Submitted:

09 November 2023

Posted:

10 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

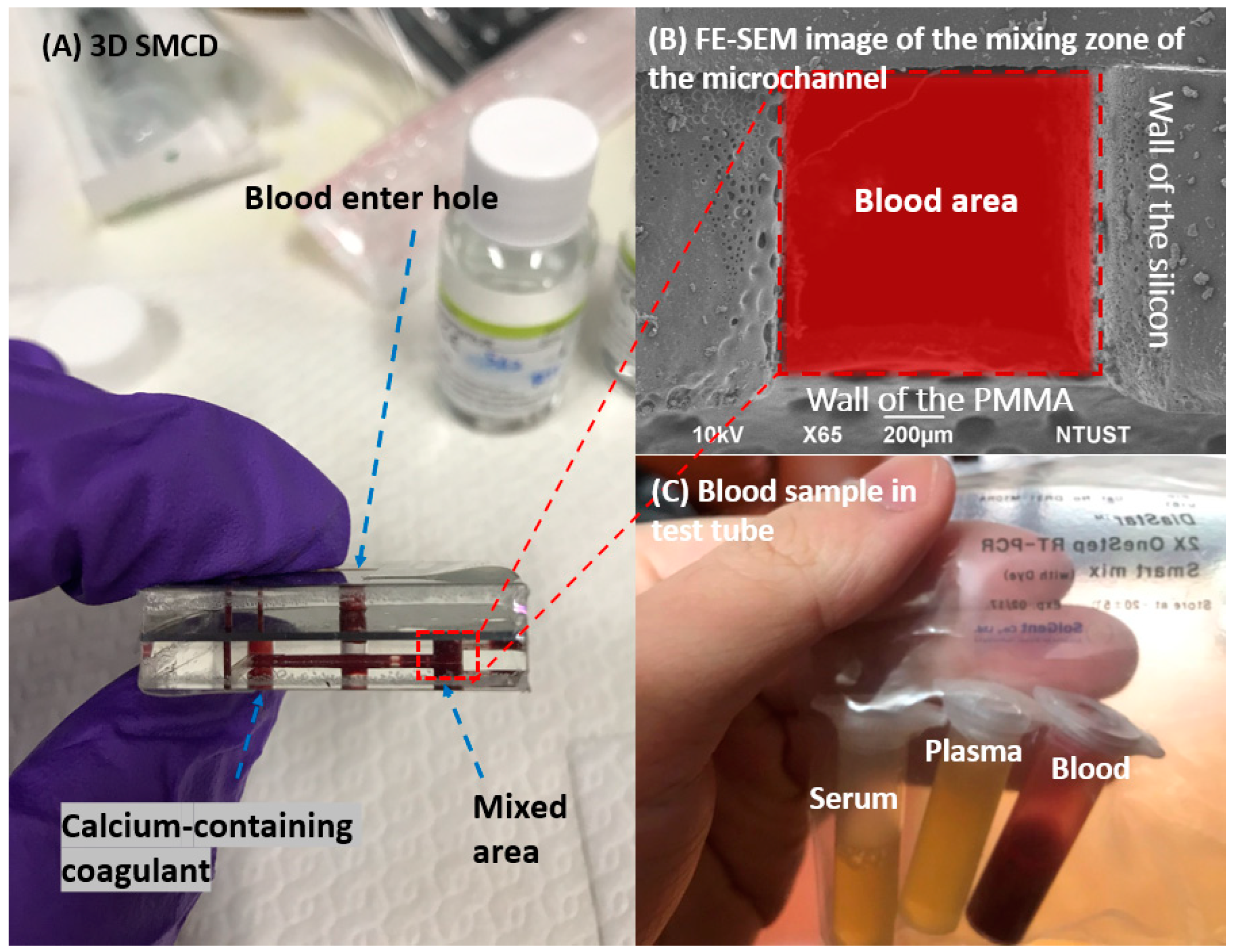

2. Sample Preparation for 3D SMCD

2.2. Blood Sample Preparation

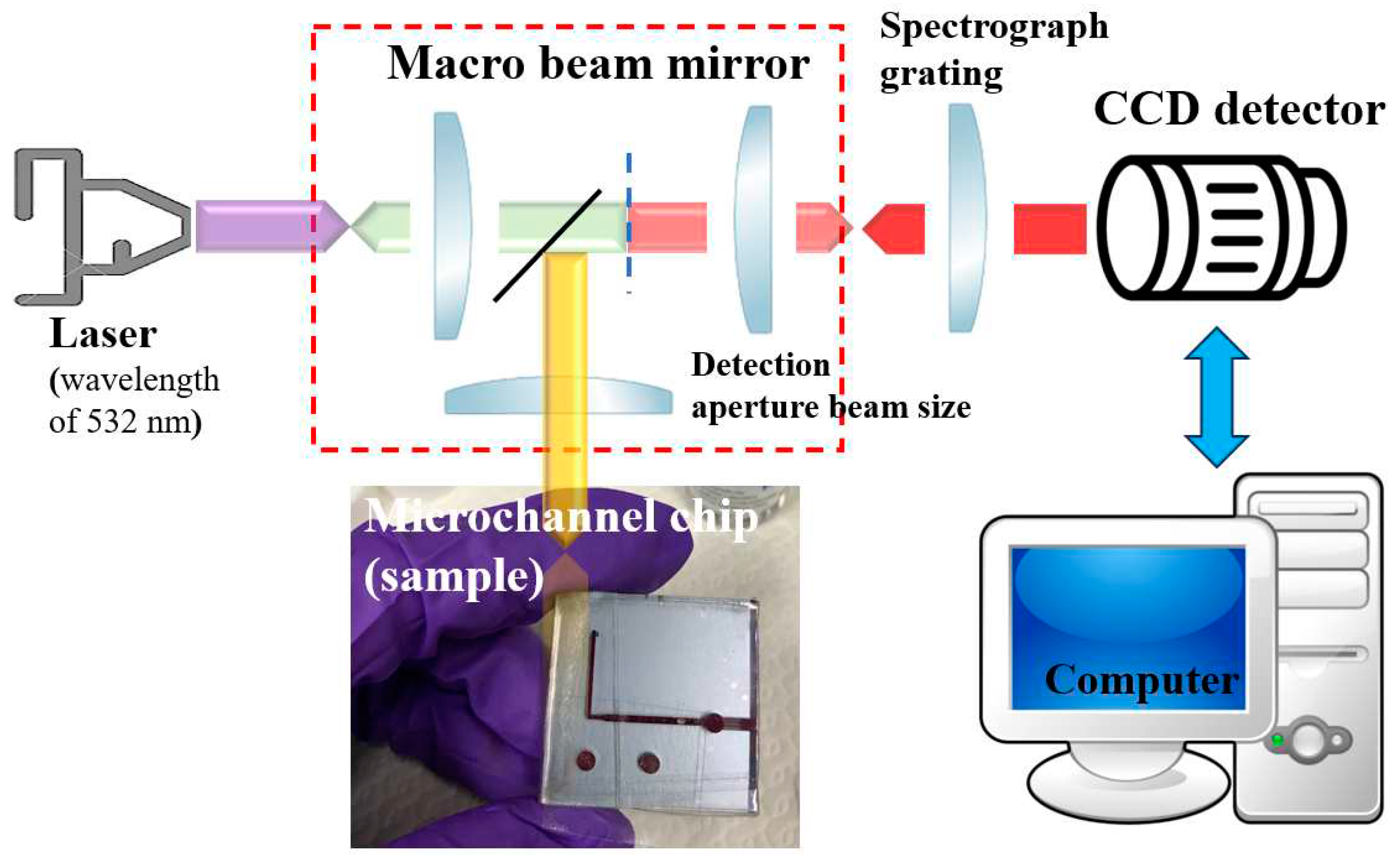

3. Raman Spectroscopy

4. Results and Discussion

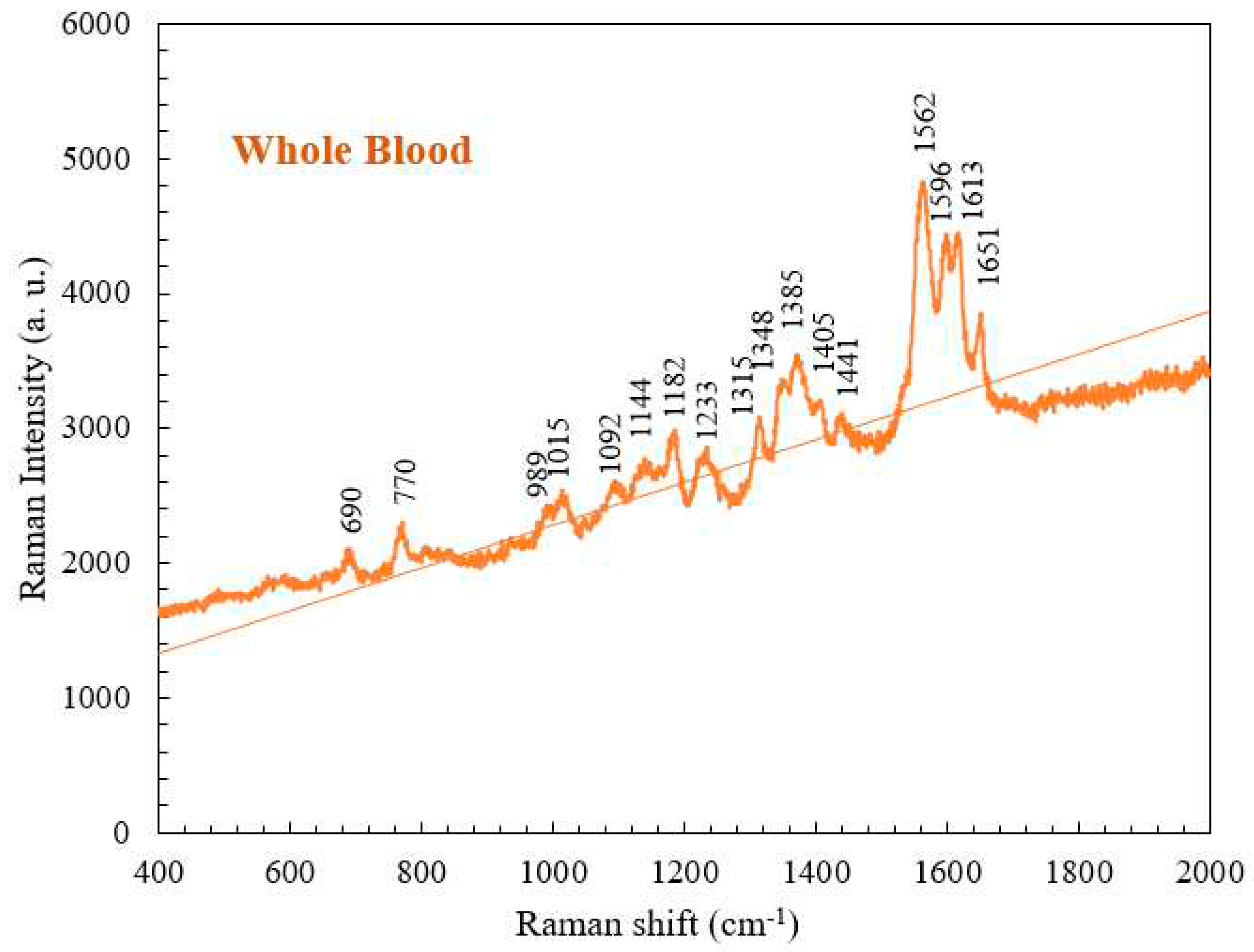

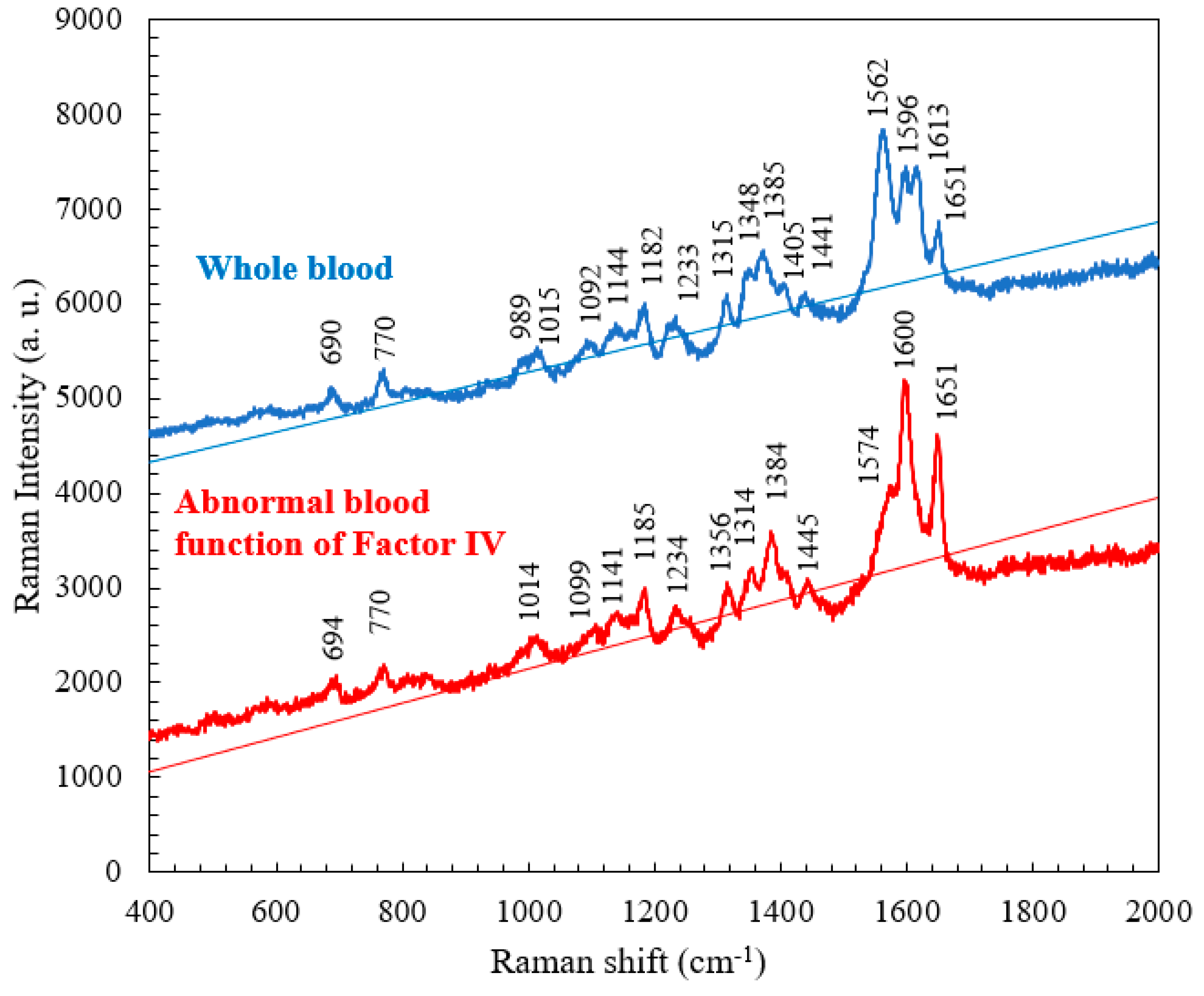

4.1. Raman Spectrum for Whole Blood

4.2. Comparison of the Raman Spectra of Whole Blood and Abnormal Blood Function of Factor IV

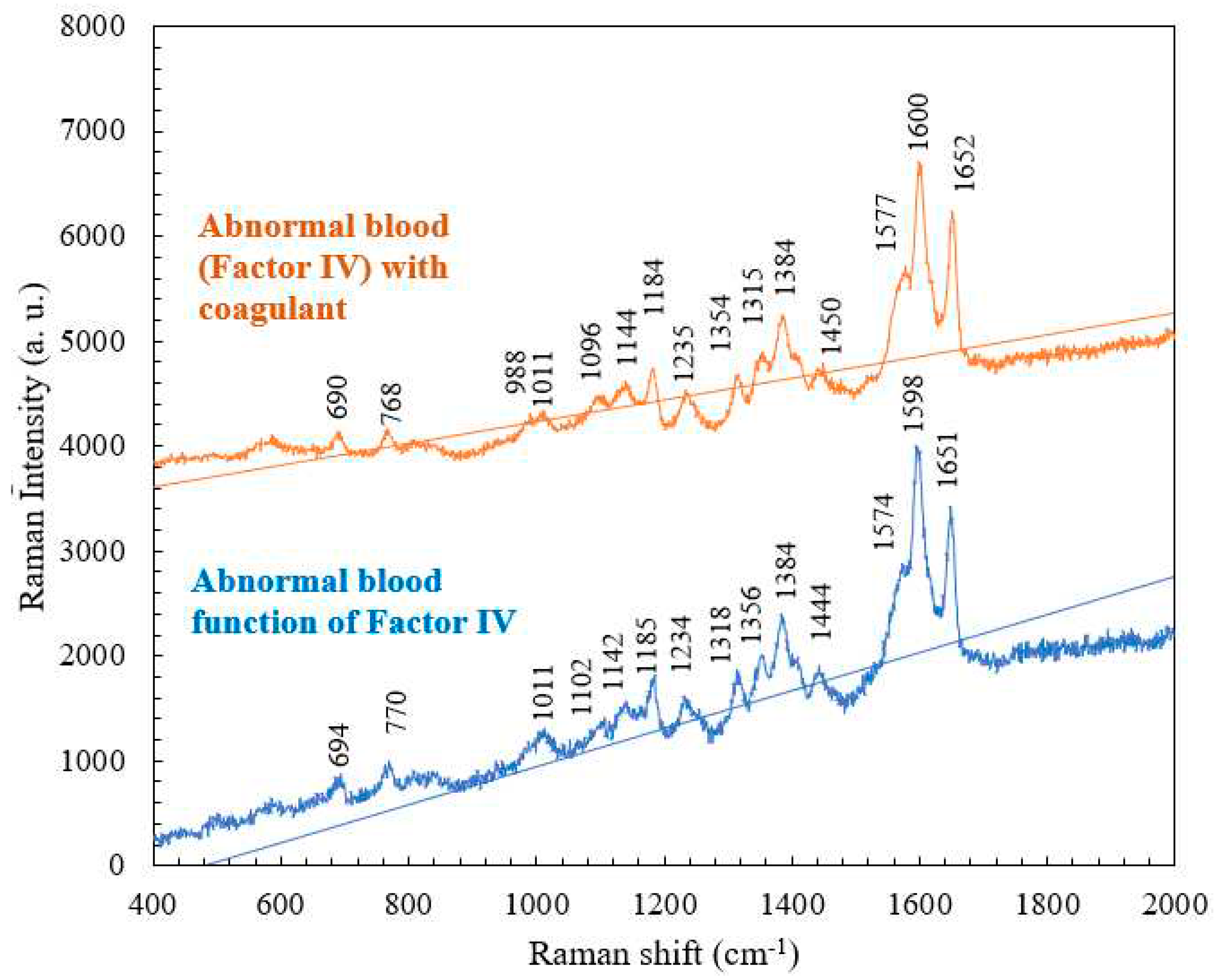

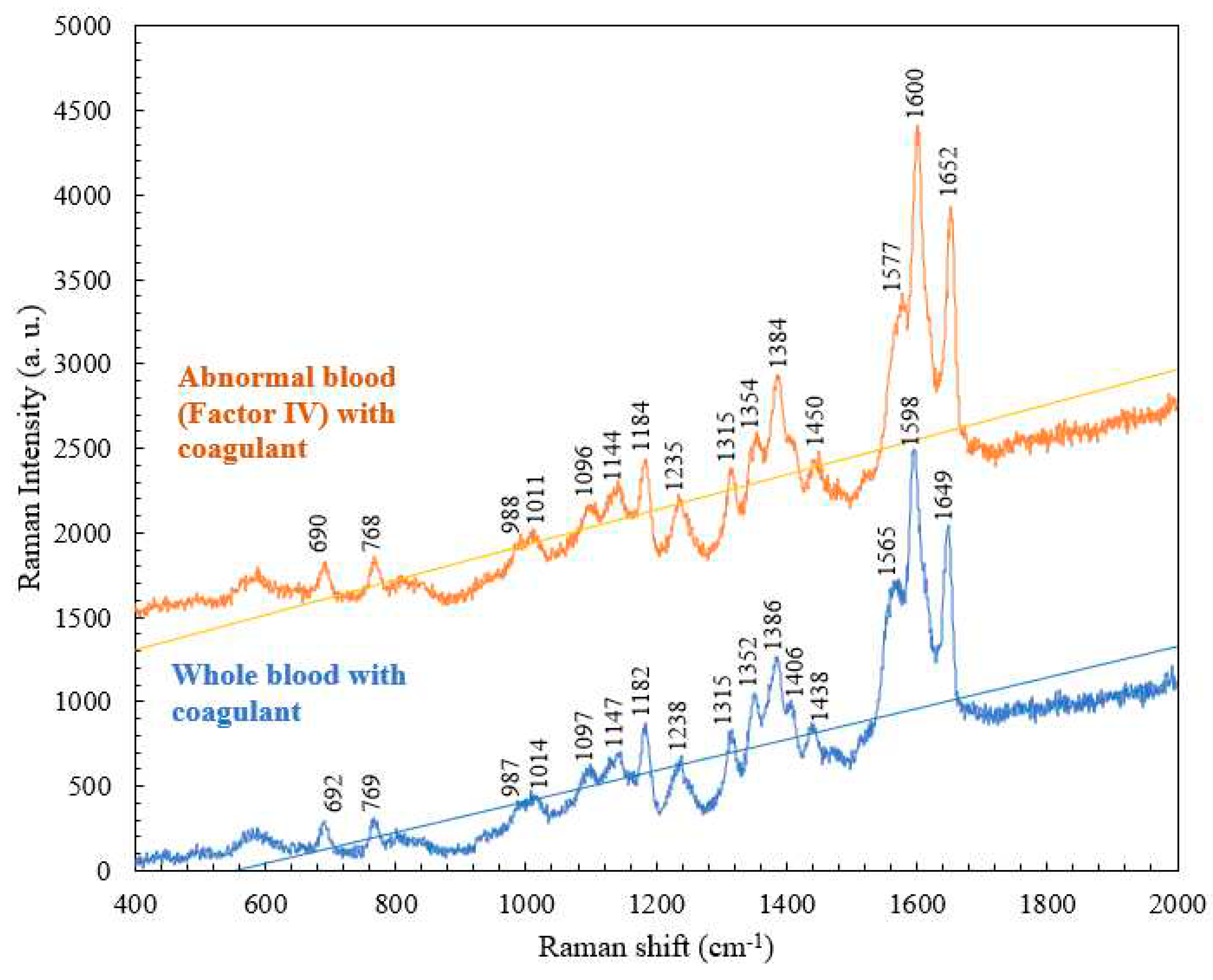

4.3. Comparison of the Raman Spectra of Abnormal Blood (Factor IV) with and without Coagulant

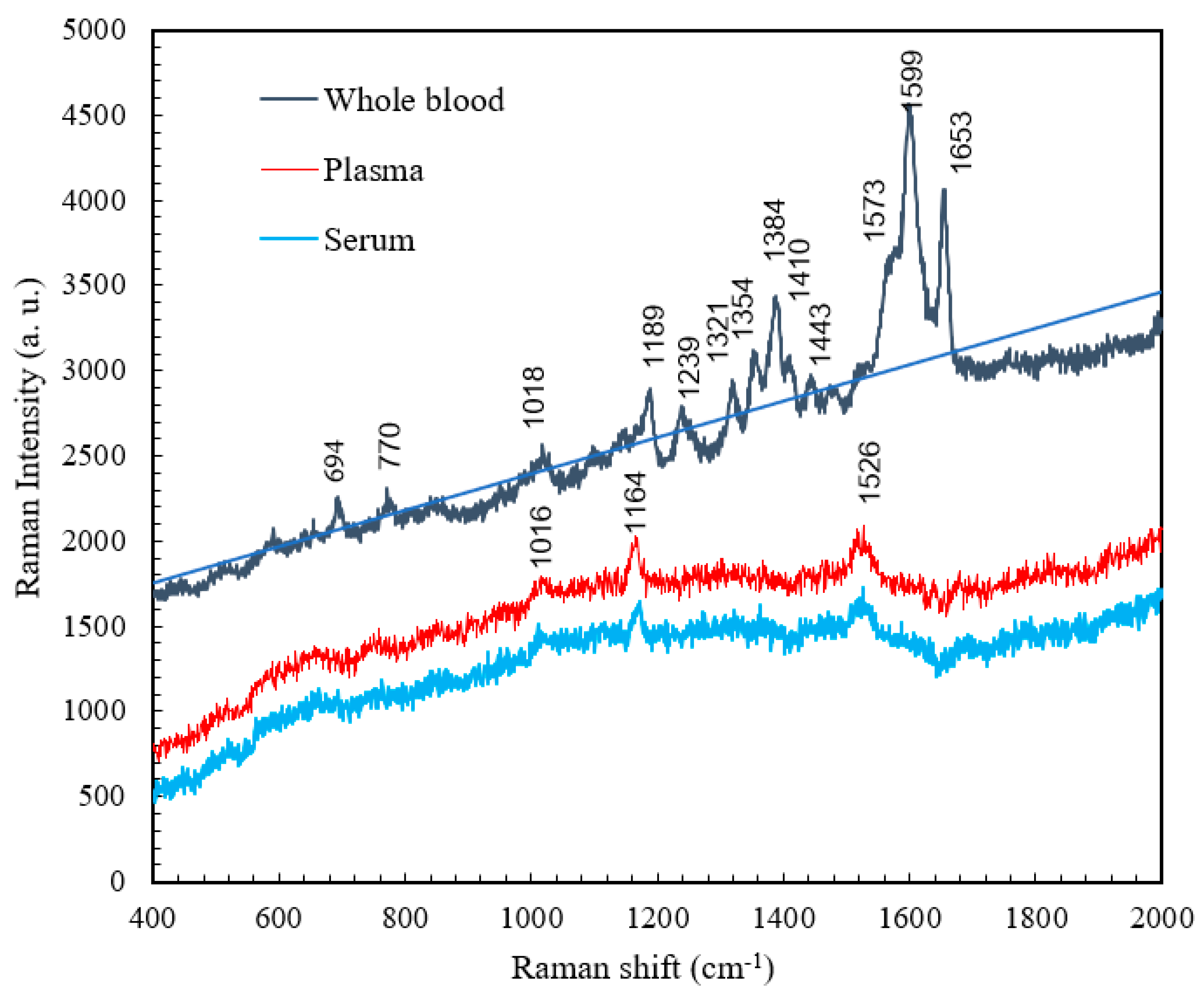

4.4. Comparison of the Raman Spectra of Whole Blood, Plasma, and Serum

| Raman shift (cm-1) | Vibrational blood mode | Component |

|---|---|---|

| 1016 | C-H bending | β-Carotene |

| 1164 | C-C stretching | β-Carotene |

| 1526 | C-C stretching | β-Carotene |

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Kong, K.; Kendall, C.; Stone, N.; Notinghera, I. Raman spectroscopy for medical diagnostics — From in-vitro biofluid assays to in-vivo cancer detection. Volume. 2015, 89, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pence, I.J.; Janse, A.M. Clinical instrumentation and applications of Raman spectroscopy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 1958–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Workman, J. Infrared and Raman spectroscopy in paper and pulp analysis. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2001, 36, 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sil, S.; Umapathy, S. Raman spectroscopy explores molecular structural signatures of hidden materials in depth: Universal Multiple Angle Raman Spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesh, K.V.S.S.; Bevi, A.R. Low-Cost Pulse Oximeter & Heart Rate Measurement for COVID Diagnosis. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2021; 1964, 62035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.W.; Yan, X.L.; Dong, R.X.; Ban, G.; Li, K. Analysis of serum from type II diabetes mellitus and diabetic complication using surface-enhanced Raman spectra (SERS). Appl. Phys. 2009, 94, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusciano, G.; Luca, A.C.D.; Pesce, G.; Sasso, A. Raman Tweezers as a Diagnostic Tool of Hemoglobin-Related Blood Disorders. Sensor. 2008, 8, 7818–7832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.; Gong, j.; Tian, Y. Analysis of Serum from Acute Leukemia Patients Using Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS). Spectroscopy, 2022; 37, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins, C.G.; Buckley, K.; Blades, M.W.; Turner, R.F.B. Raman Spectroscopy of Blood and Blood Components. Appl. Spectrosc. 2017; 71, 767–793. [Google Scholar]

- Albanes, D. β-Carotene and lung cancer: a case study. Volume. 1999, 69, 1345–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.J.; Chiang, C.C.; Immanue, P.N.; Subramania, M. Point-of-Care Testing Blood Coagulation Detectors Using a Bio-Microfluidic Device Accompanied by Raman Spectroscopy. Coatings 2022, 12, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staritzbichler, R.; Hunold, P.; Lopis, I.E.-; Hildebrand, P.W.; Isermann, B.; Kaiser, T. Raman spectroscopy on blood serum samples of patients with end-stage liver disease. PLoS One. 2021, 16, 256045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

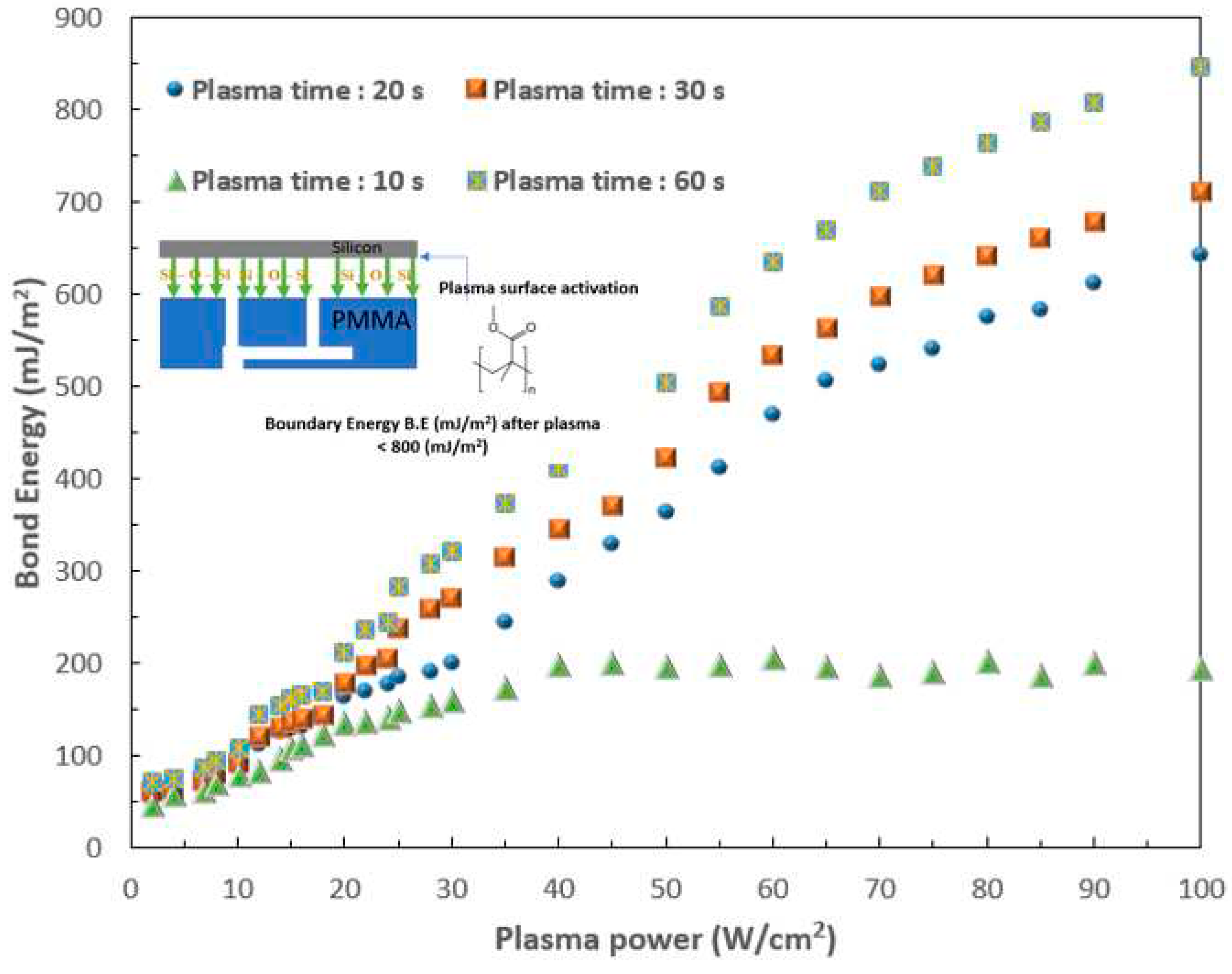

- Chiang, C.-C.; Immanuel, P.; Chiu, Y.-H.; Huang, S.-J. Heterogeneous Bonding of PMMA and Double-Sided Polished Silicon Wafers through H2O Plasma Treatment for Microfluidic Devices. Coatings 2021, 11, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-J.; Lin, M.-T.; Chiang, C.-C.; Arun Dwivedi, K.; Abbas, A. Recent Advancements in Biological Microelectromechanical Systems (BioMEMS) and Biomimetic Coatings. 2022, 12, 1800.

- Sansano, A.; Navarro, R.; Arranz, A.S.; Manrique, J.A. Development of a Spectral Data Base for Exomars’ Raman Instrument (RLS). LPSC. 2014, 45, 2803. [Google Scholar]

- Enejder, A.M.; Koo, T.W.; Oh, J.; Hunter, M.; Sasic, S.; Feld, M.S.; Horowitz, G.L. Blood analysis by Raman spectroscopy. Optics letters. 2002, 27, 2004–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filho, I.T.; Terner, J.; Pittman, R.N.; Somera, S.G. The Effect of Red Blood Cell Velocity on Oxygenation Measurements using Resonance Raman Spectroscopy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005, 289, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.L. Iron Deficiency Anemia: A Common and Curable Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013, 3, 11866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, M. Analysis, Nutrition, and Health Benefits of Tryptophan. Int J Tryptophan Res. 2018, 11, 1178646918802282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, G.A. Current concepts in lactate exchange. Med. Sci. Sports. Exerc. 1991, 23, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, S.P. Lactic Acid and Exercise Performance. Sports Med. 2006, 36, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlawat, S.; Kumar, N.; Uppal, A.; Gupta, P.K. Visible Raman excitation laser induced power and exposure dependent effects in red blood cells. J of Biophotonics. 2016, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankapur, A.; Zachariah, E.; Chidangil, S.; Valiathan, M.; Mathur, D. Raman Tweezers Spectroscopy of Live, Single Red and White Blood Cells. PLoS ONE. 2010, 5, 10407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- .Long, B.; Zheng, W.; Schweitzer, M.; Hallen, H. Resonance Raman imagery of semi-fossilized soft tissues. Volume. 2018, 10753, 1075310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casellaa, M.; Lucotti, A.; Tommasini, M.; Bedoni, M.; Forvi, E.; Gramaticac, F.; Zerbi, G. Raman and SERS recognition of β-carotene and haemoglobin. Volume. 2011, 79, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinesh, K.R. M.; Maguire, A.; Bryant, J.; Arm-strong, J.; Dunne, M.; . Finn, M.; Lyng, F.M.; Meade, A.D. Development of a high throughput (HT) Raman spectroscopy method for rapid screening of liquid blood plasma from prostate cancer patients. The Analyst. 2016, 142, 3763. [Google Scholar]

- Immanuel, P.N.; Chiang, C.-C.; Yang, C.-R.; Subramani, M.; Lee, T.-H.; Huang, S.-J. Surface activation of poly (methyl methacrylate) for microfluidic device bonding through a H2O plasma treatment linked with a low-temperature annealing. Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering 2021, 31, 055004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Raman shift (cm-1) | Vibrational mode | Component |

| 690 | C-C-N bending | Hemoglobin |

| 770 | Ring vibrations | Tryptophan |

| 989 | Aromatic ring breathing | Hemoglobin |

| 1015 | Aromatic ring breathing | Hemoglobin |

| 1092 | C-O vibrations | Lactic acid |

| 1144 | CH3 rocking, C-O vibrations | Lactate |

| 1182 | C-C stretching | Hemoglobin |

| 1233 | Ferrous low spin | Hemoglobin |

| 1315 | C-C stretching | Hemoglobin |

| 1348 | C-H bending | Tryptophan |

| 1385 | CH3 symmetric stretching | Heme |

| 1405 | C==N antisymmetric stretching | Heme |

| 1441 | CH2 bending | Acetates |

| 1562 | Pyrrole ring stretching vibrations | Hemoglobin |

| 1596 | C==N antisymmetric stretching and | Hemoglobin |

| 1613 | C-H bending | Hemoglobin |

| 1651 | Ferrous low spin | Hemoglobin |

| Normal Raman shift (cm-1) | Abnormal blood Raman shift (cm-1) | Vibrational blood mode | Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| 989 | No | Aromatic ring breathing | Hemoglobin |

| 1315 | 1314 | C-C stretching | Hemoglobin |

| 1348 | 1356 | C-H bending | Tryptophan |

| 1562 | 1574 | Pyrrole ring stretching vibrations | Hemoglobin |

| 1596 | 1600 | C==N antisymmetric stretching | Hemoglobin |

| 1613 | No | C-H bending | Hemoglobin |

| 1651 | 1651 | Ferrous low spin | Hemoglobin |

| Abnormal blood Raman shift (cm-1) | Abnormal blood with coagulant Raman shift (cm-1) |

Vibrational mode | Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| 770 | 768 | Ring vibrations | Tryptophan |

| 1185 | 1184 | C-C stretching | Hemoglobin |

| 1318 | 1315 | C-C stretching | Hemoglobin |

| 1356 | 1354 | C-H bending | Tryptophan |

| 1574 | 1577 | Pyrrole ring stretching vibrations |

Hemoglobin |

| Raman shift (cm-1) | Vibrational blood mode | Component |

|---|---|---|

| 694 | C-C-N bending | Hemoglobin |

| 770 | Ring vibrations | Tryptophan |

| 1018 | Aromatic ring breathing | Hemoglobin |

| 1189 | C-C stretching | Hemoglobin |

| 1239 | Ferrous low spin | Hemoglobin |

| 1321 | C-C stretching | Hemoglobin |

| 1354 | C-H bending | Tryptophan |

| 1384 | CH3 symmetric stretch | Heme |

| 1410 | C==N antisymmetric streching | Heme |

| 1443 | CH2 bending | Acetates |

| 1599 | C-H bending | Hemoglobin |

| 1653 | Ferrous low spin | Hemoglobin |

| Raman shift (cm-1) | Vibrational blood mode | Component |

|---|---|---|

| 1016 | C-H bending | β-Carotene |

| 1164 | C-C stretching | β-Carotene |

| 1526 | C-C stretching | β-Carotene |

| Raman shift (cm-1) | Vibrational blood mode | Component |

|---|---|---|

| 1013 | C-H bending | β-Carotene |

| 1172 | C-C stretching | β-Carotene |

| 1526 | C-C stretching | β-Carotene |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).