Submitted:

22 November 2023

Posted:

23 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Analysis on mobility behavior and demand pattern of MaaS end-users

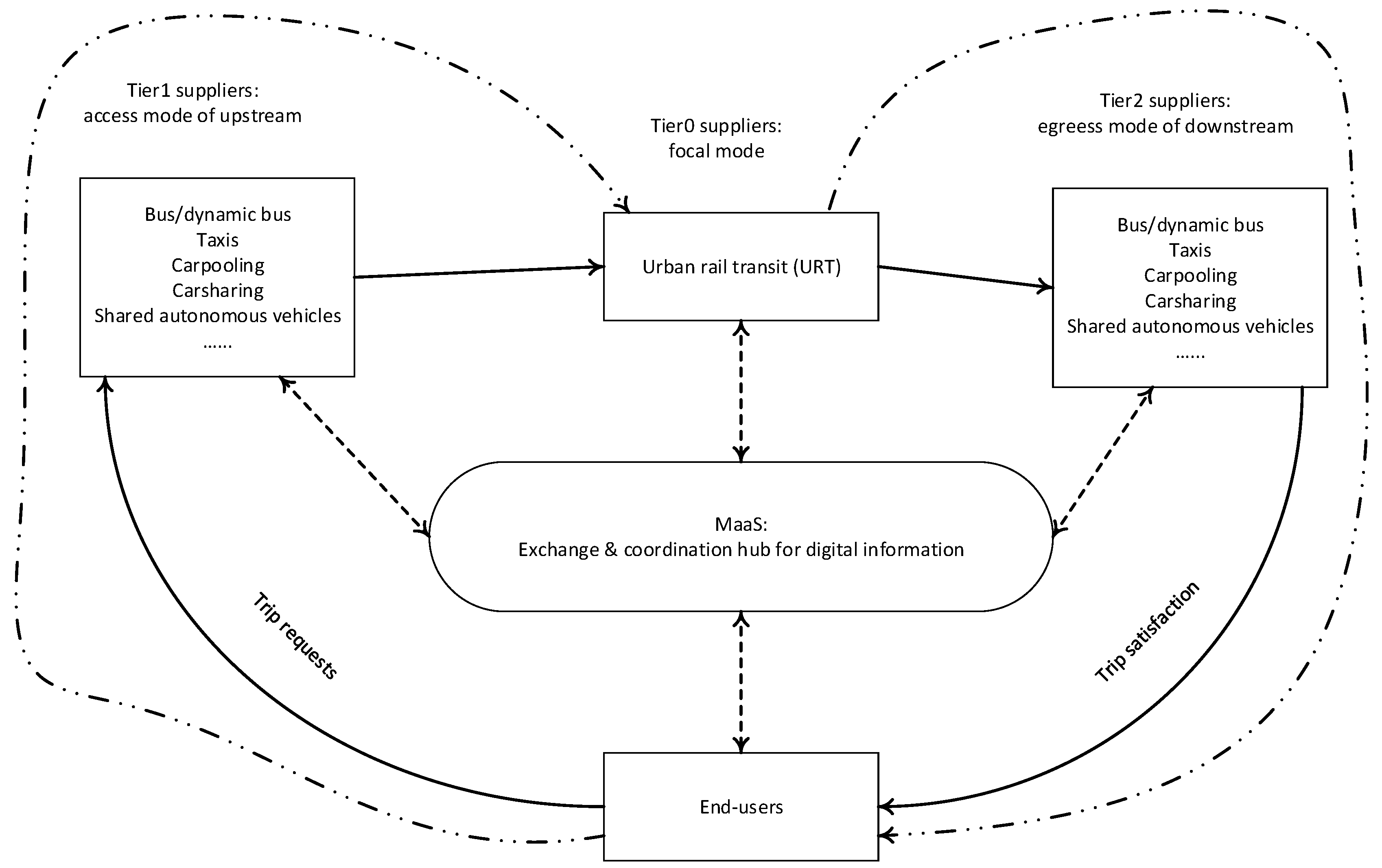

3. Interpretation of intelligent mobility service supply chain network in the context of MaaS

3.1. Mobility service taxonomy of MaaS and aims of intelligent mobility service supply chain network

3.1.1. Mobility service taxonomy of MaaS

3.1.2. Aims of intelligent mobility service supply chain network

- (i)

- Travelers’ rides demand includes pickup and drop-off locations, which is requested via a mobile application.

- (ii)

- Travelers want to be served, i.e. pick up, as soon as possible or within a time window.

- (iii)

- There are always complete service solutions for the travelers’ requests, i.e., travelers will always be served as long as they are willing to select one solution from the alternatives.

- (iv)

- There may be more than one mode or company, i.e., hybrid multi-modal stakeholders, involved in the service solutions or service supply chains provided for the traveler’s journey.

3.2. Journey alternatives and node member imperatives in intelligent mobility service supply chain network

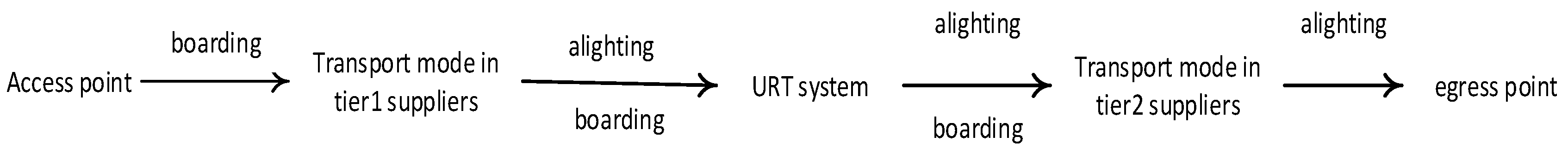

3.2.1. Urban rail transit (URT)-centered alternatives for integrated multimodal journey

3.2.2. Node member imperatives

- (i)

- Focus on multi-modal transport and collaboration with new digital integrators, understand and seek desired position in emerging intelligent mobility ecosystems.

- (ii)

- Collaborate across the industry, by opening data and creating seamless end-to-end journeys (focus on ticketing, pricing, integrated information, commercial models).

- (iii)

- Actively participate and collaborate with digital start-ups, not least by opening up commercially non-sensitive data and start generating real-time data where missing (and consider how to monetise valuable data).

- (iv)

- Reduce complexity of planning by increasing availability of information (in particular expected arrival time, expected level of personal space) and include every element of the journey (car parking, etc.)

- (i)

- Focus on traveller experience on multi-modal journeys, in particular integration of ‘new’ on-demand modes (bike share, car share, taxi apps, autonomous mobility) and speed & reliability of interchange.

- (ii)

- Focus on enabling productive time: connectivity, seamless interchange.

- (iii)

- Focus on dynamic train capacity supply: flexible coupling and decoupling with virtual coupling technique, dynamic timetabling.

- (iv)

- Focus on accessibility of rail: ‘easy to get to’ / first & last mile, 24-hour daily service with fully automated operation (FAO) technique.

- (v)

- Enable digital lifestyles (e.g. journey experience personalisation) and engage travellers with transport choices.

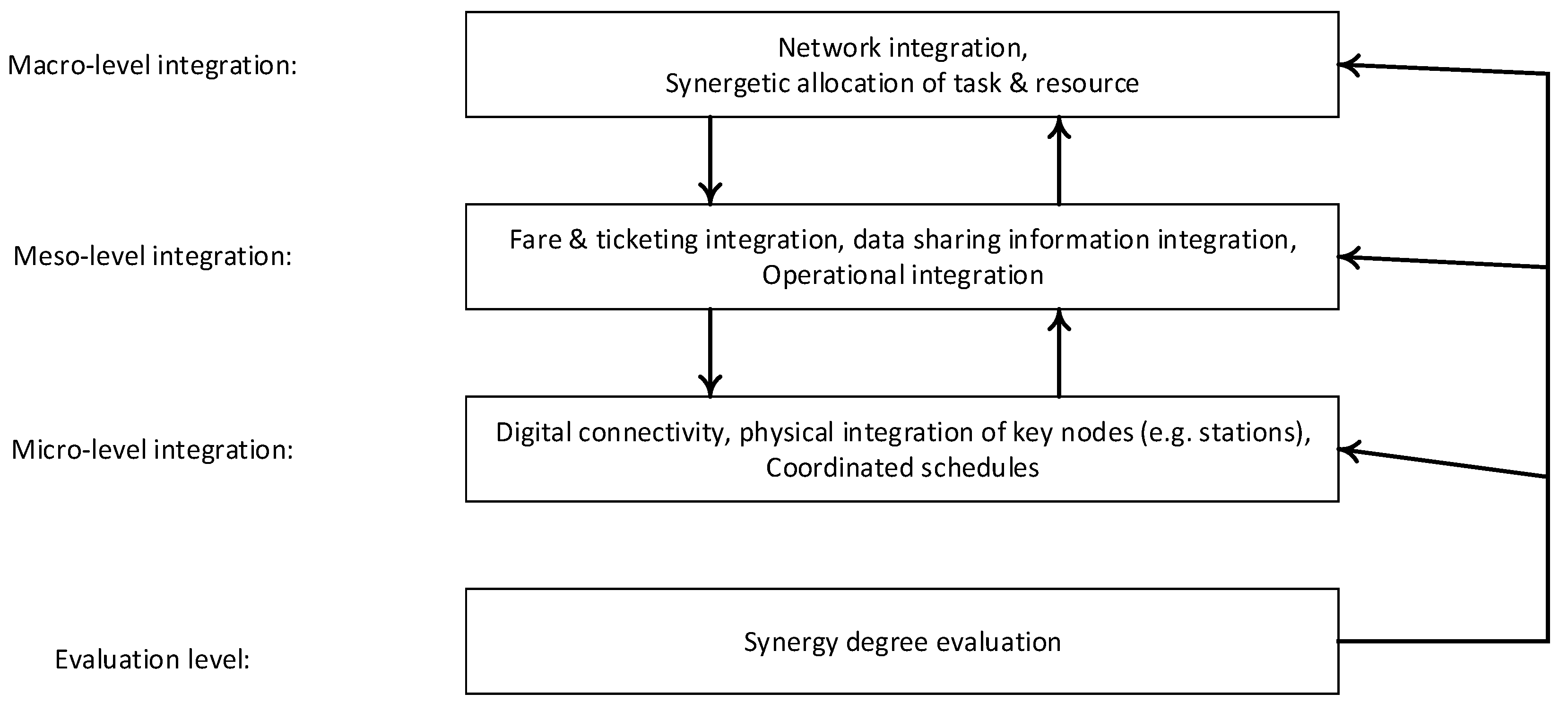

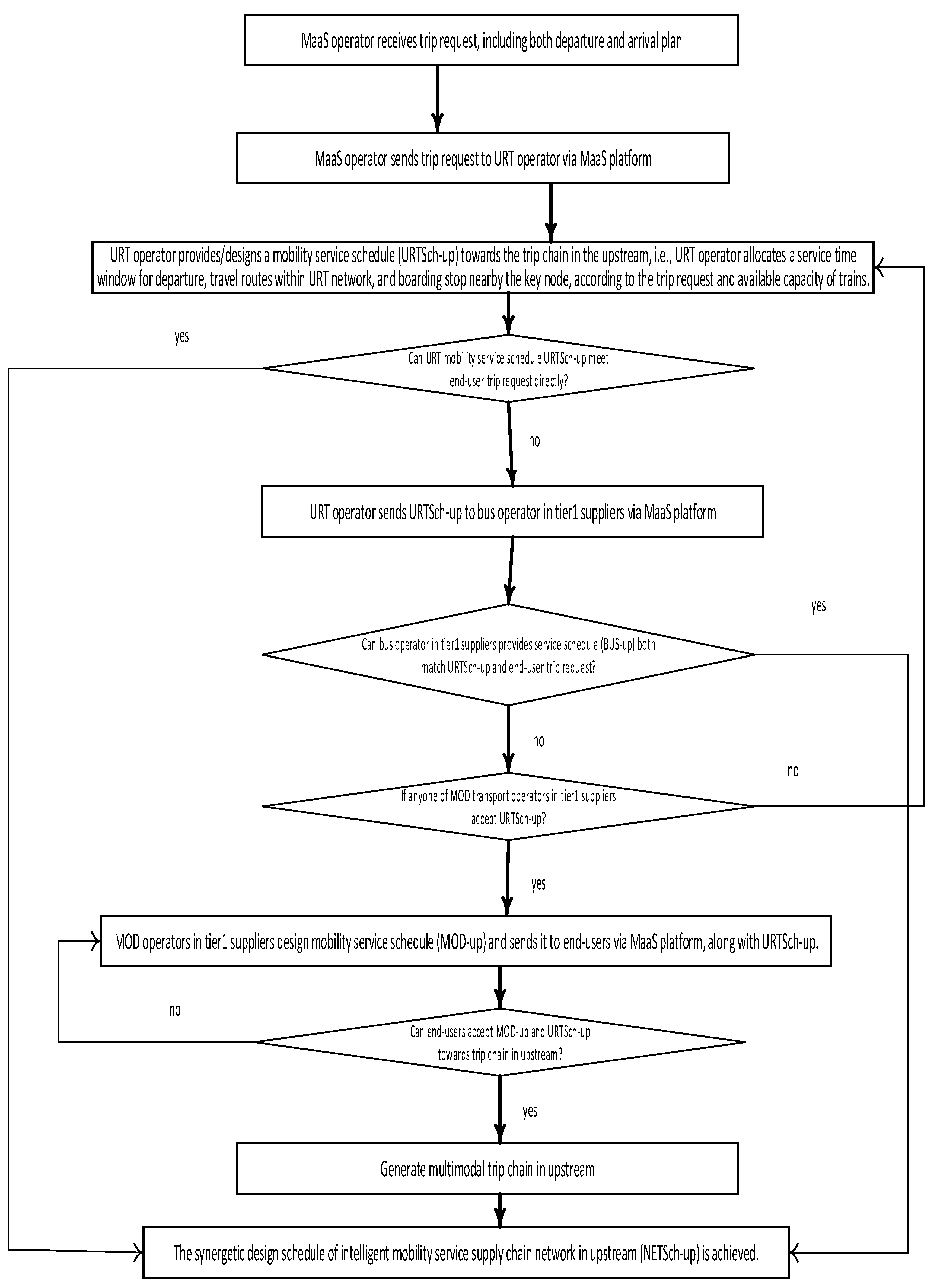

4. Methods on synergetic design of intelligent mobility service supply chain network

4.1. Multi-tier closed-loop structure of the intelligent mobility service supply chain network

4.2. Key nodes identification for the physical multimodal transport network

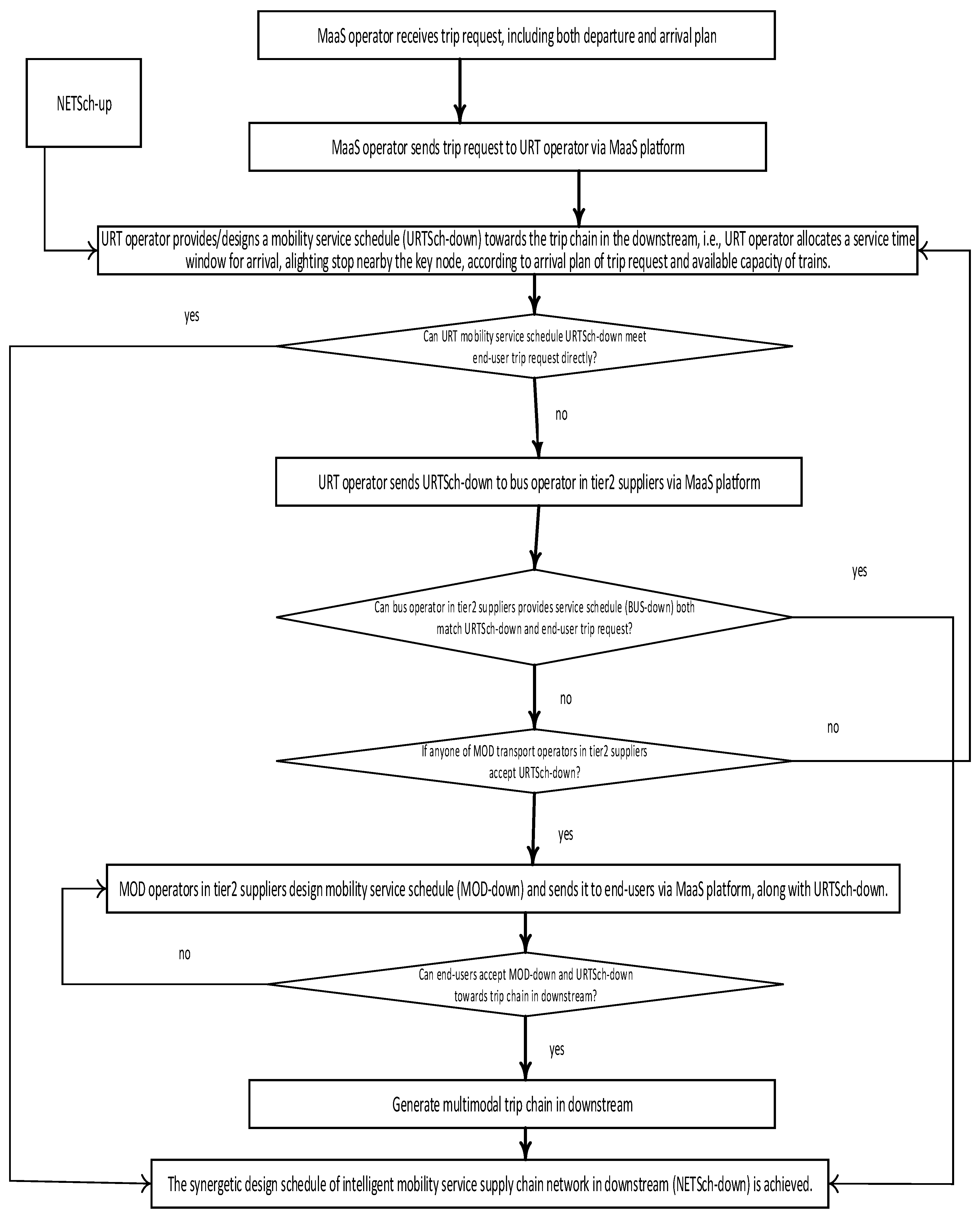

4.3. Hybrid synergy mechanisms among the partners of the intelligent mobility service supply chain network

4.3.1. Synergy principle

4.3.2. Temporal splitting approach for coopetition synergy

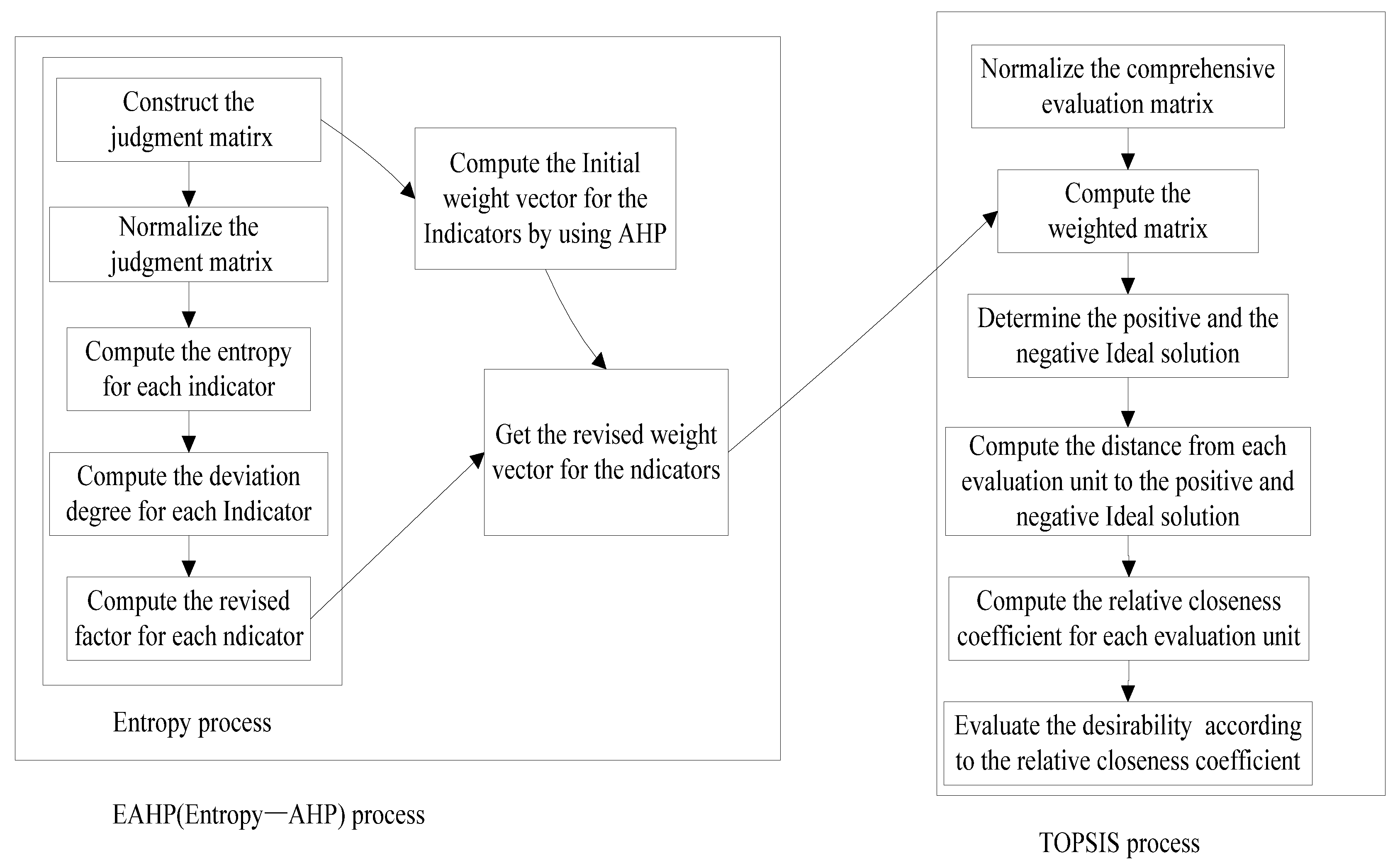

5. Discussion on synergy measurement with multiple criteria

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kamargianni, M., Matyas, M., Li, W., Muscat, K., and Yfantis, L. 2018. The MaaS Dictionary. London: MaaSLab, Energy Institute, University College London.

- Barreto, L., Amaral, A., & Baltazar, S., 2018. Urban mobility digitalization: towards mobility as a service (MaaS). In 2018 International Conference on Intelligent Systems (IS), 850-855. [CrossRef]

- Kummitha, R. K. R. and Crutzen, N., 2017. How do we understand smart cities? An evolutionary perspective. Cities, 67, 43–52. [CrossRef]

- 4. Transport System Catapult, 2015. Intelligent mobility: Travellers Needs and UK Capability Study—Supporting the realization of Intelligent Mobility in the UK. London, UK. Report.

- Kamargianni, M., Li, W., Matyas, M., & Schäfer, A., 2016. A critical review of new mobility services for urban transport. Transportation Research Procedia, 14, 3294-3303. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., & Zhao, J., 2018. Mobility sharing as a preference matching problem. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 20(7), 2584-2592.

- Lyons, G., Hammond, P., & Mackay, K., 2019. The importance of user perspective in the evolution of MaaS. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 121, 22-36. [CrossRef]

- Kamargianni, M., Matyas, M., Li, W., and Schafer, A., 2015. Feasibility Study for “Mobility as a Service” concept in London. Report – UCL Energy Institute and Department for Transport.

- Matyas, M. B., 2020. Investigating individual preferences for new mobility services: the case of “mobility as a service” products. Doctoral dissertation, UCL (University College London).

- Croom, S., Romano, P., Giannakis, M., 2000. Supply chain management: An analytical framework for critical literature review. European Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 6 (1), 67–83. [CrossRef]

- Giesecke, R., Surakka, T., & Hakonen, M., 2016. Conceptualising mobility as a service. In 2016 Eleventh International Conference on Ecological Vehicles and Renewable Energies (EVER), 1-11.

- Wong, Y. Z., Hensher, D. A., & Mulley, C., 2020. Mobility as a service (MaaS): Charting a future context. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 131, 5-19). [CrossRef]

- Fioreze, T., de Gruijter, M., & Geurs, K., 2019. On the likelihood of using Mobility-as-a-Service: A case study on innovative mobility services among residents in the Netherlands. Case Studies on Transport Policy, 7(4), 790–801. [CrossRef]

- Nikitas, A., Michalakopoulou, K., Njoya, E. T., & Karampatzakis, D., 2020. Artificial intelligence, transport and the smart city: Definitions and dimensions of a New Mobility Era. Sustainability, 12(7), 2789. [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, G., Araldo, A., Oh, S., Seshadri, R., Inturri, G., & Ben-Akiva, M., 2021. Integrating fixed and demand-responsive transportation for flexible transit network design. In TRB 2021: 100th Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board.

- Pickford, A., & Chung, E., 2019. The shape of MaaS: the potential for MaaS Lite. IATSS research, 43(4), 219-225. [CrossRef]

- Recker, W. W., McNally, M. G., & Root, G. S., 1986. A model of complex travel behavior: Part I—Theoretical development. Transportation Research Part A: General, 20(4), 307-318. [CrossRef]

- Cantelmo, G., Qurashi, M., Prakash, A. A., Antoniou, C., & Viti, F., 2019. Incorporating trip chaining within online demand estimation. Transportation Research Procedia, 38, 462-481. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M. A. G., 2019. Growing Artificial Societies to Support Demand Modelling in Mobility-as-a-Service Solutions, Master thesis, U. Porto.

- Xia, F., Wang, J., Kong, X., Wang, Z., Li, J., & Liu, C., 2018. Exploring human mobility patterns in urban scenarios: A trajectory data perspective. IEEE Communications Magazine, 56(3), 142-149. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, A., Winslott Hiselius, L., Berg, J., Forward, S., & Arnfalk, P., 2020. Evaluating a mobility service application for business travel: lessons learnt from a demonstration project. Sustainability, 12(3), 783. [CrossRef]

- Schikofsky, J., Dannewald, T., & Kowald, M., 2020. Exploring motivational mechanisms behind the intention to adopt mobility as a service (MaaS): Insights from Germany. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 131, 296-312. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S., Hadas, Y., Gonzalez, V. A. and Schot, B., 2018. Public transport users’ and policy makers’ perceptions of integrated public transport systems, Transport Policy, 61,75–83. [CrossRef]

- Hensher, D.A., 2017. Future bus transport contracts under a mobility as a service (MaaS) regime in the digital age: Are they likely to change? Transp. Res. Part A: Policy Pract. 98, 86–96.

- Alyavina, E., Nikitas, A., & Njoya, E. T., 2020. Mobility as a service and sustainable travel behaviour: A thematic analysis study. Transportation research part F: traffic psychology and behaviour, 73, 362-381. [CrossRef]

- Nuzzolo, A., Crisalli, U., & Rosati, L., 2012. A schedule-based assignment model with explicit capacity constraints for congested transit networks. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 20(1), 16–33. [CrossRef]

- Ansari Esfeh, M., Wirasinghe, S. C., Saidi, S., & Kattan, L., 2020. Waiting time and headway modelling for urban transit systems–a critical review and proposed approach. Transport Reviews, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Reck, D. J., Hensher, D. A., & Ho, C. Q., 2020. MaaS bundle design. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 141, 485-501.

- Yu, J., & Hyland, M. F., 2020. A generalized diffusion model for preference and response time: Application to ordering mobility-on-demand services. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 121, 102854. [CrossRef]

- Smith, G., Sochor, J., & Karlsson, I. M., 2018. Mobility as a Service: Development scenarios and implications for public transport. Research in Transportation Economics, 69, 592-599. [CrossRef]

- Najmi, A., Duell, M., Ghasri, M., Rashidi, T.H., Waller, S.T., 2018. How Should Travel Demand and Supply Models Be Jointly Calibrated? Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board.

- Najmi, A., Rashidi, T.H., Miller, E.J., 2019. A novel approach for systematically calibrating transport planning model systems. Transportation (Amst). 46, 1915–1950. [CrossRef]

- Najmi, A., Rashidi, T. H., & Liu, W., 2020. Ridesharing in the era of Mobility as a Service (MaaS): An Activity-based Approach with Multimodality and Intermodality. arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.11712.

- Polydoropoulou, A., Pagoni, I., Tsirimpa, A., Roumboutsos, A., Kamargianni, M., & Tsouros, I., 2020. Prototype business models for Mobility-as-a-Service. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 131, 149-162. [CrossRef]

- Stockheim, T., Schwind, M., & Koenig, W., 2003. A reinforcement learning approach for supply chain management. In 1st European Workshop on Multi-Agent Systems, Oxford, UK.

- König, D., Eckhardt, J., Aapaoja, A., Sochor, J., and Karlsson, M., 2016. Deliverable 3: Business and operator models for MaaS. MAASiFiE project funded by CEDR. Conference of European Directors of Roads., (3):1–71.

- Hyland, M., & Mahmassani, H. S., 2018. Dynamic autonomous vehicle fleet operations: Optimization-based strategies to assign AVs to immediate traveler demand requests. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 92, 278-297. [CrossRef]

- Chia, J., Lee, J. B., & Han, H., 2020. How Does the Location of Transfer Affect Travellers and Their Choice of Travel Mode?—A Smart Spatial Analysis Approach. Sensors, 20(16), 4418. [CrossRef]

- Yap, M. D., Correia, G., & Van Arem, B., 2016. Preferences of travellers for using automated vehicles as last mile public transport of multimodal train trips. Transportation research part a: policy and practice, 94, 1-16.

- Chow, J. Y., 2018. Informed Urban Transport Systems: Classic and Emerging Mobility Methods toward Smart Cities. Elsevier.

- Erhardt, G. D., Roy, S., Cooper, D., Sana, B., Chen, M., & Castiglione, J., 2019. Do transportation network companies decrease or increase congestion?. Science advances, 5(5), eaau2670. [CrossRef]

- Walley, K., 2007. Coopetition: an introduction to the subject and an agenda for research. International Studies of Management & Organization, 37(2), 11-31. [CrossRef]

- Marcelli, M., & Pellegrini, P., 2018. Literature review toward decentralized railway traffic management. Institut Français des Sciences et Technologies des Transports, l’Aménagement et des Réseaux (IFSTTAR).

- Zubin, I., van Oort, N., van Binsbergen, A., & van Arem, B., 2020. Adoption of Shared Automated Vehicles as Access and Egress Mode of Public Transport: A Research Agenda. In 2020 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), 1-6.

- Quaglietta, E., Wang, M., & Goverde, R. M., 2020. A multi-state train-following model for the analysis of virtual coupling railway operations. Journal of Rail Transport Planning & Management, 15, 100195. [CrossRef]

- Shi, X., Chen, Z., Pei, M., & Li, X., 2020. Variable-Capacity Operations with Modular Transits for Shared-Use Corridors. Transportation Research Record, 2674(9), 230-244. [CrossRef]

- Stiglic, M., Agatz, N., Savelsbergh, M., & Gradisar, M., 2015. The benefits of meeting points in ride-sharing systems. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, 82, 36-53. [CrossRef]

- Verma, A. and S. Dhingra, 2006. Developing integrated schedules for urban rail and feeder bus operation. Journal of urban planning and development, 132(3), 138–146. [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, M., Sydow, J., 2018. Managing coopetition in supplier networks–a paradox perspective. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 54(3), 22-41. [CrossRef]

- Choi, T. Y., Wu, Z., 2009. Triads in supply networks: Theorizing buyer-supplier-supplier relationships. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 45(1), 8–25. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, S., Wu, Z., & Johnston, D., 2014. Towards a theory of co-opetition of supply networks. Journal of Operations Management, 32(5), 254–267.

- He, Y., Csiszár, C., 2020. Quality Assessment Method for Mobility as a Service. Promet-Traffic & Transportation, 32(5), 611-624. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., & Zhang, J., 2021. Comprehensive Evaluation of Operating Speeds for High-Speed Railway: A Case Study of China High-Speed Railway. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2021, Article ID 8826193.

- Calabrò, G., Inturri, G., Le Pira, M., Pluchino, A., and Ignaccolo, M., 2020. Bridging the gap between weak-demand areas and public transport using an ant-colony simulation-based optimization. Transportation Research Procedia, Vol. 45C, 234–241. [CrossRef]

| Criteria class | Criteria name | Implications of criteria |

| time consumption for passenger travel | total travel time | The time elapsed for completing an end-user’s journey |

| transfer time | The time elapsed for transfer among the multimodal transport during a journey | |

| walking time | The time elapsed for walking within/among the key nodes or transfer station in the service network | |

| passenger waiting time | The time elapsed for waiting vehicles at stations | |

| passenger delay time | The time span between the committed service time and realized service time | |

| time consumption for vehicle usage | vehicle waiting time | The time elapsed for vehicle waiting at the key nodes or transfer stations in the service network |

| vehicle running time | The time elapsed for completing a vehicle service | |

| vehicle delay time | The time span between the expected service time and realized service time | |

| service performance of the system | response time | Time span between end-user’s booking moment and receiving mobility service moment |

| service time span | Mobility service duration provided by the transport operators, i.e., hours per day or days per week. | |

| unserved passengers | Including two parts: (1) refused travel request due to capacity shortage; (2) missed journey, i.e., the vehicle did not show up for its corresponding journey that has been booked successfully. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).