Submitted:

28 November 2023

Posted:

29 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Seed production and storage

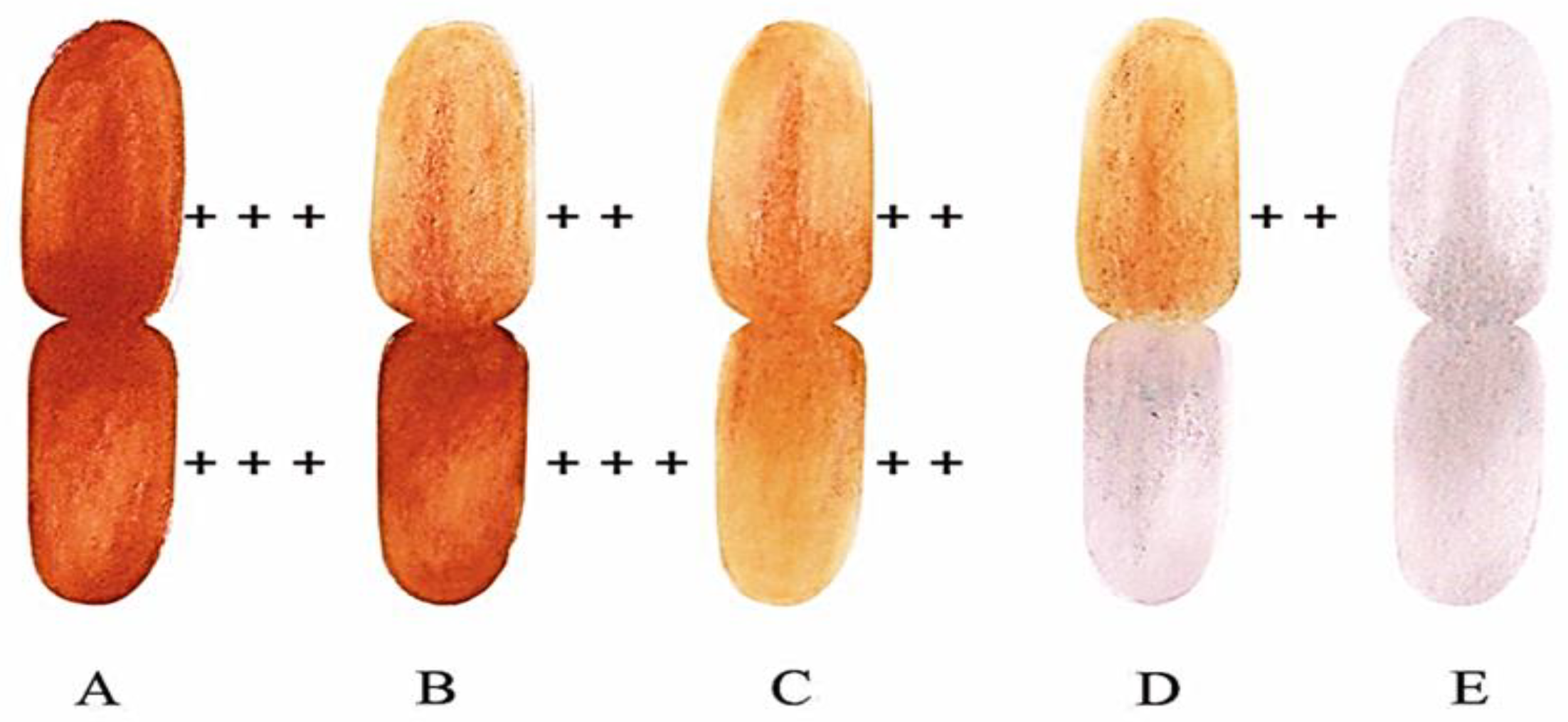

2.2. Viability test

2.3. Treatments

2.4. Extraction of lipids

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results and Discussion

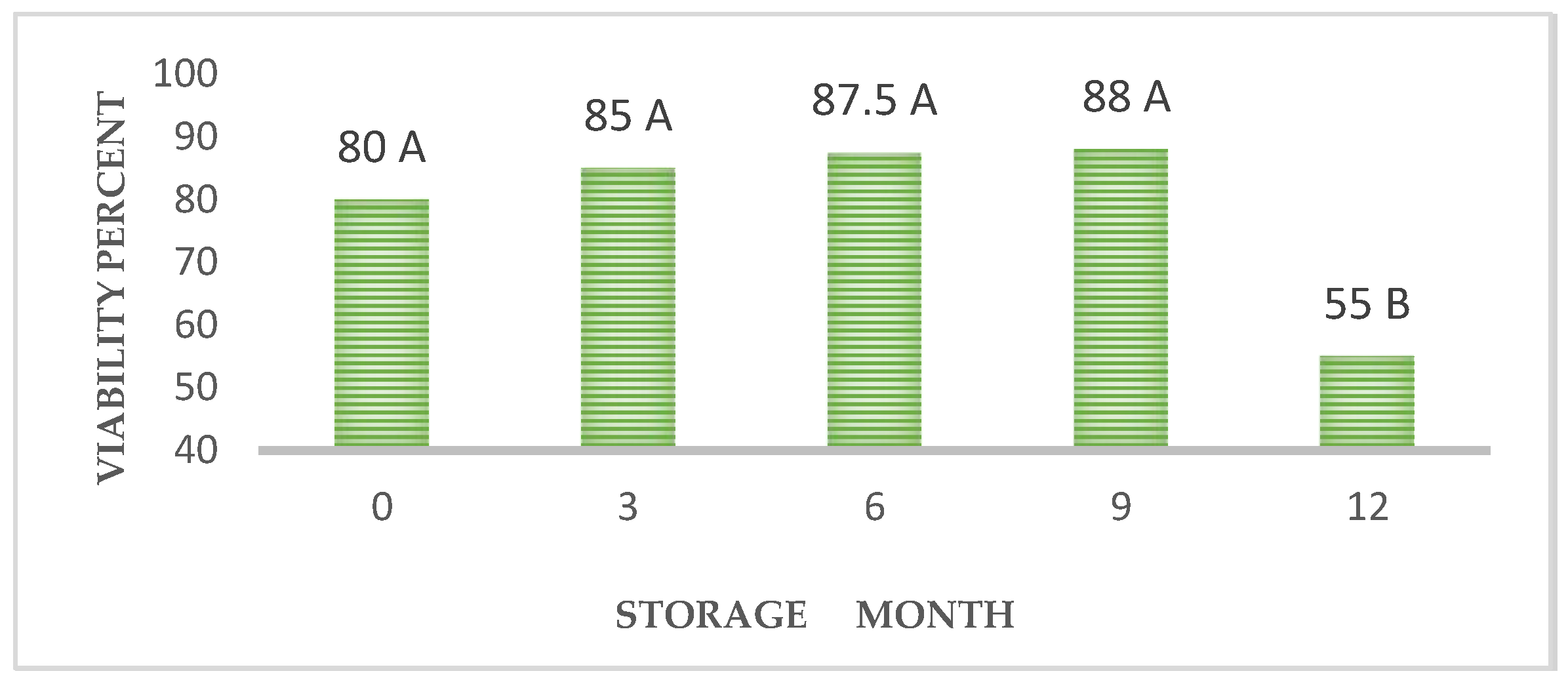

3.1. Viability

3.2. Germination

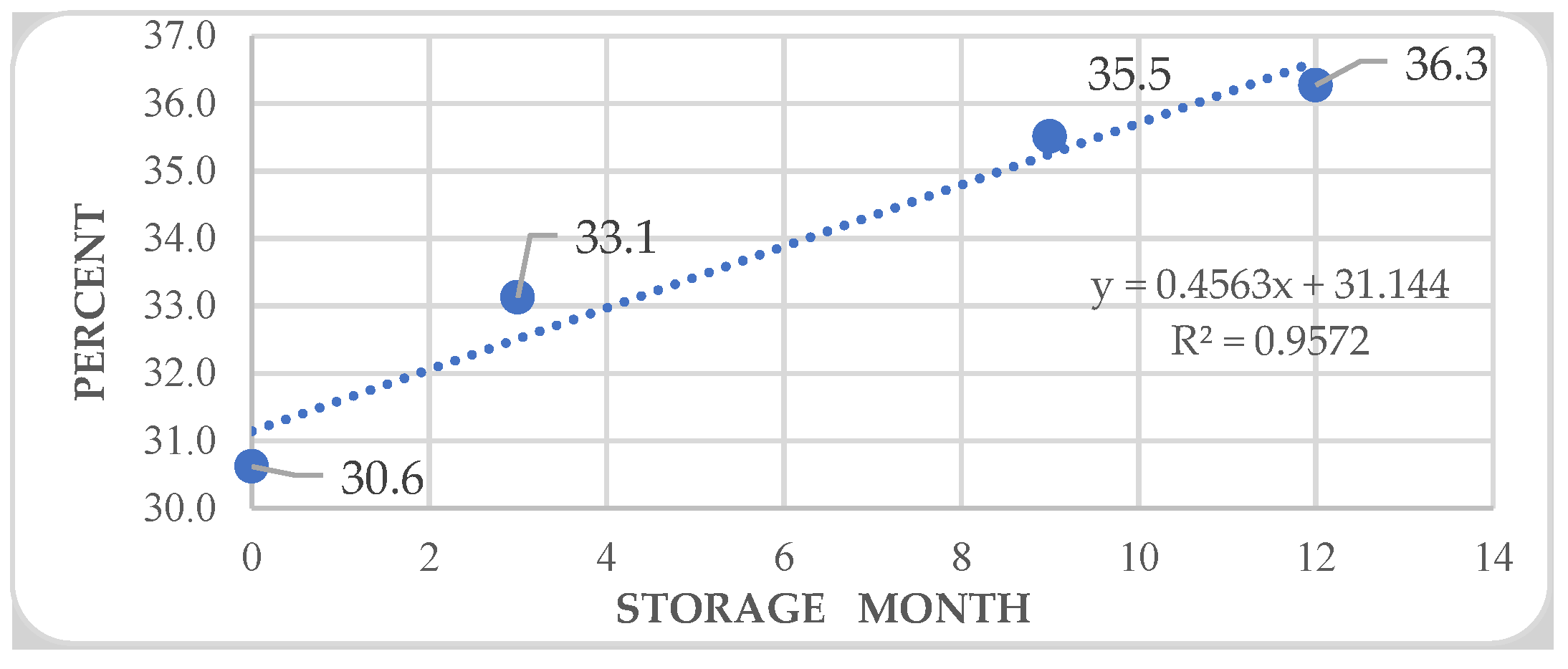

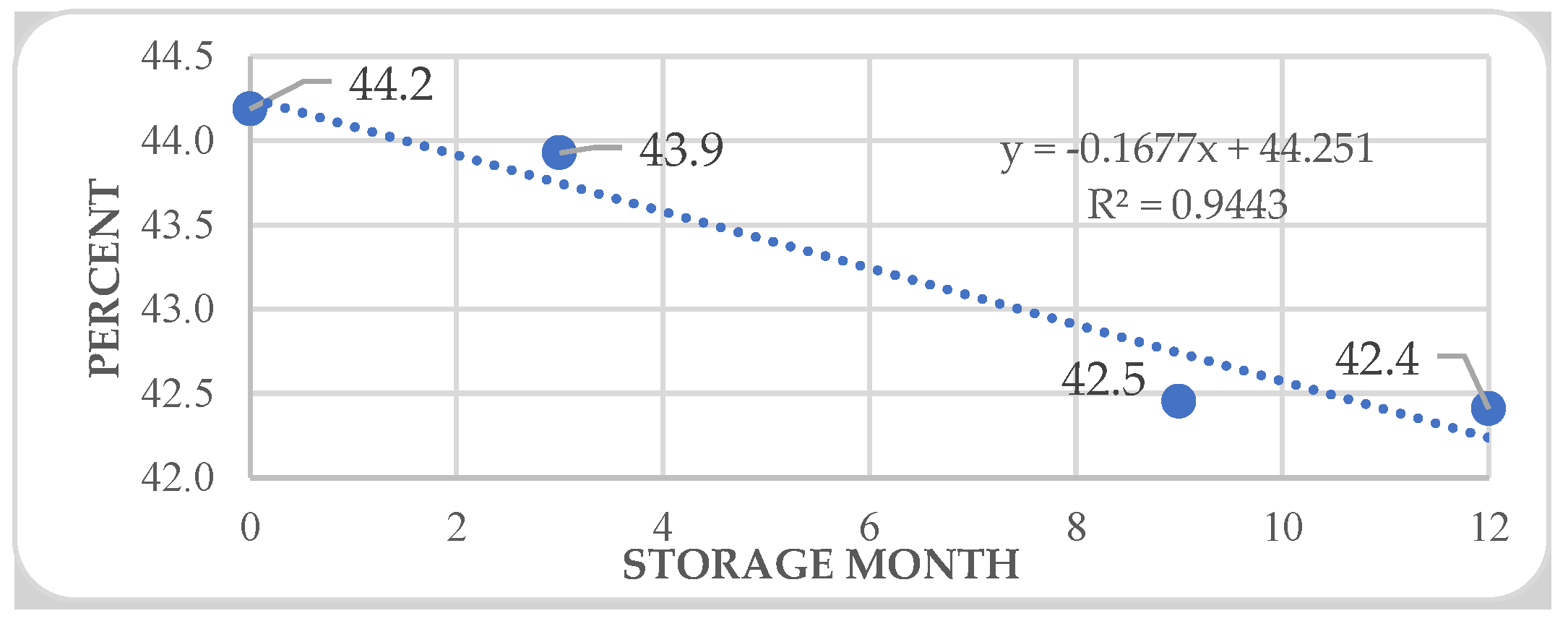

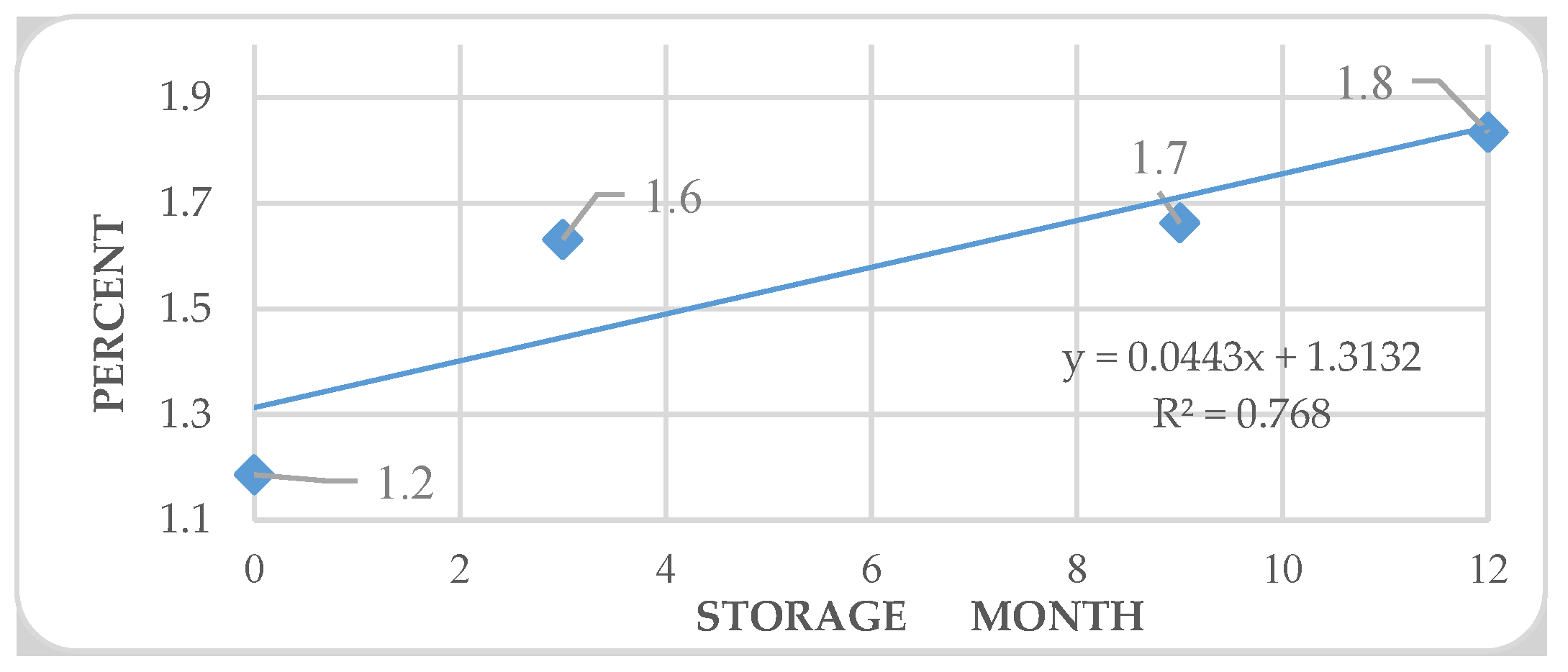

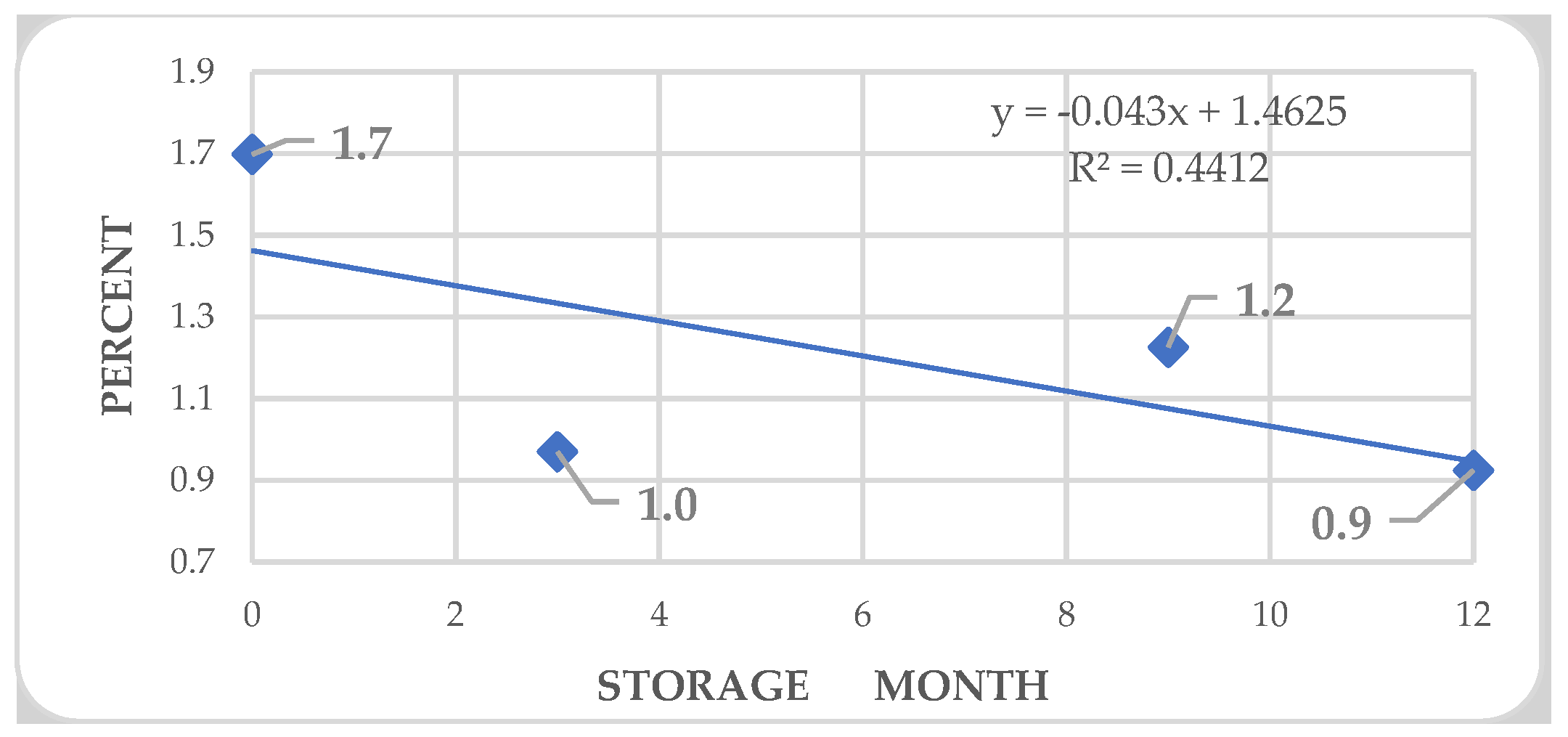

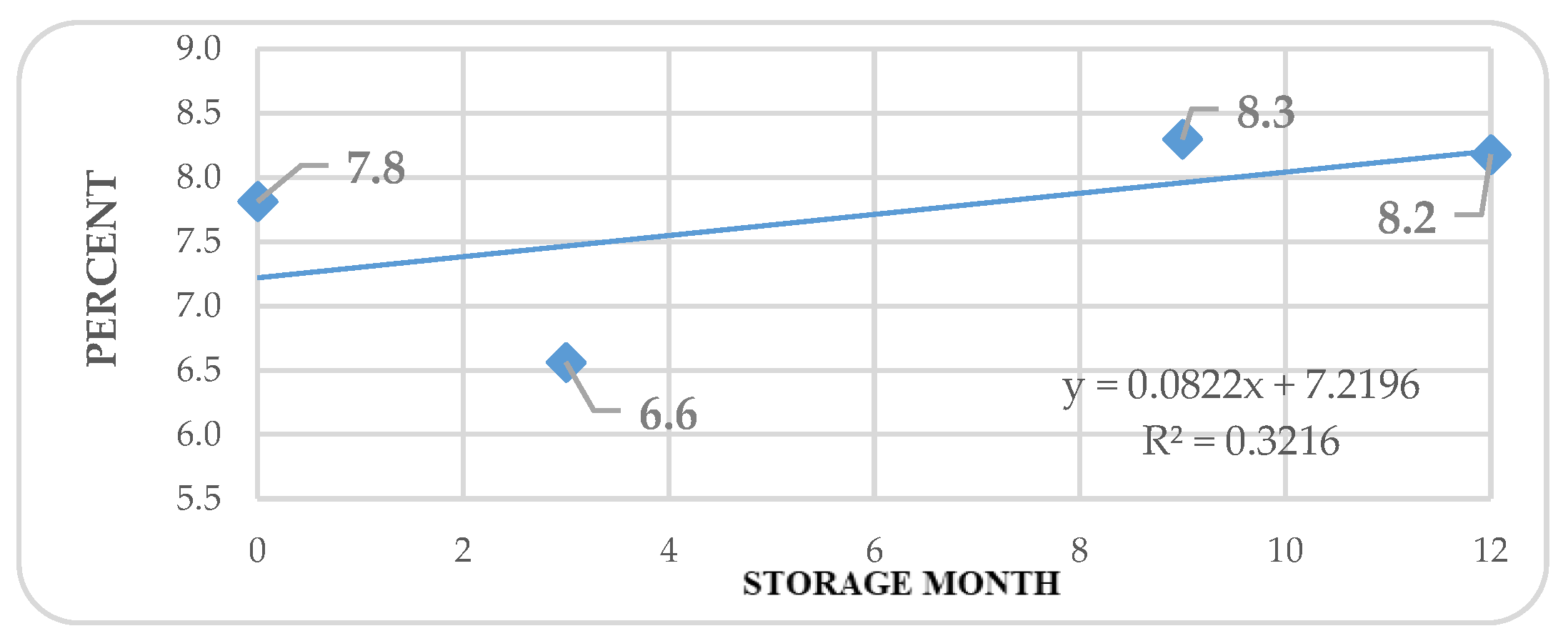

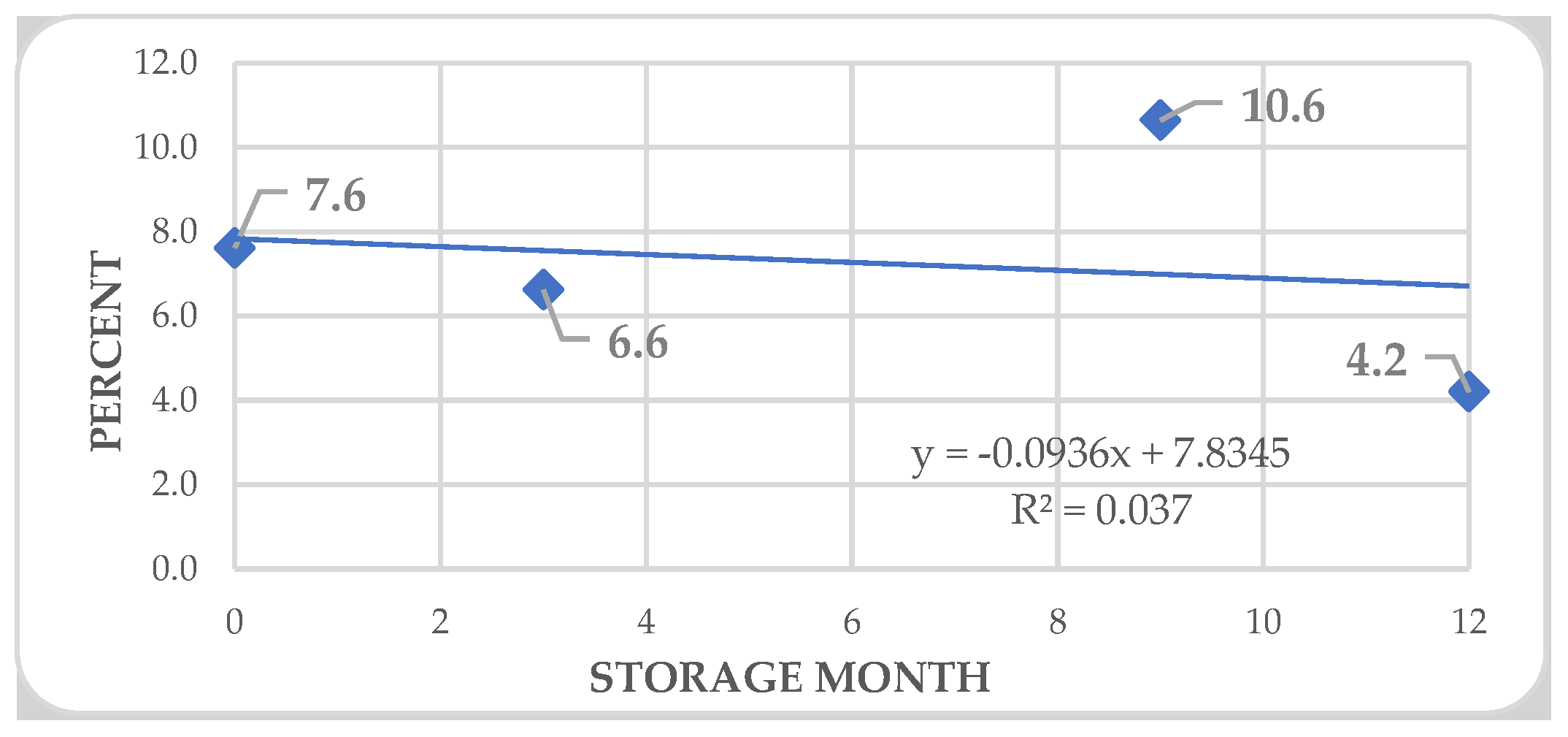

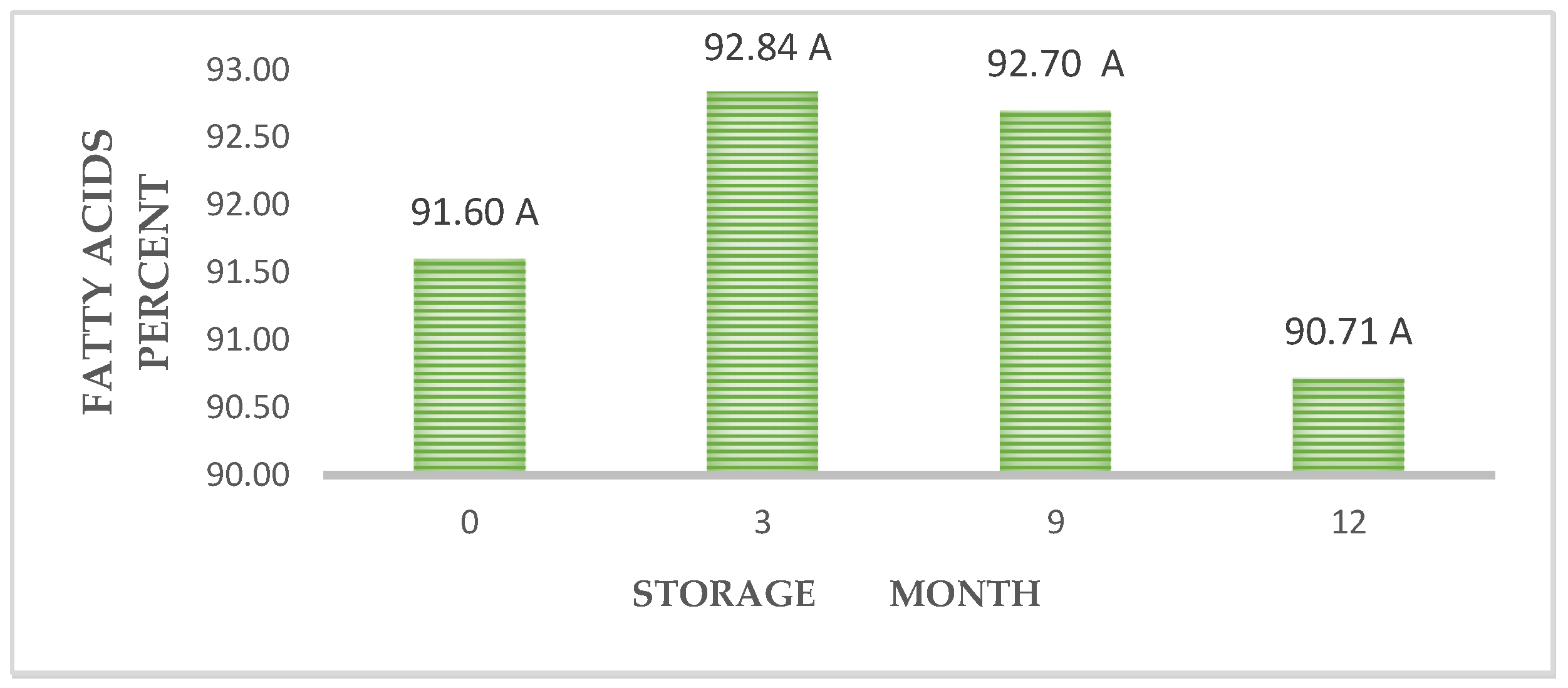

3.3. Fatty acids content

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- LI Z.; GAO Y.; ZHANG Y.; LIN C.; GONG D.; GUAN Y.; HU J. Reactive oxygen species and gibberellin acid mutual induction to regulate tobacco seed Germination. Frontiers Plant Science, 2018, 9, 1279. [CrossRef]

- MATILLA, A. Germinación y dormición de las semillas. En Fundamentos de Fisiología Vegetal. Azcón-Bieto, J.; Talón, M.. McGraw-Hill Interamericana. Madrid, España, 2000; págs. 435-450.

- SANO, N.; RAJJOU, L.; NORTH, H. M.; DEBEAUJON, I.; MARION-POLL, A.; SEO, M. Staying alive: molecular aspects of seed longevity. Plant and Cell Physiology, 2015, 57, 660-674. [CrossRef]

- COSTA, M. C. D.; COOPER, K.; HILHORST, H. W.; FARRANT, J. M. Orthodox seeds and resurrection plants: Two of a kind. Plant physiology, 2017, 175, 589-599. [CrossRef]

- HOLDSWORTH, M. J.; BENTSINK, L.; SOPPE, W. J. Molecular networks regulating Arabidopsis seed maturation, after-ripening, dormancy and germination. New Phytologist, 2008, 179, 33-54. [CrossRef]

- BASKIN, C. C.; BASKIN, J. M. Seeds: ecology, biogeography, and evolution of dormancy and germination. 2a ed; Elsevier, 2014; 14.

- FOGLIANI, B.; GATEBLÉ, G.; VILLEGENTE, M. FABRE, L.; KLEIN, N.; ANGER, N.; BASKIN, C. C.; SEUTT, C. P. The morphophysiological dormancy in Amborella trichopoda seeds is a pleisiomorphic trait in angiosperms. Annals of Botany, 2017, 119, 581-590. [CrossRef]

- CRUZ, E.; BARROS, H. Germinação de sementes de espécies amazônicas: ucuúba [Virola surinamensis (Rol. ex Rottb.) Warb]; Embrapa: Amazônia Oriental, Brasil 2016; 4.

- DA SILVA, E. A.; DE MELO, D. L.; DAVIDE, A. C., DE BODE, N.; ABREU, G. B.; FARIA, J. M.; HILHORST, H. W. Germination ecophysiology of Annona crassiflora seeds. Annals of botany, 2007, 99, 823-830. [CrossRef]

- VIDAL-LEZAMA, E.; MARROQUÍN-ANDRADE, L.; GÓMEZ, R. S. Efecto del almacenamiento y tratamientos pregerminativos en semillas de Annona muricata L., Annona diversifolia Saff. y Annona spp. Proc. Inter. Soc. for Trop. Hort, 2008, 52, 203-209.

- GONZÁLEZ-ESQUINCA, A. R.; DE-LA-CRUZ-CHACÓN, I.; DOMÍNGUEZ-GUTÚ, L. M. Dormancy and germination of Annona macroprophyllata (Annonaceae): the importance of the micropylar plug and seed position in the fruits. Botanical Sciences, 2015, 93, 509-515. [CrossRef]

- FERREIRA, G.; DE-LA-CRUZ-CHACÓN, I.; GONZÁLEZ-ESQUINCA, A. R. Overcoming seed dormancy in Annona macroprophyllata and Annona purpurea using plant growth regulator. Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura, 2016, 38, e-234. [CrossRef]

- FENNER, M.; THOMPSON, K. The ecology of seeds. Cambridge University Press New York, 2005; 250.

- FINCH-SAVAGE, W. E.; AND LEUBNER-METZGER, G. Seed dormancy and the control of germination. New Phytologist, 2006, 171, 501-523. [CrossRef]

- YANO, R.; KANNO, Y.; JIKUMARU, Y.; NAKABAYASHI, K.; KAMIYA, Y.; NAMBARA, E. CHOTTO1, a putative double APETALA2 repeat transcription factor, is involved in ABA-mediated repression of gibberellin biosynthesis during seed germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol, 2009, 151, 641-654.

- TAIZ, L. AND ZEIGER, E. Plant Physiology. 5a ed.; Sinauer Associates Inc., Sunderland, UK, 2010; 728.

- BEWLEY, J.; M. BLACK. Seeds: Physiology of Development and Germination. New York and London, Plenum Press, 1994; 445.

- GÓMEZ-CASTAÑEDA, J. A.; RAMÍREZ, H.; BENAVIDES-MENDOZA, A.; ENCINA-RODRÍGUEZ, I. Germination and seedling development of soncoya (Annona purpurea Moc & Sessé) in relation to gibberellins and abscisic levels. Revista Chapingo Serie Horticultura, 2003, 9, 243-253.

- FERREIRA, G. Reguladores vegetais na superação da dormência, balanço hormonal e degradação de reservas em sementes de Annona diversifolia Saff. e A. purpurea Moc. & Sessé ex Dunal (Annonaceae). Tese (Livre-Docência). Universidade Estadual Paulista, Instituto De Biociências. Campus de Botucatu, Sao Paulo, Brasil; 2011.

- BASKIN, C. C.; BASKIN, J. M. Seeds. Ecology, Biogeography, and Evolution of Dormancy and Germination. Academic Press: San Diego, California, 1998; 666.

- ZIENKIEWICZ, A.; ZIENKIEWICZ, K.; REJÓN, J. D.; DE DIOS ALCHÉ, J., CASTRO, A. J.; RODRÍGUEZ-GARCÍA, M. I. Olive seed protein bodies store degrading enzymes involved in mobilization of oil bodies. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2013, 65, 103-115. [CrossRef]

- MURPHY, D. J. The dynamic roles of intracellular lipid droplets: from archaea to mammals. Protoplasma, 2012, 249, 541-585. [CrossRef]

- POXLEITNER, M.; ROGERS, S. W.; SAMUELS, A. L.; BROWSE, J.; ROGERS J. C. A role of caleosin in degradation of oil-body storage lipids during seed germination. The Plant Journal, 2006, 47, 917-933. [CrossRef]

- BEWLEY, J. D.; BLACK, M. Physiology and biochemistry of seeds in relation to germination: volume 2: viability, dormancy, and environmental control. Springer Science & Business Media, 1982; 339.

- AZCÓN-BIETO, J.; TALÓN, M. Fundamentos de Fisiología Vegetal. McGraw-Hill Interamericana: Madrid, España; 2000; 522.

- ZHAO, M.; ZHANG, H.; YAN, H.; QIU, L.; BASKIN, C. C. Mobilization and role of starch, protein, and fat reserves during seed germination of six wild grassland species. Frontiers Plant Science, 2018, 9, 234. [CrossRef]

- INTERNATIONAL SEED TESTING ASSOCIATION. International Rules for Seed Testing. ISTA, Zurich, Suiza, 2013.

- SAS Institute Inc., SYSTEM 2000® Software: Product Support Manual, Version 1, First edition, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC; 2000; 293.

- VIDAL-LEZAMA, E.; VILLEGAS-MONTER, A.; VAQUERA-HUERTA, H.; ROBLEDO-PAZ, A.; MARTÍNEZ-PALACIOS, A.; FERREIRA, G. Morphometry of chincuya seeds (Annona purpurea Moc. & Sessé ex Dunal) and embryonic growth under dry warm storage. Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura [online], 2023, 45, e-042.

- TAVEIRA J. H. S.; ROSA S. D. V. F.; BORÉM F. M.; GIOMO G. S.; SAATH, R. Perfis proteicos e desempenho fisiológico de sementes de café submetidas a diferentes métodos de processamento e secagem. Pesq. Agropec. Bras, 2012, 47, 1511-1517.

- FERREIRA, G.; GONZALEZ-ESQUINCA, A. R.; DE-LA-CRUZ-CHACÓN, I. Water uptake by Annona diversifolia Saff. and A. purpurea Moc. & Sessé ex Dunal seeds (Annonaceae). Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura, 2014, 36, 288-295.

- FERREIRA, G.; DE-LA-CRUZ-CHACÓN, I.; BOARO, C. S. F.; BARON, D.; LEMOS, E. E. P. D. Propagation of Annonaceous plants. Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura, 2019, 41, e-500. [CrossRef]

- BAZIN, J.; BATLLA, D.; DUSSERT, S.; EL-MAAROUF-BOUTEAU, H.; BAILLY, C. Role of relative humidity, temperature, and water status in dormancy alleviation of sunflower seeds during dry after-ripening. Journal of Experimental Botany 2010, 62, 627-640. [CrossRef]

- BAILLY, C. Active oxygen species and antioxidants in seed biology. Seed Science Research, 2004. 14, 93-107. [CrossRef]

- HALLETT B. P.; BEWLEY J. D. Membranes and seed dormancy: beyond the anaesthetic hypothesis. Seed Science Research, 2002, 12, 69-82. [CrossRef]

- SKODA, B.; MALEK, L. Dry pea seed proteasome. Plant physiology,1992, 99, 1515-1519. [CrossRef]

- BORGHETTI, F.; NAKAMURA, N. F.; MARTINS DE SÁ, C. Possible involvement of proteasome activity in ethylene induced germination of dormant sunflower embryos. Brazilian Journal of Plant Physiology, 2002, 14, 125-131.

- CHATROU, L.W. The Annonaceae and the Annonaceae project: a brief overview of the state of affairs. Acta Hortic., 1999, 497, 43-58. [CrossRef]

- FORBIS, T. A.; FLOYD, S. K.; AND DE QUEIROZ A. The evolution of embryo size in angiosperms and other seed plants: implications for the evolution of seed dormancy. Evolution, 2002, 56, 2112-25.

- SAUTU, A.; BASKIN, J. M.; BASKIN, C. C.; DEAGO, J.; CONDIT, R. Classification and ecological relationships of seed dormancy in a seasonal moist tropical forest, Panama, Central America. Seed Science Research, Cambridge, 2007, 17, 127-140. [CrossRef]

- DUKE, J. A. On tropical tree seedlings I. Seeds, seedlings, systems, and systematics. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, Missouri, 1969, 56, 125-161.

- RUBIO DE CASAS, R., WILLIS, C. G., PEARSE, W. D., BASKIN, C. C., BASKIN, J. M.; CAVENDER-BARES, J. Global biogeography of seed dormancy is determined by seasonality and seed size: a case study in the legumes. New Phytologist, 2017, 214, 1527-1536.

- PÉREZ-AMADOR, M. C.; GONZÁLEZ-ESQUINCA, A.; GARCÍA-ARGAEZ, A.; BRATOEFF, E.; LABASTIDA, C. Oil composition and flavonoid profiles of the seeds of three Annona species. Phyton., 1997, 61, 77-80.

- ABBADE, L. C.; TAKAKI, M. Biochemical and physiological changes of Tabebuia roseoalba (Ridl.) Sandwith (Bignoniaceae) seeds under storage. Journal of Seed Science 2014, 36, 100-107. [CrossRef]

- SUN, W. Q. State and phase transition behaviors of Quercus rubra seed axes and cotyledonary tissues: Relevance to the desiccation sensitivity and cryopreservation of recalcitrant seeds. Cryobiol., 1999, 38, 372-385. [CrossRef]

- GÓMEZ T. J.; JASSO-MATA J. J.; VARGAS-HERNÁNDEZ J. J.; SOTO-HERNÁNDEZ R. M. Deterioro de semilla de dos procedencias de Swietenia macrophylla King., bajo distintos métodos de almacenamiento. Ra Ximhai, 2006, 2, 223-239.

- VIDAL-LEZAMA, ELOÍSA; VILLEGAS-MONTER, ÁNGEL; VAQUERA-HUERTA, HUMBERTO; ROBLEDO-PAZ, ALEJANDRINA; MARTÍNEZ-PALACIOS, ALEJANDRO. Annona purpurea Moc. & Sessé ex Dunal especie nativa de México, subutilizada. AgroProductividad, 2019, 12, 9-15.

- SOLÍS-FUENTES, J. A.; AMADOR-HERNÁNDEZ, C.; HERNÁNDEZ-MEDEL, M. R.; DURÁN-DE-BAZÚA, M. C. Caracterización fisicoquímica y comportamiento térmico del aceite de "almendra" de guanábana (Annona muricata, L). Grasas y aceites, 2010, 61, 58-66.

- BRANCO, P. C.; CASTILHO, P. C.; ROSA, M. F.; FERREIRA, J. Characterization of Annona cherimola Mill. seed oil from Madeira Island: a possible biodiesel feedstock. Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society, 2010, 87, 429-436. [CrossRef]

- MARROQUÍN-ANDRADE, L.; CUEVAS-SÁNCHEZ, J. A.; GUERRA-RAMÍREZ, D.; REYES, L.; REYES-CHUMACERO, A.; REYES-TREJO, B. Proximate composition, mineral nutrient and fatty acids of the seed of ilama, Annona diversifolia Saff. Scientific Research and Essays, 2011, 6, 3089-3093.

- YATHISH, K. V.; OMKARESH, B. R.; SURESH, R. Biodiesel production from custard apple seed (Annona squamosa) oil and its characteristics study. IJERT, 2015, 10, 2, 1938-1942.

| STORAGE DURATION (months) |

GERMINATED SEEDS (%) |

LATENTS SEEDS (%) |

DEATH SEEDS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 26.12 B | 59.13 A | 14.75 C |

| 3 | 52.16 A | 25.50 B | 22.33 BC |

| 6 | 65.62 A | 18.13 B | 16.25 C |

| 9 | 13.75 BC | 43.13 AB | 43.12 B |

| 12 | 2.00 C | 19.50 B | 78.50 A |

| DMS | 14.48 | 28.91 | 21.52 |

| TREATMENT | GERMINATION (%) |

LATENT SEEDS (%) |

DEATH SEEDS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gibberellic acid | 40.25 A | 34.54 B | 25.19 A |

| Control | 17.80 B | 52.25 A | 29.93 A |

| DMS | 5.456 | 10.896 | 8.109 |

| FATTY ACID | SOURSOUP (%) (A. muricata) Z |

CHERIMOLA (%) (A. cherimola) Y |

ILAMA (%) (A. macroprophyllata) X |

SUGAR APPLE (%) (A. squamosa) W |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palmitic | 25.5 | 19.99 | 16.4 | 17.79 |

| Palmitoleic | 1.5 | -- | --- | -- |

| Estearic | 6.0 | 4.16 | 5.22 | 4.29 |

| Oleic | 39.5 | 38.58 | 70.42 | 39.72 |

| Linoleic | 27.0 | 36.97 | 7.97 | 29.13 |

| Arachidic | ---- | -- | -- | 1.06 |

| Relation U:S U | 2.44 | 2.21 | 3.62 | 2.97 |

| PERCENT OF FATTY ACIDS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SEED CONDITION |

Palmitic | Palmitoleic | Stearic | Oleic | Arachidic | Linoleic | TOTAL |

| Recently extracted without incubating (intact) |

30.62 Az |

1.71 A |

7.81 A |

47.05 A |

1.69 A |

12.75 A |

98.15 A |

| Recently extracted incubated (embedded) latent | 29.61 A | 1.18 A | 6.03 B | 44.19 A | 0.98 A | 7.62 A | 91.60 B |

| DMS | 9.00 | 0.82 | 1.60 | 6.17 | 0.77 | 11.51 | 5.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).