1. Introduction

Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) is a benign, mostly solitary liver lesion originating from hepatocytes [

1]. It is the second most common benign liver lesion with no evidence of malignant transformation [

2,

3]. The incidence has a female predominance with ratios ranging from 8:1 to 12:1 [

4]. The majority of FNHs are asymptomatic and found incidentally [

1]. Diagnosis is usually made by CT or MRI by distinct features including the presence of a central scar and central artery. After contrast administration, FNH shows early arterial enhancement in imaging [

5]. In MRI imaging, FNH remain hyper-/isointense in venous phases and hepatobiliary imaging helps to distinguish FNH from hepatic adenomas. In asymptomatic patients FNH treatment is not necessary, but a reliable diagnosis is crucial. We report a case series of three female patients with tumors radiologically highly suspicious for a FNH that turned out to be histologically proven hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

3. Results

We encountered three female patients with a HCC, which were each primarily diagnosed as FNH, based on imaging modalities with typical central scarring. All three were solitary tumors in a non-cirrhotic liver and without underlying liver disease. The patients were sent to our center for a second opinion or further treatment mainly because of the size of the tumor. Patients’ characteristics, surgical procedure, histological outcome, and further information are shown in

Table 1.

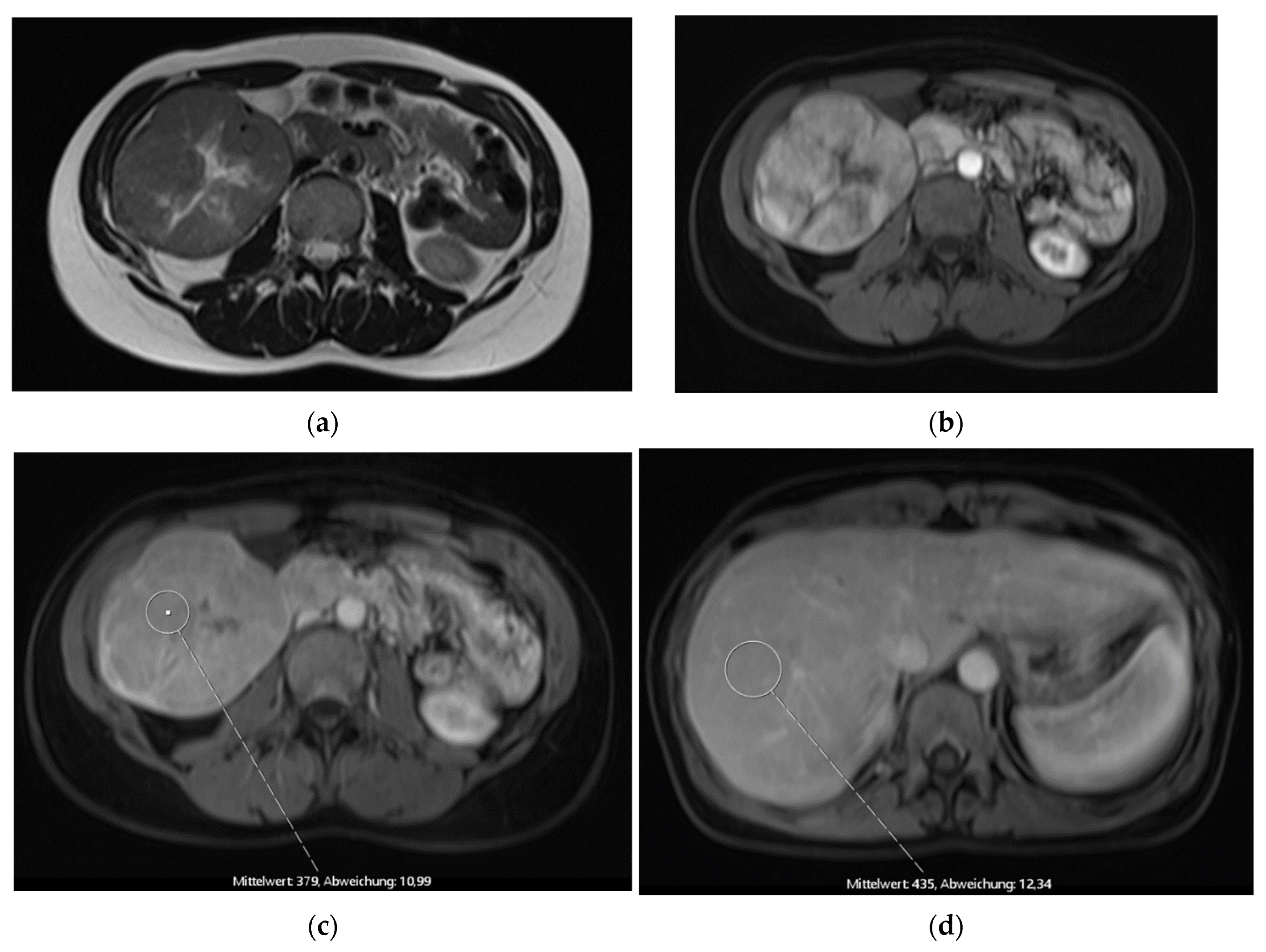

3.1. Case 1

The first patient was a 41-year-old female who was referred for a second opinion after receiving the diagnosis of a large FNH of the right liver lobe (

Figure 1). AFP was within normal range. We indicated the explorative laparotomy due to a slight washout phenomenon in the venous phase which is not entirely typical for a FNH. Intraoperative frozen section showed a hepatocellular carcinoma and a bisegmental resection of the segments 5 and 6 (H56 according to the ‘New World’ terminology [

6]) plus hilar lymphadenectomy was performed. Postoperative course was uneventful but early recurrence was diagnosed after four months and repeated resection was performed (H8′). A second recurrence led to a completion as formal right hemihepatectomy (H78) and subsequent treatment with Sorafenib. In the further course a local therapy with TACE was conducted after findings of a third recurrence. The patient passed away two years after the primary diagnosis of HCC.

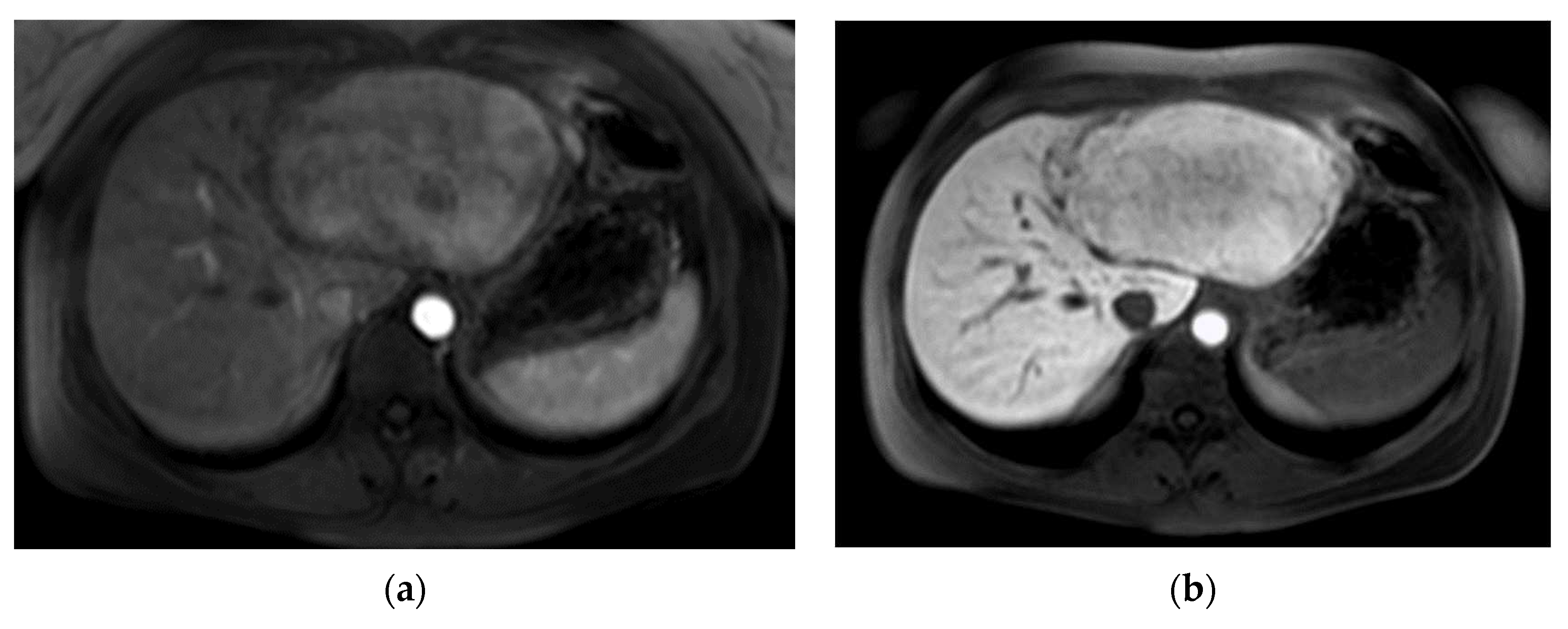

3.2. Case 2

The second patient was referred to our out-patient clinic with a liver lesion of the left lobe, which had been growing constantly over 7 years. A FNH had been diagnosed at the age of 23, which met the typical MRI-criteria including contrast retention in hepatobiliary imaging and the patient was in regular follow-ups (

Figure 2). Because of the tumor growth and inhomogeneity along the tumor capsule we performed a left hepatectomy (H234′) (

Figure 2d). The final histological findings revealed a HCC and the patient is in regular follow-ups since without evidence of recurrence for over 44 months until today.

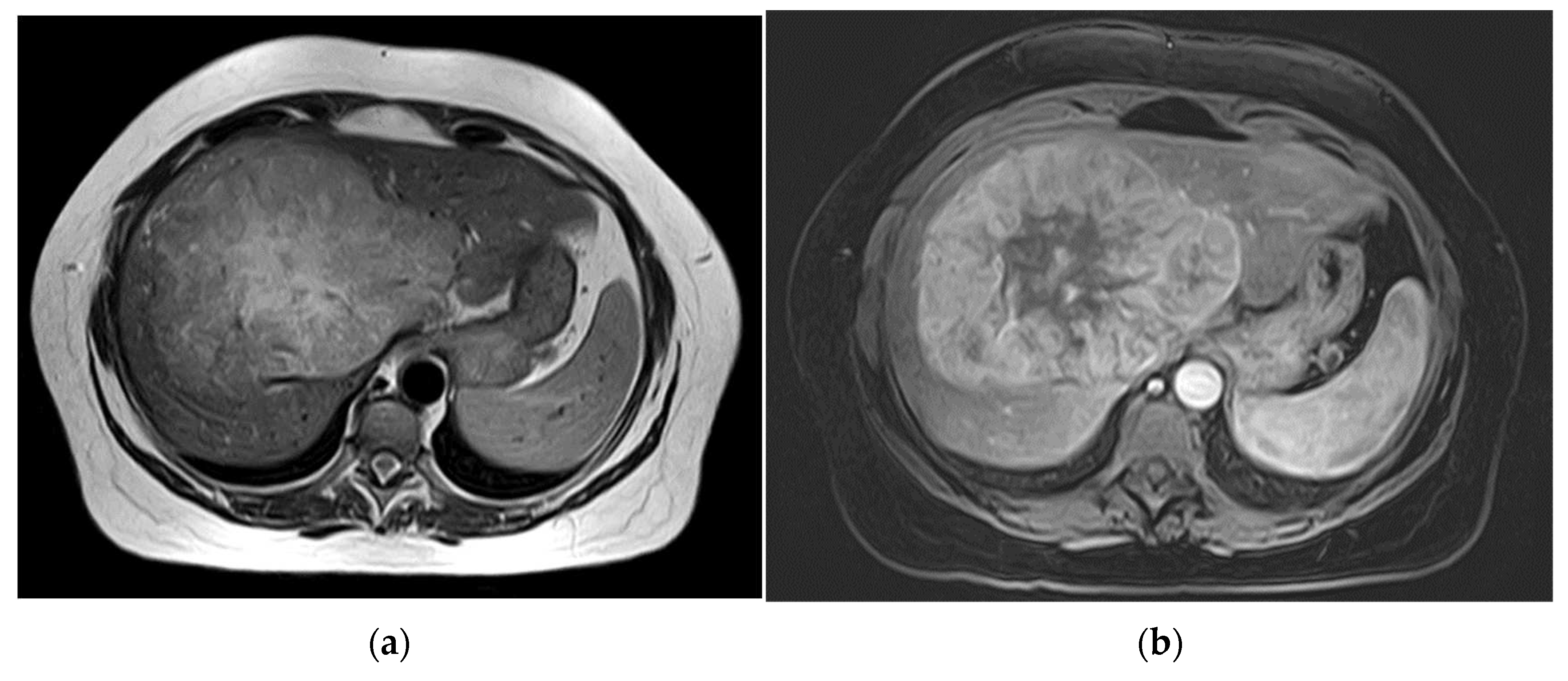

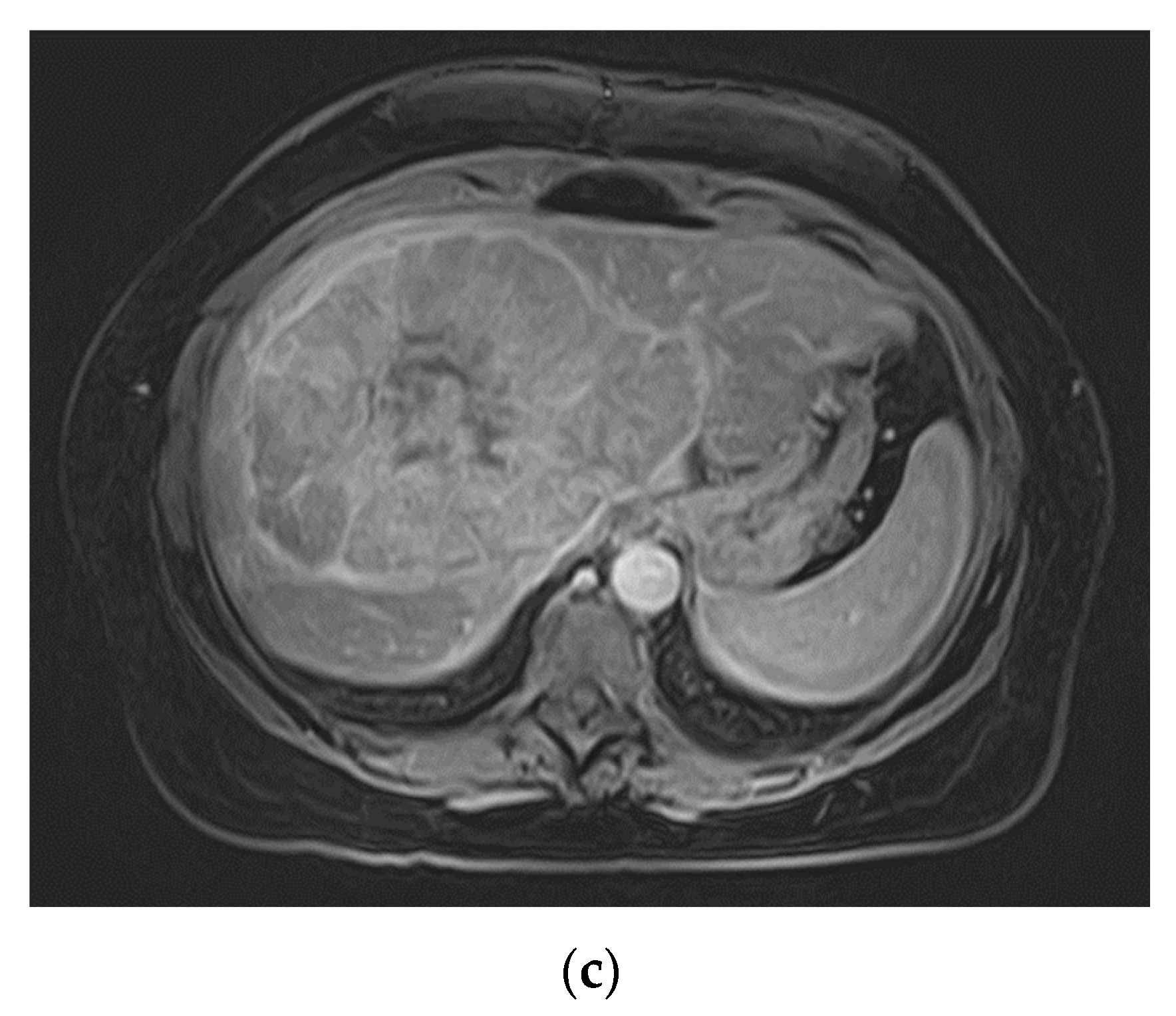

3.3. Case 3

The third patient was 53 years old when a FNH was diagnosed in MRI (

Figure 3). Comparable to patient 1, no dedicated delayed hepatobiliary phase had been was performed. A follow-up after 3 months was scheduled, this time with Alpha-1 Fetoprotein (AFP) as laboratory testing, which turned out to be significantly increased with a value of > 400000ng/ml. At presentation at our center four weeks later the AFP had risen to 980,128 ng/ml. We conducted a central resection of segments 4, partially 5 and 8 as well as Segment 1 (H145′8′-RHV). Resection and reconstruction of the right hepatic vein was necessary to achieve R0-status. The patient is tumor-free within follow-up for 20 months until today. In the postoperative course the AFP levels decreased to 5529 ng/ml after one month, to 4.9 ng/ml after three months, and remained below 2.5 ng/ml since seven months after resection.

4. Discussion

We report on a series of three female patients with solitary liver tumors initially suspected to be FNH because of the arterial enhancement pattern and a supposedly central scar in a solitary tumor. All patients presented at our center for a second opinion and evaluation of further treatment with large tumors between 10 to 24 cm in diameter. None had cirrhosis or any underlying liver disease. A biopsy was not obtained in any of the three cases prior to surgery. The histology revealed well to poor differentiated HCCs with a 8th edition TNM classification status varying from pT1 to pT2 [

7]. One patient developed recurrence and metastatic disease and deceased in the course of time.

The diagnosis of a FNH is often an incidental finding, as they are rarely symptomatic. The main patient group are young females at the age of 20 to 50 years. Sporadic cases of male patients with a FNH have been described [

8]. The lesions tend to grow slowly or show no growth at all.

The specific features in CT- and MRI-scans often lead to the diagnosis of FNH. Presentation of the imaging to a radiologist with specific hepatobiliary expertise should be considered. The EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of benign liver tumours suggests the use of MRI with hepatotropic contrast agent to be the more sensitive imaging modality to diagnose FNH compared to a multi-phase CT-scan [

10]. In our case series, only one of the three patients underwent MRI with hepatotrophic contrast media. If an MRI with a hepatotropic contrast agent does not lead to a safe diagnosis, an additional contrast enhanced ultrasound is advised. In a safely diagnosed asymptomatic FNH, no further treatment is recommended [

9].

Even though FNH tends to show a distinct pattern in imaging modalities, HCC can mimic a benign lesion as shown. For example, about 20% of HCC display an uptake of contrast agent in late phases [

11]. But in contrast to HCC, a FNH does not show any washout appearance [

12]. In CT-scans FNH show a distinct morphology with a central vascular supply [

13]. In MRI it is iso- or hypointense in T1 and hyper- or isotense in T2-weighted imaging and shows a T2w-hyperintense central element/scar which enhances on delayed-phase imaging when extracellular contrast agents are used [

14]. The central scar is found only in about 30-50% of FNH in MR-imaging and in literature not correlated with the size of the lesion [

15]. Furthermore, in about 50% of HCC in non-cirrhotic livers a central scar is also present [

10]. It appears that in larger lesions the prominent central scar with radiating fibrous septa can be less distinct due to the general mass of the lesion. Whether this observation should lead to even greater attention to the diagnostic and differential diagnosis of FNH of large lesions, is to be discussed.

When there are still doubts, a biopsy is recommended to secure the diagnosis. The general issue with biopsies is the concern for needle track seeding or missing malignant parts. Another problem is the difficulty to differentiate FNH-tissue from well-differentiated HCC or fibrolamellar HCC in a biopsy sample [

16]. So even with a histology ruling out malignant cells in the biopsy, uncertainty remains.

One of our patients had an extremely high level of AFP preoperative with explicit decrease after resection. In patient 2 the AFP unfortunately was not measured prior to the resection. An increased level of AFP is usually associated with HCC and it used widely for screening in high-risk patients and for HCC follow-ups [

18]. AFP can be increased slightly (up to 100 ng/ml) in liver cirrhosis and in chronic hepatitis as well [

19], but also in pregnancy or teratoma [

20]. AFP is typically not elevated in a FNH but some rare cases with elevated AFP in FNH have been reported in a range of 40–60 ng/ml [

21,

22]. One assumes that in these cases AFP expression is caused by a regenerative process due to features of progenitor cells within the FNH or even in the non-lesional adjacent liver [

23]. Measurement of AFP levels in every newly diagnosed liver lesion is highly recommended. A high AFP level or an increase over a short period of time would be suspicious for HCC.

The numbers of resections for benign liver tumors have risen in recent years due to various reasons including a broader access to imaging modalities and the emergence of minimal invasive surgery, but generally an over-therapy via surgery should be avoided. If the diagnosis is certain and the tumor is asymptomatic then there is no indication for surgery. On contrast, if there are any indeterminate features in MRI, CT-scan and ultrasound with respective contrast agents, or a noteable elevation of AFP levels or a measurable tumor growth surgery should be offered to the patient [

17]. Otherwise, a close follow-up with imaging and AFP-level control should be performed.

5. Conclusions

HCC can mimic FNH leading to a delay of necessary treatment. FNH is a benign tumor of the liver which, if asymptomatic, does not need to be treated surgically. For the diagnosis of a FNH usually a contrast enhanced MRI scan is sufficient. Normally AFP is not increased. However, cases with progression in size, an elevated AFP level and especially a further increase of AFP are suspicious. A second opinion at a center for hepato-biliary surgery with HCC/FNH-experienced radiologists and surgeons is reasonable. Generally, an over-therapy via surgery should be avoided and follow-ups of a newly diagnosed FNH including measurement of AFP are advisable to detect alterations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Lisa-Katharina Gröger and Fabian Bartsch; methodology, Fabian Bartsch; radiological analysis, Felix Hahn; validation, Hauke Lang; formal analysis, Lisa-Katharina Gröger; investigation, Lisa-Katharina Gröger; resources, Lisa-Katharina Gröger and Beate K. Straub; data curation, Lisa-Katharina Gröger; writing—original draft preparation, Lisa-Katharina Gröger; writing—review and editing, Fabian Bartsch and Felix Hahn; visualization, Lisa-Katharina Gröger; supervision, Hauke Lang; project administration, Hauke Lang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

This publication deals with a case series. Data availability does not apply accordingly. In case of queries contact the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Myers, L. AJ Focal Nodular Hyperplasia and Hepatic Adenoma: Evaluation and Management. Clin Liver Dis. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldhafer, K.J.H.V.; Horling, K.; Makridis, G.; Wagner, K.C. Benign Liver Tumors. Visc Med. 2020, 36, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor M, P.F.; Braunwarth, E; et al. Indications for liver surgery in benign tumours. Eur Surg. 2018, 50, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahm, C.B.N.K.; Lockie, P.; Samra, J.S.; Hugh, T.J. Focal Nodular Hyperplasia—A Review of Myths and Truths. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieze, M.B.O.; Tanis, P.J.; Verheij, J.; Phoa, S.S.; Gouma, D.J.; van Gulik, T.M. Outcomes of liver resection in hepatocellular adenoma and focal nodular hyperplasia. HPB (Oxford). 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagino, M.; et al. Proposal of a New Comprehensive Notation for Hepatectomy: The “New World” Terminology. Ann Surg 2021, 274, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brierley, J.; et al. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 8th ed.; Wiley Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hamada, K.S.S.; Nishino, N.; Fukushima, D.; Techigawara, K.; Koyanagi, R.; Horikawa, Y.; Shiwa, Y.; Sakuma, H.; Kondo, F. An elderly man with progressive focal nodular hyperplasia. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- (EASL), EAftSotL. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of benign liver tumours. J Hepatol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicki, T.K.M.K.; Izycka-Swieszewska, E.; Dziadziuszko, K.; Studniarek, M.; Szurowska, E. Efficacy comparison of multi-phase CT and hepatotropic contrast-enhanced MRI in the differential diagnosis of focal nodular hyperplasia: A prospective cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitao, A.Z.Y.; Matsui, O.; Gabata, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Koda, W.; Kozaka, K.; Yoneda, N.; Yamashita, T.; Kaneko, S.; Nakanuma, Y. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Signal intensity at gadoxetic acid-enhanced MR Imaging--correlation with molecular transporters and histopathologic features. Radiology. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grazioli, L.B.M.; Haradome, H.; Motosugi, U.; Tinti, R.; Frittoli, B.; Gambarini, S.; Donato, F.; Colagrande, S. Hepatocellular adenoma and focal nodular hyperplasia: Value of gadoxetic acid-enhanced MR imaging in differential diagnosis. Radiology. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancatelli, G.F.M.; Grazioli, L.; Blachar, A.; Peterson, M.S.; Thaete, L. Focal nodular hyperplasia: CT findings with emphasis on multiphasic helical CT in 78 patients. Radiology 2001, 219, 61–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortele, K.J.; Praet, M.; Van Vlierberghe, H.; Kunnen, M.; Ros, P.R. CT and MR Imaging Findings in Focal Nodular Hyperplasia of the Liver Radiologic—Pathologic Correlation. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2000, 175, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bioulac-Sage, P.B.C.; Wanless, I. Diagnosis of Focal Nodular Hyperplasia: Not So Easy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001, 25, 1322–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaoka, J.S.M.; Utsunomiya, T.; Imura, S.; Morine, Y.; Ikemoto, T.; Mori, H. Huge focal nodular hyperplasia difficult to distinguish from well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kammula, U.S.B.J.; Labow, D.M.; Rosen, S.; Millis, J.M.; Posner, M.C. Surgical management of benign tumors of the liver. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, Y.J.Y.; Sun, H.; Zhou, S. The Diagnostic Value of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound and Enhanced CT Combined with Tumor Markers AFP and CA199 in Liver Cancer. J Healthc Eng. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.L.Z.L.; Li, F.Q.; Liang, Y.H.; Wei, Q.Z.; Liu, L.X.; Cui, H.Y. Treatment of a non-typical hepatic pseudolesion complicated by greatly elevated alpha fetoprotein: Case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowberger, N.C.S.; Lepe, R.M.; Peattie, J.; Goldstein, R.; Klintmalm, G.B.; Davis, G.L. Alpha fetoprotein, ultrasound, computerized tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for detection of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.L.B.; Yuan, Y.F.; Cui, B.K.; Li, J.Q.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Li, G.H. Clinical analysis of 38 cases of hepatic focal nodular hyperplasia and literature review. Ai Zheng. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carrier, P.G.A.; Debette-Gratien, M.; Fredon, F.; Teissier, M.P.; Labrousse, F.; Loustaud-Ratti, V. Alpha-fetoprotein and focal nodular hyperplasia: An unconventional couple. JGH Open. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mneimneh, W.W.M.; Farges, O.; Bedossa, P.; Belghiti, J.; Paradis, V. High serum level of alpha-fetoprotein in focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver. Pathol. Int. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).