3. Results and analysis

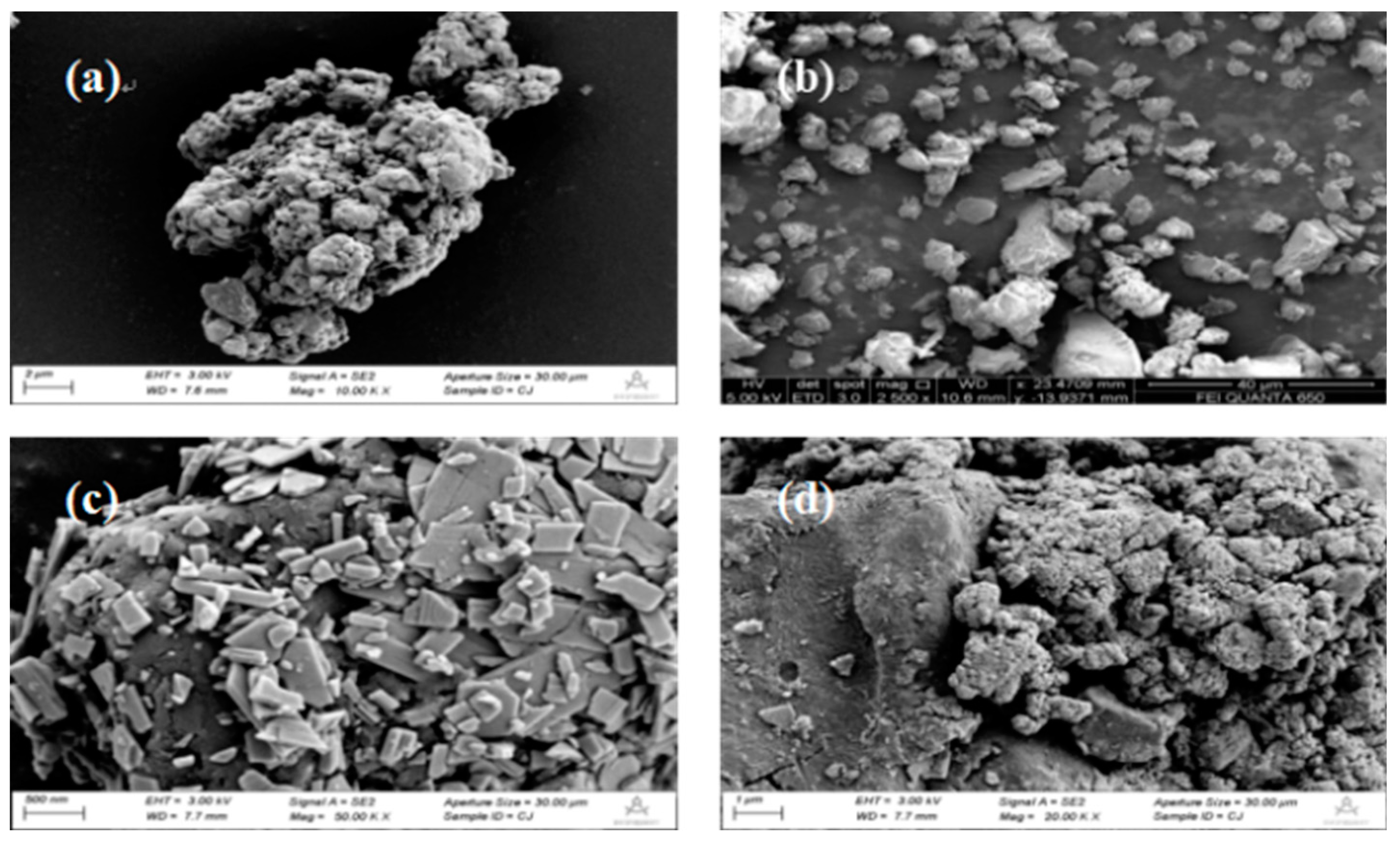

Morphology has an important impact on the specific surface area and surface defects of the material, and has an impact on the photocatalytic performance or adsorption performance of the material. Therefore, the photocatalytic performance of the material can be better studied by observing the morphology of the sample.

Figure 1(a) and (b) are SEM images of CTF-B and CTF-N. It can be seen from the figure that CTF-B is lumpy and irregular in shape, while CTF-N is an accumulation of particles smaller than CTF-B and has a rough surface. As shown in

Figure 1(c) and 1(d), are SEM images of AgIO

3 and AgIO

3/CTF. Among them, AgIO

3 is in the form of flakes with uneven shape, thickness of about 20-60 nm, and maximum lateral width between 200-800 nm. In addition, it can be seen that AgIO

3 nanosheets are distributed on the surface of CTF-N.

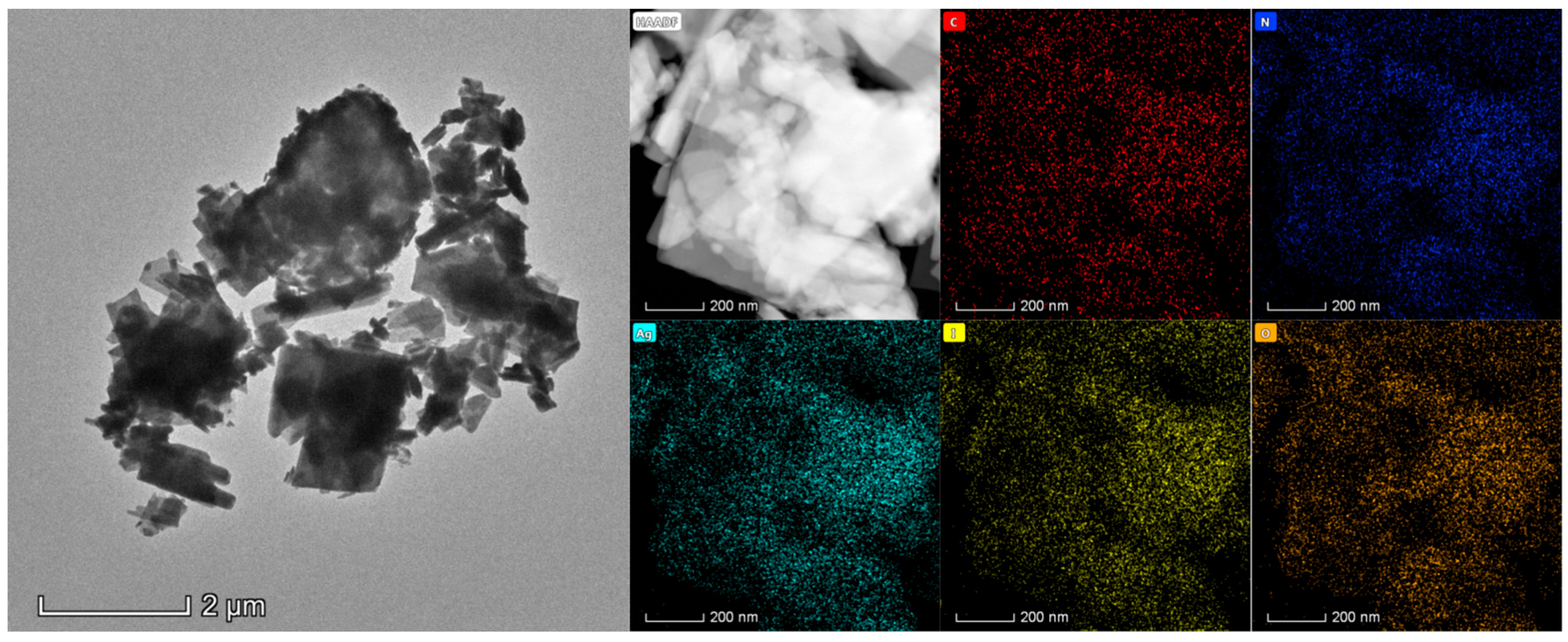

TEM is a more intuitive way to observe the internal structure and spatial distribution of samples.

Figure 2 is the TEM image and elemental scanning results of 0.25AgIO

3/CTF. It can be intuitively seen that AgIO

3 nanosheets are distributed on the surface of an approximately single-layer and highly dispersed CTF-N, with a maximum lateral width between 200-800 nm, which is consistent with the sample appearance shown in the SEM image. In

Figure 2, CTF-N has a translucent structure, indicating that its thickness is very thin; The flaky AgIO

3 and the flaky CTF-N were organically combined to successfully construct the AgIO

3/CTF composite photocatalyst. It can be clearly seen that the constituent elements Ag, I and O of AgIO

3 are evenly distributed on the constituent elements C, O and N of CTF-N. However, because AgIO

3 is highly sensitive to damage caused by electron transmission to internal atoms, we cannot further analyze the microstructure of the composite photocatalyst using a polymer transmission electron microscope.

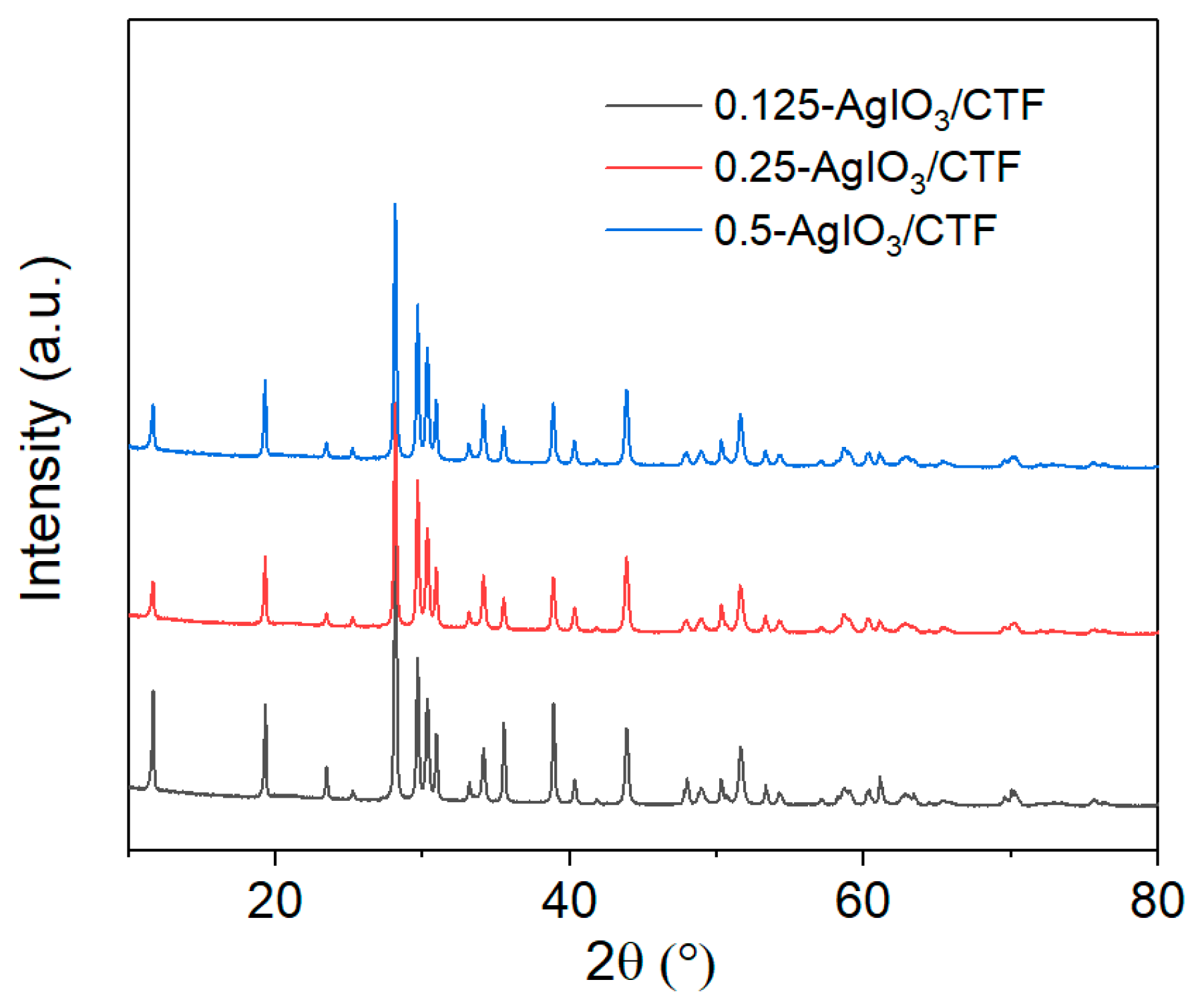

XRD can effectively analyze the phase composition and phase purity of samples. XRD tests were conducted on x-AgIO

3/CTF.

Figure 3 is the XRD pattern of 0.125AgIO

3/CTF, 0.25AgIO

3/CTF and 0.5AgIO

3/CTF. It is observed from

Figure 3 that as the AgIO

3 content in the sample increases, the diffraction peak of AgIO

3 in the sample gradually becomes apparent. The diffraction peak of AgIO

3 in the 0.125AgIO

3/CTF sample is the most obvious, and the diffraction peak of AgIO

3 in 0.25AgIO

3/CTF and 0.5AgIO

3/CTF can also be clearly observed. Therefore, it is believed that AgIO

3 adheres to CTF to form an AgIO

3/CTF composite compound, which further proves the successful synthesis of 0.125AgIO

3/CTF, 0.25AgIO

3/CTF and 0.5AgIO

3/CTF.

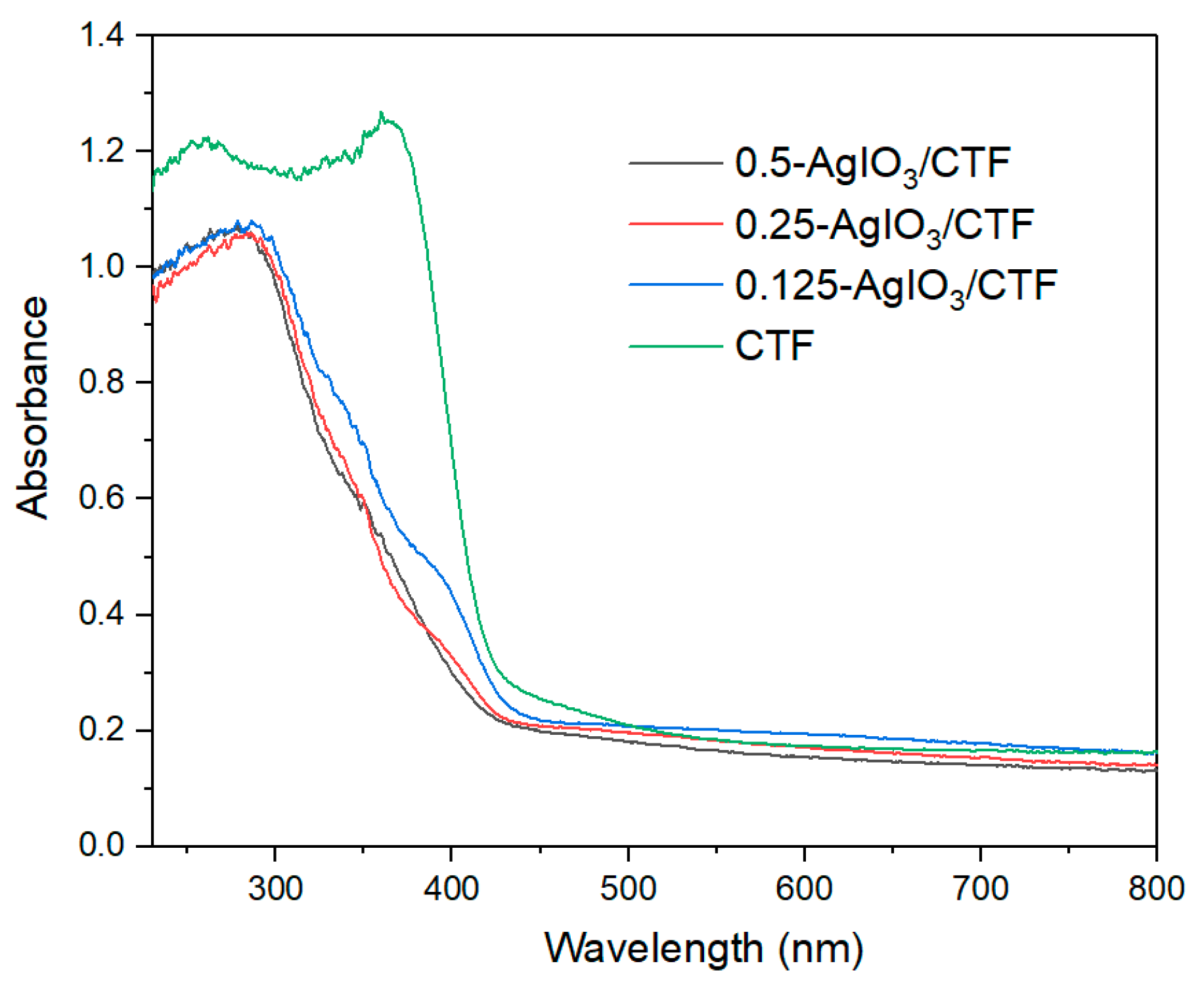

In order to analyze the light absorption capacity and optical band gap of x-AgIO

3/CTF composites, UV-vis tests were conducted.

Figure 4 shows the UV-vis diffuse reflection spectrum of x-AgIO

3/CTF composite material in the wavelength range of 230-800 nm. It can be seen from the figure that x-AgIO

3/CTF absorbs in the range of 230-430 nm and has an obvious AgIO

3 characteristic absorption peak in the 285±5 nm region. The light absorption intensity of this characteristic absorption peak is 1.08. The absorbance of x-AgIO

3/CTF in the 230-800 nm range is higher than that of pure AgIO

3. This is due to the interaction generated by the formation of a heterostructure between AgIO

3 and CTF, which effectively enhances the separation of electron-hole pairs and promotes the band gap transition of photogenerated electrons, thus enhancing the absorption in the visible light region. Theoretically, as the intensity of light absorption by a catalyst increases, the absorbed light energy increases, which increases the rate of generating excited electrons and holes, thereby increasing the photocatalytic efficiency

Error! Reference source not found.. The absorption band edge of x-AgIO

3/CTF is around 430 nm, which is significantly "red-shifted" compared with sample AgIO

3 and shows good optical response capability. This shows that the composite system is conducive to improving the material's utilization of sunlight.

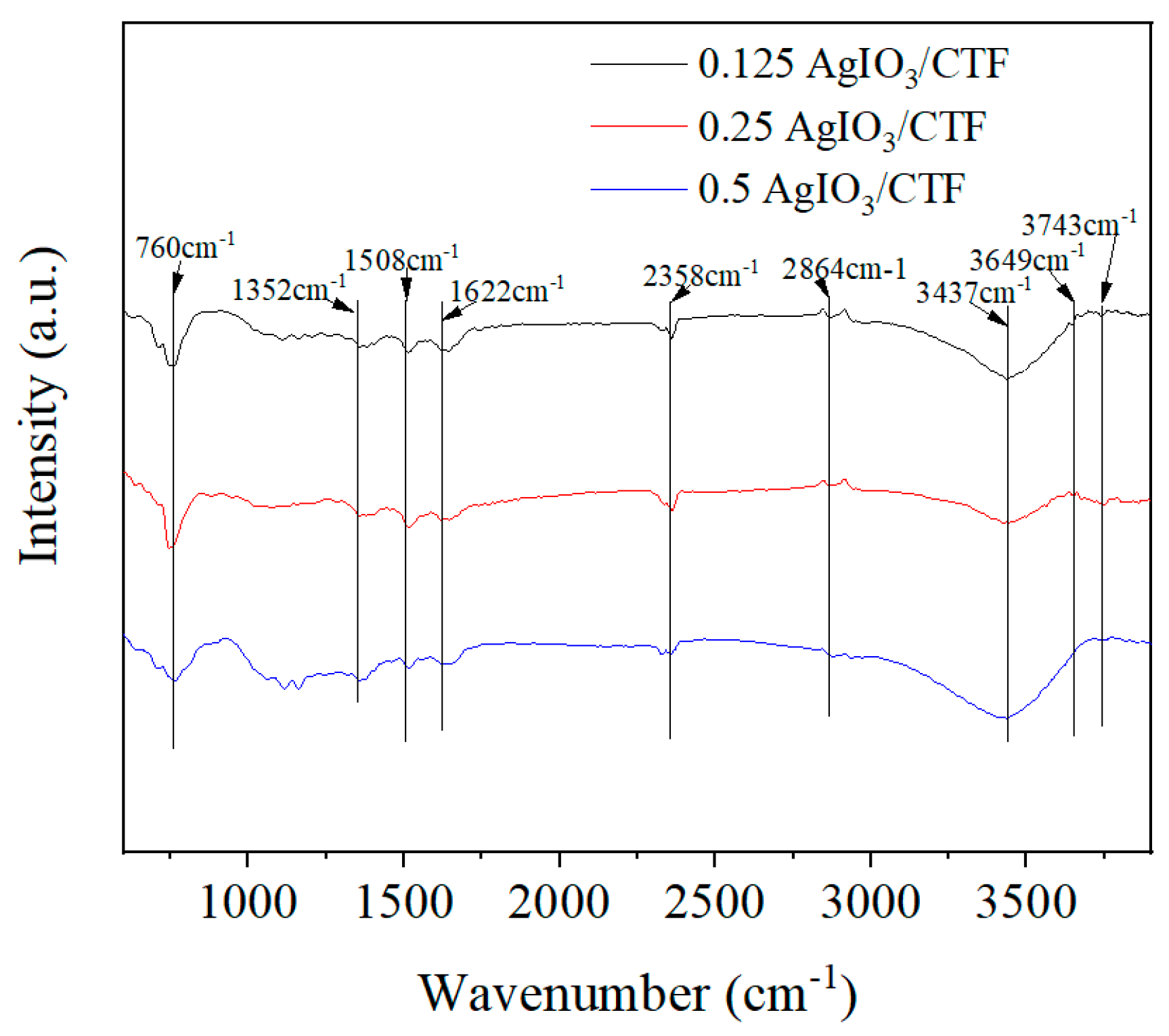

The molecular structure and functional groups of synthetic materials are analyzed by FTIR spectroscopy.

Figure 5 is the FTIR of x-AgIO

3/CTF. Several absorption peaks can be seen from the figure, among which the peak at 760 cm

-1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of the I=O bond. The absorption peak located at 1350-1650 cm

-1 corresponds to the characteristic peak caused by the vibrational stretching of the aromatic C=N bond formed by the triazine ring. The peak located near 2864 cm

-1 corresponds to the symmetric stretching vibration peak of CH

3, and the peaks near 3437 cm

-1, 3649 cm

-1 and 3743 cm

-1 are considered to be the characteristic stretching vibration peaks of hydroxyl groups on the sample surface [

9].

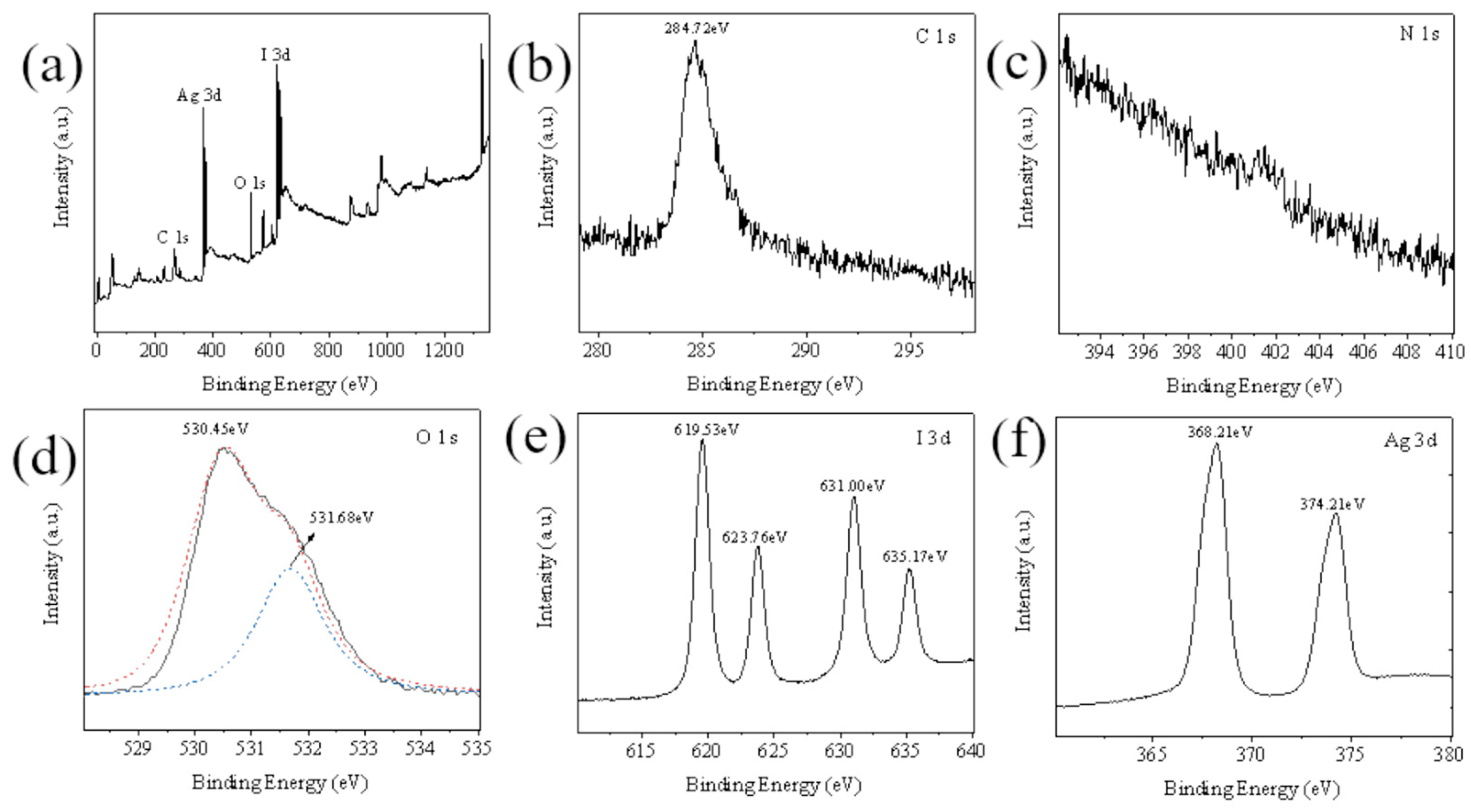

Compare the XPS of 0.25AgIO

3/CTF (

Figure 6a). Obviously, the peaks of C 1s, N 1s, O 1s, I 3d and Ag 3d can be found in their measured spectra. The C element originates from the base of the XPS instrument, and no other peaks are observed, indicating that the prepared sample is of high purity. The peaks at 619.31 eV and 630.79 eV (

Figure 6b) can be attributed to the I 3d5/2 orbital and I 3d3/2 orbital, respectively, which are the characteristic peaks of I

5+ in AgIO

3. The peak at 531.37 eV (

Figure 6c) corresponds to the O 1s orbital. The peaks at 368.11 eV and 374.1 eV (

Figure 6d) can be assigned to the Ag 3d5/2 orbital and Ag 3d3/2 orbital respectively. These results can further prove that the chemical composition of 0.25AgIO

3/CTF remains unchanged after being used for degradation. The 0.25AgIO

3/CTF sample contains Ag, I, N, C and O elements, and the valence state of each element is consistent with the valence state of each element in 0.25AgIO

3/CTF. This once again proved the successful preparation of the 0.25AgIO

3/CTF sample [

10].

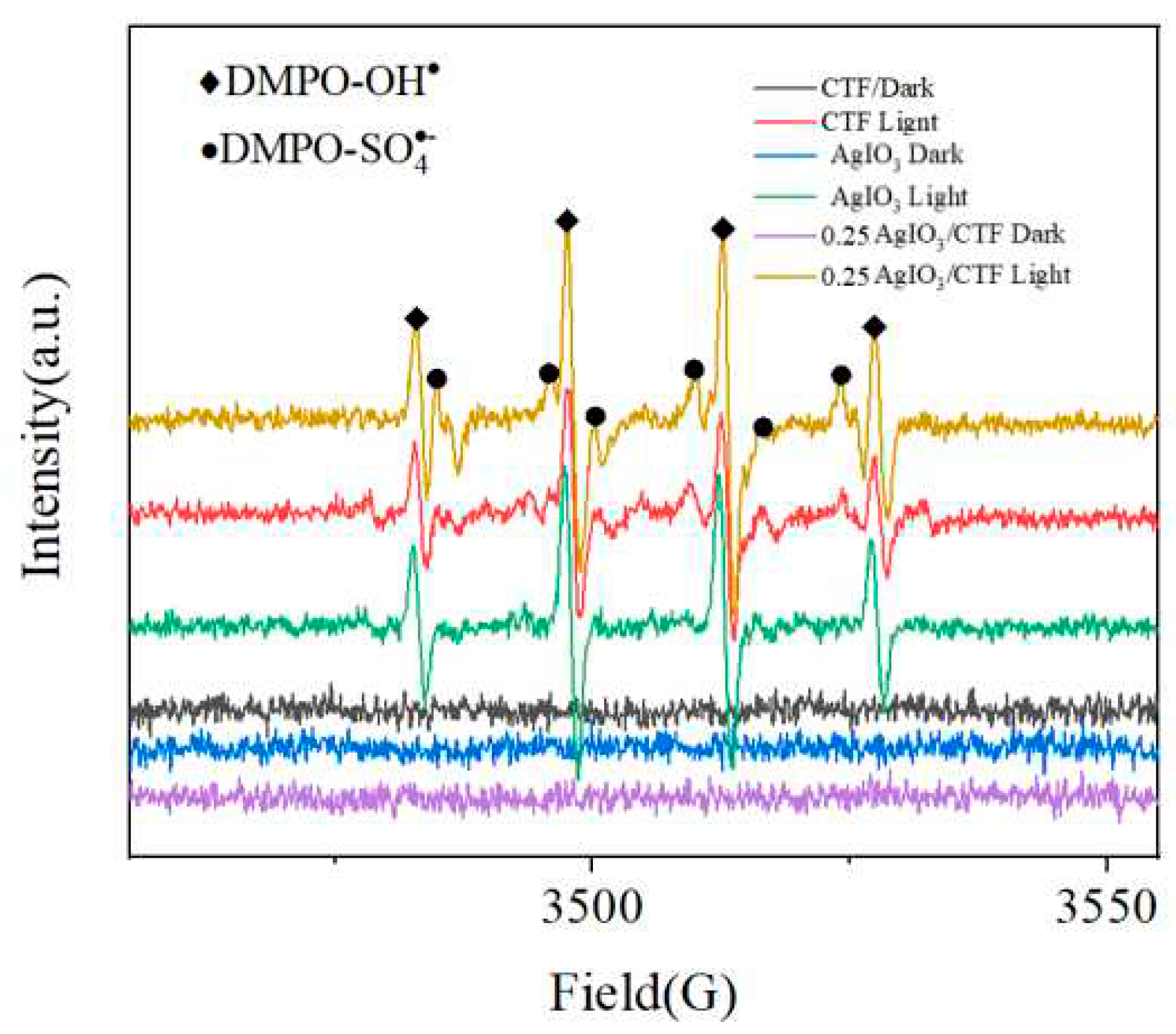

As shown in

Figure 7, the EPR spectra of CTF, AgIO

3 and 0.25AgIO

3/CTF samples under light conditions and dark conditions. It can be seen that there are four strong symmetry signals, and the existence of g value proves that there are vacancies formed by unpaired electrons on the aromatic ring. Under dark conditions, compared with AgIO

3, the EPR curve intensity of 0.25AgIO

3/CTF is stronger. This shows that there are more unpaired electrons in the 0.25AgIO

3/CTF sample, and it also indicates that the sample has a defect structure, which is conducive to the migration of photogenerated carriers. When CTF, AgIO

3 and 0.25AgIO

3/CTF were irradiated with visible light, the EPR signal intensity of 0.25AgIO

3/CTF was significantly enhanced. This shows that the 0.25AgIO

3/CTF photocatalyst will generate more carriers under effective illumination conditions. The entire icon also reflects the characteristic quartet signal of DMPO-OH and the characteristic peak signal of DMPO-SO

42- [

11]. This indicates that -OH and SO

42- are the main reactive oxygen species during the photocatalytic degradation process. In summary, the EPR test results prove that 0.25AgIO

3/CTF will produce SO

42-, H

+ and ·OH active substances during the degradation reaction and are related to the degradation process of pollutants.

In order to further clarify the active substances involved in the photocatalytic process, free radical capture experiments were performed. In this experiment, disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA-2Na), methanol (MeOH), p-benzoquinone (PBQ), and histidine (His) were used as photogenerated holes (h

+) and hydroxyl radicals (·OH). And scavengers such as sulfate radicals (·SO

42-), superoxide radicals (·O

2-) and singlet oxygen (1O

2). The experimental results are shown in the

Figure 8. During the degradation of carbamazepine by 0.25AgIO

3/CTF, the degradation rate did not change significantly after adding PBQ. This indicates that ·O

2- is not the main active species in the degradation of carbamazepine by this catalyst. After 180 min of illumination, the degradation rates of carbamazepine were 17.72% (EDTA-2Na), 22.80% (His), and 46.62% (MeOH) respectively. The results show that in the entire carbamazepine photocatalytic degradation system, ·OH and ·SO

42- are the main active groups, and 1O

2 and H

+ play a smaller role.

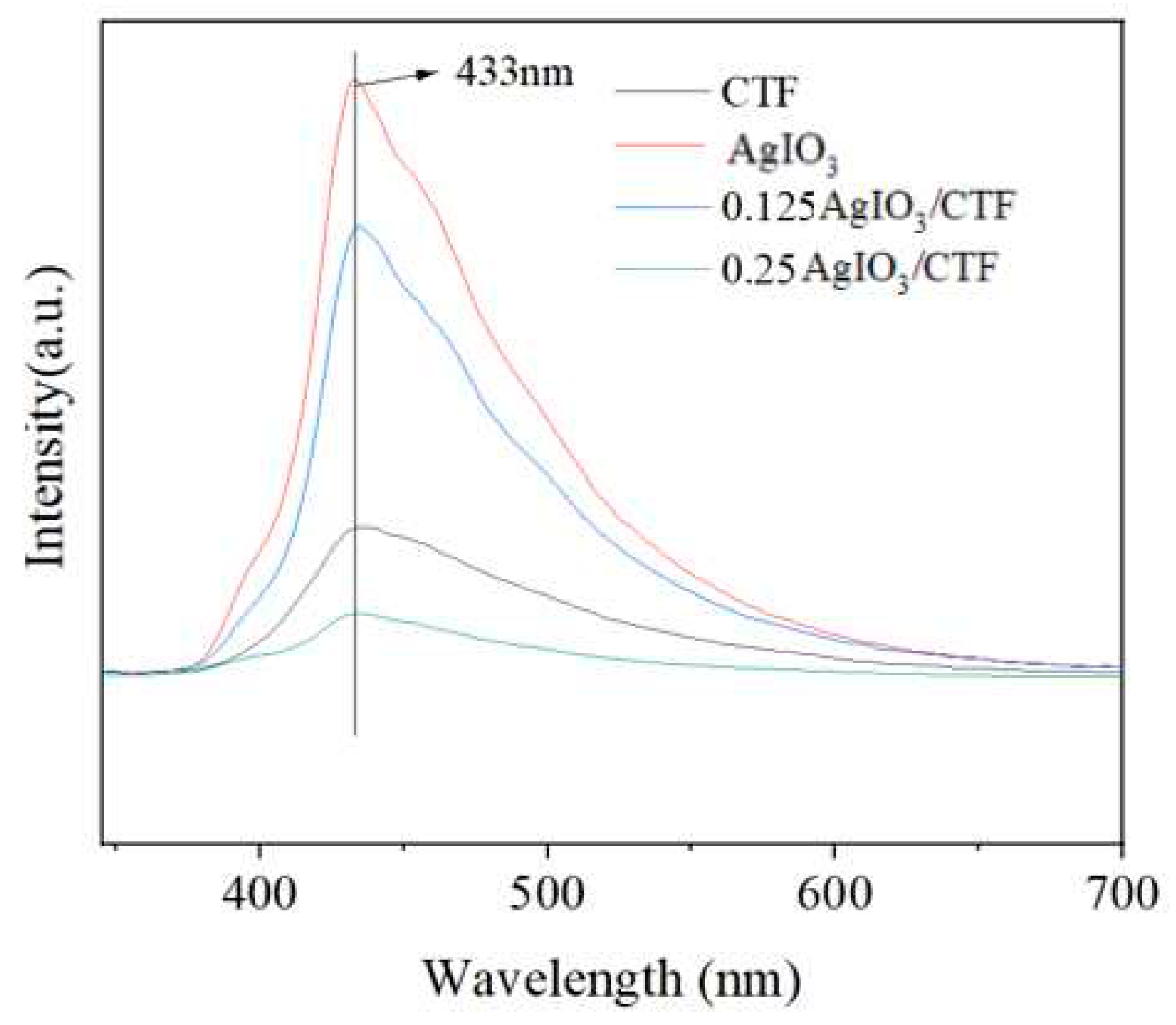

Under light conditions, the steady-state photoluminescence spectra of 0.25AgIO

3/CTF and 0.125AgIO

3/CTF, AgIO

3, and CTF were further analyzed through fluorescence quenching and fluorescence lifetime experiments, as shown in

Figure 9. At 433 nm, when CTF is complexed with AgIO

3, AgIO

3 has a strong emission peak at 433 nm. When CTF forms a heterojunction with AgIO

3, photoinduced charges can be effectively separated. The order of luminescence intensity is AgIO

3>0.125AgIO

3/CTF>CTF>0.25AgIO

3/CTF, which is consistent with the above observed results of photocatalytic activity. The combination of AgIO

3 and CTF can reduce the emission peak, but the compound ratio of AgIO

3 and CTF still needs to be explored [

1,

11,

12].

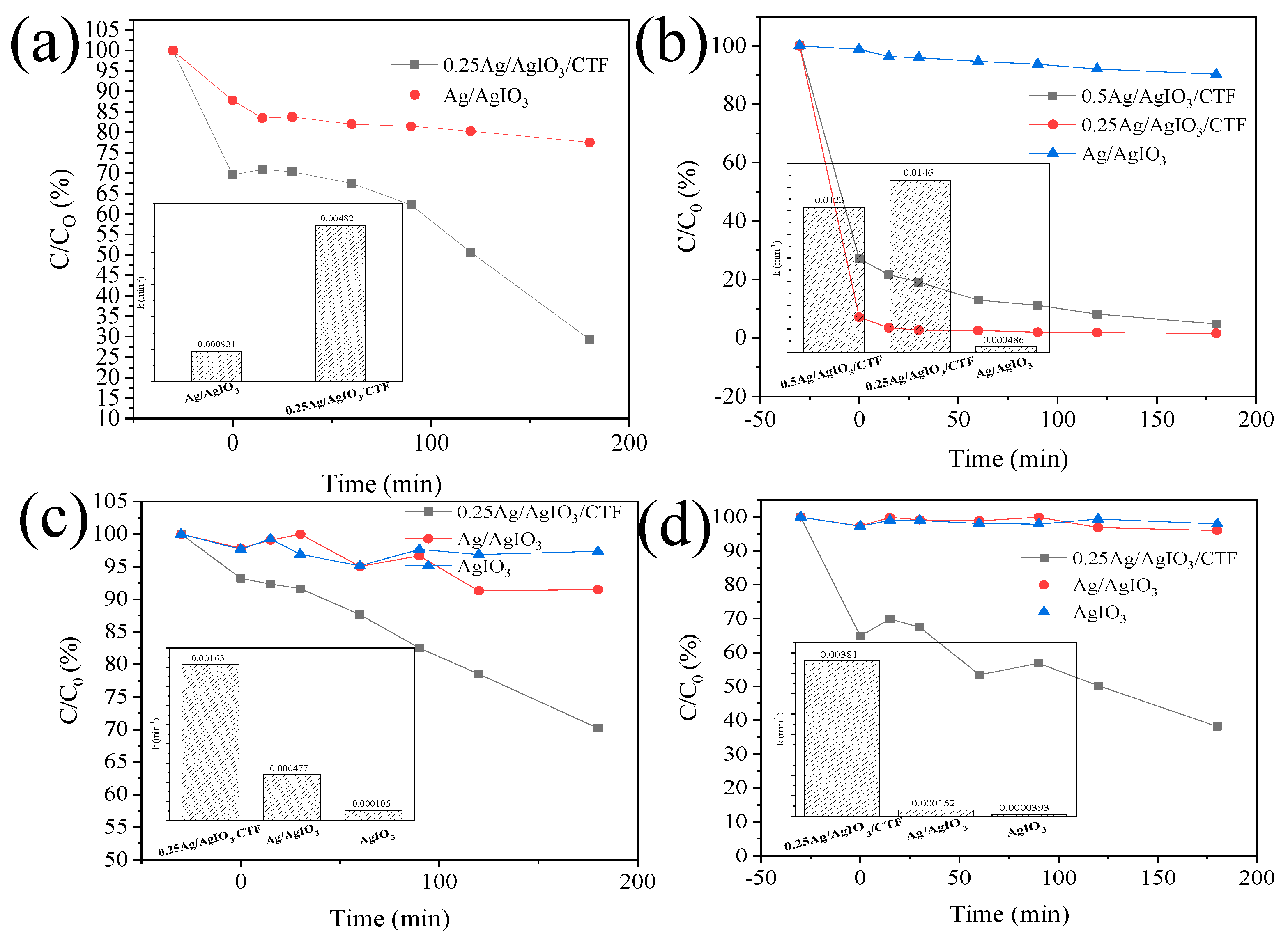

Degradation diagram of different composite catalysts for simulated pollutants paracetamol solution, carbamazepine solution, phenol solution, and p-chlorophenol solution (

Figure 10). It can be seen from the figure that these Ag element composite catalysts have varying degrees of degradation effects on the simulated polluted solution. As time goes by, the content of contaminants in the solution gradually decreases. Now, by calculating the degradation rates of the two catalysts for the two polluted solutions, the degradation rates of AgIO

3 for paracetamol solution, carbamazepine solution, phenol solution, and p-chlorophenol solution are 22.45%, 9.76%, 8.52%, and 3.96% respectively. The degradation rates of pure AgIO

3 to phenol solution and p-chlorophenol solution are 2.63% and 2.02% respectively. The degradation rates of 0.25AgIO

3/CTF for paracetamol solution, carbamazepine solution, phenol solution, and p-chlorophenol solution are 70.69%, 98.45%, 29.78%, and 61.85% respectively. The degradation rate of carbamazepine solution with 0.5AgIO

3/CTF is 95.24%. The photocatalytic degradation performance of the x-AgIO

3/CTF composite material on the target contaminated solution is significantly higher than that of pure AgIO

3. This shows that the lamellar structure of CTF plays a good dispersion role in nano-spherical AgIO

3 and increases the reactive sites. The formation of the heterostructure of the x-AgIO

3/CTF composite material reduces the recombination rate of photogenerated electrons and holes and greatly improves the photocatalytic activity. At the same time, according to the pseudo-first-order kinetic equation, the reaction rate constants of the photocatalytic degradation of different pollutants by different samples were calculated. Among them, the reaction rate constants of 0.25AgIO

3/CTF for the degradation of phenol, p-chlorophenol, carbamazepine and paracetamol are 0.00163, 0.00381, 0.0146 and 0.00482 respectively. The reaction rate constant of 0.25AgIO

3/CTF is 3.41 times, 25.07 times, 30.04 times and 5.18 times that of the single catalyst AgIO

3 reaction rate constants of 0.000477, 0.000152, 0.000486 and 0.000931. This shows that the x-AgIO

3/CTF composite photocatalyst. It has good degradation effect on most pollutants under visible light irradiation and has a wide range of applications.

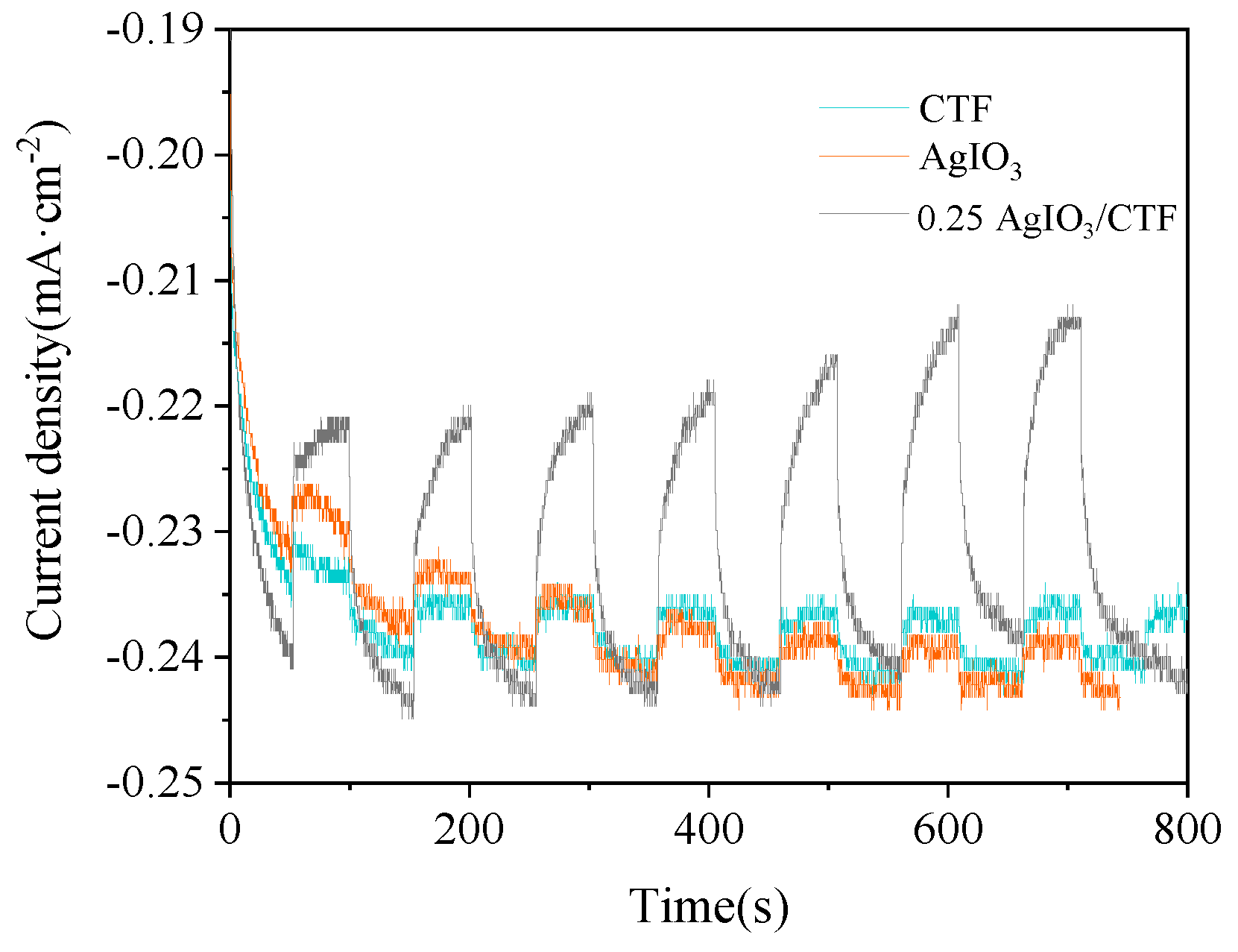

In order to evaluate the transmission efficiency of photocarriers (photoexcited electrons and holes) and the generation of photocurrent in the catalyst, photocurrent tests were conducted on CTF, 0.25AgIO

3/CTF, and AgIO

3. The 0.25AgIO

3/CTF is improved compared to the original CTF.

Figure 11 shows the photocurrent test results of CTF, 0.25AgIO

3/CTF, and AgIO

3. The results show that the photocurrent response intensity of CTF monomer and AgIO

3 monomer is smaller, which shows that the electron-hole separation efficiency of the two is relatively low. The photocurrent response intensity of the 0.25AgIO

3/CTF composite material increased significantly. 0.25AgIO

3/CTF achieved transient photocurrent and further enhanced photocurrent. This finding confirms that the combination of CTF and AgIO

3 can promote the generation and mobility of photoexcited charges under visible light irradiation. In addition, the arc radius of 0.25AgIO

3/CTF in the EIS image is much smaller than that of the CTF catalyst, indicating that the sample has extremely low resistance to charge transfer in the framework, benefiting from the reduction of photoinduced hole separation and photocarrier recombination efficiency [

13].

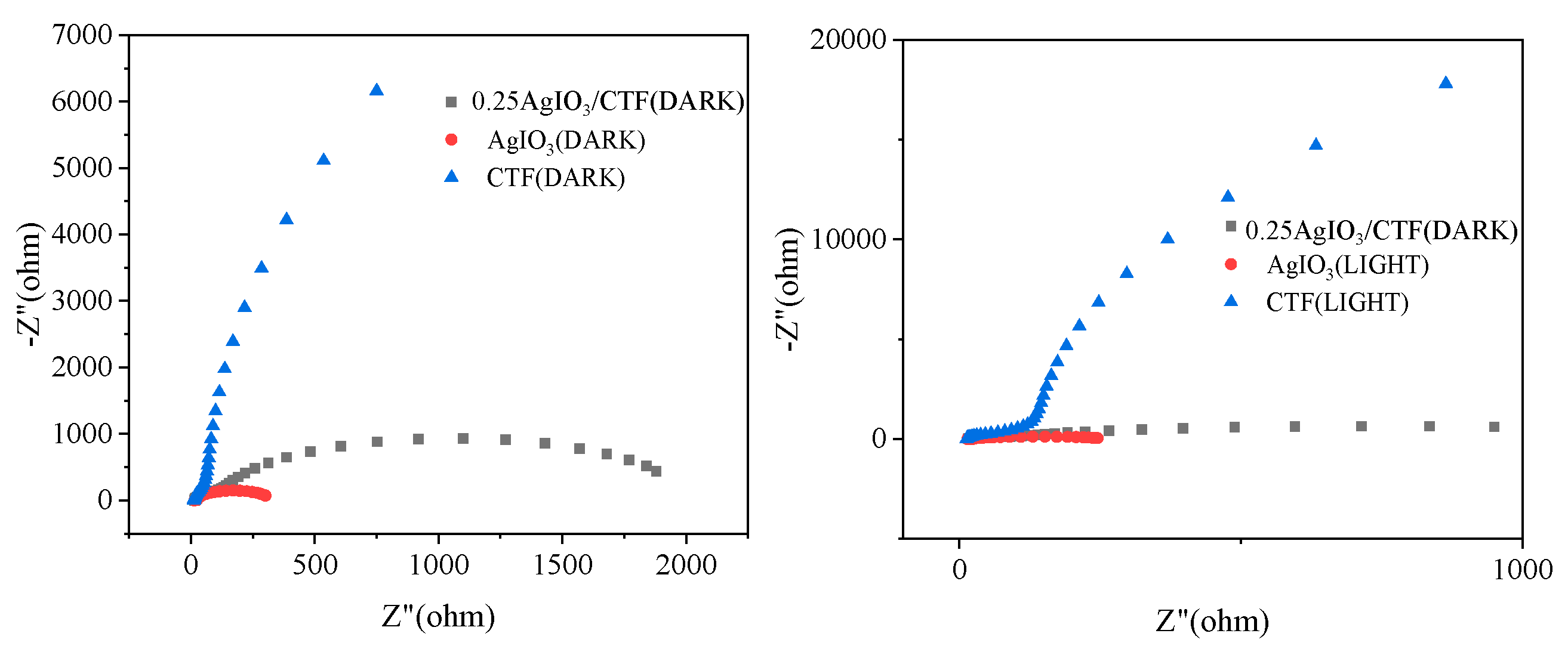

To evaluate the kinetics of charge transfer in this heterostructure composite, EIS tests were performed. The size of the arc radius on the Nynquist curve can reflect the photoreaction rate of the corresponding catalyst on the electrode surface. The smaller the arc diameter, the smaller the hindrance effect [

14]. This shows that the smaller the charge transfer resistance Rct, the stronger the conductive performance of the electrode. A smaller arc radius indicates lower interfacial layer resistance at the electrode surface. It can be seen from

Figure 12 that the photocurrent of the composite photocatalyst film is significantly higher than that of the single catalyst film. This shows that the combination of x-AgIO

3/CTF effectively inhibits the recombination of photogenerated electron and hole pairs of a single catalyst, thereby increasing its photocurrent intensity. This also indicates that its ability to photocatalytically remove pollutants may also be improved. At the same time, 0.25AgIO

3/CTF shows the smallest arc radius compared to AgIO

3 and CTF, which indicates that the charge transfer resistance on the surface of 0.25AgIO

3/CTF is reduced. This therefore results in efficient electron-hole pair separation, which is consistent with the i-t results. The above results confirm that the 0.25AgIO

3/CTF photocatalyst has the highest separation efficiency and migration efficiency during the photocatalytic reaction process, thus giving it better photocatalytic performance.

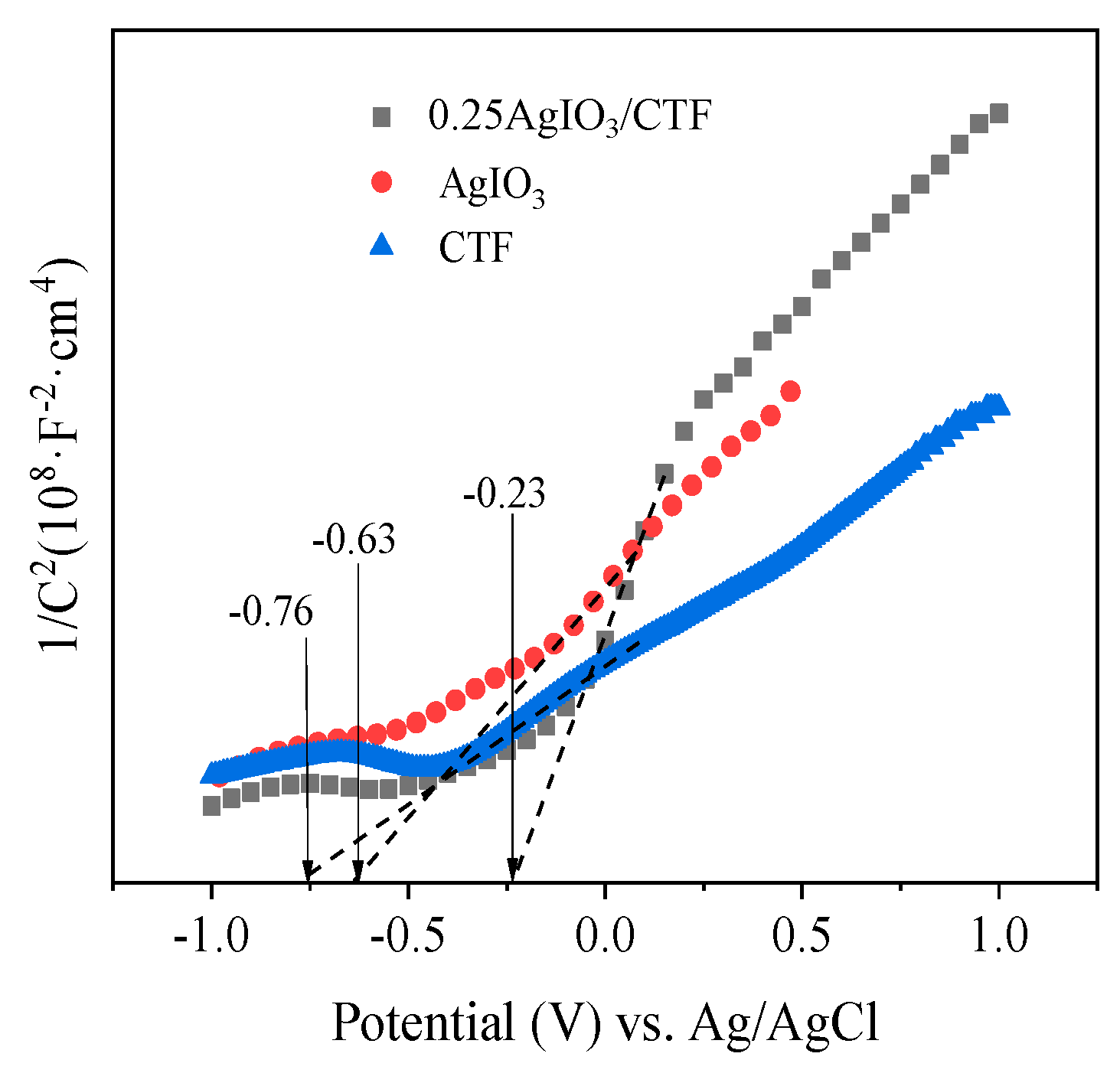

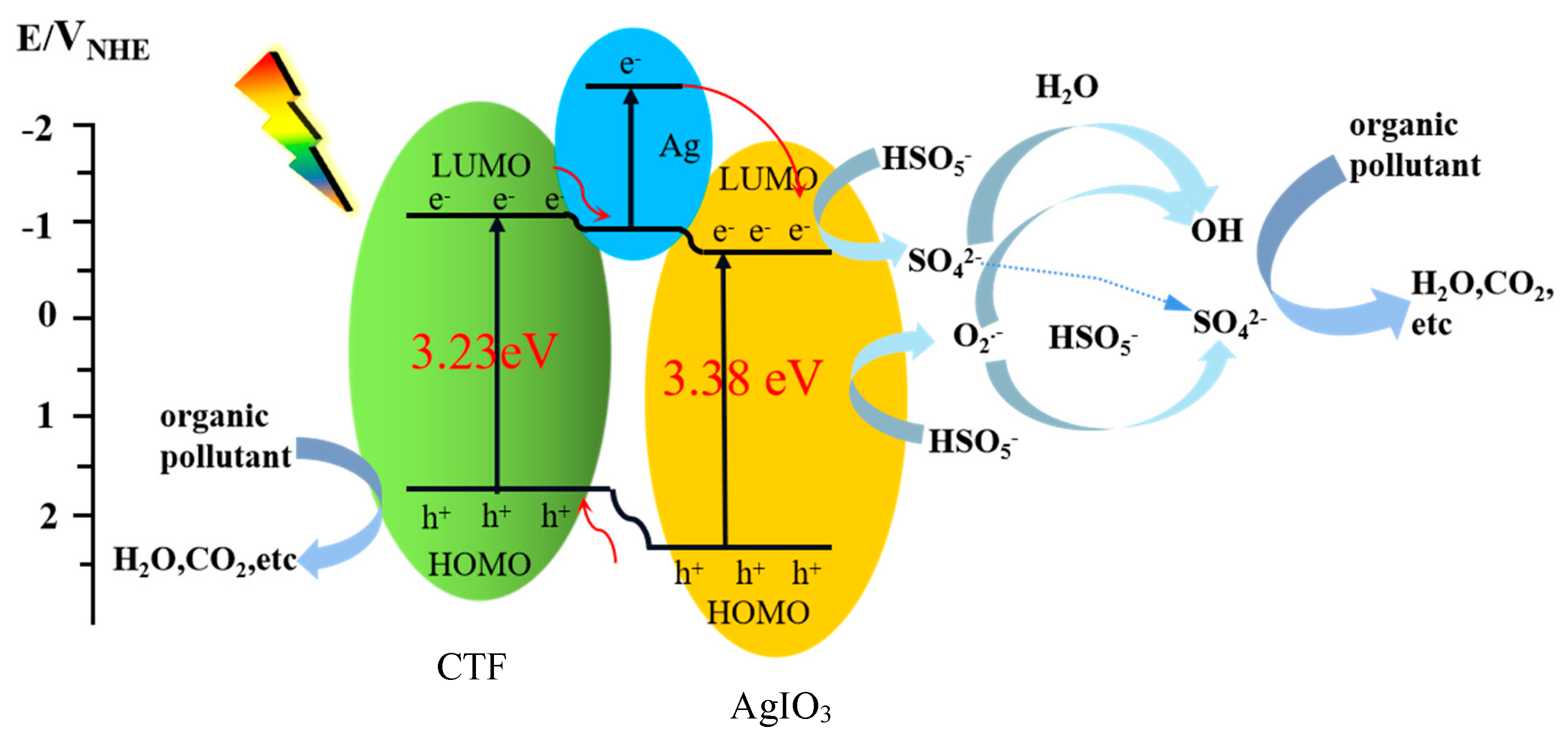

In order to better understand the mechanism of CBZ-accelerated photocatalytic degradation in the 0.25AgIO

3/CTF/vis/PMS system, the energy band structure of 0.25AgIO

3/CTF with respect to the photoinduced carrier redox ability was evaluated. Typical Mott-Schottky plots for various catalysts measured in the dark at a frequency of 100 Hz are shown in

Figure 13. The positive slope of the 1/C

2 values obtained indicates that each catalyst has n-type semiconductor properties. The flat band potentials of CTF, AgIO

3 and 0.25AgIO

3/CTF samples are approximately -0.76, -0.63 and -0.23 V respectively. Based on the relationship between the Ag/AgCl electrode and the normal hydrogen electrode (NHE), it can be calculated that the flat band potentials of each catalyst are -0.56, -0.43 and -0.03 V respectively compared to the normal hydrogen electrode (NHE). It has been reported that the flat band potential of n-type semiconductors is usually 0-0.1 V higher than the conduction band potential [

15]. For organic semiconductor materials, the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) and the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) are equivalent to the conduction band (CB) and valence band (VB) of inorganic semiconductor materials, respectively [

16]. Therefore, combined with the UV-visible diffuse reflectance spectrum of the sample, the conduction band and valence band potential of each sample relative to the standard hydrogen electrode potential can be obtained. Because the valence band potential energy of the 0.25AgIO

3/CTF heterojunction photocatalyst is more negative than the redox potential energy of SO

4-/SO

42- (2.5-3.1 V vs NHE) [

17]. Therefore, the photogenerated electrons can be captured by PMS, thereby producing ·SO

4-.

The characteristics of x-AgIO

3/CTF meet the requirements for improving photocatalytic performance. More specifically, x-AgIO

3/CTF increases the band edge to narrow the band gap and expands the visible light absorption boundary [

19]. Due to the existence of elemental Ag, its plasmon resonance effect and good conductivity, it can also generate photogenerated charges and quickly transfer electrons [

18]. The existence of the heterojunction shortens the transmission distance of charges to the surface, thereby enhancing light capture and reducing the recombination probability of photoexcited carriers. As shown in

Scheme 1, under the irradiation of visible light, after electrons are excited, holes will be left in the valence band, but photogenerated electrons and holes are easy to recombine [

19]. Due to the formation of a p-n heterojunction structure between CTF and AgIO

3, the valence band energy level of AgIO

3 is higher than that of CTF. Holes will easily transfer to the CTF, thus inhibiting the recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs inside AgIO

3 [

20,

21,

22]. At the same time, due to the existence of elemental Ag, its plasmon resonance effect and good conductivity, it can also generate photogenerated charges and quickly transfer electrons [

23]. Taking advantage of the difference in energy level positions between CTF and AgIO

3 and the presence of elemental Ag, the recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs inside the composite material is ultimately effectively suppressed and the photocatalytic activity of the composite material is improved. Under this condition, holes (h

+) react with HO

- in water to produce hydroxyl radicals (·OH), and electrons react with dissolved oxygen (O

2) in water to produce superoxide radicals (·O

2-). After the introduction of PMS, the separation of carriers is further accelerated due to the rapid capture of photogenerated electrons. PMS itself decomposes into various reactive substances through a series of chain reactions, and photooxidation (mainly h

+) and PMS chemical activation (mainly ·OH and ·SO

4-) are introduced to collaboratively remove organic pollutants. Because PMS (1.82 V vs NHE) is much greater than the oxidizing property of oxygen (1.23 V vs NHE). The e

- on the conduction band is thermodynamically more likely to be captured by PMS, and then activated to generate free radicals (HSO

5-+e

-→·SO

4-+OH

-;·SO

4-+H

2O→·OH+SO

42-+H

+). Since the redox potential of O

2− (0.91 V) is much lower than that of ·OH (1.9-2.7 V) and ·SO

4- (2.5-3.1 V), it may be less reactive with organic contaminants in aqueous solutions [

24,

25]. Therefore, using ·O

2− as an intermediate, other reaction species ·OH (HSO

5-+·O

2−→·OH+SO

42-+O

2), SO

4- (HSO

5-+·O

2-→OH-+SO

42-+O

2), and 1O

2 (2·O

2-+2H

2O→1O

2+ H

2O

2+2OH

-) are formed. These free radicals react with organic pollutants pre-adsorbed on the catalyst surface, causing the organic pollutants to be redox-degraded into inorganic small molecules (H

2O, CO

2, etc.) [

26,

27].