1. Introduction

The ion charge stripping system is one of the key component of the high-intensity heavy-ion beams accelerator facilities: FRIB (MSU, USA) [

1], RIBF (RIKEN, Japan) [

2] and the future

Facility for

Antiproton and

Ion

Research (FAIR, Germany) [

3].

In this article, we present a proposal for considerable improvement performance of the present gas stripper at the GSI UNILAC. The detailed description of the design and operation of this gas stripper reader can find elsewhere, for example, in [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] and links within them. That is why we will give here only its short description.

Schematic layout of the UNILAC with the gas stripper section shown in the

Figure 1 of Ref. [

4]. The following ion sources are used at GSI for production of high-intense heavy ion beams:

Penning Ion Source (PIG) for ion beams of intermediate charge state (with ion pulses length up to 6 ms and a maximum repetition rate of 50 Hz);

Multi Cusp Ion Source (MUCIS) for gaseous elements (with ion pulses length up to 3 ms and a maximum repetition rate of 17 Hz);

Metal Vapor Vacuum Arc (MEVVA) source for metallic ions. (with ion pulses length up to 3 ms and a maximum repetition rate of 17 Hz).

Electron Cyclotron Resonance (ECR) source for highly charged ions (with ion pulses length up to 6 ms and a maximum repetition rate of 50 Hz.

The ion beam having +4 charge state enter into the gas stripper after its acceleration up to the energy of 1.4 MeV/u in the UNILAC’s High Current Injector section. In the main chamber of the gas stripper ions cross the internal gas target and, in result of a number of their inelastic charge-exchange collisions with neutral atoms of the gas target, the charge states of the ions are increased. Then the beam of highly charged ions undergo the charge selection passing the fast switchable dipole magnets and its part having desired charge state is injected into the subsequent accelerating Alvarez-type section. Here the selected ion beam accelerates up to the final energy of 11.4 MeV/u.

There are two following gas stripper variants used at the GSI UNILAC.

First variant consists of operation with the continuous nitrogen gas jet flowing from the conical supersonic nozzle into the main stripper chamber (the 3D schematic of this setup shown in the

Figure 2 in Ref. [

12]). The nozzle throat diameter is 0.85 mm, the length of supersonic diverging part is 13.85 mm and the outlet diameter is 5 mm. The gas from the main stripper chamber removed by the Roots vacuum pump having capacity of 8000 m

3/h (or 2222 l/s). Four subsidiary vacuum chambers serve as a differential pumping system (two chambers in front of the stripper and two chambers behind it). Each of these subsidiary chambers pumped by Turbomolecular vacuum pumps of 1200 l/s. The ion beam cross the supersonic jet at right angle to its axis.

For the second gas stripper variant the well-known windowless storage gas cell technique is used, but here it used in the pulse operation mode. The 3D schematic of this pulsed gas stripper setup shown in the

Figure 1 in Ref. [

11] and in

Figure 2 in Ref. [

14]. It use the same vacuum system that is in use for the continuous gas jet operation. The supersonic nozzle here replaced by the pulsed gas valve, which exit aperture directly connected to the T-fitting aligned with the ion beam axis (see it in

Figure 2 of Ref. [

11]). This short T-fitting has the length of 44 mm in the ion beam direction and 21 mm aperture.

Characteristics of ion beams passed through the gas stripper at the GSI UNILAC presented in

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 in Ref. [

14]:

Figure 3 shows the charge state distributions for uranium ions stripped by nitrogen continuous jet and by helium and hydrogen at pulsed operation mode.

Figure 4 demonstrates charge state distributions for stripped uranium ions for different hydrogen target thickness and

Figure 5 show equilibrated charge state distributions for

238U,

209Bi,

50Ti, and

40Ar ions after passing the nitrogen gas jet stripper and the pulsed hydrogen target.

It is of common knowledge that the main limiting factor in the use of any internal gas targets in accelerator technology and accelerator experiments is the deterioration of the background vacuum in course of these target operation. That is why the gas stripper at the GSI UNILAC can be used with the nitrogen continuous supersonic jet when gas stagnation pressures not higher than 4 Bar.

In the variant of the pulsed gas stripper operation mode in the GSI the ion pulse repetition rate (the gas pulses are synchronized with ion pulses) no higher than 3 Hz. Another disadvantage of the pulse stripper design at the GSI is that the gas flows out of both ends of the T-fitting in the form of a pulsed supersonic jet in the direction of the ion beam (see

Figure 1 in Ref. [

11]). This can lead to additional deterioration of the vacuum in the adjacent differential pumping sections.

We sure that in order to considerably reduce the background pressures in the main chamber and differential pumping sections of the GSI UNILAC gas stripper and thus significantly improve its operation, it will be sufficient just to install downstream the supersonic nozzle a gas catcher tube having a conical entrance part. The distance between the nozzle exit and this gas catcher entrance determined by the ion beam diameter. The output of this horizontally positioned gas catcher tube from the main stripper chamber can be made through the side surface of this chamber. However, the simplest way to place the stripper components in the main vacuum chamber is as follows. The gas catcher tube and the supersonic nozzle are both located vertically. The output end of this tube is fixed in the center of the top flange, which is similar to the existing one (see

Figure 2 in Ref. [

11]). The supersonic nozzle outlet is located below the ion beam axis. For the gas pumping out of the gas catcher tube, it will be enough to connect its output through some flexible bellow with a relatively small additional Roots pump of 251 m

3/h pumping capacity.

In other words, for the gas stripper at the GSI UNILAC we suggest to apply the classic design-concept of the internal gas jet targets, where the supersonic nozzle and gas catcher are the key components. The internal gas jet targets known more than 30 years and wildly use nowadays at various accelerator experiments.

The detailed description of different internal gas jet target installations reader can find e.g. in reviews [

15,

16] and original works [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. It is worth noting here that in order for the GSI UNILAC gas stripper updated in the described manner could work in the pulse mode with high density light gases (for example, helium and hydrogen), it will be enough just to add the commercially available fast pulsed valve to the conical diverging supersonic nozzle. For example, this could be a pulse valve, described in [

24] and successfully used in our works [

22,

23]. To switch to the mode of continuous gas jet, one need just to keep the valve opened.

The goal of this article is to show how simply one can upgrade the present gas stripper setup at the GSI UNILAC for considerable improvement of its performance. To reach this goal we made a number of numerical gas dynamic simulations, which results we present and discuss in the next sections. These detailed simulations of the supersonic gas jets inside the main stripper vacuum chamber we have made with the use of the VARJET code. This code based on the solution of a full system of time dependent Navier–Stokes equations and described in detail in [

25].

Mention that results of supersonic jet measurements in [

22,

23] are in a good agreement with results of our simulations. The same we can say about a comparison of measured in [

17] thickness profile of hydrogen jet with our calculations (see

Figure 5 in Ref. [

25]). By the way, it is on the base of our gas dynamic simulations results the main design parameters of the internal gas jet target setups [

22,

23] have been determined before beginning of their construction.

2. Results for Continuous Nitrogen Jet

In order to demonstrate an advantage of the gas stripper equipped with the gas catcher tube over the present GSI UNILAC stripper variant having the supersonic nozzle we made following five calculations of the stripper operation with the continuous nitrogen gas jet:

GSI nozzle (the nozzle throat diameter is 0.85 mm, the length of supersonic diverging part is 13.85 mm and the nozzle’ exit diameter is 5 mm) at 4 bar stagnation pressure.

GSI nozzle + gas capture at 4 bar stagnation pressure.

New nozzle + gas capture (the nozzle throat diameter is 1.0 mm, the length of supersonic diverging part is 40 mm and the nozzle’ exit diameter is 8 mm) at 4 bar stagnation pressure. This long and narrow new nozzle we recommend for the using with gas catcher tube in the upgraded gas stripper at the GSI.

GSI nozzle + gas capture at 10 bar stagnation pressure.

New nozzle + gas capture at 10 bar stagnation pressure.

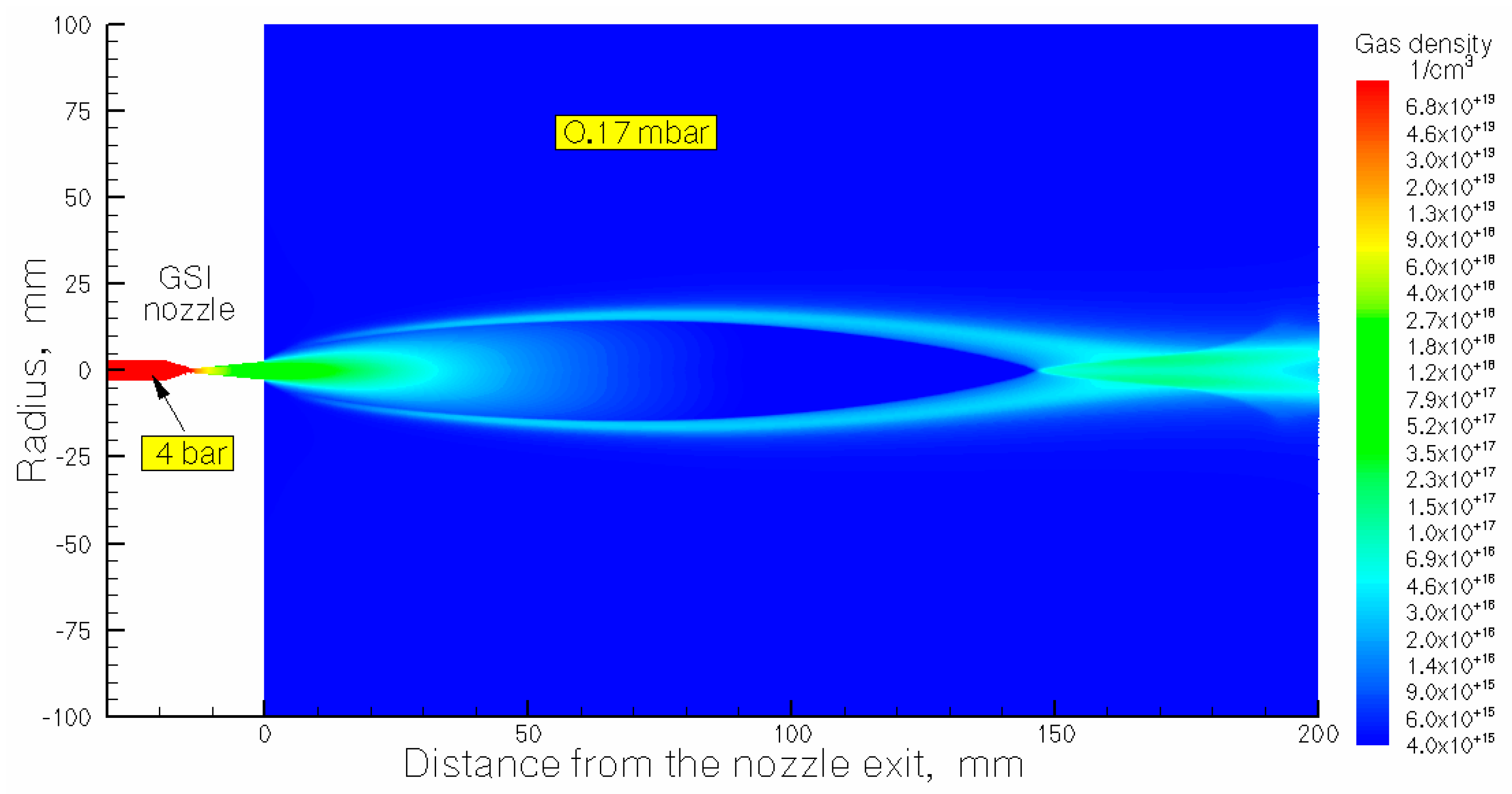

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 show for illustration results of the gas dynamic simulations for nitrogen density flow field for the 1st and 2nd calculation variants, correspondingly.

Figure 1.

Results of the gas dynamic simulation for nitrogen density flow field for GSI nozzle. The stagnation pressure and temperature are P0 = 4 bar and T0 = 296 K, correspondingly. Background pressure in the main stripper chamber Pbg = 0.17 mbar.

Figure 1.

Results of the gas dynamic simulation for nitrogen density flow field for GSI nozzle. The stagnation pressure and temperature are P0 = 4 bar and T0 = 296 K, correspondingly. Background pressure in the main stripper chamber Pbg = 0.17 mbar.

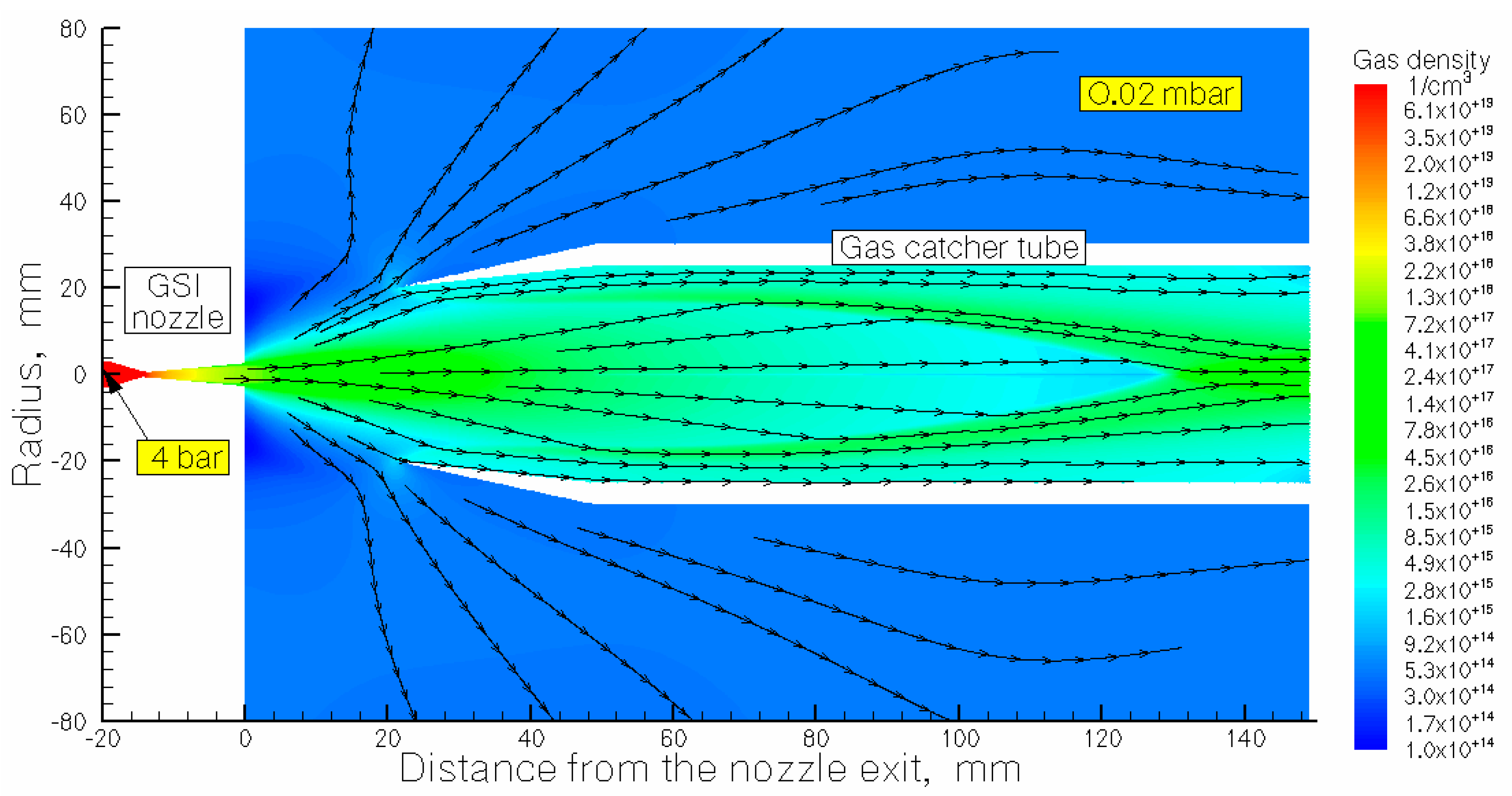

Figure 2.

Results of the gas dynamic simulation for nitrogen density flow field for the calculation variant: GSI nozzle + gas capture. The stagnation pressure and temperature are P0 = 4 bar and T0 = 296 K, correspondingly. Background pressure in the main stripper chamber Pbg = 0.02 mbar. Black arrowed lines show the gas flow directions.

Figure 2.

Results of the gas dynamic simulation for nitrogen density flow field for the calculation variant: GSI nozzle + gas capture. The stagnation pressure and temperature are P0 = 4 bar and T0 = 296 K, correspondingly. Background pressure in the main stripper chamber Pbg = 0.02 mbar. Black arrowed lines show the gas flow directions.

The gas catcher tube (see it in

Figure 2), that installed on the gas jet axis at 21 mm distance downstream the nozzle exit, have a conical entrance part of 28 mm length with entrance and exit inner diameters of 40 mm and of 50 mm, correspondingly. The thickness of the catcher tube wall does not important. The 21 mm gap between the nozzle and gas catcher tube is equal to the aperture of the T-fitting shown in

Figure 2 in Ref. [

11].

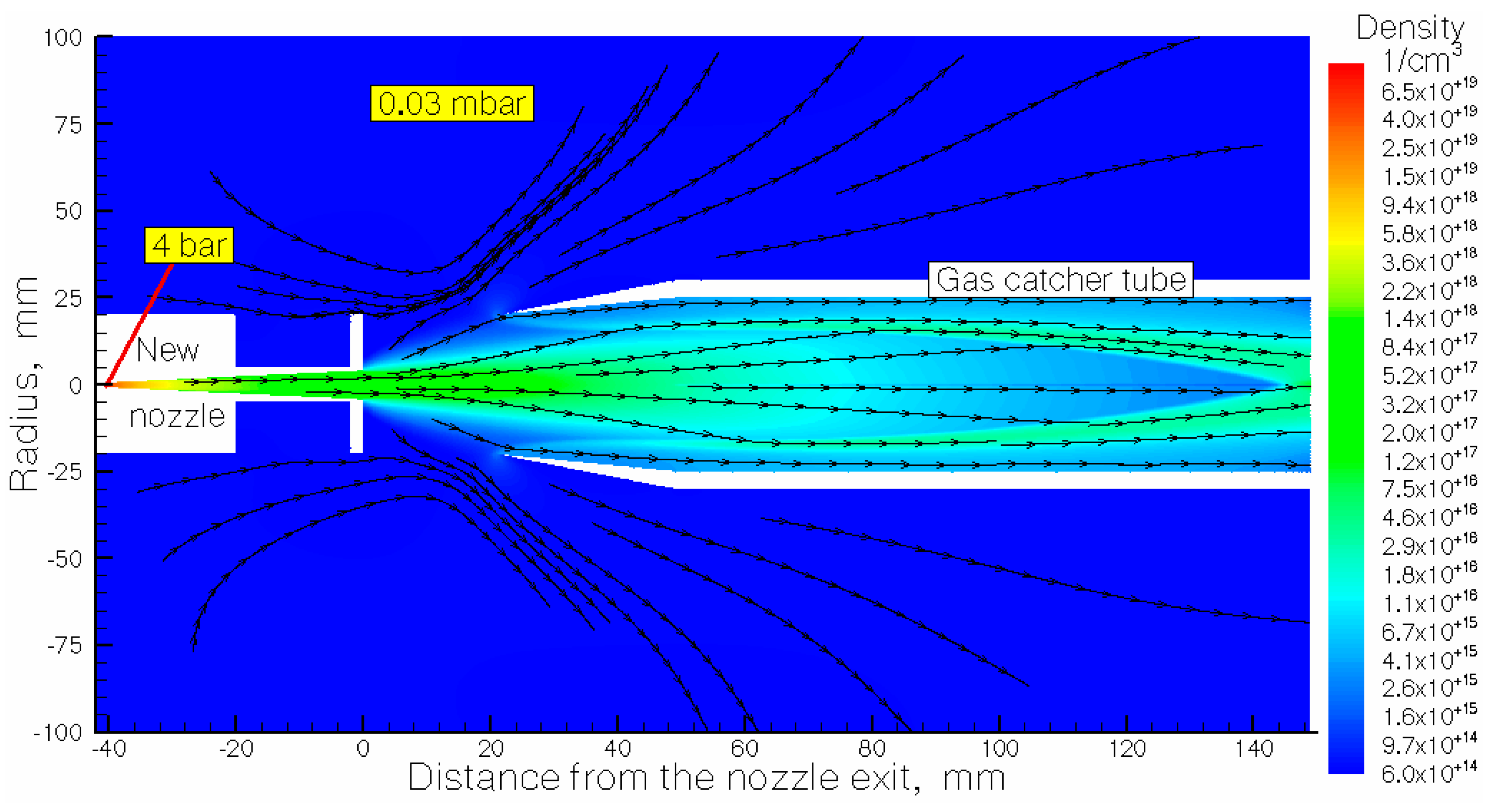

Results of the gas dynamic simulation for nitrogen density flow field for the case of 3rd calculation variant shown in

Figure 3. Notice that a disk of 40 mm outer diameter fixed to the nozzle exit as it shown in

Figure 3. The thickness of the disk does not important.

Figure 3.

Results of the gas dynamic simulation for nitrogen density flow field for the calculation variant: New nozzle + gas capture tube. The stagnation pressure and temperature are P0 = 4 bar and T0 = 296 K, correspondingly. Background pressure in the main stripper chamber Pbg = 0.03 mbar. Black arrowed lines show the gas flow directions.

Figure 3.

Results of the gas dynamic simulation for nitrogen density flow field for the calculation variant: New nozzle + gas capture tube. The stagnation pressure and temperature are P0 = 4 bar and T0 = 296 K, correspondingly. Background pressure in the main stripper chamber Pbg = 0.03 mbar. Black arrowed lines show the gas flow directions.

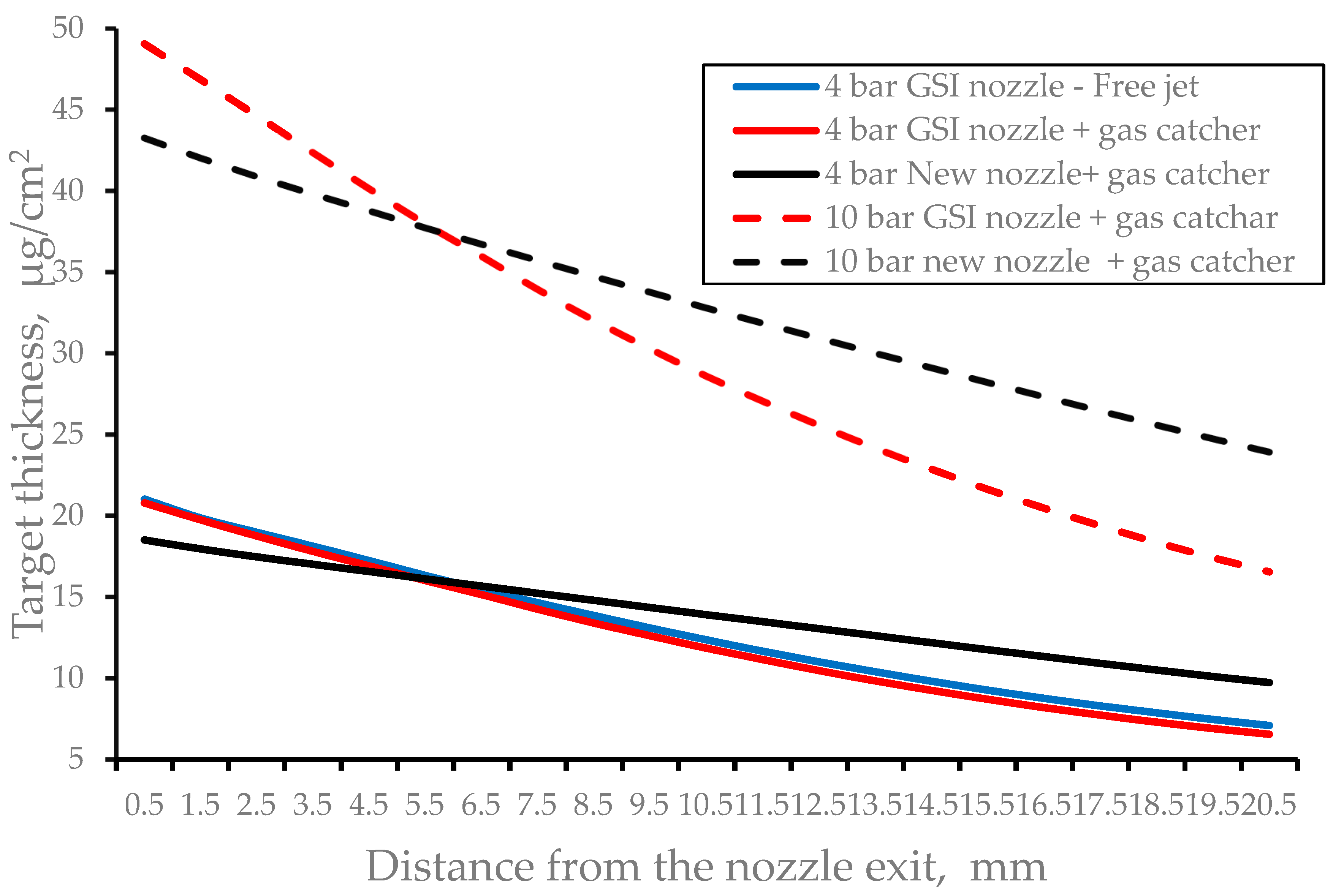

Figure 4 shows results of calculations of the nitrogen target thickness as a function of the distance from the nozzle exit for five mentioned above calculation variants of the stripper operation with continuous nitrogen gas jet. Main calculated gas flow characteristics for these five variants of the stripper operation listed in

Table 1.

Figure 4.

Results of the gas dynamic simulations of the nitrogen target thickness as a function of the distance from the nozzle for different variants of the stripper operation with the continuous nitrogen gas jet. The nozzle temperature is T0 = 296 K for all calculation variants.

Figure 4.

Results of the gas dynamic simulations of the nitrogen target thickness as a function of the distance from the nozzle for different variants of the stripper operation with the continuous nitrogen gas jet. The nozzle temperature is T0 = 296 K for all calculation variants.

Table 1.

Main calculated characteristics of the five variants of the GSI UNILAC gas stripper operation with continuous nitrogen gas jet. ”Total gas flow rate” is the nitrogen gas flow rate through the nozzle. “Background pressure” is the pressure value in the main stripper chamber. “Gas catcher efficiency” is the fraction of the total gas flow rate pumped through the gas catcher tube. “Averaged target thickness” is the nitrogen target thickness averaged over the gap between the nozzle and the catcher tube entrance. .

Table 1.

Main calculated characteristics of the five variants of the GSI UNILAC gas stripper operation with continuous nitrogen gas jet. ”Total gas flow rate” is the nitrogen gas flow rate through the nozzle. “Background pressure” is the pressure value in the main stripper chamber. “Gas catcher efficiency” is the fraction of the total gas flow rate pumped through the gas catcher tube. “Averaged target thickness” is the nitrogen target thickness averaged over the gap between the nozzle and the catcher tube entrance. .

| Calculation variant |

Total gas flow rate [mbar l/s] |

Background pressure [mbar] |

Gas catcher efficiency [%] |

Averaged target thickness [µg/cm2] |

| #1 |

377.7 |

0.17 |

- |

12.98 |

| #2 |

377.7 |

0.021 |

87.8 |

12.54 |

| #3 |

522.2 |

0.03 |

87.3 |

13.97 |

| #4 |

944.3 |

0.06 |

85.5 |

30.25 |

| #5 |

1305.5 |

0.057 |

90.3 |

33.06 |

Note that the slower slope of the target thickness curves for the new nozzle (see

Figure 4) means better thickness homogeneity of these gas targets for the ion beam passing through them.

The difference of the total gas flow rates for variants #2 and #3, as well as for #4 and #5, simply explained by the difference in throat diameters of GSI nozzle (0.85 mm) and the new nozzle (1.0 mm).

3. Results for Pulsed Gas Jet Stripper Operation Mode

In order to find out how the geometry of the supersonic nozzle affects the performance of the pulsed gas stripper, we performed gas dynamic calculations for the nozzles having different outlet diameters and lengths at for the fixed nozzle throat diameter of 1.0 mm. The calculations we made for jets of nitrogen, helium and hydrogen.

3.1. Helium Pulsed Jet Target

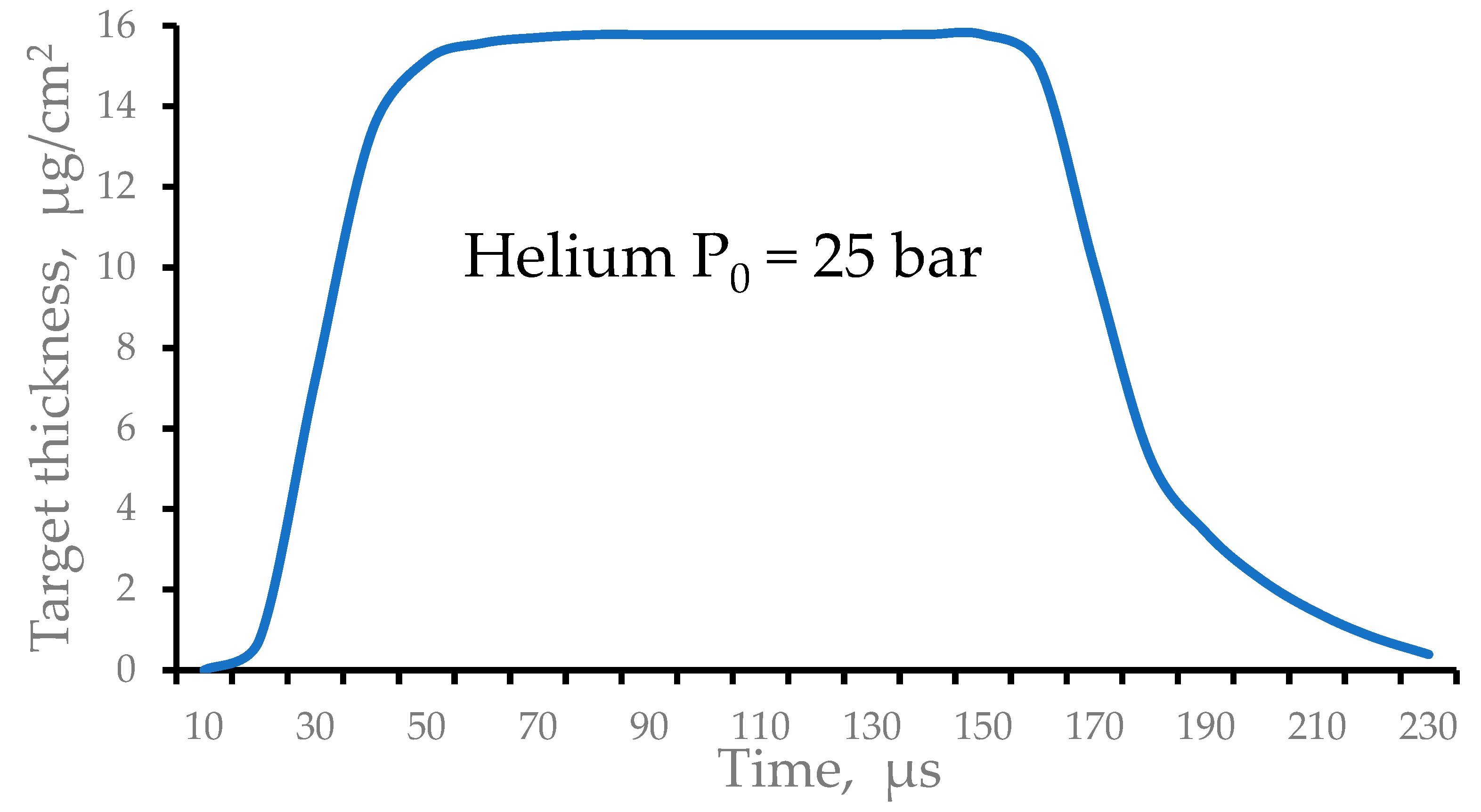

Figure 5 shows the result of calculation for the time profile of the averaged helium target thickness. The gas valve opens at zero time and closes after 150 µs. The gas pulse has a long flattop which duration is enough for the effective stripping of the pulsed ion beam of 100 µs duration.

Figure 5.

Results of the gas dynamic simulation for the time profile of the pulsed averaged helium target thickness. The gas valve opens at zero time and close at time 150 µs.

Figure 5.

Results of the gas dynamic simulation for the time profile of the pulsed averaged helium target thickness. The gas valve opens at zero time and close at time 150 µs.

It should notice, that here it is supposed that the pulsed valve is fully opened instantly (without any delay). In reality, it is not true due to a finite velocity movement of the valve's poppet at opening. However, this is not a problem to make a proper synchronization of the gas and ion beam pulses.

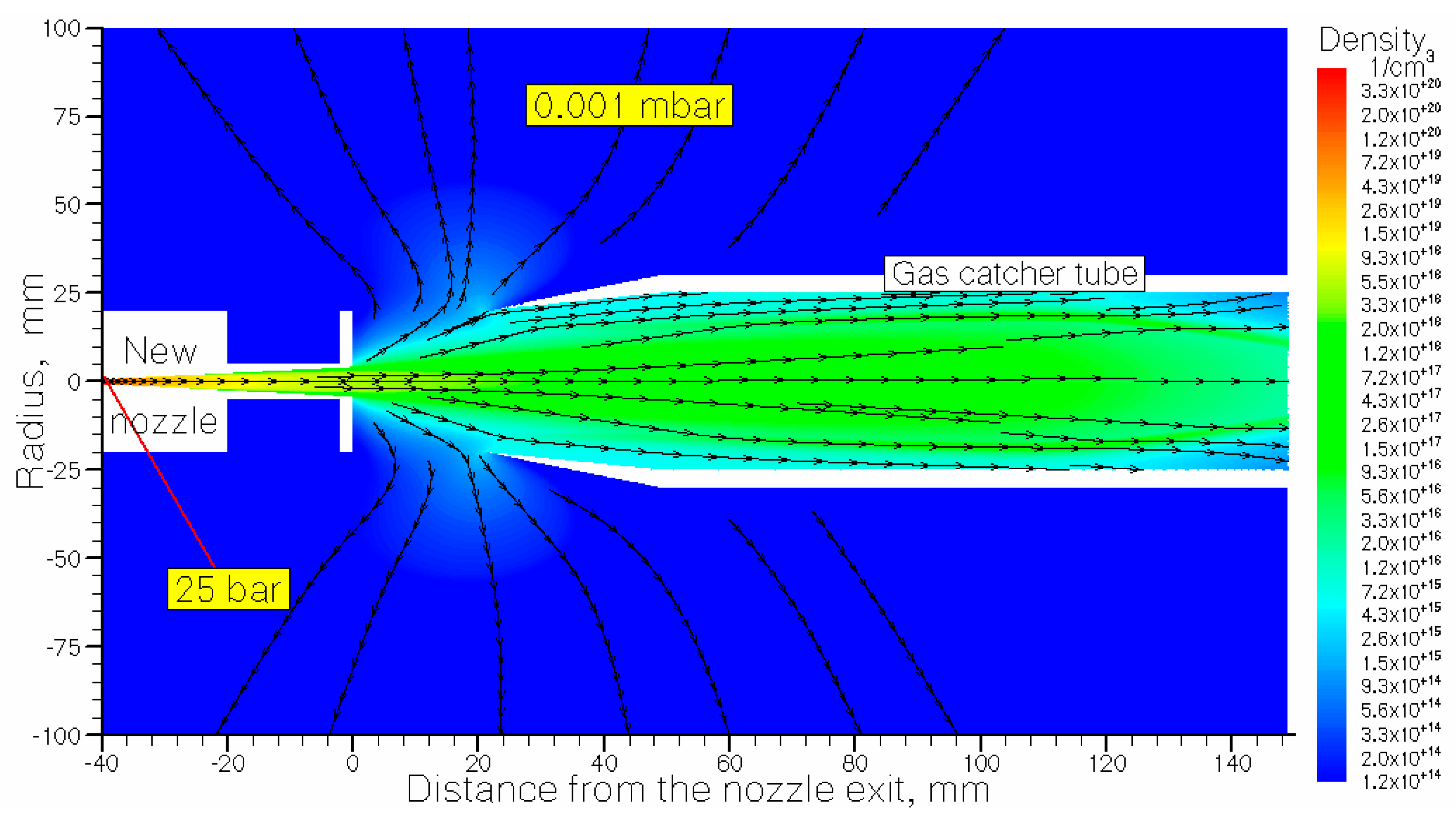

Results of the gas dynamic simulation for the helium density flow field at 100 µs after the valve opening shown in

Figure 6 for illustration.

Figure 6.

Results of the gas dynamic simulation for helium density flow field at 100 µs after the valve opening. The length of supersonic nozzle is 40 mm; its outlet diameter is 8 mm. The stagnation pressure and temperature are P0 = 25 mbar and T0 = 296 K, correspondingly. Quasi-equilibrium background gas pressure in the main stripper chamber Pbg = 0.001 mbar. Black arrowed lines show the gas flow directions.

Figure 6.

Results of the gas dynamic simulation for helium density flow field at 100 µs after the valve opening. The length of supersonic nozzle is 40 mm; its outlet diameter is 8 mm. The stagnation pressure and temperature are P0 = 25 mbar and T0 = 296 K, correspondingly. Quasi-equilibrium background gas pressure in the main stripper chamber Pbg = 0.001 mbar. Black arrowed lines show the gas flow directions.

The quasi-equilibrium background gas pressure P

bg in the main stripper chamber is determined as the following:

where

G – is the instant mass gas flow rate from the nozzle at ~100 µs after the valve opening in [mbar l/s],

f – is the ion pulse repetition rate in [Hz],

τ – is the gas pulse duration in [s] and

S - is the pumping speed of the main stripper chamber in [l/s].

Here we consider the case of the maximum possible f = 50 Hz, τ = 200 µs and S =2222 l/s (it is the present Roots pump at the GSI UNILAC).

The gas catcher efficiency for the helium pulsed jet evacuation and the averaged helium target thickness for nozzles having different lengths and outlet diameters listed in

Table 2 and

Table 3, correspondingly.

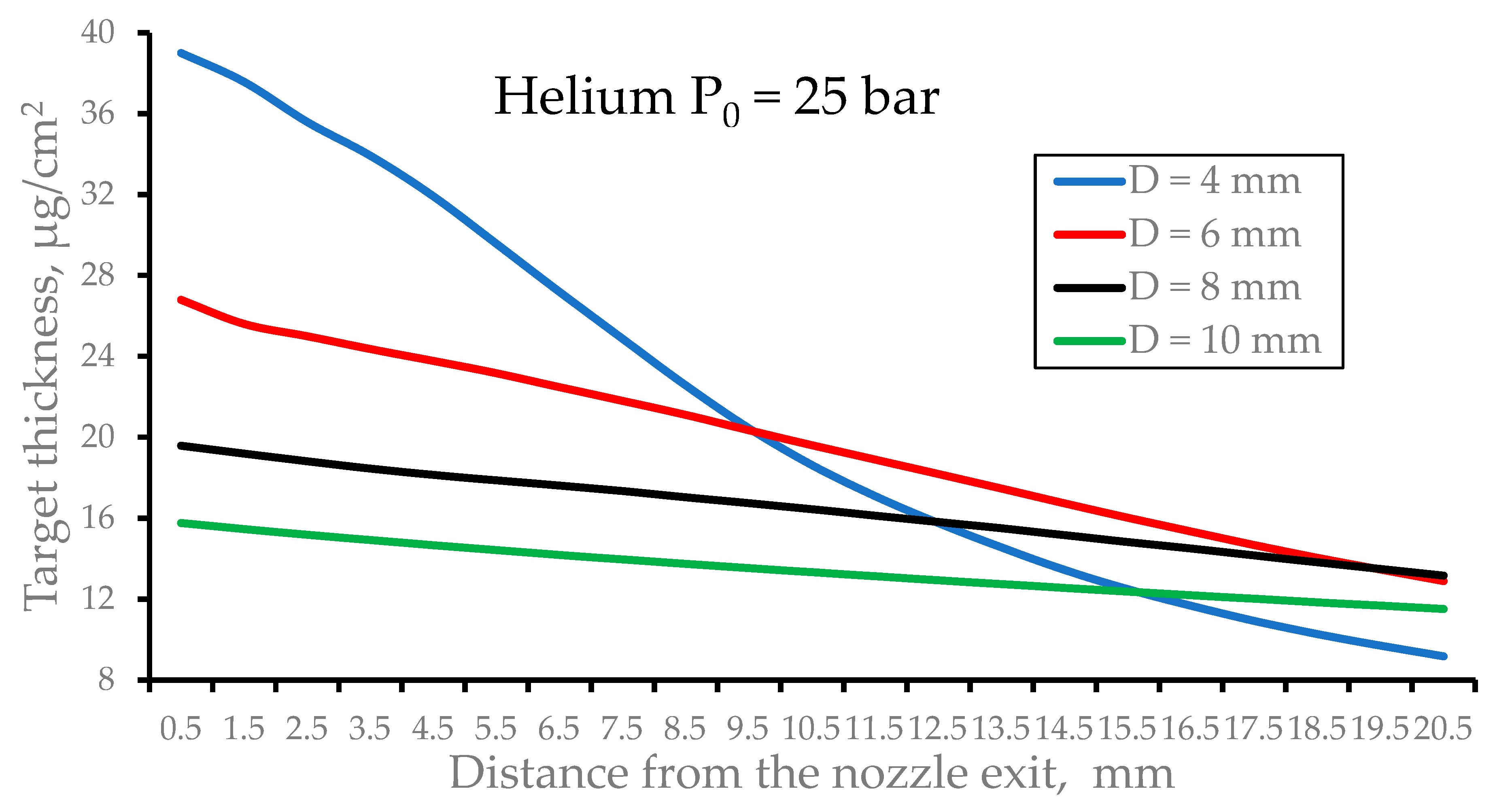

Figure 7 shows results of gas dynamic calculations for of the pulsed helium target thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for the nozzles having different outlet diameters at the fixed nozzles length.

Figure 8 shows results of gas dynamic calculations for of the pulsed helium target thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for the nozzles having different lengths at the fixed nozzles outlet diameter.

3.2. Hydrogen Pulsed Jet Target

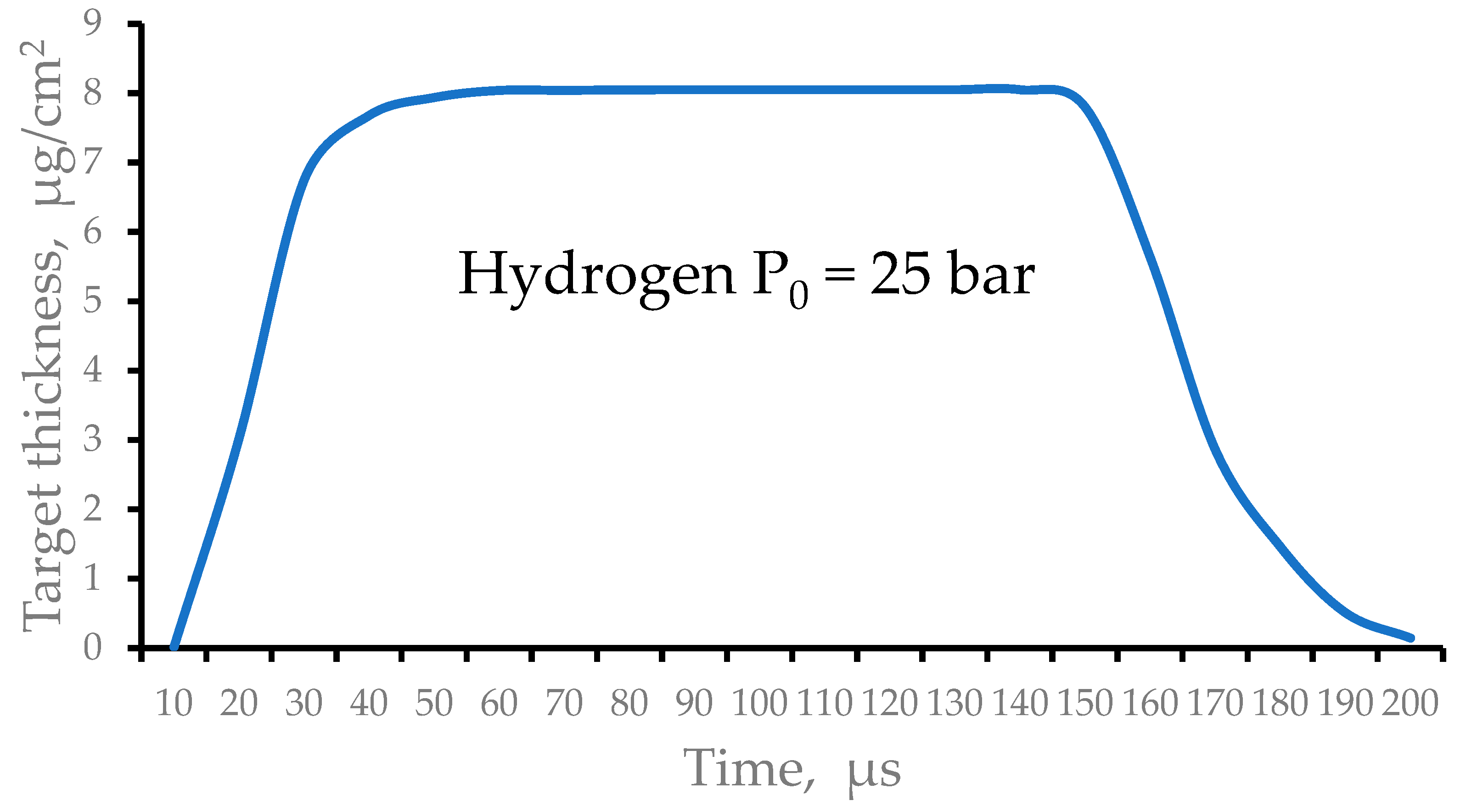

Figure 9 shows the result of calculation for the time profile of the averaged hydrogen target thickness. The gas valve opens at zero time and closes after 140 µs.

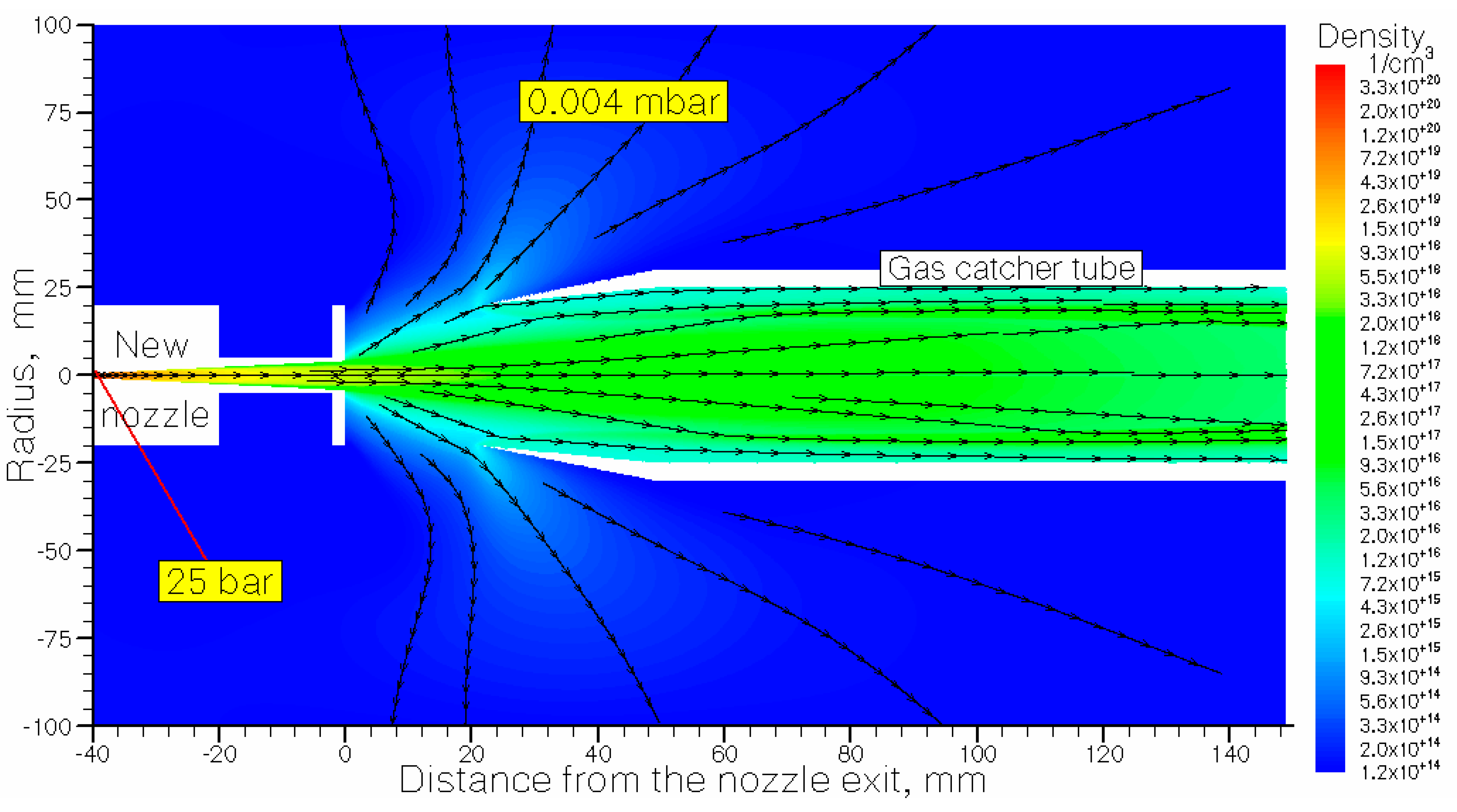

Results of the gas dynamic simulation for the hydrogen density flow field at 100 µs after the valve opening shown in

Figure 10 for illustration.

The gas catcher efficiency for the hydrogen pulsed jet evacuation and the averaged hydrogen target thickness for nozzles having different lengths and outlet diameters listed in

Table 4 and

Table 5, correspondingly.

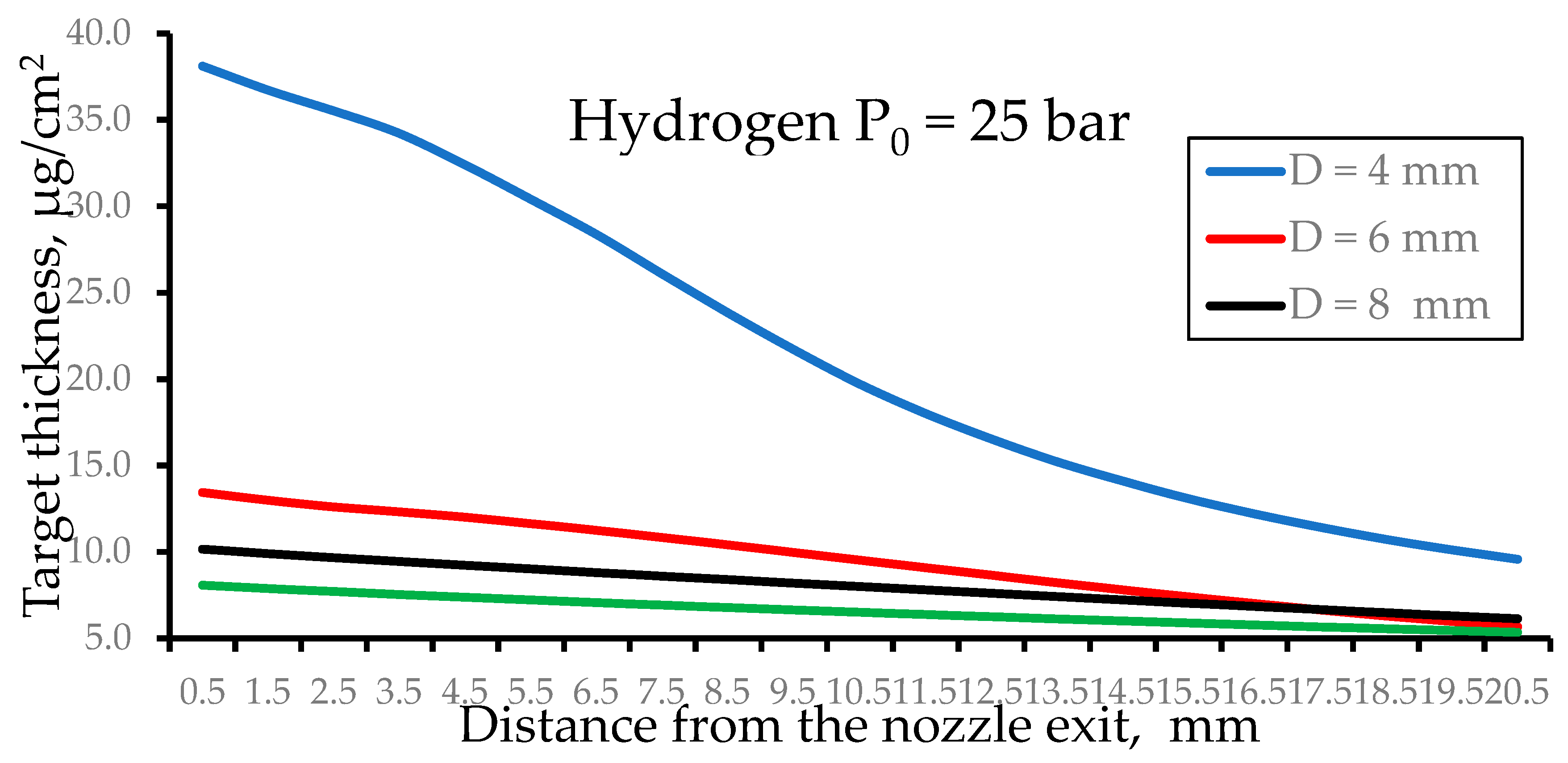

Figure 11 shows results of gas dynamic calculations for of the pulsed hydrogen target thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for the nozzles having different outlet diameters (D) at the fixed nozzles length.

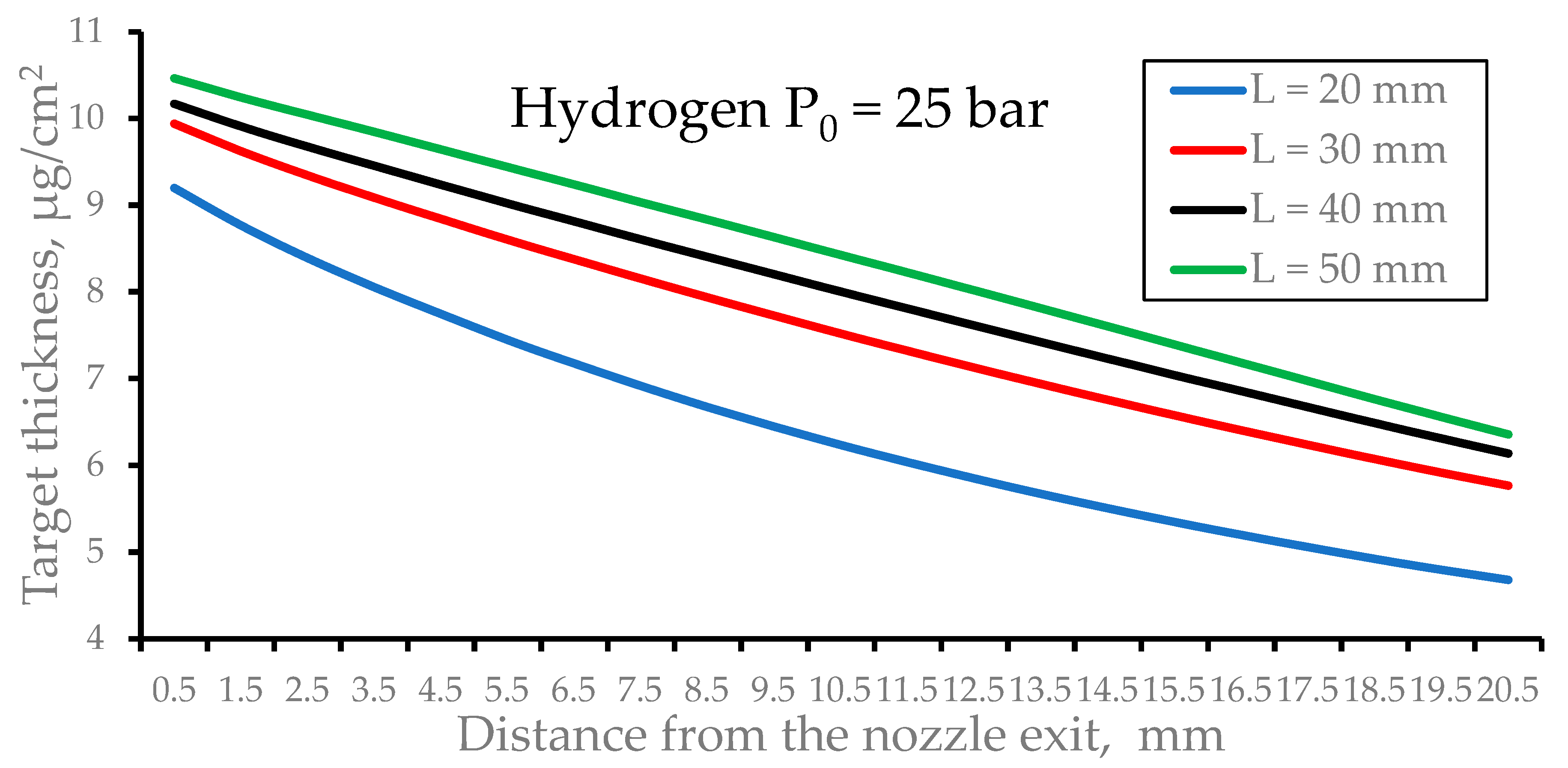

Figure 12 shows results of gas dynamic calculations for of the pulsed hydrogen target thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for the nozzles having different lengths (L) at the fixed nozzles outlet diameter.

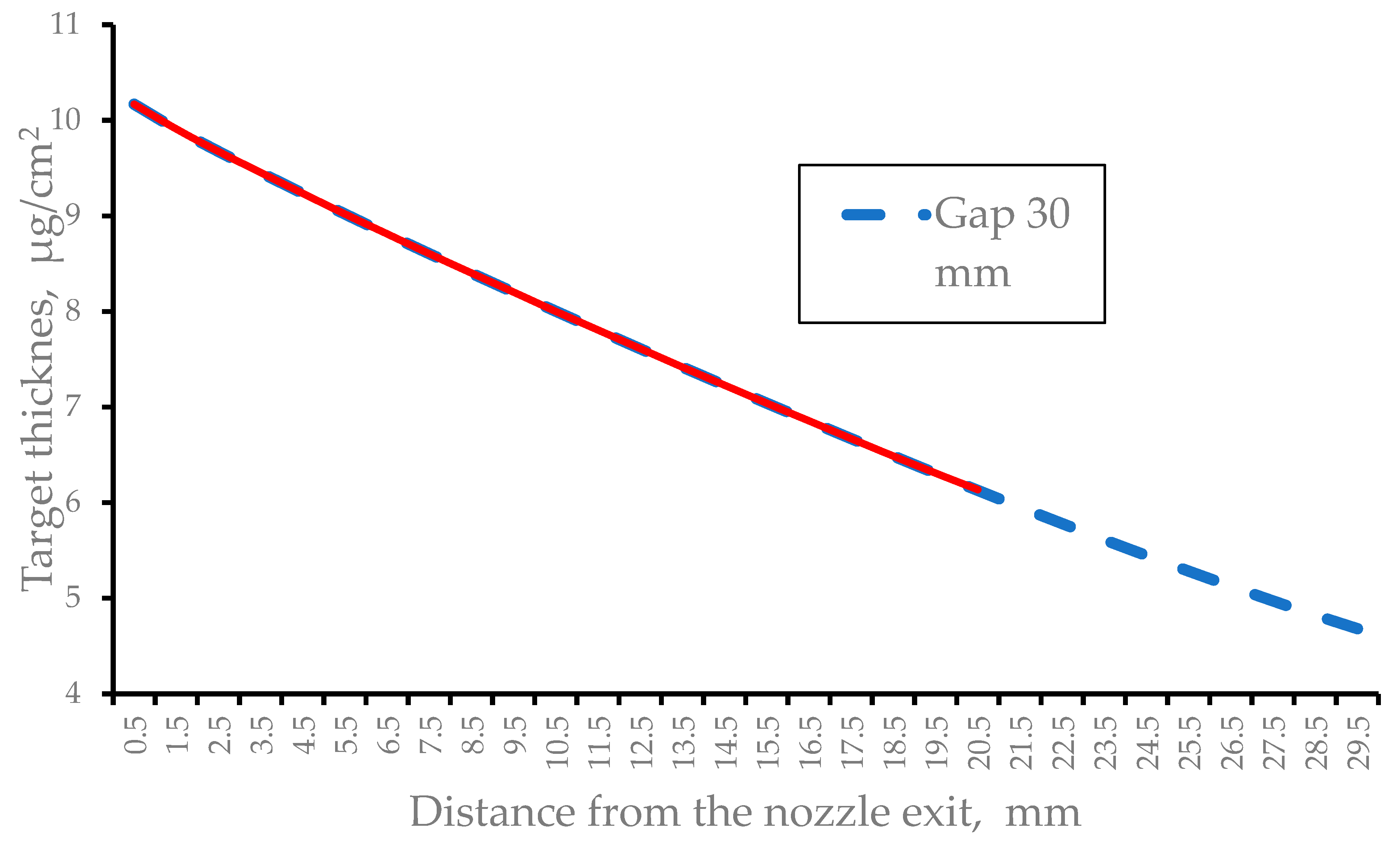

3.3. Effect of the Gap Value between the Nozzle and the Gas Catcher and of the Gas Catcher Entrance Diametr on the Gas Target Thickness

To show how the gas target thickness depend on the gap value between the nozzle exit and the gas catcher entrance we made calculation for the gap of 30 mm.

The result of this calculation for the pulsed hydrogen jet at P

0 = 25 bar (the nozzle length L = 40 mm, exit diameter D = 8mm) shown in

Figure 13. The calculation result for the gap of 21 mm (red solid line) shown here for comparison.

Notice that the both curves (the red solid and blue dashed lines) are coincide. This is simply because the disturbance of the supersonic jet caused by its interaction with the gas catcher cannot propagate upstream.

It is due to the same reason the gas target thickness do not depends on the diameter of gas catcher entrance. To be sure in it, we made additional calculations for the catcher tube entrance diameters of D = 30 mm and D = 50 mm. However the gas catcher efficiency for 30 mm catcher entrance diameter is 87.6 % that 5.8 % less compared to the catcher with D = 40 mm (see

Table 4). It also means that the gas load into main stripper chamber for the case of D = 30 mm in a factor of 2 higher compared to that one for the catcher diameter of 40 mm.

3.4. How the Gas Target Thickness Depends on the Stagnation Pressure P0

To show how the gas target thickness depends on the stagnation pressure P0 we made corresponding gas dynamic simulations for pulsed nitrogen, helium and hydrogen supersonic jets.

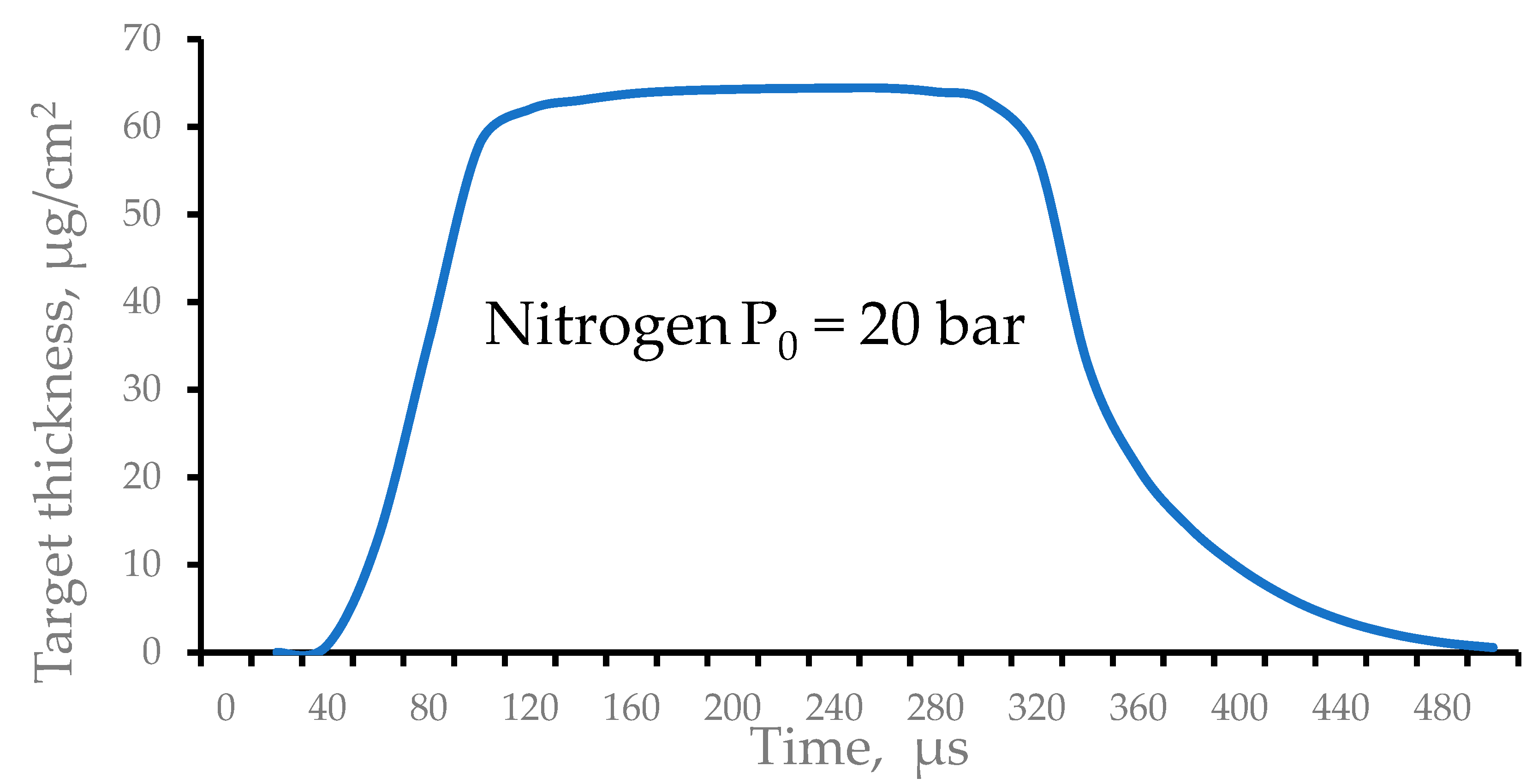

Figure 14 shows the result of calculation for the time profile of the averaged nitrogen target thickness. The gas valve opens at zero time and closes after 300 µs.

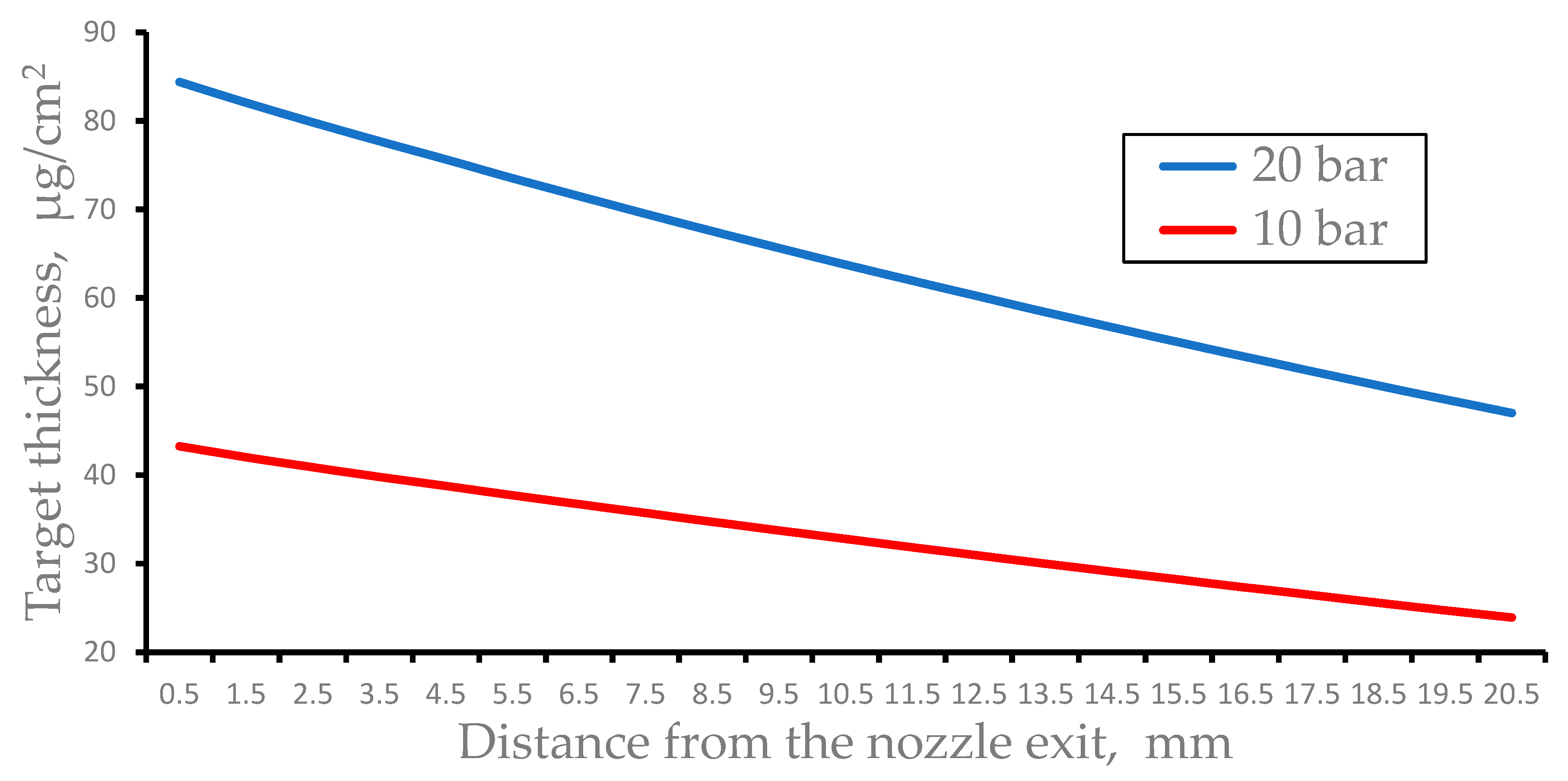

Figure 15 show the results of gas dynamic simulations of the pulsed nitrogen target thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for different stagnation pressures. The gas catcher efficiencies for 10 bar and 20 bar are equal to the 90.3 % and 89.8 %, correspondingly.

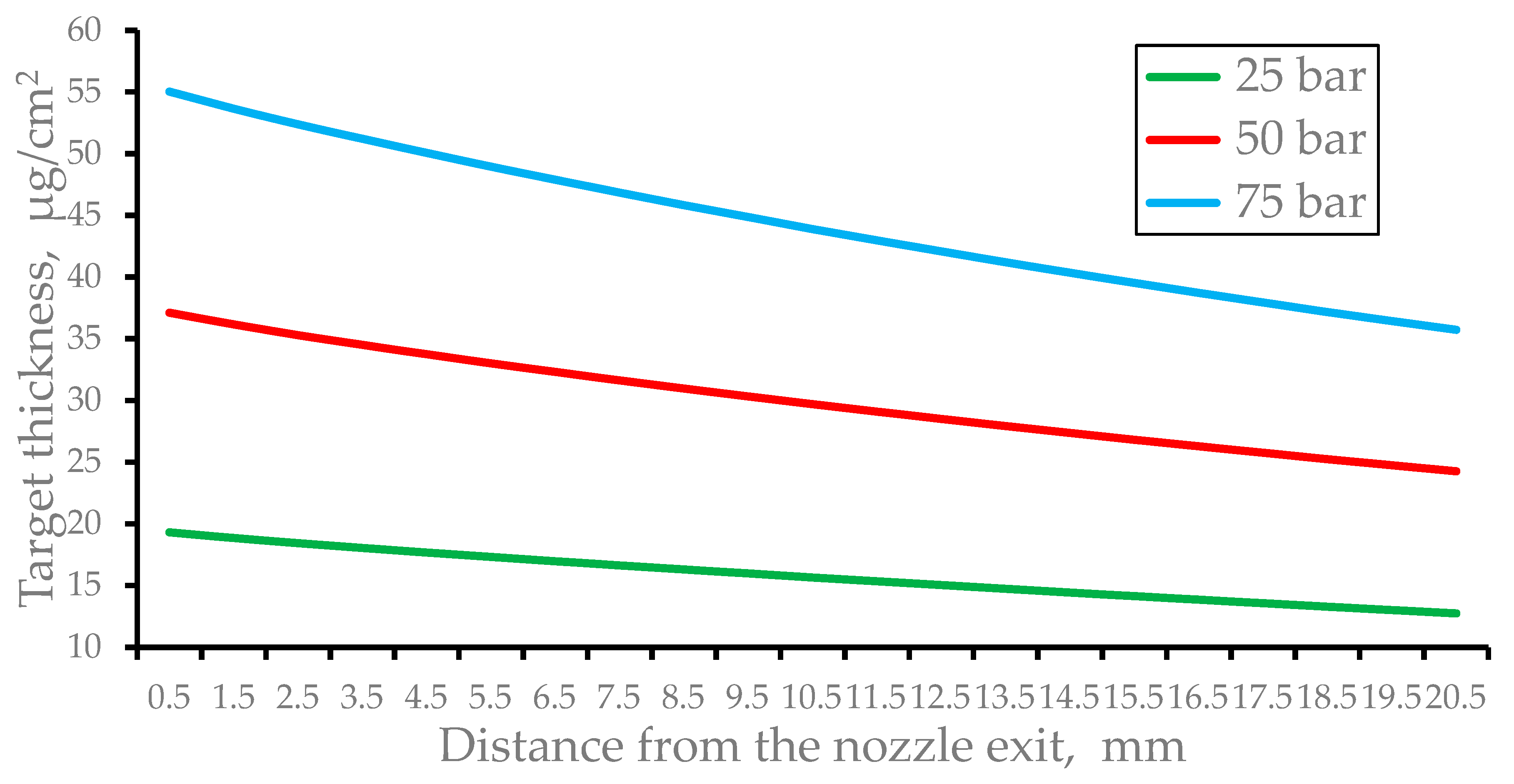

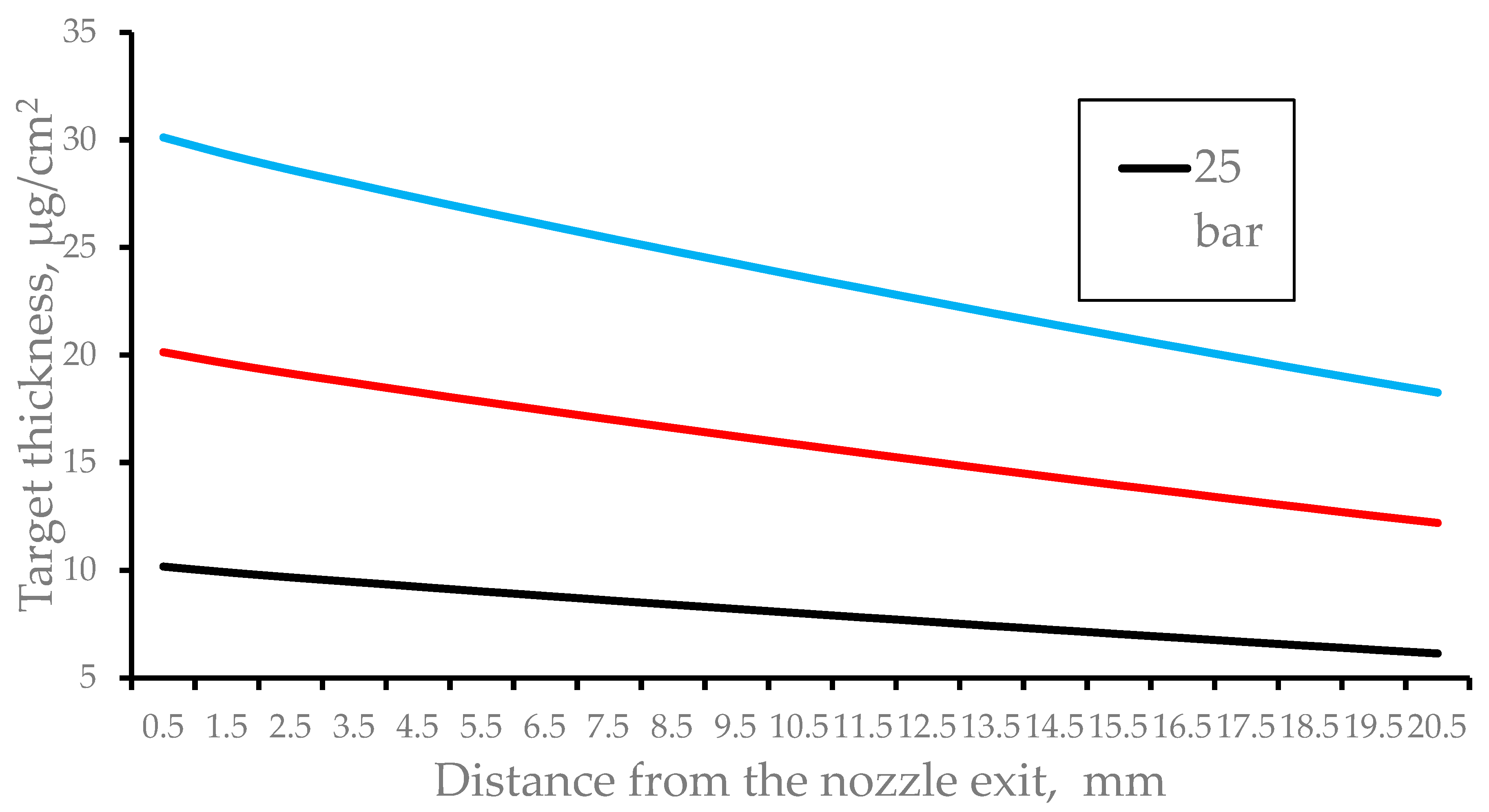

Figure 16 and

Figure 17 show the results of gas dynamic simulations of the pulsed helium and hydrogen targets thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for different stagnation pressures. The gas catcher efficiencies for these gases at the stagnation pressures of 50 bar and 75 bar are near the same as they are for the described above cases at 25 bar stagnation pressure.

4. Discussion and Outlook

In our opinion, the authors and developers of the GSI gas stripper made two big conceptual mistakes.

The first mistake has been made at the beginning of the gas stripper development, when they decided that near to all gas mass flow rate from the supersonic nozzle should be removed from the main stripper chamber by the Roots vacuum pump having capacity of 8000 m

3/h. However long before this, there were already various internal gas jet targets setups, in which the supersonic gas flow, after its crossing with the ion beam removes from the target vacuum chamber using the gas catchers of different design. These setups were well known and described, for example, in reviews [

15,

16] and original articles [

18,

21]. Notice that the work [

21] published in 1997 describes the internal gas target, which it is still in operation at the ESR GSI.

The second big mistake they made about 10 years ago at the transition to the operation of a gas stripper in pulsed mode. It was then decided to abandon the use of a supersonic nozzle, but simply use the pulse valve directly connected to the short T-fitting aligned with the ion beam axis. A short description of this pulsed gas stripper concept presented in the Introduction section.

Despite the significant advantage of using the gas stripper in pulse mode, this particular design solution, which currently in use for the gas stripper at the GSI UNI-LAC, suffers from the same disadvantage associated with the vacuum limitation. An additional drawback here is that the gas flies out the T-fitting in the direction of the apertures of adjacent differential pumping chambers (see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 in Ref. [

11]) in form of pulsed supersonic jet. Therefore, we think that it would be better simply continue the use the gas stripper with supersonic nozzle, providing it with a fast pulse valve at the inlet. Moreover, the opening time of the valve required for effective operation with ion pulses of 100 µs duration could then be less.

In this article, we propose a simple way in which one can considerably improve the performance of the gas stripper setup at the GSI UNILAC. It consists in the use of the classic and well-known design concept of internal gas jet targets, in which the gas jet catcher installed at some downstream distance from the supersonic nozzle exit. This distance (or the gap between the nozzle exit and the gas catcher entrance) mainly determined by the size of the ion beam crossing the gas jet at right angle.

The functionality of the proposed GSI UNILAC gas stripper modification we explored by detailed gas dynamic simulations, which allowed us to determine the optimal nozzle and the gas catcher tube geometry. The both these key elements of the gas stripper can be installed inside the existing main vacuum chamber of the gas stripper setup.

E.g., we recommend using the simple conical supersonic diverging nozzle having the throat diameter, length and exit diameter of 1 mm, 40 mm and 8 mm, correspondingly.

For entrance diameter of the conical part of the gas catcher tube, we recommend the value of 40 mm.

To evacuate the gas out of the gas catcher tube it will be enough to use an additional relatively small Roots pump of 251 m3/h pumping capacity, that is 32 times less than the existing at the gas stripper GSI UNILAC Roots pump.

The calculated gas catcher efficiencies in the pulse operation mode are about 98% for helium and 93% for hydrogen. It allows dramatically decrease the background pressure in the main stripper vacuum chamber and, in result, increase the use of higher than at present repetition rates of the ion beams.

We very hope that people in GSI, who are responsible for the gas stripper, will follow this article’s recommendations in the course of the next and probably final upgrade of the present gas stripper setup. This upgrade should not be expensive and time consuming.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the

author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest

References

- T. Kanemura, J. Gao, M. LaVere, R. Madendorp, F. Marti, Y. Momozaki, PROGRESS OF LIQUID LITHIUM STRIPPER FOR FRIB, North American Particle Acc. Conf. NAPAC2019, Lansing, MI, USA (2019) 636-638, . [CrossRef]

- H. Imao, H. Okuno, H. Kuboki, S. Yokouchi, N. Fukunishi, O. Kamigaito, H. Hasebe, T. Watanabe, Y. Watanabe, M. Kase, Y. Yano, CHARGE STRIPPING OF URANIUM-238 ION BEAM WITH HELIUM GAS STRIPPER, Proceedings of IPAC2012, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA (2012) 3930-3932.

- FAIR Baseline Technical Report, Vol. 2, GSI Darmstadt, Germany (2006), p. 335.

- J. Glatz, J. Klabunde, U. Scheeler, D. Wilms, Operational aspects of the high current upgrade UNILAC Proceedings of Linear Accelerator Conference, Monterey, U.S.A (2000) 232–234.

- W. Barth, P. Forck, The new gas stripper and charge state separator of the GSI high current injector, Proceedings of Linear Accelerator Conference, Monterey, U.S.A (2000) 235–237.

- P. Gerhard, M. Maier, ON THE UNILAC PULSED GAS STRIPPER AT GSI, 31st Int. Linear Accel. Conf. LINAC2022, Liverpool, UK, (2022) 258-261,. [CrossRef]

- W. Barth, M. Miski-Oglu, U. Scheeler, H. Vormann, M. Vossberg, S. Yaramyshev, UNILAC HEAVY ION BEAM OPERATION AT FAIR INTENSITIES, 31st Int. Linear Accel. Conf. LINAC2022, Liverpool, UK (2022) 102-105, . [CrossRef]

- W. Barth, A. Adonin, Ch. E. Düllmann, M. Heilmann, R. Hollinger, E. Jäger, O. Kester, J. Khuyagbaatar, J. Krier, E. Plechov, P. Scharrer, W. Vinzenz, H. Vormann, A. Yakushev, and S. Yaramyshev, High brilliance uranium beams for the GSI FAIR, PHYS. REV. ACCEL. BEAMS 20, 050101 (2017) 1-4, . [CrossRef]

- W. Barth, R. Hollinger, A. Adonin, M. Miski-Oglu, U. Scheeler and H. Vormann, LINAC developments for heavy ion operation at GSI and FAIR, Journal of Instrumentation, 15 (2020) T12012, . [CrossRef]

- Scharrer, E. Jäger, W. Barth, M. Bevcic, C. E. Düllmann, L. Groening, K.-P. Horn, J. Khuyagbaatar, J. Krier, and A. Yakushev, Electron stripping of Bi ions using a modified 1.4 MeV/u gas stripper with pulsed gas injection, J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 305 (2015) 837-842.

- P. Scharrer1, W. Barth, M. Bevcic, Ch. E. Düllmann, L. Groening, K. P. Horn, E. Jäger, J. Khuyagbaatar, J.

Krier, A. Yakushev, Stripping of high intensity heavy-ion beams in a pulsed gas stripper device at1.4MeV/u, Proceedings of IPAC2015, Richmond, VA, USA (2015) 3773-3775.

- Winfried Barth, Aleksey Adonin, Christoph E. Düllmann, Manuel Heilmann, Ralph Hollinger, Egon Jäger, Jadambaa Khuyagbaatar, Joerg Krier, Paul Scharrer, Hartmut Vormann and Alexander Yakushev, U28+-intensity record applying a H2-gas stripper cell, Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 18 040101 (2015) 1-9.

- P. Scharrer1, W. Barth, M. Bevcic, Ch. E. Düllmann, P. Gerhard, L. Groening, K. P. Horn, E. Jäger, J. Khuyagbaatar, J. Krier, H. Vormann, A. Yakushev, Applications of the pulsed gas stripper technique at the GSI UNILAC, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 863 (2017) 20-25, . [CrossRef]

- P. Gerhard, W. Barth, M. Bevcic, Ch. E. Düllmann, L. Groening, K. P. Horn, E. Jäger, J. Khuyagbaatar, J. Krier, M. Maier, P. Scharrer, A. Yakushev, DEVELOPMENT OF PULSED GAS STRIPPERS FOR INTENSE BEAMS OF HEAVY AND INTERMEDIATE MASS IONS, 29th Linear Accelerator Conf. LINAC2018, Beijing, China (2018) 982-987, . [CrossRef]

- M. Macri, Gas Jet Internal Target, CERN Acceleration School – Antiprotons for Colliding Beam Facilities, Geneva, Switzerland, 1983, Report CERN 84-15 (1984), ed. P. Bryant and S. Newman, p. 469.

- C. Ekström, Internal targets - a review, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 362 (1995) 1-16, . [CrossRef]

- J.E. Doskov, F. Sperisen, Development of internal jet targets for high-luminosity experiments, Nucl. Instr. and Meth. A 362 (1995) 20-25. [CrossRef]

- Antonios Kontos, Daniel Schürmann, Charles Akers, Manoel Couder, Joachim Görres, Daniel Robertson, Ed Stech, Rashi Talwar, Michael Wiescher, HIPPO: A supersonic helium jet gas target for nuclear astrophysics, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 664 (2012) 272–281, . [CrossRef]

- Zach Meisela, Ke Shi, Aleksandar Jemcov, Manoel Couder, Exploratory investigation of the HIPPO gas-jet target fluid dynamic properties, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 828 (2016) 8–14, . [CrossRef]

- K. Schmidt, K.A. Chipps, S. Ahn, D.W. Bardayan, J. Browne, U. Greife, Z. Meisel, F. Montes, P.D. O’Malley, W-J. Ong, S.D. Pain, H. Schatz, K. Smith, M.S. Smith, P.J. Thompson, Status of the JENSA gas-jet target for experiments with rare isotope beams, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 911 (2018) 1–9, . [CrossRef]

- H. Reich, W. Bourgeois, B. Franzke, A. Kritzer, V. Varentsov, The ESR internal target, Nuclear Physics A 626 (1997) 417-425.

- V.L. Varentsov, N. Kuroda, Y. Nagata, H. A. Torii, M. Shibata, and Y. Yamazaki, ASACUSA Gas-Jet Target: Present Status And Future Development, AIP Conference Proceedings 793 (2005) 328-340, . [CrossRef]

- D. Tiedemann, K.E. Stiebing, D.F.A. Winters, W. Quint, V. Varentsov, A. Warczak, A. Malarz, Th. Stöhlker, A pulsed supersonic gas jet target for precision spectroscopy at the HITRAP facility at GSI, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 764 (2014) 387–393,. [CrossRef]

- Parker Hannifin Corp., https://ph.parker.com/us/en/divisions/precision-fluidics-division-page/product/pulse-valves-miniature-high-speed-high-vacuum-dispense-valve/009-1669-900.

-

V.L. Varentsov, A.A. Ignatiev, Numerical investigations of internal supersonic jet targets formation for storage rings, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 413 (1998) 447-456,. [CrossRef]

Figure 7.

Results of gas dynamic simulations of the pulsed helium target thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for the nozzles having different outlet diameters (D) at the fixed nozzle length (L = 40 mm). The stagnation pressure P0 = 25 bar and the nozzle temperature T0 = 296 K for all calculation variants. Time after the valve opening is 100 µs.

Figure 7.

Results of gas dynamic simulations of the pulsed helium target thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for the nozzles having different outlet diameters (D) at the fixed nozzle length (L = 40 mm). The stagnation pressure P0 = 25 bar and the nozzle temperature T0 = 296 K for all calculation variants. Time after the valve opening is 100 µs.

Figure 8.

Results of gas dynamic simulations of the pulsed helium target thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for the nozzles having different nozzles lengths (L) at the fixed nozzle outlet diameter (D = 8 mm). The stagnation pressure P0 = 25 bar and the nozzle temperature T0 = 296 K for all calculation variants. Time after the valve opening is 100 µs.

Figure 8.

Results of gas dynamic simulations of the pulsed helium target thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for the nozzles having different nozzles lengths (L) at the fixed nozzle outlet diameter (D = 8 mm). The stagnation pressure P0 = 25 bar and the nozzle temperature T0 = 296 K for all calculation variants. Time after the valve opening is 100 µs.

Figure 9.

Results of the gas dynamic simulations of the time profile of the averaged hydrogen target thickness. The gas valve opens at zero time and close at time 140 µs.

Figure 9.

Results of the gas dynamic simulations of the time profile of the averaged hydrogen target thickness. The gas valve opens at zero time and close at time 140 µs.

Figure 10.

Results of the gas dynamic simulation for hydrogen density flow field at 100 µs after the valve opening. The length of supersonic nozzle is 40 mm; its outlet diameter is 8 mm. The stagnation pressure and temperature are P0 = 25 mbar and T0 = 296 K, correspondingly. Quasi-equilibrium background pressure Pbg in the main stripper chamber is 0.004 mbar. Black arrowed lines show the gas flow directions.

Figure 10.

Results of the gas dynamic simulation for hydrogen density flow field at 100 µs after the valve opening. The length of supersonic nozzle is 40 mm; its outlet diameter is 8 mm. The stagnation pressure and temperature are P0 = 25 mbar and T0 = 296 K, correspondingly. Quasi-equilibrium background pressure Pbg in the main stripper chamber is 0.004 mbar. Black arrowed lines show the gas flow directions.

Figure 11.

Results of gas dynamic simulations of the pulsed hydrogen target thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for the nozzles having different outlet diameters (D) at the fixed nozzles length (L = 40 mm). The stagnation pressure P0 = 25 bar and the nozzle temperature T0 = 296 K for all calculation variants. Time after the pulsed valve opening is 100 µs.

Figure 11.

Results of gas dynamic simulations of the pulsed hydrogen target thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for the nozzles having different outlet diameters (D) at the fixed nozzles length (L = 40 mm). The stagnation pressure P0 = 25 bar and the nozzle temperature T0 = 296 K for all calculation variants. Time after the pulsed valve opening is 100 µs.

Figure 12.

Results of gas dynamic simulations of the pulsed hydrogen target thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for the nozzles having different nozzles lengths (L) at the fixed nozzles outlet diameter (D = 8 mm). The stagnation pressure P0 = 25 bar and the nozzle temperature T0 = 296 K for all calculation variants. Time after the pulsed valve opening is 100 µs.

Figure 12.

Results of gas dynamic simulations of the pulsed hydrogen target thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for the nozzles having different nozzles lengths (L) at the fixed nozzles outlet diameter (D = 8 mm). The stagnation pressure P0 = 25 bar and the nozzle temperature T0 = 296 K for all calculation variants. Time after the pulsed valve opening is 100 µs.

Figure 13.

Results of gas dynamic simulations of the pulsed hydrogen target thickness for the gap between the nozzle exit and the gas catcher entrance of 30 mm. The nozzle length L = 40 mm, exit diameter D = 8mm. The stagnation pressure P0 = 25 bar and the nozzle temperature T0 = 296 K. The red solid line show result of calculation for the gap of 21 mm for comparison. The time after the pulsed valve opening is 100 µs.

Figure 13.

Results of gas dynamic simulations of the pulsed hydrogen target thickness for the gap between the nozzle exit and the gas catcher entrance of 30 mm. The nozzle length L = 40 mm, exit diameter D = 8mm. The stagnation pressure P0 = 25 bar and the nozzle temperature T0 = 296 K. The red solid line show result of calculation for the gap of 21 mm for comparison. The time after the pulsed valve opening is 100 µs.

Figure 14.

Results of the gas dynamic simulations of the time profile of the averaged nitrogen target thickness. The gas valve opens at zero time and closes after 300 µs.

Figure 14.

Results of the gas dynamic simulations of the time profile of the averaged nitrogen target thickness. The gas valve opens at zero time and closes after 300 µs.

Figure 15.

Results of gas dynamic simulations of the pulsed nitrogen target thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for stagnation pressures 10 bar and 20 bar. Time after the pulsed valve opening is 200 µs. The nozzle length L = 40 mm, exit diameter D = 8mm.

Figure 15.

Results of gas dynamic simulations of the pulsed nitrogen target thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for stagnation pressures 10 bar and 20 bar. Time after the pulsed valve opening is 200 µs. The nozzle length L = 40 mm, exit diameter D = 8mm.

Figure 16.

Results of gas dynamic simulations of the pulsed helium target thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for stagnation pressures 25 bar, 50 bar and 75 bar. Time after the pulsed valve opening is 100 µs. The nozzle length L = 40 mm, exit diameter D = 8mm.

Figure 16.

Results of gas dynamic simulations of the pulsed helium target thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for stagnation pressures 25 bar, 50 bar and 75 bar. Time after the pulsed valve opening is 100 µs. The nozzle length L = 40 mm, exit diameter D = 8mm.

Figure 17.

Results of gas dynamic simulations of the pulsed hydrogen target thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for stagnation pressures 25 bar, 50 bar and 75 bar. Time after the pulsed valve opening is 100 µs. The nozzle length L = 40 mm, exit diameter D = 8mm.

Figure 17.

Results of gas dynamic simulations of the pulsed hydrogen target thickness as a function of distance from the nozzle exit for stagnation pressures 25 bar, 50 bar and 75 bar. Time after the pulsed valve opening is 100 µs. The nozzle length L = 40 mm, exit diameter D = 8mm.

Table 2.

Helium gas catcher efficiency in [%] for different nozzle lengths (L) and outlet diameters (R). The stagnation pressure P0 = 25 bar and the nozzle temperature T0 = 296 K for all calculation variants. Time after the valve opening is 100 µs.

Table 2.

Helium gas catcher efficiency in [%] for different nozzle lengths (L) and outlet diameters (R). The stagnation pressure P0 = 25 bar and the nozzle temperature T0 = 296 K for all calculation variants. Time after the valve opening is 100 µs.

| L (mm) |

20 |

30 |

40 |

50 |

| D (mm) |

| 4 |

94.7 |

93.9 |

92.7 |

91.4 |

| 6 |

97.5 |

96.8 |

96.4 |

95.8 |

| 8 |

97.8 |

97.6 |

97.9 |

97.0 |

| 10 |

97.6 |

97.6 |

97.9 |

97.2 |

Table 3.

Helium target thickness in [µg/cm2] averaged over the gap between the nozzle exit and the catcher tube entrance for different nozzle lengths (L) and outlet diameters (R). The stagnation pressure P0 = 25 bar and the nozzle temperature T0 = 296 K for all calculation variants. Time after the valve opening is 100 µs.

Table 3.

Helium target thickness in [µg/cm2] averaged over the gap between the nozzle exit and the catcher tube entrance for different nozzle lengths (L) and outlet diameters (R). The stagnation pressure P0 = 25 bar and the nozzle temperature T0 = 296 K for all calculation variants. Time after the valve opening is 100 µs.

| L (mm) |

20 |

30 |

40 |

50 |

| D (mm) |

| 4 |

21.61 |

21.94 |

21.25 |

21.76 |

| 6 |

17.70 |

18.57 |

19.61 |

20.04 |

| 8 |

13.68 |

15.09 |

16.37 |

11,19 |

| 10 |

9.90 |

12.04 |

13.44 |

13.86 |

Table 4.

Hydrogen gas catcher efficiency in [%] for different nozzle lengths (L) and outlet diameters (R). The stagnation pressure P0 = 25 bar and the nozzle temperature T0 = 296 K for all calculation variants. Time after the pulsed valve opening is 100 µs.

Table 4.

Hydrogen gas catcher efficiency in [%] for different nozzle lengths (L) and outlet diameters (R). The stagnation pressure P0 = 25 bar and the nozzle temperature T0 = 296 K for all calculation variants. Time after the pulsed valve opening is 100 µs.

| L (mm) |

20 |

30 |

40 |

50 |

| D (mm) |

| 4 |

85.5 |

85.7 |

94.9 |

83.5 |

| 6 |

91.9 |

90.7 |

89.1 |

89.2 |

| 8 |

95.8 |

94.2 |

93.4 |

92.5 |

| 10 |

96.5 |

96.6 |

95.2 |

94.3 |

Table 5.

Hydrogen target thickness in [µg/cm2], averaged over the gap between the nozzle exit and the catcher tube entrance, for different nozzle lengths (L) and outlet diameters (R). The stagnation pressure P0 = 25 bar and the nozzle temperature T0 = 296 K for all calculation variants. Time after the pulsed valve opening is 100 µs.

Table 5.

Hydrogen target thickness in [µg/cm2], averaged over the gap between the nozzle exit and the catcher tube entrance, for different nozzle lengths (L) and outlet diameters (R). The stagnation pressure P0 = 25 bar and the nozzle temperature T0 = 296 K for all calculation variants. Time after the pulsed valve opening is 100 µs.

| L (mm) |

20 |

30 |

40 |

50 |

| D (mm) |

| 4 |

10.20 |

10.18 |

21.81 |

10.03 |

| 6 |

8.69 |

9.33 |

9.52 |

9.68 |

| 8 |

6.48 |

7.63 |

8.05 |

8.41 |

| 10 |

5.62 |

6.06 |

6.59 |

7.03 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).