1. Introduction

Since the discovery of green fluorescent protein (GFP) in jellyfish by Shimomura and colleagues in 1962, this remarkable protein has enabled the visualization of various proteins within cells, allowing for flexible observation of gene expression and protein dynamics [

1]. Concurrently, efforts to visualize other macromolecules within organisms have gradually emerged. While proteins have been extensively studied in this context, RNA, an equally vital component in biology, presents challenges due to its complex species and structures, as well as its intricate spatio-temporal localization. Thus, the development of a simple and effective RNA tracing tool represents a promising research direction. In 2011, Spinach, an RNA fluorescent complex that mimics the GFP principle and exhibits similar functionalities, was introduced to fill the gap in RNA fluorescent labeling, and over the past decade, numerous researchers have leveraged this technology to overcome various challenges associated with RNA tracing [

2].

Both GFP and Spinach are potent bioimaging tools in botanical research, allowing for the elucidation of various mysteries surrounding plant growth and development, material metabolism, and regulatory mechanisms. Compared to animal cells, plant cells contain numerous natural fluorescent components, such as chlorophyll in chloroplasts and lignin in cell walls, which pose significant challenges for plant cell bioimaging. Moreover, Aggregation-Caused Quenching (ACQ) is a common issue with the use of conventional fluorescent substances, while GFP, as a protein with large molecular weight and low resolution, cannot directly penetrate the cell membrane, and current mature RNA fluorescent probes, such as Spinach, are complex to operate. Thus, the development of a novel RNA fluorescent probe is essential to address these issues.

Currently, Aggregation-induced emission luminogens (AIEgens) are emerging as promising fluorescent probes for in vivo animal and medical applications, but they have yet to be widely studied in phycology. AIE materials possess adjustable luminescence properties, tunable molecular size, high fluorescence intensity, excellent photostability, and low cytotoxicity, compared to conventional fluorescent materials [

3]. The application of AIE to plant RNA fluorescent labeling technology holds great promise for addressing the aforementioned challenges in this field.

2. Currently established RNA labeling tools

2.1. RNA category and functions

When messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) was discovered at the very beginning, it was thought to be a temporary transition carrying genetic information from DNA to protein [

4]. Transfer RNA (tRNAs), generally containing CCA-3' end [

5], was first discovered by Hoagland et al. [

6], consists of about 76 nucleotides and binds to ribosomes, pairs with mRNA codons, and carries amino acids [

7,

8]. Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) is an important part of ribosome composition. Which is the most abundant RNA in living organisms and the first discovered non-coding RNA (ncRNA) [

9].The microRNA (abbreviated miRNA) (18-24 nt) was discovered in 1993 [10-12]. As a component of RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), when miRNA is complementary to mRNA the target mRNA is degraded with the action of RSIC [

13]. In some cases, miRNAs can also activate gene expression and increase the level of protein translation [

14,

15].Subsequent confirmed long non-coding RNAs (long ncRNAs, lncRNA), commonly have more than 200 nucleotides, can regulate gene expression at multiple levels [

16].The discovery of double strand RNA (20-24 bp) is a subversive achievement in the RNA field. It can interfere with the expression of an endogenous gene [

17]. This special kind of RNA has the function of gene regulation. Synthetic 21-nucleotide siRNA duplexes were subsequently confirmed specifically suppress the expression of endogenous and heterologous genes in different mammalian cell lines [

18]. In Xenopus oocytes, Vg1 mRNA is steadfastly localized at the vegetal cortex [

19].The polarized localization of RNA within the cell means that the distribution of RNA within the cell is not uniform [

20]. Research in the worm C. elegans and in other animals has also revealed RNA cell-to-cell movement [

21]. In addition to animals, RNA in plants also has the characteristics of long-distance movement [

22].Combined with the inhibitory effect of exogenous double-stranded RNA on gene expression in organisms, RNA mobilization is the last piece of the puzzle in the development of gene medicines in the future.

2.2. RNA Tracing methods

Figuring out RNA moving is not an easy task. RNA imaging is believed the starting point to present possible moving regulatory mechanisms. To track the trajectory of RNA movement, there are two commonly used methods. One is based on fluorescent proteins and the other is based on RNA aptamers.

2.2.1. GFP fused to targeting RNA

The coat protein of RNA bacteriophage MS2 can interact with a stem-loop structure from its phage genome [

23]. Integration of the visualization of green fluorescent protein (GFP), and the RNA-binding function of MS2, MS2-GFP is often used to label RNA localization in living cells [23-27]. However, the obvious disadvantage of this method is that the 5' or 3' end of the target RNA needs to be connected to the stem-loop structure RNA recognized by the MS2 coat protein.

2.2.2. Aptamer-based RNA labeling

Although the use of fluorescent proteins to indirectly label RNA is successful, there is still a certain gap from the high efficiency. It may be another effective way to enable RNA to emit light through the light-emitting principle of GFP. This requires a review of the discovery history and luminescence mechanism of GFP protein.

In 1961, Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) was first coincidentally

discovered by Osamu Shimomura as a byproduct when he

tried to separate aequorin from

Aequorea 3ictoria [

1]. To figure out this bioluminescent protein, he analyzed

its constituents. Like GFP of pansy

Renilla, he found

Aequorea GFP

also contains chromophore otherwise amino acids [

28].

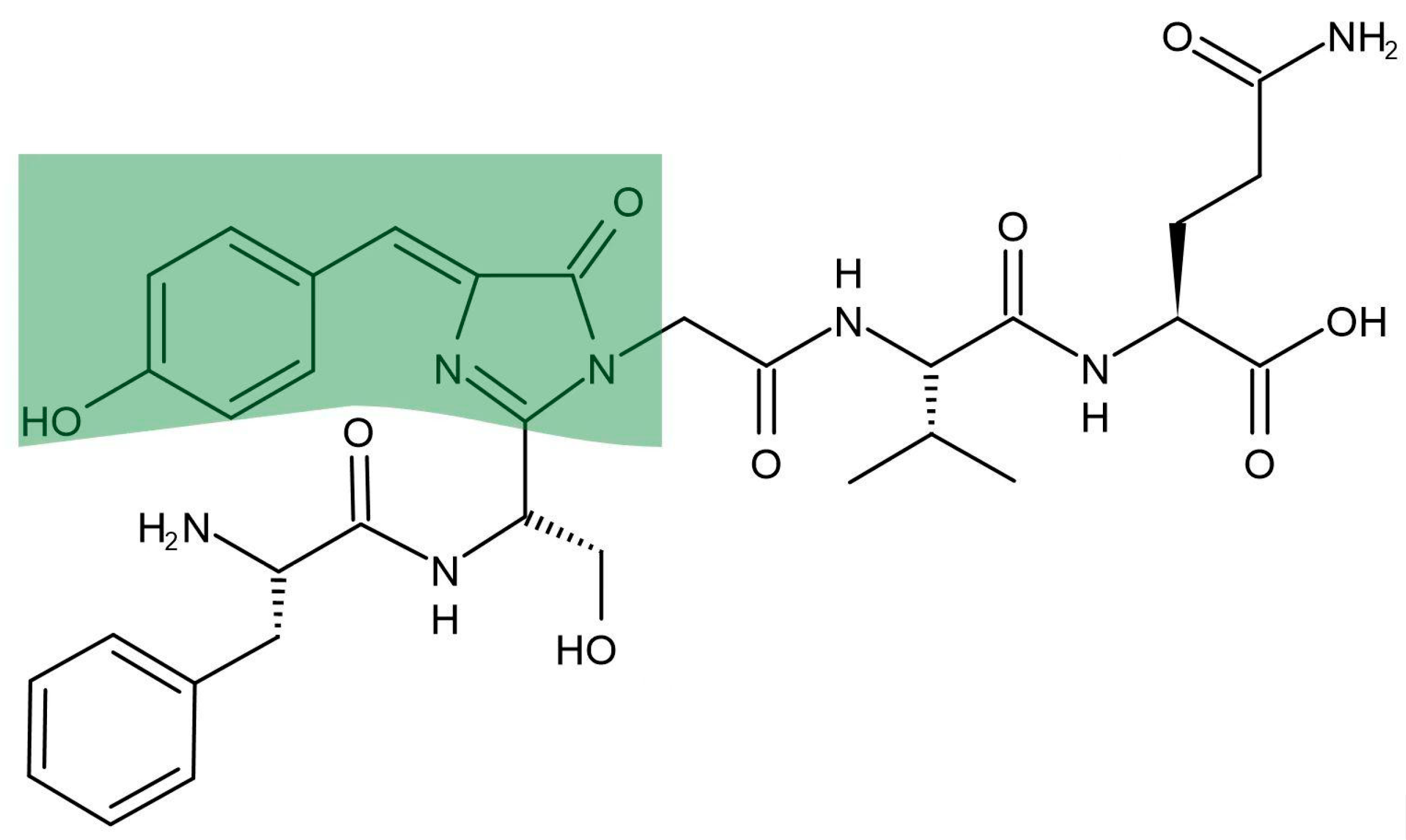

The chromophore molecular 4-(p- hydroxybenzylidene)-5-imidazolone moiety that Osamu

Shimomura proposed was not exactly right [

29].

The real chromophore in

Aequorea GFP is showed in

Figure 1 [

29]. The green part in

Figure 1 is GFP’s photochemistry

as the model compound that is usually synthesized to mimic the proteins chromophore.

The chromophore in

Figure 1 is spontaneously cyclized and oxidized by GFP Ser65-Tyr66-Gly67 three amino acids which is protected by GFP protein inside [30-31]. A cylinder like GFP comprises 11 beta-sheet strands and an alpha-helix [

31]. This unique structure has contributed to some inside modifications that can lead to various variants other than GFP [

31].

SELEX (

Systematic

Evolution of

Ligands by

Exponential Enrichment) is a powerful tool for screening biological target molecules from libraries. It can solve some fundamental biological questions surrounding DNA or RNA. These DNAs or RNAs are also called aptamers [

32]. These aptamers, in the form of oligonucleotides, are single-stranded DNAs or RNAs that specifically bind to a target ligand or ligands [

33,

34].

To mimic the green fluorescent protein

, Paige et al. [

2] screened the RNA library containing about 5 × 10

13 RNA molecules by SELEX based on the light emission principle of GFP. The HBI is a fluorophore in GFP which is encased within the protein. To avoid interference from GFP, they decided to start with HBI derivatives to screen aptamers for glowing RNA [

2]. They started from several HBI derivatives, after ten rounds of selection, they finally found several aptamer-induced fluorescence RNA candidates. They have very different spectral properties [

2]. Unfortunately, after cell experiments, it was finally confirmed that only 3,5-difluoro-4-hydroxybenzylidene imidazolinone (DFHBI) with 24-2 and 3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxybenzylidene imidazolinone (DMHBI) with 13-2 two pairs have the effect of RNA fluorescence at the cellular level [

2].

In following cell experiments, it was found that after Spinach binds to the target RNA, the fluorescence signal will be weakened. So, Jaffrey’s group continued to optimize the structure of Spinach and then updated version Spinach 2 [

35] and Broccoli [

36]. As for Broccoli, the fluorophore is DFHBI-1T [

36]. Although multiple versions of RNA aptamers had been developed, the phenomenon of photobleaching has been a major bottleneck for the widespread application of this technique. Using the same strategy, Chen et al. [

37] also developed a green fluorescent aptamer RNA named Pepper. Another one named 3WJ-4 × Bro was derived from Broccoli [

38]. It is worth mentioning that this is the first time that RNA fluorescence based on RNA aptamers has been successfully observed in plants. In addition, yellow and red RNA fluorescent aptamers had also been developed [

39,

40]. More details are presented in

Table 1.

3. Aggregation-Induced Emission

AIEgens have been widely utilized as fluorescent labels in the animal and medical fields due to their historical development and luminescence mechanism. However, theiruse in plant science has been relatively limited, making it essential to review the luminescence mechanism of AIE for the development of novel plant RNA fluorescent markers.

3.1. ACQ effect limits the application of traditional fluorescent materials

In order to understand the mechanism of aggregation-induced luminescence, it is necessary to first comprehend the aggregation-caused-quenching (ACQ) effect of conventional luminescent materials in highly concentrated solutions or solid states, as well as the challenges posed by ACQ in practical applications. Structurally, conventional fluorescent chromophores are typically rigid planar molecules in a large π-conjugated system composed of planar aromatic rings, which emit strong fluorescence when isolated in solution but can weaken or even disappear due to molecular aggregation at high concentrations, a phenomenon known as the ACQ effect. At the molecular level, the stacking of planar aromatic rings increases the degree of π-π coupling between molecules, leading to a significant reduction in luminescence due to energy transfer between low-energy molecules and high-energy molecules via nonradiative leaps [

43,

44].

The ACQ effect has a significant impact on practical applications, and although many laboratories have conducted long-term studies employing various physical methods and chemical reactions to hinder the aggregation of conventional fluorescent chromophores in solution, such as linking branched chains and attaching bulky ring-likeunits, theseefforts have yielded only limited success and have created new problems, with mostapproaches only partially changing the properties of traditional chromophores and failing to address the issue fundamentally [

45].

3.2. The development of AIEgens

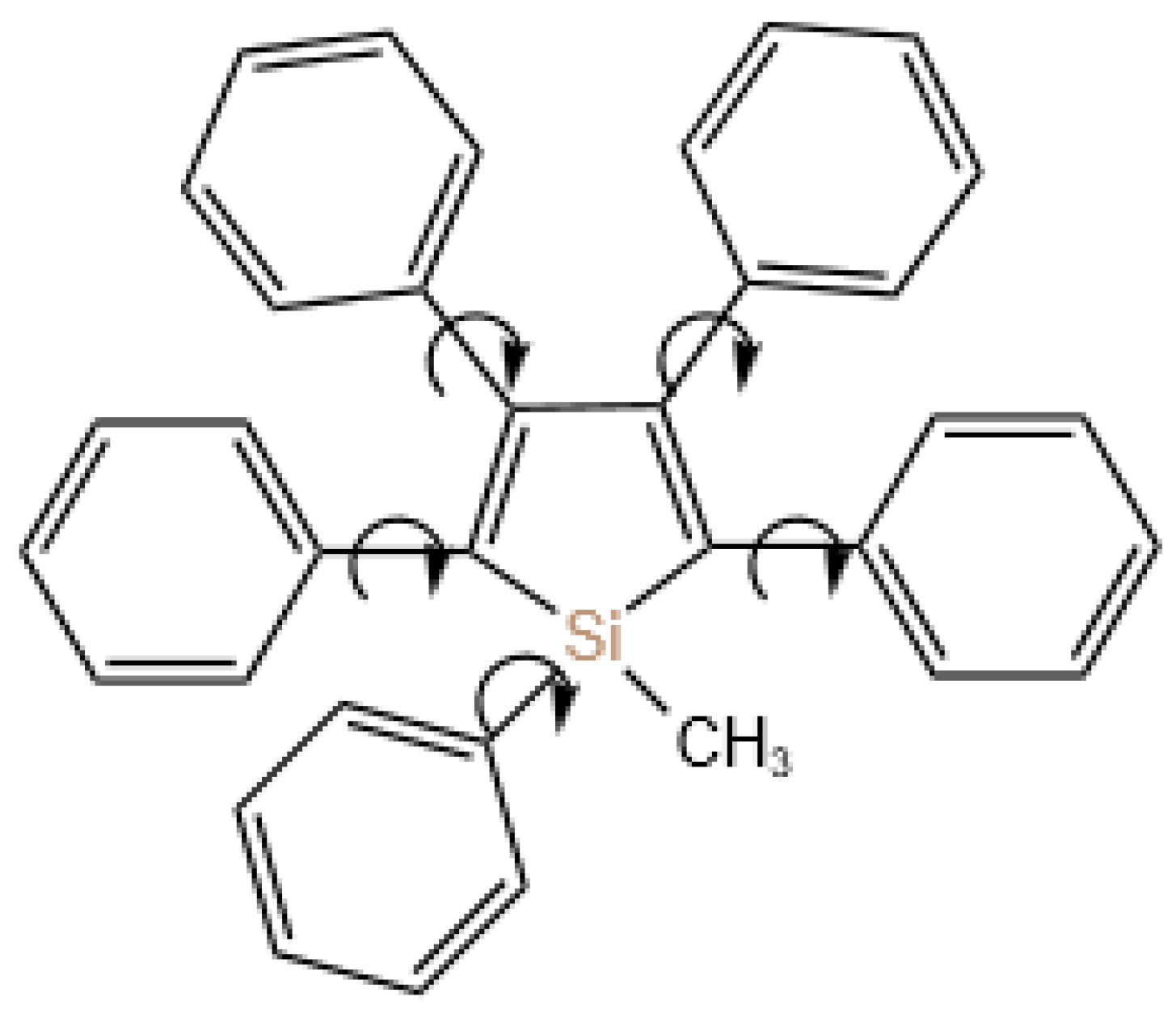

Since the proposal of the ACQ effect by T. Förster et al. in 1954, this problem has remained a challenge for many scientists, until the discovery of the AIE effect by Luo et al. in 2001 (

Figure 2). In their study of the molecule siloles, the isolation and dropping of 1-methyl-1,2,3,4,5-pentaphenylsilole in solution on a thin-layer chromatography plate resulted in no significant luminescence under UV light. However, the lack of luminescence was not observed in the dried position of the solution, which led to the discovery of the AIE effect resulting from intra-molecular rotation restriction (RIR), marking the beginning of a fundamental solution to the ACQ problem [

46,

47].

Since the initial discovery of AIE in polyphenyl-substituted silicone derivatives, a range of representative compounds such as tetraphenylethylene (TPE) and 9,10-stilbenylanthracene (DSA), as well as low-biotoxicity natural AIE effect molecules extracted from plants, such as riboflavin [

48], mulberry pigments [

49], mangiferin [

50] and haematoxylin [

51] have been widely developed. Additionally, many AIE derivative systems have emerged, including aggregation-induced phosphorescence (AIP) [

52], crystallization-induced luminescence (CIE) [

53], and crystallization-induced phosphorescence (CIP) [

54,

55], providing researchers with a broad range of options for future applications.

While AIE has been widely used in bioimaging, medical diagnosis, and other fields,its application in plant research remains limited. As AIE technology continues to mature,it is essential to explore its potential in botanical research, particularly in the development of fluorescent probes that can be applied in plants. This presents not only an opportunity to enhance the existing fluorescent probe system but also a chance to challenge traditional paradigms in fluorescent probe development.

3.3. The luminescence mechanism of AIEgens

Over the 22 years of AIE development, several theories have been proposed on the mechanism of AIE luminescence, with some focusing on intramolecular action caused by the structure of the molecule itself, while others concentrate on intermolecular action resulting from the interaction of molecules when they are stacked. There are six typical mechanisms of AIE luminescence, including restricted intramolecular motion, intramolecular coplanarity, non-compact stacking, formation of J-aggregates, inhibition of photophysical processes or photochemical reactions, and formation of specific radical conjugates.

TPE, a typical class of AIE molecules, contains a rotatable benzene ring in its structure, and the excited state energy can be consumed through the rotation of the benzene ring in a non-radiative way, resulting in weak fluorescence. However, when the molecule is in a high concentration or solid state, the peripheral rotatable aromatic group is limited in rotation due to spatial site resistance, and the excited state of the molecule can only decay back to the ground state through the radiation pathway, significantly enhancing luminescence. Additionally, TPE derivatives such as THBDBA and BDBA do not have rotatable benzene rings like the typical molecule of AIE, TPE, but have AIE effects because their excited state energy can be consumed through the vibration of benzene rings by non-radiative pathways, and fluorescence is enhanced when intermolecular aggregation prevents this vibration. These two mechanisms are combined as intramolecular rotational restriction (RIR) and intramolecular vibrational restriction (RIV) [

56,

57].

While most other AIE mechanisms complement or act in conjunction with the intramolecular motor restriction mechanism, it remains the most maturely designed mechanism upon which AIE materials are based. Therefore, it is crucial to consider this key mechanism when studying fluorescent probes for biomolecules.

4. Application of AIEgens as a fluorescent probe and possibilities for RNA labeling in plants

As a groundbreaking class of organic luminescent materials, AIE compounds have successfully overcome the limitations of traditional fluorescent dyes by avoiding the ACQ effect while retaining their advantages, such as simplicity of operation, high sensitivity, remarkable selectivity, and excellent spatial and temporal resolution [

58]. Due to its significant implications for human health and agriculture industries, the biological field is gaining more attention, and it is undoubtedly the most promising arena for AIE to make a significant impact.

4.1. Application of AIEgens in animal and medical

4.1.1. Probes for Drug Screening

Numerous neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Parkinson's disease (PD), are associated with amyloid self-assembly [

59,

60]. For instance, β-amyloid (Aβ) is a crucial pathogenic factor in AD that disrupts synaptic plasticity and mediates synaptic toxicity through various mechanisms, whereas PD is linked to the amyloidogenesis of α-synuclein (αSN) [

61,

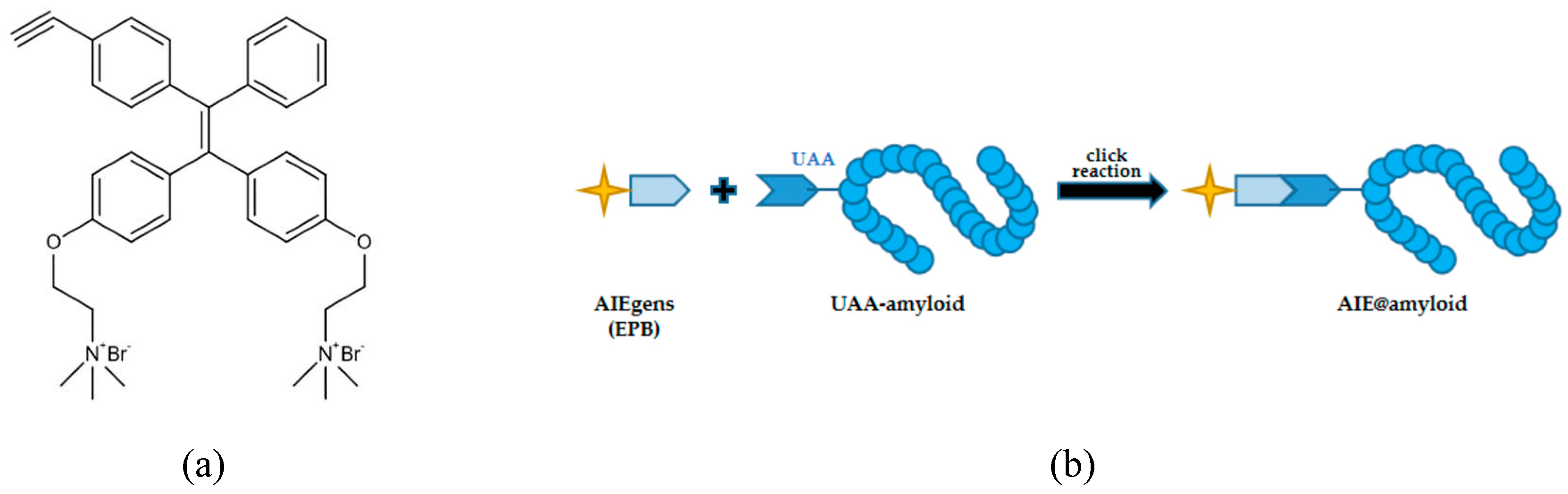

62]. To screen general amyloid inhibitors against different amyloid proteins, Jia et al. (2020) designed AIE@amyloid, an AIE-based amyloid inhibitor probe [

60]. This probe is comprised of an AIEgen (EPB in this study) and an amyloid protein connected with an unnatural amino acid (UAA) (

Figure 3). When amyloid aggregates, the probes also aggregate and emit strong fluorescence. However, in the presence of amyloid inhibitors, the amyloidogenesis of amyloid is prevented, resulting in the failure of the probes to aggregate and the absence of observable fluorescence.

4.1.2. Probes for Micromolecular Biomarkers

Micromolecules play an important role as biomarkers in various diseases, making their detection crucial for disease diagnosis [

58].

Hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

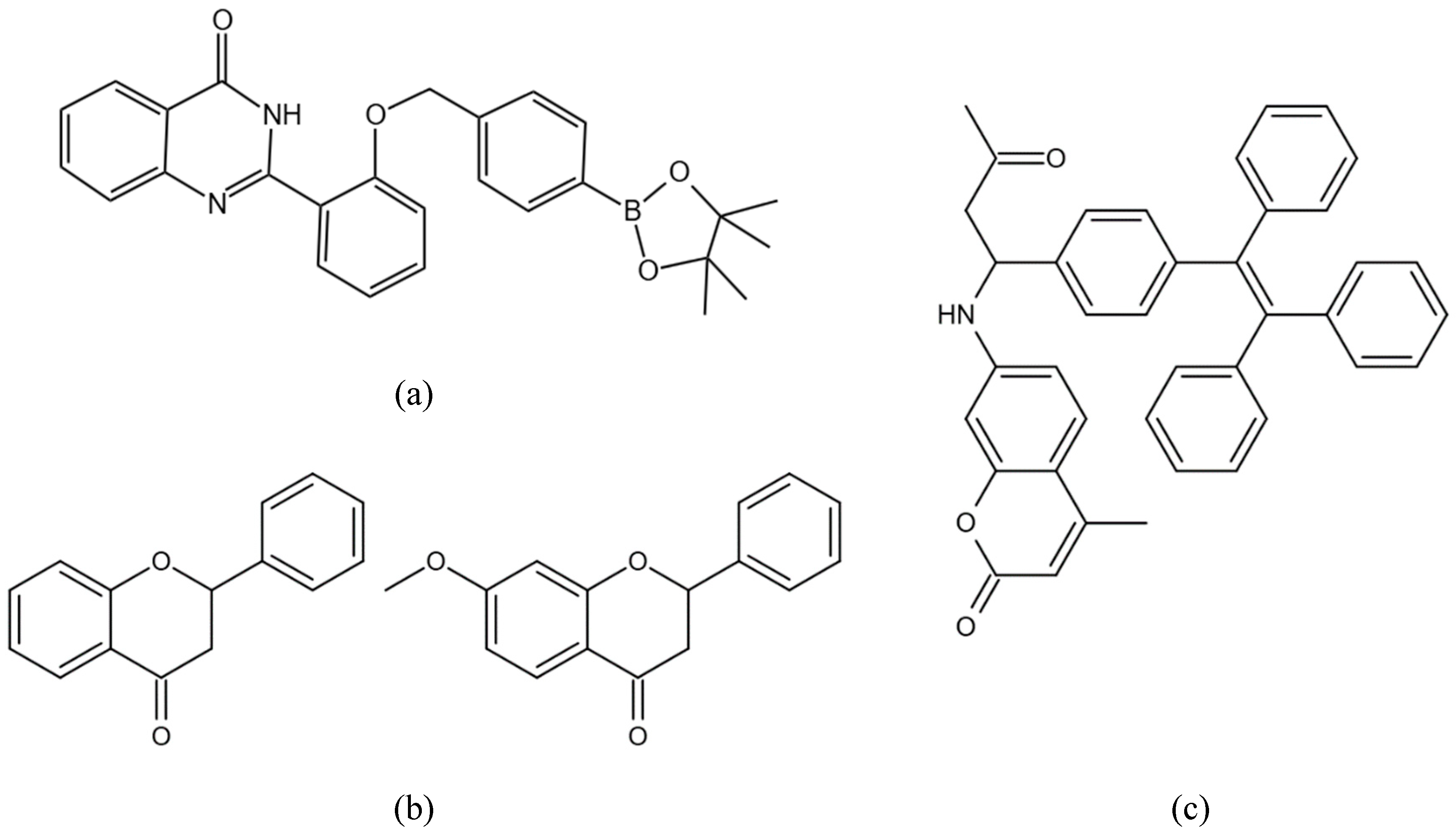

2) and glucose are two such micromolecules that are closely associated with many diseases and can be used as biomarkers [63-66]. In a recent study, Wang et al. developed an AIE-based probe, HPQB, for the detection of H

2O

2 and glucose

(Figure 4a) [

67]. The probe is composed of hydroxyphenylquinazolinone (HPQ), which exhibits typical AIE properties, but its fluorescence is quenched by the presence of benzyl boronic pinacol ester. The reaction of H

2O

2 with HPQB removes the benzyl boronic pinacol ester, thereby restoring the AIE properties of HPQ and enabling the detection of H

2O

2 and glucose. Wang’s study also demonstrated the probe's ability to image nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Reactive oxygen species (ROS), including H

2O

2, play an essential role in plant immunity, and thus the HPQB probe could potentially be used for H

2O

2 labeling in plant cells to determine the occurrence of immune responses.

Glutathione (GSH) is another important micromolecular biomarker [

68]. Xie et al. developed a GSH-activated probe with a disulfide bond as the GSH response motif [

69]. Upon reacting with GSH, the disulfide bond is broken, resulting in the release of the fluorophore and the production of strong fluorescence due to the AIE effect. This probe can be utilized for the detection and imaging of GSH.

4.1.3. Cell Imaging

Visualization of cells or subcellular structures is of great importance in biological research and clinical analysis, as it provides valuable information on bioprocesses at the cellular or molecular level [

70]. Organic fluorescent dyes with excellent optical and biological properties have been widely used in cell imaging to visualize cells or structures [

71]. However, conventional fluorescent dyes are limited by the ACQ effect. AIE compounds,on the other hand, overcome this limitation and have high application value in cell imaging.

Mitochondria, which are the energy centers of cells, produce ATP and heat to support all life activities, and their dysfunction is associated with various diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease [

72]. Li et al. selected two AIE compounds

(Figure 4b) from a series of flavanones [

73]. They found that both compounds showed low cytotoxicity and significant biocompatibility with A549 cells, and were specifically aggregated in mitochondria. Their study suggests that the compounds could have applications in mitochondria imaging of living cells.

Lysosomes, which have diverse functions such as cell digestion, signaling, and generegulation, are associated with numerous diseases such as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [

74]. Lou et al. applied TPE-CA

(Figure 4c), an AIE fluorogen containing tetraphenylethene and coumarin moiety, to lysosome-targeted imaging of living cells [

75]. TPE-CA has a strong emission intensity at lower pH, which gives it lysosomal targ tingproperties. The application of TPE-CA may advance the understanding of the acid environment of lysosomes in related cells and provide a better testbed for cell imaging.

4.2. Application of AIEgens in plants

The utilization of aggregation-induced emission (AIE) in plants is a nascent field of investigation that has garnered significant interest in contemporary times. To date, there have been two major avenues of exploration: firstly, the association of AIE with plant photosynthesis for the purpose of enhancing its efficacy; and secondly, the application of fluorescent labeling to a diversity of constituents within plant cells.

4.2.1. AIEgens enhance the efficiency of photosynthesis in plants

In 2021, Tang and colleagues utilized click chemistry to incorporate two AIEgens, TPE-PPO and TPA-TPO, into living chloroplasts to enhance photosynthetic efficiency. These AIEgens absorb ultraviolet and green light that is typically unavailable to chloroplasts and convert it into blue and red light, which can be used by the chloroplasts [

76]. This pioneering study demonstrated the potential of AIEgens for photoconversion to improve photosynthesis.

Another study by Xiao et al. in 2021 reported a hybrid photosynthetic system that combined chloroplasts with CD-AIEgens, which were made of natural quercetin and designed using nanotechnology. This system was able to capture a wider range of light and improve electron transfer efficiency, resulting in enhanced photosynthesis [

77]. This result was also mentioned in a 2022 review by Tang's team on the efficient use of AIEgens with solar energy.The review analyzed the feasibility of using AIEgens to optimize solar energy utilization systems, focusing on improving light harvesting, solar energy conversion, chemical conversion, and thermal conversion [

78]. A significant focus was on AIEgens and photosynthesis coupling technology, recognizing the importance of AIEgens for enhancing photosynthesis. Another review also examined various methods of using AIEgens to enhance photosynthesis, such as adding AIEgens directly to the medium of cyanobacteria or coupling AIEgens directly with chloroplasts through click chemistry. These findings have important implications for addressing food and energy challenges and promoting sustainable development [

79].

4.2.2. The application of AIEgens as fluorescent labeling in plant science.

Compared to animal cells, plant cells contain more fluorescent substances that interfere with plant bioimaging. Traditional fluorescent dyes suffer from ACQ, which limits their usage at high concentrations to avoid fluorescence quenching, but weak fluorescence at low doses impacts experiments and interferes with multiple imaging with other fluorescent components like GFP. AIEgens have high stability and luminescence intensity, overcoming the limitations of traditional dyes in subcellular localization. Various AIEgen-based fluorescent probes have been developed for detecting plant cell substances. In 2017, Saponin Nanoparticles with AIE properties were used for the first time in Arabidopsis thaliana to fluorescently label plant cell membranes through the cell wall, paving the way for AIEgen studies in model plants [

80]. Lu et al. used Kaempferrol as an AIE fluorescent probe to detect Al3+ in Arabidopsis thaliana roots incubated in a mixture of water and tetrahydrofuran containing Kaempferrol due to the plant's high metal content [

81]. Plant hormones as an essential plant growth regulator, Wu et al. discovered an Abscisic acid (ABA) AIEgens fluorescent probe that can label ABA in the presence of bovine serum albumin (BSA), providing a novel perspective on in vivo or in vitro ABA detection [

82].

5. Outlook

The use of AIEgens fluorescent probes in plants showcases the universality of this technology, as AIEgens-based fluorescent probes have been extensively reported for other biomolecules such as DNA or proteins in animal cells, although their clear applications in plants are yet to be established, except for AIEgens serving as fluorescent markers for RNA. As a nascent technology, the application of AIEgens in plant cells will likely follow a similar path as that of GFP, starting with animal cells and requiring a prolonged optimization process before its widespread application in plant cells.

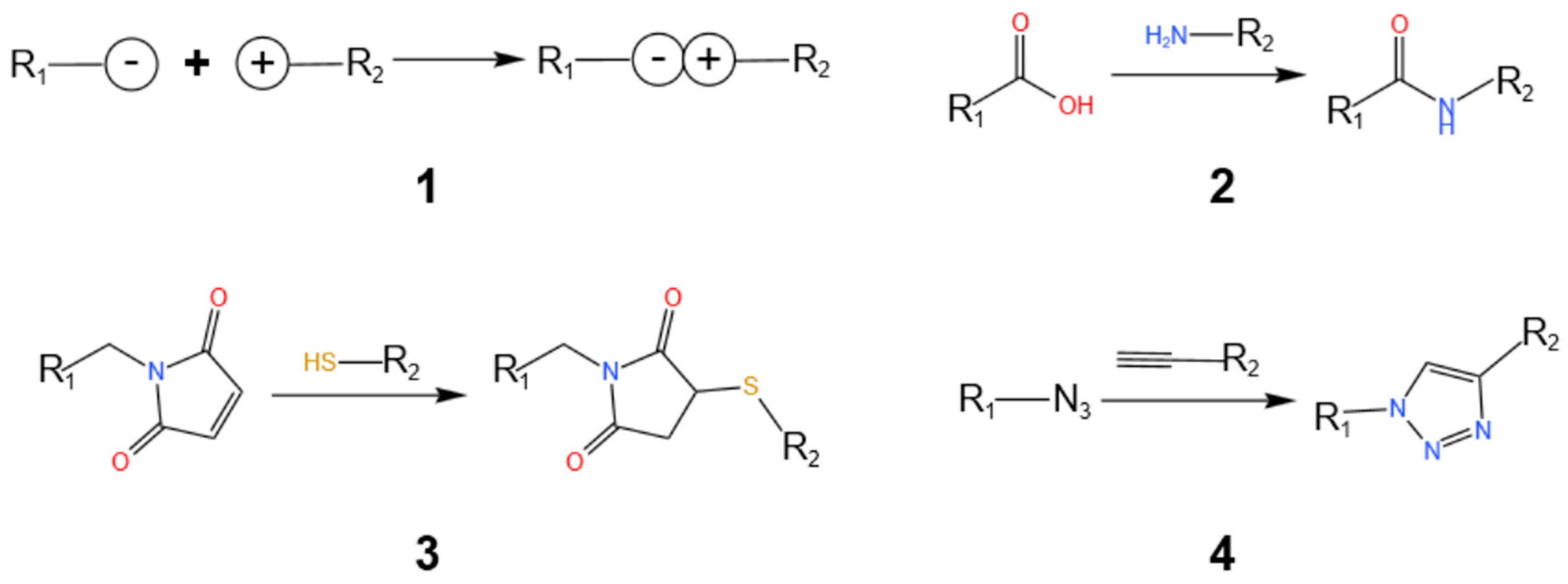

5.1. Click chemistry for AIE labeling RNA

Based on available studies, AIEgens as RNA fluorescent probes in plants show the highest feasibility when using click chemistry. Click chemistry is an efficient method for in vivo biomolecule labeling. The most commonly used organic reaction is the Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition, which utilizes compounds modified with alkyne bonds and organic azides for catalysis by Cu [

83,

84].

Previously, the use of click chemistry in living organisms was greatly limited by theneed for a copper catalyst, which was toxic to bacteria and mammalian cells. However, in 2004, the development of the Strain-Promoted Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition overcame this limitation and allowed for the performance of click chemistry in living animals with out causing physiological damage, demonstrating great potential for non-invasive imaging applications [

85].

In 2008, Jao et al. demonstrated the incorporation of a substance with an alkyne bond, such as 5-ethynyluridine (EU), into mRNA by transcription, followed by copper (I)-catalyzed alkyne-azide cycloaddition using fluorescent azides in living organisms [

86]. This experiment fully demonstrates the feasibility of fluorescent group modification of biomolecules by click chemistry in living organisms.

In 2018, Khatua et al. reported that [Ru(phen)2(4,7-dichloro-phen)] 2+, which contains a halogen bond can attach to nucleolar ribosomal RNA and aggregate luminescence for in situ tracing of nucleolar ribosomes [

87].

Since there are few design cases of RNA and AIE together to form fluorescent probes, however, both RNA and DNA, as nucleic acid biomolecules, have some structural similarities, and the modifications to DNA molecules may be equally applicable to RNA molecules. However, DNA is mostly present in organisms as a double strand, which is again different from RNA that is often present as a single strand. Therefore, more modifications of RNA may be discovered in the future

(Figure 5).

AIE molecules could also be used as reactants to modify RNA in vivo by Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition reaction, such as introducing monosubstituted alkyne groups to RNA probe molecules and reacting with azide-modified AIEgens to achieve in vivo RNA localization for imaging. But, the lack of biological selectivity is a major weak ness of click chemistry, and to efficiently and accurately label AIEgens to RNA, the CRISPR/Cas system may be needed.

5.2. For AIE, CRISPR may be on the way

The discovery of a highly efficient gene editing system from bacteria has ushered in a new era of molecular biology [

88]. The CRISPR/Cas gene editing system is powerful. From the beginning, it only cuts DNA [

88,

89], to develop DNA [

90,

91] or RNA [

92] base substitutions, RNA cut [

93] and label RNA [

94]. Developments around CRISPR-related technologies are still ongoing. But so far, there is no perfect report on the real-time imaging of RNA movement trajectories using the CRISPR/cas system in vivo.

Using inactivated RNA-targeting CRISPR/dCas13 fused with ADAR2 (Adenosine deaminases Adenosine deaminases that act on RNA), RNA adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) and cytidine-to-uridine (C-to-U) exchanging are realized by the ADAR2’s adenine deaminase domain [

95] and cytidine deaminase domain [

92] alternatively.

Although click chemistry solves the problem of in vivo modification, it cannot overcome the specificity of biomolecules [

85]. Some people have begun to try to combine these two technologies to do microRNA detection [

96]. For the RNA labeling, it may be a good idea to combine the AIE with these two technologies. Unfortunately, no one has done so yet. Here, we propose an idea to use the inactive Cas13 (dCas13) or other proteins with specific RNA recognition properties, to target RNA, and use the related enzyme which is fused to the inactive Cas13 (dCas13) to perform click chemical modification on the target RNA. Looking for an enzyme is a crucial step. With the help of CRISPR/dCas13, this enzyme can specifically label RNA with AIE molecules through a click chemical reaction, thereby realizing the fluorescence tracking technology of RNA in vivo.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.M.Y.; Methodology, Z.C.Y., L.Z. and Z.M.Y.; Validation, Z.C.Y., L.Z. and Z.M.Y.; Investigation, L.Z., Y.S., X.H. and X.L.; resources, Z.C.Y., L.Z., Z.M.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.C.Y., L.Z., Z.M.Y., Y.S.; writing—review and editing, Z.C.Y., L.Z., Z.M.Y., Y.S., X.H. and X.L.; visualization, Z.C.Y., L.Z., Z.M.Y.; supervision, Z.M.Y.; project administration, Z.M.Y.; funding acquisition, Z.M.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Funded by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (LY19C020002), China Scholarship Council (201709645003), the Entrepreneurship and Innovation Project for the Overseas Returnees (or Teams) in Hangzhou (4105C5062000611).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shimomura, O.; Johnson, F.H.; Saiga, Y. Extraction, purification and properties of aequorin, a bioluminescent protein from the luminous hydromedusan, Aequorea. J. Cell. Comp. Physiol. 1962, 59, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paige, J. S.; Wu, K. Y.; Jaffrey, S. R. RNA Mimics of Green Fluorescent Protein. Science 2011, 333, 642–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, J.; Leung, N.L.; Kwok, R.T.; Lam, J.W.; Tang, B.Z. Aggregation-Induced Emission: Together We Shine, United We Soar! Chem Rev. 2015, 115, 11718-940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crick, F.H. On protein synthesis. Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 1958, 12, 138–163. [Google Scholar]

- Sprinzl, M.; Cramer, F. The -C-C-A end of tRNA and its role in protein biosynthesis. Prog. Nucleic. Acid. Res. Mol. Biol. 1979, 22, 1–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hoagland, M.B.; Stephenson, M.L.; Scott, J.F.; Hecht, L.I.; Zamecnik, P.C. A soluble ribonucleic acid intermediate in protein synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1958, 231, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahn, M.; Rogers, M.J.; Söll, D. Anticodon and acceptor stem nucleotides in tRNA(Gln) are major recognition elements for E. coli glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase. Nature 1991, 352, 258–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K. Origins and Early Evolution of the tRNA Molecule. Life (Basel). 2015, 5, 1687–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morceau, F.; Chateauvieux, S.; Gaigneaux, A.; Dicato, M.; Diederich, M. Long and short non-coding RNAs as regulators of hematopoietic differentiation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 14744–14770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.C.; Feinbaum, R.L.; Ambros, V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 1993, 75, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 9, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wightman, B.; Ha, I.; Ruvkun, G. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell 1993, 75, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, T.M. Illuminating the silence: understanding the structure and function of small RNAs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 8, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truesdell, S.S.; Mortensen, R.D.; Seo, M.; Schroeder J., C.; Lee J., H.; LeTonqueze, O.; Vasudevan, S. MicroRNA-mediated mRNA translation activation in quiescent cells and oocytes involves recruitment of a nuclear microRNP. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasudevan, S.; Steitz, J.A. AU-rich-element-mediated upregulation of translation by FXR1 and Argonaute 2. Cell 2007, 128, 1105–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kung, J.T.; Colognori, D.; Lee, J.T. Long noncoding RNAs: past, present, and future. Genetics 2013, 193, 651–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fire, A.; Xu, S.; Montgomery, M.K.; Kostas, S.A.; Driver, S.E.; Mello, C.C. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 1998, 391, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbashir, S.M.; Harborth, J.; Lendeckel, W.; Yalcin, A.; Weber, K.; Tuschl, T. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature 2001, 411, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yisraeli, J. K.; Sokol, S.; Melton, D. A. A two-step model for the localization of maternal mRNA in Xenopus oocytes: involvement of microtubules and microfilaments in the translocation and anchoring of Vg1 mRNA. Development (Cambridge, England) 1990, 108, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashirullah, A.; Cooperstock, R. L.; Lipshitz, H. D. RNA localization in development. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998, 67, 335–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose A., M. Movement of regulatory RNA between animal cells. Genesis. 2015, 53, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Chen, X. . Intercellular and systemic trafficking of RNAs in plants. Nat. Plants 2018, 4, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peabody, D.S. The RNA binding site of bacteriophage MS2 coat protein. EMBO. J. 1993, 12, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, E.; Chartrand, P.; Schaefer, M.; Shenoy, S.M.; Singer, R.H.; Long, R.M. Localization of ASH1 mRNA particles in living yeast. Mol. Cell 1998, 2, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chubb, J.R.; Trcek, T.; Shenoy, S.M.; Singer, R.H. Transcriptional pulsing of a developmental gene. Curr. Biol. 2006, 16, 1018–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golding, I.; Paulsson, J.; Zawilski, S.M.; Cox, E.C. Real-time kinetics of gene activity in individual bacteria. Cell 2005, 123, 1025–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, K.R.; Huang, N.C.; Yu, T.S. Selective Targeting of Mobile mRNAs to Plasmodesmata for Cell-to-Cell Movement. Plant Physiol. 2018, 177, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimomura, O. Structure of the chromophore of Aequorea green fluorescent protein. FEBS Lett. 1979, 104, 220–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cody, C.W.; Prasher, D.C.; Westler, W.M.; Prendergast, F.G.; Ward, W.W. Chemical structure of the hexapeptide chromophore of the Aequorea green-fluorescent protein. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 1212–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormö, M.; Cubitt, A.B.; Kallio, K.; Gross, L.A.; Tsien, R.Y.; Remington, S.J. Crystal structure of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein. Science 1996, 273, 1392–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang., F.; Moss, L.G.; Phillips, G.N. Jr. The molecular structure of green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 1996, 14, 1246–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinghorn, A.B.; Fraser, L.A.; Lang, S.; Shiu, S.C.C.; Tanner, J.A. Aptamer Bioinformatics. Int J Mol Sci. 2017, 18, 2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellington, A.D.; Szostak, J.W. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 1990, 346, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuerk, C.; Gold, L. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 1990, 249, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strack, R. L.; Disney, M. D.; Jaffrey, S. R. A superfolding Spinach2 reveals the dynamic nature of trinucleotide repeat-containing RNA. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 1219–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filonov, G. S.; Moon, J.D.; Svensen, N.; Jaffrey, S. R. Broccoli: rapid selection of an RNA mimic of green fluorescent protein by fluorescence-based selection and directed evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 16299–16308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, D.; Su, N.; Bao, B.; Xie, X.; Zuo, F.; Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Jiang, L.; Lin, Q.; et al. Visualizing RNA dynamics in live cells with bright and stable fluorescent RNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1287–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Luo, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Luo, M.; Yin, M.; Zuo, Y.; Li, G.; Yao, J.; Yang, H.; Zhang, M.; Wei, W.; Wang, M.; Wang, R.; Fan, C.; Zhao, Y. A protein-independent fluorescent RNA aptamer reporter system for plant genetic engineering. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgosheina, E. V.; Jeng, S. C.; Panchapakesan, S. S.; Cojocaru, R.; Chen, P. S.; Wilson, P. D.; Hawkins, N.; Wiggins, P. A.; Unrau, P. J. RNA mango aptamer-fluorophore: a bright, high-affinity complex for RNA labeling and tracking. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014, 9, 2412–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Filonov, G. S.; Kim, H.; Hirsch, M.; Li, X.; Moon, J. D.; Jaffrey, S. R. Imaging RNA polymerase III transcription using a photostable RNA-fluorophore complex. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 1187–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Mei, F.; Yan, H.; Jin, Z.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, X.; Tör, M.; Jackson, S.; Shi, N.; Hong, Y. Spinach-based RNA mimicking GFP in plant cells. Funct Integr Genomics 2022, 22, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Autour, A.; Jeng, S. C. Y.; Cawte, A. D.; Abdolahzadeh, A.; Galli, A.; Panchapakesan, S. S. S.; Rueda, D.; Ryckelynck, M.; Unrau, P. J. Fluorogenic RNA Mango aptamers for imaging small non-coding RNAs in mammalian cells. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, P.B.; Xu, H.; An, Z.F.; Cai, Z.Y.; Cai, Z.X.; Chao, H.; Chen, B.; Chen, M.; Chen, Y.; Chi, Z.G.; et al. Aggregation-Induced Emission. Prog. Chem. 2022, 34, 1–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Y.; Lam, J.W.; Tang, B.Z. Aggregation-induced emission. Chem Soc Rev. 2011, 40, 5361-88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; W, Y.; Lam, Jacky.; Tang, B.Z. Aggregation-Induced Emission of Tetraarylethene Luminogens. Current Organic Chemistry. 2010, 14, 2109-2132.

- Chen, J et al. Silole-containing polyacetylenes. Synthesis, thermal stability, light emission, nanodimensional aggregation, and restricted intramolecular rotation. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 1108-1117.

- Hong, Y.; Lam, JW.; Tang, BZ. Aggregation-induced emission: phenomenon, mechanism and applications. Chem Commun (Camb). 2009, 29, 4332-53.

- Xu, L.; Liang, X.; Zhang, S.; Wang, B.; Zhong, S.; Wang, M.; Cui, X. Riboflavin: A natural aggregation-induced emission luminogen (AIEgen) with excited-state proton transfer process for bioimaging. Dyes and Pigments 2020, 18, 108642.

- Yu, X.; Gao, YC.; Li, HW.; Wu, Y. Fluorescent Properties of Morin in Aqueous Solution: A Conversion from Aggregation Causing Quenching (ACQ) to Aggregation Induced Emission Enhancement (AIEE) by Polyethyleneimine Assembly. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2020, 14, e2000198.

- He, T.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Liu, S.; Li, J.; Li, S. Natural Quercetin AIEgen Composite Film with Antibacterial and Antioxidant Properties for in Situ Sensing of Al3+ Residues in Food, Detecting Food Spoilage, and Extending Food Storage Times. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2018, 1, 636-642.

- Lei, Y.; Liu, L.; Tang, X.; Yang, D.; Yang, X.; He, F. Sanguinarine and chelerythrine: two natural products for mitochondria-imaging with aggregation-induced emission enhancement and pH-sensitive characteristics. RSC 2018, 8, 3919-3927.

- Zhao, Q.; Li, L.; Li, F.; Yu, M.; Liu, Z.; Yi, T.; Huang, C. Aggregation-induced phosphorescent emission (AIPE) of iridium(III) complexes. Chem Commun (Camb). 2008, 6, 685-687.

- Dong, Y.; Lam, J.W.; Qin, A.; Sun, J.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Sun, J.; Sung, H.H.; Williams, I.D.; Kwok, H.S.; Tang, B.Z. Aggregation-induced and crystallization-enhanced emissions of 1,2-diphenyl-3,4-bis(diphenylmethylene)-1-cyclobutene. Chem Commun (Camb). 2007, 31, 3255-7.

- Yuan, W.Z.; Shen, X.Y.; Zhao, H.; Lam, J.W.; Tang, L.; Lu, P.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, Q.; Sun, J.Z.; Ma, Y.; Tang, B.Z. Crystallization-Induced Phosphorescence of Pure Organic Luminogens at Room Temperature. Journal of Physical Chemistry C. 2010, 114, 6090-6099.

- Bolton, O.; Lee, K.; Kim, H.J.; Lin, KY.; Kim, J. Activating efficient phosphorescence from purely organic materials by crystal design. Nat Chem. 2011, 3, 205-210.

- Leung, N.L.; Xie, N.; Yuan, W.; Liu Y.; Wu, Q.; Peng, Q.; Miao, Q.; Lam, J.W.; Tang, B.Z. Restriction of intramolecular motions: the general mechanism behind aggregation-induced emission. Chemistry. 2014, 20, 15349-53.

- Tu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Lam, J.W.Y.; Tang, B.Z. Mechanistic connotations of restriction of intramolecular motions (RIM). Natl Sci Rev. 2021, 8, nwaa260.

- Liu, D.; Zhao, Z.; Tang, B.Z. Natural products with aggregation-induced emission properties: from discovery to their multifunctional applications. Sci. Sin. Chim. 2022, 52, 1524–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Shin, H.; Hong, S.; Kim, Y. Physiological Roles of Monomeric Amyloid-beta and Implications for Alzheimer's Disease Therapeutics. Exp. Neurobiol. 2022, 31, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihaescu, A.S.; Valli, M.; Uribe, C.; Diez-Cirarda, M.; Masellis, M.; Graff-Guerrero, A.; Strafella, A. P. Beta amyloid deposition and cognitive decline in Parkinson's disease: a study of the PPMI cohort. Mol. Brain 2022, 15, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Jiang, X.; Ma, L.; Wei, W.; Li, Z.; Chang, S.; Wen, J.; Sun, J.; Li, H. Role of Abeta in Alzheimer's-related synaptic dysfunction. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 964075. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.S.; Lee, S.-J. Mechanism of Anti-alpha-Synuclein Immunotherapy. J. Mov. Disord. 2016, 9, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jiao, C.; Lu, W.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Y. Research progress in the development of organic small molecule fluorescent probes for detecting H2O2. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 18027–18041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; DeSilva, S.; Abbruscato, T. The Role of Glucose Transporters in Brain Disease: Diabetes and Alzheimer's Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 12629–12655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobotka, L. Is glucosis only basic energy substrate? Vnitr. Lek. 2016, 62, S100–102. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, J.; Cen, Y.; Kong, X.J.; Wu, S.; Liu, C.L.W.; Yu, R.Q.; Chu, X. MnO2-Nanosheet-Modified Upconversion Nanosystem for Sensitive Turn-On Fluorescence Detection of H2O2 and Glucose in Blood. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 10548–10555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.W.; Huang, Y.Z.; Lv, W.W.; Li, C.M.; Zeng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, X.P. A novel fluorescent probe based on ESIPT and AIE processes for the detection of hydrogen peroxide and glucose and its application in nasopharyngeal carcinoma imaging. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 1872–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorodzanskaya, E. G.; Larionova, V. B.; Zubrikhina, G. N.; Kormosh, N. G.; Davydova, T. V.; Laktionov, K. P. Role of glutathione-dependent peroxidase in regulation of lipoperoxide utilization in malignant tumors. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2001, 66, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Zhan, C. Y.; Wang, J.; Zeng, F.; Wu, S.Z. An Activatable Nano-Prodrug for Treating Tyrosine-Kinase-Inhibitor-Resistant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer and for Optoacoustic and Fluorescent Imaging. Small 2020, 16, e2003451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, F.; Liu, B. Organelle-specific bioprobes based on fluorogens with aggregation-induced emission (AIE) characteristics. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 9931–9944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, T.; Nagano, T. Fluorescent probes for sensing and imaging. Nat. Methods 2011, 8, 642–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, E. B. Mitochondria Medicine and its Research Trend. J. Biomed. Eng. Res. 2009, 30, 355–361. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Liu, L. Y.; Luo, H. Q.; Wang, H.Q.; Yang, D.P.; He, F. Flavanone-Based Fluorophores with Aggregation-Induced Emission Enhancement Characteristics for Mitochondria-Imaging and Zebrafish-Imaging. Molecules 2020, 25, 3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J. Targeting the lysosome: Mechanisms and treatments for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Cell. Biochem. 2022; 10, 1624–1633. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, X.D.; Zhang, M.S.; Zhao, Z.J.; Min, X.H.; Hakeem, A.; Huang, F.J.; Gao, P.C.; Xia, F.; Tang, B.Z. A photostable AIE fluorogen for lysosome-targetable imaging of living cells. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2016, 4, 7168–7168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, H.; Liu, H.; Chen, X.; Hu, R.; Li, M.; He, W.; Du, J.; Liu, Z.; Qin, A.; Lam, J.W.Y. ; Kwok, RTK.; Tang, B.Z. Augmenting photosynthesis through facile AIEgen-chloroplast conjugation and efficient solar energy utilization. Mater Horiz. 2021; 8, 1433–1438. [Google Scholar]

- Daming, X.; Mingyue, J.; Xiongfei, L.; Shouxin, L.; Jian, L.; Zhijun, Chen.; and Shujun, L. Sustainable Carbon Dot-Based AIEgens: Promising Light-Harvesting Materials for Enhancing Photosynthesis.ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2021, 9, 4139-4145.

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, S.; He, W.; Qiu, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Tang, B.Z. AIEgens in Solar Energy Utilization: Advances and Opportunities. Langmuir. 2022, 38, 8719-8732.

- Liu, H.; Yan, N.; Bai, H.; Kwok, R. T. K.; Tang, B. Z. Aggregation-induced emission luminogens for augmented photosynthesis. Exploration. 2022, 2, 20210053.

- Nicol, A.; Wang, K.; Wong, K.; Kwok, R.T.K.; Song, Z.; Li, N.; Tang, B.Z. Uptake, Distribution, and Bioimaging Applications of Aggregation-Induced Emission Saponin Nanoparticles in Arabidopsis thaliana. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017, 30, 28298-28304liana.

- Sun, L.; Wang, X.; Shi, J.; Yang, S.; Xu, L. Kaempferol as an AIE-active natural product probe for selective Al3+ detection in Arabidopsis thaliana. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2021, 249, 119303.

- Wu, M.; Yin, C.; Jiang, X.; Sun, Q.; Xu, X.; Ma, Y.; Liu, X.; Niu, N.; Chen, L. Biocompatible Abscisic Acid-Sensing Supramolecular Hybridization Probe for Spatiotemporal Fluorescence Imaging in Plant Tissues. Anal Chem. 2022, 94, 8999-9008.

- Himo, F.; Lovell, T.; Hilgraf, R.; Rostovtsev, V.V.; Noodleman, L.; Sharpless, K.B.; Fokin, V.V. Copper(I)-catalyzed synthesis of azoles. DFT study predicts unprecedented reactivity and intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostovtsev, V, V.; Green, L.G.; Fokin, V.V.; Sharpless, K, B. A stepwise huisgen cycloaddition process: copper(I)-catalyzed regioselective "ligation" of azides and terminal alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2002, 14, 2596–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agard, N.J.; Prescher, J.; Bertozzi, C.R. A strain-promoted [3 + 2] azide-alkyne cycloaddition for covalent modification of biomolecules in living systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 15046–15047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jao, C.Y.; Salic, A. Exploring RNA transcription and turnover in vivo by using click chemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008, 105, 15779–15784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheet, S.K.; Sen, B.; Patra, S. .;, Rabha, M.; Aguan, K.; Khatua, S. Aggregation-Induced Emission-Active Ruthenium(II) Complex of 4,7-Dichloro Phenanthroline for Selective Luminescent Detection and Ribosomal RNA Imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 14356–14366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinek, M.; Chylinski, K.; Fonfara, I.; Hauer, M.; Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 2012, 337, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; Ran, F.A.; Cox, D.; Lin, S.; Barretto, R.; Habib, N.; Hsu, P.D.; Wu, X.; Jiang, W.; Marraffini, L.A.; Zhang, F. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 2013, 339, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzalone, A.V.; Koblan, L.W.; Liu, D.R. Genome editing with CRISPR-Cas nucleases, base editors, transposases and prime editors. Nat Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 824–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapinaite, A.; Knott, G.J.; Palumbo, C.M.; Lin-Shiao, E.; Richter, M.F.; Zhao, K.T.; Beal, P.A.; Liu, D.R.; Doudna, J.A. DNA capture by a CRISPR-Cas9-guided adenine base editor. Science 2020, 369, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abudayyeh, O.O.; Gootenberg, J.S.; Franklin, B.; Koob, J.; Kellner, M.J.; Ladha, A.; Joung, J.; Kirchgatterer, P.; Cox, D.B.T.; Zhang, F. A cytosine deaminase for programmable single-base RNA editing. Science 2019, 365, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, D.B.T.; Gootenberg, J.S.; Abudayyeh, O.O.; Franklin, B.; Kellner, M.J.; Joung, J.; Zhang, F. RNA editing with CRISPR-Cas13. Science 2017, 358, 1019-1027.

- Abudayyeh, O.O.; Gootenberg, J.S.; Essletzbichler, P.; Han, S.; Joung, J.; Belanto, J.J.; Verdine, V.; Cox, D.B.T.; Kellner, M.J.; Regev, A.; Lander, E.S.; Voytas, D.F.; Ting, A.Y.; Zhang, F. RNA targeting with CRISPR-Cas13. Nature 2017, 550, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abudayyeh, O.O.; Gootenberg, J.S.; Konermann, S.; Joung, J.; Slaymaker, I.M.; Cox, D.B.; Shmakov, S.; Makarova, K.S.; Semenova, E.; Minakhin, L.; Severinov, K.; Regev, A.; Lander, E.S.; Koonin, E.V.; Zhang, F. C2c2 is a single-component programmable RNA-guided RNA-targeting CRISPR effector. Science 2016, 353, aaf5573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H.; Bu, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Li, X.; Wei, J.; He, X.; Wan, J. Click Chemistry Actuated Exponential Amplification Reaction Assisted CRISPR-Cas12a for the Electrochemical Detection of MicroRNAs. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 35515–35522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).