1. Introduction

Leaves are the primary organs responsible for photosynthesis and transpiration in plants[

1]. Photosynthesis in leaves has a profound impact on a plant’s growth, development, ecological benefits, and timber production[

2,

3]. Unlike smooth-edged leaves, serrated or lobed leaves provide a larger surface area and greater spatial expansiveness, making them advantageous for light absorption. This offers a competitive edge in light acquisition[

4]. Additionally, these leaves possess enhanced aesthetic value.

The European birch, scientifically known as

Betula pendula, is one of the most widely distributed tree species within the Birch genus, with extensive growth across the northern frigid regions of Eurasia. It holds significant practical value and developmental potential. This species exhibits strong cold resistance, has a deep-rooted system, thrives in poor soil conditions, and features an elegant stem structure, pristine bark, and gently cascading branches. As a result, it finds extensive utility in urban landscaping. The serrated-leaf birch, also known as

B.pendula ’Dalecarlica’ represents a variant of the European birch. Its leaves exhibit shallow serrations with elongated tips, prominent veins on the leaf undersides, significantly enlarged cross-sectional areas of internal mechanical transport tissues, and a more pronounced presence of epidermal trichomes on the leaf undersides[

5].

Birch is a monoecious species, but in the case of serrated-leaf birch, the male flowers are sterile. Consequently, it can only serve as the female parent for hybridization with European birch, leading to trait segregation in the offspring, with the majority displaying non-serrated leaves[

6]. To ensure a higher proportion of plants in the next generation with consistent hereditary traits, plant tissue culture proves to be one of the most effective propagation methods. However, during asexual reproduction, serrated-leaf birch may undergo a random reversion mutation, resulting in the disappearance of serrations, and leaves reverting to their natural ovate or cordate shape. This phenomenon of reversion mutation can be reversed through treatment with 5-azacytidine (5-AzC), indicating a link between leaf morphological changes in serrated-leaf birch and epigenetics, particularly DNA methylation[

7].

DNA methylation in eukaryotes can be classified into symmetric CG, CHG, and asymmetric CHH (with H representing A, T, or C) types. CHH methylation is a unique feature of plants and is established and maintained through the RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway[

8]. These modifications play a controlled role in regulating the expression of neighboring genes[

9,

10]. Consequently, without altering the DNA sequence, they have a profound influence on leaf development and morphogenesis [

11,

12,

13,

14].

The morphological development of plant leaf primordia and young leaves is intricately regulated by the concentration of auxin, specifically Indole-3-Acetic Acid (IAA) [

15]. Understanding leaf morphogenesis is critical for comprehending the formation and development mechanisms of nearly all lateral organs in plants, as these organs’ development is governed by the concentration gradients of auxin [

16,

17,

18]. The Auxin/Indole-3-Acetic Acid (Aux/IAA) gene family encodes short-lived nuclear proteins. In model organisms, these proteins possess specific structural domains that interact with Auxin Response Factors (ARF) and control the transcription of genes activated by ARFs, thus facilitating the transmission of auxin signals [

19].

In previous studies, it was revealed that the

BpIAA10 gene is involved in the development of birch leaves, the formation of dormant buds, the initiation and development of roots and stomata, and high growth. The specific auxin signaling pathways involved in

BpIAA10 transcription factors were summarized, confirming that the birch AUX/IAA family proteins represented by

BpIAA10 perform similar auxin signaling functions [

20], However, no discernible impact of AUX/IAA on the serration of birch leaves has been observed.

This research was centered on an examination of two birch clones: one with serrated leaves and another without serrations, which was derived from the former during plant tissue culture. Employing a range of multi-omics techniques, including whole-genome resequencing, transcriptome sequencing, and methylation profiling, a comprehensive comparative analysis was carried out to elucidate the genomic variations and gene expression modifications between these two clones. The primary objective of this study was to unravel the underlying mechanism responsible for the formation of leaf serrations and to validate the pivotal differential genes involved in this process. The investigation revealed that alterations in DNA methylation levels and the expression of a gene belonging to the AUX/IAA family were the primary drivers of this mutation. This discovery offers valuable insights for refining the birch auxin signal transduction network and can serve as an invaluable resource and theoretical foundation for future birch breeding programs.

2. Materials and Methods

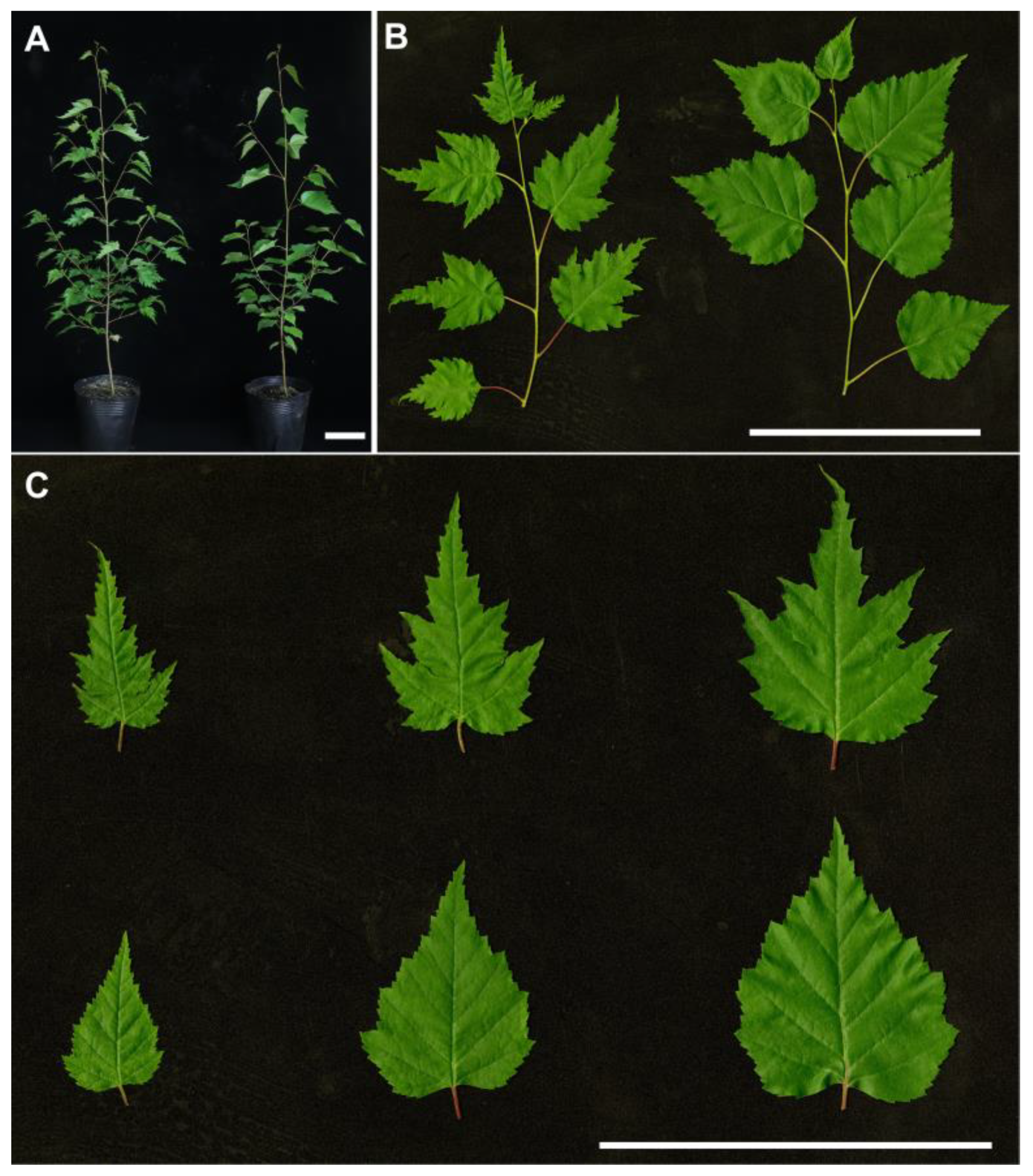

The serrated-leaf birch clone L72 (

Figure 1) was obtained through tissue culture from a selected bud of a high-quality birch tree at the Northeast Forestry University’s Birch Strengthening Seed Orchard. During the tissue culture process, adventitious shoots bearing ovate leaves were differentiated from callus tissue and designated as Y72 (

Figure 1). All plantlets from the test tubes were subsequently transplanted into nursery pots (with a diameter of 18 cm and a depth of 20 cm, using a soil mixture composed of peat soil: vermiculite: perlite in a 3:1:1 ratio). They were then cultivated in the Birch Strengthening Seed Orchard, located at longitude 126.622615 E and latitude 45.716848 N.

2.1. Tissue Culture of Serrated-Leaf Birch

The process of tissue culture for serrated-leaf birch involved the following steps: Collecting axillary buds from selected trees, washing them in distilled water for 12-24 hours, immersing them in 75% ethanol for 1 minute within a clean bench, rinsing with sterile water three times, disinfecting with 30% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes, and rinsing again with sterile water five times. After removing the bud scales, the white meristematic tissue was inoculated into differentiation medium (WPM + 0.8 mg/L 6-BA + 0.02 mg/L NAA + 0.5 mg/L GA3 + 20 g/L sucrose + 5.65 g/L agar + 164 mg/L calcium nitrate). The wounded tissue developed into callus tissue and subsequently produced adventitious shoots. These shoots were transferred to the subculture medium (WPM + 0.8 mg/L 6-BA + 20 g/L sucrose + 5.65 g/L agar + 164 mg/L calcium nitrate), with fresh medium replaced every 25 days. Once the adventitious shoots grew into rootless plantlets, segments approximately 2 cm in height were cut and cultured on rooting medium (WPM + 0.4 mg/L IBA + 20 g/L sucrose + 5.65 g/L agar + 164 mg/L calcium nitrate) for 25-30 days until roots developed. Healthy, aseptic seedlings with well-developed roots, reaching a height of around 7 cm, were transplanted into nutrient pots containing a substrate mixture of peat soil: vermiculite: perlite = 3:1:1. These pots measured 10x10x10 cm and were placed in a greenhouse. Throughout the entire process, the cultivation conditions included a light intensity of 6000-8000 lux, a light/dark cycle of 16 hours/8 hours, an average temperature of 25°C, and a relative humidity of 60-70%.

2.2. Whole Genome Resequencing and Mutation Detection

On July 2, 2022, the fourth leaves of two-month-old serrated-leaf birch L72 and its circular-leaf mutant Y72 (

Figure 1, C, right) underwent whole-genome resequencing. DNA extraction, library construction, and sequencing were conducted by Shanghai LingEn Biotechnology Co., Ltd., employing the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform. Following data filtering with fastp, clean reads were aligned to the reference genome using bwa[

21], and the resulting files were sorted using samtools. Variant detection, encompassing SNPs and InDels, was executed using bcftools [

22]. AnnoSNP was employed for the analysis of the impact of differential SNPs on coding genes, and the variant genes were annotated using eggnog-mapper.

2.3. Transcriptome (RNA-Seq) Sequencing and Analysis

On July 2, 2022, the fourth leaves of two-month-old serrated-leaf birch L72 and its round-leaf mutant Y72 (

Figure 1, A, right) underwent transcriptome sequencing. RNA extraction, library preparation, sequencing, data quality control, and filtering were carried out by Shanghai LingEn Biotechnology Co., Ltd., using the Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform. The sequencing data were aligned to the birch reference genome (CoGe: 35079) using HISAT2, and gene expression was quantified using HTSeq. Differential gene analysis was performed using DESeq2.

2.4. Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing

Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) was conducted on the fourth leaves of two-month-old

Betula pendula L72 and its circular-leaf mutant Y72 on July 2, 2022 (

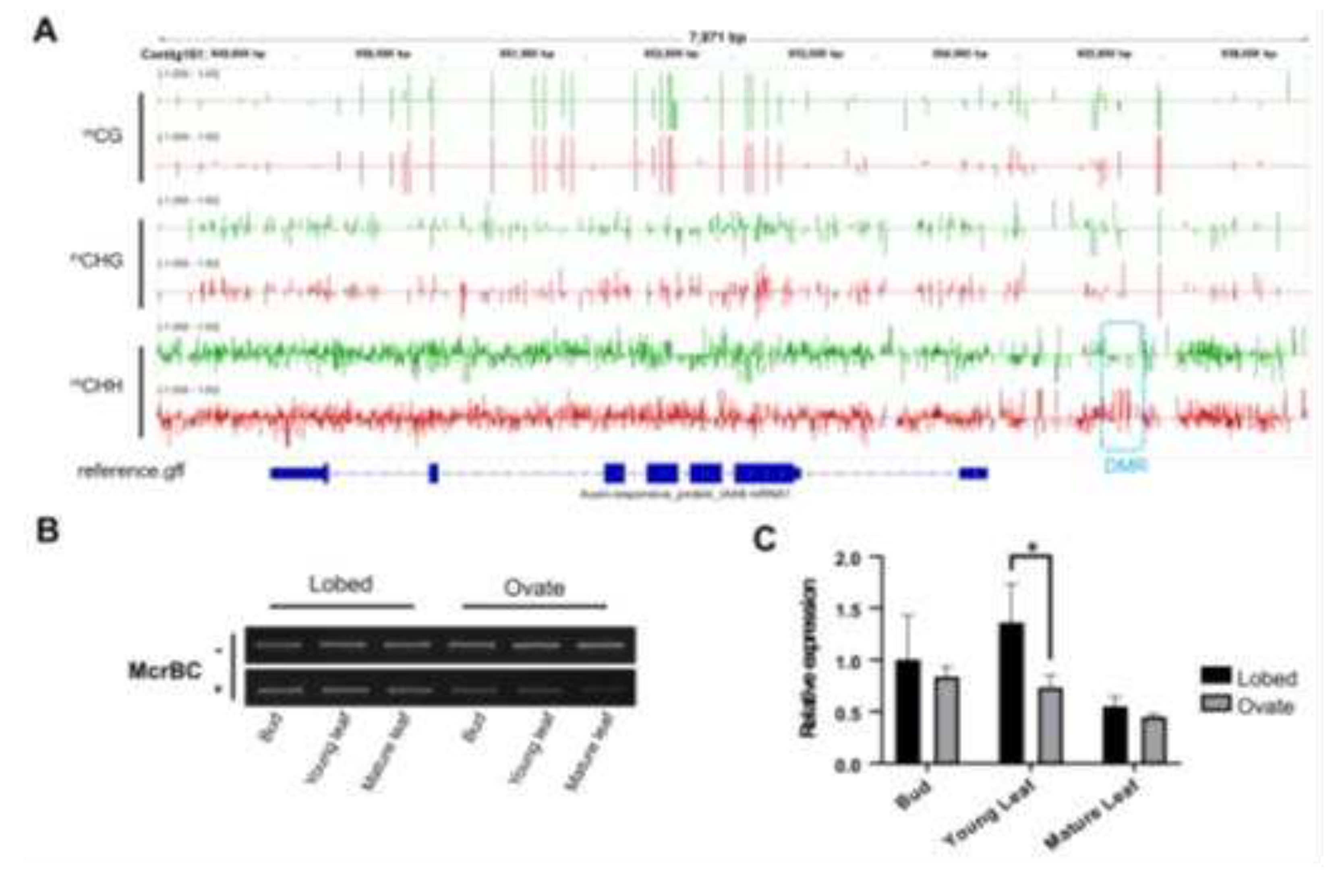

Figure 1, C, right). DNA extraction, bisulfite treatment, library construction, and sequencing were carried out by Shanghai Ling En Biotechnology Co., Ltd., with a sequencing depth of 10X on the Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform. The sequencing data underwent quality control, filtering, and adapter trimming using fastp. The clean data were aligned to a reference genome using bsmap for methylation analysis, which included the identification of differentially methylated regions (DMRs) with a differential rate >0.33 and Fisher’s exact test P-value <0.01 as the threshold. The results were visualized using the Integrative Genomics Viewer.

2.5. qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from both the round leaves of Betula pendula and the fourth dissected leaf using the Plant RNA Extraction Kit (BioTeke Co. China). Subsequently, the RNA’s integrity was evaluated by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel at 110V for 120 minutes. RNA purity was confirmed using a NanoPhotometer RP-Class spectrophotometer. The DNase-treated total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using a reverse transcription kit(ReverTra AceRqPCR RT Master Mix with gDNA Remover, Toyobo, Osaka, Japan), with primers consisting of a mixture of Oligo dT and random primers. The resulting cDNA was diluted tenfold and used as a template for qRT-PCR.

Primer design was facilitated by ApE and Primer 3 software (

http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/). These primers were used for relative quantitative PCR with the previously mentioned reverse-transcribed cDNA as the template. Each reaction contained 10 µL of Taq SYBR® Green qPCR Premix, 2 µL of cDNA template, 1 µL each of 10 µM gene-specific forward and reverse primers, and sterile water to reach a total volume of 20 µL. Real-time quantitative PCR was carried out using an ABI 7500 instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with the following program: 95°C for 30 seconds; 95°C for 15 seconds, followed by 60°C for 45 seconds for 45 cycles; 60°C for 1 minute; and a melt curve analysis from 95°C to 15 seconds. Each cDNA sample was analyzed in triplicate, and 18S rRNA and α-Tubulin were employed as internal reference genes. The relative expression level of the mRNA was calculated using the following formula: Relative mRNA expression level = 2^(-△△Ct).

2.6. McrBC-PCR

On May 8, 2023, leaf samples were collected and promptly preserved in liquid nitrogen. Total DNA extraction was carried out using a high-efficiency plant genomic DNA extraction kit (Trelief™ Hi-Pure Plant Genomic DNA Kit, Qiagen Biotech). The digested DNA was prepared by subjecting the DNA samples to McrBC digestion, utilizing the following reaction mixture for the enzyme-digested group: NEBuffer2 1 μL, 2 mg/mL rAlbumin 0.1 μL, 10 mM GTP 0.1 μL, 40 ng/μL DNA 5 μL, McrBC 0.2 μL, and ultrapure water 3.6 μL. In the control group, all reagents necessary for the enzyme digestion reaction except McrBC were added to the DNA, and glycerol was used to reach the final volume (NEBuffer2 1 μL, 2 mg/mL rAlbumin 0.1 μL, 10 mM GTP 0.1 μL, 40 ng/μL DNA 5 μL, glycerol 0.2 μL, ultrapure water 3.6 μL). All reactions were conducted at 37°C for 12 hours. The digested DNA from both the enzyme-digested group and the control group served as templates for PCR amplification, utilizing the GoldenStarT6 DNA Polymerase Mix Ver.2 (TSE102, Qiagen, Beijing). The amplification products were visualized through GelRed staining and assessed by electrophoresis on a 2.5% agarose gel (120V, 400mA, 30 minutes). DNA bands were observed under ultraviolet imaging.

4. Discussion

Silver birch,

Betula pendula, is a subspecies of European birch characterized by its serrated leaf margins. This trait is challenging to maintain during sexual reproduction and often spontaneously reverts to an ovate shape. It can also be induced to transform back into serrated leaves with the application of hormones or epigenetic mutagen 5-azacytidine (5AzC) [

7]. These observations strongly suggest that the serrated leaf trait is under the control of epigenetic mechanisms. In our investigation of the round-leaf mutant, we identified 1464 differential single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). These SNPs arise spontaneously during asexual reproduction, and yet, upon annotation, none of the 24 affected genes were found to be associated with leaf development. This further substantiates the notion that the serrated leaf trait is regulated by epigenetic factors rather than classical genetic traits.

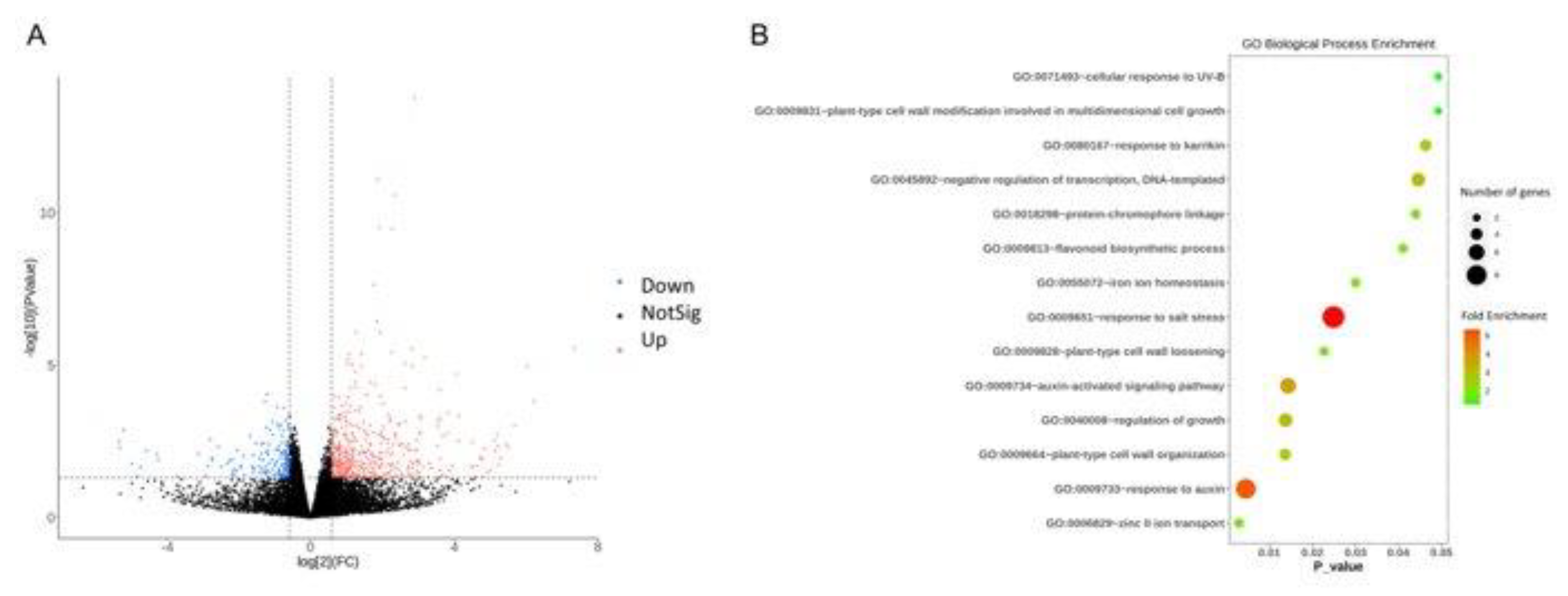

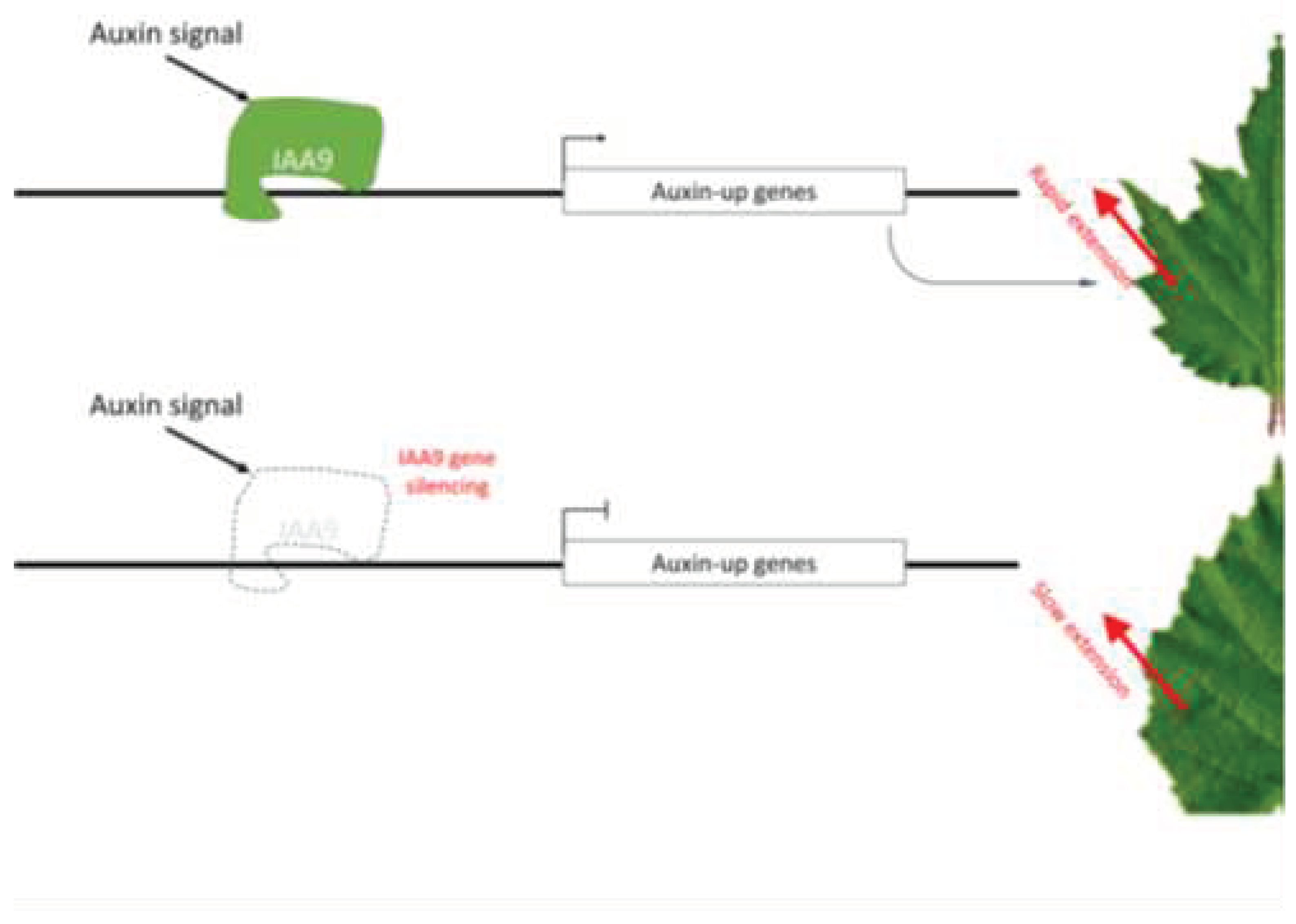

Auxin plays a crucial role in regulating the morphogenesis of plant leaves [24-26]. This regulatory function involves various processes, including synthesis, transport, signal transduction, and degradation. In our transcriptomic analysis of the round-leaf mutant Y72, we observed a downregulation of genes associated with the Gene Ontology (GO) terms GO:0009733 (response to auxin) and GO:0009734 (auxin-activated signaling). This enrichment of genes related to auxin signaling and activation pathways suggests that in this mutant, there is an impediment in the gene expression responsible for auxin signal transduction and activation. While the concentration of auxin in different regions of silver birch leaves has been considered an important indicator[

27], the response of target genes to these auxin signals has received relatively less attention. Our findings underscore the critical role of normal auxin signal transmission and gene activation in leaf development and morphogenesis.

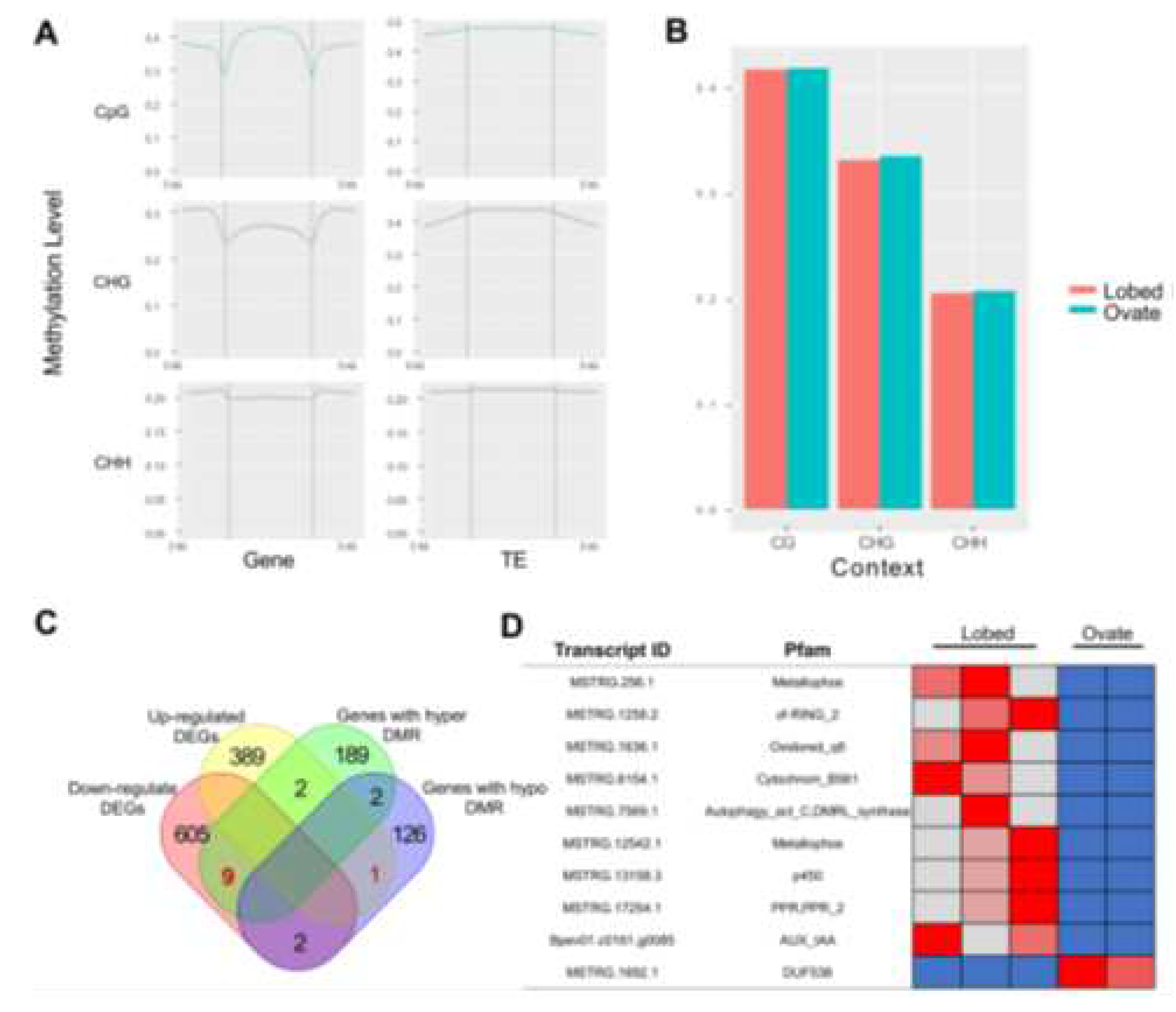

Previous studies have revealed that a decrease in methylation modification in the promoter region of the

BpPIN1 gene, a growth hormone transport protein, serves as a heritable epigenetic variation and a primary inducer of the fissured leaf trait in

Betula pendula in both sexual and asexual reproduction processes[

28]. However, in the circular leaf mutant Y72, we did not observe a significant restoration of methylation levels in

BpPIN1 to the high levels found in the fissured leaf, as depicted in

Figure 3, C to D. In comparison to fissured leaves, the global methylation levels across the genome of the circular leaf mutant showed no substantial changes in both genes and transposon elements, as shown in

Figure 3, A to B. This suggests that the epigenetic maintenance function of this mutant remains unaltered, and its variation arises from random mutations in individual gene epigenetics. Through a combined analysis of differential methylation sites and differentially expressed genes, we identified a growth hormone signal transporter gene,

BpIAA9. In birch, the transcription levels of AUX/IAA family transcription factors, such as

IAA9, are influenced by various factors, including environmental conditions and endogenous growth hormone concentration[

20]. These factors act by regulating downstream gene transcription in response to these signals.

IAA9 functions as a transcriptional activator in processes influenced by growth hormones, such as root development and seedling growth. In the circular leaf mutant, the increased methylation levels in the promoter region of

BpIAA9 led to decreased expression, impairing its ability to effectively transmit the growth hormone signal. In this situation of signal transmission inhibition, even if the methylation levels and expression of

BpPIN1 remain at their original levels, the accumulated growth hormone concentration is insufficient to induce the fissured leaf trait.

CHH-type methylation is a plant-specific epigenetic modification, generally maintained through the RdDM pathway. In this model, the interaction between the CLASSY (CLSY) protein and SAWADEE Homolog 1 (SHH1) recruits RNA Polymerase IV (Pol IV) to silent heterochromatin regions, using these heterochromatic DNA segments as templates to synthesize short non-coding RNAs. These RNAs undergo a series of transformations to generate 24-nt small RNAs and form complexes with certain AGO proteins. AGO-sRNAs proceed along the RNA scaffold synthesized by RNA Polymerase V (Pol V), recruiting a series of protein complexes to enlist DNA methyltransferase 2 (DRM2) for catalyzing DNA methylation. Due to the positive feedback loop between CHH-type cytosine methylation and 24-nt small RNAs, once methylation is established, it can be heritably transmitted in both asexual and sexual reproductive processes[

29].In this study, a highly methylated site within the

BpIAA9 promoter was discovered. This methylation belongs to the CHH-type, and McrBC-PCR analysis revealed that the level of methylation at this site is slightly lower in apical meristematic tissues but steadily increases in leaves as they grow and develop. This pattern could be attributed to the vigorous cell division in meristematic tissues, while this particular site lacks methylation in

Betula pendula.

This research, employing various omics sequencing approaches, identified an epigenetic mutation site within the

BpIAA9 promoter. The elevated methylation levels at this site led to a reduction in

BpIAA9 expression. This disruption hampers the normal role of auxin in growth regulation and weakens the impact of abnormal auxin concentration gradients in leaf growth and development, eventually eliminating the fissured leaf trait (

Figure 5). However, if mutations occur in other genes involved in auxin regulation, they could also induce the spontaneous reversion of

Betula pendula from fissured to circular leaves. Therefore, in the asexual reproduction of

Betula pen21dula, it is advisable to avoid factors that can induce changes in epigenetic modifications, including but not limited to temperature, salt, drought stress, and exposure to agents such as nicotinic acid and 5AzC. Further in-depth research on the genetic transformation and methylation variation mechanisms of

BpIAA9 is warranted in future studies.

Supplementary Table S1.

Annotation of Coding Variant Genes.

Supplementary Table S1.

Annotation of Coding Variant Genes.

| GeneID |

Description |

PFAMs |

| Bpev01.c0042.g0072 |

LRR receptor-like serine threonine-protein kinase At3g47570 |

LRRNT_2,LRR_1,LRR_8,Pkinase,Pkinase_Tyr |

| Bpev01.c2373.g0003 |

Ribonuclease H protein |

Exo_endo_phos_2,RVT_1,RVT_3,zf-RVT |

| Bpev01.c0051.g0044 |

zinc finger CCCH domain-containing protein |

CwfJ_C_1,CwfJ_C_2,zf-CCCH |

| Bpev01.c0056.g0001 |

Non-functional NADPH-dependent codeinone reductase 2-like |

Aldo_ket_red |

| Bpev01.c0106.g0013 |

Belongs to the cyclin family |

Cyclin_C,Cyclin_N |

| Bpev01.c0148.g0013 |

Homeobox protein knotted-1-like |

ELK,Homeobox_KN,KNOX1,KNOX2 |

| Bpev01.c0159.g0037 |

Lignin degradation and detoxification of lignin-derived products |

Cu-oxidase,Cu-oxidase_2,Cu-oxidase_3 |

| Bpev01.c0213.g0030 |

receptor |

PA,cEGF |

| Bpev01.c0261.g0047 |

Protein AUXIN SIGNALING F-BOX |

F-box-like,LRR_6 |

| Bpev01.c0418.g0001 |

Probably involved in the RNA silencing pathway and required for the generation of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) |

RdRP |

| Bpev01.c0547.g0018 |

wall-associated receptor kinase-like |

EGF_CA,GUB_WAK_bind,Pkinase,Pkinase_Tyr,WAK |

| Bpev01.c0665.g0008 |

Zinc phosphodiesterase ELAC protein |

Lactamase_B_2,Lactamase_B_4 |

| Bpev01.c0727.g0025 |

protein serine/threonine kinase activity |

Malectin_like,Pkinase_Tyr |

| Bpev01.c1122.g0007 |

Belongs to the universal ribosomal protein uL23 family |

Ribosomal_L23,Ribosomal_L23eN |

| Bpev01.c1136.g0001 |

ribonuclease H protein |

RVT_1,RVT_3,zf-RVT |

| Bpev01.c1152.g0017 |

Belongs to the glycosyl hydrolase 17 family |

Glyco_hydro_17 |

| Bpev01.c1155.g0004 |

Asparagine-specific endopeptidase involved in the processing of vacuolar seed protein precursors into the mature forms |

Peptidase_C13 |

| Bpev01.c1170.g0014 |

Protein of unknown function (DUF620) |

DUF620 |

| Bpev01.c1242.g0006 |

Pentatricopeptide repeat-containing protein |

PPR,PPR_2 |

| Bpev01.c1533.g0002 |

ribonuclease H protein |

RVT_1,RVT_3,zf-RVT |

| Bpev01.c1748.g0004 |

rRNA processing/ribosome biogenesis |

RIX1 |

| Bpev01.c2125.g0002 |

G-type lectin S-receptor-like serine threonine-protein kinase |

B_lectin,DUF3403,GUB_WAK_bind,PAN_2,Pkinase_Tyr,S_locus_glycop |

| Bpev01.c1039.g0006 |

Unknown |

Unknown |

| Bpev01.c0575.g0017 |

Unknown |

Unknown |

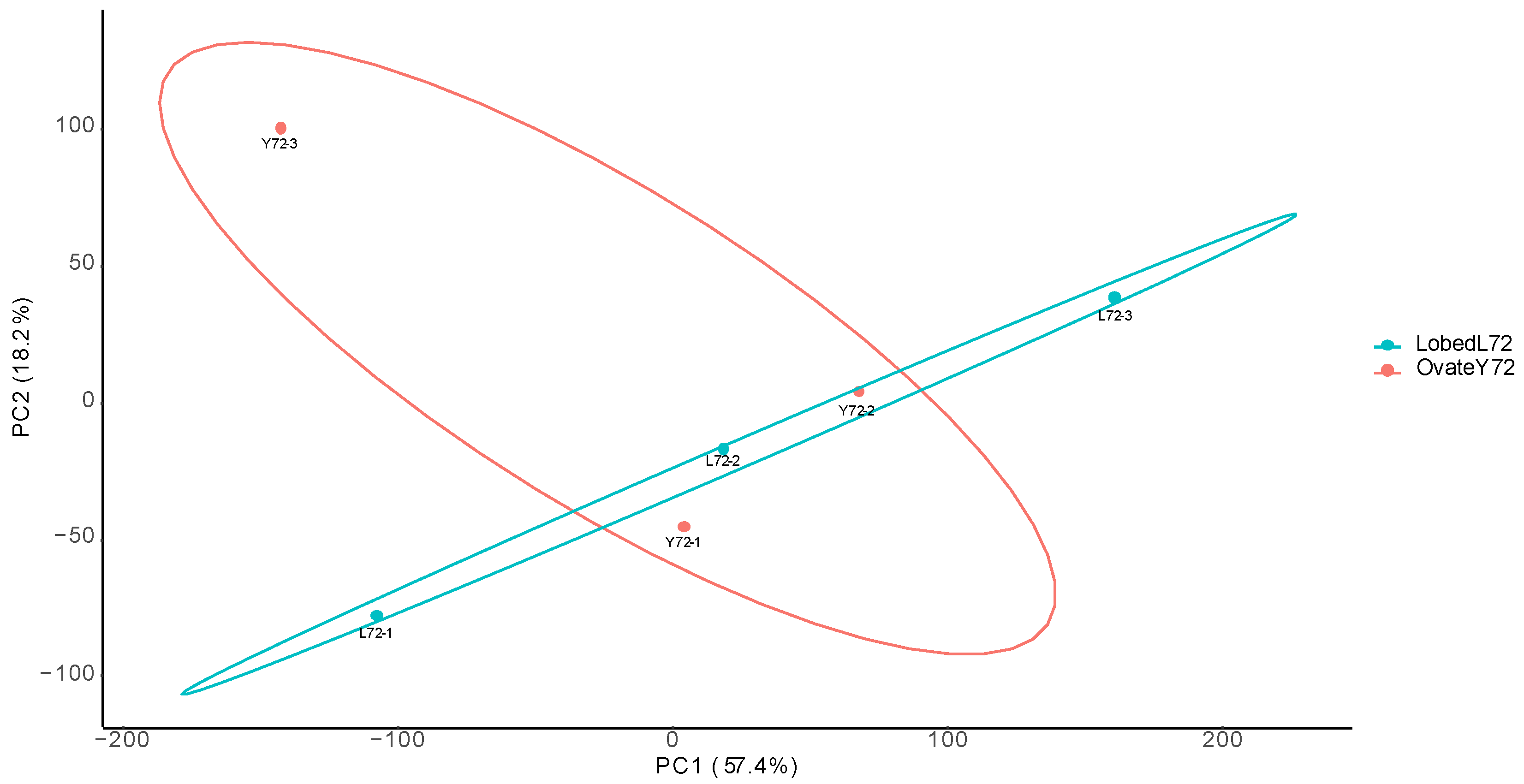

Supplementary Figure S1.

The principal component analysis results for biological replicates of transcriptome sequencing.

Supplementary Figure S1.

The principal component analysis results for biological replicates of transcriptome sequencing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z. and C.G.; methodology, H.L.; software, X.Z. and C.G.; validation, X.Z. and C.G.; formal analysis, C.G.; investigation, X.Z. and C.G.; resources, X.Z., C.G. and H.L.; data curation, C.G.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z. and C.G.; writing—review and editing, X.Z. and H.L.; visualization, X.Z.; supervision, H.L., G.L. and J.J.; project administration, H.L.; funding acquisition, H.L., G.L. and J.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.