1. Introduction

Fisheries support about 600 million people's livelihoods and supply 214 million tons of fish and 17% of animal protein consumption for the world's population [

1,

2]. Globally, fish, among other aquatic foods, are high-demand products, reaching a production value of USD 424 billion in 2020 and substantially contributing to many countries' Gross Domestic Product (GDP), alleviating poverty and fostering nutritional security [

2]. In Nigeria, fish is a vital source of protein, and fisheries is a significant sector of the economy, contributing approximately 5.40% of the country's GDP [

3] Adebesin 2011. A country report by FAO [

4] states that small-scale fisheries dominate fish production in Nigeria by contributing over 80% of Nigeria's total domestic fish production. This small-scale fishery is prominent along the Nigerian coast and, especially, the Ibeju-Lekki coastline, which is about 75km of the total 180km of the Lagos State coastline, contributing the highest percentage of fish catch among other coastal sections [

5]. It is a multi-species fishery with a dominance of

Sardinella spp and

Caranx spp [

6,

7,

8]. Despite high catches of these species that have attracted artisanal fishers from local ethnic groups and foreign nationals, there is limited knowledge of the effect of anthropogenic factors on the abundance indices of the

Sardinella spp on the Lagos coastline, having one of the highest economic values to the fisher folks [

7].

Sardinella maderensis (Lowe, 1838) is commonly known as Madeiran sardinella or flat Sardinella and locally called

Sawa. It is a schooling pelagic fish from the

Clupeidae family [

9]. It has an elongated body with variable depth, black or blue/green colour and silvery flanks. Its size is usually 20-25cm and inhabits the near-surface of coastal waters, shoaling at the surface or bottom down to 50m. It feeds on various small planktonic invertebrates, fish larvae, and phytoplankton.

Sardinella maderensis is presently found in 43 countries worldwide, with Africa dominating the global fish catch. Using a ten-year average (2008-2017), Nigeria is the third highest contributor of

S. maderensis, with 9% of the species' global catches [

10].

S. maderensis dominates small-scale marine fisheries and is the main species captured in Nigeria's coastal waters, providing livelihood sources, nutrition and income for several poor coastal communities in Nigeria. [

4].

Sardinella maderensis is one of Nigeria's most abundant and economically valuable coastal pelagic species [

11,

12] and Ibeju-Lekki communities. It is also the most abundant and economically valuable fish species, accounting for 69% of the fish caught by artisanal fishers in the locality [

7]. Despite its importance, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) rates

Sardinella maderensis as a vulnerable species [

12].

In the last few decades, anthropogenic activities have increased along the Nigerian coastline due to rapid population growth linked to industrialisation [

13,

14]. This growth has resulted in significant human pressures on marine ecosystems and biological stocks [

15]. Massive industrial activities and urban developments have threatened the pelagic fish populations due to the degradation of coastal habitats for which

Sardinella maderensis is endemic [

12,

16]. Moreover, industrial developments associated with the Lekki Free Trade Zone, dredging and land reclamation for the construction of the seaport and the petrochemical refinery have destroyed mangroves and coastal habitats that are crucial to

S. maderensis [

15]. Polluting effluents threaten water quality,

petroleum hydrocarbons and heavy metals from industries, which causes a decline in ecosystem services and environmental sustainability [

17,

18,

19]

. In addition, inefficient fishing standards and illegal and unregulated fishing have negatively impacted the fishery's sustainability, leading to significant changes in species composition, decreases in catch, and depletion [

20,

21]. In it all, escalating anthropogenic pressures threaten the sustainability of small-scale fisheries and the livelihood of Ibeju-Lekki communities.

The effects of anthropogenic activities on S. maderensis fisheries have been investigated by a few studies in Nigerian waters, emphasising the impacts on the broader coastal fisheries in Nigeria [

22,

23]. Hence, there is limited knowledge on how increasing anthropogenic activities affect

S. maderensis fisheries and the livelihoods of fisher folks in the coastal communities of Ibeju-Lekki. Bridging the knowledge gap of the effects of anthropogenic activities on S. maderensis fisheries in Ibeju-lekki is imperative for building fishers' resilience and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 1, 2, and 14. Moreover, findings from the study will provide empirical evidence on how anthropogenic activities affect

S.maderensis fisheries and the fishers' livelihood in Nigeria. The outcome will inform policy interventions to mitigate pollution, habitat degradation and overexploitation, promoting resilience in small-scale fisheries that will sustain livelihood and conserve biodiversity in Nigeria.

In its objectives, the study seeks to confirm the identity of the Sardinella species exploited in Ibeju-Lekki fisheries using genetic and morphological techniques; analyse the land use and land cover changes over time using geospatial analysis; assess water pollution levels and habitat degradation through water quality analysis. Anthropogenic factors were correlated with S. maderensis abundance to examine what relationships exist. The fisherfolks' perceptions of anthropogenic impact and vulnerability were elucidated, and strategies for mitigating anthropogenic threats and promoting resilient small-scale fisheries were recommended for adoption.

2. Materials and Methods

3.1. Description of the Study Area

The study area is Ibeju-Lekki, a municipality (local government area) in Lagos State, Nigeria. Lagos State lies between latitude 6°20' North to 6°40' North and long 2°45' East to 4°20' East. The Lagos coastline stretches 180 km across the Atlantic Ocean, having 22.5% of Nigeria's 853 km coastline. Although it is spatially the smallest state in Nigeria, it is the most densely populated, occupying a landmass of 3,577 sq. km., of which about 786.94 sq. km. (22%) are lagoons and creeks [

24,

25]. Ibeju-Lekki covers about 75km of the Lagos Coastline, a leading fish-producing area in Lagos State [

6,

7]. About 80 coastal and lagoon communities exist in Ibeju-Lekki, with small-scale fisheries being a significant source of livelihood (Adeosun, 2017; Omenai & Ayodele, 2014).

Figure 1.

The geographical setting of the study area: (a) Map of Africa showing Nigeria; (b) Map of Nigeria showing Lagos State; (c) Map of Lagos State showing Ibeju-Lekki.

Figure 1.

The geographical setting of the study area: (a) Map of Africa showing Nigeria; (b) Map of Nigeria showing Lagos State; (c) Map of Lagos State showing Ibeju-Lekki.

2.2. Field Survey

Field surveys were conducted to elicit responses from 30 coastal communities where

S. maderensis fishing occurs in Ibeju-Lekki. Interviews, focus group discussions (FGD) and observations were primary data collection methods used to derive perceptions of the targeted population of 1879

S. maderensis fishers. Systematic random sampling was used to select 360 fishers proportionately across the 30 communities for interviews, while 7 FGDs involving 6 to 10 fishers were conducted based on the principle of saturation [

27].

2.3. Fish Species Identification

Fish samples were collected from landing sites monthly between January 2021 and March 2022 and identified through morphological examinations conducted at the Marine Sciences Laboratory of the University of Lagos, Nigeria. Biometric features were examined on the fish species, and identification was completed using guidelines [

28,

29]. Key morphometric and meristic characteristics were examined to identify which species of Sardinella the fish samples belonged. Twelve (12) fish samples were proposed for the genetic analysis based on standards used by Ward et al. [

30], Ivanova et al. [

31] and Kim et al. [

32]. DNA was extracted from the fish fin tissues, and the cytochrome oxidase gene was sequenced using published primers [

33]. The genetic analysis was done by DNA extraction of the genomic DNA and PCR amplification using primer synthesised for forward and backward reactions. The extracted fragments were sequenced using Nimagen, BrilliantDyeTM Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit V3.1. The ABI350xl Genetic Analyser was used to analyse the purified fragments. The ab1 files generated were edited using BioEditSequence Alignment Editor version 7.2.5, and a BLAST search in NCBI was conducted to obtain the results.

2.4. Land Use and Land Cover Change Analysis

Landsat imageries were acquired from the United States Geological Surveys/Earth Resources and Observation Science (USGS/EROS) website and processed to determine the land use/land cover changes in Ibeju-Lekki coastal areas for about 36 years. Satellite mageries used in this research include Landsat TM (Thematic Mapper) for 1984, which is the base year, Landsat ETM+ (Enhanced Thematic Mapper plus) for 2002 and Landsat OLI_TIRS (Operational Land Imager and Thermal Infrared Sensors) for 2020. The research adopted three (3) temporal periods based on Landsat imageries available to conduct a 36-year multi-temporal land use change analysis from multi-spectral remote sense data for available periods (1984, 2002, 2020).

Table 1.

Spatial data and sources.

Table 1.

Spatial data and sources.

| Acquisition Date |

Satellite Number |

Sensor Type |

WRS Path/Row |

UTM Zone |

Datum |

Spatial Resolulion (M) |

Sources & Year |

| 4/1/2020 |

Landsat 8 |

OLI_TIRS |

191/55 |

31 N |

WGS84 |

30 |

USGS, 2020 |

| 28/12/2002 |

Landsat 7 |

ETM+ |

191/55 |

31 N |

WGS84 |

30 |

USGS, 2006 |

| 18/12/1984 |

Landsat 5 |

TM |

191/55 |

31 N |

WGS84 |

30 |

USGS, 1984 |

False Colour RGB composite raster imageries (Bands 4,5,1 for Landsat 7 and Bands 5,6,1 for Landsat 8) using ArcGIS Software. A subset of the composite imageries limited to the AOI (Area of Interest, 2 Kilometres buffer from the coastline) was extracted using a clip geoprocessing tool in ArcGIS (

Figure 2). The RGB composite imageries were classified utilising the ISODATA unsupervised algorithm [

34]. Imageries were synchronised with Google Earth, and ground truthing was done to validate the classification. Change detection and statistics were generated from land use/land cover change maps in TERRSET.

2.5. Water Quality Analysis

The water quality monitoring was done bi-monthly at six fishing stations from February 2021 to January 2022 to allow for an observational study of seasonal variations in a year. Samples for physicochemical parameters like salinity, temperature, dissolved oxygen, nutrients, and heavy metals analysis were collected using standard methods [

35]. Total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH) were estimated through solid-phase extraction and gas chromatography [

36]. The study used a solid phase extraction (SPE) column separation method to remove organic and polar species from the water samples. The samples were eluted, evaporated, and reconstituted. The extract was analysed for TPHs using a Gas Chromatograph fortified with a Flame ionisation detector. Heavy metal analysis involved adding nitric acid to water samples, heating, cooling, filtering, and determining metal contents using the PG 990 Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer.

2.6. Anthropogenic Factors and S. maderensis Abundance

Fishers' interview data were coded and analysed using SPSS version 25. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise fishers' perception and vulnerability. Monthly landing records for 2003 to 2019 were obtained for artisanal fisheries in Ibeju-Lekki from the Lagos State Agricultural Development Agency (LSADA) and Federal Department of Fisheries (FDF), Nigeria repositories. The monthly landing records for fifteen fish types were consistent for two landing locations in Ibeju-Lekki (Orimedu and Badore), including Sardinella. Data on fishing efforts were derived from observed primary data by calculating the fishermen's number of trips per hour. According to Arizi et al. [

37] and Stobart et al. [

38], Catch Per Unit Effort (CPUE) measures species abundance in fisheries. CPUE can be estimated by the number of fish caught (weight) per unit effort expended (time), which is proportional to the stock size[

39]. Therefore, to estimate the CPUE, monthly fish catch data were compiled from the LSADA, Federal Department of Fisheries (FDF) Nigeria, and Food & Agriculture Organization repositories from 2003 to 2019. CPUE of

S. maderensis, expressed as hours of fishing trips, were modelled against perceived anthropogenic factors using a linear regression model.

3. Results

3.1. Fish Species Identification

The morphometrics-based identification system involving external or phenotypic features, including body shape, fin rays, and meristic counts, to identify the fish species revealed that the Sardinella species exploited in Ibeju-Lekki are mainly

Sardinella maderensis (

Figure 2). The fish showed features as Whitehead [

9] and Gourene & Teguels [

40] described. It has an elongated body with a belly fairly sharply keeled, 18-23 dorsal soft rays and 17-23 anal soft rays, 70-166 lower gill rakers, upper pectoral fin rays white on the outer side, and the membrane black [

9,

28,

40,

41].

Figure 3.

Sardinella maderensis specimen

Figure 3.

Sardinella maderensis specimen

Genetic analysis using DNA barcoding also unambiguously confirms the identity of the fish species in the study area as S. maderensis

. The results of the BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool, from National Centre for Biotechnology Information

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) reflect similarities between the search and the NCBI database's biological sequences. The result derived from the analysis using the fish primer [

30] indicated that all the samples are

Sardinella maderensis with a mean percentage of 98.21% similarity to S. maderensis reference sequences in the GenBank (

Table 2). Hence, the results of the genetic analysis also confirmed that the fish samples were

S. maderensis.

3.2. Land Use and Land Cover Change

Land use change analysis of classified Landsat imageries of the AOI in Ibeju-Lekki reveals extensive changes in the coastal area over the past 36 years. Less significant changes were observed between 1984 and 2002. However, mangrove forests and cultivated lands declined by approximately 14% and 62%, respectively, between 1984 and 2020, while minor urban development increased by 48%, and land used for major urban/industrial development had a tremendous increase of about 175% (

Table 3). The analysis indicates dynamic urban growth at the Ibeju Lekki coastline, which also corroborates the claim by fishers that industrial developments, the Lekki Seaport and the petrochemical refinery have significantly destroyed coastal habitats and displaced artisanal fishers in Ibeju-Lekki. Also, other urban land uses such as residential, commercial, recreational, and institutional uses are major anthropogenic activities that have taken over the fishing fields and disrupted artisanal fishing in the study area, as seen in the 1984 to 2020 land cover change maps (

Figures 4 (a), 4(b) and 4(c)).

Figure 4.

The land use/ land cover change maps of the study area for 1984, 2002 and 2020: (a) 1984 land use/land cover classification map; (b) 2002 land use/land cover classification map; (c) 2020 land use/land cover classification map.

Figure 4.

The land use/ land cover change maps of the study area for 1984, 2002 and 2020: (a) 1984 land use/land cover classification map; (b) 2002 land use/land cover classification map; (c) 2020 land use/land cover classification map.

3.3. Water Quality and Physiochemical Parameter Analysis

The water quality results for the study period revealed that physiochemical parameters like temperature, pH, salinity and dissolved oxygen were within tolerable ranges for fish survival (

Table 4). However, total dissolved solids (TDS) and biological oxygen demand (BOD) exceeded the recommended levels, which indicates organic pollution [

3]. The nitrate (NO3) and phosphate (PO4) nutrient levels were high, indicating a higher eutrophication risk from anthropogenic activities. Additionally, the reduced quantities of Chlorophyll-a indicate a decreased abundance of food organisms for fishes.

The results of the heavy metal analysis in

Table 7 reveal that even though levels found in the study area were above the international standard limits set by USEPA (1980-2016), the levels of Lead, Cadmium, Iron, Manganese and Nickel were within national limits set by the Federal Environmental Protection Agency in Nigeria [

42]. However, Chromium exceeded national and international thresholds among all the heavy metals in ibeju-Lekki waters. Also, the Total Petroleum Hydrocarbon (TPH) analysis shows that the TPH levels were generally high across all six stations (27.56 mg/L- 3985.40 mg/L) when compared to the 10mg/l permissible limit for coastal waters in Nigeria, indicating hydrocarbon pollution water in all the sample stations throughout the year. Overall, the findings of this study confirm that coastal waters in Ibeju-Lekki are subject to pollution from industrial effluents and anthropogenic activities.

Table 5.

Water Quality and Physiochemical Parameter Analysis

Table 5.

Water Quality and Physiochemical Parameter Analysis

| Heavy Metals |

Min |

Max |

MEAN

±STDEV |

PERMISSIBLE LIMITS

(USEPA) |

PERMISSIBLE LIMITS

(FEPA, 2003) |

REMARKS |

| Lead (Pb) |

0.00 |

0.93 |

0.20±0.17 |

0.14 [43] |

<1.00 |

Within acceptable limits nationally but above the international limit |

| Cadmium (Cd) |

0.00 |

0.20 |

0.06±0.06 |

0.03 [44] |

<1.00 |

| Iron (Fe) |

0.31 |

3.16 |

2.62±0.51 |

1.00 [45] |

- |

| Manganese (Mn) |

0.07 |

0.38 |

0.19±0.11 |

0.10 (2010) |

5.00 |

| Nickel (Ni) |

0.21 |

0.93 |

0.64±0.19 |

0.07 [46] |

<1.00 |

| Chromium (Cr) |

0.00 |

7.00 |

1.73±2.09 |

0.18 [47] |

<1.00 |

Above acceptable limits |

3.4 Anthropogenic Factors Affecting Sardinella maderensis Abundance.

Linear regression analysis conducted to determine if anthropogenic factors predict

Sardinella maderensis abundance revealed that land use change, amenities and fishing efforts significantly predict S. maderensis abundance (

Table 6). The regression model’s outcomes were significant,

F(3,356) = 5.75,

p < .001,

R2 = .05, reveals that about 4.62% of the variance in V_FISHCATCH is explainable by V_LANDUSE, V_AMENITY, and V_FISHG_EFFORT.

The unstandardised regression equation is:

indicating fish abundance is significantly predicted by land use, amenities and fishing effort. Urban land use changes (V_LANDUSE) negatively predict fishing abundance (V_FISHCATCH), B = -0.13, t(356) = -2.10, p = .037. This means urban land use change in coastal communities, on average, significantly reduces fish abundance. Conversely, provision of amenities (V_AMENITY) significantly enhances abundance (V_FISHCATCH), B = 0.05, t(356) = 2.64, p = .009. It implies that access to good roads, schools, telecommunications and other social amenities improves the fishers' livelihood and increases Sardinella maderensis fish abundance. Excessive fishing efforts can have a negative effect on S. maderensis fishery, leading to low yields. Fishing efforts (V_FISHG_EFFORT) significantly predicted abundance (V_FISHCATCH), B = -0.004, t(356) = -2.57, p = .011. The regression model results corroborate the negative effects of anthropogenic habitat loss and overfishing documented across tropical fisheries [

14,

15,

16].

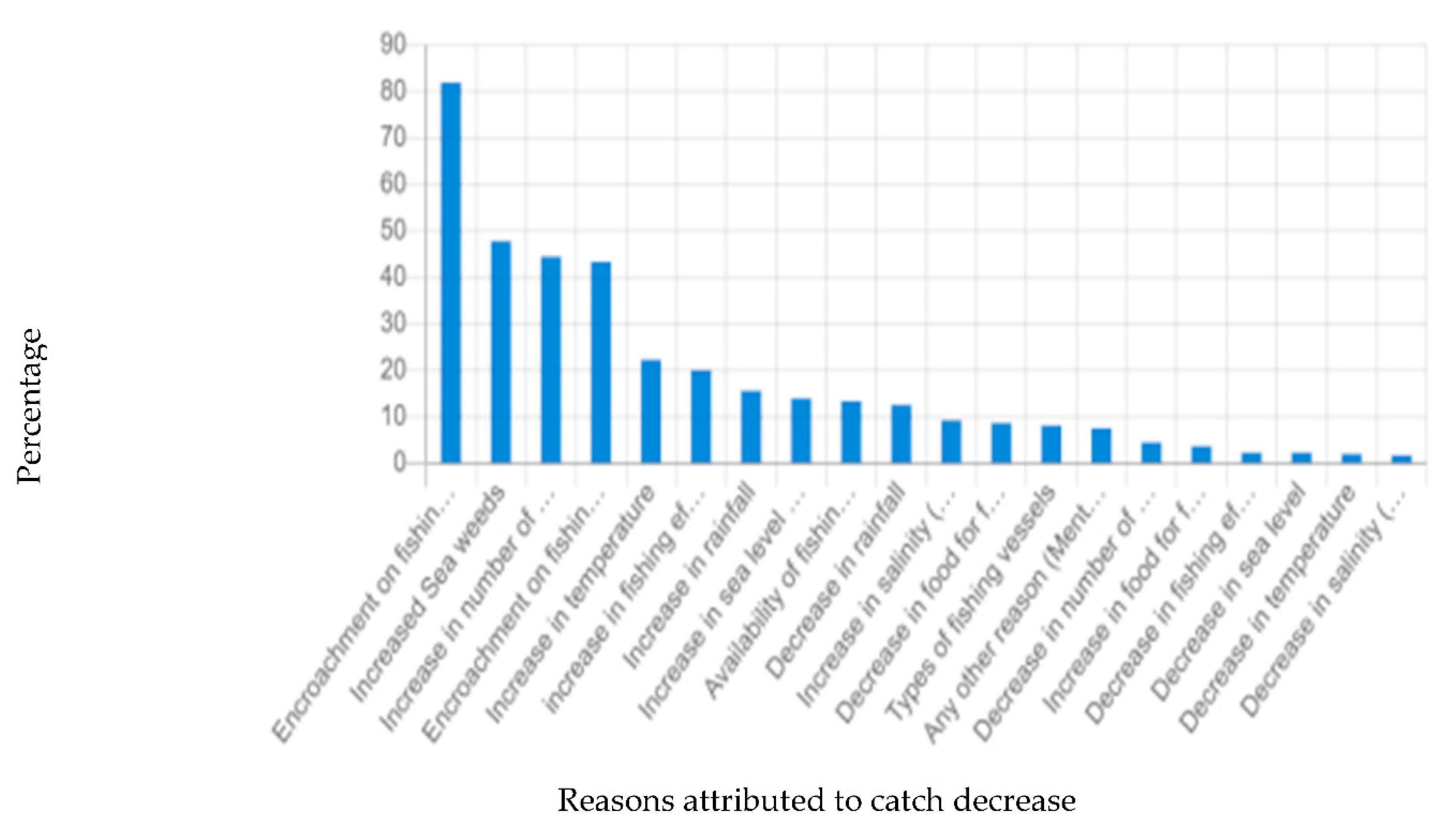

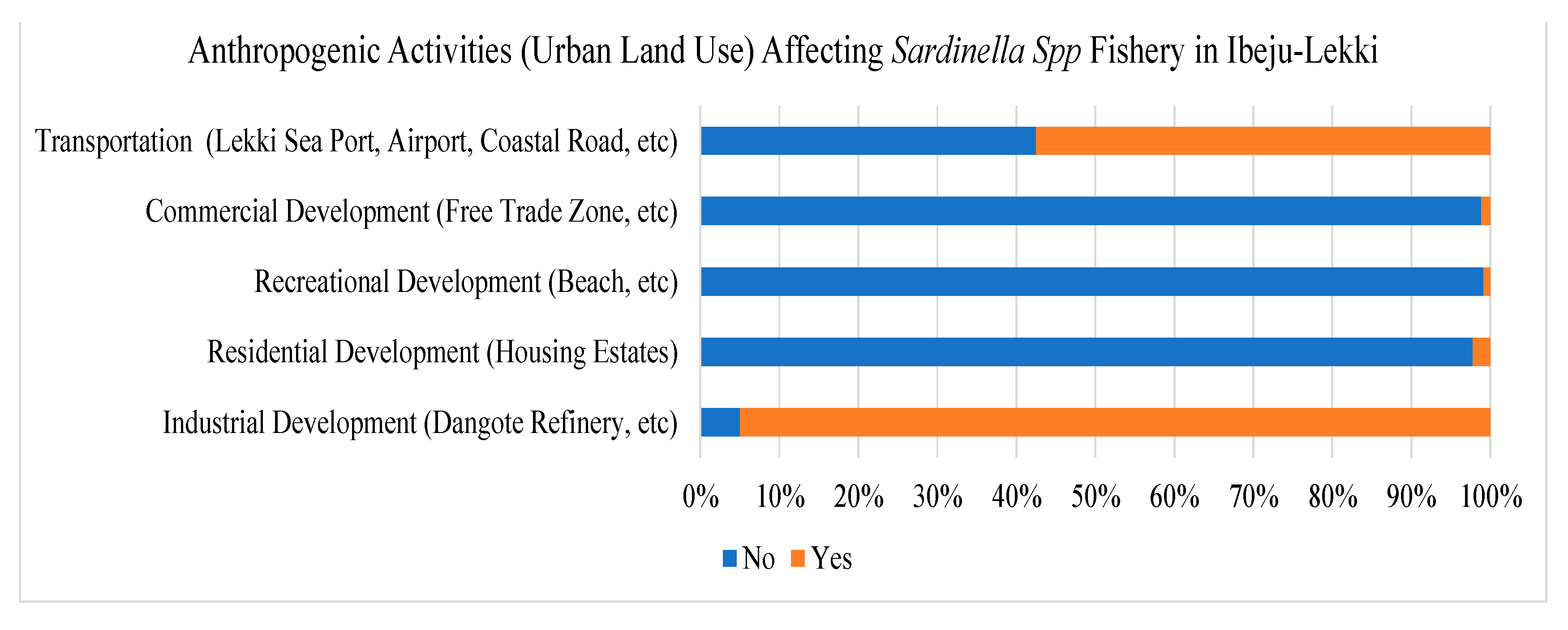

3.5. Fishers' Perceptions and Vulnerabilities

According to the survey results, most fishers perceived a decline in fish catch of S. maderensis, which they attributed to encroachment and loss of fishing grounds to urban land use like industries, petrochemical refinery, dredging, critical transportation infrastructure like the Lekki Deep Sea Port, and from other major anthropogenic activities in Ibeju-Lekki (

Figure 5). As shown in Figure 8, 95% of the fishers claimed that their livelihoods and

S. maderensis fishery are affected mainly by the refinery development and other industrial land uses. Meanwhile, 57.5% of the fishers contended that the construction of the Lekki Deep Sea Port has led to a decline in the fishery. On the other hand, other land use activities like residential, commercial and recreational developments have a shallow effect on the Sardinella fishery as less than 3% of the fishers are affected by these activities.

Analysis of the vulnerabilities of fishers in

Table 7 showed that loss of physical assets and risks to life from occupational hazards were significant concerns. In contrast, economic vulnerability due to a decline in income and limited access to amenities like potable water, electricity, and health facilities are red flags compounding fishers' vulnerability. Summarily, the results indicate how anthropogenic activities exuberate risks and impair the resilience of a vulnerable fishing community.

Table 7.

Vulnerability of Fishers in Ibeju-Lekki, Lagos.

Table 7.

Vulnerability of Fishers in Ibeju-Lekki, Lagos.

| Vulnerabilities |

Strongly agree Agree |

Agree |

Neither Agree nor Disagree |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

Weighted Score

|

Mean

|

Rank

|

| |

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

| Natural Assets/Capital |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Loss of marine plankton & shrimp (fish food) |

39 |

184 |

32 |

105 |

0 |

1237 |

3.44 |

17 |

| Poor water quality/pollution |

12 |

182 |

43 |

120 |

3 |

1160 |

3.22 |

18 |

| Loss of fishing grounds/area |

15 |

269 |

35 |

29 |

12 |

1326 |

3.68 |

16 |

| Loss of landing sites |

5 |

79 |

31 |

189 |

56 |

868 |

2.41 |

20 |

| Decrease in the availability of Sardinella

|

160 |

73 |

10 |

113 |

4 |

1352 |

3.76 |

14 |

| Decrease in quality (size, etc.) of Sardinella

|

163 |

70 |

11 |

110 |

6 |

1354 |

3.76 |

14 |

| Physical Assets/Capital |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Loss of Housing |

16 |

52 |

25 |

181 |

86 |

811 |

2..25 |

21 |

| Loss of Boats/Canoes |

250 |

82 |

3 |

21 |

4 |

1633 |

4.54 |

2 |

| Loss of Basic Infrastructure |

20 |

81 |

29 |

193 |

37 |

934 |

2..59 |

19 |

| Loss of equipment/fishing gears |

267 |

75 |

2 |

15 |

1 |

1672 |

4..64 |

1 |

| Human Assets/Capital |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Risk to life due to bad weather |

131 |

208 |

15 |

4 |

2 |

1542 |

4.28 |

3 |

| Health challenges |

114 |

224 |

13 |

7 |

2 |

1521 |

4.23 |

6 |

| Decline in skilled fishers/labour |

112 |

184 |

30 |

26 |

8 |

1446 |

4.02 |

10 |

| Economic/Financial Capital |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Declining income/profits |

128 |

213 |

8 |

9 |

2 |

1536 |

4.27 |

4 |

| Poor savings/lack of cash |

115 |

231 |

0 |

13 |

1 |

1526 |

4.24 |

5 |

| Increase debt/ Lack credit/loans |

114 |

212 |

8 |

14 |

2 |

1502 |

4.17 |

7 |

| Lack/high cost of insurance |

112 |

178 |

7 |

46 |

17 |

1402 |

3.89 |

12 |

| Social Asset/Capital |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Loss of social relationships |

80 |

248 |

26 |

0 |

6 |

1476 |

4.10 |

8 |

| Lack of affiliations/association |

79 |

215 |

25 |

36 |

5 |

1407 |

3.91 |

11 |

| Loss of diversity (cultural diversity, ethnic diversity |

80 |

203 |

25 |

46 |

6 |

1385 |

3.85 |

13 |

| Sense of insecurity and lack of safety |

114 |

198 |

7 |

34 |

7 |

1458 |

4.05 |

9 |

| Weighted Score |

10630 |

13844 |

1185 |

2622 |

267 |

28548 |

|

|

| % of Respondents affected |

37.24 |

48.49 |

4.15 |

9.18 |

0.94 |

100.00 |

|

|

4. Discussion

This study provides empirical evidence on how growing anthropogenic pressures driven by unsustainable industrialisation affect S. maderensis fisheries, which coastal communities depend on for their nutrition and livelihoods. Massive land reclamation for constructing the Lekki Deep Sea Port and petrochemical refinery has extensively damaged the coastal ecosystems in Ibeju-Lekki over barely three and half decades. Effluents from industrial and port activities also significantly polluted the coastal waters. These mounting anthropogenic impacts intensify climatic pressures like rising sea levels, threatening small-scale fisheries' sustainability.

The findings of this study align with previous research conducted in other tropical regions, which emphasise the negative impacts of unregulated coastal development on the resilience of fishing communities [

48,

49,

50]. Mangroves, seagrass beds, and other coastal habitats are crucial as nursery grounds and provide ecological support for S. maderensis fisheries [

51,

52]. Consequently, the loss of habitats from dredging and landfill activities destroys the ecological resources that sustain small-scale fisheries. In addition, industrial pollution creates a toxic ecosystem, as it introduces heavy metals and petrochemical effluents that potentially impair the growth, survival, and recruitment success of S. maderensis [

53]. Moreover, the high levels of heavy metal and hydrocarbon pollution along the Ibeju-Lekki coastal area of Lagos exceed international standards and require broad environmental management strategies. The observed decrease in chlorophyll levels indicates a decline in phytoplankton abundance, potentially adversely affecting the S. maderensis populations due to their planktivorous feeding habits. The compounding effects of various anthropogenic pressures contribute to the exacerbation of climatic impacts observed by the fishers, making the fishing communities more vulnerable.

In general, the findings emphasise the necessity of adopting a comprehensive and inclusive strategy for coastal development that safeguards the fundamental natural resources that sustain the local population's livelihoods [

54]. Presently, existing development plans and policies for Ibeju-Lekki emphasise top-down development strategies that prioritise industrial enterprises, aiming to achieve economic benefits. However, these policies often overlook the socio-ecological impacts on marginalised small-scale fisheries [

55]. Nevertheless, neglecting these consequences undermines long-term sustainability. Hence, adopting an ecosystem-based approach in fisheries management is necessary, necessitating implementing integrated marine spatial planning strategies for land and water use aimed at conserving vital fish habitats [

56,

57]. Implementing rigorous water quality monitoring and strict enforcement of effluent standards is crucial for mitigating industrial pollution. There is also a need to control detrimental activities such as unregulated sand dredging, which has a negative impact on resilience. The implementation of fisheries management systems that are grounded on rights-based principles has the potential to mitigate overfishing and empower fishing communities effectively [

58]. In general, the mitigation of anthropogenic threats necessitates the implementation of multi-level governance approaches that effectively balance economic development, ecological sustainability, and social equity [

59].

This investigation provides a framework for research approaches to assess anthropogenic threats in small-scale fisheries worldwide. However, more extensive spatial and temporal sampling across numerous seasons would have improved the outcomes. Future studies could build upon these findings by applying ecosystem models to delve deeper into the intricate ecological relationships between declining fish catches, habitat loss, pollution, and climatic variations. Furthermore, it is imperative to investigate potential adaptation strategies to strengthen resilience. This includes exploring economic alternatives that minimise dependence on fisheries, which have become less reliable. In summary, this research highlights the importance of addressing human-induced challenges such as pollution and habitat loss to ensure the sustainability of small-scale fisheries, which play a vital role in providing employment, food security, and nutrition in rapidly developing coastal regions.

5. Conclusion

This research investigated the effects of anthropogenic activities on small-scale fisheries, which play a crucial role in supporting the livelihoods of several economically disadvantaged populations along the coastal regions of Nigeria. The findings indicate reductions in the catches of S. maderensis, which can be attributed to various factors, including industrial pollution, mangrove depletion, dredging activities, and overfishing in the Ibeju-Lekki region of Lagos State. The absence of regulations in coastal development has a detrimental effect on the biological underpinnings that support small-scale fisheries, intensifying the impact of climate change and diminishing the ability of communities to adapt and recover. There is an urgent requirement to implement strategies to mitigate industrial pollution, regulate land reclamation, restore damaged habitats, curb overfishing, and promote inclusive growth. Also, there is a need for marine spatial planning (MSP) to promote sustainable use of the ocean and land resources in coastal regions. Incorporating scientific evidence and community viewpoints into ecosystem-based management strategies can contribute to the establishment of robust small-scale fisheries that promote sustainable livelihoods, nutritional well-being, and the protection of biodiversity in fast-growing tropical coastal areas. The research methods and findings offer significant insights that may be globally applied to detecting and mitigating anthropogenic threats in small-scale fisheries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, T.A.; methodology, T.A.; software, T.A and S.D.; validation, D.A., I.O. and O.S.; formal analysis, T.A. and S.D.; investigation, T.A.; resources, D.A., I.O. and O.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.A.; writing—review and editing, T.A. and S.D.; supervision, D.A., I.O., and O.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and APC were funded by the Africa Centre of Excellence in Coastal Resilience (ACECoR), University of Cape Coast, with support from the World Bank and the Government of Ghana. The World Bank ACE Grant Number is credit number 6389-G.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Cape Coast with reference number UCCIRB/CANS/2020/09 and the Health Research Ethics Committee of the College of Medicine of the University of Lagos (HRECMUL), Lagos, Nigeria with reference number CMUL/HREC/10/20/784.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this research are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the World Bank Africa Centre of Excellence in Coastal Resilience (ACECoR), the University of Cape Coast, Ghana, the Association of African Universities and the Government of Ghana for funding this research and the fishers in the study area who, voluntarily took part in the survey interviews.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Cape Coast and the Health Research Ethics Committee of the College of Medicine of the University of Lagos (HRECMUL) as part of the first author's PhD thesis and ethical clearance was given with reference number UCCIRB/CANS/2020/09 and CMUL/HREC/10/20/784 respectively.

References

- Blasiak, R.; Wabnitz, C.C.C. Aligning Fisheries Aid with International Development Targets and Goals. Mar. Policy 2018, 88, 86–92. [CrossRef]

- FAO World Fisheries and Aquaculture, FAO:Rome,2022; 2022; ISBN 9789251072257.

- Olaoye, O.J.; Ojebiyi, W.G. Marine Fisheries in Nigeria: A Review. In Marine Ecology -Biotic and Abiotic Interactions; IntechOpen, 2018; pp. 155–173. [CrossRef]

- FAO FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture: Fishery and Aquaculture Profiles -The Federal Republic of Nigeria; Rome, Italy, 2017;

- Adeosun, A. Draft Of Socio-Economic/Sia Baseline Report For The Proposed Pipeline Route For The Dangote Fertiliser Plant Project, In Ibeju-Lekki Government Area Of Lagos StatE.; Lagos, 2017;

- Anetekhai, M.A.; Whenu, O.O.; Osodein, O.A.; Fasasi, A.O. Beach Seine Fisheries in Badagry, Lagos State, South West, Nigeria. Brazilian J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 5, 815–835. [CrossRef]

- Jim-Saiki, L.O.; Aihaji, T.A.; Giwa, J.E.; Oyerinde, M.; Adedeji, A.K. Factors Constraining Artisanal Fish Production in the Fishing Communities of Ibeju-Lekki Local Government Area of Lagos State Abstract : Int. J. Innov. Res. Dev. 2014, 3, 97–101.

- Omenai, J.; Ayodele, D. The Vulnerability of Eti-Osa and Ibeju-Lekki Coastal Communities in Lagos State Nigeria to Climate Change Hazards. 2014, 4, 132–143.

- Whitehead, P.J.P. FAO Species Catalogue. Vol. 7. Clupeoid Fishes of the World (Suborder Clupeoidei). An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of the Herrings, Sardines, Pilchards, Sprats, Shads, Anchovies and Wolf-Herrings. FAO Fish. Synop. 1985, 125, 1–303.

- FAO Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics 2017; Food and Agriculture Organisation: Rome, 2019; ISBN 9789251316696.

- Solarin, B.; Kusemiju, K.; Akande, G. Species Composition and Abundance of Finfish and Shellfish Resources of the Coastal and Brackish Water Areas of Nigeria.; Lagos, 2008;

- Tous, P.; Sidibe, A.; Mbye, E.; DeMorais, L.; Camara, K.; Munroe, T.; Adeofe, T.; Camara, Y.H.; Djiman, R.; Sagna, A.; et al. Sardinella Maderensis; The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015; 2015;

- Adeleke, M.L.; Al-Kenawy, D.; Nasr-Allah, A.M.; Murphy, S.; El-Naggar, G.O.; Dickson, M. Fish Farmers’ Perceptions, Impacts and Adaptation on/of/to Climate Change in Africa (the Case of Egypt and Nigeria). In Climate Change Management; Alves, F. et al., Ed.; Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018: Egypt, 2018; pp. 269–295 ISBN 9783319728742.

- Akintola, S.L.; Fakoya, K.A. Small-Scale Fisheries in the Context of Traditional Post-Harvest Practice and the Quest for Food and Nutritional Security in Nigeria. Agric. Food Secur. 2017, 6, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Akiode, O.S.; Falayi, E.O.; Amoo, I.A. Anthropogenic-Induced Changes in Vegetation Trends in Lekki Conservation Centre Wetland Area, Lagos State Nigeria. J. Ecol. Nat. Environ. 2011, 3, 1–10.

- Adeshokan, O. "What Will Be Left of Us?" Lagos Fishermen Lament the Oil Refinery. Guard. 2019, 1–7.

- Jones, D.L.; Rowe, E.C. Land Reclamation and Remediation, Principles and Practice. Ref. Modul. Life Sci. Encycl. Appl. Plant Sci. 2017, 3, 304–310. [CrossRef]

- Bali, A.S.; Sidhu, G.P.; Kumar, V. Chapter 29 - Plant Enzymes in Metabolism of Organic Pollutants. In Handbook of Bioremediation: Physiological, Molecular and Biotechnological Interventions; Academic Press, 2021; pp. 465–474.

- Hiralal, S.; Sagar, A.; Ashish, B.; Akanksha, J. Targeted Genetic Modification Technologies: Potential Benefits of Their Future Use in Phytoremediation. In Phytoremediation: Biotechnological Strategies for Promoting Invigorating Environs; Academic Press, 2022; pp. 203–226.

- Chikelu, G.C. Regulating IUU Fishing in Nigeria : A Step towards Discovering the Untapped Potentials of Fisheries in Nigeria., World Maritime University, 2021.

- Abiodun, S. ( Illegal Fishing (IUU) Activities in Nigeria Territorial Waters and Its Economic Impacts. J. homepage www. ijrpr. com ISSN, 2582, 7421. 2021.

- Oluwatobi, A.O.J. Impacts of Climate Change on the Coastal Areas of Nigeria. J. Geogr. Reg. Plan. 2017, 10, 533–541.

- Udoh, J.P.; Ukpong, I.G. An Assessment of Anthropogenic Drivers of Ecosystem Change in the Calabar River Catchment, Cross River State, Nigeria. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2013, 15, 885–903.

- Jinadu, O.O. Small-Scale Fisheries In Lagos State, Nigeria: Economic Sustainable Yield Determination. Fed. Coll. Fish. Mar. Technol. Wilmot Point, Victoria Island, Lagos Niger. 2000, 1–11.

- Dekolo, S.; Oduwaye, A. Managing the Lagos Megacity and Its Geospacial Imperative. In Proceedings of the International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote sensing and Spatial Information Sciences; 2011; Vol. XXXVIII, pp. 121–128.

- Adeosun, A. Draft Of Socio-Economic/Sia Baseline Report For The Proposed Pipeline Route For The Dangote Fertiliser Plant Project, In Ibeju-Lekki Government Area Of Lagos State.; Lagos, 2017;

- Hennink, M..; Kaiser, B..; Weber, M.. What Influences Saturation? Estimating Sample Sizes in Focus Group Research. Qual Heal. Res. 2019, 29, 1483–1496. [CrossRef]

- Froese, R.; Pauly, D. FishBase, Worldwide Electronic Publication.

- FAO Food and Agricultural Organization. Field Guide to Commercial Marine Resources of the Gulf of Guinea.; FAO/Unnited Nations: Italy., 1990;

- Ward, R.D.; Zemlak, T.S.; Innes, B.H.; Last, P.R.; Hebert, P.D.N. DNA Barcoding Australia’s Fish Species. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2005, 360, 1847–1857. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, N. V.; Zemlak, T.S.; Hanner, R.H.; Hebert, P.D.N. Universal Primer Cocktails for Fish DNA Barcoding. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2007, 7, 544–548. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Kim, J.; Kang, T.W.; Jeong, U.; Kim, K.R.; Bang, I.C. The Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Sardinella Zunasi (Clupeiformes: Clupeidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B Resour. 2021, 6, 1178–1180. [CrossRef]

- Takyi, E. Population Genetic Structure of Sardinella Aurita and Sardinella Madurensis in the Eastern Central Atlantic Region (Cecaf) in West Africa, University of Rhode Island, 2019.

- Jensen, J.R. Introductory Digital Image Processing: A Remote Sensing Perspective.; Prentice-Hall Inc., 1996;

- APHA American Public Health Association – APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater.; Washington, DC., 2005;

- UNEP/IOC Guidelines on Survey and Monitoring of Marine Litter.; 2015;

- Arizi, E.K.; Collie, J.S.; Castro, K.; Humphries, A.T. Fishing Characteristics and Catch Composition of the Sardinella Fishery in Ghana Indicate Urgent Management Is Needed. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2022, 52, 102348. [CrossRef]

- Stobart, B.; Alvarez-Barastegui, D.; Goñi, R. Effect of Habitat Patchiness on the Catch Rates of a Mediterranean Coastal Bottom Long-Line Fishery. Fish. Res. 2012, 129–130, 110–118. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, W.L.; White, G.C.; Gowan, C. Fish. In Monitoring Vertebrate Populations; Thompson, W.L., White, G.C., Gowan, C.B.T.-M.V.P., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, 1998; pp. 191–232 ISBN 978-0-12-688960-4.

- Gourène, G.; Teugels, G.G. Clupeidae. In The fresh and brackish water fishes of West Africa.; Paugy, D., Lévêque, C., Teugels, G.., Eds.; Coll. faune et flore tropicales 40. Institut de recherche de développement, Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, Paris, France and Musée royal de l’Afrique Central, Tervuren, Belgium.: Paris, France, 2003; pp. 125–142.

- Fischer, W.; Bianchi, G.; Scott, W.B.; (Eds) FAO Species Identification Sheets for Fishery Purposes. Eastern Central Atlantic; Fishing Areas 34, 47 (in Part).; Fischer, W., Bianchi, G., Scott, W.B., Eds.; vols. 1-7:; Canada Funds-in-Trust. Ottawa, Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, by arrangement with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.: Ottawa, Canada, 1981;

- FEPA Guidelines and Standards for Environmental Pollution Control in Nigeria.; Federal Environmental Projection Agency: Nigeria., 2003;

- USEPA United States Office of Water Environmental Protection Regulations and Standards Agency Criteria and Standards Division Wahington, DC 20460 Water Ambient Water Quality Criteria for EPA 440/5-84-027 Lead - 1984; 1985;

- USEPA Fact Sheet: Aquatic Life Ambient Water Quality Criteria Update for Cadmium EPA-822-F-16-003. 2016, 304.

- USEPA Water Quality Standards Criteria Summaries:A Compilation of State/Federal Criteria-Iron.; 1988;

- USEPA United States. Environmental Protection Agency · 1995 · Full View · More Editions PB95-187266REB PC A22 / MF A04 Water Quality Guidance for the Great Lakes System : Supplementary Information ... Zinc, Selenium, Nickel, Mercury ( Metal ),' Great Lak; 1995;

- USEPA Ambient Water Quality Criteria for Chromium. Ambient Water Qual. Criteria Chromium 1980.

- Murshed-E-Jahan, K.; Pemsl, D. The Impact of Integrated Aquaculture-Agriculture on Small-Scale Farm Sustainability and Farmers' Livelihoods: Experience from Bangladesh. Agric. Syst. 2011, 104, 392–402.

- Sievanen, L. How Do Small-Scale Fishers Adapt to Environmental Variability? Lessons from Baja California, Sur, Mexico. Marit. Stud. 2014, 13, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N.; Bennett, N.J.; Le Billon, P.; Green, S.J.; Cisneros-Montemayor, A.M.; Amongin, S.; Gray, N.J.; Sumaila, U.R. Oil, Fisheries and Coastal Communities: A Review of Impacts on the Environment, Livelihoods, Space and Governance. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 75, 102009. [CrossRef]

- Nordlund, L.M.; Unsworth, R.K.F.; Gullström, M.; Cullen-Unsworth, L.C. Global Significance of Seagrass Fishery Activity. Fish Fish. 2018, 19, 399–412. [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, R.K.F.; Nordlund, L.M.; Cullen-Unsworth, L.C. Seagrass Meadows Support Global Fisheries Production. Conserv. Lett. 2019, 12, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Monier, M.N.; Soliman, A.M.; Al-Halani, A.A. The Seasonal Assessment of Heavy Metals Pollution in Water, Sediments, and Fish of Grey Mullet, Red Seabream, and Sardine from the Mediterranean Coast, Damietta, North Egypt. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2023, 57, 102744. [CrossRef]

- Bavinck, M.; Jentoft, S.; Scholtens, J. Fisheries as Social Struggle: A Reinvigorated Social Science Research Agenda. Mar. Policy 2018, 94, 46–52. [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.W.; Pomeroy, R.S. Driving Small-Scale Fisheries in Developing Countries. Front. Mar. Sci. 2015, 2, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Patrick, W.S.; Link, J.S. Myths That Continue to Impede Progress in Ecosystem-Based Fisheries Management. Fisheries 2015, 40, 155–160. [CrossRef]

- Pikitch, E.K.; Santora, C.; Babcock, E.A.; Bakun, A.; Bonfil, R.; Conover, D.O.; Dayton, P.; Doukakis, P.; Fluharty, D.; Heneman, B.; et al. Ecosystem-Based Fishery Management. Science (80-. ). 2004, 305, 346–347. [CrossRef]

- Gelcich, S.; Hughes, T.P.; Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Defeo, O.; Fernández, M.; Foale, S.; Gunderson, L.H.; Rodríguez-Sickert, C.; Scheffer, M.; et al. Navigating Transformations in Governance of Chilean Marine Coastal Resources. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 16794–16799. [CrossRef]

- Jentoft, S.; Chuenpagdee, R. Assessing Governability of Small-Scale Fisheries. In Interactive Governance for Small-Scale Fisheries: Global Reflections; Jentoft, S., Chuenpagdee, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; pp. 17–35 ISBN 978-3-319-17034-3.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).