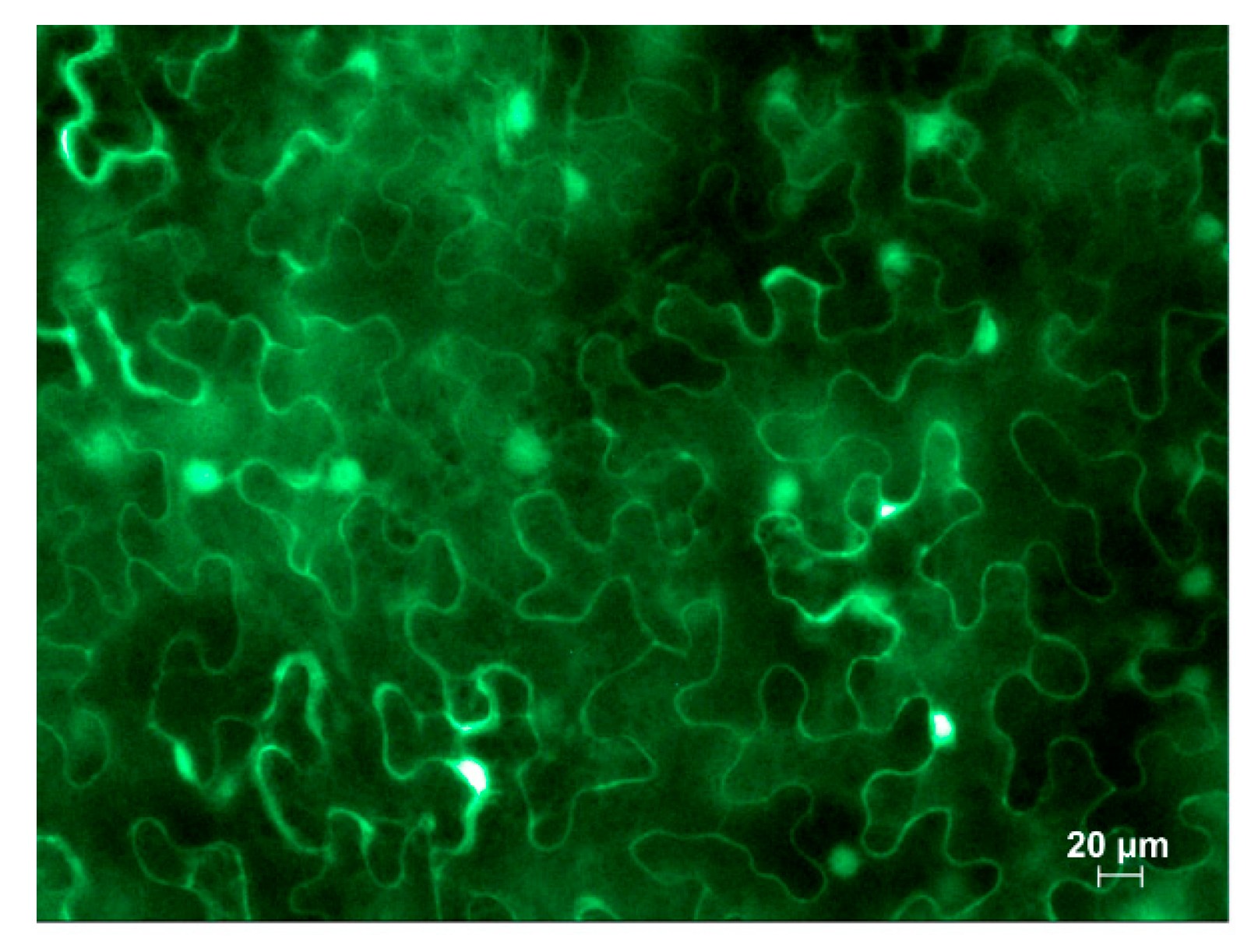

Figure 8.

Fluorescent microscopy image of GFP accumulation in cytoplasm in leaves infiltrated with PrMIG21-GFP at 3 dpi. Mixture for infiltration was supplemented with agrobacteria containing plasmid for expression of p19 silencing suppressor of tomato bushy stunt virus.

Figure 8.

Fluorescent microscopy image of GFP accumulation in cytoplasm in leaves infiltrated with PrMIG21-GFP at 3 dpi. Mixture for infiltration was supplemented with agrobacteria containing plasmid for expression of p19 silencing suppressor of tomato bushy stunt virus.

Figure 9.

PrMIG21 is methanol-sensitive. (A) Schematic representation of experimental work flow with sample collecting time points indicated. (B) Relative amount of GFP mRNA in leaves of N. benthamiana plants agroinfiltrated with PrMIG21-GFP and treated with gaseous methanol. Amount of GFP mRNA at time point “I” is taken as 1. Student’s t-test was applied to assess statistical significance of difference between control plants and plants incubated with methanol. *, p<0.05, ***, p<0.001.

Figure 9.

PrMIG21 is methanol-sensitive. (A) Schematic representation of experimental work flow with sample collecting time points indicated. (B) Relative amount of GFP mRNA in leaves of N. benthamiana plants agroinfiltrated with PrMIG21-GFP and treated with gaseous methanol. Amount of GFP mRNA at time point “I” is taken as 1. Student’s t-test was applied to assess statistical significance of difference between control plants and plants incubated with methanol. *, p<0.05, ***, p<0.001.

Figure 10.

Gel retardation assay of PCR fragments representing promoter regions and 6xHis-NbMIG21. Two amounts of PCR fragments were used – 45 and 90 ng – as indicated above each lane. NbMIG21p and control proteins were used in a concentration of 200 ng. Yellow dots indicate retarded NbMIG21p-bound PCR fragments, arrow indicates fully bound PCR fragment of 35S promoter. AtKTI, A. thaliana Kunitz trypsin inhibitor (AtKTI); BG, N. benthamiana beta-1,3-glucanase; BSA, bovine serum albumin, were used as negative controls.

Figure 10.

Gel retardation assay of PCR fragments representing promoter regions and 6xHis-NbMIG21. Two amounts of PCR fragments were used – 45 and 90 ng – as indicated above each lane. NbMIG21p and control proteins were used in a concentration of 200 ng. Yellow dots indicate retarded NbMIG21p-bound PCR fragments, arrow indicates fully bound PCR fragment of 35S promoter. AtKTI, A. thaliana Kunitz trypsin inhibitor (AtKTI); BG, N. benthamiana beta-1,3-glucanase; BSA, bovine serum albumin, were used as negative controls.