1. Introduction

The stapler is the most commonly used surgical instrument for cutting and suturing tissue in minimally invasive surgery, especially in laparoscopic surgery [

1]. Compared with handsewn methods, anastomoses with a stapler have the advantages of simpler operation, shorter operation time, and fewer anastomotic leaks [

2,

3,

4].

With the development of automation technology, electric endoscopic staplers have gradually replaced mechanically driven manual staplers and to some extent solved the muscle fatigue problem caused by repeated grasping and loosening of the manual stapler handle [

5,

6,

7]. Due to the presence of batteries, electric staplers are much heavier than manual staplers, which can also cause muscle fatigue for surgeons during use [

8,

9]. Given these factors, alleviating muscle fatigue during the use of electric staplers by surgeons is a noteworthy issue.

Wang et al. designed a novel tissue conditioning procedure based on a power stapler, which can reduce the pressure response of intestinal tissue samples [

10]. The proposed stapling instrument by Wang et al. was intended to simplify and optimize the current procedure of mechanical stapling, which was validated by ex vivo experiments with porcine small intestine segments. Kim et al. designed a new automatic compression device for the stapler, which reduces peak pressure and deformation through compression pressure control, which are important factors in compressing tissue damage [

11]. At present, many researchers have improved the design of electric staplers from the perspective of their structure or control system, as well as some from the perspective of soft tissue biomechanics [

12]. But the effectiveness of the stapler not only depends on itself, but also on the experience and fatigue experienced by the surgeon when using it.

There are still some problems to be improved in the existing electric linear stapler. Firstly, the electric stapler needs to be driven by installing a motor and a battery at the handle, which makes the electric stapler much heavier than the manual stapler. Because the surgeon needs to hold the stapler for a long time to operate, the excessive weight can also cause muscle fatigue in the surgeon's arm, making it difficult to perform the operation [

13,

14,

15]. The second problem is that currently imported electric stapler still have a manual operation part. Although the firing operation is performed by the motor, the closing of the clamping end still requires the surgeon to grip the handle [

16]. The design of this part of manual operation may cause the surgeon to vibrate slightly at the end of the stapler during operation, which affects the safety of the operation [

17].

In recent years, people have been studying how to improve the user experience of electric staplers, reduce the fatigue of surgeons during use, and improve the safety of surgery. There have been studies comparing the use of electrically powered and manual staplers. A study, conducted on ECP CDH29P (Johnson & Johnson, 2012) showed electric staplers cause less user fatigue than manual staplers, which resulted in a 37% reduction in stapler end movement [

18]. In 2012, the Kono team in Japan designed a satisfaction survey questionnaire on the use of staplers, which included satisfaction with commonly used tubular and linear staplers on the market, pressure during use, and problems with staplers [

19]. This study indicates that the commonly used imported staples on the market are not satisfactory to Japanese doctors due to discomfort in use. The team conducted a more in-depth study in 2014 on the relationship between the impact force of the stapler and the size of the hand [

20]. They ultimately concluded that the handle of the stapler should be optimized for ease of operation by surgeons. This also means that although the weight of the electric stapler cannot be effectively improved, the muscle fatigue of surgeons can be reduced by improving the difficulty of stapler operation.

In 2023, Meghan et al. collected data on the physical characteristics, difficulty in device use, device preference, and practical nature of surgeons through online surveys to study the impact of research variables on the use and preference of common laparoscopic instruments [

21]. They suggest that surgeons should carefully review the design options of laparoscopic instruments when selecting them to improve ergonomics during minimally invasive surgery. Poor ergonomic design of laparoscopic instruments can increase muscle fatigue and cause discomfort for surgeons [

22].

In order to investigate whether the design of the part of manual operation has an impact on surgeons, we consulted multiple surgeons to investigate the factors that affect surgeons' operation of staplers. According to the inquiry, this kind of design is a factor that affects the operation of many surgeons. And no further systematic studies have been conducted on how manual operation and handle weight negatively affect muscle fatigue and end movement. So we improved the design of the electric stapler to offset the problems caused by its battery weight. The main work of this study is as follows:

Improving the control of the linear stapler. Considering that electric staplers are driven by motors and batteries, it is difficult to effectively reduce their weight. But the manual part of stapler clamping end can still be improved. Therefore, we modified the closure control portion of the clamping end of electric stapler to be electrically controlled, and hypothesized that this modification would offset the negative impact of battery weight. This electric stapler is driven by an electric motor, both for the clamping operation and for the firing process. The surgeon only needs to press the appropriate button or switch to close the clamping end without the need to grip the handle.

Experimental verification of the effectiveness of the improved stapler. At the same time, in order to verify the proposed hypothesis and the effect of the designed stapler, the improved stapler and the unimproved stapler were compared experimentally. In this study, the EMG signal was measured to characterize muscle fatigue, and the movement of stapler end was measured to reflect the effectiveness of the stapler [

23].

2. Materials and Methods

According to our survey and other relevant studies, we hypothesized that the proposed improved design and weight are the main factors affecting the working effect of the stapler and surgeon's fatigue in this study.

2.1. Improved stapler

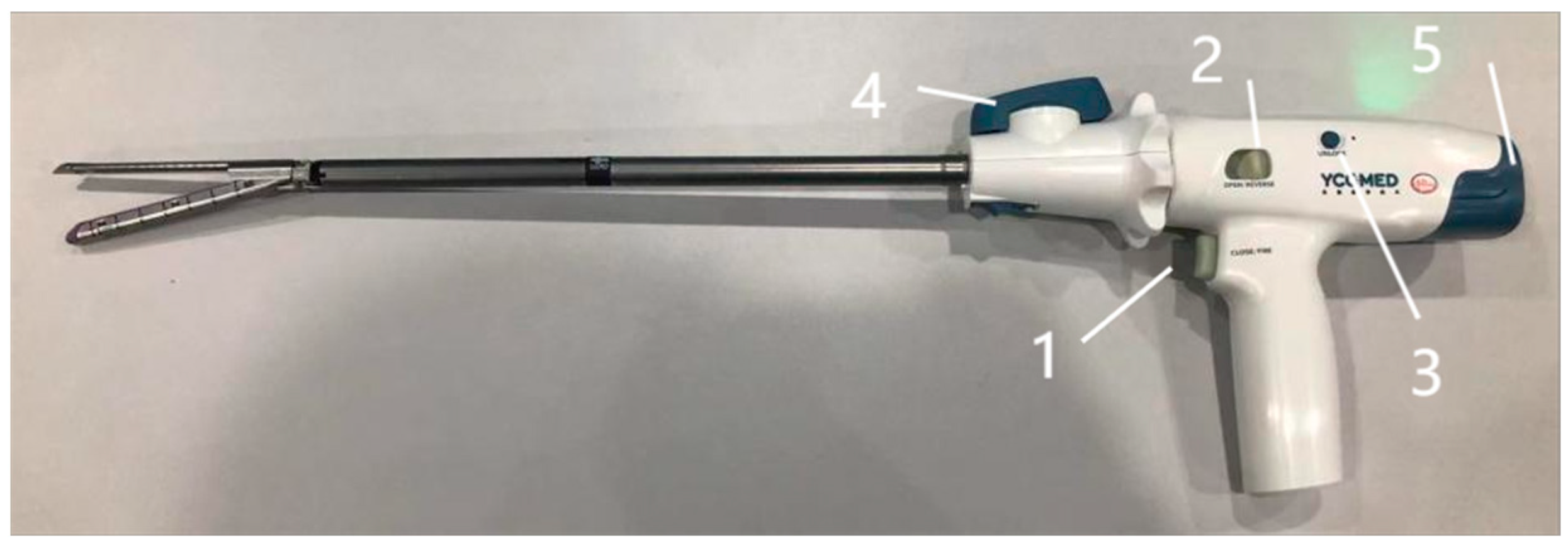

The devices tested were YCCMED

TM Powered Linear Stapler (Yuanchuang Medical Technology Co., Ltd., China,

Figure 1), and Echelon Flex

TM Powered ENDOPATH

® Stapler (Ethicon, Cincinnati, USA,

Figure 2), along with compatible cartridges: blue (closed staple height, 1.5 mm). Among them, YCCMED

TM Powered Linear Stapler is the improved electric stapler, and Echelon Flex

TM Powered ENDOPATH

® Stapler is the imported electric stapler with no improvement. The procedures were performed using the laparoscopic surgery simulation training device. The weight data for Echelon Flex™ and YCCMED™ are 582.1 g and 662.9 g, respectively. To verify whether the proposed improvements can offset the negative impact of battery weight, the modified stapler with battery was compared with the unmodified stapler without battery. Measurements of the Echelon Flex

TM Powered ENDOPATH

® Stapler were done with the battery removed during the experiment.

As shown in

Figure 1, YCCMED

TM Powered Linear Stapler is fully electrically controlled, and the clamping operation is also controlled by the motor, with the power supply section at number 5. Button 1 controls the movement of the front end actuator, press the button to close the clamping end. Button 2 can control the clamping end in the open state. After the clamping end is closed, press the safety device 3, the red light is on to carry out the firing operation, at this time, long press button 1 to complete the firing, release the button to automatically return the blade.

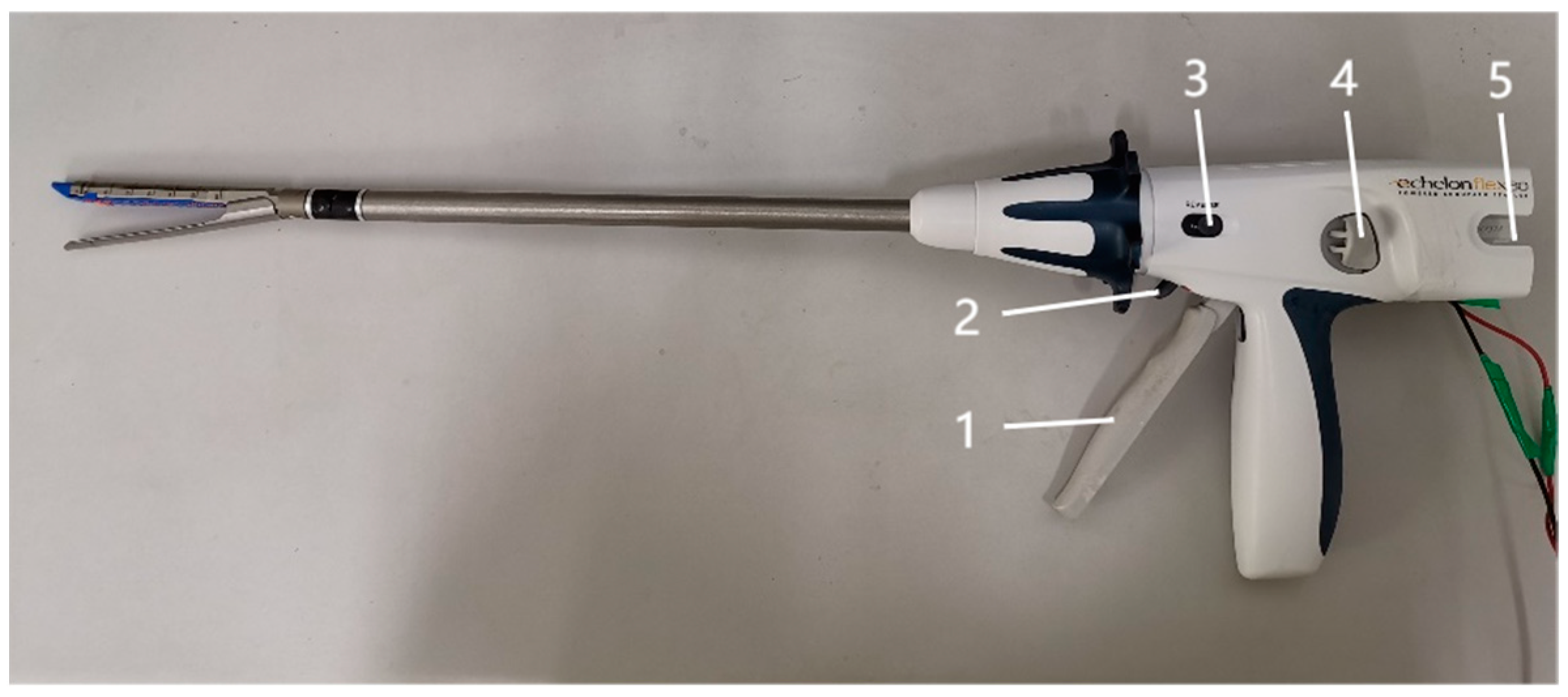

As shown in

Figure 2, EchelonFlex

TM stapler uses a DC motor to control blade movement, with number 5 being the motor power supply section (in this experiment, the power supply was removed). Number 1 is the handle, and the clamping action is still manually operated. Press number 4 to place the front actuator in an open state. There is a red safety button between handles 1 and 2 to prevent accidental operation. After pressing the safety buckle, pull the trigger 2 to complete the firing, and release the trigger to automatically retract the blade. The button at number 3 is the forced return blade button.

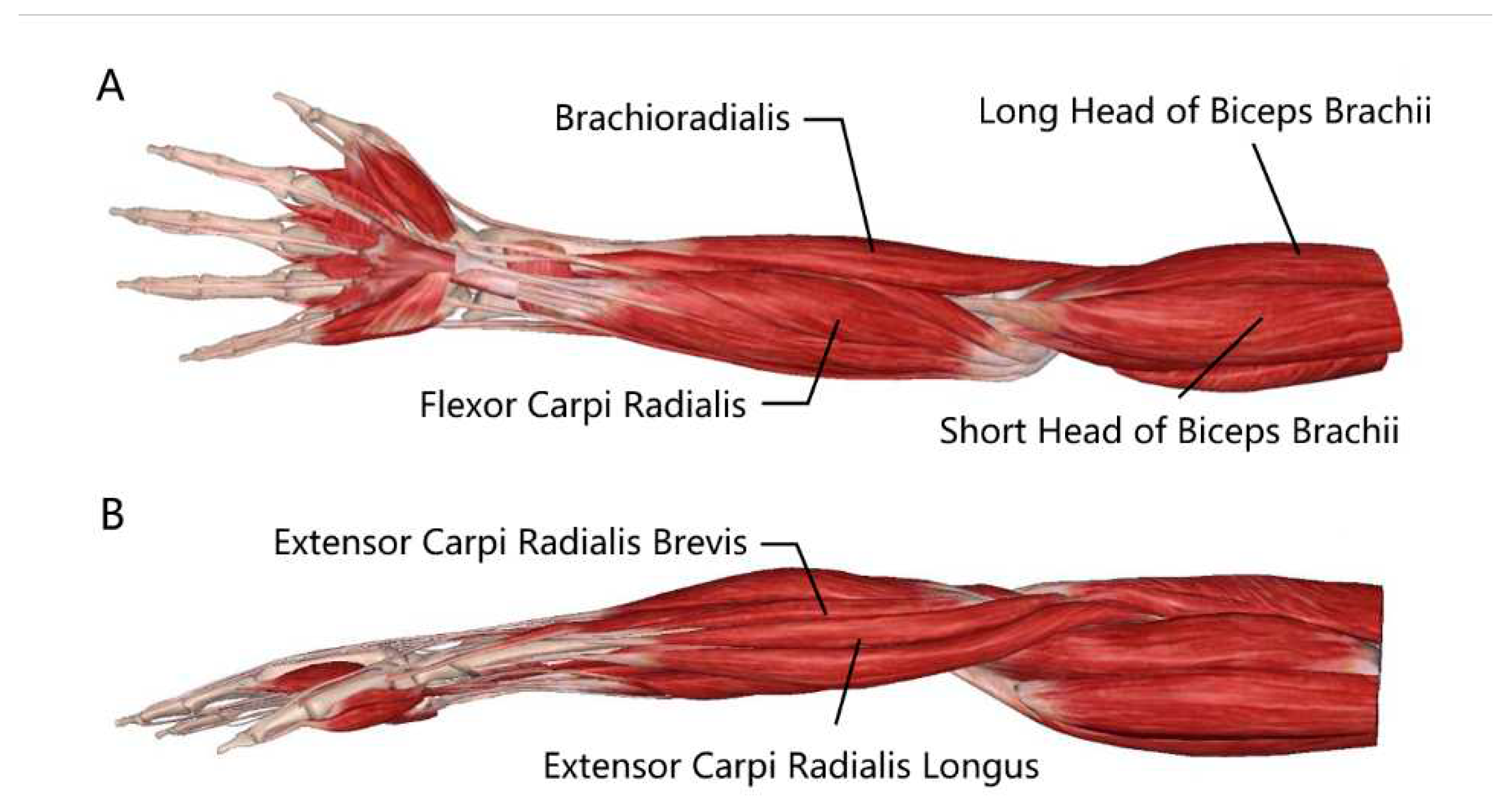

The firing operation of the stapler is completed by repeatedly gripping and releasing the handle, which is similar to a grasping action. Under the joint action of the flexor and extensor groups (

Figure 3), the grasping action is completed. Researchers used electromyographic signals to study the degree of muscle strain caused by five different minimally invasive surgical instrument handle designs during designated tasks [

24]. The design of the handle varies, resulting in differences in the muscles involved and the amount of force exerted when performing the same task, as well as differences in the electromyographic signals of each muscle.

2.2. Participants

The study is the equipment selection part of the whole project research (approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Union Hospital affiliated to Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology on December, 2020 (Ethics approval number: 2020(0585)). Recruitment was notified in the corresponding departments within Union Hospital on January 4th, 2021. Overall, 12 male surgeons specializing in gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary surgeries were selected for the research on January 25th, 2021. All participants provided verbal consent and were familiar with all the procedures of the whole project and understand the significance of instrumentation selection process. The inclusion criteria were surgeons with experience in using staplers in laparoscopic operations and those with an understanding of the use of staplers. The basic information of the subjects is shown in

Table 1.

2.3. Data acquisition

End movement measurement during anastomosis: In order to evaluate the working effect of the stapler, the stapler distal space coordinate points during anastomosis were recorded using the RealSense D435i depth camera. As shown in

Figure 4, a red color marker point was painted on the end of each stapler for the depth camera to recognize. The mean and standard deviation of the distance from each point to the center point (x,y,z) in each file was calculated using the Python third-party library NumPy, and the mean was used as a quantitative indicator of the degree of jitter.

EMG measurement: To determine the relationship between the weight and muscle fatigue, the EMG signal (DELSYS wireless sEMG signal acquisition system)was collected to reflect the muscle force exertion as well as muscle fatigue, which is supposedly affected by the weight and would in turn affect the stability of end movement [

25,

26] In this experiment, EMG signals were collected from the extensor carpi radialis, brachioradialis, flexor carpi radialis, and biceps brachii muscles of the right arm during colorectal anastomosis operation using a stapler, marked as EMG1, EMG2, EMG3, EMG4, respectively to indicate the muscle fatigue level [

27].

2.4. Experiment settings

The large intestine tissue used in this study was porcine large intestine (Wuhan Zhiling Medical Technology Co., Ltd. in No. 297, Huaihai Road, Jianghan District, Wuhan). In this experiment, freshly isolated porcine colon tissue with a relatively uniform thickness was washed and immersed in physiological saline for subsequent anastomosis.

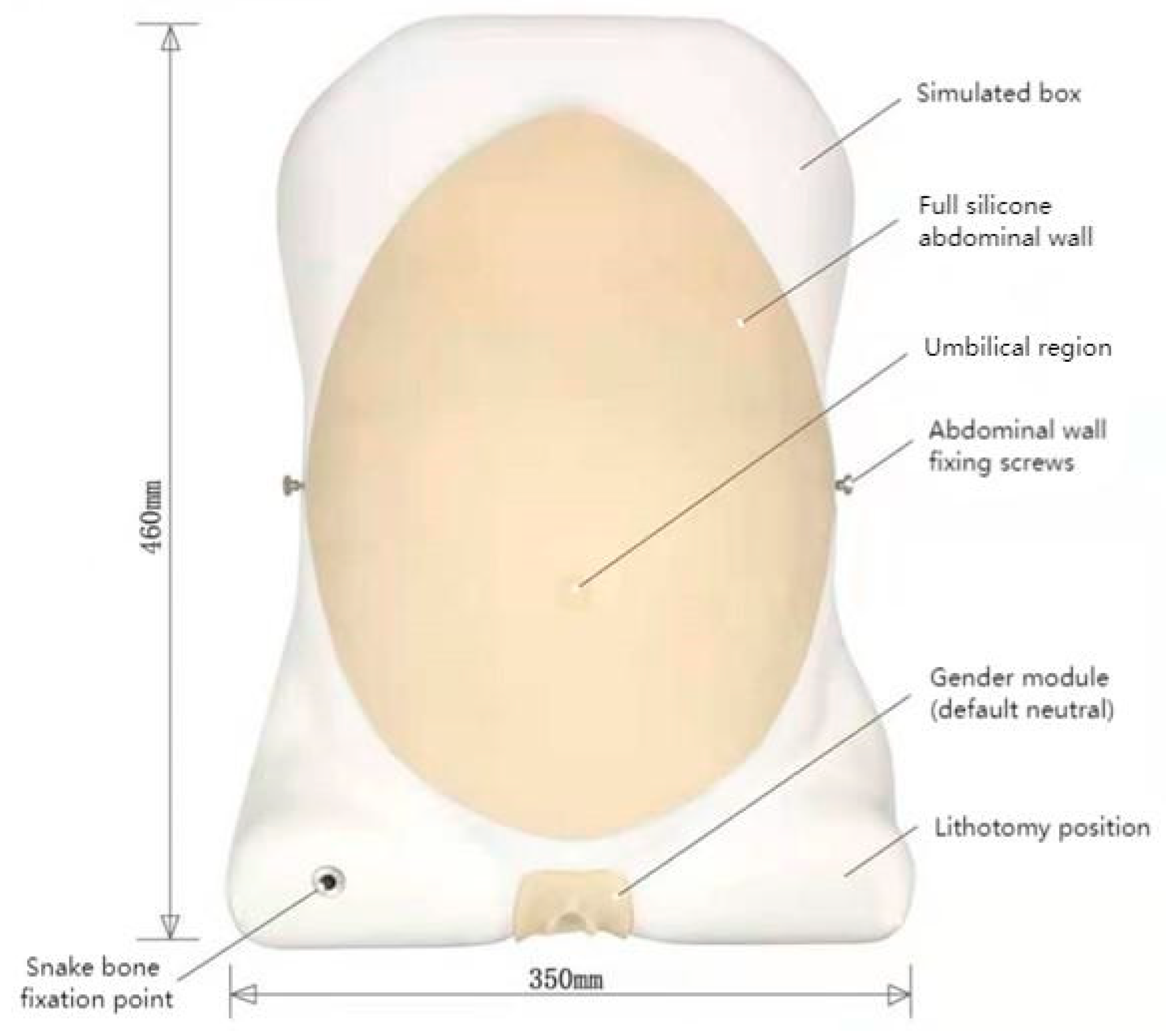

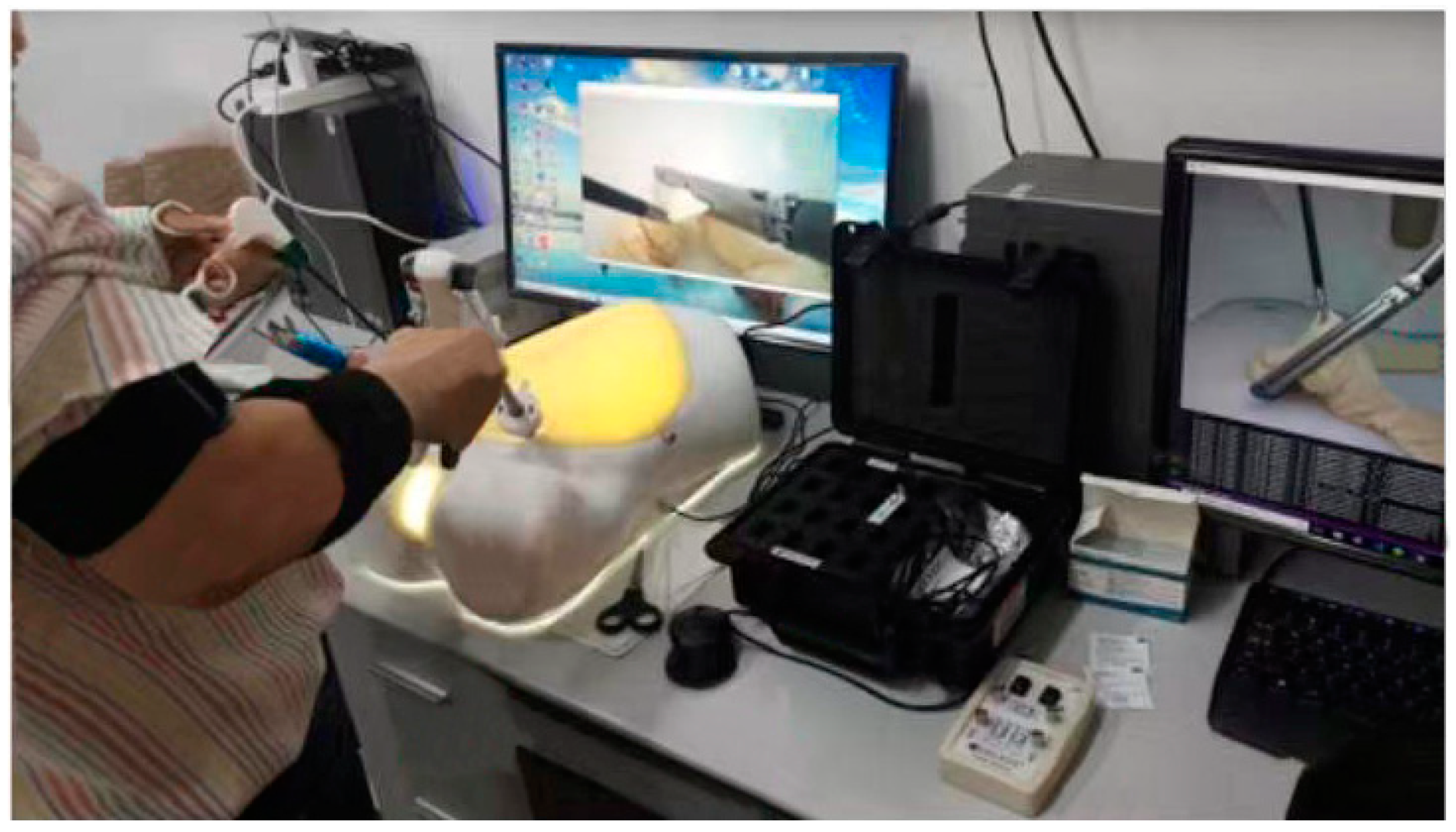

Anastomosis operations were performed using the laparoscopic trainer. The laparoscopic trainer is shown in

Figure 5, with dimensions of 460 mm × 350 mm × 180 mm, a 1:1 ratio of the adult abdomen. The laparoscopic trainer was placed on a 75-mm high experimental table, and the RealSense D435i depth camera was placed inside the abdominal cavity away from the umbilicus. Since the depth recognition distance of the depth camera was more than 10 cm, the puncture holes were punched at the lower edge of the umbilicus of the simulated belly; a total of three holes were punched. The left puncture hole was inserted into the simulated separation forceps to assist the surgeon in the anastomosis operation, the middle puncture hole was inserted into the 30-degree simulated laparoscope to assist the surgeon in observing the intra-abdominal cavity, and the right puncture hole was inserted into the endoscopic stapler for the cutting and suturing operation. The operation scene was shown in

Figure 6.

2.5. Procedures

Prior to the experiment, all participants were told about the procedures and precautions on the operations of different staplers. Wireless surface EMG sensors were then attached to the target muscles of the participant’s right arm.

Researchers provided simple operational training to participants to guide them to become familiar with the operation of the two staplers.

Before performing colorectal anastomosis, baseline shaking data of the participants needs to be collected. To start, participants were asked to operate a stapler, insert it into a laparoscopic simulator through a puncture hole and hold the staplers for 20 seconds, EMG and end movements were recorded to explore how weights influence the end movement.

The participants operated surgical clamps and staplers to complete the anastomosis of large intestine tissue, during which the researchers adjusted the laparoscopy to assist the participants in observing the intra-abdominal situation. After using a stapler to clamp the tissue, the participants must recalibrate the marker points under the guidance of the researchers, and then proceed with cutting, suturing, and retraction operations.

Then participants were asked to operate each of the two staplers twice. The order in which each participant operated the two staplers was randomly determined before the start of the experiment. After each operation, the researcher will change the nail bin for participants, who can take a short rest during the change.

The whole procedure was recorded by a video recording software. EMG data were collected simultaneously with the stapler end-motion data.

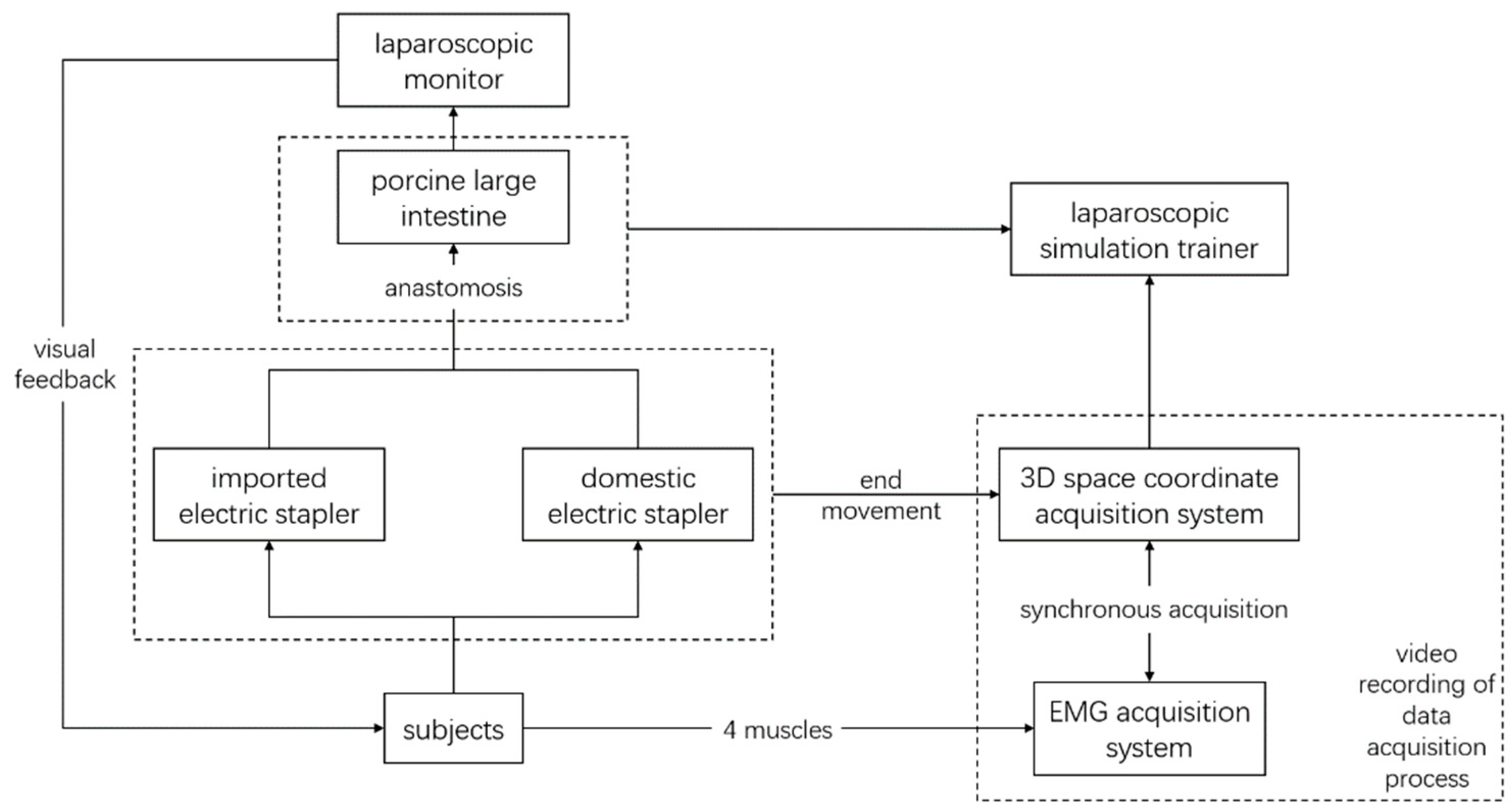

The overall framework of the experiment was shown in

Figure 7. After completing all manipulation tasks, each subject is required to provide an experience using the designed stapler as a way to assess the surgeon's perception of using the different staplers.

3. Results

3.1. End movement

The whole process of the anastomosis operation can be divided into three parts, baseline process, firing process and withdrawing process. Based on the raw data of each process, the end movement trajectory was plotted, and the abnormal points that deviated significantly from the raw data were deleted. Taking the firing process as an example, the jitter of the YCCMEDTM one is slightly higher (2.08±0.59), and the EchelonFlexTM one is lower(2.04±1.07).

The statistical description of the end-motion data during the use of the different staplers in each process is shown in

Table 2.

In order to verify and compare the working effects of the two electric staplers, the jitter data for each type of stapler during baseline, firing, and withdrawal were examined nonparametrically, and the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for a comparison of the anastomoses. Adjusted significance by Kruskal-Wallis test of jitter degree in three processes with different staplers are 0.189(baseline process), 1.000(firing process) and 0.305(withdrawing process) respectively. Significance level is 0.05, and Bonferroni correction has been adjusted for significant values for multiple tests. During the three process, no significant difference in end movement was shown between the two electric staplers.

3.2. EMG signal data

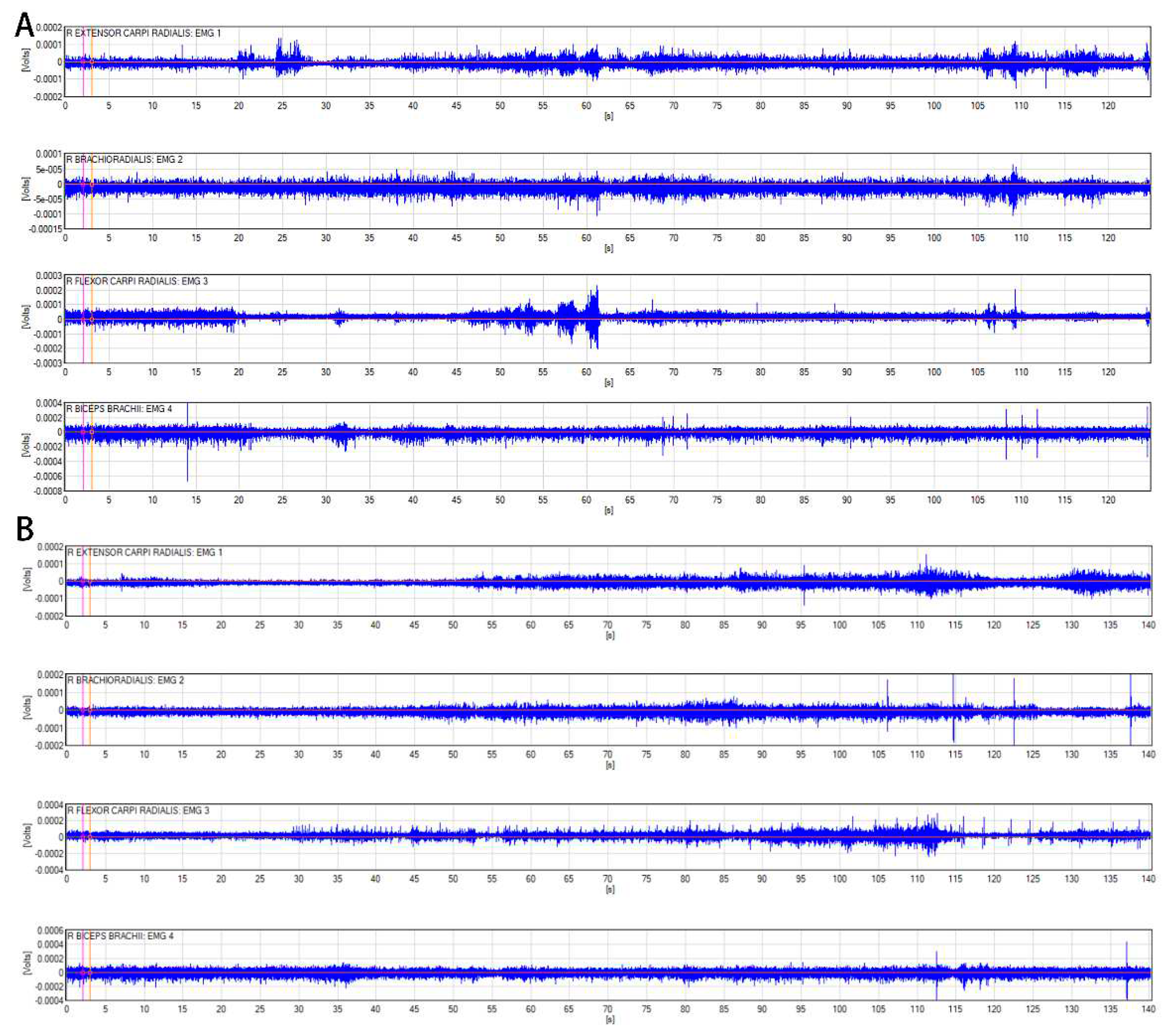

After the collected EMG signal is imported into the EMG analysis software, the EMG analysis software can display the original EMG signal in the form of a graph. Graphical examples of the original EMG signals in the EMG analysis software during the operation of the two staplers are shown in

Figure 8A and

Figure 8B.

The EMG signal was mainly represented by the magnitude and variation of the root mean square RMS value. The RMS(root mean square of electromyographic signals) value was calculated using EMG analysis software, where the data analysis window is 0.125 s. Since each file was recorded for different lengths of time, normalization of the EMG signal was achieved by calculating the sum of the RMS of each sensor in each file divided by the total time after the file splitting was completed.

With the same sample size of jitter data, a total of 24 cases of myoelectric data from Echelon Flex

TM Powered ENDOPATH

® Staplers, and 23 cases of myoelectric data from YCCMED

TM Powered Linear Staplers were collected. The statistical descriptions of the myoelectric data of the four muscles during the use of different staplers for each process are shown in

Table 3.

From the results of EMG data, it can be seen that the signals of EMG1 and EMG4 of the two staplers are very similar in the three processes, which means that the fatigue effects of the two staplers on the extensor carpi radialis and biceps brachii are similar. In addition, during these three processes, the EMG data measured by the YCCMEDTM stapler's EMG2 was always lower than that of the EchelonFlexTM stapler, while the EMG data measured by EMG3 was always smaller for the EchelonFlexTM stapler. This indicates that the YCCMEDTM stapler always causes less muscle fatigue to the brachioradialis muscle than the EchelonFlexTM stapler, and it also causes greater muscle fatigue to the radial wrist flexor muscle than the EchelonFlexTM stapler.

3.3. Usage experience

The experience of participants discussing after the experiment showed that almost all surgeons had some degree of muscle soreness after completing the experimental operation, which was caused by the weight of stapler handle. Most surgeons agreed that the improvements in YCCMEDTM Powered Linear Stapler have made the procedure more convenient and that the lack of need to grip the handle to close the clamping end makes it more comfortable for the surgeon to operate.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of the proposed improvement on end movement

According to our hypothesis, modifying the clamping end of the stapler to be electronically controlled could offset the negative impact of the additional weight of the battery on end movement. Therefore, in this study, the improved electric stapler(YCCMEDTM) was directly compared with an unimproved electric stapler(Echelon FlexTM) with no battery. In this case, if the obtained experimental result is that the jitter of YCCMEDTM is less than or equal to the jitter of Echelon FlexTM, then this improvement can be considered as an efficient design.

From the jitter data in

Table 2, it can be seen that there is no huge difference in the end jitter generated by the two staplers during use. Especially during the firing process, the jitter data of the two staplers are very close, almost the same. However, whether there is a significant difference between the two groups of data still needs to be proved by mathematical statistics. The Kruskal-Wallis test compares the jitter degree of the two staplers in the three processes. The results showed that there was indeed no significant difference in the degree of jitter between the two staplers. The reason might be that the improved end movement might be offset by the increase in jitter caused by the additional battery weight of the electric stapler. With the heavier weight, the YCCMED

TM stapler still maintained jitter data similar to that of the EchelonFlex

TM stapler. This indicates that future experiment could be designed to make the weight of the handle as constant and comparing the jitter. And according to the usage results, this design of the YCCMED

TM stapler is better suited to the needs of Chinese surgeons.

At the same time, the stapler designed in this study still has shortcomings. Although it can almost offset the impact of weight after improvement, it does not have enough attractive progress in performance. This improved design can be used as an idea, and the control system needs to be further optimized on the basis of it.

4.2. Different muscle fatigue caused by the two staplers

It can be seen from the EMG images in

Figure 8A and

Figure 8B that among the signals collected by the four sensors, the signals of EMG1 and EMG4 of the two staplers are very similar. This means that the effects of the two staplers on radial carpal extensor and biceps brachii are similar. The RMS data in

Table 3 can also illustrate this point, the difference is mainly in the brachioradialis and radial carpal flexor measured by EMG2 and EMG3.

Given the heavy weight of the YCCMEDTM stapler, the muscle fatigue it caused should have been greater. However, the two staplers caused similar fatigue on the radial carpal extensor and biceps brachii muscles. What’s more, during the three processes, the EMG data measured by EMG2 is always lower for YCCMEDTM stapler than for EchelonFlexTM one. Therefore, the improved design of the stapler proposed in this study may be helpful to alleviate the surgeon's muscle fatigue.

Interestingly, the EMG data measured by EMG3 is always smaller for the EchelonFlexTM stapler. This phenomenon may need more experiments and research to explain. The possible reason is that due to differences in the operation methods of the improved stapler, it may lead to changes in the force release mode of the radial wrist flexor muscle corresponding to EMG3.

All in all, the improved stapler can almost offset the impact of weight after improvement and be helpful for surgeons' muscle fatigue. But the muscle fatigue caused by electric staplers to surgeons has not been completely eliminated. Based on the design of this improved stapler, it is necessary to further optimize the weight of the electric stapler through ergonomics to make the surgeon more comfortable when using it.

5. Conclusions

According to the needs of Chinese surgeons, this study proposes an improved design of the electric endoscope stapler for the end movement and muscle fatigue caused by the use of the electric endoscope stapler. In the meanwhile, it has been shown through experiments that the electric stapler we designed is effective and can meet the operational needs of Chinese surgeons. It was also demonstrated that by improving the autonomy of the opening and closing of the ends, it is possible to offset the increased jitter and muscle fatigue of the electric stapler due to the extra battery weight added to the handle. However, due to the impact of weight, the operating effect of this stapler is still not much different from that of the EchelonFlexTM stapler. The designed stapler needs to further reduce the weight and improve the precision of the electric module control in order to more effectively improve the simplicity and safety of operation.

References

- Shikora SA, Mahoney CB. Clinical Benefit of Gastric Staple Line Reinforcement (SLR) in Gastrointestinal Surgery: a Meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2015;25: 1133–1141. [CrossRef]

- Luglio G, Corcione F. Stapled versus handsewn methods for ileocolic anastomoses. Tech Coloproctol.2019;23: 1093-1095. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Q, Li Z, Zhu M, Ding B, Xu J, Shen Y. Design and Performance Evaluation of a Novel Automatic Stapling Device for Knotless Barbed Suture in Laparoscopic Surgery. Surgical Innovation. 2023;30(5):657-660. [CrossRef]

- Salyer C, Spuzzillo A, Wakefield D, et al. Assessment of a novel stapler performance for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2021;35: 4016–4021. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Duarte FJ, Sánchez-Margallo FM, Martín-Portugués ID, Sánchez-Hurtado MA, Lucas-Hernández M, Sánchez-Margallo JA, et al. Ergonomic analysis of muscle activity in the forearm and back muscles during laparoscopic surgery: influence of previous experience and performed task. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013;23: 203-207. [CrossRef]

- Kimura M, Terashita Y. Superior staple formation with powered stapling devices. Surg Obes Relat Dis.2016;12: 668-672. [CrossRef]

- Miller DL, Roy S, Kassis ES, Yadalam S, Ramisetti S, Johnston SS. Impact of powered and tissue-specific endoscopic stapling technology on clinical and economic outcomes of video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy procedures: A retrospective, observational study. Adv Ther.2018;35: 707-723. [CrossRef]

- Horeman T, Dankelman J, Jansen FW,van den Dobbelsteen JJ. Assessment of laparoscopic skills based on force and motion parameters. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng.2014;.61: 805-813. [CrossRef]

- Szeto GPY., Poon JTC, Law WL. A comparison of surgeon's postural muscle activity during robotic-assisted and laparoscopic rectal surgery. J Robot Surg.2013;7: 305-308. [CrossRef]

- Wang HC, Ge WM, Liu CX, Wang PY, Song CL. Design and performance evaluation of a powered stapler for gastrointestinal anastomosis. Minimally Invasive Therapy & Allied Technologies. 2022;31(4): 595-602. [CrossRef]

- Kim JS, Park SH, Kim NS, Lee IY, Jung HS, Ahn HM, Son GM, Baek KR. Compression Automation of Circular Stapler for Preventing Compression Injury on Gastrointestinal Anastomosis. Int. J. Med. Robot. 2022;18: e2374. [CrossRef]

- Harris JL, Eckert CE, Clymer JW, Petraiuolo WJ. The Viscoelastic Behavior of Soft Tissues Must be Accounted for in Stapler Design and Surgeon Technique. Surgical technology international. 2022;40: 97-103. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Margallo JA, González González A, García Moruno L, Gómez-Blanco JC, Pagador JB, Sánchez-Margallo FM. Comparative study of the use of different sizes of an ergonomic instrument handle for laparoscopic surgery. Appl Sci. 2020; 10(4): 1526. [CrossRef]

- Kono E, Taniguchi K, Lee S W, et al. Laparoscopic instrument for female surgeons: an innovative model for endoscopic purse-string suture. Minimally Invasive Therapy & Allied Technologies, 2020(3):1-4. [CrossRef]

- Shepherd JM, Harilingam MR, Hamade A. Ergonomics in laparoscopic surgery—a survey of symptoms and contributing factors. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2016; 26(1): 72-77. [CrossRef]

- Deck A C, Schings B D, Jones J, et al. Clamping assembly for linear surgical stapler:, US11278285B2[P]. 2022.

- Setty J, George S K, Ahamed S S, et al. Surgical stapling instrument and associated trigger mechanisms:, US10993714B2[P]. 2021.

- Rojatkar P, Henderson C, Hall S, Jenkins SA, Paulin-Curlee GG, Clymer JW, et al. A novel powered circular stapler designed for creating secure anastomoses. Medical Devices and Diagnostic Engineering, 2017;4: 94-100. [CrossRef]

- Kono E, Tomiwaza Y, Matsuo T, Nomura S. Rating and issues of mechanical anastomotic staplers in surgical practice: a survey of 241 Japanese gastroenterological surgeons. Surg Today. 2012;42: 962-972. [CrossRef]

- Kono E, Tada M, Kouchi M, Endo Y, Tomizawa Y, Matsuo T, et al. Ergonomic evaluation of a mechanical anastomotic stapler used by Japanese surgeons. Surg Today. 2014;44: 1040-1047. [CrossRef]

- Meghan R S, Nicole J B, Julia P S, Lynetta J F. Variables affecting surgeons' use of, and preferences for, instrumentation in veterinary laparoscopy[J]. Veterinary surgery: VS. 2023.

- Barry SL, Fransson BA, Spall BF, Gay JM. Effect of two instrument designs on laparoscopic skills performance. Vet Surg. 2012; 41: 988-993. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Duarte FJ, Lucas-Hernández M, Matos-Azevedo A, Sánchez-Margallo JA, Díaz-Güemes I, Sánchez-Margallo FM. Objective analysis of surgeons' ergonomy during laparoendoscopic single-site surgery through the use of surface electromyography and a motion capture data glove. Surg Endosc. 2014;28: 1314-1320. [CrossRef]

- Matern U, Kuttler G, Giebmeyer C, Waller P, Faist M. Ergonomic aspects of five different types of laparoscopic instrument handles under dynamic conditions with respect to specific laparoscopic tasks: An electromyographic-based study. Surg Endosc. 2004;18: 1231-41. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez AG, Barrios-Muriel J, Romero-Sanchez F, Salgado DR, Alonso FJ. Ergonomic assessment of a new hand tool design for laparoscopic surgery based on surgeons' muscular activity. Appl Ergon. 2020; 88: 103161. [CrossRef]

- Wahab AF, Lam CK, Sundaraj K. Analysis and Classification of Forearm Muscles Activities during Gripping using EMG Signals. 3rd International Conference on Movement, Health and Exercise. 2017;58: 88-92. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, V. d. A.; do Carmo, J. C.; Nascimento, F. A. d. O. Weighted-Cumulated S-Emg Muscle Fatigue Estimator. IEEE J. Biomed. Health. Inform. 2018, 22 (6): 1854– 1862. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).