Submitted:

24 November 2023

Posted:

27 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

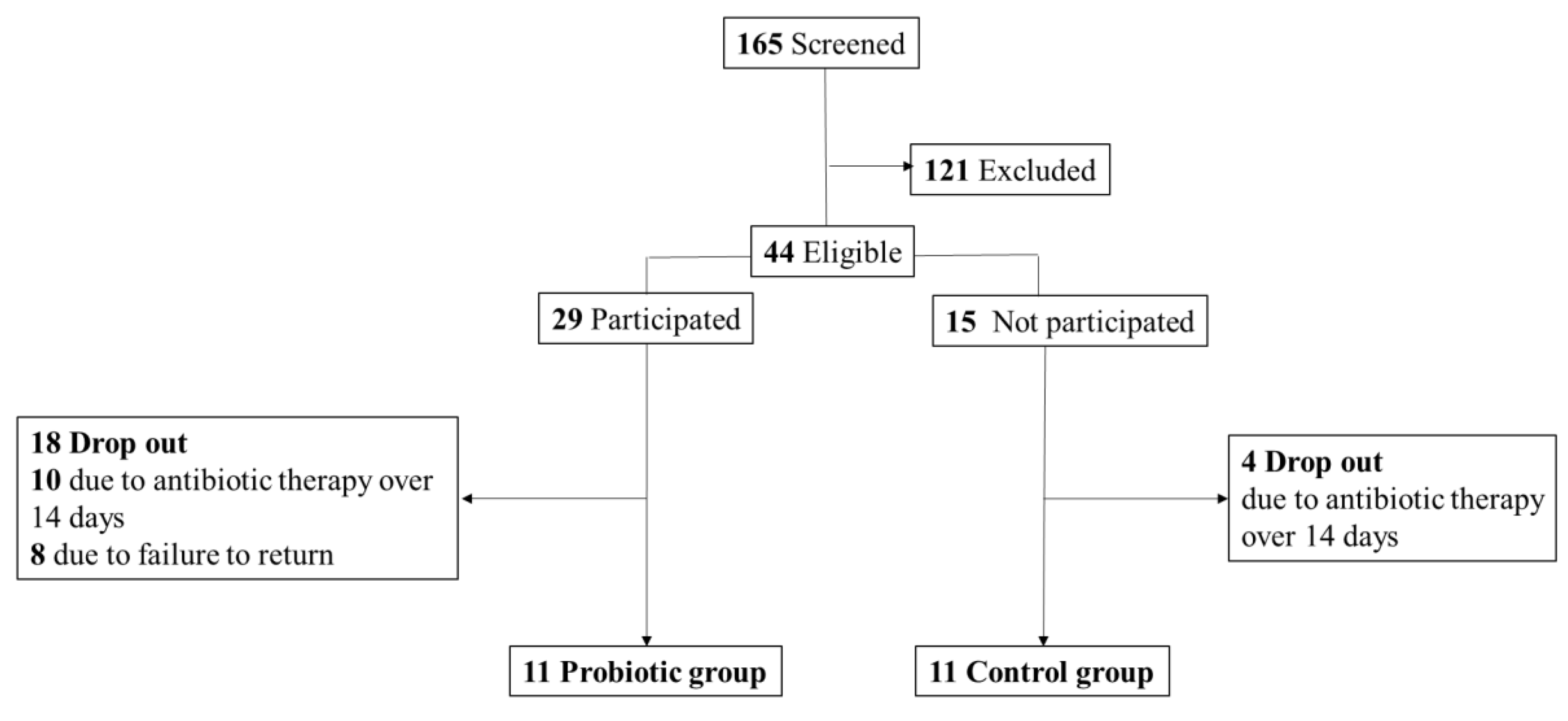

Subjects

Study design

Data collection

Statistical methods

3. Results

| Control (N=11) | Probiotic (N=11) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male sex (%) | 63.6% | 54.5% |

| Body-mass index (kg/m2) | 22.1 ± 4.2 | 21.9 ± 2.6 |

| Age (years) | 83.1 ± 10.3 | 80.0 ± 10.2 |

| Length of hospitalization (days) | 14.9 ± 6.9 | 12.1 ± 6.4 |

| NRS score_initial | 3.7 ± 1.8 | 3.6 ± 1.7 |

| NRS score_discharge | 2.9 ± 1.3* | 2.6 ± 0.9* |

| ICU admission (%) | 27.3% | 45.5% |

| Duration of antibiotic therapy (days) | 10.8 ± 2.9 | 10.3 ± 4.4 |

| Numbers of antibiotics | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 1.0 |

| Antibiotic type, n (%) | ||

| Frequently associated CDI | ||

| Broad-spectrum penicillin | 6 (54.5) | 6 (54.5) |

| Lincosamide | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| 2nd-generation cephalosporin | 3 (27.3) | 4 (36.4) |

| 3rd-generation cephalosporin | 0 (0.0) | 7 (63.6) |

| 4th-generation cephalosporin | 0 (0.0) | 2 (18.2) |

| Occasionally associated CDI | ||

| 1st-generation cephalosporin | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Macrolide | 3 (27.3) | 1 (9.1) |

| Penicillinase-sensitivity penicillin | 1 (9.1) | 1 (9.1) |

| Rarely associated CDI | ||

| Aminoglycoside | 2 (18.2) | 2 (18.2) |

| Vancomycin | 3 (27.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Laboratory data | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.1 ± 1.7 | 11.6 ± 1.9 |

| White blood cells (103/µL) | 8.9 ± 3.9 | 10.9 ± 6.6 |

| % neutrophils | 70.7 ± 14.8 | 75.9 ± 12.0 |

| % lymphocytes | 18.3 ± 11.0 | 13.7 ± 9.3 |

| Cr (mg/dL) | 1.3 ± 1.7 | 0.9 ± 0.6 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 3.5 ± 0.8 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 5.4 ± 4.1 | 6.3 ± 8.7 |

| Na (mEq/L) | 136.0 ± 8.3 | 136.7 ± 10.9 |

| K (mEq/L) | 4.6 ± 1.0 | 3.8 ± 0.4§ |

| CDI occurrence rate | 9.0 % | 0.0% |

| ICU, intensive care unit; NRS, Nutrition Risk Screening; Cr, creatinine; CDI, Clostridium difficile infection.* p<0.05 compared to the NRS score_initial within a group. § p<0.05 showed a significant difference between groups. | ||

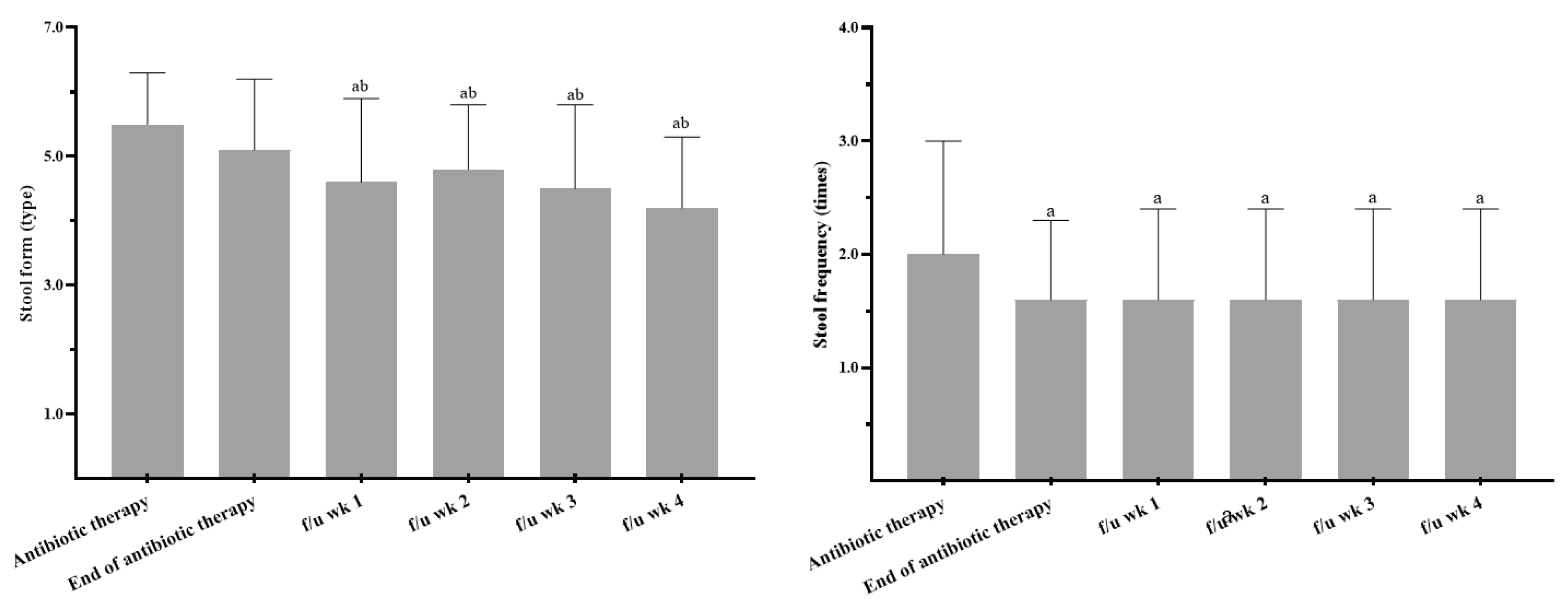

| Stool form | Stool frequency | |||

| Control group | Probiotic group | Control group | Probiotic group | |

| Antibiotic therapy | 5.6 ± 1.4 | 5.5 ± 0.8 | 2.7 ± 2.1 | 2.0 ± 1.0 |

| End of antibiotic therapy | 4.5 ± 1.4a | 5.1 ± 1.1 | 2.4 ± 1.5 | 1.6 ± 0.7a |

| f/u week 1 | 4.3 ± 1.0 | 4.6 ± 1.3ab | 3.0 ± 2.2 | 1.6 ± 0.8a |

| f/u week 2 | 4.3 ± 1.2 | 4.8 ± 1.0ab | 3.0 ± 2.6 | 1.6 ± 0.8a |

| f/u week 3 | - | 4.5 ± 1.3ab | - | 1.6 ± 0.8a |

| f/u week 4 | - | 4.2 ± 1.1ab | - | 1.6 ± 0.8a |

| Antibiotic therapy and end of antibiotic therapy in the probiotic group were with the study product. Stool form: types 1 and 2 indicate constipation, 3 and 4 are ideal stools as they are easier to pass, and 5~7 may indicate diarrhoea and urgency. f/u, follow up. Sample numbers for f/u weeks 1 and 2 in the control group were 4 and 3, respectively. a p<0.05 compared to the beginning of antibiotic therapy within a group using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. b p<0.05 compared to the end of the antibiotic therapy within a group using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. | ||||

| Control | Probiotic | |

|---|---|---|

| Estimate calorie requirement (kcal) | 1512.5 ± 155.3 | 1455.6 ± 113.0 |

| Actual calorie intake (kcal) | 1380.1 ± 289.1 | 1428.6 ± 180.8 |

| Estimate protein requirement (g) | 67.9 ± 9.0 | 68.5 ± 11.5 |

| Actual protein intake (g) | 59.8 ± 15.7 | 62.8 ± 13.4 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Declaration of Competing Interest:

References

- Cai, J.; Zhao, C.; Du, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, Q. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of probiotics for antibiotic-associated diarrhea: Systematic review with network meta-analysis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018, 6, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyne, L.; Farrell, R.J.; Kelly, C.P. Clostridium difficile. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2001, 30, 753–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leffler, D.A.; Lamont, J.T. Clostridium difficile Infection. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015, 372, 1539–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, S.; Hamill, R.J.; Musher, D.M. Treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated disease: old therapies and new strategies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005, 5, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, C.H.; Wu, C.J.; Lee, H.C.; Yan, J.J.; Chang, C.M.; Lee, N.Y.; et al. Clostridium difficile infection at a medical center in southern Taiwan: incidence, clinical features and prognosis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2010, 43, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepin, J.; Valiquette, L.; Cossette, B. Mortality attributable to nosocomial Clostridium difficile-associated disease during an epidemic caused by a hypervirulent strain in Quebec. CMAJ. 2005, 173, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartlett, J.G. Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002, 346, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edes, T.E.; Walk, B.E.; Austin, J.L. Diarrhea in tube-fed patients: feeding formula not necessarily the cause. Am J Med. 1990, 88, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldenberg, J.Z.; Yap, C.; Lytvyn, L.; Lo, C.K.; Beardsley, J.; Mertz, D.; et al. Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017, 12, CD006095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beausoleil, M.; Fortier, N.; Guenette, S.; L'Ecuyer, A.; Savoie, M.; Franco, M.; et al. Effect of a fermented milk combining Lactobacillus acidophilus Cl1285 and Lactobacillus casei in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007, 21, 732–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.W.; Mubasher, M.; Fang, C.Y.; Reifer, C.; Miller, L.E. Dose-response efficacy of a proprietary probiotic formula of Lactobacillus acidophilus CL1285 and Lactobacillus casei LBC80R for antibiotic-associated diarrhea and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea prophylaxis in adult patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010, 105, 1636–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouwehand, A.C.; DongLian, C.; Weijian, X.; Stewart, M.; Ni, J.; Stewart, T.; et al. Probiotics reduce symptoms of antibiotic use in a hospital setting: a randomized dose response study. Vaccine. 2014, 32, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larcombe, S.; Hutton, M.L.; Lyras, D. Involvement of Bacteria Other Than Clostridium difficile in Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhoea. Trends in Microbiology. 2016, 24, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasiri, M.J.; Goudarzi, M.; Hajikhani, B.; Ghazi, M.; Goudarzi, H.; Pouriran, R. Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile infection in hospitalized patients with antibiotic-associated diarrhea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anaerobe. 2018, 50, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abad, C.L.R.; Safdar, N. A Review of Clostridioides difficile Infection and Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2021, 50, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, J. Are Probiotics Money Down the Toilet? Or Worse? Are Probiotics Money Down the Toilet? Or Worse? Are Probiotics Money Down the Toilet? Or Worse? JAMA. 2019, 321, 633–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, C.S.; Chamberlain, R.S. Probiotics are effective at preventing Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of general medicine. 2016, 9, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, S.J.; Heaton, K.W. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 1997, 32, 920–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, M.R.; Raker, J.M.; Whelan, K. Validity and reliability of the Bristol Stool Form Scale in healthy adults and patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. 2016, 44, 693–703. [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.L.; Rello, J.; Marshall, J.; Silva, E.; Anzueto, A.; Martin, C.D.; et al. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. Jama. 2009, 302, 2323–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wischmeyer, P.E.; McDonald, D.; Knight, R. Role of the microbiome, probiotics, and 'dysbiosis therapy' in critical illness. Current opinion in critical care. 2016, 22, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberda, C.; Marcushamer, S.; Hewer, T.; Journault, N.; Kutsogiannis, D. Feasibility of a Lactobacillus casei Drink in the Intensive Care Unit for Prevention of Antibiotic Associated Diarrhea and Clostridium difficile. Nutrients. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, B.C.; Lytvyn, L.; Lo, C.K.; Allen, S.J.; Wang, D.; Szajewska, H.; et al. Microbial Preparations (Probiotics) for the Prevention of Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children: An Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis of 6,851 Participants. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018, 39, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroud, M.; Duncan, H.; Nightingale, J. Guidelines for enteral feeding in adult hospital patients. 2003; 52, (Suppl. S7), vii1–vii12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, P.; Blaser, A.R.; Berger, M.M.; Alhazzani, W.; Calder, P.C.; Casaer, M.P.; et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin Nutr. 2019, 38, 48–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanafer, N.; Vanhems, P.; Barbut, F.; Luxemburger, C.; group CDIS; Demont, C.; et al. Factors associated with Clostridium difficile infection: A nested case-control study in a three year prospective cohort. Anaerobe. 2017, 44, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondrup, J.; Rasmussen, H.H.; Hamberg, O.; Stanga, Z.; Ad Hoc, E.W.G. Nutritional risk screening (NRS 2002): a new method based on an analysis of controlled clinical trials. Clin Nutr. 2003, 22, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, S.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, W.; Liu, X. Bifidobacterium Longum: Protection against Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Journal of immunology research. 2021, 2021, 8030297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quigley, E.M.M. Chapter 16 - Bifidobacterium longum. In The Microbiota in Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology; Floch, M.H., Ringel, Y., Allan Walker, W., Eds.; Academic Press: Boston, 2017; pp. 139–141. [Google Scholar]

- Hutkins, R.; Goh, Y.J. STREPTOCOCCUS|Streptococcus thermophilus. In Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology (Second Edition); Batt, C.A., Tortorello, M.L., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, 2014; pp. 554–559. [Google Scholar]

| Control | Probiotic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | R | p | R | p | |

| ICU admission | Length of hospitalization | 0.23 | 0.54 | 0.33 | 0.32 |

| Duration of antibiotic therapy | 0.30 | 0.38 | 0.21 | 0.54 | |

| Kinds of antibiotics | 0.55 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 0.51 | |

| Stool form_antibiotic therapy | 0.67* | 0.00 | -0.06 | 0.85 | |

| Stool frequency_antibiotic therapy | 0.84* | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.65 | |

| Stool form_end of antibiotic therapy | -0.27 | 0.43 | -0.4 | 0.22 | |

| Stool frequency_end of antibiotic therapy | 0.49 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 1.00 | |

| NRS score_initial | 0.81* | 0.00 | 0.38 | 0.24 | |

| NRS score_discharge | 0.43 | 0.19 | -0.14 | 0.68 | |

| Duration of antibiotic therapy | Stool form_antibiotic therapy | 0.20 | 0.56 | 0.31 | 0.35 |

| Stool frequency_antibiotic therapy | 0.04 | 0.90 | 0.50 | 0.11 | |

| Stool form_end of antibiotic therapy | 0.13 | 0.70 | 0.01 | 0.98 | |

| Stool frequency_end of antibiotic therapy | 0.12 | 0.71 | 0.08 | 0.82 | |

| Stool form_f/u week 1 | -1.00* | 0.00 | -0.18 | 0.60 | |

| Stool frequency_f/u week 1 | 0.95* | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.79 | |

| Stool form_f/u week 2 | -1.00* | 0.00 | -0.06 | 0.09 | |

| Stool frequency_f/u week 2 | 0.87 | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.79 | |

| Numbers of antibiotics | Stool form_antibiotic therapy | 0.52 | 0.10 | -0.22 | 0.51 |

| Stool frequency_antibiotic therapy | 0.52 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.64 | |

| Stool form_end of antibiotic therapy | -0.15 | 0.67 | 0.19 | 0.59 | |

| Stool frequency_end of antibiotic therapy | 0.29 | 0.39 | 0.08 | 0.81 | |

| Stool form_f/u week 1 | -0.09 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.48 | |

| Stool frequency_f/u week 1 | 0.89 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.36 | |

| Stool form_f/u week 2 | -1.00* | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.81 | |

| Stool frequency_f/u week 2 | 0.87 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.36 | |

| *p<0.05 indicates the correlation is significant using Spearman’s correlation. ICU, intensive care unit; NRS, Nutritional Risk Screening; f/u, follow-up. | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).