Submitted:

28 November 2023

Posted:

29 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Leaf Photosynthetic Characteristics

2.3. Analysis of Carbon, Nitrogen, and Hydrogen Partition

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Variance

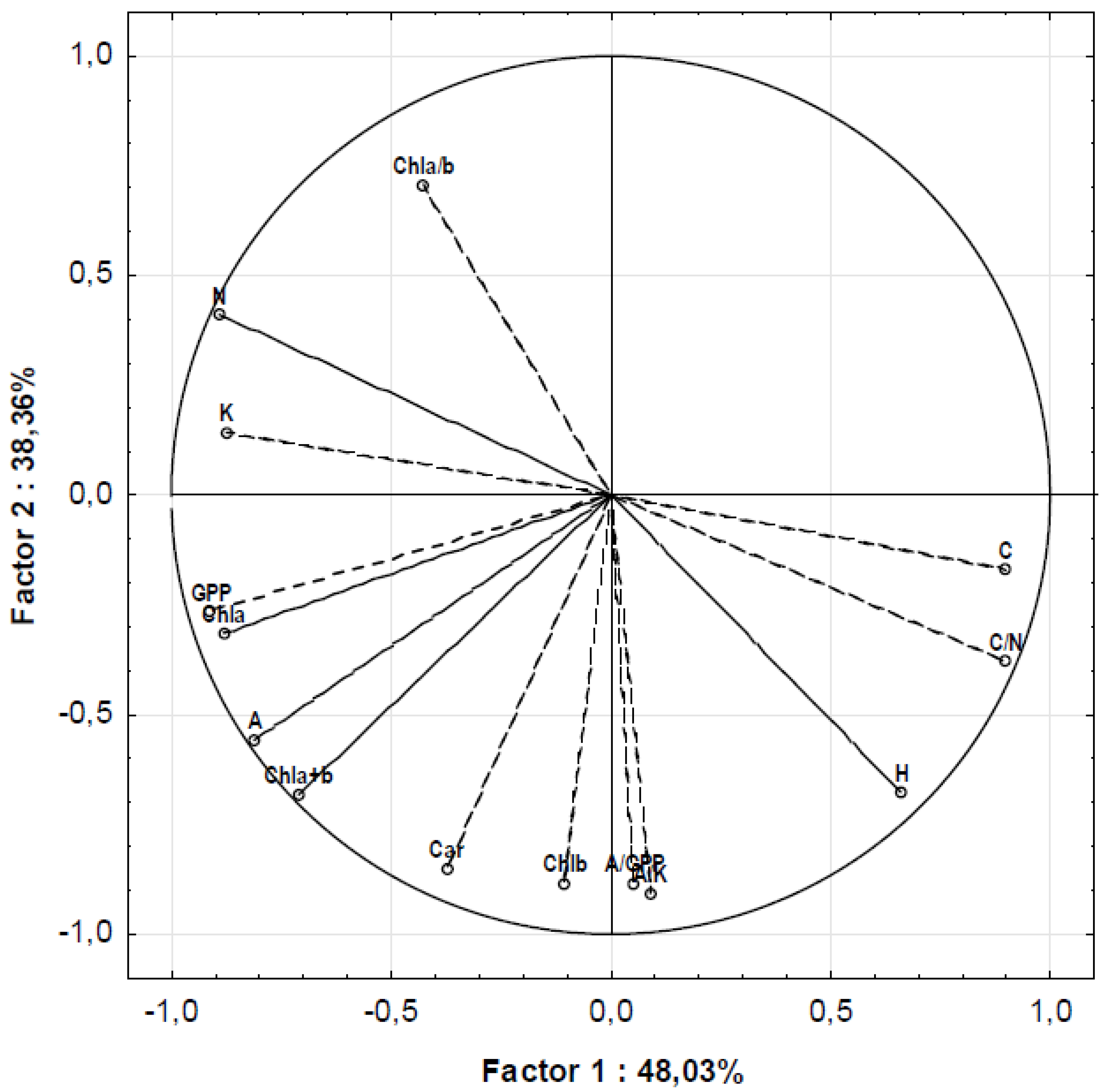

3.2. Principal Component Analysis

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Endsley, K.A. Remote sensing of socio-ecological dynamics in urban neighbourhoods. In Comprehensive Remote Sensing; Liang, S., Ed.; Elsevier Inc.: The Netherland, 2018; Volume 9, pp. 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, R.M.; Szlafsztein, C.F. Urban vegetation loss and ecosystem services: The influence on climate regulation and noise and air pollution. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 245, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroud, S. , Peacock, J., Hassall, C. (2022): Vegetation-based ecosystem service delivery in urban landscapes: A systematic review. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2022, 61, 82–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vastag, E.; Kesić, L.; Karaklić, V.; Zorić, M.; Vuksanović, V.; Stojnić, S. Physiological performance of sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua L.) and Norway Maple (Acer platanoides L.) under drought conditions in urban environment. Topola/Poplar 2019, 204, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, L.; Anderson, S.; Læssøe, J.; Banzhaf, E.; Jensen, A.; Bird, D.N.; Miller, J.; Hutchins, M.G.; Yang, J.; Garrett, J.; Taylor, T.; Wheeler, B.W.; Lovell, R.; Fletcher, D.; Qu, Y.; Vieno, M.; Zandersen, M. A typology for urban Green Infrastructure to guide multifunctional planning of nature-based solutions. Nature-Based Solutions 2022, 2, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Jhariya, M.K.; Yadav, D.K.; Banerjee, A. Structure, diversity and ecological function of shrub species in an urban setup of Sarguja, Chhattisgarh, India. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020, 27, 5418–5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poljaković-Pajnik, L.; Stojanović, D.; Drekić, M.; Pilipović, A.; Vasić, V. Climate change and invasive insect species in forests, urban areas and nurseries in Serbia. In Proceedings of the Water in Forests International Conference of KASZÓ-LIFE, Croatia, Serbia, 29–30 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ilić Milošević, M.; Žikić, V.; Milenković, D.; Stanković, S.S.; Olivera Petrović-Obradović, O. Diversity of aphids (Homoptera: Aphididae) in Southeastern Serbia. Biologica Nyssana 2019, 10, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borbély, C.; György, Z.; Jacobsen, S.K.; Musa, F.; Ouředníčková, J.; Sigsgaard, L.; Skalsky, M.; Marko, V. First records of the invasive aphid species, Aphis spiraecola, in Kosovo, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, the United Kingdom and Denmark. Plant Protect. Sci. 2021, 57, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, R.L.; Eastop, V.F. Aphids on the World’s Crops: An Identification and Information Guide, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dedryver, C.-A.; Le Ralec, A.; Fabre, F. The conflicting relationships between aphids and men: A review of aphid damage and control strategies. C. R. Biol. 2010, 333, 539–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coeur d’Acier, A.; Hidalgo, N.P.; Petrović-Obradović, O. Aphids (Hemiptera, Aphididae). Chapter 9.2. BioRisk. 2010, 4, 435–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpeiner, A. Aphididae (Hemiptera) on ornamental plants in Córdoba (Argentina). Rev. Soc. Entomol. Argent. 2008, 67, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gleditsch, J.M.; Carlo, T.A. Fruit quantity of invasive shrubs predicts the abundance of common native avian frugivores in central Pennsylvania. Divers. Distrib. 2011, 17, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuperus, G.W.; Radcliffe, E.B.; Barnes, D.K.; Marten, G.C. Economic injury levels and economic thresholds for pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum (Harris), on alfalfa. Crop Prot. 1982, 1, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burd, J.D.; Elliott, N.C. Changes in Chlorophyll a Fluorescence Induction Kinetics in Cereals Infested with Russian Wheat Aphid (Homopetra: Aphididea). J. Econ. Entomol. 1996, 89, 1332–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telang, A.; Sandström, J.; Dyreson, E.; Moran, N.A. Feeding damage by Diuraphis noxia results in a nutritionally enhanced phloem diet. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1999, 91, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Quisenberry, S.S.; Heng-Moss, T.; Markwell, J.; Higley, L.; Baxendale, F.; Sarath, G.; Klucas, R. Dynamic change in photosynthetic pigments and chlorophyll degradation elicited by cereal aphid feeding. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2002, 105, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. , Quisenberry, S.S., Ni, X., Tolmay, V. Aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae) resistance in wheat near-isogenic lines. J. Econ. Entomol. 2004, 97, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poljaković-Pajnik, L.; Petrović-Obradović, O.; Drekić, M.; Orlović, S.; Vasić, V.; Kovačević, B.; Kacprzyk, M.; Nikolić, N. Aphid feeding effects on physiological parameters of poplar cultivars. Proceedings of rge VII International Scientific Agriculture Symposium “Agrosym 2016”, Jahorina, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 6–9 October 2016; pp. 2848–2855. [Google Scholar]

- Hurej, M.; Werf, W.V.D. The influence of black bean aphid, Aphis fabae Scop., and its honeydew on the photosynthesis of sugar beet. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1993, 122, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, L.; Bolaño, C.; Pelissier, F. Use of oxygen electrode in measurements of photosynthesis and respiration. In Handbook of Plant Ecophysiology Techniques; Regiosa Roger, M.J., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, Holand, 2001; pp. 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettstein, D. Chlorophyll-letate und submikroskopische Formwechsel der Plastiden. Exp. Cell. Res. 1957, 12, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- TIBCO Software Inc. (2020). Data science work-bench, version 14. Web site. Available online: http://www.tibco.com/products/data-science.

- Shahzad, M.W.; Ghani, H.; Ayyub, M.; Ali, Q.; Ahmad, H.M.; Faisal, M.; Ali, A.; Qasim, M.U. Performance of some wheat cultivars against aphid and its damage on yield and photosynthesis. J. Glob. Innov. Agric. Soc. Sci. 2019, 7, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goławska, S.; Krzyżanowski, R.; Łukasik, I. Relationship between aphid infestation and chlorophyll content in Fabaceae species. Acta Biol. Crac. Ser. Bot. 2010, 52/2, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, A.M.; Gallardo, P. Relationship between insect damage and chlorophyll content in Mediterranean oak species. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2016, 14, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Montano, J.; Reese, J.; William Schapaugh, W.; Campbell, L. Chlorophyll Loss Caused by Soybean Aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae) Feeding on Soybean. J. Econ. Entomol. 2007, 100, 1657–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlović, S.; Guzina, V. , Krstić, B.; Merkulov. Lj. Genetic variability in anatomical, physiological and growth characteristics of hybrid poplar (Populus x euramericana Dode (Guinier)) and eastern cottonwood (Populus deltoides Bartr.) clones. Silvae Genet. 1998, 47, 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, P.W. Feeding process of Aphidoidea in relation to effects on their food plants. In Aphids: their Biology, Natural Enemies and Control; Minks, A.K., Harrewijn, P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Holand, 1987; Volume 2A, pp. 321–339. [Google Scholar]

- Cichocka, E.; Goszczyński, W.; Chacińska, M. The effect of aphids on host plants. I. Effect on photosynthesis, respiration and transpiration. Aphids and Other Homopterous Insects 1992, 3, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, P.W. Insect secretions in plants. Annu. Rev. Phitopathol. 1968, 6, 137–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.H.; Liu, X.D.; Srivastava, A.K.; Tan, Q.L.; Low, W.; Yan, X.; Wu, S.W.; Sun, X.C.; Hu, C.X. Foliar nutrition alleviate citrus plants from Asian citrus psyllid feeding by affecting leaf structure and secondary metabolism. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 309, 111667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadras, V.; Vázquez, C.; Garzo, E.; Moreno, A.; Medina, S.; Taylor, J.; Fereres, A. The role of plant labile carbohydrates and nitrogen on wheat-aphid relations. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slansky, F., Jr. Insect Nutritional Ecology as a Basis for Studying Host Plant Resistance. Fla. Entomol. 1990, 73, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slansky, F., Jr. Nutritional ecology: the fundamental quest for nutrients. In Caterpillars. Ecological and Evolutionary Constraints on Foraging; Stamp, N.E., Casey, T.M., Eds. Chapman and Hall: New York, USA, 1993; pp. 29–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, C.D.B.; Whitecross, M.I.; Aston, M.J. Interactions between aphid infestation and plant growth and uptake of nitrogen and phosphorus by three leguminous host plants. Can. J. Bot. 1986, 64, 2362–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source of variation | Chla | 1 | Chlb | Chla+b | Chla/b | Car | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species (A) | 5.286 | * | 3.590 | 7.167 | ** | 2.883 | 12.341 | ** | ||

| Colonization (B) | 0.978 | 0.135 | 0.249 | 0.141 | 2.479 | |||||

| Interaction A×B | 2.281 | 0.680 | 1.205 | 0.762 | 2.920 | |||||

| N | C | H | C/N | |||||||

| Species (A) | 2330.300 | ** | 295.800 | ** | 72.900 | ** | 17159.280 | ** | ||

| Colonization (B) | 251.000 | ** | 5.300 | * | 0.000 | 1215.895 | ** | |||

| Interaction A×B | 21.800 | ** | 1.700 | 2.400 | 202.505 | ** | ||||

| K | A | GPP | A/K | A/GPP | ||||||

| Species (A) | 22.747 | ** | 22.772 | ** | 26.742 | ** | 13.823 | ** | 15.478 | ** |

| Colonization (B) | 41.592 | ** | 8.354 | * | 25.434 | ** | 5.951 | * | 8.319 | * |

| Interaction A×B | 2.257 | 0.813 | 1.168 | 0.362 | 1.062 |

| Species | Colonization | Chla | 1 | Chlb | Chla+b | Chla/b | Car | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spirea trilobata | 1.225 | ab | 0.694 | a | 1.919 | a | 2.130 | a | 0.672 | a | |

| Hybiscus syriacus | 1.430 | a | 0.460 | a | 1.890 | a | 3.440 | a | 0.490 | ab | |

| Cydonia japonica | 0.926 | b | 0.313 | a | 1.239 | b | 2.996 | a | 0.322 | b | |

| Non-colonized | 1.256 | a | 0.467 | a | 1.724 | a | 2.770 | a | 0.449 | a | |

| Colonized | 1.130 | a | 0.511 | a | 1.641 | a | 2.940 | a | 0.540 | a | |

| Spirea trilobata | Non-colonized | 1.418 | ab | 0.583 | a | 2.002 | a | 2.441 | a | 0.808 | a |

| Spirea trilobata | Colonized | 1.031 | ab | 0.805 | a | 1.836 | a | 1.820 | a | 0.536 | ab |

| Hybiscus syriacus | Non-colonized | 1.549 | a | 0.515 | a | 2.064 | a | 3.153 | a | 0.524 | ab |

| Hybiscus syriacus | Colonized | 1.310 | ab | 0.405 | a | 1.715 | a | 3.727 | a | 0.456 | b |

| Cydonia japonica | Non-colonized | 0.801 | b | 0.304 | a | 1.106 | a | 2.718 | a | 0.288 | b |

| Cydonia japonica | Colonized | 1.050 | ab | 0.321 | a | 1.371 | a | 3.274 | a | 0.355 | b |

| N | C | H | C/N | ||||||||

| Spirea trilobata | 2.912 | c | 47.768 | b | 6.871 | a | 16.421 | a | |||

| Hybiscus syriacus | 4.331 | a | 41.801 | c | 6.331 | c | 9.658 | c | |||

| Cydonia japonica | 3.049 | b | 48.764 | a | 6.656 | b | 16.072 | b | |||

| Non-colonized | 3.579 | a | 46.401 | a | 6.622 | a | 13.465 | b | |||

| Colonized | 3.282 | b | 45.821 | b | 6.617 | a | 14.636 | a | |||

| Spirea trilobata | Non-colonized | 3.006 | d | 47.855 | b | 6.905 | a | 15.921 | b | ||

| Spirea trilobata | Colonized | 2.818 | e | 47.682 | b | 6.836 | a | 16.922 | a | ||

| Hybiscus syriacus | Non-colonized | 4.447 | a | 41.967 | c | 6.358 | c | 9.437 | e | ||

| Hybiscus syriacus | Colonized | 4.215 | b | 41.634 | c | 6.305 | c | 9.878 | d | ||

| Cydonia japonica | Non-colonized | 3.284 | c | 49.381 | a | 6.602 | b | 15.037 | c | ||

| Cydonia japonica | Colonized | 2.815 | e | 48.147 | ab | 6.710 | ab | 17.107 | a | ||

| K | A | GPP | A/K | A/GPP | |||||||

| Spirea trilobata | 5.822 | b | 10.184 | a | 16.007 | b | 1.755 | a | 0.634 | a | |

| Hybiscus syriacus | 8.171 | a | 10.461 | a | 18.632 | a | 1.320 | b | 0.566 | b | |

| Cydonia japonica | 5.428 | b | 6.207 | b | 11.635 | c | 1.173 | b | 0.537 | b | |

| Non-colonized | 7.632 | a | 9.783 | a | 17.414 | a | 1.301 | b | 0.558 | b | |

| Colonized | 5.316 | b | 8.118 | b | 13.434 | b | 1.531 | a | 0.600 | a | |

| Spirea trilobata | Non-colonized | 6.711 | b | 11.368 | a | 18.079 | ab | 1.696 | ab | 0.628 | a |

| Spirea trilobata | Colonized | 4.934 | bc | 9.000 | abc | 13.934 | bcd | 1.814 | a | 0.640 | a |

| Hybiscus syriacus | Non-colonized | 9.868 | a | 11.447 | a | 21.316 | a | 1.169 | bc | 0.538 | bc |

| Hybiscus syriacus | Colonized | 6.474 | bc | 9.474 | ab | 15.947 | bc | 1.472 | abc | 0.595 | ab |

| Cydonia japonica | Non-colonized | 6.316 | bc | 6.533 | bc | 12.849 | cd | 1.039 | c | 0.509 | c |

| Cydonia japonica | Colonized | 4.539 | c | 5.882 | c | 10.421 | d | 1.307 | abc | 0.566 | abc |

| Original variable a) |

Principal component b) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC5 | |

| Chla | -0.881 | -0.313 | -0.042 | -0.312 | -0.162 |

| Chlb | -0.105 | -0.883 | 0.014 | 0.444 | -0.108 |

| Chla+b | -0.711 | -0.680 | -0.024 | -0.009 | -0.176 |

| Chla/b | -0.426 | 0.708 | -0.424 | -0.368 | -0.038 |

| Car | -0.373 | -0.851 | 0.105 | -0.330 | 0.133 |

| N | -0.892 | 0.411 | -0.066 | 0.157 | 0.082 |

| C | 0.898 | -0.171 | 0.375 | -0.133 | 0.071 |

| H | 0.662 | -0.678 | 0.238 | -0.212 | -0.032 |

| C/N | 0.899 | -0.377 | 0.126 | -0.145 | -0.114 |

| K | -0.875 | 0.143 | 0.461 | 0.027 | -0.025 |

| A | -0.810 | -0.557 | 0.143 | -0.034 | 0.115 |

| GPP | -0.911 | -0.267 | 0.309 | -0.007 | 0.057 |

| A/K | 0.089 | -0.907 | -0.398 | 0.059 | 0.081 |

| A/GPP | 0.053 | -0.883 | -0.461 | -0.013 | 0.064 |

| Eigenvalue | 6.725 | 5.370 | 1.111 | 0.653 | 0.141 |

| % of the total variance | 48.034 | 38.358 | 7.934 | 4.664 | 1.010 |

|

Cumulative Eigenvalue |

6.725 | 12.095 | 13.206 | 13.859 | 14.000 |

|

Cumulative % of the total variance |

48.034 | 86.392 | 94.326 | 98.990 | 100.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).