Submitted:

19 June 2025

Posted:

23 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Traditional Exercise Volume Assessment Methods

1.2. Multi-Modal Data Fusion in Dynamic Exercise Assessment

1.3. Limitations in Existing Research

1.4. LSTM Networks in Exercise Data Analysis

1.5. Research Gaps and Objectives

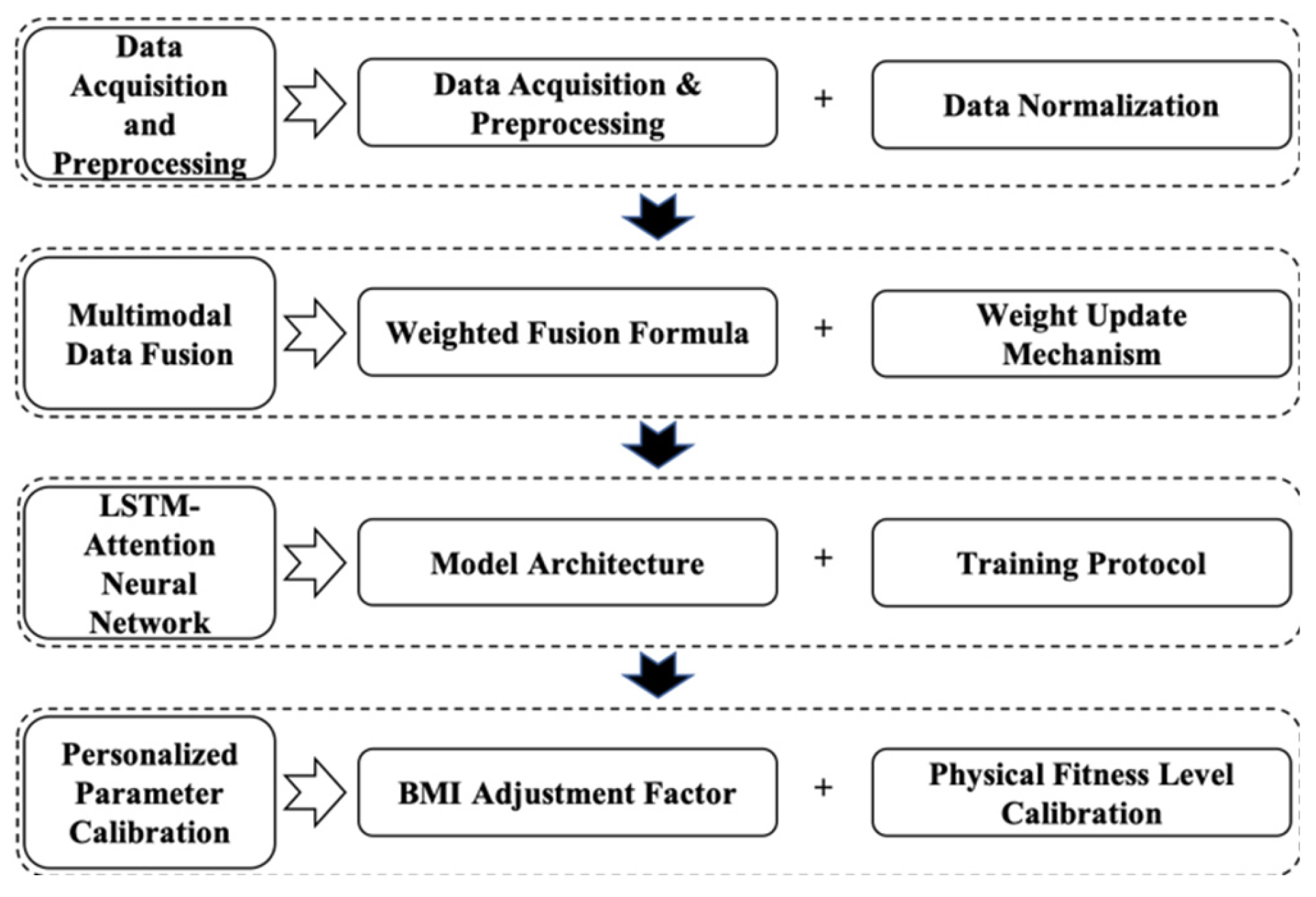

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

2.1.1. Data Sources and Collection

2.1.2. Data Normalization

2.2. Multi-Modal Data Fusion

2.2.1. Weighted Fusion Formula

2.2.2. Weight Update Mechanism

2.3. LSTM-Attention Neural Network

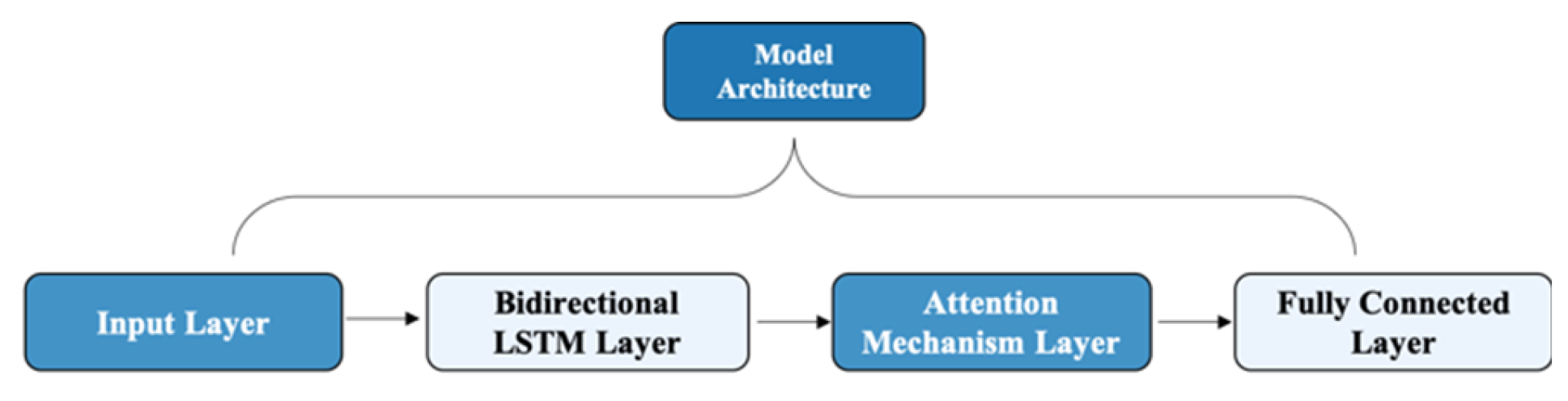

2.3.1. Model Architecture

- Input layer: Time-series data slices (T=60s, D=5 features: %HRR, Acc, Steps, temperature, humidity).

- Bidirectional LSTM layer (128 units): Captures long-term dependencies in motion data.

- Attention mechanism: Computes feature importance via learnable parameters Q, K, V:

- Fully connected layer: Outputs exercise intensity probabilities (low, moderate, high).

2.3.2. Training Strategy

- Loss function: Cross-entropy loss with temporal consistency constraint:

- Optimizer: Adam (, batch size = 32).

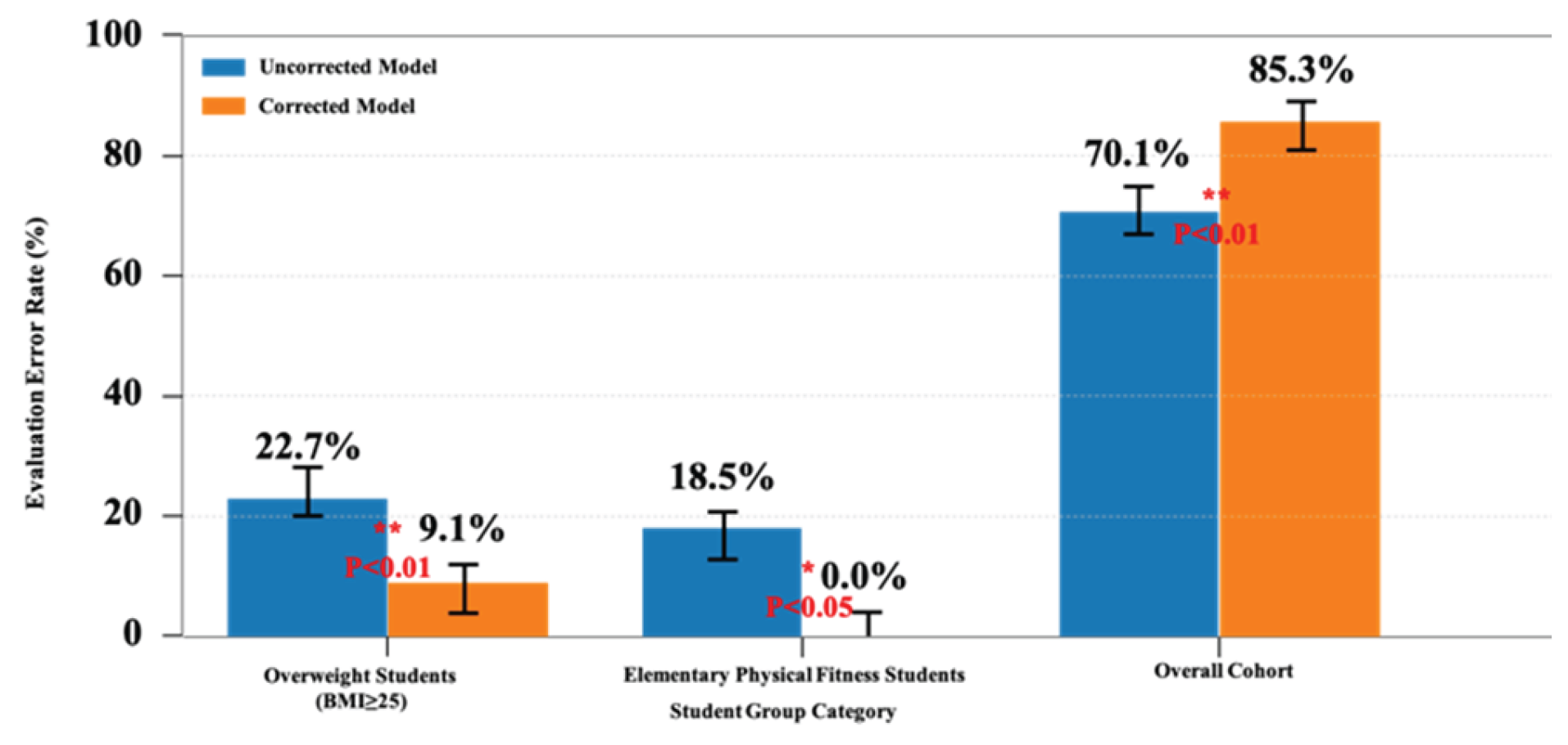

2.4. Personalized Parameter Correction

2.4.1. BMI Correction Factor

2.4.2. Fitness Level Correction

3. Algorithm and System Design

3.1. System Architecture

3.1.1. Data Acquisition Module

- Hardware configuration: Smartwatches (collecting heart rate, acceleration). Foot-mounted inertial measurement units (IMUs, capturing gait and jump height). Environmental sensors (monitoring temperature and humidity).

- Real-time transmission protocol: Synchronization via BLE and Wi-Fi 6 with a unified sampling rate of 50 Hz. Timestamp alignment error controlled within ±10 ms.

3.1.2. Multi-Modal Fusion Computing Unit

- Feature alignment: Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) resolves sampling rate discrepancies (e.g., 1 Hz heart rate vs. 50 Hz acceleration).

- Spatio-temporal fusion: A modified Transformer architecture (with positional encoding) integrates physiological signals (HR), kinematic parameters (acceleration, step frequency), and environmental data. Output: Joint feature vector F∈RT×D (T=60 second time window, D=8 dimensional features).

3.1.3. Personalized Correction Engine

- BMI adapter: Adjusts intensity thresholds based on WHO BMI categories (underweight, normal, overweight). Example: Overweight individuals’ moderate-intensity HR upper limit reduced by 5%.

- Fitness-level classifier: K-means clustering (k=3k=3) categorizes users into beginner/intermediate/advanced levels using historical data (e.g., VO2maxVO2max, lactate threshold).

3.1.4. LSTM-Attention Model

- Temporal modeling layer: Bidirectional LSTM (128 hidden units) captures long-term dependencies in motion sequences. Dropout rate = 0.3 to prevent overfitting.

- Adaptive attention layer: Multi-head attention (4 heads) focuses on critical exercise phases (e.g., basketball sprint intervals). Attention weights A∈RT×T normalized via Softmax.

3.1.5. Dynamic Feedback Generation Module

- Rule engine: Predefined exercise volume-target mapping table (e.g., fat loss requires ≥60% time in moderate-to-vigorous intensity).

- Real-time recommendation algorithm: Triggers voice prompts (e.g., “Increase defensive running frequency”) if target intensity is unmet for 5 consecutive minutes.

3.2. Algorithm Workflow

3.2.1. Data Preprocessing

- Outlier removal: Discards HR data exceeding

- Normalization: Acceleration Z-score normalization

3.2.2. Exercise Intensity Classification

- Time-series input: 60-second windows fed into the LSTM-Attention model. Output: Probability distribution

- Classification rules: , High intensity. sustained for ≥3 minutes, Prolonged moderate intensity.

3.2.3. Personalized Correction

- BMI correction: Overweight users (BMI≥25): High-intensity threshold scaled by

- Fitness-level compensation: Beginners receive a 15% weighted adjustment to prevent underestimation:

3.2.4. Exercise Volume Evaluation and Feedback

- Composite score:

- Dynamic feedback: If real-time score < 80% target: Suggests tailored actions (e.g., “Add 2 sets of full-court fast breaks”). If HR recovery rate < 20% historical average: Triggers rest alerts.

4. Experimental Design and Data Analysis

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Participants and Data Collection

- Polar Verity Sense (armband for heart rate monitoring).

- Shimmer3 IMU sensors (motion tracking).Data were collected over an 8-week period during three weekly training sessions (90 minutes each), including:

- Physiological data: Real-time heart rate (HR), resting heart rate (RHR), and heart rate variability (HRV).

- Kinematic data: Triaxial acceleration (±16g range, 50 Hz sampling rate), step count, and jump count (detected via thresholding).

- Environmental data: Court temperature and humidity (SHT35 sensor, 1 Hz sampling rate).

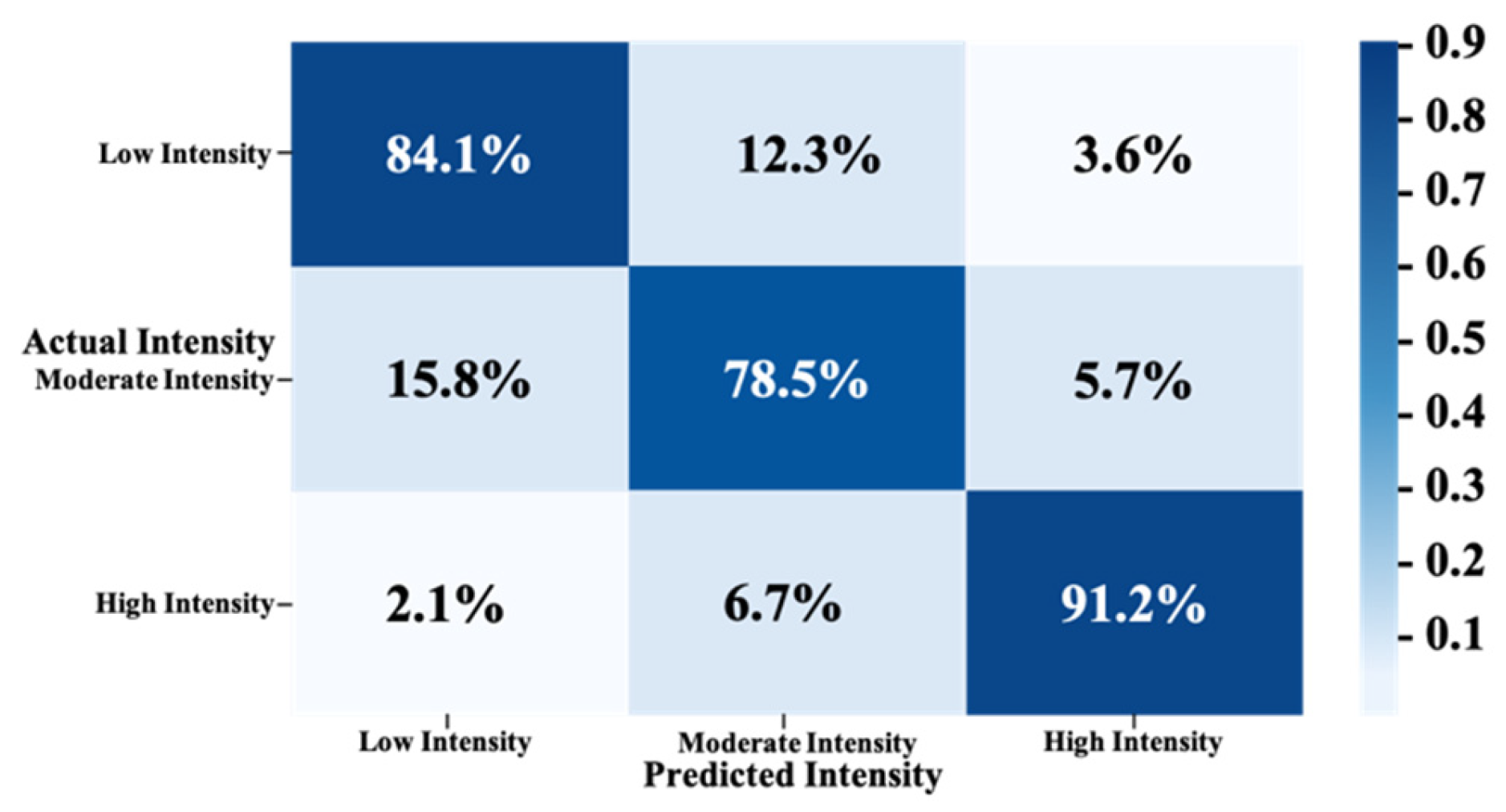

4.1.2. Exercise Intensity Grading Criteria

- Low intensity (0): %HRR<40% OR acceleration vector magnitude (VM) <0.5g (e.g., stationary shooting, slow dribbling).

- Moderate intensity (1): 40%≤%HRR<70% and 0.5g≤VM<1.2g (e.g., tactical positioning, moderate-speed defense).

- High intensity (2): %HRR≥70% AND VM≥1.2g (e.g., fast-break sprints, high-intensity confrontations).

4.1.3. Data Partitioning and Model Training

4.2. Experimental Results

4.2.1. Exercise Intensity Classification Performance

4.2.2. Validation of Personalized Correction Effectiveness

4.2.3. Impact of Dynamic Feedback Strategy

5. Discussion

5.1. Innovations

5.1.1. Spatiotemporal Attention-LSTM Advantages

5.1.2. Multimodal-Personalization Synergy

- Data-level: Adaptive weighting of complementary modalities (heart rate for metabolic load, acceleration for mechanical load) boosts F1-score by 19.8%. This aligns with Tabata training studies where heart rate-acceleration-machine learning fusion improves energy expenditure prediction [36] and multimodal signal fusion (e.g., ECG, accelerometry) enhances robustness [37,38].

- Individual-level: Dynamic coupling of BMI correction and fitness compensation addresses physiological heterogeneity (e.g., 23% faster heart rate rise in overweight individuals). Obesity alters heart rate metrics’ associations with fitness levels [39], while replacing sedentary behavior with moderate-to-vigorous activity optimally improves cardiometabolic health in overweight youth [40]. These findings underscore the necessity of BMI-personalized exercise prescriptions.

5.2. Research Limitations

5.2.1. Data Scale and Diversity Constraints

5.2.2. Hardware Accuracy and External Interference

5.3. Future Research Directions

5.3.1. Cross-Population Generalization Enhancement

5.3.2. Algorithm Fusion and Real-Time Optimization

5.3.3. Edge Computing and System Lightweighting

6. Conclusions

6.1. Key Findings

6.1.1. Model Performance Breakthrough

6.1.2. Multimodal Fusion Benefits

6.1.3. Personalization Effectiveness

6.2. Practical Implications

6.2.1. Instructional Optimization

6.2.2. Health Management

6.2.3. Paradigm Innovation

6.3. Potential for Further Research

6.3.1. Cross-Disciplinary Generalization

6.3.2. Enhanced Data Dimensions

6.3.3. Algorithm Innovation

References

- Iannetta, D.; Keir, D.A. , and F. Y. Fontana. Evaluating the accuracy of using fixed ranges of METs to categorize exertional intensity in a heterogeneous group of healthy individuals: Implications for cardiorespiratory fitness and health outcomes. Sport. Med. 2021, 51, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pina, I.; Ndagire, P. , and W. Katagira. Deriving personalised physical activity intensity thresholds by merging accelerometry with field-based walking tests: Implications for pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron. Respir. Dis. 2022, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colosio, A.L.; Spigolon, G. , and E. Bacchi. Monitoring exercise intensity in diabetes: Applicability of ‘heart rate-index’ to estimate oxygen consumption during aerobic and resistance training. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2019, 42, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valderas, M.T.; Bolea, J. , and P. Laguna. Mutual information between heart rate variability and respiration for emotion characterization. Physiol. Meas. 2019, 40, 035001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrame, T.; Amelard, R. , and A. Wong. Prediction of oxygen uptake dynamics by machine learning analysis of wearable sensors during activities of daily living. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z. , and G. Zhao. Assessment of lumbar disc herniation-impaired gait by using IMU data fusion method. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 27, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procházka, A.; Vaseghi, S. , and M. Yadollahi. Remote physiological and GPS data processing in evaluation of physical activities. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2013, 51, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Falkenström. Time-lagged panel models in psychotherapy process and mechanisms of change research: Methodological challenges and advances. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 109, 102435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, W.C.; Arizmendi, C. , and K. M. Gates. Personalized models of psychopathology as contextualized dynamic processes: An example from individuals with borderline personality disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2020, 88, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. McNeish and T. Matta. Differentiating between mixed-effects and latent-curve approaches to growth modeling. Behav. Res. Methods 2017, 49, 2077–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaroug, A.; Garofolini, A. , and D. T. H. Lai. Prediction of gait trajectories based on the Long Short Term Memory neural networks. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.; Du, G. , and Z. Li. Multimode Gesture Recognition Algorithm Based on Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory Network. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 4068414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, P.; Urpi, N.A. , and M. Lebedev. Decoding Movements from Cortical Ensemble Activity Using a Long Short-Term Memory Recurrent Network. Neural Comput. 2019, 31, 1325–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefever, J.; Berckmans, D. , and J. Aerts. Time-variant modelling of heart rate responses to exercise intensity during road cycling. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2014, 14, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalfa, N.; Bertrand, P.R. , and G. Boudet. Heart rate regulation processed through wavelet analysis and change detection: Some case studies. Acta Biotheor. 2012, 60, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, M.I.; Mbambo, Z.H. , and A. St Clair Gibson. Heart rate during training and competition for long-distance running. J. Sports Sci. 2012, 16, S49–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. R. Wessel. β-Bursts Reveal the Trial-to-Trial Dynamics of Movement Initiation and Cancellation. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 8783–8795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Gray. Changes in Movement Coordination Associated With Skill Acquisition in Baseball Batting: Freezing/Freeing Degrees of Freedom and Functional Variability. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Malla, C.; López-Moliner, J. , and E. Brenner. Seeing the last part of a hitting movement is enough to adapt to a temporal delay. J. Vis. 2012, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, T.C.B.; Valente, L.M. , and D. C. Sobral Filho. Relation between heart rate recovery after exercise testing and body mass index. Rev. Port. Cardiol. 2015, 34, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, R.P.; Castello-Simões, V. , and R. G. Mendes. Lactate and heart rate variability threshold during resistance exercise in the young and elderly. Int. J. Sports Med. 2013, 34, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortelainen, L.; Helske, J. , and T. Finni. A nonlinear mixed model approach to predict energy expenditure from heart rate. Physiol. Meas. 2021, 42, 035003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Y. Yan and Q. Chen. Energy Expenditure Estimation of Tabata by Combining Acceleration and Heart Rate. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 804471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, G.R.; Fisher, G. , and D. R. Bryan. Divergent Blood Pressure Response After High-Intensity Interval Exercise: A Signal of Delayed Recovery? J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 1356–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, M.M.; Palumbo, E. , and R. F. Seay. Energy compensation after sprint- and high-intensity interval training. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O.G.; Boubeta, A.R. , and E. Real Deus. Using heart rate to detect high-intensity efforts during professional soccer competition. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 1303–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeukendrup and, A. VanDiemen. Heart rate monitoring during training and competition in cyclists. J. Sports Sci. 2012, 16, S91–S99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonderegger, K.; Tschopp, M. , and W. Taube. The Challenge of Evaluating the Intensity of Short Actions in Soccer: A New Methodological Approach Using Percentage Acceleration. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simim, M.A.M.; de Mello, M.T. , and B. V. C. Silva. Load Monitoring Variables in Training and Competition Situations: A Systematic Review Applied to Wheelchair Sports. Adapt. Phys. Activ. Q. 2017, 34, 456–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Ko, J.E. , and S. Baek. Improving Fall Classification Accuracy of Multi-Input Models Using Three-Axis Accelerometer and Heart Rate Variability Data. Sensors 2025, 25, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Gilmore and M. Nasseri. Human Activity Recognition Algorithm with Physiological and Inertial Signals Fusion: Photoplethysmography, Electrodermal Activity, and Accelerometry. Sensors 2024, 24, 3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Yang, L. , and F. Seoane. Fusion of Heart Rate, Respiration and Motion Measurements from a Wearable Sensor System to Enhance Energy Expenditure Estimation. Sensors 2018, 18, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Zhang, L. , and L. Yang. Redundancy and Attention in Convolutional LSTM for Gesture Recognition. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 31, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Cheng, C. , and M. Zhao. EEG-Based Emotion Recognition Using Spatial-temporal Graph Convolutional LSTM with Attention Mechanism. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 27, 3425–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Gui, Z. , and Z. Zhang. A hierarchical temporal attention-based LSTM encoder-decoder model for individual mobility prediction. Neurocomputing 2020, 403, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y. Yan and Q. Chen. Energy expenditure estimation of Tabata by combining acceleration and heart rate. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 804471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dsilva, L.A.; Cardew, A. , and L. Qasem. Relationships between oxygen uptake, dynamic body acceleration and heart rate in humans. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2014, 54, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jeon, T.; Yu, J. , and W. Pedrycz. Robust detection of heartbeats using association models from blood pressure and EEG signals. Biomed. Eng. Online 2016, 15, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhu, L. , and Z. Chen. The effect of different intensity physical activity on cardiovascular metabolic health in obese children and adolescents: An isotemporal substitution model. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1041622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneni, E.C.; Oni, E.T. , and C. U. Osondu. Obesity modifies the effect of fitness on heart rate indices during exercise stress testing in asymptomatic individuals. Cardiology 2015, 131, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metric | Experimental Group (n = 50) | Control Group (n = 50) | Improvement | Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goal Achievement Rate | 89.4% | 79.1% | +10.3% | 0.003 |

| % Time in Moderate-to-Vigorous Intensity | 73.0% | 58.3% | +14.7% | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).