Submitted:

22 November 2023

Posted:

23 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of LFCO powders

2.2. Structural and physical characterization

3. Results and Discussion

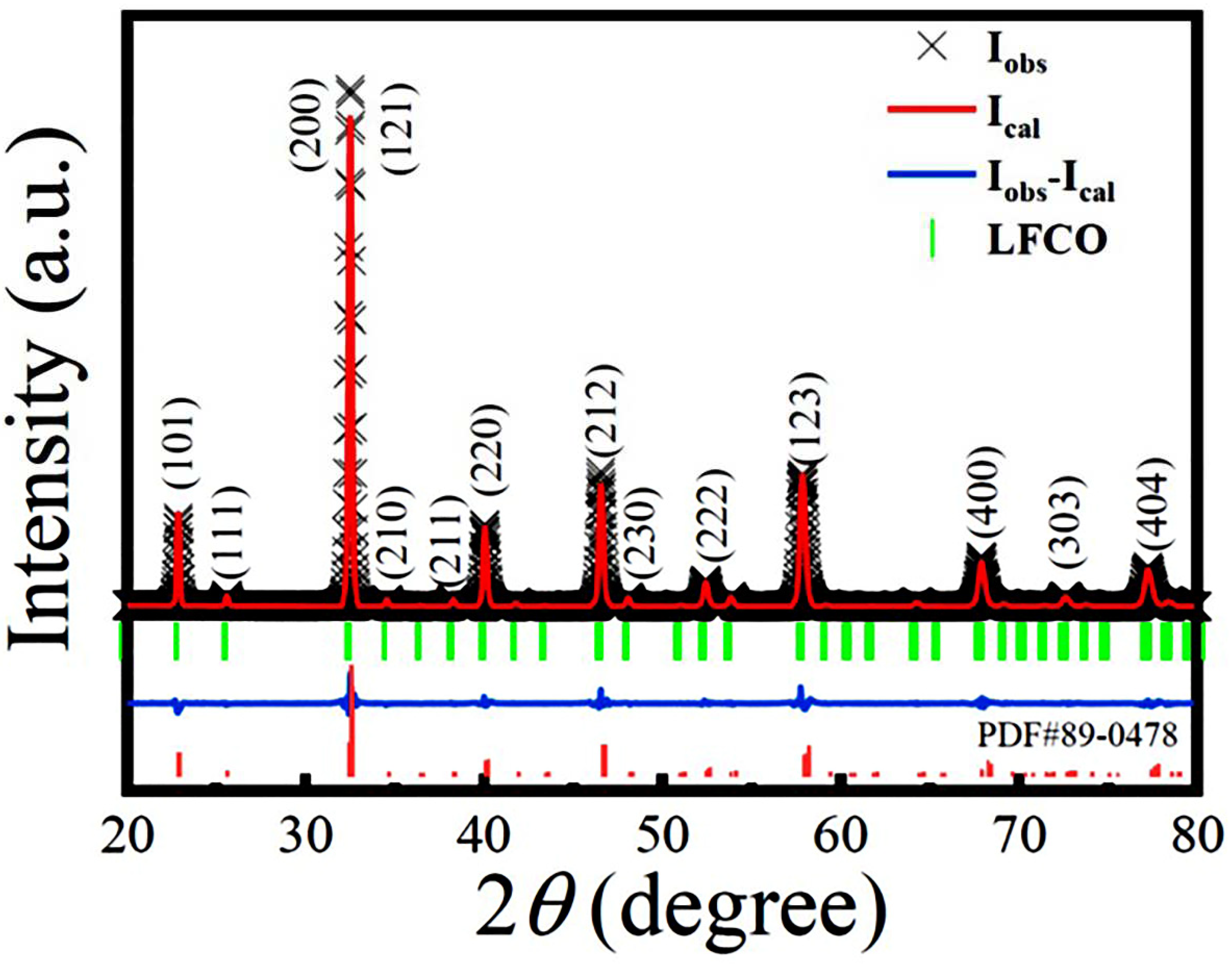

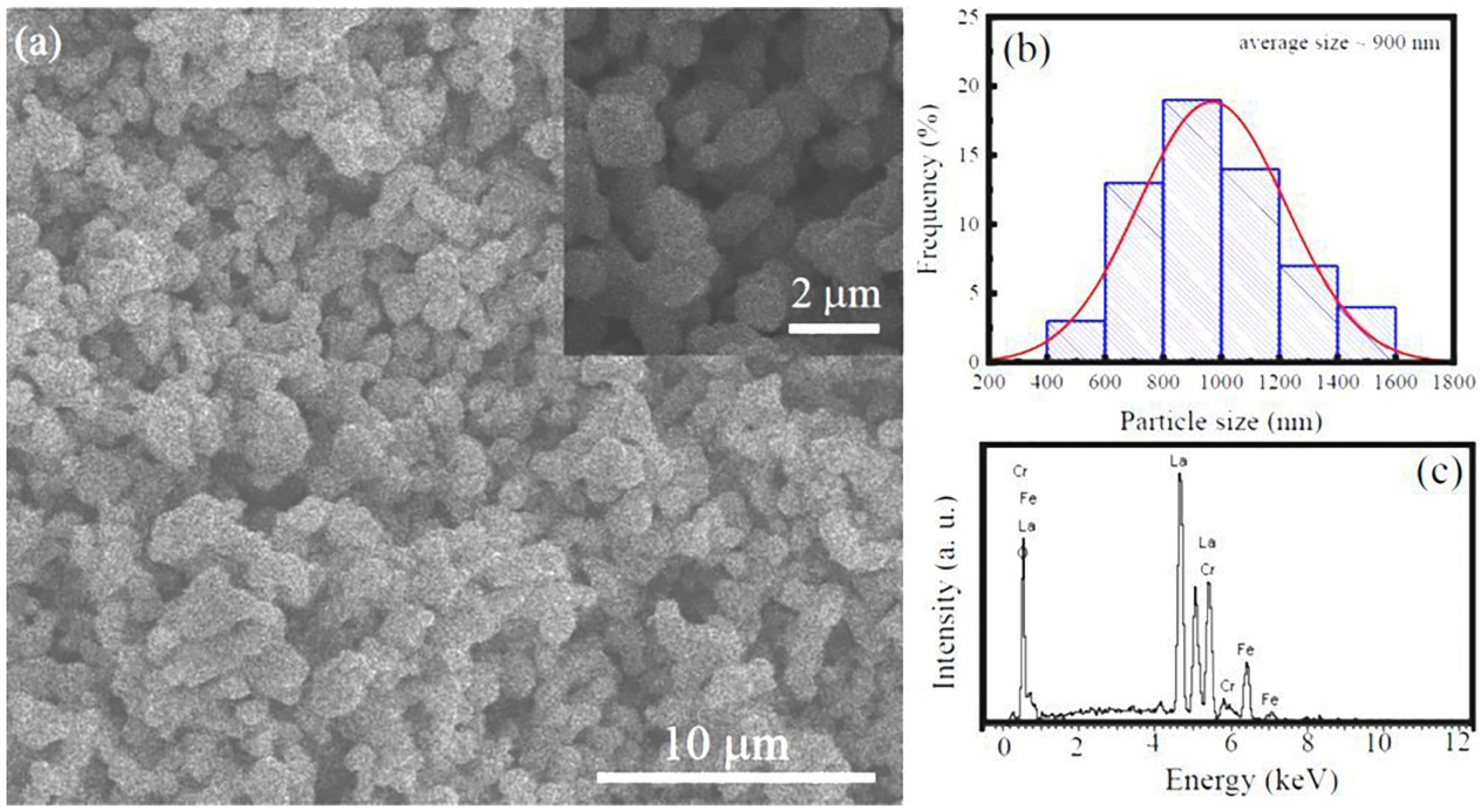

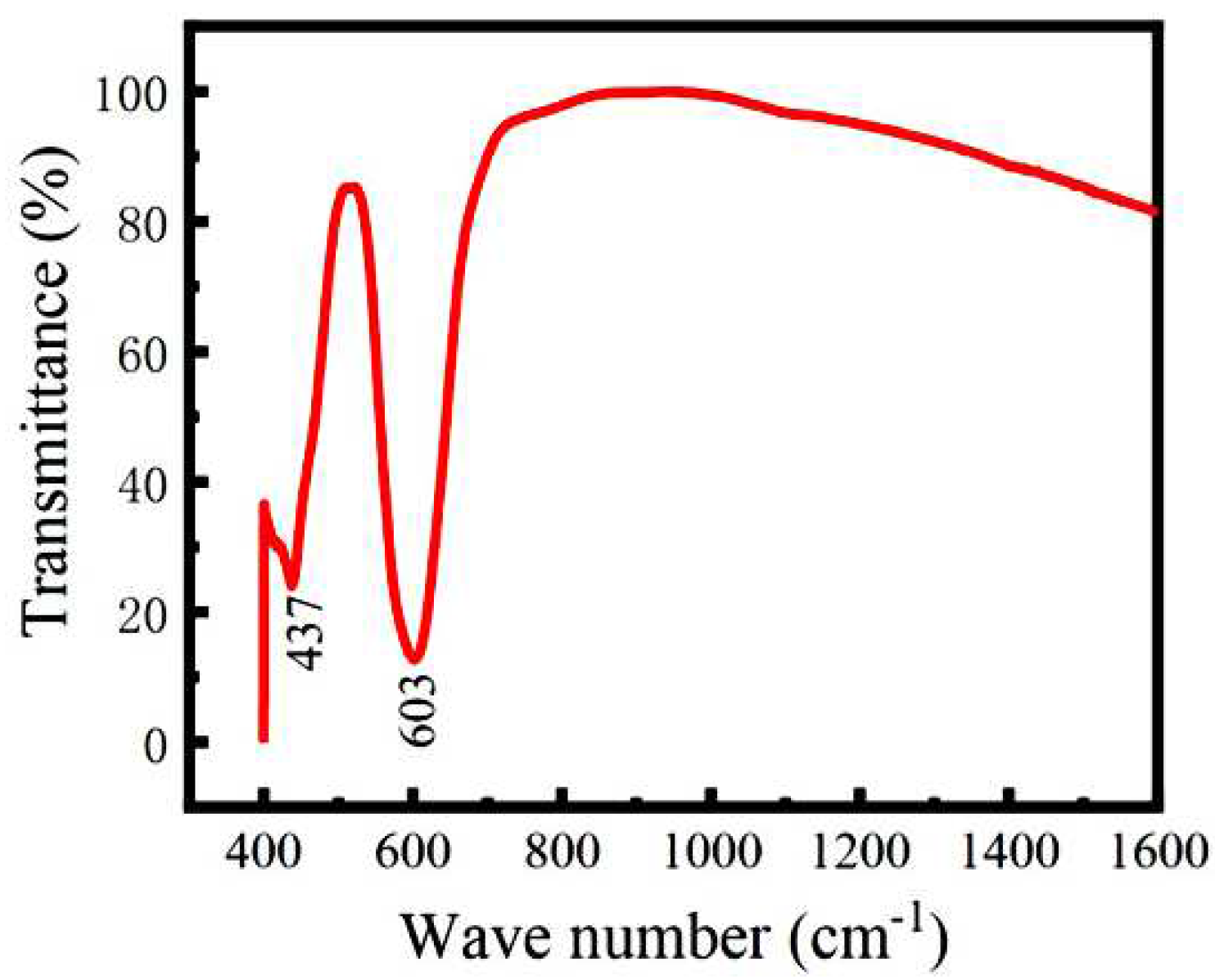

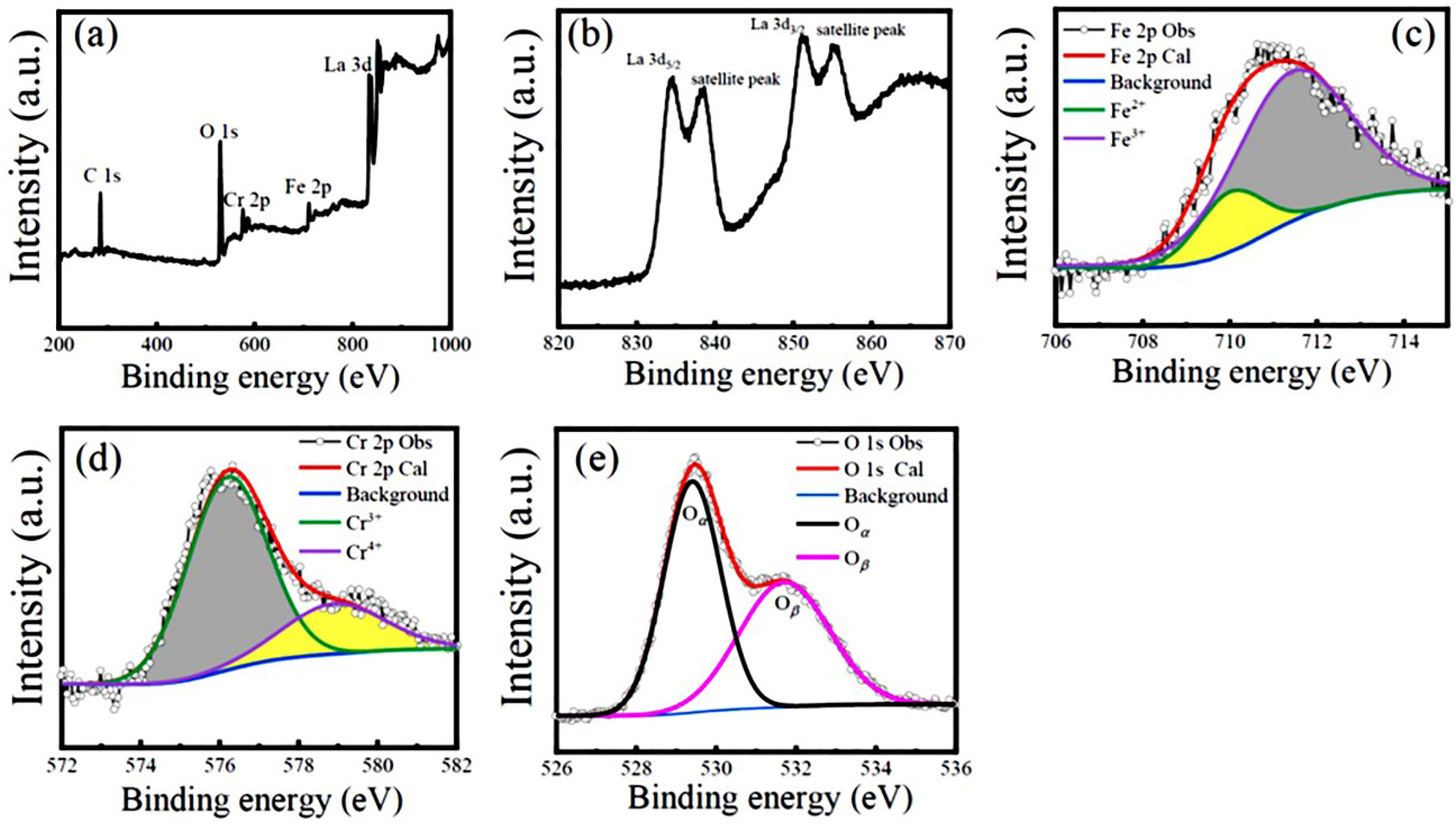

3.1. Microstructural characterization

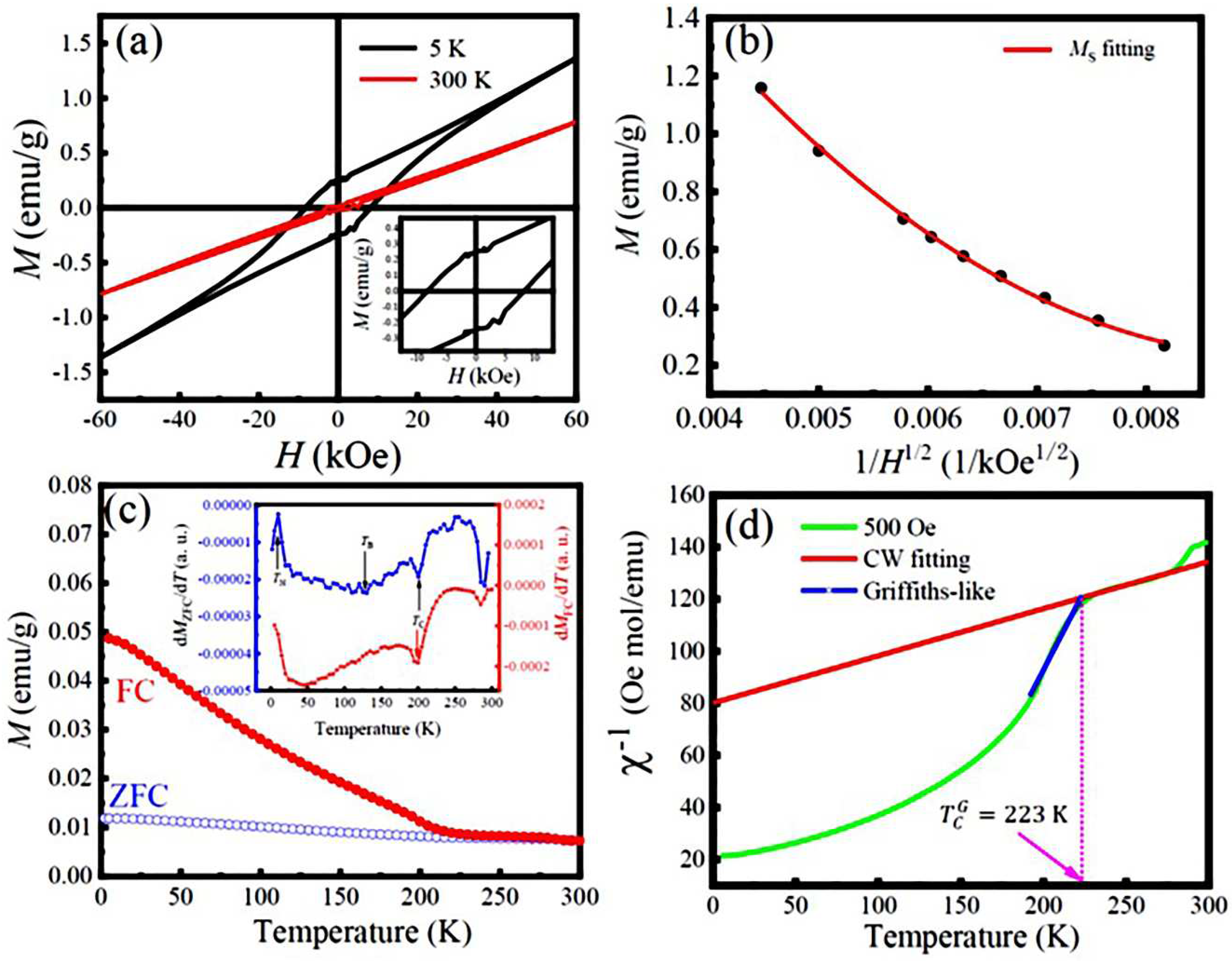

3.2. Magnetic properties

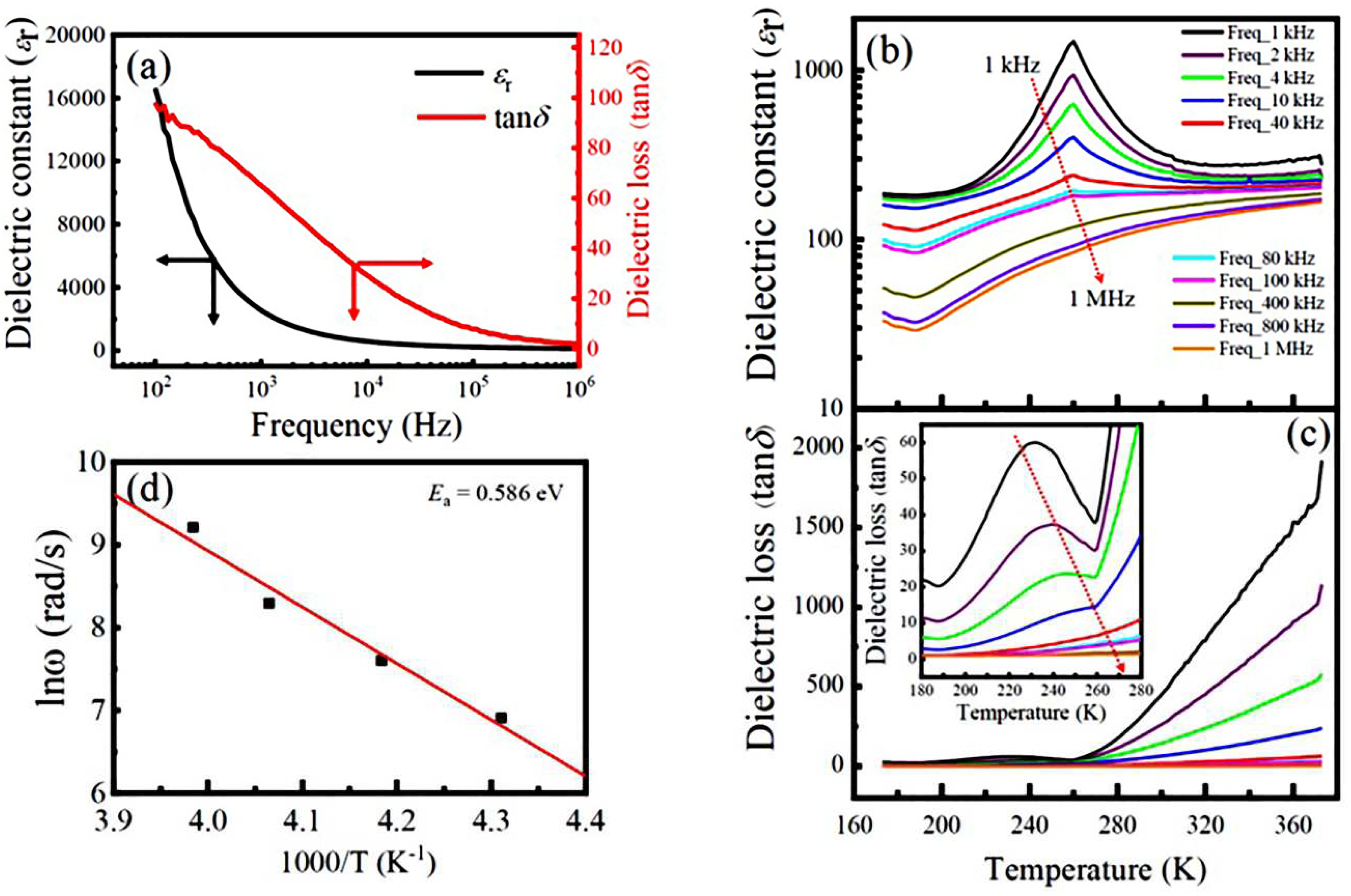

3.3. Dielectric properties

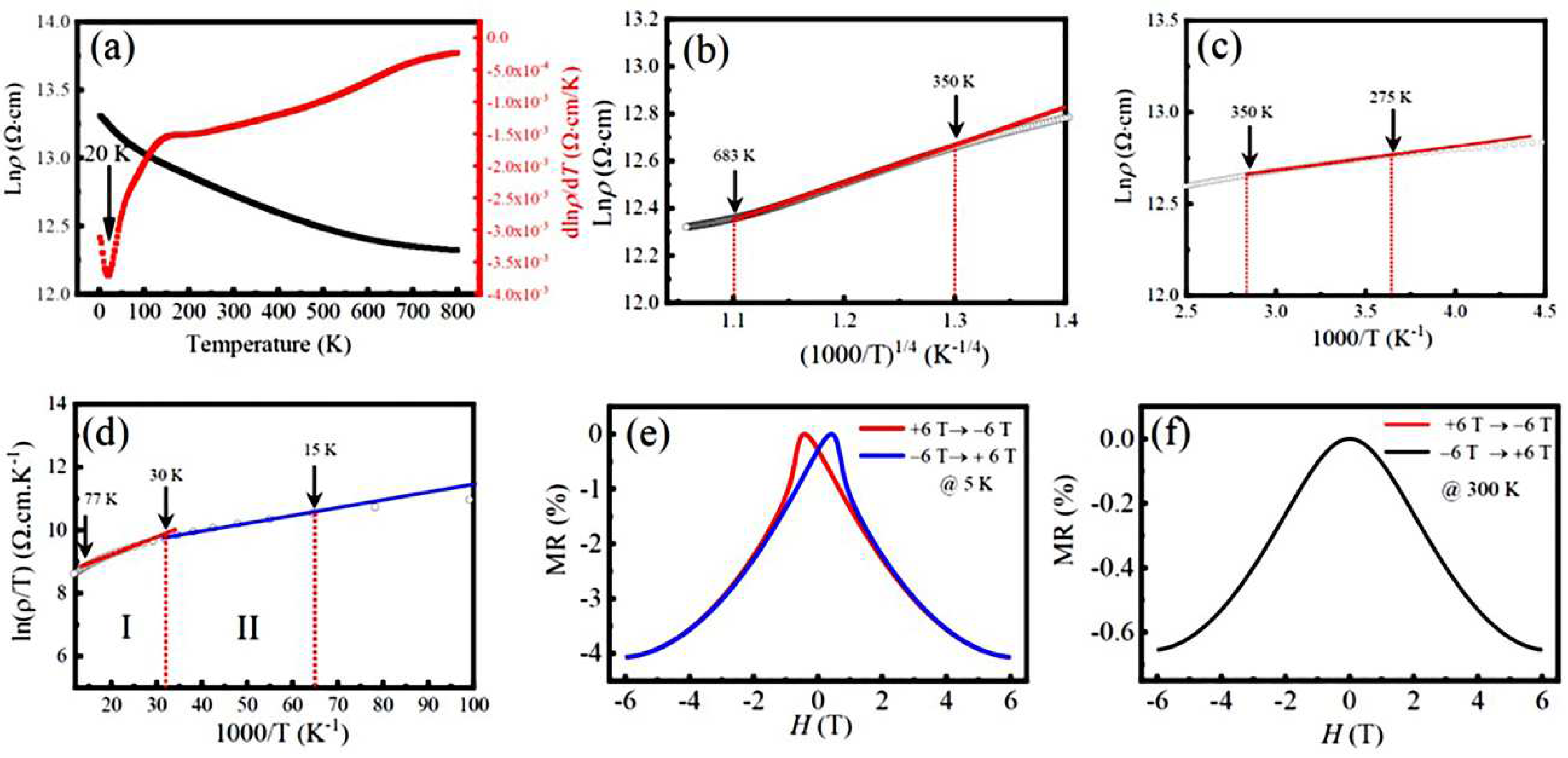

3.4. Electrical transport properties

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tokura, Y.; Kawasaki, M.; Nagaosa, N. Emergent functions of quantum materials. Nat. Phys. 13, 1056 (2017).

- Ramirez, P. Colossal Magnetoresistance. J. Phys. Condens Matter. 200, 1 (1999).

- Park, J.H.; Vescovo, E.; Kim, H.J.; Kwon, C.; Ramesh, R.; Venkatesan, T. Direct evidence for a half-metallic ferromagnet. Nature 292, 794 (1998).

- Tokura, Y. Critical features of colossal magnetoresistive manganites. Rep. Prog. Phys. 69, 797 (2006).

- Kobayashi, K.L.; Kimura, T.; Sawada, H.; Terakura, K.; Tokura, Y. Room-temperature magnetoresistance in an oxide material with an ordered double-perovskite structure. Nature 395, 677 (1998).

- Huang, Y.H.; Dass, R.I.; Xing, Z.L.; Goodenough, J.B. Double perovskites as anode materials for solid-oxide fuel cells. Science 312, 254 (2006).

- Tang, Q.K.; Zhu, X.H. Half-metallic double perovskite oxides: recent developments and future perspectives. J. Mater. Chem. C 10, 15301 (2022).

- Vasal, S.; Karppinen, M. A2BBO6 perovskites: A review. Prog. Solid State Chem. 43, 1 (2015).

- Anderson, M.T.; Greenwood, K.B.; Taylor, G.A.; Poeppelmeier, K.R. B-cation arrangements in double perovskites. Prog. Solid State Chem. 22, 197 (1993).

- Leng, K.; Tang, Q.K.; Wu, Z.W.; Yi, K.; Zhu, X.H.; Sr, D.P. Double perovskite Sr2FeReO6 oxides: structural, dielectric, magnetic, electrical, and optical properties. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 105, 4097 (2022).

- Kato, H.; Okuda, T.; Okimoto, Y.; Tomioka, Y.; Takenoya, Y.; Ohkubo, A.; Kawasaki, M.; Tokura, Y. Metallic ordered double-perovskite Sr2CrReO6 with maximal Curie temperature of 635 K. Appl. Phys. Lett. 81, 328 (2002).

- Ksoll, P.; Meyer, C.; Schueler, L.; Roddatis, V.; Moshnyaga, V. B-Site cation ordering in films, superlattices, and layer-by-layer-grown double perovskites. Crystals 11, 734 (2021).

- Wang, Z.W.; Tang, Q.K.; Wu, Z.W.; Yi, K.; Gu, J.Y.; Zhu, X.H. B-site Fe/Re cation-ordering control and its influence on the magnetic properties of Sr2FeReO6 oxide powders. Nanomaterials 12, 3640 (2022).

- Kanamori, J. Superexchange interaction and symmetry properties of electron orbitals. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 10, 87 (1959).

- Goodenough, J.B. Theory of the role of covalence in the perovskite-type manganites [La, M(II)]MnO3. Phys. Rev. 100, 564 (1955).

- Ueda, K.; Tabata, H.; Kawai, T.; LaFeO, F.I. Ferromagnetism in LaFeO3-LaCrO3 superlattices. Science 280, 1064 (1998).

- Azad, A.K.; Mellergard, A.; Eriksson, S.G.; Ivanov, S.A.; Yunus, S.M.; Lindberg, F.; Svensson, G.; Mathieu, R. Structural and magnetic properties of LaFe0.5Cr0.5O3 studied by neutron diffraction, electron diffraction and magnetometry. Mater. Res. Bull. 40, 1633 (2005).

- Weiss, A.; Goodenough, J.B. Magnetism and the Chemical Bond, New York, 1963.

- Lee, K.W.; Ahn, K.H. Evaluation of half-metallic antiferromagnetism in A2CrFeO6 (A = La, Sr). Phys. Rev. B 85, 224404 (2012).

- Chakraverty, S.; Ohtomo, A.; Okuyama, D.; Saito, M.; Okude, M.; Kumai, R.; Arima, T.; Tokura, Y.; Tsukimoto, S.; Ikuhara, Y.; Kawasaki, M. Ferrimagnetism and spontaneous ordering of transition metals in double perovskite La2CrFeO6 films. Phys. Rev. B 84, 064436 (2011).

- Pickett, W.E. Spin-density-functional-based search for half-metallic antiferromagnets. Phy Rev. B 57, 10613 (1998).

- Belayachi, A.; Nogues, M.; Dormann, J.L.; Taibi, M. Magnetic properties of LaFe1-xCrxO3 perovskites. Eur. J. Solid State Inorg. Chem. 33, 1039 (1996).

- Coutinho, P.V.; Barrozo, P. Influence of the heat treatment on magnetization reversal of orthorhombic perovskites LaFe0.5Cr0.5O3. Appl. Phys. A 124, 668 (2018).

- Sun, M.; Xuan, Y.; Liu, G.Y.; Liu, Y.L.; Zhang, F.; Ren, J.F.; Chen, M.N. Anomalous magnetic behaviors of double perovskite R2CrFeO6 (R = rare earth elements) predicted by first-principles calculations. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 504, 166670 (2020).

- Zhu, Y.Y.; Dong, S.; Zhang, Q.F.; Yunoki, S.; Wang, Y.G.; Liu, J.M. Tailoring magnetic orders in (LaFeO3)n–(LaCrO3)n superlattices model. J. Appl. Phys. 110, 053916 (2011).

- Larson, A.C.; Von Dreele, R.B. General structure analysis system (GSAS). Los Alamos National Laboratory Report LAUR, 2004, 86–748.

- Boudad, L.; Taibi, M.; Belayachi, A.; Abd-lefdil, M. Elaboration; characterization, and giant dielectric permittivity in solid state synthesized Fe half-doped LaCrO3 perovskite. Mater. Today: Proc. 58, 1108 (2022).

- Bindu, G.H.; Kammara, V.; Prilekha, S.; Swetha, K.; Laxmi, Y.K.; Veerasomaiah, P.; Vithal, M. Preparation, characterization and photocatalytic studies of LaAl0.5Fe0.5O3, LaAl0.5Cr0.5O3 and LaCr0.5Fe0.5O3. J. Mol. Struct. 1273, 134220 (2023).

- Lufaso, M.; Woodward, P. Prediction of the crystal structures of perovskites using the software program SPuDS. Acta Crystallogr. B 57, 725 (2002).

- Coey, J.M.D.; Viret, M.; von Molnár, S. Mixed-Valence Manganite. Adv. Phys. 48, 167 (1999).

- Klug, H.P.; Aleksander, L.E. X-ray Diffraction Procedures for Polycrystalline and Amorphous Materials, Willey, New York, 1974.

- Lakshmi, R.; Bera, P.; Hiremath, M.; Dubey, V.; Kundu, A.K.; Barshilia, H.C. Structural; magnetic, and dielectric properties of solution combustion synthesized LaFeO3, LaFe0.9Mn0.1O3, and LaMnO3 perovskites. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24, 5462 (2022).

- Kumar, R.; Singh, K.D.; Kumar, R. Effect of Sr substitution on structural properties of LaCrO3 perovskite. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 33, 12039 (2022).

- Zarrin, N.; Husain, S.; Khan, W.; Manzoor, S. Sol-gel derived cobalt doped LaCrO3: structure and physical properties. J. Alloy Compd. 784, 541 (2019).

- Lam, D.J.; Veal, B.W.; Ellis, D.E. Electronic structure of lanthanum perovskites with 3d transition elements. Phys. Rev. B 22, 5730 (1980).

- Moulder, J.F.; Stickle, W.F.; Sobol, P.E.; Bomben, K.D. In Handbook of X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy: A Reference Book of Standard Spectra for Identification and Interpretation of XPS Data, ed. By J. Chastain (Physical Electronics Division, Perkin-Elmer Corporation, Minnesota, 1992), p. 140.

- Coutinho, P.V.; Moreno, N.O.; Ochoa, E.A.; da Costa, M.E.H.M.; Barrozo, P. Magnetization reversal in orthorhombic Sr-doped LaFe0.5Cr0.5O3-δ. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 30, 235804 (2018).

- Rida, K.; Benabbas, A.; Bouremmad, F.; Peña, M.A.; Sastre, E.; Martínez-Arias, A. Magnetization reversal in orthorhombic Sr-doped LaFe0.5Cr0.5O3-δ. Appl. Catal. A: General. 327, 173 (2007).

- Zhang, B.; Zhao, Q.; Chang, A.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y. Electrical conductivity anomaly and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy investigation of YCr1-xMnxO3 negative temperature coefficient ceramics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 102109 (2014).

- He, H.; Lin, X.; Li, S.; Wu, Z.; Gao, J.; Wu, J.; Wen, W.; Ye, D.; Fu, M. The key surface species and oxygen vacancies in MnOx(0.4)-CeO2 toward repeated soot oxidation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 223, 134 (2018).

- Ji, D.X.; Fan, L.; Tao, L.; Sun, Y.J.; Li, M.G.; Yang, G.R.; Tran, T.Q.; Ramakrishna, S.; Guo, S.J. The Kirkendall effect for engineering oxygen vacancy of hollow Co3O4 nanoparticles toward high performance portable zinc-air batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 131, 13978 (2019).

- Doi, Y.; Hinatsu, Y. Crystal structures and magnetic properties of ordered perovskites Sr2LnRuO6 (Ln = Eu-Lu). J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 11, 4813 (1999).

- Cullity, B.D.; Graham, C.D. Introduction to Magnetic Materials, 2nd edn. (IEEE Press, New Jersey, 2009), pp. 325-326.

- Hu, W.W.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, H.M.; Zhang, G.H.; Li, G.H.; Pang, G.S.; Feng, S.H. Hydrothermal synthesis, characterization and composition-dependent magnetic properties of LaFe1-xCrxO3 system (0≤x≤1). J. Solid State Chem. 183, 1582 (2010).

- Ateia, E.E.; Gawad, D.; Mosry, M.; Arman, M.M. Synthesis and functional properties of La2FeCrO6 based nanostructures. J. Inorg Organomet. Polym. Mater. 33, 2698–2709 (2023).

- Ederer, C.; Spaldin, N.A. Weak ferromagnetism and magnetoelectric coupling in bismuth ferrite. Phys. Rev. B 71, 060401 (2005).

- Mao, Y.B.; Parsons, J.; McCloy, J.S. Magnetic properties of double perovskite La2BMnO6 (B = Ni or Co) nanoparticles. Nanoscale 5, 4720 (2013).

- Griffiths, R.B. Nonanalytic behavior above the critical point in a random Ising ferromagnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 23, 17 (1969).

- Bray, A.J. Nature of the Griffiths phase. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 586 (1987).

- Neto, A.H.C.; Castilla, G.; Jones, B.A. Non-fermi liquid behavior and Griffiths phase in f-electron compounds. Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 3531(1998).

- Boudad, L.; Taibi, M.; Belayachi, W.; Sajieddine, M.; Abd-Lefdi, M. High temperature dielectric investigation, optical and conduction properties of GdFe0.5Cr0.5O3 perovskite. J. Appl. Phys. 127, 174103 (2020).

- Castro-Couceiro, A.; Yáñez-Vilar, S.; Sánchez-Andújar, M.; Rivas-Murias, B.; Rivas, J.; Señarís-Rodríguez, M.A. Maxwell-Wagner relaxation in the CaMn7O12 perovskite. Prog. Solid State Chem. 35, 379 (2007).

- Guiffard, B.; Boucher, E.; Eyraud, L.; Lebrun, L.; Guyomar, D. Influence of donor co-doping by niobium or fluorine on the conductivity of Mn doped and Mg doped PZT ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 25, 2487 (2005).

- Pei, Z.P.; Leng, K.; Xia, W.R.; Lu, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhu, X.H. Structural characterization; dielectric; magnetic, and optical properties of double perovskite Bi2FeMnO6 ceramics. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 508, 166891 (2020).

- Huang, X.X.; Tang, X.G.; Xiong, X.M.; Jiang, Y.P.; Liu, Q.X.; Zhang, T.F. The dielectric anomaly and pyroelectric properties of sol-gel derived (Pb,Cd,La)TiO3 ceramics. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 26, 3174 (2015).

- Viret, M.; Ranno, L.; Coey, J. Colossal magnetoresistance of the variable range hopping regime in the manganites. J. Appl. Phys. 81, 4964 (1997).

- Qadir, I.; Sharma, S.; Manhas, U.; Atri, A.K.; Singh, S.; Singh, D. A new Ruddlesden-Popper oxide LaSr3Mn1.5Fe1.5O9.71 as photocatalyst for degrading highly toxic dyes in waste water: Structural, magnetic and transport properties. J. Solid State Chem. 2317, 123675 (2023).

- Emin, D.; Holstein, T. Studies of small-polaron motion IV. Adiabatic theory of the Hall effect. Ann. Phys. 53, 439 (1969).

- Kobayashi, K.I.; Kimura, T.; Tomioka, Y.; Sawada, H.; Terakura, K.; Tokura, Y. Intergrain tunneling magnetoresistance in polycrystals of the ordered double perovskite Sr2FeReO6. Phys. Rev. B 59, 11159 (1999).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).