Submitted:

04 December 2023

Posted:

05 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals and Design

2.2. Growth Performance

2.3. Sample Collection

2.4. Measurements of Biochemical Parameters in Serum

2.5. Assessment of Cecal Microflora Contents by 16S rRNA Sequencing

2.6. Short Chain Fatty Acid Concentration Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Growth Performance

3.2. Serum Metabolite Index

3.3. Antioxidant Index in Serum

3.4. Immunoglobulin and Cytokines Index in Serum

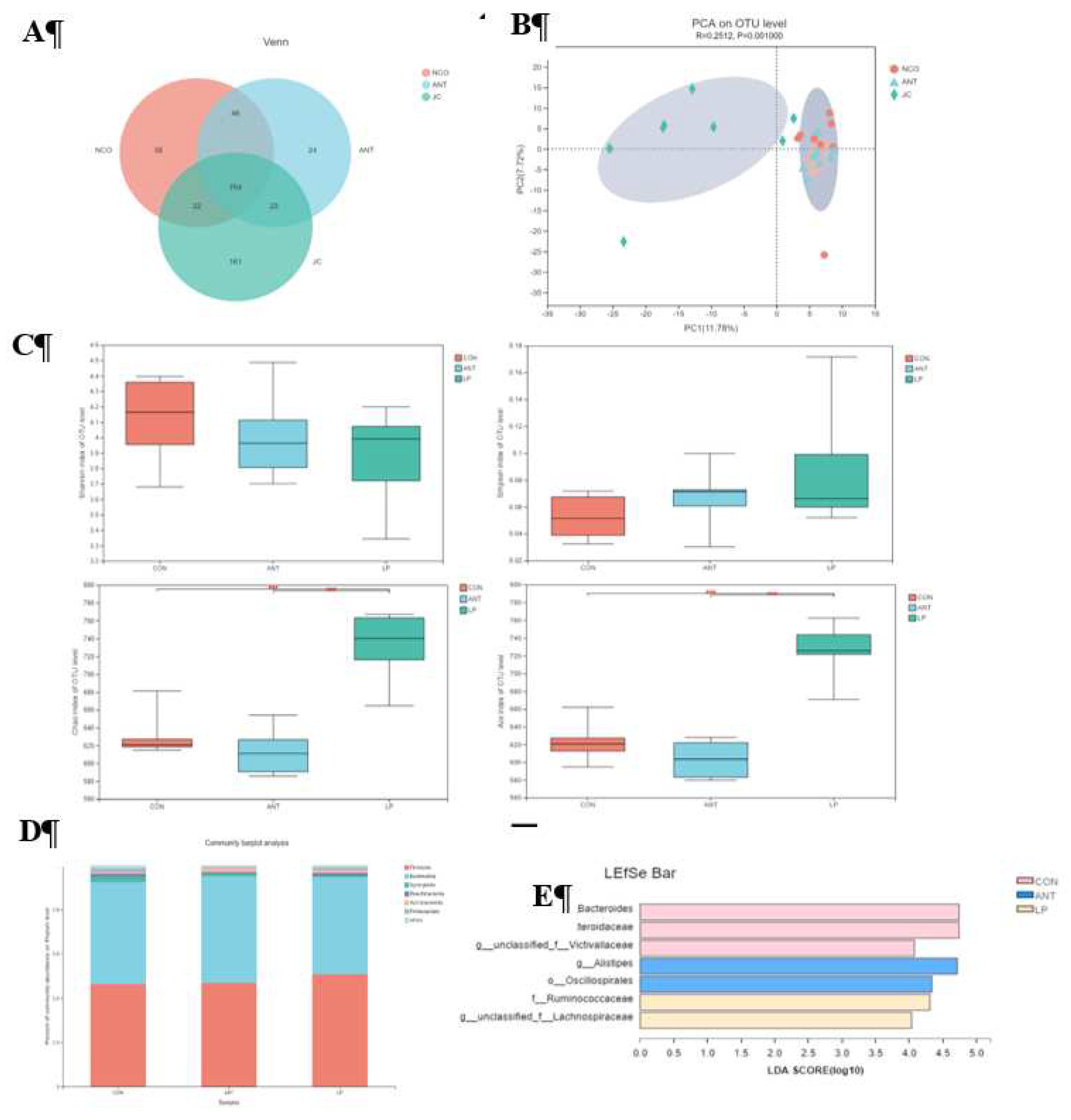

3.5. Microflora Structure in the Cecal Contents

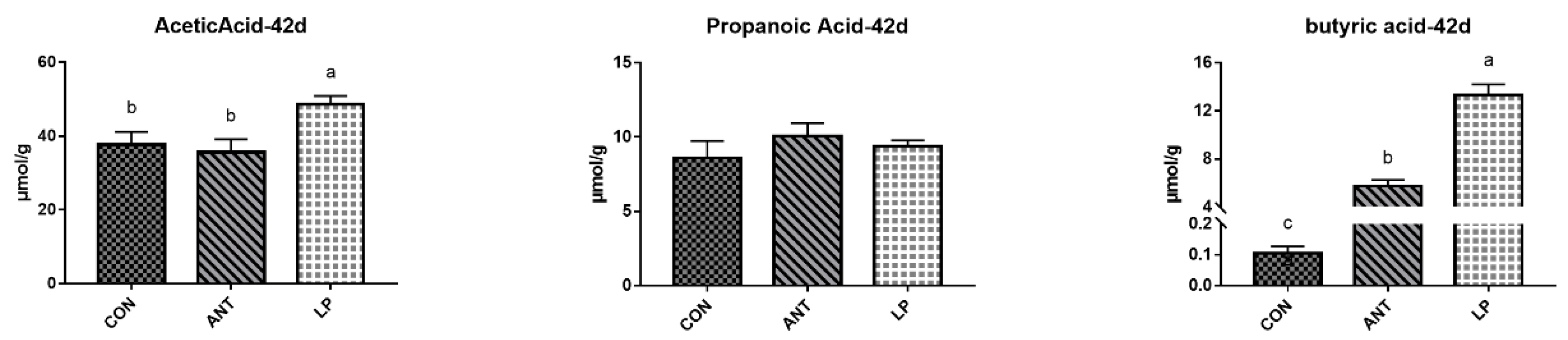

3.6. Short Chain Fatty Acid Concentrations

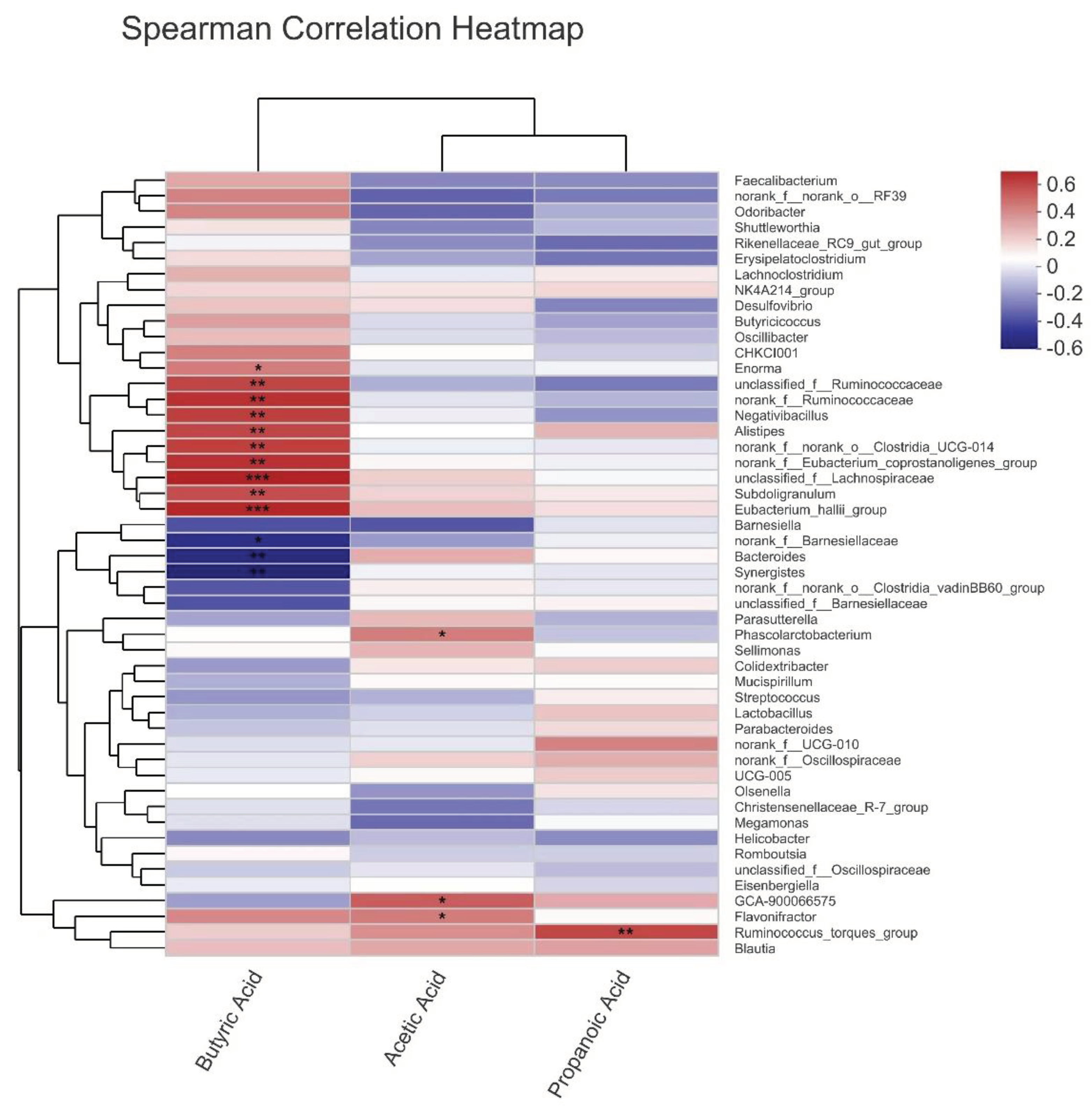

3.7. Link between Cecal Bacteria Community and Short Chain Fatty Acid

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Robins, A. and Phillips, CJC. International approaches to the welfare of meat chickens. Worlds Poult. Sci. J. 2011, 67, 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellet, C.; Rushton, J. World food security, globalisation and animal farming: unlocking dominant paradigms of animal health science. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2019, 38, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Joint FAO/OIE/WHO Expert Workshop on Non-Human Antimicrobial Usage and Antimicrobial Resistance: Scientific Assessment; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; No. WHO/CDS/CPE/ZFK/2004.7. [Google Scholar]

- Aidara-Kane, A.; Angulo, F.J.; Conly, J.M.; Minato, Y.; Silbergeld, E.K.; McEwen, S.A.; Collignon, P.J.; WHO Guideline Development Group. World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines on use of medically important antimicrobials in food-producing animals. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagawany, M.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Farag, M.R.; Sachan, S.; Karthik, K.; Dhama, K. The use of probiotics as eco-friendly alternatives for antibiotics in poultry nutrition. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2018, 25, 10611–10618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mingmongkolchai, S.; Panbangred, W. Bacillus probiotics: an alternative to antibiotics for livestock production. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 124, 1334–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khalaifah, H.S. Benefits of probiotics and/or prebiotics for antibiotic-reduced poultry. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 3807–3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddik, H.A.; Bendali, F.; Gancel, F.; Fliss, I.; Spano, G.; Drider, D. Lactobacillus plantarum and Its Probiotic and Food Potentialities. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2017, 9(2), 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, M.; Rodriguez, M.; Garcia, F.; Fernandez, E.; Fuentes, M.C.; Cune, J. Probiotic properties of Lactobacillus planta-rum CECT 7315 and CECT 7316 isolated from faeces of healthy children. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 54, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Niu, C.; Yang, Z.; Li, S. Potential probiotic characterization of Lactobacillus plan-tarum strains isolated from Inner Mongolia “Hurood” cheese. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 24, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Tiwari, S.K. Probiotic Potential of Lactoplantibacillus plantarum LD1 Isolated from Batter of Dosa, a South Indian Fermented Food. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins. 2014, 6, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Tao, X.; Wan, C.; Li, S.; Xu, H.; Xu, F.; Shah, N.P.; Wei, H. In vitro probiotic characteristics of Lactoplantibacillus plantarum ZDY 2013 and its modulatory effect on gut microbiota of mice. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 5850–5861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Zhang, F.; Wan, C.; Xiong, Y.; Shah, N.P.; Wei, H.; Tao, X. Evaluation of probiotic properties of Lactobacillus plantarum WLPL04 isolated from human breast milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 1736–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.J.; Lee, J.E.; Lim, S.M.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, N.K.; Paik, H.D. Antioxidant and immune-enhancing effects of probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum 200655 isolated from kimchi. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 28, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duary, R.K.; Bhausaheb, M.A.; Batish, V.K.; Grover, S. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory efficacy of indigenous probiotic Lactoplantibacillus plantarum Lp91 in colitis mouse model. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 4765–4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satish Kumar, C.S.; Kondal Reddy, K.; Reddy, A.G.; Vinoth, A.; Ch, S.R.; Boobalan, G.; Rao, G.S. Protective effect of Lactobacillus plantarum 21, a probiotic on trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid-induced ulcerative colitis in rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015, 25, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Peng, Q.; Jia, H.M.; Zeng, X.F.; Zhu, J.L.; Hou, C.L.; Liu, X.T.; Yang, F.J.; Qiao, S.Y. Prevention of Escherichia coli infection in broiler chickens with Lactobacillus plantarum B1. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 2576–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.R.; Liu, Y.L.; Duan, Y.L.; Wang, F.Y.; Guo, F.S.; Yan, F.; Yang, X.J.; Yang, X. Intestinal toxicity of deoxynivalenol is limited by supplementation with Lactobacillus plantarum JM113 and consequentially altered gut microbiota in broiler chickens. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechno. 2018, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Zeng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Ni, X.Q.; Wang, J.; Jian, P.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Yin, Z.Q.; Pan, K.C.; Jing, B. Lactobacillus plantarum BS22 promotes gut microbial homeostasis in broiler chickens exposed to aflatoxin B1. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl). 2018, 102, e449–e459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thanh, N.T.; Loh, T.C.; Foo, H.L.; Hair-bejo, M.; Azhar, B.K. Effects of feeding metabolite combinations produced by Lactobacillus plantarumon growth performance, faecal microbial population, small intestine villus height and faecal volatile fatty acids in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2009, 50, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gu, Q. Effect of probiotic on growth performance and digestive enzyme activity of Arbor Acres broilers. Res. Vet. Sci. 2010, 89, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, H.M.; Kang, H.K.; Akter, N.; Kim, D.W.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, M.J.; Na, L.P.; Jong, H.B.; Choi, H.C.; Suh, O.S.; Kim, W.K. Supplementation of direct-fed microbials as an alternative to antibiotic on growth performance, immune response, cecal microbial population, and ileal morphology of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2013, 92, 2084–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhan, X.; Zeng, X.; Zhou, L.; Cao, G.; Chen, A.; Yang, C. Effects of dietary supplementation of probiotic, Clostridium butyricum, on growth performance, immune response, intestinal barrier function, and digestive enzyme activity in broiler chickens challenged with Escherichia coli K88. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Q.; Zeng, X.F.; Zhu, J.L.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.T.; Hou, C.L.; Thacker, P.A.; Qiao, S.Y. Effects of dietary Lactobacillus plantarum B1 on growth performance, intestinal microbiota, and short chain fatty acid profiles in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2016, 95, 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deepthi, B.V.; Somashekaraiah, R.; Poornachandra Rao, K.; Deepa, N.; Dharanesha, N.K.; Girish, K.S.; Sreenivasa, M.Y. Lactoplantibacillus plantarum MYS6 Ameliorates Fumonisin B1-Induced Hepatorenal Damage in Broilers. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, P.; Ma, C.; Sun, Z.; Wang, L.; Huang, S.; Su, X.; Xu, J.; Zhang, H. Feed-additive probiotics accelerate yet antibiotics delay intestinal microbiota maturation in broiler chicken. Microbiome. 2017, 5, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donsbough, A.L.; Powell, S.; Waguespack, A.; Bidner, T.D.; Southern, L.L. Uric acid, urea, and ammonia concentrations in serum and uric acid concentration in excreta as indicators of amino acid utilization in diets for broilers. Poult. Sci. 2010, 89, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, N.; Chen, G.; Liu, H. Antioxidative Categorization of Twenty Amino Acids Based on Experimental Evaluation. Molecules. 2017, 22, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perl, A. Review: Metabolic Control of Immune System Activation in Rheumatic Diseases. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017, 69, 2259–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, W.; Wang, L.; Cheng, S.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, L. Protective Effects of alpha-Lipoic Acid on Vascular Oxidative Stress in Rats with Hyperuricemia. Curr. Med. Sci. 2019, 39, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurutas, E.B. The importance of antioxidants which play the role in cellular response against oxidative/nitrosative stress: current state. Nutr. J. 2016, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Xing, Z.Q.; Li, C.; Wang, J.J.; Wang, Y.P. Molecular mechanisms and in vitro antioxidant effects of Lactobacillus plantarum MA2. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1642–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.M.; Cao, G.T.; Ferket, P.R.; Liu, T.T.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, Y.P.; Chen, A.G. Effects of probiotic, Clostridium butyricum, on growth performance, immune function, and cecal microflora in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2012, 91, 2121–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Si, J.; Tan, F.; Park, K.Y.; Zhao, X. Lactobacillus plantarum KSFY06 Prevents Inflammatory Response and Oxidative Stress in Acute Liver Injury Induced by D-Gal/LPS in Mice. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2021, 15, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izuddin, W.I.; Humam, A.M.; Loh, T.C.; Foo, H.L.; Samsudin, A.A. Dietary Postbiotic Lactobacillus plantarum Improves Serum and Ruminal Antioxidant Activity and Upregulates Hepatic Antioxidant Enzymes and Ruminal Barrier Function in Post-Weaning Lambs. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020, 9, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.Y.; Zhen, W.R.; Geng, Y.Q.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Y.M. Effects of dietary Enterococcus faecium NCIMB 11181 supplementation on growth performance and cellular and humoral immune responses in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Zhang, B.; Li, J.; Zhu, L. Effects of fermented feed on growth performance, immune response, and antioxidant capacity in laying hen chicks and the underlying molecular mechanism involving nuclear factor-kappaB. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 2573–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humam, A.M.; Loh, T.C.; Foo, H.L.; Samsudin, A.A.; Mustapha, N.M.; Zulkifli, I.; Izuddin, W.I. Effects of Feeding Different Postbiotics Produced by Lactobacillus plantarum on Growth Performance, Carcass Yield, Intestinal Morphology, Gut Microbiota Composition, Immune Status, and Growth Gene Expression in Broilers under Heat Stress. Animals (Basel). 2019, 9, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.Y.; Moudgil., K.D. Immunomodulation of autoimmune arthritis by pro-inflammatory cytokines. Cytokine. 2017, 98, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabat, R.; Grutz, G.; Warszawska, K.; Kirsch, S.; Witte, E.; Wolk, K.; Geginat, J. Biology of interleukin-10. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010, 21, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Chen, Y.; Yu, L.; Wang, J.; Huang, M.; Zhu, N. Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum on intestinal integrity and immune responses of egg-laying chickens infected with Clostridium perfringens under the free-range or the specific pathogen free environment. BMC Vet. Res. 2020, 16, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Chang, S.Y.; Bogere, P.; Won, K.; Choi, J.Y.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, H.K.; Hur, J.; Park, B.Y.; Kim, Y.; Heo, J. Beneficial roles of probiotics on the modulation of gut microbiota and immune response in pigs. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0220843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, R.; Das, R.; Oak, S.; Mishra, P. Probiotics (Direct-Fed Microbials) in Poultry Nutrition and Their Effects on Nutrient Utilization, Growth and Laying Performance, and Gut Health: A Systematic Review. Animals (Basel). 2020, 10, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.M.; Foo, H.L.; Loh, T.C.; Lim, E.T.C.; Abdul Mutalib, N.E. Comparative Studies of Inhibitory and Antioxidant Activities, and Organic Acids Compositions of Postbiotics Produced by Probiotic Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Strains Isolated From Malaysian Foods. Front Vet Sci. 2021, 7, 602280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessione, E. Lactic acid bacteria contribution to gut microbiota complexity: lights and shadows. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012, 2, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedford, A.; Yu, H.; Squires, E.J.; Leeson, S.; Gong, J. Effects of supplementation level and feeding schedule of butyric acid glycerides on the growth performance and carcass composition of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 3221–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljumaah, M.R.; Alkhulaifi, M.M.; Abudabos, A.M.; Alabdullatifb, A.; El-Mubarak, A.H.; Al Suliman, A.R.; Stanley, D. Organic acid blend supplementation increases butyric acid and acetic acid production in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium challenged broilers. PLoS One. 2020, 15, e0232831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, C.; Ahmad, H.; Zhang, H.; He, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, T. Influence of Butyric acid Loaded Clinoptilolite Dietary Supplementation on Growth Performance, Development of Intestine and Antioxidant Capacity in Broiler Chickens. Plos One. 2016, 11, e0154410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, Q.F.; Gao, F.; Dai, S.F.; Chen, J.; Zhou, G.H. Sodium butyric acid maintains growth performance by regulating the immune response in broiler chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2011, 52, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, X.; Ji, J.; Qu, H.; Wang, J.; Shu, D.M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, T.F.; Li, Y.; Luo., C.L. Effects of sodium butyric acid on intestinal health and gut microbiota composition during intestinal inflammation progression in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 4449–4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Yang, H.; Wang, X.; Xia, W.; Lv, W.; Xiao, Y.; Zou, X. Early intervention with cecal fermentation brothregulates the colonization and development of gut microbiota inbroiler chickens. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaheen, S.; Kim, S.W.; Haley, B.J.; Van Kessel, J.A.S.; Biswas, D. Alternative Growth Promoters Modulate Broiler Gut Microbiome and Enhance Body Weight Gain. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, Z.; Shi, D.; Li, Z.; Xiao, Y. Preliminary Study on the Effect of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens TL on Cecal Bacterial Community Structure of Broiler Chickens. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 5431354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | 1-21d | 22-42d |

|---|---|---|

| Ingredients(%) | ||

| Corn | 61.80 | 65.60 |

| Soybean meal | 22.50 | 17.55 |

| Extruded soybean | 8.45 | 10.00 |

| Import fish meal | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| CaHPO4 | 1.66 | 1.45 |

| Limestone | 1.10 | 1.00 |

| NaCl | 0.32 | 0.30 |

| DL- methionine | 0.16 | 0.10 |

| L- lysine | 0.01 | |

| Premix1 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Nutrition levels | ||

| Metabolizable energy (MJ/kg) | 12.45 | 12.70 |

| Crude protein | 21.00 | 19.20 |

| Lysine | 1.15 | 0.95 |

| Methionine | 0.54 | 0.44 |

| Calcium | 0.99 | 0.89 |

| Available phosphorus | 0.53 | 0.49 |

| Items | SEM | P-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | ANT | LP | |||

| BW,g | |||||

| 1 d | 38.29 | 39.52 | 38.32 | 0.401 | 0.361 |

| 21 d | 732.08b | 778.24a | 800.13a | 8.945 | 0.001 |

| 42 d | 1875.86b | 1926.47b | 2124.36a | 40.63 | 0.019 |

| ADG (g/d) | |||||

| 1-21 d | 33.54b | 35.26a | 36.31a | 0.361 | 0.001 |

| 22-42 d | 55.48 b | 56.47b | 64.85 a | 1.764 | 0.048 |

| 1-42 d | 44.51b | 45.87b | 52.57a | 1.205 | 0.005 |

| ADFI,g | |||||

| 1-21 d | 54.02b | 54.42ab | 59.84a | 0.935 | 0.008 |

| 22-42 d | 118.19 | 111.66 | 118.63 | 3.432 | 0.677 |

| 1-42 d | 80.00 | 78.62 | 86.05 | 1.516 | 0.098 |

| F:G | |||||

| 1-21 d | 1.61ab | 1.54b | 1.64a | 0.017 | 0.036 |

| 22-42 d | 2.13a | 1.98ab | 1.83b | 0.046 | 0.023 |

| 1-42 d | 1.80a | 1.72ab | 1.70b | 0.018 | 0.067 |

| Items | SEM | P-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | ANT | LP | |||

| NH3(µmol/L) | 10.83a | 9.03b | 6.54c | 0.490 | 0.001 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.016 | 0.136 |

| UA (µmol/L) | 147.84 | 129.88 | 116.41 | 6.584 | 0.148 |

| XOD (U/L) | 3.83a | 4.30a | 3.10b | 0.168 | 0.005 |

| Items | SEM | P-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | ANT | LP | |||

| GSH-PX (U/mL) | 6. 90 | 7.83 | 8.37 | 0.591 | 0.617 |

| SOD (U/mL) | 12.28b | 12.96ab | 13.22a | 0.155 | 0.026 |

| CAT (U/mL) | 9.98b | 10.79ab | 11.80a | 0.304 | 0.039 |

| MDA (U/mL) | 8.12 | 7.56 | 7.91 | 0.199 | 0.534 |

| Items | SEM | P-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | ANT | LP | |||

| IgA ng/mL | 168.11 | 177.93 | 176.81 | 4.327 | 0.626 |

| IgY ng/mL | 1.49c | 1.79b | 2.07a | 0.067 | 0.001 |

| IgM µg/mL | 3.09c | 3.61b | 4.26a | 0.143 | 0.001 |

| IL-1βpg/mL | 94.19a | 83.02b | 83.02b | 1.900 | 0.011 |

| IL-6pg/mL | 394.04 | 393.77 | 387.22 | 4.480 | 0.801 |

| IL-10pg/mL | 17.43b | 20.82b | 28.43a | 1.272 | 0.001 |

| TNF-αpg/L | 38.74ab | 40.23a | 37.35b | 0.568 | 0.114 |

| INF-β pg/mL | 150.78 | 149.55 | 145.68 | 4.573 | 0.905 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).