Submitted:

02 January 2024

Posted:

03 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Proposed Methodology

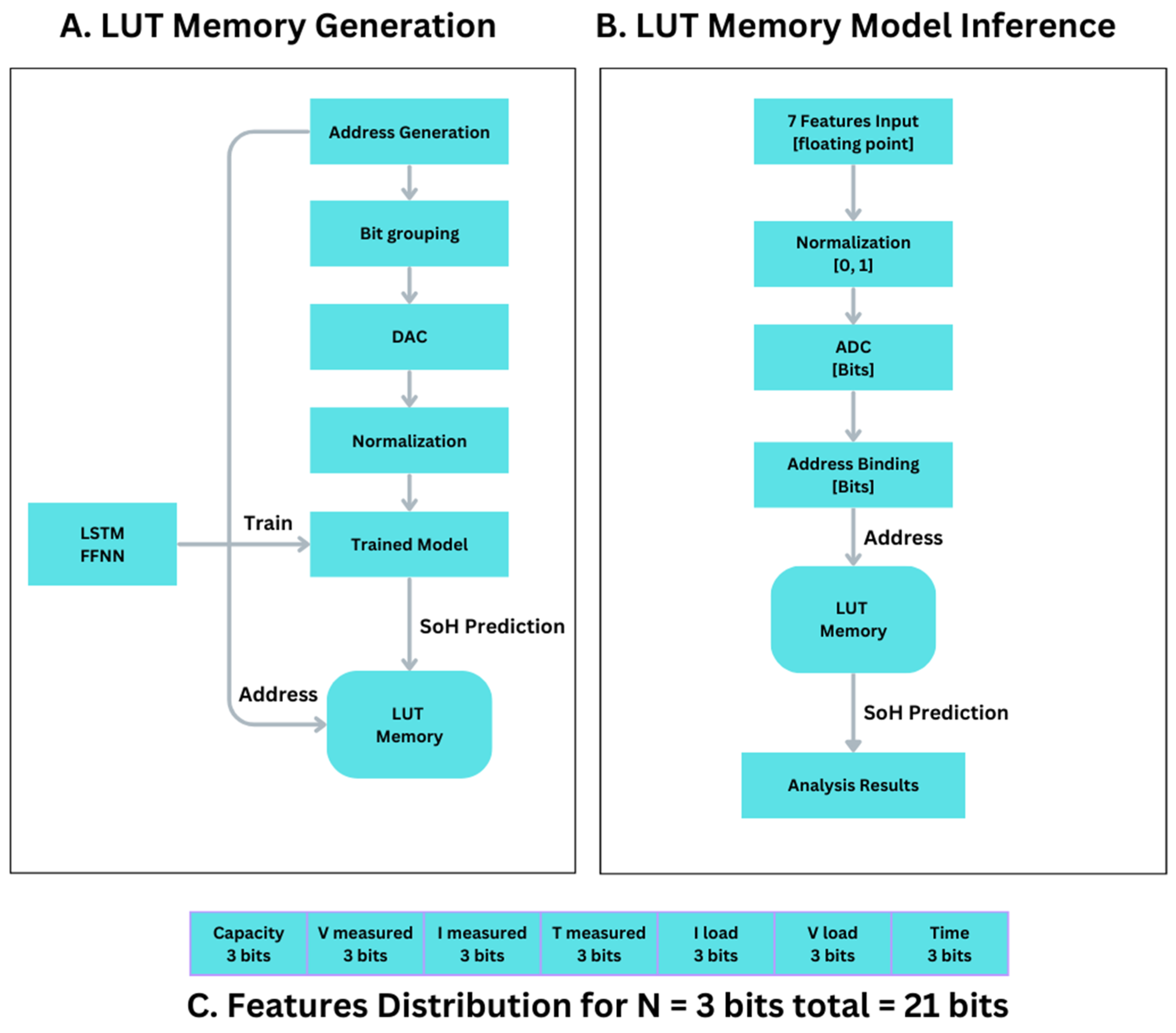

2.1. LUT-Memory Creation and Usage

2.2. LUT Generation:

- Step 1. The address bit combination starts from 0 up to 27n. The binary address generated depends highly on the number of bits assigned to each of the seven features. The ones that will be tested are 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 bits. Table 3 shows the details.

- Step 2. Then the generated address bits are grouped into seven feature groups, while each feature owns its own number of bits, generating a feature binary address bit.

- Step 3. The address bit value for each feature is normalized as bits value / 2n, where n is the number of bits selected for the feature.

- Step 4. The seven normalized feature values are presented to the trained deep neural network.

- Step 5. The value inferred from the model is stored in the LUT memory at the given address.

- Step 6. Then the next address is selected, and the whole operation is repeated (going to step 1).

2.3. LUT Usage

- Step 1. Starting from the seven feature values (capacity, ambient temperature, date-time, measured volts, measured current, measured temperature, load voltage, and load current)

- Step 2. Each of the seven feature values will be normalized (0, 1).

- Step 3. Then those will be quantized based on the next configurations: 2 bits, 3 bits, 4 bits, 5 bits, 6 bits, and 8 bits, depending on the adaptation.

- Step 4. Quantization produces the binary bits for each feature.

- Step 5. Combining all bits into one address, as shown in Figure 3,

3. Related Works on Quantization in DNN

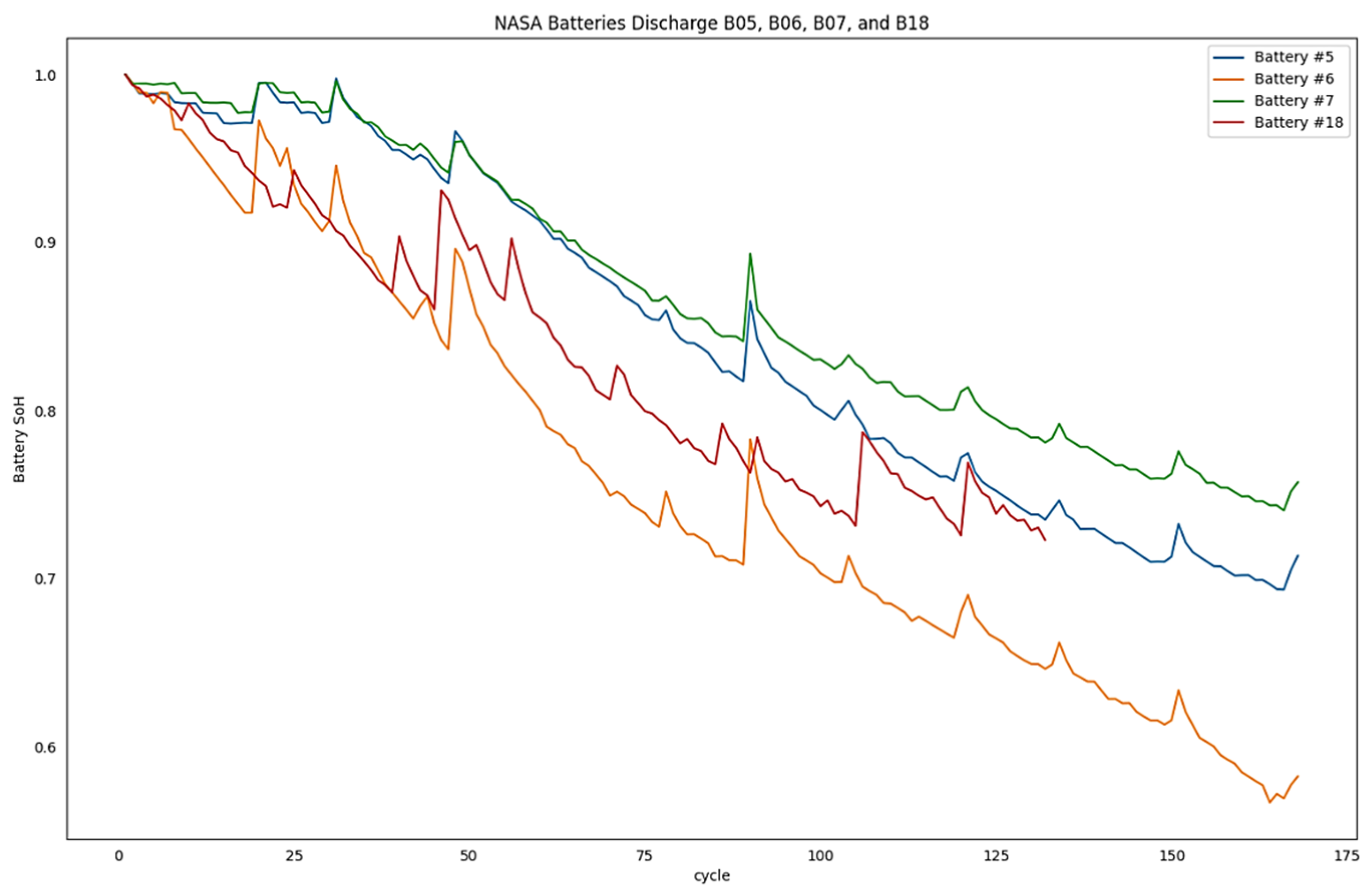

4. Dataset Description

5. Background and Preliminaries

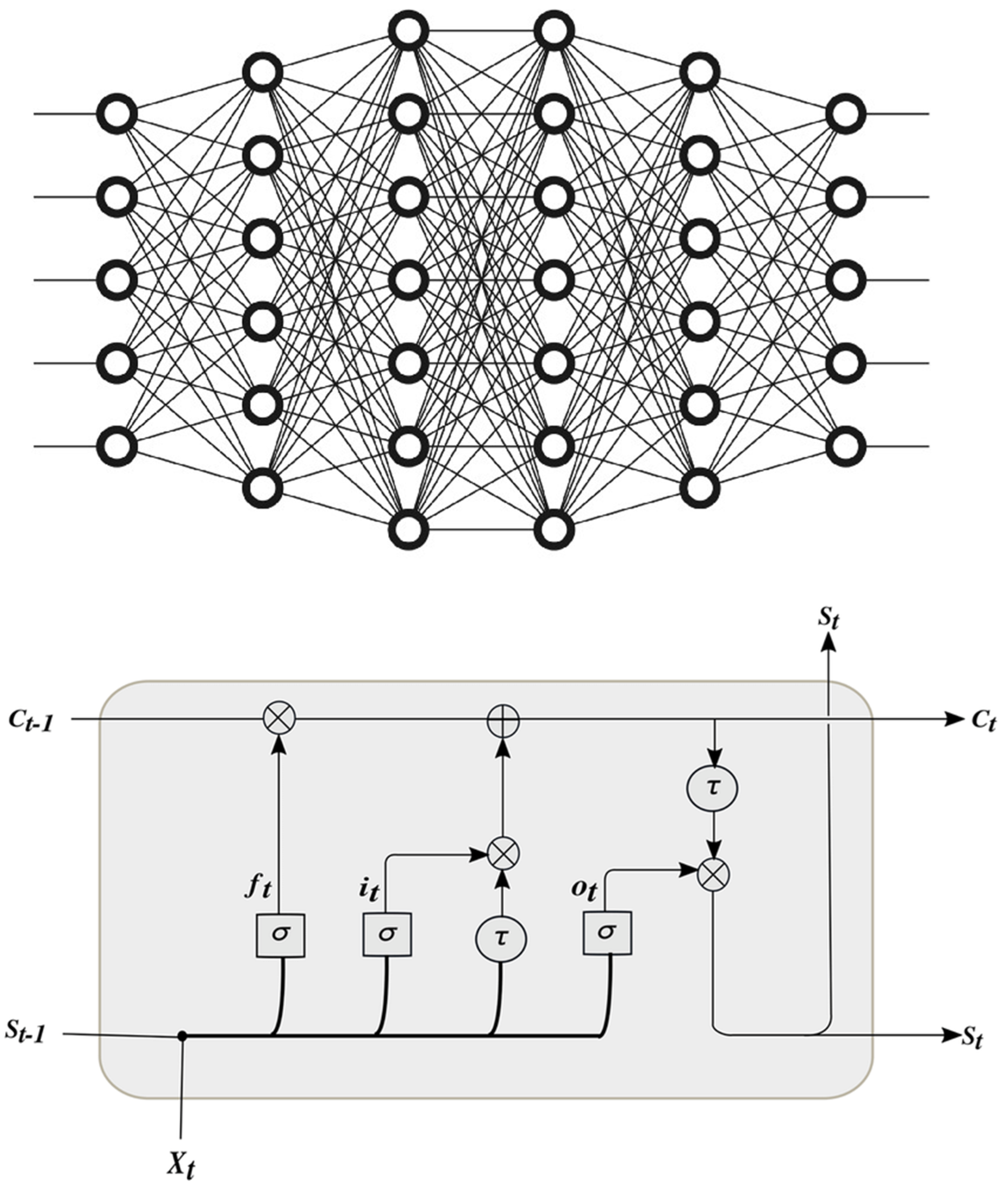

5.1. Fully Connected Deep Neural Network

5.2. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Deep Neural Network

6. Performance Evaluation and Metrics

6.1. Performance Evaluation Indicators

6.2. Models Training

7. Evaluation Results and Discussion

8. Conclusions

References

- Whittingham, M.S. Electrical Energy Storage and Intercalation Chemistry. Science 1976, 192, 1126–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stan, A.I.; Świerczyński, M.; Stroe, D.I.; Teodorescu, R.; Andreasen, S.J. Lithium ion battery chemistries from renewable energy storage to automotive and back-up power applications—An overview. In2014 International Conference on Optimization of Electrical and Electronic Equipment (OPTIM) 2014 May 22 (pp. 713-720). IEEE.

- Nishi, Y. Lithium-Ion Secondary Batteries; Past 10 Years and the Future. J. Power Sources 2001, 100, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.C.; Tseng, K.H.; Liang, J.W.; Chang, C.L.; Pecht, M.G. An online SOC and SOH estimation model for lithium-ion batteries. Energies. 2017, 10, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenough, J.B.; Kim, Y. Challenges for rechargeable Li batteries. Chemistry of materials 2010, 22, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitta, N.; Wu, F.; Lee, J.T.; Yushin, G. Li-Ion Battery Materials: Present and Future. Mater. Today 2015, 18, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Jiang, B.; Hu, X.; Lin, X.; Wei, X.; Pecht, M. Advanced battery management strategies for a sustainable energy future: Multilayer design concepts and research trends. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2021, 138, 110480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawder, M.T.; Suthar, B.; Northrop, P.W.; De, S.; Hoff, C.M.; Leitermann, O.; Crow, M.L.; Santhanagopalan, S.; Subramanian, V.R. Battery energy storage system (BESS) and battery management system (BMS) for grid-scale applications. Proceedings of the IEEE. 2014, 102, 1014–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Gao, W.; Zheng, Y.; Ouyang, M.; Li, J.; Han, X.; Zhou, L. A comparative study of global optimization methods for parameter identification of different equivalent circuit models for Li-ion batteries. Electrochimica Acta 2019, 295, 1057–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, G.; Li, X.; Chen, Z. A fractional-order model-based state estimation approach for lithium-ion battery and ultra-capacitor hybrid power source system considering load trajectory. Journal of Power Sources 2020, 449, 227543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Wang, X.; He, Y. Remaining useful life and state of health prediction for lithium batteries based on empirical mode decomposition and a long and short memory neural network. Energy 2021, 232, 121022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rechkemmer, S.K.; Zang, X.; Zhang, W.; Sawodny, O. Empirical Li-ion aging model derived from single particle model. Journal of Energy Storage 2019, 21, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z. A comparative study of battery state-of-health estimation based on empirical mode decomposition and neural network. Journal of Energy Storage 2022, 54, 105333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z.; Wang, S.; Lacey, M.J.; Brandell, D.; Thiringer, T. Bridging physics-based and equivalent circuit models for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochimica Acta 2021, 372, 137829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Q.; Yue, F.; Zhao, D. A Data-Driven Approach to State of Health Estimation and Prediction for a Lithium-Ion Battery Pack of Electric Buses Based on Real-World Data. Sensors 2022, 22, 5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, M.; Tavallaey, S. Improved Battery Cycle Life Prediction Using a Hybrid Data-Driven Model Incorporating Linear Support Vector Regression and Gaussian. ChemPhysChem 2022, 23, e202100829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wang, Z. Prognostic health condition for lithium battery using the partial incremental capacity and Gaussian process regression. J. Power Sources 2019, 421, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Abdel-Monem, M. A quick on-line state of health estimation method for Li-ion battery with incremental capacity curves processed by Gaussian filter. J. Power Sources 2018, 373, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onori, S.; Spagnol, P.; Marano, V.; Guezennec, Y.; Rizzoni, G. A New Life Estimation Method for Lithium-Ion Batteries in Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles Applications. Int. J. Power Electron. 2012, 4, 302–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plett, G.L. Extended Kalman Filtering for Battery Management Systems of LiPB-Based HEV Battery Packs: Part 3. State and Parameter Estimation. J. Power Sources 2004, 134, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, K.; Saha, B.; Saxena, A.; Celaya, J.R.; Christophersen, J.P. Prognostics in Battery Health Management. IEEE Instrum. Meas. Mag 2008, 11, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yang, F.; Zhao, Y.; Tsui, K.L. Battery Remaining Useful Life Prediction at Different Discharge Rates. Microelectron. Reliab. 2017, 78, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Landers, R.G.; Park, J. A Comprehensive Single-Particle-Degradation Model for Battery State-of-Health Prediction. J. Power Sources 2020, 456, 227950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Jiang, J.; Cao, D.; Egardt, B. Battery Health Prognosis for Electric Vehicles Using Sample Entropy and Sparse Bayesian Predictive Modeling. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 63, 2645–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, C.; Li, Z.; Lu, S.; Jin, Z.; Cho, C. Analysis of Real-Time Estimation Method Based on Hidden Markov Models for Battery System States of Health. J. Power Electron. 2016, 16, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Pang, J.; Zhou, J.; Peng, Y.; Pecht, M. Prognostics for State of Health Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on Combination Gaussian Process Functional Regression. Microelectron. Reliab. 2013, 53, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumprom, P.; Yodo, N. A Data-Driven Predictive Prognostic Model for Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on a Deep Learning Algorithm. Energies 2019, 12, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Qahouq, J.A.A. Adaptive and Fast State of Health Estimation Method for Lithium-Ion Batteries Using Online Complex Impedance and Artificial Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), Anaheim, CA, USA, 17–21 March 2019; pp. 3361–3365. [Google Scholar]

- Eddahech, A.; Briat, O.; Bertrand, N.; Delétage, J.Y.; Vinassa, J.M. Behavior and State-of-Health Monitoring of Li-Ion Batteries Using Impedance Spectroscopy and Recurrent Neural Networks. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2012, 42, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Sadoughi, M.; Chen, X.; Hong, M.; Hu, C. A Deep Learning Method for Online Capacity Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Energy Storage 2019, 25, 100817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.; Goebel, K. Battery data set, NASA ames prognostics data repository. NASA Ames, Moffett Field, CA, USA.

- Ren, L.; Zhao, L.; Hong, S.; Zhao, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L. Remaining Useful Life Prediction for Lithium-Ion Battery: A Deep Learning Approach. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 50587–50598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumprom, P.; Yodo, N. A Data-Driven Predictive Prognostic Model for Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on a Deep Learning Algorithm. Energies 2019, 12, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Ryu, S.; Park, K.; Kim, H. Machine Learning-Based Lithium-Ion Battery Capacity Estimation Exploiting Multi-Channel Charging Profiles. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 75143–75152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, R.; Liu, X.; Jiang, S.; Li, T.; Hu, P.; Lin, J.; Yu, F.; Yan, J. Differentiable soft quantization: Bridging full-precision and low-bit neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision 2019 (pp. 4852-4861). [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.; Wang, Z.; Venkataramani, S.; Chuang, P.I.; Srinivasan, V.; Gopalakrishnan, K. Pact: Parameterized clipping activation for quantized neural networks. arXiv:1805.06085. 2018 May 16.

- Esser, S.K.; McKinstry, J.L.; Bablani, D.; Appuswamy, R.; Modha, D.S. Learned step size quantization. arXiv:1902.08153. 2019 Feb 21.

- Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Han, K.; Xu, C.; Xu, C.; Tao, D.; Xu, C. Searching for low-bit weights in quantized neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems. 2020, 33, 4091–4102. [Google Scholar]

- Courbariaux, M.; Bengio, Y.; David, J.P. Binaryconnect: Training deep neural networks with binary weights during propagations. Advances in neural information processing systems 2015, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Han, S.; Mao, H.; Dally, W.J. Trained ternary quantization. arXiv 2016 Dec 4. arXiv:1612.01064. 2016 Dec 4.

- Rastegari, M.; Ordonez, V.; Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. Xnor-net: Imagenet classification using binary convolutional neural networks. InEuropean conference on computer vision 2016 Sep 17 (pp. 525-542). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Ullrich, K.; Meeds, E.; Welling, M. Soft weight-sharing for neural network compression. arXiv 2017 Feb 13. arXiv:1702.04008. 2017 Feb 13.

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, A.; Lin, W.; Xiong, H. Deep neural network compression with single and multiple level quantization. InProceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence 2018 Apr 29 (Vol. 32, No. 1).

- Zhou, A.; Yao, A.; Guo, Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, Y. Incremental network quantization: Towards lossless cnns with low-precision weights. arXiv:1702.03044. 2017 Feb 10.

- Miyashita, D.; Lee, E.H.; Murmann, B. Convolutional neural networks using logarithmic data representation. arXiv:1603.01025. 2016 Mar 3.

- Blalock, D.; Gonzalez Ortiz, J.J.; Frankle, J.; Guttag, J. What is the state of neural network pruning? Proceedings of machine learning and systems 2020, 2, 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Gou, J.; Yu, B.; Maybank, S.J.; Tao, D. Knowledge distillation: A survey. International Journal of Computer Vision. 2021, 129, 1789–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google. 2019. TensorFlow: An end-to-end open source machine learning platform. https://www.tensorflow.org/.

- MACE. 2020. https://github.com/XiaoMi/mace.

- Microsoft. 2019. ONNX Runtime. https://github.com/microsoft/.

- Wang, M.; Ding, S.; Cao, T.; Liu, Y.; Xu, F. Asymo: Scalable and efficient deep-learning inference on asymmetric mobile cpus. InProceedings of the 27th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking 2021 Sep 9 (pp. 215-228).

- Wang, M.; Ding, S.; Cao, T.; Liu, Y.; Xu, F. Asymo: Scalable and efficient deep-learning inference on asymmetric mobile cpus. InProceedings of the 27th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking 2021 Sep 9 (pp. 215-228).

- Liang, R.; Cao, T.; Wen, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Zou, J.; Liu, Y. Romou: Rapidly generate high-performance tensor kernels for mobile gpus. InProceedings of the 28th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing And Networking 2022 Oct 14 (pp. 487-500).

- Jiao, Y.; Han, L.; Long, X. Hanguang 800 npu–the ultimate ai inference solution for data centers. In2020 IEEE Hot Chips 32 Symposium (HCS) 2020 Aug 1 (pp. 1-29). IEEE Computer Society.

- Jouppi, N.P.; Yoon, D.H.; Ashcraft, M.; Gottscho, M.; Jablin, T.B.; Kurian, G.; Laudon, J.; Li, S.; Ma, P.; Ma, X.; Norrie, T. Ten lessons from three generations shaped google’s tpuv4i: Industrial product. In2021 ACM/IEEE 48th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA) 2021 Jun 14 (pp. 1-14). IEEE.

- Wechsler, O.; Behar, M.; Daga, B. Spring hill (nnp-i 1000) intel’s data center inference chip. In2019 IEEE Hot Chips 31 Symposium (HCS) 2019 Aug 1 (pp. 1-12). IEEE Computer Society.

- Xiong, R.; Li, L.; Tian, J. Towards a smarter battery management system: A critical review on battery state of health monitoring methods. Journal of Power Sources. 2018, 405, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.A.; Lipu, M.H.; Hussain, A.; Mohamed, A. A review of lithium-ion battery state of charge estimation and management system in electric vehicle applications: Challenges and recommendations. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2017, 78, 834–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waag, W.; Fleischer, C.; Sauer, D.U. Critical review of the methods for monitoring of lithium-ion batteries in electric and hybrid vehicles. Journal of Power Sources. 2014, 258, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, L.; Bach, T.; Virsik, W.; Schmitt, A.; Müller, J.; Staab, T.E.M.; Sextl, G. Probing Lithium-Ion Batteries’ State-of-Charge Using Ultrasonic Transmission—Concept and Laboratory Testing. J. Power Sources 2017, 343, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.B.; Owen, R.E.; Kok, M.D.; Maier, M.; Majasan, J.; Braglia, M.; Stocker, R.; Amietszajew, T.; Roberts, A.J.; Bhagat, R.; Billsson, D. Identifying defects in Li-ion cells using ultrasound acoustic measurements. Journal of The Electrochemical Society. 2020, 167, 120530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R-Smith, N.A.; Leitner, M.; Alic, I.; Toth, D.; Kasper, M.; Romio, M.; Surace, Y.; Jahn, M.; Kienberger, F.; Ebner, A.; Gramse, G. Assessment of lithium ion battery ageing by combined impedance spectroscopy, functional microscopy and finite element modelling. Journal of Power Sources. 2021, 512, 230459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Yu, H.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Yang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, B.; Brandon, N.P.; Yang, S. Bridging multiscale characterization technologies and digital modeling to evaluate lithium battery full lifecycle. Advanced energy materials. 2022, 12, 2200889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Ouyang, M.; Lu, L.; Li, J.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Z. A comparative study of commercial lithium ion battery cycle life in electrical vehicle: Aging mechanism identification. Journal of power sources 2014, 251, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Judd, P.; Zhang, X.; Isaev, M.; Micikevicius, P. Integer quantization for deep learning inference: Principles and empirical evaluation. arXiv:2004.09602. 2020 Apr 20.

| Bits / Feature | Values given | Bits Total (Address) |

SQNR dB |

Memory Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 | 14 | 12.04 | 16K |

| 3 | 8 | 21 | 18.06 | 2M |

| 4 | 16 | 28 | 24.08 | 256M |

| 5 | 32 | 35 | 30.10 | 32G |

| 6 | 64 | 42 | 36.12 | 4T |

| 7 | 128 | 49 | 42.14 | ---- |

| 8 | 256 | 56 | 48.16 | ---- |

| Capacity | Vm | Im | Tm | ILoad | VLoad | Time (s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | 1.28745 | 2.44567 | -2.02909 | 23.2148 | -1.9984 | 0.0 | 0 |

| Max | 1.85648 | 4.22293 | 0.00749 | 41.4502 | 1.9984 | 4.238 | 3690234 |

|

Model 1 FCNN |

Layers | Output Shape | Parameters No. |

| Dense | (node, 8) | 217 | |

| Dense | (node, 8) | ||

| Dense | (node, 8) | ||

| Dense | (node, 8) | ||

| Dense | (node, 1) | ||

| Layers | Output Shape | Parameters No. | |

|

Model 2 LSTM |

LSTM 1 | (N, 7, 200) | 1.124 M |

| Dropout 1 | (N, 7, 200) | ||

| LSTM 2 | (7, 200) | ||

| Dropout 2 | (N, 7, 200) | ||

| LSTM 3 | (N, 7, 200) | ||

| Dropout 3 | (N, 7, 200) | ||

| LSTM 4 | (N, 200) | ||

| Dropout 4 | (N, 200) | ||

| Dense | (N, 1) |

| Model | Batch size | Epochs | Time(s) | Loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCNN | 25 | 50 | 200 | 0.0243 |

| LSTM | 25 | 50 | 7453 | 3.1478E-05 |

| Battery | Model | RMSE | MAE | MAPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B0006 | FCNN | 0.080010 | 0.068220 | 0.100970 |

| LSTM | 0.076270 | 0.067620 | 0.098770 | |

| B0007 | FCNN | 0.019510 | 0.018019 | 0.021460 |

| LSTM | 0.029282 | 0.024710 | 0.030434 | |

| B0018 | FCNN | 0.015680 | 0.013610 | 0.016890 |

| LSTM | 0.018021 | 0.016371 | 0.020547 |

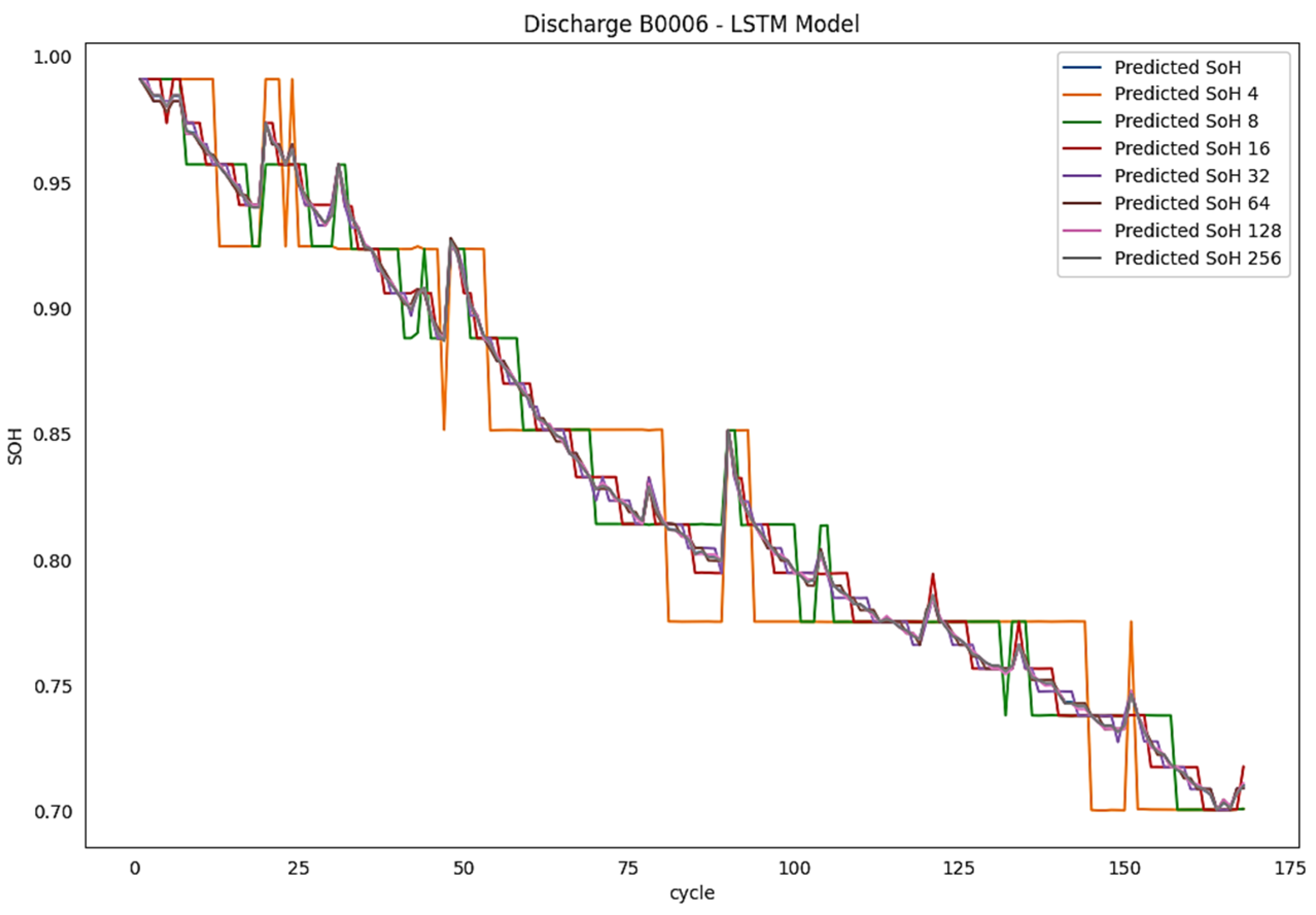

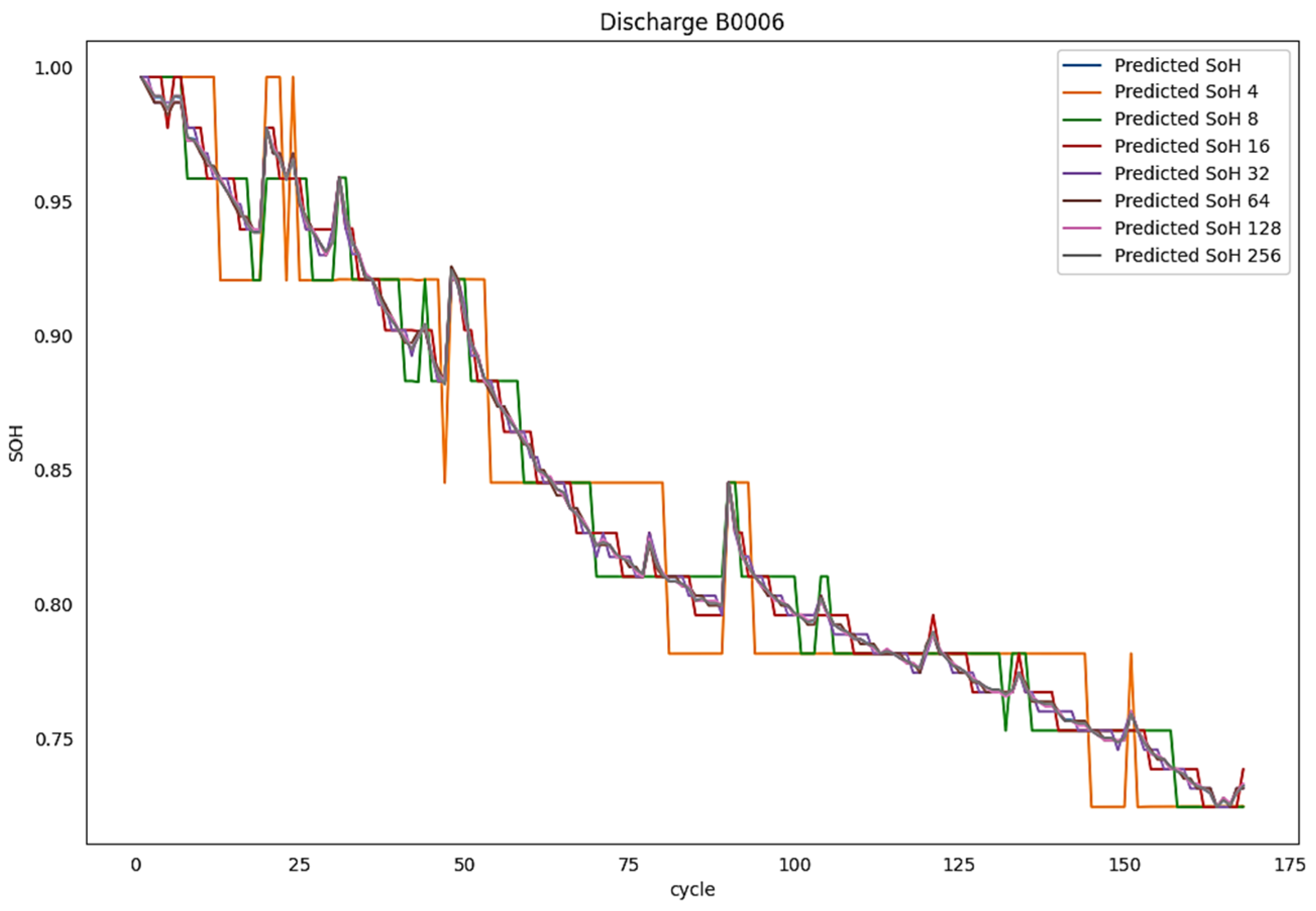

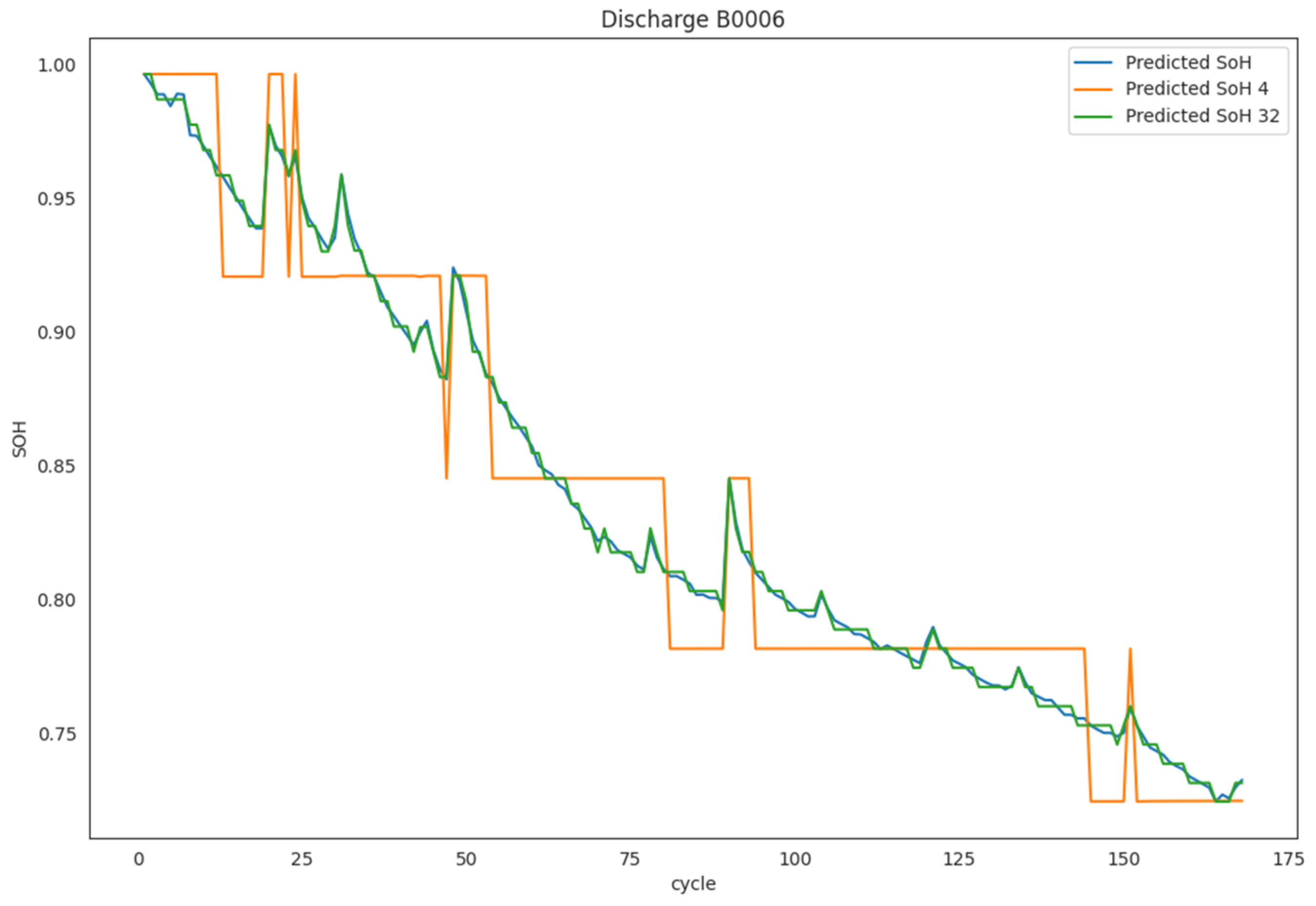

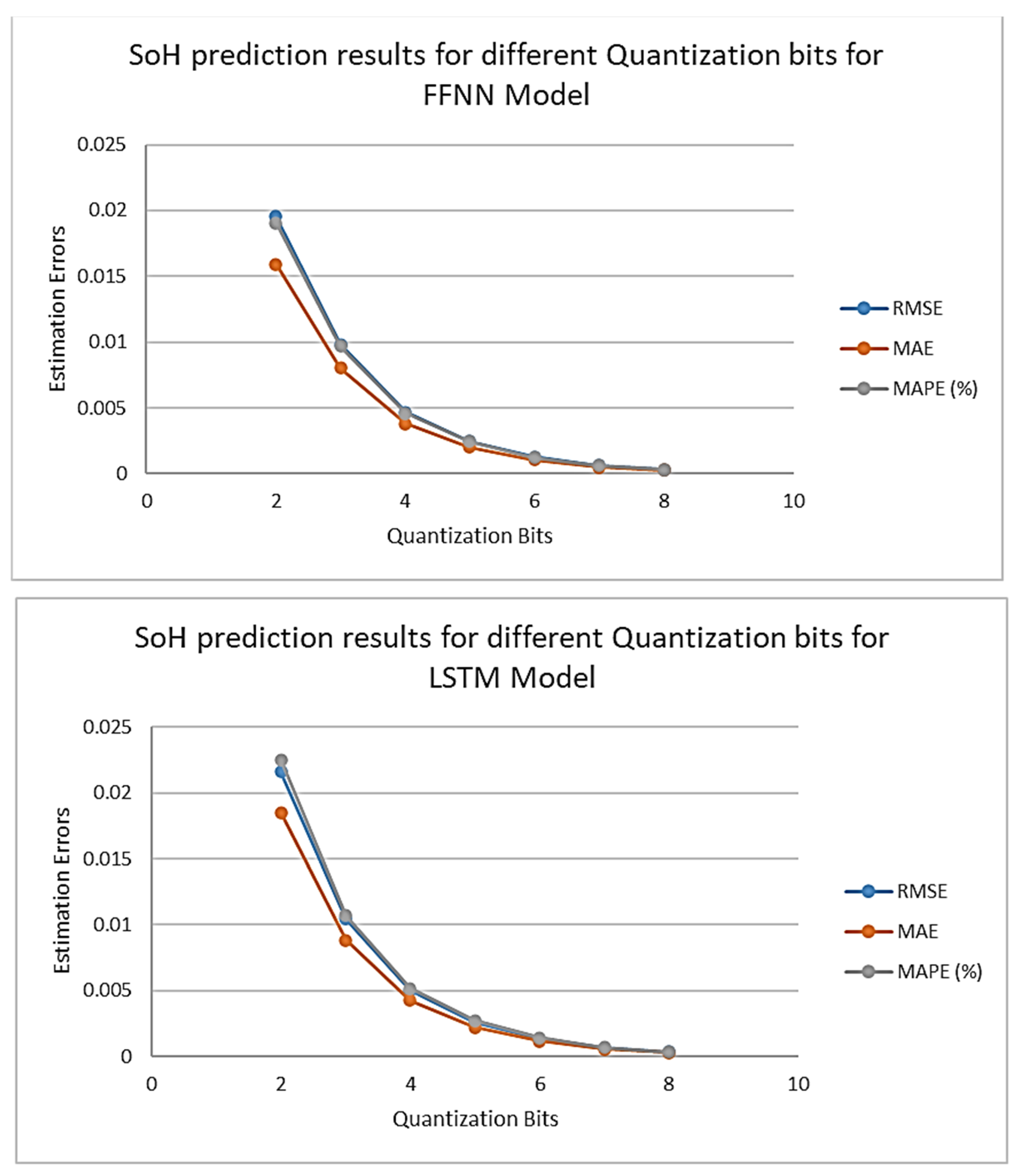

| Battery | Model | Quantization Bits | RMSE | MAE | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B0006 | FCNN | 2 | 0.0195370 | 0.0159236 | 0.0190499 |

| 3 | 0.0098006 | 0.0080317 | 0.0096645 | ||

| 4 | 0.0046815 | 0.0037988 | 0.0045664 | ||

| 5 | 0.0024301 | 0.0020093 | 0.0024294 | ||

| 6 | 0.0012535 | 0.0010379 | 0.0012461 | ||

| 7 | 0.0006150 | 0.0005068 | 0.0006144 | ||

| 8 | 0.0003125 | 0.0002565 | 0.0003088 | ||

| LSTM | 2 | 0.0216045 | 0.0185078 | 0.0225291 | |

| 3 | 0.0104658 | 0.0088477 | 0.0107360 | ||

| 4 | 0.0050010 | 0.0042487 | 0.0051737 | ||

| 5 | 0.0025885 | 0.0022293 | 0.0027206 | ||

| 6 | 0.0013394 | 0.0011620 | 0.0014114 | ||

| 7 | 0.0006609 | 0.0005692 | 0.0006974 | ||

| 8 | 0.0003309 | 0.0002835 | 0.0003446 | ||

| B0007 | FCNN | 2 | 0.0187614 | 0.0162685 | 0.0191451 |

| 3 | 0.0101181 | 0.0088282 | 0.0103004 | ||

| 4 | 0.0050026 | 0.0043651 | 0.0051114 | ||

| 5 | 0.0024498 | 0.0021127 | 0.0024730 | ||

| 6 | 0.0012030 | 0.0010481 | 0.0012269 | ||

| 7 | 0.0006394 | 0.0005566 | 0.0006533 | ||

| 8 | 0.0003060 | 0.0002578 | 0.0003013 | ||

| LSTM | 2 | 0.0209633 | 0.0181984 | 0.0219105 | |

| 3 | 0.0113147 | 0.0099692 | 0.0119157 | ||

| 4 | 0.0056382 | 0.0049296 | 0.0059140 | ||

| 5 | 0.0027386 | 0.0023843 | 0.0028542 | ||

| 6 | 0.0013495 | 0.0011826 | 0.0014153 | ||

| 7 | 0.0007212 | 0.0006320 | 0.0007581 | ||

| 8 | 0.0003432 | 0.0002912 | 0.0003475 | ||

| B00018 | FCNN | 2 | 0.0205289 | 0.0159912 | 0.0189426 |

| 3 | 0.0096451 | 0.0077552 | 0.0092191 | ||

| 4 | 0.0050730 | 0.0040254 | 0.0047780 | ||

| 5 | 0.0022966 | 0.0017585 | 0.0020886 | ||

| 6 | 0.0011492 | 0.0008754 | 0.0010336 | ||

| 7 | 0.0006432 | 0.0005005 | 0.0005950 | ||

| 8 | 0.0002954 | 0.0002268 | 0.0002719 | ||

| LSTM | 2 | 0.0218554 | 0.0189299 | 0.0233109 | |

| 3 | 0.0109069 | 0.0094792 | 0.0116619 | ||

| 4 | 0.0057440 | 0.0049472 | 0.0060704 | ||

| 5 | 0.0026591 | 0.0022228 | 0.0027317 | ||

| 6 | 0.0013255 | 0.0011411 | 0.0014012 | ||

| 7 | 0.0007168 | 0.0006208 | 0.0007612 | ||

| 8 | 0.0003431 | 0.0002941 | 0.0003649 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).