Submitted:

28 November 2023

Posted:

29 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

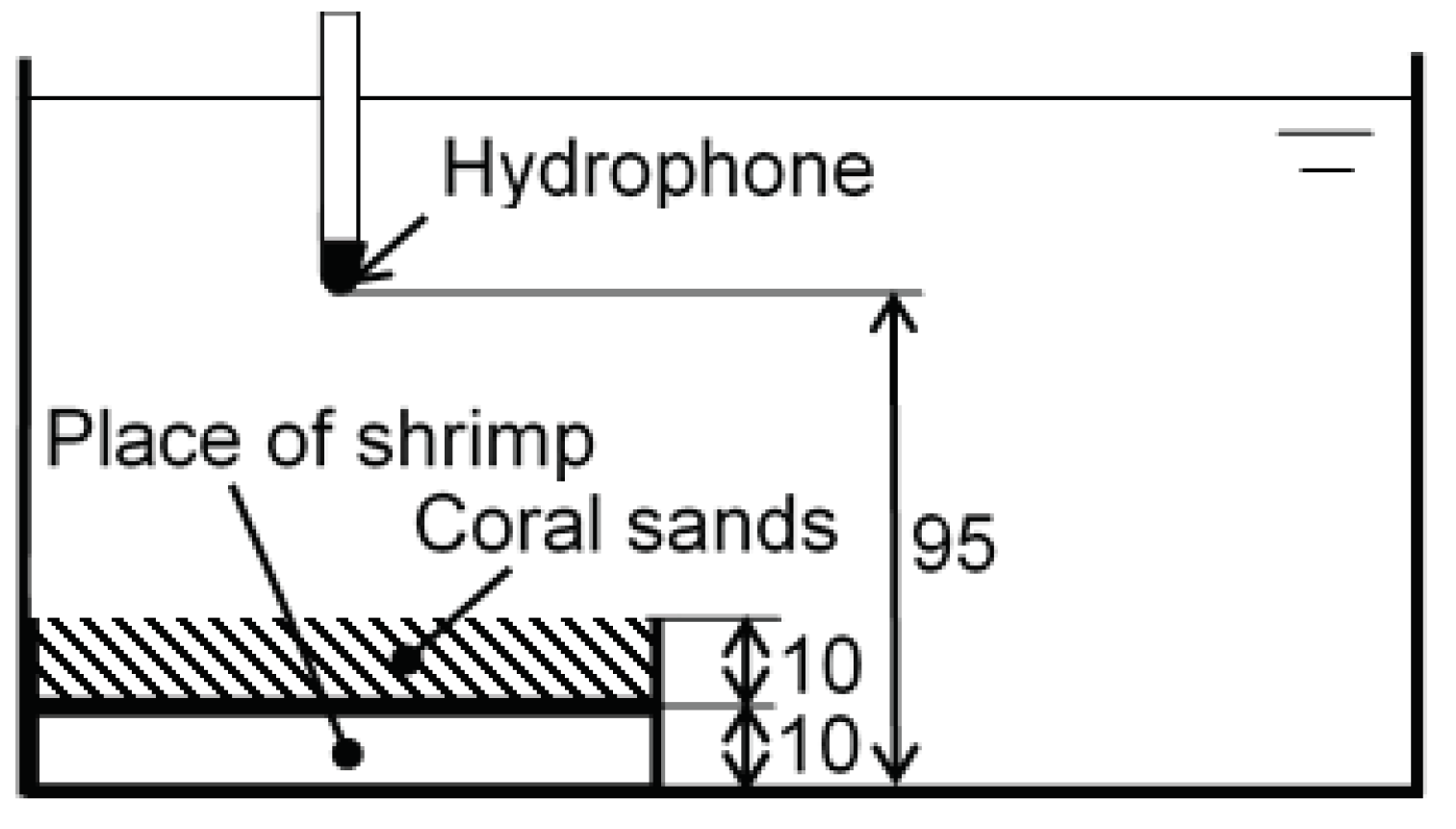

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

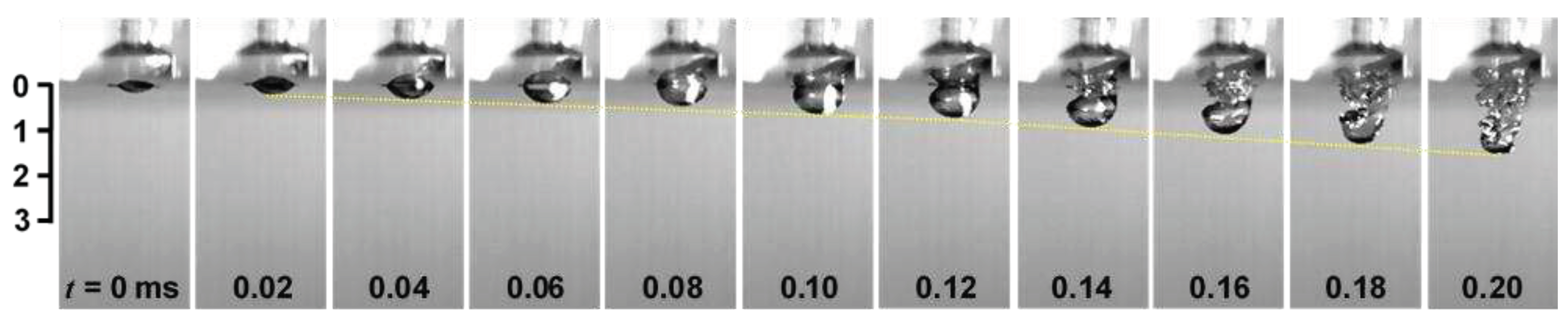

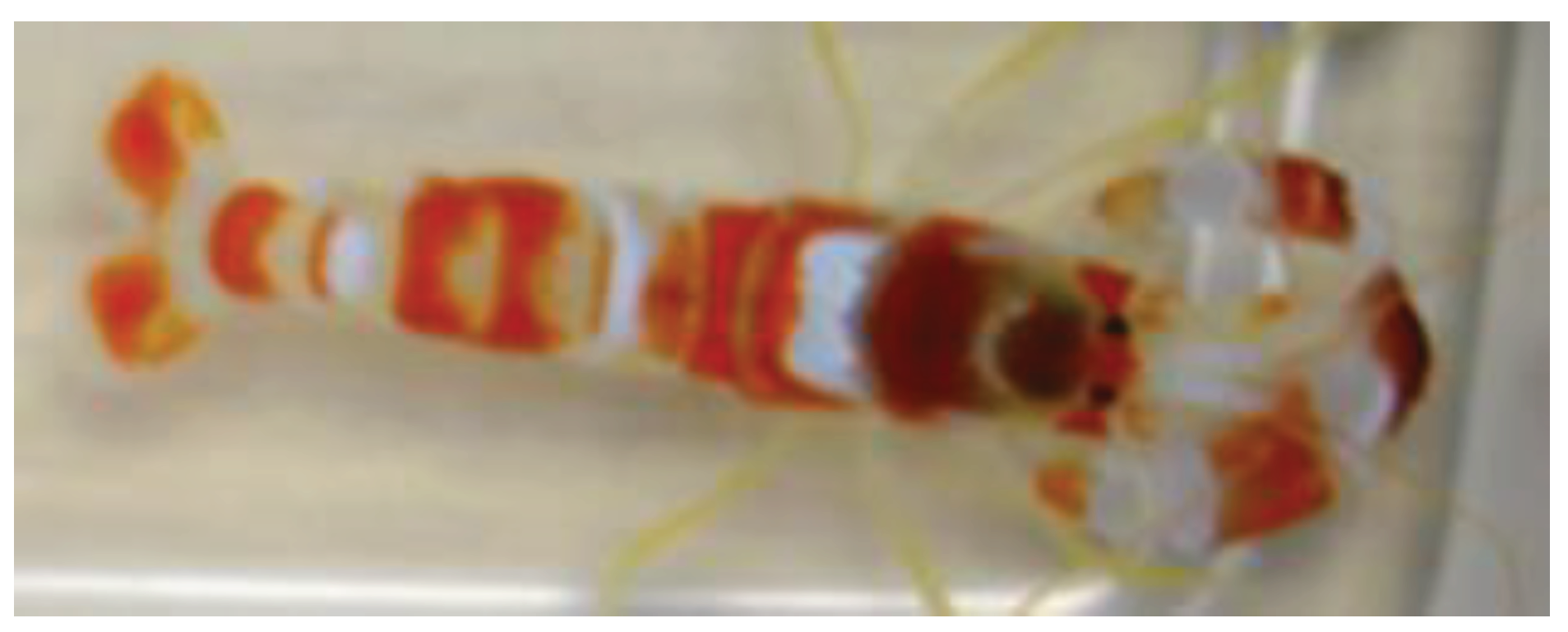

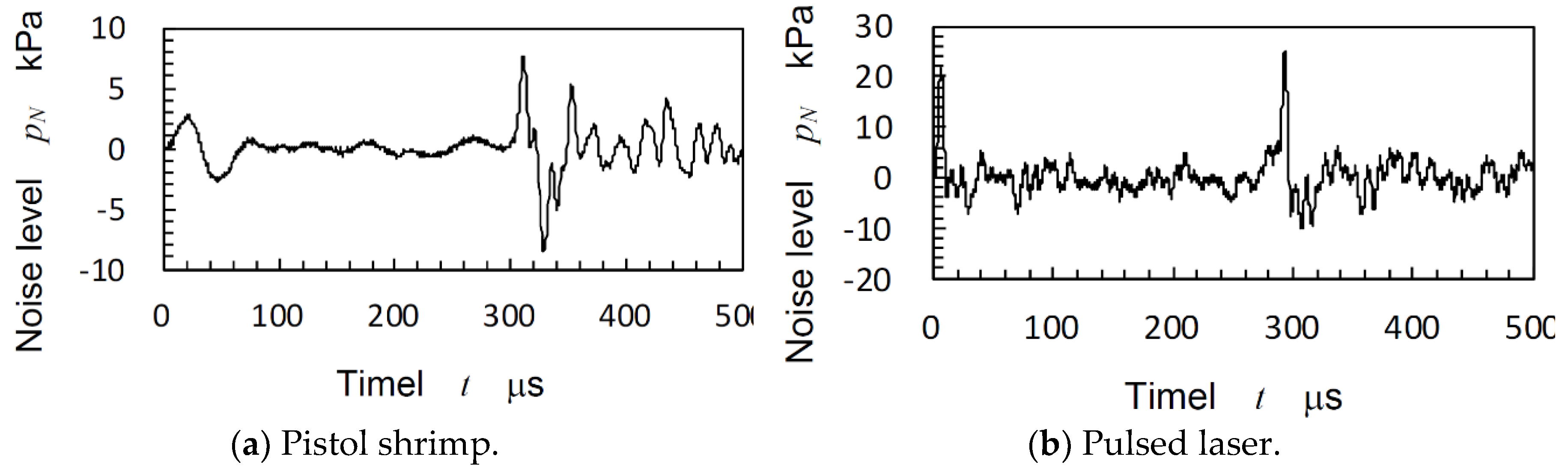

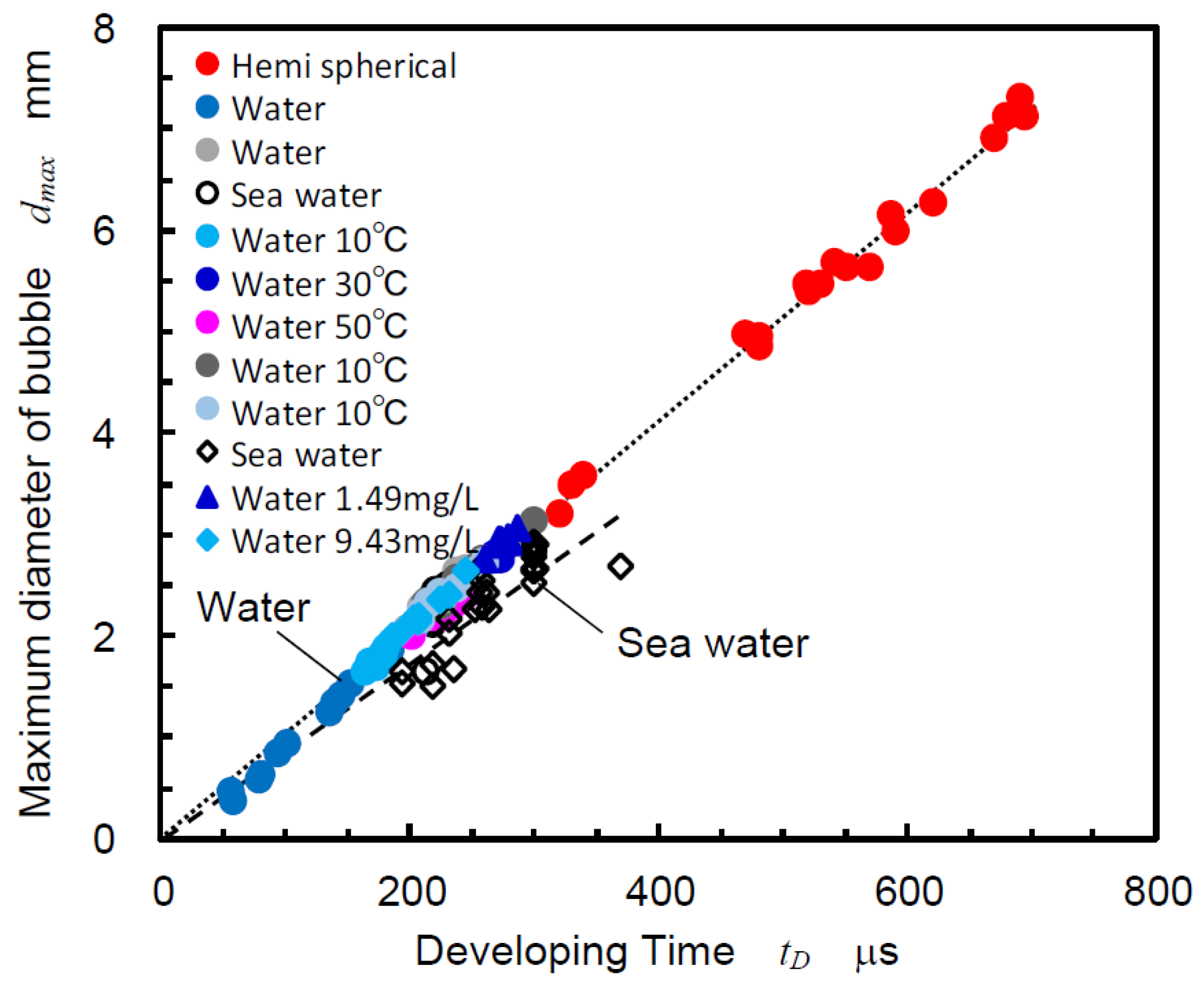

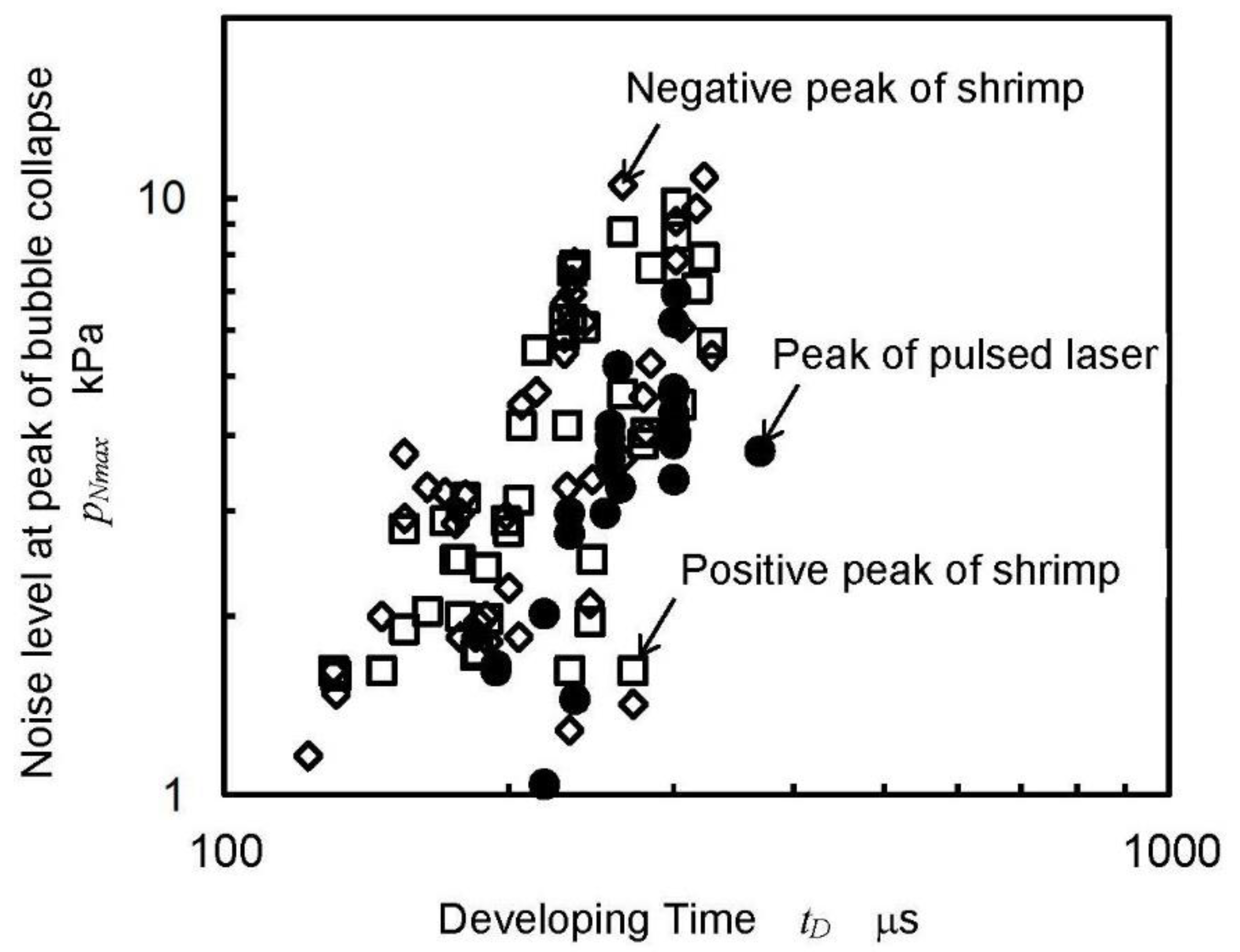

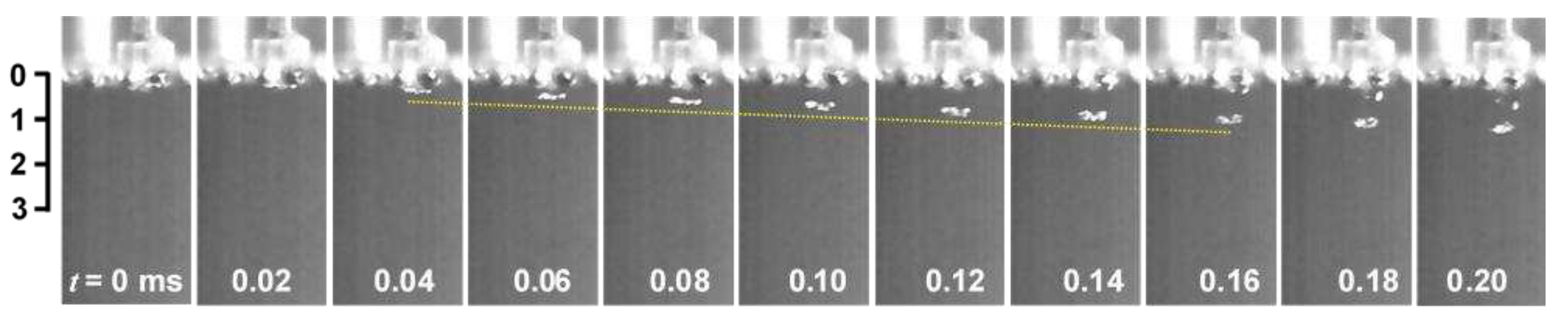

3.1. Cavitation Induced by Pistol Shrimp Comparing with a Pulsed Laser

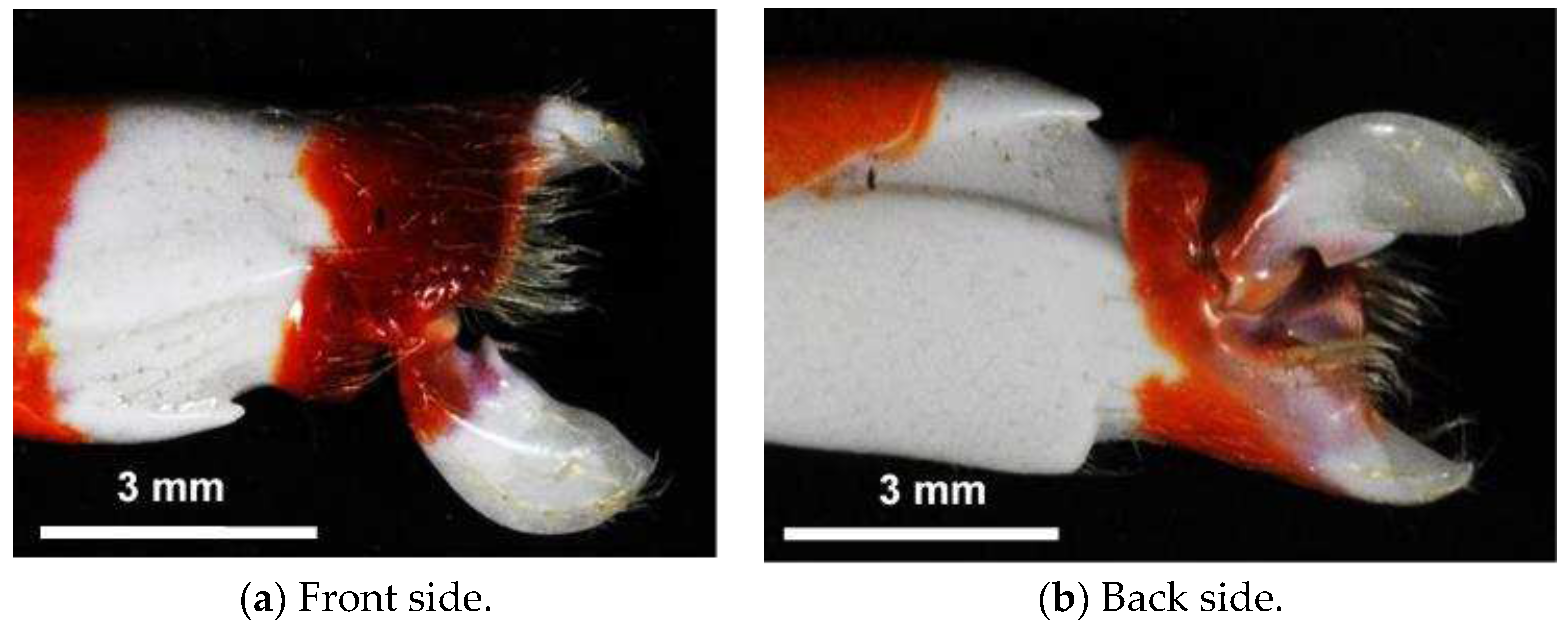

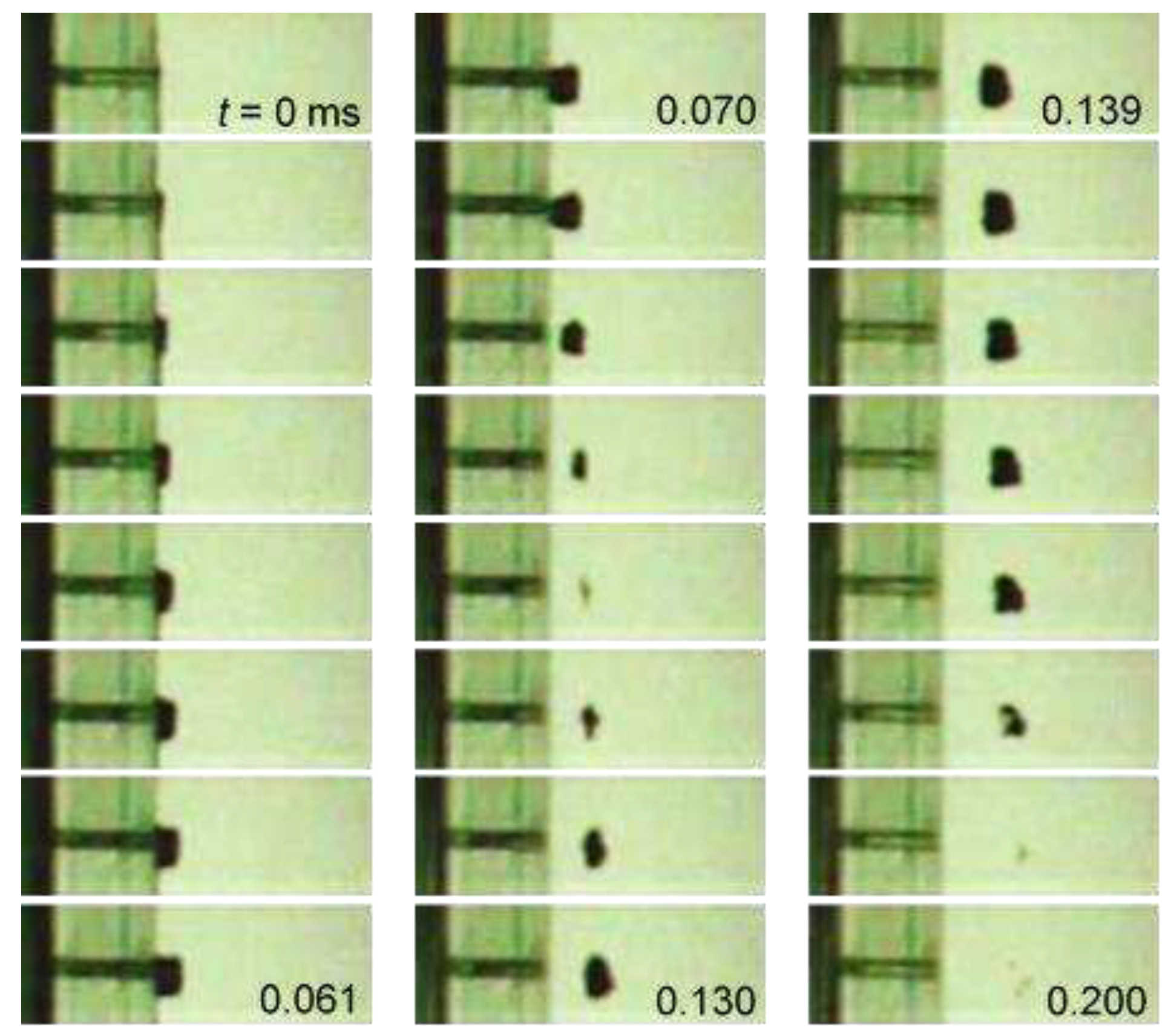

3.2. Development of Cavitation Generator Mimicing Pistol Shrimp

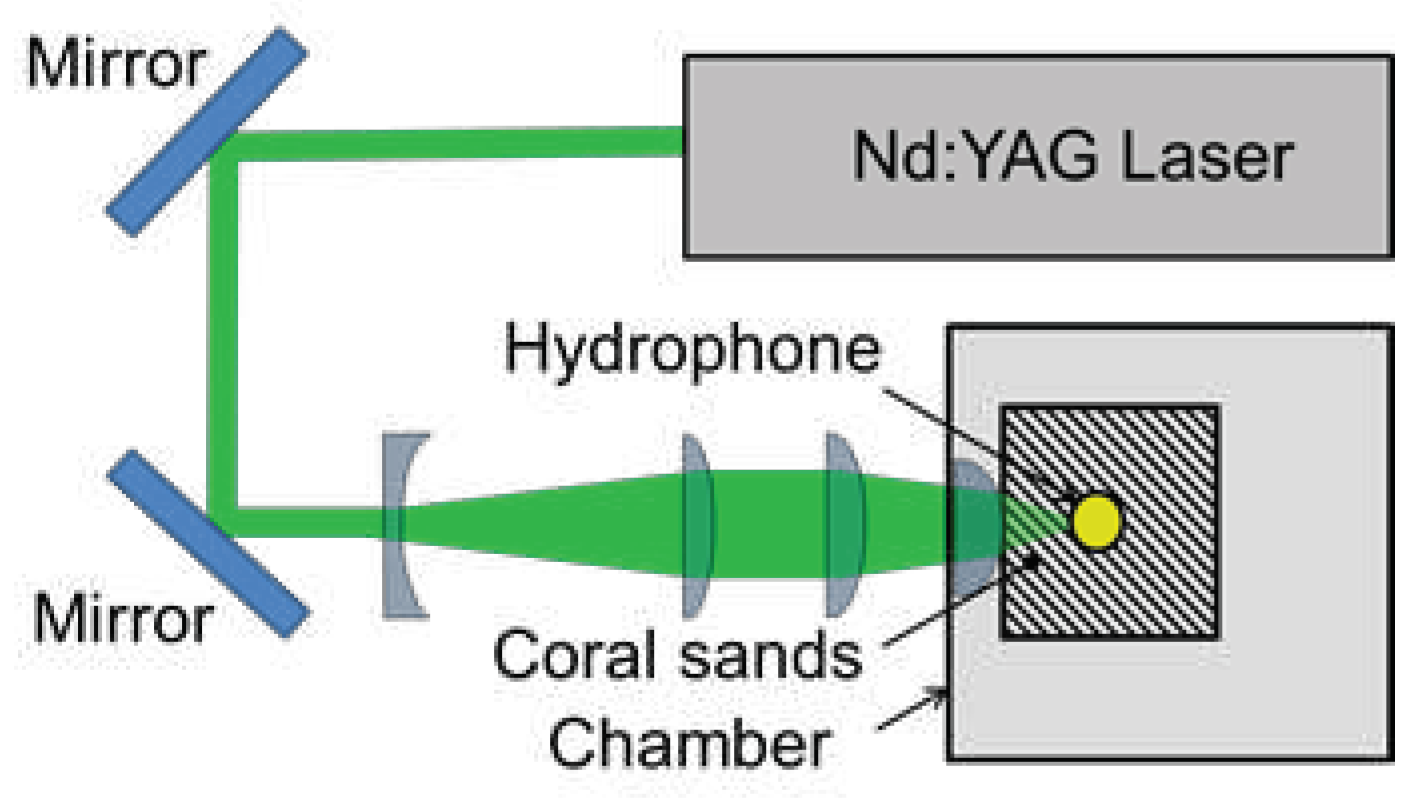

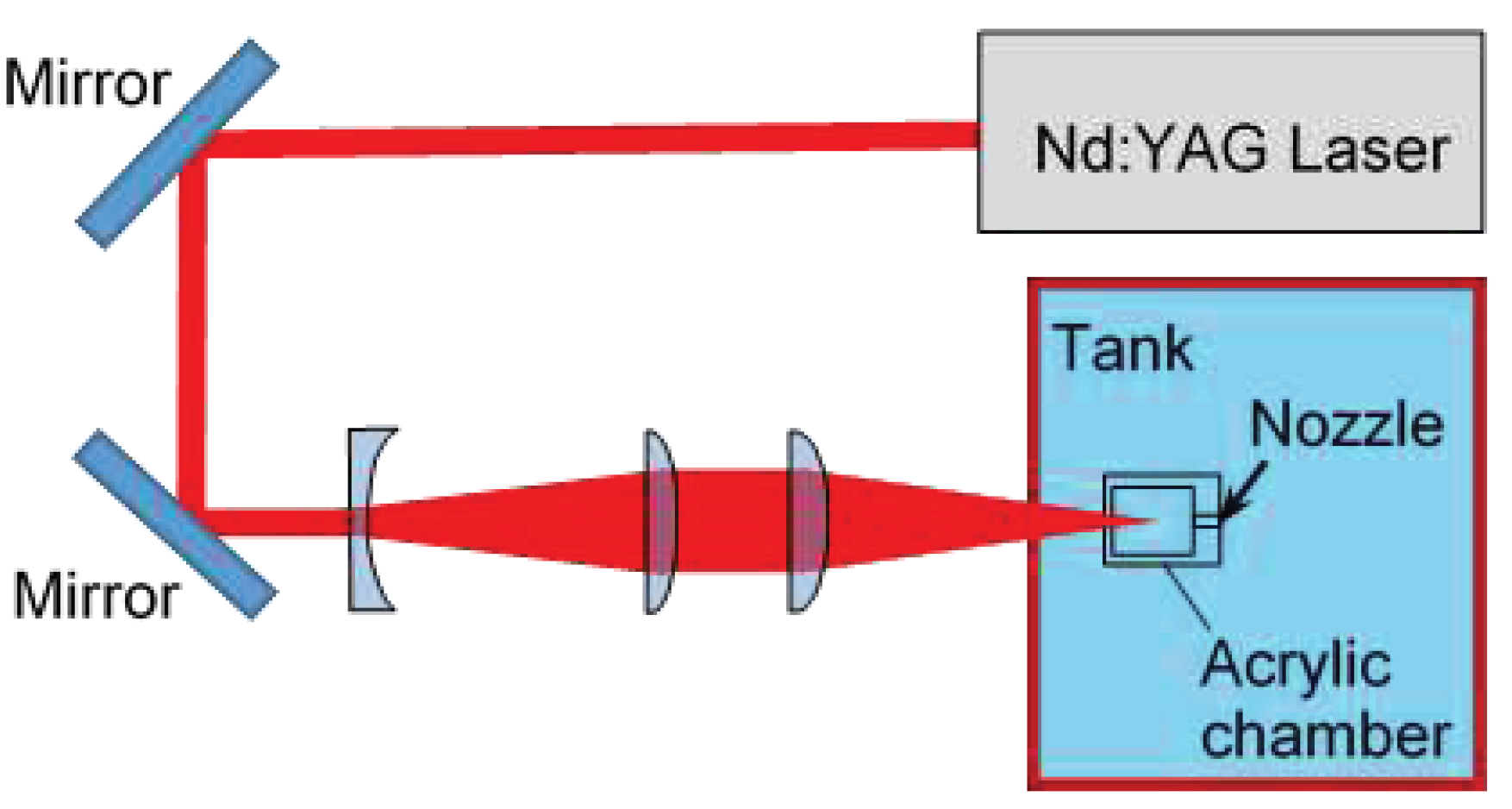

3.2.1. Cavitation generator using pulsed laser

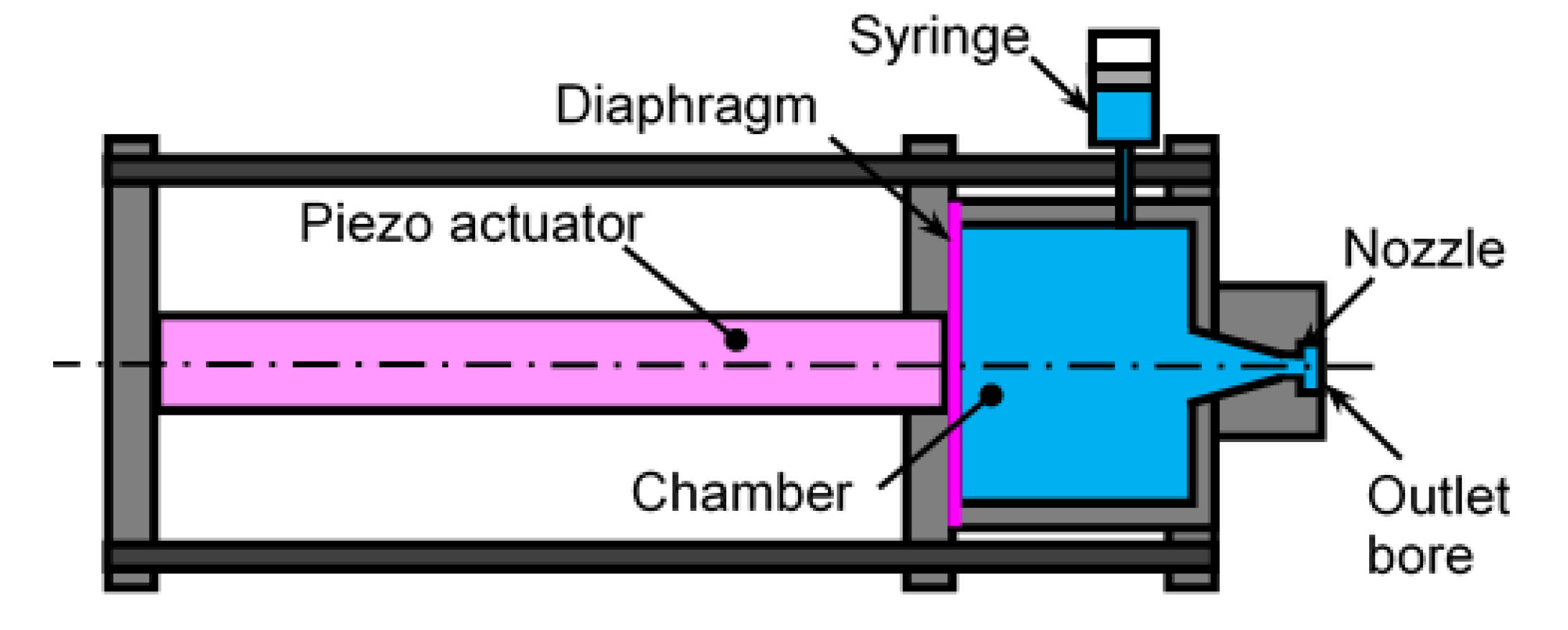

3.2.2. A cavitation generator using a piezo actuator

4. Conclusions

- Pistol shrimps create a cavitation bubble by producing a pulsed water jet, which is generated by the closing of their claws. With respect to the sample pistol shrimp, the volume of the concavo-convex mating area that was required to generate the pulse jet was about 0.35 mm3.

- The size of the cavitation bubble, which was estimated by monitoring the noise, was about 3 mm in diameter, and the volume was 30 times larger than that of the pulsed water jet.

- The required speed for the pulsed water jet to create a cavitation bubble was found to be about 10 m/s.

- The aggressive intensity of the cavitation collapse caused by the pistol shrimp was larger than that of the pulsed laser, even when at an equivalent cavitation volume. This is due to the cushion effect of the pistol shrimp being lesser than that of the pulsed laser.

- The energy efficiency to create a cavitation by a pistol shrimp via a pulsed water jet is about 1,000 times better than that of a pulsed laser.

- A pulsed laser can generate a pulsed water jet, which can thus create cavitations.

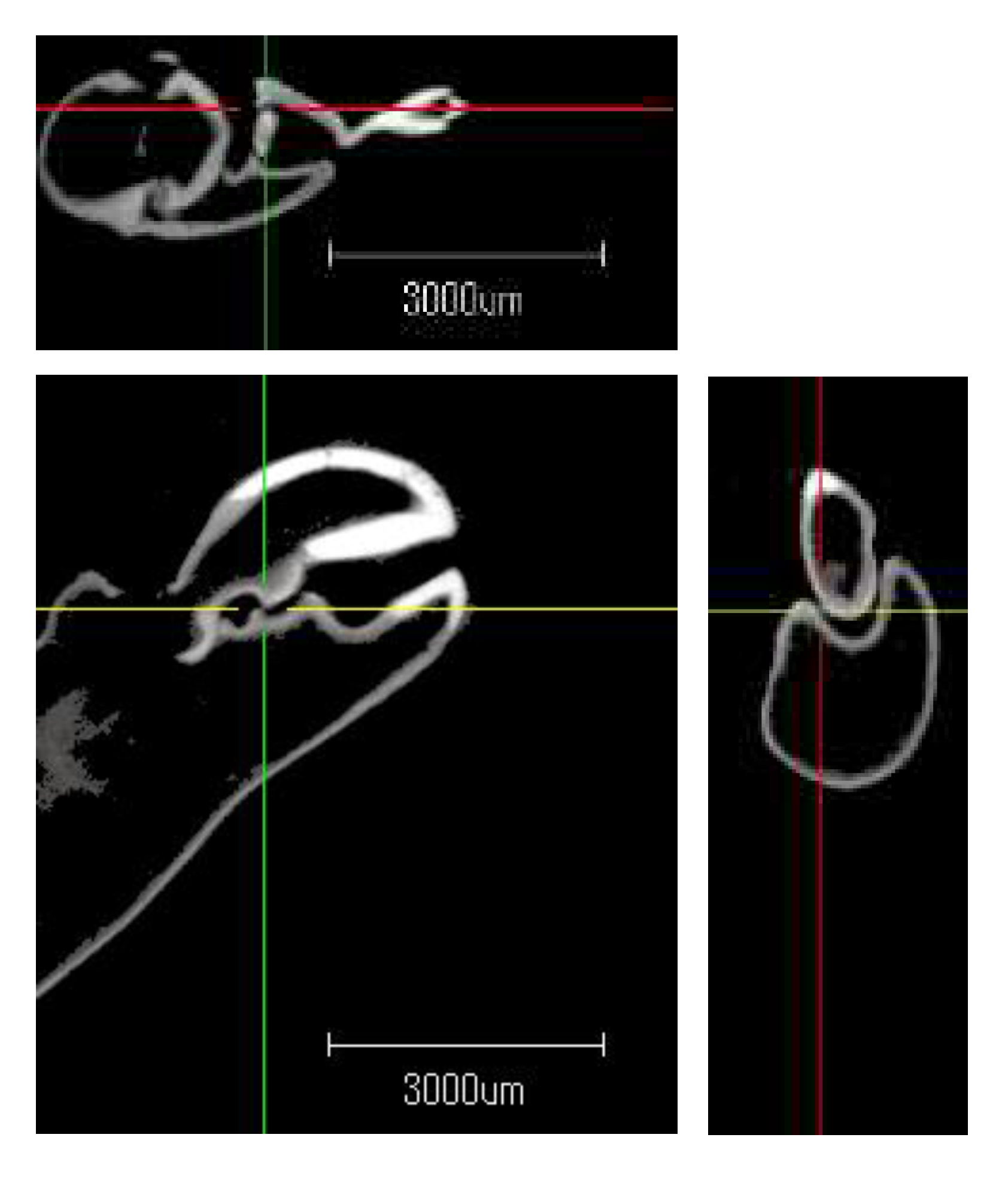

- The cavitation generator was realized by using a piezo actuator, which was designed to mimic the mechanism of a pistol shrimp. The ring vortex cavitation around the pulsed water jet was also observed.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Brennen, C.E. Cavitation and bubble dynamics, Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Knapp, R.T.; Daily, J.W.; Hammitt, F.G. Cavitation, McGraw-Hill, 1970.

- Versluis, M.; Schmitz, B.; von der Heydt, A.; Lohse, D. How snapping shrimp snap: Through cavitating bubbles. Science 2000, 289, 2114–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohse, D.; Schmitz, B.; Versluis, M. Snapping shrimp make flashing bubbles. nature 2001, 413, 477–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillis, A.; Perelman, J.N.; Panyi, A.; Aran Mooney, T. Sound production patterns of big-clawed snapping shrimp (alpheus spp.) are influenced by time-of-day and social context. J Acoust Soc Am 2017, 142, 3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Qin, S.; Di, C.; Qin, J.; Wu, D.; Zhao, J. Research on claw motion characteristics and cavitation bubbles of snapping shrimp. Appl Bionics Biomech 2020, 2020, 6585729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, O.N.; Reichmuth, C. Walruses produce intense impulse sounds by clap-induced cavitation during breeding displays. R Soc Open Sci 2021, 8, 210197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Salas, A.K.; Montie, E.W.; Laferriere, A.; Zhang, Y.; Aran Mooney, T. Sound pressure and particle motion components of the snaps produced by two snapping shrimp species (alpheus heterochaelis and alpheus angulosus). J Acoust Soc Am 2021, 150, 3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, A.C.N.; Woodin, S.A.; Wethey, D.S.; Speiser, D.I. Snapping shrimp have helmets that protect their brains by dampening shock waves. Curr Biol 2022, 32, 3576–3583 e3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinh, J.P.; Patek, S.N. Weapon performance and contest assessment strategies of the cavitating snaps in snapping shrimp. Functional Ecology 2022, 37, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patek, S.N.; Korff, W.L.; Caldwell, R.L. Biomechanics: Deadly strike mechanism of a mantis shrimp - this shrimp packs a punch powerful enough to smash its prey's shell underwater. Nature 2004, 428, 819–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patek, S.N.; Caldwell, R.L. Extreme impact and cavitation forces of a biological hammer: Strike forces of the peacock mantis shrimp odontodactylus scyllarus. J Exp Biol 2005, 208, 3655–3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, X.; Hou, X.; Li, Y.; Meng, Y.; Ma, L.; Tian, Y. Mantis shrimp-inspired underwater striking device generates cavitation. J Bionic Eng 2022, 19, 1758–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, S.; Tadayon, M.; Chua, J.Q.I.; Miserez, A. Multi-scale structural design and biomechanics of the pistol shrimp snapper claw. Acta Biomater 2018, 73, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au, W.W.L.; Banks, K. The acoustics of the snapping shrimp synalpheus parneomeris in kaneohe bay. J Acoustical Soc America 1998, 103, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herberholz, J.; Schmitz, B. Flow visualisation and high speed video analysis of water jets in the snapping shrimp (alpheus heterochaelis). J Comparative Physiology A 1999, 185, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, A.; Ahyong, S.T.; Noël, P.Y.; Palmer, A.R. Morphological phylogeny of alpheid shrimps: Parallel preadaptation and the origin of a key morphological innovation, the snapping claw. Evolution 2006, 60, 2507–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM G32 (2021), Standard test method for cavitation erosion using vibratory apparatus. ASTM standard 2023, 03.02.

- ASTM G134 (2023), Standard test method for erosion of solid materials by a cavitating liquid jet. ASTM standard 2023, 03.02.

- Soyama, H.; Korsunsky, A.M. A critical comparative review of cavitation peening and other surface peening methods. J Mater Process Technol 2022, 305, 117586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delosrios, E.R.; Walley, A.; Milan, M.T.; Hammersley, G. Fatigue-crack initiation and propagation on shot-peened surfaces in A316 stainless-steel. Int J Fatigue 1995, 17, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.P.; Li, Y.J.; Yao, M.; Wang, R.Z. Compressive residual stress introduced by shot peening. J Mater Process Technol 1998, 73, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L. Mechanical surface treatments on titanium, aluminum and magnesium alloys. Mater Sci Eng A 1999, 263, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, M.A.S.; Voorwald, H.J.C. An evaluation of shot peening, residual stress and stress relaxation on the fatigue life of AISI 4340 steel. Int J Fatigue 2002, 24, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClung, R.C. A literature survey on the stability and significance of residual stresses during fatigue. Fatigue Fract Eng Mater Struct 2007, 30, 173–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, Y.; Fukauara, K.; Kohamada, S. Effects of microshot peening on surface characteristics of high-speed tool steel. J Mater Process Technol 2008, 201, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.; Kalvala, P.R.; Misra, M.; Menezes, P.L. Peening techniques for surface modification: Processes, properties, and applications. Materials 2021, 14, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, S.; Minamizawa, K.; Arakawa, J.; Akebono, H.; Takesue, S.; Hayakawa, M. Combined effect of surface morphology and residual stress induced by fine particle and shot peening on the fatigue limit for carburized steels. Int J Fatigue 2023, 168, 107441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherifard, S.; Guagliano, M. Fatigue behavior of a low-alloy steel with nanostructured surface obtained by severe shot peening. Eng Fract Mech 2012, 81, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherifard, S.; Beretta, N.; Monti, S.; Riccio, M.; Bandini, M.; Guagliano, M. On the fatigue strength enhancement of additive manufactured AlSi10Mg parts by mechanical and thermal post-processing. Mater Des 2018, 145, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, A.; Delbergue, D.; Ajaja, J.; Bocher, P.; Levesque, M.; Brochu, M. Effect of different shot peening conditions on the fatigue life of 300 M steel submitted to high stress amplitudes. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 130, 105274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C.S.; Chattopadhyay, K.; Singh, V.; Mahobia, G.S. Enhancement of low-cycle fatigue life of high-nitrogen austenitic stainless steel at low strain amplitude through ultrasonic shot peening. Mater Today Commun 2020, 25, 101576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, E.; Bagherifard, S.; Bandini, M.; Guagliano, M. Surface post-treatments for metal additive manufacturing: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. Addit Manuf 2021, 37, 101619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, H.Y.; Demers, D.; Larose, S.; Perron, C.; Levesque, M. Experimental study of shot peening and stress peen forming. J Mater Process Technol 2010, 210, 2089–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherifard, S.; Ghelichi, R.; Guagliano, M. Numerical and experimental analysis of surface roughness generated by shot peening. Appl Surf Sci 2012, 258, 6831–6840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyama, H. Comparison between the improvements made to the fatigue strength of stainless steel by cavitation peening, water jet peening, shot peening and laser peening. J Mater Process Technol 2019, 269, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Retraint, D.; Sun, Z.; Kanoute, P. Comparative study of the effects of surface mechanical attrition treatment and conventional shot peening on low cycle fatigue of A 316L stainless steel. Surf Coat Technol 2018, 349, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyama, H.; Chighizola, C.R.; Hill, M.R. Effect of compressive residual stress introduced by cavitation peening and shot peening on the improvement of fatigue strength of stainless steel. J Mater Process Technol 2021, 288, 116877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, M.; Curd, M.E.; Soyama, H.; Ungár, T.; Ribárik, G.; Withers, P.J. Depth-profiling of residual stress and microstructure for austenitic stainless steel surface treated by cavitation, shot and laser peening. Mater Sci Eng A 2021, 813, 141037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, G.S.; Schleyer, G.K. Unusual strain rate sensitive behaviour of AISI 316L austenitic stainless steel. J. Strain Anal. Eng. Des. 2004, 39, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.D.; Comstock, R.J.; Mataya, M.C.; van Tyne, C.J.; Matlock, D.K. Effect of strain rate on the yield stress of ferritic stainless steels. Metallurgical and Materials Trans A 2008, 39, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.F.; Hou, Y.L. Dynamic mechanical properties of austenitic 304L stainless steel with different strain rates. Functional Materials 2020, 27, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Husain, A.; La, P.; Hongzheng, Y.; Jie, S. Molecular dynamics as a means to investigate grain size and strain rate effect on plastic deformation of 316 L nanocrystalline stainless-steel. Materials 2020, 13, 3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soyama, H. Cavitating jet: A review. Appl Sci 2020, 10, 7280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyama, H. Luminescence intensity of vortex cavitation in a venturi tube changing with cavitation number. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 71, 105389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawanami, Y.; Kato, H.; Yamaguchi, H.; Maeda, M.; Nakasumi, S. Inner structure of cloud cavity on a foil section. JSME Inter J 2002, 45B, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dular, M.; Petkovšek, M. On the mechanisms of cavitation erosion – coupling high speed videos to damage patterns. Exp Therm Fluid Sci 2015, 68, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyama, H.; Iga, Y. Laser cavitation peening: A review. Appl Sci 2023, 13, 6702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyama, H. Laser cavitation peening and its application for improving the fatigue strength of welded parts. Metals 2021, 11, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.Y.; Luo, C.H.; Ma, P.C.A.; Xu, X.C.; Wu, Y.; Ren, X.D. Study on processing and strengthening mechanisms of mild steel subjected to laser cavitation peening. Appl Surf Sci 2021, 562, 150242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyama, H.; Kuji, C.; Liao, Y. Comparison of the effects of submerged laser peening, cavitation peening and shot peening on the improvement of the fatigue strength of magnesium alloy AZ31. J Magnesium Alloys 2023, 11, 1592–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyre, P.; Fabbro, R.; Merrien, P.; Lieurade, H.P. Laser shock processing of aluminium alloys. Application to high cycle fatigue behaviour. Mater Sci Eng A 1996, 210, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatamleh, O.; Lyons, J.; Forman, R. Laser and shot peening effects on fatigue crack growth in friction stir welded 7075-T7351 aluminum alloy joints. Int J Fatigue 2007, 29, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telang, A.; Gnaupel-Herold, T.; Gill, A.; Vasudevan, V.K. Effect of applied stress and temperature on residual stresses induced by peening surface treatments in alloy 600. J Mater Eng Perform 2018, 27, 2796–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, B.; Liao, Y.L.; Li, L. Abnormal twin-twin interaction in an Mg-3Al-1Zn magnesium alloy processed by laser shock peening. Scr Mater 2019, 165, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Liu, P.; Zhou, L.; He, W.; Pan, X.; An, Z. Review on anti-fatigue performance of gradient microstructures in metallic components by laser shock peening. Metals 2023, 13, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Geng, J.; Wang, Z.; Shao, Z.; Zhang, C.; Chen, D.; Wang, H. Thermal evolutions of residual stress and strain hardening of GH4169 Ni-based superalloy treated by laser shock peening. Surf Coat Tech 2023, 467, 129690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, T.; Zou, S.; Dong, Y.; Ding, H.; Vasudevan, V.K.; Ye, C. A critical review of laser shock peening of aircraft engine components. Adv Eng Mater 2023, 2201451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, Y.; Obata, M.; Kubo, T.; Mukai, N.; Yoda, M.; Masaki, K.; Ochi, Y. Retardation of crack initiation and growth in austenitic stainless steels by laser peening without protective coating. Mater Sci Eng A 2006, 417, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoda, M.; Chida, I.; Okada, S.; Ochiai, M.; Sano, Y.; Mukai, N.; Komotori, G.; Saeki, R.; Takagi, T.; Sugihara, M.; Yoriki, H. Development and application of laser peening system for PWR power plants. Proc 14th Inter Conf Nuclear Eng 2006, 419–424. [Google Scholar]

- Sano, Y. Quarter century development of laser peening without coating. Metals 2020, 10, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, Y.; Akita, K.; Sano, T. A mechanism for inducing compressive residual stresses on a surface by laser peening without coating. Metals 2020, 10, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J.; Špirit, Z.; Vasudevan, V.K.; Steiner, M.A.; Mannava, S.R.; Brajer, J.; Pína, L.; Mocek, T. Effect of laser shock peening parameters on residual stresses and corrosion fatigue of AA5083. Metals 2021, 11, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasoh, A.; Watanabe, K.; Sano, Y.; Mukai, N. Behavior of bubbles induced by the interaction of a laser pulse with a metal plate in water. Appl Phy A 2005, 80, 1497–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyama, H.; Sekine, Y.; Saito, K. Evaluation of the enhanced cavitation impact energy using a PVDF transducer with an acrylic resin backing. Measurement 2011, 44, 1279–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyama, H. Key factors and applications of cavitation peening. Inter J Peen Sci Technol 2017, 1, 3–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sano, Y.; Kato, T.; Mizuta, Y.; Tamaki, S.; Yokofujita, K.; Taira, T.; Hosokai, T.; Sakino, Y. Development of a portable laser peening device and its effect on the fatigue properties of HT780 butt-welded joints. Forces in Mechanics 2022, 7, 100080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, N.; Kugimiya, T.; Seki, T.; Terao, K.; Kunoh, T.; Mizuno, M. Application of ultrasonic cavitation to metal working and surface-treatment of mild-steel. JSME Inter J 1987, 30, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawers, J.C.; McCune, R.A.; Dunning, J.S. Ultrasound treatment of centrifugally atomized 316 stainless steel powders. Metallurgical Transactions A 1991, 22A, 3025–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, M.; Watanabe, T. Introducing compressive residual stress on metal surfaces by irradiating ultrasonic wave with a horn in water : Surface modification by irradiating ultrasonic wave in liquid (report 1). Quarterly Journal of Japan Welding Society 2004, 22, 587–594. [Google Scholar]

- Toh, C.K. The use of ultrasonic cavitation peening to improve micro-burr-free surfaces. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2007, 31, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.B.; Wu, B.X.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, N.G.; Ding, H.T. Ultrasonic cavitation peening of stainless steel and nickel alloy. J Manuf Sci Eng 2014, 136, 014502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, T.; Iwai, Y.; Hattori, S.; Tanimura, N. Relation between impact load and the damage produced by cavitation bubble collapse. Wear 1995, 184, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukouvinis, P.; Bruecker, C.; Gavaises, M. Unveiling the physical mechanism behind pistol shrimp cavitation. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 13994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.; Zhang, C.; Xu, Y.; Heng, J. Structural design and jet-cavitation mechanism of bioinspired snapping-claw apparatus. J Vibration Eng Technol 2021, 10, 649–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Vázquez, M.; Godínez, F.A.; Vicente, W.; Guzmán, J.E.V.; Valdés, R.; Palacios-Morales, C.A. Numerical simulation of a flow induced by the high-speed closure of a bioinspired claw. J Fluids Structures 2022, 113, 103654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Staack, D. Bioinspired mechanical device generates plasma in water via cavitation. Science Advances 2019, 5, eaau7765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajima, K.; Yagi, K.; Mori, Y. Development of an impulsive motion generator inspired by cocking slip joint of snapping shrimp. Bioinspir Biomim 2023, 18, 066002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayleigh, L. On the pressure developed in a liquid during the collapse of a spherical cavity. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science 1917, 34, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyama, H. Effect of nozzle geometry on a standard cavitation erosion test using a cavitating jet. Wear 2013, 297, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohl, C.D.; Lindau, O.; Lauterborn, W. Luminescence from spherically and aspherically collapsing laser induced bubbles. Phys Rev Lett 1998, 80, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).