Submitted:

14 November 2023

Posted:

14 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of mulberry fruit juice

2.3. Synthesis of M-AgNPs

2.4. Optimization of reaction parameters

2.5. Characterization of M-AgNPs

2.6. Evaluation of antioxidant activity

2.7. Evaluation of antibacterial activity

2.8. Statistical analysis

3. Results and Discussion

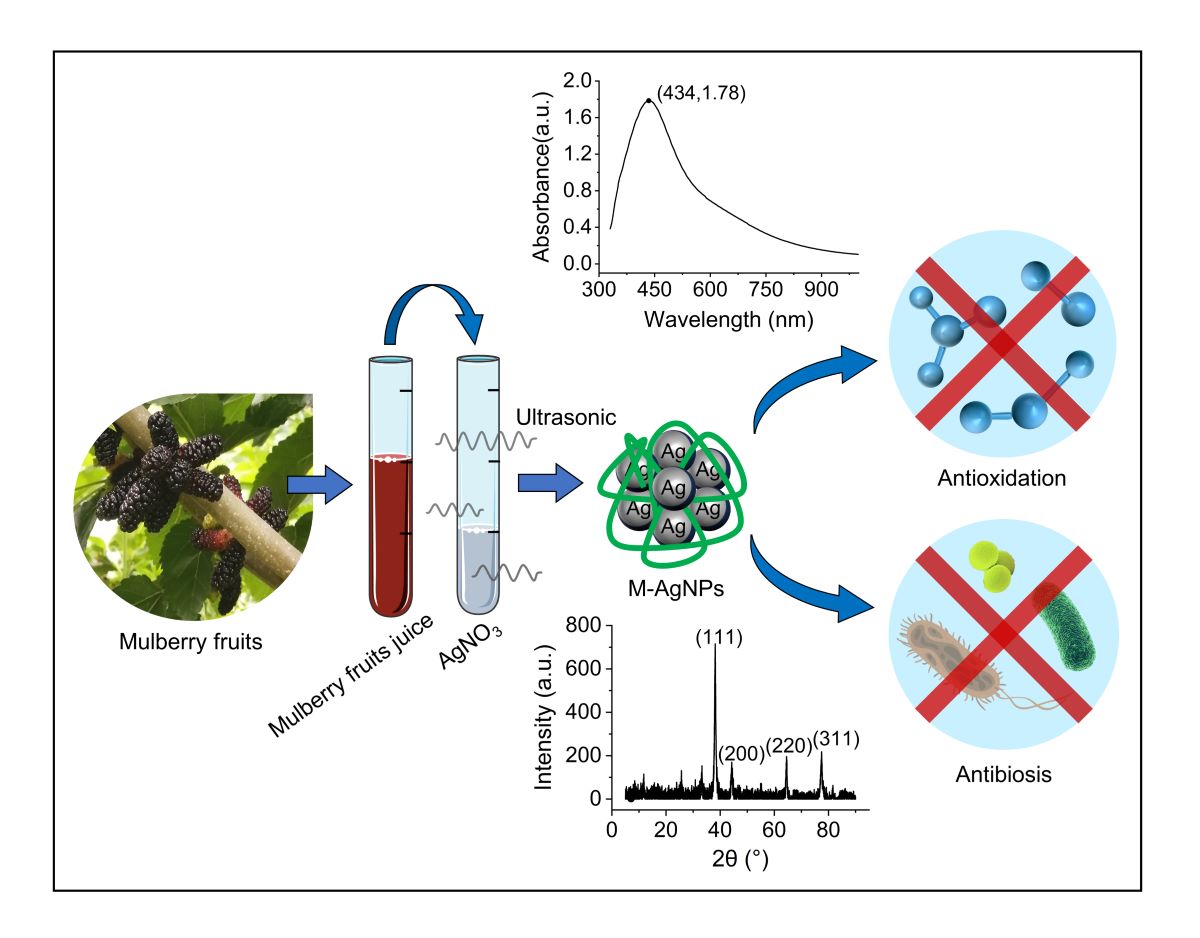

3.1. Synthesis of M-AgNPs and optimization of reaction parameters

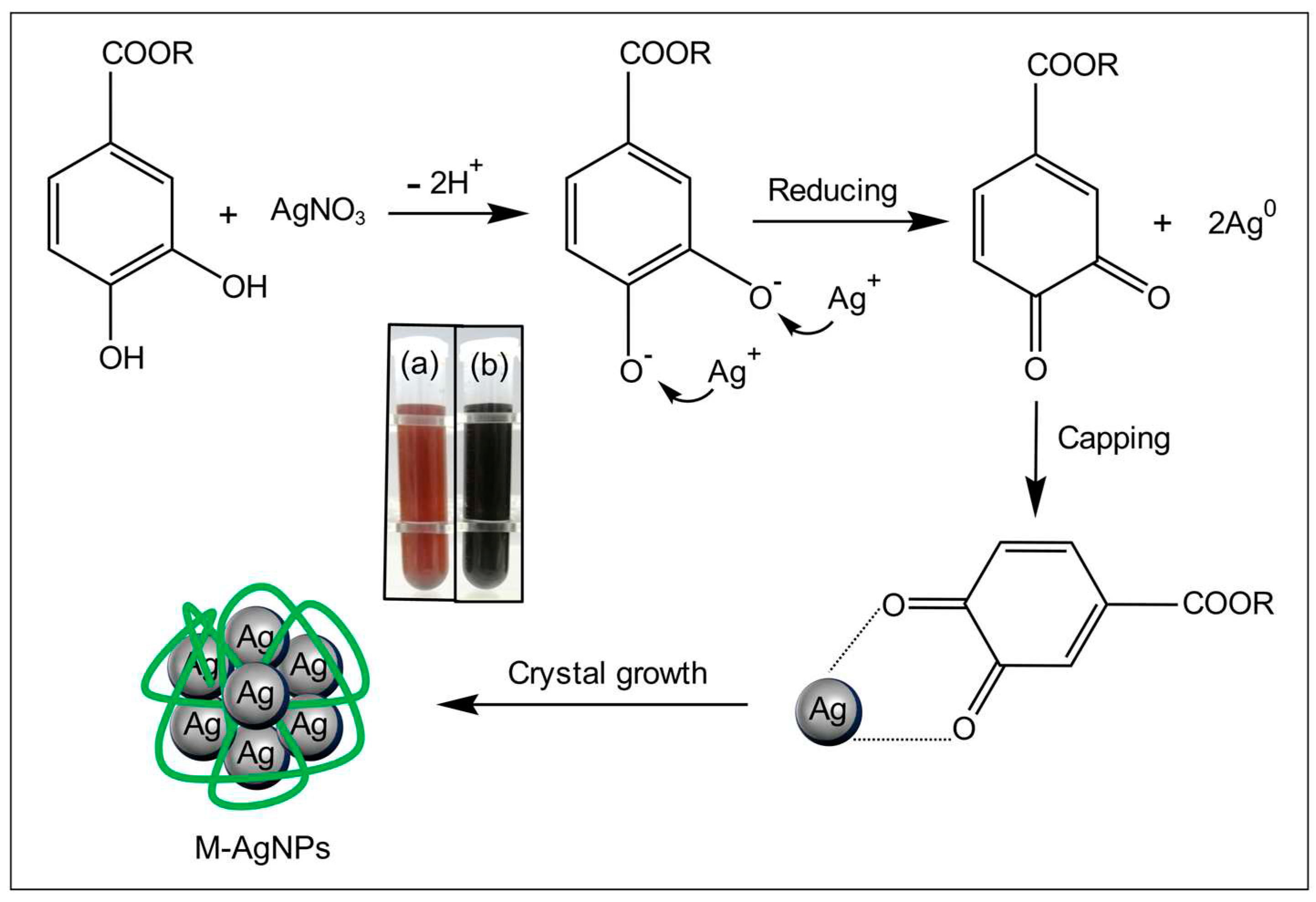

3.1.1. The synthesis of silver nanoparticles

3.1.2. Reaction time

3.1.3. Reaction temperature

3.1.4. pH

3.1.5. Concentration of AgNO3

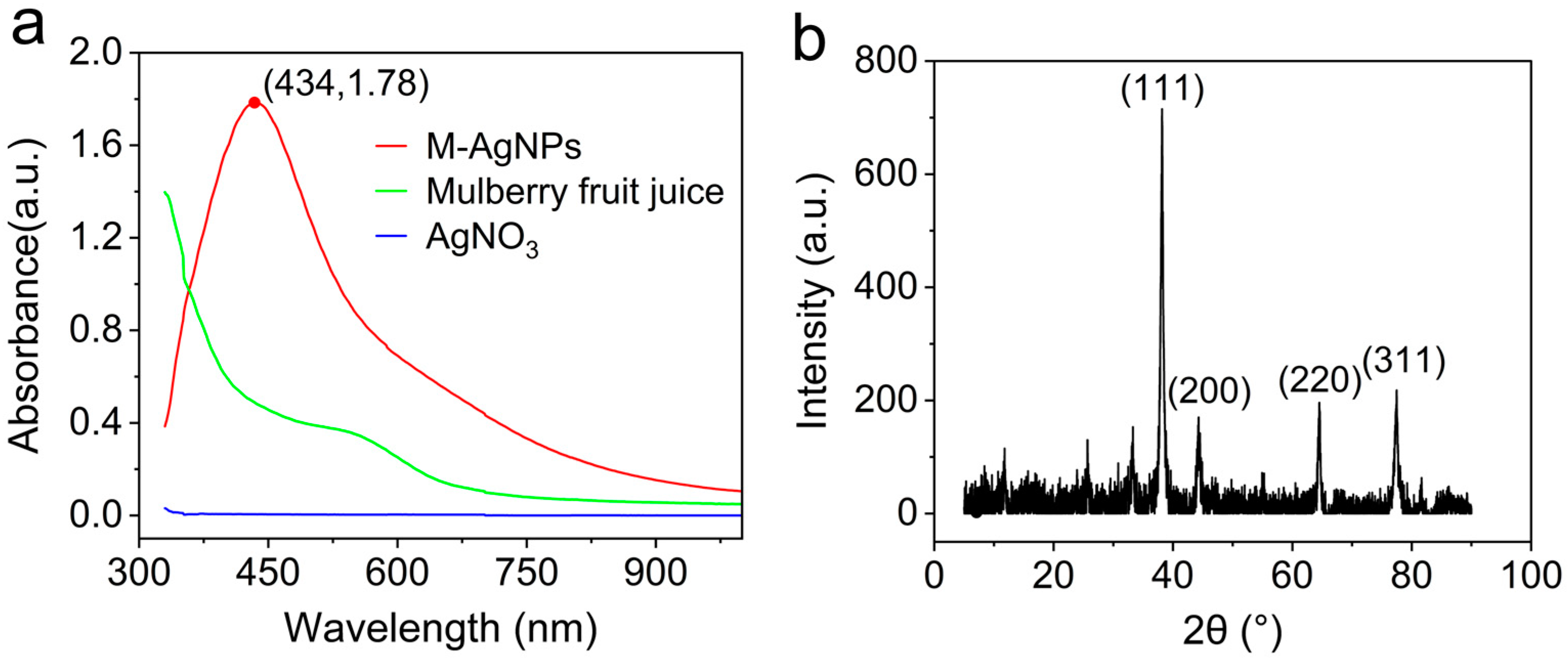

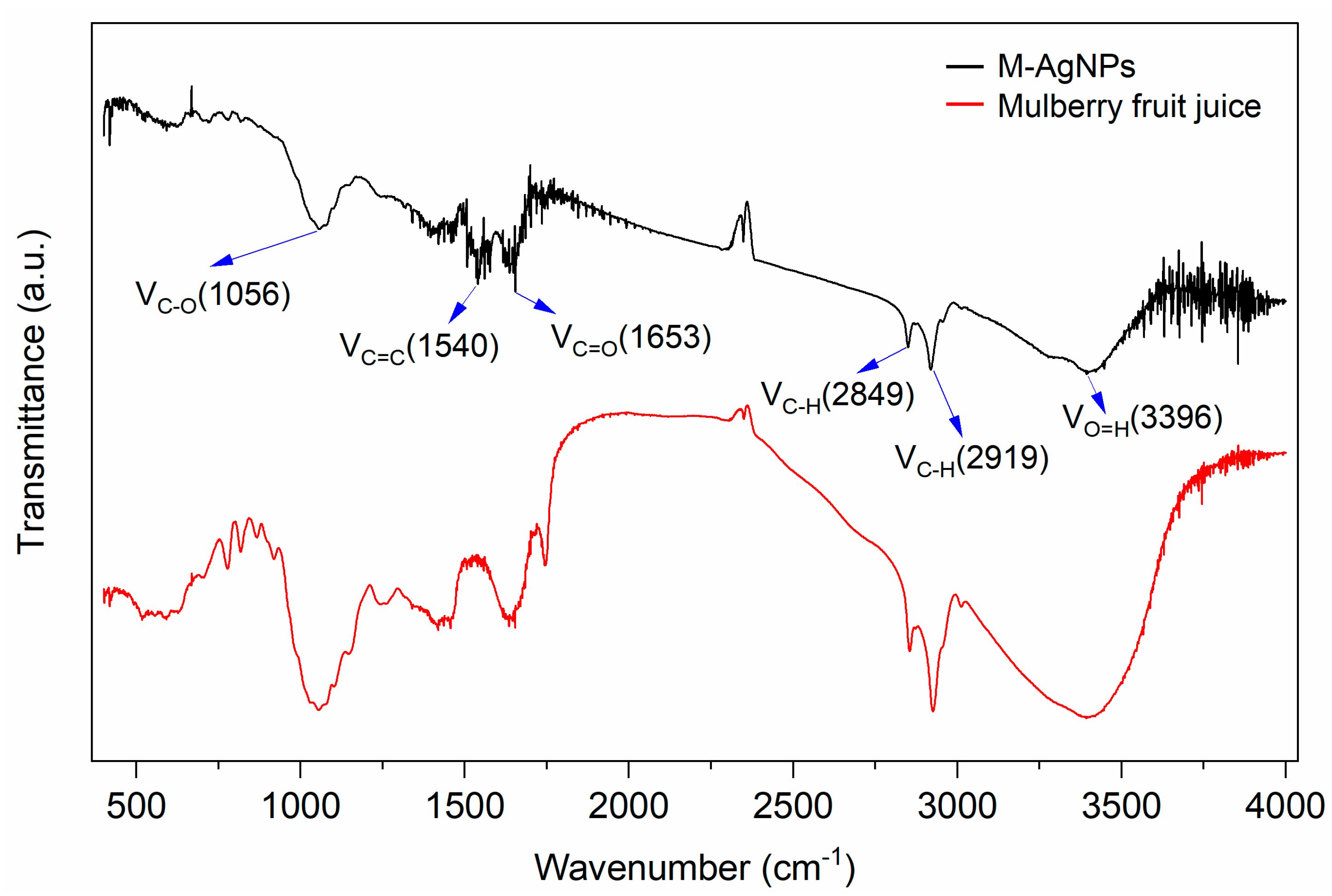

3.2. Characterization of M-AgNPs

3.2.1. UV-Vis absorption spectrum

3.2.2. XRD absorption spectrum

3.2.3. FT-IR absorption spectrum

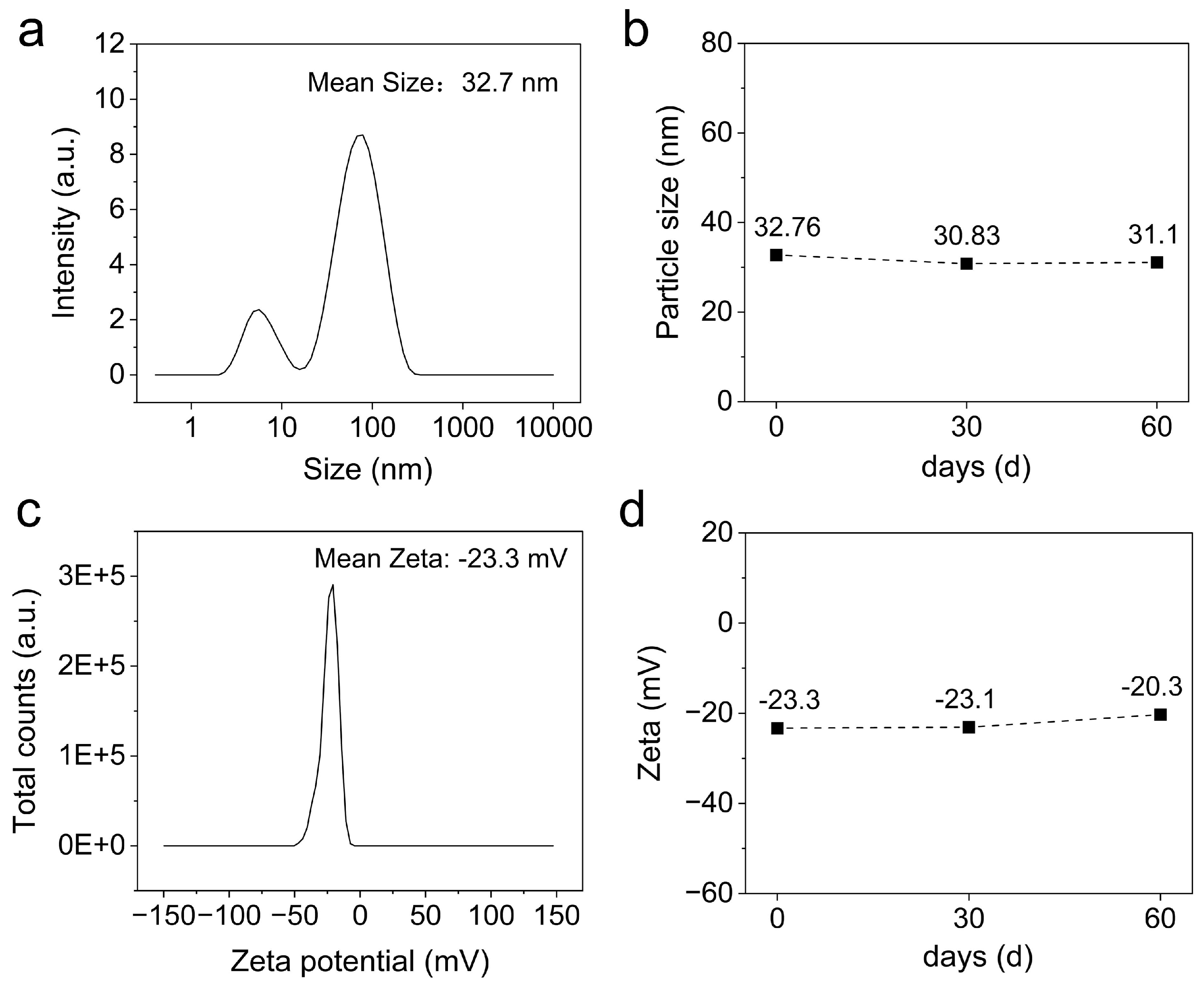

3.2.4. DLS analysis

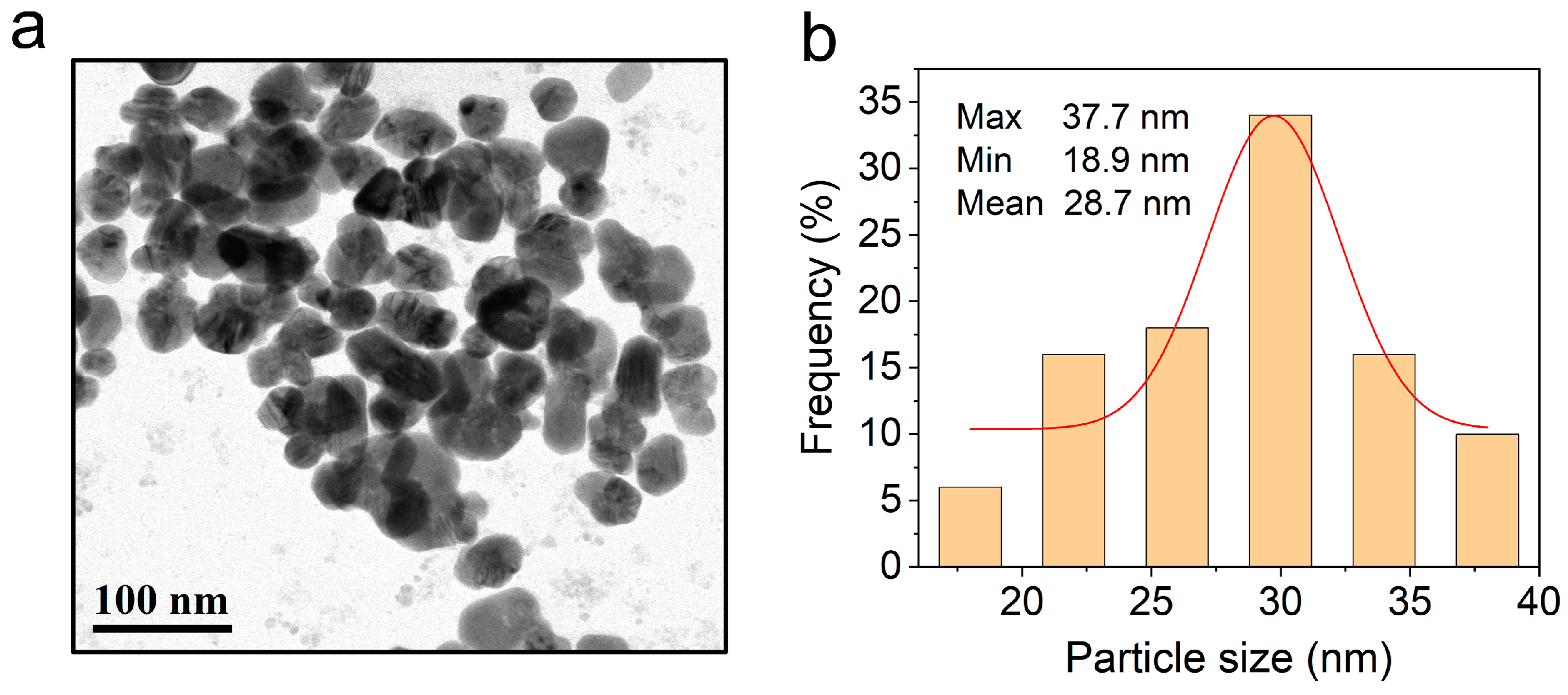

3.2.5. TEM observation

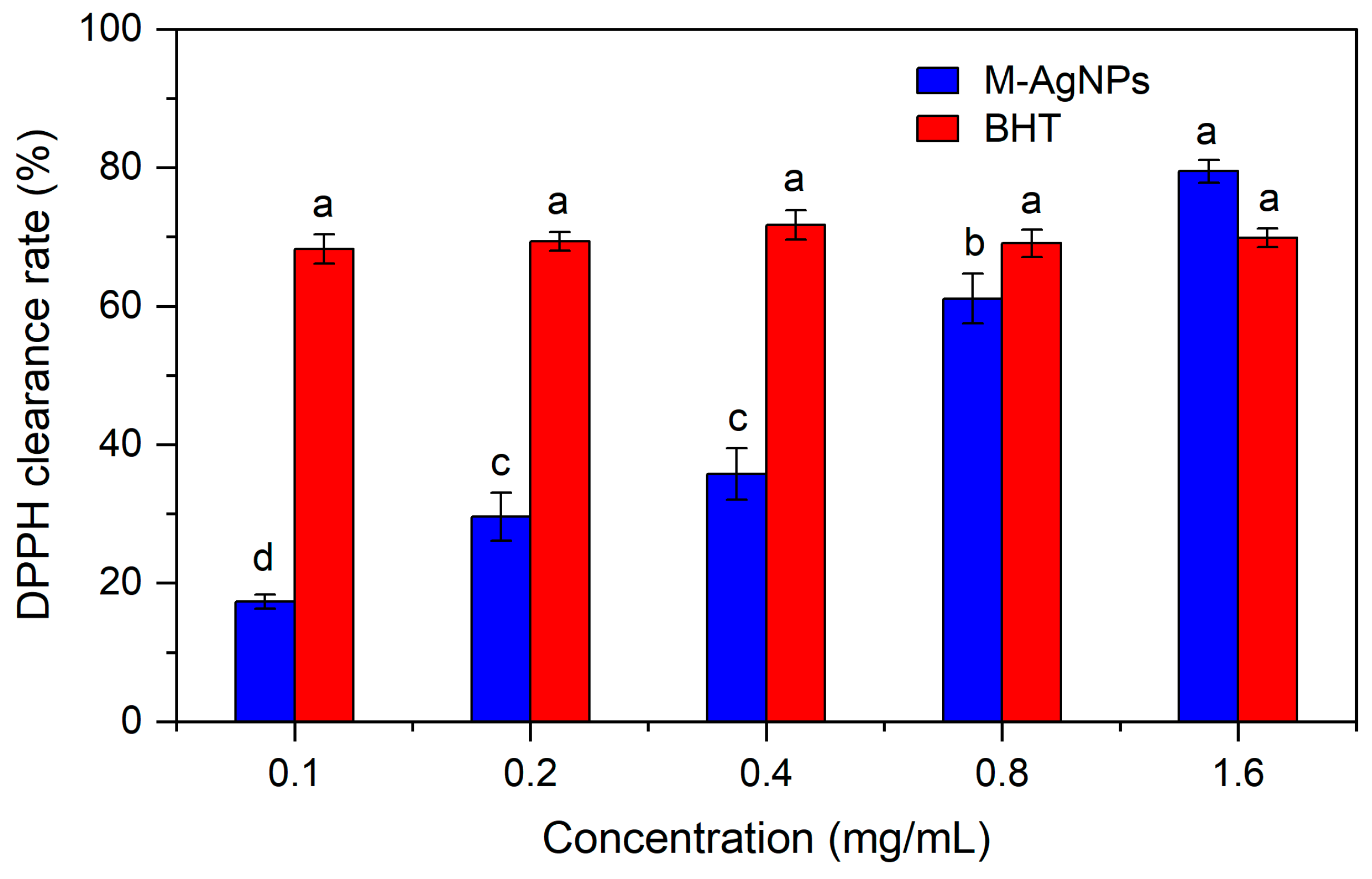

3.3. Antioxidant activity of M-AgNPs

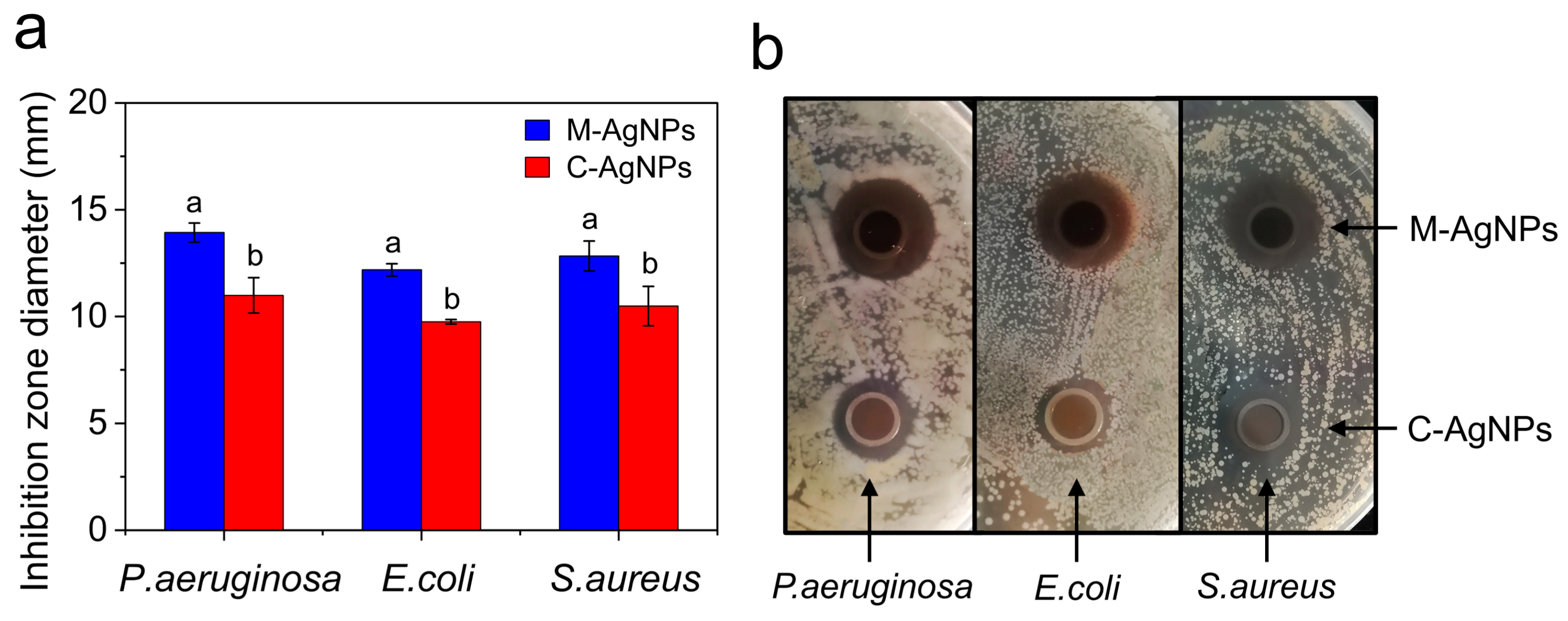

3.4. Antibacterial activity of M-AgNPs

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parashar, S.; Sharma, M.K.; Garg, C.; Garg, M. Green synthesized silver nanoparticles as silver lining in antimicrobial resistance: A review. Curr. Drug Delivery 2022, 19, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, M.A.; Ashrafudoulla, M.; Rahman, M.M.; Balusamy, S.R.; Akter, S. Green synthesis and potential antibacterial applications of bioactive silver nanoparticles: A review. Polymers 2022, 14, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khane, Y.; Benouis, K.; Albukhaty, S.; Sulaiman, G.M.; Abomughaid, M.M.; Al Ali, A.; Aouf, D.; Fenniche, F.; Khane, S.; Chaibi, W. , et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous citrus limon zest extract: Characterization and evaluation of their antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElNaggar, N.E.; Hussein, M.H.; ElSawah, A.A. Bio-fabrication of silver nanoparticles by phycocyanin, characterization, in vitro anticancer activity against breast cancer cell line and in vivo cytotxicity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Velmurugan, P.; Anbalagan, K.; Manosathyadevan, M.; Lee, K.; Cho, M.; Lee, S.; Park, J.; Oh, S.; Bang, K.; Oh, B. Green synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles using zingiber officinale root extract and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles against food pathogens. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 37, 1935–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Hu, C.; Shao, L. The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: Present situation and prospects for the future. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 1227–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.; Bulut, O.; Some, S.; Mandal, A.K.; Yilmaz, M.D.; Roy, A. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: Biomolecule-nanoparticle organizations targeting antimicrobial activity. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 2673–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, U.T.; Rao, G.V.S.N.; Mantravadi, K.M.; Oztekin, Y. Strategies to synthesize various nanostructures of silver and their applications – a review. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 19739–19753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.D.; Lai, J.Y. Synthesis, bioactive properties, and biomedical applications of intrinsically therapeutic nanoparticles for disease treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 435, 134970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, M.; Sadaf, I.; Rafique, M.S.; Tahir, M.B. A review on green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their applications. Artif. Cells, Nanomed., Biotechnol. 2016, 45, 1272–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, T.; Misni, N.; Ithnin, N.R.; Daskum, A.M.; Unyah, N.Z. A review on plants and microorganisms mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles, role of plants metabolites and applications. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, B.; Shireen, F.; Rauf, A.; Shariati, M.A.; Bashir, S.; Patel, S.; Khan, A.; Rebezov, M.; Khan, M.U.; Mubarak, M.S. , et al. Phyto-fabrication, purification, characterisation, optimisation, and biological competence of nano-silver. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habeeb Rahuman, H.B.; Dhandapani, R.; Narayanan, S.; Palanivel, V.; Paramasivam, R.; Subbarayalu, R.; Thangavelu, S.; Muthupandian, S. Medicinal plants mediated the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their biomedical applications. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 16, 115–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Shuang, F.; Fu, Q.; Ju, Y.; Zong, C.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, D.; Yao, X.; Cao, F. Evaluation of the chemical composition and antioxidant activity of mulberry (morus alba l.) fruits from different varieties in china. Molecules 2022, 27, 2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, J.; Gao, Y.; Xue, J.; Yang, Y.; Yin, J.; Wu, T.; Zhang, M. Phytochemicals, pharmacological effects and molecular mechanisms of mulberry. Foods 2022, 11, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Yang, J.; Ma, L.; Wen, D.; Chen, F.; Li, J. Identification of polyphenols in mulberry (genus morus) cultivars by liquid chromatography with time-of-flight mass spectrometer. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2017, 63, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunović, S.M.; Mašković, P.; Milinković, M. Determination of primary metabolites, vitamins and minerals in black mulberry (morus nigra) berries depending on altitude. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2020, 62, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjya, D.; Sadat, A.; Dam, P.; Buccini, D.F.; Mondal, R.; Biswas, T.; Biswas, K.; Sarkar, H.; Bhuimali, A.; Kati, A. , et al. Current concepts and prospects of mulberry fruits for nutraceutical and medicinal benefits. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 40, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; You, L.; Abbasi, A.M.; Fu, X.; Liu, R.H. Optimization for ultrasound extraction of polysaccharides from mulberry fruits with antioxidant and hyperglycemic activity in vitro. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 130, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Wang, C.; Chang, Y.; Hung, T.; Lai, C.; Kuo, C.; Huang, H. Mulberry fruits extracts induce apoptosis and autophagy of liver cancer cell and prevent hepatocarcinogenesis in vivo. J. Food Drug Anal. 2020, 28, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Dai, M.; Nie, W.; Yang, X.; Zeng, X. Effects of the ethanol extract of black mulberry (morus nigra l.) fruit on experimental atherosclerosis in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 200, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Bao, T.; Chen, W. Comparison of the protective effect of black and white mulberry against ethyl carbamate-induced cytotoxicity and oxidative damage. Food Chem. 2018, 243, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, M.; Li, N.; Wang, B.; Fan, W.; Xia, A.; Li, J. Evaluation of nutrition, aroma components and antioxidant activity ofmulberry fruits from nine varieties. J. Fruit Sci 2022, 39, 221–232. [Google Scholar]

- Sicari, V.; Loizzo, M.R.; Branca, V.; Pellicanò, T.M. Bioactive and antioxidant activity from citrus bergamia risso (bergamot) juice collected in different areas of reggio calabria province, italy. Int. J. Food Prop. 2016, 19, 1962–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagajjanani Rao, K.; Paria, S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from aqueous aegle marmelos leaf extract. Mater. Res. Bull. 2013, 48, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbhuiya, R.I.; Singha, P.; Asaithambi, N.; Singh, S.K. Ultrasound-assisted rapid biological synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using pomelo peel waste. Food Chem. 2022, 385, 132602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gevorgyan, S.; Schubert, R.; Yeranosyan, M.; Gabrielyan, L.; Trchounian, A.; Lorenzen, K.; Trchounian, K. Antibacterial activity of royal jelly-mediated green synthesized silver nanoparticles. AMB Express 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ma, W.; Ali, I.; Zhao, H.; Wang, D.; Qiu, J. Green and facile synthesis and antioxidant and antibacterial evaluation of dietary myricetin-mediated silver nanoparticles. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 32632–32640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muniyappan, N.; Nagarajan, N.S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with dalbergia spinosa leaves and their applications in biological and catalytic activities. Process Biochem. 2014, 49, 1054–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.F.; Cheng, F.; Zhang, X.L.; Wang, X.J.; Yang, X.Z.; Yuan, B. Rapid and green synthesis of monodisperse silver nanoparticles using mulberry leaf extract. Rare Metal Mat. Eng. 2018, 47, 1089–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Manjari Mishra, P.; Kumar Sahoo, S.; Kumar Naik, G.; Parida, K. Biomimetic synthesis, characterization and mechanism of formation of stable silver nanoparticles using averrhoa carambola l. Leaf extract. Mater. Lett. 2015, 160, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lade, B.D.; Shanware, A.S. Phytonanofabrication: Methodology and factors affecting biosynthesis of nanoparticles. Smart Nanosyst. Biomed., Optoelectron. Catal. 2020; 6. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, S.; Mehata, M.S. Medicinal plant leaf extract and pure flavonoid mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their enhanced antibacterial property. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nouri, A.; Tavakkoli Yaraki, M.; Lajevardi, A.; Rezaei, Z.; Ghorbanpour, M.; Tanzifi, M. Ultrasonic-assisted green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mentha aquatica leaf extract for enhanced antibacterial properties and catalytic activity. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 2020, 35, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Hao, L.; Yang, P. Mango peel extract mediated novel route for synthesis of silver nanoparticles and antibacterial application of silver nanoparticles. J. Shanxi Agr. Uni. 2013, 33, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Chandraker, S.K.; Lal, M.; Khanam, F.; Dhruve, P.; Singh, R.P.; Shukla, R. Therapeutic potential of biogenic and optimized silver nanoparticles using rubia cordifolia l. Leaf extract. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathiya, C.K.; Akilandeswari, S. Fabrication and characterization of silver nanoparticles using delonix elata leaf broth. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2014, 128, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zia, M.; Gul, S.; Akhtar, J.; Ul Haq, I.; Abbasi, B.H.; Hussain, A.; Naz, S.; Chaudhary, M.F. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from grape and tomato juices and evaluation of biological activities. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 11, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhakya, S.; Muthukrishnan, S.; Sukumaran, M.; Muthukumar, M. Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their antioxidant and antibacterial activity. Applied Nanoscience 2015, 6, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnamvand, M.; Huo, C.; Liu, J. Silver nanoparticles synthesized using allium ampeloprasum l. Leaf extract: Characterization and performance in catalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol and antioxidant activity. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1175, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.S.; Kim, H.; Kang, S.-S. In vitro anti-bacterial and anti-inflammatory activities of lactic acid bacteria-biotransformed mulberry (morus alba linnaeus) fruit extract against salmonella typhimurium. Food Control 2019, 106, 106758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakal, T.C.; Kumar, A.; Majumdar, R.S.; Yadav, V. Mechanistic basis of antimicrobial actions of silver nanoparticles. Front Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wigginton, N.S.; Titta, A.d.; Piccapietra, F.; Dobias, J.; Nesatyy, V.J.; Suter, M.J.F.; Bernier-Latmani, R. Binding of silver nanoparticles to bacterial proteins depends on surface modifications and inhibits enzymatic activity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 2163–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belluco, S.; Losasso, C.; Patuzzi, I.; Rigo, L.; Conficoni, D.; Gallocchio, F.; Cibin, V.; Catellani, P.; Segato, S.; Ricci, A. Silver as antibacterial toward listeria monocytogenes. Front Microbiol. 2016, 7, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavin, Y.N.; Asnis, J.; Häfeli, U.O.; Bach, H. Metal nanoparticles: Understanding the mechanisms behind antibacterial activity. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).