3.1. Correlation analysis

The degree of correlation of the same parameters observed on different spacecraft can be interpreted as a measure of the variability of the SW stream on the way from one spacecraft to another. The time course of most parameters does not change significantly when the spacecraft are relatively close to each other. The

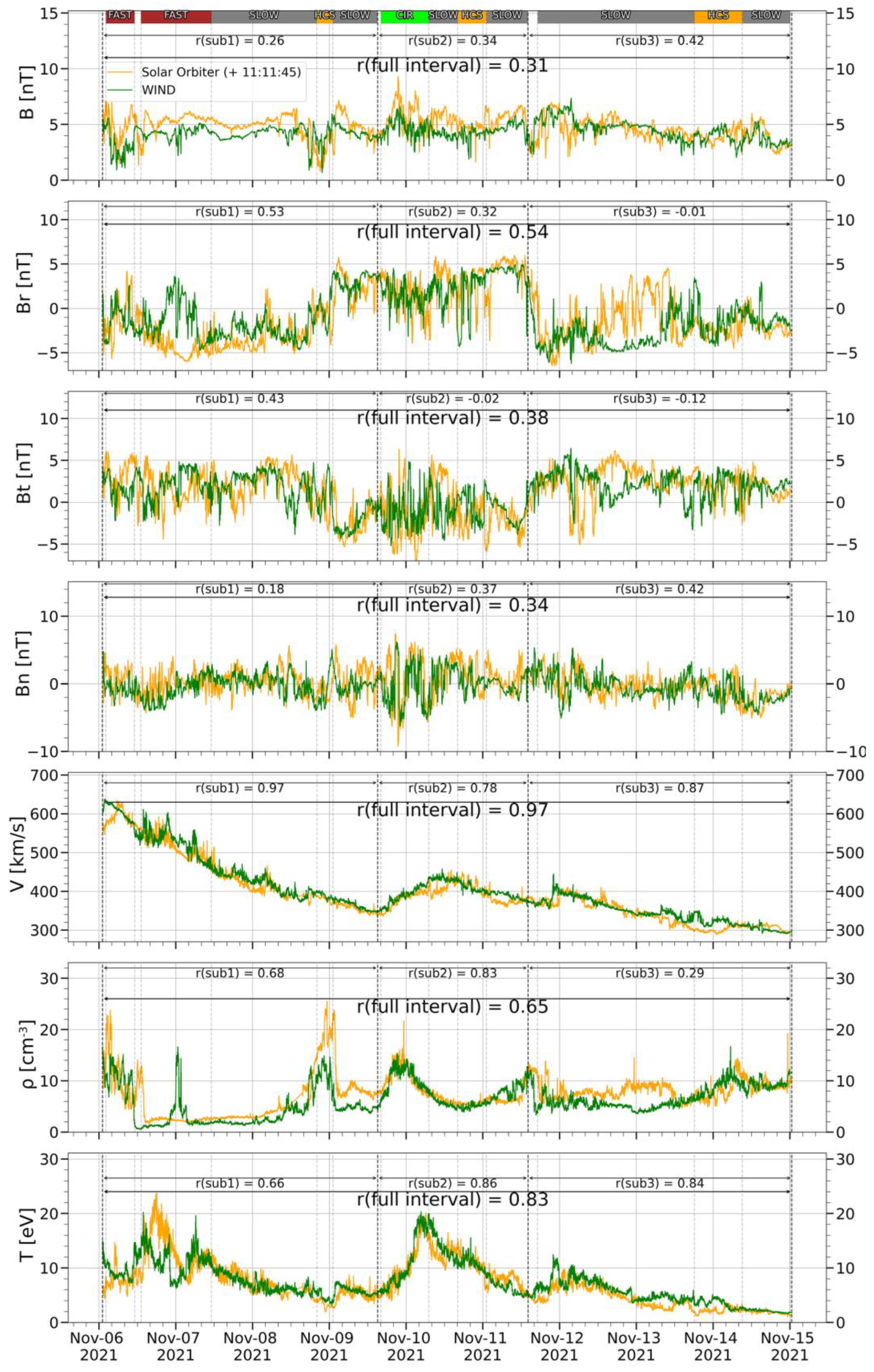

Figure 5 shows the time course of SW plasma and IMF parameters observed on the SolO and WIND during the first selected time interval (the distance between spacecraft is ~0.1 AU). The best agreement is observed between the proton bulk speed observed at two spacecraft. In this case, the rough time shift estimate (11 hours and 11 minutes) by Formula 2 provides a good coincidence of the time course of the bulk speed over the entire event, where the overall correlation coefficient is 0.97.

The correlation coefficient might differ for shorter subintervals over which different types of structures are observed. The division of the interval into shorter ones was carried out in accordance with the bulk speed similar to the approach described in

Section 2. The division into subintervals was carried out in accordance with the plasma structures allocated: smooth descent of the bulk speed on the first, slight rise and then decline on the second, and smooth decrease on the third subinterval respectively. At the first subinterval (2021-11-05 13:54:00 UT — 2021-11-09 03:50:26 UT) the correlation coefficient for bulk speed time course reached a value of 0.97, 0.78 at the second (2021-11-09 03:50:26 UT — 2021-11-11 02:50:26 UT) and 0.87 at the third (2021-11-11 02:50:26 UT — 2021-11-14 13:25:00 UT). The correlation coefficients on

Figure 5 were found with considering the coarse estimation of the time shift by bulk speed and without using the technique of time shift refinement based on correlation analysis since in this case it leads to fairly good result. Even though there is a difference within the observed structures in the second subinterval, the time rows correlate well in general. Temperature values also showed high similarity with the overall correlation coefficient of 0.83 and greater than 0.66 on subintervals (

Figure 5g). Meanwhile the average correlation coefficient of proton density is below 0.68, and on subintervals can be quite high (0.83), as well as it may show a poor fit (0.29). For example, in the first subinterval, only WIND measured a sharp density peak on November 7, 2021. Nevertheless, there is a high similarity in the density structures in first two subintervals, but the correlation decreases to 0.29 the third subinterval (see

Figure 5f), which might be caused by structural discrepancies observed on November 13.

The IMF magnitude and components turned out to be the most unstable parameters with high fluctuation level and with minimal correlation coefficients despite the fact that the spacecraft are quite close to each other.

Figure 5a illustrates the time course of IMF magnitude with overall correlation coefficient is 0.31 and 0.26, 0.34 and 0.42 for each of the three subintervals respectively. The maximum average correlation coefficient is observed for the radial component of IMF (0.54), but it is also quite low on the 2

nd and 3

rd subintervals. Overall, the lowest differences in the time course of all parameters are often observed for the FAST stream.

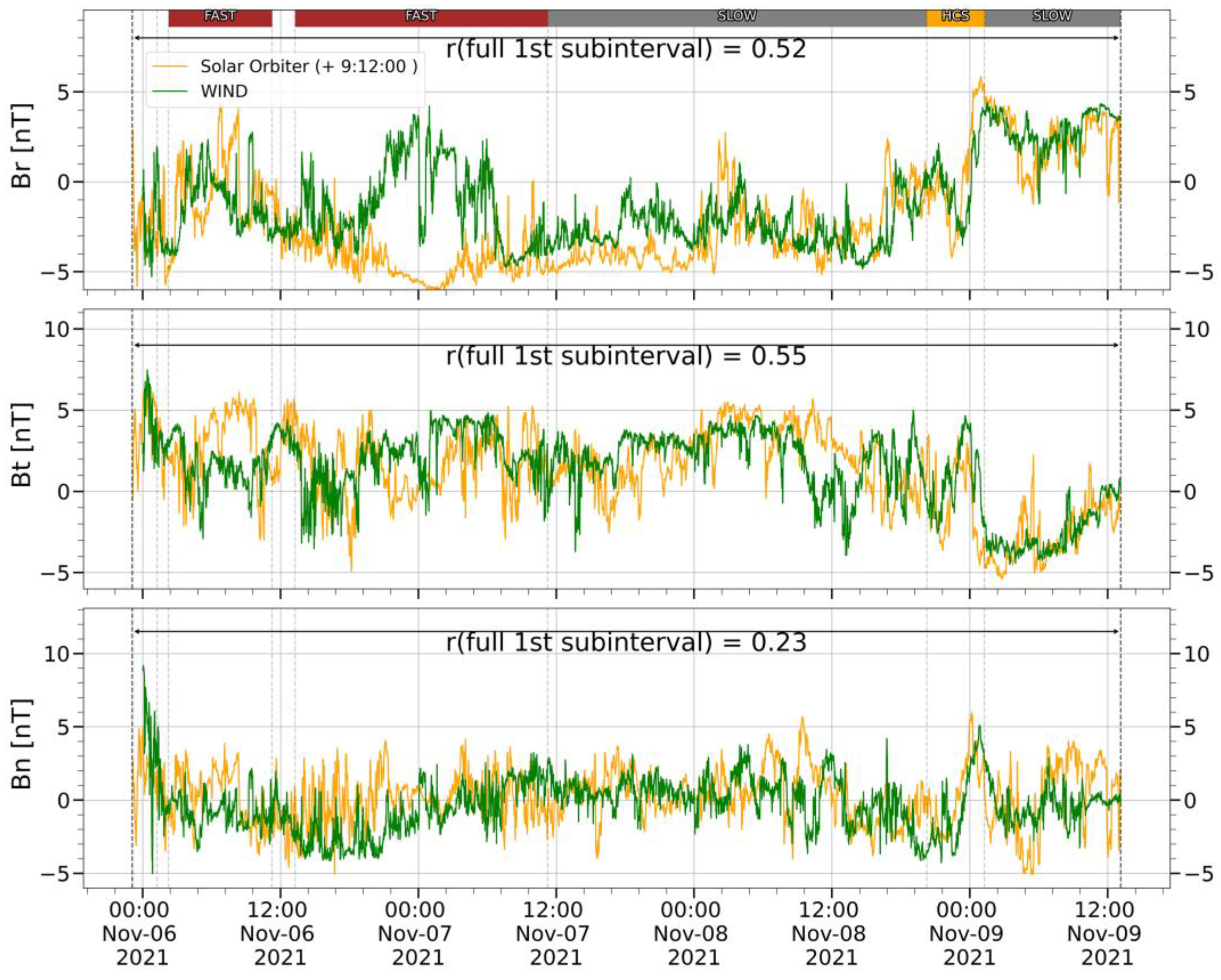

The same trend persists when considering the time series separately in each subinterval. The time shift found by correlation analysis (see related section 2.3) can be rather different from the original one, up to several hours for a sufficiently strong separation of the spacecraft. For the above subintervals at the 1

st event above with small separation in space the finalized time shifts are 9:12, 9:06 and 9:09, thus there is practically no difference in time shifts and values of correlation coefficients between subintervals, but it differs near two hours from preliminary estimation based on average bulk speed. The values of correlation coefficients for all discussed parameters after time shift clarification are shown in

Table 1.

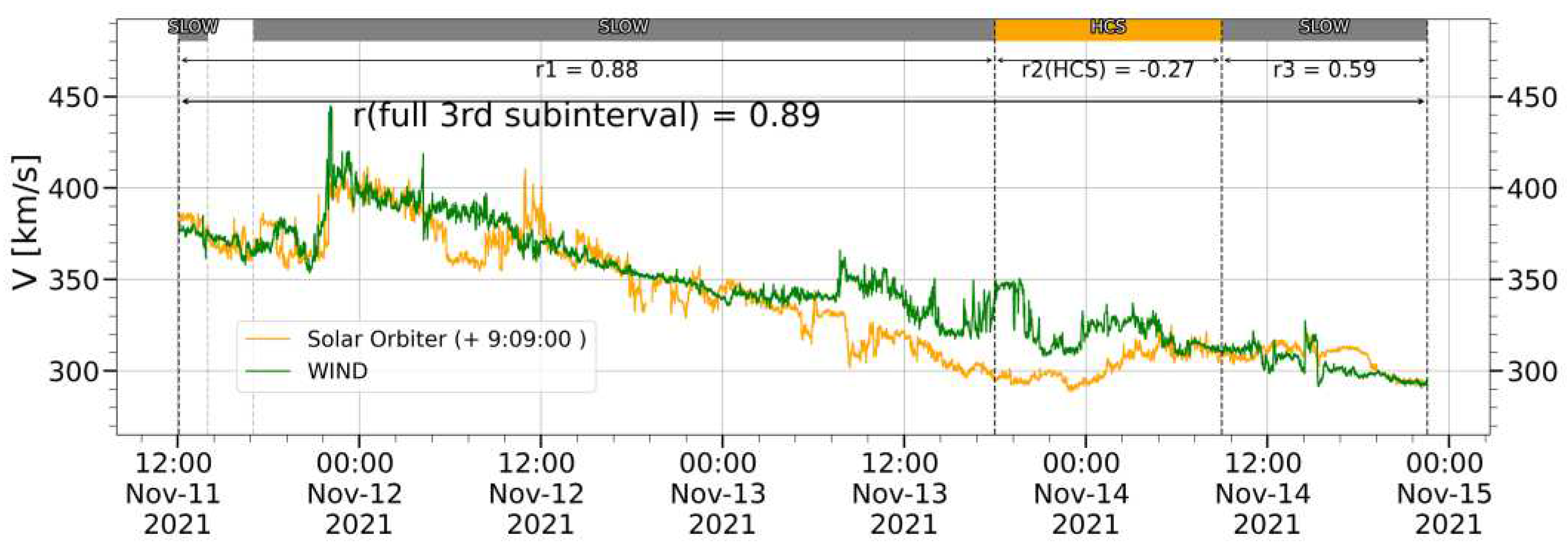

Meanwhile the level of correlation could vary significantly from one subinterval to another due presence in different types of SW. For example,

Figure 6 for the third subinterval of the 1st event shows that it is for just for the heliospheric current sheet (the middle part of the Figure) the correlation value for proton bulk speed fell to -0.27, whereas for the intervals in the slow quasi-stationary SW before and after HCS treatment, the correlation coefficient is 0.88 and 0.59 respectively.

When spacecraft are close to each other, the absolute values of the parameters usually does not change significantly, however it does not always indicate a high level of correlation. After refining the time shift of the 1

st subinterval, the correlation coefficient of radial component of IMF reaches values up to 0.52 and in case of tangential and normal components it is equal to 0.55 and 0.23 respectively (see

Figure 7). Differences and similarities in IMF parameters time series observed at small distance between spacecraft are often related to observed structures at the exact SW type. For example, for the radial IMF component there is a structure within the FAST stream on November 7 that is visible on WIND and not visible on SolO, which undervalues the correlation (

Figure 7a). In the following SLOW stream, the visual compliance is much higher.

Comparison of simultaneous observations from two distant spacecraft (0.5 AU) provides a broader picture of the dynamics of the SW. Using the initial time-shift estimate (2 days, 3 hours and 5 minutes) by Formula 2, one of the highest levels of correlation with the mean value of 0.68 was observed for the bulk speed value, as in the first case (see

Figure 8e). The second interval was also divided into three subintervals in accordance with the prominent plasma structures: sharp growth and smooth decline of the bulk speed in the first, oscillations in the second and surge after a stable section in the third. On the first subinterval (2022-03-02 21:05:00 UT — 2022-03-07 22:59:51 UT) the correlation coefficient of bulk speed is equal to 0.88, while on the second (2022-03-07 22:59:51 — 2022-03-09 08:59:51 UT) and third (2022-03-09 08:59:51 UT — 2022-03-12 07:11:00 UT) it drops sharply to 0.28 and -0.01 respectively (here latency corrections might be quite meaningful). At the same time, the average bulk speed value remained almost unchanged. Similar trends can be seen in the behavior of the correlation coefficient of the temperature time series (see

Figure 5g), but its absolute value decreases several times over the propagation time. The IMF magnitude also significantly decreases with increasing distance (which is quite natural), but its correlation remains relatively high. The intervals containing SHEATH, EJECTA and MC have higher IMF magnitude correlation than for FAST and HCS. The time course in SLOW streams match well but correlation is worse, while the worst match is observed in CIR stream. The correlation level for the radial component of the IMF takes lower values (see

Figure 8b), although for 0.1 AU, on the contrary, a higher correspondence of time series for this parameter was observed. The measurements of proton density illustrated in

Figure 8f demonstrate the worst compliances among all the parameters under study. In the case of 0.1 AU, that parameter also has low compliance. Time series can undergo significant distortions at analyzed distances, but some prominent structures might persist for quite a long time. For example,

Figure 8e shows that a rapid increase in bulk speed from ~300 to 650 km/s for the SolO and up to 550 km/s for WIND is observed on both spacecraft, although arrival times and the individual details of the time course after the interplanetary shock are different. Application of the corrected estimate (see section 2.4) for the third subinterval contributed to a significant increase in the level of correlation for almost all parameters (see

Table 1).

3.2. Histogram analysis

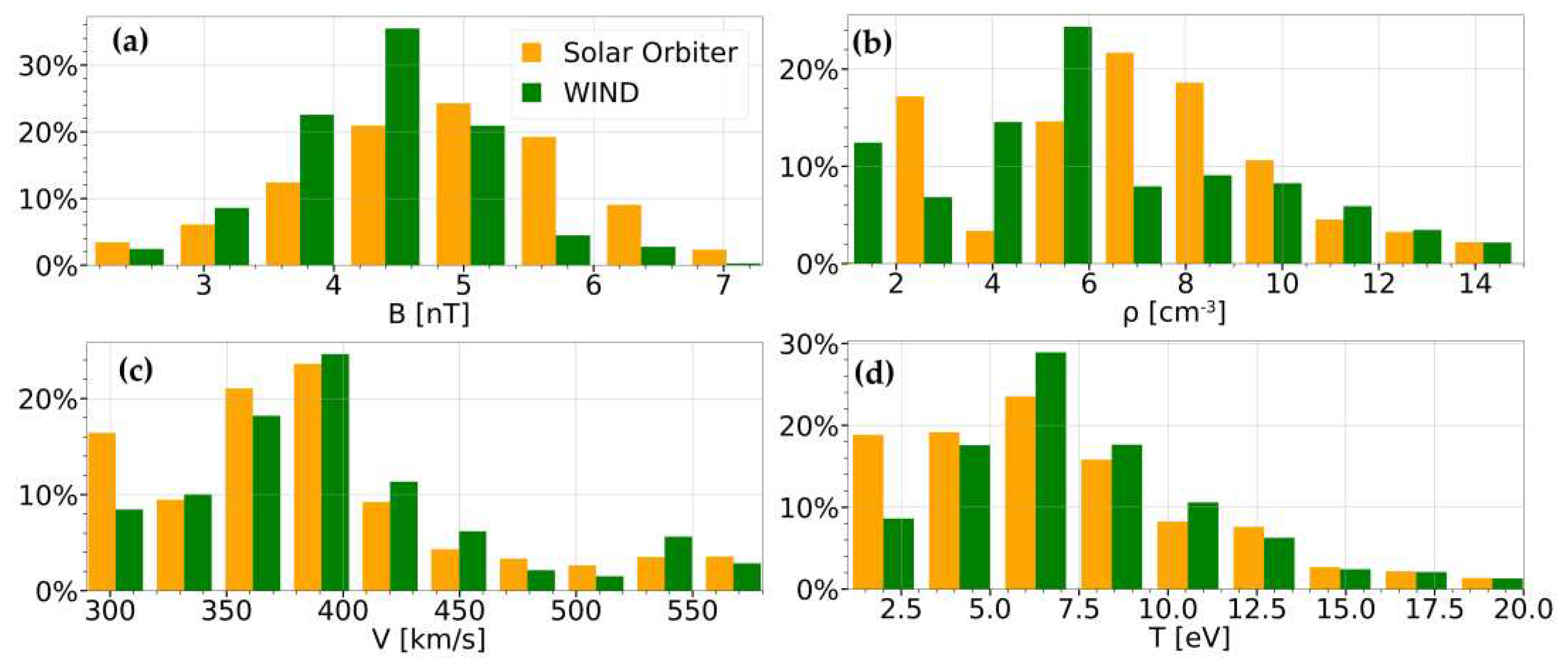

First, we studied the distributions over the whole intervals. It was shown in the

Section 3.1 that IMF magnitude and proton density demonstrate high variability when comparing data from two spacecraft even at relatively small distances (~0.1 AU). The full set of distributions for all considered parameters are presented on

Figure 9. All distributions have a fairly broad shape. A statistical comparison showed that the distributions of IMF magnitude (

Figure 9a), bulk speed (

Figure 9c) and proton temperature (

Figure 9d) change little as the SW flux advances at the analyzed distances (no more than 12% for magnetic field and temperature and no more than 3% for the bulk speed). Whereas noticeable discrepancy in the shape and basic characteristics of proton density (

Figure 9b) distributions (median values differ by ~30%) is observed. At the same time the STD, standard errors of the mean and the normalized STD, reflecting the level of fluctuations at the interval, vary weakly for all quantities. All the above statistical characteristics are presented on

Table 2.

Figure 8.

Time rows comparison of IMF magnitude (a) and its components in RTN system (b,c,d), bulk speed (e), proton density (f) and temperature observations (g) for the SolO and WIND (2

nd event). All signatures are the same as in

Figure 2.

Figure 8.

Time rows comparison of IMF magnitude (a) and its components in RTN system (b,c,d), bulk speed (e), proton density (f) and temperature observations (g) for the SolO and WIND (2

nd event). All signatures are the same as in

Figure 2.

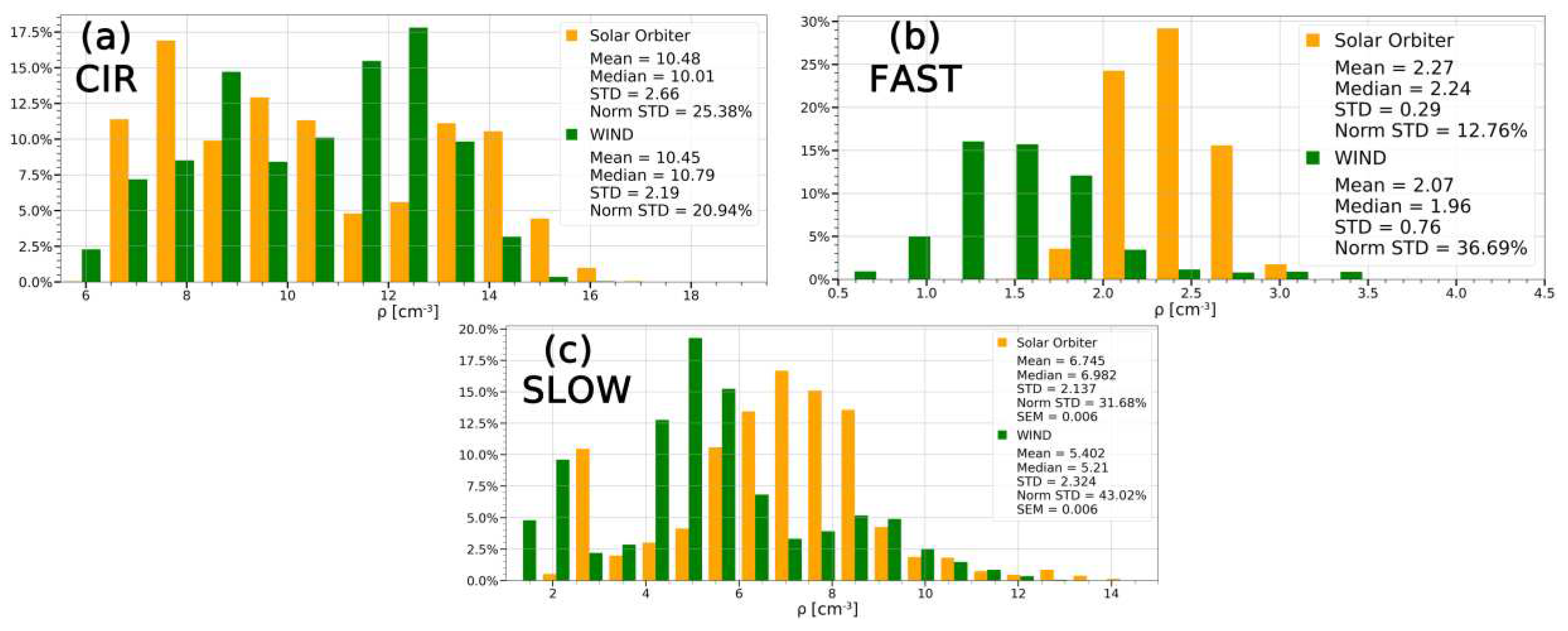

The difference observed in distributions (especially for density, as the most variable parameter) may be because distributions are common to all observed large-scale structures, so the next step was to consider the distributions for type separately. We found remarkable features examining the histograms of parameter distributions for individual SW types. For example, the density distribution for the CIR (see

Figure 10a) on the SolO has a complex shape with three peaks: the first subset of plasma with a density of ~7.5 cm

-3, the second 9.5 cm

-3 and the third 13.5 cm

-3. However, when SW reaching WIND, two peaks with maximum at ~9 cm

-3 and ~12.5 cm

-3 can be observed instead of three peaks, observed on the SolO. Perhaps two strongly interacting streams merged into one during the propagation. Note that WIND was at this moment at a radial distance of about 0.1 AU from SolO, at the same time the distance between spacecrafts in the plane perpendicular Sun-Earth line was ~10⁶ km. Thus, the difference can be also related to inhomogeneities of plasma structures in space, as we can see different part of structures at different spacecraft.

However, it should be noted that no statistical characteristics of the distributions changed significantly as for density distributions over the entire 1st event as a whole.

The density distribution in the FAST stream also behaves differently at two spacecraft (see

Figure 10b). It is noteworthy, that this type involves wide range of density values, including extremely high (not shown at histogram) compared to the average on the whole interval. So, to determine the mean and median values, the sample was limited to the range of the distribution in the figure. Two noticeably shifted maxima can be observed for density distributions on different spacecraft. The main distribution mode has a peak at 2.4 cm

-3 for SolO which shifts to 1.3 cm

-3 when approaching the WIND spacecraft.

Figure 10c present the density distributions for slow SW streams, which also have different shapes for SolO and WIND measurements, and differs from the distributions for CIR and FAST. These distributions also have a complex shape with several peaks, which suggests that not only large-scale structures can determine the shapes of distributions, but also their medium-scale substructures.

Thus, the statistical distributions for the density can change significantly even during the plasma motion time of ~9 hours at a distance of 0.1 AU and these changes might be different in various types of SW streams. That feature is specific to the proton density, such noticeable differences in statistical distributions are not observed for other observed parameters.

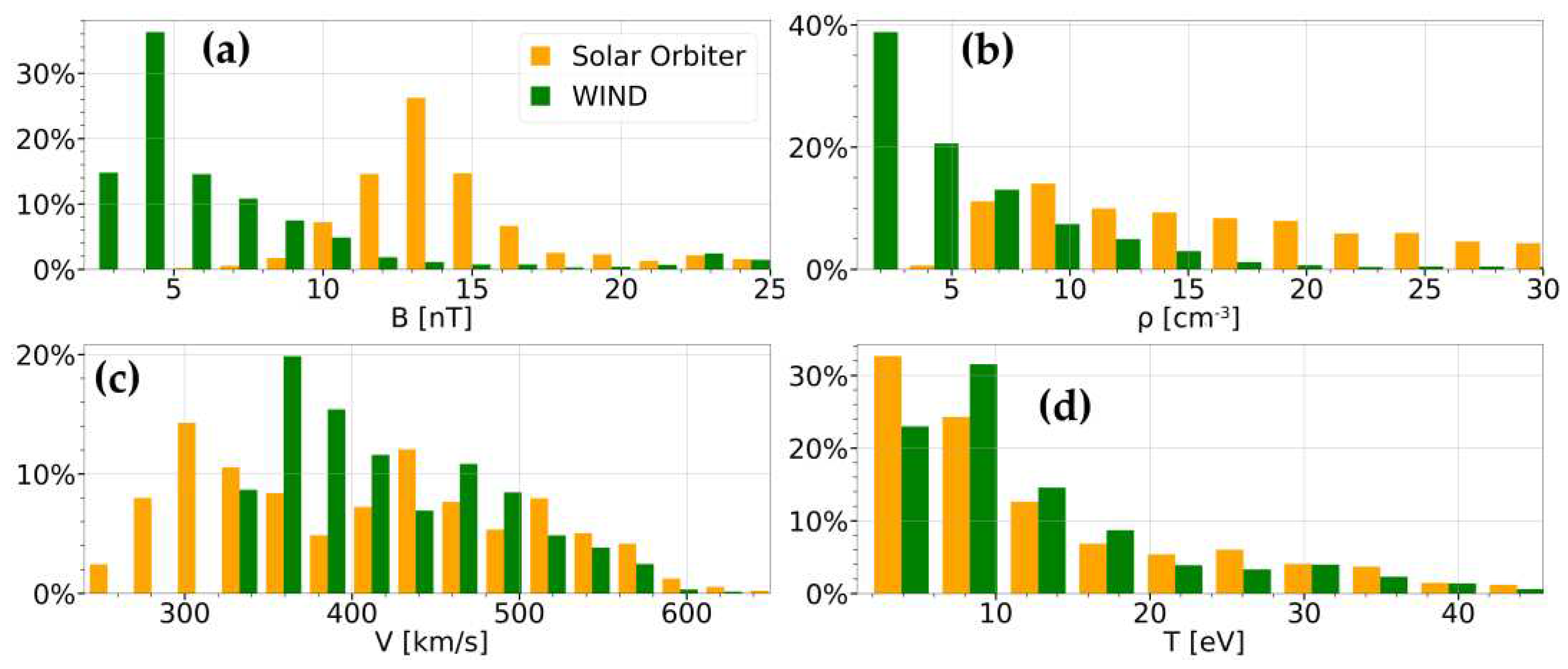

For the second event (0.5 AU between spacecraft), the histograms of the distributions are expectedly differ significantly depending on the parameter (see

Figure 11 and

Table 2). The distributions for the proton temperature were closest, even though its measurements on the SolO had a large scatter and reached 150 eV (the extreme values are rare and not shown in the

Figure 11d). The bimodal bulk speed distribution (

Figure 11c) registered at the SolO became more uniform when the flow reached WIND. These differences may also be due to the specifics of the measurements. The values of all statistical parameters remain approximately at the same level for the bulk speed and proton temperature by observation on both spacecraft (see

Table 2). The histograms for the IMF magnitude (

Figure 11a) have a clear similarity in the shape, but with significant shifted absolute values of the distribution maximum (mean and median values respectively), which is natural. However, normalized STD of IMF magnitude differs only by 20%. Density distributions (

Figure 11b) have still the greatest differences in both shape and all statistical parameters (see

Table 2, column 4 and 5). Despite the differences in distributions, normalized STD differs by only 25% on average but unlike other parameters for which the normalized STD decreases at 10-20% as the SW approaches the Earth, the STD for density, on the contrary, increases, i.e. the relative level of density fluctuations become greater.

In the case of proton density and the IMF magnitude, it is natural to observe significant differences in mean values, but the values of normalized STD, characterizing the relative level of fluctuations, change weakly for almost all observed parameters. Note that based on the value of the normalized STD, the level of fluctuations decreases slightly for all parameters except proton density, when SW moves to the Earth orbit. Whereas the relative density fluctuation on the contrary increase. Changes in the amplitudes of the analyzed parameters for spacecraft spacing 0.5 AU agree with the data in the existing models of SW propagation.

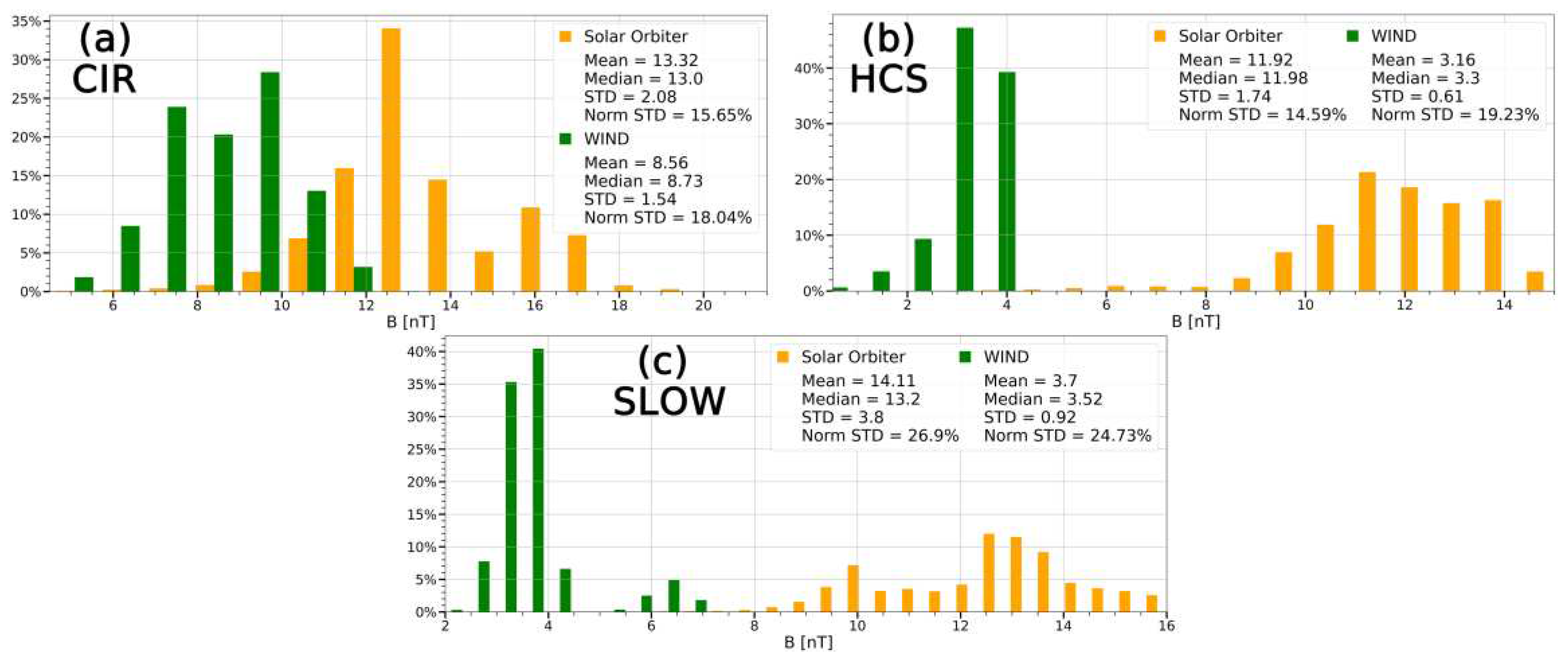

Consider the differences in statistical distributions on individual types of SW, as it was produced for previous interval, a number of peculiarities can be highlighted for the 2th event. For example, the IMF magnitude distribution in CIR streams (see

Figure 12a) on SolO has a large peak and slight elevation, while on WIND, two peaks close in their values. However, the mean and median values differ less than for the same distributions of SW as a whole (

Figure 11a). At the same time the other statistical parameters (the basic and normalized STD) are close for these two distributions and rather small values.

As the SW moves away from the Sun, it experiences various interactions with the surrounding space, which might affect its characteristics. It can be more pronounced for some types of SW. For example, distributions of IMF magnitude in HCS (see

Figure 12b) have undergone significant changes both in form and in typical values. However normalized STD and STD parameters still remain at approximately the same level.

The distributions in slow SW (see

Figure 12c) show again complicated picture with two distribution peaks (reflecting two plasma subsets). Wherein the relative positions of the peaks among themselves are preserved, but the role of each peak change - for SolO the main peak is posed at 13 nT, and the less pronounced peak is posed at 10nT, and for WIND oppositely the main peak have lower value ~3.5 nT, and the less significant peak has higher value~ 6.5 nT.

The analysis of the histograms for all types of SW showed that the greatest changes occur in SLOW, HCS and ICME (MC) streams. However, these conclusions are only preliminary, since a relatively small amount of statistical data has been collected so far for different SW types.

3.3. Fluctuation analysis

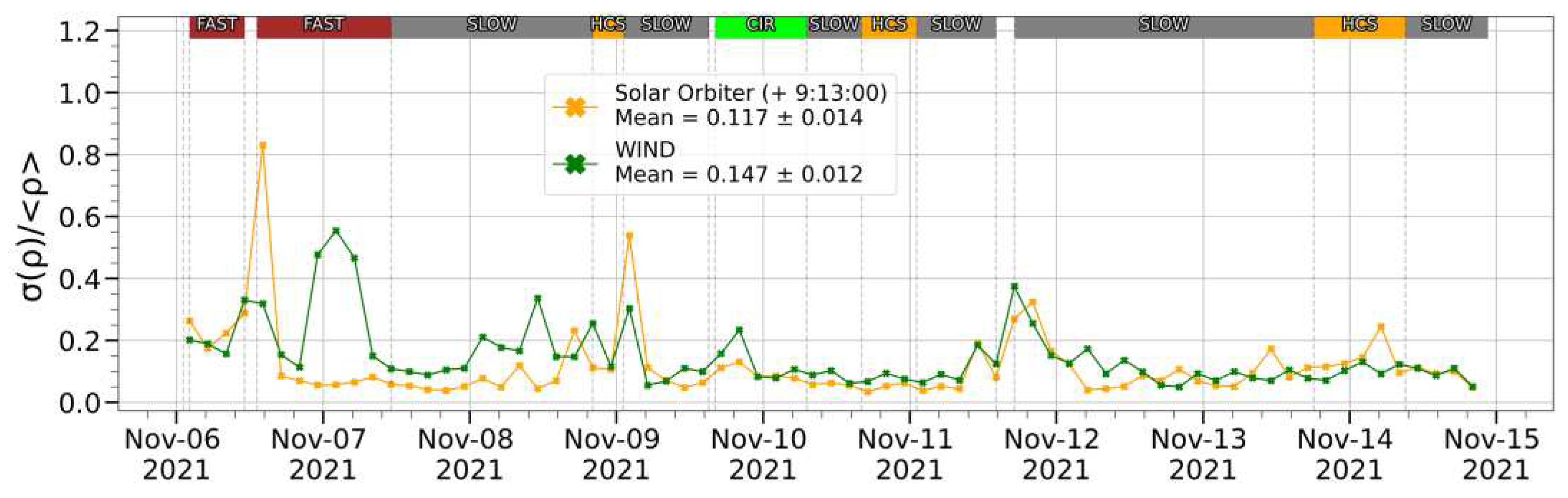

Analysis of the fluctuation level and its dynamics is an important step in the study of the evolution of SW structures. It was shown above that a noticeable change in the absolute value of the proton density might occur even at a small distance between spacecraft (0.1 AU). Nevertheless, the level of fluctuations (RSD values) and their time course are preserved at both selected events, and the observed changes are usually related to the type of the SW stream, as it was shown above. For example,

Figure 13 shows the time course of the local normalized standard deviation (see the section Materials and Methods) of proton density for the first interval. One can see that in general the level of fluctuations is rather close on both spacecraft (with a difference of ~25% in average, while the fluctuation range in the observed fluctuations at each spacecraft is >500%). At the same time, some large-scale structures (FAST, HCS and CIR) a simultaneous increase in the level of fluctuations and the amplitudes of these increases are also close (with a difference of ~25%). However, for the FAST stream on November 7, in contrast, a noticeable difference is observed - the large peak of local normalized standard deviation for density can be seen on WIND data at 07/11/2021 ~ 04:00, however, it is not so by SolO data. This is due to the density structure, which is observed on WIND measurements and do not observe at SolO one (see

Figure 5).

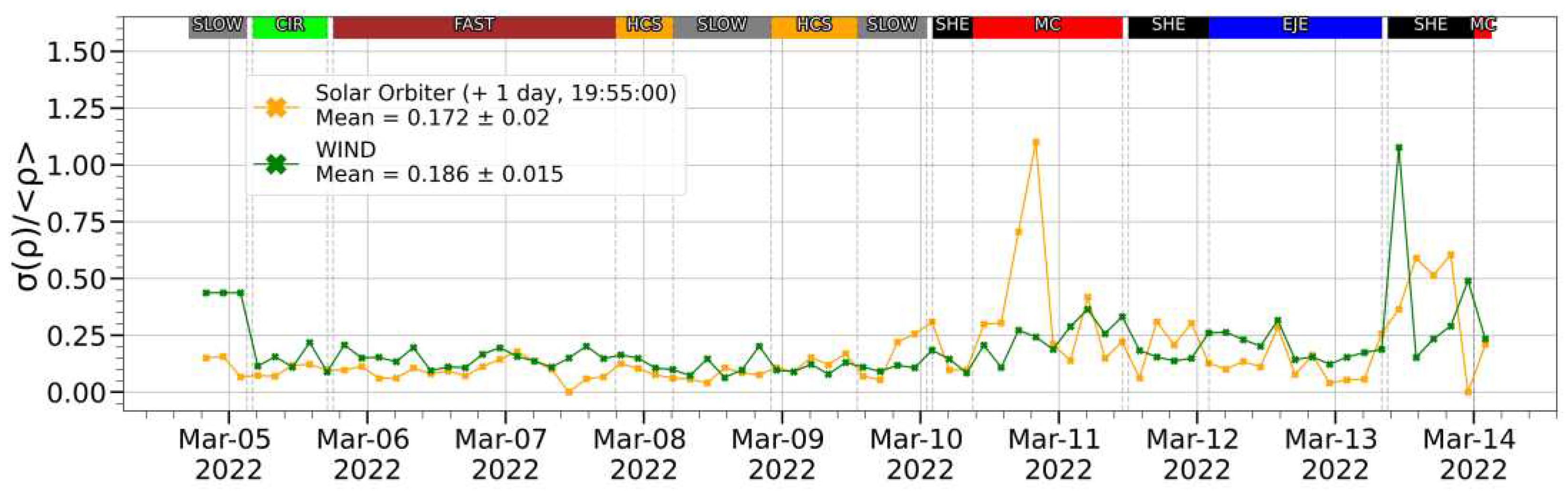

At a distance of 0.5 AU, there is a generally similar situation. It was shown earlier that significant changes in the absolute values of the parameters are possible, especially for IMF and proton density with increasing distance. Nevertheless, a weak change of local levels of fluctuations was observed for all of the studied SW parameters. In particular, the time course of the normalized standard deviation has similar and almost a point match at some places behavior for both spacecraft close (with a difference of 8% in average. It is significantly less than the fluctuation range on a single spacecraft equal more than >1000%), even for density of protons, which was the most variable parameter (see

Figure 14). The time moments when a difference in the level of normalized standard deviation is visible is usually associated with some local structures observed on one spacecraft and not observed on another or observed with changing. For example, in the vicinity of magnetic cloud and interplanetary shocks occurred the greatest normalized standard deviation differences reaching values of 450%, which is still less than the fluctuation range on single spacecraft.

We have given a detailed comparison for density as the parameter with maximum level of fluctuations. For other parameters the situation for fluctuations is similar.

This result is consistent with the behavior of the fluctuations in case of the first event. In both cases, certain types of SW significantly increased the overall difference in mean values. For that reason, we can conclude that the level of local fluctuations almost does not change when the wind moves from the Sun to the Earth. However, it can vary for different types of SW (according to observations simultaneously on two spacecraft), an also for some local structures (observed on one of the spacecraft). Such local structures can be observed even in case of small distance between spacecraft, so it’s the result of spatial inhomogeneity of the SW, rather than evolution during movement.

3.4. Analysis of the 4th order moment of the PDF

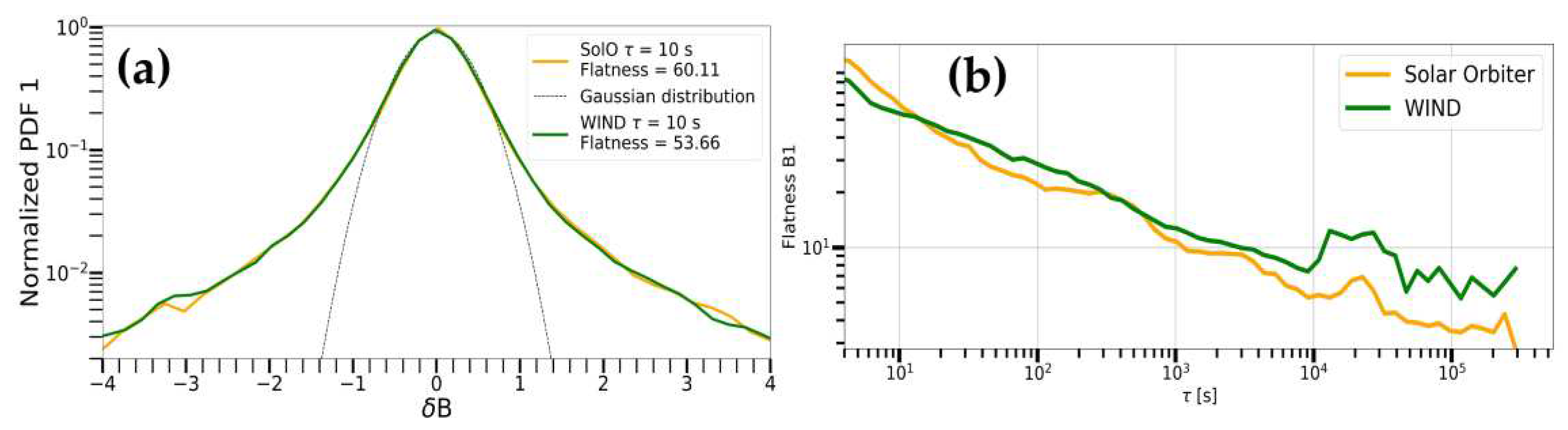

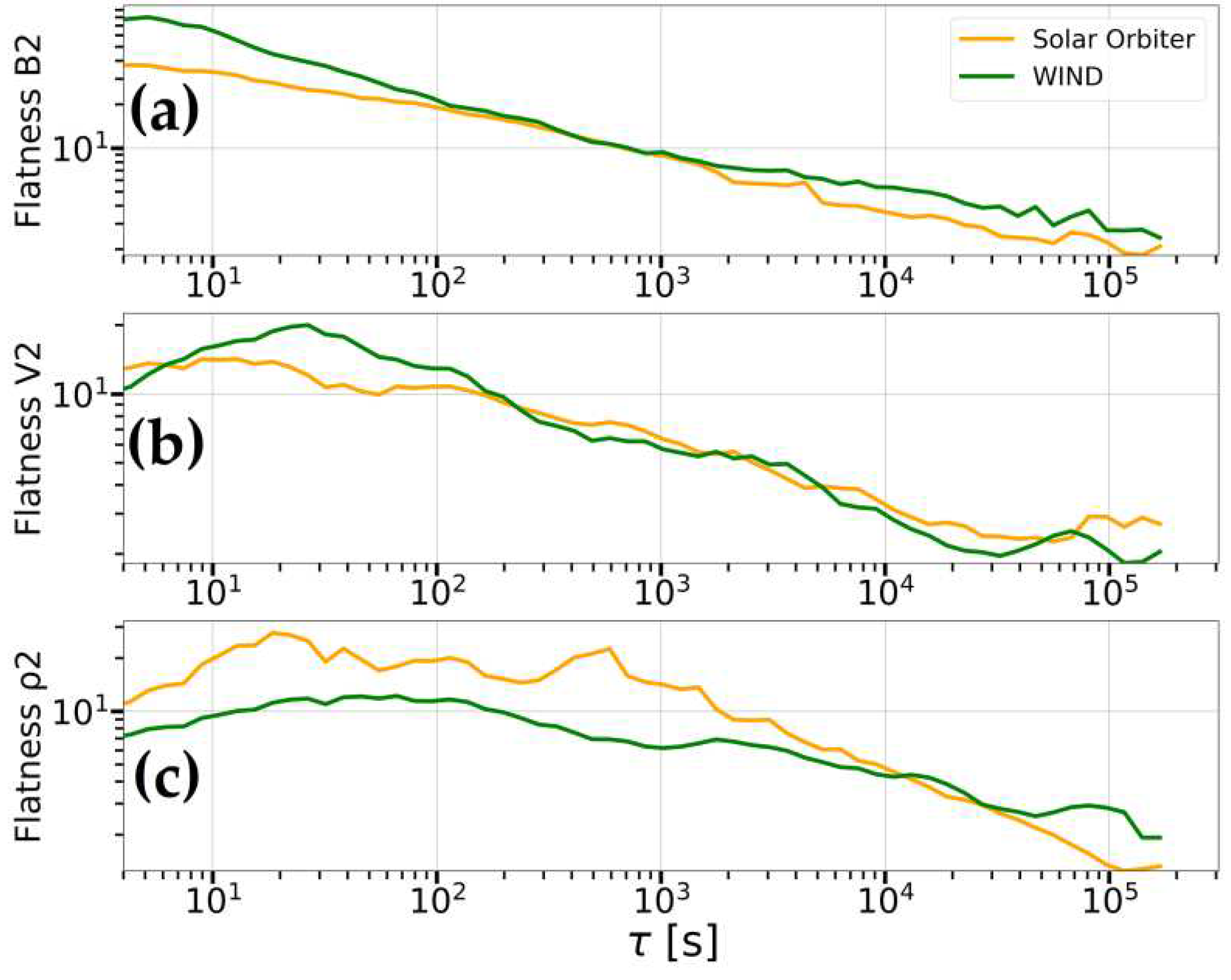

In addition to the quite high coincidence of the amplitude and time course of the fluctuations of the SW parameters on different spacecraft, we can note that the distribution functions of the fluctuations of each of the parameters also have a similar form based on observations on both spacecraft. In this study, we analyzed the fluctuations of IMF magnitude, proton density and bulk speed.

Figure 15 presents that the dependences of the flatness on the time scale at 0.1 AU has a similar character on the SolO and WIND. Overall, there is a decline of the flatness with scale, and at scales greater than 10

4 the flatness approaches three, which indicates the presence of intermittency in the discussed flows (see

Section 2.7). Moreover, the level of intermittency for all quantities remains practically unchanged for each of the three subintervals. Nevertheless, we can note some differences in the behavior of the above-described dependences for different parameters. For example, the PDF for IMF fluctuations tends to the Gaussian distribution more smoothly than for the other parameters (see, for example,

Figure 15a for the second subinterval of the first interval). However, for the density there are some differences at all scales, which is natural for such a variable parameter, wherein the trend in the 4th moment change is the same.

Flatness for the proton speed and density fluctuations persist at heliocentric distances from 0.9 AU to the libration point L1 along the Sun-Earth line. Meanwhile the variations for the IMF over scales are more uniformly distributed.

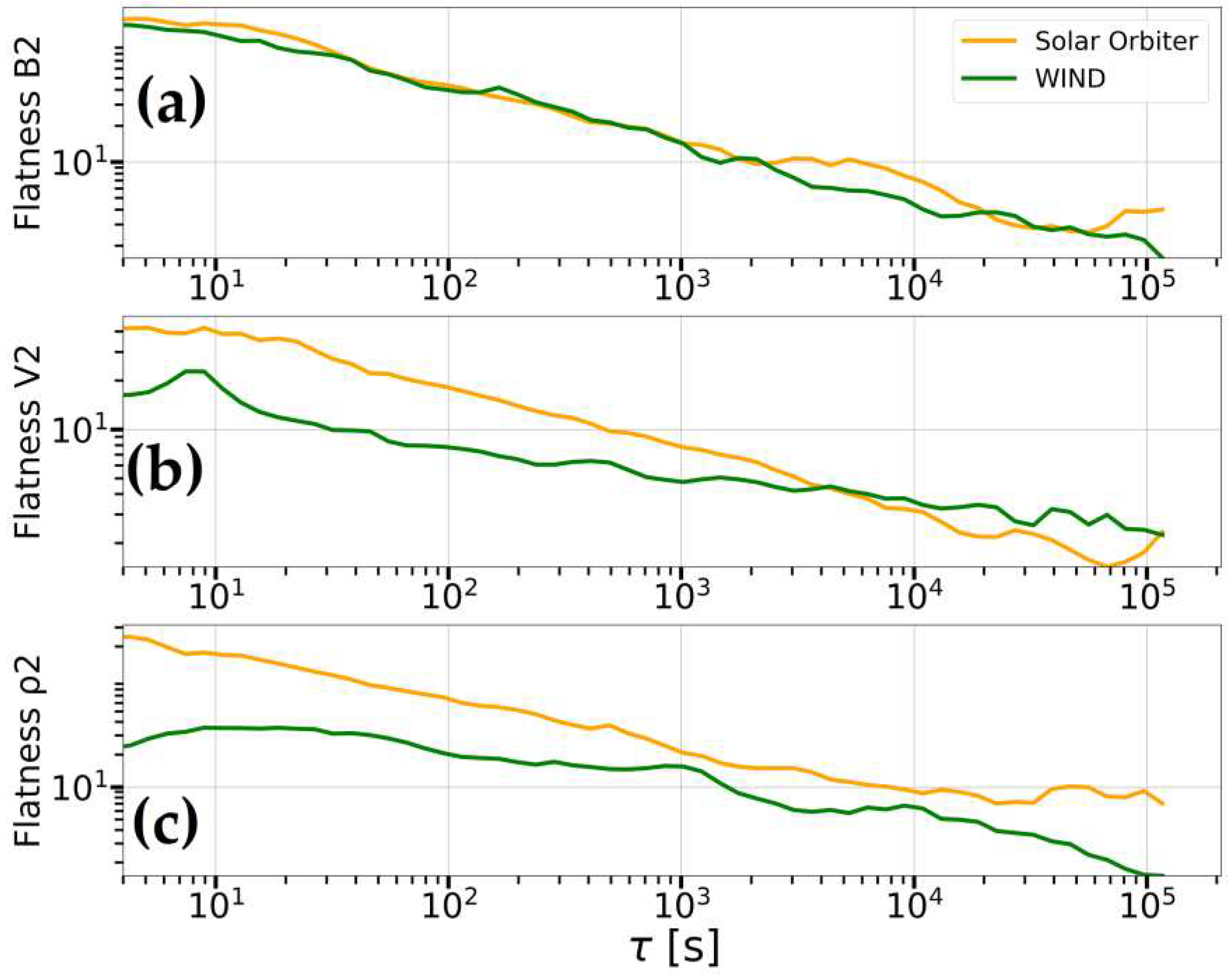

It can be noted that the character of shapes and features of the fluctuation distribution functions in the second event at a significant separation of spacecraft (~0.5 AU), in general, similar to previous event. Including the distribution function of the IMF and bulk speed fluctuations also smoothly approaches the normal distribution for both spacecraft (see for example

Figure 16 for the second subinterval of the second event). For IMF magnitude (

Figure 16a) there is an almost complete flatness match, while for bulk speed (

Figure 16b) there are discrepancies by the level of flatness. The largest discrepancy of flatness is still observed for the proton density (

Figure 16c). The distribution tails become lighter and large amplitude fluctuations become less frequent for the WIND plasma measurements. That fact might indicate a decrease in the level of intermittency during plasma propagation to the Earth. However, such tendency is observed for many but not for all intervals. The flatness, calculated on several subintervals, show a large scatter and require more in-depth analysis.

In general, a similar pattern is observed for the most intervals. As a result, we can conclude that the characteristics of intermittency, one of the characteristics of the turbulent SW flow in general vary weakly with distance for most parameters. Nevertheless, for in some parameters in some subintervals these differences can be significant, which requires more depth research.