1. Introduction

The increase in online orders due to COVID-19 pandemic has raised consumer expectations for fast deliveries, which has led to more vehicles in urban areas, deteriorating city-life. Pre-pandemic data shows that local goods transport modes (trucks) make up to 25% of city traffic, using 40% of road space, and generating 40% of transportation-related emissions [1-3]. Projections from [

4] suggest a potential 30% increase in last-mile urban deliveries in the top 100 global cities by 2030, potentially resulting in 25 million tons of CO2 emissions annually by the same year. In response, the concept of City or Urban Logistics was developed to mitigate environmental impact and enhance urban goods flow [5-7].

Urban Logistics faces challenges, such as inventory management, e-commerce, food safety, and waste handling. These challenges can be addressed through technology integration, like the Internet of Things (IoT) [8-12], blockchain implementation [

13], cloud applications [

14], and data science utilization [

15], among others.

In this context, this paper introduces an innovative digital business concept: Urban Logistics as a Service (ULaaS), an extension of the Mobility as a Service (MaaS) concept for urban logistics [16-19]. MaaS integrates various mobility services, public and private, into a single application for on-demand multimodal mobility. While MaaS has benefits like reduced congestion and emissions, it also raises concerns about privacy, data ownership, and governance. Remote route control by mobility platforms is a valuable resource, but legal gaps and conflicting interests remain.

The foundational MaaS principles inform the ULaaS system architecture through a marketplace—a global mobility services hub for cargo transport, accessible to companies, public administrations, and end-users. Using an affinity diagram, business model components are categorized into strategic choices, value creation, value capture, and the value network based on [

20]. This study proposes a value proposition for ULaaS: integrating diverse logistics services and assets into an on-demand platform. ULaaS consolidates Urban Logistics services in a marketplace while functioning as a control tower for stakeholders, optimizing logistics movements, and curbing congestion and emissions.

ULaaS serves as an innovation and digital technology marketplace, using cellphone and GPS tracking for improved visibility and better order planning. It offers additional benefits like: • efficiently addressing congestion and pollution with decision-support tools for urban areas. • streamlining loading and unloading with consolidation centers and parcel lockers; • supporting shared economy principles, for drivers and users; • implementing reservation systems for improved urban logistics; • enabling shared vehicles and warehouse space for cost savings and • enhancing security via public entity management.

This work's contribution lies in its conceptual proposal for a digital platform, literature review, data collection and analysis methodology, business model discussion, and a preliminary concept for a Minimum Viable Product (MVP). Additionally, the paper explores modules like "Parking Space Reservation," "Warehousing Spaces," "E-commerce," and "Logistics Services." It serves as an informational resource for stakeholders within the urban logistics ecosystem, including potential private operators and legislators aiming to enhance governance.

2. Literature Review

The emergence of service-oriented architectures and proliferation of the cloud computing has given rise to various models, including Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS), Platform as a Service (PaaS), and Software as a Service (SaaS). These models provide a solid foundation for developing decentralized, interoperable IT services for logistics [

21]. This evolution aligns with platforms based on the concept of Logistics as a Service (LaaS), aimed at supporting tasks across supply chain design, planning, and operations. Diverse architectural approaches for this concept have been presented by various authors [

22].

In urban transportation, digital platforms have mainly focused on passenger mobility via modes like cars, metro, trains, trams, bicycles, and public transport. Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) the digital platforms for passenger mobility is a prime example, acting as an integrated system for smart distribution and management of user-centric mobility. MaaS consolidates offerings from diverse mobility service providers through a digital interface, enabling users seamlessly plan and pay for mobility options [

23]. Successful examples include apps like Whim by MaaS Global in Helsinki, UbiGo in Gothenburg, Qixxit by Deutsche Bahn in Germany, Moovel by Daimler in Germany, and Beeline by Singapore’s Infocomm Development Authority, among others (SMILE app, Bridj, Communato/Bixi).

In a related context, Collaborative as a Service (CaaS) emerges as a concept that incolves operators more comprehensively. CaaS leverages commercial interests to provide integrated commecially public transport solutions that appeal to consumers [

24].

While Europe and United States have seen pilot projects in Europe and the United States integrating certain ULaaS concepts, these efforts are not fully comprehensive. Examples include Urban Logistics as an on-Demand Service (ULaaDS) [

25], the Alliance for Logistics Innovation through Collaboration in Europe (ALICE) [

26], Last Mile Delivery and Logistics Orchestration Platform for the Enterprise - UrbanTZ [

27], Airmee [

28], PTV Software [

29], and Lead Project [

30]. The aim pertaining to the ULaaS model involves conducting scientific research into literature best practices, as detailed in

Table 1. A more in-depth literature review is available in article 41.

Furthermore, another crucial foundation for shaping ULaaS is the conceptual business model. This model goes beyond defining the creation of the Minimum Viable Product (MVP); it also outlines the market offering, user engagement strategy, and transactional dynamics within the marketplace.

Scholars like [

31], approach the business model from three distinct perspectives: a) as inherent attributes of real companies, b) as cognitive frameworks, and c) as formal, conceptual frameworks. The last perspective involves simplifying and focusing on essential components for better manageability, understanding, prediction, measurement, and communication. As articulated by [

32], this process translates strategic issues into a tangible conceptual model, elucidating strategic positioning and goals transparently.

On the other hand, [

33] defines the business model through three key elements: the value network and the product or service's offering, which create value; value capture, which involves how the product is presented to customers; and situating the endeavor within a broader socio-economic framework.

However, [

34] takes a simpler approach, defining the business model as a systematic framework guiding the business within its social, economic, and environmental context. This integration of components ensures organizational success and clarifies objectives, current and future goals, and strategic approaches.

From a sustainability perspective, the business model's logic underscores an organization's value creation, impact, and potentials. It can also be seen as the strategic and cooperative core of an organization. The Sustainable Business Model (BMfS), as presented by [

35], thrives on a reinforcing cycle that generates value for customers, the company, and the environment. By fostering value for multiple stakeholders and the natural environment, the BMfS acts as a strategic and cooperative foundation.

Incorporating sustainability, a business model, as suggested by [

36], serves to describe, analyze, manage, and communicate based on the sustainable value proposition for all stakeholders. It encapsulates how this value is created and delivered, while also highlighting how the economy captures value while preserving or regenerating natural, social, and economic capital beyond organizational boundaries.

2. Methodological Approach

The research methodology entailed a comprehensive literature review focusing on the conceptual business model perspective of ULaaS and other innovative transport concepts, such as Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS). This review was then enhanced with qualitative data gathered from stakeholders in Campinas through structured surveys and interviews.

The initial steps comprised problem identification, followed by an extensive literature review covering the concepts of logistics, shared mobility, emerging technologies, the business perspective of ULaaS, and innovative transport paradigms. This literature review was complemented by insights from surveys, interviews, and the conceptual paper [

41].

In addition to this review, qualitative data were collected through surveys and interviews with stakeholders in Campinas, Brazil, building upon the foundation of work 22. Campinas, situated in the central-eastern portion of the São Paulo State, holds strategic significance due to its location as a logistical hub and its proximity to key transport nodes, including the Port of Santos (172 km) and Campinas International Airport, the second-largest international airport in Brazil.

The interview process was carefully planned within a clear framework and social context. A clear distinction was made between the interviewer, responsible for conducting the interview, and the interviewee, the source of information. The interviewers were trained professionals following specific instructions. It is worth mentioning Notably, the information collection instrument included both open-ended and closed-ended questions.

Data collection was conducted using a questionnaire-style survey facilitated by the "Google Forms" software. The target groups were divided into two stakeholder categories: the shipper sector and the transport sector. This division guided the design of the interview blocks, each tailored to gather specific information within the respective sector.

For the shipper sector, there were four blocks, each with distinct objectives: company processes (block 1), infrastructure status (block 2), opinions on regulations and public initiatives (block 3), and perspectives on innovation and technology (block 4). Similarly, the transport sector was explored through six data blocks: company processes (block 1), regulatory opinions (block 2), asset and information sharing (block 3), infrastructure status (block 4), governance preferences (block 5), and innovation and technology perspectives (block 6).

In total, 179 stakeholders took part in the interviews with 128 participating in person and 51 remotely. These stakeholders represented the transport, wholesaler, and retailer sectors. Insights from these interactions highlighted key priorities, including loading/unloading protocols, carrier coordination, operation challenges related to drop-offs, shared truck or warehouse usage, public sector involvement, freemium business models, and avenues for additional services on the platform [

41].

Additionally, were identified barriers to ULaaS implementation in the study area, covering aspects of infrastructure, regulation, society, politics, and technology.

To conclude, our data analysis enabled us to (i) outline main ULaaS stakeholders and their roles using a business ecosystem approach, (ii) map distinctive attributes and challenges across different domains through an innovation systems approach, and (iii) develop a prototype/MVP business model for ULaaS, as detailed in [22, 41]. The subsequent step involved defining the ULaaS business ecosystem and potential user-functionality combinations. Ultimately, we presented the proposed ULaaS business model using the Conceptual Canvas Methodology.

3. Model Proposal

The Urban Logistics as a Service (ULaaS) platform concept proposes a groundbreaking shift in logistics services. This innovative approach combines urban logistics with digital technology, paving the path for a more sustainable and efficient business model.

The ULaaS platform aims to streamline complex urban logistics processes by integrating them into a unified digital ecosystem. In doing so, it tackles the issues posed by traditional logistics systems, including congestion, pollution, and inefficient resource usage. The platform envisions a future where logistics services are optimized for both economic viability and environmental and social well-being.

The ULaaS platform uses advanced technologies like real-time data analytics, machine learning, and predictive modeling, for a flexible and adaptive solution. It enables precise demand prediction, efficient route planning, and effective resource allocation. This streamlines urban logistics operations, cutting down on unnecessary resource usage and lowering the overall carbon footprint.

Furthermore, the ULaaS platform fosters collaboration among stakeholders, including retailers, transportation providers, and local authorities. Open communication and shared data lead to a synchronized urban logistics network, minimizing redundancy, optimizing resources, and creating more sustainable cities.

From a business perspective, the ULaaS model generates new revenue streams. Through subscription-based services, pay-per-use options, or data monetization, the platform establishes a self-sustaining ecosystem that benefits all participants. Also, smart tech integration allows real-time monitoring and customer engagement, enhancing the user experience and customer satisfaction and retention.

The Urban Logistics as a Service (ULaaS) platform marks a significant step towards sustainable urban logistics. Merging logistics with digital innovation, it offers an efficient, eco-friendly, and economically viable model. By prioritizing collaboration, advanced technology utilization, and diversified revenue strategies, the ULaaS platform sets the stage for a greener and more connected future in logistics.

3.1. The Business Ecosystem of ULaaS

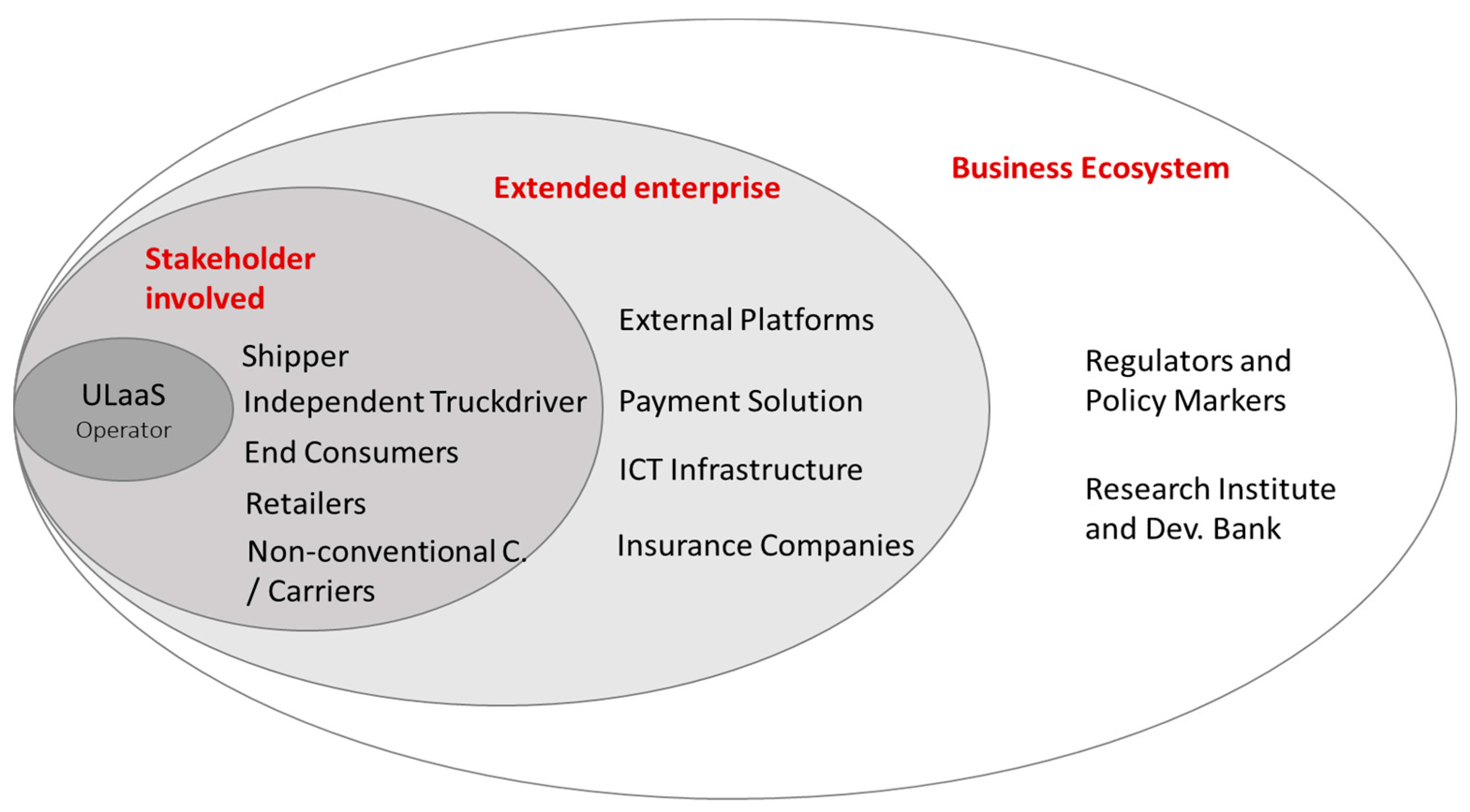

The business ecosystem of ULaaS (

Figure 1) encompasses a variety of key actors, each playing a distinct role within the framework. These actors include Shippers, End Consumers, Retailers, External Platforms, Independent Truckers, Carriers, Local Government Research Centers, Bank Developers, and various other contributors.

The ULaaS business ecosystem encompasses three essentials’ dimensions: the involved Stakeholders, the extended Enterprise, and the Business Ecosystem. Stakeholder engagement creates a dynamic context for interactions within the ULaaS framework. This facet was meticulously designed to align with the strategic vision of the team. At the core of this concept lies the comprehensive and systematic study of its mechanics to identify which tasks or actions deliver tangible value.

The extended enterprise within ULaaS involves two main groups: solution providers contributing to the ecosystem and users who rely on these solutions. This connection also extends to external platforms, enabling seamless communication between ULaaS and external systems. This communication involves various actions, including adding, editing, deleting, activating, and deactivating internet services. The Information and Communication Technology - ICT infrastructure plays a vital role in authorizing information compilation, processing, storage, and transmission. Meanwhile, payment solutions integrate an electronic payment system to ensure a smooth transactional process.

Business ecosystem is the intricate network of dynamic entities collaborating to generate and exchange sustainable value. Bank developers play a pivotal role by financing infrastructure projects, spearheading market development, and furnishing liquidity to mitigate risks that other market players might shy away from. Ultimately, the ULaaS Operator assumes the overarching responsibility of managing the entire platform, which can either be public or private. This operator serves as the nexus connecting the aforementioned dimensions.

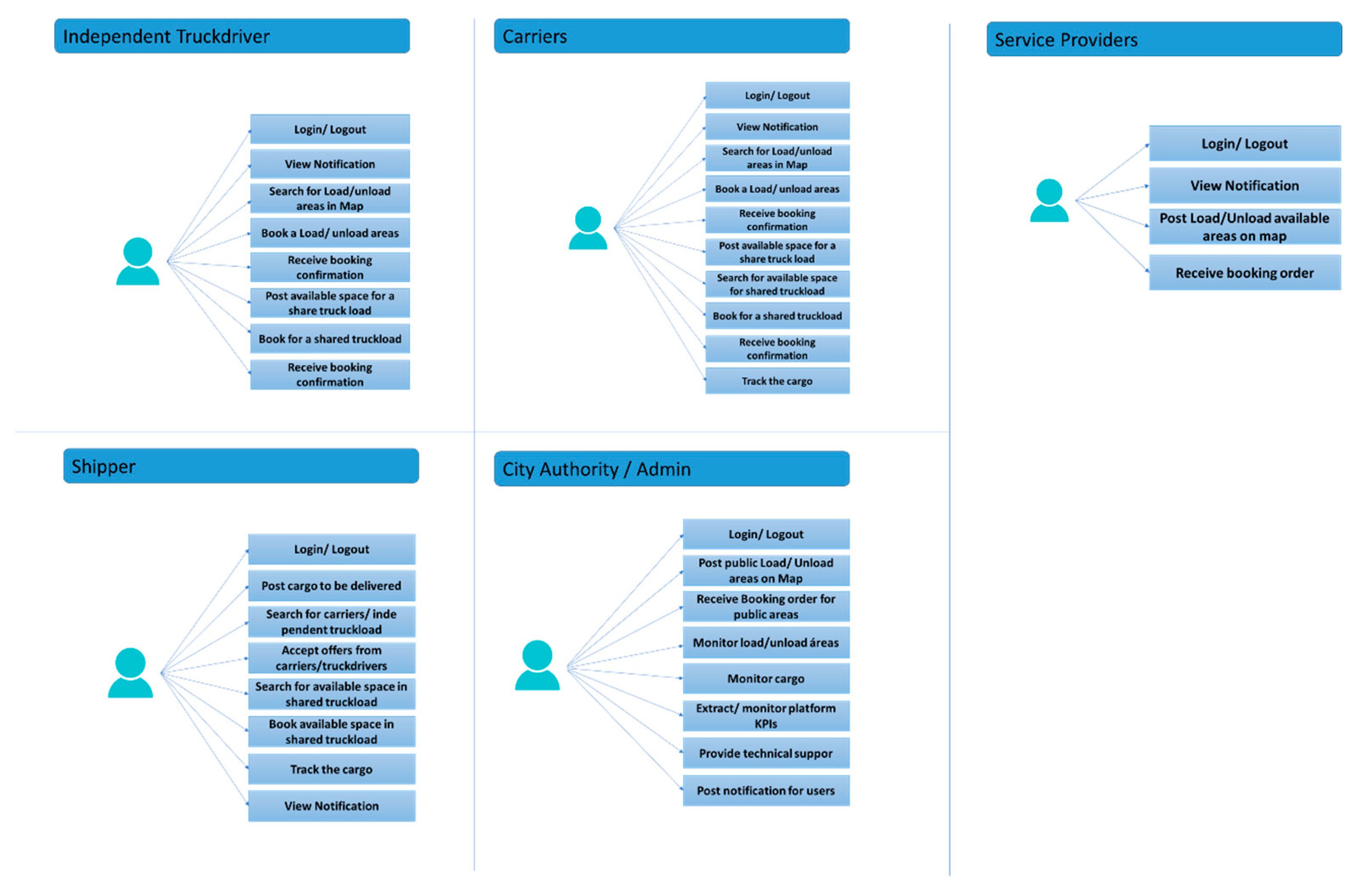

To further illustrate the dynamics, the subsequent use cases delineate potential user-functionality combinations rooted in a meticulous analysis of the core business (

Figure 2).

To ensure the optimal development of ULaaS, the involvement of diverse stakeholders is essential. This ecosystem typically involves users, transport operators, regulatory authorities, data integrators and analysts, technology, and platform providers, and the ULaaS broker/aggregator. Additionally, non-freight service providers can be incorporated into the ecosystem.

The ULaaS platform serves a diverse range of users, each with distinct roles:

Truck Drivers: This category includes independent drivers, drivers employed by transportation companies (fleet employees), or shippers (own fleet). They have the flexibility to utilize the platform's full array of functionalities or select specific ones.

Carriers: Small carriers who use urban vehicles or their own cars for cargo pick-up and delivery within urban areas or suburbs. These carriers own their vehicles and often collaborate with transportation network companies.

Non-Conventional Carriers: Independent carriers who use motorcycles, bicycles, or other non-motorized modes of transportation.

Shippers: Manufacturers who transport final products to retailers, distributors who ship products to retailers or end customers, and retailers who deliver products to end users.

Service Providers: Small businesses situated in urban locales who receive cargo from distributors, other retailers, or manufacturers.

The concept of ULaaS encompasses multiple dimensions, allowing customization based on specific city or area needs. These dimensions include:

Primary Objectives of the Urban Logistics System: Prioritizing goals like congestion reduction and improved safety.

Stakeholders’ Engagement: Identifying the relevant stakeholders.

Processes Management: Defining the processes that require management.

Technology Implementation: Determining the suitable technology for adoption.

3.2. The Business Model of ULaaS

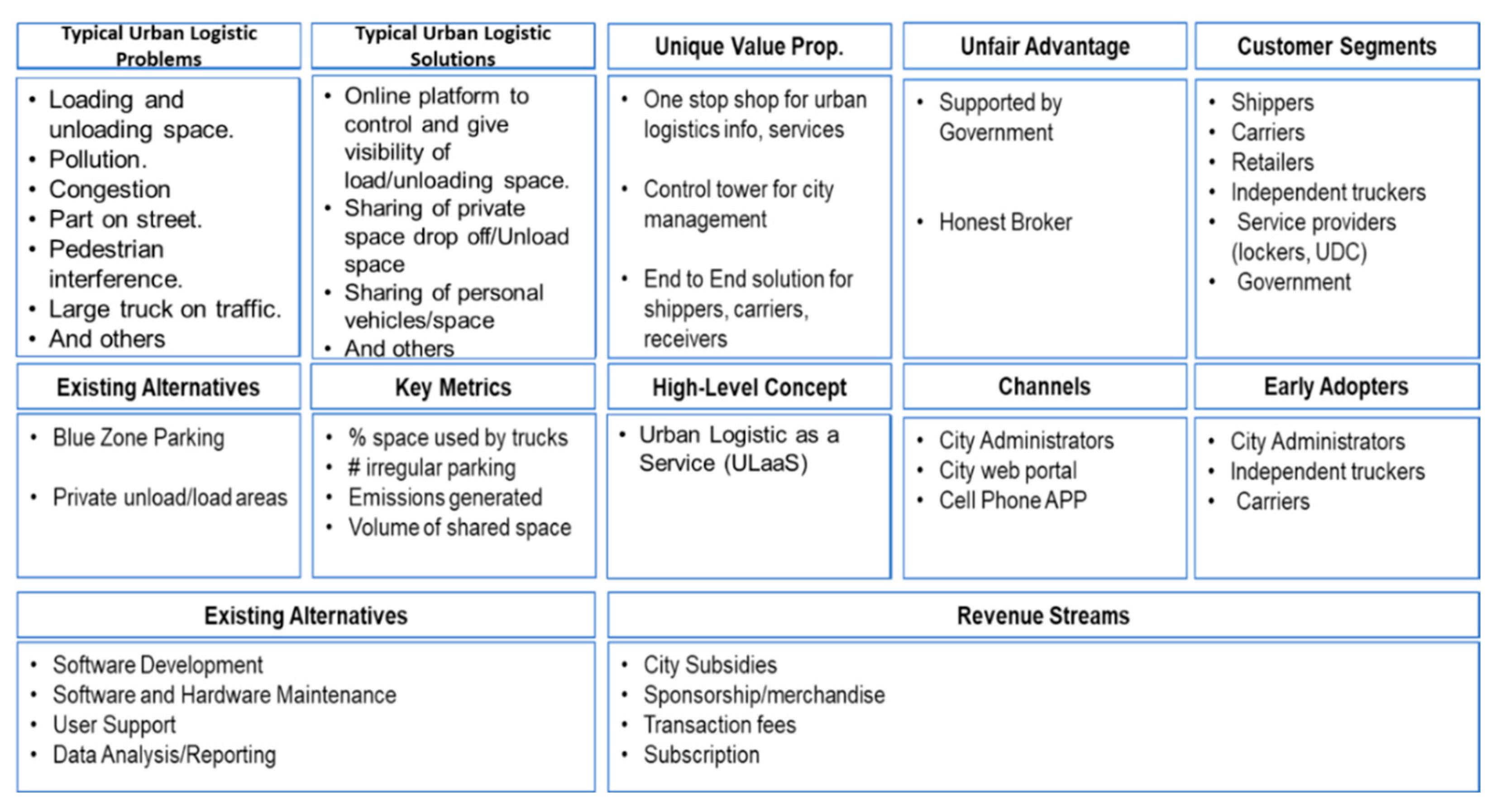

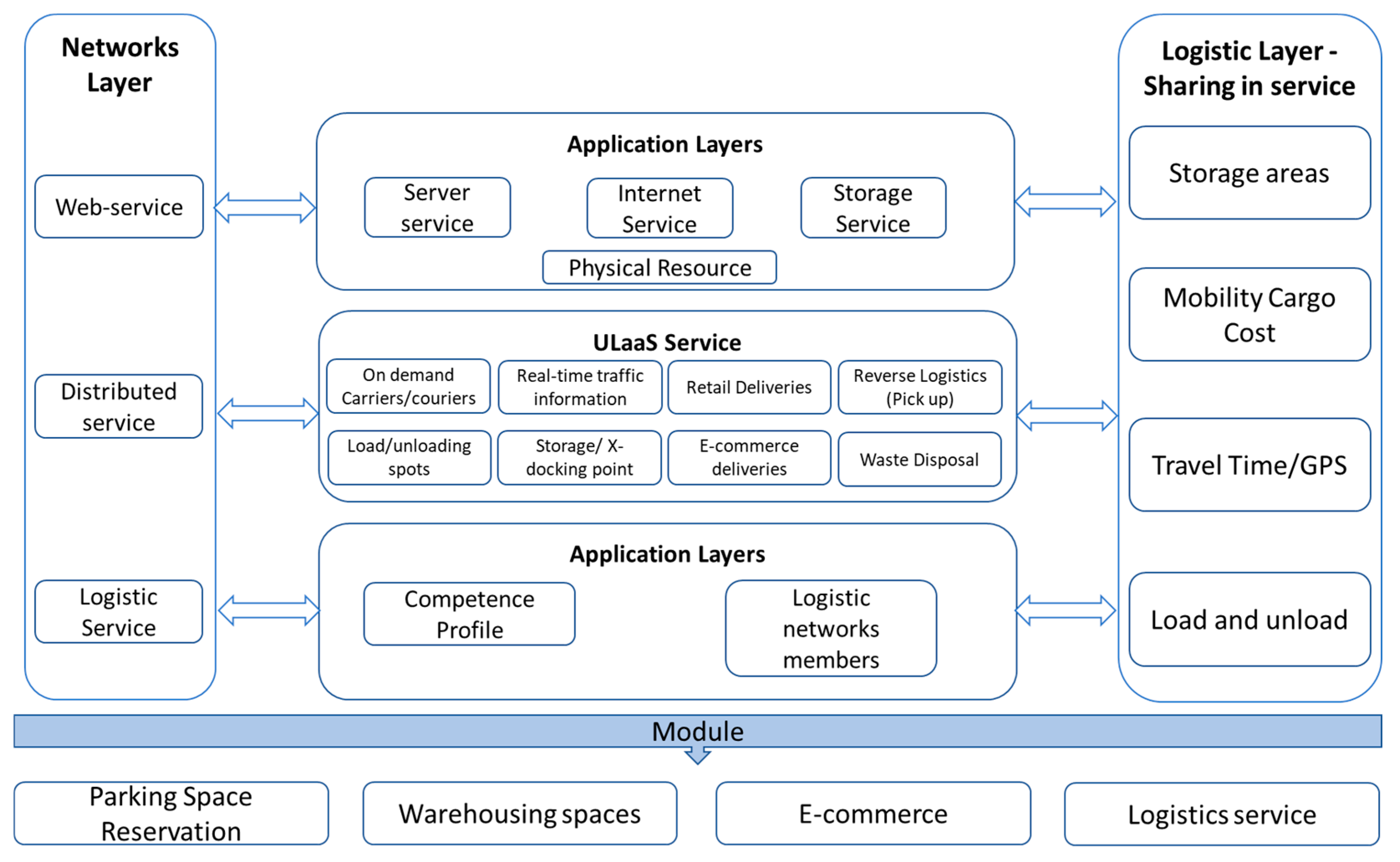

The ULaaS business model is influenced by the sharing economy paradigm. In this context, a platform acts as a bridge between supply and demand, enabling’ the sharing of assets and services within a networked structure. To craft this model, the Value Map [

37] and the Canvas Methodology [

38] were utilized. By aligning critical success factors and conceptualizing a proposition that fulfills these criteria (

Figure 3), the business model is formulated.

The validation of this business model relies on deploying a Minimum Viable Product (MVP). This MVP operates based on a set of guiding principles, that consider into a range of services that deliver value to stakeholders.

The Business Model was developed by experts in transport and logistics. This qualitative approach incorporates personal judgment, drawing insights from the details shared in article 43.

The ULaaS Business Model encompasses various dimensions and is adaptable to specific city or regional needs. These dimensions include:

- 1.

Identifying challenges from interviewees input.

- 5.

Proposing solutions like online platforms for user visibility.

- 6.

Creating a unique value proposition.

- 7.

Building competitive advantages.

- 8.

Engaging relevant stakeholders.

- 9.

Analyzing existing transport alternatives.

- 10.

Defining key process metrics.

- 11.

Exploring concepts linked with ULaaS.

- 12.

Identifying dissemination channels.

- 13.

Handling administrative processes

- 14.

Applying suitable technology.

- 15.

Outlining revenue streams.

These aspects are strategically aligned with policies, regulations, and the broader system framework, particularly within last-mile logistics. The ULaaS model primarily tackles last-mile challenges, involving tasks like integrating urban logistics players (shippers, carriers, retailers), real-time delivery coordination, Data science and AI driven decision-making, and fostering public-private partnerships to shape policies and regulations.

The ULaaS platform introduces non-motorized transport into the on-demand services spectrum, making use of public infrastructure and leveraging the collaborative economy. This move significantly curbs the city's carbon emissions associated to logistics.

Vital success factors for the ULaaS model include defining extent of public and private sector participation, formulated an effective pricing strategy and ensuring fair allocation among service providers.

Regarding public-private participation, potential models are detailed in

Table 2

The model confronts two primary challenges: monetization and determining the extent of public-private involvement.

In the fully public model, public participation encompasses all aspects except shareable resources, which remain private. This approach offers complete control over planning, implementation, and operations, enhancing credibility with the public. However, it requires maintaining competitiveness and financial independence from public funding. Conversely, the fully private model assigns all operations to the private sector, with the public sector handling ULaaS parameter planning. The third option, a blended model, involves public planning and implementation, while the private sector manages all the platform layers.

Choosing the optimal solution depends on the unique ULaaS context. It is crucial to evaluate process governance, alignment between public and private stakeholders [

40], risk assessment (covering technical, market, and institutional risks), and clarifying responsibilities. These aspects also involve business risks.

Regarding investment sources for ULaaS implementation, several factors deserve consideration, including capital infusion, financing options, and reinvestment of returns. Governments can introduce mechanisms like non-refundable investments, subsidized financing, and tax exemptions to support the project's financial break-even point, particularly during early stages and startup phase.

An essential aspect of achieving business success is establishing a pricing model and monetization strategy for services offered through the ULaaS platform. Viable options encompass sharing-based models [

42]:

Membership-based Self-Service: These targets recurring customers who frequently access products or services. It enables customers to benefit without owning the underlying assets held by the subscription-based company. (e.g., Air Freight Shippers, Ocean Freight Shippers, Rail Freight Shippers, Ground Freight Shippers)

Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Service: Involves a decentralized network of individuals utilizing common communication protocol with aligned computer equipment. (e.g., Service providers)

Non-Membership Self-Service: This category encompasses enterprises such as truck or van rentals and pooling, which operate independently of membership requirements. (e.g., Freight hauler, dry van hauler, flatbed driver, local truck driver, refrigerated driver, Over-the-road truck driver)

For-Hire Service Models: This category involves the integration of vehicles and assets with pricing mechanisms that dynamically adjust based on meter readings or similar technology. (e.g., shared storage area)

These models provide strategies for structuring pricing effectively and leveraging the potential of the ULaaS platform.

4. Model Field Validation

4.1. Survey Design

The data collection process details are outlined in [

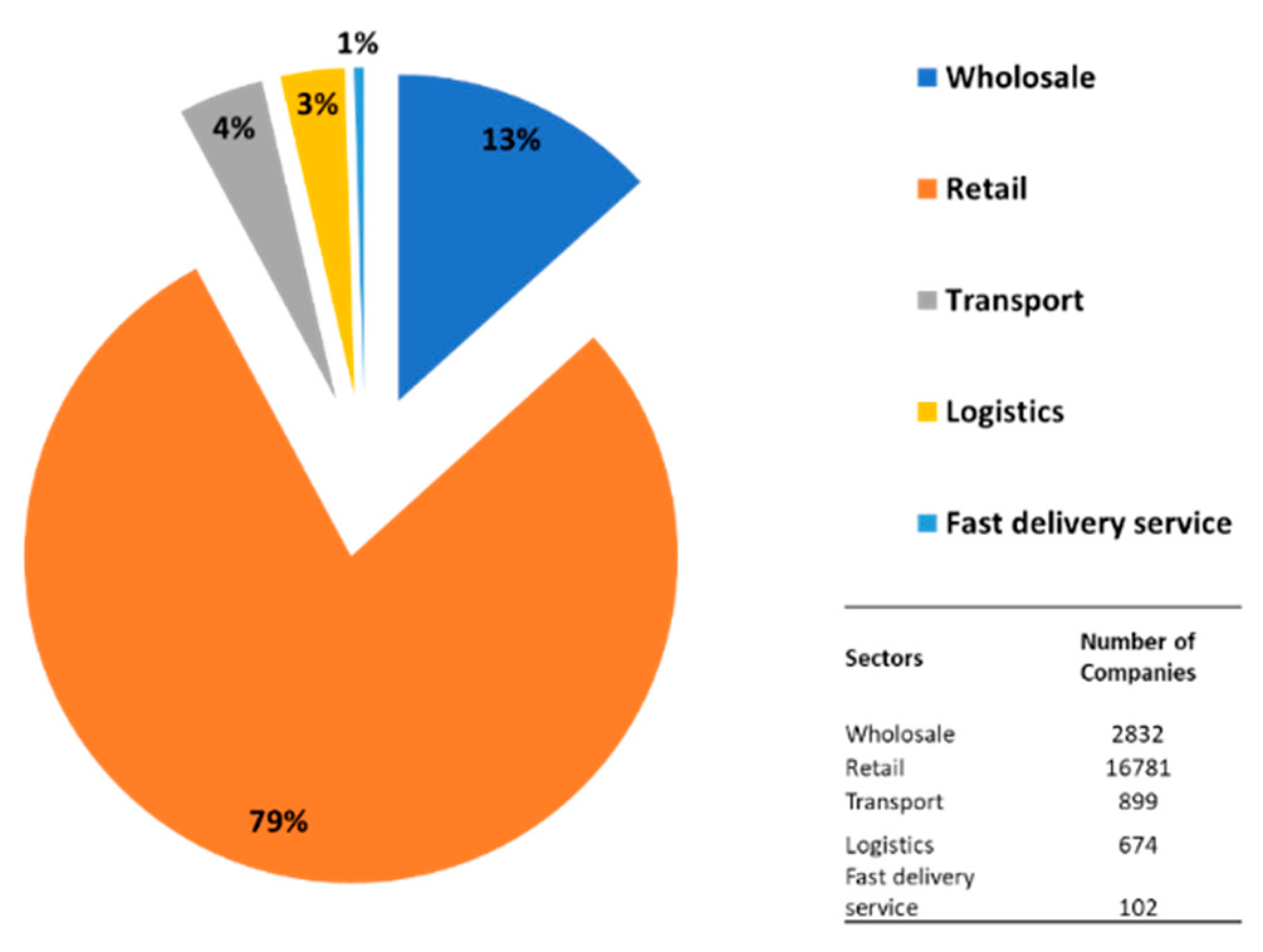

22]. The city of Campinas was selected for validating the business model. In 2019, as per IBGE statistics, Campinas housed 46,979 companies. This companies were categorized into wholesale (13.3%), retail (78.8%), transport (4.2%), logistics (3.2%), and fast delivery services (0.5%), making a total of 21,288 companies, as depicted in

Figure 4.

4.2. Analysis of Shipper and Transport Sectors

The comprehensive report [

22] was compiled using primary sources like database along with interviews and surveys conducted in Campinas, Brazil. The research engaged 179 stakeholders, comprising 128 in-person interviews and 51 remote interviews from diverse sectors such as transport, wholesale, and retail. The analysis focused on the most relevant responses across all subjects.

4.2.1. Analysis of Shipper

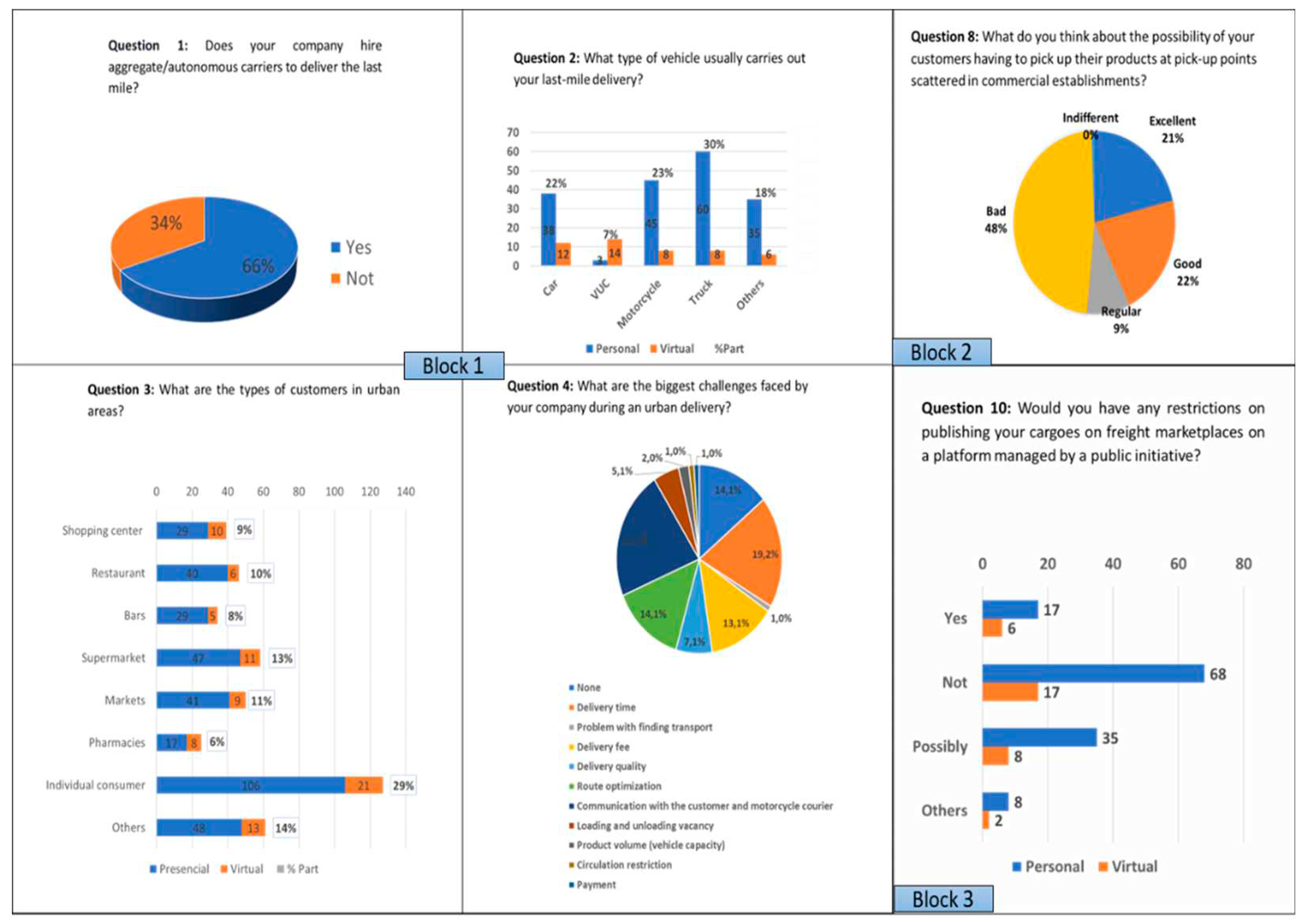

This segment encapsulates the interviews conducted with shippers (

Figure 5).

In Block 1, covering questions 1 to 4, discussions revealed that 66% of the surveyed businesses favored aggregate transportation. Trucks were the top choice for 30% of respondents for large deliveries outside the city center, while motorcycles were favored for 23% of respondents for specific deliveries within the city center.

In Block 2, focused on product collection from established points or warehouses, it was found that while this approach might save time and improve deliveries, it wasn’t ideal. Factors like client preferences, product quality assessment, safety, and added costs hindered its viability.

Block 3 highlighted public initiatives emphasizing the need for reassess regulation, access, trust, and logistics. While 23% respondents wouldn't adopt the platform due to these concerns, 43 were open to engaging with a privately operated platform.

Block 4 revolved around opinions on technology and innovation. Around 76.40% suggested developing a mobile application for both clients and company desktops, accommodating various user preferences and enhancing interaction.

4.2.2. Analysis of the Transport Sector

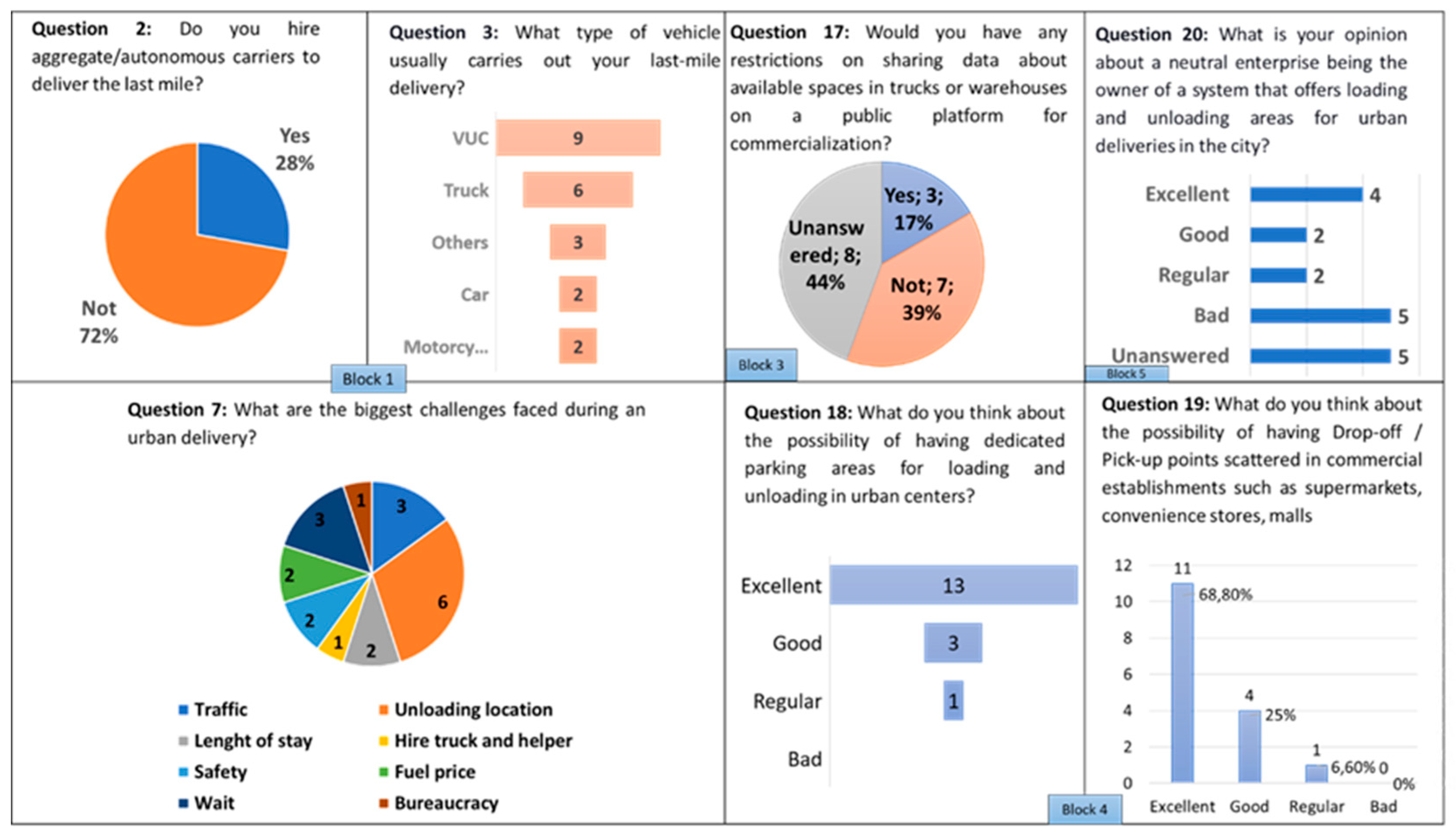

This section presents a summary of interviews conducted within the transport sector (

Figure 6).

Starting with Block 1, which covers industry insights, a crucial aspect of the logistics sector is its vehicle fleet. This fleet consists of the vehicles owned by the logistics companies, enabling the execution of their operational functions. Notably, 28% of companies do not employ aggregate/autonomous transport, while 72% opt for outsourced transport. Interestingly, even companies with their own fleets occasionally resort to outsourcing services. The predominant vehicle preference among surveyed carriers is the Urban Cargo Vehicle, representing 52.9% of respondents. Carriers confronted challenges in fulfilling last-mile deliveries, with the main obstacle arising from a lack of available unloading space. Additionally, extended waiting times for unloading and urban traffic pose significant challenges. The study also underscores critical issues such as the elevated fuel costs, prolonged stays, and security concerns within certain urban sectors.

Block 2, focusing on legislative frameworks and public sector initiatives, with the cargo resolution being a standout. This resolution aims to regulate vehicle movement, enhance traffic conditions within the city, and mitigate conflicts arising from space allocation among cars, trucks, and public vehicles. Moreover, it strives to minimize urban pollution and noise, thereby improving residents' quality of life. Impressively, 60% of interviewed carriers have adapted to these resolutions without compromising their delivery operations, while 40% reported some impact on their deliveries due to these regulations.

Block 3, focuses on shared transport and supply chain networks like logistics clusters, highlighting their substantial time and cost advantages. Bundling, specifically, is a cost-effective strategy for small shipments, providing access to affordable and reliable logistics services while ensuring punctual deliveries. Intriguingly, 39% of surveyed companies express willingness to share data about available truck or warehouse spaces on a public platform for commercial purposes.

In Block 4, addresses a key challenge in the transport and logistics sector: packaging, loading, and unloading processes. The limited space in urban centers and the high volume of users lead to conflicts among stakeholders. Significantly, 76% of companies advocate for exclusive loading and unloading zones within urban centers, with 17.64% considering the idea favorable, and 5.8% finding it acceptable.

Furthermore, when considering the concept of product collection or delivery at designated points, 68.8% of companies find the establishment of Drop-off / Pick-up Points in commercial venues such as supermarkets, convenience stores, and shopping centers as highly beneficial. Meanwhile, 25% view the idea favorably, and 6.6% consider it average.

Transitioning to Block 6, centered on carriers and information technology, companies are increasingly adopting digital tools like computers and the internet to streamline their business systems, enabling product sales for customers working remotely or from home. Hence, understanding user preferences for the User-Last-Mile-as-a-Service (ULMaaS) interface is imperative. Interviews reveal that 61% of operators prefer a platform interface developed as a mobile application for both clients and company desktops. In contrast, 28% prefer exclusively using a mobile application, while 11% opt for a mobile application on their computers.

It is important to note that this section comprises responses from just 17 companies that agreed to complete the entire survey.

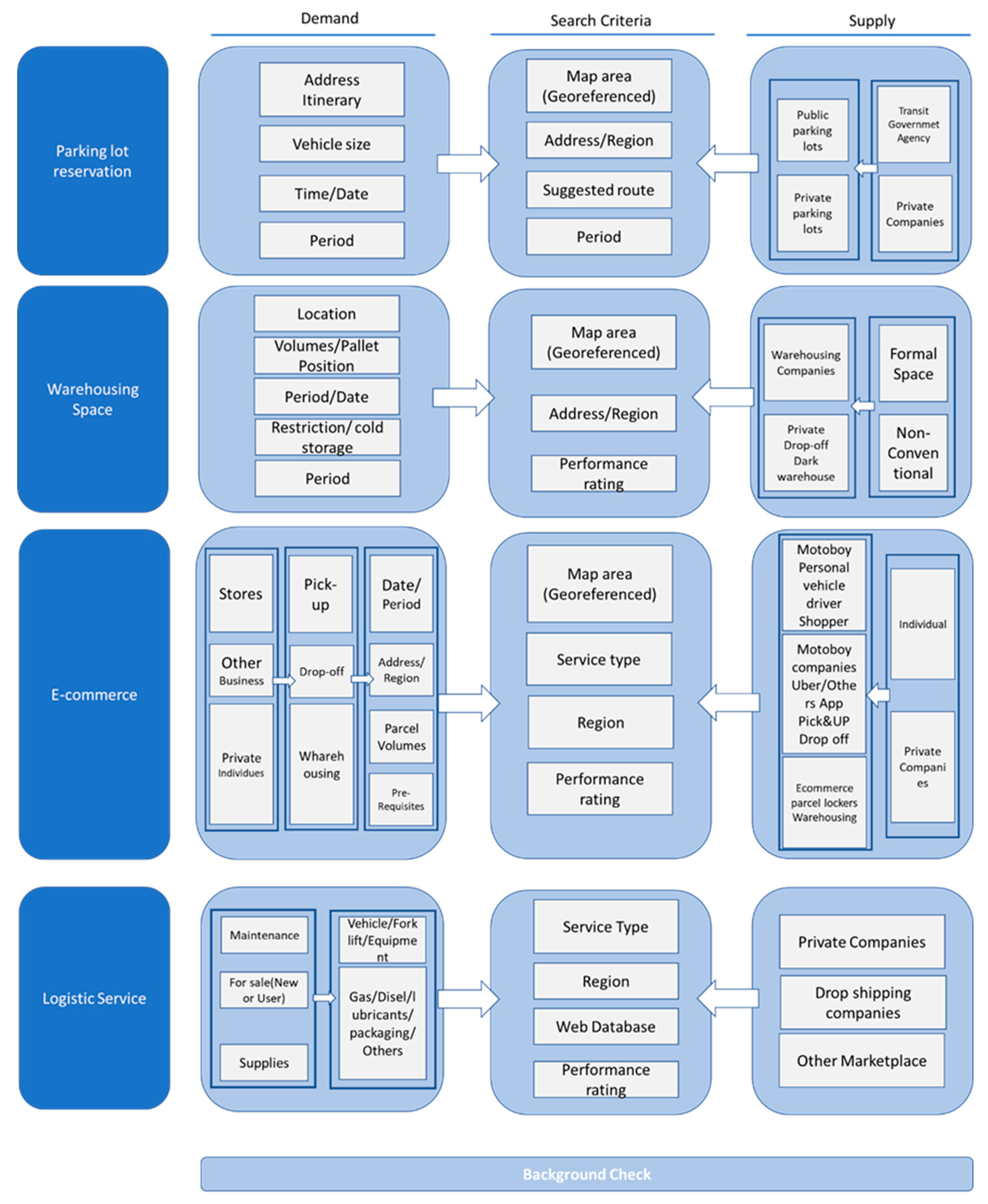

4.3. Model update after Surveys Results

The integration of a business model with a behavioral analysis of the shipper and transport sector has led to the identification of value-generating modules for stakeholders: "Parking Space Reservation," "Warehousing Spaces," "E-commerce," and "Logistics Services" (

Figure 7).

For in-depth information on each module, please refer to [

41].

Figure 8 depicts the ULaaS concept, where all modules showing connections between supply and demand based on specific search criteria. It is important to note that suppliers must undergo a comprehensive background check before including their services or products within each module.

The "Parking Space Reservation" module addresses the need for additional parking areas for urban delivery vehicles. On the demand side, it allows companies to reserve spaces for unloading products, ensuring dedicated spots. As for the supply side, public or private entities can offer these spaces for reservation. Effective management is key to its success.

The "Warehousing Spaces" module optimizes available formal and informal storage spaces, boosting warehouse efficiency and aiding businesses in expanding their storage capacity. From the demand perspective, ULaaS empowers companies to access these spaces, whether public or private. On the supply side, storage companies can rent out their spaces.

The "E-commerce" module serves as a platform for both seeking and offering collection, delivery, or storage services. It includes essential information such as location, parcel volume for collection, delivery or storage dates, times, and specific requirements. Both Private or public enterprises can present their offers; however, private entities like motorcycle delivery companies, ride-sharing services such as Uber, and storage providers, must undergo a thorough background check before approval.

The "Logistics Services" module facilitates the search for goods available for purchase (such as vehicles, forklifts, and equipment). It also includes a search feature for maintenance services like fueling and lubrication. Private companies can list their offerings in the logistics service marketplace

A comprehensive guide to utilizing these modules is provided in reference [

42].

5. Conclusions

The innovative ULaaS business model shows the potential for effective public-private collaboration in platform operation. However, a comprehensive financial and economic analysis is crucial to better understand its viability. Adopting ULaaS can significantly shape urban logistics systems through sharing economy principles, enhancing efficiency and creating new business opportunities. Notably, the platform's establishment is expected to generate positive externalities in public policy by facilitating direct communication among diverse urban logistics stakeholders, promoting improved vehicle utilization and urban area efficiency. Sharing platform data with policymakers can refine traffic management and infrastructure investments, curbing environmental externalities such as pollution and CO2 emissions. Given its capacity to optimize fleet use and alleviate congestion, the platform directly addresses environmental concerns.

Integrating technologies like Big Data, 5G, and machine learning has the potential to enhance IoT applications within digital platforms like ULaaS. By combining higher speeds and bandwidth with AI capabilities, various possibilities emerge, allowing for superior control and load tracking. This technological synergy also positively impacts workforce conditions. Leveraging these technologies is vital for the success and market positioning of companies. Therefore, the transport sector should capitalize on the opportunities provided by a ULaaS platform grounded in IoT applications. To fully harness these benefits, collaboration with specialized companies proficient in integrating digital solutions is essential. To address diverse logistics challenges and provide intelligent solutions crucial for enterprises like e-commerce, the authors have formulated four modules within the platform, creating a specialized hub for comprehensive management.

While a marketplace like ULaaS offers numerous advantages, certain limitations remain. The platform doesn't directly engage with customers; but acts as an intermediary between customers and the marketplace. Market conditions can change, affecting pricing and terms. Although direct competition might be absent, indirect competition arises from multiple partners offering similar services through different stores. While the shopping experience can be customized to some extent, potential changes in shipping and after-sales processes must be considered.

This paper introduces an innovative digital business model focused on a service-oriented urban logistics platform. Additionally, the study presents various monetization models and outlines necessary investments, addressing a crucial aspect in evaluating potential private involvement.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: R. Fioravanti, O. Lima Jr.; data collection: G. Montoya; analysis and interpretation of results: R. Fioravanti, O. Lima Jr. G. Montoya; draft manuscript preparation: R. Fioravanti, O. Lima Jr. G. Montoya, J. A. Pinto. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions privacy. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to privacy concerns.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Frischtak, C. R.; Davie K.; J. Noronha. O financiamento do investimento em infraestrutura no Brasil: uma agenda para sua expansão sustentada. Econômica, 2015, 17, pp. 2.

- Diziain, D., E. Taniguchi; L. Dablanc. Urban logistics by rail and waterways in France and Japan. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2014, 125, pp. 159-170. [CrossRef]

- MTPA. Anuário Estatístico de Transportes 2010-2016 (Statistical Yearbook of Transport 2010-2016), Ministry of Transport, Ports and Civil Aviation, Brasilia, 2017.

- World Bank. https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/2018-revision-of-world-urbanization-prospects.html#:~:text=News-,68%25%20of%20the%20world%20population%20projected%20to%20live%20in,areas%20by%202050%2C%20says%20UN&text=Today%2C%2055%25%20of%20the%20world’s,increase%20to%2068%25%20by%202050. Accessed 15 January 2021, 2017.

- Taniguchi, E. and R. G. Thompson Innovations in city logistics. In International Conference on City Logistics, 5th, 2007, Crete, Greece.

- Taniguchi, E.; R.G Thompson; T. Yamada (2008) Modelling the behaviour of stakeholders in city logistics. In International Conference on City Logistics, 5th, 2007, Crete, Greece.

- Dablanc, L. Goods transport in large European cities: Difficult to organize, difficult to modernize. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 2017, 41, 3, pp. 280-285. [CrossRef]

- Montoya, G. N.; J. B. S. Santos Junior; A. G. Novaes; O. F., Lima, February. Internet of Things and the risk management approach in the pharmaceutical supply chain. In International Conference on Dynamics in Logistics, 2018. 284-288. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. C.; J. Yu. A study on the fire IOT development strategy. Procedia Engineering, 2013, 52, pp. 314-319. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H; B. Liu; D. Wang, 2012. Design and research of urban intelligent transportation system based on the internet of things. In Internet of Things 2012. 572-580. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Giret, A. Smart and sustainable urban logistic applications aided by intelligent techniques. Service Oriented Computing and Applications, 2019, 13, 3, pp. 185-186. [CrossRef]

- Jucha, P. Use of artificial intelligence in last mile delivery. In SHS Web of Conferences (Vol. 92). EDP Sciences. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P.; T. Choi; S. Somani; R. Butala. Blockchain technology in supply chain operations: Applications, challenges and research opportunities. Transportation research part e: Logistics and transportation review, 2020, 142, pp. 102067. [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; L. Ma; C. Ying. Matching daily home health-care demands with supply in service-sharing platforms. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 2021, 145, pp. 102177. [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; W. Zhou; S. Piramuthu; V. Giannikas; C. Chen. Smart city for sustainable urban freight logistics. International Journal of Production Research, 2021, 59, 7, pp. 2079-2089. [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.; D. A. Hensher. Towards a framework for Mobility-as-a-Service policies. Transport policy, 2020, 89, pp. 54-65. [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y. Z.; D. A. Hensher; C. Mulley. Mobility as a service (MaaS): Charting a future context. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 2020, 131, pp. 5-19. [CrossRef]

- Becker, H.; M. Balac, F. Ciari; K. W. Axhausen. Assessing the welfare impacts of Shared Mobility and Mobility as a Service (MaaS). Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 2020, 131, pp. 228-243. [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, P. E.; M. Collado; S. Sarasini; M. Williander. Mobility as a Service-MaaS: Describing the framework. In Tuesday, February 16, 2016.

- Shafer, Scott M.; H. Jeff Smith; Jane C. Linder. The power of business models. Business horizons (2005). 48.3:199-207. [CrossRef]

- Klingebiel, K.; A. Wagenitz. An introduction to logistics as a service. In Efficiency and logistics 2013. 209-216. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Fioravanti, R.; Fontes Lima, O.; Montoya G. Logística urbana como serviço (ulaas): um teste de conceito. In Associação Nacional de Pesquisa e Ensino em Transportes (ANPET), 2022.

- MaaSLab, The MaaS Dictionary. https://www.maaslab.org/_files/ugd/a2135d_d6ffa2fee2834782b4ec9a75c1957f55.pdf. Accessed 15 June 2021, 2018.

- Merkert, R.; J. Bushell; M.J. Beck. Collaboration as a service (CaaS) to fully integrate public transportation–Lessons from long distance travel to reimagine mobility as a service. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 2020, 131, pp. 267-282. [CrossRef]

- CIVITAS. Urban Logistics as an on-Demand Service. https://civitas.eu/news/new-ulaads-project-deliver-solutions-urban-logistics-demand-economy. Accessed 01 January, 2022.

- Entrance-platform. Alliance for Logistics Innovation through Collaboration in Europe – ALICE. https://www.entrance-platform.eu/constortium/alliance-for-logistics-innovation-through-collaboration-in-europe/ Accessed 01 November 2021. 2021.

- Urbantz, 2022. Empresas de logística. https://urbantz.com/es/solutions/logistics/ Accessed 15 July 2021.

- Airme. Perfecting the Delivery Experience. https://airmee.com/platform/ Accessed 01 November 2021.

- PTV Group. 2022. Soluciones de software para la movilidad. Accessed 15 November 2021: https://company.ptvgroup.com/es/productos.

- LEAD, 2022. LEAD Strategies for shared-connected and low-emission logistics operations. Accessed 23 July 2021: https://www.leadproject.eu/.

- Massa, L.; Tucci, C.; Afuah; Allan A. Critical Assessment of Business Model Research. Academy of Management Annals, (2017). 11, 1: 73–104. [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, Bernd W. Digital business models: Concepts, models, and the alphabet case study. Springer, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Spieth, P.; Schneider, S. Business model innovativeness: designing a formative measure for business model innovation. Journal of business Economics, 2016, pp. 86, 671-696. 10, 4: 249-251. [CrossRef]

- Upward, A.; Jones, P. An ontology for strongly sustainable business models: Defining an enterprise framework compatible with natural and social science. Organization & Environment, 2016, 29, 1, pp. 97-123. [CrossRef]

- Broccardo, L.; Zicari, A.; Jabeen, F.; Bhatti, Z. A. How digitalization supports a sustainable business model: A literature review. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 2023, 187, pp. 122146. [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Hansen, E. G.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business models for sustainability: Origins, present research, and future avenues. Organization & Environment, 2016, 29, 1, pp. 3-10.

- Bocken, N. M. P.; Rana, P.; Short, S. W. Value mapping for sustainable business thinking. Journal of Industrial and Production Engineering, 2015, 32, 1, pp. 67-81. [CrossRef]

- Sparviero, S. The case for a socially oriented business model canvas: The social enterprise model canvas. Journal of social entrepreneurship, 2019. 10, pp. 232-251. 10. [CrossRef]

- Villela, T. Structure for operating ports with private port authorities. PHD Thesis, UNB Brazil (2013).

- Lessard, D.; Miller, R. The strategic management of large engineering projects, (2001).

- Fioravanti, R.; Lima Jr, O.; Montoya G.; Pinto J. ULaaS: Urban Logistics as a Service – a conceptual platform for digital transformation of logistics services in urban areas. Transportation Research Procedia. 2023, World Conference on Transport Research - WCTR 2023 Montreal 17-21 July 2023.

- Shaheen, S.; Cohen, A.; Zohdy, I. Shared mobility resources: Helping to understand emerging shifts in transportation. Policy Briefs, 2017.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).