Submitted:

30 November 2023

Posted:

01 December 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Wood & Wire Rope

2.2. Dimensional and Mechanical Characteristics of Wooden Members and Cables

2.3. PV Racking Design Parameters

2.4. Main Design

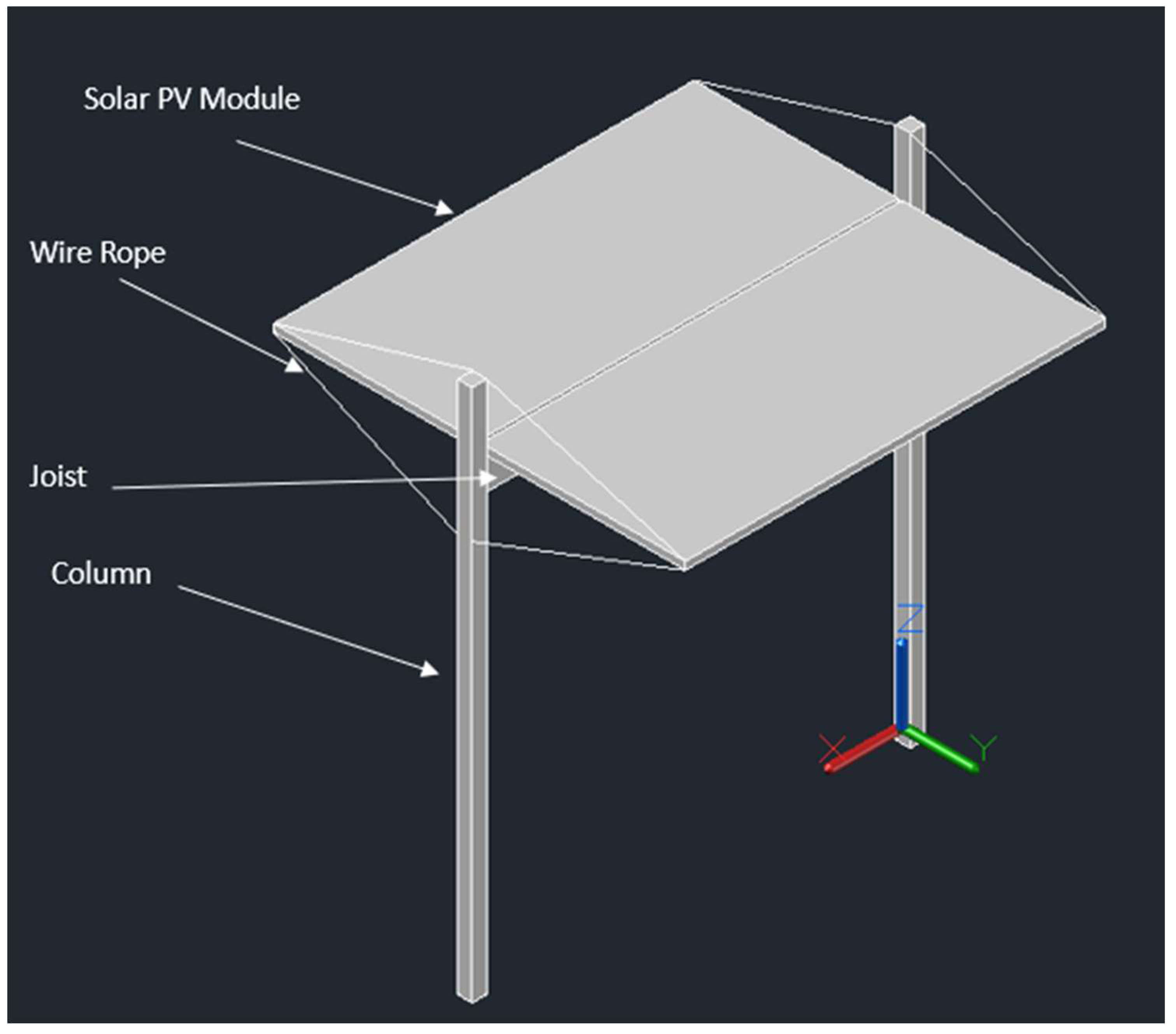

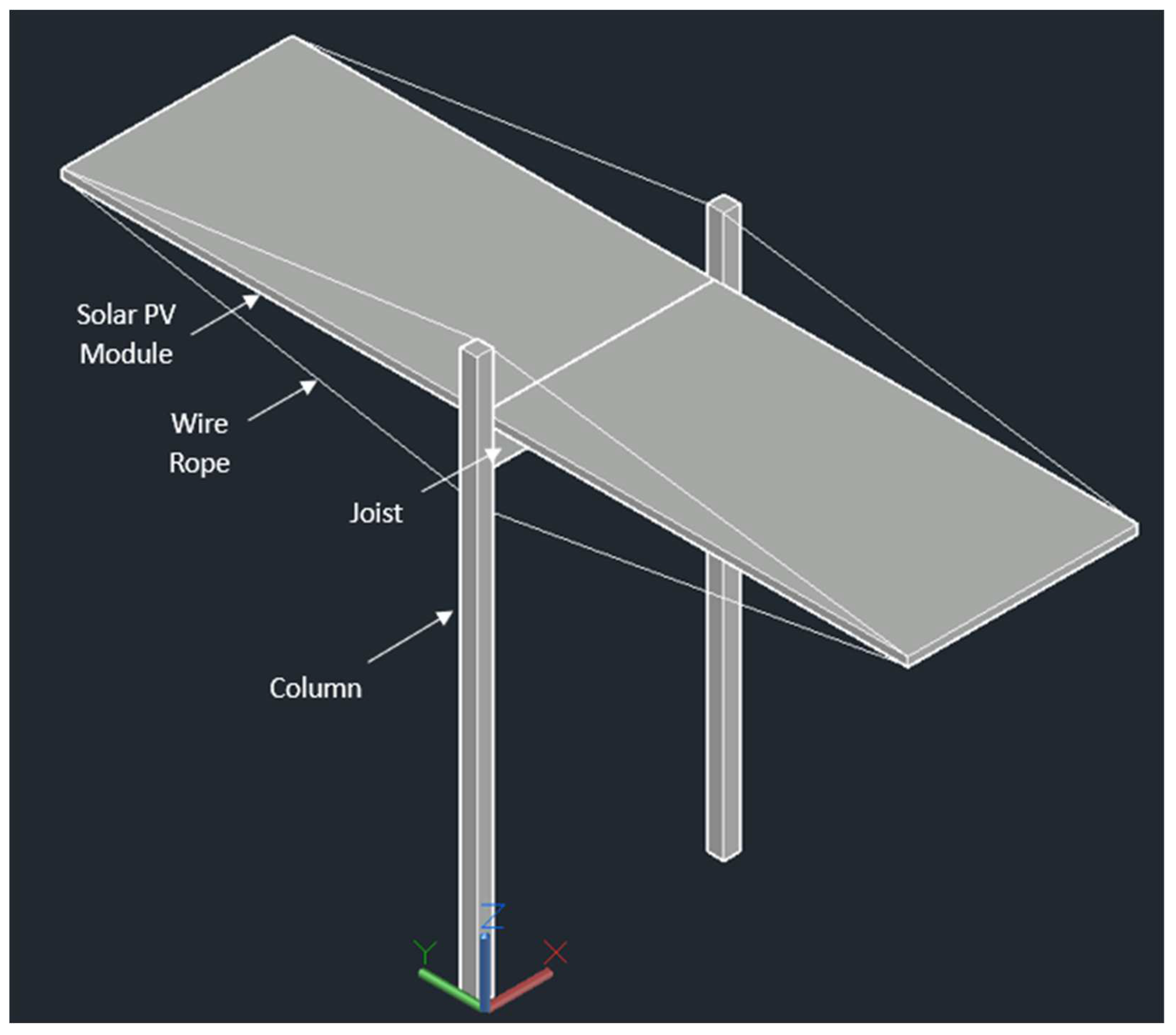

2.4.1. T-Shaped Wood & Cable Design

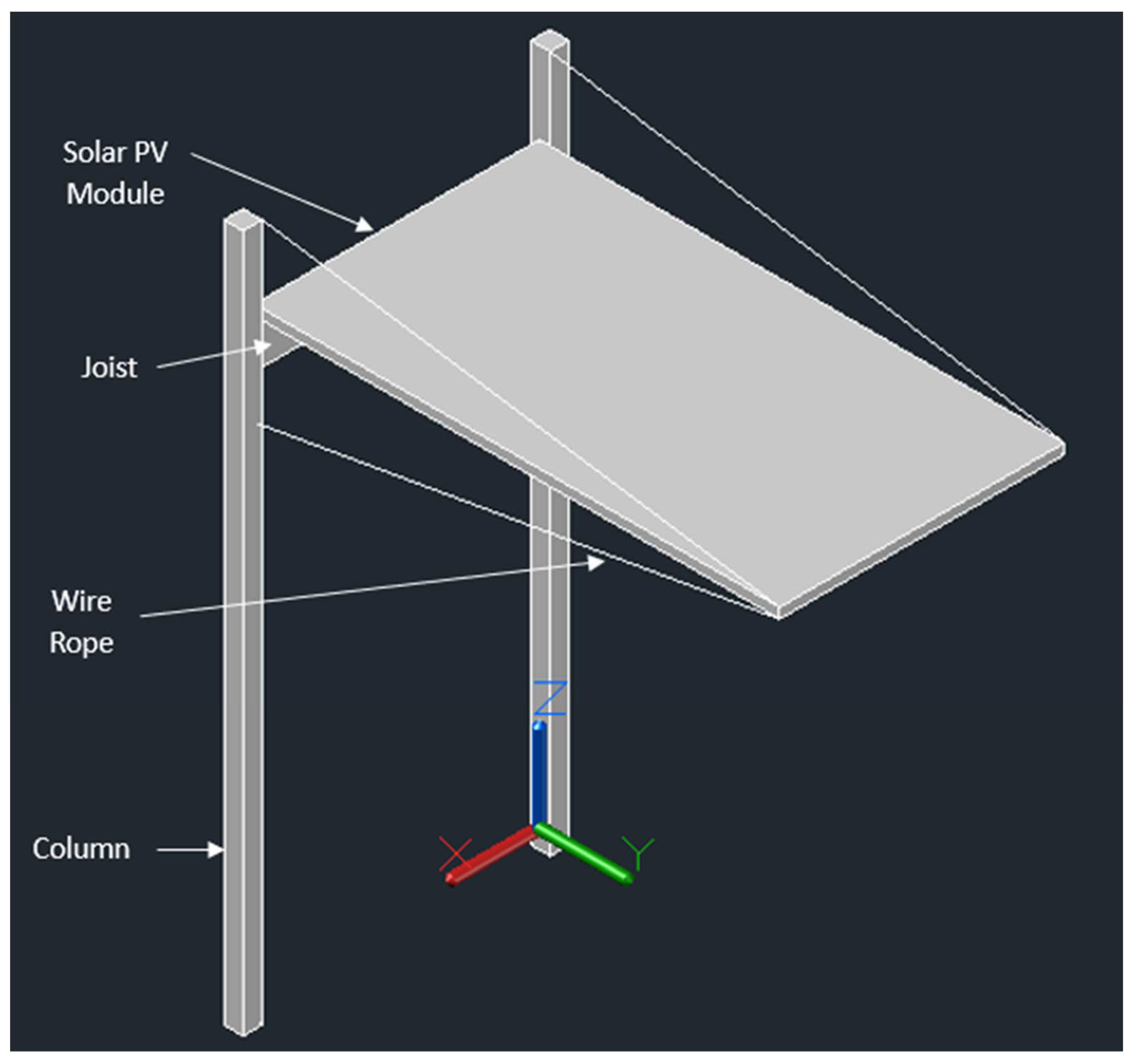

2.4.2. Cantilevered Carport Wood & Cable Design

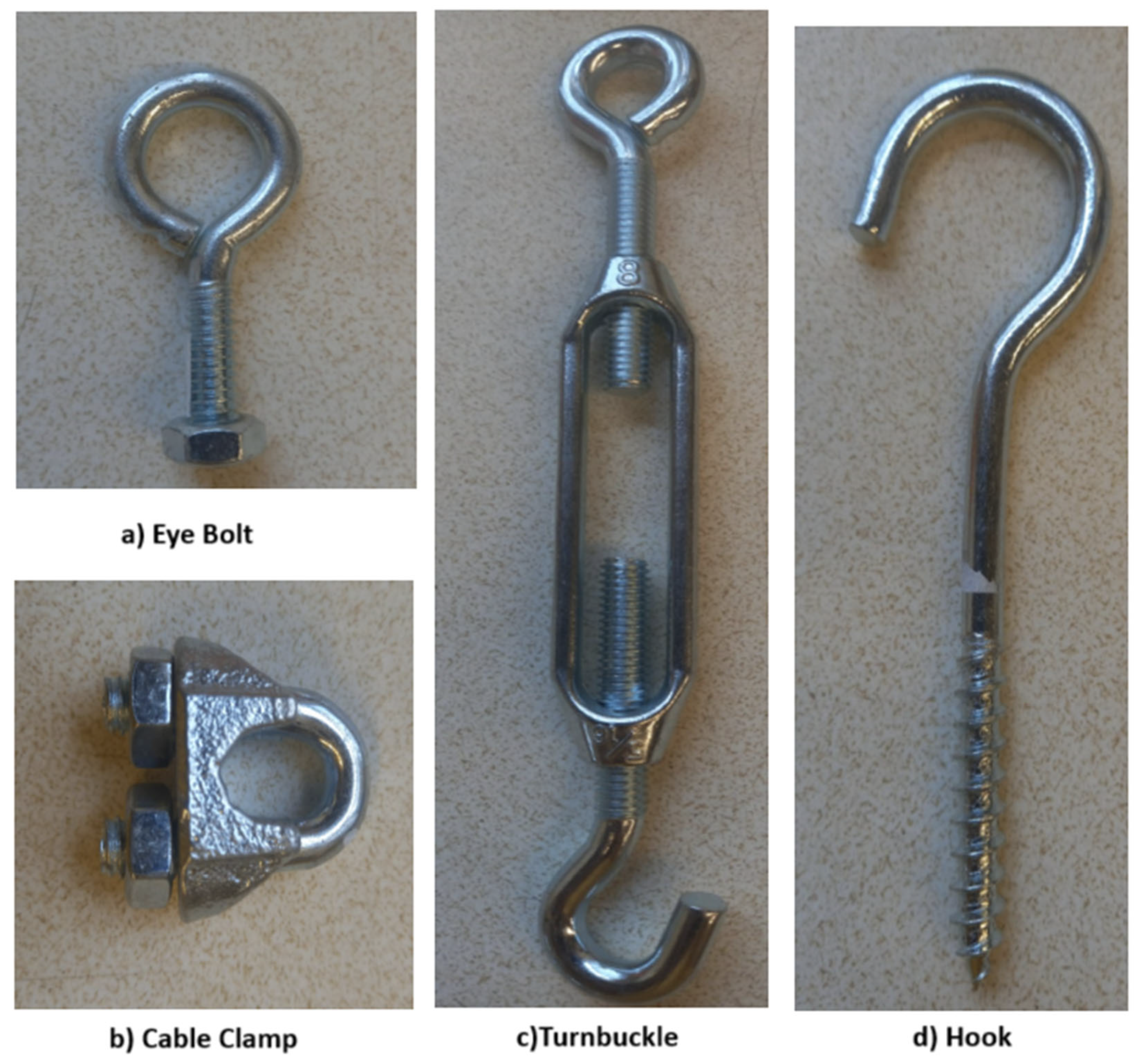

2.5. Bill of Materials (BOM)

2.6. Load Calculations

2.7. PV System Simulations

2.8. Variables

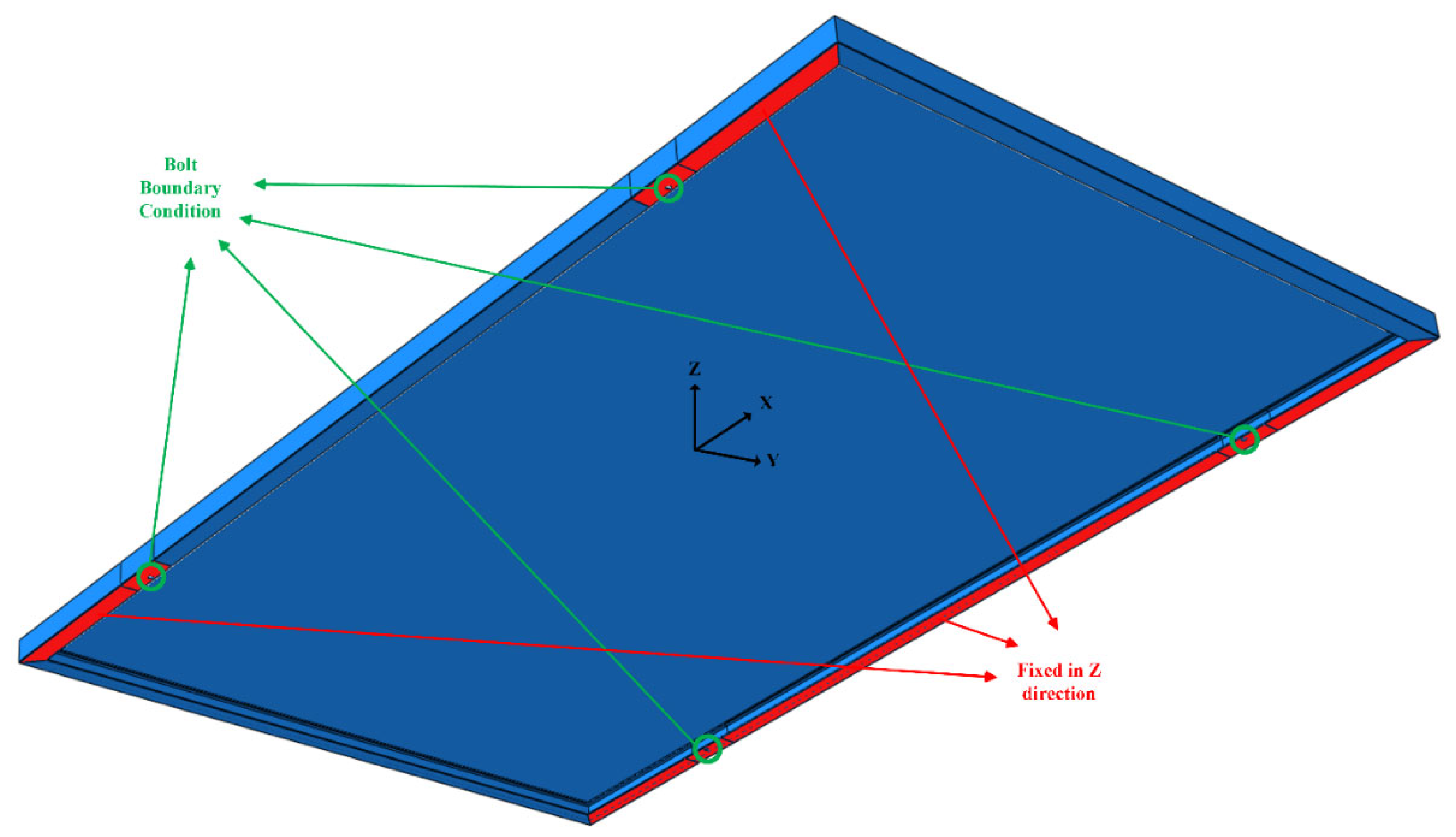

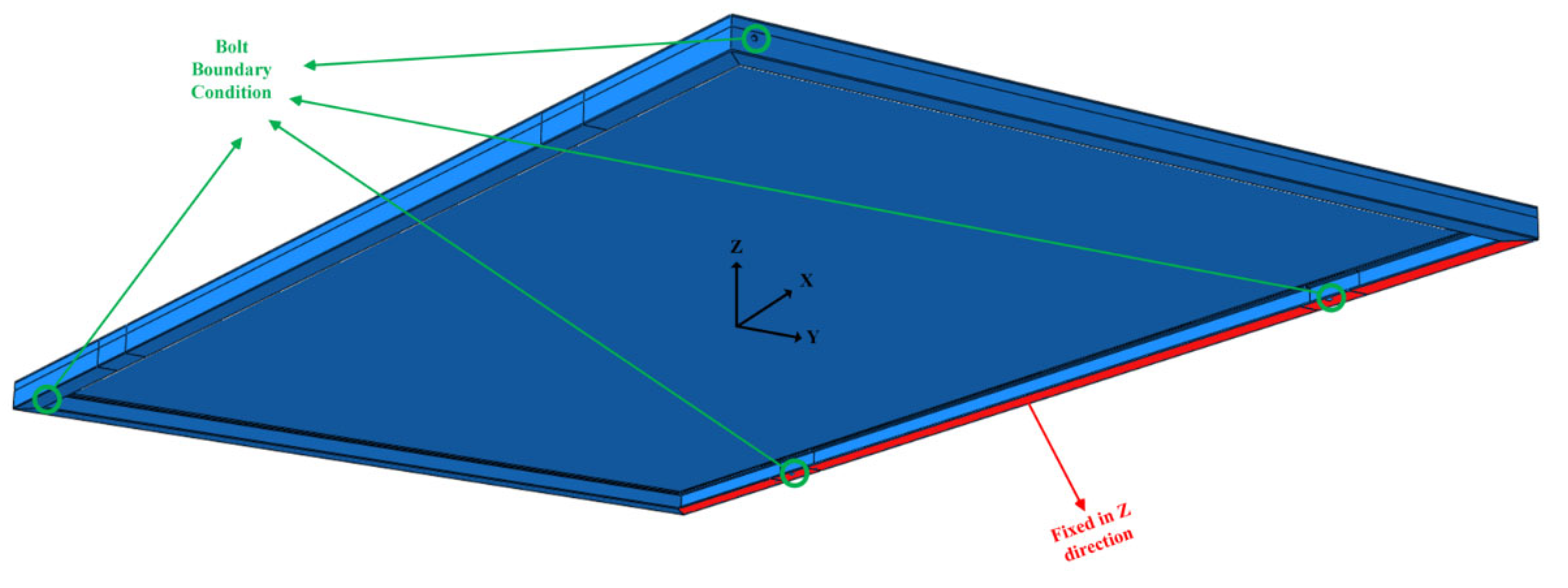

2.9. Finite Element Analysis (FEA)

3. Results

3.1. Loads

3.1.1. Snow Loads

3.1.2. Wind Loads

3.1.3. Dead Load

3.1.4. Load Combination

3.2. Wooden Members Structural Capacity

3.3. Structural Analysis

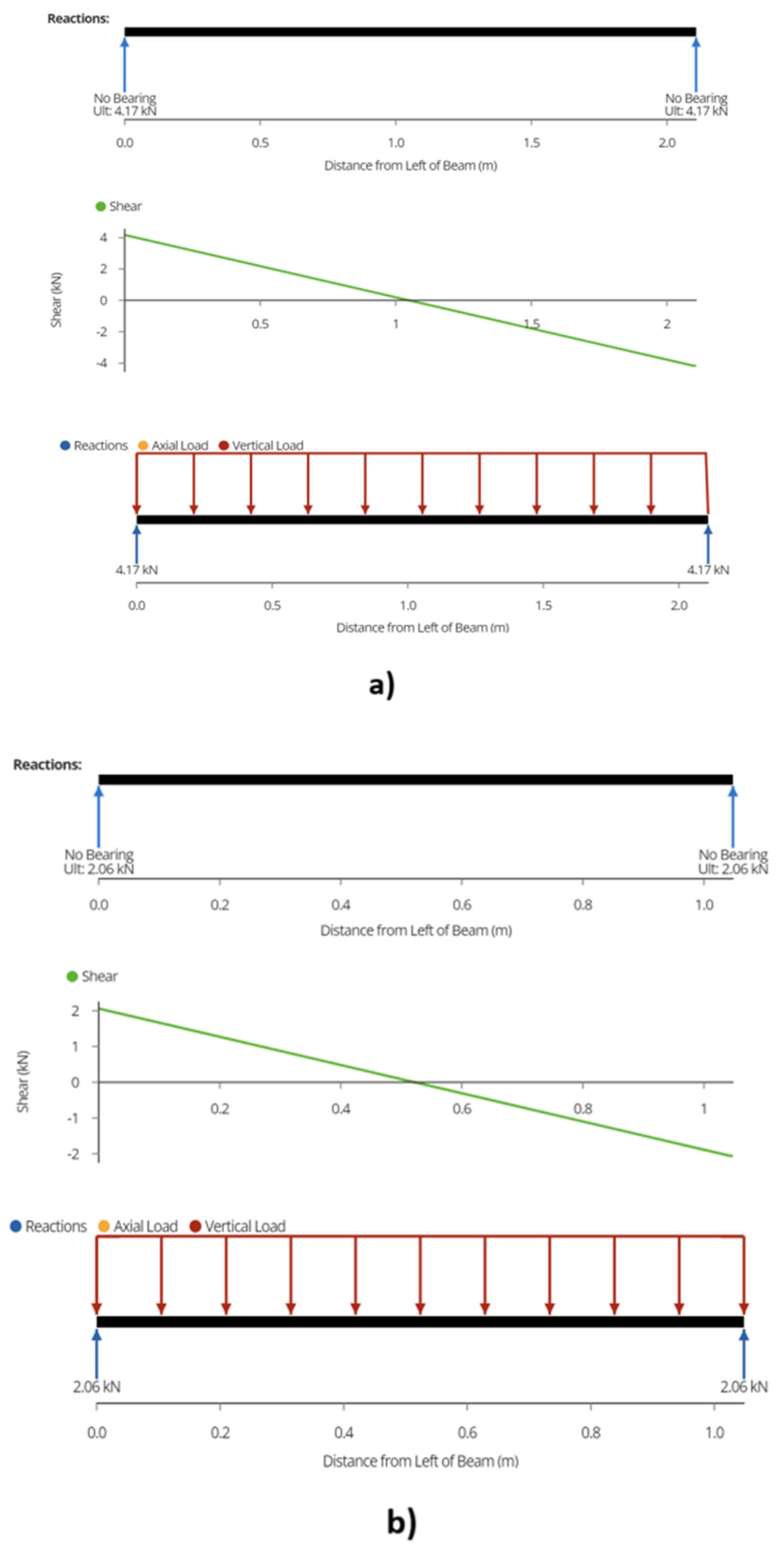

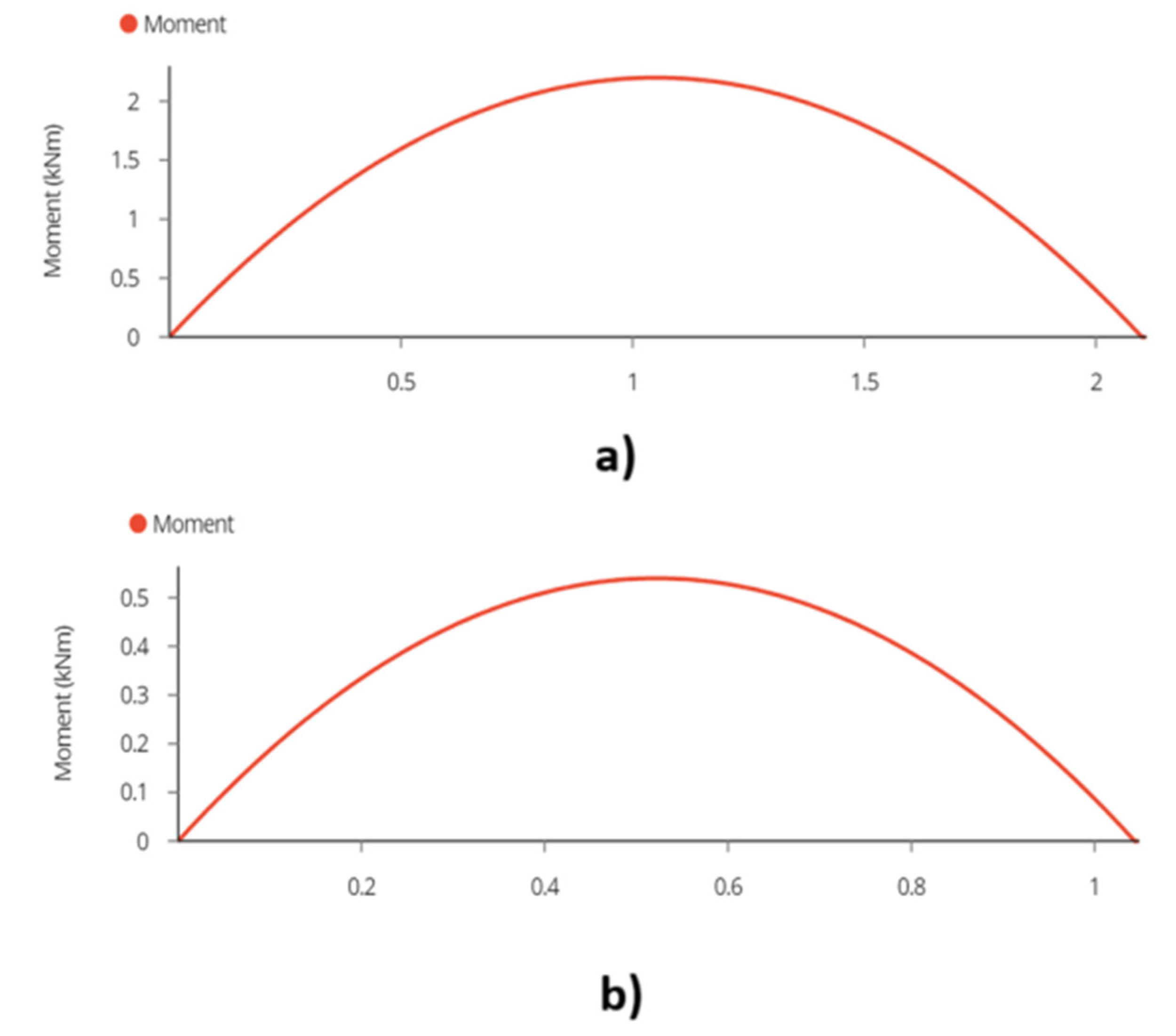

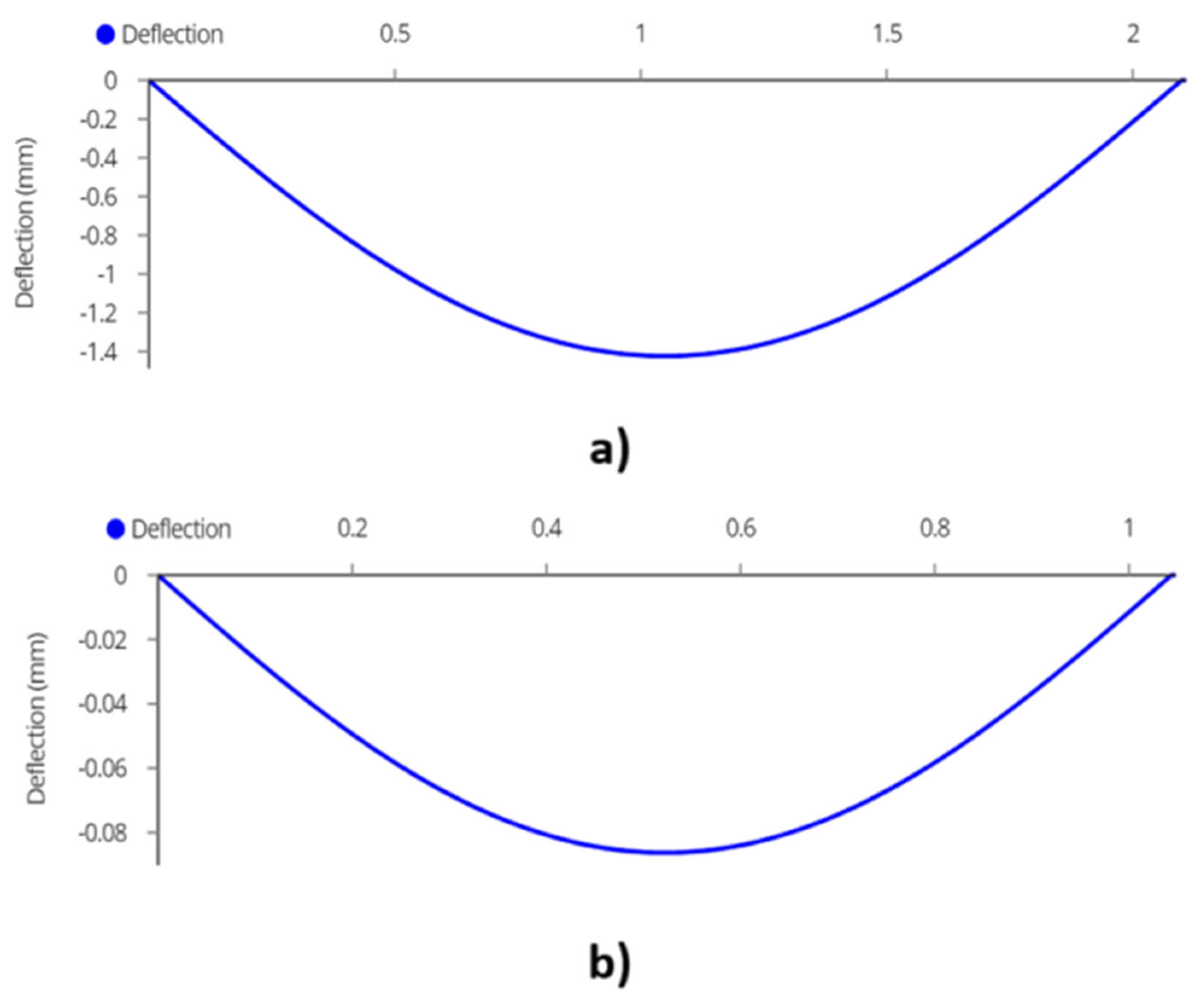

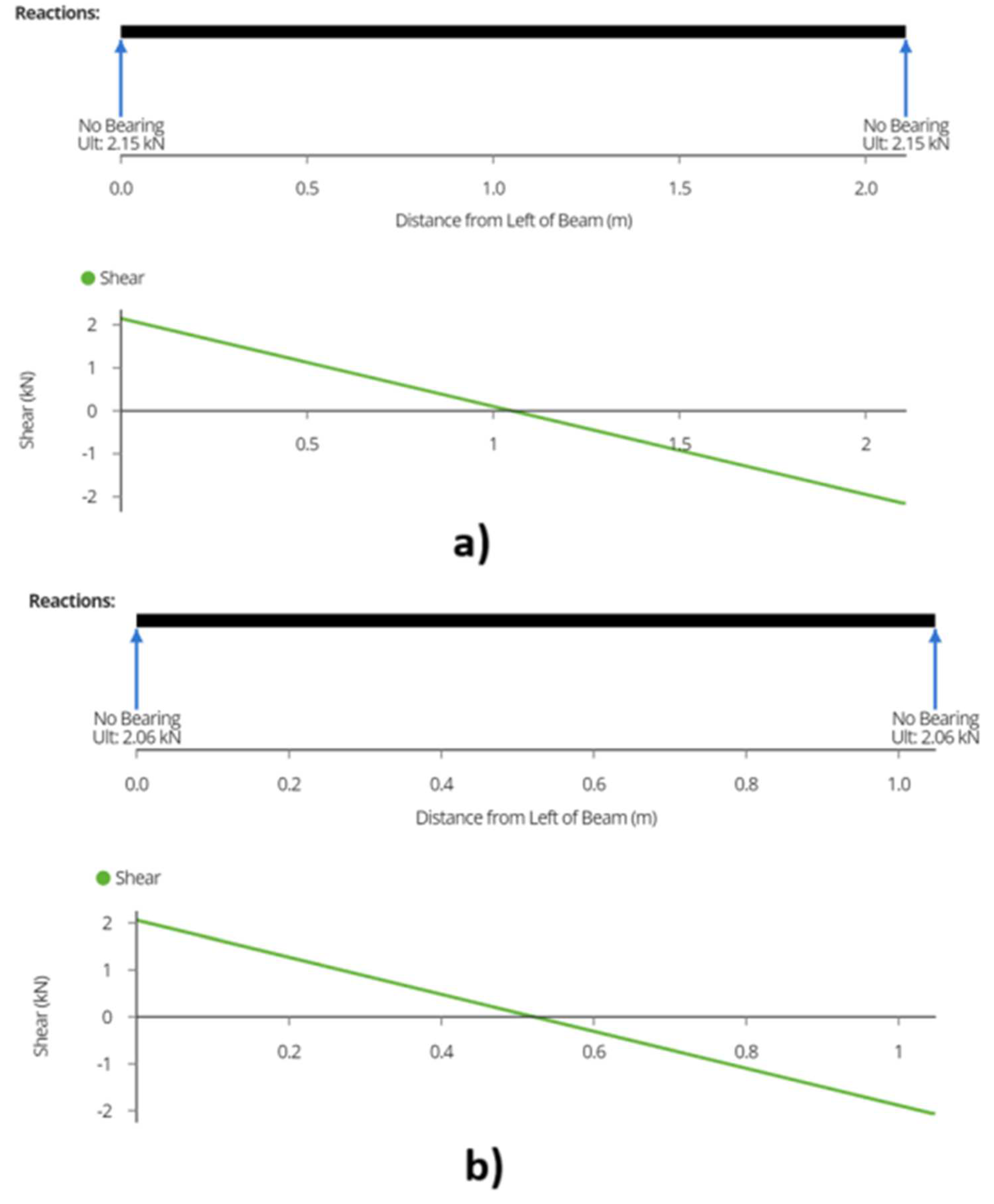

3.3.1. Joist

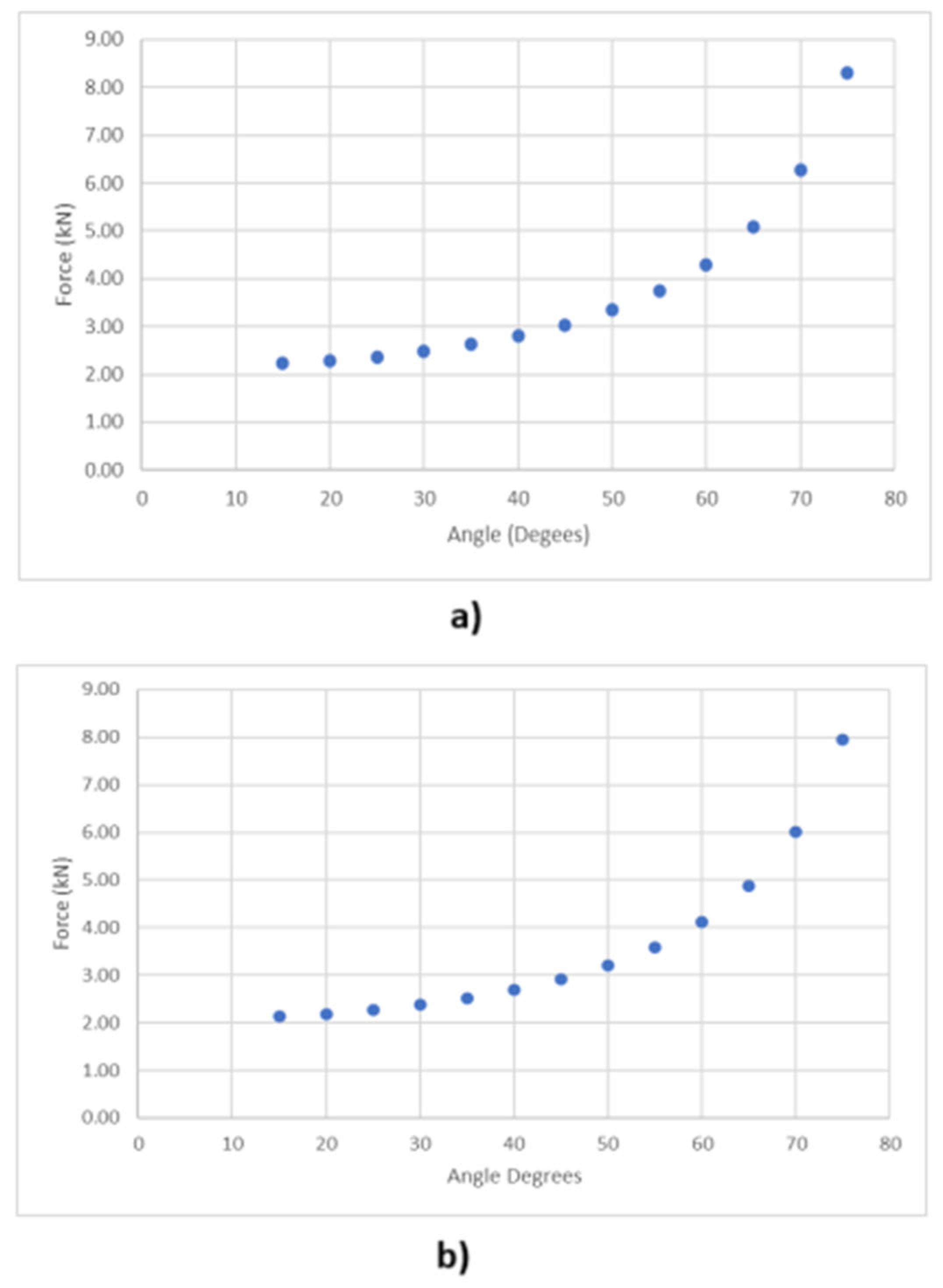

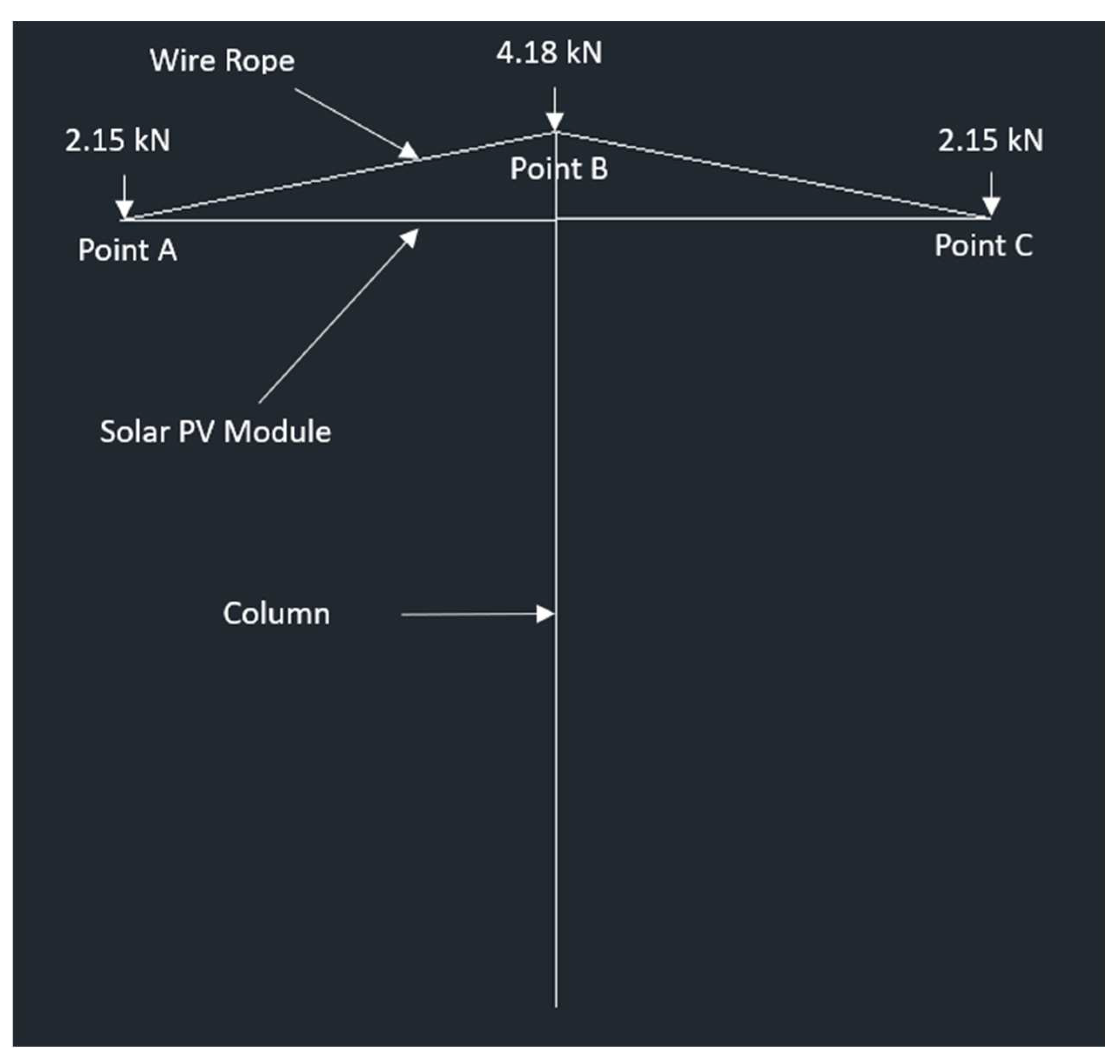

3.3.2. Wire Rope

3.3.3. Posts

4. Discussion

4.1. Wooden Racking Economics

4.2. Agrivoltaics

4.3. Wood Price Sensitivity

4.4. Permits and Certification

4.5. Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Design Analysis Assumptions

Appendix B. Load Calculations

B1. Snow Loads

| Factor | Value |

|---|---|

| Importance Factor (Is) | 1.15 |

| Snow Load Factor (Ss) | 1.90 |

| Basic Roof Snow Load Factor (Cb) | 0.80 |

| Wind Exposure Factor (Cw) | 0.75 |

| Slope Factor (Cs) | 1.00, 0.67, 0.33 and 0 |

| Accumulation Factor (Ca) | 1.00 |

| Associated Rain Load (Sr) | 0.40 |

B2. Wind Load

| Factor | Value |

| Wind Importance Factor (Iw) | 1.15 |

| Reference Velocity Pressure (q) | 0.47 |

| Exposure Factor (Ce) | 0.90 |

| Topographic Factor (Ct) | 1.00 |

| External Pressure Coefficient and Gust Effect Factor ‘Cp.Cg’ | -2.00 |

| Exposure Factor for Internal Pressure (Cei) | 0.90 |

| Internal Gust Effect Factor (Cgi) | 2.00 |

| Internal Pressure Coefficient (Cpi) | -0.70 |

B3. Dead Load

B4. Load Combinations

B5. Wooden Members Structural Capacity

B6. Structural Analysis For T-shaped Racking

Appendix C. Truss Analysis

C1. Calculations For 2-panel T-shaped Design:

Point A

-2.14 + FABcos(75) = 0

FAB = 8.30 kN

Point B

2FABcos(75) + 4.18 = FCOL

FCOL = 8.48 kN

C2. Calculations For Cantilever Carport Design:

Point A

-2.06 + FABcos(75) = 0

FAB = 7.95 kN

Point B

2FABcos(75) + 2.06 = FCOL

FCOL = 6.18 kN

References

- Pearce, J.M. Photovoltaics — a path to sustainable futures. Futures 2002, 34, 663–674.

- Fu, R.; Feldman, D.J.; Margolis, R.M. US Solar Photovoltaic System Cost Benchmark: Q1 2018 2018.

- Matasci, S. Solar Panel Cost: Avg. Solar Panel Prices by State in 2019: EnergySage. Solar News, EnergySage 2019.

- Branker, K.; Pathak, M.J.M.; Pearce, J.M. A Review of Solar Photovoltaic Levelized Cost of Electricity. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2011, 15, 4470–4482.

- Dudley, D. Renewable Energy Will Be Consistently Cheaper Than Fossil Fuels By 2020; Forbes, 2019.

- Solar Industry Research Data Available Online.

- Vaughan, A. Time to Shine: Solar Power Is Fastest-Growing Source of New Energy. The Guardian 2017.

- Barbose, G.L.; Darghouth, N.R.; LaCommare, K.H.; Millstein, D.; Rand, J. Tracking the Sun: Installed Price Trends for Distributed Photovoltaic Systems in the United States-2018 Edition 2018.

- IEA Solar PV – Renewables 2020 – Analysis Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2020/solar-pv (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Levin, T.; Thomas, V.M. Can Developing Countries Leapfrog the Centralized Electrification Paradigm? Energy for Sustainable Development 2016, 31, 97–107.

- Lang, T.; Ammann, D.; Girod, B. Profitability in Absence of Subsidies: A Techno-Economic Analysis of Rooftop Photovoltaic Self-Consumption in Residential and Commercial Buildings. Renewable Energy 2016, 87, 77–87.

- Hayibo, K.S.; Pearce, J.M. A Review of the Value of Solar Methodology with a Case Study of the U.S. VOS. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 137, 110599. [CrossRef]

- Agenbroad, J.; Carlin, K.; Ernst, K.; Doig, S. Minigrids in the Money: Six Ways to Reduce Minigrid Costs by 60% for Rural Electrification. Rocky Mountain Institute 2018.

- Alafita, T.; Pearce, J.M. Securitization of Residential Solar Photovoltaic Assets: Costs, Risks and Uncertainty. Energy Policy 2014, 67, 488–498.

- International, R. Photovoltaics After Grid Parity Plug-and-Play PV: The Controversy 2013. Renewables 2013.

- Mundada, A.S.; Nilsiam, Y.; Pearce, J.M. A Review of Technical Requirements for Plug-and-Play Solar Photovoltaic Microinverter Systems in the United States. Solar Energy 2016, 135, 455–470.

- Grafman, L.; Pearce, J.M. To Catch the Sun; Humboldt State University Press: Arcata, CA, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-947112-62-9.

- Barbose, G.; Darghouth, N.; Millstein, D.; Cates, S.; DiSanti, N.; Widiss, R. Tracking the Sun IX: The Installed Price of Residential and Non-Residential Photovoltaic Systems in the United States. 2016.

- Khan, M.T.A.; Norris, G.; Chattopadhyay, R.; Husain, I.; Bhattacharya, S. Autoinspection and Permitting With a PV Utility Interface (PUI) for Residential Plug-and-Play Solar Photovoltaic Unit. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 2017, 53, 1337–1346.

- Khan, M.T.A.; Husain, I.; Lubkeman, D. Power Electronic Components and System Installation for Plug-and-Play Residential Solar PV. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE; 2014; pp. 3272–3278.

- Lundstrom, B.R. Plug and Play Solar Power: Simplifying the Integration of Solar Energy in Hybrid Applications; Cooperative Research and Development Final Report. CRADA Number CRD-13-523.

- Mundada, A.S.; Prehoda, E.W.; Pearce, J.M. U.S. market for solar photovoltaic plug-and-play systems. Renewable Energy 2017, 103, 255–264.

- Fthenakis, V.; Alsema, E. Photovoltaics Energy Payback Times, Greenhouse Gas Emissions and External Costs: 2004–Early 2005 Status. Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications 2006, 14, 275–280.

- Feldman, D.; Barbose, G.; Margolis, R.; Bolinger, M.; Chung, D.; Fu, R.; Seel, J.; Davidson, C.; Darghouth, N.; Wiser, R. Photovoltaic System Pricing Trends: Historical, Recent, and Near-Term Projections 2015 Edition 2015.

- Feldman, D.; Barbose, G.; Margolis, R.; Wiser, R.; Darghout, N.; Goodrich, A. Photovoltaic (PV) Pricing Trends: Historical, Recent, and Near-Term Projections, Sunshot 2012.

- PVinsights PVinsights Available online: http://pvinsights.com/.

- Tamarack Solar Products Tamarack Solar Top of Pole Mounts Available online: https://www.altestore.com/store/solar-panel-mounts/top-of-pole-mounts-for-solar-panels/tamarack-solar-top-of-pole-mounts-6072-cell-solar-panels-p40745/ (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- TPM3 Pole Mount for Three 60/72 Cell Solar Modules Available Online.

- Precedence Research Agrivoltaics Market Is Expected to Increase at a 12.15% of CAGR by 2030 Available online: https://www.precedenceresearch.com/press-release/agrivoltaics-market (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- International Energy Agency Solar Available online: https://www.iea.org/energy-system/renewables/solar-pv (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Pearce, J.M. Agrivoltaics in Ontario Canada: Promise and Policy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3037. [CrossRef]

- Dupraz, C.; Marrou, H.; Talbot, G.; Dufour, L.; Nogier, A.; Ferard, Y. Combining Solar Photovoltaic Panels and Food Crops for Optimising Land Use: Towards New Agrivoltaic Schemes. Renew. Energy 2011, 36, 2725–2732. [CrossRef]

- Guerin, T.F. Impacts and Opportunities from Large-Scale Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Electricity Generation on Agricultural Production. Environmental Quality Management 2019, 28, 7–14. [CrossRef]

- Valle, B.; Simonneau, T.; Sourd, F.; Pechier, P.; Hamard, P.; Frisson, T.; Ryckewaert, M.; Christophe, A. Increasing the Total Productivity of a Land by Combining Mobile Photovoltaic Panels and Food Crops. Applied Energy 2017, 206, 1495–1507. [CrossRef]

- Mavani, D.D.; Chauhan, P.M.; Joshi, V. Beauty of Agrivoltaic System Regarding Double Utilization of Same Piece of Land for Generation of Electricity & Food Production. 2019, 10.

- Sekiyama, T.; Nagashima, A. Solar Sharing for Both Food and Clean Energy Production: Performance of Agrivoltaic Systems for Corn, A Typical Shade-Intolerant Crop. Environments 2019, 6, 65. [CrossRef]

- Daniels, T.L. The Development of Utility-Scale Solar Projects on US Agricultural Land: Opportunities and Obstacles. Socio Ecol Pract Res 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wittbrodt, B.; Laureto, J.; Tymrak, B.; Pearce, J.M. Distributed Manufacturing with 3-D Printing: A Case Study of Recreational Vehicle Solar Photovoltaic Mounting Systems. Journal of Frugal Innovation 2015, 1, 1. [CrossRef]

- Wittbrodt, B.T.; Pearce, J.M. Total U.S. Cost Evaluation of Low-Weight Tension-Based Photovoltaic Flat-Roof Mounted Racking. Solar Energy 2015, 117, 89–98. [CrossRef]

- Wittbrodt, B.; Pearce, J.M. 3-D Printing Solar Photovoltaic Racking in Developing World. Energy for Sustainable Development 2017, 36, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Arefeen, S.; Dallas, T. Low-Cost Racking for Solar Photovoltaic Systems with Renewable Tensegrity Structures. Solar Energy 2021, 224, 798-807. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M.; Meldrum, J.; Osborne, N. Design of Post-Consumer Modification of Standard Solar Modules to Form Large-Area Building-Integrated Photovoltaic Roof Slates. Designs 2017, 1, 9. [CrossRef]

- Vandewetering, N.; Hayibo, K.S.; Pearce, J.M. Impacts of Location on Designs and Economics of DIY Low-Cost Fixed-Tilt Open Source Wood Solar Photovoltaic Racking. Designs 2022, 6, 41. [CrossRef]

- Vandewetering, N.; Hayibo, K.S.; Pearce, J.M. Open-Source Design and Economics of Manual Variable-Tilt Angle DIY Wood-Based Solar Photovoltaic Racking System. Designs 2022, 6, 54. [CrossRef]

- Vandewetering, N.; Hayibo, K.S.; Pearce, J.M. Open-Source Vertical Swinging Wood-Based Solar Photovoltaic Racking Systems. Designs 2023, 7, 34. [CrossRef]

- Masna, S.; Morse, S.M.; Hayibo, K.S.; Pearce, J.M. The Potential for Fencing to Be Used as Low-Cost Solar Photovoltaic Racking. Solar Energy 2023, 253, 30–46. [CrossRef]

- Mayville, P.; Patil, N.V.; Pearce, J.M. Distributed Manufacturing of after Market Flexible Floating Photovoltaic Modules. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2020, 42, 100830. [CrossRef]

- Jamil, U.; Vandewetering, N.; Pearce, J.M. Solar Photovoltaic Wood Racking Mechanical Design for Trellis-Based Agrivoltaics. PLOS ONE.

- Franz, J.; Morse, S.; Pearce, J.M. Low-Cost Pole and Wire Photovoltaic Racking. Energy for Sustainable Development 2022, 68, 501–511. [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, S. Sustainable Construction for Urban Infill Development Using Engineered Massive Wood Panel Systems. Sustainability 2012, 4, 2707–2742. [CrossRef]

- We Explain Why Wood Is Eco Friendly and a Sustainable Material Available online: https://www.wooduchoose.com/ (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- ItTakesAForest #ItTakesAForest Available online: https://ittakesaforest.ca/people-products/wood-making-our-lives-better/ (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Ecology, C. Embodied Carbon Footprint Database. Circular Ecology 2023.

- Rana, S.; Vandewetering, N.; Powell, J.; Ariza, J.Á.; Pearce, J.M. Geographical Dependence of Open Hardware Optimization: Case Study of Solar Photovoltaic Racking. Technologies 2023, 11, 62. [CrossRef]

- Galvanized Aircraft Cable 7x19, 1/4 in. x 200 Feet Available online: https://www.bestmaterials.com/detail.aspx?ID=25064 (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Heliene 144HC M6 Bifacial Module 144 Half-Cut Monocrystalline 440W – 460W (HSPE-144HC-M6-Bifacial-Rev.05.Pdf) 2022.

- Molin, E.; Stridh, B.; Molin, A.; Wäckelgård, E. Experimental Yield Study of Bifacial PV Modules in Nordic Conditions. IEEE Journal of Photovoltaics 2018, 8, 1457–1463. [CrossRef]

- Riedel-Lyngskær, N.; Ribaconka, M.; Pó, M.; Thorseth, A.; Thorsteinsson, S.; Dam-Hansen, C.; Jakobsen, M.L. The Effect of Spectral Albedo in Bifacial Photovoltaic Performance. Solar Energy 2022, 231, 921–935. [CrossRef]

- Burnham, L.; Riley, D.; Walker, B.; Pearce, J. Performance of Bifacial Photovoltaic Modules on a Dual-Axis Tracker in a High-Latitude, High-Albedo Environment.; June 1 2019; pp. 1320–1327.

- Hayibo, K.S. Monofacial vs Bifacial Solar Photovoltaic Systems in Snowy Environments, Renewable Energy 2022.

- Heidari, N.; Gwamuri, J.; Townsend, T.; Pearce, J.M. Impact of Snow and Ground Interference on Photovoltaic Electric System Performance. IEEE Journal of Photovoltaics 2015, 5, 1680–1685. [CrossRef]

- Rigging Canada 3/8" x 500 Galvanized Aircraft Cable Available online: https://riggingcanada.ca/store/wire-rope-and-aircraft-cable/aircraft-cable/aircraft-cable-7x19-galvanized/38-x-500-galvanized-aircraft-cable/ (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Sadat, S.A.; Vandewetering, N.; Pearce, J.M. Mechanical and Economic Analysis of Conventional Aluminum Photovoltaic Module Frames, Frames with Side Holes, and Open-Source Downward-Fastened Frames for Non-Traditional Racking. SOL 146.

- Beinert, A.J.; Romer, P.; Heinrich, M.; Mittag, M.; Aktaa, J.; Neuhaus, D.H. The Effect of Cell and Module Dimensions on Thermomechanical Stress in PV Modules. IEEE Journal of Photovoltaics 2020, 10, 70–77. [CrossRef]

- Tummalieh, A.; Beinert, A.J.; Reichel, C.; Mittag, M.; Neuhaus, H. Holistic Design Improvement of the PV Module Frame: Mechanical, Optoelectrical, Cost, and Life Cycle Analysis. Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications n/a. [CrossRef]

- CanmetENERGY/Housing, Buildings and Communities National Resources Canada Solar Ready Guidelines. 2013.

- 2018 NDS Available online: https://awc.org/publications/2018-nds/ (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Greentech Renewables Solar PV Racking Options - Comparison Chart | Greentech Renewables Available online: https://www.greentechrenewables.com/article/solar-pv-racking-options-comparison-chart (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Vandewetering, N.; Hayibo, K.S.; Pearce, J.M. Open-Source Photovoltaic—Electrical Vehicle Carport Designs. Technologies 2022, 10, 114. [CrossRef]

- MarketWatch 2023 Guide to Solar Carports: Are They Worth It? Available online: https://www.marketwatch.com/guides/solar/solar-carport/ (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- SunWatts Solar Carport Mount Available online: https://sunwatts.com/carport-mounts/ (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Feldman, D.; Ramasamy, V.; Fu, R.; Ramdas, A.; Desai, J.; Margolis, R. U.S. Solar Photovoltaic System and Energy Storage Cost Benchmark (Q1 2020); 2021; p. NREL/TP--6A20-77324, 1764908, MainId:26270.

- Wüstenhagen, R.; Wolsink, M.; Bürer, M.J. Social Acceptance of Renewable Energy Innovation: An Introduction to the Concept. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2683–2691. [CrossRef]

- Batel, S.; Devine-Wright, P.; Tangeland, T. Social Acceptance of Low Carbon Energy and Associated Infrastructures: A Critical Discussion. Energy Policy 2013, 58, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Calvert, K.; Mabee, W. More Solar Farms or More Bioenergy Crops? Mapping and Assessing Potential Land-Use Conflicts among Renewable Energy Technologies in Eastern Ontario, Canada. Applied Geography 2015, 56, 209–221. [CrossRef]

- Calvert, K.; Pearce, J.M.; Mabee, W.E. Toward Renewable Energy Geo-Information Infrastructures: Applications of GIScience and Remote Sensing That Build Institutional Capacity. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2013, 18, 416–429. [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K. Exploring and Contextualizing Public Opposition to Renewable Electricity in the United States. Sustainability 2009, 1, 702–721. [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Lakshmi Ratan, P. Conceptualizing the Acceptance of Wind and Solar Electricity. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012, 16, 5268–5279. [CrossRef]

- Dias, L.; Gouveia, J.P.; Lourenço, P.; Seixas, J. Interplay between the Potential of Photovoltaic Systems and Agricultural Land Use. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 725–735. [CrossRef]

- Agostini, A.; Colauzzi, M.; Amaducci, S. Innovative Agrivoltaic Systems to Produce Sustainable Energy: An Economic and Environmental Assessment. Applied Energy 2021, 281, 116102. [CrossRef]

- Singh, nbsp K.; Kumar, S.M. and M.N. A Review on Power Management and Power Quality for Islanded PV Microgrid in Smart Village. INDJST 2017, 10, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.S.; Althaibani, A.; Esa, Y.; Mhandi, Y.; Mohamed, A.A. Impact of Clustering Microgrids on Their Stability and Re-Silience during Blackouts. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Smart Grid and Clean Energy Technologies (ICSGCE; October 2015; pp. 195–200.

- Record Volatility Presides Over the Lumber Market Available online: http://www.contractlumber.com/blog/2021/9/3/record-volatility-presides-over-the-lumber-market (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- JuliaSeth Pressure Treated Lumber Prices 2015 vs 2021. r/halifax 2021.

- What Is Driving Price Volatility in the Wood Products Industry? Fastmarkets 2022.

- Municipal Climate Change Action Center Solar Friendly Municipalities - Permit Taxes 2019.

- Toronto, C. of Solar Permitting & Regulations Available online: https://www.toronto.ca/services-payments/water-environment/net-zero-homes-buildings/solar-to/solar/ (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Solar Panels Available online: https://www.waterloo.ca/en/living/solar-panels.aspx (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Building Permits | City of London Available online: https://london.ca/living-london/building-renovating/building-permits (accessed on 29 November 2023).

- Joist Hangers and End Moments - Structural Engineering General Discussion - Eng-Tips Available online: https://www.eng-tips.com/viewthread.cfm?qid=339938 (accessed on 27 August 2023).

- Canada, N.R.C. National Building Code of Canada 2020 2022.

- Dead Loads Available online: https://www.designingbuildings.co.uk/wiki/Dead_loads (accessed on 18 June 2023).

| Lumber | Lumber Breadth ‘b’ (m) |

Lumber Height ‘h’ (m) |

Area ‘A’ (m2) A=bh |

Moment of Inertia ‘I’ (m4) I=bh3/12 |

First Moment of Area ‘Q’ (m3) Q=hA/8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2x12 | 0.038 | 0.286 | 0.010868 | 7.4079x10-05 | 3.8853 x10-04 |

| 2x4 | 0.038 | 0.089 | 0.003382 | 2.2324x10-06 | 3.7624x10-05 |

| 2x6 | 0.038 | 0.140 | 0.005320 | 8.6893x10-06 | 9.3100 x10-05 |

| 2x8 | 0.038 | 0.184 | 0.006992 | 1.9726x10-05 | 1.6081 x10-04 |

| 2x10 | 0.038 | 0.235 | 0.008930 | 4.1096x10-05 | 2.6232 x10-04 |

| 6x6 | 0.140 | 0.140 | 0.019600 | 3.2013x10-05 | 3.4300 x10-04 |

| Diameter - Inches (m) |

Breaking Strength – lbs. (N) |

Approx. Wt. / 1000 ft | Workload Limit - lbs. (N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1/16 (0.0016) | 480 (2135) | 0.75 | 96 (427) |

| 3/32 (0.0024) | 1000 (4448) | 16.5 | 200 (890) |

| 1/8 (0.0032) | 2000 (8896) | 29 | 400 (1779) |

| 5/32 (0.0040) | 2800 (12455) | 45 | 560 (2491) |

| 3/16 (0.0048) | 4200 (18682) | 65 | 840 (3736) |

| 7/32 (0.0056) | 5600 (24910) | 86 | 1120 (4982) |

| 1/4 (0.0064) | 7000 (31138) | 110 | 1400 (6228) |

| 5/16 (0.0079) | 9800 (43592) | 173 | 1960 (8718) |

| 3/8 (0.0095) | 14400 (64054) | 243 | 2880 (1281) |

| Member Name | Piece1 | Cost per Piece2 | Quantity | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joists | 2x12x8 | $35.00 | 1 | $35.00 |

| Posts | 6x6x10 | $52 | 2 | $104.00 |

| Joist to Post Connection | 2x4 Fence Bracket | $0.43 | 2 | $0.86 |

| 7x19 PVC Coated & Galvanized Aircraft Cable | 3/8" | $55.44 | 1 | $55.44 |

| Connections | 2-1/2” Brown Deck Screws | $2.61 | 1 | $2.61 |

| Cable Clamp | 5/16" Wire Rope Clip - Zinc Plated | $1.99 | 16 | $31.84 |

| Turnbuckle | 9-3/8 Turnbuckle | $6.94 | 4 | $27.76 |

| Hooks | 4-3/8 Hooks | $5.22 | 8 | $41.76 |

| Washers | ¼ Washers | $1.90 | 1 | $1.90 |

| Eye Bolts | 1/4x2 Eye Bolts | $1.72 | 8 | $13.76 |

| Hinges | Light-duty (2”) | $2.69 | 4 | $10.76 |

| Nut & Bolt | ¼ inch | $2.78 | 1 | $2.78 |

| Metal fixture | 2” | $8.49 | 1 | $8.49 |

| Total Cost with No Concrete | $336.95 | |||

| Concrete for Posts | 30 MPa Quikrete concrete | $6.38 | 10 bags | $63.80 |

| Total Cost: | $400.75 |

| Member Name | Piece1 | Cost per Piece2 | Quantity | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joists | 2x6x8 | $12.78 | 1 | $12.78 |

| Posts | 8x8x10 | $125.33 | 2 | $250.66 |

| Joist to Post Connection | 2x4 Fence Bracket | $0.43 | 2 | $0.86 |

| 7x19 PVC Coated & Galvanized Aircraft Cable | 3/8" | $55.44 | 1 | $55.44 |

| Connections | 2-1/2” Brown Deck Screws | $2.61 | 1 | $2.61 |

| Cable Clamp | 5/16" Wire Rope Clip - Zinc Plated | $1.99 | 8 | $15.92 |

| Turnbuckle | 9-3/8 Turnbuckle | $6.94 | 2 | $13.88 |

| Hooks | 4-3/8 Hooks | $5.22 | 4 | $20.88 |

| Washers | ¼ Washers | $1.90 | 1 | $1.90 |

| Eye Bolts | 1/4x2 Eye Bolts | $1.72 | 4 | $6.88 |

| Hinges | Light-duty (2”) | $2.69 | 2 | $5.38 |

| Nut & Bolt | ¼ inch | $2.78 | 1 | $2.78 |

| Metal Fixture | 2” | $8.49 | 1 | $8.49 |

| Total Cost with No Concrete | $398.45 | |||

| Concrete for Posts | 30 MPa Quikrete concrete | $6.38 | 10 bags | $63.80 |

| Total Cost: | $462.25 |

| Member Name | Piece1 | Cost per Piece2 | Quantity | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joists | 2x12x8 | $35.00 | 1 | $35.00 |

| Posts | 8x8x10 | $125.33 | 2 | $250.66 |

| Joist to Post Connection | 2x4 Fence Bracket | $0.43 | 2 | $0.86 |

| 7x19 PVC Coated & Galvanized Aircraft Cable | 3/8" | $110.88 | 1 | $110.88 |

| Connections | 2-1/2” Brown Deck Screws | $2.61 | 1 | $2.61 |

| Cable Clamp | 5/16" Wire Rope Clip - Zinc Plated | $1.99 | 16 | $31.84 |

| Turnbuckle | 9-3/8 Turnbuckle | $6.94 | 4 | $27.76 |

| Hooks | 4-3/8 Hooks | $5.22 | 8 | $41.76 |

| Washers | ¼ Washers | $1.90 | 1 | $1.90 |

| Eye Bolts | 1/4x2 Eye Bolts | $1.72 | 8 | $13.76 |

| Metal Fixture | 2” | $8.49 | 1 | $8.49 |

| Nut & Bolt | ¼ inch | $2.78 | 1 | $2.78 |

| Hinges | Light-duty (2”) | $2.69 | 4 | $10.76 |

| Total Cost with No Concrete | $539.05 | |||

| Concrete for Posts | 30 MPa Quikrete concrete | $6.38 | 10 bags | $63.80 |

| Total Cost: | $602.85 |

| Material | Thickness [mm] |

Density [tonne/mm3] |

Young’s modulus [MPa] |

Poisson’s ratio [-] |

Strength [MPa] |

Number of elements | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frame | Aluminum (Alloy 6063 [63]) |

1.80 | 2.70E-9 | 70000 | 0.33 | 214 yield 241 tensile |

15980 |

| Sealing | Rubber (Polyurethane elastomer [63]) |

2.00 | 6.70E-11 | 7.40 | 0.30 | 0.0814 – 103 | 3654 |

| Laminate | Glass (soda-lime glass [63]) |

3.2 0 | 2.50E-09 | 70000 | 0.20 | Compressive Strength = 274 | 64288 |

| Solar cells (Czochralski silicon [63]) |

0.18 | 2.329E-9 | 112400 | 0.28 | Compressive Strength = 120 | ||

| Encapsulation (ethylene vinyl acetate [63]) |

0.45 | 9.6E-10 | T-dep. | 0.40 | 3.4-10 | ||

| Backsheet (TPT [63]) | 0.22 | 2.52E-9 | 3500 | 0.29 | Break stress = 132 | ||

| Load Combination | Load [kPa] (upto 15o) | Load [kPa] (30o) | Load [kPa] (upto 45o) | Load [kPa] (60o) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.9D + 1.4W -0.5S | -2.99 | -2.77 | -2.56 | -2.33 |

| 1.25D + 1.5S – 0.4W | 3.62 | 2.96 | 2.31 | 1.65 |

| Factor | Value (MPa) |

|---|---|

| fb | 6.03 |

| fv | 0.93 |

| ft | 3.10 |

| fc | 7.93 |

| E | 9652.66 |

| Emin | 3516.33 |

| Factor | Value |

|---|---|

| CD | 1.15 |

| CT | 1.00 |

| CM | 1.00, 0.97 and 0.90 |

| CL | 0.64. 0.76 |

| Cfu | 1.2 |

| Ci | 1, 0.8 and 0.95 |

| Cr | 1.00 |

| CF | 1.10 |

| CP | 0.29 |

| Factored Capacities | Value (MPa) |

|---|---|

| fb* | 4.68 |

| fv* | 0.83 |

| ft* | 3.14 |

| fc* | 2.94 |

| E* | 8253.03 |

| Emin* | 3006.46 |

| Lumber | Resisting Bending Moment ‘Mr’ (kN-m) |

Resisting Shear Force ‘Vr’ (kN) |

Resisting Tensile Force ‘Tr’ (kN) |

Resisting Compressive Force ‘Cr’ (kN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2x4 | 0.23 | 1.87 | 10.62 | 9.97 |

| 2x6 | 0.58 | 2.95 | 16.70 | 15.69 |

| 2x8 | 1.00 | 3.87 | 21.95 | 20.62 |

| 2x10 | 1.64 | 4.94 | 28.04 | 26.34 |

| 4x10 | 3.27 | 9.89 | 56.08 | 52.67 |

| 2x12 | 2.42 | 6.02 | 34.12 | 32.05 |

| 4x4 | 0.55 | 4.39 | 24.87 | 23.36 |

| 6x6 | 2.14 | 10.85 | 61.54 | 57.80 |

| Racking System | Cost (CAD) | Cost (CAD/Watt) |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed Racking Configuration [43] | 426 (389) | 0.35 (0.32)* |

| Variable Tilt Racking Configuration [44] | 438 (406) | 0.36 (0.34)* |

| Vertical Wood Racking Configuration [45] | 371 (300) | 0.15 (0.13)* |

| T-shaped Racking Configuration (2-module Design) | 397 | 0.43 |

| T-shaped Racking Configuration (4-module Design) | 1155 | 0.63 |

| Sloped Racking Configuration | 372 | 0.40 |

| Inverse Y Racking Configuration | 427 | 0.46 |

| Fixed Racking Configuration (Modified to 1.8m with 6x6 columns) | 526 | 0.44 |

| Variable Tilt Racking Configuration (Modified to 1.8m with 6x6 columns) | 598 | 0.50 |

| Cantilever Carport Racking Configuration (one module) | 471 | 1.00 |

| Cantilever Carport Racking Configuration (two modules) | 612 | 0.66 |

| Variable tilt Wood and Wire Rope T-shaped Configuration | 410 | 0.44 |

| Country | Price [CAD]1 | Source2 |

|---|---|---|

| Canada | $7.69 | The Home Depot |

| USA | $6.62 | The Home Depot |

| United Kingdom | $5.84 | B & Q |

| Netherlands | $16.04 | Woodvision |

| Australia | $13.29 | Australian Treated Pine Pty Ltd. |

| Brazil | $12.13 | Fremade Madeiras |

| India | $12.45 | IndiaMart |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).