Submitted:

23 November 2023

Posted:

24 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

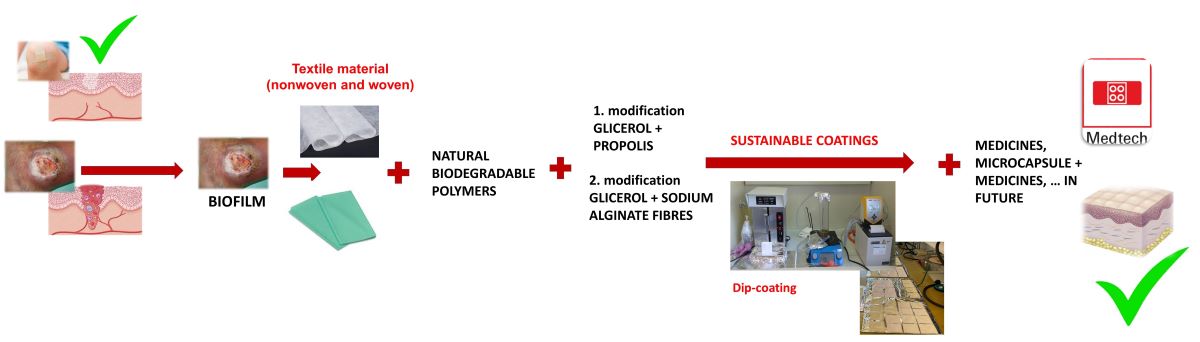

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Materials

2.1.1. Preparation of the Textile Materials

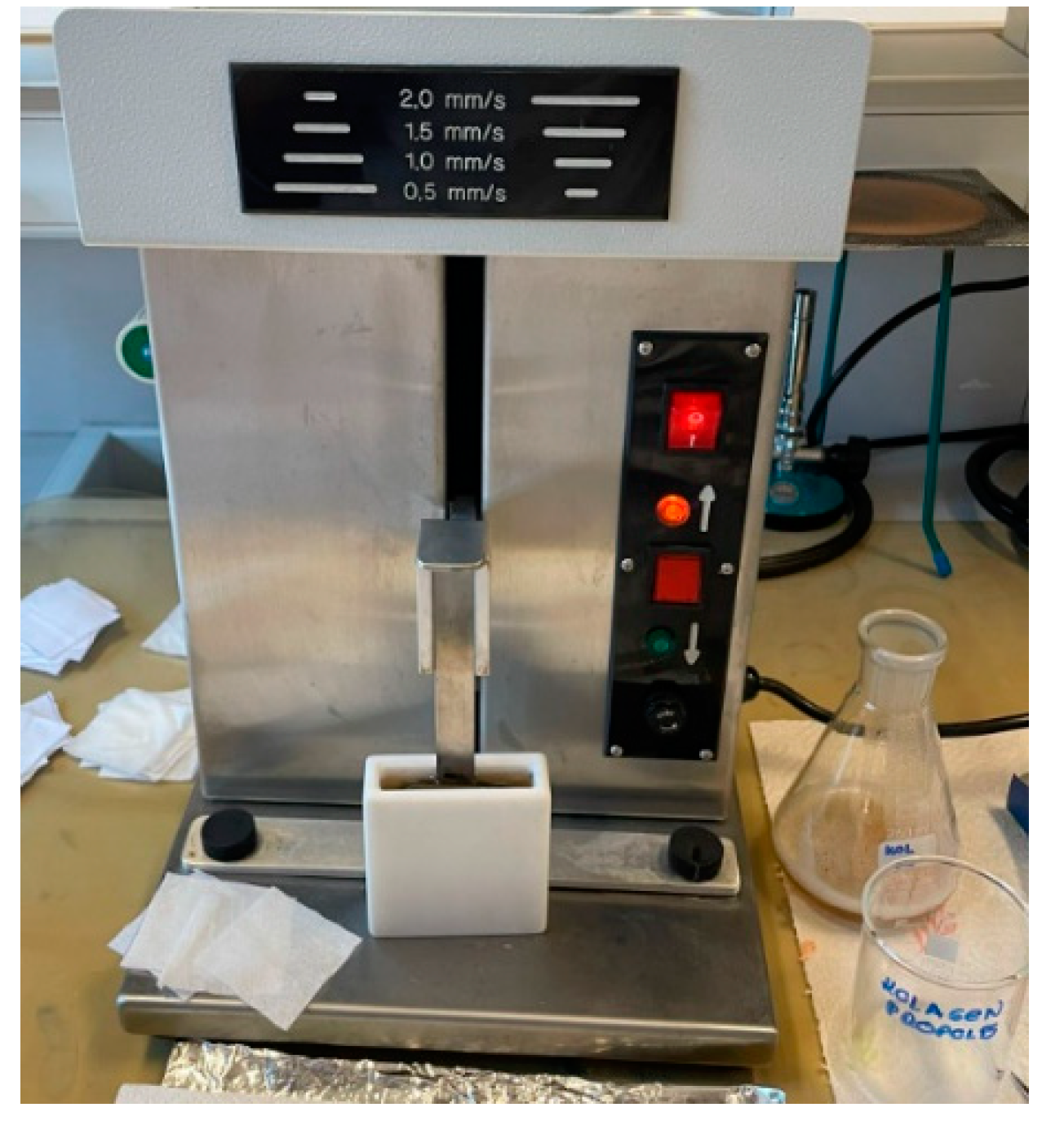

2.1.2. Preparation of Sustainable Coatings

2.2. Determination of the Morphology of the Materials

2.3. Activity of Hydrogen Ions

2.4. Drop Test Method

2.5. Determination of the Crease Recovery Angle

3. Results and Discussion

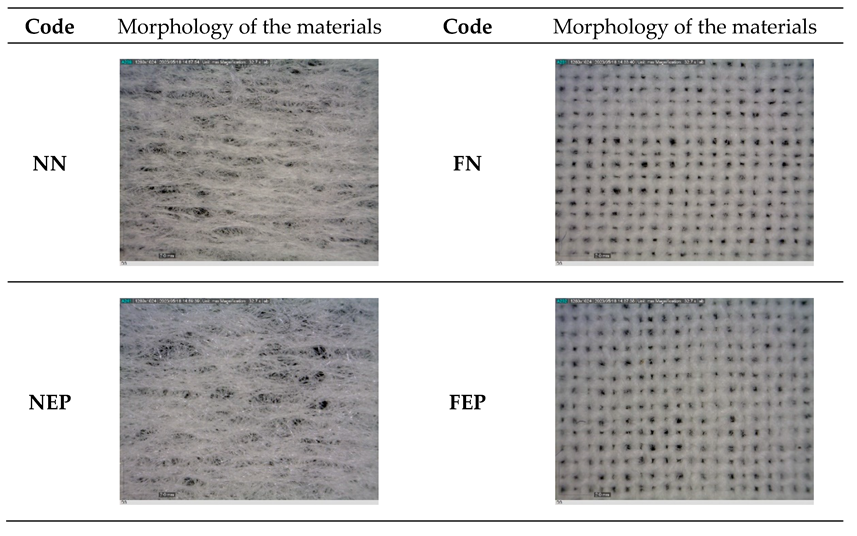

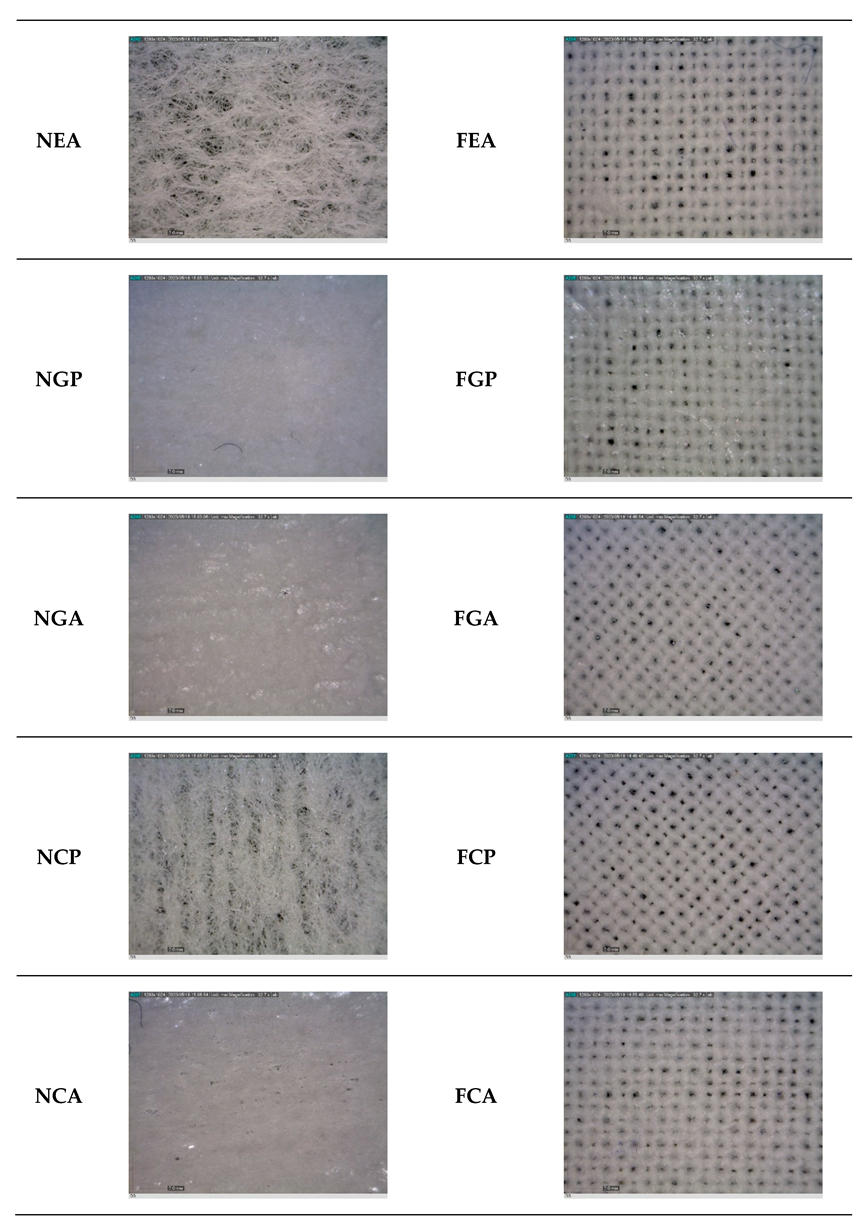

3.1. Results of the Morphology of the Materials

3.2. Results of the Activity of Hydrogen Ions

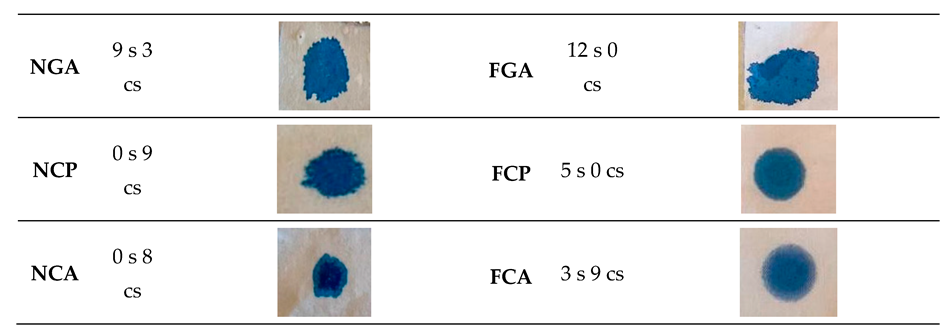

3.3. Results of the Drop Test Method

3.4. Results of the Crease Recovery Angle

3.5. Results of the Ddetermination of Thickness and Mass per Unit Area

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Namazi, H. Polymers in our daily life. Bioimpacts. 2017, 7, 73–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolie, O.; Kumar, A.; Edwards, C.; Lawton, L.A.; Oke, A.; McDonald, S.; Thakur, V.K.; Njuguna, J. Bio-Based Sustainable Polymers and Materials: From Processing to Biodegradation. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samir, A.; Ashour, F.H.; Hakim, A.A.A. Recent advances in biodegradable polymers for sustainable applications. npj Mater Degrad 2022, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, K.Y.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Jaiswal, S. Biopolymer-Based Sustainable Food Packaging Materials: Challenges, Solutions, and Applications. Foods 2023, 12, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunšek, R.; Kopitar, D.; Schwarz, I.; Marasović, P. Biodegradation Properties of Cellulose Fibers and PLA Biopolymer. Polymers 2023, 15, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Hong, P.Z.; Liao, M.N.; Kong, S.Z.; Huang, N.; Ou, C.Y.; Li, S.D. Preparation and Characterization of Chitosan-Agarose Composite Films. Materials 2016, 9, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabra, M.J.; Falco, I.; Randazzo, W.; Sanchez, G.; Lopez – Rubio, A. Antiviral and antioxidant properties of active alginate edible films containing phenolic extracts. Food Hydrocolloid. 2018, 81, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khezrian A i Shahbazi, Y. Application of nanocompostie chitosan and carboxymethyl cellulose films containing natural preservative compounds in minced camel’s meat. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 106, 1146–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, J.; Zhou, L.; Tang, Y.J.; Luo, Y.; Duan, T.; Zhu, W.K. High - strength konjac glucomannan/silver nanowires composite films with antibacterial properties. Materials 2017, 10, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, G.; Guzman-Puyol, S.; Ceseracciu, L.; Paul, U.C.; Picone, P.; Di Carlo, M.; Athanassiou, A.; Heredia-Guerrero, J.A. multifunctional bioplastics inspired by wood composition: effect of hydrolyzed lignin addition to xylan - cellulose matrices. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 910–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M.; Khadem, S.; Cakmak, Y.S.; Mujtaba, M.; Ilk, S.; Akyuz, L.; Salaberria, A.M.; Labidi, J.; Abdulqadir, A.H.; Deligoz, E. Antioxidative and antimicrobial edible chitosan films blended with stem, leaf and seed extracts of Pistacia terebinthus for active food packaging. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 3941–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.B.; Yi, J.J.; Yu, X.M.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wang, L. Preparation and characterization of pullulan derivative/chitosan composite film for potential antimicrobial applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 148, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdollahzadeh, E.; Ojagh, S.M.; Fooladi, A.A.I.; Shabanpour, B.; Gharahei, M. Effects of probiotic cells on the mechanical and antibacterial properties of sodium-caseinate films. App. Food Biotechnol. 2018, 5, 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, M.; Nirmal, N.P.; Danish, M.; Chuprom, J.; Jafarzedeh, S. Characterisation of composite films fabricated from collagen/chitosan and collagen/soy protein isolate for food packaging applications. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 82191–82204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.G.G.; i Almasi, H. physical characteristics, release properties, and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of whey protein isolate films incorporated with thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) extract - loaded nanoliposomes. Food Bioprocess Tech. 2018, 11, 1552–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverria, I.; Lopez – Caballero, M.E.; Gomez – Guillen, M.C.; Mauri, A.N.; Montero, M.P. Active nanocomposite films based on soy proteins – montmorillonite - clove essential oil for the preservation of refrigerated bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) fillets. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 266, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, F.T.; da Cunha, K.F.; Fonseca, L.M.; Antunes, M.D.; El Halal, S.L.M.; Fiorentini, A.M.; Zavareze, E.D.; Dias, A.R.G. Action of ginger essential oil (Zingiber officinale) encapsulated in proteins ultrafine fibers on the antimicrobial control in situ. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 118, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Lopez, K.J.; Castro-Mayorga, J.L.; Andrade-Mahecha, M.M.; Cabedo, L.; Lagaron, J.M. antibacterial and barrier properties of gelatin coated by electrospun polycaprolactone ultrathin fibers containing black pepper oleoresin of interest in active food biopackaging applications. Nanomaterials - Basel 2018, 8, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akyuz, L.; Kaya, M.; Ilk, S.; Cakmak, Y.S.; Salaberria, A.M.; Labidi, J.; Yilmaz, B.A.; Sargin, I. Effect of different animal fat and plant oil additives on physicochemical, mechanical, antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of chitosan films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 111, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saurabh, C.K.; Gupta, S.; Variyar, P.S. Development of guar gum based active packaging films using grape pomace. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2018, 55, 1982–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, K.; Basheer Ahamed, M.; Deshmukh, R.R.; Khadheer Pasha, S.K.; Bhagat, P.R.; Chidambaram, K. 3 - Biopolymer Composites With High Dielectric Performance: Interface Engineering. Biopolymer Composites in Electronics, 1st ed.; Sadasivuni, K.K.; Ponnamma, D.; Kim, J.; Cabibihan, J.-J.; AlMaadeed, M.A.; Elsevier, 2017, pp 27-128.

- Suen, D.W.-S.; Chan, E.M.-H.; Lau, Y.-Y.; Lee, R.H.-P.; Tsang, P.W.-K.; Ouyang, S.; Tsang, C.-W. Sustainable Textile Raw Materials: Review on Bioprocessing of Textile Waste via Electrospinning. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somogyi Škoc, M.; Macan, J.; Emira, P. Modification of polyurethane-coated fabrics by sol–gel thin films. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 131, 39914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuutila, K.; Eriksson, E. Moist Wound Healing with Commonly Available Dressings. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2021, 10, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H. A Review of the Effects of Collagen Treatment in Clinical Studies. Polymers 2021, 13, 3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.K.; Liu, D.; Sun, L.L.; Li, B.F.; Hou, H. Physicochemical and Biocompatibility Properties of Type I Collagen from the Skin of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) for Biomedical Applications. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frent, O.D.; Vicas, L.G.; Duteanu, N.; Morgovan, C.M.; Jurca, T.; Jurca, T.; Muresan, M.E.; Filip, S.M.; Lucaciu, R.L.; Marian, E. Sodium Alginate-Natural Microencapsulation Material of Polymeric Microparticles. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 12108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greatrex-White, S.; Moxey, H. Wound assessment tools and nurses' needs: an evaluation study. Int Wound J. 2015, 12, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuermer, E.K. Wound biofilm: a bacterial success story. Journal of Wound Management 2023, 24(2), 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, J.G.; Zamierowski, D.S.; Robinson, J.L. Evaluating polymeric biomaterials to improve next generation wound dressing design. Biomater Res 2022, 26, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canchy, L.; Kserob, D.; Demessant A.; Amici, J-M. Wound healing and microbiome, an unexpected relationship. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023, 37(Suppl. 3), 7–15.

| Source of Biopolymer | Biopolymer |

|---|---|

| polysaccharides | agarose [6] |

| alginates [7] | |

| cellulose [8] | |

| glucomannan [9] | |

| hemicellulose [10] | |

| chitosan [11] | |

| starch [12] | |

| proteins | casein [13] |

| collagen [14] | |

| whey proteins [15] | |

| soya proteins [16] | |

| zein [17] | |

| gelatin [18] | |

| lipids and waxes | vegetable oil and animal fats [19] |

| waxes [20] |

| Polymer | Erythritol C4H10O4 |

Gelatin C6H12O6 | Collagen C57H91N19O16 | Glycerol C3H8O3 |

Propolis C17H16O4 |

Sodium Alginate Fibres |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molar mass[g mol-1] | 122,12 | 45,00 | 1302,5 | 92,09 | 281,31 | / |

| CAS number | 149-32-6 | 9000-70-8 | 9000-70-8 | 56-81-5 | / | / |

| Note | from corn | 100 % beef gelatin | fish collagen | / | propolis extract in aqueous solution with niacin and sage | sodium alginate fibres with sodium and calcium carbonate |

|

Erythritol (1 g) + distilled water mixing on a magnetic stirrer with a triangular magnet |

Gelatin (5 g) + distilled water mixing on a magnetic stirrer with a triangular magnet |

Collagen (5 g) + distilled water mixing on a magnetic stirrer with a triangular magnet |

|||

| ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ |

| + propolis 10 ml |

+ alginate 10 ml |

+ propolis 10 ml |

+ alginate 10 ml |

+ propolis 10 ml |

+ alginate 10 ml |

| + glycerol 5 ml | + glycerol 5 ml | + glycerol 5 ml | + glycerol 5 ml | + glycerol 5 ml | + glycerol 5 ml |

|

20 ± 2 °C 15 min | |||||

| ↓ The samples were kept at room temperature for 24 h ↓ The samples were fixed at 40 °C for 60 min ↓ Materials morphology with Dino-lite pH of the Water-Extract from Wet Processed Textiles Drop test method Determination of recovery by measuring the recovery angle Determination of thickness and mass per unit area, before and after treatment | |||||

| Code | Biopolymer | Active Compound | Note | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonwoven fabric | NN | / | / | untreated |

| NEP | Erythritol | propolis | ||

| NEA | sodium alginate | |||

| NGP | Gelatin | propolis | ||

| NGA | sodium alginate | |||

| NCP | Collagen | propolis | ||

| NCA | sodium alginate | |||

| Cotton fabric | FN | / | / | untreated |

| FEP | Erythritol | propolis | ||

| FEA | sodium alginate | |||

| FGP | Gelatin | propolis | ||

| FGA | sodium alginate | |||

| FCP | Collagen | propolis | ||

| FCA | sodium alginate | |||

|

| Code | pH | Code | pH |

|---|---|---|---|

| NN | 7 | FN | 7 |

| NEP | 7 | FEP | 7 |

| NEA | 8 | FEA | 7 |

| NGP | 7 | FGP | 7 |

| NGA | 8 | FGA | 7 |

| NCP | 7 | FCP | 7 |

| NCA | 8 | FCA | 7 |

|

| The Angle of Recovery | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code / Direction of Production | Machine Direction ( °) | Cross Machine Direction ( °) | ||||||

| 1. | 2. | 3. | X (°) | 1. | 2. | 3. | X (°) | |

| NN | 101 | 94 | 98 | 97,7 | 107 | 96 | 93 | 98,7 |

| NEP | 93 | 98 | 94 | 95 | 91 | 94 | 97 | 94 |

| NEA | 65 | 74 | 79 | 72,7 | 87 | 84 | 91 | 87,4 |

| NGP | 92 | 96 | 98 | 95,4 | 94 | 98 | 101 | 97,7 |

| NGA | 91 | 89 | 94 | 91,4 | 93 | 98 | 90 | 93,7 |

| NCP | 94 | 89 | 90 | 91 | 98 | 102 | 107 | 102,4 |

| NCA | 93 | 103 | 98 | 98 | 110 | 114 | 105 | 109,7 |

| The Angle of Recovery | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code / Direction of Production | Warp ( °) | Weft ( °) | ||||||

| 1. | 2. | 3. | X (°) | 1. | 2. | 3. | X (°) | |

| FN | 79 | 90 | 71 | 80 | 86 | 77 | 90 | 84,4 |

| FEP | 59 | 69 | 69 | 65,6 | 82 | 84 | 90 | 85,4 |

| FEA | 55 | 59 | 53 | 55,6 | 63 | 61 | 62 | 62 |

| FGP | 69 | 64 | 67 | 66,7 | 73 | 75 | 76 | 74,7 |

| FGA | 51 | 56 | 60 | 55,7 | 74 | 71 | 69 | 71,4 |

| FCP | 75 | 71 | 73 | 73 | 69 | 86 | 84 | 79,7 |

| FCA | 63 | 62 | 69 | 64,7 | 74 | 72 | 76 | 74 |

| Code /n | 1 | 2 | 3 | x | σ | V [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NN | 0,34 | 0,34 | 0,34 | 0,34 | 0 | 0 |

| NEP | 0,34 | 0,34 | 0,34 | 0,34 | 0 | 0 |

| NEA | 0,34 | 0,34 | 0,34 | 0,34 | 0 | 0 |

| NGP | 0,22 | 0,25 | 0,22 | 0,23 | 0,0141 | 6,13 |

| NGA | 0,34 | 0,24 | 0,20 | 0,26 | 0,0589 | 22,65 |

| NCP | 0,29 | 0,24 | 0,30 | 0,27 | 0,0262 | 9,70 |

| NCA | 0,31 | 0,29 | 0,30 | 0,30 | 0,0082 | 2,74 |

| Code / n | 1 | 2 | 3 | x | σ | V [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FN | 0,33 | 0,33 | 0,33 | 0,33 | 0 | 0 |

| FEP | 0,33 | 0,32 | 0,31 | 0,32 | 0,0082 | 2,56 |

| FEA | 0,34 | 0,34 | 0,33 | 0,34 | 0,0047 | 1,38 |

| FGP | 0,33 | 0,32 | 0,32 | 0,32 | 0,0047 | 1,47 |

| FGA | 0,31 | 0,31 | 0,32 | 0,32 | 0,0047 | 1,47 |

| FCP | 0,32 | 0,32 | 0,32 | 0,32 | 0 | 0 |

| FCA | 0,33 | 0,33 | 0,34 | 0,33 | 0,0047 | 1,43 |

| Code | Mass per Unit Area (g m-2 ) | Code | Mass per Unit Area (g m-2 ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FN | 39,15 | NN | 11,7 |

| FEP | 45,96 | NEP | 18,27 |

| FEA | 44,96 | NEA | 15,64 |

| FGP | 47,87 | NGP | 20,66 |

| FGA | 47,21 | NGA | 26,37 |

| FCP | 45,22 | NCP | 21,08 |

| FCA | 46,73 | NCA | 24,16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).