1. Introduction

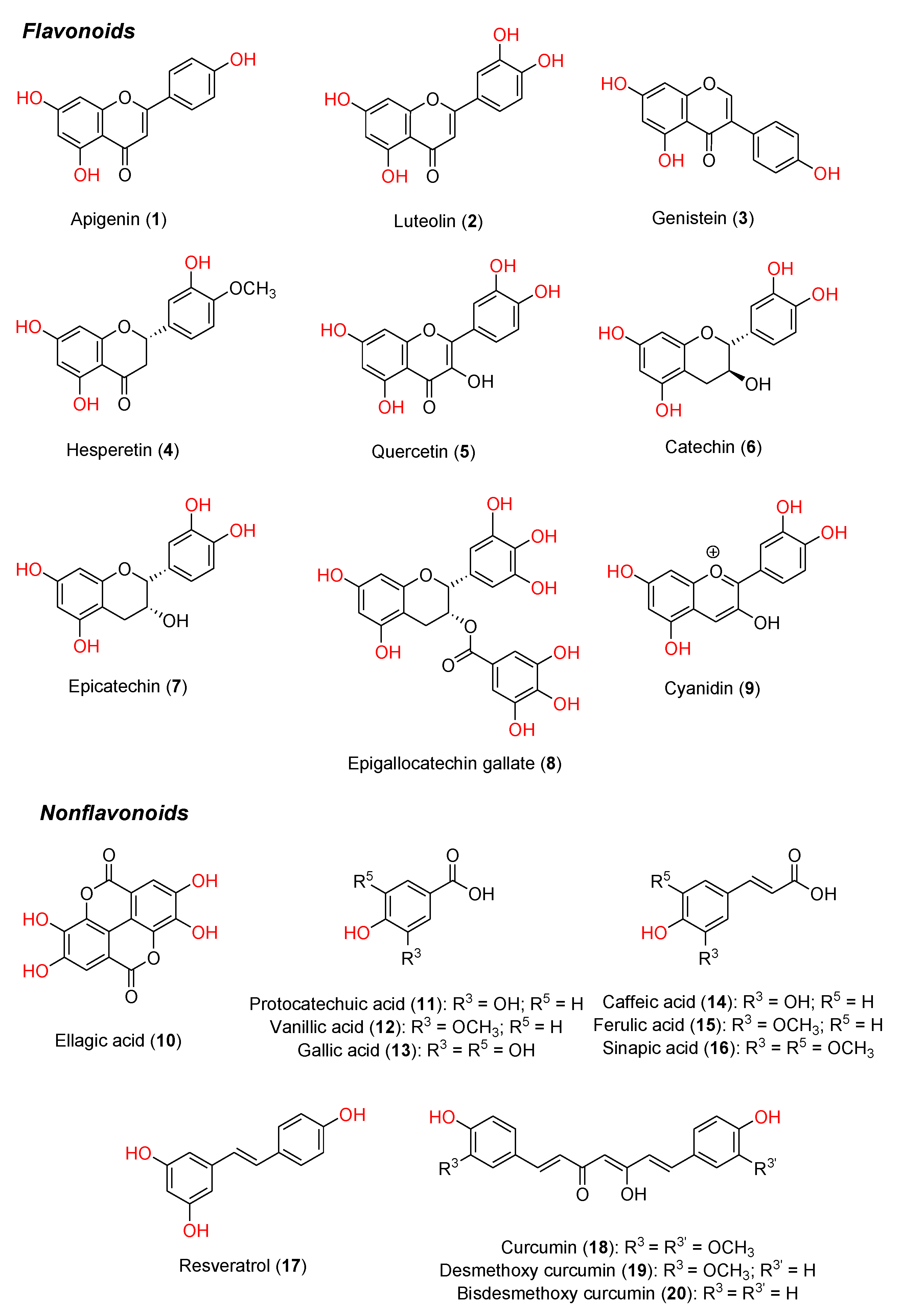

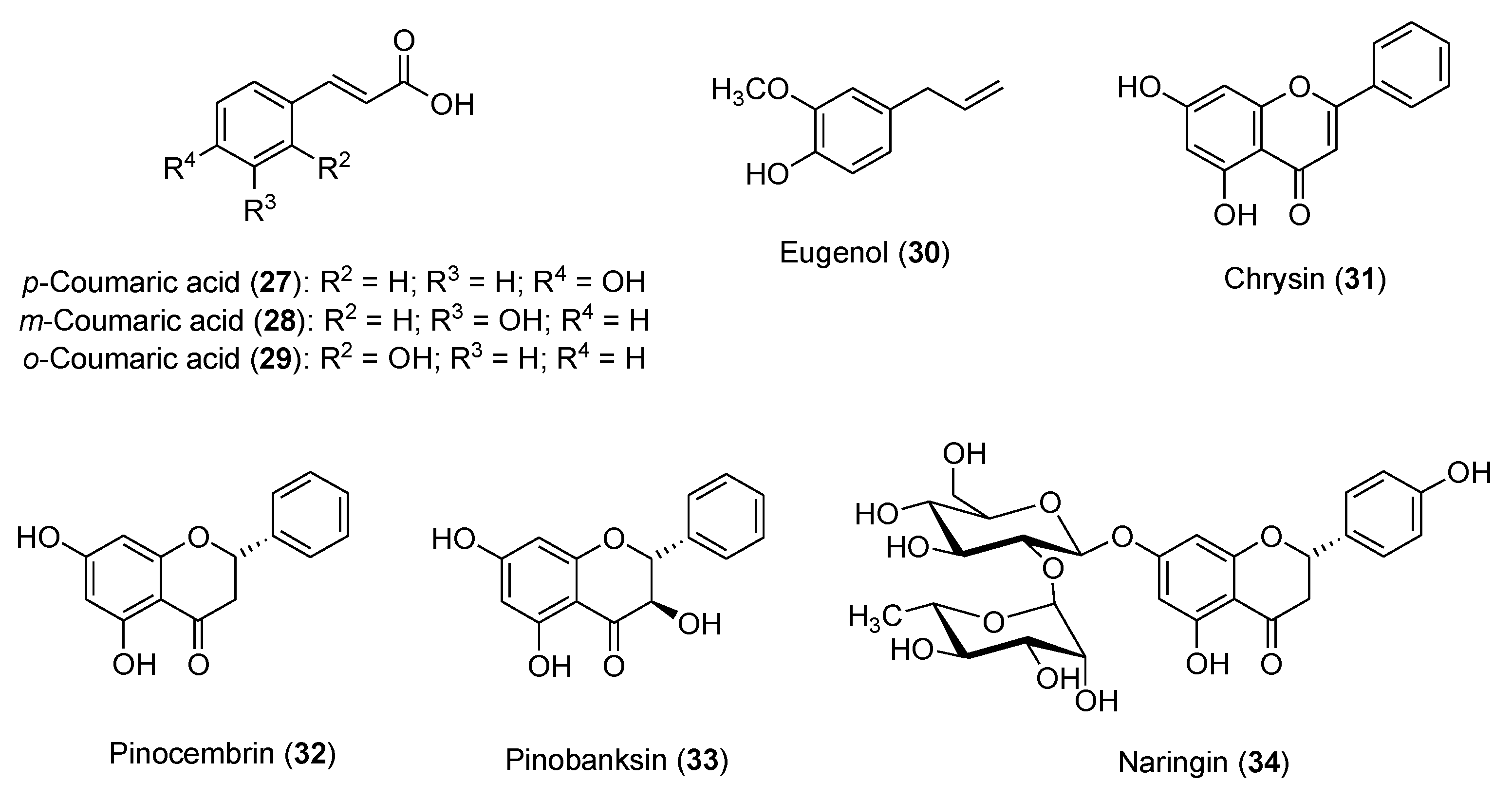

Polyphenols constitute a major class of phytochemicals showing favorable effects in various pathologic conditions. They are plant-derived metabolites mainly originating from acetate-malonate and shikimate biosynthetic pathways, and mostly exist as glycosides or conjugated with other moieties (e.g., amines, carboxylic acids, lipids and other phenols) [1,2]. Natural polyphenols include flavonoids and nonflavonoid compounds (e.g., phenolic acids and their esters, stilbenoids, and curcuminoids) [3]. The structures of a few representative dietary polyphenols are shown in

Figure 1.

Several studies highlighted relationships between dietary polyphenols and lower incidence of cancer, chronic heart diseases and neurodegenerative syndromes [4–6]. The Mediterranean diet is associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, thanks to an adequate intake of olive oil, red wine and anthocyanin-containing fruits and vegetables [7,8]. Other beneficial health effects, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiallergic, antithrombotic and antiviral activities, have been related to dietary polyphenols’ intake [9–11]. Increasing lines of evidence showed a relationship between some of the aforementioned diseases and oxidative stress resulting from the generation of reactive oxygen (ROS) and nitrogen species (RNS) [12], but none of the natural antioxidants has been approved so far for any therapeutic indication, except for the nutrient content claims in dietary supplements and conventional foods.

While the clinical effectiveness of polyphenols in prevention and treatment of cancer has been recently reviewed [6,13], this review aims at evaluating the effectiveness of polyphenols as protective agents against ROS-mediated toxic effects induced by some of the commonly used chemotherapeutic agents, providing a critical look at a sampling of preclinical and last-decade clinical studies, and highlighting some key issues related to new formulations that may increase the potential of these phytochemicals as supplements in tumor chemotherapy.

2. Sources and healthy effects of polyphenols

Based on the diversity of the chromane nucleus and hydroxyl-substitution pattern, flavonoids can be divided into different groups, namely flavones (e.g., apigenin

1, luteolin

2,

Figure 1), isoflavones (e.g., genistein

3), flavanones (e.g., hesperetin

4), flavonols (e.g., quercetin

5), flavanols (e.g., catechin

6, epicatechin

7, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG)

8, anthocyanins (e.g., cyanidin

9), and others, which mostly exist as glycosides in plants. The nonflavonoid compounds include phenolic acids and their esters (e.g., ellagic acid

10, protocatechuic, vanillic and gallic acids

11-

13), cinnamic acid and its derivatives (e.g., caffeic, ferulic and sinapic acids

14-

16), stilbenoids (e.g., resveratrol

17) and curcuminoids (e.g., curcumin

18, desmethoxy curcumin

19, bisdesmethoxy curcumin

20). More complex nonflavonoids molecules are represented by stilbene oligomers, tannins and lignins.

Grape, olive, blueberry, citrus fruits, broccoli and many other vegetables and fruits constitute daily sources of polyphenols [14–16]. Many factors, including environmental conditions, storage, and food processing, have different influence on the content and the profile of polyphenolic components [17]. Indeed, sun exposure, rainfall, different types of culture and the degree of ripeness could affect concentration and chemical diversity, as well as the aglycone/glycoside ratio [18].

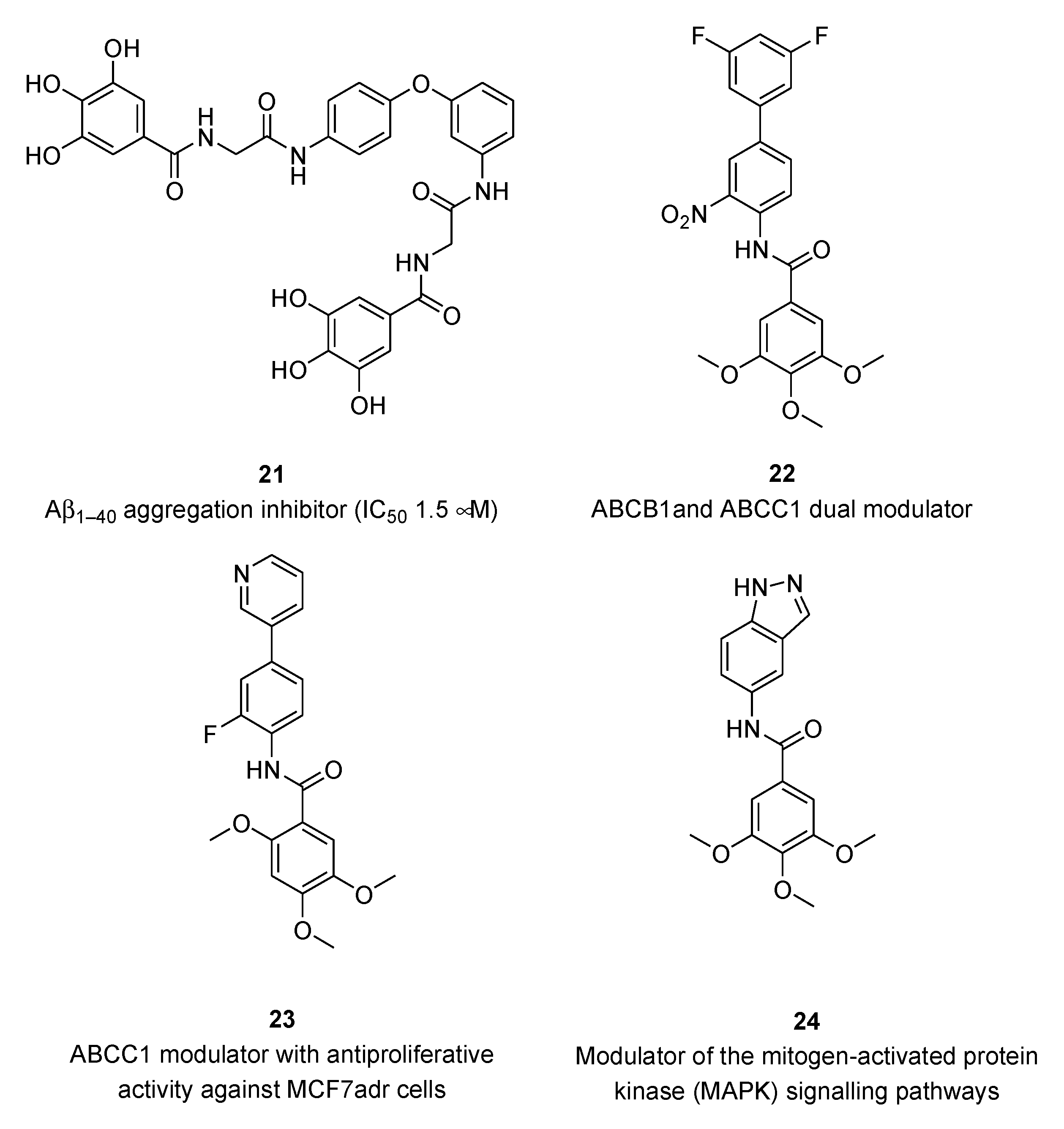

Several studies highlighted the correlation between the consumption of polyphenol-rich foods and a lower incidence of different types of cancer, chronic heart and neurodegenerative diseases [4–6]. However, only a limited number of clinical studies proved a distinct impact of dietary polyphenols on cancer prevention [19,20]. Regarding the Alzheimer’s disease (AD), natural flavonoids and synthetic analogs as multitarget-directed ligands (MTDLs) have been recently reviewed [21]. Useful information on the structure-activity relationships (SARs) and pharmacophores of flavonoid-based derivatives has been reported for a number of targets playing key roles in the multifactorial AD pathogenesis, e.g., enzymatic inhibition of cholinesterases (ChEs), β-secretase (BACE-1), and monoamine oxidases (MAO), as well as interference with amyloid-β (Aβ) aggregation, oxidative stress and metal imbalance. Amongst polyphenols in clinical trials for the management of AD [22], STA-1 has entered phase-2 by Sinphar Pharmaceuticals [23] as add-on therapy to donepezil treatment. STA-1 is an herbal remedy from traditional Chinese medicine, containing flavonoids and other polyphenolic constituents, with broad activity spectrum [24]. Semisynthetic derivatives of gallic, protocatechuic and vanillic acids (e.g.,

21,

Figure 2) proved to be in vitro inhibitors of β-amyloid peptide Aβ

1-40 aggregation [25] and potent modulators of ATP-binding cassette transporters (e.g.,

22 and

23) involved in multidrug resistance (MDR) [26,27].

Some trimethoxygalloyl-based compounds (e.g., 24) may be able to activate TNFα-induced MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) signaling in murine fibroblasts and human endothelial cells with different MAPK selectivity profiles [28].

3. Polyphenols and oxidative stress

Pathologic conditions, like cancer, cardiovascular disease and ischemia-reperfusion injury, are related to oxidative stress caused by ROS and RNS [12]. Preventing formation and/or scavenging cellular ROS, such as superoxide (O2∙-), hydroxyl (HO∙), peroxyl (HOO∙) and alkoxyl (ROO∙) radicals, and RNS (e.g., peroxynitrite, ONOO-), is a main mechanism underlying polyphenols’ antioxidant activity [11,12,15,16]. The neuroprotective effects of kuromanin (i.e., the 3-O-glucoside of cyanidin) and other anthocyanins have been related to its activity against nitrosative stress [29].

ROS and RNS play beneficial or deleterious roles in cells depending on their concentrations. At low concentrations, ROS and RNS modulate intracellular signaling and enzyme activity, whereas at high concentrations give rise to an imbalance between reactive species formation and antioxidant defenses [30,31]. Such disequilibrium leads to increased level of the oxidant species, which can produce radical-mediated DNA injury, lipid peroxidation and protein damage, ultimately causing cell death via apoptosis or necrosis.

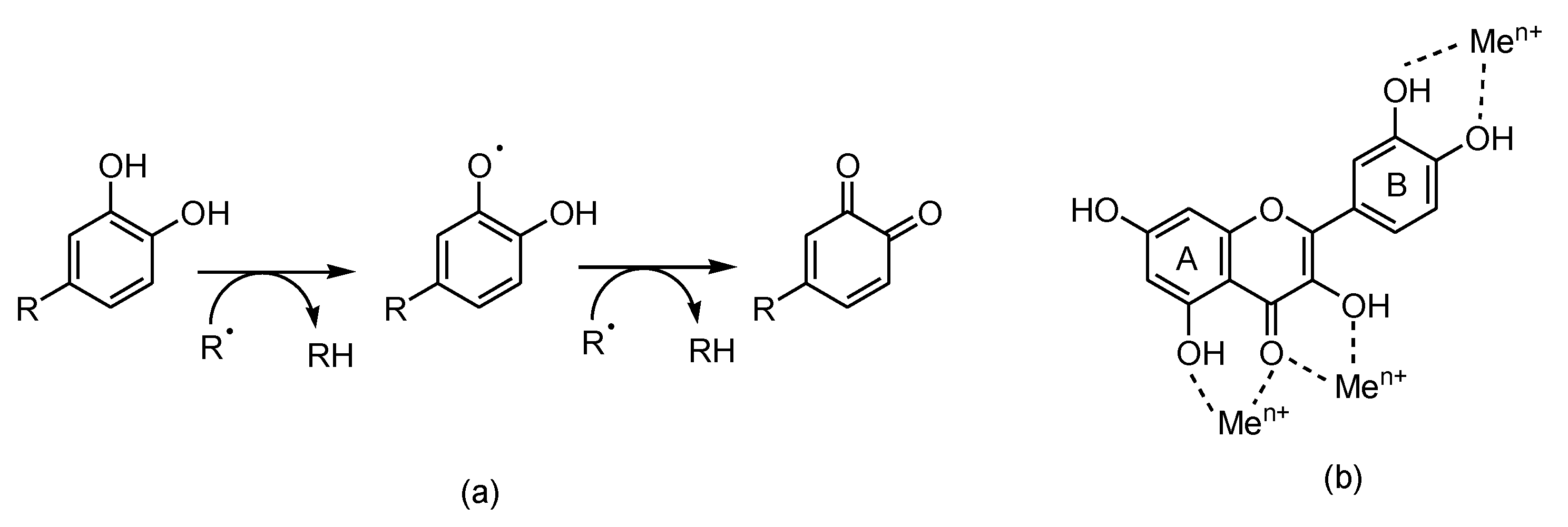

As reducing agents, polyphenols suppress the generation of free radicals and reduce the rate of oxidation by inhibiting the formation or deactivating the active species and precursors of free radicals. In addition to the metal (iron, copper, etc.) chelating ability, flavonoids (in particular, quercetin) inhibit ROS and RNS generation (

Figure 3). Structure-antioxidant activity relationships showed the importance of the highly conjugated aromatic ring and the hydroxylation pattern [32–34].

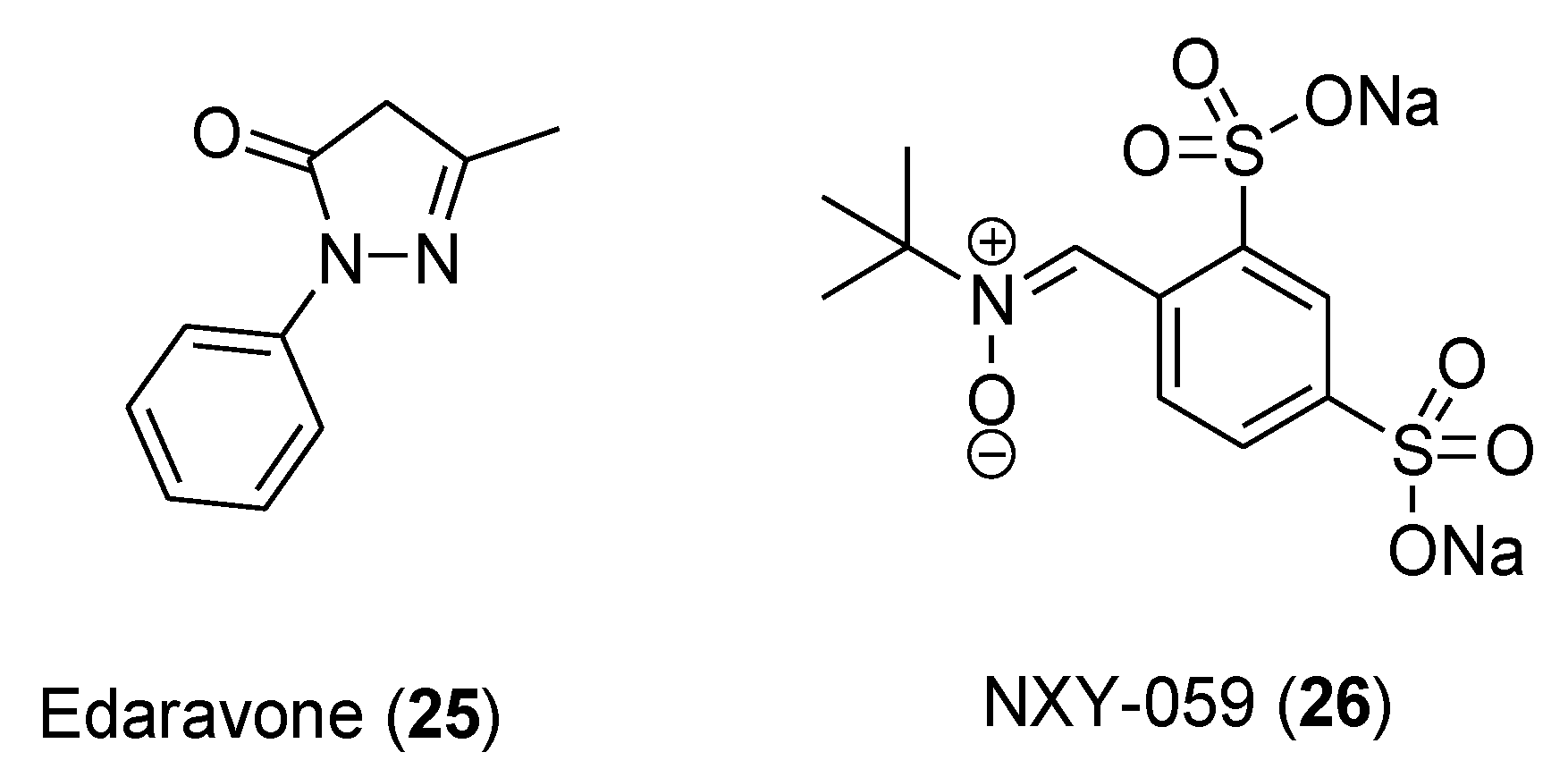

However, so far neither bioactive polyphenols nor synthetic antioxidants have been approved for any indication. To the best of our knowledge, edaravone (Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation), a synthetic pyrazolone derivative (

25,

Figure 4) acting as free radical scavenger, has been recently approved for stroke and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [35], whereas the nitrone compound NXY-059 (

26), albeit showing significant effects in the preclinical treatment of acute ischemic stroke, failed to prove clinical efficacy [36].

4. Polyphenols and anticancer activity

The results of epidemiological studies have suggested that the etiology of cancer can be often attributed to changes in lifestyles, ever-increasing urbanization, predominant diet and subsequent changes in environmental conditions [37,38]. Although traditional treatments, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and surgery have a major impact on the treatment of cancer, the generation of toxic side-effects, the emergence of drug resistance and the high cost of therapy represent main issues in the treatment of cancer patients [39]. Therefore, it is important to develop effective and non-toxic anticancer drugs derived from natural product resources. Plant-derived polyphenols are among the most widespread bioactive compounds. They are characterized by high structural diversity which, in turn, generates different ranges of biological properties. Recently, polyphenols have received considerable attention for cancer treatments thanks to fewer side effects and lower toxicity. In this context, epidemiological, preclinical, and clinical research has shown that the daily consumption of polyphenols has a strong correlation with the prevention of different types of cancer. Indeed, many investigations have revealed that polyphenols can exert their anticancer impact by regulating numerous cellular signaling pathways, upon acting on different target proteins [40]. Polyphenolic compounds can therefore influence the carcinogenesis process through different mechanisms, making their use appropriate to treat different varieties of cancer. However, main obstacles to effective treatment are given by high metabolic liability, weak membrane permeability, low systemic exposure, physiological fluctuation, and oxidative damage [41].

Antitumor characteristics have been mainly ascribed to their anti-inflammatory, cell cycle arrest, antimetastatic, antiangiogenic, autophagic, antiproliferative, and apoptotic effects [38]. Therefore, cancer prevention and regulation by these bioactive molecules have targeted gene expression, cell cycle proliferation, development, migration, and progression of cells. Furthermore, the cytoprotective and anticancer properties of polyphenolic substances can generally be attributed to their antioxidant attributes [42]. Polyphenols are able to (i) eliminate ROS and other free radicals, (ii) decrease DNA mutation and damage, (iii) suppress cell cycle, (iv) induce apoptosis, (v) down-regulate cell proliferation by means of key signaling pathways modulation (PI3K/Akt, EGFR/MAPK, NF-kB). Moreover, polyphenols may exhibit anticancer effects through other different mechanism pathways, for example, the perforin-granzyme apoptotic pathway, mitochondria-mediated apoptosis by ROS overgeneration, and the death receptor pathway [43]. Furthermore, phenolic compounds can induce regulation of metabolism, cell cycle development, and inhibition of tumor expression via the p53 mechanism pathway. Furthermore, these compounds can stop DNA replication, RNA transcription and repair DNA damage of cancer cells [44].

5. Protective effects of polyphenols from adverse effects of antitumor therapies

Herein, several recent preclinical and clinical studies on the effectiveness of polyphenols in protecting from the adverse effects of anticancer drugs, mainly ROS-mediated toxicity, have been critically analyzed with the aim of evaluating their potential use as supplements in cancer chemotherapy. The pharmacological key findings are summarized in

Table 1.

5.1. Polyphenolic adjuvants in anticancer therapeutic interventions

In a study conducted on MCF-7 cells (human breast cancer), ellagic acid (10) proved to (i) increase cell death, (ii) reduce their capacity to form colonies, and (iii) accumulate cells in the sub-G1 (apoptotic) phase after gamma radiation treatment [45]. The effects were significantly higher in combined treatment compared to ellagic acid or irradiation treatment alone, thereby demonstrating the ability of ellagic acid to radio-sensitize MCF-7 cells. Interestingly, ellagic acid showed radio-protective effects on normal murine cell line in vitro.

Fractions from wine extracts, mainly containing procyanidins, catechins and flavonols, showed antiproliferative effect on PC3 cells (prostate cancer) in a dose-dependent manner [46]. These fractions induced autophagy on the same cell line, thus corroborating the potential in preventing the disease.

In a recent in vitro study [47] ovarian cell lines were treated with oleuropein (phenolic compound present in fruit and leave of olive tree). In particular, the authors showed that after oleuropein treatment of A2780 and A2780 cisplatin resistance cell lines, the expression of p21 and p53 increased, while the expression of Bcl-2 decreased. As a result, oleuropein was able to induce apoptosis, reduce cell proliferation and reduce resistance to cisplatin in ovarian cell lines.

Hydroxytyrosol, the product of oleuropein hydrolysis, is an effective anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant polyphenol. It is able to reduce the nephrotoxicity from cisplatin by inhibiting chemokine-like factor 1 (CKLF1) involved in inflammation pathway as well as by anti-oxidative stress and anti-apoptosis activities in the kidneys of mice [48].

Honey contains a mixture of different active compounds (

Figure 1 and

Figure 5), including coumaric acids (

27-

29), ferulic acid (

15), eugenol (

30), caffeic acid (

14), and flavonoids, (pinocembrin

32, pinobanksin

33, quercetin

5, apigenin

1, chrysin

31, naringin

34), in different percentages depending on the floral source and geographical origins.

Table 1.

Major outcomes from pharmacological studies on the protection activity of polyphenols against toxicity effects of antitumor drugs.

Table 1.

Major outcomes from pharmacological studies on the protection activity of polyphenols against toxicity effects of antitumor drugs.

| |

Source |

Polyphenol/s |

Key findings |

Ref. |

| In vitro models |

Wine extracts |

Ellagic acid |

Pro-apoptotic effect after gamma irradiation on MCF-7 cells |

[45] |

| Procyanidins, catechins, flavonols |

Antiproliferative effect in PC3 prostatic cancer cells |

[46] |

| Olive tree |

Oleuropein |

Apoptosis induction, cell proliferation reduction and resistance to cisplatin reduction on ovarian carcinoma cell lines (A2780) |

[471 |

| Salidroside |

ROS and superoxide reduction in breast cancer lines |

[90] |

| Cell cycle arrest of breast cancer lines |

[91] |

| Animal models |

Honey |

Coumaric acid, ferulic acid, caffeic acid, eugenol, flavonoids |

Prevention of DMBA-induced breast cancer in rats |

[50] |

| Olive tree |

Hydroxytyrosol |

Activation of immune system in mice |

[52] |

| Inhibition of chemokine-like factor 1 (CKLF1), anti-oxidative and anti-apoptosis effects in kidneys of mice during cisplatin treatment |

[48] |

| Ellagic acid |

Attenuation of doxorubicin-related oxidative stress in male Wistar rats |

[76] |

| Gallic acid |

Mortality reduction and heart functional recovery in doxorubicin-treated rats |

[79] |

| Turmeric alcoholic extract |

Curcuminoids |

Doxorubicin-treated male rats mortality reduction and heart weight and heart/body weight increase |

[85] |

| MonoHER |

Protection from doxorubicin cardiotoxicity in mice |

[86] |

| Clinical studies |

Honey |

Coumaric acid, ferulic acid, caffeic acid, eugenol, flavonoids |

Oral mucositis reduction in double-blind clinical trial |

[53] |

| MonoHER |

Doxorubicin activity improvement (partial metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma remission) |

[88] |

| Salidroside |

In co-administration, no significant protection against epirubicin-related cardiotoxicity although well-tolerated |

[93] |

| Aereosol |

Polyphenols |

Minimization of oral side effects in patients after a radiation therapy |

[56] |

| Nutridrink |

Recovering patients undergoing gastrointestinal tumor resection |

[57] |

| MINDS |

Brain protection from toxic side effects of chemotherapy. |

[59] |

| Rich-food |

Reduction of radiotherapy side effects in breast cancer. |

[60] |

Increasing evidence converges in attributing to honey a potential chemopreventive activity [49]. In fact, the multi-floral honey prevented the formation of breast cancer induced by 7,12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene (DMBA) in a rat model [50]. Moreover, increased level of bone marrow lymphocytes and peritoneal macrophages in mice suggested the activation of the immune system [51]. Oral mucositis (OM), which is one of the most common side effects of chemotherapy, could be reduced by honey, thanks to its capacity to increase the immune system response [52]. This effect was confirmed by a double-blind randomized clinical trial in which the patients affected by OM after chemotherapy were treated with betamethasone, honey, and combination of honey and coffee as well [53]. Patients with head and neck cancer treated with radiotherapy showed a reduction of oral side effect (xerostomia) after using of thyme honey [54], as well as manuka honey and talk honey induced a reduction of liver and kidney toxicity induced by cisplatin in rats [55]. The organ-protective effect could be due to free-radical scavenging, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic activity of honey. These data suggest the protective effect of honey and its promising application.

To induce the same protective effect on oral mucosa, a clinical trial (NCT05994638, 2023) [56] is starting to recruit patients receiving a polyphenol-rich aerosol for minimizing side effects in patients after a radiation therapy. In particular, a group of 10 patients with head and neck cancer, who have undergone radiotherapy, will receive an aerosol for oral use constituted of polyphenol-rich plant extracts, hyaluronic acid, cetraria islandica, vitamin B3 for one month.

Another clinical trial (NCT06017661, 2023) [57] is going to use ‘nutridrink’, a preparation of plant extracts rich in polyphenolic compounds as support for recovering patients undergoing gastrointestinal tumor resection.

In a recent Patent (CN111447940; 2020) [58], quercetin and its analogues have been used to provide novel compositions and methods for the treatment of Radiation-Induced Bystander Effects (RIBE) resulting from radiation exposure. Moreover, in a recruiting clinical study (NCT05984888, 2023) [59] some patients affected by breast cancer were treated with MIND (Mediterranean Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay), with the aim of protecting brain from toxic side effects of chemotherapy. MIND is a diet with anti-inflammatory nutrients (e.g., omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), carotenoids, B-vitamins, and polyphenols) which may help alleviate negative cognitive outcomes from cancer treatments. Another clinical trial (NCT02195960, 2023) [60] seeks to evaluate the outcome of polyphenol-rich food supplementation against toxic side effects of breast cancer radiotherapy.

5.2. Activity against ROS-mediated effects of chemotherapeutics

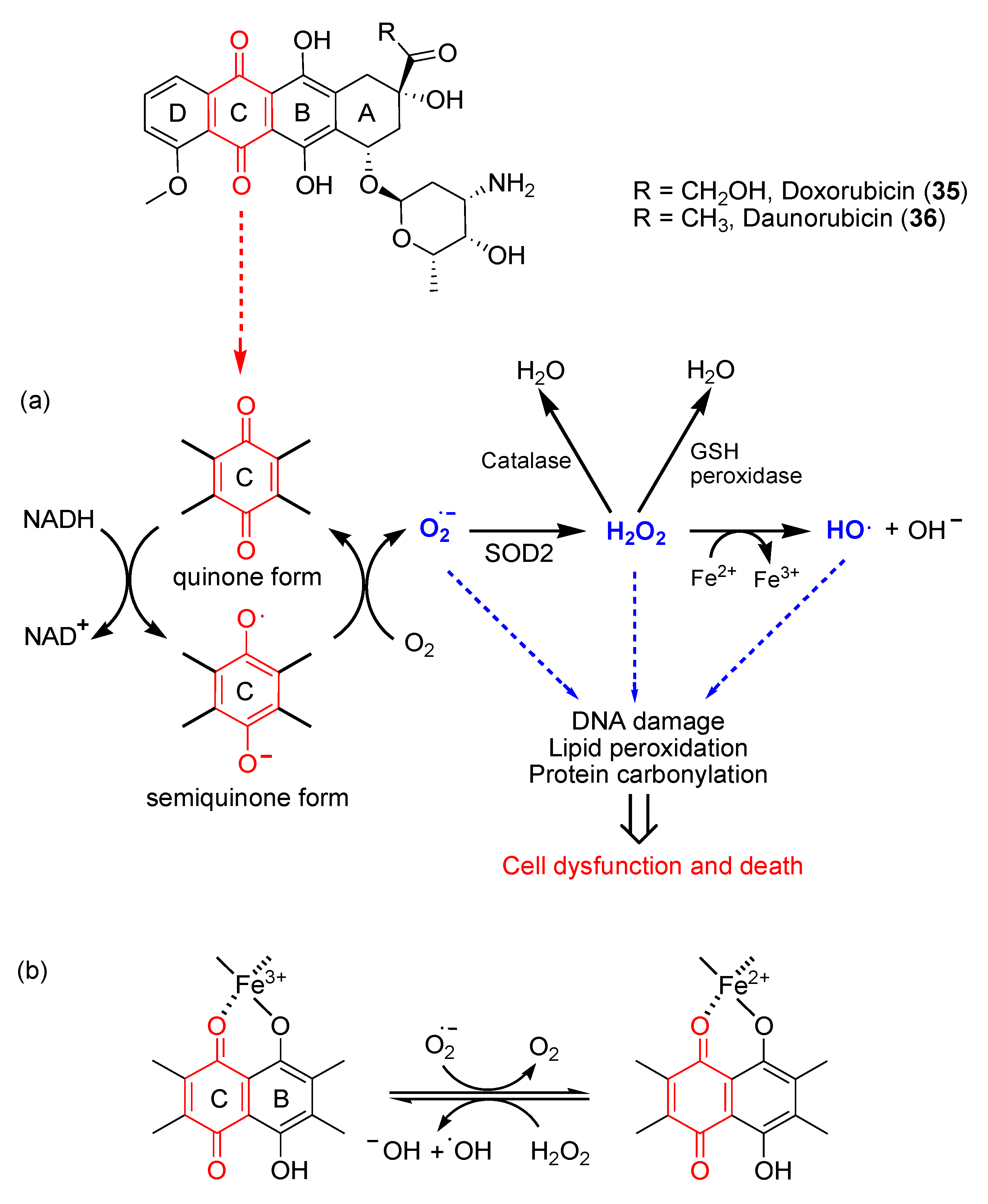

Anthracyclines are anticancer antibiotics characterized by an anthraquinone moiety branched with an amino sugar at C-7. Daunorubicin (

35) and doxorubicin (

36) (

Figure 6), isolated from the bacteria

Streptomyces peucetius, were the earliest drugs of this family that entered clinical practice for cancer treatment [61]. Daunorubicin is effective in acute lymphocytic and myeloid leukemia, while doxorubicin is a component of polypharmacological protocols for treating solid tumors (e.g., breast cancer, soft tissue sarcomas and aggressive lymphomas). Despite being common chemotherapeutics, the clinical use of doxorubicin is limited by dose-dependent cardiac toxicity, which may lead to severe and irreversible forms of cardiomyopathy [62,63]. Indeed, anthracyclines can induce the early onset of progressive chronic cardiotoxicity usually within one year of treatment [64]. The cardiomyopathy may persist or advance even after discontinuation of therapy [65].

The mechanistic explanation for iatrogenic cardiotoxicity lies on the overproduction of ROS. Doxorubicin quinone can be reversibly reduced to semiquinone, an unstable metabolite whose futile redox cycle within mitochondria leads to ROS overload, especially superoxide radical anion O

2∙

-. As shown in

Figure 6, the reduction of doxorubicin quinone (ring C) to semiquinone is catalyzed by NADH-dependent enzymes. The semiquinone in turn donates a single electron to O

2, thereby generating O

2∙

- and recycling itself to quinone. Superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) catalyzes the transformation of O

2∙

- in H

2O

2, which can be detoxified by catalase or glutathione (GSH) peroxidase in the presence of GSH or converted into the highly reactive hydroxyl radical (HO

∙) in the presence of endogenous Fe

2+, through the Fenton reaction.

The highly reactive HO

∙ can in turn generate lipid radicals and other ROS. In addition to ROS, the RNS peroxynitrite (ONOO

-) is generated in cardiomyocytes following doxorubicin administration, most likely due to the reaction between O

2∙

- generated from mitochondria and nitric oxide (NO) [66]. In addition, iron ions (Fe

2+/Fe

3+) have been shown to play a crucial role in this process. Fe

3+ is able to react with hydrogen peroxide to yield reactive hydroperoxyl radicals (HOO∙) and to form chelates with the C11-C12 β-hydroxycarbonyl system of doxorubicin (

Figure 6) [67]. Iron accumulates in cardiomyocytes during doxorubicin treatment, probably because of its capability to interfere with the main iron-transporting and iron-binding proteins [68].

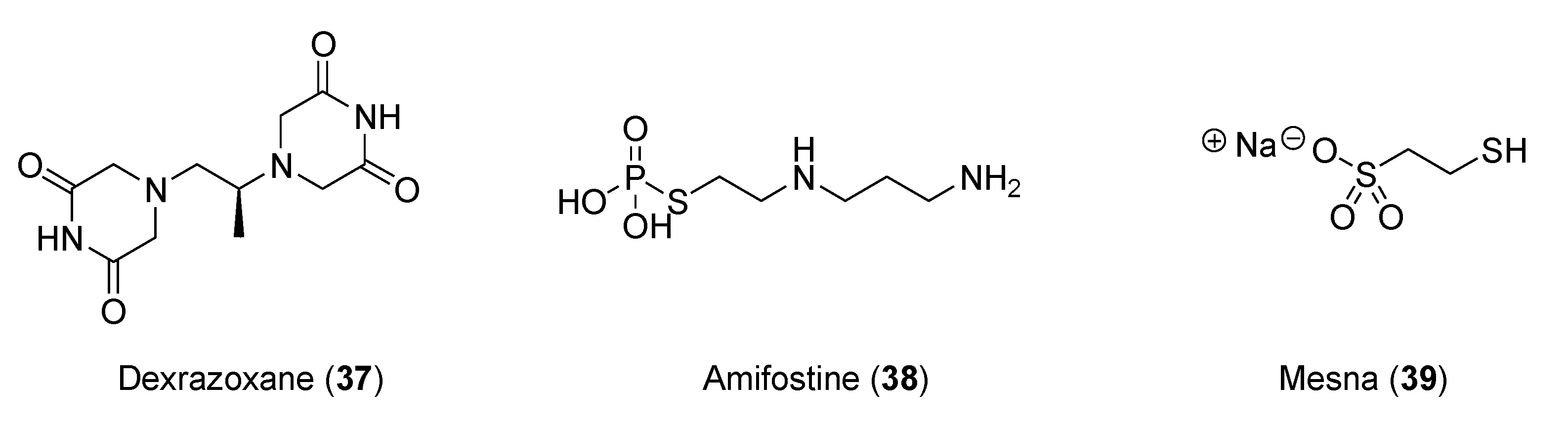

In preclinical and clinical studies of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity, iron chelators, such as dexrazoxane (

37,

Figure 7), showed promise [69]. Other molecules, such as amifostine (

38) and mesna (

39), were also evaluated as cardioprotective auxiliary agents in preclinical studies [70].

5.2.1. Preclinical findings

Ellagic acid (

10,

Figure 1) is a product of hydrolysis of ellagitannins. Recent pharmacological studies demonstrated that

10 acts as a free radical scavenger, with an array of health benefits, such as anti-inflammatory, antihepatotoxic, antisteatosic, anticholestatic, antifibrogenic, antidiabetic, hypolipidemic, and antiatherosclerotic effects [71,72]. Moreover, ellagic acid proved to inhibit type-B monoamine oxidase (MAO-B) [73], thereby protecting rat brain from 6-hydroxydopamine-induced neuroinflammation in a model of Parkinson’s disease [74] and preventing scopolamine- and diazepam-induced cognitive impairments [75]. In male Wistar rats, orally administered

10 proved to attenuate the doxorubicin-induced oxidative process in myocardial tissue [76].

Gallic acid (

13,

Figure 1), a potent free radical scavenger [77], is a product of hydrolysis of gallotannins. Doxorubicin-treated albino rats developed a severe alopecia, and the animal’s fur became scruffy [78]. A 60% mortality rate was observed in doxorubicin group, whereas in animals treated with

13, orally administered at doses of 15 mg/kg and 30 mg/kg, the mortality decreased to 30% and 15%, respectively. Gallic acid showed effectiveness in the heart’s functional recovery, with a significant reduction of cardiac injury, which may be related to its antioxidant properties [79].

Medicinal uses of turmeric (

Curcuma longa L, Zingiberaceae) arise from their contents of volatile oil and curcuminoids (

Figure 1,

18-

20) [80]. It has been reported that turmeric has anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, antiviral and anticancer activities, and it might have neuroprotective effects [81,82]. Recently, the medicinal chemistry of curcumin has been in-depth reviewed and the perspective of new research developments on curcuminoids widely discussed [83]. Extensive investigation over the past quarter century, including over hundred clinical studies of curcuminoids against several diseases, addressed pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of turmeric [84].

The administration of single dose of doxorubicin to a group of male rats was compared with the group receiving doxorubicin and an alcoholic extract of C. longa L via oral gavage. Compared to controls, doxorubicin-treated animals showed 50% increase of mortality. In rats co-treated with turmeric extracts, not only mortality significantly diminished, but also heart weight and heart-to-body weight ratio significantly increased. Turmeric proved to protect animals against acute doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity, ameliorating cardiac enzymes, modulating the pathways triggering cardiac apoptosis, decreased levels of GSH and overproduction of oxidant radicals [85].

5.2.2. Evaluation of clinical studies

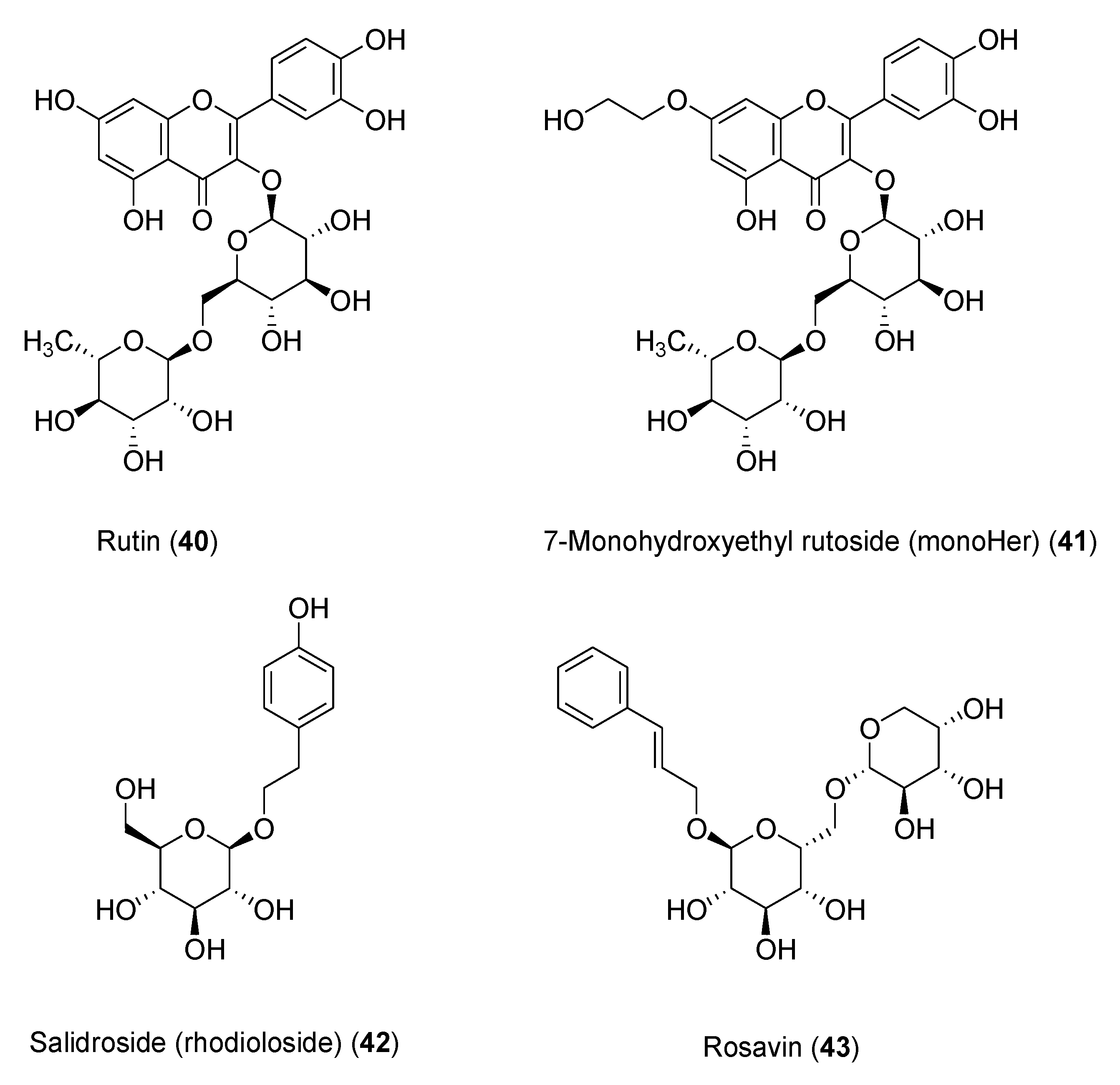

The flavonoid 7-mono-

O-(β-hydroxyethyl)rutoside (monoHER) (

41,

Figure 8), a semi-synthetic derivative of rutin (

40), bearing rutinose (α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-

d-glucopyranose) as disaccharide moiety, has been shown to protect mice against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity without adverse effects at very high dose (500 mg/kg) [86]. Based on these results, clinical trials were performed to evaluate its protective effects in cancer patients. MonoHER, administered intravenously at 1500 mg/m

2 dose 60 min before every doxorubicin administration, was evaluated through endomyocardial biopsy, but the benefits observed in the preclinical studies were not confirmed [87]. These conflicting results might be attributed to interspecies ADMET differences. However, the antitumor activity of doxorubicin appeared to greatly improve, even displaying partial remission of metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma in some patients, these results being somehow in agreement with the potentiating anti-proliferative effects observed in vitro for a number of flavonoids [88].

Another noteworthy clinically investigated polyphenol is salidroside (i.e., tyrosol glucoside,

42) found in

Rhodiola rosea used in traditional Tibetan medicine. Salidroside (

Figure 8), along with less active rosavin

43 (a cinnamyl alcohol glycoside bearing α-

l-arabinopyranosyl-α-

d-glucopyranoside as disaccharide moiety), was reported to play a role in reducing mitochondrial-generated ROS and apoptosis signaling [89]. Pretreatment with salidroside appears to significantly reduce in vitro both ROS and mitochondrial superoxide overproduction [90], and to arrest cell cycle and apoptosis in human breast cancer cells [91].

Furthermore, 42 showed antioxidant-related cardiovascular protection [92]. These results encouraged clinical studies to assess its effectiveness in protecting against cardiac dysfunctions induced by epirubicin in sixty patients with histologically confirmed breast cancer. In this trial, all patients attained the scheduled cumulative epirubicin dose of 400 mg/m2. Although the oral co-administration of 42 and epirubicin was well tolerated in all patients, no significant differences in protection from epirubicin-induced cardiotoxic effects were found compared to the placebo groups, once again suggesting that most likely poor bioavailability of the polyphenolic phytochemicals in humans may be a major factor limiting clinical application [93].

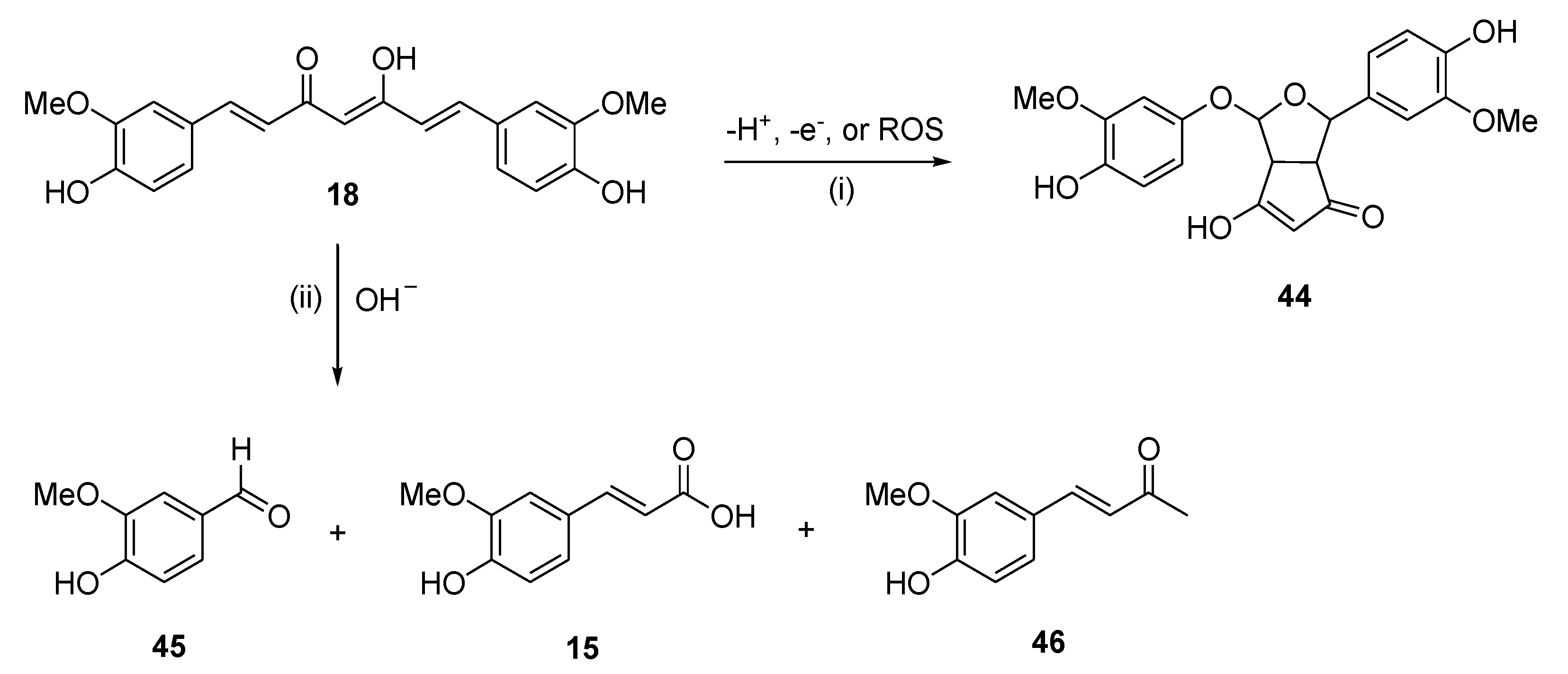

A main hurdle to the therapeutic application of polyphenols is their poor bioavailability, resulting from poor absorption, low chemical and metabolic stability and systemic elimination, as shown in applications either in CNS diseases [41] or in cancer prevention and therapy [94]. For example, numerous studies proved that curcumin (

18) is chemically and metabolically unstable, and thereby poorly bioavailable [83]. Spectroscopic analysis revealed that a major degradation product (

44) is formed by autoxidation of

18 [95], whereas three minor degradation products, namely ferulic acid (

15), vanillin (

45) and the ketone product

46, are generated by solvolysis reaction in aqueous alkaline buffer [96] (

Figure 9). Pharmaceutical nanotechnologies may implement efficient delivery systems aimed at improving the bioavailability of polyphenols [97].

5.3. Bioavailability increase through nanoformulations of polyphenols

A major advantage of the particles within a range of less than 100 nm (nanoparticles) is represented by the high surface area to volume ratio [98]. In general, nanoformulations (liposomes, micelles, natural and synthetic nanoparticles, metal nanoparticles and microspheres) may lead to improved bioavailability, biodistribution, specificity, and optimal pharmacokinetics of drugs delivered to the tumor sites [99–101]. Some examples of optimized nanoformulations of plant-derived polyphenols are reported below.

The effects of polyphenolic extracts from green tea (GTE), red wine (RW) lees and/or lemon (L) peel, alone and in combination with antitumor drugs, were investigated on the growth and development of different transplanted experimental tumors [102]. Nanosized forms of these extracts (NanoGTE, NanoGTRW or NanoGTRWL) were produced by spray drying technology (10-45 nm particle size). The total phenolic composition for the extracts ranged from 18.0 to 21.3 g/100 g for each formulation. The antitumor properties of polyphenolic extracts and biocomposites were tested in murine-transplanted tumors, namely sarcoma 180, solid Ehrlich carcinoma, Ca755 mammary carcinoma, B16 melanoma. Reduction indices of doxorubicin cardiotoxicity and cisplatin nephrotoxicity suggest beneficial effects of polyphenols in green tea, red wine lees and lemon peels as nanoextracts. This study suggested the promising development of GTE and nanoextracts as auxiliary agents in anticancer treatment.

Luteolin (

3,

Figure 1), one of the flavonoids of celery, green pepper, honey and chamomile tea, showed inhibitory effects toward the transcription factor Nrf2 [103]. The exposure to carcinogenic molecules activates the Nrf2 pathway inducing the elimination of carcinogenic reactive intermediates and consequently resistance to chemotherapeutic agents. Luteolin could sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapeutic agents through inhibition of Nfr2. Luteolin-phytosome proved to be a potential drug delivery system able to increase the efficacy of doxorubicin in human MDA-MB 321 breast cancer cells [104]. The real time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis showed that phyto-Luteolin suppressed the mRNA expression of Nfr2, as well as the expression of genes of HO-1 and MDR-1 more than luteolin alone in human MDA-MB 321 breast cancer cells [105]. The cytotoxicity data showed that nanoformulations were able to inhibit the growth of MDA-MB231 cells better than luteolin or doxorubicin alone.

Another study explored the synergistic effect of resveratrol (

17,

Figure 1) and 5-fluorouracil using PEGylated liposomes. This nanoformulation was tested in vitro on head and neck cancer cell line (NT8e). Data showed a cytotoxicity increase of nanoformulations (liposomes) compared to the free drug [106].

The poor ADMET properties of curcumin (18) could be overcome through nanoformulations, as recently shown by several studies. Different nanocarriers were employed, ranging from polymeric or solid-lipid nanoparticles to nanocrystals, nano-emulsions, and nano liposome-encapsulated curcumin, just to mention the most important applications [107,108]. Limited to anticancer treatment, curcumin loaded N-dodecyl-chitosan-HPTMA-coated liposomes showed increased sensitivity of mouse melanoma cell line B16F10. These tumor cells can tolerate 18 at a concentration of about 10 µM, while the cytotoxicity of chitosan-based formulation can be observed at lower concentrations (2.5 µM) [109]. Actually, a number of studies demonstrated that nanoparticle-encapsulation of 18 is not always beneficial. For example, curcumin-loaded chitosan/polycaprolactone nanoparticles exhibited cytotoxicity on cervical cancer and choroidal melanoma (HeLa and OCM-1 cell lines, respectively) to the same extent as free curcumin [110]. Furthermore, mPEG 2000-curcumin conjugates were equipotent with unbound curcumin against a panel of carcinoma cell lines [111].

The biodistribution and efficacy of different curcumin nanoformulations were investigated in many in vivo studies in order to assess the therapeutic potential of these release systems [109]. Curcumin-loaded MPEG-PCL polymeric micelles showed a stronger antiproliferative effect in mice LL/2 pulmonary carcinoma compared to free curcumin [112]. Finally, curcumin nanoformulations were investigated in human clinical trials for many years, showing clinical benefits for patients with some solid tumors and multiple myeloma. The effects and concentrations in normal and cancerous tissues, after administration of curcumin formulations, were compared; safety and immune responses were taken, in each study, as the primary and secondary outcomes, respectively [109].

6. Conclusions and perspectives

Literature provides a wealth of information about numerous health-related properties, including anticarcinogenic activity, of plant-derived polyphenols. Pharmacological data support several mechanisms for the activity of flavonoids in inhibiting cancer onset and progression. Polyphenols could play significant roles in protecting from adverse effects of anticancer chemotherapeutics, especially those related to drug-induced oxidative stress. Herein, both preclinical and clinical findings regarding the effectiveness of polyphenols, or their synthetic analogs and derivatives, were reviewed with a focus on their capacity to protect against ROS-mediated toxic effects induced by antitumor chemotherapeutics. The only clinically tested flavonoid glycoside monoHer (41) showed protective activity against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in mice, but the effect was not confirmed in human studies. Salidroside (42), which induces cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in human breast cancer cells, albeit tolerated in all patients, did not show significant protective effects against anthracycline-related cardiotoxic effects. This apparent dichotomy could be explained considering several factors, such as species-related differences in metabolism and bioavailability, and issues related to dosing. Studies aimed at establishing adequate dosing and delivery systems are needed, whereas a promising research area is dedicated to the development of nanoformulations as bioavailability booster of polyphenolic phytochemicals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P., L.P. and C.D.A.; methodology, R.P., A.B. and L.P.; validation, M.C., M.d.C. and C.D.A.; investigation, R.P., A.B. and L.P.; data curation, M.C. and C.D.A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.P., A.B. and L.P.; writing—review and editing, C.D.A.; funding acquisition, C.D.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

R.P.: A.B., M.C. and C.D.A. acknowledge the financial support of the Italian Ministry of Education, Universities and Research (PRIN, Grant 201744BNST_004). L.P. acknowledges the financial support of the Italian Ministry of Education, Universities and Research (PRIN, Grant 2017RPHBCW_002). R.P. acknowledges financial support from Apulian Region “Research for Innovation (REFIN)” - POR PUGLIA FESR-FSE 2014/2020 (Project F88A1A13).

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflict of interest.”.

References

- Kondratyuk, T.P.; Pezzuto, J.M. Natural Product Polyphenols of Relevance to Human Health. Pharm.Biol. 2004, 42, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, R. Chemistry and Biochemistry of Dietary Polyphenols. Nutrients 2010, 2, 1231–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beecher, G.R. Overview of Dietary Flavonoids: Nomenclature, Occurrence and Intake. J Nutr 2003, 133, 3248S–3254S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, S.; Alves, M.G.; Sousa, M.; Oliveira, P.F.; Silva, B.M. Are Polyphenols Strong Dietary Agents Against Neurotoxicity and Neurodegeneration? Neurotox Res 2016, 30, 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- hurana, S.; Venkataraman, K.; Hollingsworth, A.; Piche, M.; Tai, T. Polyphenols: Benefits to the Cardiovascular System in Health and in Aging. Nutrients 2013, 5, 3779–3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotecha, R.; Takami, A.; Espinoza, J.L. Dietary Phytochemicals and Cancer Chemoprevention: A Review of the Clinical Evidence. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 52517–52529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaccio, M.; Pounis, G.; Cerletti, C.; Donati, M.B.; Iacoviello, L.; De Gaetano, G.; on behalf of the MOLI-SANI Study Investigators. Mediterranean Diet, Dietary Polyphenols and Low Grade Inflammation: Results from the MOLI-SANI Study: Mediterranean Diet, Polyphenols and Low Grade Inflammation. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2017, 83, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valls-Pedret, C.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; Medina-Remón, A.; Quintana, M.; Corella, D.; Pintó, X.; Martínez-González, M.Á.; Estruch, R.; Ros, E. Polyphenol-Rich Foods in the Mediterranean Diet Are Associated with Better Cognitive Function in Elderly Subjects at High Cardiovascular Risk. JAD 2012, 29, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrae-Marobela, K.; Ghislain, F.W.; Okatch, H.; Majinda, R.R.T. Polyphenols: A Diverse Class of Multi-Target Anti-HIV-1 Agents. CDM 2013, 14, 392–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumazawa, Y.; Takimoto, H.; Matsumoto, T.; Kawaguchi, K. Potential Use of Dietary Natural Products, Especially Polyphenols, for Improving Type-1 Allergic Symptoms. CPD 2014, 20, 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhakumar, A.B.; Bulmer, A.C.; Singh, I. A Review of the Mechanisms and Effectiveness of Dietary Polyphenols in Reducing Oxidative Stress and Thrombotic Risk. J Hum Nutr Diet 2014, 27, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghezzi, P.; Jaquet, V.; Marcucci, F.; Schmidt, H.H.H.W. The Oxidative Stress Theory of Disease: Levels of Evidence and Epistemological Aspects: The Oxidative Stress Theory of Disease. Br. J.Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1784–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braakhuis, A.; Campion, P.; Bishop, K. Reducing Breast Cancer Recurrence: The Role of Dietary Polyphenolics. Nutrients 2016, 8, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donno, D.; Mellano, M.; Cerutti, A.; Beccaro, G. Biomolecules and Natural Medicine Preparations: Analysis of New Sources of Bioactive Compounds from Ribes and Rubus Spp. Buds. Pharm. 2016, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Xu, B.-T.; Xu, X.-R.; Gan, R.-Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, E.-Q.; Li, H.-B. Antioxidant Capacities and Total Phenolic Contents of 62 Fruits. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.-N.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Xu, X.-R.; Chen, Y.-M.; Li, H.-B. Resources and Biological Activities of Natural Polyphenols. Nutrients 2014, 6, 6020–6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicoli, M.C.; Anese, M.; Parpinel, M. Antioxidant Properties of Fruit and Vegetables. 1999.

- Nicoli, M.C.; Anese, M.; Parpinel, M.T.; Franceschi, S.; Lerici, C.R. Loss and/or Formation of Antioxidants during Food Processing and Storage. Cancer Lett. 1997, 114, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimonte, S.; Barbieri, A.; Leongito, M.; Piccirillo, M.; Giudice, A.; Pivonello, C.; De Angelis, C.; Granata, V.; Palaia, R.; Izzo, F. Curcumin AntiCancer Studies in Pancreatic Cancer. Nutrients 2016, 8, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.R.; Scott, E.; Brown, V.A.; Gescher, A.J.; Steward, W.P.; Brown, K. Clinical Trials of Resveratrol: Clinical Trials. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1215, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili-Baleh, L.; Babaei, E.; Abdpour, S.; Nasir Abbas Bukhari, S.; Foroumadi, A.; Ramazani, A.; Sharifzadeh, M.; Abdollahi, M.; Khoobi, M. A Review on Flavonoid-Based Scaffolds as Multi-Target-Directed Ligands (MTDLs) for Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 152, 570–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.; Lee, G.; Ritter, A.; Zhong, K. Alzheimer’s Disease Drug Development Pipeline: 2018. TRCI 2018, 4, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Study Details | Study of STA-1 as an Add-on Treatment to Donepezil | ClinicalTrials.Gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT01255046 (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Chang, T.-T.; Huang, C.-C.; Hsu, C.-H. Clinical Evaluation of the Chinese Herbal Medicine Formula STA-1 in the Treatment of Allergic Asthma. Phytother. Res. 2006, 20, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cellamare, S.; Stefanachi, A.; Stolfa, D.A.; Basile, T.; Catto, M.; Campagna, F.; Sotelo, E.; Acquafredda, P.; Carotti, A. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Glycine-Based Molecular Tongs as Inhibitors of Aβ1–40 Aggregation in Vitro. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 4810–4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellicani, R.Z.; Stefanachi, A.; Niso, M.; Carotti, A.; Leonetti, F.; Nicolotti, O.; Perrone, R.; Berardi, F.; Cellamare, S.; Colabufo, N.A. Potent Galloyl-Based Selective Modulators Targeting Multidrug Resistance Associated Protein 1 and P-Glycoprotein. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 424–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardia, P.; Stefanachi, A.; Niso, M.; Stolfa, D.A.; Mangiatordi, G.F.; Alberga, D.; Nicolotti, O.; Lattanzi, G.; Carotti, A.; Leonetti, F.; et al. Trimethoxybenzanilide-Based P-Glycoprotein Modulators: An Interesting Case of Lipophilicity Tuning by Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 6403–6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leo, V.; Stefanachi, A.; Nacci, C.; Leonetti, F.; De Candia, M.; Carotti, A.; Altomare, C.D.; Montagnani, M.; Cellamare, S. Galloyl Benzamide-Based Compounds Modulating Tumour Necrosis Factor α-Stimulated c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase and P38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signalling Pathways. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2015, 67, 1380–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, A.N.; Ross, E.K.; Khatter, S.; Miller, K.; Linseman, D.A. Chemical Basis for the Disparate Neuroprotective Effects of the Anthocyanins, Callistephin and Kuromanin, against Nitrosative Stress. Free Radic. Bio. Med. 2017, 103, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.H.; Dar, K.B.; Anees, S.; Zargar, M.A.; Masood, A.; Sofi, M.A.; Ganie, S.A. Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Neurodegenerative Diseases; a Mechanistic Insight. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2015, 74, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imlay, J.A. Cellular Defenses against Superoxide and Hydrogen Peroxide. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008, 77, 755–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eghbaliferiz, S.; Iranshahi, M. Prooxidant Activity of Polyphenols, Flavonoids, Anthocyanins and Carotenoids: Updated Review of Mechanisms and Catalyzing Metals: Prooxidant Activity of Polyphenols and Carotenoids. Phytother. Res. 2016, 30, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, K.E.; Tagliaferro, A.R.; Bobilya, D.J. Flavonoid Antioxidants: Chemistry, Metabolism and Structure-Activity Relationships. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2002, 13, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolová, R.; Ramešová, Š.; Degano, I.; Hromadová, M.; Gál, M.; Žabka, J. The Oxidation of Natural Flavonoid Quercetin. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Sakata, T.; Palumbo, J.; Akimoto, M. A 24-Week, Phase III, Double-Blind, Parallel-Group Study of Edaravone (MCI-186) for Treatment of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) (P3.189). Neurology 2016, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuaib, A.; Lees, K.R.; Lyden, P.; Grotta, J.; Davalos, A.; Davis, S.M.; Diener, H.-C.; Ashwood, T.; Wasiewski, W.W.; Emeribe, U. NXY-059 for the Treatment of Acute Ischemic Stroke. N Engl J Med 2007, 357, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, U.; Fichna, J.; Gorlach, S. Enhancement of Anticancer Potential of Polyphenols by Covalent Modifications. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016, 109, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Pradhan, B.; Nayak, R.; Behera, C.; Das, S.; Patra, S.K.; Efferth, T.; Jena, M.; Bhutia, S.K. Dietary Polyphenols in Chemoprevention and Synergistic Effect in Cancer: Clinical Evidences and Molecular Mechanisms of Action. Phytomedicine 2021, 90, 153554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Li, S.; Wang, C.; Cao, N.; Qu, H.; Cheng, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhou, L. Potential Applications of Polyphenols on Main ncRNAs Regulations as Novel Therapeutic Strategy for Cancer. Biomed Pharmacother 2019, 113, 108703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symonds, E.L.; Konczak, I.; Fenech, M. The Australian Fruit Illawarra Plum (Podocarpus Elatus Endl., Podocarpaceae) Inhibits Telomerase, Increases Histone Deacetylase Activity and Decreases Proliferation of Colon Cancer Cells. Br J Nutr 2013, 109, 2117–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandareesh, M.D.; Mythri, R.B.; Srinivas Bharath, M.M. Bioavailability of Dietary Polyphenols: Factors Contributing to Their Clinical Application in CNS Diseases. Neurochem. Int. 2015, 89, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amawi, H.; Ashby, C.R.; Samuel, T.; Peraman, R.; Tiwari, A.K. Polyphenolic Nutrients in Cancer Chemoprevention and Metastasis: Role of the Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal (EMT) Pathway. Nutrients 2017, 9, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhosale, P.B.; Ha, S.E.; Vetrivel, P.; Kim, H.H.; Kim, S.M.; Kim, G.S. Functions of Polyphenols and Its Anticancer Properties in Biomedical Research: A Narrative Review. Transl Cancer Res 2020, 9, 7619–7631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majidinia, M.; Bishayee, A.; Yousefi, B. Polyphenols: Major Regulators of Key Components of DNA Damage Response in Cancer. DNA Repair (Amst) 2019, 82, 102679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahire, V.; Kumar, A.; Mishra, K.P.; Kulkarni, G. Ellagic Acid Enhances Apoptotic Sensitivity of Breast Cancer Cells to γ-Radiation. Nutr. Cancer 2017, 69, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenta, R.; Fragopoulou, E.; Tsoukala, M.; Xanthopoulou, M.; Skyrianou, M.; Pratsinis, H.; Kletsas, D. Antiproliferative Effects of Red and White Wine Extracts in PC-3 Prostate Cancer Cells. Nutr. Cancer 2017, 69, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemi Sheikhshabani, S.; Amini-Farsani, Z.; Rahmati, S.; Jazaeri, A.; Mohammadi-Samani, M.; Asgharzade, S. Oleuropein Reduces Cisplatin Resistance in Ovarian Cancer by Targeting Apoptotic Pathway Regulators. Life Sci. 2021, 278, 119525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Ai, Q.; Wei, Y. Hydroxytyrosol Protects against Cisplatin-Induced Nephrotoxicity via Attenuating CKLF1 Mediated Inflammation, and Inhibiting Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 96, 107805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badolato, M.; Carullo, G.; Cione, E.; Aiello, F.; Caroleo, M.C. From the Hive: Honey, a Novel Weapon against Cancer. European J. Med. Chem. 2017, 142, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takruri, H.R.; Shomaf, M.S.; Shnaigat, S.F. Multi Floral Honey Has a Protective Effect against Mammary Cancer Induced by 7,12-Dimethylbenz(a)Anthracene in Sprague Dawley Rats. JAS 2017, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, W.Y.; Gabry, M.S.; El-Shaikh, K.A.; Othman, G.A. The Anti-Tumor Effect of Bee Honey in Ehrlich Ascite Tumor Model of Mice is Coincided with Stimulation of the Immune Cells. EJI 2008, 15, 169–183. [Google Scholar]

- Lalla, R.V.; Brennan, M.; Schubert, M.; Yagiela, J.A.; Dowd, F.J.; Mariotti, A.; Neidle, E.A. Pharmacol. Therap. Dentistry - E-Book; Oral complications of cancer therapy; Elsevier Health Sciences, 2010; Vol. 50. ISBN 978-0-323-07824-5.

- Raeessi, M.A.; Raeessi, N.; Panahi, Y.; Gharaie, H.; Davoudi, S.M.; Saadat, A.; Karimi Zarchi, A.A.; Raeessi, F.; Ahmadi, S.M.; Jalalian, H. “Coffee plus Honey” versus “Topical Steroid” in the Treatment of Chemotherapy-Induced Oral Mucositis: A Randomised Controlled Trial. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014, 14, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalambous, A.; Lambrinou, E.; Katodritis, N.; Vomvas, D.; Raftopoulos, V.; Georgiou, M.; Paikousis, L.; Charalambous, M. The Effectiveness of Thyme Honey for the Management of Treatment-Induced Xerostomia in Head and Neck Cancer Patients: A Feasibility Randomized Control Trial. Eur. J. Oncol. Nur 2017, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neamatallah, T.; El-Shitany, N.A.; Abbas, A.T.; Ali, S.S.; Eid, B.G. Honey Protects against Cisplatin-Induced Hepatic and Renal Toxicity through Inhibition of NF-κB-Mediated COX-2 Expression and the Oxidative Stress Dependent BAX/Bcl-2/Caspase-3 Apoptotic Pathway. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 3743–3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Study Details | Polyphenol Rich Aerosol as a Support for Cancer Patients in Minimizing Side Effects After a Radiation Therapy - NCT05994638| ClinicalTrials.Gov; 2023.

-

Study Details | Investigation of a Polyphenol-Rich Preparation as Support for Oncology Patients Undergoing Gastrointestinal Tumor Resection - NCT06017661 | ClinicalTrials.Gov; 2023.

- Xue, D.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, L.; Liang, Q.; Li, H.; Yu, J.S.; Chen, J.T. Compositions and Methods for Preventing and Treating Radiation-Induced Bystander Effects Caused by Radiation or Radio- Therapy - CN111447940; 2020.

-

Study Details | Pilot Study of a MIND Diet Intervention in Women Undergoing Active Treatment for Breast Cancer - NCT05984888| ClinicalTrials.Gov; 2023.

-

Study Details | Supplementation With Dietary Anthocyanins and Side Effects of Radiotherapy for Breast Cancer - NCT02195960| ClinicalTrials.Gov; 2023.

- Fujiwara, A.; Hoshino, T.; Westley, J.W. Anthracycline Antibiotics. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 1985, 3, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.-A.; Sandhu, N.; Herrmann, J. Systems Biology Approaches to Adverse Drug Effects: The Example of Cardio-Oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2015, 12, 718–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardinale, D.; Colombo, A.; Bacchiani, G.; Tedeschi, I.; Meroni, C.A.; Veglia, F.; Civelli, M.; Lamantia, G.; Colombo, N.; Curigliano, G.; et al. Early Detection of Anthracycline Cardiotoxicity and Improvement With Heart Failure Therapy. Circulation 2015, 131, 1981–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkova, M.; Russell, R. Anthracycline Cardiotoxicity: Prevalence, Pathogenesis and Treatment. CCR 2012, 7, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vejpongsa, P.; Yeh, E.T.H. Prevention of Anthracycline-Induced Cardiotoxicity. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 938–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jungsuadee, P. Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyopathy: An Update beyond Oxidative Stress and Myocardial Cell Death. Cardiovasc Regen Med 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichikawa, Y.; Ghanefar, M.; Bayeva, M.; Wu, R.; Khechaduri, A.; Prasad, S.V.N.; Mutharasan, R.K.; Naik, T.J.; Ardehali, H. Cardiotoxicity of Doxorubicin Is Mediated through Mitochondrial Iron Accumulation. J. Clin. Invest. 2014, 124, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammella, E.; Maccarinelli, F.; Buratti, P.; Recalcati, S.; Cairo, G. The Role of Iron in Anthracycline Cardiotoxicity. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, M.K.; Gerdes, S.; West, A.; Richter, S.; Busemann, C.; Hentschel, L.; Lenz, F.; Kopp, H.-G.; Ehninger, G.; Reichardt, P.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Dexrazoxane (DRZ) in Sarcoma Patients Receiving High Cumulative Doses of Anthracycline Therapy – a Retrospective Study Including 32 Patients. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehenbauer Ludke, A.R.; Al-Shudiefat, A.A.-R.S.; Dhingra, S.; Jassal, D.S.; Singal, P.K. A Concise Description of Cardioprotective Strategies in Doxorubicin-Induced cardiotoxicityThis Article Is One of a Selection of Papers Published in a Special Issue Celebrating the 125th Anniversary of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Manitoba. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2009, 87, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, M.R. The Effects of Ellagic Acid upon Brain Cells: A Mechanistic View and Future Directions. Neurochem Res 2016, 41, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larrosa, M.; García-Conesa, M.T.; Espín, J.C.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Ellagitannins, Ellagic Acid and Vascular Health. Mol. Aspects Med. 2010, 31, 513–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatri, D.; Juvekar, A. Kinetics of Inhibition of Monoamine Oxidase Using Curcumin and Ellagic Acid. Phcog Mag 2016, 12, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farbood, Y.; Sarkaki, A.; Dolatshahi, M.; Mansouri, S.M.T.; Khodadadi, A. Ellagic Acid Protects the Brain Against 6-Hydroxydopamine Induced Neuroinflammation in a Rat Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Basic.Clinic. Neurosci. 2015, Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri, M.T.; Farbood, Y.; Naghizadeh, B.; Shabani, S.; Mirshekar, M.A.; Sarkaki, A. Beneficial Effects of Ellagic Acid against Animal Models of Scopolamine- and Diazepam-Induced Cognitive Impairments. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 54, 1947–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warpe, V.S.; Mali, V.R.; Arulmozhi, S.; Bodhankar, S.L.; Mahadik, K.R. Cardioprotective Effect of Ellagic Acid on Doxorubicin Induced Cardiotoxicity in Wistar Rats. JACME 2015, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choubey, S.; Varughese, L.R.; Kumar, V.; Beniwal, V. Medicinal Importance of Gallic Acid and Its Ester Derivatives: A Patent Review. Pharm. Pat. Anal. 2015, 4, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daglia, M.; Lorenzo, A.; Nabavi, S.; Talas, Z.; Nabavi, S. Polyphenols: Well Beyond The Antioxidant Capacity: Gallic Acid and Related Compounds as Neuroprotective Agents: You Are What You Eat! CPB 2014, 15, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, J.; Swamy, A.H.M.V. Cardioprotective Effect of Gallic Acid against Doxorubicin-Induced Myocardial Toxicity in Albino Rats. Indian J Health Sci Biomed Res 2015, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothitirat, W.; Gritsanapan, W. Variation of Bioactive Components in Curcuma Longa in Thailand. CURRENT SCIENCE 2006, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, G.; Mittal, S.; Sak, K.; Tuli, H.S. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Chemopreventive Potential of Curcumin: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Life Sci. 2016, 148, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Bordoloi, D.; Padmavathi, G.; Monisha, J.; Roy, N.K.; Prasad, S.; Aggarwal, B.B. Curcumin, the Golden Nutraceutical: Multitargeting for Multiple Chronic Diseases: Curcumin: From Kitchen to Clinic. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1325–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, K.M.; Dahlin, J.L.; Bisson, J.; Graham, J.; Pauli, G.F.; Walters, M.A. The Essential Medicinal Chemistry of Curcumin: Miniperspective. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 1620–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.C.; Patchva, S.; Aggarwal, B.B. Therapeutic Roles of Curcumin: Lessons Learned from Clinical Trials. AAPS J 2013, 15, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, E.M.; El-azeem, A.S.A.; Afify, A.A.; Shabana, M.H.; Ahmed, H.H. Cardioprotective Effects of Curcuma Longa L. Extracts against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Rats.

- Van Acker, F.A.A.; Van Acker, S.A.B.E.; Krammer, K.; haenen, G.R.M.M.; Bast, A.; Van Der Vijgh, w. J.F. 7-Monohydroxyethylrutoside Protects against Chronic Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity When Administered Only Once per Week. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000, 6, 1337–1341. [Google Scholar]

- Bruynzeel, A.M.E.; Niessen, H.W.M.; Bronzwaer, J.G.F.; Van Der Hoeven, J.J.M.; Berkhof, J.; Bast, A.; Van Der Vijgh, W.J.F.; Van Groeningen, C.J. The Effect of Monohydroxyethylrutoside on Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Patients Treated for Metastatic Cancer in a Phase II Study. Br J Cancer 2007, 97, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-W.; Hu, J.-J.; Fu, R.-Q.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.-H.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.-N.; Deng, Q.; Luo, Q.-S.; et al. Flavonoids Inhibit Cell Proliferation and Induce Apoptosis and Autophagy through Downregulation of PI3Kγ Mediated PI3K/AKT/mTOR/p70S6K/ULK Signaling Pathway in Human Breast Cancer Cells. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 11255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Xin, H.; Wu, L.-X.; Zhu, Y.-Z. Salidroside Attenuates Apoptosis in Ischemic Cardiomyocytes: A Mechanism Through a Mitochondria-Dependent Pathway. J Pharmacol Sci 2010, 114, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schriner, S.E.; Abrahamyan, A.; Avanessian, A.; Bussel, I.; Maler, S.; Gazarian, M.; Holmbeck, M.A.; Jafari, M. Decreased Mitochondrial Superoxide Levels and Enhanced Protection against Paraquat in Drosophila Melanogaster Supplemented with Rhodiola Rosea. Free Radical Research 2009, 43, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, S.; Yu, D.; Lin, S. Salidroside Induces Cell-Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis in Human Breast Cancer Cells. BBRC 2010, 398, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Zhou, H.; Jin, Z.; Bi, S.; Yang, X.; Yi, D.; Liu, W. Cardioprotection of Salidroside from Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury by Increasing N-Acetylglucosamine Linkage to Cellular Proteins. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 613, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Shen, W.; Gao, C.; Deng, L.; Shen, D. Protective Effects of Salidroside on Epirubicin-Induced Early Left Ventricular Regional Systolic Dysfunction in Patients with Breast Cancer. Drugs R D 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, I.A.; Sanna, V.; Ahmad, N.; Sechi, M.; Mukhtar, H. Resveratrol Nanoformulation for Cancer Prevention and Therapy: Resveratrol Nanoformulations for Cancer. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1348, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griesser, M.; Pistis, V.; Suzuki, T.; Tejera, N.; Pratt, D.A.; Schneider, C. Autoxidative and Cyclooxygenase-2 Catalyzed Transformation of the Dietary Chemopreventive Agent Curcumin. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 1114–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, O.N.; Schneider, C. Vanillin and Ferulic Acid: Not the Major Degradation Products of Curcumin. Trends Mol. Med. 2012, 18, 361–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanna, V.; Lubinu, G.; Madau, P.; Pala, N.; Nurra, S.; Mariani, A.; Sechi, M. Polymeric Nanoparticles Encapsulating White Tea Extract for Nutraceutical Application. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 2026–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagavarma, B.V.N.; Hemant, K.S.Y.; Ayaz, A.; Vasudha, L.S.; Shivakumar, H.G. different techniques for preparation of polymeric nanoparticles. AJPCR 2012, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Bohn, T. Dietary Factors Affecting Polyphenol Bioavailability. Nutr Rev 2014, 72, 429–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, Y.; Hamaguchi, T.; Ura, T.; Muro, K.; Yamada, Y.; Shimada, Y.; Shirao, K.; Okusaka, T.; Ueno, H.; Ikeda, M.; et al. Phase I Clinical Trial and Pharmacokinetic Evaluation of NK911, a Micelle-Encapsulated Doxorubicin. Br J Cancer 2004, 91, 1775–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Huang, Q. Bioavailability and Delivery of Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods Using Nanotechnology. In Bio-Nanotech.; Bagchi, D., Bagchi, M., Moriyama, H., Shahidi, F., Eds.; Wiley, 2013; pp. 593–604 ISBN 978-0-470-67037-8.

- Zaletok, S.; Gulua, L.; Wicker, L.; Shlyakhovenko, V.O.; Gogo, S.; Orlovsky, O.; Karnaushenko, O.; Verbinenko, A.; Milinevska, V.; Samoylenko, O.; et al. Green tea, red wine and lemon extracts reduce experimental tumor growth and cancer drug toxicity. Exp. Onc. 2015, 37, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.T. Mechanism of Metastasis Suppression by Luteolin in Breast Cancer. BCTT 2018, 10, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabzichi, M.; Hamishehkar, H.; Ramezani, F.; Sharifi, S.; Tabasinezhad, M.; Pirouzpanah, M.; Ghanbari, P.; Samadi, N. Luteolin-Loaded Phytosomes Sensitize Human Breast Carcinoma MDA-MB 231 Cells to Doxorubicin by Suppressing Nrf2 Mediated Signalling. APJCP 2014, 15, 5311–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, P.; Sadanandam; Manthena, S. Phytosomes in Herbal Drug Delivery. J Nat Pharm 2010, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A.; Narayanan, S.; Sethuraman, S.; Krishnan, U.M. Novel Resveratrol and 5-Fluorouracil Coencapsulated in PEGylated Nanoliposomes Improve Chemotherapeutic Efficacy of Combination against Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. BioMed Research Int. 2014, 2014, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gera, M.; Sharma, N.; Ghosh, M.; Huynh, D.L.; Lee, S.J.; Min, T.; Kwon, T.; Jeong, D.K. Nanoformulations of Curcumin: An Emerging Paradigm for Improved Remedial Application. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 66680–66698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yallapu, M.M.; Nagesh, P.K.B.; Jaggi, M.; Chauhan, S.C. Therapeutic Applications of Curcumin Nanoformulations. AAPS J 2015, 17, 1341–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karewicz, A.; Bielska, D.; Loboda, A.; Gzyl-Malcher, B.; Bednar, J.; Jozkowicz, A.; Dulak, J.; Nowakowska, M. Curcumin-Containing Liposomes Stabilized by Thin Layers of Chitosan Derivatives. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces 2013, 109, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, D.; Wang, S.; Deng, Z.; Lou, W.; Xu, H.; Bai, Q.; Ma, J. Preparation and Characterization of Cationic Curcumin Nanoparticles for Improvement of Cellular Uptake. Carbohyd. Polym. 2012, 90, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichitnithad, W.; Nimmannit, U.; Callery, P.S.; Rojsitthisak, P. Effects of Different Carboxylic Ester Spacers on Chemical Stability, Release Characteristics, and Anticancer Activity of Mono-PEGylated Curcumin Conjugates. J. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 100, 5206–5218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, C.; Deng, S.; Wu, Q.; Xiang, M.; Wei, X.; Li, L.; Gao, X.; Wang, B.; Sun, L.; Chen, Y.; et al. Improving Antiangiogenesis and Anti-Tumor Activity of Curcumin by Biodegradable Polymeric Micelles. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 1413–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).