1. Introduction

Cereal-based foods are indispensable constituents of the diet in both developed and developing countries as they are a fundamental source of daily energy, carbohydrates, protein, and fibre [

1,

2]. Cereals and derived products also enclose a variety of phytochemicals and there is a growing interest in the potential health benefits that these substances may offer [

3,

4,

5]. Breeding for end-use quality is one of the most important tasks within cereals [

6]. Accordingly, Tritordeum is a recently created grain, marketed in the world for human consumption [

7]. It has been produced by crossing

Triticum durum (durum wheat) and

Hordeum chilense (a wild barley species) [

8]. The amphidiploid crop (6x= 42, AABBHChHCh) has accreditation as a natural species since genetic enhancement has been achieved by traditional breeding and selection practices [

9]. This cereal has unique nutritional characteristics [

10,

11], including higher levels of lutein than common wheat, a higher fraction of dietary fibre [

12], and is richer in essential minerals and fructans [

11,

13]. It can be prospectively considered a valuable alternative to traditional wheat for the production of pasta, bread, and bakery products, combining the nutritional quality of barley with the technological quality of durum wheat [

10,

14]. Interestingly, Tritordeum products have excellent organoleptic properties [

10]. Tritordeum is also an attractive crop agronomically, with yields similar to wheat varieties, high resistance to drought and heat stress, and good resistance to pathogens [

15,

16]. As a result, this crop is increasingly grown in Europe under both conventional and organic farming systems, and recent studies show that conditions in the southern Mediterranean are ideal for its cultivation [

17].

In recent years, research has identified various wheat proteins, including gluten and non-gluten proteins, as contributors to adverse conditions such as wheat allergy, celiac disease, and non-celiac gluten/wheat sensitivity in susceptible individuals. Gluten has gained particular attention due to the increasing number of people identified as susceptible to this protein. Some evidence suggests that diverse grains contain different forms of gliadin peptides, which may have varying toxicities for people with gluten-related disorders [

18,

19,

20]. Additionally, the gluten-free diet is becoming increasingly popular [

21,

22]. This popularity is likely due to the positive perception of gluten-free foods as being natural and healthy, besides, there is a growing interest in ancient grains, which have been shown to have a healthier nutritional profile than modern wheat [

23]. Of note, levels of gluten in Tritordeum are lower than those found in common wheat [

24].

Several studies have shown that Tritordeum consumption has several beneficial effects, including increased antioxidant activity, reduced inflammation, improved blood sugar control, reduced cholesterol levels, and improved gut health [

11]. A recent study investigated subtle differences in the protein composition of two commercial varieties of Tritordeum, with potentially different consequences for immunoreactivity and allergenicity [

25]. Additionally, the response of non-celiac gluten-sensitive patients to Tritordeum bread was evaluated by assessing gastrointestinal symptoms, the release of gluten immunogenic peptides, and the composition of the gut microbiota [

26], and no obvious differences in gastrointestinal symptoms of gluten-sensitive non-celiac subjects were found between the gluten-free and bread study groups [

26]. Yet, it has been reported that short-term ingestion of Tritordeum-based bread does not prompt major changes in the diversity or community composition of the gut microbiota in healthy individuals [

27]. Another study evaluated the effects of a 12-week diet of Tritordeum-based foods (bread, baked goods, and pasta) in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) subjects on gastrointestinal symptoms and intestinal barrier integrity: the Tritordeum-based diet was reported to significantly reduce patients' symptoms [

28]. Another study suggested the possibility of reducing abdominal bloating and improving the psychological status of women with IBD with a diet containing Tritordeum [

29]. Yet, investigations

in vivo indicate Tritordeum as a cereal characterized by multiple nutraceutical specificities [

11].

In the current study, protein composition and the biological activity, of two Tritordeum varieties, named Bulel and Aucan, were assessed. The Triticum durum cultivar was employed as a reference control. Proteomics was employed to investigate the protein composition of Tritordeum; the impact of the protein-digested samples (DPs) was comparatively investigated in Caco-2 cells differentiated on permeable supports.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Flours of T. durum (Provental cv) and Tritordeum - Bulel and Aucan cultivars - were provided by IntiniFood (Putignano, BA, Italy). All reagents and solvents were from Sigma-Aldrich (Milan, Italy).

2.2. Protein Extraction

Flour (100 mg) was defatted three times with 1mL of hexane under continuous stirring (30 min, 22 °C). The suspension was centrifuged (5,000 × g, 15 min), and the solvent was discarded. The defatted material was air-dried overnight. Proteins were extracted from defatted flour with 1 mL of UREA 6M, 20 mM DTT under magnetic stirring for 1 h at 37 °C. After centrifugation at 10,000 x g for 10 min, the supernatant was collected and desalted with the pre-packed Econo-pack 10-DG column (Bio-Rad), equilibrated and eluted with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate. The effluent was monitored by UV absorbance at 280 nm (Ultrospec 160 2100 pro, Amersham Biosciences, Milan, Italy). Finally, desalted proteins were quantified using the Bradford method. Protein samples were stored at -80°C until use.

2.3. In Vitro Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion

The protein fractions were sequentially digested by gastric, duodenal (pepsin-trypsin-chymotrypsin-carboxypeptidase-elastase), as previously described [

30]. The resulting digested protein (DPs) samples were stored at -80˚C until use.

2.3. Cell Cultures

The Caco-2 colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line was purchased from ATCC (Philadelphia, PA). Cells at passage 20−30 were incubated in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 20% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 1% non-essential amino acids, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin, in a humidified 5% CO

2 at 37 °C [

20,

31]. Subculture was performed at 80% of confluence and the medium was changed every other day.

2.4. Effects of DPs on Transepithelial Electrical Resistance (TEER)

Effects of DPs on TEER were comparatively determined in Caco-2 cells cultured on permeable supports. When differentiated for 21 days, cells established a polarized epithelial monolayer that provides a physical and biochemical barrier to the passage of ions and molecules. The resulting system was used as a predictive model of the mucosal barrier due to its intrinsic ability to differentiate spontaneously into polarized cells with morphological and functional characteristics of small intestinal enterocytes. Caco-2 cells were seeded on 0.4 μm pore size PET membrane transwell inserts (4.2 cm

2 growth surface area; BD Falcon, Italy) at 450,000 cells/cm

2, and cultured for 21 days before use. Monolayer integrity was enhanced by first covering the membrane with bovine collagen type I (Gibco, Invitrogen, Italy) [

20,

32]. Enterocyte differentiation was determined by evaluating the activity of alkaline phosphatase by using p-nitrophenyl phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich) as substrate [

33]. TEER was measured at room temperature (25 °C) through an epithelial voltammeter (Millicell ERS-2, Millipore, Italy) equipped with a dual planar electrode. Data were expressed as Ω×cm

2. Inserts with values lower than 800 Ω×cm

2 were discarded. Following incubation (0-300 minutes) in the presence or absence of different DPs, the TEER value for three sets of replicates was averaged; resulting data were expressed as change (%) from the baseline.

2.5. Effects of DPs on Cell Viability

The DPs-induced cytotoxicity on Caco-2 was evaluated by measuring the levels of intracellular ATP [

34]. Cells were plated in 96-well arrays at a density of 2×10

4 per well and differentiated for 21 days before being exposed to 1.0 mg/mL DPs for 24 hours in a reduced serum medium (5% FCS). Cell differentiation was preliminarily determined as above reported. After incubation with specific DPs, samples were processed by using the Vialight Plus Bioluminescence Assay Kit according to the manufacturer’s guidelines (Cambrex Bio Sci Rockland Inc., Rockland, ME). To each well was added 50 µL of nucleotide-(ATP) releasing reagent, and the plate was incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Then, 100 µL of resulting lysates were moved to a luminescence-compatible plate. Luminescence was acquired with a 1s integration time using a TopCount-NXTTM luminometer (Packard, USA). Cellular levels of ATP were reported as Relative Light Units (RLUs). The reported results were the mean of three determinations ± SD

2.6. Effects of DPs on the Structural Organization of F-actin

The modifications in the structural organization of F-actin microfilaments resulting from exposition to WDSs were examined by a fluorescence microscopy method [

19]. Cells were differentiated on plastic chamber slides under the growth conditions defined above and were exposed to 1.0 mg/mL DPs or PBS for 60 min. Following, monolayers were fixed with 3.75% formaldehyde in PBS for 5 min at room temperature, permeabilized with 0.1% TRITON® X-100 in PBS for 5 min, and washed twice with PBS. F-actin microfilaments were then stained with 50 µg/mL FITC-labeled phalloidin (Sigma-Aldrich). FITC-labelled cytoskeletal structures were characterized by fluorescence microscopy using an AxioVert 200 inverted microscope (Zeiss, Germany). Experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.7. Effects of DPs on ER Stress

Several stress conditions affecting the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) can trigger a complex signalling network that transduces the information status of protein folding to the nucleus and cytosol to reconstruct ER homeostasis. IRE1α, the most preserved stress sensor of unfolded protein response, is firmly related to the ER stress and acts as an endoribonuclease that processes the mRNA of the transcription factor XBP1. DPs effect on ER stress was assessed by RT-PCR to recognize XBP1 splicing in differentiated monolayers. The possible splicing was detected using specific primers for human XBP1 that identify both the unspliced (XBP1u) and the spliced (XBP1s) mRNA isoforms [

35,

36]. RNA was isolated by cell cultures and retro-transcribed to cDNA as described. XBP1s and/or XBP1u amplicons were obtained in a 30 µL PCR reaction containing cDNA and 12 pmol of each primer (5’-TTA CGA GAG AAA ACT CAT GGC C-3’; 5’-GGG TCC AAG TTG TCC AGA ATG C-3’). The cycling settings used were 3 min at 95 °C; 40 cycles of 60 s at 95 °C, annealing for 60 s at 55 °C, and extension for 60 s at 72 °C; and 5 min at 72 °C. Reactions were performed in triplicate and derived products were detected in 2.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide (Sigma Aldrich). After electrophoresis, images were recorded with a digital camera (GelDoc 2000 imaging system; Bio-RAD, Italy). Predictable PCR size products were XBP1u= 289 bp and XBP1s= 263 bp.

2.8. Proteomic Analysis

Proteins (100 µg) were dissolved in 100 µL of 62.5 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 2% SDS, 20 mM DTT 1h at 50 °C and then alkylated with 55 mM IAA for 1 h under magnetic stirring in the dark. The sample was desalted by Zeba Spin Desalting Columns (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA) and incubated with modified proteomic grade trypsin, using a 1:20 (w/w) trypsin-protein ratio, overnight at 37 °C. After desalting with a C18 spin column (Pierce C18 Spin Column, Thermo Scientific,), the sample was analysed by LC-MS/MS, using a Q Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA), online coupled with an Ultimate 3000 ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography instrument (Thermo Scientific). Peptides were resuspended in a water solution containing 0.1% (v/v) formic acid loaded through a 5 mm long, 300 mm i.d. pre-column (LC Packings, USA) and separated by an EASY-Spray™ PepMap C18 column (15 cm × 75 mm i.d.), 3 mm particles, 100 Å pore size (Thermo Scientific). The separation was carried out with a linear gradient from 5% to 45% of 0.1% formic acid (v/v) in 80% acetonitrile (eluent B), over 90 min at a flow rate of 300 nL/min, after 5 min equilibration at 4% B. Eluent A was 0.1% FA (v/v) in Milli-Q water. The mass spectrometer was operated in data-dependent mode, and all MS1 spectra were acquired in the positive ionization mode in the mass scanning range 350–1600 m/z. A resolving power up to 70,000 full widths at half maximum (FWHM), an automatic gain control (AGC) target of 106 ions and a maximum ion injection time (IT) of 120 ms were set as standard values to generate precursor spectra. MS/MS fragmentation spectra were obtained at a resolving power of 17,500 FWHM. In order to prevent repeated fragmentation of the most abundant ions, a dynamic exclusion of 10 s was applied. Ions with one or more than six charges were excluded. Spectra were elaborated using the Xcalibur Software version 3.1 (Thermo Scientific). The resulting MS/MS spectra were searched against the

Triticum and

Hordeum UniprotKB dataset downloaded in 2022 (

https://uniprot.org), using the MaxQuant platform (

https://maxquant.org) (version 1.6.2.10). Database searching was performed by using Cys carbamidomethylation and Met oxidation as fixed and variable protein modifications respectively, a mass tolerance value of 10 ppm for precursor ion and 20 ppm for MS/MS fragments, trypsin as proteolytic enzyme, and a missed cleavage maximum value of 2. Peptide Spectrum Matches (PSMs) were filtered using the target decoy database approach at 0.01 peptide-level false discovery rate (FDR), corresponding to a 99% confidence score, and validation based on the

q-value (< 1 x 10

-5).

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Differences between groups were determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni correction. Results were expressed as mean ± SD. A value of p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Graphical representation of data and statistical analysis were achieved using GraphPad Prism 9 Software (GraphPad, San Diego, USA).

Perseus version 1.6.5.0 (Max-Planck-Institute of Biochemistry, Martinsried, Germany,

https://maxquant.net/perseus) was specifically used to perform the statistical analysis of proteome data. The label-free quantitative (LFQ) protein intensities from the MaxQuant analysis were imported and transformed to a logarithmic scale with base 2. The missing LFQ intensity values (NaN) were replaced using low LFQ intensity values from the normal distribution (width = 0.3, downshift = 1.8). Contaminants and not valid values were removed and only proteins identified with “sequenced peptide > 1” and “unique peptides >2” were considered. A permutation-based FDR of 5% was used for truncation of all test results. Only proteins with a probability for significant protein abundance changes with a

p-value < 0.05 were used for fold change visualization.

3. Results

3.1. Caco-2 Cells

The biological effects of DPs were evaluated in Caco-2 cells cultured on transwell inserts. Once differentiated, the cells were arranged as a polarized epithelial monolayer with functional and morphological characteristics of small intestinal enterocytes. Toxicity and biochemical effects were detected after incubation with different DPs [

20,

32,

37,

38]. The optimal incubation conditions with DPs were preliminarily determined in pilot studies.

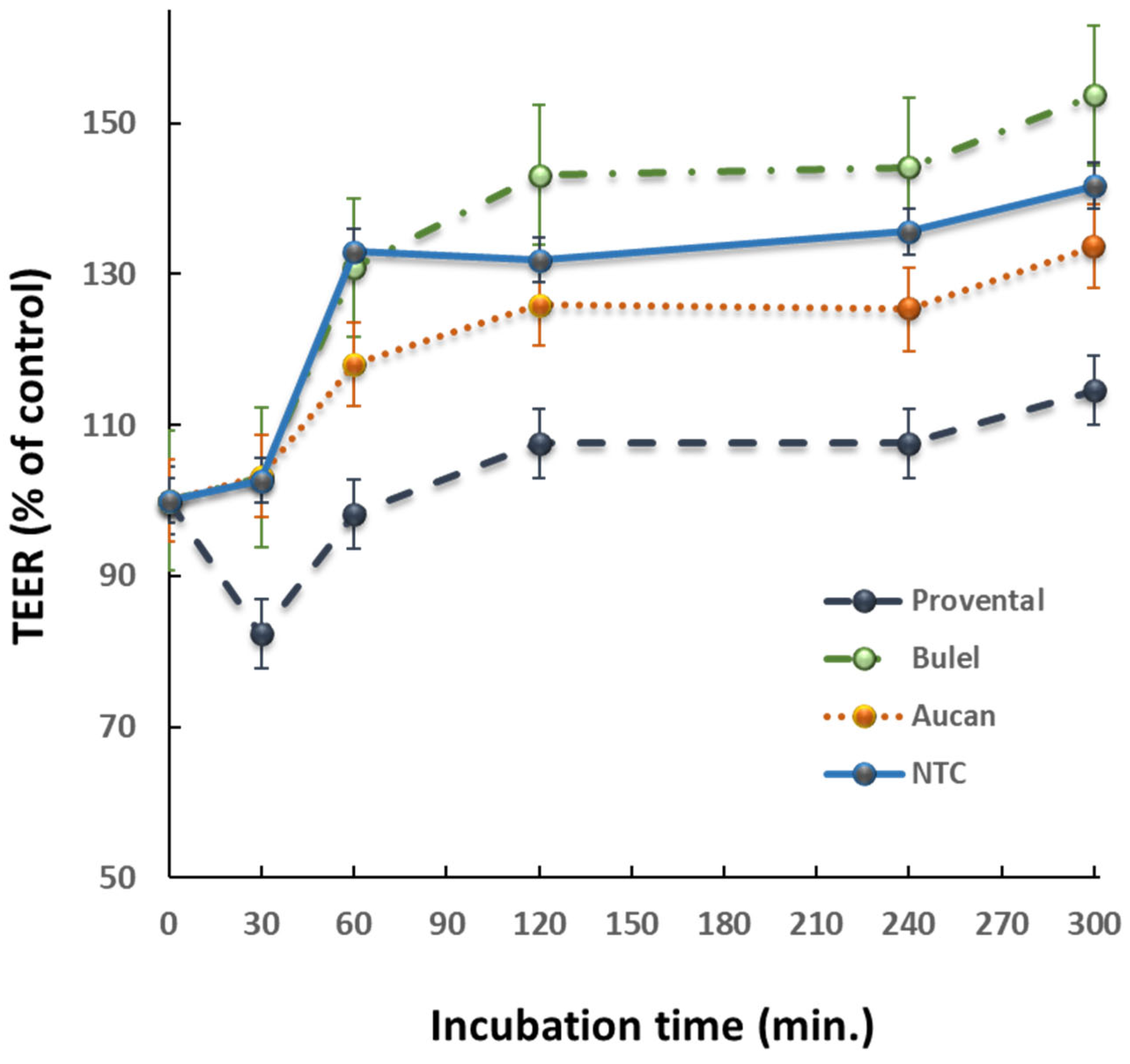

3.2. Effect of DPs on Epithelial Permeability

Effects of DPs on paracellular permeability were assessed in Caco-2 cells cultured on transwell insert chambers. After 21 days of differentiation, TEER values usually stabilized at >800 Ω×cm

2. This value was indicative of the integrity of the monolayer and a well-established TJs-permeability barrier. Exposure to Provental-DPs disrupted the TJs-permeability barrier with a prompt effect detectable after 30 min incubation time. The effects of Tritordeum cultivar DPs on paracellular permeability were comparatively evaluated (Fig. 1). TEER values remained almost unchanged when monolayers were incubated with Bulel- or Aucan-DPs. Notably, Bulel-DPs did not increase the permeability of the monolayer, while Aucan-DPs exerted only a slight effect compared with the untreated control. The damage caused by the positive control (Triticum-DPs) on paracellular permeability was reversible, as TEER returned to baseline after the removal of DPs from the cell growth medium (data not shown), in agreement with our previous studies. [

19].

Figure 1.

Transepithelial electrical resistance changes were evaluated in differentiated Caco-2 cells following incubation with 1 mg/mL of different DPs. Data were expressed as normalised changes in TEER. Plots are representative of three different experiments. NTC = non-treated control.

Figure 1.

Transepithelial electrical resistance changes were evaluated in differentiated Caco-2 cells following incubation with 1 mg/mL of different DPs. Data were expressed as normalised changes in TEER. Plots are representative of three different experiments. NTC = non-treated control.

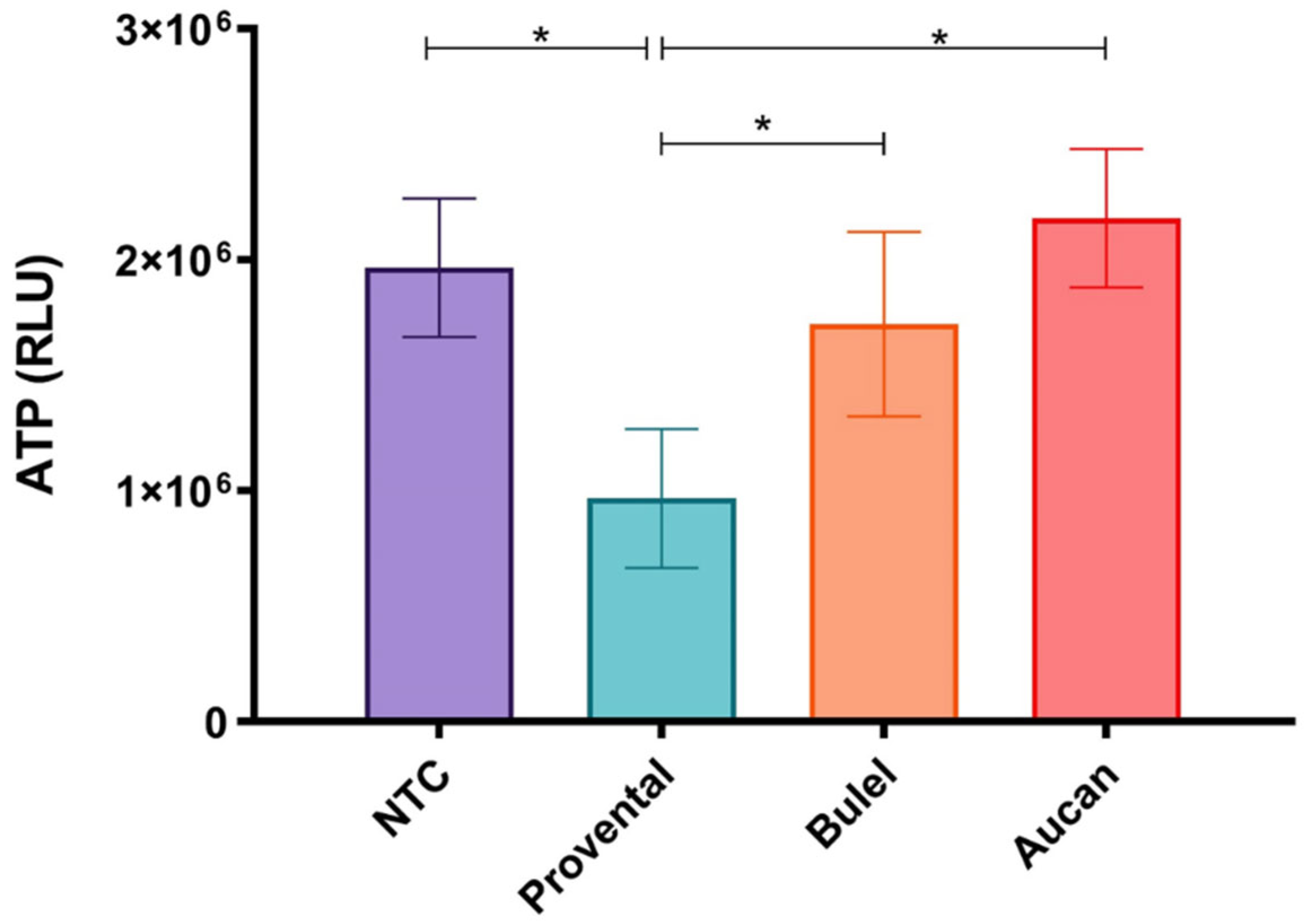

3.3. Effects of DPs on Cell Viability

ATP is the key molecule in the chemistry of all living cells. Its levels are tightly regulated and retained within a fine concentration range. Quantification of total ATP content in cultured cells represents an advantageous method to determine the number of viable cells since ATP levels reflect the presence of metabolically active cells and, at the same time, represent an easily accessible marker for cell functional integrity [

34]. The effects of 24-hour incubation to 1.0 mg/mL DPs from different cultivars were determined by monitoring ATP availability in differentiated Caco-2 cells. Exposure to Provental- DPs prompted substantial cytotoxicity documented by a noticeable decline in ATP levels when compared to the untreated control (p< 0.05) (Fig. 2). In contrast, the viability of cells exposed to both Bulel- and Aucan-DPs remained almost unchanged (p>0.05), thus evidencing the absence of appreciable toxicity exerted by Tritordeum cultivars in the experimental settings. Besides, a reduced ATP availability was observed in Bulel-DPs treated cells as compared to Aucan-DPs, nonetheless, this tendency did not reach a statistical significance (p>0.05). Similar trends were recorded when monolayers were exposed for 4 hours to DPs (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Effects of 1 mg/mL DPs on cell viability were determined by monitoring ATP levels in differentiated Caco-2 cells. After 24 hours of incubation, luminescence was acquired with a 1 sec integration time. Intracellular levels of ATP were expressed as relative light units (RLUs). Values are the mean ±SD of three experiments. *p<0.01.

Figure 2.

Effects of 1 mg/mL DPs on cell viability were determined by monitoring ATP levels in differentiated Caco-2 cells. After 24 hours of incubation, luminescence was acquired with a 1 sec integration time. Intracellular levels of ATP were expressed as relative light units (RLUs). Values are the mean ±SD of three experiments. *p<0.01.

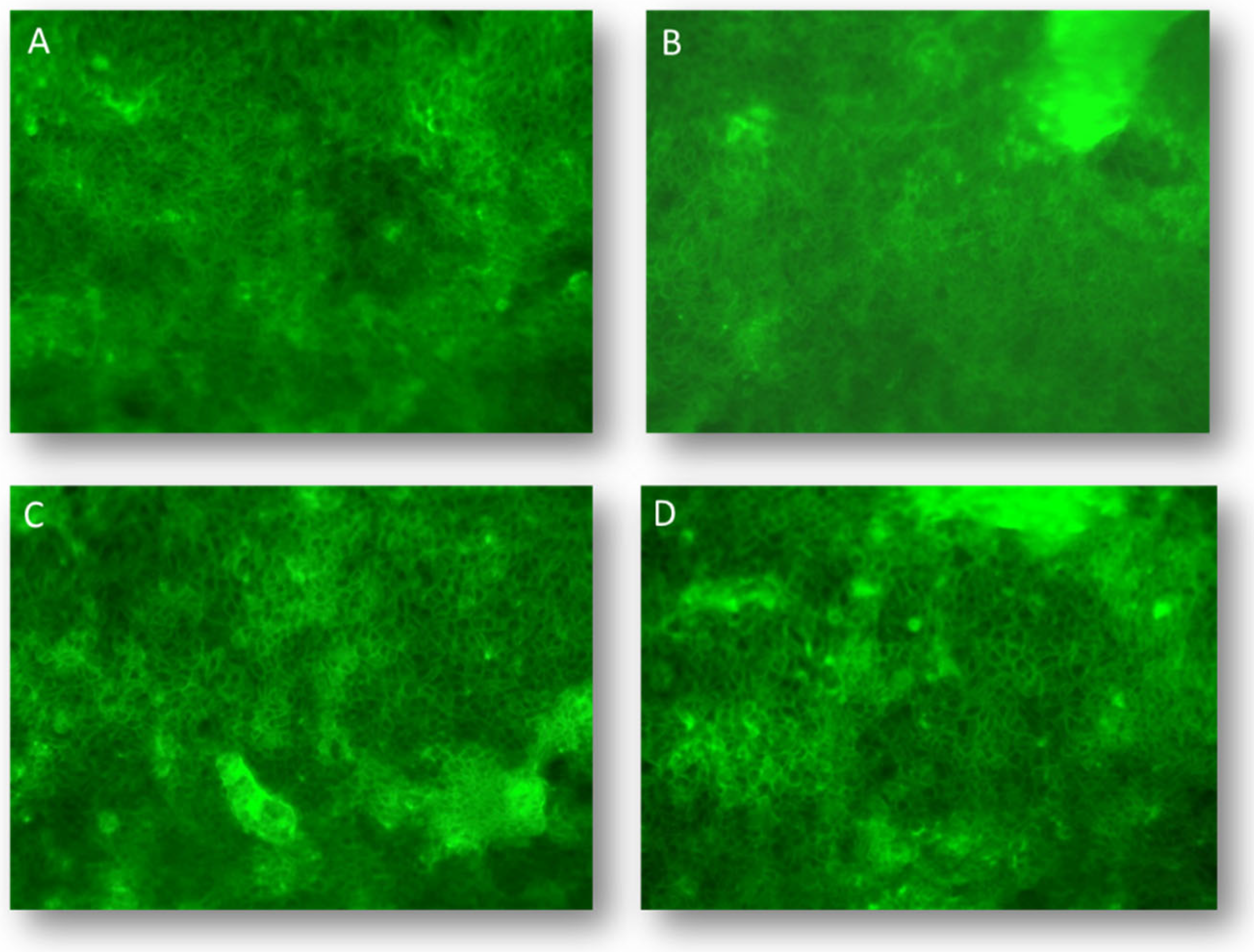

3.4. Structural Organization of F-actin

In enterocytes, as well as in differentiated Caco-2 cells, F-actin filaments interact with epithelial junctional complexes and are attractively located as a continuous band in the apical peri-junctional area surrounding the cells (Fig. 3A) [

39].

This cytoskeletal network is involved in the dynamic modulation of paracellular permeability and intracellular traffic by interacting directly with TJs. Besides, it has been shown that gliadin-derived peptides can alter intestinal permeability by inducing the apical secretion of zonulin, which in turn induces the protein kinase C-mediated polymerization of endo-cellular actin [

40,

41]. Accordingly, the structural organization of F-actin was addressed in differentiated Caco-2 cells following DPs exposure. Provental-DPs prompted a discernible reorganization of the enterocyte cytoskeleton structure (Fig. 3B). Differently, Bulel- and Aucan-DPs did not evoke changes in the cytoskeleton structure (Fig. 3, panels C and D) as compared to the untreated control.

Figure 3.

Structural organization of F-actin microfilaments was assessed in differentiated Caco-2. Cells were grown and differentiated onto chamber slides and, after one-hour exposure to 1.0 mg/mL of specific DPs were fixed and stained with FITC-labeled phalloidin to highlight microfilaments organization (X 200 magnification). Untreated control (A); cells incubated with Provental-DPs (B); with Bulel-DPs (C); with Aucan-DPs (D). Images are representative of three experiments performed independently under identical conditions.

Figure 3.

Structural organization of F-actin microfilaments was assessed in differentiated Caco-2. Cells were grown and differentiated onto chamber slides and, after one-hour exposure to 1.0 mg/mL of specific DPs were fixed and stained with FITC-labeled phalloidin to highlight microfilaments organization (X 200 magnification). Untreated control (A); cells incubated with Provental-DPs (B); with Bulel-DPs (C); with Aucan-DPs (D). Images are representative of three experiments performed independently under identical conditions.

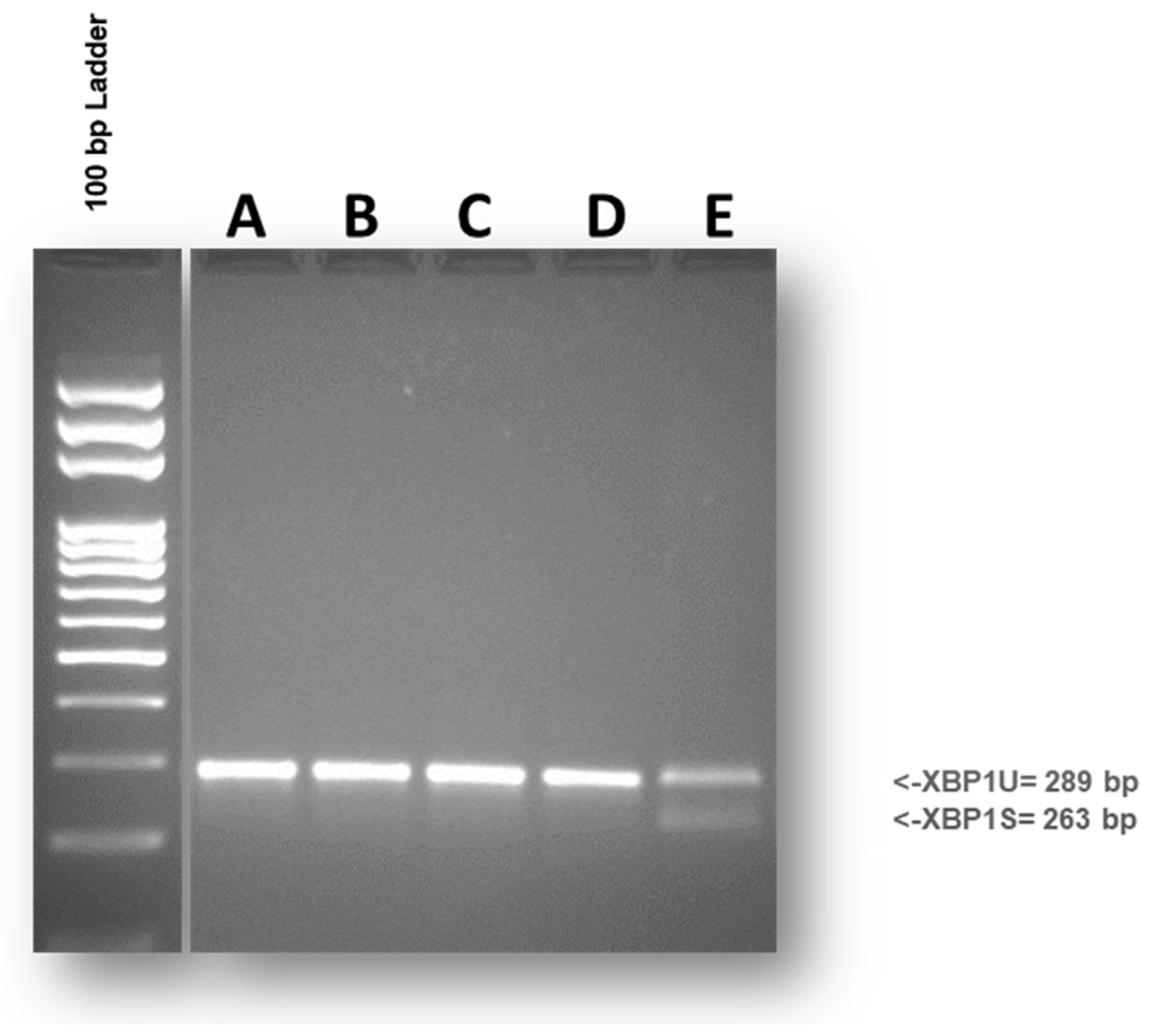

3.5. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress

Inositol-requiring transmembrane kinase/endonuclease-1 (IRE1α) is the most conserved stress sensor of the unfolded protein response and its activity is strictly associated with the stress status of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). IRE1α biochemically acts as a ribonuclease that processes the mRNA of the transcription factor X-box binding protein-1 (XBP1). Accordingly, an intron of 26 nucleotides is spliced out from XBP1 mRNA by the activated IRE1α. In most studies, unconventional mRNA splicing can be recognized by RT-PCR performed with primers for XBP1 able to detect both the unspliced (XBP1u) and the spliced (XBP1s) isoforms [

36]. In our experimental system, the effects on ER stress from 24-hour exposure to different DPs were evaluated. As shown in Fig. 4, no differences were recorded between differentiated Caco-2 cells exposed to DPs from Triticum, Tritordeum and the untreated control. Overall, exposure to various DPs did not evoke XBP1 splicing, thus highlighting that the ER stress response is not a mechanism involved in the cellular response.

Figure 4.

Splicing of XBP1 mRNA was evaluated in 24h DPs treated cells. XBP1 was amplified, separated and visualized on a 2.5% agarose gel. The size of expected PCR products was XBP1u= 289 bp and XBP1s= 263 bp. No differences were appreciable between Caco-2 cells exposed to DPs and untreated control. Untreated control (A); cells incubated with Provental-DPs (B); cells incubated with Bulen-DPs (C); cells incubated with Aucan-DPs (D); positive control (E). The gel is representative of three experiments performed independently.

Figure 4.

Splicing of XBP1 mRNA was evaluated in 24h DPs treated cells. XBP1 was amplified, separated and visualized on a 2.5% agarose gel. The size of expected PCR products was XBP1u= 289 bp and XBP1s= 263 bp. No differences were appreciable between Caco-2 cells exposed to DPs and untreated control. Untreated control (A); cells incubated with Provental-DPs (B); cells incubated with Bulen-DPs (C); cells incubated with Aucan-DPs (D); positive control (E). The gel is representative of three experiments performed independently.

3.6. Protein Analysis

The protein composition of Tritordeum DPs cultivars was investigated by LC-MS/MS-based bottom-up proteomics. Overall 596 gene products from Trititicum and Hordeum species were identified using the MaxQuant search engine. The complete list of gene products identified is reported in

Supplementary Table S1. Distinguishing barley-specific proteins from Triticum ones was a challenge, because of the level of homology between these two species [

42]. Most of the identified proteins were involved in the metabolic process. This was not surprising, considering the difficulty of analyzing storage proteins such as gluten or hordein, which requires a targeted analytical approach [

43,

44].

Figure 5 shows the result of the statistical analysis performed by Perseur software [

45]. A number of 24 significant different proteins between the Tritordeum cvs and Triticum were found. The Tritordeum cvs Aucan and Bulel showed similar protein patterns with the expression of protein lactolylglutathione liase that was in common with Triticum durum species (Provental cv).

4. Discussion

This study aimed to determine the biological effects of Tritordeum versus Triticum durum. The DPs effects were determined by using Caco-2 differentiated on transwell inserts since differentiated cells establish a polarized epithelial monolayer that provides a physical and biochemical barrier to the passage of ions and molecules. The resulting system was used as a predictive model of human small intestinal mucosa to assess alterations triggered by different DPs. Changes in monolayer barrier function are relevant because antigen trafficking from the apical to the basolateral compartment is a finely controlled process, the dysfunction of which can be reflected in vivo in the delicate balance between induction of immune-inflammatory response and tolerance, with critical repercussions on the onset and progression of gut-related disorders.

In our system, the exposure of Caco-2 to Provental-DPs readily disrupted the tight junction barrier as predictable. Interestingly, Aucan-DPs did not alter the permeability of the monolayer, whereas Bulel-DPs exerted only minor effects. Yet, Aucan-DPs and Bulel-DPs did not affect monolayer viability or alter cytoskeleton structure, whereas, incubation with Provental-DPs resulted in significant toxicity confirmed by extensive reorganization of the enterocytes cytoskeleton with concomitant changes in cell viability [

18,

19]. Of note, our results are in line with a recent trial of a diet with Tritordeum-based foods in patients with IBD, in which health improvement seems to occur through an overall improvement of the gastrointestinal barrier [

28].

Unfortunately, the proteomic exploration did not highlight relevant differences between the Tritordeum and

Triticum durum lines, such as to explain the different toxicity. Notably, the proteomic analysis has mainly identified metabolic proteins, providing on the contrary poor information on the gluten content, the analysis of which requires a target analytical approach. Most likely, the different biological behaviour is attributable to the gluten content expressed in the two species. Previous studies suggested that Tritordeum cvs have a lower content of indigestible gliadin peptides which may induce inflammation and intestinal barrier dysfunction [

27].

Cereal-based foods have a long history as part of the human diet dating back far in the mists of time. Numerous studies have confirmed the essential role of whole grains in conferring human health benefits and improving well-being since they contain a wide range of nutrients [

46]. Besides, gluten-related disorders have shown increased prevalence in Western countries in recent years, and growing concerns about the possible adverse effects of wheat on a range of diseases in susceptible individuals have been highlighted with the increasing adoption of wheat-free or gluten-free diets [

21,

22]. However, there is no solid scientific evidence to confirm the health benefits of a gluten-free diet. On the contrary, gluten-free products are usually poor in vitamins, minerals, phytochemicals, proteins, and dietary fibre, all nutrients essential for a well-balanced and healthy diet [

47]. In this regard, the need for grain varieties with low toxicity is highlighted [

48,

49,

50]. Of course, given the inter-varieties heterogeneity, both total gliadin content and the proportions of the different gliadin types vary considerably among different wheat cultivars [

51].

In this scenario, the prospect of using Tritordeum as a candidate crop with low toxicity and as a source of components for healthful foods is certainly of considerable interest.

5. Conclusions

Our results are relevant to consider foods derived from Tritordeum as having different nutraceutical specificities compared to modern wheat varieties and provide evidence to support its consumption for health purposes. According to recent scientific literature, collected data further support the use of Tritordeum as an attractive opportunity for the food processing industry to meet today's consumer demand for healthy, gluten-reduced, and functional products, while also considering the sustainability aspects of this "golden grain". With this in mind, Tritordeum, while not a safe grain for celiacs, could be useful as a low-toxicity candidate crop and as a source of components for health-valued foods. However, additional studies are required to assess the putative health benefits deriving from its consumption in specifically designed intervention studies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: List of the identified gene products.

Author Contributions

G.I., GF.M., and D.P. conceived, designed, and oversaw the analyses and drafted the manuscript. G.I., A.V., and D.D. conducted the biological and molecular analyses. GF.M., S.DC., and L.DS. conducted the proteomics research. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Project funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.3 - Call for proposals No. 341 of 15 March 2022 of Italian Ministry of University and Research funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU; Award Number: Project code PE00000003, Concession Decree No. 1550 of 11 October 2022 adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, CUP B83C22004790001, Project title “ON Foods - Research and innovation network on food and nutrition Sustainability, Safety and Security – Working ON Foods”. This work was also supported by the CNR project NUTRAGE FOE-2021 DBA.AD005.225.

Data Availability Statement

All data produced or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the financial support provided by the National Research Council's NUTRAGE project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- MacEvilly, C. CEREALS | Contribution to the Diet. 2003, 1008-1014. [CrossRef]

- Serna Saldivar, S.O. CEREALS | Dietary Importance. 2003, 1027-1033. [CrossRef]

- Belobrajdic, D.P.; Bird, A.R. The potential role of phytochemicals in wholegrain cereals for the prevention of type-2 diabetes. Nutrition Journal 2013, 12. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.H. Whole grain phytochemicals and health. Journal of Cereal Science 2007, 46, 207-219. [CrossRef]

- Luthria, D.L.; Lu, Y.; John, K.M.M. Bioactive phytochemicals in wheat: Extraction, analysis, processing, and functional properties. Journal of Functional Foods 2015, 18, 910-925. [CrossRef]

- Araus, J.L. Plant Breeding and Drought in C3 Cereals: What Should We Breed For? Annals of Botany 2002, 89, 925-940. [CrossRef]

- Barcelo, P.; Cabrera, A.; Hagel, C.; Lorz, H. Production of doubled-haploid plants from Tritordeum anther culture. Theor Appl Genet 1994, 87, 741-745. [CrossRef]

- Martín, A.; Martínez-Araque, C.; Rubiales, D.; Ballesteros, J. Tritordeum: Triticale’s New Brother Cereal. 1996, 5, 57-72. [CrossRef]

- Lima-Brito, J.; Guedes-Pinto, H.; Harrison, G.E.; Heslop-Harrison, J.S. Molecular cytogenetic analysis of durum wheat × Tritordeum hybrids. Genome 1997, 40, 362-369. [CrossRef]

- Vaquero, L.; Comino, I.; Vivas, S.; Rodríguez-Martín, L.; Giménez, M.J.; Pastor, J.; Sousa, C.; Barro, F. Tritordeum: a novel cereal for food processing with good acceptability and significant reduction in gluten immunogenic peptides in comparison with wheat. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2018, 98, 2201-2209. [CrossRef]

- Giordano, D.; Reyneri, A.; Locatelli, M.; Coïsson, J.D.; Blandino, M. Distribution of bioactive compounds in pearled fractions of Tritordeum. Food Chemistry 2019, 301, 125228. [CrossRef]

- Suchowilska, E.; Radawiec, W.; Wiwart, M. Tritordeum – the content of basic nutrients in grain and the morphological and anatomical features of kernels. International Agrophysics 2021, 35, 343-355. [CrossRef]

- Paznocht, L.; Kotikova, Z.; Sulc, M.; Lachman, J.; Orsak, M.; Eliasova, M.; Martinek, P. Free and esterified carotenoids in pigmented wheat, Tritordeum and barley grains. Food Chem 2018, 240, 670-678. [CrossRef]

- Arora, K.; Carafa, I.; Fava, F.; Tuohy, K.M.; Nikoloudaki, O.; Gobbetti, M.; Cagno, R.D. Sourdough performances of the golden cereal Tritordeum: Dynamics of microbial ecology, biochemical and nutritional features. Int J Food Microbiol 2022, 374, 109725. [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, M.; Fereres, E. Growth, grain yield and water use efficiency of Tritordeum in relation to wheat. European Journal of Agronomy 1993, 2, 83-91. [CrossRef]

- Ávila, C.M.; Rodríguez-Suárez, C.; Atienza, S.G. Tritordeum: Creating a New Crop Species-The Successful Use of Plant Genetic Resources. Plants (Basel) 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Kakabouki, I.; Beslemes, D.F.; Tigka, E.L.; Folina, A.; Karydogianni, S.; Zisi, C.; Papastylianou, P. Performance of Six Genotypes of Tritordeum Compare to Bread Wheat under East Mediterranean Condition. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9700.

- Mamone, G.; Iacomino, G. Comparison of the in vitro toxicity of ancient Triticum monococcum varieties ID331 and Monlis. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2018, 69, 954-962. [CrossRef]

- Iacomino, G.; Di Stasio, L.; Fierro, O.; Picariello, G.; Venezia, A.; Gazza, L.; Ferranti, P.; Mamone, G. Protective effects of ID331 Triticum monococcum gliadin on in vitro models of the intestinal epithelium. Food Chem 2016, 212, 537-542. [CrossRef]

- Iacomino, G.; Fierro, O.; D'Auria, S.; Picariello, G.; Ferranti, P.; Liguori, C.; Addeo, F.; Mamone, G. Structural analysis and Caco-2 cell permeability of the celiac-toxic A-gliadin peptide 31-55. J Agric Food Chem 2013, 61, 1088-1096. [CrossRef]

- Shewry, P.R.; Hey, S.J. Do we need to worry about eating wheat? Nutrition Bulletin 2016, 41, 6-13. [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.M.; Sheats, D.B. Consumer Trends in Grain Consumption. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.; Whittaker, A.; Pagliai, G.; Benedettelli, S.; Sofi, F. Ancient wheat species and human health: Biochemical and clinical implications. J Nutr Biochem 2018, 52, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Visioli, G.; Lauro, M.; Vamerali, T.; Dal Cortivo, C.; Panozzo, A.; Folloni, S.; Piazza, C.; Ranieri, R. A Comparative Study of Organic and Conventional Management on the Rhizosphere Microbiome, Growth and Grain Quality Traits of Tritordeum. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1717.

- Nitride, C.; D'Auria, G.; Dente, A.; Landolfi, V.; Picariello, G.; Mamone, G.; Blandino, M.; Romano, R.; Ferranti, P. Tritordeum as an Innovative Alternative to Wheat: A Comparative Digestion Study on Bread. Molecules 2022, 27. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-León, S.; Haro, C.; Villatoro, M.; Vaquero, L.; Comino, I.; González-Amigo, A.B.; Vivas, S.; Pastor, J.; Sousa, C.; Landa, B.B.; et al. Tritordeum breads are well tolerated with preference over gluten-free breads in non-celiac wheat-sensitive patients and its consumption induce changes in gut bacteria. J Sci Food Agric 2021, 101, 3508-3517. [CrossRef]

- Haro, C.; Guzman-Lopez, M.H.; Marin-Sanz, M.; Sanchez-Leon, S.; Vaquero, L.; Pastor, J.; Comino, I.; Sousa, C.; Vivas, S.; Landa, B.B.; et al. Consumption of Tritordeum Bread Reduces Immunogenic Gluten Intake without Altering the Gut Microbiota. Foods 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Russo, F.; Riezzo, G.; Linsalata, M.; Orlando, A.; Tutino, V.; Prospero, L.; D'Attoma, B.; Giannelli, G. Managing Symptom Profile of IBS-D Patients With Tritordeum-Based Foods: Results From a Pilot Study. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 797192. [CrossRef]

- Riezzo, G.; Prospero, L.; Orlando, A.; Linsalata, M.; D'Attoma, B.; Ignazzi, A.; Giannelli, G.; Russo, F. A Tritordeum-Based Diet for Female Patients with Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Effects on Abdominal Bloating and Psychological Symptoms. Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Gianfrani, C.; Camarca, A.; Mazzarella, G.; Di Stasio, L.; Giardullo, N.; Ferranti, P.; Picariello, G.; Rotondi Aufiero, V.; Picascia, S.; Troncone, R.; et al. Extensive in vitro gastrointestinal digestion markedly reduces the immune-toxicity of Triticum monococcum wheat: implication for celiac disease. Mol Nutr Food Res 2015, 59, 1844-1854. [CrossRef]

- Iacomino, G.; Marano, A.; Stillitano, I.; Aufiero, V.R.; Iaquinto, G.; Schettino, M.; Masucci, A.; Troncone, R.; Auricchio, S.; Mazzarella, G. Celiac disease: role of intestinal compartments in the mucosal immune response. Molecular and cellular biochemistry 2016, 411, 341-349. [CrossRef]

- Picariello, G.; Iacomino, G.; Mamone, G.; Ferranti, P.; Fierro, O.; Gianfrani, C.; Di Luccia, A.; Addeo, F. Transport across Caco-2 monolayers of peptides arising from in vitro digestion of bovine milk proteins. Food Chem 2013, 139, 203-212. [CrossRef]

- Iacomino, G.; Tecce, M.F.; Grimaldi, C.; Tosto, M.; Russo, G.L. Transcriptional response of a human colon adenocarcinoma cell line to sodium butyrate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001, 285, 1280-1289. [CrossRef]

- Aslantürk, Ö.S. In Vitro Cytotoxicity and Cell Viability Assays: Principles, Advantages, and Disadvantages. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Iacomino, G.; Rotondi Aufiero, V.; Iannaccone, N.; Melina, R.; Giardullo, N.; De Chiara, G.; Venezia, A.; Taccone, F.S.; Iaquinto, G.; Mazzarella, G. IBD: Role of intestinal compartments in the mucosal immune response. Immunobiology 2019, 151849. [CrossRef]

- Cawley, K.; Deegan, S.; Samali, A.; Gupta, S. Assays for Detecting the Unfolded Protein Response. 2011, 490, 31-51. [CrossRef]

- Fasano, A.; Not, T.; Wang, W.; Uzzau, S.; Berti, I.; Tommasini, A.; Goldblum, S.E. Zonulin, a newly discovered modulator of intestinal permeability, and its expression in coeliac disease. Lancet 2000, 355, 1518-1519. [CrossRef]

- Sander, G.R.; Cummins, A.G.; Henshall, T.; Powell, B.C. Rapid disruption of intestinal barrier function by gliadin involves altered expression of apical junctional proteins. FEBS Lett 2005, 579, 4851-4855. [CrossRef]

- Madara, J.L.; Stafford, J.; Barenberg, D.; Carlson, S. Functional coupling of tight junctions and microfilaments in T84 monolayers. Am J Physiol 1988, 254, G416-423.

- Ensari, A.; Marsh, M.N.; Morgan, S.; Lobley, R.; Unsworth, D.J.; Kounali, D.; Crowe, P.T.; Paisley, J.; Moriarty, K.J.; Lowry, J. Diagnosing coeliac disease by rectal gluten challenge: a prospective study based on immunopathology, computerized image analysis and logistic regression analysis. Clin Sci (Lond) 2001, 101, 199-207.

- Fasano, A. Zonulin and its regulation of intestinal barrier function: the biological door to inflammation, autoimmunity, and cancer. Physiol Rev 2011, 91, 151-175. [CrossRef]

- Dionisio, G.; Holm, P.B.; Brinch-Pedersen, H. Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) multiple inositol polyphosphate phosphatases (MINPPs) are phytases expressed during grain filling and germination. Plant Biotechnol J 2007, 5, 325-338. [CrossRef]

- Mamone, G.; Picariello, G.; Caira, S.; Addeo, F.; Ferranti, P. Analysis of food proteins and peptides by mass spectrometry-based techniques. J Chromatogr A 2009, 1216, 7130-7142. [CrossRef]

- Mamone, G.; Picariello, G.; Addeo, F.; Ferranti, P. Proteomic analysis in allergy and intolerance to wheat products. Expert Rev Proteomics 2011, 8, 95-115. [CrossRef]

- Tyanova, S.; Temu, T.; Sinitcyn, P.; Carlson, A.; Hein, M.Y.; Geiger, T.; Mann, M.; Cox, J. The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat Methods 2016, 13, 731-740. [CrossRef]

- Okarter, N.; Liu, R.H. Health Benefits of Whole Grain Phytochemicals. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2010, 50, 193-208. [CrossRef]

- Diez-Sampedro, A.; Olenick, M.; Maltseva, T.; Flowers, M. A Gluten-Free Diet, Not an Appropriate Choice without a Medical Diagnosis. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism 2019, 2019, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Békés, F.; Schoenlechner, R.; Tömösközi, S. Ancient Wheats and Pseudocereals for Possible use in Cereal-Grain Dietary Intolerances. 2017, 353-389. [CrossRef]

- Sapone, A.; Bai, J.C.; Ciacci, C.; Dolinsek, J.; Green, P.H.R.; Hadjivassiliou, M.; Kaukinen, K.; Rostami, K.; Sanders, D.S.; Schumann, M.; et al. Spectrum of gluten-related disorders: consensus on new nomenclature and classification. BMC Medicine 2012, 10. [CrossRef]

- King, J.A.; Jeong, J.; Underwood, F.E.; Quan, J.; Panaccione, N.; Windsor, J.W.; Coward, S.; deBruyn, J.; Ronksley, P.E.; Shaheen, A.-A.; et al. Incidence of Celiac Disease Is Increasing Over Time. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 2020, 1. [CrossRef]

- De Santis, M.A.; Giuliani, M.M.; Giuzio, L.; De Vita, P.; Lovegrove, A.; Shewry, P.R.; Flagella, Z. Differences in gluten protein composition between old and modern durum wheat genotypes in relation to 20th century breeding in Italy. European Journal of Agronomy 2017, 87, 19-29. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).