Submitted:

08 December 2023

Posted:

08 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Data and data processing method

2.1. Dataset

2.2. Automatic search for ionospheric PERs

3. Different properties of ionospheric PERs

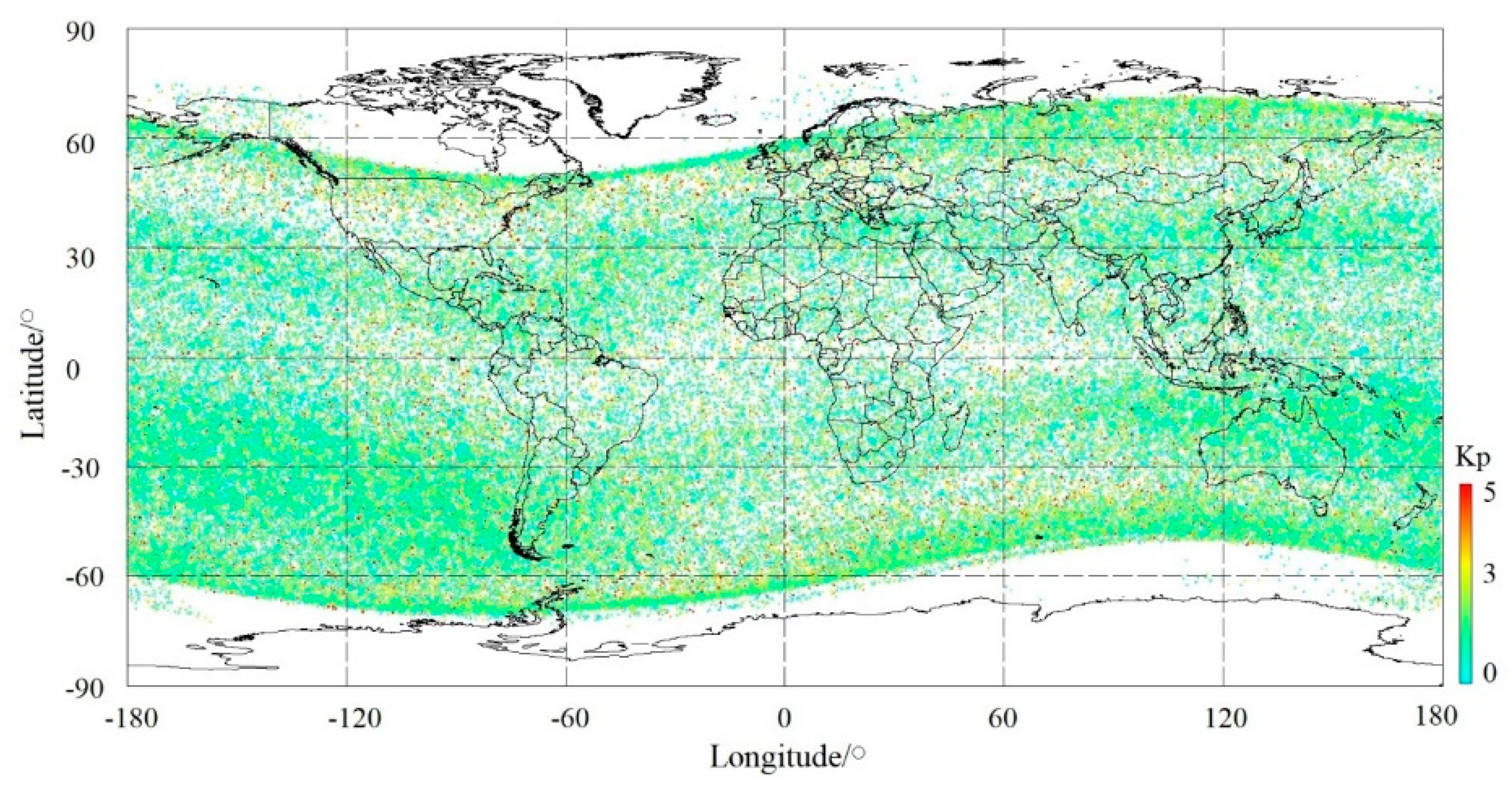

3.1. Effect of the solar activity on the ionosphere

3.2. Local time discrepancy of ionospheric PERs

3.3. Seasonal variation of ionospheric PERs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eckersley, T.L. Studies in radio transmission. Institution of Electrical Engineers-Proceedings of the Wireless Section of the Institution, 1932, 71, 405–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckersley, T.L. Irregular ionic clouds in the E layer of the ionosphere. Nature, 1937, 140, 846–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booker, H.G.; Wells, H.W. Scattering of radio waves by the F-region of the ionosphere. J. Geophys. Res. 1938, 43, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, E.V. Two anomalies in the ionosphere. Nature 1946, 157, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarons, J. Global morphology of ionospheric scintillations. Proceedings of the IEEE 1982, 70, 360–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S. VHF ionospheric Scintillationsat L = 2.8 and formation of stable auroral red arcs by magnetospheric heat conduction. J. Geophys. Res. 1974, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, J.K. The Solar-Terrestrial Environment an Introduction to Geospace-The Science of the Terrestrial Upper Atmosphere, Ionosphere, and Magnetosphere. Cambridge, UK, and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Houminer, Z.; Aarons, J. Production and dynamics of high-latitude irregularities during magnetic storms. J. Geophys. Res. 1981, 86, 9939–9944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krankowski, A.; Shagimuratov, I.I.; Ephishov, I.I.; Krypiak-Gregorczyk, A.; Yakimova, G. The occurrence of the mid-latitude ionospheric trough in GPS-TEC measurements. Adv. Space Res. 2009, 43, 1721–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Stolle, C.; Lühr, H.; Park, J.; Fejer, B.G.; Kervalishvili, G.N. Scale analysis of the equatorial plasma irregularities derived from Swarm constellation. Earth, Planets and Space 2016, 68, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyjaslak, B.; Przepiorka, D.; Rothkaehl, H. Seasonal Variations of Mid-Latitude Ionospheric Trough Structure Observed with DEMETER and COSMIC. Acta Geophysica, 2016, 64, 2734–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Park, J.; Lühr, H.; Stolle, C.; Ma, S. Comparing plasma bubble occurrence rates at CHAMP and GRACE altitudes during high and low solar activity. Annales Geophysicae 2010, 28, 1647–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, J. K. Principles of the ionosphere at middle and low latitude. In The Solar-Terrestrial Environment. An Introduction to Geospace-the Science of the Terrestrial Upper Atmosphere, Ionosphere, and Magnetosphere (pp. 208–210). Cambridge, UK, and New York: Cambridge University Press 1992. [CrossRef]

- Lomidze, L.; Knudsen, D.J.; Burchill, J.; Kouznetsov, A.; Buchert, S.C. Calibration and validation of Swarm plasma densities and electron temperatures using ground-based radars and satellite radio occultation measurements. Radio Science 2018, 53, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, R.W.; Nagy, A.F. Introduction. In Ionospheres: Physics, Plasma Physics, and Chemistry (pp. 1–10). New York: Cambridge University Press 2009. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Shen, X.; Parrot, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, C.; Yan, R.; Liu, D.; Lu, H.; Guo, F.; Huang, J. Primary joint statistical seismic influence on ionospheric parameters recorded by the CSES and DEMETER satellites. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 2020, 125, e2020JA028116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, J.; Cao, J.; Lu, L.; Wu, Y.; Yang, D. Statistical backgrounds of topside ionospheric electron density and temperature and their variations during geomagnetic activity. Chinese J. Geophys. 2011, 54, 2437–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Lei, J.; Yue, X.; Luan, X.; Dou, X. Middle-latitudinal band structure observed in the nighttime ionosphere. J. Geophys. Res. Space Physics 2019, 124, e2018JA026059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Wan, W.; Liu, L.; Zhao, B.; Wei, Y.; Yue, X.; Heelis, R. Longitudinal variations of electron temperature and total ion density in the sunset equatorial topside ionosphere. Geophysical Research Letters 2008, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Hao, y.; Zhang, D.; Zuo Xiao, Z. Nighttime enhancements in the midlatitude ionosphere and their relation to the plasmasphere. J. Geophys. Res. Space Physics 2018, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Cao, J.; Yang, J.; Berthelier, J.; Lebreton, J.-P. Semiannual and solar activity variations of daytime plasma observed by demeter in the ionosphere-plasmasphere transition region. J. Geophys. Res. Space Physics 2016, 120, e2015JA021102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Paxton, L.; Kil, H. Nightside midlatitude ionospheric arcs: TIMED/GUVI observations. J. Geophys. Res. Space Physics 2013, 118, 3584–3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X; Zhang. X. The spatial distribution of hydrogen ions at topside ionosphere in local daytime. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 2017, 28, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhou, S.; Cao, J.; Yang, J.; Berthelier, J. Large-scale depletion of nighttime oxygen ions at the low and middle latitudes in the winter hemisphere. J. Geophys. Res. Space Physics 2022, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuai, J.; Li, Q.; Zhong, J.; Zhou, X.; Liu, L.; Yoshikawa, A. , Hu, L.; Xie, H.; Huang, C.; Yu, X.; 28. Wan, X.; Cui, J. The ionosphere at middle and low latitudes under geomagnetic quiet time of December 2019. J. Geophys. Res. Space Physics 2021, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangl, G.; Boudjada, M.Y. Investigation of TEC and VLF space measurements associated to L’Aquila (Italy) earthquakes. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 11, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lu, J.; Zhang, X.; Shen, X. Indications of Ground-based Electromagnetic Observations to A Possible Lithosphere-Atmosphere-Ionosphere Electromagnetic Coupling before the 12 May 2008 Wenchuan MS 8.0 Earthquake. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, M. VLF/LF Radio Sounding of Ionospheric Perturbations Associated with Earthquakes. Sensors 2007, 7, 1141–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulinets, S.A.; Boyarchuk, K.A.; Hegai, V.V.; Kim, V.P.; Lomonosov, A.M. Quasielectrostatic model of atmosphere-thermosphere-ionosphere coupling. Adv. Space Res. 2000, 26, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayakawa, M.; Molchanov, O.A. (Eds.) Seismo-Electromagnetics: Lithosphere-Atmosphere-Ionosphere Coupling. TERRAPUB: Tokyo, Japan, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pulinets, S.; Ouzounov, D.; Karelin, A.; Davidenko, D. Lithosphere-atmosphere-ionosphere-magnetosphere coupling-a concept for pre-earthquake signals generation: a multidisciplinary approach to earthquake prediction studies. 2018.

- Parrot, M. Statistical analysis of the ion density measured by the satellite DEMETER in relation with the seismic activity. Earthq. Sci. 2011, 24, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulinets, S.A.; Legen, A.D.; Gaivoronskaya, T.V.; Depuev, V.K. Main phenomenological features of ionospheric precursors of strong earthquakes. Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics 2003, 65, 1337–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrovolsky, I.R.; Zubkov, S.I.; Myachkin, V.I. Estimation of the size of earthquake preparation zones. Pure and Applied Geophysics 1979, 117, 1025–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.I.; Chuo, Y.J.; Liu, J.Y.; Pulinets, S.A. Statistical study of ionospheric precursors of strong Earthquakes at Taiwan area. XXVIth GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE INTERNATIONAL UNION OF RADIO SCIENCE, TORONTO, 1999.

- Píša, D.; Němec, F.; Parrot, M.; Santolík, O. Attenuation of electromagnetic waves at the frequency ~1.7 kHz in the upper ionosphere observed by the DEMETER satellite in the vicinity of earthquakes. Annales de Geophysique, 2012, 55, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Píša, D.; Němec, F.; Santolík, O.; Parrot, M.; Rycroft, M. Additional attenuation of natural VLF electromagnetic waves observed by the DEMETER spacecraft resulting from preseismic activity. J. Geophys. Res. Space Physics 2013, 118, 5286–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Němec, F.; Santolík, O.; Parrot, M.; Berthelier, J.J. Spacecraft observations of electromagnetic perturbations connected with Seismic Activity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35, L05109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Němec, F.; Santolík, O.; Parrot, M. Decrease of intensity of ELF/VLF Waves observed in the upper ionosphere close to earthquakes: a statistical study. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2009, 114, A04303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Qiao, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, Y. Using a spatial analysis method to study the Seismo-Ionospheric Disturbances of Electron Density Observed by China Seismo-Electromagnetic Satellite. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 811658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Parrot, M. “Real time analysis” of the ion density measured by the satellite DEMETER in relation with the seismic activity. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Parrot, M. Statistical analysis of an ionospheric parameter as a base for earthquake prediction. J. Geophys. Res. Space Physics 2013, 118, 3731–3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Shen, X.; Parrot, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, C.; Rui Yan; Liu, D. ; Lu, H.; Guo, F.; Huang, J. Primary joint statistical seismic influence on ionospheric parameters recorded by the CSES and DEMETER satellites. J. Geophys. Res. Space Physics 2020, 125, e2020JA028116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Jiang, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, X. Temporal-spatial characteristics of seismo-ionospheric influence observed by the CSES satellite. Adv. Space Res. [CrossRef]

- Parrot, M.; Berthelier, J.J.; Lebreton, J.P.; Sauvaud, J.A.; Santolík, O.; Blecki, J. Examples of unusual ionospheric observations made by the DEMETER satellite over seismic regions. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, 2006, 31, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savitzky, A.; Golay, M.J.E. Smoothing and differentiation of data by simplified least squares procedures. Analytical Chemistry 1964, 36, 1627–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Parrot, M. Statistical analysis of the ionospheric ion density recorded by DEMETER in the epicenter areas of earthquakes as well as in their magnetically conjugate point areas. Adv. Space Res. 2018, 61, 974–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, B.; Feng, Y.; Cheng, B.; Raita, T.; Liu, J.; Zhima, Z.; Shen, X. Ionospheric Pc1 waves during a storm recovery phase observed by the China Seismo-Electromagnetic Satellite. Ann. Geophys. 2020, 38, 775–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Zhong, J.; Xiong, C.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Kuai, J.; Weng, L.; Cui, J. Persistent occurrence of strip-like plasma density bulges at conjugate lower-mid latitudes during the September 8–9, 2017 geomagnetic storm. J. Geophys. Res. Space Physics 2021, 126, e2020JA029020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Zhima, Z.; Xiong, C.; Shen, X.; Huang, J.; Guan, Y.; Zhu, X.; Liu, C. Comparison of electron density and temperature from the CSES satellite with other space-borne and ground-based observations. J. Geophys. Res. Space Physics 2020, 125, e2019JA027747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, H. On earth-currents, and their connexion with the diurnal changes of the horizontal magnetic needle. Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy 1861, 24, 115–141. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, P.H. F2 ionization and geomagnetic latitudes. Nature 1947, 160, 642–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Liu, L.; Wan, W.; Lei, J.; Zhao, B. Longitudinal modulation of the O/N2 column density retrieved from TIMED/GUVI measurement. Geophysical Research Letters 2010, 37, L20108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharenkova, I.; Cherniak, I.; Shagimuratov, I. Observations of the Weddell Sea Anomaly in the ground-based and space-borne TEC measurements. Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics 2017, 161, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, I.; Lovell, B.C. Investigating the relationships among the South Atlantic magnetic Anomaly, southern nighttime midlatitude trough, and nighttime Weddell Sea Anomaly during southern summer. J. Geophys. Res. 2009, 114(A2), A02306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Bai, C. Role of the African magnetic anomaly in controlling the magnetic configuration and its secular variation. Chinese J. Geophys 2009, 52, 1985–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xiong, C.; Wan, X.; Lai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, X.; Ou, M. Instability mechanisms for the F-region plasma irregularities inside the midlatitude ionospheric trough: Swarm observations. Space Weather 2021, 19, e2021SW002785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, T.; Luhr, H.; Kitamura, T.; Saka, O.; Schlegel, K. Direct penetration of the polar electric field to the equator during a DP 2 event as detected by the auroral and equatorial magnetometer chains and the EISCAT radar. J. Geophys. Res. 1996, 101, 17161–17173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, A. Coherence of geomagnetic DP 2 fluctuations with interplanetary magnetic variations. J. Geophys. Res. 1968, 73, 5549–5559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocke, K.; Schlegel, K. A review of atmospheric gravity waves and traveling ionospheric disturbances: 1982–1995. Annales De Geophysique 1996, 14, 917–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, A.D.; Matsushita, S. Thermospheric response to a magnetic substorm. J. Geophys. Res. 1975, 80, 2839–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R.A. The equatorial F-region of the ionosphere. Journal of Atmospheric and Terrestrial Physics 1960, 18, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Rang, X.Y.; Huang, Y.Y.; Jiang, G.Y.; Hu, K.; Luo, W.H. Latitudinal four-peak structure of the nighttime F region ionosphere: Possible contribution of the neutral wind. Reviews of Geophysics and Planetary Physics 2024, 55, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Huba, J.D.; Saito, A.; Lin, C.H.; Liu, J.Y. Theoretical study of the ionospheric Weddell sea anomaly using SAMI2. J. Geophys. Res. 2011, 116, A04305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, I.; Lovell, B.C. Investigating the relationships among the South Atlantic Magnetic Anomaly, southern nighttime midlatitude trough, and nighttime Weddell Sea Anomaly during southern summer. J. Geophys. Res. Sp. Phys. 2009, 114, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, X.; Wang, W.; Burns, A.; Solomon, S.C.; Lei, J. Midlatitude nighttime enhancement in F region electron density from global COSMIC measurements under solar minimum winter condition. J. Geophys. Res. Sp. Phys. 2008, 113, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Liu, C.H.; Liu, J.Y.; Chen, C.H.; Burns, A.G.; Wang, W. Midlatitude summer nighttime anomaly of the ionospheric electron density observed by FORMOSAT-3/COSMIC. J. Geophys. Res. 2010, 115, A03308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, M.C. The Earth’s ionosphere, plasma physics and electrodynamics. Academic 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, P.C.; Heelis, R.A.; Hanson, W.B. The ionospheric signatures of rapid subauroral ion drifts. J. Geophys. Res. 1991, 96, 5785–5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Ogawa, Y.; Kadokura, A.; Hiraki, Y.; Haggstrom, I. Seasonal variation and solar activity dependence of the quiet-time ionospheric trough. J. Geophys. Res. Sp. Phys. 2014, 119, 6774–6783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

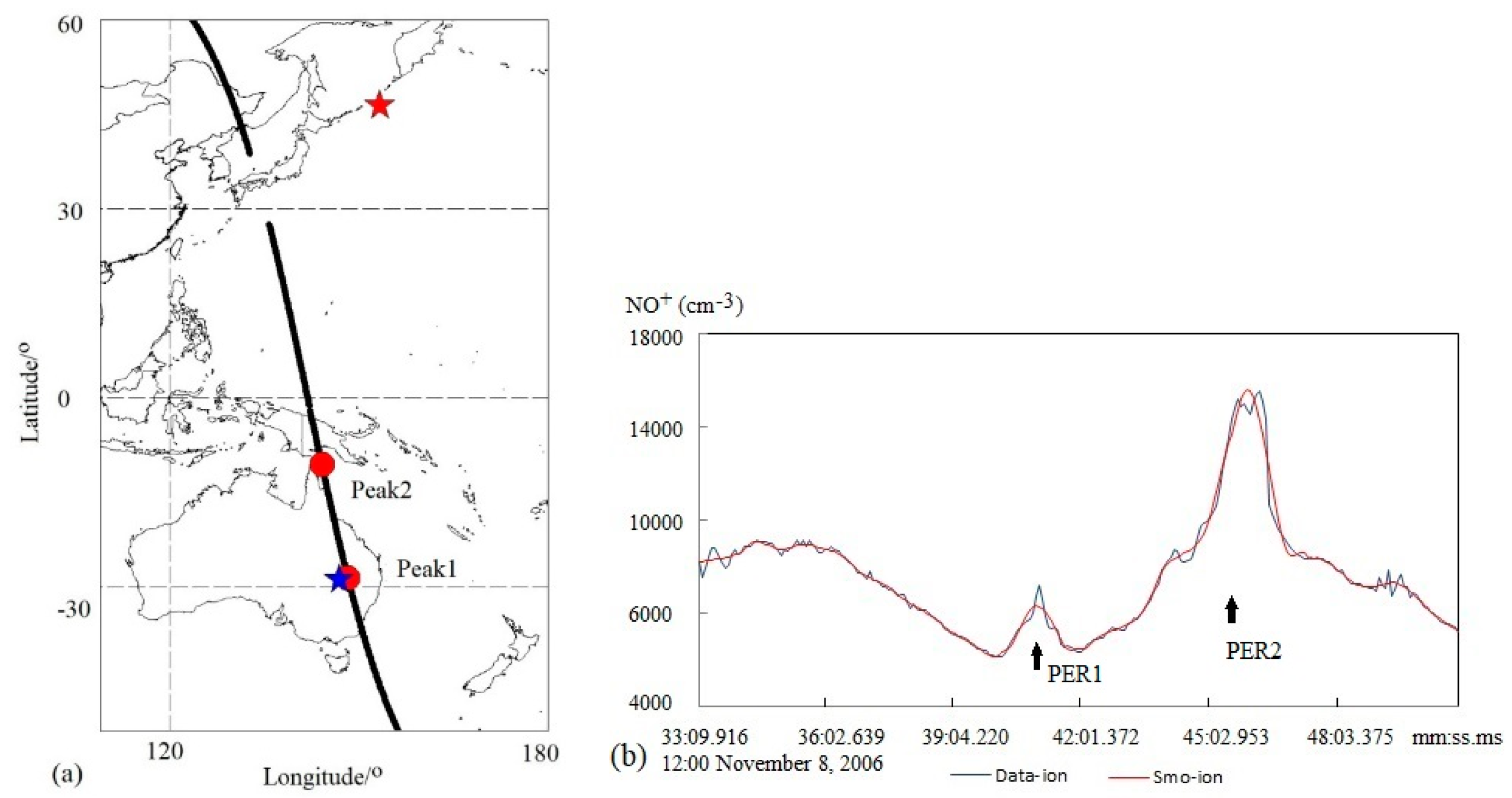

| PER1 | PER2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Date (y m d) | 2006 11 8 | 2006 11 8 |

| Time(h m s ms) | 12 41 3 797 | 12 46 0 527 |

| Orbit | 12545_1 | 12545_1 |

| Latitude (°) | -28.5122 | -10.5681 |

| Longitude (°) | 148.210 | 144.081 |

| BkgdIon (cm−3) | 4649.35 | 8378.52 |

| Amplitude(cm−3) | 6738.61 | 14763.6 |

| Trend | Increase | Increase |

| Percent (%) | 44.9 | 76.2 |

| Time_width (m s ms) | 1 37 433 | 4 56 113 |

| Extension (km) | 669 | 2036 |

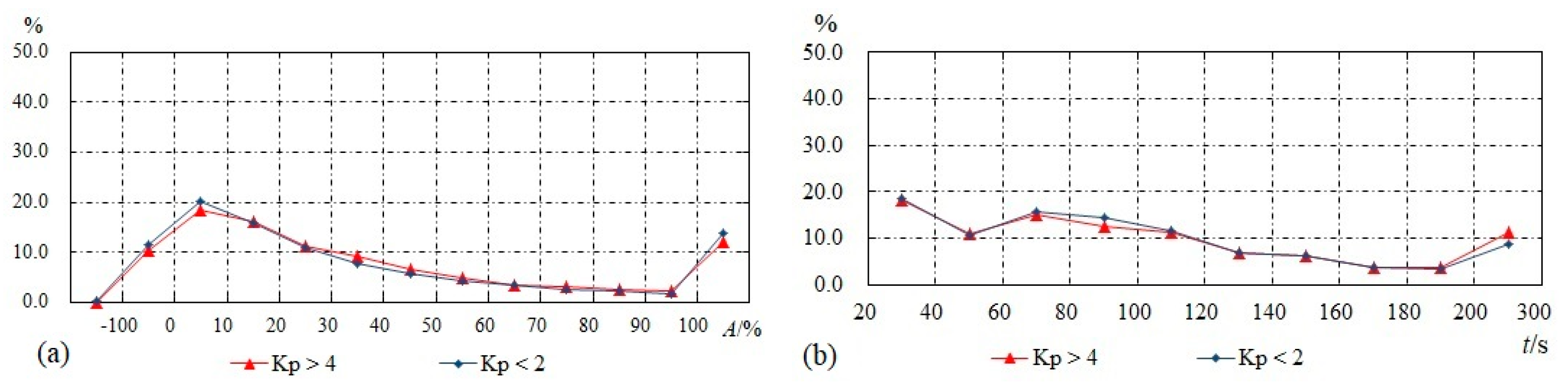

| Kp > 4 | Kp ≤ 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/% | n | p | n | p |

| ≥100 | 510 | 12.0 | 12014 | 13.8 |

| 90–100 | 100 | 2.3 | 1543 | 1.8 |

| 80–90 | 112 | 2.6 | 1872 | 2.2 |

| 70–80 | 131 | 3.1 | 2292 | 2.6 |

| 60–70 | 151 | 3.5 | 2915 | 3.3 |

| 50–60 | 211 | 4.9 | 3623 | 4.2 |

| 40–50 | 281 | 6.6 | 4850 | 5.6 |

| 30–40 | 388 | 9.1 | 6890 | 7.9 |

| 20–30 | 479 | 11.2 | 9379 | 10.8 |

| 10–20 | 684 | 16.0 | 13881 | 15.9 |

| 0–10 | 776 | 18.3 | 17529 | 20.1 |

| -100–0 | 436 | 10.3 | 10111 | 11.6 |

| <-100 | 4 | 0.1 | 158 | 0.2 |

| Kp > 4 | Kp ≤ 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t/s | n | p | n | p |

| 20–40 | 773 | 18.1 | 16045 | 18.4 |

| 40–60 | 469 | 11.0 | 9121 | 10.5 |

| 60–80 | 646 | 15.2 | 13553 | 15.6 |

| 80–100 | 536 | 12.6 | 12594 | 14.5 |

| 100–120 | 482 | 11.3 | 10200 | 11.7 |

| 120–140 | 287 | 6.7 | 6098 | 7.0 |

| 140–160 | 263 | 6.2 | 5439 | 6.2 |

| 160–180 | 164 | 3.8 | 3255 | 3.7 |

| 180–200 | 158 | 3.7 | 2994 | 3.5 |

| 200–300 | 485 | 11.4 | 7758 | 8.9 |

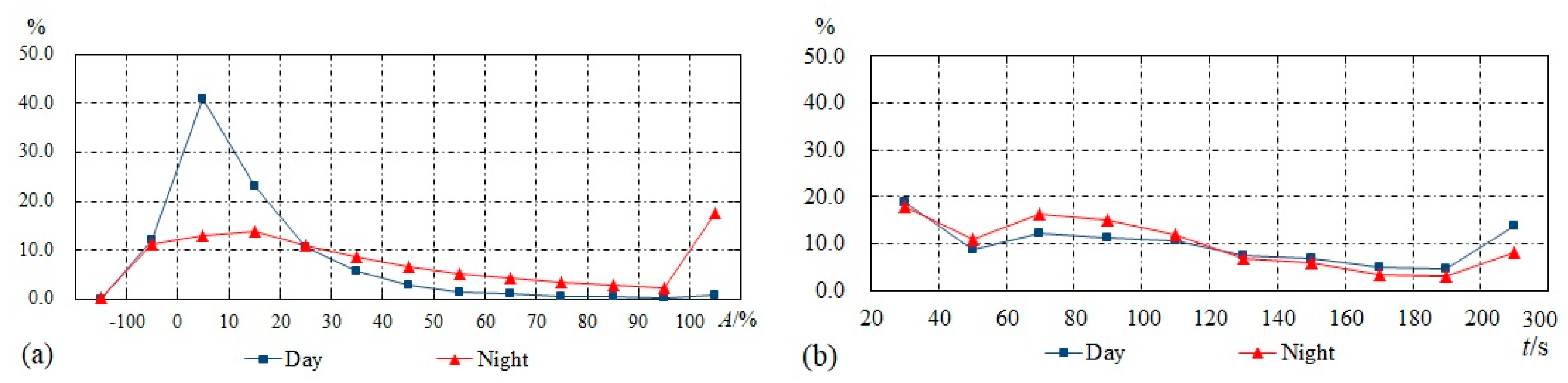

| Daytime | Nighttime | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/% | n | p | n | p |

| ≥100 | 249 | 0.9 | 15650 | 17.7 |

| 90–100 | 73 | 0.2 | 2054 | 2.4 |

| 80–90 | 116 | 0.4 | 2486 | 2.8 |

| 70–80 | 148 | 0.6 | 3011 | 3.4 |

| 60–70 | 332 | 1.1 | 3716 | 4.2 |

| 50–60 | 451 | 1.5 | 4562 | 5.2 |

| 40–50 | 844 | 2.9 | 5868 | 6.6 |

| 30–40 | 1699 | 5.8 | 7718 | 8.7 |

| 20–30 | 3104 | 10.6 | 9651 | 10.9 |

| 10–20 | 6712 | 23.0 | 12179 | 13.8 |

| 0–10 | 11983 | 41.0 | 11541 | 13.0 |

| -100–0 | 3515 | 12.0 | 9860 | 11.1 |

| < -100 | 0 | 0.0 | 196 | 0.2 |

| Daytime | Nighttime | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t/s | n | p | A/% | n |

| 20–40 | 5521 | 18.9 | 15731 | 17.8 |

| 40–60 | 2580 | 8.8 | 9714 | 11.0 |

| 60–80 | 3599 | 12.3 | 14535 | 16.4 |

| 80–100 | 3342 | 11.4 | 13478 | 15.2 |

| 100–120 | 3127 | 10.7 | 10501 | 11.9 |

| 120–140 | 2150 | 7.4 | 6130 | 6.9 |

| 140–160 | 2058 | 7.0 | 5302 | 6.0 |

| 160–180 | 1419 | 4.9 | 3130 | 3.5 |

| 180–200 | 1373 | 4.7 | 2830 | 3.2 |

| 200–300 | 4057 | 13.9 | 7141 | 8.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).