Submitted:

22 November 2023

Posted:

23 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

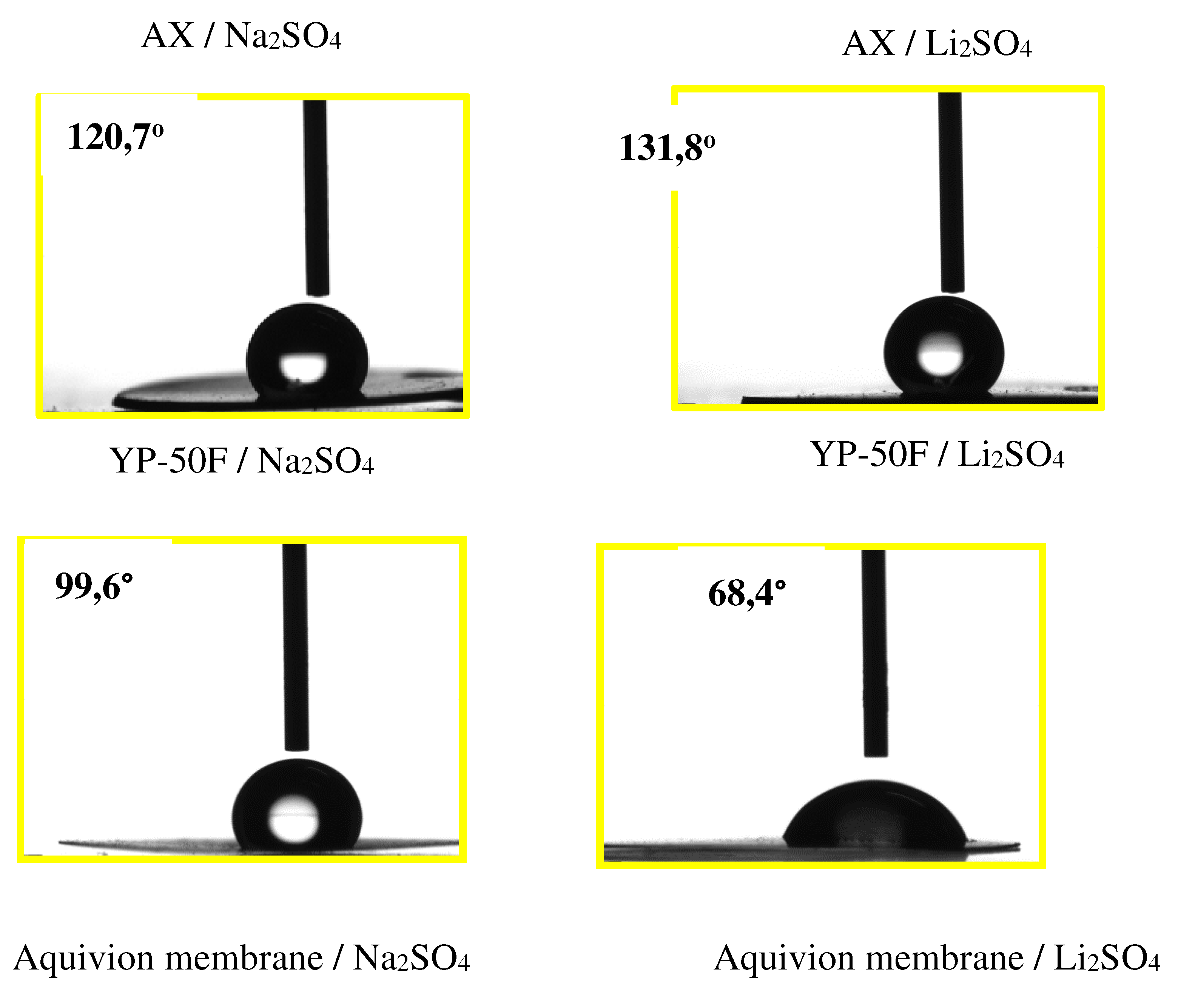

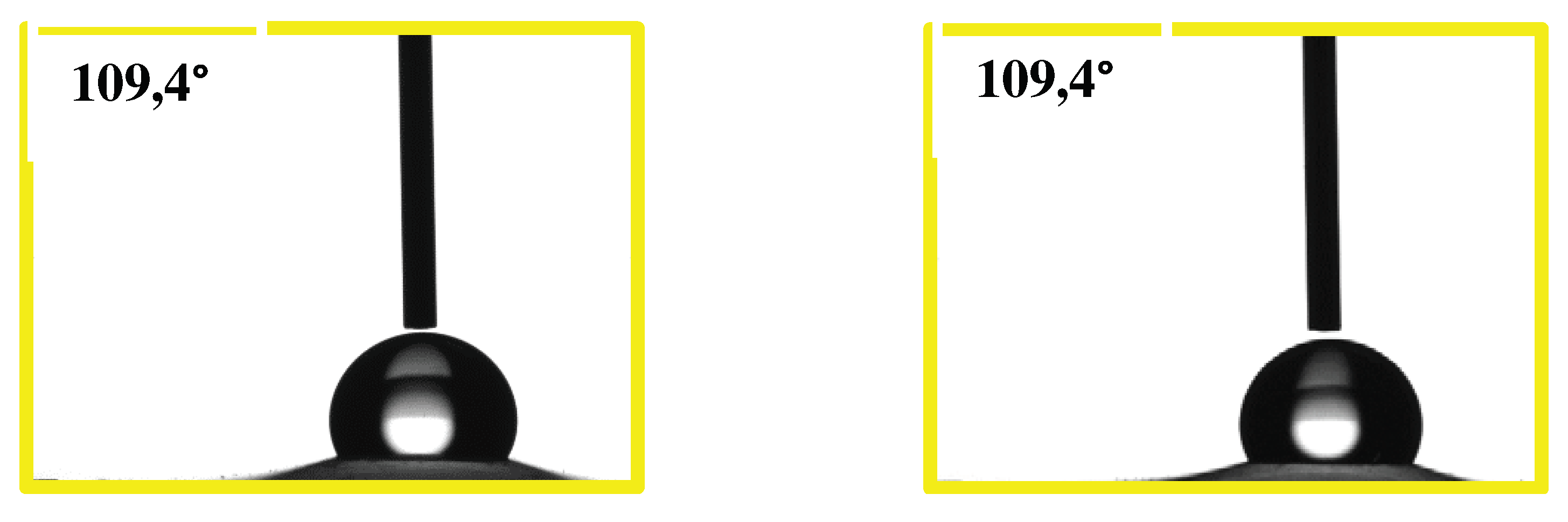

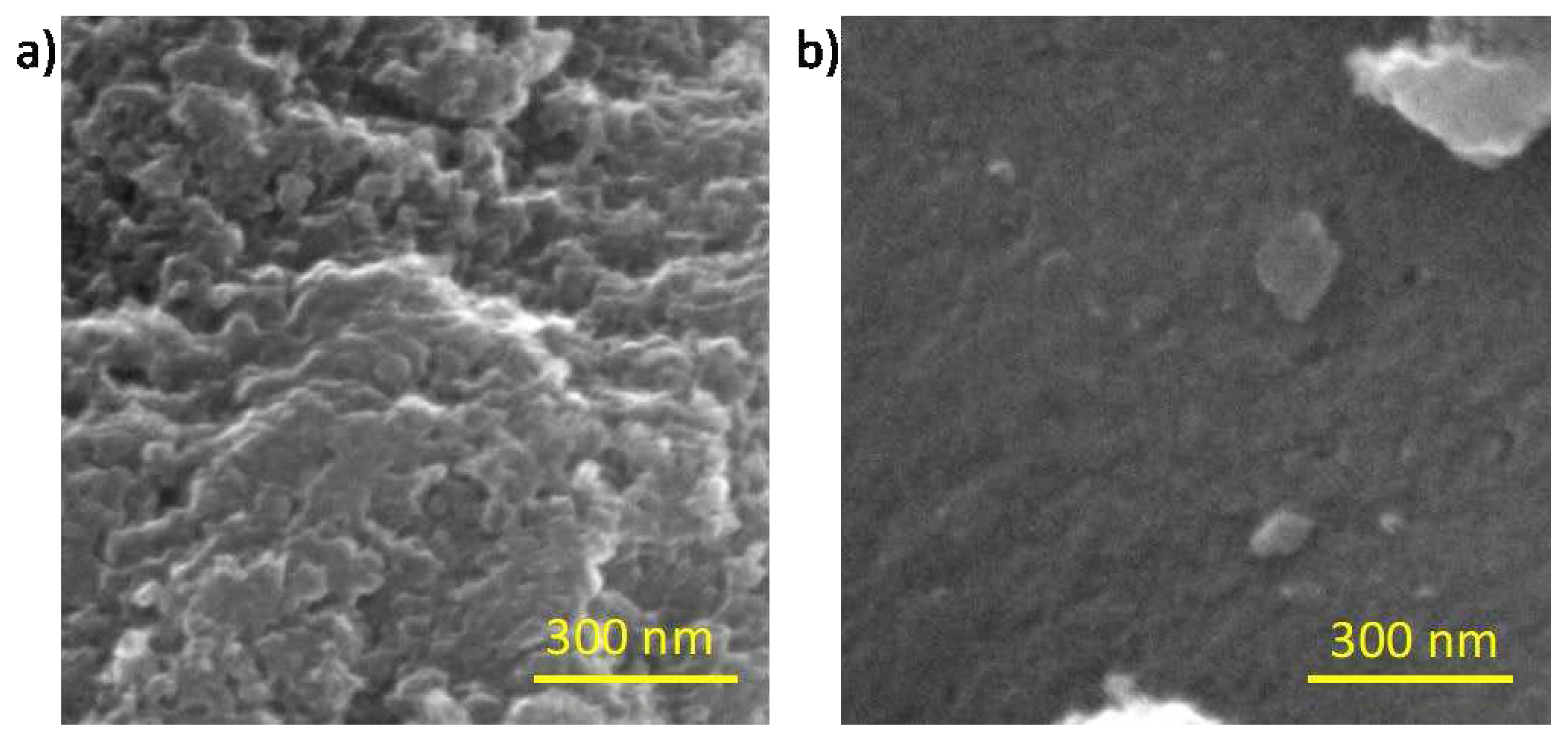

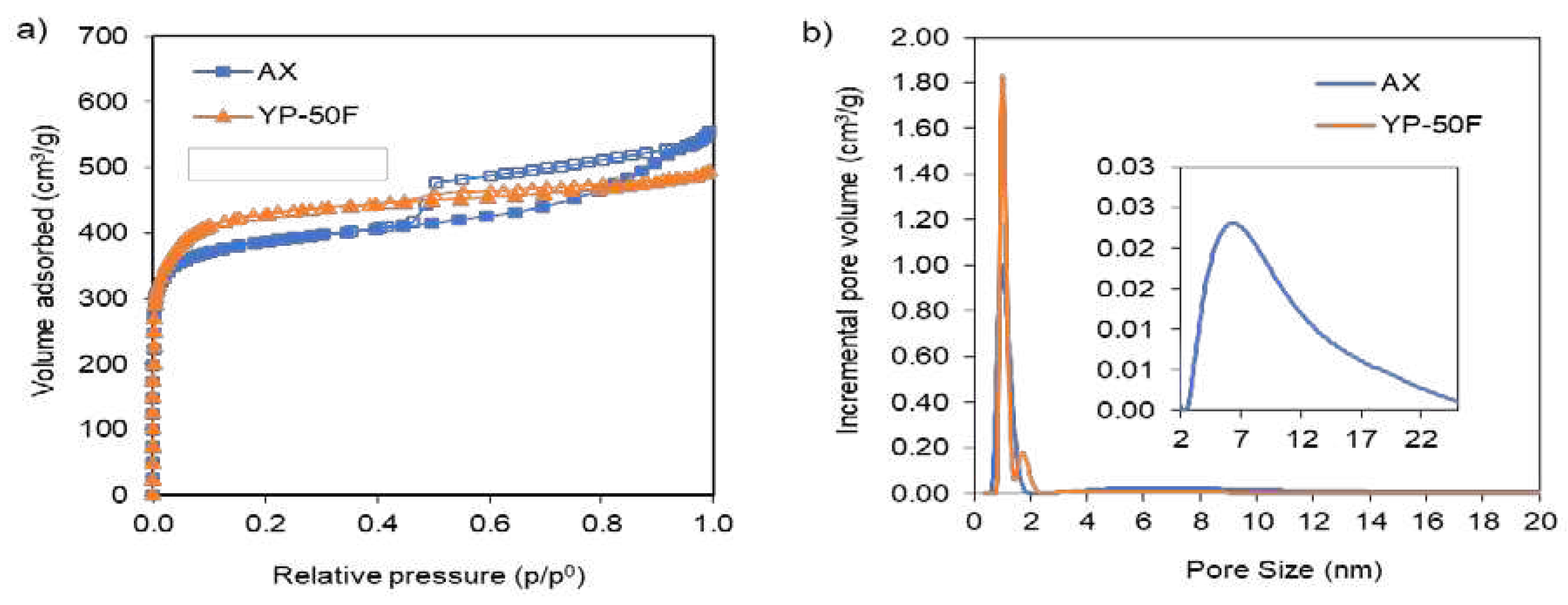

2.1. Physical Chemical and Morphological Characterizations of Carbons

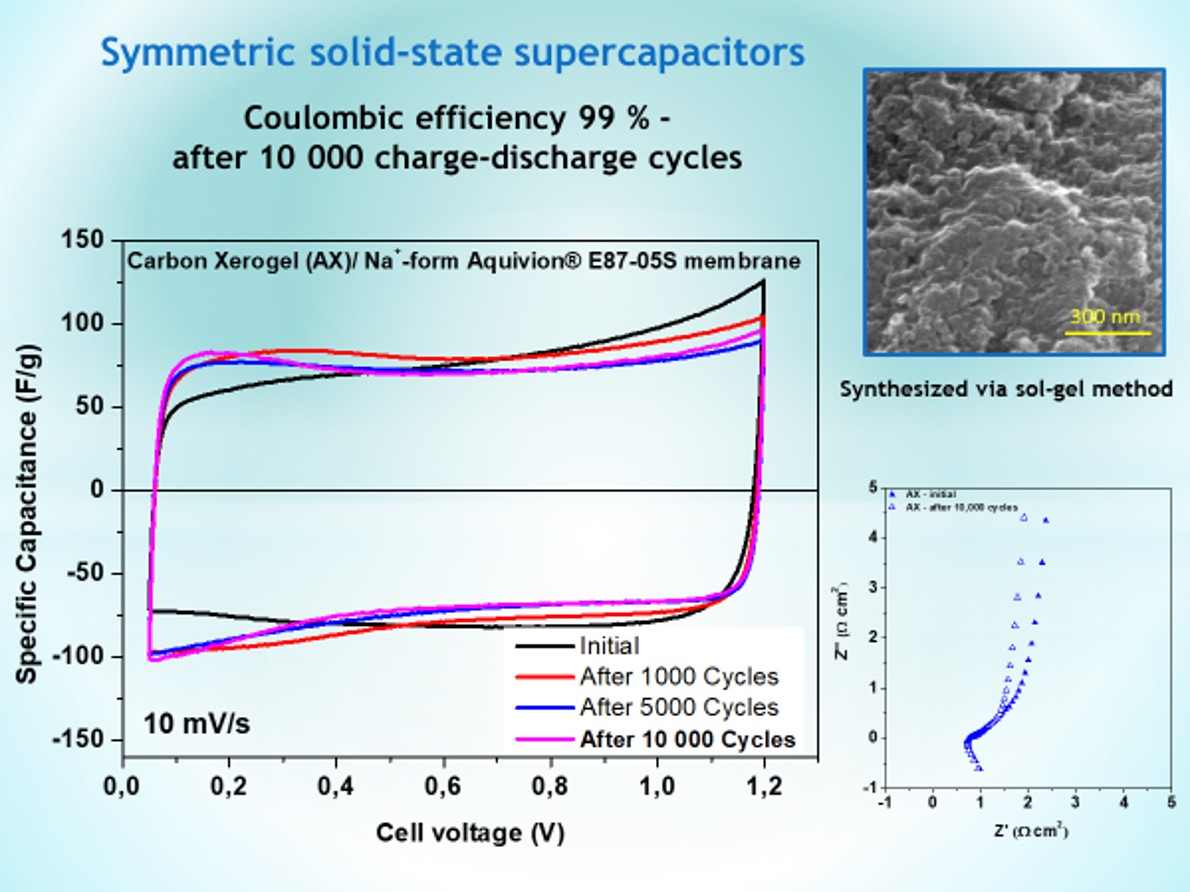

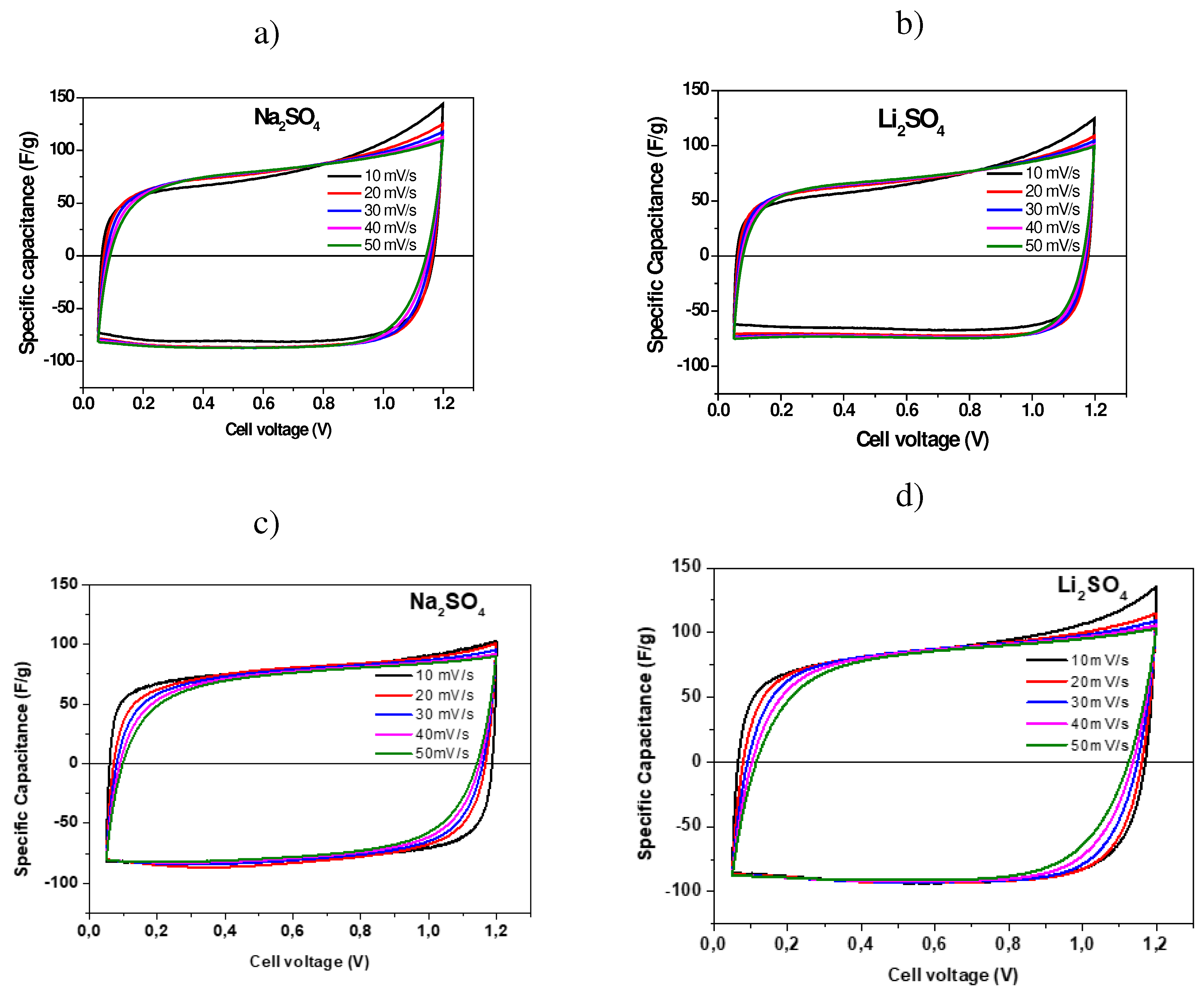

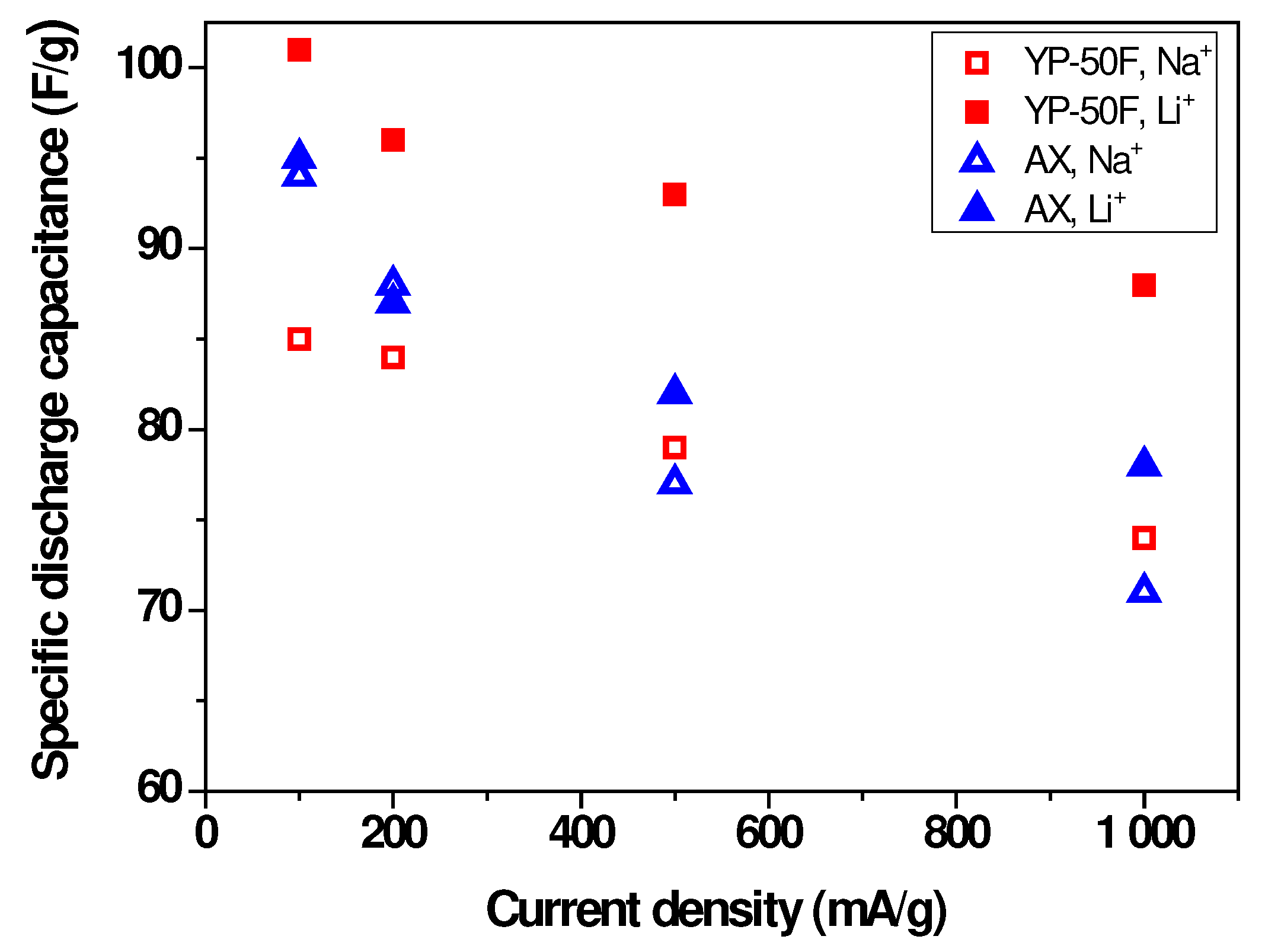

2.2. Electrochemical Characterization of Symmetric Supercapacitors

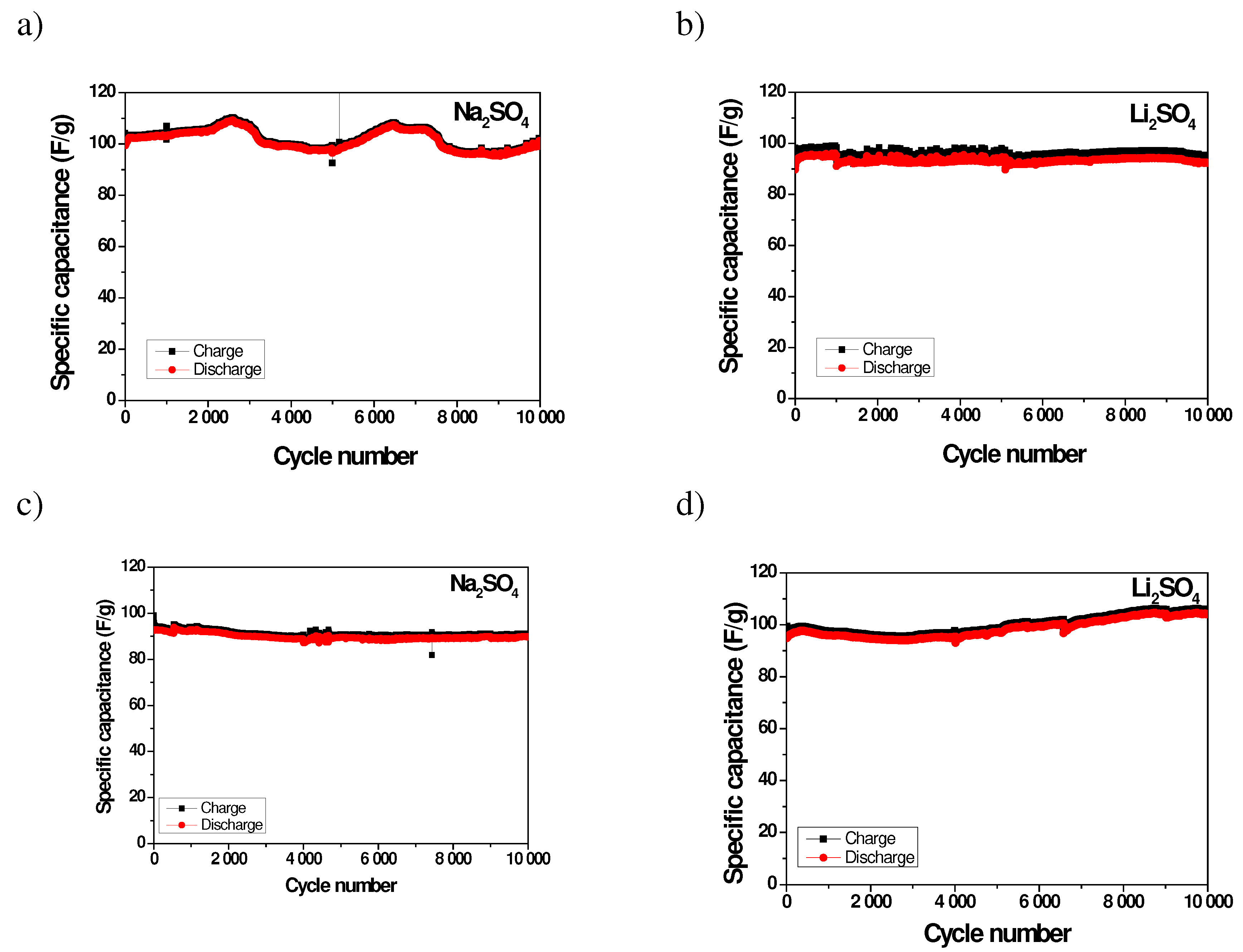

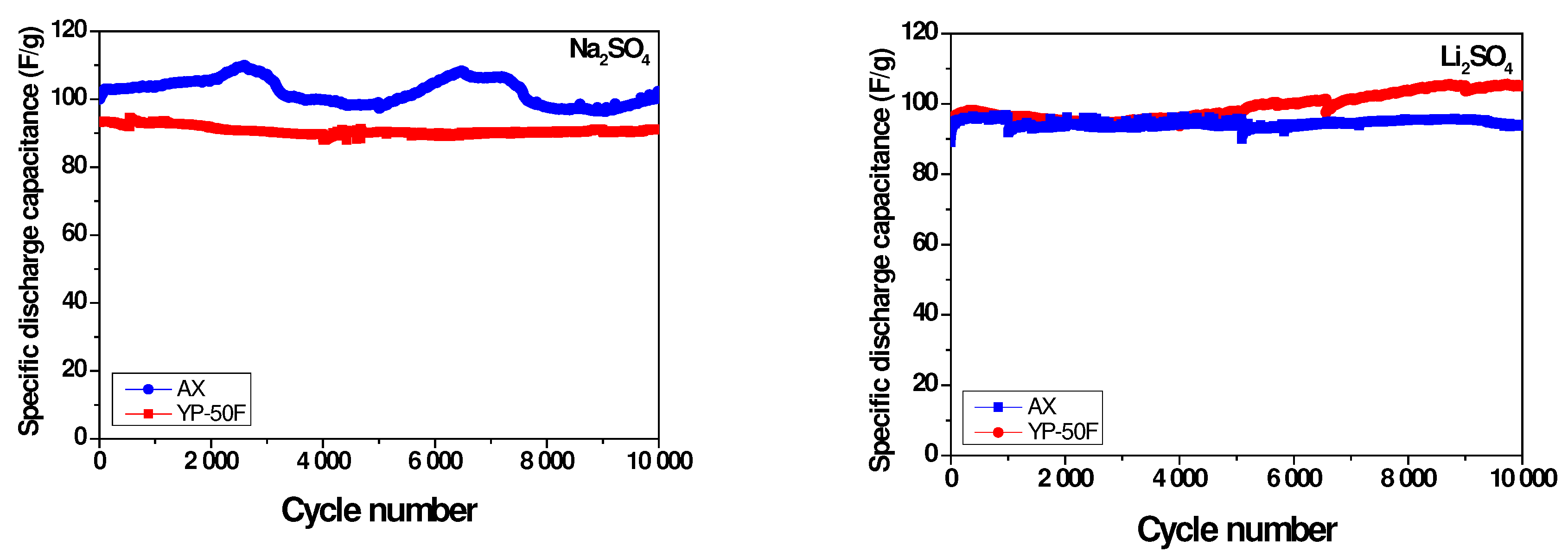

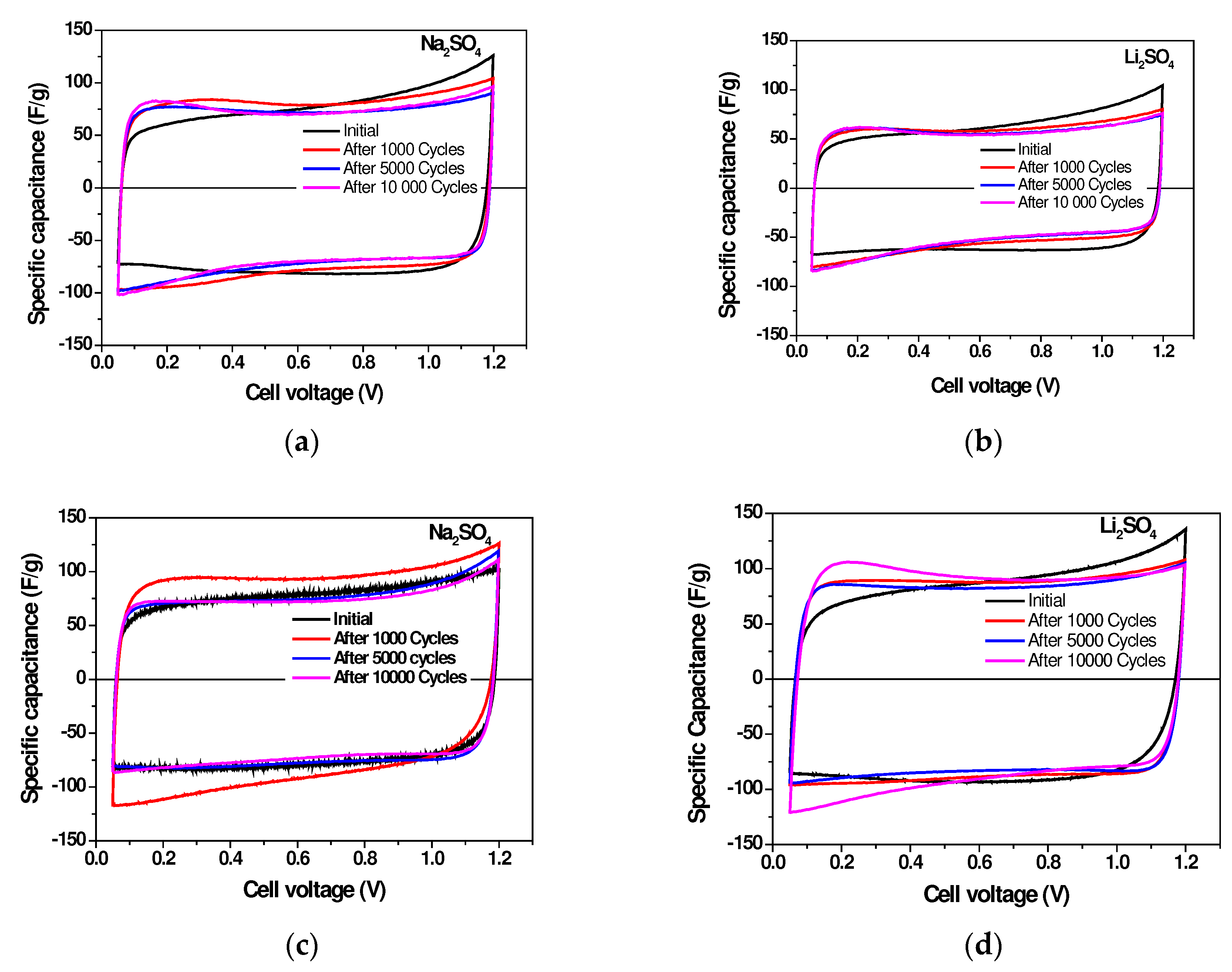

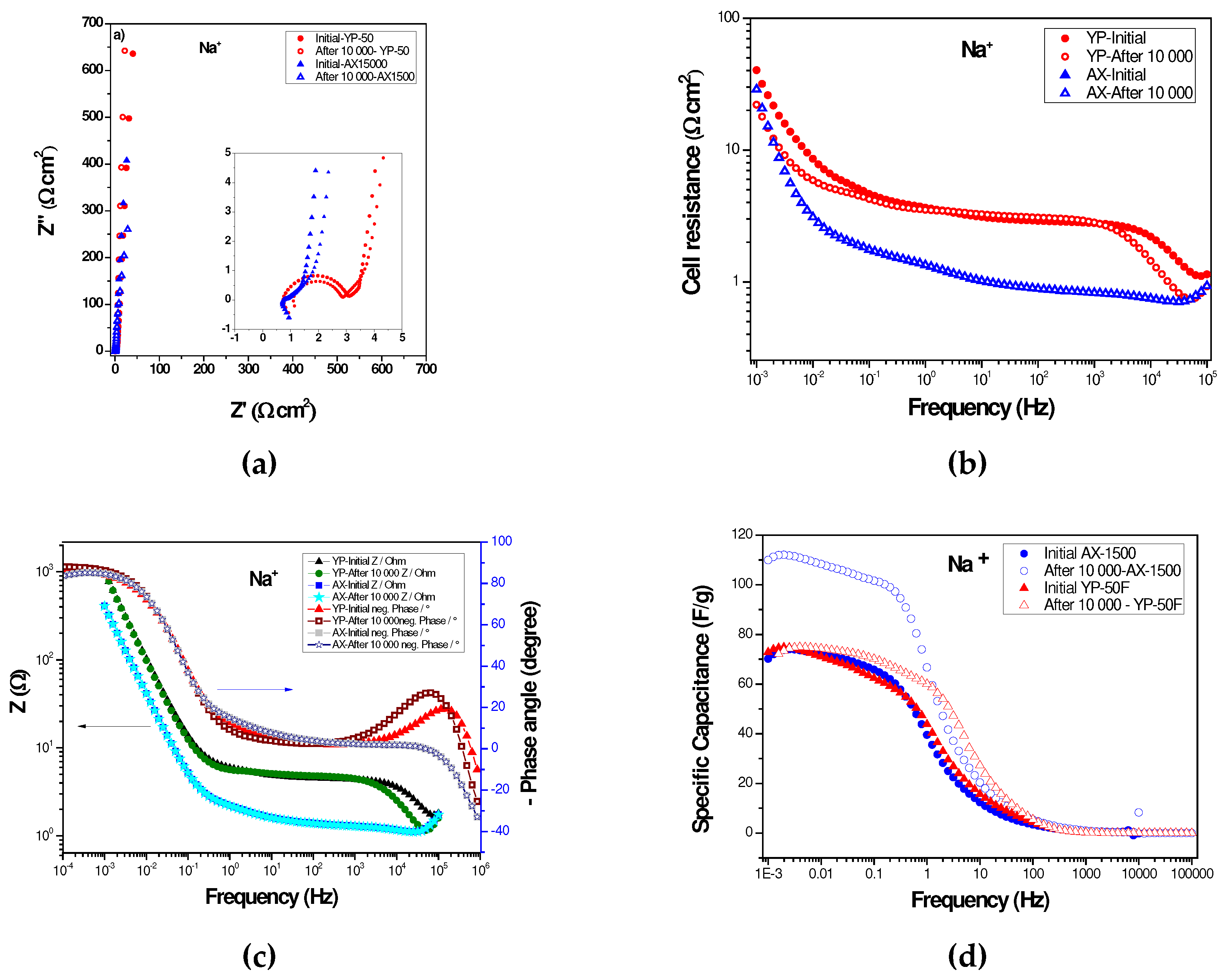

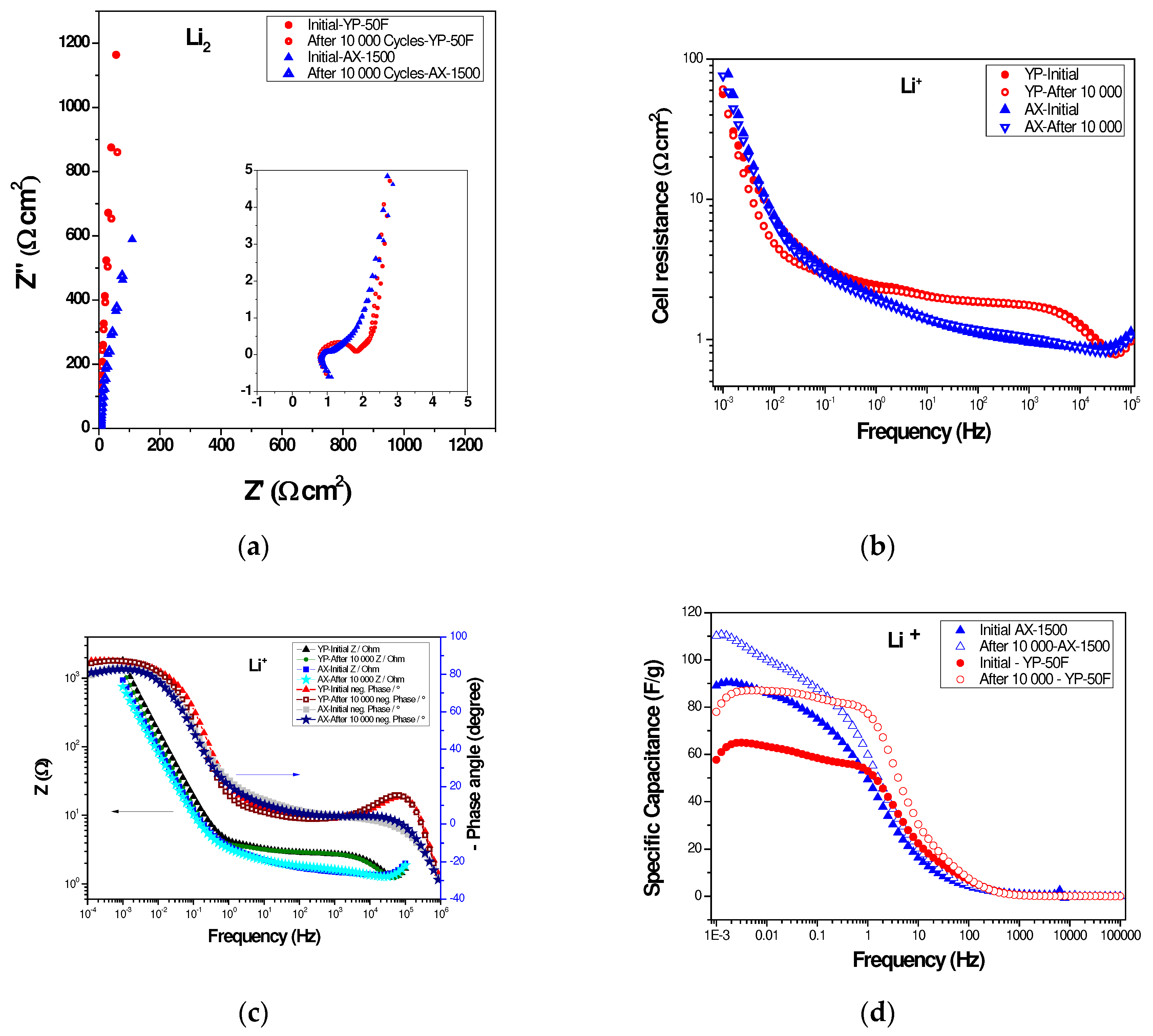

2.3. Long-Term Durability of Investigated Supercapacitors

3. Conclusions

4. Experimental

4.1. Synthesis of Carbon Xerogels

4.2. Physicochemical Characterization of Carbon Xerogels

4.3. Preparation of the Carbon Xerogel Electrodes

4.4. Activation of the Polymer Electrolyte Membrane and Electrochemical Characterization

Acknowledgments

References

- M. M. Pérez-Madrigal, F. Estrany, E. Armelin, D. D. Díaz, and C. Alemán, “Towards sustainable solid-state supercapacitors: electroactive conducting polymers combined with biohydrogels,” J. Mater. Chem. A, vol. 4, no. 5, pp. 1792–1805, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. T. Senthilkumar, Y. Wang, and H. Huang, “Advances and prospects of fiber supercapacitors,” J. Mater. Chem. A, vol. 3, no. 42, pp. 20863–20879, 2015. [CrossRef]

- W. Li, H. Lu, N. Zhang, and M. Ma, “Enhancing the Properties of Conductive Polymer Hydrogels by Freeze–Thaw Cycles for High-Performance Flexible Supercapacitors,” ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 9, no. 23, pp. 20142–20149, Jun. 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhu, K. Uetani, M. Nogi, and H. Koga, “Polydopamine Doping and Pyrolysis of Cellulose Nanofiber Paper for Fabrication of Three-Dimensional Nanocarbon with Improved Yield and Capacitive Performances,” Nanomaterials, vol. 11, no. 12, p. 3249, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. R. Palem et al., “Nanostructured Fe2O3@nitrogen-doped multiwalled nanotube/cellulose nanocrystal composite material electrodes for high-performance supercapacitor applications,” J. Mater. Res. Technol., vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 7615–7627, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Song, H. Tan, and Y. Zhao, “Carbon fiber-bridged polyaniline/graphene paper electrode for a highly foldable all-solid-state supercapacitor,” J. Solid State Electrochem., vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 9–17, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. G. Calvo, C. O. Ania, L. Zubizarreta, J. A. Menéndez, and A. Arenillas, “Exploring New Routes in the Synthesis of Carbon Xerogels for Their Application in Electric Double-Layer Capacitors,” Energy & Fuels, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 3334–3339, Jun. 2010. [CrossRef]

- K. Kraiwattanawong, H. Tamon, P. Praserthdam, “Influence of solvent species used in solvent exchange for preparation of mesoporous carbon xerogels from resorcinol and formaldehyde via subcritical drying,” Microporous Mesoporous Mater., vol. 138, pp. 8–16, 2011. [CrossRef]

- M. M. L. R. C. F.L. Conçenciao, P.J.M. Carrott, “New carbon materials with high porosity in the 1–7 nm range obtained by chemical activation with phosphoric acid of resorcinol–formaldehyde aerogels,” Carbon N. Y., vol. 47, pp. 1874–1877, 2009. [CrossRef]

- N. J. L. Zubizarreta, A. Arenillas, J.-P. Pirard, J.J. Pis, “Tailoring the textural properties of activated carbon xerogels by chemical activation with KOH,” Microporous Mesoporous Mater, vol. 115, pp. 480–490, 2008. [CrossRef]

- A. L.-S. J.A. Maciá-Agulló, B.C. Moore, D. Cazorla-Amorós, “Influence of carbon fibres crystallinities on their chemical activation by KOH and NaOH,” Microporous Mesoporous Mater., vol. 101, pp. 397–405, 2007. [CrossRef]

- O. Glukhova, “Flexible Membranes for Batteries and Supercapacitor Applications,” Membranes (Basel)., vol. 12, no. 6, p. 583, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu and G. Zhu, “The electrochemical capacitance of nanoporous carbons in aqueous and ionic liquids,” J. Power Sources, vol. 171, no. 2, pp. 1054–1061, Sep. 2007. [CrossRef]

- B. Xu et al., “Room temperature molten salt as electrolyte for carbon nanotube-based electric double layer capacitors,” J. Power Sources, vol. 158, no. 1, pp. 773–778, Jul. 2006. [CrossRef]

- P. Liu, M. Verbrugge, and S. Soukiazian, “Influence of temperature and electrolyte on the performance of activated-carbon supercapacitors,” J. Power Sources, vol. 156, no. 2, pp. 712–718, Jun. 2006. [CrossRef]

- S. Maitra, R. Mitra, and T. K. Nath, “Investigation of electrochemical performance of MgNiO2 prepared by sol-gel synthesis route for aqueous-based supercapacitor application,” Curr. Appl. Phys., vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 628–637, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang et al., “Pomelo peels-derived porous activated carbon microsheets dual-doped with nitrogen and phosphorus for high performance electrochemical capacitors,” J. Power Sources, vol. 378, pp. 499–510, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Fic, G. Lota, M. Meller, and E. Frackowiak, “Novel insight into neutral medium as electrolyte for high-voltage supercapacitors,” Energy Environ. Sci., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 5842–5850, 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Hughes, J. A. Allen, and S. W. Donne, “Optimized Electrolytic Carbon and Electrolyte Systems for Electrochemical Capacitors,” ChemElectroChem, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 266–282, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Karade, S. S. Raut, H. B. Gajare, P. R. Nikam, R. Sharma, and B. R. Sankapal, “Widening potential window of flexible solid-state supercapacitor through asymmetric configured iron oxide and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate coated multi-walled carbon nanotubes assembly,” J. Energy Storage, vol. 31, p. 101622, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Platek-Mielczarek, J. Piwek, E. Frackowiak, and K. Fic, “Ambiguous Role of Cations in the Long-Term Performance of Electrochemical Capacitors with Aqueous Electrolytes,” ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 15, no. 19, pp. 23860–23874, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Rey-Raap, J. Angel Menéndez, and A. Arenillas, “RF xerogels with tailored porosity over the entire nanoscale,” Microporous Mesoporous Mater., vol. 195, pp. 266–275, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Sahoo and G. R. Rao, “A high energy flexible symmetric supercapacitor fabricated using N-doped activated carbon derived from palm flowers,” Nanoscale Adv., vol. 3, no. 18, pp. 5417–5429, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, J. Liu, K. Zhang, H. Peng, and G. Li, “Meso/microporous nitrogen-containing carbon nanofibers with enhanced electrochemical capacitance performances,” Synth. Met., vol. 203, pp. 149–155, 15. [CrossRef]

- B. Karamanova, A. Stoyanova, M. Shipochka, S. Veleva, and R. Stoyanova, “Effect of Alkaline-Basic Electrolytes on the Capacitance Performance of Biomass-Derived Carbonaceous Materials,” Materials (Basel)., vol. 13, no. 13, p. 2941, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Yan, M. Antonietti, and M. Oschatz, “Toward the Experimental Understanding of the Energy Storage Mechanism and Ion Dynamics in Ionic Liquid Based Supercapacitors,” Adv. Energy Mater., vol. 8, no. 18, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhao, Z. Song, L. Qing, J. Zhou, and C. Qiao, “Surface Wettability Effect on Energy Density and Power Density of Supercapacitors,” J. Phys. Chem. C, vol. 126, no. 22, pp. 9248–9256, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Primachenko et al., “New Generation of Compositional Aquivion®-Type Membranes with Nanodiamonds for Hydrogen Fuel Cells: Design and Performance,” Membranes (Basel)., vol. 12, no. 9, p. 827, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Y. Safronova, A. K. Osipov, and A. B. Yaroslavtsev, “Short Side Chain Aquivion Perfluorinated Sulfonated Proton-Conductive Membranes: Transport and Mechanical Properties,” Pet. Chem., vol. 58, no. 2, pp. 130, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. S. Mathis, N. Kurra, X. Wang, D. Pinto, P. Simon, and Y. Gogotsi, “Energy Storage Data Reporting in Perspective—Guidelines for Interpreting the Performance of Electrochemical Energy Storage Systems,” Adv. Energy Mater., vol. 9, no. 39, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Wu, C. Hsu, Chi-Chang Hu, L. Hardwick, “Important parameters affecting the cell voltage of aqueous electrical double-layer capacitors”, J. Power Sources, vol. 242, Nov. 2013, p. 289 - 298. [CrossRef]

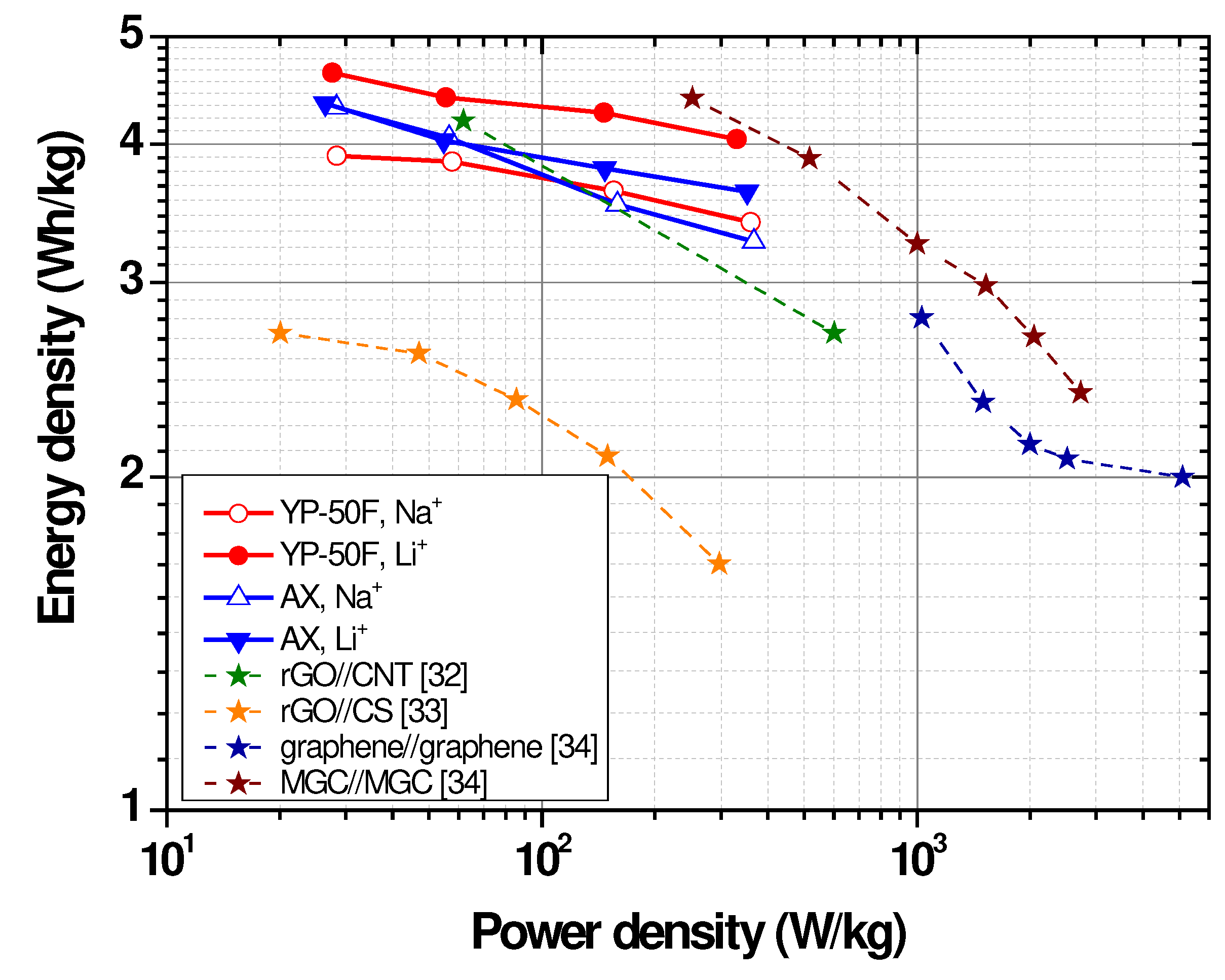

- O. Okhay, A. Tkach, P. Staiti, F. Lufrano, “Long term durability of solid-state supercapacitor based on reduced graphene oxide aerogel and carbon nanotubes composite electrodes”, Electrochim. Acta, vol. 353, no.1, 136540, Sept. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Boota, K.B. Hatzell, M. Alhabeb, E.C. Kumbur, Y. Gogotsi, “Graphene-containing flowable electrodes for capacitive energy storage”, Carbon, vol. 92, pp. 142 - 149, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wu, W. Ren, Da-Wei Wang, F. Li, B. Liu, Hui-Ming Cheng, “High-Energy MnO2 Nanowire/ Graphene and Graphene Asymmetric Electrochemical Capacitors”, ACS Nano, vol., 4, no.10, p. 5835, Sept. 2010. [CrossRef]

- H. Kim, V. Guccini, H. Lu, G. Salazar-Alvarez, G. Lindbergh, and A. Cornell, “Lithium Ion Battery Separators Based On Carboxylated Cellulose Nanofibers From Wood”, ACS Appl. Energy Mater., vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 1241–1250, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Canal-Rodríguez et al., “Multiphase graphitisation of carbon xerogels and its dependence on their pore size,” Carbon N. Y., vol. 152, pp. 704–714, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

| Sample | C (wt%) | H (wt%) | O (wt%) | N (wt%) | S (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| АХ | 96.3 | 0.7 | 3.0 | - | - |

| YP-50F | 97.6 | 0.3 | 2.1 | - | - |

| Sample | SBET, m2g-1 | Sext, m2g-1 | Vmicro, сm3g-1 | Vt, сm3g-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| АX | 1492 | 234 | 0.59 | 0.85 |

| YP-50F | 1756 | 157 | 0.62 | 0.80 |

| Coulombic efficiency, % | 1st cycle | after 1 000 cycles | after 5 000 cycles | after 10 000 cycles | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na2SO4 | Li2SO4 | Na2SO4 | Li2SO4 | Na2SO4 | Li2SO4 | Na2SO4 | Li2SO4 | |

| AX | 96 | 82 | 99 | 97 | 99 | 97 | 99 | 97 |

| YP-50F | 94 | 95 | 99 | 98 | 99 | 98 | 99 | 98 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).