1. Introduction

The chemical compound space (CCS) is the theoretical space consisting of every possible compound known (and unknown) to us [

1]. Even some of our largest databases consisting of approximately

known substances are a mere drop in the ocean compared to an estimated

substances that possibly make up the CCS [

2]. Needless to say, the next big discovery of a compound that can revolutionize energy storage devices of the future is far from trivial.

The status quo for techniques used in the discovery of new and novel materials to enhance battery technologies has progressed from expensive and time-consuming empirical trial and error methods to the more recent first principles approach of using quantum mechanics (QM) [

3,

4,

5,

6], Monte Carlo simulations and molecular dynamics (MD) [

7,

8,

9,

10]. QM calculations evaluate electron-electron interactions solving the complex Schr

dinger equation, thereby enabling accurate results on a wide variety of properties. However, the computational cost is a bottleneck for molecules larger than a couple hundred atoms. Hence, for multi-component and/or multi-layer structures such as the solid electrolyte interface layer, QM is not a feasible approach. Additionally, many battery components including ionic and polymer electrolytes, crystal structures, and electrode-electrolyte interactions [

8,

11] are better analyzed on larger length and time scales that are inaccessible with QM. MD simulations simplify particle-particle interactions to five main types of interactions, namely, Nonbonded, Bonded, Angle, Dihedral, and Improper interactions. These interactions, which can be obtained using a simple algebraic equation, reduce the computational cost significantly and are applicable to systems almost

times larger. To analyze ion migration in perovskite nickelate with 200 atoms, QM techniques, even using Density Functional Theory (DFT) approximation to reduce computational costs, require about

core-hours of computational time on a picosecond range simulation. On the other hand, MD simulations with 105 atoms required only

core-hours of computational time [

12]. Thus, MD simulations enable the analysis of a wide variety of properties and behavior of materials at the atomic scale, such as crystal structure, thermal properties, and mechanical properties, often too complex to model using QM calculations.

Though MD simulations are widely used to investigate the properties of materials at the atomic level, these simulations rely on experimentally derived interatomic potential parameters that determine the forces between particles [

13]. This dependence on prior experimental data poses a challenge in using MD to design new and novel materials. To address this issue, Lanjan et al. [

14] recently proposed a novel computational framework that couples QM calculations with MD simulations. This generates a wide range of crystal structures by varying a single system parameter (ex. bond length) while keeping other parameters relaxed at their minimum energy level. The QM calculations are then used to evaluate the system’s energy as a function of these changes, and the resulting data points are used to fit the interaction equations to estimate the potential parameters for each type of particle-particle interaction. Employing this framework enables the study of crystal structures with the accuracy of QM calculations but at the speed and system sizes permissible by MD techniques. While this framework enhances nano-based computational methods, the QM calculations still need massive amounts of computational power which can be significantly reduced with the AI-based technique proposed in this work.

The emergence of ML, deep learning (DL) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) has helped alleviate the bottlenecks posed by QM and MD simulations and has made it possible to expand the scope of our search for novel materials in the CCS. ML and DL algorithms are orders of magnitude faster than ab-initio techniques. Unlike the QM-based simulations, that can take days to complete, ML algorithms can produce results within seconds. The use of AI has brought a paradigm shift in research related to improving battery technology as well as molecular property prediction, and material discovery in general. For example, Sandhu et. al. [

15] used DL to examine optimal crystal structures of doped cathode materials in Lithium Manganese Oxide (LMO) batteries. Failed or unsuccessful synthesis data was used to predict the reaction success rate for the crystallization of templated vanadium selenites [

16]. Using QM and ML techniques, Lu et al. [

17] developed a method to predict undiscovered hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites (HOIPs) for photovoltaics. Their screening technique was able to shortlist six HOIPs with ideal bandgap and thermal stability from 5158 unexplored candidates. To identify material compositions with suitable properties, Meredig et al. [

18] built a ML model trained on thousands of ground state crystal structures and used this model to scan roughly 1.6 million candidate compositions of novel ternary compounds to produce a ranked list of 4500 stable ternary compositions that would possibly represent undiscovered materials.

The broad approach employed when using AI-based property prediction models consists of three overarching components: a reference database consisting of relevant quantum-mechanical data which is used to fit the AI model; a mathematical representation that not only uniquely describes the attributes of the reference materials but also enables effective model training; and finally, a suitable AI model that can accomplish the learning task itself. In the ensuing sections, we describe these components in further detail.

1.1. Database

The fundamental premise of AI is the ability to draw inferences from patterns in data and enable an accurate prediction in unknown domains. Hence, the data, that makes up the training examples for our learning task, becomes a critical aspect for successful prediction. With the introduction of the Materials Genome Initiative in 2011, the United States signaled the importance of unifying the infrastructure for materials innovation and harnessing the power of materials data. In lieu of the same goal, there has been an advent of various materials databases, such as the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [

19], the Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) [

20], the Cambridge Structural Databases [

21], the Harvard Clean Energy Project [

22], the Materials Project [

23], and the AFLOWLIB [

24]. Specifically, the size of the training examples, the diversity of the dataset, and the degrees of freedom, all contribute to how effective the learning task for a specific objective can be [

25]. In predicting properties such as band-gap energy and glass-forming ability for crystalline and amorphous materials, Ward et. al. [

26] methodically selected a chemically diverse set of attributes taken from the OQMD. Similarly, for electronic-structure problems, Schütt et. al. [

27] noted that the density of states at the Fermi energy is the critical property of concern. In predicting this property, around 7000 crystal structures from the ICSD were used, observing higher predicted variance for certain configurations and the need to extend the training set in these specific areas. The process of material discovery is complex and diverse, and it is not surprising that there is no one-size-fits-all database that can accurately predict the properties of all materials. The physical and chemical characteristics of materials vary widely, requiring different methods and techniques for precise analysis and prediction. Moreover, the current methodologies rely on the availability of well-curated data or the ability to manually generate such data, which is a daunting and often infeasible task, especially for new and unexplored materials. Thus, there is a need to develop generalizable and adaptable approaches that can efficiently handle a diverse range of materials, properties, and configurations, without the need for extensive data generation or curation.

1.2. Molecular Representation

ML algorithms draw inferences from data to establish a relationship between atomic structure and the properties of a system. To enable the best possible structure-property approximation, a good representation of the material (also referred to as the ‘fingerprint’ or ‘descriptor’) is crucial. The first Hohenberg-Kohn theorem of DFT proves that the electron density of a system contains all the information needed to describe its ground state properties, and it is a "universal descriptor" that can be used to predict these properties without knowledge of the details of the interactions between the electrons [

28]. Crucially, for ML, a good molecular representation is invariant to rotation and translation of the system, and to permutation of atomic indices [

29]. Therefore, unfortunately, electronic density is not a universally suitable representation of a system. Additionally, a good descriptor must be unique, continuous, compact, and computationally cheap [

29]. Often, there are multiple molecular geometries that possess similar values for a property. Hence, there is no single universal representation for all properties leading to hundreds of molecular descriptors that are suitable only for a small subset of the CCS and a small subset of properties [

30]. A commonly used molecular representation that satisfies the above-mentioned criteria of a good representation is the ‘Coulomb matrix’. It uses the same parameters that constitute the Hamiltonian for any given system, viz., the set of Cartesian coordinates, R

I, and nuclear charges, Z

I [

31]. While the coulomb matrix representation has shown tremendous success for property prediction in finite systems, it is unable to do the same for infinite periodic crystal structures [

27]. Hansen et. al. [

32] proposed a new descriptor called ‘bag-of-bonds’ that performed better due to incorporating the many-body interactions of a system. In fact, the use of different descriptors in an ML endeavor for material property prediction is so common that there are open-source software packages that provide implementations for a myriad of different descriptors [

29]. Unfortunately, a lack of clarity on the right descriptor makes the use of AI inaccessible to researchers that possess domain expertise but lack the needed knowledge of AI. Additionally, the lack of generalizability of a chosen descriptor makes the current AI-based techniques inaccurate and narrow-scoped. Overcoming these challenges, the novel technique proposed in this work makes material discovery and property prediction easier and more accessible without the time-consuming process of selecting a suitable descriptor. Specifically, our approach leverages a 2-stage process combining AI with MD simulations.

1.3. AI Model

In addition to an appropriate database and the precise molecular representation, a critical aspect in the material property prediction process is the choice of the AI algorithm. AI algorithms can be categorized into supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning. Supervised learning uses a standard fitting procedure that attempts to determine a mapping function between known input features and the corresponding output labels. The goal is to make accurate predictions for new, unseen data. In contrast, unsupervised learning does not have prior knowledge of the desired output, and goal is to find patterns and structures in this unlabeled data. Reinforcement learning uses an iterative trial-and-error process where the actions are determined based on reinforcement in the form of a reward-penalty system. The goal here is to maximize the cumulative reward over time. Supervised learning is the most widespread category of learning used in materials research. Different models may be better suited for certain types of materials or properties, and the choice of model often depends on the available data and the specific goals of the prediction task. Akbarpour et. al. [

33] found that Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) performed better in predicting the synthesis conditions of nano-porous anodic aluminum oxide at the interpore distance in comparison to both Multiple Linear Regression and experimental studies. On the other hand, for the modelling and synthesis of zeolite synthesis, Manuel Serra et. al. [

34] found that Support Vector Regression (SVR) outperformed ANNs and decision trees. Fang et. al. [

35] proposed a novel hybrid methodology for forecasting the atmospheric corrosion of metallic materials where the optimal hyperparameters for an SVR model were automatically determined using a Generic algorithm. These examples highlight the need for AI expertise when choosing the right algorithm for a given application, which can be a barrier to making AI methods accessible for materials-based research.

In this work, we have presented a ML model to predict nonbonded potential parameters for conventional elements in the periodic table. We propose a novel approach that uses ML to learn a common empirical non-bonded interatomic potential, the Buckingham potential [

36], and we successfully demonstrate the ability of this machine-learned potential to predict a wide range of properties when used as an input to classical MD simulations. We also demonstrate a marked improvement in the time taken to determine such properties compared to a traditional first principles approach.

2. Materials and Methods

Due to the enormity of the CCS, it is impossible to generate exhaustive datasets and consequently difficult for AI models to generalize well beyond the dimensional space of the training data. Additionally, the lack of a general representation that can scale well to very different properties results in AI-based techniques that fail to provide both the accuracy and the generalizability that comes with ab-initio techniques. Therefore, it is essential to use techniques that combine the speed of AI with the accuracy and generalizability of QM and MD simulations [

37]. Hence, while most AI-based approaches follow the 3-step process described above to predict a confined set of properties in a narrow subset of the CCS, our approach generalizes well to a large set of properties. We delve into the details of our process in the ensuing paragraphs.

2.1. Database Generation

To train our ML model, we generated a database employing the QM approach and Quantum Espresso (QE) software package [

38,

39,

40]. QE uses the principles of QM and computational methods to solve the Schrödinger equation using DFT approximation and can predict the electronic structure and properties of a system at the atomic scale. The database consists of QE generated non-bonded atom-pair energies for each element in the periodic table. Self-consistent field calculations (QE configurations in

Table 1) were performed for every possible same atom-pair system. Further, for each atom-pair, various plausible total charges, each with multiple inter-atomic distances were considered. We refer to each such combination of atom-pairs with their respective total charge as a system-charge configuration. The inter-atomic distance in each simulation was chosen to include different energy levels, from extremely close and unstable to far apart. There were more data points around the equilibrium range and fewer at farther distances. By exploring identical atom-pair combinations for each element in the periodic table and introducing a range of charge values for each atom-pair, we conducted simulations for 340 unique system-charge configurations. For each configuration, we evaluated interactions over 20 different distances, totaling nearly 700 hours of computational time. This effort resulted in the creation of a comprehensive database comprising non-bonded atom-pair energies for 6,400 distinct configurations. It must be noted that not all system-charge configurations were simulated with the same number of distance values. Some systems with larger elements may be unstable at close distances, and the QM simulations will not work well for those cases. Similar behavior may be seen for systems with higher charge values owing to the repulsion between atoms.

2.2. Data Preprocessing

2.2.1. Curve Fitting:

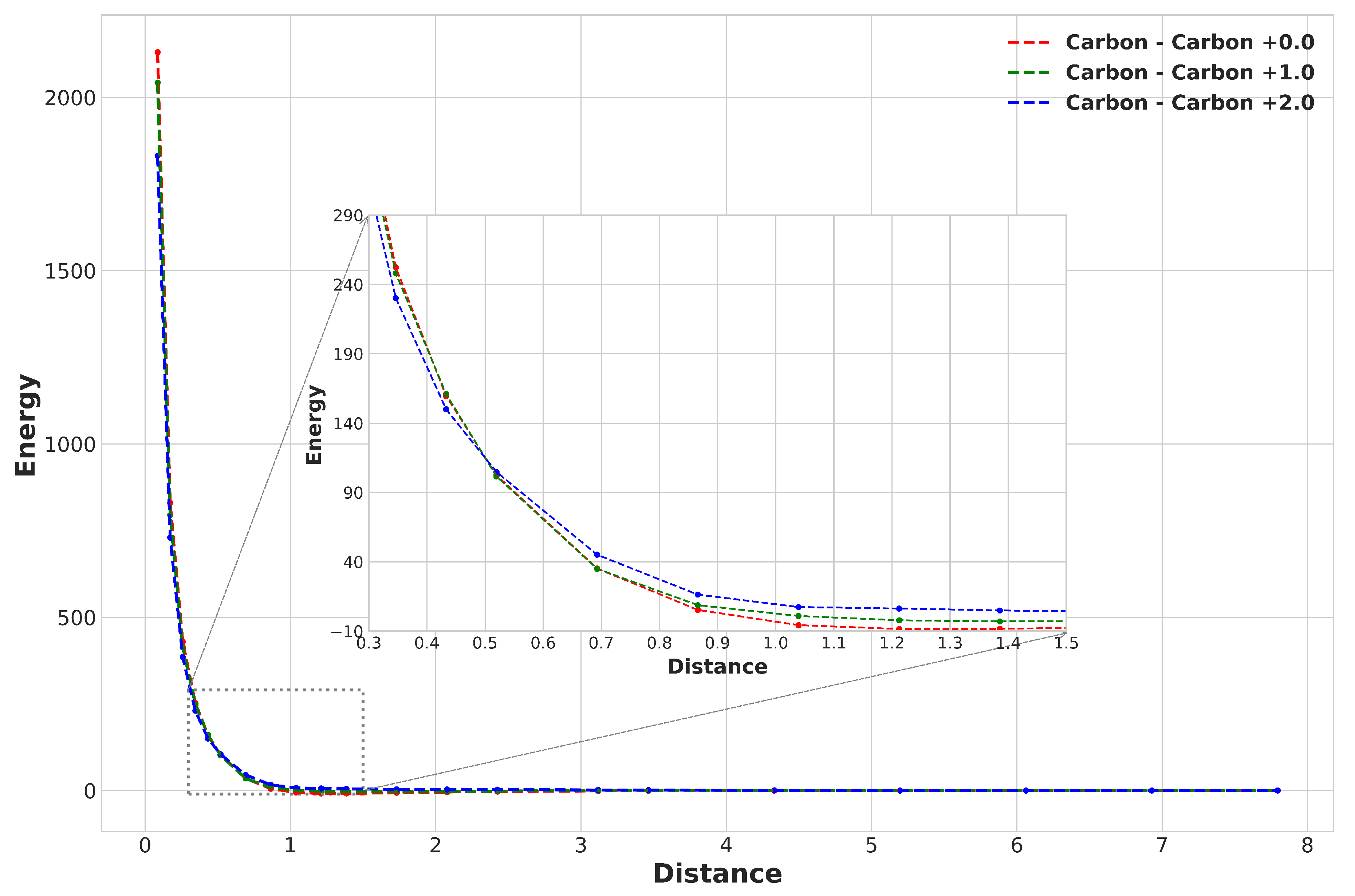

For the system-charge configuration of Carbon–Carbon, for instance, the plot of relative non-bonded energy versus distance is shown in

Figure 1 for various partial charges. In order to learn an interatomic potential for each configuration, the Buckingham Potential was selected as the appropriate choice.

In the above equation, r is the inter-atomic distance for a non-bonded atom-pair. By fitting each configuration’s energy and distance values to the above equation, the constants A, B, and C in the Buckingham potential were obtained using the "Levenberg-Marquardt" algorithm. This algorithm starts with an initial guess for the parameters (A, B and C) of the function, then calculates the gradient of the residuals with respect to the parameters and iterates until the residuals are minimized, or a maximum number of iterations is reached. To optimize the initial starting values for this algorithm, the grid search technique was utilized. As a result, a set of Buckingham constants was obtained for each system-charge configuration.

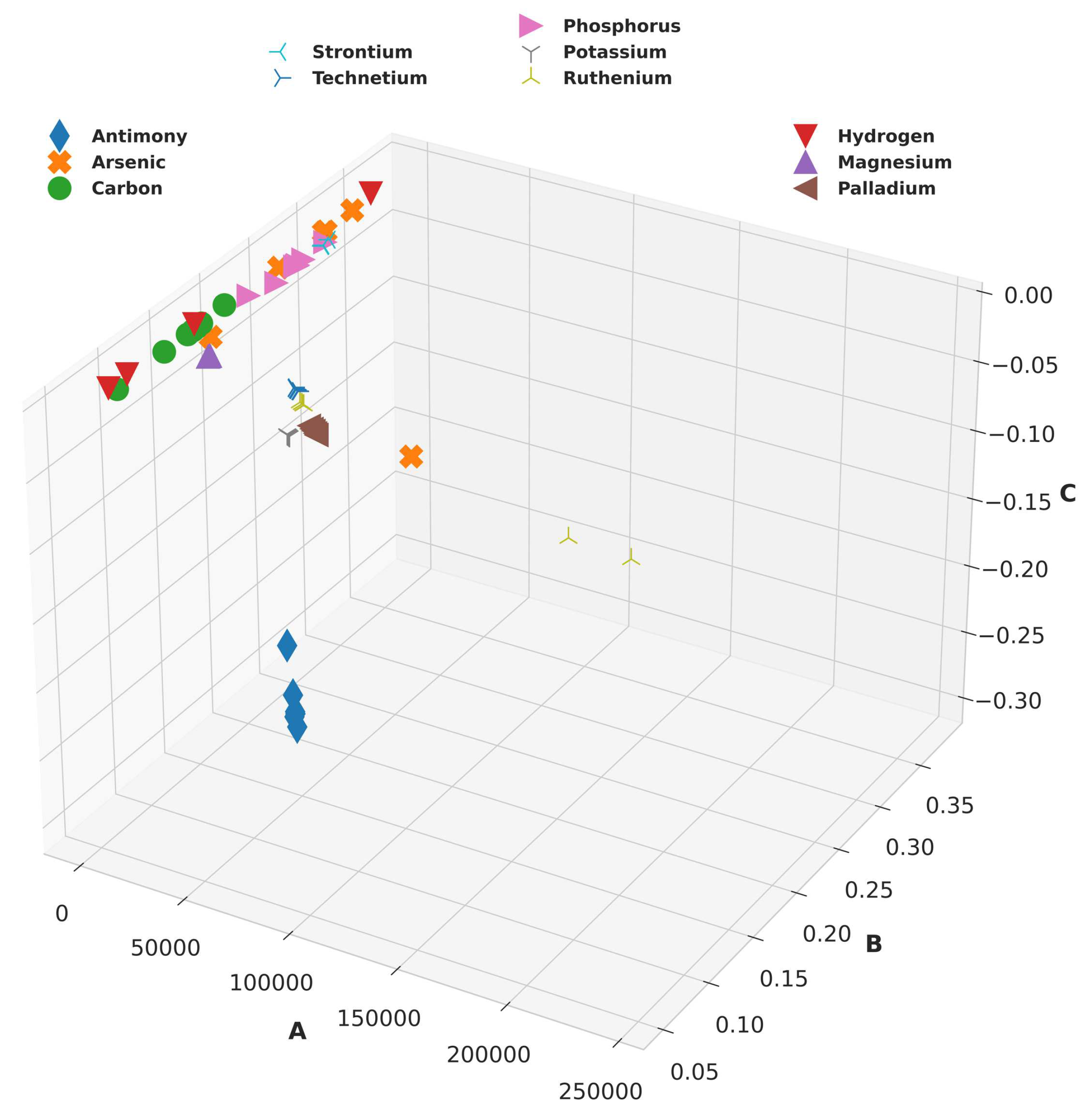

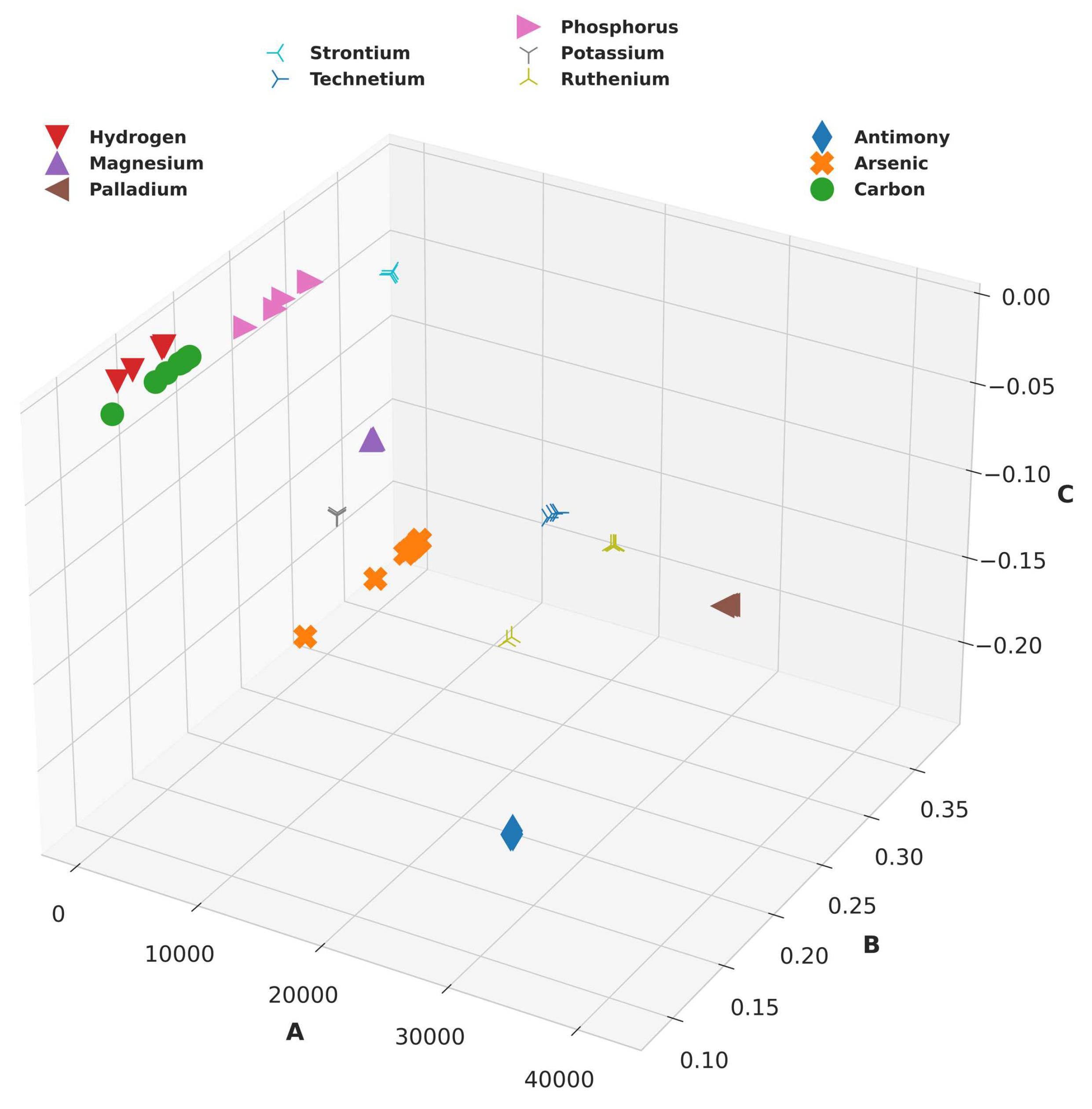

2.2.2. Clustering:

From the Buckingham Potential equation, it is intuitively clear that for a given value of energy and distance, there can be multiple combinations of Buckingham constants. Now, it is prudent to choose a combination that could best enable the learning process of our model. This was done by clustering the system-charge configurations representing the same element. To cluster configurations for the same elements, the configuration with the highest

value was first chosen for each element. All the Buckingham potentials obtained previously were recomputed while providing upper and lower bounds to the algorithm centred around this chosen configuration bearing the highest

. The original computed configurations and the resulting recomputed configurations are shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, respectively.

2.3. AI Model and Training

2.3.1. Fingerprint:

The task of training an AI model for predicting non-bonded interatomic potentials, such as the Buckingham potential, requires a careful selection of both the configuration representation and the algorithm. The goal of this work is to determine a potential that can be used as input for MD simulations, giving researchers the flexibility to adjust additional parameters for their specific applications. To this end, we have chosen the most basic properties of a system-charge configuration as the input for our AI model. These include the atomic mass, atomic radius, atomic number, and partial charge of each atom. The task of selecting the appropriate representation, or "fingerprint," of each configuration is thus simplified, as we are only concerned with modeling the non-bonded interactions between atoms.

2.3.2. Training:

To achieve an optimal model, all labels generated using the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm with an value of less than 90% were eliminated. The remaining dataset was then split into training and test sets, with a ratio of 75% to 25%, respectively, due to the small size of the dataset. Instead of further dividing the training data into a training and validation sets, k-fold cross-validation was used to train and evaluate the model. K-fold cross-validation divides data into k subsets and trains a model k times, each time using a different subset as the test set and the remaining ones as the training set. The performance is then averaged across all iterations to estimate the model’s performance on unseen data. This technique helps utilize all the data, reduces the impact of sampling bias, and reduces the risk of overfitting, especially in small datasets.

2.3.3. Algorithm:

The use of ML was determined to be the most appropriate choice for this dataset as DL models are often prone to overfitting with smaller datasets. After evaluating several ML algorithms, the Random Forest Regressor was selected as the most suitable candidate due to its enhanced accuracy and robustness compared to traditional decision tree algorithms. The Random Forest Regressor operates by combining multiple decision trees, each of which is trained on a different subset of the training data and a randomly selected subset of features. The final prediction is made by averaging the predictions from all decision trees in the forest. The model was optimized for maximum accuracy with the grid search technique, which focused on tuning three hyperparameters: the number of estimators in the forest, the minimum number of samples required to split a node, and the utilization of bootstrap samples for each tree. The trained model was able to predict the Buckingham potential constants for test data with an accuracy of 93%.

2.3.4. MD Simulations:

With a trained model, we can predict Buckingham potential parameters for same element atom-pairs for any given partial charge. We then use the mixing rule to calculate the Buckingham constants for dissimilar atom pairs using the following equations:

where A, B, and C represent the Buckingham potential parameters. Also, m and n represent the index of the atom-type in the system.

The non-bonded potentials obtained can subsequently be used for computational investigations at the atomic-molecular scale. Potential constants for the other types of interactions apart from non-bonded interactions are taken from the work by Lanjan et. al [

14]. In this work, the “LAMMPS” software package [

41] is employed with the settings and potentials described in

Table 2 and

Table 3, respectively.

3. Results and Discussion

To evaluate the effectiveness of our method, we selected four molecules with different levels of complexity: (i) H

2O, a simple molecule (ii) (CH

2O)

2CO Ethylene Carbonate (EC), a relatively complex molecule with a ring section, (iii) C

2H

5OH (ethanol), a short-length hydrocarbon, and (iv) C

8H

18 (octane), a long chain molecule. Firstly, we used the partial charges from the literature [

14] for all possible unique similar atom-pair combinations for each molecule to predict the corresponding Buckingham potential parameters using our trained ML model. We then computed the Buckingham potential parameters for the dissimilar atom-pair combinations using mixing rules outlined in equations 2-4. The accuracy of the predicted potential parameters is provided in

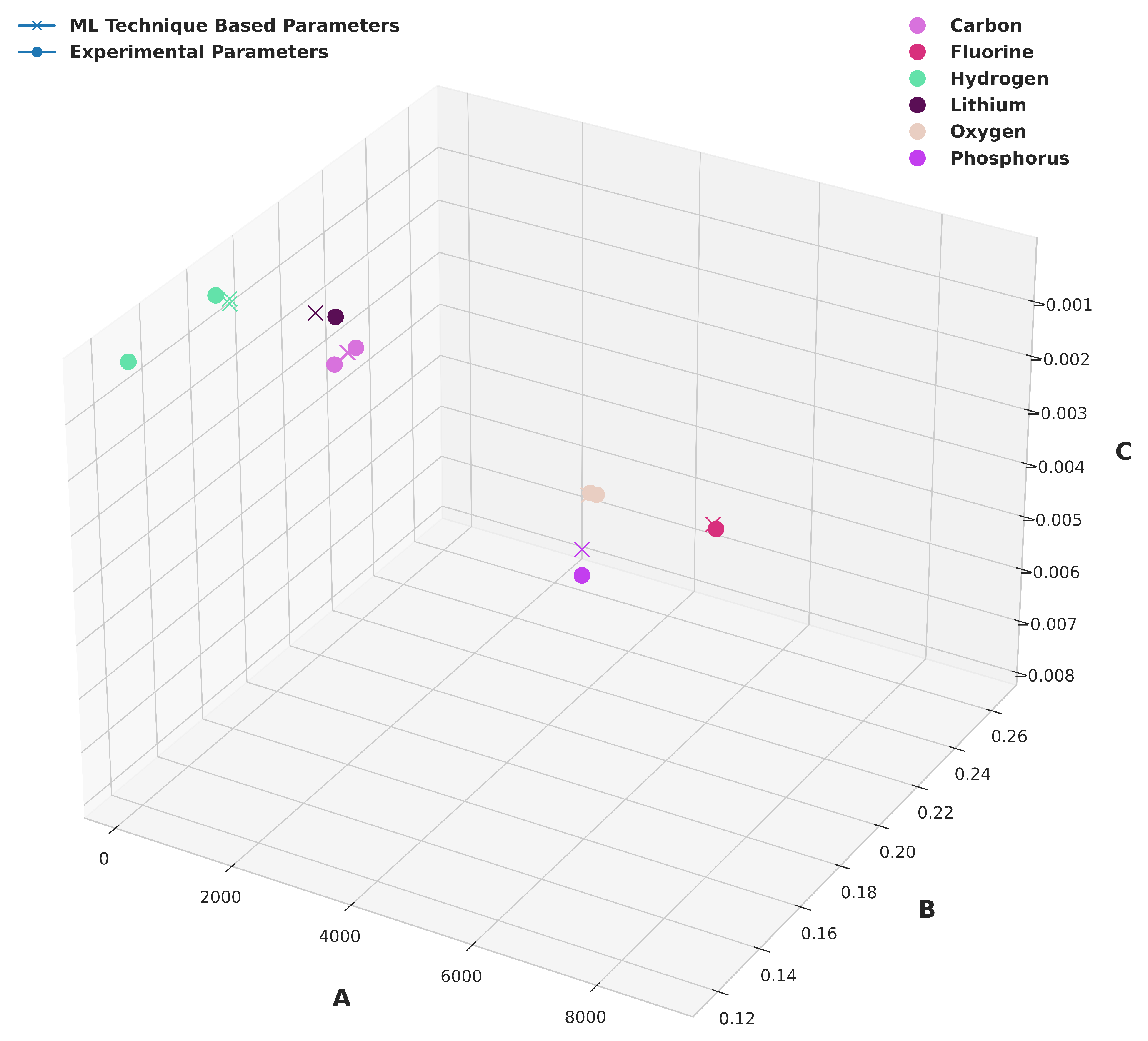

Table 4. The comparison of the predicted values with the experimental values is shown in

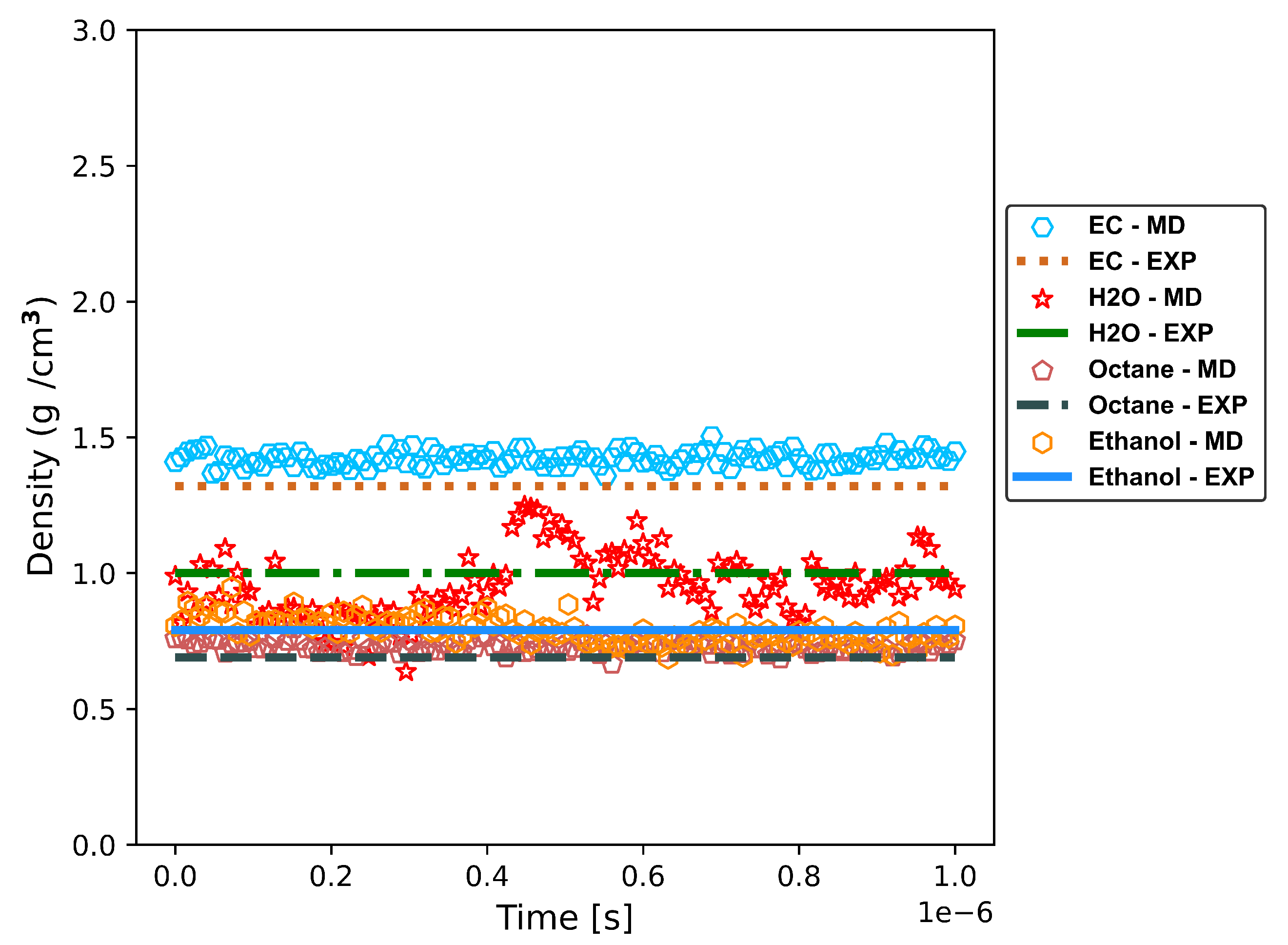

Figure 4. Next, we used these predicted potential parameters as inputs for MD simulations to predict the density of these molecules.

Density is an important property of molecules as it can provide information about their packing and intermolecular forces. An accurate prediction of density requires an accurate modeling of interatomic forces and interactions, including both bonded and non-bonded interactions. Non-bonded interactions are sensitive to temperature and pressure changes and have a significant impact on the density of a molecule. As such, calculating the density precisely is a good indicator that the proposed ML-based technique can be employed to determine other molecular properties such as mechanical properties, thermal properties, and electrochemical properties, that are influenced by similar interatomic interactions. Furthermore, density is a thermodynamic property that can be measured experimentally and accurately calculated using QM techniques. Hence, comparing the predicted densities of materials with the experimental values is an effective approach to assess the accuracy and reliability of our ML-based method. This comparison is summarized in

Table 5, where our predicted densities are shown to have an accuracy greater than 93% with respect to the experimental data. Also, the densities obtained with MD simulations (specifications in Table 2) using our ML-predicted potential parameters are shown as a function of time in

Figure 5. The density results in our MD simulations align closely with the expected values for Ethylene Carbonate (EC) and Octane, with slight deviations well within the permissible range for computational models. The dynamic density fluctuations observed in H

2O and Ethanol simulations are characteristic of the inherent complexities of molecular dynamics. Such variations are anticipated in MD simulations, reflecting the system’s responsiveness to changing conditions and interactions, while the overall trends remain consistent with experimental expectations, demonstrating the reliability of our computational approach.

4. Conclusions

Nano-based computational techniques, such as QM and MD, have been the status-quo for material discovery and material property prediction. However, larger length and time scale analysis, vital for understanding important battery phenomena, is often infeasible with QM simulations due to their computational limitations. On the other hand, MD simulations require potential parameters as inputs, which are often difficult to obtain for new and novel materials. The need for accurate material property prediction is critical for the development of better, more efficient battery technologies. Addressing these limitations, this work presents a novel ML-based technique that can learn inter-atomic potential parameters for various particle-particle interactions with the accuracy of conventional computational techniques like QM. When used as input to MD simulations, these learned potential parameters can predict a diverse range of properties, enabling the rapid screening and comparison of large databases of materials properties for battery applications.

In this study, we demonstrate the efficacy and validity of our proposed technique by learning a non-bonded interatomic potential, the Buckingham potential. We use the non-bonded potential parameters predicted in this work in conjunction with the potential parameters obtained from the literature for other types of interactions to predict the density of four different complex molecules. The obtained values were in close agreement with the experimental values for all four molecules, establishing the accuracy and efficacy of our proposed technique for the nano-scale evaluation of new and novel materials. Our technique can help quickly eliminate materials that are unlikely to meet the desired criteria, narrowing down the list of potential candidates for further evaluation. By identifying the most promising battery compositions and materials for further testing and development, this technique can accelerate the discovery of novel materials and the improvement of existing battery technologies.

In conclusion, the proposed ML-based technique provides a promising path towards discovering and developing novel materials with enhanced properties for applications such as next-generation batteries with superior electrochemical performance. Our technique can accelerate the search for new materials with desirable properties, allowing for the rapid screening and comparison of large databases of materials properties for such applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.L., A.S., A.L. and S.S.; methodology, M.L. and A.S.; software: A.S.; validation: M.L., A.S. and R.M.; formal analysis: M.L., A.S., A.L; investigation: M.L. and A.S.; computational resources: S.S.; data curation: M.L., R.M. and A.S.; writing—original draft preparation: M.L.; writing—review and editing: A.L. and S.S.; supervision: A.L. and S.S.; project administration: S.S.

Funding

This research was funded by NSERC Discovery grants program. The grant number is RGPIN-2022-04988.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank NSERC Canada for funding this research through their Discovery Grants program. The authors would also like to thank the reviewers for their constructive suggestions that helped improve the quality of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MD |

Molecular Dynamics |

| QM |

Quantum Mechanics |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| CCS |

Chemical Compound Space |

| DFT |

Density Functional Theory |

| DL |

Deep Learning |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| LMO |

Lithium Manganese Oxide |

| HOIPs |

Hybrid Organic-Inorganic Perovskites |

| OQMD |

Open Quantum Materials Database |

| ICSD |

Inorganic Crystal Structure Database |

| ANNs |

Artificial Neural Networks |

| SVR |

Support Vector Regression |

| QE |

Quantum Espresso |

| EC |

Ethylene Carbonate |

References

- von Lilienfeld, O.A. First principles view on chemical compound space: Gaining rigorous atomistic control of molecular properties. International Journal of Quantum Chemistry 2013, 113, 1676–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemonick, S. Exploring chemical space: Can AI take us where no human has gone before? Chemical and Engineering News 2020, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi, Z.; Heydarinasab, A.; Shariati, F.P. First-principle study of doping effects (Ti, Cu, and Zn) on electrochemical performance of Li2MnO3 cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries. International Journal of Quantum Chemistry 2021, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, Z.; Lanjan, A.; Srinivasan, S. Multiscale Investigation into the Co-Doping Strategy on the Electrochemical Properties of Li2RuO3 Cathodes for Li-Ion Batteries. ChemElectroChem 2021, 8, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, R.; Lanjan, A.; Srinivasan, S. Co-Doping Strategies to Improve the Electrochemical Properties of LixMn2O4 Cathodes for Li-Ion Batteries. ChemElectroChem 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, Z.; Lanjan, A.; Srinivasan, S. Enhancement of Electrochemical Properties of Lithium Rich Li2RuO3 Cathode Material. Journal of The Electrochemical Society 2020, 167, 110537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanjan, A.; Srinivasan, S. An Enhanced Battery Aging Model Based on a Detailed Diffusing Mechanism in the SEI Layer. ECS Advances 2022, 1, 030504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanjan, A.; Moradi, Z.; Srinivasan, S. Multiscale Investigation of the Diffusion Mechanism within the Solid–Electrolyte Interface Layer: Coupling Quantum Mechanics, Molecular Dynamics, and Macroscale Mathematical Modeling. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2021, 13, 42220–42229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanjan, A.; Choobar, B.G.; Amjad-Iranagh, S. First principle study on the application of crystalline cathodes Li2Mn0.5TM0.5O3 for promoting the performance of lithium-ion batteries. Computational Materials Science 2020, 173, 109417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanjan, A.; Choobar, B.G.; Amjad-Iranagh, S. Promoting lithium-ion battery performance by application of crystalline cathodes LiXMn1-zFezPO4. Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry 2020, 24, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykol, M.; Herring, P.; Anapolsky, A. Machine learning for continuous innovation in battery technologies. Nature Reviews Materials 2020, 5, 725–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.; Narayanan, B.; Cherukara, M.J.; Sen, F.G.; Sasikumar, K.; Gray, S.K.; Chan, M.K.Y.; Sankaranarayanan, S.K.R.S. Machine Learning Classical Interatomic Potentials for Molecular Dynamics from First-Principles Training Data. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2019, 123, 6941–6957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behler, J. Perspective: Machine learning potentials for atomistic simulations. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2016, 145, 170901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanjan, A.; Moradi, Z.; Srinivasan, S. A computational framework for evaluating molecular dynamics potential parameters employing quantum mechanics. Molecular Systems Design & Engineering 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, S.; Tyagi, R.; Talaie, E.; Srinivasan, S. Using neurocomputing techniques to determine microstructural properties in a Li-ion battery. Neural Computing and Applications 2022, 34, 9983–9999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raccuglia, P.; Elbert, K.C.; Adler, P.D.F.; Falk, C.; Wenny, M.B.; Mollo, A.; Zeller, M.; Friedler, S.A.; Schrier, J.; Norquist, A.J. Machine-learning-assisted materials discovery using failed experiments. Nature 2016, 533, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhou, Q.; Ouyang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, J. Accelerated discovery of stable lead-free hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites via machine learning. Nature Communications 2018, 9, 3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meredig, B.; Agrawal, A.; Kirklin, S.; Saal, J.E.; Doak, J.W.; Thompson, A.; Zhang, K.; Choudhary, A.; Wolverton, C. Combinatorial screening for new materials in unconstrained composition space with machine learning. Physical Review B 2014, 89, 094104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, A.; Hellenbrandt, M.; Karen, V.L.; Luksch, P. New developments in the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD): accessibility in support of materials research and design. Acta Crystallographica Section B Structural Science 2002, 58, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirklin, S.; Saal, J.E.; Meredig, B.; Thompson, A.; Doak, J.W.; Aykol, M.; Rühl, S.; Wolverton, C. The Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD): assessing the accuracy of DFT formation energies. npj Computational Materials 2015, 1, 15010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom, C.R.; Bruno, I.J.; Lightfoot, M.P.; Ward, S.C. The Cambridge Structural Database. Acta Crystallographica Section B Structural Science, Crystal Engineering and Materials 2016, 72, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hachmann, J.; Olivares-Amaya, R.; Atahan-Evrenk, S.; Amador-Bedolla, C.; Sánchez-Carrera, R.S.; Gold-Parker, A.; Vogt, L.; Brockway, A.M.; Aspuru-Guzik, A. The Harvard Clean Energy Project: Large-Scale Computational Screening and Design of Organic Photovoltaics on the World Community Grid. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2011, 2, 2241–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Ong, S.P.; Hautier, G.; Chen, W.; Richards, W.D.; Dacek, S.; Cholia, S.; Gunter, D.; Skinner, D.; Ceder, G.; Persson, K.A. Commentary: The Materials Project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Materials 2013, 1, 011002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtarolo, S.; Setyawan, W.; Wang, S.; Xue, J.; Yang, K.; Taylor, R.H.; Nelson, L.J.; Hart, G.L.; Sanvito, S.; Buongiorno-Nardelli, M.; Mingo, N.; Levy, O. AFLOWLIB.ORG: A distributed materials properties repository from high-throughput ab initio calculations. Computational Materials Science 2012, 58, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ling, C. A strategy to apply machine learning to small datasets in materials science. npj Computational Materials 2018, 4, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, L.; Agrawal, A.; Choudhary, A.; Wolverton, C. A general-purpose machine learning framework for predicting properties of inorganic materials. npj Computational Materials 2016, 2, 16028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütt, K.T.; Glawe, H.; Brockherde, F.; Sanna, A.; Müller, K.R.; Gross, E.K.U. How to represent crystal structures for machine learning: Towards fast prediction of electronic properties. Physical Review B 2014, 89, 205118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenberg, P.; Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous Electron Gas. Physical Review 1964, 136, B864–B871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himanen, L.; Jäger, M.O.; Morooka, E.V.; Canova, F.F.; Ranawat, Y.S.; Gao, D.Z.; Rinke, P.; Foster, A.S. DScribe: Library of descriptors for machine learning in materials science. Computer Physics Communications 2020, 247, 106949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Lengeling, B.; Aspuru-Guzik, A. Inverse molecular design using machine learning: Generative models for matter engineering. Science 2018, 361, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, M.; Tkatchenko, A.; Müller, K.R.; von Lilienfeld, O.A. Fast and Accurate Modeling of Molecular Atomization Energies with Machine Learning. Physical Review Letters 2012, 108, 058301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, K.; Biegler, F.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Pronobis, W.; von Lilienfeld, O.A.; Müller, K.R.; Tkatchenko, A. Machine Learning Predictions of Molecular Properties: Accurate Many-Body Potentials and Nonlocality in Chemical Space. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 2015, 6, 2326–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbarpour, H.; Mohajeri, M.; Moradi, M. Investigation on the synthesis conditions at the interpore distance of nanoporous anodic aluminum oxide: A comparison of experimental study, artificial neural network, and multiple linear regression. Computational Materials Science 2013, 79, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, J.M.; Baumes, L.A.; Moliner, M.; Serna, P.; Corma, A. Zeolite Synthesis Modelling with Support Vector Machines: A Combinatorial Approach. Combinatorial Chemistry & High Throughput Screening 2007, 10, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, S.; Wang, M.; Qi, W.; Zheng, F. Hybrid genetic algorithms and support vector regression in forecasting atmospheric corrosion of metallic materials. Computational Materials Science 2008, 44, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The classical equation of state of gaseous helium, neon and argon. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences 1938, 168, 264–283. [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Chu, X.; Sun, X.; Xu, K.; Deng, H.; Chen, J.; Wei, Z.; Lei, M. Machine learning in materials science. InfoMat 2019, 1, 338–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannozzi, P.; Baroni, S.; Bonini, N.; Calandra, M.; Car, R.; Cavazzoni, C.; Ceresoli, D.; Chiarotti, G.L.; Cococcioni, M.; Dabo, I.; Corso, A.D.; de Gironcoli, S.; Fabris, S.; Fratesi, G.; Gebauer, R.; Gerstmann, U.; Gougoussis, C.; Kokalj, A.; Lazzeri, M.; Martin-Samos, L.; Marzari, N.; Mauri, F.; Mazzarello, R.; Paolini, S.; Pasquarello, A.; Paulatto, L.; Sbraccia, C.; Scandolo, S.; Sclauzero, G.; Seitsonen, A.P.; Smogunov, A.; Umari, P.; Wentzcovitch, R.M. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2009, 21, 395502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannozzi, P.; Andreussi, O.; Brumme, T.; Bunau, O.; Nardelli, M.B.; Calandra, M.; Car, R.; Cavazzoni, C.; Ceresoli, D.; Cococcioni, M.; Colonna, N.; Carnimeo, I.; Corso, A.D.; de Gironcoli, S.; Delugas, P.; DiStasio, R.A.; Ferretti, A.; Floris, A.; Fratesi, G.; Fugallo, G.; Gebauer, R.; Gerstmann, U.; Giustino, F.; Gorni, T.; Jia, J.; Kawamura, M.; Ko, H.Y.; Kokalj, A.; Küçükbenli, E.; Lazzeri, M.; Marsili, M.; Marzari, N.; Mauri, F.; Nguyen, N.L.; Nguyen, H.V.; de-la Roza, A.O.; Paulatto, L.; Poncé, S.; Rocca, D.; Sabatini, R.; Santra, B.; Schlipf, M.; Seitsonen, A.P.; Smogunov, A.; Timrov, I.; Thonhauser, T.; Umari, P.; Vast, N.; Wu, X.; Baroni, S. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with Quantum ESPRESSO. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2017, 29, 465901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannozzi, P.; Baseggio, O.; Bonfà, P.; Brunato, D.; Car, R.; Carnimeo, I.; Cavazzoni, C.; de Gironcoli, S.; Delugas, P.; Ruffino, F.F.; Ferretti, A.; Marzari, N.; Timrov, I.; Urru, A.; Baroni, S. Quantum ESPRESSO toward the exascale. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2020, 152, 154105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.P.; Aktulga, H.M.; Berger, R.; Bolintineanu, D.S.; Brown, W.M.; Crozier, P.S.; in ’t Veld, P.J.; Kohlmeyer, A.; Moore, S.G.; Nguyen, T.D.; Shan, R.; Stevens, M.J.; Tranchida, J.; Trott, C.; Plimpton, S.J. LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Computer Physics Communications 2022, 271, 108171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).