Submitted:

06 December 2023

Posted:

06 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Human Specimens

2.3. Animals

2.4. Brain AVM Model Induction and Viral Vector Delivery in Mice

2.5. Administration of CSF1R Inhibitor (PLX5622)

2.6. Immunofluorescence Staining of Human and Mouse Sections

2.7. Prussian Blue Staining

2.8. RNA-Seq Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Human Ruptured bAVMs Have Higher COL I and COL III Levels and COL I/ COL III Ratio than Unruptured bAVMs

3.2. Mouse bAVMs Have Higher Col I/Col III Ratio Which Are Associated with Microhemorrhage

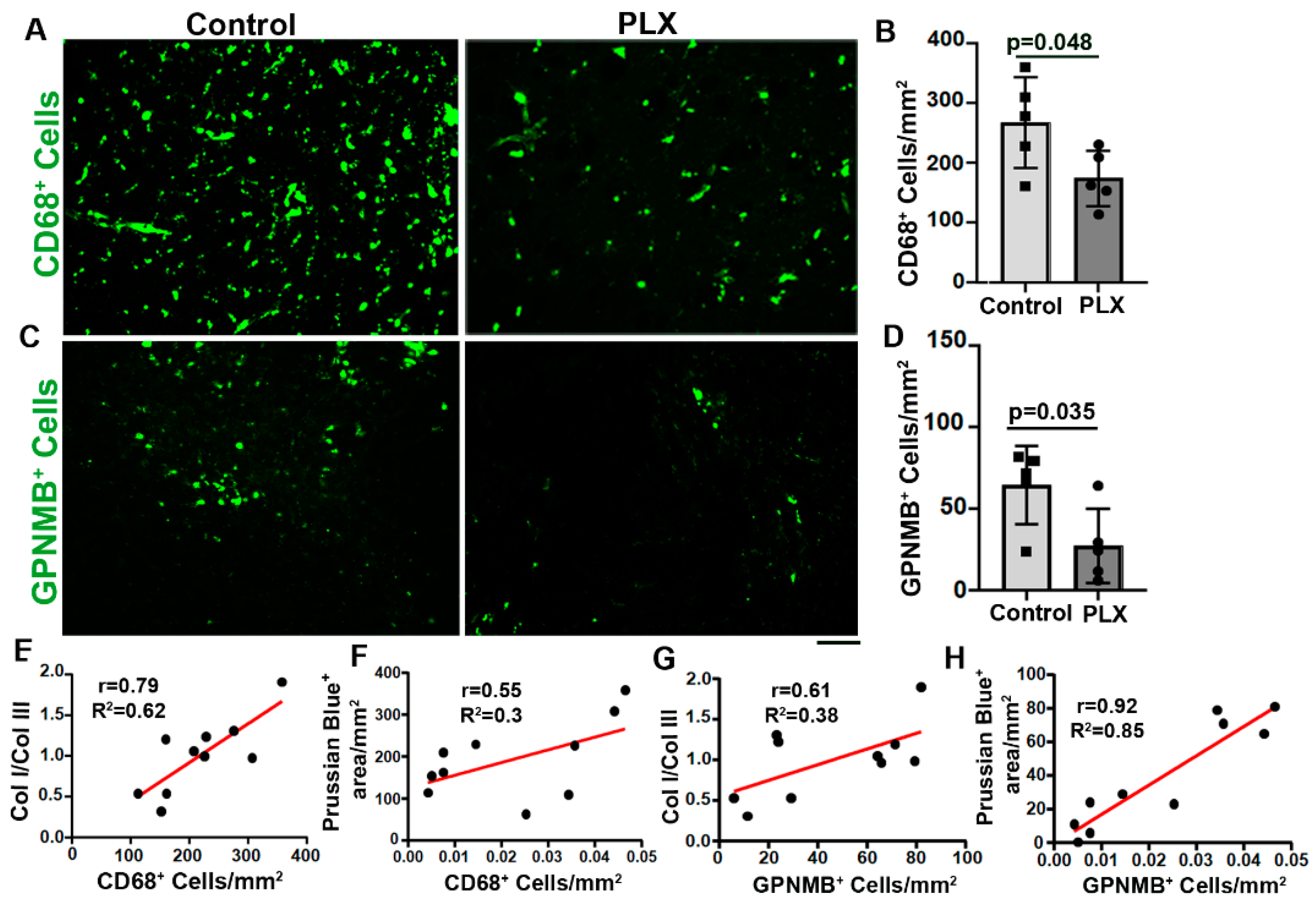

3.3. Transient Depletion of Central Nervous System (CNS) Macrophages/Microglia Reduced Col I/Col III Ratios and Microhemorrhage in bAVM

3.4. Fibroblast and Inflammatory-Related Genes Are Upregulated in Mouse bAVMs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Klebe, D., et al., Intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. Trauma. Ischemic Inj. Methods Protoc. 2018, 2018, 83–91.

- Yi, G. , et al., Human brain arteriovenous malformations are associated with interruptions in elastic fibers and changes in collagen content. Turk. Neurosurg. 2013, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. , et al., CT Angiography Radiomics Combining Traditional Risk Factors to Predict Brain Arteriovenous Malformation Rupture: a Machine Learning, Multicenter Study. Transl. Stroke Res. 2023, 2023, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, Z. , et al., Modulatory properties of extracellular matrix glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans on neural stem cells behavior: Highlights on regenerative potential and bioactivity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 171, 366–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchand, M., et al. Extracellular matrix scaffolding in angiogenesis and capillary homeostasis. in Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2019. Elsevier.

- Ma, Z. , et al., Extracellular matrix dynamics in vascular remodeling. Am. J. Physiol. -Cell Physiol. 2020, 319, C481–C499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, H. , et al., Relationships between hemorrhage, angioarchitectural factors and collagen of arteriovenous malformations. Neurosci. Bull. 2012, 28, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyazi, B. , et al., Brain arteriovenous malformations: implications of CEACAM1-positive inflammatory cells and sex on hemorrhage. Neurosurg. Rev. 2017, 40, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, J. , et al., Medical management with or without interventional therapy for unruptured brain arteriovenous malformations (ARUBA): a multicentre, non-blinded, randomised trial. Lancet 2014, 383, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, E.A. , et al., A single-cell atlas of the normal and malformed human brain vasculature. Science 2022, 375, eabi7377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.-Q. , et al., Essential involvement of IL-6 in the skin wound-healing process as evidenced by delayed wound healing in IL-6-deficient mice. J. Leucoc. Biol. 2003, 73, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzadehpanah, H.; Modaghegh, M.H.S.; Mahaki, H. Key biomarkers in cerebral arteriovenous malformations: Updated review. J. Gene Med. 2023, 25, e3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagenhäuser, M. , et al., Crosstalk of platelets with macrophages and fibroblasts aggravates inflammation, aortic wall stiffening and osteopontin release in abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 2023, cvad168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allinson, K.R. , et al., Generation of a floxed allele of the mouse Endoglin gene. Genesis 2007, 45, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, M.C. , et al., Discoidin domain receptor 1 mediates collagen-induced inflammatory activation of microglia in culture. J. Neurosci. Res. 2008, 86, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G. , et al., A large, single-center, real-world study of clinicopathological characteristics and treatment in advanced ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Med. 2017, 6, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaligram, S. , et al., Abstract TMP5: Bone Marrow-derived And Clonally Expanded Alk1-Endothelial Cells Contribute To Brain Arteriovenous Malformation In Mice. Stroke 2022, 53 (Suppl. S1), ATMP5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.-J. , et al., Novel brain arteriovenous malformation mouse models for type 1 hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, E.J. , et al., Arteriovenous malformation in the adult mouse brain resembling the human disease. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 69, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Rai, V.; Agrawal, D.K. Regulation of Collagen I and Collagen III in Tissue Injury and Regeneration. Cardiol. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senk, A.; Djonov, V. Collagen fibers provide guidance cues for capillary regrowth during regenerative angiogenesis in zebrafish. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannad, F.; Rossignol, P.; Iraqi, W. Extracellular matrix fibrotic markers in heart failure. Heart Fail. Rev. 2010, 15, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittig, C.; Szulcek, R. Extracellular matrix protein ratios in the human heart and vessels: how to distinguish pathological from physiological changes? Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 708656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasubramanian, P. , et al., Collagen in human tissues: structure, function, and biomedical implications from a tissue engineering perspective. Polym. Compos. Polyolefin Fractionation Polym. Pept. Collagens 2013, 2013, 173–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A. , et al., Vascular fibrosis in aging and hypertension: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Can. J. Cardiol. 2016, 32, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, K. , et al., In situ hybridization reveals that type I and III collagens are produced by pericytes in the anterior pituitary gland of rats. Cell Tissue Res. 2010, 342, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuwabara, J.T.; Tallquist, M.D. Tracking adventitial fibroblast contribution to disease: a review of current methods to identify resident fibroblasts. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 1598–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortensen, J.H. , et al., Fragments of citrullinated and MMP-degraded vimentin and MMP-degraded type III collagen are novel serological biomarkers to differentiate Crohn’s disease from ulcerative colitis. J. Crohn's Colitis 2015, 9, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeming, D.J. , et al., A novel marker for assessment of liver matrix remodeling: an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) detecting a MMP generated type I collagen neo-epitope (C1M). Biomarkers 2011, 16, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo Martins, J.M. , et al., Tumoral and stromal expression of MMP-2, MMP-9, MMP-14, TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and VEGF-A in cervical cancer patient survival: a competing risk analysis. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hajj, E.C. , et al., Extracellular Matrix in Cardiovascular Pathophysiology: Inhibitor of lysyl oxidase improves cardiac function and the collagen/MMP profile in response to volume overload. Am. J. Physiol. -Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 315, H463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overall, C.; Wrana, J.; Sodek, J. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of 72-kDa gelatinase/type IV collagenase by transforming growth factor-beta 1 in human fibroblasts. Comparisons with collagenase and tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 14064–14071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woessner Jr, J.F. , Matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in connective tissue remodeling. FASEB J. 1991, 5, 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.S. , et al., Soluble endoglin stimulates inflammatory and angiogenic responses in microglia that are associated with endothelial dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendok, B.; Awad, I.A. Evidence of inflammatory cell involvement in brain arteriovenous malformations: Commentary. Neurosurgery 2008, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Germans, M.R. , et al., Molecular signature of brain arteriovenous malformation hemorrhage: a systematic review. World Neurosurg. 2022, 157, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R. , et al., Persistent Infiltration of Active Microglia in Brain Arteriovenous Malformation Causes Unresolved Inflammation and Lesion Progression. Stroke 2015, 46 (Suppl. S1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saade, M. , et al., The role of GPNMB in inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 674739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y. , et al., Glycoprotein nonmetastatic melanoma protein B (GPNMB) as a novel neuroprotective factor in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury. Neuroscience 2014, 277, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ripoll, V.M. , et al., Gpnmb is induced in macrophages by IFN-γ and lipopolysaccharide and acts as a feedback regulator of proinflammatory responses. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 6557–6566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D. , et al., Angiogenesis depends upon EPHB4-mediated export of collagen IV from vascular endothelial cells. JCI Insight 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D. , et al., RASA1-dependent cellular export of collagen IV controls blood and lymphatic vascular development. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 3545–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neyazi, B. , et al., Age-dependent changes of collagen alpha-2 (IV) expression in the extracellular matrix of brain arteriovenous malformations. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2020, 189, 105589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pathway Name | Adj. p-Value |

|---|---|

| Angiogenesis | 2.07E-17 |

| Vasculogenesis | 9.6E-05 |

| Collagen binding signaling | 0.0001 |

| Acute inflammatory response | 0.042 |

| Gene name | Adj. p-value |

| CD248* | 1.8E-05 |

| Mpeg1** | 1.7E-05 |

| Icam2** | 0.0003 |

| CD68** | 0.004 |

| Csf1** | 0.002 |

| Timp2 | 0.01 |

| Vim* | 0.019 |

| CD34* | 0.02 |

| Col1a1*** | 0.035 |

| Col3a1*** | 0.032 |

| Csf2rb** | 0.049 |

| Timp2**** | 0.01 |

| Timp3**** | 0.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).