Submitted:

27 November 2023

Posted:

27 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature review

2.1. Virtual Arrival

- The extent to which vessels can reduce their speed.

- How far in advance of the estimated arrival time vessels receive reliable information.

2.2. Vessel traffic optimisation

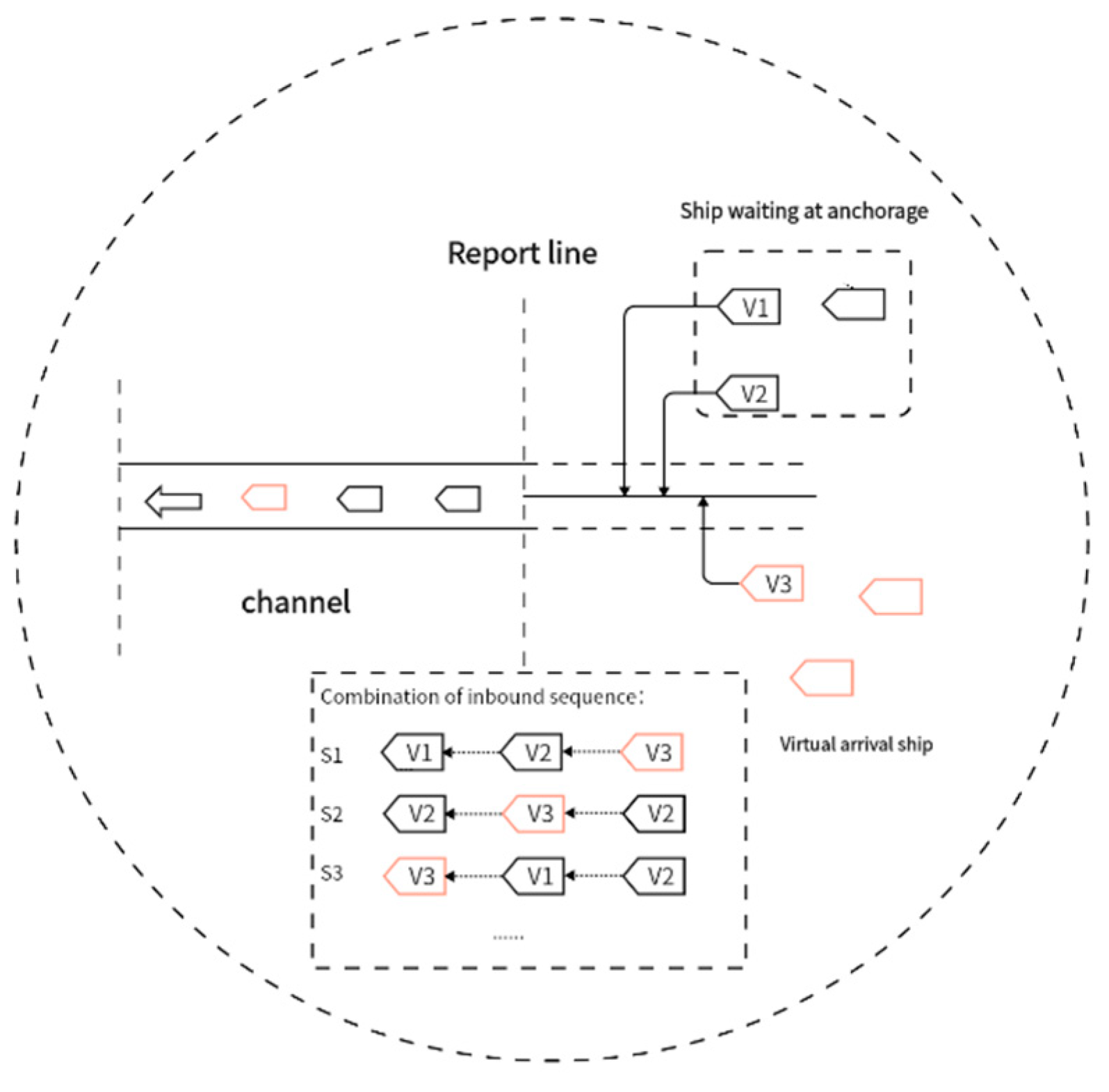

3. Problem description

- Vessel speed limit.

- Port navigation rules.

- Safe time intervals to ensure navigation safety.

- The tidal time window of large vessels.

4. Mathodology

4.1. Vessel fuel consumption calculation

4.2. Modeling approach for implementation of VA

4.3. Model assumptions

4.4. Mathematical model

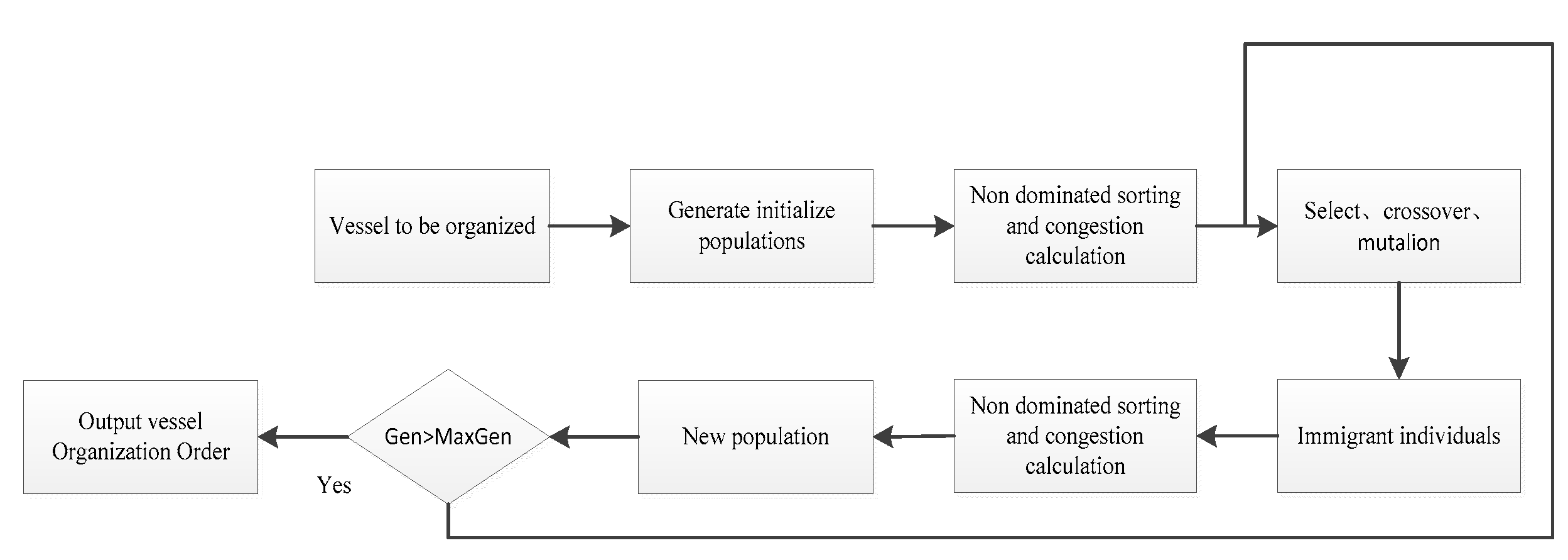

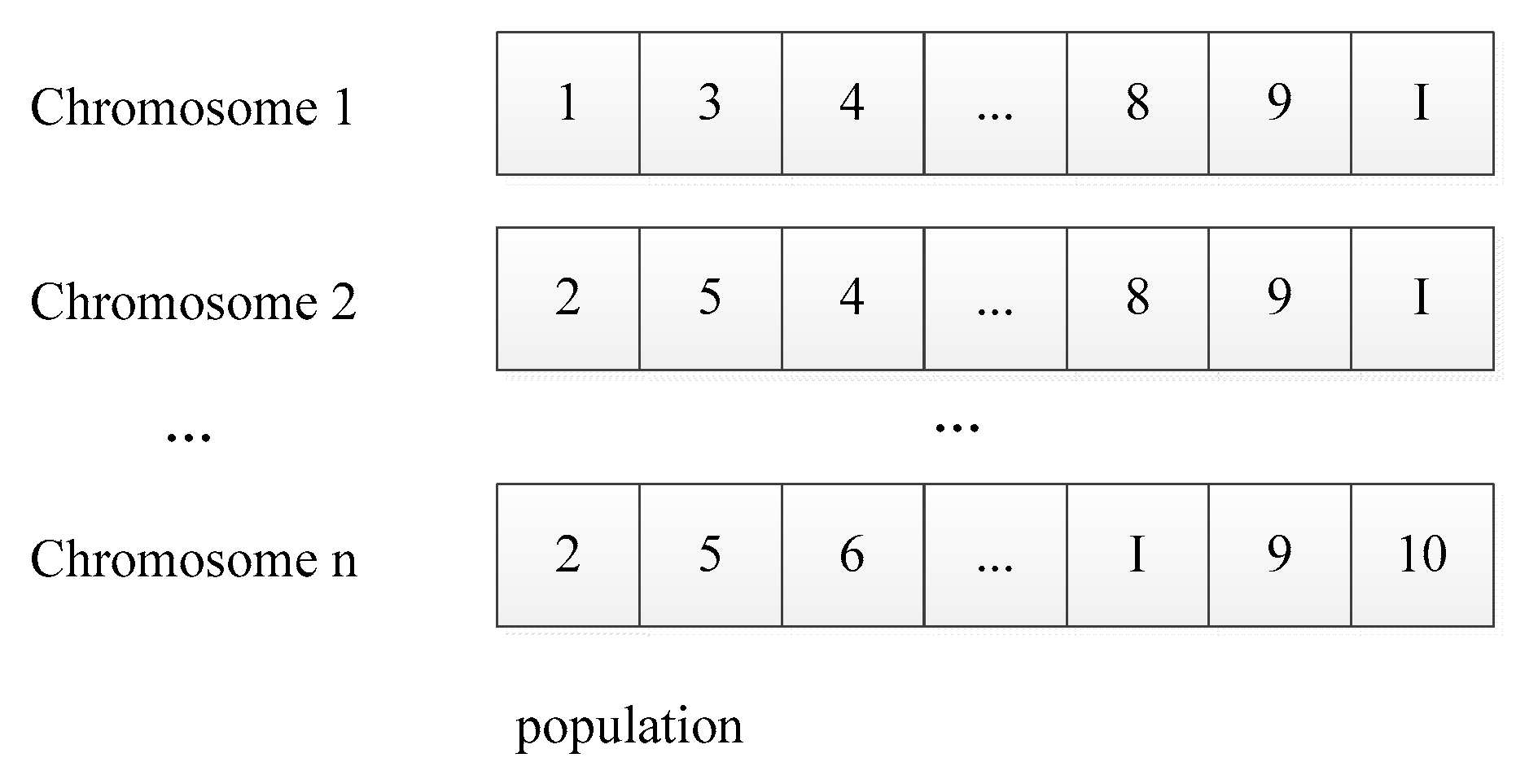

5. Algorithm design

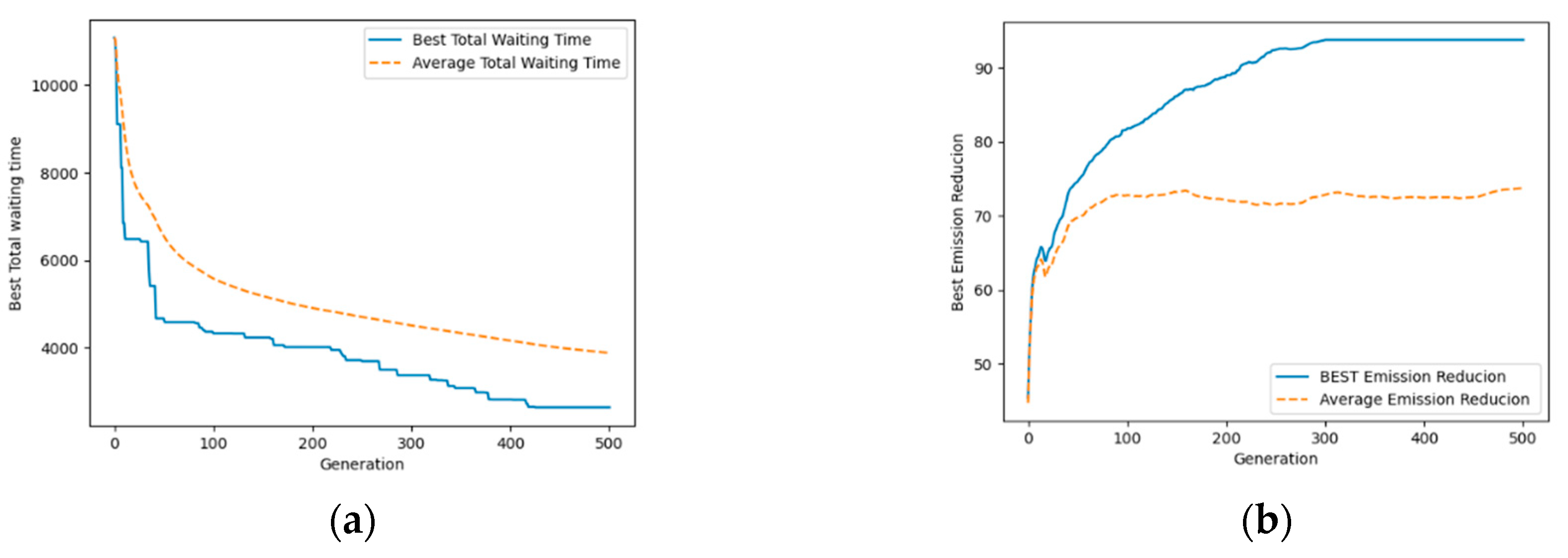

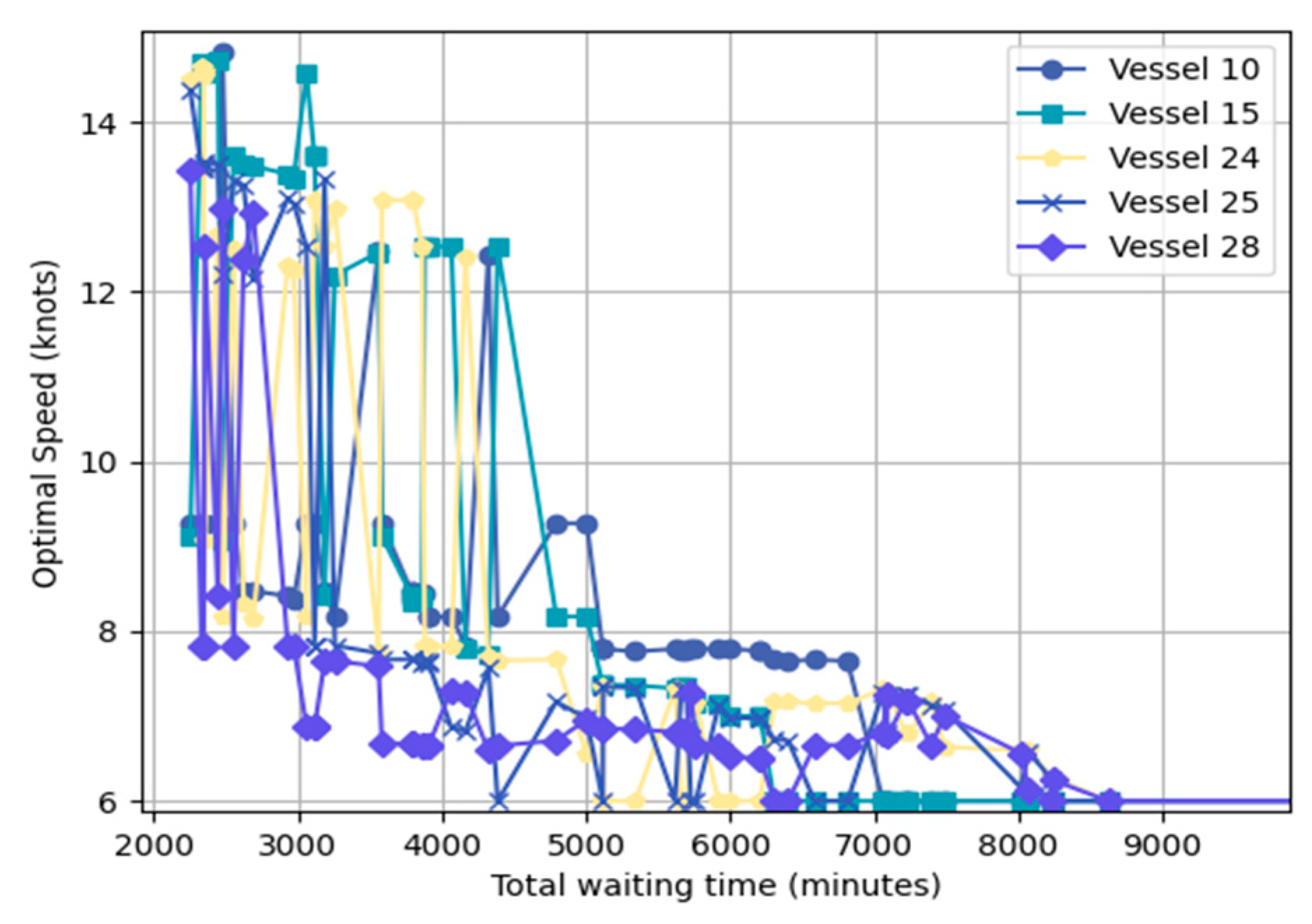

5.1. NSGA-II algorithm.

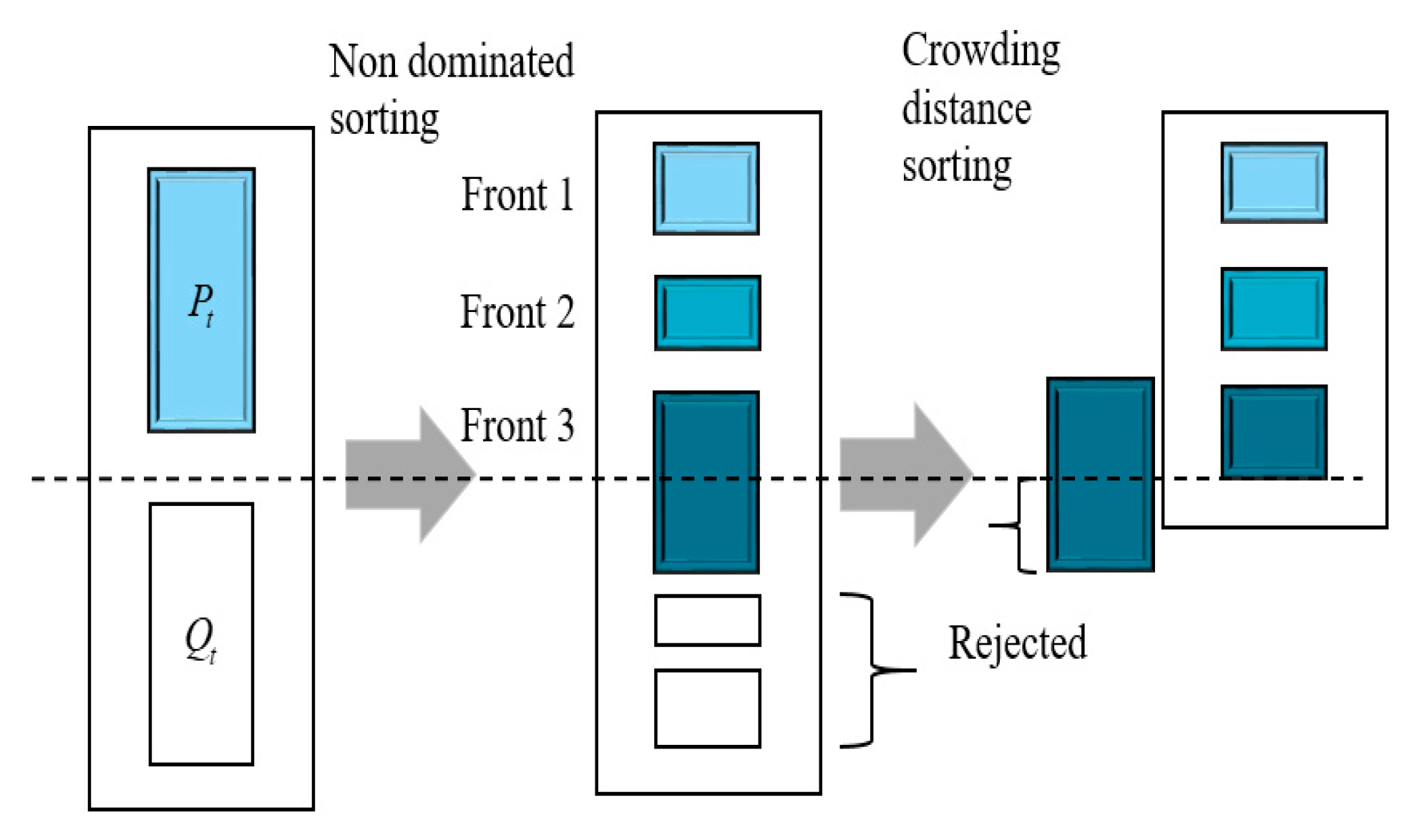

5.3. Non dominated sorting and congestion calculation

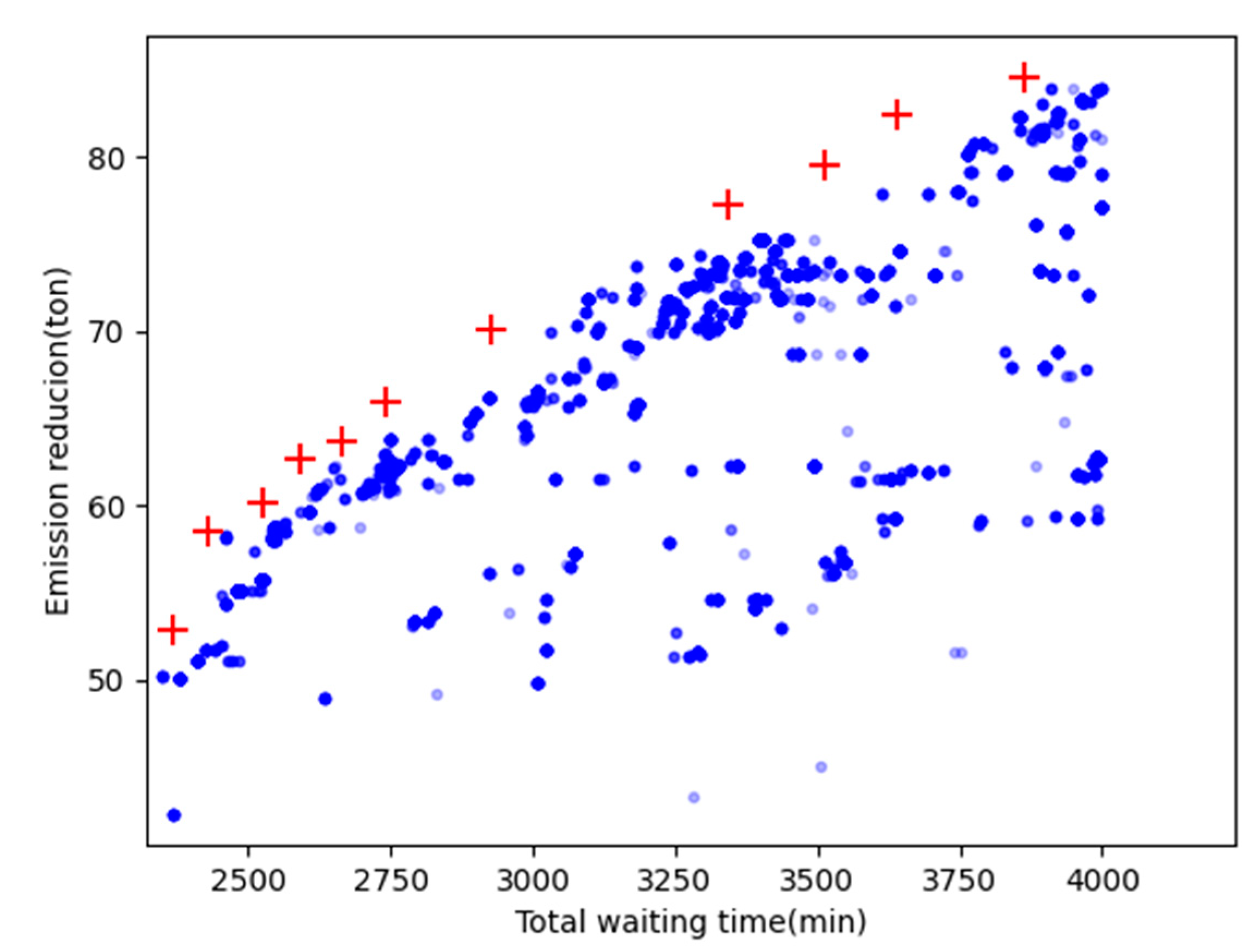

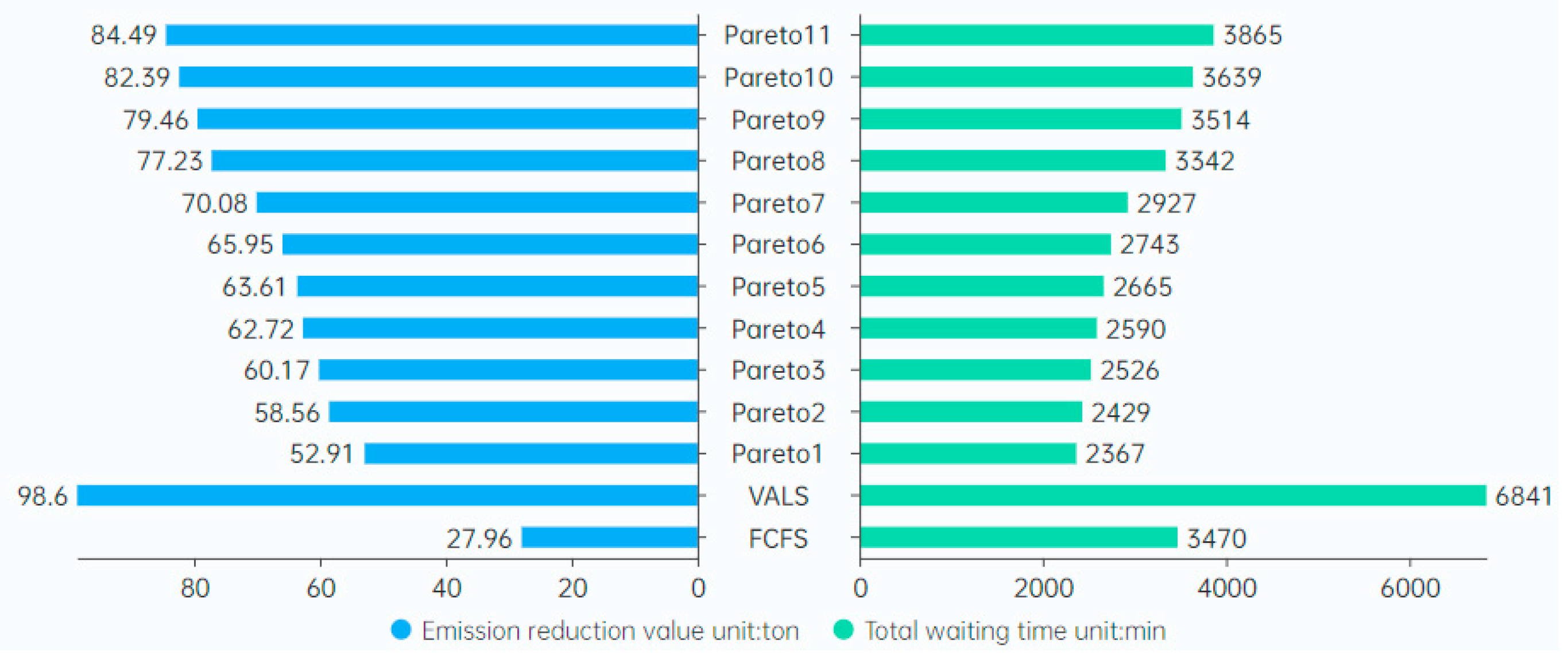

6. Case study

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pettit, S.; Wells, P.; Haider, J.; Abouarghoub, W. Revisiting History: Can Shipping Achieve a Second Socio-Technical Transition for Carbon Emissions Reduction? Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2018, 58, 292–307. [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Ma, W.; Ma, D. Green Maritime: An Improved Quantum Genetic Algorithm-Based Ship Speed Optimization Method Considering Various Emission Reduction Regulations and Strategies. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 385, 135814. [CrossRef]

- Jing, D.; Dai, L.; Hu, H.; Ding, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X. CO2 Emission Projection for Arctic Shipping: A System Dynamics Approach. Ocean & Coastal Management 2021, 205, 105531. [CrossRef]

- Serra, P.; Fancello, G. Towards the IMO’s GHG Goals: A Critical Overview of the Perspectives and Challenges of the Main Options for Decarbonizing International Shipping. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3220. [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, R.T.; Sampson, H. ‘Swinging on the Anchor’: The Difficulties in Achieving Greenhouse Gas Abatement in Shipping via Virtual Arrival. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2019, 73, 230–244. [CrossRef]

- Bui, K.Q.; Perera, L.P.; Emblemsvåg, J. Life-Cycle Cost Analysis of an Innovative Marine Dual-Fuel Engine under Uncertainties. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 380, 134847. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Chen, Q.; Lam, J.S.L.; Xu, Y.; Cao, J.X. Modeling the Impacts of Tides and the Virtual Arrival Policy in Berth Allocation. Transportation Science 2015, 49, 939–956. [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Adland, R.; Prakash, V.; Smith, T. Energy Efficiency with the Application of Virtual Arrival Policy. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2017, 54, 50–60. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Wang, S.; Peng, J. Operational Efficiency Optimization Method for Ship Fleet to Comply with the Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) Regulation. Ocean Engineering 2023, 286, 115487. [CrossRef]

- Fagerholt, K.; Psaraftis, H.N. On Two Speed Optimization Problems for Ships That Sail in and out of Emission Control Areas. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2015, 39, 56–64. [CrossRef]

- Arjona Aroca, J.; Giménez Maldonado, J.A.; Ferrús Clari, G.; Alonso i García, N.; Calabria, L.; Lara, J. Enabling a Green Just-in-Time Navigation through Stakeholder Collaboration. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2020, 12, 22. [CrossRef]

- Merkel, A.; Kalantari, J.; Mubder, A. Port Call Optimization and CO2-Emissions Savings – Estimating Feasible Potential in Tramp Shipping. Maritime Transport Research 2022, 3, 100054. [CrossRef]

- Schroer, M.; Panagakos, G.; Barfod, M.B. An Evidence-Based Assessment of IMO’s Short-Term Measures for Decarbonizing Container Shipping. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 363, 132441. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, H.; Gustafsson, M.; Spohr, J. Emission Abatement in Shipping – Is It Possible to Reduce Carbon Dioxide Emissions Profitably? Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 254, 120069. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, J.F.; Longva, T.; Engebrethsen, E.S. A Methodology to Assess Vessel Berthing and Speed Optimization Policies. Marit Econ Logist 2010, 12, 327–346. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H.; Styhre, L. Increased Energy Efficiency in Short Sea Shipping through Decreased Time in Port. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 2015, 71, 167–178. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, P.; Ivehammar, P. Green Approaches at Sea – The Benefits of Adjusting Speed Instead of Anchoring. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2017, 51, 240–249. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Q.-Q.; He, L.-J.; Tian, H.-W. Ship Traffic Optimization Method for Solving the Approach Channel and Lock Co-Scheduling Problem of the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangzi River. Ocean Engineering 2023, 276, 114196. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhong, M.; Shi, G.; Li, W.; Sui, Y. Vessel Scheduling Model with Resource Restriction Considerations for Restricted Channel in Ports. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2023, 177, 109034. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, B.; Wang, N. Vessel Traffic Scheduling Optimization for Restricted Channel in Ports. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2021, 152, 107014. [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Li, R.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, J. Vessel Traffic Scheduling Optimization for Passenger RoRo Terminals with Restricted Harbor Basin. Ocean & Coastal Management 2023, 246, 106904. [CrossRef]

- Lübbecke, E.; Lübbecke, M.E.; Möhring, R.H. Ship Traffic Optimization for the Kiel Canal. Operations Research 2019, 67, 791–812. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, J.; Guo, Z.; Liu, T. Vessel Transportation Scheduling Optimization Based on Channel–Berth Coordination. Ocean Engineering 2016, 112, 145–152. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zheng, Z. Model and Algorithm for Vessel Scheduling through a One-Way Tidal Channel. Journal of Waterway, Port, Coastal, and Ocean Engineering 2020, 146, 04019032. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, Z.-C.; Sheng, D.; Wang, Y. Integrated Planning of Berth Allocation and Vessel Sequencing in a Seaport with One-Way Navigation Channel. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological 2021, 143, 23–47. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, D. A Model and Algorithm for Vessel Scheduling through a Two-Way Tidal Channel. Maritime Policy & Management 2020, 47, 188–202. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Chen, Q.; Lam, J.S.L.; Xu, Y.; Cao, J.X. Modeling the Impacts of Tides and the Virtual Arrival Policy in Berth Allocation. Transportation Science 2015. [CrossRef]

- Muñuzuri J.; Barbadilla E.; Escudero-Santana A.; Onieva L. Planning Navigation in Inland Waterways with Tidal Depth Restrictions. The Journal of Navigation 2018, 71, 547–564. [CrossRef]

- Rahimikelarijani, B.; Abedi, A.; Hamidi, M.; Cho, J. Simulation Modeling of Houston Ship Channel Vessel Traffic for Optimal Closure Scheduling. Simulation Modelling Practice and Theory 2018, 80, 89–103. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhong, M.; Shi, J.; Li, W.; Sui, Y.; Dou, Y. Overall Scheduling Model for Vessels Scheduling and Berth Allocation for Ports with Restricted Channels That Considers Carbon Emissions. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2022, 10, 1757. [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Guo, Z.; Wang, W.; Jiang, Y. Joint Optimization of Ship Scheduling and Speed Reduction: A New Strategy Considering High Transport Efficiency and Low Carbon of Ships in Port. Ocean Engineering 2021, 233, 109224. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Fang, Z.; Fu, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, J. Literature Review on Emission Control-Based Ship Voyage Optimization. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2021, 93, 102768. [CrossRef]

- Psaraftis, H.N.; Kontovas, C.A. Ship Speed Optimization: Concepts, Models and Combined Speed-Routing Scenarios. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2014, 44, 52–69. [CrossRef]

- Lalla-Ruiz, E.; Shi, X.; Voß, S. The Waterway Ship Scheduling Problem. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2018, 60, 191–209. [CrossRef]

- Unsal, O.; Oguz, C. An Exact Algorithm for Integrated Planning of Operations in Dry Bulk Terminals. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 2019, 126, 103–121. [CrossRef]

- SrinivasN; DebKalyanmoy Muiltiobjective Optimization Using Nondominated Sorting in Genetic Algorithms. Evolutionary Computation 1994. [CrossRef]

| id | length | average_speed | estimated_arrival_time | draft | Virtual vessel |

| 1 | 335 | 9 | 120 | 11 | 0 |

| 2 | 295 | 7.9 | 180 | 11.4 | 0 |

| 3 | 300 | 7.4 | 180 | 13.1 | 0 |

| 4 | 147 | 11 | 250 | 6.7 | 0 |

| 5 | 337 | 12 | 255 | 11.1 | 0 |

| 6 | 304 | 10 | 280 | 10.6 | 0 |

| 7 | 143 | 8 | 300 | 8 | 0 |

| 8 | 172 | 12.8 | 330 | 8.4 | 0 |

| 9 | 289 | 15 | 350 | 13 | 0 |

| 10 | 143 | 8 | 360 | 8 | 1 |

| 11 | 330 | 15 | 365 | 14 | 0 |

| 12 | 399 | 12 | 375 | 14.2 | 1 |

| 13 | 172 | 12.8 | 400 | 8.4 | 0 |

| 14 | 137 | 12.5 | 400 | 10 | 1 |

| 15 | 100 | 7.8 | 425 | 12.6 | 1 |

| 16 | 157 | 8.2 | 436 | 13.8 | 0 |

| 17 | 252 | 6.1 | 438 | 12.5 | 1 |

| 18 | 178 | 6.5 | 442 | 13.7 | 0 |

| 19 | 312 | 13 | 460 | 13.1 | 0 |

| 20 | 173 | 12 | 460 | 10.4 | 1 |

| 21 | 259 | 13.7 | 490 | 10.6 | 0 |

| 22 | 148 | 7.3 | 523 | 12 | 0 |

| 23 | 229 | 7.4 | 550 | 13.1 | 0 |

| 24 | 217 | 16 | 560 | 13.7 | 1 |

| 25 | 223 | 8 | 575 | 12.7 | 1 |

| 26 | 330 | 12 | 600 | 15 | 0 |

| 27 | 200 | 13.3 | 628 | 14 | 0 |

| 28 | 330 | 15 | 630 | 10 | 1 |

| 29 | 180 | 7.1 | 639 | 13.7 | 0 |

| 30 | 217 | 7 | 700 | 12.9 | 0 |

| 31 | 166 | 8 | 730 | 8.8 | 0 |

| 32 | 229 | 7 | 760 | 12 | 0 |

| Serial Number | Veseel order | Emission reduction value (ton) | Total waiting time (min) |

| 1 | [1, 4, 5, 7, 6, 2, 10, 8, 13, 21, 14, 20, 15, 3, 16, 18, 11, 17, 22, 25, 29, 26, 12, 19, 28, 9, 30, 27, 23, 24, 31, 32] | 52.91 | 2367 |

| 2 | [1, 4, 5, 7, 6, 2, 10, 8, 13, 21, 14, 20, 17, 15, 11, 18, 16, 3, 22, 12, 29, 26, 19, 30, 28, 9, 25, 27, 23, 24, 31, 32] | 58.56 | 2429. |

| 3 | [1, 4, 5, 7, 6, 2, 10, 8, 20, 21, 14, 16, 15, 13, 3, 18, 17, 11, 22, 12, 29, 25, 26, 30, 23, 9, 28, 19, 27, 24, 31, 32] | 60.17 | 2526 |

| 4 | [1, 4, 5, 7, 6, 2, 10, 8, 13, 21, 14, 16, 15, 3, 20, 18, 17, 11, 22, 9, 12, 25, 26, 19, 28, 29, 30, 27, 32, 24, 31, 23] | 62.72 | 2590 |

| 5 | [1, 4, 5, 7, 6, 2, 10, 8, 13, 21, 14, 16, 15, 3, 11, 22, 17, 20, 18, 12, 9, 25, 26, 19, 28, 29, 30, 27, 32, 24, 31, 23] | 63.61 | 2665 |

| 6 | [1, 4, 5, 7, 6, 2, 10, 8, 13, 21, 14, 16, 15, 3, 20, 18, 17, 11, 22, 25, 19, 26, 12, 28, 9, 29, 30, 27, 32, 24, 31, 23] | 65.95 | 2743 |

| 7 | [1, 4, 5, 7, 6, 2, 10, 8, 20, 21, 14, 16, 13, 15, 17, 18, 11, 3, 22, 25, 12, 26, 29, 9, 28, 30, 19, 27, 32, 24, 31, 23] | 70.08 | 2927 |

| 8 | [1, 4, 5, 7, 6, 2, 10, 8, 14, 13, 21, 20, 16, 3, 19, 17, 11, 10, 26, 22, 12, 25, 9, 18, 27, 28, 29, 31, 32, 24, 27, 23] | 77.23 | 3342 |

| 9 | [1, 4, 5, 7, 6, 2, 10, 8, 17, 20, 14, 21, 16, 15, 3, 18, 13, 11, 22, 12, 29, 26, 28, 25, 9, 19, 30, 31, 32, 24, 27, 23] | 79.46 | 3514 |

| 10 | [1, 4, 5, 7, 6, 2, 10, 8, 17, 13, 14, 21, 15, 3, 19, 17, 16, 11, 22, 12, 29, 26, 28, 30, 25, 31, 9, 24, 32, 18, 27, 23] | 82.39 | 3639 |

| 11 | [1, 4, 5, 7, 6, 2, 10, 8, 13, 20, 14, 21, 15, 3, 19, 17, 16, 11, 22, 25, 29, 26, 28, 30, 12, 31, 32, 18, 9, 24, 27, 23] | 84.49 | 3865 |

| ID | Estimated_arrival_time(min) | NSGA-II(Pareto1) | FCFS actual_start_time |

VALS |

| 1 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 |

| 2 | 180 | 308 | 331 | 333 |

| 3 | 180 | 499 | 500 | 500 |

| 4 | 250 | 250 | 507 | 766 |

| 5 | 255 | 262 | 509 | 509 |

| 6 | 280 | 353 | 514 | 514 |

| 7 | 300 | 300 | 519 | 425 |

| 8 | 330 | 363 | 522 | 643 |

| 9 | 350 | 664 | 524 | 524 |

| 10 | 360 | 360 | 529 | 768 |

| 11 | 365 | 514 | 532 | 528 |

| 12 | 375 | 648 | 536 | 532 |

| 13 | 400 | 400 | 542 | 538 |

| 14 | 400 | 493 | 544 | 540 |

| 15 | 425 | 497 | 546 | 1230 |

| 16 | 436 | 506 | 548 | 542 |

| 17 | 438 | 518 | 551 | 438 |

| 18 | 442 | 509 | 559 | 442 |

| 19 | 460 | 654 | 564 | 558 |

| 20 | 460 | 495 | 570 | 570 |

| 21 | 490 | 490 | 572 | 563 |

| 22 | 523 | 526 | 575 | 566 |

| 23 | 550 | 708 | 578 | 659 |

| 24 | 560 | 710 | 581 | 1304 |

| 25 | 575 | 575 | 584 | 1306 |

| 26 | 600 | 643 | 600 | 600 |

| 27 | 628 | 706 | 628 | 628 |

| 28 | 630 | 660 | 631 | 1311 |

| 29 | 639 | 639 | 639 | 639 |

| 30 | 700 | 700 | 700 | 700 |

| 31 | 730 | 730 | 730 | 730 |

| 32 | 760 | 760 | 760 | 760 |

| Total waiting time(min) | 2367 | 3454 | 6841 | |

| ID | Initial speed(knots) | Optimal speed(knots) |

| 9 | 17.14 | 9.03 |

| 19 | 13.04 | 9.17 |

| 23 | 16.45 | 13.54 |

| 24 | 15.89 | 13.48 |

| 27 | 14.33 | 12.74 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).