1. Introduction

Mobile augmented reality (AR) applications present a unique opportunity to provide users with real-time assistance during non-stationary fitness activities, such as athletics [

1]. The first step towards such an application is the real-time recognition of different fitness activities using mobile sensor devices. Because commonly used approaches that rely on external video sensors such as [

2] restrict the user to stationary activities, body-worn sensors, such as inertial measurement units (IMUs), must be used for a mobile application. Recognizing fitness activities based on IMU data is, in essence, a time series classification problem: Given a sequence of sensor data points collected over a time period, predict the fitness activity performed during that time period.

Although most commonly used for visual tasks, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been shown to produce competitive results on time series classification tasks [

3], including human activity recognition (HAR) [

4]. In the context of fitness activity recognition, they have been successfully applied to various different activities, such as swing sports [

5,

6,

7], skiing [

8,

9], beach volleyball [

10], football [

11], and exercising [

12]. However, it is unclear how well CNN architectures translate to other fitness activities that can present unique challenges, such as the low availability of training data, small differences between different activities, and limited processing power on mobile devices. Furthermore, most of these papers focus on their respective use case and thus do not compare their CNN to other CNN architectures or traditional machine learning methods.

Therefore, this study aims to assess how CNN architectures can be adapted to the mobile fitness activity recognition task using IMUs and how their results compare to traditional machine learning. For this purpose, we propose a preprocessing pipeline, adaptations to three existing CNN architectures, and a new CNN architecture that aims to address the execution speed variability in fitness exercises. The performance of each architecture is evaluated on a running exercise data set that was recorded in the context of this study, and compared to a baseline of three traditional machine learning models that are commonly used in HAR. Lastly, performance changes are determined for varying numbers of sensors and input data sizes.

2. Data Acquisition

A representative data set is essential not only to train a machine learning model but also to assess its expected real-world performance. However, at the time of the study, we were unable to find a single public human activity recognition (HAR) data set that met the criteria for our study. In particular, we found that most data sets in the field of mobile HAR, such as the one provided by Anguita et al. [

13] only cover activities of daily living and not fitness activities. Other data sets such as the BasicMotions data set [

14] and the CounterMovementJump data set [

15] feature relatively few activities and only a single body-worn sensor. Furthermore, many public HAR data sets already consist of statistical features such as mean, minimum, and maximum values across a recording and, therefore, are not suitable for the CNN approaches evaluated in this study. The only data set that we could find that satisfies the previous criteria, the daily and sports activities data set by Barshan and Altun [

16], consists of data from only eight subjects and primarily features activities that are very different from each other and therefore are relatively simple to classify. Plötz et al. [

17] also acknowledge this lack of larger data sets in mobile HAR as one of its main challenges, appealing for the development of such data sets.

Therefore, we recorded a running exercise data set that is publicly available at [

18]. The data set consists of seven popular running exercises performed by 20 healthy subjects (16 m, 4 f) between 16 and 31 years of age while wearing an IMU at each ankle and each wrist for a total of four IMUs.

2.1. Activity Choice

The fitness activities for our data set were chosen based on two primary criteria: Subject availability and difficulty of classification. The availability of subjects, in particular, had to be taken into account because COVID-19 already limited the availability of subjects willing to participate in our study. We, therefore, couldn’t afford to limit subjects to those active in specific sports. On the other hand, the different activities had to be sufficiently complex and similar to one another that classification would still prove challenging to classifiers. Based on these criteria, we chose the following running exercises that are performed as warm-up exercises in different types of sports:

Since we differentiate between two different directions for side skips and Carioca running each, we have a total of seven different fitness activity classes.

2.2. Hardware

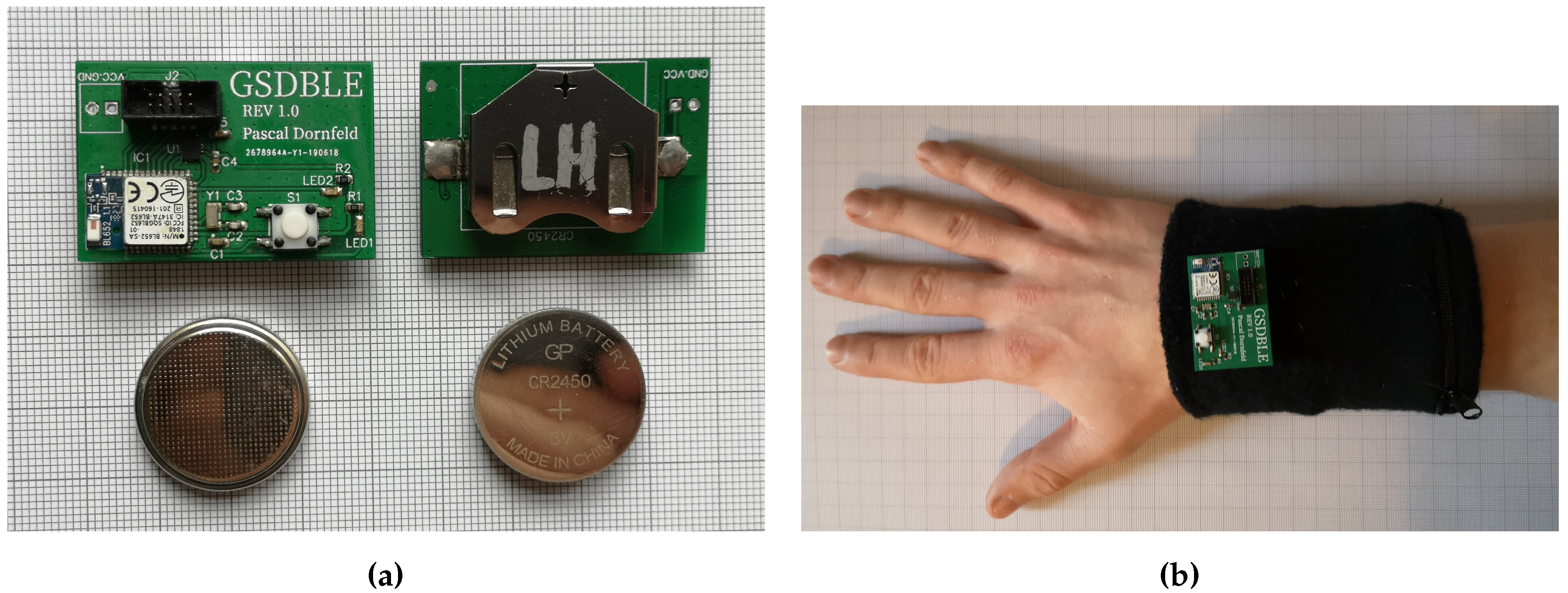

Data were recorded using four GSDBLE sensor boards that have been developed for mobile activity recognition in the context of Pascal Dornfeld’s thesis [

19] (see

Figure 1a). They are powered by a CR2450 3V lithium battery and record data with an LSM6DSL IMU from STMicroelectronics. They use a Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) connection to send their accelerometer and gyroscope data alongside time stamps to a connected smartphone. The sensor boards are contained in sweatband pockets (see

Figure 1b) so they can be worn without affecting the user’s mobility.

Subjects wore a total of four sensor boards during all recordings, one at each ankle and each wrist, respectively. All sensor boards were connected to a single Huawei P20 smartphone that aggregated all their data using a custom recording application. At the end of a recording, the application stored the sensor data, timestamps, and metadata in a JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) format file. Timestamps are recorded in milliseconds, whereas accelerometer and gyroscope values are recorded as signed 16 bit integer values representing an acceleration of and angular velocity of , respectively.

2.3. Output Data Rate & Data Loss

Since we could observe data loss with high sensor output data rates (ODRs) and four sensors connected to a single smartphone via BLE, we analyzed the incoming sensor data for data loss and timestamp inconsistencies. While our initial results suggested that data loss would only occur above 104Hz, a 40-second real-world test performing fitness exercises already showed a significant increase in data loss when going from 52Hz to 104Hz (see

Table 1). We, therefore, decided to use an ODR of 52Hz when recording our data set, since we expect the increased data rate to provide relatively little value when classifying human activities. Based on empirical tests with commercial devices that include an IMU, we expect the remaining data loss of roughly 3% to be representative of real-world applications when multiple devices are connected to a single device via BLE.

2.4. Recording Procedure

We recruited a total of 20 healthy young adults (16 m, 4 f, 16-31 yo) to participate in our study. All subjects stated that they do sport on a regular basis and know the presented or similar running exercises. Furthermore, each subject gave their informed consent to publish their anonymized recorded data. Each subject participated in one recording session, and one subject participated twice. During each recording session, a supervisor explained the scope of the study and ensured that no faulty data were recorded. In particular, they checked that the exercises were executed properly, that the sensors were worn properly, and that no hardware problems occurred. If such an issue was found during a recording, the recording was discarded and the last exercise was recorded again. Each exercise was recorded for 10 seconds per subject. The order of exercises was randomized for each subject individually to ensure that no data leakage could occur based on the order of exercise and the level of exhaustion of the subjects when performing each exercise. In practice, the order had to be slightly adjusted for some subjects to ensure that they could perform all the exercises. However, none of the subjects had to drop out of the study, resulting in complete data for all 20 subjects.

3. Preprocessing

To utilize the recorded data set in a machine learning (ML) classifier, it must be brought into a suitable format. In addition, recorded data should first be cleansed to reduce the impact of recording or transmission errors on classification performance.

3.1. Data Synchronization

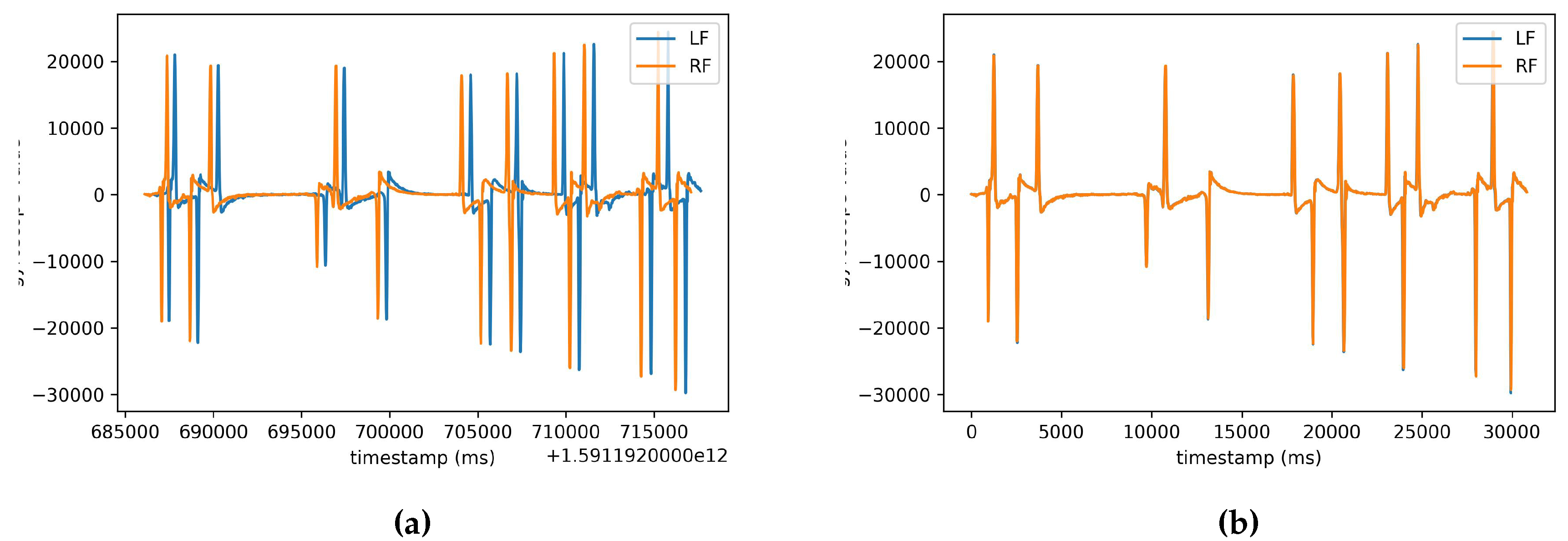

When analyzing our data set, we found that the initial timestamps

between different sensors of the same recording did not match exactly and drifted further apart over time (see

Figure 2a). To address varying initial timestamps, we shift each sensor time series to start at

by subtracting the respective sensor’s

from all its timestamp values. To address the drift in timestamps over time, we determine a scaling factor

for each sensor

n and each recording

r by dividing its last reported timestamp

by the expected timestamp at the end of the recording

. The timestamps of different sensors in each recording

r are then scaled to match each other by dividing each timestamp by the respective scaling factor

of its sensor

n. In practice, we noticed that these scaling factors were constant between recordings for each sensor and thus determined a single global scaling factor

for each sensor

n that we applied to all its recordings. In a real-time application, this might necessitate a calibration process during which this scaling factor is determined for each connected sensor.

3.2. Processing Incomplete Data

Based on our findings in

Section 2.3, we expect some data in a real-world setting to be lost during transmission. Whereas more elaborate approaches such as local or global interpolation exist to address missing data values, we opt for a duplication of the previous data value whenever an expected data value at a given timestamp is missing. In a real-time application, this allows for all data to be processed immediately instead of having to wait for the next data to interpolate a missing value. Based on our empirical findings, neither method provides a noticeable increase in classification performance over the other in our data set. However, a more elaborate approach might be preferable if a higher data loss is observed.

In the event that at least 10% of the expected samples were missing during the course of a 10-second recording for at least one sensor, the recording was completely discarded for the purpose of our evaluation. This was typically only the case when one sensor stopped sending data altogether and occurred four times in our 147 recordings, resulting in a total of 143 remaining recordings.

3.3. Standardization

Many machine learning architectures require the input data to be normalized or standardized for optimal training. Since we have two different types of data, acceleration and angular velocity, we use the standardization formula to scale all data to and to prevent one type of data from dominating the other during training. The values for and were calculated once for all accelerometer data and once for all gyroscope data in the data set and then applied to all samples. We decided against calculating and for individual sensor positions and axes to preserve the relative differences in intensity. In a real-time application, these values could be supplied alongside the model to ensure consistent data values between training and inference.

3.4. Segmentation

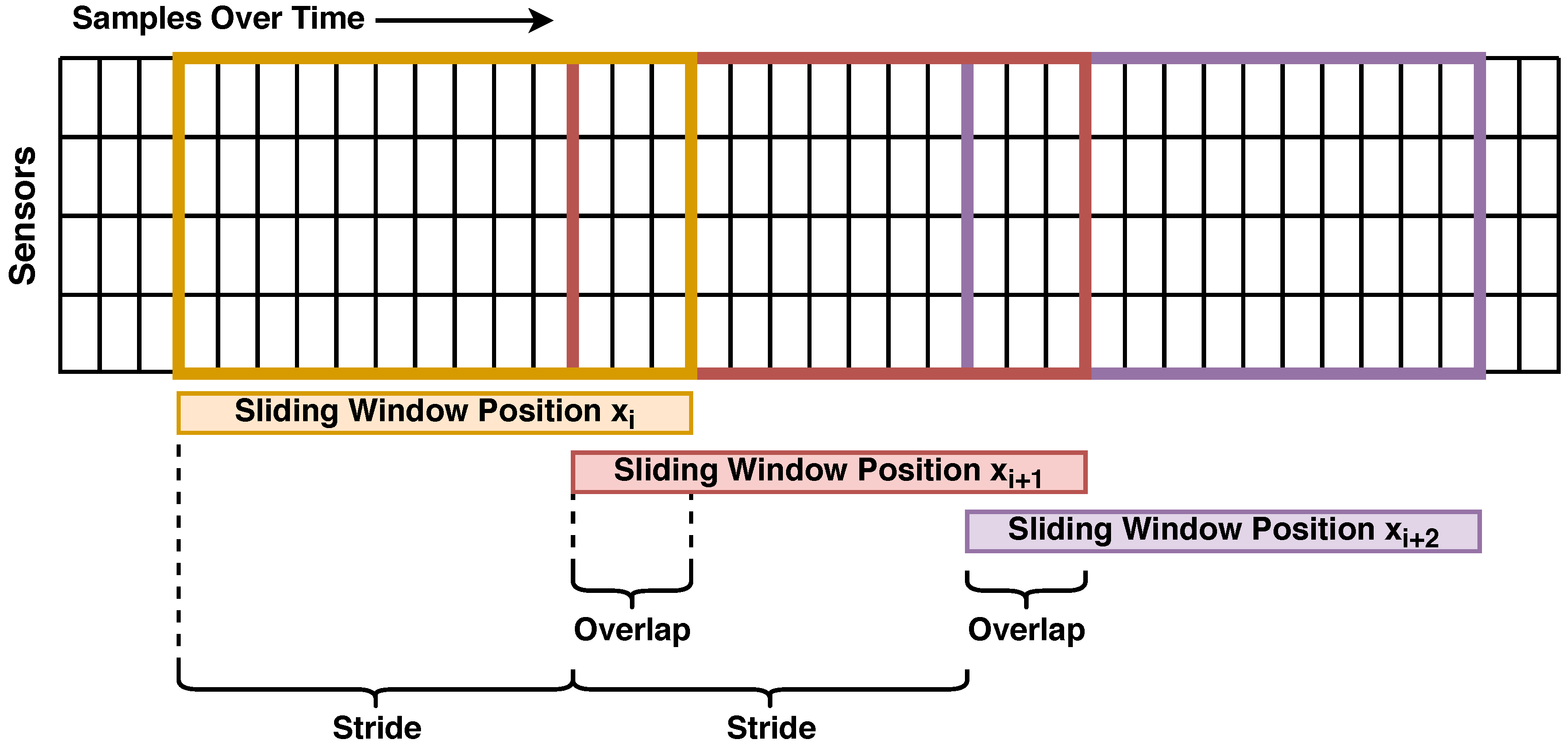

To simulate the use case of a real-time application, data recordings have to be split into individual segments, each segment representing the data that last arrived at the application at a given point in time. Each segment later serves as one input sample in our experiments. For this purpose, we use a sliding-window approach as shown in

Figure 3. An overlap of 75% is used in all of our experiments to allow a sufficient number of samples to be generated without consecutive samples being too similar to each other. We compare three different window sizes of 13, 26, and 52 timestamps in

Section 6.2.1, representing 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 seconds of data, resulting in a stride of three, seven, and 14 timestamps, respectively.

When evaluating machine learning architectures, it is common practice to segment the given data set into three distinct partitions; a training set for model training, a validation set to assess model performance during design and optimization phases, and a test set to assess the final model performance on previously unseen data. To prevent data leakage between the different sets, we split our data set on a per-subject basis. This ensures that data from each subject is only included in a single set and that classes are represented equally in each set. It is representative of the typical real-world use case of a machine learning model having to predict a user’s activity without having seen data from the same user during training.

Our static test set consists of the data of four randomly selected participants, or 20% of all participants. For the training and validation sets, we instead use a leave-one-subject-out cross-validation approach to generate 16 different training/validation splits. By using the data of each participant not in the test set once for validation and 15 times for training, we maximize the number of data in the training set while also minimizing the impact of individual participants’ data on validation results. As a result of this approach, each model is trained a total of 16 times for each scenario.

3.5. Traditional Machine Learning Features

For traditional machine learning algorithms, we use eight statistical features that are calculated separately for each sensor position and axis: The highest absolute value, the maximum, the minimum, the difference between the minimum and maximum, the mean, the standard deviation, the skewness, and the kurtosis. We decided on these features because they are commonly used in HAR and do not depend on which point during a movement repetition the recording starts from. Our empirical tests did not show a significant improvement in classification performance with a feature subset selection, so we kept all features to prevent potential overfitting of the feature set to the data set.

4. CNN Architectures

To account for the variety of CNN architectures available, we adapted three different CNN architectures that have been shown to perform well in time-series classification tasks. Furthermore, we designed a fourth CNN architecture that utilizes data rescaling as proposed by Cui et al. [

20].

Modifications to existing architectures were made when necessary to allow inference on mobile devices. While recent work shows that current mobile phones are capable of running image classification models inference fast enough for real-time applications [

21,

22,

23,

24], and further optimizations are possible [

25], implemented models should still aim to limit the parameter count to preserve battery life and save computational resources. This can be particularly important in mobile HAR applications, where recognition models may run for prolonged amounts of time in the background. Since we furthermore expect that the task of recognizing fitness activities will be less complex than the task of recognizing images, for which models usually contain at least one million parameters [

21], we set one million as the upper limit for the parameter count of our models.

Our Deep-CNN architecture is based on the VGG16 architecture introduced by Simoyan et al. [

26] which has been used in successful image classification like AlexNet [

27] in the past. To reduce the size of the network for mobile real-time application and adapt the network to smaller input sizes, we removed the first two blocks of convolutional layers, reduced the number of filters in the remaining three convolution blocks, and removed the pooling layers preceding each block of convolution layers. After each convolutional and fully connected layer, batch normalization was added. Lastly, we adjusted the size of the fully connected layers at the end of the model to fit the expected number of output classes and further limit the total parameter count. In total, the network has a total of nine convolution layers divided into three blocks, each doubling the number of filters in the previous block. ReLU was kept as the network’s activation function.

4.1. Fully Convolutional Network (FCN)

Instead of fully connected layers, fully convolutional networks (FCNs) use global pooling to generate inputs for the final softmax layer [

28], and achieve impressive results in image segmentation tasks [

29]. We use the FCN architecture of Wang et al.[

30] as a baseline for our network. Since the architecture was already optimized for time series classification (TSC) and their model parameters are specified precisely, no large adjustments were necessary. As a result, we use the same architecture consisting of three convolution layers with 128, 256, and 128 filters, respectively, as well as an average pooling layer for global pooling. ReLU is again used as the activation function, whereas a softmax layer produces the final output.

4.2. Residual Network (ResNet)

Residual networks (ResNets) make use of residual connections to outperform regular CNNs with similar depths and parameter counts [

31]. Wang et al. [

30] again provide a ResNet that has been successfully applied in time-series classification and is used with minimal adjustments in our work. The model consists of three residual blocks with three convolution layers followed by batch normalization and ReLU activation each. The final output is again generated using global pooling and a softmax layer.

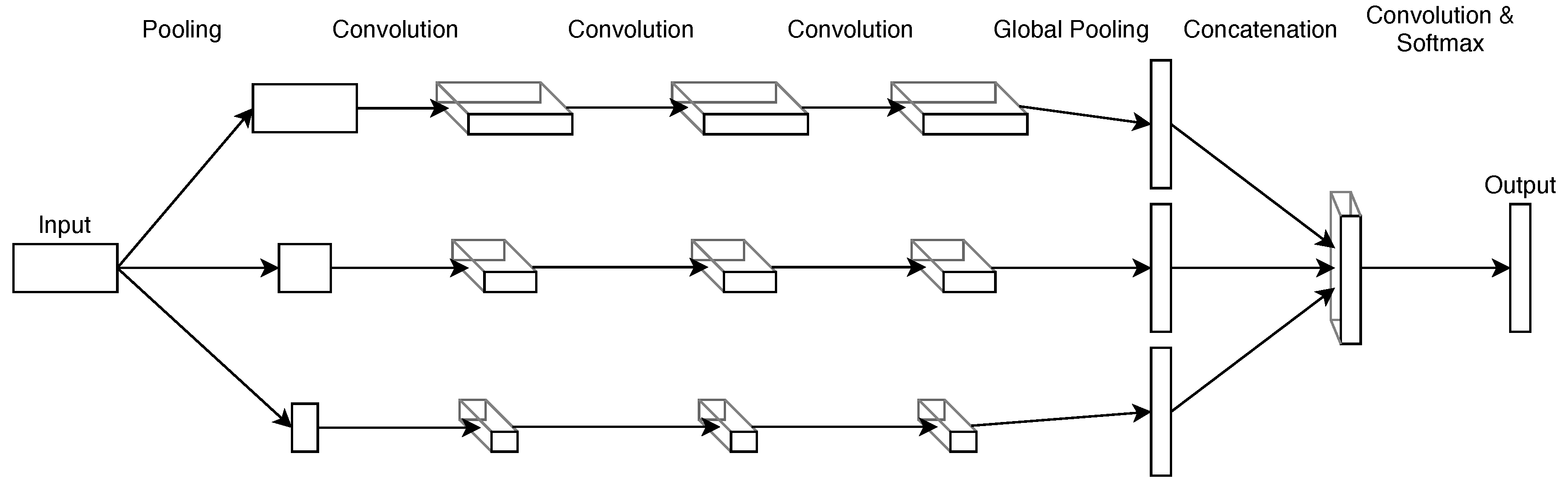

4.3. Scaling-FCN

The speed of execution of fitness activities can differ significantly between individuals based on factors such as fitness and motivation. In addition, fitness activities often consist of multiple overlapping movements that may be performed at varying time intervals. We reflect this in our scaling fully convolutional network (Scaling-FN), shown in

Figure 4, by using 1-dimensional average pooling layers at the beginning of the network to rescale the input data in its time dimension. Compared to approaches such as the multiscale convolutional neural network of Cui et al. [

20], our approach does not drop any data that could contain important information and is comparable to filtering in image classification, such as [

32]. After scaling the input data to three different sizes, each scaled input is processed in parallel by three convolution layers and a global average pooling layer. The data are then concatenated and fed into the final convolution and softmax layers to create the final output. Similarly to ResNet, each convolution layer is followed by a batch normalization and a ReLU activation function.

5. Traditional Machine Learning

To create a baseline for CNN architectures, we use three traditional machine learning architectures. Random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM), and k-nearest neighbors (K-NN). We chose these particular architectures because they are commonly used in human activity recognition (HAR) and typically produce the best results among traditional machine learning approaches [

33]. For each architecture, the default multiclass classifier implementation as found in scikit-learn version 1.3.0

1 was used. The input data for these architectures are statistical features that were generated for each dimension of the input data, resulting in

features for

d-dimensional sensor data (see

Section 3.5). A grid search was performed to determine hyperparameters for each architecture using the same leave-one-subject-out cross-validation on the training set as described in

Section 3.4.

Table 2 shows the three architectures identified by their scikit-learn implementation and selected hyperparameter values for the hyperparameters that were optimized.

6. Results

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the usability of CNN architectures in the context of IMU-based recognition of fitness activities. For this purpose, we first determine a baseline using the traditional machine learning architectures presented in

Section 5 that are commonly used for human activity recognition. We then compare the performance of these architectures with that of the CNN architectures presented in

Section 4. Finally, we assess the performance impact when there are fewer sensor data available for classification.

For each scenario and architecture, we performed a leave-one-subject-out cross-validation with splits as detailed in

Section 3.4, resulting in 16 models each. CNNs were trained with early stopping and a maximum of 1000 epochs. For each model trained during cross-validation, we additionally measured its performance on the test set that was not used during any training or hyperparameter optimization for any architecture. Therefore, we report performance metrics as the mean and standard deviation of the 16 trained models. As we have a well-balanced dataset, we will primarily present results using accuracy as a metric instead of resorting to less intuitive metrics such as the F1 score.

6.1. Architecture Performance

Table 3 shows the performance of all architectures during cross-validation and on the test set for the default input sensor data consisting of 1s segments (52 sensor readings) with individual axis data for the four sensors (24 data per reading). For traditional machine learning, the features detailed in

Section 3.5 were generated from the input data. It can be seen that all CNN models outperform all traditional machine learning models, with ResNet achieving the best overall accuracy of 97.14% on the test set, and FCN and our Scaling-FCN closely follow with 96.74% and 96.46%, respectively. With 94.97% accuracy on the test set, SVM is the only traditional machine learning model that comes reasonably close to CNNs, while K-NN and RF perform significantly worse with 91.75% and 91.71%, respectively.

Most models perform better during cross-validation, suggesting that some of the selected hyperparameters might favor our specific cross-validation split. Across all architectures, the standard deviation is significantly higher during cross-validation than on the test set, suggesting that the models perform significantly better for some people in the data set than for others. As seen in

Table 4, CNN models generally stopped training well before the maximum of 1000 epochs was reached, suggesting that no potential performance was lost due to the maximum number of epochs. ResNet and Deep-CNN generally stopped training the earliest, with an average of 286 and 263 epochs, respectively, whereas our Scaling-FCN stopped the latest, with an average of 591 epochs.

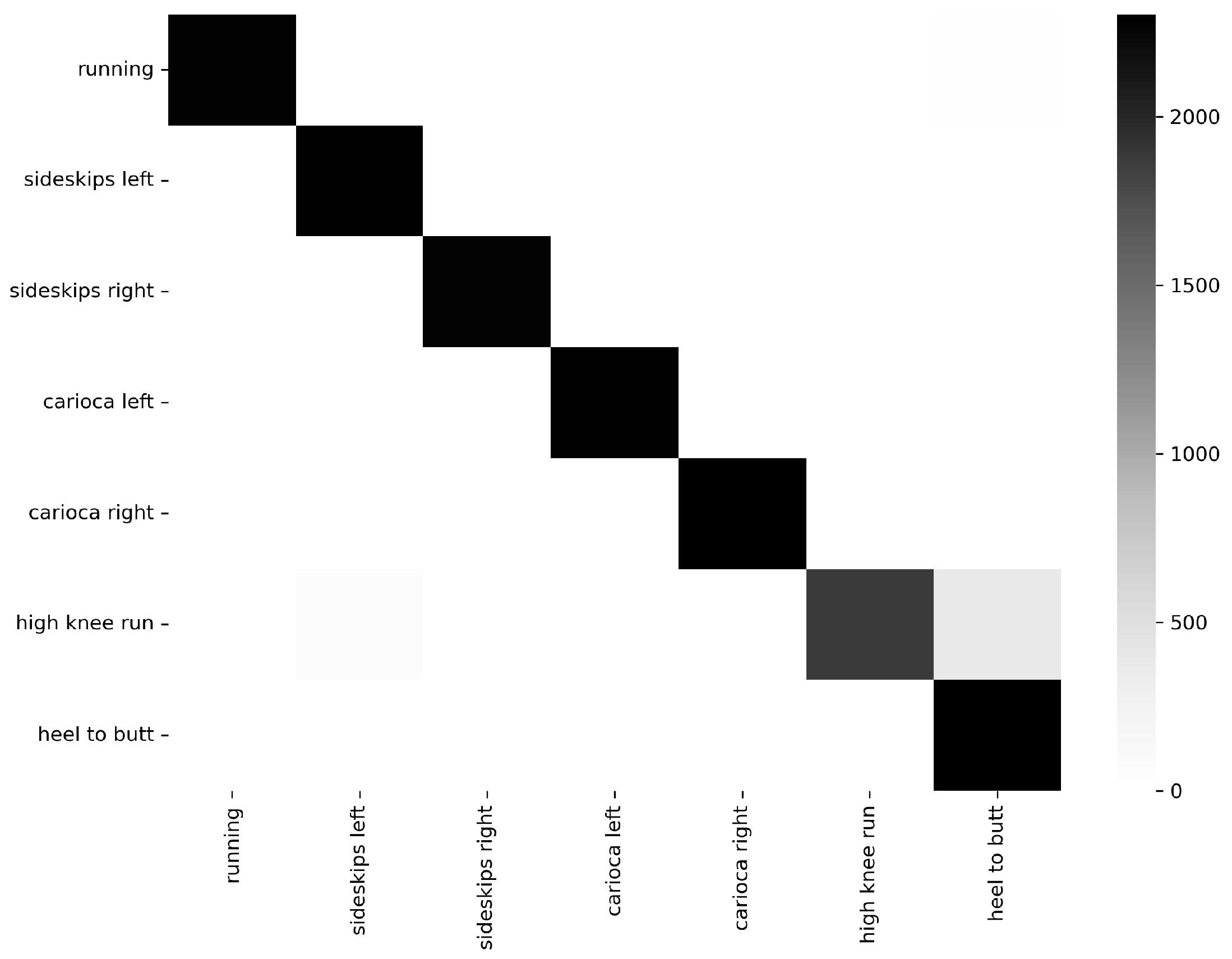

When looking at individual classes’ F1 scores (not shown here), all models share classification errors for high-knee running and heel-to-butt running. This can also be observed in their respective confusion matrices, as shown in

Figure 5 for the ResNet model. Although most classes are accurately recognized, high-knee running is often misclassified as heel-to-butt running instead, suggesting that these two exercises generate very similar sensor data, making them difficult to differentiate.

6.2. Impact of sensor data on performance

To determine the impact of input sensor data on model performance, we repeated the previous experiment with varying time windows, sensor data dimensions, and sensor numbers. In the following, we present the most interesting findings with a focus on the overall best-performing ResNet and particularly interesting input data configurations.

6.2.1. Time Window Length

The time window length for the input data is an interesting parameter because it affects not only the total size of the input data but also the recency of the data used for classification. A reduced time window length might, therefore, be interesting when recognizing activity types where individual activities rapidly change, e.g., individual kicks and punches during kickboxing, because data from the previous activity are more quickly discarded. However, on our data set consisting of prolonged activities, we found that reducing the time window length always resulted in lower classification accuracy, as shown exemplarily for Resnet in

Table 5 for window lengths of 52, 26, and 13 samples, corresponding to 1.0, 0.5, and 0.25 seconds of data each. Although there is a significant drop in accuracy when reducing the time window length, ResNet still achieves a respectable 94.96% accuracy with just 0.25 seconds of data, performing on par with or even outperforming traditional machine learning models with 1s of data.

6.2.2. Sensor Dimensions

By default, accelerometers and gyroscopes provide 3-dimensional data, resulting in a total of six dimensions for each IMU. This may result in inconsistent data when the sensors are not applied exactly at the same location and in the same orientation. A potential solution is to instead use the rotation-invariant vector length of the vector spanned by the three dimensions of each sensor that represent total acceleration and total angular velocity, respectively. As seen in

Table 6, ResNet still achieves a respectable 96.0% test accuracy with rotation-invariant data. Whereas the data show a performance gain when adding vector lengths as a fourth dimension to existing three-dimensional data, the difference is small enough to possibly be the result of variances between cross-validations.

6.2.3. Sensor Number and Position

In a real-world scenario, wearing a sensor on each wrist and ankle may not be desirable or even possible. Therefore, we evaluated how CNN models perform for different subsets of our default sensor configuration. As can be seen in

Table 7 for ResNet, the number and position of sensors can have a large impact on activity recognition. As expected for our running exercise data set, subsets without data from either foot decrease significantly in performance and only achieve approximately 83% test accuracy. Interestingly, model performance consistently improves when seemingly redundant data are removed, resulting in the highest accuracy of 98.59% being achieved when only data from a single ankle are used.

Although this behavior was consistent for all CNN models, traditional machine learning models did not share the same behavior and instead performed significantly worse without data from either wrist.

Table 8 shows the performance of all CNN and traditional machine learning models when only data from the right ankle is used. In this scenario, traditional machine learning models dropped to between 77.14% and 83.42% test accuracy, comparable to the performance CNNs achieve when only using wrist sensor data. With a test accuracy of 99.86%, our Scaling-FCN performs extremely well on this reduced problem, performing better than any other architecture in the process. Interestingly, almost all models now performed worse during cross-validation than on the test set. This could suggest that wrist data was more important when classifying activities of participants in the training set than when classifying those of participants in the test set.

In an attempt to find the absolute best model on our data set, we also checked for combinations of the parameters assessed previously, but could not find any combinations for which the CNNs performed better than for a time window of 52 samples and 3-dimensional sensor data from a single ankle. In particular, all models performed worse with 4-dimensional sensor data than they did with 3-dimensional sensor data when only data from a single ankle were used.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we investigate the applicability of CNN-based architectures to the task of IMU-based fitness activity recognition. For this purpose, we designed a preprocessing pipeline, adapted three existing CNN architectures, and developed the Scaling-FCN architecture. Furthermore, we recorded a new data set [

18] consisting of IMU data for seven different exercises performed by 20 participants, which is made publicly available. We evaluated the four CNN architectures by comparing their performance with three traditional machine learning architectures commonly used in human activity recognition and assessing the impact that different input data parameters had on their performance.

The results of our evaluation suggest that CNN-based architectures are well suited for IMU-based fitness activity recognition, reaching up to 97.14% accuracy on our test set when using input data from all IMUs. They consistently outperformed traditional machine learning architectures. This performance gap increased when there was less data available in the input, suggesting that CNNs are particularly well suited when there are few sensors available. Although traditional machine learning performance dropped when only ankle data were available, the performance of CNN architectures improved further to up to 99.86% accuracy on the test set. Despite losing performance when shorter time windows were used as input data, CNNs were still able to achieve up to 96.00% accuracy with only 0.25 seconds of data.

In future work, we plan to investigate the performance of the Scaling-FCN within our pipeline on other data sets consisting of different fitness activities and to ultimately apply it within the context of a mobile (AR) fitness application to track the user’s fitness activity and provide real-time feedback. As our data set is publicly available, we hope other scientists can utilize it to evaluate their systems and provide reference data for different machine learning architectures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.N.M., A.J.M., P.A. and S.G.; methodology, P.N.M. and A.J.M.; software, P.N.M. and A.J.M.; validation, P.N.M. and A.J.M.; formal analysis, P.N.M. and A.J.M.; investigation, A.J.M.; resources, P.N.M. and S.G.; data curation, A.J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.N.M. and A.J.M.; writing—review and editing, P.N.M., P.A. and S.G.; visualization, P.N.M. and A.J.M.; supervision, P.N.M. and S.G.; project administration, P.N.M. and S.G.; funding acquisition, S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AR |

augmented reality |

| TSC |

time series classification |

| HAR |

human activity recognition |

| FAR |

fitness activity recognition |

| ML |

machine learning |

| DL |

deep learning |

| ANN |

artificial neural network |

| CNN |

convolutional neural network |

| ResNet |

residual neural network |

| Deep-CNN |

deep convolutional neural network |

| FCN |

fully convolutional network |

| Scaling-FCN |

scaling fully convolutional network |

| RF |

random forest |

| SVM |

support vector machine |

| K-NN |

k-nearest neighbor |

| IMU |

inertial measurement unit |

| BLE |

bluetooth low energy |

| ODR |

output data rate |

| JSON |

javascript object notation |

References

- Müller, P.N.; Fenn, S.; Göbel, S. Javelin Throw Analysis and Assessment with Body-Worn Sensors. In Proceedings of the Serious Games; Haahr, M.; Rojas-Salazar, A.; Göbel, S., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2023; Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pp. 36–49.

- Nadeem, A.; Jalal, A.; Kim, K. Accurate Physical Activity Recognition Using Multidimensional Features and Markov Model for Smart Health Fitness. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail Fawaz, H.; Forestier, G.; Weber, J.; Idoumghar, L.; Muller, P.A. Deep Learning for Time Series Classification: A Review. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2019, 33, 917–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerla, N.Y.; Halloran, S.; Plötz, T. Deep, Convolutional, and Recurrent Models for Human Activity Recognition UsingWearables. arXiv preprint arXiv:1604.08880 2016, [1604.08880].

- Tabrizi, S.S.; Pashazadeh, S.; Javani, V. Comparative Study of Table Tennis Forehand Strokes Classification Using Deep Learning and SVM. IEEE Sensors Journal 2020, 20, 13552–13561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.; Sharma, M.; Srivastava, R.; Kaligounder, L.; Prakash, D. Wearable Motion Sensor Based Analysis of Swing Sports. In Proceedings of the 2017 16th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA). IEEE, 2017, pp. 261–267. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Bie, R.; Wu, H.; Wei, Y.; Ma, J.; Umek, A.; Kos, A. Golf Swing Classification with Multiple Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks 2018, 14, 1550147718802186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassem, A.; El-Beltagy, M.; Saleh, M. Cross-Country Skiing Gears Classification Using Deep Learning, 2017, [arxiv:cs.CV/1706.08924].

- Brock, H.; Ohgi, Y.; Lee, J. Learning to Judge like a Human: Convolutional Networks for Classification of Ski Jumping Errors. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2017 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers, 2017, pp. 106–113. [CrossRef]

- Kautz, T.; Groh, B.H.; Hannink, J.; Jensen, U.; Strubberg, H.; Eskofier, B.M. Activity Recognition in Beach Volleyball Using a Deep Convolutional Neural Network: Leveraging the Potential of Deep Learning in Sports. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2017, 31, 1678–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeve, M.; Schuldhaus, D.; Gamp, A.; Zwick, C.; Eskofier, B.M. From the Laboratory to the Field: IMU-Based Shot and Pass Detection in Football Training and Game Scenarios Using Deep Learning. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patalas-Maliszewska, J.; Pajak, I.; Krutz, P.; Pajak, G.; Rehm, M.; Schlegel, H.; Dix, M. Inertial Sensor-Based Sport Activity Advisory System Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguita, D.; Ghio, A.; Oneto, L.; Parra, X.; Reyes-Ortiz, J.L. A Public Domain Dataset for Human Activity Recognition Using Smartphones. Computational Intelligence 2013, p. 6.

- Clements, J. BasicMotions Dataset.

- O’Reilly, M.; Le Nguyen, T. CounterMovementJump Dataset.

- Barshan, B.; Altun, K. Daily and Sports Activities. UCI Machine Learning Repository, 2013.

- Plötz, T.; Guan, Y. Deep Learning for Human Activity Recognition in Mobile Computing. Computer 2018, 51, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, P.N.; Müller, A.J. Running Exercise IMU Dataset, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dornfeld, P. Entwicklung eines Systems für die Mobile Sensordatenerfassung zur Erkennung von Ganzkörpergesten in Echtzeit 2019. p. 53.

- Cui, Z.; Chen, W.; Chen, Y. Multi-Scale Convolutional Neural Networks for Time Series Classification. arXiv:1603.06995 [cs] 2016, [arxiv:cs/1603.06995].

- Sehgal, A.; Kehtarnavaz, N. Guidelines and Benchmarks for Deployment of Deep Learning Models on Smartphones as Real-Time Apps. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction 2019, 1, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; He, X.; Zhan, J.; Wang, L.; Gao, W.; Dai, J. Comparison and Benchmarking of AI Models and Frameworks on Mobile Devices. arXiv:2005.05085 [cs, eess] 2020, [arxiv:cs, eess/2005.05085].

- Deng, Y. Deep Learning on Mobile Devices: A Review. In Proceedings of the Mobile Multimedia/Image Processing, Security, and Applications 2019; Agaian, S.S.; DelMarco, S.P.; Asari, V.K., Eds.; SPIE: Baltimore, United States, 2019; p. 11. [CrossRef]

- Ignatov, A.; Timofte, R.; Chou, W.; Wang, K.; Wu, M.; Hartley, T.; Van Gool, L. AI Benchmark: Running Deep Neural Networks on Android Smartphones. In Computer Vision – ECCV 2018 Workshops; Leal-Taixé, L.; Roth, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; Vol. 11133, pp. 288–314. [CrossRef]

- Niu, W.; Ma, X.; Wang, Y.; Ren, B. 26ms Inference Time for ResNet-50: Towards Real-Time Execution of All DNNs on Smartphone. arXiv:1905.00571 [cs, stat] 2019, [arxiv:cs, stat/1905.00571].

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. arXiv:1409.1556 [cs] 2015, [arxiv:cs/1409.1556].

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 25; Pereira, F.; Burges, C.J.C.; Bottou, L.; Weinberger, K.Q., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc., 2012; pp. 1097–1105.

- Lin, M.; Chen, Q.; Yan, S. Network In Network. arXiv:1312.4400 [cs] 2014, [arxiv:cs/1312.4400].

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully Convolutional Networks for Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2015, pp. 3431–3440. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, W.; Oates, T. Time Series Classification from Scratch with Deep Neural Networks: A Strong Baseline. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), 2017, pp. 1578–1585. [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); IEEE: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2016; pp. 770–778. [CrossRef]

- van Noord, N.; Postma, E. Learning Scale-Variant and Scale-Invariant Features for Deep Image Classification. Pattern Recognition 2017, 61, 583–592. [CrossRef]

- Balkhi, P.; Moallem, M. A Multipurpose Wearable Sensor-Based System for Weight Training. Automation 2022, 3, 132–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).