1. Introduction

Since the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic, it has become evident that apart from the respiratory manifestations, SARS-CoV-2 can cause serious, even lethal cardiac complications. Acute cardiac injury, encountered in 19.7- 27.8% of hospitalized patients is associated with greater disease severity and mortality [

1,

2,

3], and the majority of the reported cases include heart failure, acute coronary syndrome (ACS), and myocarditis [

4]. Here, we present the case of a male patient hospitalized with severe COVID-19 pneumonia who exhibited ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), attributed to spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD). We also make a review of the literature on similar case reports and highlight the fact that COVID-19 infection may provide the pathophysiologic substrate for the occurrence of SCAD.

2. Case presentation

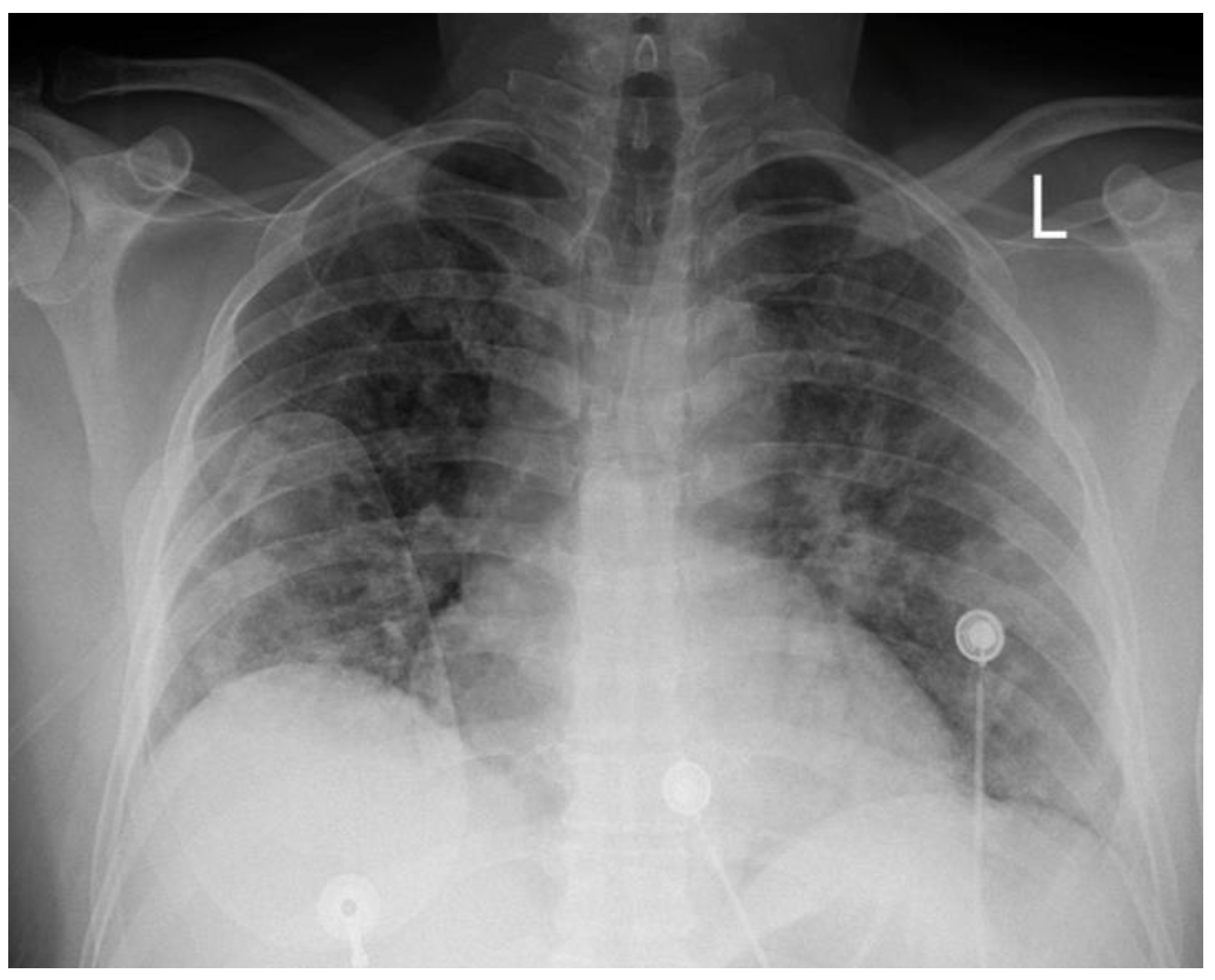

A 51-year-old Caucasian male, with a medical history of hypertension was admitted to our hospital’s COVID-19 clinic, due to recent onset of fever, cough, and respiratory distress along with positive real-time polymerase chain reaction assay for SARS-CoV-2 infection. He was initially administered with oxygen via high-flow-nasal-cannula, dexamethasone, remdesivir, tocilizumab bolus and fondaparinux for thromboprophylaxis. On day-7, while in severe respiratory distress (

Figure 1) supported with continuous positive airway pressure-helmet, the patient complained of retrosternal chest pain, radiating in his left arm with concomitant diaphoresis. His blood pressure was 140/80mmHg and his pulse was 55 beats per minute. Lung auscultation revealed rales in both lungs, while the rest of the physical exam was normal. An electrocardiogram (ECG) was immediately obtained, which demonstrated normal sinus rhythm and 2mm ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, AVF, V5, V6 along with ST-segment depression in leads V1-V2.

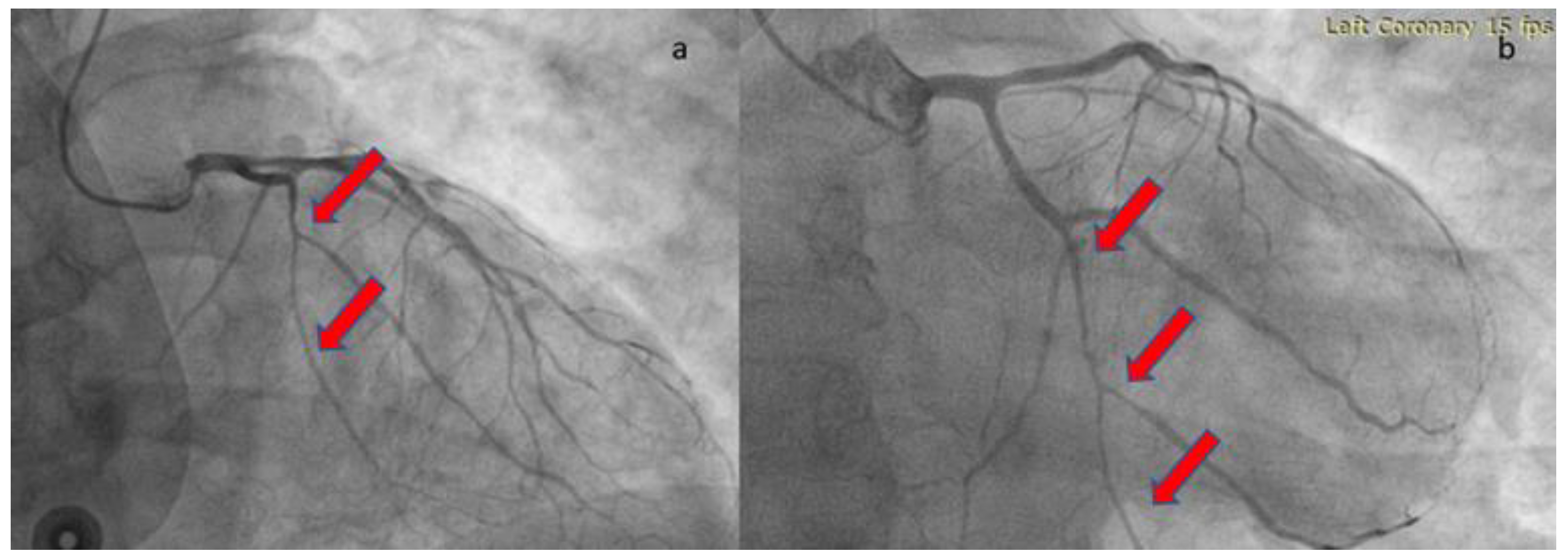

The patient was loaded with aspirin (ASA) 325mg and ticagrelor 180mg and was transferred to the catheterization laboratory, where emergent coronary angiography was performed via right radial access. During contrast injection in the left coronary system, a long smooth 70-80% stenosis was revealed along the mid portion of left circumflex artery (LCX) extending to the distal part of the vessel, including an obtuse marginal branch (

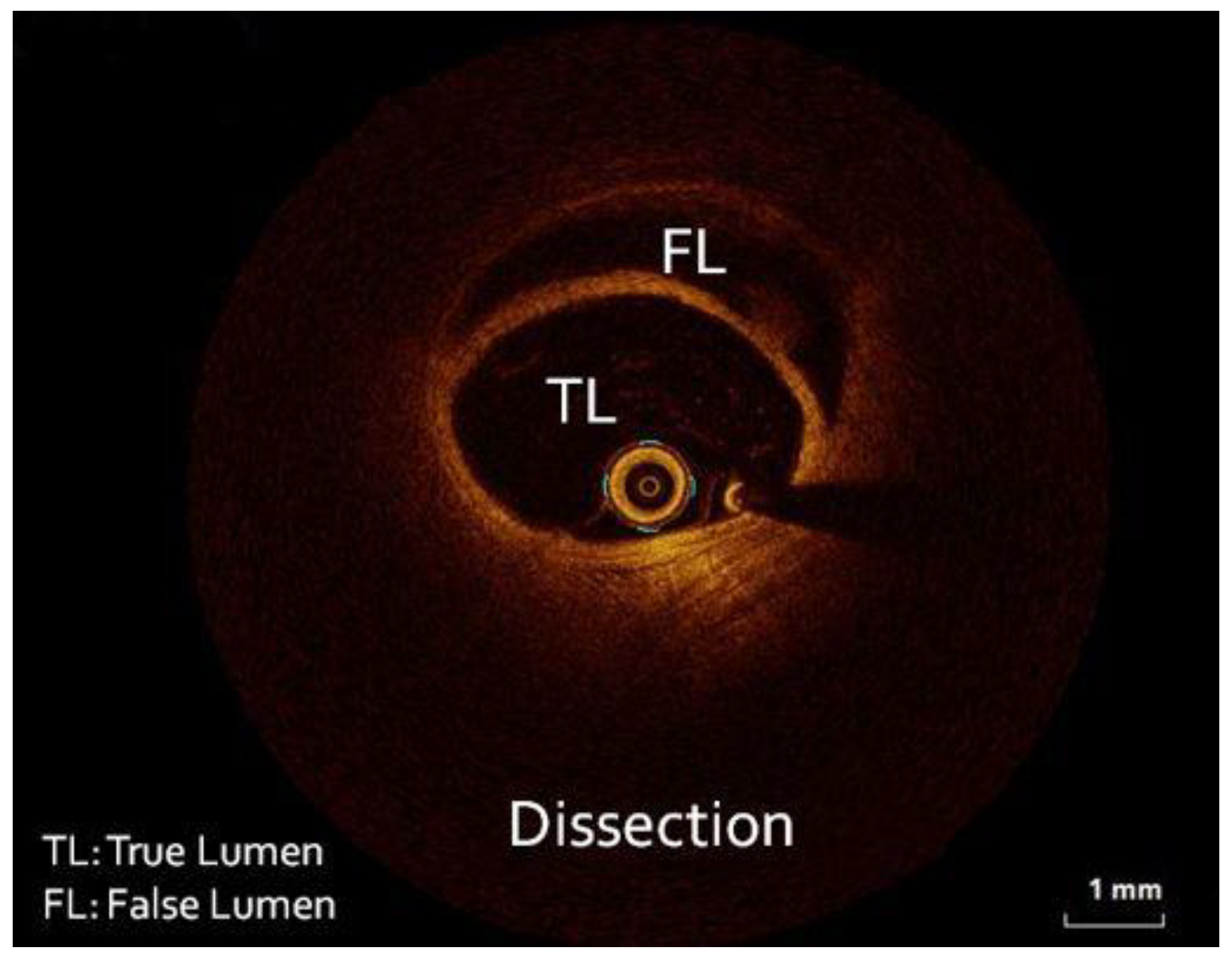

Figure 2). Despite intracoronary administration of nitroglycerin, the narrowing along the vessels remained unchanged, hence we proceeded with intracoronary imaging using optical coherent tomography that revealed SCAD (

Figure 3). The remainder of the coronary tree was normal.

In the catheterization laboratory the patient was asymptomatic with Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) III flow in LCX, hence a conservative approach was adopted. Peak high sensitivity troponin level was 35200 pg/ml. During his hospitalization, the patient received ASA and bisoprolol, and continued his former antihypertensive treatment with a combination of angiotensin II receptor blocker/ calcium channel antagonist for efficient blood pressure control. Fondaparinux 2,5mg/day was also administered subcutaneously to prevent thromboembolism, while we decided to discontinue the second antiplatelet. His echocardiogram revealed hypokinesia in the inferior and inferolateral wall with an estimated left ventricular ejection fraction of 50%. His pulmonary function gradually recovered, and he was discharged 10 days later with no further complications, with ASA and rivaroxaban 10mg once a day for 35 days.

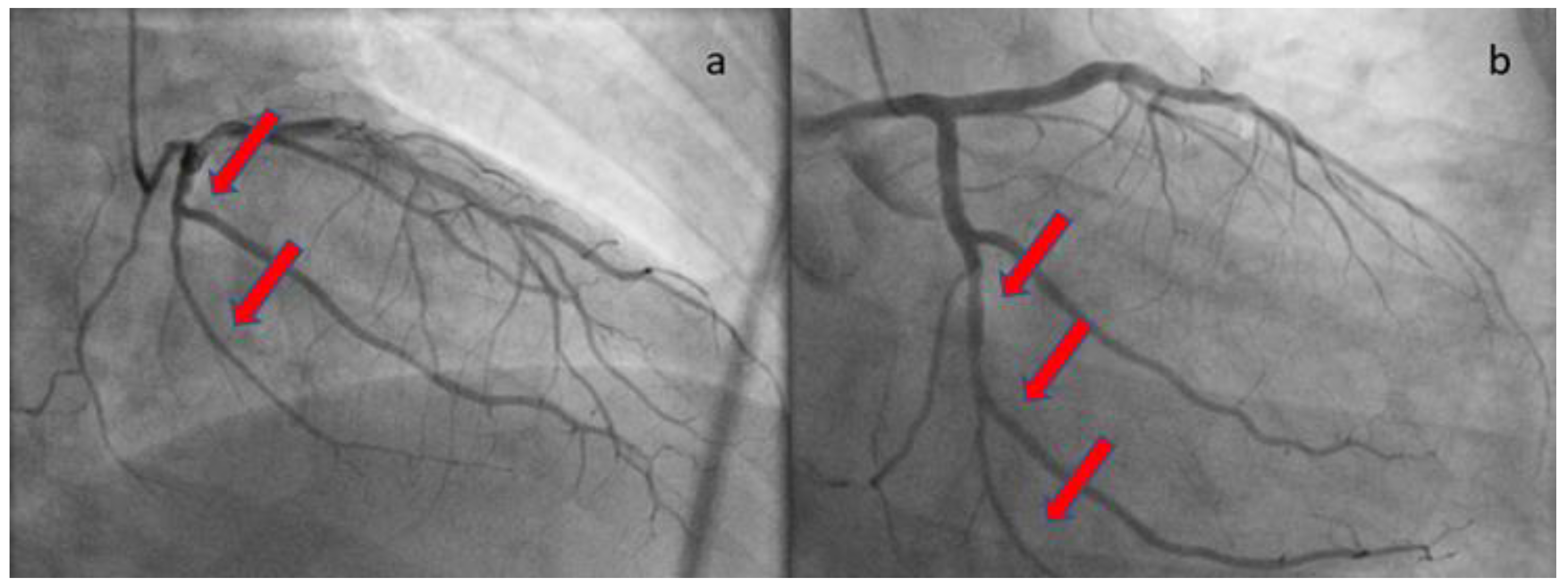

At the one-month follow-up, the patient remained uncomplicated. The echocardiographic study demonstrated full recovery of systolic function with no hypokinesia present. The repeat angiographic image was also significantly improved (

Figure 4). Rivaroxaban was discontinued and the patient was advised to continue ASA for at least a year. He was also subjected to computed tomography angiography from the brain to pelvis, as part of the screening for extracoronary arteriopathies (especially fibromuscular dysplasia), which did not reveal abnormal findings. Laboratory analyses after one month from the acute infection, including antinuclear antibodies, antibodies to β2-macroglobulin, and rheumatoid factor, were also negative, excluding the presence of chronic systemic inflammatory disease.

3. Discussion

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection is an important cause of ACS, which accounts for 1.7-4% of cases [

5]. In the new era of intracoronary imaging, it has become feasible to recognize even ambiguous cases, and it seems to be more frequent than initially thought. It most commonly affects women ≤50 years old, lacking traditional cardiovascular risk factors [

5]. SCAD is the result of disruption in the vessel wall layers in any epicardial coronary artery, with the formation of intramural hematoma, and is non-iatrogenic, nontraumatic and nonatherosclerotic. On the contrary, it has been associated with pregnancy, multiparity, inflammatory, or vascular conditions, especially fibromuscular dysplasia, and in >50% of cases a precipitating factor is reported, including intense exercise, Valsalva, emotional stress, coughing, vomiting or labor and delivery [

6]. The management is mainly conservative, as it has been shown that intervention in the labile vessel wall can result in extension of the dissection and worse outcomes, except for patients with hemodynamic instability, left main artery dissection, or ongoing ischemia, where revascularization is the only viable option [

5].

SARS-CoV-2 is a single-stranded RNA virus. His entry to the human body is mediated mainly by the binding of the S1 unit of the spike protein to the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) receptor of the host cells, which is commonly encountered in the lungs, heart, and vessels. Despite the direct damage to the host cells, SARS-Cov-2 promotes severe systemic inflammation and immune cell overactivation, leading to a ‘cytokine storm”. The imbalance of T-cell activation with dysregulated release of inflammatory molecules, including interleukin (IL)-6, IL-17, and other cytokines, plays a crucial role in the cardiovascular morbidity in COVID-19 [

7].

3.1. Potential pathophysiologic mechanisms of SCAD related with COVID-19

This clinical case, along with the other case reports, suggests a possible association between SCAD and COVID-19 infection. It is well established that patients with COVID-19 often experience significant cardiovascular complications, including heart failure, acute coronary syndromes, and myocarditis [

4]. SCAD may be associated with various pathophysiologic mechanisms that occur during COVID-19 infection. Potential mechanisms include the following:

The accumulation of macrophages and T cells in coronary adventitia and periadventitial fat, found in autopsies of COVID-19 patients, could induce excessive levels of cytokines and other mediators of the inflammatory response, resulting in disruption of the vessel wall layers and coronary dissection. Furthermore, the provoked sympathetic over-stimulation is an important factor of endothelial dysfunction and vulnerability [

8].

The infiltration of the vasa vasorum by the inflammatory cells may cause direct damage and rupture with the formation of intramural hematoma. Apart from this, an additional factor contributing to the generation of intramural hematoma may be the excessive angiogenesis of the vasa vasorum, owing to the cytokines and the other inflammatory molecules’ signaling [

9].

Except for the indirect damage mediated by the cytokines and the inflammatory cells, SARS-CoV-2 virus binds directly to the ACE-2 receptors in the vascular endothelial and smooth cells, and can cause inflammation in the coronary vessel wall, impairment of the vascular tone, and deregulation of the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems, making the vessel wall more prone to dissection [

7].

The dysregulation of the vascular tone can cause coronary artery spasm, an identified precipitant of SCAD [

6].

Finally, the administration of high doses of corticosteroids, commonly used in the treatment of COVID-19 patients, may also cause intimal tear of the weakened arterial wall, resulting in formation of intramural hematoma [

10].

3.2. Review of case reports on SCAD and COVID-19 infection

A substantial number of patients who manifested SCAD after or during COVID-19 infection were of male gender, specifically 7 patients out of 16. This observation diverges from the typical epidemiological pattern of SCAD, wherein 87-95% of cases predominantly occur in women, aged between 44 and 53 years [

5]. Regarding past medical history, most of patients, n=13 (81.2%) was lacking the typical conditions or precipitating factors found in SCAD, including arteriopathies, connective tissue disorders, pregnancy or multiparity [

5]. Two of them were on corticosteroid treatment [

10,

11], one patient had migraine [

12] and in one case intense cough precipitated SCAD [

13]. The timing of the occurrence of SCAD was synchronous with COVID-19 infection in 12 cases [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], however the remaining patients presented with SCAD after 2 weeks to 3 months of the illness. Notably, the severity of symptoms associated with the coronavirus infection appears to lack a direct correlation with the occurrence of SCAD. Among the documented cases, three patients remained asymptomatic [

12,

19,

20] during the COVID-19 infection, while in eight patients (50%), only mild symptoms of the viral infection were evident. Furthermore, only five patients demonstrated severe disease [

11,

13,

14,

18].

Out of 16 patients, six patients including ours (37.5%) presented with STEMI [

10,

12,

13,

14,

20,

22], one with cardiogenic shock [

18] and one survived cardiac arrest [

23], owing to ventricular fibrillation. The remainder suffered from non ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). The most affected vessel was LAD (62.5%), following LCX in 4 patients, RCA in 3 patients and RI in one patient. Multiple coronary artery dissection was demonstrated in two patients [

10,

14]. In literature, multivessel dissection is reported in 9-23% of cases [

6]. All the patients survived, and the ejection fraction was restored within normal values, in the cases where it is mentioned.

Great variability is shown regarding the antithrombotic treatment in patients with SCAD in general, and especially in patients with SCAD suffering simultaneously from COVID-19 infection. According to the existing data from these case reports, among patients that featured SCAD during the acute phase of the disease, two received DAPT following conservative treatment [

12,

14], one received coagulation on top of DAPT without any other obvious indication rather than COVID-19 infection [

13], two were prescribed only ASA [

15,

18], two of them received DAPT following angioplasty [

16,

17], and one after plain old balloon angioplasty (POBA) was discharged on ASA alone [

20]. Finally, one patient received clopidogrel plus warfarin in the presence of apical thrombus [

21], and in our case, we decided single antiplatelet therapy plus rivaroxaban in prophylactic dose to avoid thromboembolism during the acute phase.

Table 1.

Case reports concerning the occurrence of SCAD in patients infected with the coronavirus.

Table 1.

Case reports concerning the occurrence of SCAD in patients infected with the coronavirus.

| Author, Published date |

Sex, age (years) |

Past Medical History |

Timing of COVID-19 infection, regarding SCAD occurrence |

COVID-19 severity |

Diagnosis of ACS |

Initial EF |

Culprit arteries |

Treatment/Antithrombotics |

Survival |

| Gasso et al., 2020 [14] |

Male, 39 |

None |

Index hospitalization |

Severe/ intubation |

STEMI with no CV symptoms |

50-55%, hypokinetic RV |

LAD+ OM1 |

Conservative/ DAPT |

Yes |

| Papanikolaou et al., 2020 [13] |

Female, 51 |

HTN, smoking |

Index hospitalization |

Severe, high-flow-nasal-cannula |

STEMI |

N/A |

LAD |

Conservative/ DAPT+ anticoagulation |

Yes with SCAD healing |

| Cannata et al., 2020 [22] |

Female, 45 |

None |

8 weeks ago typical symptoms of COVID-19 |

Mild |

STEMI |

Anterior wall hypokinesia |

LAD |

Conservative/ DAPT |

Yes with EF improvement |

| Kireev et al., 2020 [10] |

Male, 35 |

Serpinginous choroiditis (low CS dose), smoking, overweight |

2 weeks ago |

Mild |

STEMI |

N/A |

RI+ RCA |

PCI in RI+ conservative in RCA/ DAPT+ anticoagulation (IV UFH) |

Yes |

| Kumar et al., 2020 [12] |

Female, 48 |

Migraines, hyperlipidemia |

Index presentation |

No symptoms |

STEMI |

45-50% |

LAD |

Conservative/ DAPT for a year |

Yes |

| Courand et al., 2020 [15] |

Male, 55 |

PAD |

Index hospitalization |

Mild |

NSTEMI |

60% |

RCA |

Conservative/ ASA |

Yes |

| Albiero et al., 2020 [16] |

Male, 70 |

HTN, type 2 diabetes, PCI in LCX, Smoking |

Index hospitallization |

Mild |

NSTEMI |

40-45% |

LAD |

PCI with DES/ ASA+ clopidogrel |

Yes with EF improvement |

| Emren et al., 2021 [17] |

Male, 50 |

None |

Index presentation |

Mild |

NSTEMI |

55% |

RCA |

PCI with BMS/ ASA+ clopidogrel |

Yes |

| Aparisi et al., 2021 [18] |

Male, 40 |

None |

Index hospitalilzation |

Severe/ intubation |

Cardiogenic shock |

35% |

LAD |

Conservative, ASA |

Yes |

| Ahmad et al., 2021 [23] |

Female, 43 |

AF |

12 weeks ago |

Mild |

Cardiogenic shock |

20% |

LCX |

Conservative/ Not reported |

EF=60% |

| Pettinato et al., 2022 [11] |

Female, 43 |

MIS-A after COVID-19 (CS treatment), hypothyroidism |

3 month ago |

Mild at first- MIS-A later |

NSTEMI |

40%+ apical thrombus |

LAD |

Conservative/ ASA+ clopidogrel+ warfarin for 1 month |

Yes with EF=60%, thrombus resolution |

| Lewars et al., 2022 [19] |

Female, 51 |

Anxiety, recovered postpartum CMP 15 years ago |

At index presentation |

No symptoms |

NSTEMI |

Dyskinetic apex, EF=60% |

LAD |

Conservative/ N/A |

Yes with SCAD healing |

| Ansari et al., 2022 [24] |

Female, 58 |

Hyperlipidemia |

2 months ago |

Mild lung involvement, severe thrombocytopenia |

NSTEMI |

50% |

LCX |

Conservative/ ASA+ clopidogrel |

Yes |

| Shah et al., 2023 [20] |

Female, 67 |

FHCAD |

Index presentation |

No symptoms |

STEMI |

65%, apical akinesia |

LAD |

POBA in LAD/ ASA |

Yes, recovery |

| Bashir et al., 2023 [21] |

Female, 36 |

Morbid obesity (BMI=49kg/m2) |

Index presentation |

Mild, fever |

NSTEMI |

35%, thrombus formation |

LAD |

Conservative/ Clopidogrel+ warfarin |

Yes, EF=60%, thrombus resolution |

| Papageorgiou et al., 2023 |

Male, 51 |

HTN |

Index presentation |

Severe, continuous positive airway pressure-helmet |

STEMI |

50% |

LCX |

Conservative/ ASA for 1 year+ rivaroxaban 10mg OD for 35 days |

Yes, EF= 60%, SCAD healing |

3.3. STEMI management during the COVID-19 pandemic

At the outset of COVID-19 pandemic, the first edition of the Consensus of Chinese experts on diagnosis and treatment processes of acute myocardial infarction in the context of prevention and control of COVID-19 advocated that priority should be given in thrombolysis of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), to mitigate the virus spreading [

26]. This instruction was also adopted at first by some cardiologic communities in Europe. However, later as the medical community gained more experience with the fight against COVID-19, the above directive was cancelled and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) published the document ESC guidance during the COVID-19 pandemic, which stated that: “The maximum delay from the STEMI diagnosis to the reperfusion of 120 min should remain the goal. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention remains the reperfusion therapy of choice, if feasible within this time frame and performed in facilities approved for the treatment of COVID-19 patients in a safe manner for healthcare providers and other patients” [

7]. Thrombolytic therapy in SCAD may cause hematoma expansion and dissection progression and in some case reports is associated with adverse outcomes [

5,

27,

28]. Notwithstanding, there is recent evidence from the Canadian SCAD Study, that thrombolysis may not lead to worse outcomes in STEMI patients with SCAD comparing patients who received thrombolysis with those who did not [

29]. However, these findings must be interpreted with caution until solid evidence arises.

3.4. Optimal antithrombotic therapy in SCAD patients with concomitant COVID-19 infection

Antithrombotic therapy is debatable in SCAD, due to the lack of evidence from large, randomized trials. Currently, a proposed algorithm recommends DAPT for at least 2 to 4 weeks after SCAD and then continue low-dose ASA alone for a total of 3 to 12 months, encompassing the timeframe for SCAD healing [

5]. Anticoagulation once SCAD is diagnosed is usually discontinued, due to theoretical concerns of extension of the dissection, unless there is apparent intraluminal thrombus or other indications for systemic anticoagulation [

5]. The coexistence of COVID-19 infection in our patient further complicated our decision regarding antithrombotic strategy. We chose to administer a single antiplatelet agent (ASA) along with rivaroxaban 10mg once daily for 35 days post discharge. The rationale was the fact that our patient had increased risk for thromboembolic events (IMPROVE score>2). According to one randomized trial, in patients at high risk discharged after hospitalization due to COVID-19, thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban 10 mg/day for 35 days improved clinical outcomes compared with no extended thromboprophylaxis [

25]. In our opinion, the increased risk of thromboembolism in our patient outweighed the potential risk of extending the dissection with the use of anticoagulants. In the case report of Papanikolaou et al., the authors also use DAPT plus anticoagulant, with no other apparent reason and no adverse events are reported [

13]. Furthermore, Kireev et al. treated their patient with DAPT and intravenous unfractionated heparin despite the presence of SCAD [

10]. Finally, Pettinato et al. [

11], and Bashir et al. [

21], due to the occurrence of apical thrombus used ASA, clopidogrel plus warfarin, and clopidogrel plus warfarin respectively, with no adverse events reported. There is a lack of data regarding the best treatment after SCAD, hence raises the need for future studies designed to investigate the optimal antithrombotic treatment after SCAD, especially in the context of thrombotic conditions, including COVID-19 infection.

4. Conclusions

Acute cardiac injury is commonly encountered in the setting of COVID-19 and is associated with greater disease severity and mortality [

3]. The underlying cardiac pathology is widely variable, and SCAD may represent a cause. Thus, SCAD should be considered in COVID-19 patients with ACS, and in the case of STEMI, an early angiographic evaluation, if feasible, rather than thrombolysis performed, to avoid potential adverse events of the latter in the setting of SCAD. Currently, there are no clear guidelines on how to manage this subgroup of patients with SCAD and COVID-19, especially the antithrombotic treatment, considering the higher rate of thromboembolism in the severely diseased COVID-19 patients. The more experience we gain, even from case reports, may contribute to this direction.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shi S, Qin M, Shen B, et al. Association of Cardiac Injury with Mortality in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7). [CrossRef]

- Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, et al. Cardiovascular Implications of Fatal Outcomes of Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(7). [CrossRef]

- López-Otero D, López-Pais J, Antúnez-Muiños PJ, Cacho-Antonio C, González-Ferrero T, González-Juanatey JR. Association between myocardial injury and prognosis of COVID-19 hospitalized patients, with or without heart disease. CARDIOVID registry. Rev Española Cardiol (English Ed. 2021;74(1). [CrossRef]

- Akhmerov A, Marbán E. COVID-19 and the Heart. Circ Res. Published online May 8, 2020:1443-1455. [CrossRef]

- Hayes SN, Tweet MS, Adlam D, et al. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(8). [CrossRef]

- Hayes SN, Kim CESH, Saw J, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: Current state of the science: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(19). [CrossRef]

- ESC. ESC Guidance for the Diagnosis and Management of CV Disease during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur Heart J. Published online 2020.

- Adlam D, Alfonso F, Maas A, Vrints C. European Society of Cardiology, acute cardiovascular care association, SCAD study group: a position paper on spontaneous coronary artery dissection. In: European Heart Journal. Vol 39. ; 2018. [CrossRef]

- Pine AB, Meizlish ML, Goshua G, et al. Circulating markers of angiogenesis and endotheliopathy in COVID-19. Pulm Circ. 2020;10(4). [CrossRef]

- Kireev K, Genkel V, Kuznetsova A, Sadykov R. Multivessel spontaneous coronary artery dissection in a patient after mild COVID-19: A case report. SAGE Open Med Case Reports. 2020;8:2050313X2097598. [CrossRef]

- Pettinato AM, Ladha FA, Zeman J, Ingrassia JJ. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection Following SARS-CoV-2-Associated Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome. Cureus. 2022;14(7):2-7. [CrossRef]

- Kumar K, Vogt JC, Divanji PH, Cigarroa JE. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection of the left anterior descending artery in a patient with COVID-19 infection. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;97(2):E249-E252. [CrossRef]

- Papanikolaou J, Alharthy A, Platogiannis N, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection in a patient with COVID-19. Coron Artery Dis. 2021;32(4):354-355. [CrossRef]

- Gasso LF, Maneiro Melon NM, Cebada FS, Solis J, Tejada JG. Multivessel spontaneous coronary artery dissection presenting in a patient with severe acute SARS-CoV-2 respiratory infection. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(32):3100-3101. [CrossRef]

- Courand PY, Harbaoui B, Bonnet M, Lantelme P. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection in a Patient With COVID-19. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13(12):e107-e108. [CrossRef]

- Albiero R, Seresini G, Liga R, et al. Atherosclerotic spontaneous coronary artery dissection (A-SCAD) in a patient with COVID-19: Case report and possible mechanisms. Eur Hear J - Case Reports. 2020;4(FI1):1-6. [CrossRef]

- Emren ZY, Emren V, Özdemir E, Karagöz U, Nazli C. Spontaneous right coronary artery dissection in a patient with COVID-19 infection: A case report and review of the literature. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2021;49(4):334-338. [CrossRef]

- Aparisi Á, Ybarra-Falcón C, García-Granja PE, Uribarri A, Gutiérrez H, Amat-Santos IJ. COVID-19 and spontaneous coronary artery dissection: Causality? REC Interv Cardiol. 2021;3(2):141-143. [CrossRef]

- LEWARS J, MOHTA A, HL LAL H. Case Report of Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection in a Patient Positive for Covid-19. Chest. 2022;162(4):A283. [CrossRef]

- Shah N, Shah N, Mehta S, Murray E, Grodzinsky A. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection (SCAD) in an Atypical Patient Without Risk Factors and Prior Asymptomatic COVID-19 Infection. Cureus. 2023;2023(6):1-6. [CrossRef]

- Bashir H, Muhammad Haroon D, Mahalwar G, Kalra A, Alquthami A. The Coronavirus Double Threat: A Rare Presentation of Chest Pain in a Young Female. Cureus. 2023;8(4):8-12. [CrossRef]

- Cannata S, Birkinshaw A, Sado D, Dworakowski R, Pareek N. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection after COVID-19 infection presenting with ST segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(48):4602. [CrossRef]

- AHMAD F, AHMED A, RAJENDRAPRASAD S, LORANGER A, VIVEKANANDAN R, MOORE D. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: a Rare Sequela of Covid-19. Chest. 2021;160(4):A94-A95. [CrossRef]

- ansari.pdf.

- Ramacciotti E, Barile Agati L, Calderaro D, et al. Rivaroxaban versus no anticoagulation for post-discharge thromboprophylaxis after hospitalisation for COVID-19 (MICHELLE): an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2022;399(10319):50-59. [CrossRef]

- Bu J, Chen M, Cheng X, et al. [Consensus of Chinese experts on diagnosis and treatment processes of acute myocardial infarction in the context of prevention and control of COVID-19 (first edition)]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2020;40(2):147-151. [CrossRef]

- Ndao SCT, Zabalawi A, Ka MM, et al. Sudden Cardiac Death Following Thrombolysis in a Young Woman with Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: A Case Report. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22(1):e931683-1. [CrossRef]

- Shamloo BK, Chintala RS, Nasur A, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: Aggressive vs. conservative therapy. J Invasive Cardiol. 2010;22(5).

- Mcalister C, Samuel R, Alfadhel M, et al. TCT-21 Thrombolysis in Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: Angiographic Findings and Clinical Outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(19):B10. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).