Submitted:

23 November 2023

Posted:

24 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Preparation

2.2. Electrode Preparation

2.3. Electrochemical Measurements

2.4. Additional Material Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

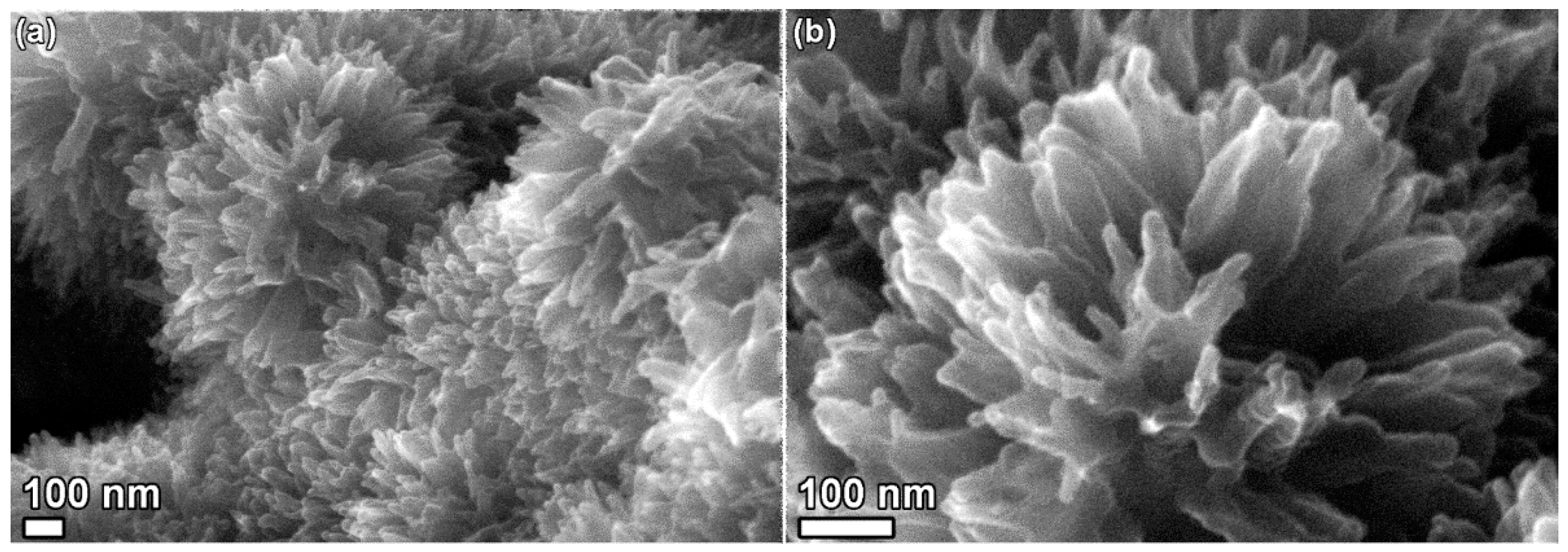

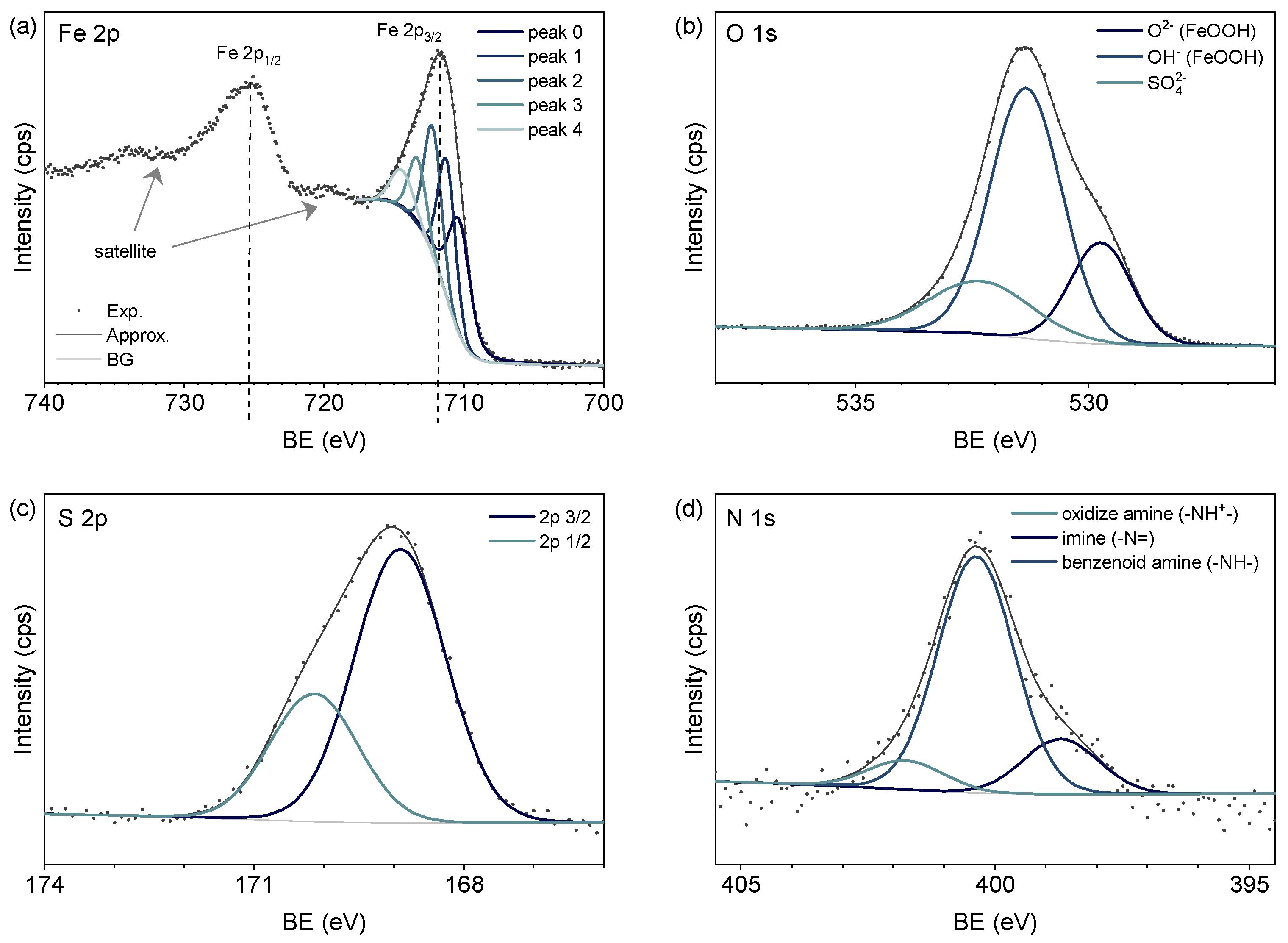

3.1. Characterization of FeOOH/PANI

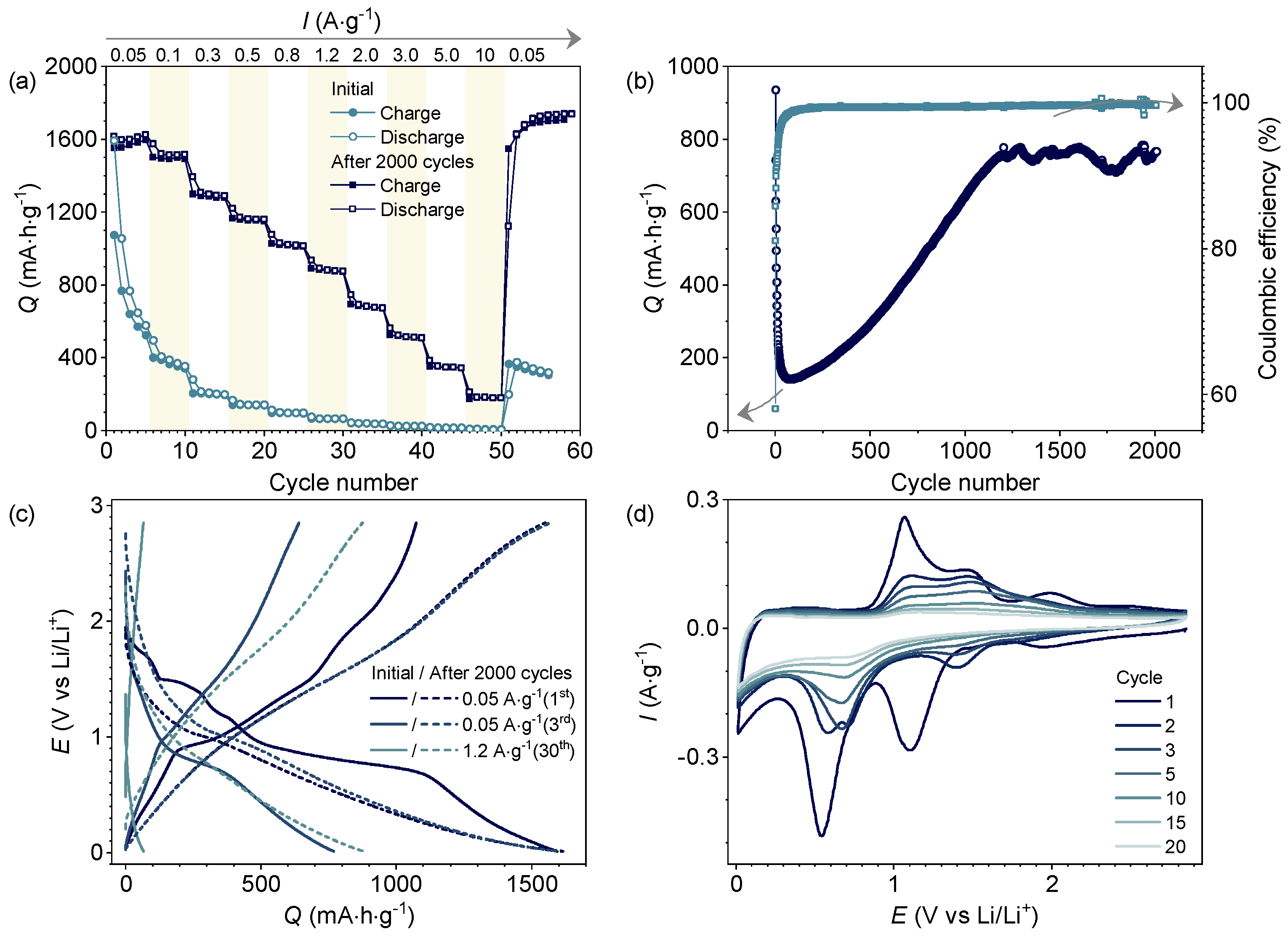

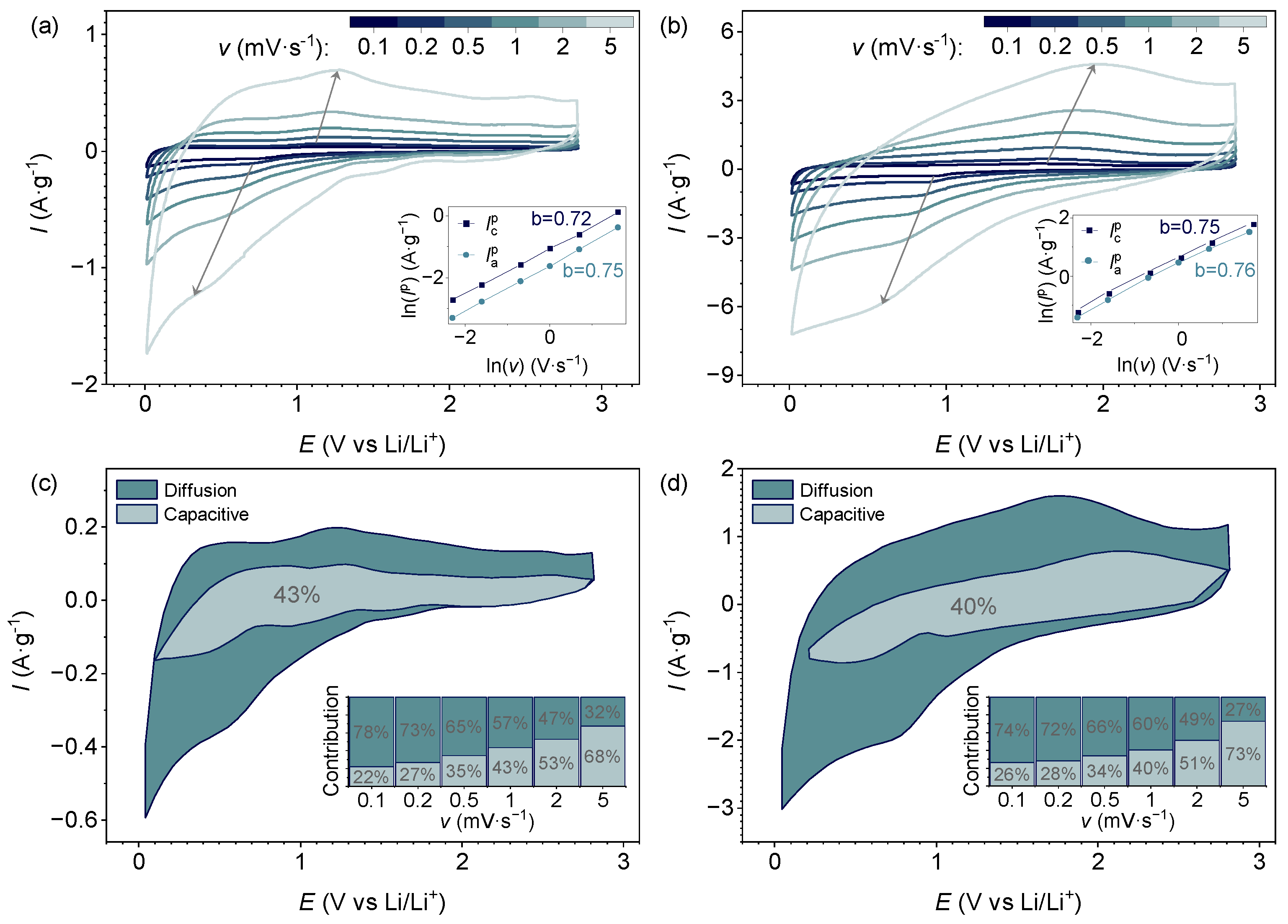

3.2. Electrochemical Performance

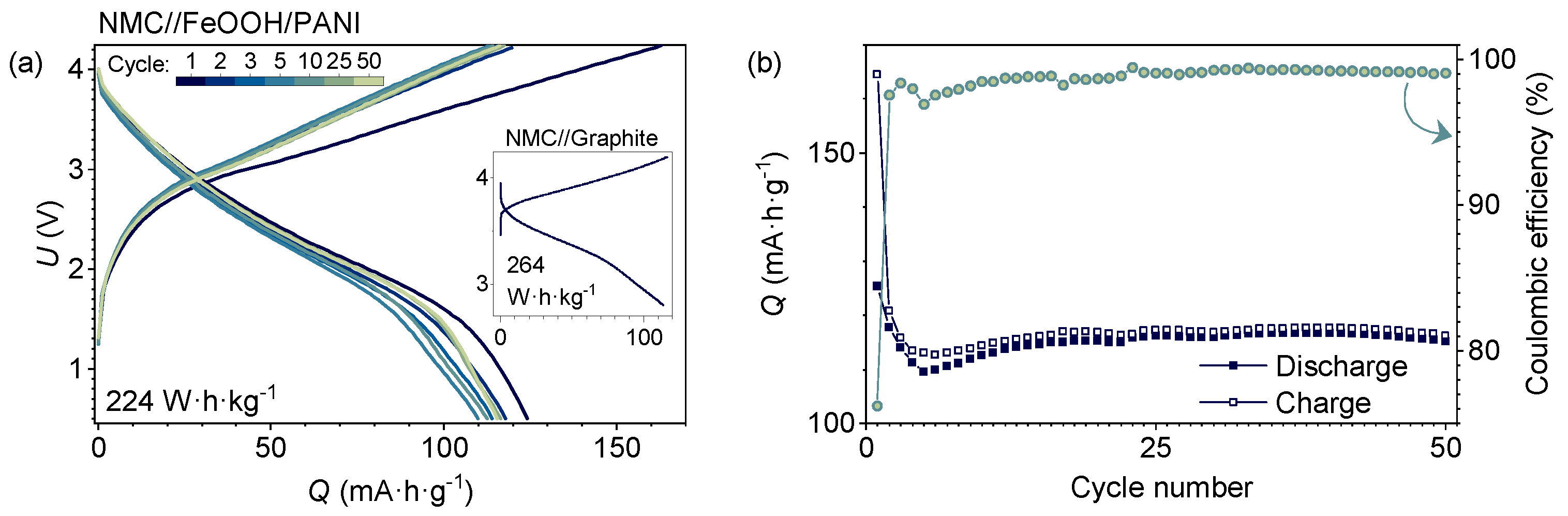

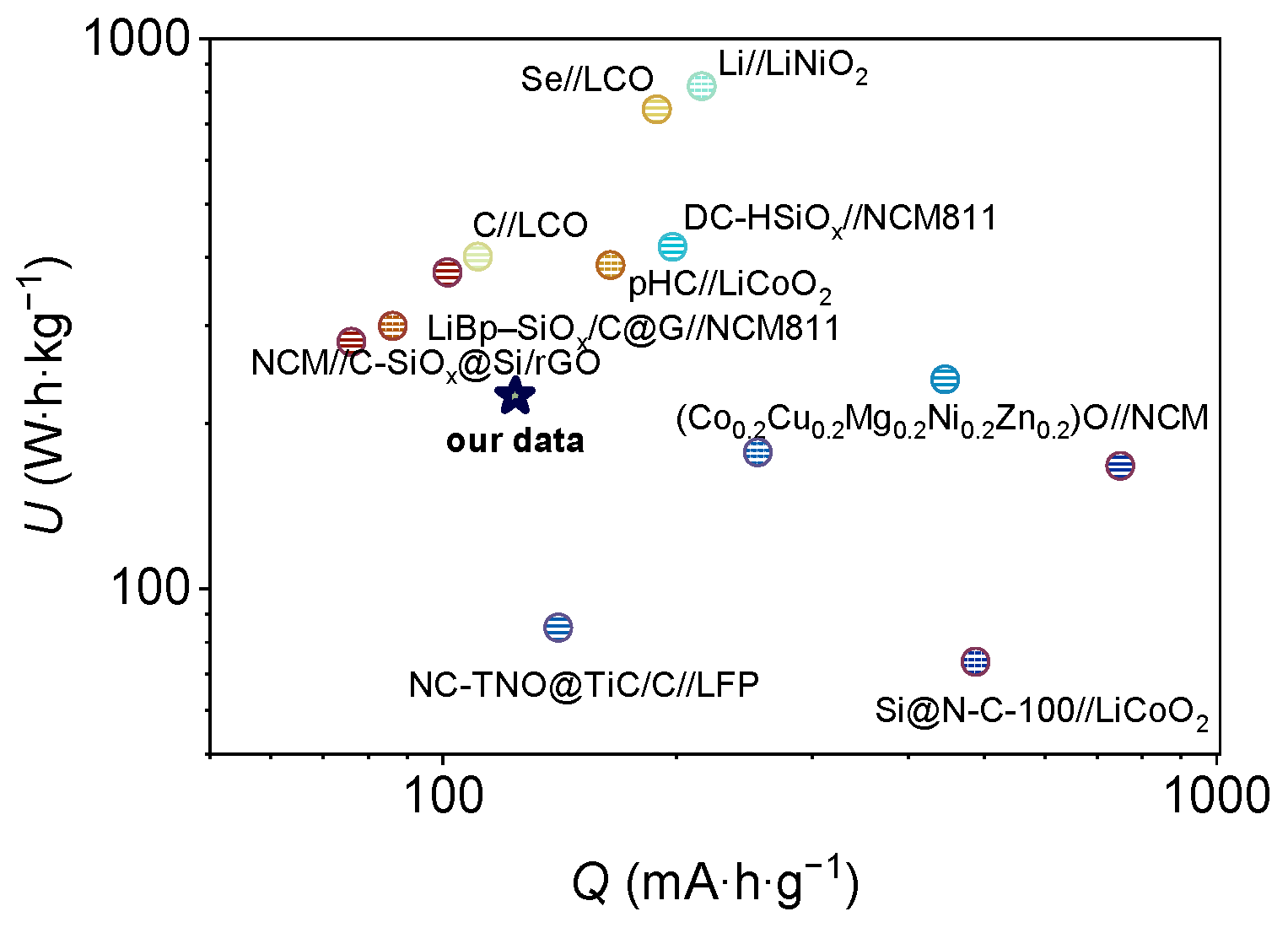

3.3. Full battery

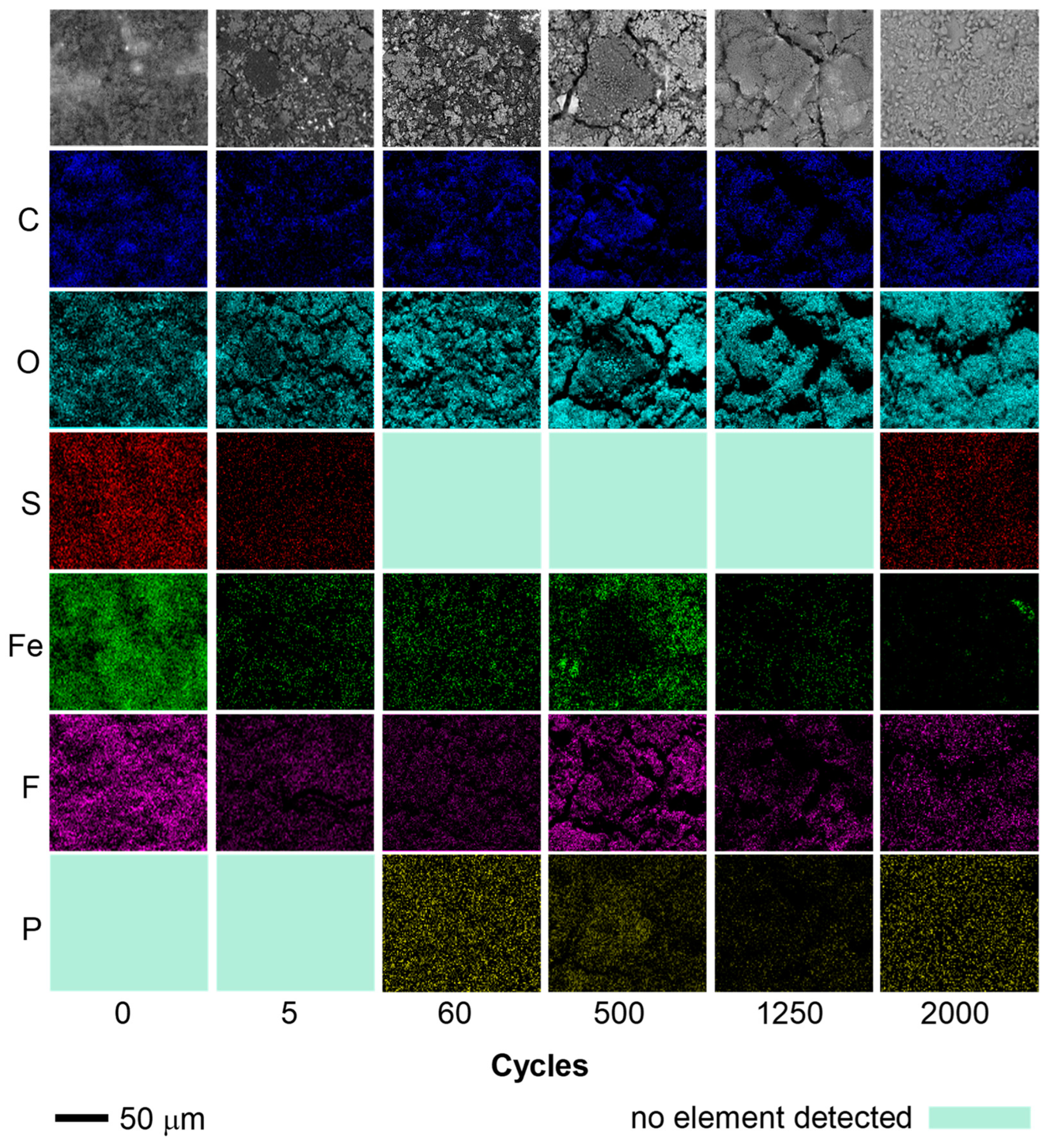

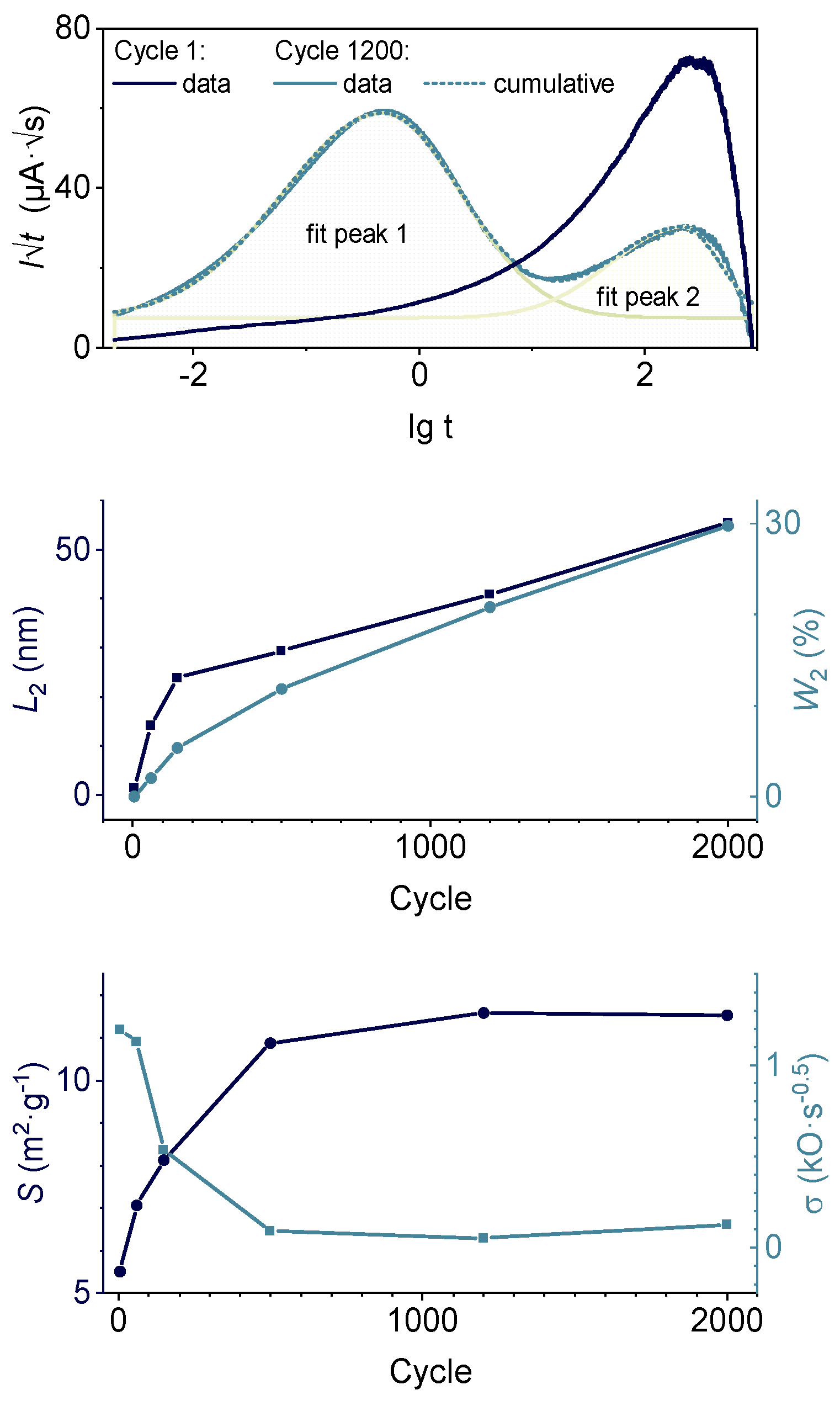

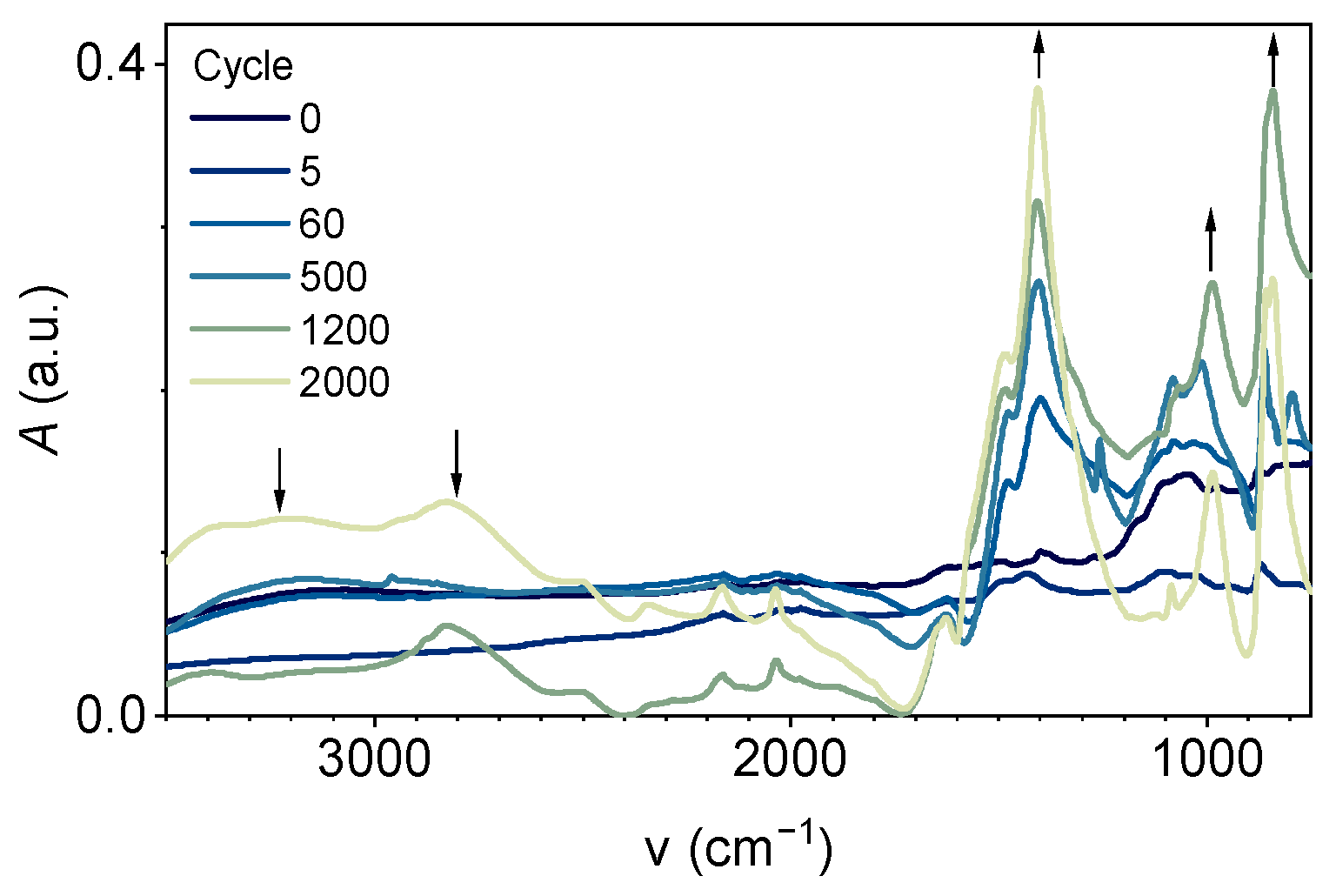

3.4. Post cycled electrodes

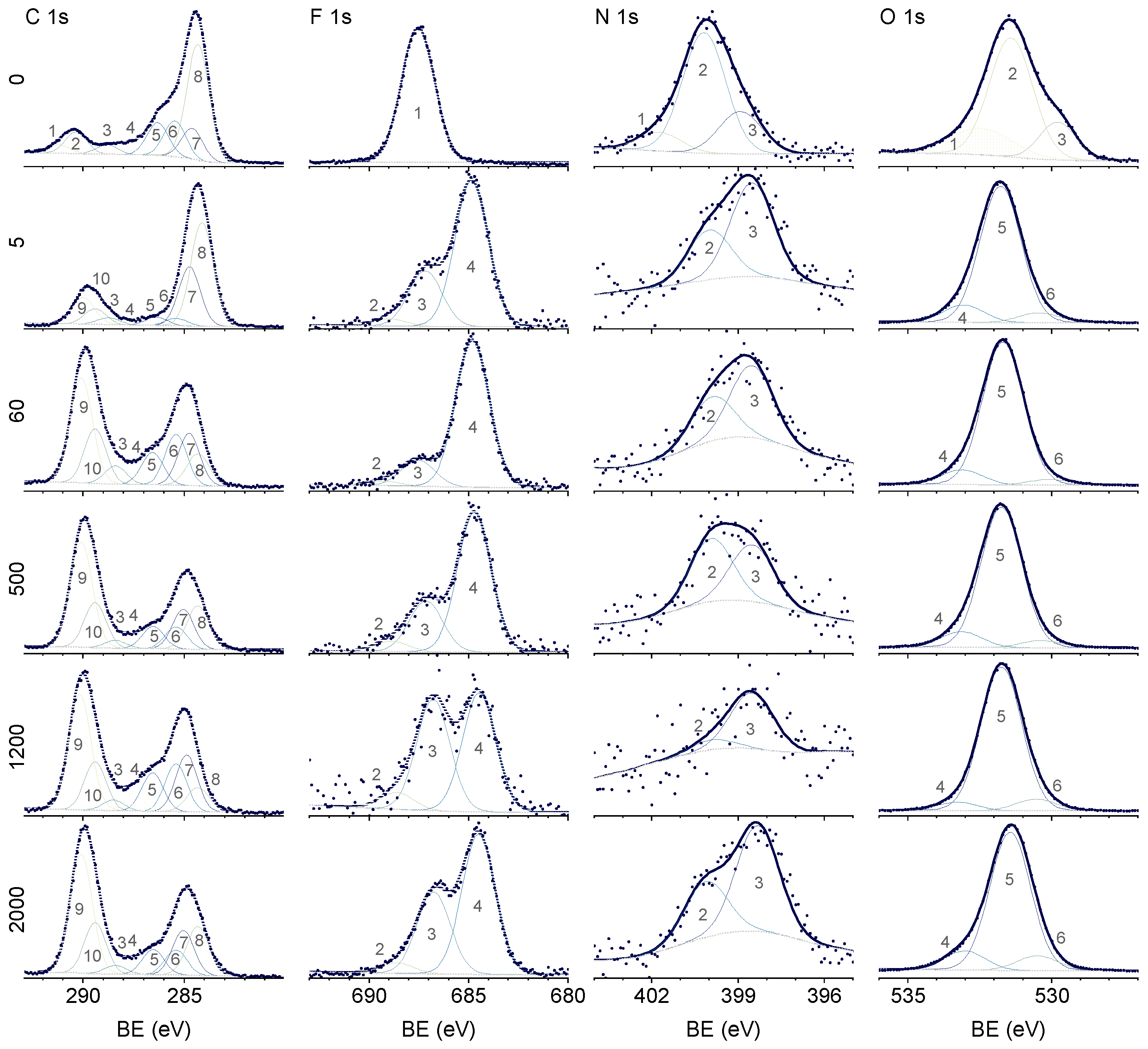

| Peak | Chem. bond | Component | Sample BE after cycling, eV | BE from references | ||||||

| 0 | 5 | 60 | 500 | 1200 | 2000 | BE, eV | Ref. | |||

| C 1s | C=C (sp2) | carbon black | 284.3 | 281.1 | 284.3 | 284.3 | 284.3 | 284.3 | 284.0–284.6 | [33,133,134] |

| H-C-C (sp3) | aliphatic chain | 284.6 | 284.6 | 284.7 | 285.0 | 284.9 | 285.0 | 284.6–286.0 | [33,133,134] | |

| C-N-C/C-O-C | PANI, ethers | 285.4 | 285.4 | 285.4 | 285.4 | 285.4 | 285.4 | 285.3–286.0 | [33,84,85,86] | |

| C-OH/C-N+-C/CH2-CH2 | alcohols, PANI, PVDF | 286.3 | 286.4 | 286.5 | 286.5 | 286.5 | 286.5 | 286.3–286.7 | [33,84,85,86] | |

| C=O | ketones, aldehydes | 287.6 | 287.6 | 287.6 | 287.6 | 287.6 | 287.6 | 287.1–288.1 | [33,133,134,135] | |

| R-F | organofluoric | 288.8 | 288.8 | 288.4 | 288.4 | 288.5 | 288.4 | 287.7–290.2 | [33,133,134] | |

| F-C-F | PVDF | 290.3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | [33] | |

| O-C(=O)-O | Li2CO3, semiorganic carbonates | - | 290.1 | 290.1 | 290.1 | 290.1 | 290.1 | 289.6–290.1 | [33,136,137] | |

| F 1s | C-F | PVDF | 687.5 | - | - | - | - | - | 687.3–687.9 | [33,138,139] |

| C-F | CnFm | - | 689.0 | 689.2 | 688.9 | 688.7 | 688.6 | 688.4–690.0 | [33,140,141,142] | |

| F-P-O | LixPOy-1Fz+1 | - | 687.2 | 687.5 | 687.1 | 686.8 | 686.8 | 686.1–687.9 | [33] | |

| Li-F | LiF | - | 684.6 | 684.7 | 684.7 | 684.5 | 684.5 | 684.5–685.0 | [33,143,144] | |

| N 1s | N+-H | oxidized amine, | 401.7 | - | - | - | - | - | 401.1–401.7 | [85,145,146] |

| N-H | benzenoid amine | 400.2 | 399.9 | 399.8 | 399.9 | 399.8 | 400.0 | 399.6–400.7 | [83,85,146] | |

| -N= | imine | 398.9 | 398.5 | 398.5 | 398.5 | 398.5 | 398.3 | 398.1–399.3 | [83,85,145,147] | |

| O 1s | Fe=O | FeOOH | 529.9 | - | - | - | - | - | 530.0–530.5 | [77,79,80] |

| Fe-OH | FeOOH | 531.4 | - | - | - | - | - | 531.2–531.6 | [77,79,80] | |

| S=O, S-O− |

SO42− | 532.5 | - | - | - | - | - | 532.2–532.6 | [81,82,142] | |

| Fe-O | Oxide matrix, FeOOH | - | 530.5 | 530.2 | 530.3 | 530.5 | 530.5 | 530.0–530.5 | [41,77,79,80] | |

| C=O, P=O, -OH | Alkoxide, carboxylate, esters, Li2CO3, LixPOy−1Fz+1 | - | 531.8 | 531.7 | 531.8 | 531.7 | 531.5 | 531.2–532.0 | [33,41,79] | |

| C-O-C, P-O-P | Organic carbonate, LixPOy−1Fz+1, LixPOy | 533.1 | 533.1 | 533.1 | 533.2 | 533.1 | 531.1–533.8 | [33,41] | ||

| Li 1s | Li-F Li-OLi P-OLi |

LiF, carboxylates, Li2CO3, ROLi, LixPOy−1Fz+1, LixPOy | - | 55.4 | 55.3 | 55.4 | 55.4 | 55.2 | 55.2 – 55.8 | [33,41,148] |

| Fe3+ | FeOOH | 55.7 | - | - | - | - | - | 55.6–55.8 | [132,149] | |

| Fe3+ | Oxide matrix | - | 55.8 | 55.8 | 55.8 | 55.8 | 55.8 | 55.6–55.8 | [132,149] | |

| Fe2+ | Oxide matrix | - | 53.7 | 53.7 | 53.7 | 53.7 | 53.7 | 53.7–53.8 | [132] | |

- The porosity of the electrode increases, opening the access of the electrolyte to a more electroactive material.

- The electrochemical milling of the electrode components first results in a sharp increase of the SEI amount, and, after SEI stabilizes, continued milling of FeOOH leads to an increase in capacity due to gradually improving contact of FeOOH with carbon black and PANI.

- The electrode reaches a stable capacity after 1200 cycles, and the achieved capacity value corresponds to the original capacity of the electrode, as C-rate (Figure 3a) testing after the end of the long cycling shows.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zubi, G.; Dufo-López, R.; Carvalho, M.; Pasaoglu, G. The Lithium-Ion Battery: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 89, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthiram, A. An Outlook on Lithium Ion Battery Technology. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 1063–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armand, M.; Axmann, P.; Bresser, D.; Copley, M.; Edström, K.; Ekberg, C.; Guyomard, D.; Lestriez, B.; Novák, P.; Petranikova, M.; et al. Lithium-Ion Batteries – Current State of the Art and Anticipated Developments. J. Power Sources 2020, 479, 228708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Shapter, J.G.; Li, Y.; Gao, G. Recent Progress of Advanced Anode Materials of Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 57, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Srivastava, S.K. Nanostructured Anode Materials for Lithium Ion Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 2454–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Nolan, A.M.; Lu, J.; Wang, J.; Yu, X.; Mo, Y.; Chen, L.; Huang, X.; Li, H. The Thermal Stability of Lithium Solid Electrolytes with Metallic Lithium. Joule 2020, 4, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, K.-C.; Zhang, X.; Qu, X.-L.; Hu, J.-J.; Li, H.-W.; Gao, M.-X.; Pan, H.-G.; Liu, Y.-F. Recently Developed Strategies to Restrain Dendrite Growth of Li Metal Anodes for Rechargeable Batteries. Rare Met. 2020, 39, 616–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-P.; Rahm, E.; Holze, R. Carbon Anode Materials for Lithium Ion Batteries. J. Power Sources 2003, 114, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, D.; Hain, H.; Lamp, P.; Maglia, F.; Stiaszny, B. Future High-Energy Density Anode Materials from an Automotive Application Perspective. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 17174–17198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poizot, P.; Laruelle, S.; Grugeon, S.; Dupont, L.; Tarascon, J.-M. Nano-Sized Transition-Metal Oxides as Negative-Electrode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Nature 2000, 407, 496–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Yan, P.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; An, Y.; Xing, J. Synthesis of Hierarchical CoO Nano/Microstructures as Anode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Nanomater. 2014, 2014, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subalakshmi, P.; Sivashanmugam, A. Nano Co3O4 as Anode Material for Li–Ion and Na-Ion Batteries: An Insight into Surface Morphology. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 5040–5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, T.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, J. Electrostatic Self-Assembly of Fe3O4 Nanoparticles on Graphene Oxides for High Capacity Lithium-Ion Battery Anodes. Energies 2013, 6, 4830–4840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, M.D.; Lee, J.Y. High Capacity Conversion Anodes in Li-Ion Batteries: A Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 10852–10905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debart, A.; Dupont, L.; Poizot, P.; Leriche, J.B.; Tarascon, J.M. A Transmission Electron Microscopy Study of the Reactivity Mechanism of Tailor-Made CuO Particles toward Lithium. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2001, 148, A1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, I.; Angelucci, M.; Verrelli, R.; Betti, M.G.; Panero, S.; Croce, F.; Mariani, C.; Scrosati, B.; Hassoun, J. Electrochemical Characteristics of Iron Oxide Nanowires during Lithium-Promoted Conversion Reaction. J. Power Sources 2014, 256, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, C.; Pan, H.; Zada, I.; Li, Y.; Bokhari, S.W.; Luan, R.Y.; Nigar, S.; Zhu, S. In Situ Growth of β-FeOOH on Hierarchically Porous Carbon as Anodes for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 283, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, J.; Zhou, H.; Martha, S.K.; Li, J.; Dai, S.; Pannala, S.; Wang, J.; Braun, P. V; Dudney, N.J.; Adcock, J. Molecular and Electrode Arcitectures for Multivalent Conversion Electrodes. ECS Meet. Abstr. 2014, MA2014-02, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonari, G.; Maroni, F.; Gabrielli, S.; Staffolani, A.; Tossici, R.; Palmieri, A.; Nobili, F. Synthesis and Characterization of Vanillin-Templated Fe2O3 Nanoparticles as a Sustainable Anode Material for Li-Ion Batteries. ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 1915–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salunkhe, T.T.; Varma, R.S.; Kadam, A.N.; Lee, S.-W.; Lee, Y.-C.; Hur, J.; Kim, I.T. Scraps to Superior Anodes for Li-Ion Batteries: Sustainable and Scalable Upgrading of Waste Rust. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 410, 124571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Gao, L.; Zheng, H.; Ji, M.; Tang, C.; Shen, T.; Zhang, Z. Synthesis of β-FeOOH and α-Fe 2 O 3 Nanorods and Electrochemical Properties of β-FeOOH. J. Mater. Chem. 2004, 14, 905–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y. Goethite Nanorods as Anode Electrode Materials for Rechargeable Li-Ion Batteries. Electrochem. commun. 2009, 11, 1696–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Yu, L.; Sun, M.; Cheng, G.; Lin, T.; Mo, Y.; Li, Z. Bunched Akaganeite Nanorod Arrays: Preparation and High-Performance for Flexible Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 296, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Xu, L.; Qian, Y. Ce-Doped α-FeOOH Nanorods as High-Performance Anode Material for Energy Storage. J. Power Sources 2016, 327, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Zhu, S.; Wang, J.; Liang, X.; Huang, H.; Huang, D.; Zhou, W.; Xu, S.; Guo, J. Silicon-Doped FeOOH Nanorods@graphene Sheets as High-Capacity and Durable Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 550, 149330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Li, Y.; Jin, T.; Jiang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Yao, J. Facile and Efficient Synthesis of Binary FeOOH/Fe2O3 Composite as a High-Performance Anode Material for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 896, 163026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Huang, J.; Tang, L.; Ma, M.; Deng, W.; Zhang, C. Confined Pulverization Promoting Durable Pseudocapacitance for FeOOH@PEDOT Anode in Li-Ion Battery. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2021, 882, 115005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amine, K.; Yasuda, H.; Yamachi, M. β-FeOOH, a New Positive Electrode Material for Lithium Secondary Batteries. J. Power Sources 1999, 81, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabuchi, T.; Katayama, Y.; Nukuda, T.; Ogumi, Z. β-FeOOH Thin Film as Positive Electrode for Lithium-Ion Cells. J. Power Sources 2009, 191, 640–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, K.; Yamada, I. ϵ-FeOOH: A Novel Negative Electrode Material for Li-and Na-Ion Batteries. ACS omega 2020, 5, 10115–10122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Xi, S.; Wei, C.; Zhang, W.; Du, Y.; Yan, Q.; Xu, Z. Superior Lithium Storage Properties of β-FeOOH. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1401517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabuchi, T.; Katayama, Y.; Nukuda, T.; Ogumi, Z. Surface Reaction of β-FeOOH Film Negative Electrode for Lithium-Ion Cells. J. Power Sources 2009, 191, 636–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, N.; Hausbrand, R.; Wittich, C.; Dimesso, L.; Jaegermann, W. XPS-Surface Analysis of SEI Layers on Li-Ion Cathodes: Part II. SEI-Composition and Formation inside Composite Electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, A833–A846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, M.; Lucht, B.L. Role of Lithium Salt on Solid Electrolyte Interface (SEI) Formation and Structure in Lithium Ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2014, 161, A1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, M.; Chalasani, D.; Abraham, D.P.; Chen, Y.; Bose, A.; Lucht, B.L. Lithium Ion Battery Graphite Solid Electrolyte Interphase Revealed by Microscopy and Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 1257–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peled, E. The Electrochemical Behavior of Alkali and Alkaline Earth Metals in Nonaqueous Battery Systems—the Solid Electrolyte Interphase Model. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1979, 126, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Maire, P.; Novák, P. A Review of the Features and Analyses of the Solid Electrolyte Interphase in Li-Ion Batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 6332–6341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiskanen, S.K.; Kim, J.; Lucht, B.L. Generation and Evolution of the Solid Electrolyte Interphase of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Joule 2019, 3, 2322–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parimalam, B.S.; Lucht, B.L. Reduction Reactions of Electrolyte Salts for Lithium Ion Batteries: LiPF6, LiBF4, LiDFOB, LiBOB, and LiTFSI. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, A251–A255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.J.; Li, J.; Daniel, C.; Mohanty, D.; Nagpure, S.; Wood, D.L. The State of Understanding of the Lithium-Ion-Battery Graphite Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) and Its Relationship to Formation Cycling. Carbon N. Y. 2016, 105, 52–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, D.C.; Waller, G.H.; Mansour, A.N.; Marschilok, A.C.; Takeuchi, K.J.; Takeuchi, E.S. Investigation of Solid Electrolyte Interphase Layer Formation and Electrochemical Reversibility of Magnetite, Fe3O4, Electrodes: A Combined X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy and X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 14257–14271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laruelle, S.; Grugeon, S.; Poizot, P.; Dollé, M.; Dupont, L.; Tarascon, J.-M. On the Origin of the Extra Electrochemical Capacity Displayed by MO/Li Cells at Low Potential. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2002, 149, A627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Światowska, J.; Maurice, V.; Zanna, S.; Seyeux, A.; Klein, L.H.; Marcus, P. Combined Surface and Electrochemical Study of the Lithiation/Delithiation Mechanism of the Iron Oxide Thin-Film Anode for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 21651–21661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, S.J.; Nobili, F.; Gunnella, R.; Ali, M.; Tossici, R.; Passerini, S.; Di Cicco, A. SEI Dynamics in Metal Oxide Conversion Electrodes of Li-Ion Batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 26379–26388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraytsberg, A.; Ein-Eli, Y. A Critical Review-Promises and Barriers of Conversion Electrodes for Li-Ion Batteries. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2017, 21, 1907–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Song, Z.; Gao, H.; Li, B.; Hu, T.; Liu, F.; Sohn, H.Y. The Structure-Directing Role of Graphene in Composites with Porous FeOOH Nanorods for Li Ion Batteries. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 41403–41409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.X.; He, L.H.; Shang, P.J.; Tang, Q.L.; Liu, Z.Q.; Liu, Hb.; Zhou, L.P. Micro-Sized and Nano-Sized Fe3O4 Particles as Anode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2011, 27, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, G.; Qu, K.; Ren, C.; Su, Y.; Fu, B.; Zi, M.; Dai, L.; Xiao, Q.; Xu, J.; Zhong, X. Epitaxial Array of Fe3O4 Nanodots for High Rate High Capacity Conversion Type Lithium Ion Batteries Electrode with Long Cycling Life. Nano Energy 2020, 74, 104876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wei, C.; Yan, Q.; Xu, Z.J. Controlled Synthesis of High-Performance β-FeOOH Anodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries and Their Size Effects. Nano Energy 2015, 13, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Liang, B.; Mou, X.; Liang, X.; Huang, H.; Huang, D.; Zhou, W.; Xu, S.; Guo, J. In-Situ Synthesis of F-Doped FeOOH Nanorods on Graphene as Anode Materials for High Lithium Storage. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 905, 164142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yang, X.; Zheng, M.; Xu, Y. Synthesis of β-FeOOH Nanorods Adhered to Pine-Biomass Carbon as a Low-Cost Anode Material for Li-Ion Batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 794, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raccichini, R.; Varzi, A.; Wei, D.; Passerini, S. Critical Insight into the Relentless Progression toward Graphene and Graphene-containing Materials for Lithium-ion Battery Anodes. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1603421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryan, A.M.; Santino, L.M.; Lu, Y.; Acharya, S.; D’Arcy, J.M. Conducting Polymers for Pseudocapacitive Energy Storage. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 5989–5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajik, S.; Beitollahi, H.; Nejad, F.G.; Shoaie, I.S.; Khalilzadeh, M.A.; Asl, M.S.; Van Le, Q.; Zhang, K.; Jang, H.W.; Shokouhimehr, M. Recent Developments in Conducting Polymers: Applications for Electrochemistry. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 37834–37856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.; You, J.; Park, M.-S.; Al Hossain, M.S.; Yamauchi, Y.; Kim, J.H. Conductive Polymers for Next-Generation Energy Storage Systems: Recent Progress and New Functions. Mater. Horizons 2016, 3, 517–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliseeva, S.N.; Kamenskii, M.A.; Tolstopyatova, E.G.; Kondratiev, V. V. Effect of Combined Conductive Polymer Binder on the Electrochemical Performance of Electrode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energies 2020, 13, 2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Han, D.; Lu, P. PEDOT Encapsulated β-FeOOH Nanorods: Synthesis, Characterization and Application for Sodium-Ion Batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 238, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Li, S.; Lee, P.S. A Fiber Asymmetric Supercapacitor Based on FeOOH/PPy on Carbon Fibers as an Anode Electrode with High Volumetric Energy Density for Wearable Applications. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 10794–10801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Du, K.; Zhao, X.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Ren, K.; Huang, Y.; Wang, H.; Yao, S.; An, C. Integrated FeOOH Nanospindles with Conductive Polymer Layer for High-Performance Supercapacitors. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 728, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaebe, H.; Higuchi, S.; Kanamura, K.; Fujimoto, H.; Takehara, Z. Discharge and Charge Characteristics of Amorphous FeOOH Including Aniline (Aan-FeOOH): Influence of Preparation Conditions on Discharge and Charge Characteristics. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1995, 142, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zheng, Y.; Xian, J.; Feng, Z.; Li, Z.; Cui, F. A Light-Enhanced α-FeOOH Nanowires/Polyaniline Anode for Improved Electricity Generation Performance in Microbial Fuel Cells. Chemosphere 2022, 296, 133994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, H.; Zhang, B.; Cui, C.; Xu, Y. Polyaniline/FeOOH Composite for Removal of Acid Orange II from Aqueous Solutions. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 278, 125701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, S.; Tao, L.; Wang, R.; El Hankari, S.; Chen, R.; Wang, S. Plasma-assisted Synthesis and Surface Modification of Electrode Materials for Renewable Energy. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1705850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, T.; Aziz, A.; Khan, M.A.; Andleeb, S.; Mahmood, H.; Khan, A.A.; Khan, R.; Shafique, M. Surfactant Assisted Synthesis of ZnO Nanostructures Using Atmospheric Pressure Microplasma Electrochemical Process with Antibacterial Applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2018, 228, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehrlein, G.S.; Hamaguchi, S. Foundations of Low-Temperature Plasma Enhanced Materials Synthesis and Etching. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2018, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Chai, Z.; Hu, W. Low-Temperature Plasma Synthesis of Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene Based Materials and Their Fuel Cell Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 8821–8834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiya-Djowe, A.; Laminsi, S.; Noupeyi, G.L.; Gaigneaux, E.M. Non-Thermal Plasma Synthesis of Sea-Urchin like α-FeOOH for the Catalytic Oxidation of Orange II in Aqueous Solution. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 176–177, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beletskii, E. V.; Kamenskii, M.A.; Alekseeva, E. V.; Volkov, A.I.; Lukyanov, D.A.; Anishchenko, D. V.; Radomtseu, A.O.; Reveguk, A.A.; Glumov, O. V.; Levin, O. V. One-Step Atmospheric Plasma-Assisted Synthesis of FeOOH and FeOOH/Graphite High Performance Anode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 597, 153698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, M.; Bour, J.; Petersen, J.; Arnoult, C.; Ettingshausen, F.; Roth, C.; Ruch, D. Atmospheric Plasma Deposition: A New Pathway in the Design of Conducting Polymer-Based Anodes for Hydrogen Fuel Cells. Fuel Cells 2010, 10, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.-S.; Kim, D.H.; Shin, B.J.; Tae, H.-S. Synthesis and Characterization of Nanofibrous Polyaniline Thin Film Prepared by Novel Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Polymerization Technique. Materials (Basel). 2016, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S. In-Situ Iodine Doping Characteristics of Conductive Polyaniline Film Polymerized by Low-Voltage-Driven Atmospheric Pressure Plasma. Polymers (Basel). 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, J.; Choi, B.G.; Lee, S.C.; Lee, K.G.; Chang, S.; Han, Y.; Lee, Y.B.; Lee, H.U.; Kwon, S.; Lee, G. Hierarchical Hollow Spheres of Fe2O3@ Polyaniline for Lithium Ion Battery Anodes. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 6250–6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Han, H.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, W.; Sun, H. Polyaniline Coated Fe 3 O 4 Hollow Nanospheres as Anode Materials for Lithium Ion Batteries. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2017, 1, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Bi, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, H. Schwertmannite: Occurrence, Properties, Synthesis and Application in Environmental Remediation. Rsc Adv. 2018, 8, 33583–33599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.P.; Sen, S.K. Calculation of Multiplet Structure of Core P-Vacancy Levels. II. Phys. Rev. B 1975, 12, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosvenor, A.P.; Kobe, B.A.; Biesinger, M.; Mcintyre, N. Investigation of Multiplet Splitting of Fe 2p XPS Spectra and Bonding in Iron Compounds. Surf. Interface Anal. 2004, 36, 1564–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, N.S.; Zetaruk, D.G. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopic Studies of Iron Oxides. Anal. Chem. 1977, 49, 1521–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descostes, M.; Mercier, F.; Thromat, N.; Beaucaire, C.; Gautier-Soyer, M. Use of XPS in the Determination of Chemical Environment and Oxidation State of Iron and Sulfur Samples: Constitution of a Data Basis in Binding Energies for Fe and S Reference Compounds and Applications to the Evidence of Surface Species of an Oxidized Py. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2000, 165, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemelewski, W.D.; Lee, H.-C.; Lin, J.-F.; Bard, A.J.; Mullins, C.B. Amorphous FeOOH Oxygen Evolution Reaction Catalyst for Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 2843–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, I.D.; Sherwood, P.M.A. Photoemission and Electronic Structure of FeOOH: Distinguishing between Oxide and Oxyhydroxide. Phys. Rev. B 1989, 40, 6386–6392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, B.J.; Hamrin, K.; Johansson, G.; Gelius, U.; Fahlman, A.; Nordling, C.; Siegbahn, K. Molecular Spectroscopy by Means of ESCA II. Sulfur Compounds. Correlation of Electron Binding Energy with Structure. Phys. Scr. 1970, 1, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumkin, A. V.; Kraut-Vass, A.; Gaarenstroom, S.W.; Powell, C.J. NIST X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Database.

- Waghmode, B.J.; Patil, S.H.; Jahagirdar, M.M.; Patil, V.S.; Waichal, R.P.; Malkhede, D.D.; Sathaye, S.D.; Patil, K.R. Studies on Morphology of Polyaniline Films Formed at Liquid–Liquid and Solid–Liquid Interfaces at 25 and 5 °C, Respectively, and Effect of Doping. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2014, 292, 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snauwaert, P.; Lazzaroni, R.; Riga, J.; Verbist, J.J. Electronic Structure of Polyaniline and Substituted Derivatives. Synth. Met. 1987, 18, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golczak, S.; Kanciurzewska, A.; Fahlman, M.; Langer, K.; Langer, J.J. Comparative XPS Surface Study of Polyaniline Thin Films. Solid State Ionics 2008, 179, 2234–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriello, R.; Carbone, M.E.; Coviello, D.; Guerrieri, A.; Salvi, A.M. Improved Stability of Thin Insulating Poly(o-Aminophenol) Films in Aqueous Solutions through an Efficient Strategy for Electrosynthesis under Neutral PH Conditions: Electrochemical and XPS Investigation. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2020, 867, 114183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yoshino, T. Electrical Conductivity of Diaspore, δ-AlOOH and ε-FeOOH. Am. Mineral. J. Earth Planet. Mater. 2021, 106, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focke, W.W.; Wnek, G.E.; Wei, Y. Influence of Oxidation State, PH, and Counterion on the Conductivity of Polyaniline. J. Phys. Chem. 1987, 91, 5813–5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chulkin, P.; Łapkowski, M. An Insight into Ionic Conductivity of Polyaniline Thin Films. Materials (Basel). 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, K.; Inouye, K. Electrical Conductivity Changes in α-FeOOH and β-FeOOH upon Surface Dehydration. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1976, 49, 3689–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadra, J.; Al-Thani, N.J.; Madi, N.K.; Al-Maadeed, M.A. Effects of Aniline Concentrations on the Electrical and Mechanical Properties of Polyaniline Polyvinyl Alcohol Blends. Arab. J. Chem. 2017, 10, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk, K.; Matysiak, W.; Tański, T.; Janeczek, H.; Schab-Balcerzak, E.; Libera, M. Effect of Polyaniline Content and Protonating Dopants on Electroconductive Composites. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuqin, C.; Hong, L.; Lie, W.; Tianhong, L. Irreversible Capacity Loss of Graphite Electrode in Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Power Sources 1997, 68, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.; Striebel, K.A. Effect of Electrode Density on Cycle Performance and Irreversible Capacity Loss for Natural Graphite Anode in Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Power Sources 2003, 119–121, 934–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.F.; Guo, Z.; Chen, Z.; Liu, H. α-Fe2O3 as an Anode Material with Capacity Rise and High Rate Capability for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Mater. Res. Bull. 2011, 46, 858–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Choi, W.; Yoon, J.; Um, J.H.; Lee, W.; Kim, J.; Cabana, J.; Yoon, W.S. Exploring Anomalous Charge Storage in Anode Materials for Next-Generation Li Rechargeable Batteries. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 6934–6976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Ding, N.; Wang, L.; Yu, Y.; Lieberwirth, I. Some New Facts on Electrochemical Reaction Mechanism for Transition Metal Oxide Electrodes. J. Power Sources 2009, 189, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.; Wen, W.; Li, J.; Lin, Y.; Lai, H.; Huang, Z. Nano-Crystalline FeOOH Mixed with SWNT Matrix as a Superior Anode Material for Lithium Batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2014, 23, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Ma, X.; Mao, H.; Shao, W.; Xu, L.; He, Y.; Qian, Y. Mn-Doped α-FeOOH Nanorods and α-Fe 2 O 3 Mesoporous Nanorods: Facile Synthesis and Applications as High Performance Anodes for LIBs. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2015, 1, 1400057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Wu, J.; Xu, J.; Dravid, V.P. Atomic Resolution Study of Reversible Conversion Reaction in Metal Oxide Electrodes for Lithium-Ion Battery. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 11560–11566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezesinski, T.; Wang, J.; Tolbert, S.H.; Dunn, B. Ordered Mesoporous α-MoO3 with Iso-Oriented Nanocrystalline Walls for Thin-Film Pseudocapacitors. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, D.; Zhu, C.; Yang, P.; Xia, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Fan, X.; Savilov, S. V.; Lin, J.; Fan, H.J.; et al. Array of Nanosheets Render Ultrafast and High-Capacity Na-Ion Storage by Tunable Pseudocapacitance. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forghani, M.; Donne, S.W. Method Comparison for Deconvoluting Capacitive and Pseudo-Capacitive Contributions to Electrochemical Capacitor Electrode Behavior. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, A664–A673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, N.; Park, J.H.; Choi, J.; Jin, J.; Chun, J.; Jung, I.G.; Jeong, J.; Park, J.-G.; Lee, S.M.; Kim, H.J.; et al. Nanoparticulate Iron Oxide Tubes from Microporous Organic Nanotubes as Stable Anode Materials for Lithium Ion Batteries. Angew. Chemie 2012, 124, 6730–6734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Du, Y. Gelatin Assisted Wet Chemistry Synthesis of High Quality β-FeOOH Nanorods Anchored on Graphene Nanosheets with Superior Lithium-Ion Battery Application. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 17504–17509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, S.; Xin, C.; Wang, L.; Shi, C.; Lu, L.; Zhang, C. Synthesis and Electrochemical Property of FeOOH/Graphene Oxide Composites. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.; Di Lecce, D.; Hassoun, J. A High-Voltage, Multi-Metal LiNi0. 35Cu0. 1Mn1. 45Fe0. 1O4 Spinel Cathode for Lithium Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 30537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.; Alvarado, J.; Zhu, J.; Yue, Y.; Xin, H.L.; Nordlund, D.; Lin, F.; Doeff, M.M. Structural Degradation of Layered Cathode Materials in Lithium-Ion Batteries Induced by Ball Milling. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, A1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Sarkar, A.; Li, Z.; Lu, Y.; Velasco, L.; Bhattacharya, S.S.; Brezesinski, T.; Hahn, H.; Breitung, B. High Entropy Oxides as Anode Material for Li-Ion Battery Applications: A Practical Approach. Electrochem. commun. 2019, 100, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Xu, G.; Wang, C.; Xu, L.; Zhang, K. Horsetail-Derived Si@N-Doped Carbon as Low-Cost and Long Cycle Life Anode for Li-Ion Half/Full Cells. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 264, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Xia, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, D.; Ai, C.; Lin, S.; Wang, Y.; Deng, S.; Shen, S.; Wang, X.; et al. Superior High-Rate Lithium-Ion Storage on Ti2Nb10O29 Arrays via Synergistic TiC/C Skeleton and N-Doped Carbon Shell. Nano Energy 2018, 54, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Xie, X.; Xia, B. Green Synthesis of Dual Carbon Conductive Network-Encapsulated Hollow SiOx Spheres for Superior Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 19959–19967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, T.; Fan, X.; Cao, L.; Chen, J.; Hou, S.; Ji, X.; Chen, L.; Li, S.; Zhou, X.; Hu, E.; et al. Designing In-Situ-Formed Interphases Enables Highly Reversible Cobalt-Free LiNiO2 Cathode for Li-Ion and Li-Metal Batteries. Joule 2019, 3, 2550–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Gao, R.; Xiao, X.; Yu, Q.; Wang, C.; Waluyo, I.; Ding, J.; Hunt, A.; et al. A Surface Se-Substituted LiCo[O2−δSeδ] Cathode with Ultrastable High-Voltage Cycling in Pouch Full-Cells. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2005182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Qian, J.; Yang, H.; Zhong, F.; Ai, X. Chemically Prelithiated Hard-Carbon Anode for High Power and High Capacity Li-Ion Batteries. Small 2020, 16, 1907602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, M.-Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, J.; Tian, Y.-F.; Yin, Y.-X.; Zhang, C.-J.; Jiang, K.-C.; Xu, Q.; Li, H.-L.; Guo, Y.-G. Enabling SiOx/C Anode with High Initial Coulombic Efficiency through a Chemical Pre-Lithiation Strategy for High-Energy-Density Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 27202–27209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, T.; Li, B.; Wang, Q.; Hao, J.; Huang, B.; Gu, F.L.; Xu, H.; Liu, P.; Tong, Y. Large-Scale Electric-Field Confined Silicon with Optimized Charge-Transfer Kinetics and Structural Stability for High-Rate Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 7066–7076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montella, C. Discussion of the Potential Step Method for the Determination of the Diffusion Coefficients of Guest Species in Host Materials: Part I. Influence of Charge Transfer Kinetics and Ohmic Potential Drop. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2002, 518, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Jiang, Z.-J.; Yang, L.; Cheng, S.; Liu, M. A High-Performance Anode for Lithium Ion Batteries: Fe3O4 Microspheres Encapsulated in Hollow Graphene Shells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 11847–11856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.-M.; Song, M.-S.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, H.-S.; Park, M.-S.; Lee, J.-Y.; Liu, H.K.; Dou, S.X. A Study on the Charge–Discharge Mechanism of Co3O4 as an Anode for the Li Ion Secondary Battery. Electrochim. Acta 2005, 50, 3667–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyun, S.-I.; Bae, J.-S. The Ac Impedance Study of Electrochemical Lithium Intercalation into Porous Vanadium Oxide Electrode. Electrochim. Acta 1996, 41, 919–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, Y.; Emborg, M.; Cwirzen, A. Estimation of Specific Surface Area of Particles Based on Size Distribution Curve. Mag. Concr. Res. 2018, 70, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabella, F.M. Internal Reflection Spectroscopy: Theory and Applications; CRC Press, 1992; Vol. 15, ISBN 0824787307. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, M.; Tian, J.; Xie, H.; Kang, Y.; Shan, Z. Nano-Silicon/Polyaniline Composites with an Enhanced Reversible Capacity as Anode Materials for Lithium Ion Batteries. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2015, 19, 1773–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, G.; Chen, Y.; Ross, P.N. The Reaction of Lithium with Dimethyl Carbonate and Diethyl Carbonate in Ultrahigh Vacuum Studied by X-Ray Photoemission Spectroscopy. Langmuir 1999, 15, 1470–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Kadam, S.; Li, H.; Shi, S.; Qi, Y. Review on Modeling of the Anode Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) for Lithium-Ion Batteries. npj Comput. Mater. 2018, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markevich, E.; Salitra, G.; Hartmann, P.; Kulisch, J.; Aurbach, D.; Park, K.-J.; Yoon, C.; Sun, Y.-K. New Insights Related to Rechargeable Lithium Batteries: Li Metal Anodes, Ni Rich LiNi x Co y Mn z O 2 Cathodes and Beyond Them. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, A5265–A5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeev, K.K.; Kim, E.; Nam, J.; Lee, S.; Mun, J.; Kim, T.-H. Chitosan-Grafted-Polyaniline Copolymer as an Electrically Conductive and Mechanically Stable Binder for High-Performance Si Anodes in Li-Ion Batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 333, 135532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lim, S.; Tron, A.; Mun, J.; Kim, Y.-J.; Yim, T.; Kim, T.-H. Polymeric Binder Based on PAA and Conductive PANI for High Performance Silicon-Based Anodes. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 101622–101625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zeng, X.; Tang, R.; Wei, L. Conducting Polyaniline/Poly (Acrylic Acid)/Phytic Acid Multifunctional Binders for Si Anodes in Lithium Ion Batteries. Ionics (Kiel). 2019, 25, 5323–5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-Y.; Li, C.-H.; Wang, D.-Y.; Chen, C.-C. Chemical Doping of a Core–Shell Silicon Nanoparticles@polyaniline Nanocomposite for the Performance Enhancement of a Lithium Ion Battery Anode. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 1280–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, T.; Hayes, P. Analysis of XPS Spectra of Fe2+ and Fe3+ Ions in Oxide Materials. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 254, 2441–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, P.M.V.R.A.R. Physical Methods in Chemistry and Nano Science; Rice University, 2015.

- Morgan, D.J. Comments on the XPS Analysis of Carbon Materials. C 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Wang, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, T.; Wu, T.; Dong, C.; Liu, G. Tuning the Oxidation Degree of Graphite toward Highly Thermally Conductive Graphite/Epoxy Composites. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 7473–7483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Choi, W. Surface Modification of Over-Lithiated Layered Oxides with PEDOT:PSS Conducting Polymer in Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2015, 162, A743–A748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximov, M.; Nazarov, D.; Rumyantsev, A.; Koshtyal, Y.; Ezhov, I.; Mitrofanov, I.; Kim, A.; Medvedev, O.; Popovich, A. Atomic Layer Deposition of Lithium–Nickel–Silicon Oxide Cathode Material for Thin-Film Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energies 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedryvère, R.; Maccario, M.; Croguennec, L.; Le Cras, F.; Delmas, C.; Gonbeau, D. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Investigations of Carbon-Coated LixFePO4 Materials. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 7164–7170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beletskii, E. V.; Fedorova, A.A.; Lukyanov, D.A.; Kalnin, A.Y.; Ershov, V.A.; Danilov, S.E.; Spiridonova, D. V.; Alekseeva, E. V.; Levin, O. V. Switchable Resistance Conducting-Polymer Layer for Li-Ion Battery Overcharge Protection. J. Power Sources 2021, 490, 229548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.P.; Navarro-Marín, G.; Estévez-Hernández, O.; Farías-Sánchez, M.H. Angle-Resolved X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Study of the Thiourea Derivative Adsorption on Au (111) from Ethanolic Solution. Rev. Cuba. Fis. 2017, 34, 108–111. [Google Scholar]

- Kassis, C.M.; Steehler, J.K.; Linton, R.W. Characterization of 1,1-Dihydroperfluorooctyl Acrylate (PFOA) by XPS. Surf. Sci. Spectra 1994, 3, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High Resolution XPS of Organic Polymers: The Scienta ESCA300 Database (Beamson, G.; Briggs, D.). J. Chem. Educ. 1993, 70. [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Zheng, X.; Fang, G.; Pan, Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, M. A Novel Electrolyte Additive for Improving the Interfacial Stability of LiMn(2)O(4) Cathode Lithium-Ion Batteries at Elevated Temperature. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 38831–38835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, A.; Carvalho, D.; Ehteshami-Flammer, N.; Paillard, E.; Porcher, W.; Brun-Buisson, D.; Ducros, J.-B.; Meatza, I.; Eguía-Barrio, A.; Trad, K.; et al. A Post-Mortem Study of Stacked 16 Ah Graphite//LiFePO4 Pouch Cells Cycled at 5 °C. Batteries 2019, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.T.; Neoh, K.G.; Khor, S.H.; Tan, K.L.; Tan, B.T.G. X.p.s. Studies of Charge Transfer Interactions in Some Polyaniline Complexes. Polymer (Guildf). 1990, 31, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quílez-Bermejo, J.; Morallón, E.; Cazorla-Amorós, D. Polyaniline-Derived N-Doped Ordered Mesoporous Carbon Thin Films: Efficient Catalysts towards Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Polymers (Basel). 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.N.; Gaillard, F.; Bouyssoux, G.; Sartre, A. High-Resolution XPS Studies of Electrochemically Synthesized Conducting Polyaniline Films. Synth. Met. 1990, 36, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, O.; Hartmann, P.; Younesi, R.; Markovits, I.I.E.; Rinaldi, A.; Janek, J.; Yazami, R. A Gamma Fluorinated Ether as an Additive for Enhanced Oxygen Activity in Li–O 2 Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 19061–19067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagus, P.S.; Ilton, E.S.; Nelin, C.J. The Interpretation of XPS Spectra: Insights into Materials Properties. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2013, 68, 273–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.T. ARCHAEOMETRY AND ANTIQUE ANALYSIS | Metallic and Ceramic Objects. In Worsfold, P., Townshend, A., Poole, C.B.T.-E. of A.S. (Second E., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, 2005; pp. 117–123. ISBN 978-0-12-369397-6. [Google Scholar]

- Tomar, B.S.; Shahin, A.; Tirumkudulu, M.S. Cracking in Drying Films of Polymer Solutions. Soft Matter 2020, 16, 3476–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Zhao, H.; Lv, P.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Xia, Q. Electrochemical Properties of Iron Oxides/Carbon Nanotubes as Anode Material for Lithium Ion Batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 274, 1091–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.-W.; Zhang, D.-W.; Zang, Y.; Sun, X.; Cheng, B.; Ding, C.-X.; Yu, Y.; Chen, C.-H. Li and Na Storage Behavior of Bowl-like Hollow Co3O4 Microspheres as an Anode Material for Lithium-Ion and Sodium-Ion Batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 132, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Specific capacity, mA∙h∙g−1 (current density) | Stability, capacity retention (cycles) |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe3O4/graphene sheets | 600 (0.1 A∙g−1) | 80% (100) | [13] |

| Functionalized porous carbon/β-FeOOH | 737.1 (0.2 A∙g−1) | 122% (350) | [17] |

| Fe2O3 nanotubes | 950 (0.05 A∙g−1) | 98% (30) | [104] |

| β-FeOOH | 275 (0.1 mA∙cm−2) | n/a | [21] |

| Carbon cloth/ β-FeOOH nanorod arrays | 2840 (1 A∙g−1) | 90% (150) | [23] |

| Ce-doped α-FeOOH nanorods | 1260 (0.1 A∙g−1) | 86% (800) | [24] |

| Si-doped FeOOH nanorods@graphene sheets | 1370.5 (0.1 A∙g−1) | >100% (200) | [25] |

| Graphene/FeOOH | 1100 (0.1 A∙g−1) | n/a | [46] |

| β-FeOOH/rGO | 781.5 (0.1 A∙g−1) | n/a ~90% (100) | [105] |

| FeOOH@PEDOT | 1341 (0.5 A∙g−1) | 113.6% (270) | [27] |

| Biomass carbon/β -FeOOH | 1450 (0.2C) | 64% (100) | [51] |

| FeOOH/GO | 1437 (0.1 A∙g−1) | 93.35% (100) | [106] |

| FeOOH/SWNT | 905 (0.1 A∙g−1) | ~95% (180) | [98] |

| β-FeOOH | ~1400 (0.2 A∙g−1) | ~43% (1 to 600) ~210% (70 to 600) |

[31] |

| Mn-doped α-FeOOH | 1147 (0.5 A∙g−1) | 184% (90 to 300) | [99] |

| α-Fe2O3 | 1119 (1C) | 176% (600) | [95] |

| FeOOH | 640 (0.05 A∙g−1) and 356 (1.2 A∙g−1) | 245% from 150th to 2000th cycle (356 mA∙h∙g−1 end value) |

Previous work [68] |

| FeOOH/Gr | 840 (0.05 A∙g−1) and 543 (1.2 A∙g−1) | 206% from 60th to 2000th cycle (543 mA∙h∙g−1 end value) |

Previous work [68] |

| FeOOH/PANI | 1600 (0.05 A∙g−1) 767 (1.2 A∙g−1) |

540% from 70th to 2000th cycle (767 mA∙h∙g−1 end value) |

This work |

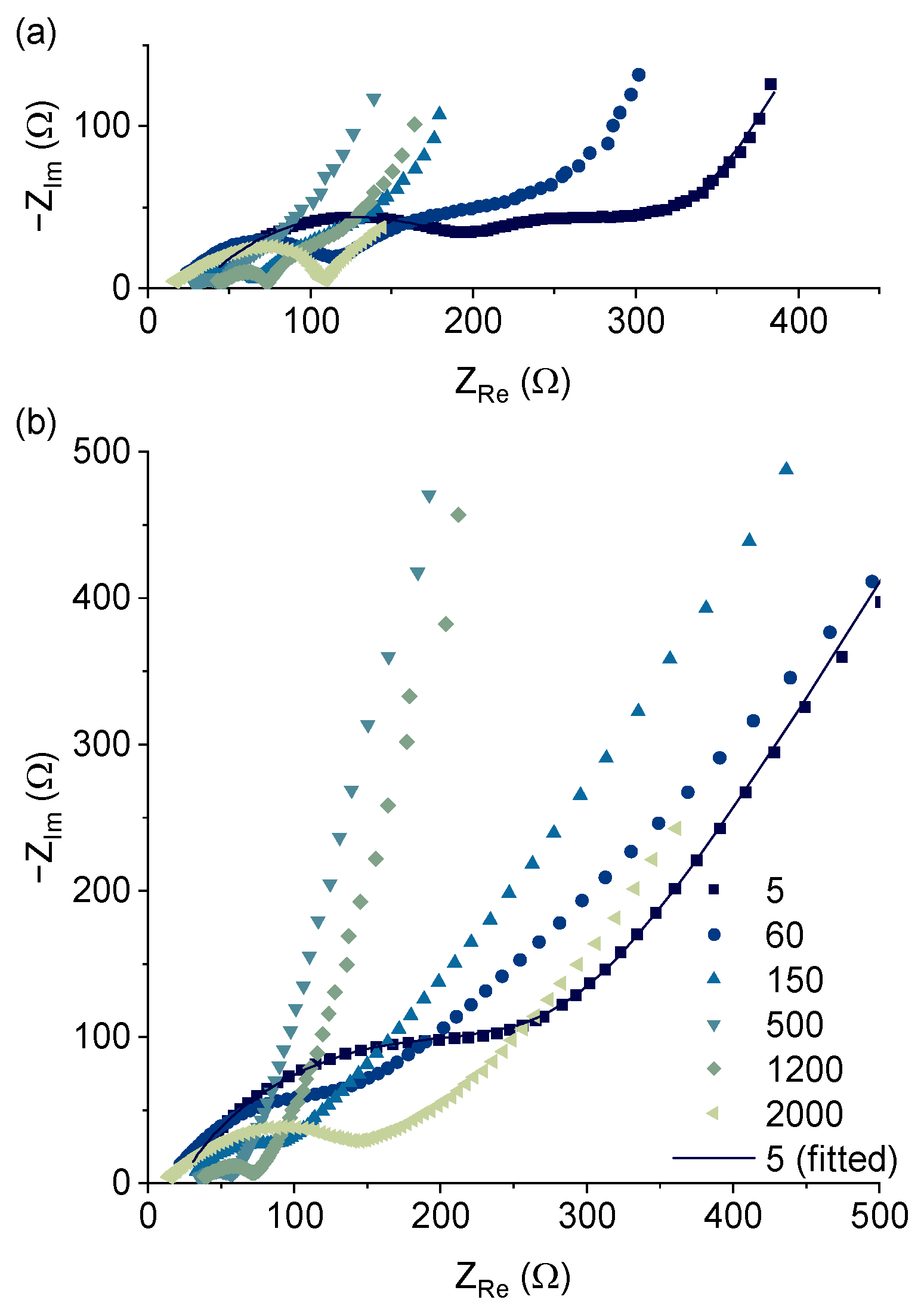

| Cycle no. | Rs, Ω | R1, Ω | Q1, F | a | σ, Ω∙s−0.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 23.4 | 164 | 1.8∙10−5 | 0.79 | 1200 |

| 60 | 13.8 | 93.8 | 2.6∙10−5 | 0.77 | 1130 |

| 150 | 29.9 | 45.0 | 2.3∙10−5 | 0,82 | 536 |

| 500 | 34.4 | 18.3 | 7.8∙10−5 | 0.80 | 90.1 |

| 1200 | 37.6 | 31.2 | 9.9∙10−5 | 0.74 | 52.3 |

| 2000 | 12.4 | 138 | 9.9∙10−5 | 0.58 | 126 |

| Cycle | Rs, Ω | R1, Ω | Q1, F | a1 | R2, Ω | Q2, F | a2 | σ, Ω∙s−0.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 32 | 76 | 3.1∙10−3 | 0.78 | 180 | 1.1∙10−4 | 0.56 | 27 |

| 60 | 17 | 76 | 5.4∙10−3 | 0.75 | 100 | 8.4∙10−5 | 0.64 | 30 |

| 150 | 29 | 25 | 1.6∙10−2 | 0.83 | 37 | 6.3∙10−5 | 0.75 | 24 |

| 500 | 28 | 37 | 2.7∙10−2 | 0.88 | 17 | 9.4∙10−5 | 0.81 | 13 |

| 1200 | 44 | 49 | 2.4∙10−2 | 0.86 | 30 | 1.1∙10−4 | 0.73 | 9.8 |

| 2000 | 12 | 58 | 6.6∙10−3 | 0.78 | 36 | 1.1∙10−4 | 0.56 | 20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).