Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

A mathematical model that comprehensively captures the behavior of mobile riverbed deformation encompassing all pertinent effects was developed. The underwater slope reformation process with the generatrix aligned along the flow velocity in the model was considered. A numerical model was introduced to calculate the flow involving a deformable bottom, and the model's validation was established through rigorous analysis of the experimental findings. This research confirms the suitability of the proposed mathematical and numerical model for describing deformations in uneven and unsteady river flows, including the movement of dredging slots and channel quarries. The minimal equation count and reliance on empirical constants demonstrate the efficiency of the model. The model's predictions aligned firmly with the experimental data, although the optimal values of the empirical coefficients varied slightly across different experiments. Hence, there is a call for further investigation to derive more universally applicable closure relationships for the model. The importance of validating the model with reliable field data and its potential extension to accommodate hydraulically diverse soils is emphasized. Such an extension is feasible because of the concentration transfer equation, which enables independent calculations for particle fractions of varying sizes as long as the total particle concentration in the stream remains within reasonable limits. This dedicated research contributes to understanding riverbed deformation, advancing accurate modeling, and managing riverine environments.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The use of a similarity transformation would show that a process on a smaller scale (on a model) is equivalent to a process on a larger scale (in reality).

- finding modeling criteria based on it;

- establishing areas of self-similarity according to various criteria if they exist.

- U and V are the components of the depth-averaged water velocity vector along the x- and y-axes, respectively.

- h (x,y,t) is the flow depth

- S (x,y,t)* is the saturation turbidity, which denotes the vertical average volume concentration of the sediment in an equivalent uniform flow.

- selection of the elementary flow equation;

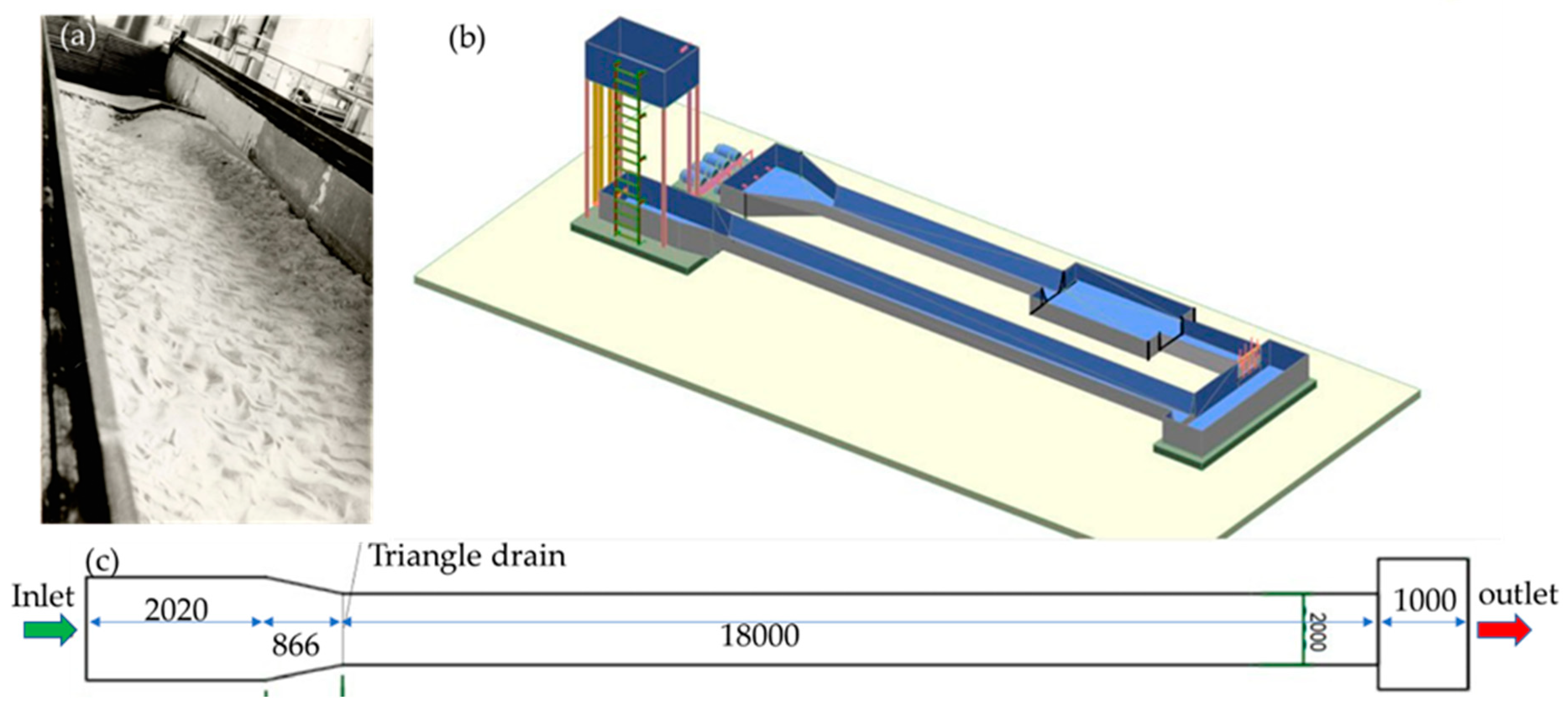

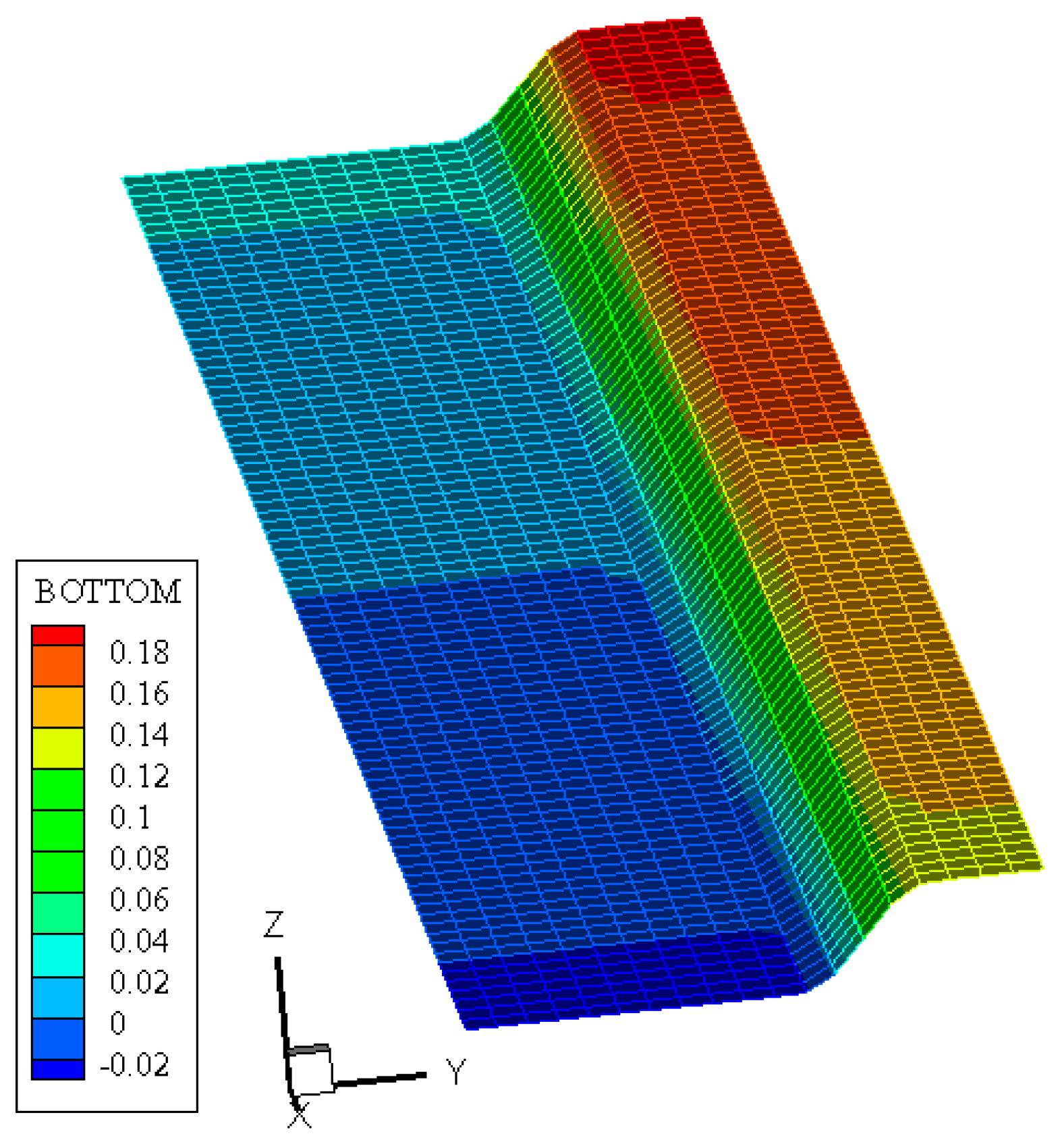

- conducted numerical studies on the reformation of inclined channel walls with a moving bottom.

- conducting experimental studies

- comparison of the obtained results with the results of experimental studies.

2. Methods

2.1. Analytical studies

- Choice of Flow Equation: The selection of the Equation governing flow movement in the riverbed is represented by a system of two-phase hydrodynamic equations of Saint-Venant. These equations were complemented by including equations related to sediment balance, transport, and the Bagnold Equation.

- Numerical and Experimental Studies: Numerical and experimental studies were conducted under the conditions of a moving bottom by utilizing the chosen equations.

- Comparison of Results: The results obtained from both the numerical and experimental studies were thoroughly compared and analyzed.

2.1. Experimental studies

3. Results

3.1. Mathematical model

- is the time; is the flow depth;

- U and V are the components of the flow velocity along the X and Y axis, respectively.

- ;

- is the volumetric concentration of sediment particles in the flow;

- Is the equilibrium volume concentration of particles (saturation concentration) calculated according to the modified Bagnold formula:

- is the intensity coefficient of vertical sediment exchange between the bottom and the stream, is the soil porosity (the ratio of the volume of pores to the volume of the entire soil with pores).

- is the densities of soil and water, respectively;

- φ is the angle of internal friction of the soil.

- is the hydraulic soil coarseness;

- Is the dynamic speed;

- , These are the modules of the average vertical flow velocity and non-shear velocity, respectively.

- is the coefficient of hydraulic friction calculated using the Manning formula, is the roughness coefficient.

- –

- On solid boundaries, the condition of no flow is specified.

- –

- For liquid boundaries, flow rates or water levels are typically specified.

- –

- Water flowed into the computational domain through the boundaries of the computational domain, and the precipitation concentration was set at these boundaries.

- –

- Complex boundary conditions are also occasionally used. Complex boundary conditions can link costs with levels and non-reflective boundary conditions.

3.2. Numerical model

4. Conclusions

- The proposed mathematical model (Section 3.1) and numerical model (Section 3.2) for bottom deformations in uneven and unsteady river flows are suitable for calculating deformable channels, making them applicable to scenarios such as easily eroded beds. The models are characterized by their simplicity, with a minimum number of equations and empirical constants.

- Two-dimensional mathematical and numerical models of a deformable channel were developed and successfully verified.

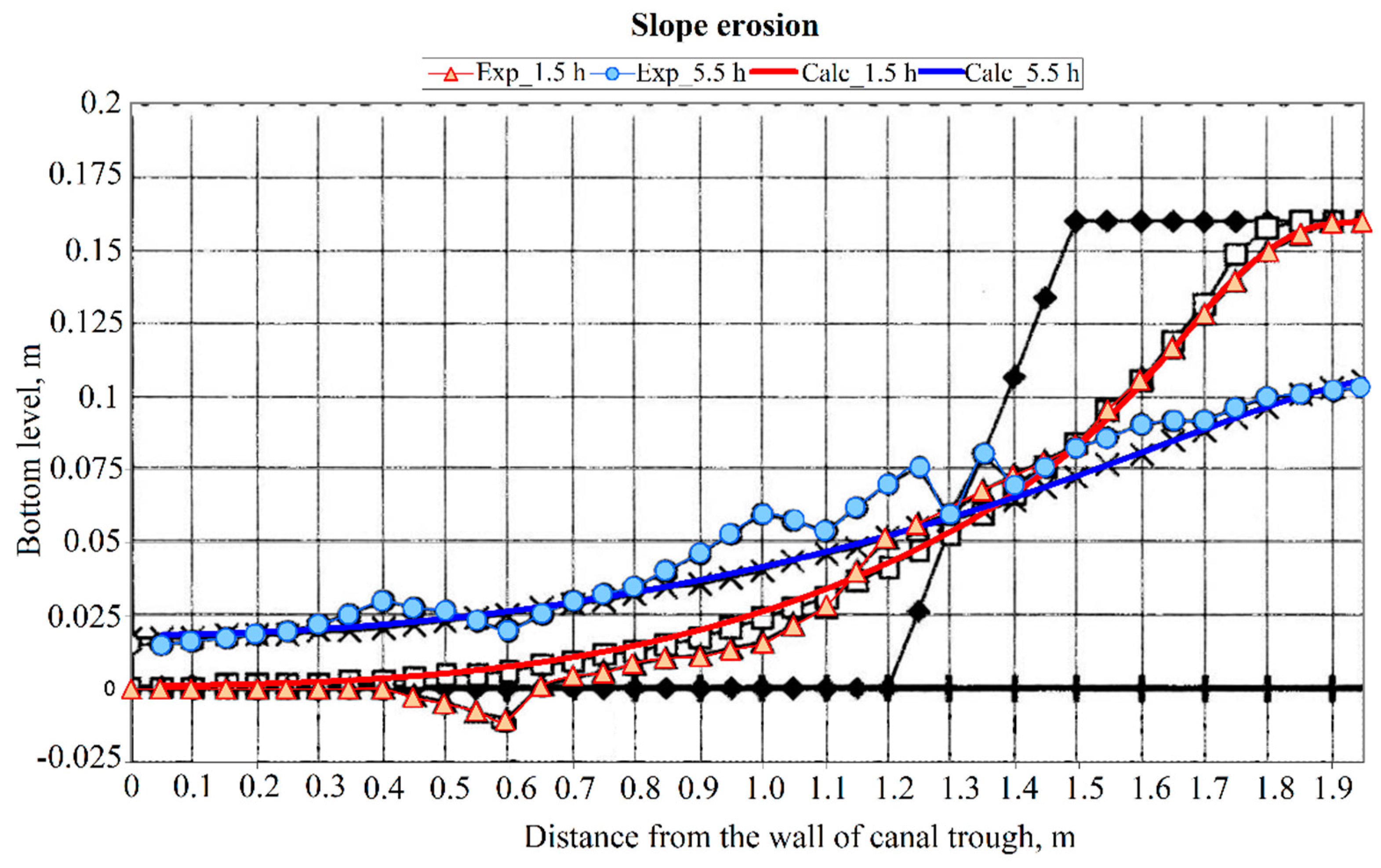

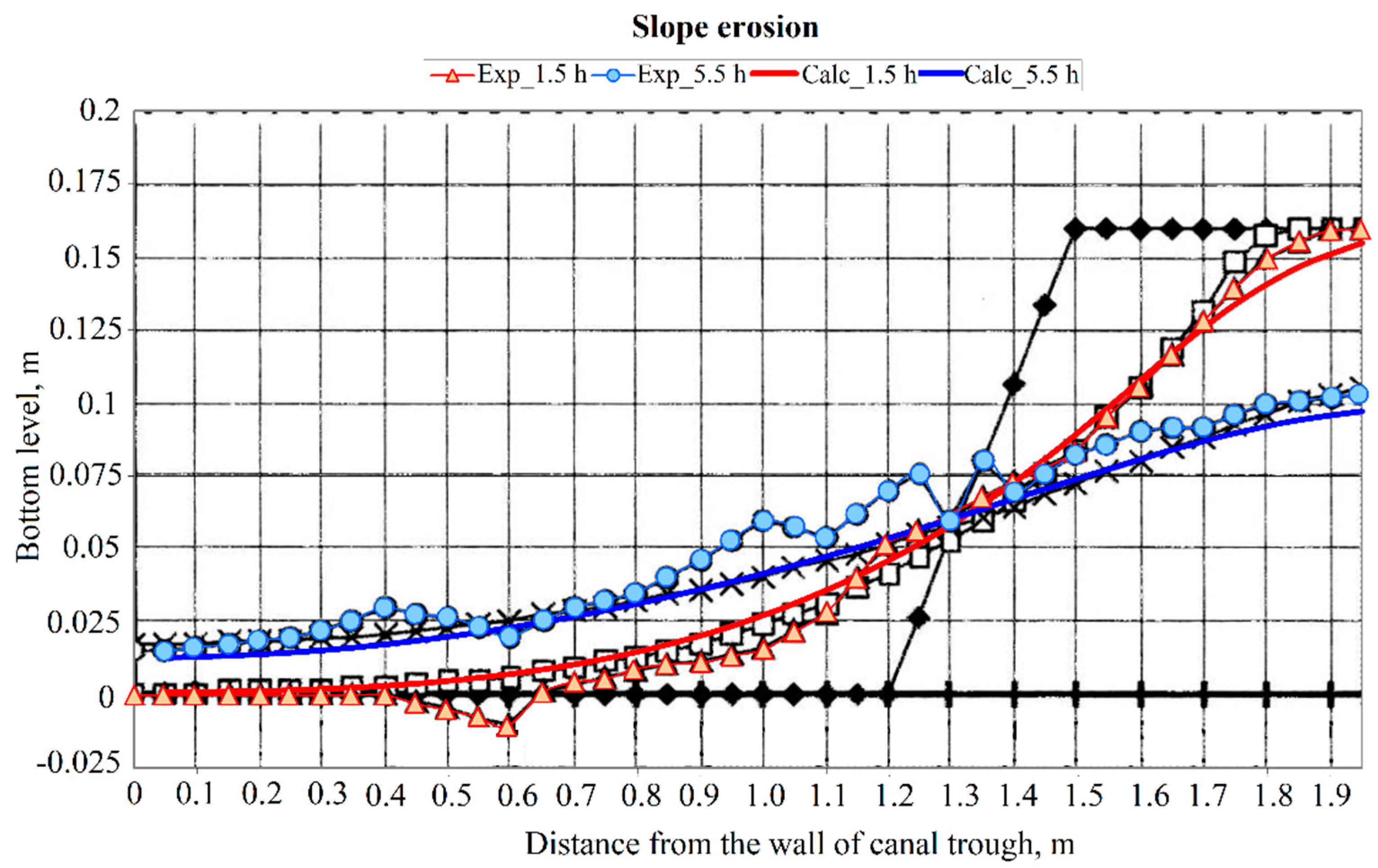

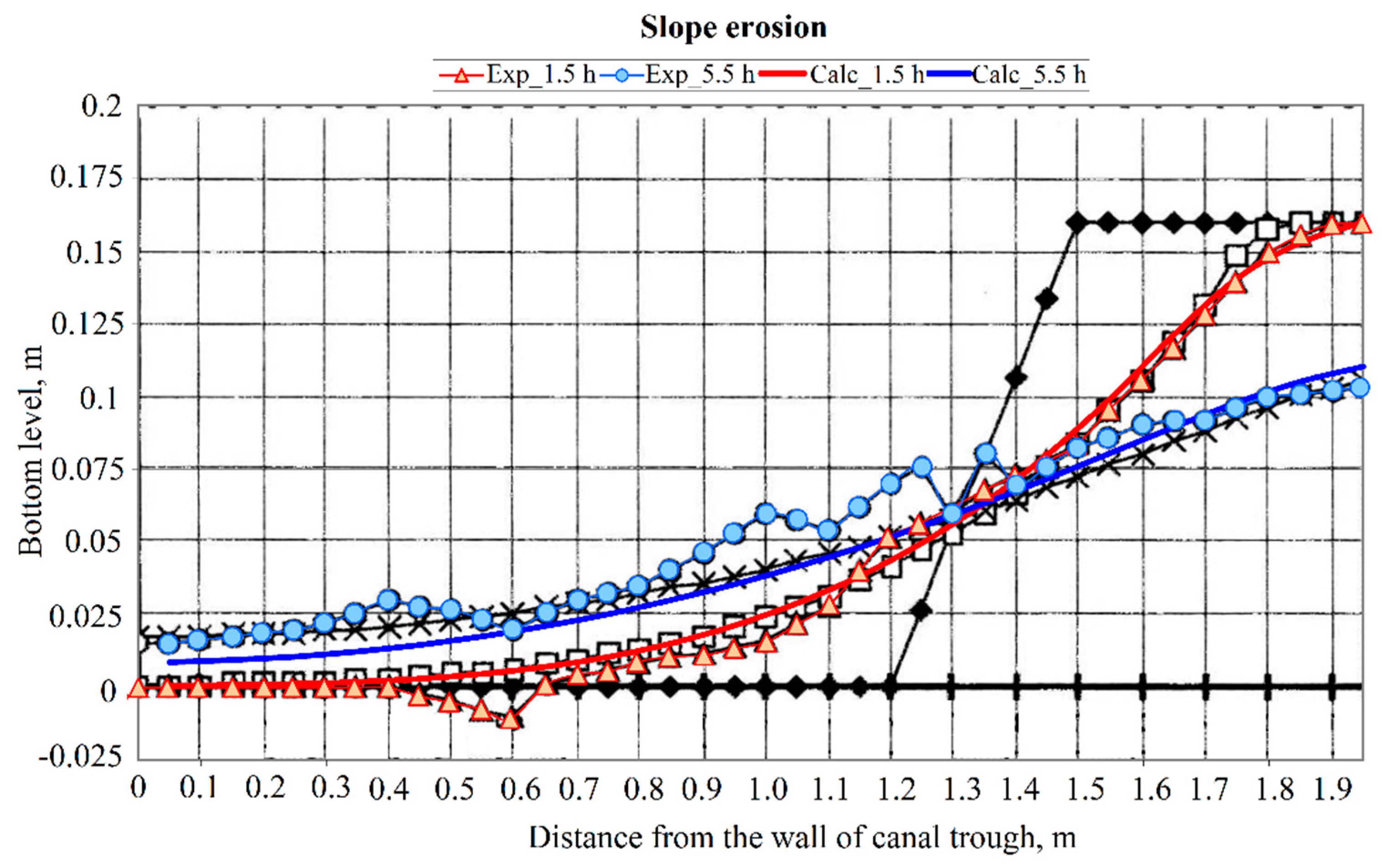

- Numerical studies were conducted to investigate the channel deformation, providing insights into the nature and intensity of these deformations. A comparison with the experimental data demonstrated a good agreement with the experimental results. However, it is worth noting that the optimal values of the empirical coefficients varied between the different experiments, highlighting the need for further work to establish more universal closing relations for the model.

- Verifying the model using field data is crucial for enhancing its applicability and reliability. Additionally, the extension of the model to account for hydraulically heterogeneous soils is a promising avenue because the concentration transfer equation (Equation 4) allows for independent calculations of different particle fractions, assuming that the total concentration of particles in the flow is not excessively high.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Belikov, V. V.; Zaitsev, A. A.; Militeev, A. N. Mathematical modeling of complex reaches of large river channels. Water Resources 2002, 29, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanenko, S. A.; Koryavov, P. P.; Militeev, A. N. Modern computational technologies for calculating open flow dynamics. Water Resources 2002, 29, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelkoff, T. Numerical solution of Saint-Venant equations. Journal of the Hydraulics Division 1970, 96, 223–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, R. L.; Moin, S. A. Finite element solution of Saint-Venant equations. Journal of the Hydraulics Division 1976, 102, 759–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastin, G.; Coron, J. M.; d'Andréa-Novel, B. On Lyapunov stability of linearized Saint-Venant equations for a sloping channel. Networks and Heterogeneous Media 2009, 4, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, X.; Khan, A. A.; Wang, S. S. Upwind conservative scheme for the Saint-Venant equations. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 2004, 130, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Hu, C.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, J. Lattice Boltzmann method for the Saint–Venant equations. Journal of Hydrology 2015, 524, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litrico, X.; Fromion, V.; Baume, J. P.; Arranja, C.; Rijo, M. Experimental validation of a methodology to control irrigation canals based on Saint-Venant equations. Control Engineering Practice 2005, 13, 1425–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belikov, V. V.; Zaitsev, A. A.; Militeev, A. N. Numerical modeling of flow kinematics in a segment of inerodable channel. Water Resources 2001, 28, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, F.; Ducharne, A.; Flipo, N.; Oudin, L.; Ledoux, E. Impact of river bed morphology on discharge and water levels simulated by a 1D Saint–Venant hydraulic model at regional scale. Journal of Hydrology 2013, 476, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisset, P.; Monnier, J.; Garambois, P. A.; Roux, H. On the assimilation of altimetric data in 1D Saint–Venant river flow models. Advances in Water Resources 2018, 119, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader, M. Y. A.; Badé, R.; Saley, B. Study of the 1D Saint-Venant equations and application to the simulation of a flood problem. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics 2020, 8, 1193. [Google Scholar]

- Vila, J. P.; Chazel, F.; Noble, P. 2D versus 1D models for shallow water equations. Procedia IUTAM 2017, 20, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Nieto, E. D.; Marin, J.; Monnier, J. Coupling superposed 1D and 2D shallow-water models: Source terms in finite volume schemes. Computers & Fluids 2010, 39, 1070–1082. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, D. 1D–2D coupled numerical model for shallow-water flows. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 2012, 138, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Hernández, M.; García-Navarro, P.; Burguete, J.; Brufau, P. A conservative strategy to couple 1D and 2D models for shallow water flow simulation. Computers & Fluids 2013, 81, 26–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ongdas, N.; Akiyanova, F.; Karakulov, Y.; Muratbayeva, A.; Zinabdin, N. Application of HEC-RAS (2D) for flood hazard maps generation for Yesil (Ishim) River in Kazakhstan. Water 2020, 12, 2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihu-Pintilie, A.; Cîmpianu, C. I.; Stoleriu, C. C.; Pérez, M. N.; Paveluc, L. E. Using high-density LiDAR data and 2D streamflow hydraulic modeling to improve urban flood hazard maps: A HEC-RAS multi-scenario approach. Water 2019, 11, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shustikova, I.; Domeneghetti, A.; Neal, J. C.; Bates, P.; Castellarin, A. Comparing 2D capabilities of HEC-RAS and LISFLOOD-FP on complex topography. Hydrological Sciences Journal 2019, 64, 1769–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalakkottukara, N. T.; Thomas, J.; Watkins, M. K.; Holland, B. C.; Oommen, T.; Grover, H. Suitability of the height above nearest drainage (HAND) model for flood inundation mapping in data-scarce regions: A comparative analysis with hydrodynamic models. Earth Science Informatics 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Cendon, M. E.; Cea, L.; Puertas, J. The shallow water model: The relevance of geometry and turbulence. Monografias de la Real Academia de Ciencias de Zaragoza 2009, 31, 217–236. [Google Scholar]

- Nadaoka, K.; Yagi, H. Shallow-water turbulence modeling and horizontal large-eddy computation of river flow. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 1998, 124, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J. H. Turbulence modelling of shallow water flows using Kolmogorov approach. Computers & Fluids 2015, 115, 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Camporeale, C.; Canuto, C.; Ridolfi, L. A spectral approach for the stability analysis of turbulent open-channel flows over granular beds. Theoretical and Computational Fluid Dynamics 2012, 26, 51–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchi, I. Considerations on the limits of integration field of de Saint Venant's equation for free surface flows. Meccanica 1972, 7, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Militeev, A. N.; Bazarov, D. R. A two-dimensional mathematical model of the horizontal deformations of river channels. Water Resources 1999, 26, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bazarov, D.; Markova, I.; Raimova, I.; Sultanov, S. Water flow motion in the vehicle of main channels. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2020, 883, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyatkher, V. M.; Militeev, A. N.; Togunova, N. P. Investigation of the distribution of currents in the lower pools of hydraulic structures by numerical methods. Hydrotechnical Construction 1978, 12, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazarov, D.; Vatin, N.; Norkulov, B.; Vokhidov, O.; Raimova, I. Mathematical model of deformation of the river channel in the area of the damless water intake. In Springer International Publishing 2022, pp. 1–15.

- Duc, B. M.; Wenka, T.; Rodi, W. Numerical modeling of bed deformation in laboratory channels. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 2004, 130, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J. G.; Julien, P. Y. Numerical simulation of meandering evolution. Journal of Hydrology 2010, 391, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, S. E.; Alabyan, A. M.; Van de Wiel, M. J. Numerical simulation of bank erosion and channel migration in meandering rivers. Water Resources Research 2002, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Xu, Y. J.; Xu, W.; Cheng, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, W. Riverbed changes of the uppermost Atchafalaya River, U.S.A.—A case study of channel dynamics in large man-controlled alluvial river confluences. Water 2020, 12, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaveh, K.; Reisenbüchler, M.; Lamichhane, S.; Liepert, T.; Nguyen, N. D.; Bui, M. D.; Rutschmann, P. A comparative study of comprehensive modeling systems for sediment transport in a curved open channel. Water 2019, 11, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, G.; Park, H.; Byeon, S. Hydraulic jump and energy dissipation with sluice gate. Water 2015, 7, 5115–5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladkov, G.; Habel, M.; Babiński, Z.; Belyakov, P. Sediment transport and water flow resistance in alluvial river channels: Modified model of transport of non-uniform grain-size sediments. Water 2021, 13, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, B.; Chen, H.; Fang, W.; Yu, T. LSTM-based deformation prediction model of the embankment dam of the Danjiangkou Hydropower Station. Water 2022, 14, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Yuan, T.; Zhao, F.; Chen, G.; Tian, W.; Li, J. Local scour reduction around cylindrical piers using permeable collars in clear water. Water 2023, 15, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhao, B.; Dapeng, Z.; Zhu, K. Numerical simulation of two-dimensional dam failure and free-side deformation flow studies. Water 2023, 15, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Xu, H. A study on the stability of laminar open-channel flow over a sandy rippled bed. Science China Series E-Technological Sciences 2005, 48, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Barba, F.; Picano, F. Direct numerical simulation of the scouring of a brittle streambed in a turbulent channel flow. Acta Mechanica 2021, 232, 4705–4728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camporeale, C.; Canuto, C.; Ridolfi, L. A spectral approach for the stability analysis of turbulent open-channel flows over granular beds. Theoretical and Computational Fluid Dynamics 2012, 26, 51–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchi, I. Considerations on the limits of integration field of de Saint Venant's equation for free surface flows. Meccanica 1972, 7, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fraction Diameter (mm) | 1-0.5 | 0.5-0.25 | 0.25-0.1 | <0.1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content (%) | 0.2 | 31.9 | 67.7 | 0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).