1. Introduction

In the realm of power systems, the automatic voltage regulator (AVR) stands as a linchpin, ensuring that connected electrical equipment functions within prescribed voltage bounds. The consequences of inadequate voltage regulation can be profound, from equipment damage and operational failures to costly downtime and extensive repairs [

1,

2,

3]. Consequently, the AVR plays a pivotal role in power systems reliant on generators or alternators for electricity generation. While existing control methodologies have achieved some success, they remain encumbered by limitations [

4], including challenges related to robustness, overshoots, rise times, settling times, and persistent steady-state errors.

It is against this backdrop that our study emerges, driven by a shared motivation to push the boundaries of AVR control and contribute to the development of more robust and efficient power systems. Our primary motivation is to propose an advanced control scheme capable of effectively addressing these limitations. To realize this goal, we have developed a novel optimizer, rooted in the arithmetic optimization algorithm (AOA) [

5], meticulously fine-tuned to enhance the parameters of our proposed control scheme and, by extension, its overall performance and adaptability.

In the existing landscape of AVR control, controllers have emerged as indispensable assets for vigilant monitoring and regulation of the AVR itself. These controllers serve as hubs, facilitating real-time adjustments to maintain voltage stability, enabling remote monitoring, fault detection, and automatic shutdown during emergencies, and enhancing the overall system dependability. A range of controllers, from the standard proportional-integral-derivative (PID) to more advanced variants like the PID Acceleration (PIDA), fractional-order PID (FOPID), and PID with a second-order derivative (PIDD

2), offer diverse attributes to meet the specific requirements of AVR control [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

However, the choice of controller alone is insufficient to address the complex challenges faced by AVR systems. The choice of a cost function is equally crucial, as it significantly impacts performance. Researchers employ various cost functions, such as the integral of time-weighted squared error, integral of squared error, integral of absolute error, and the dynamic response performance criteria-based Zwe-Lee Gaing (ZLG) cost function [

14,

15,

16].

In this context, our work introduces a novel approach that unites both the controller and the optimizer to form a comprehensive solution for enhancing AVR stability. The core innovation is the balanced arithmetic optimization algorithm (b-AOA). It marries the powerful pattern search (PS) strategy [

17], renowned for its exploitation capabilities, with the elite opposition-based learning (EOBL) strategy [

18], elevating exploration. This marriage optimizes the controller parameters and the AVR system’s response, harmonizing exploration and exploitation to attain a level of stability previously out of reach.

The efficacy of the b-AOA is first verified through comprehensive assessments against 23 classical unimodal, multimodal, and fixed-dimensional multimodal benchmark functions. These evaluations compare the effectiveness of the proposed b-AOA algorithm to other optimization algorithms, including the original AOA [

5], sine-cosine algorithm [

19], weighted mean of vectors algorithm [

20] and marine predators algorithm [

21]. The results from the benchmark functions underscore the remarkable performance of the b-AOA algorithm. It consistently achieves mean errors close to zero, demonstrating its capability to find accurate solutions. Furthermore, its robustness and consistency make it a strong candidate for addressing a wide range of optimization problems.

In case of AVR system, we firstly introduce a PIDND

2N

2 controller designed for enhanced precision, stability, and responsiveness in voltage regulation. This configuration mitigates the limitations associated with conventional methods, promising superior control performance. Secondly, the b-AOA optimizer fine-tunes the parameters of our proposed control scheme, improving its overall performance and adaptability. Using the ZLG cost function [

22], we target the minimization of dynamic response performance criteria, such as maximum overshoot, steady-state error, settling time, and rise time, thereby ensuring that the AVR system meets the most stringent performance requirements. Our work seeks to transcend theoretical innovation, anchoring itself in the practical applicability of power systems, where stability and reliability are non-negotiable. Through extensive simulations and rigorous experimentation, we aim to demonstrate the superiority of the b-AOA-based AVR system in comparison to existing control and optimization techniques. Our focus on stability, speed of response, robustness, and efficiency aligns with the motivations presented, making our work a substantial contribution to the field of power system control.

To validate the superiority of the proposed b-AOA approach, we conducted extensive comparative analyses, evaluating its performance against well-established control methodologies, such as the sine cosine algorithm (SCA)-based PID controller [

23], whale optimization algorithm (WOA)-based PIDA controller [

24], slime mould algorithm (SMA)-based FOPID controller [

25], and particle swarm optimization (PSO)-based PIDD

2 controller [

26]. The results unequivocally demonstrate that the b-AOA-based approach outshines its counterparts. It exhibits unmatched transient response characteristics, with the shortest rise time (0.033485 s) and settling time (0.050752 s) while eliminating overshoot. In contrast, other methods exhibit less favorable response characteristics. In terms of frequency response, the b-AOA approach consistently excels, showcasing robust stability, favorable gain margins, and a broader bandwidth.

To further assess the effectiveness of the proposed approach, we compared it with several other established controller approaches reported in the literature. These included the several recently reported control methods for the AVR system. These methods include a variety of controllers, each tuned using different optimization algorithms such as marine predators algorithm (MPA) based FOPID [

27], hybrid atom search particle swarm optimization (h-ASPSO) based PID [

28], equilibrium optimizer (EO) based TIλDND2N2 based controller, reptile search algorithm (RSA) based FOPIDD2 [

6], improved Runge-Kutta (iRUN) algorithm based PIDND2N2 [

29], symbiotic organism search (SOS) algorithm-based PID-F [

30], whale optimization algorithm (WOA) based 2DOF FOPI [

31], Lévy flight-based RSA with local search ability (L-RSANM) based PID [

32], chaotic black widow algorithm (ChBWO) based FOPID [

15], genetic algorithm (GA) based fuzzy PID [

33], sine-cosine algorithm (SCA) based FOPID with fractional order filter [

34], hybrid simulated annealing–Manta ray foraging optimization (SA-MRFO) algorithm based PIDD2 [

35], slime mould algorithm (SMA) based PID [

14], gradient based optimization (GBO) based FOPID [

36] and nonlinear SCA based sigmoid PID [

37]. We evaluate their transient response performance to assess the effectiveness of the proposed approach. The results demonstrate the efficacy of the b-AOA-based PIDND

2N

2 controller in comparison to various state-of-the-art methods as it stands out with an impressive performance, suggesting the exceptional stability and responsiveness of the b-AOA-tuned controller.

These important results underscore the significance of our work, offering a superior solution for addressing the challenges in AVR control. It not only contributes to the advancement of power systems but also sets a new benchmark for stability, responsiveness, and reliability in this critical domain.

2. Overview of Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm

The arithmetic optimization algorithm (AOA) draws inspiration from arithmetic principles [

5] to construct a versatile metaheuristic optimization technique. It initiates the optimization process by generating a set of randomized solutions represented as follows.

Following this, the algorithm employs a function known as "Math Optimizer Accelerated" (MopA) to execute exploration and exploitation tasks. The MopA function is defined as:

where

represents the current iteration,

denotes the maximum number of iterations,

and

represent the minimum and maximum values of the accelerated function. The exploration phase of the algorithm is carried out when

, where

is a randomly generated number. During exploration, the multiplication (

) and division (

) operators are employed, defined as follows:

where

represents the

position of solution i at the current iteration,

denotes the solution of

in the next iteration,

signifies the best solution’s

position obtained so far,

is a small integer,

is a control parameter that adjusts the search process,

and

respectively represent the upper and lower bounds of the

position. The "Math optimizer probability" function, denoted by MopP, is computed as follows, with

reflecting the exploitation accuracy through iterations.

The term

is another random number utilized for position updates. The

operator is employed for

, while the

operator is used otherwise. Conversely, the exploitation phase occurs when

. In this stage, the addition (

) and subtraction (

) operators are utilized, defined as.

Here,

is a random number determining whether the

or

operation is applied.

operates when

, while

is used for

.

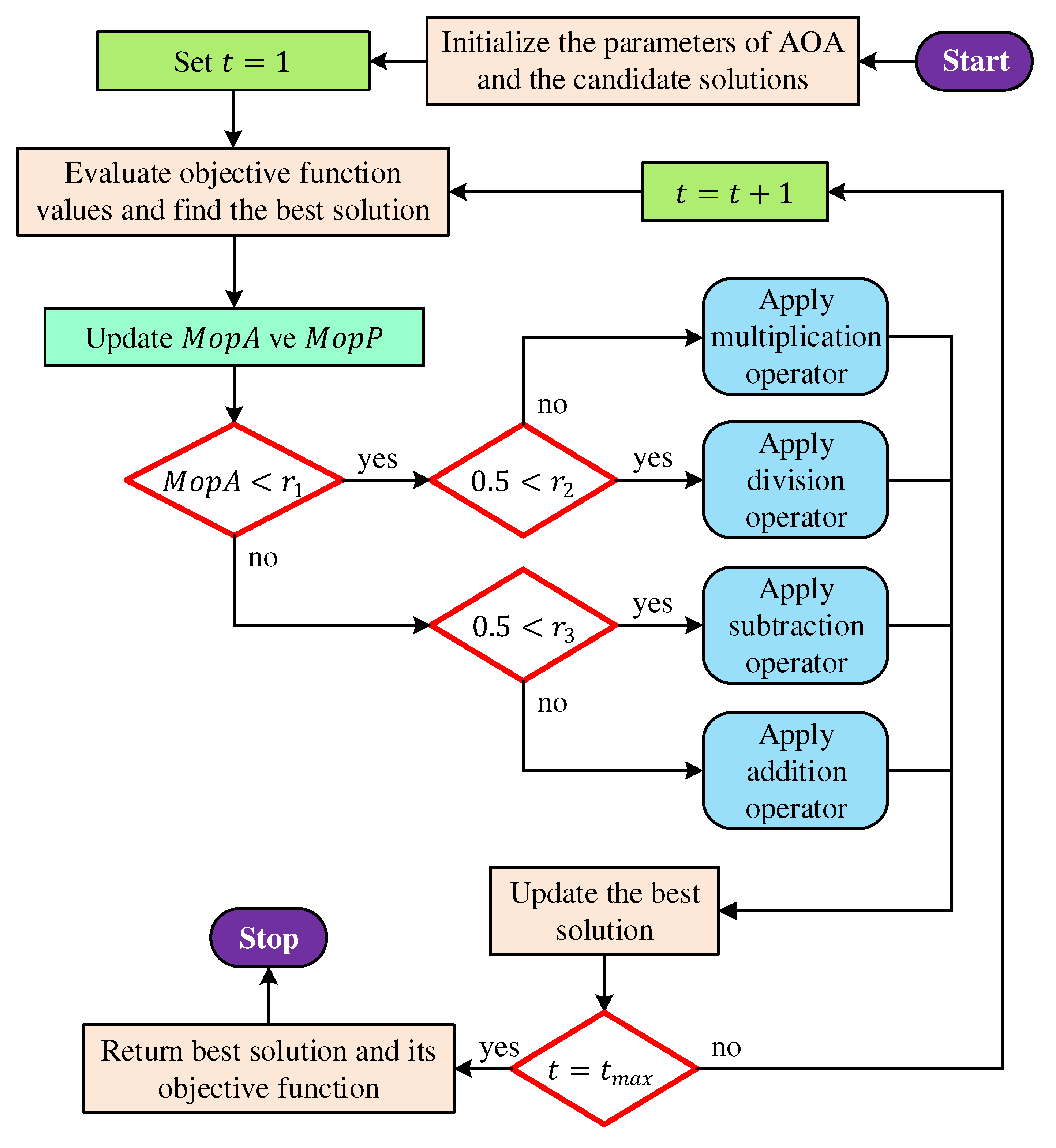

Figure 1 presents a comprehensive flowchart of the AOA, depicting its intricate process.

8. Simulation Results and Discussion

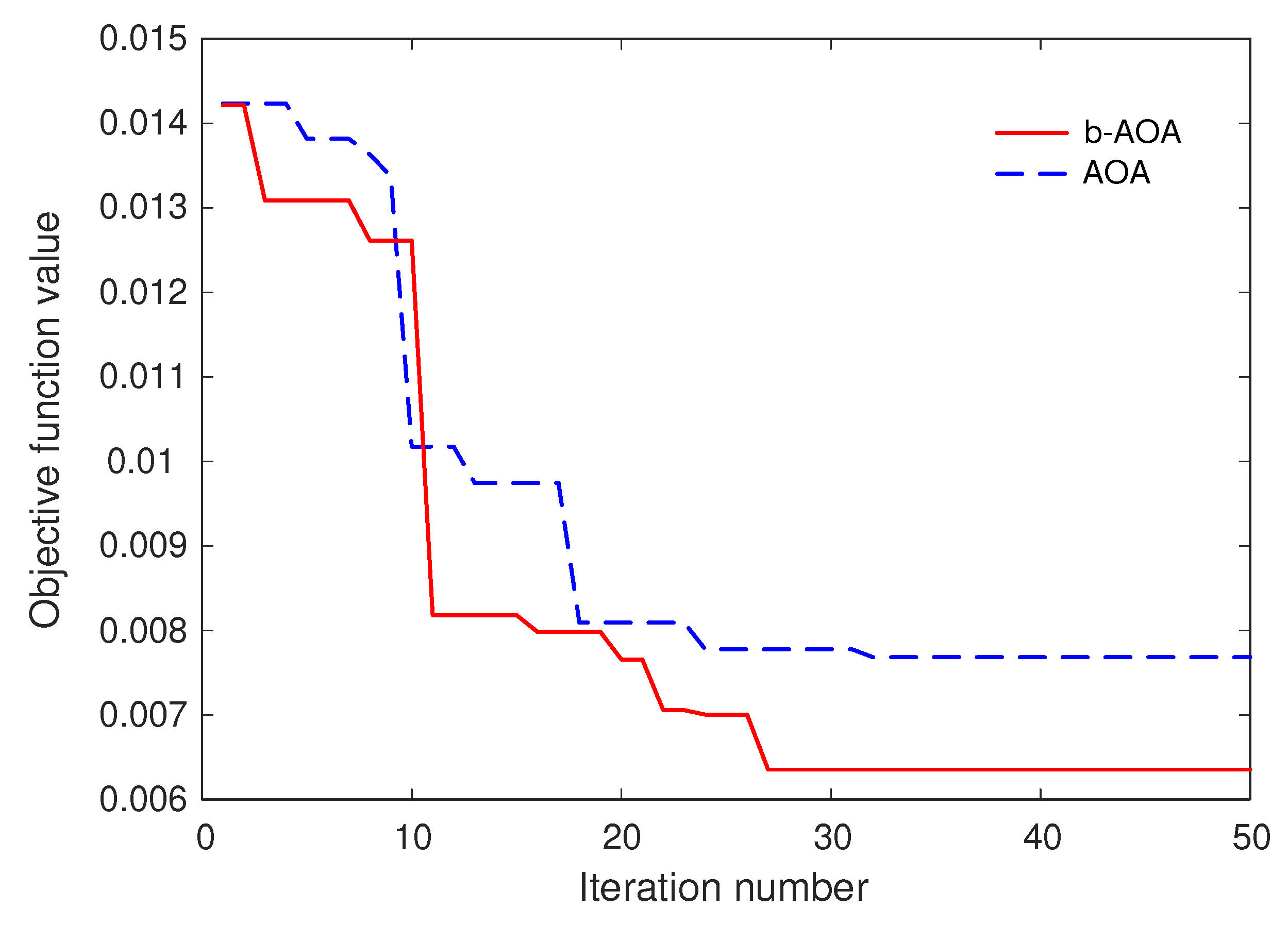

8.1. Statistical Performance of b-AOA and AOA Methods for AVR System

In the optimization of the AVR system, the b-AOA and AOA algorithms were executed 30 times. A population size of 30 and a maximum iteration count of 50 were chosen for minimizing the objective function. The statistical results obtained from all runs are presented in

Table 9. As observed in the table, all statistical metrics for optimizing the F_ZLG objective function favor the b-AOA algorithm, indicating its superior performance. These results additionally confirm the statistical stability of the b-AOA algorithm.

8.2. Obtained Best Controller Parameters and Transfer Functions of the Optimized System

In this section, we discuss the results regarding the best controller parameters and the corresponding transfer functions of the optimized system.

Figure 12 provides the convergence curve, illustrating the progress of the b-AOA and the original AOA algorithms in minimizing the objective function. Notably, it shows that the b-AOA outperforms the original AOA by achieving the lowest objective function value through iterations.

Table 10 presents the optimal parameters of the PIDND

2N

2 controller, obtained using both the b-AOA and the original AOA algorithms.

Using those values would yield the following transfer functions of the optimized systems for original AOA and proposed b-AOA algorithms.

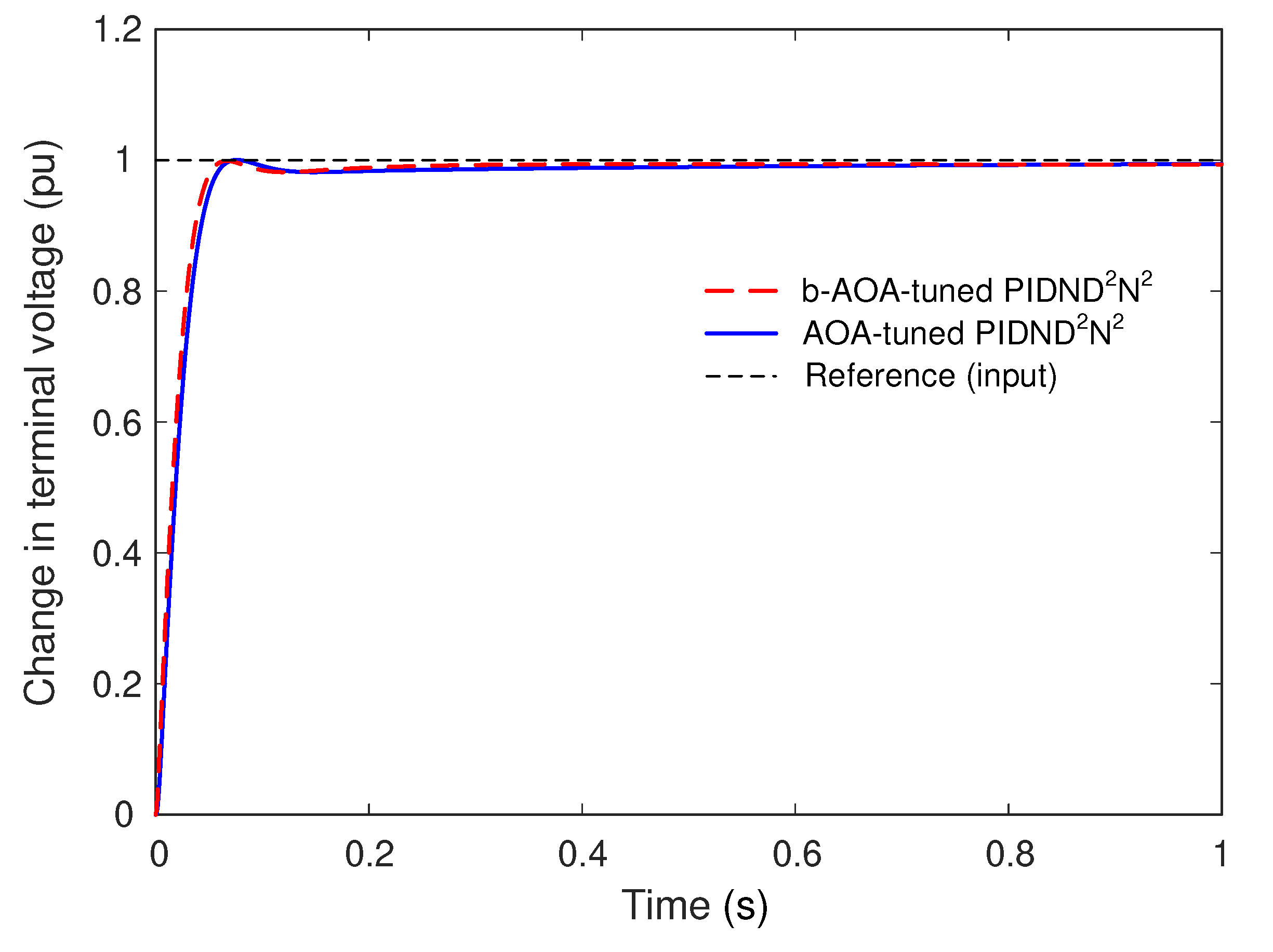

8.3. Stability of the Proposed Design Method

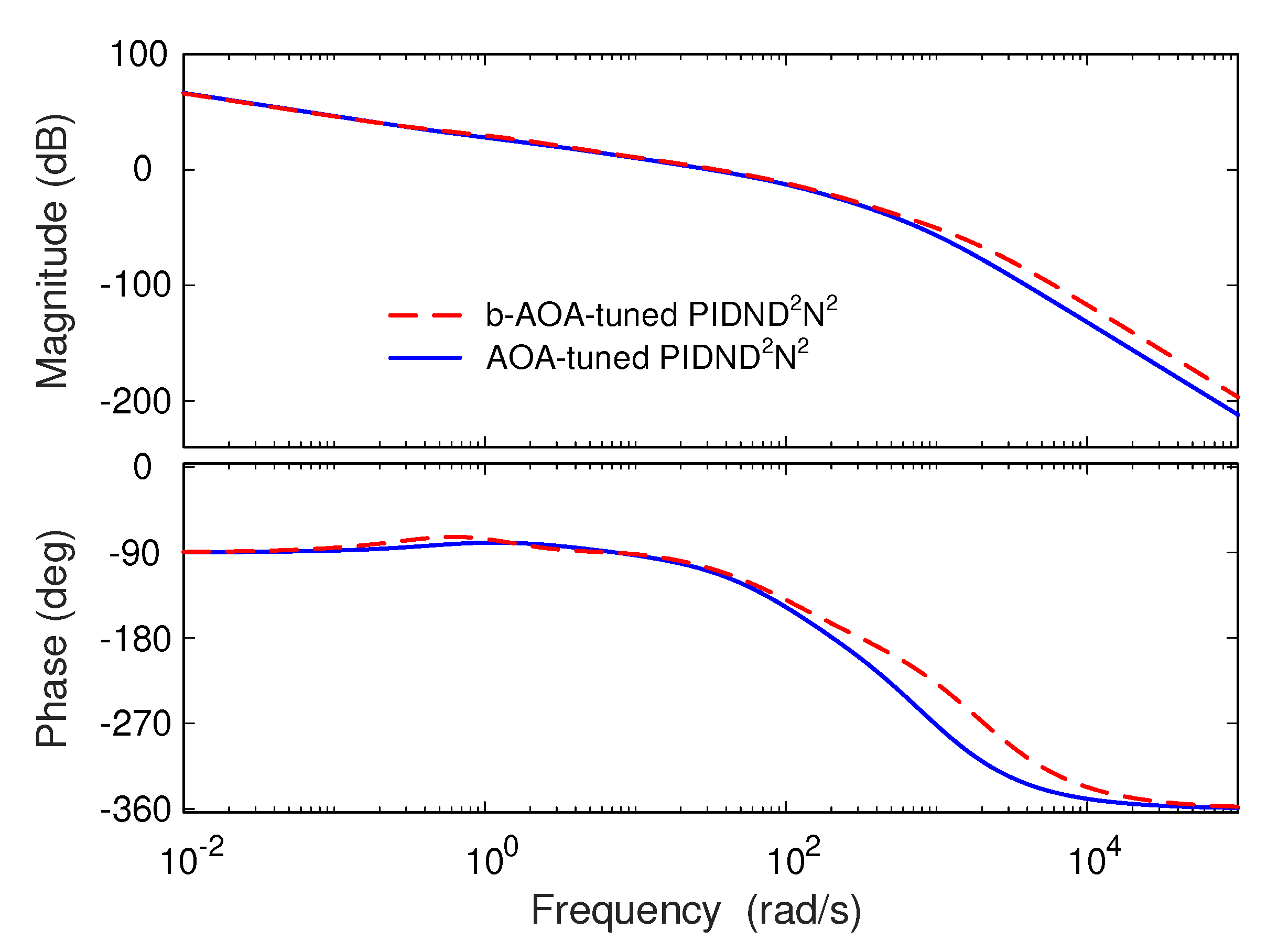

In this section, we analyze the stability of the proposed design method by evaluating the step response and open-loop frequency response of the b-AOA and AOA-tuned PIDND2N2 controllers.

Figure 13 and

Table 11 present the transient response performance metrics for the b-AOA and AOA-tuned PIDND

2N

2 controllers. The step response of both controllers is observed concerning the change in the terminal voltage. As illustrated in

Figure 13, the b-AOA-tuned PIDND2N2 controller exhibits a faster rise time and settling time with zero overshoot compared to the AOA-tuned PIDND

2N

2 controller. This implies that the b-AOA tuned system reaches the desired state more rapidly without oscillations, demonstrating its superior stability in the time domain. The numerical results from

Table 11 confirm these visual observations.

Figure 14 and

Table 12 present the open loop Bode diagrams and frequency response performance metrics for the controllers. In the frequency domain, the b-AOA-tuned PIDND

2N

2 controller showcases a higher phase margin, greater gain margin, and a wider bandwidth compared to the AOA-tuned PIDND

2N

2 controller. These results signify that the b-AOA-based controller maintains better stability and frequency response characteristics, making it superior in terms of overall system stability.

8.4. Compared Algorithms and Respective Transfer Functions

In this section, we provide a comparative analysis of well-known methods in the literature, which employ different types of controllers. The controller types used in these approaches are as follows: sine cosine algorithm (SCA)-based PID controller [

23], whale optimization algorithm (WOA)-based PIDA controller [

24], slime mould algorithm (SMA)-based FOPID controller [

25], and particle swarm optimization (PSO)-based PIDD

2 controller [

26].

The parameters for the SCA-based PID controller [

23] are as follows:

,

and

. The transfer function of the closed-loop AVR system using this approach is given by the following equation.

The parameters for the WOA-based PIDA controller [

24] are as follows:

,

,

,

,

and

. The transfer function of the closed-loop AVR system using this approach is given by the following equation.

The parameters for the SMA-based FOPID controller [

25] are as follows:

,

,

,

and

. The transfer function of the closed-loop AVR system using this approach is given by the following equation.

The parameters for the PSO-based PIDD

2 controller [

26] are as follows:

,

,

and

. The transfer function of the closed-loop AVR system using this approach is given by the following equation.

These equations define the transfer functions of the AVR systems under the influence of different control methods. The following subsections provide a comparative analysis of these methods based on various performance criteria.

8.5. Comparative Transient Response Analysis

Figure 15 displays the comparative step response of different control approaches for the AVR system. This figure visually represents the transient response of various control methods and provides insights into their performance. The step response graph shows how each method reacts to a change in the terminal voltage.

Table 13 complements the visual representation by providing numerical values for the transient response metrics of different control approaches. These metrics include the rise time, settling time, and overshoot, which are essential indicators of the system’s dynamic behavior.

Upon analyzing both the figure and the table, it becomes evident that the b-AOA-tuned PIDND2N2 controller excels in achieving a superior transient response compared to other control approaches. It exhibits the shortest rise time (0.033485 s) and settling time (0.050752 s) while completely eliminating overshoot. In contrast, the other control methods, including AOA, SCA-tuned PID, WOA-tuned PIDA, SMA-tuned FOPID, and PSO-tuned PIDD2, exhibit longer rise and settling times and, in some cases, significant overshoot. These results emphasize the superiority of the b-AOA-based control approach in providing a faster and more stable transient response, which is crucial for maintaining the AVR system’s stability and performance during dynamic voltage changes.

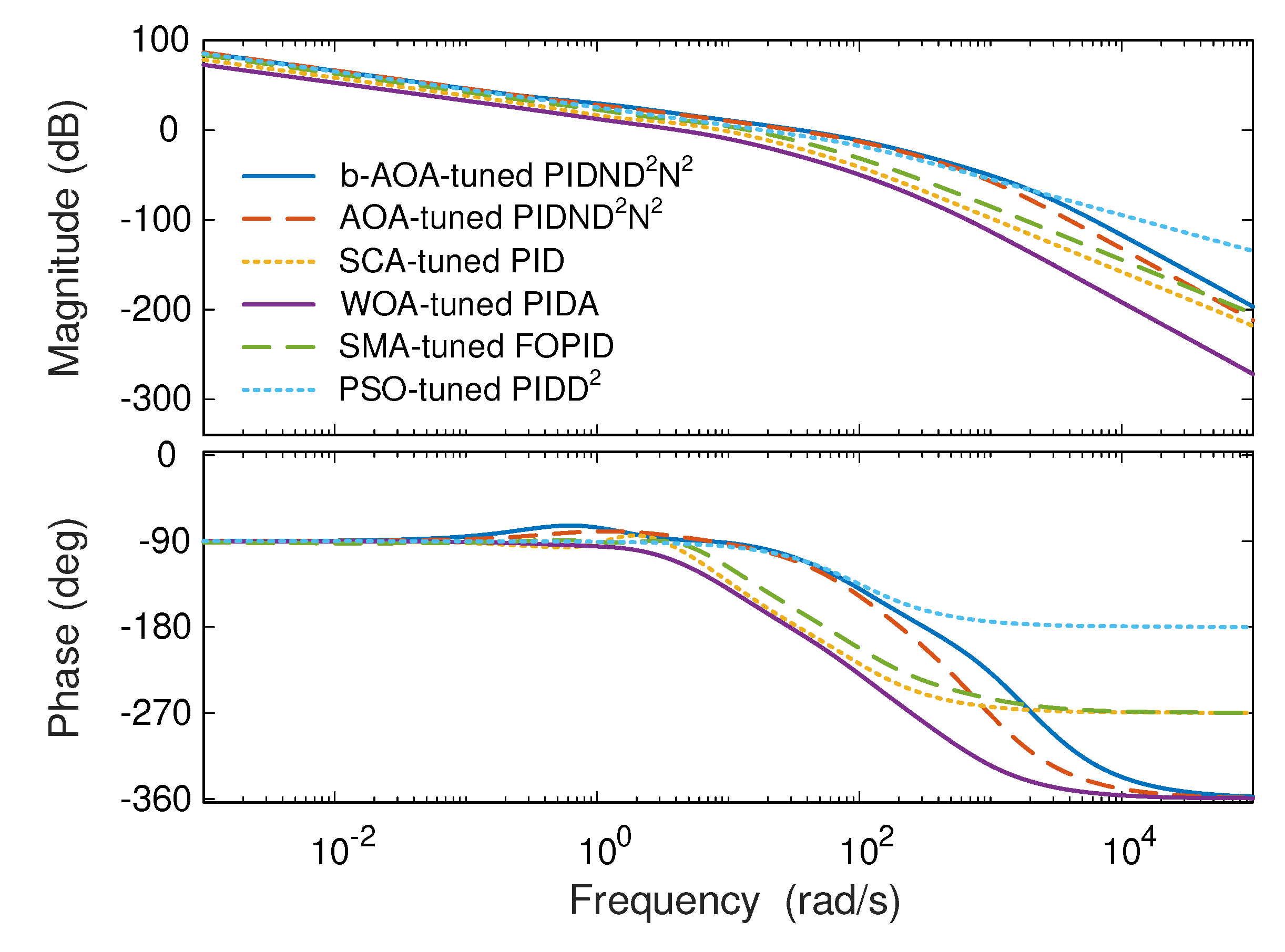

8.6. Comparative Frequency Response Analysis

Figure 16 provides a comparative view of Bode diagrams for different control approaches applied to the AVR system. These diagrams illustrate the frequency response characteristics of each control method, offering insights into how they perform across a range of frequencies.

Table 14 complements the visual representation with numerical values that quantify the frequency response metrics for each control approach. These metrics include the phase margin, gain margin, and bandwidth, which are crucial indicators of the system’s stability and ability to handle varying frequencies.

Upon analyzing both the figure and the table, it is clear that the b-AOA-tuned PIDND2N2 controller stands out as the superior choice for frequency response analysis. It exhibits the highest phase margin (70.797°), indicating robust stability and the most favorable gain margin (28.888 dB) among all the methods, ensuring ample room for gain adjustments without instability. Moreover, it possesses the widest bandwidth (64.82 rad/s), signifying a faster system response to frequency variations. In contrast, the other control approaches, including AOA-tuned PIDND2N2, SCA-tuned PID, WOA-tuned PIDA, SMA-tuned FOPID, and PSO-tuned PIDD2, generally display lower phase margins, lower gain margins, and narrower bandwidths. The b-AOA-based controller, on the other hand, excels in maintaining system stability across a broad frequency range and offers improved performance for handling dynamic frequency changes. These results underscore the superiority of the b-AOA-tuned PIDND2N2 controller in providing robust and responsive frequency characteristics, which are vital for the stable and efficient operation of the AVR system under various operating conditions.

8.7. Comparisons with the Reported Recent Works

In this section, we compare the proposed PIDND2N2 controller tuned with b-AOA to several recently reported control methods for the AVR system. These methods include a variety of controllers, each tuned using different optimization algorithms such as marine predators algorithm (MPA) based FOPID [

27], hybrid atom search particle swarm optimization (h-ASPSO) based PID [

28], equilibrium optimizer (EO) based TIλDND2N2 based controller, reptile search algorithm (RSA) based FOPIDD2 [

6], improved Runge-Kutta (iRUN) algorithm based PIDND2N2 [

29], symbiotic organism search (SOS) algorithm-based PID-F [

30], whale optimization algorithm (WOA) based 2DOF FOPI [

31], Lévy flight-based RSA with local search ability (L-RSANM) based PID [

32], chaotic black widow algorithm (ChBWO) based FOPID [

15], genetic algorithm (GA) based fuzzy PID [

33], sine-cosine algorithm (SCA) based FOPID with fractional order filter [

34], hybrid simulated annealing–Manta ray foraging optimization (SA-MRFO) algorithm based PIDD2 [

35], slime mould algorithm (SMA) based PID [

14], gradient based optimization (GBO) based FOPID [

36] and nonlinear SCA based sigmoid PID [

37].

We evaluate their transient response performance to assess the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

Table 15 provides a comprehensive overview of the transient response metrics, including rise time, settling time, and overshoot, for the proposed approach and other recent methods. The results demonstrate the efficacy of the b-AOA-based PIDND

2N

2 controller in comparison to various state-of-the-art methods as it stands out with an impressive performance, featuring a remarkably low rise time (0.033485s), a fast settling time (0.050752s), and zero overshoot. This suggests the exceptional stability and responsiveness of the b-AOA-tuned controller. Therefore, the table clearly illustrates the effectiveness of the proposed b-AOA-based PIDND

2N

2 controller in achieving rapid responses and maintaining stable performance, as evidenced by its minimal overshoot. It consistently outperforms or rivals the other methods in the evaluation, reinforcing its superiority for the AVR system’s transient response.

9. Conclusion and Future Works

In this study, we have introduced a novel approach to enhance the control of AVR in power systems. By uniting a PIDND2N2 controller with the novel b-AOA, we aimed to address the limitations associated with conventional methods. The introduction of the PIDND2N2 controller offers enhanced precision, stability, and responsiveness in voltage regulation. This innovative configuration mitigates the shortcomings of existing approaches, promising superior control performance. The b-AOA optimizer, meticulously fine-tuned with the integration of PS and EOBL strategies into original AOA in order to demonstrate exceptional performance. The assessment on 23 benchmark functions show that it consistently achieves accurate solutions, exhibits robustness in addressing various optimization problems, and showcases remarkable potential for a wide range of applications. Extensive comparative analyses reveal the superiority of the proposed approach in transient response characteristics. The b-AOA-based AVR control approach excels in rise time, settling time, and overshoot, outperforming other methods. It also ensures robust stability with favorable gain margins and a broader bandwidth, offering improved performance for handling dynamic frequency changes. The results of our work set a new benchmark for AVR control, advancing stability, responsiveness, and reliability in power systems.

Future work in this domain may focus on several aspects. Further refinement of the b-AOA optimization framework, exploring additional optimization problems, and evaluating its applicability to diverse domains are promising directions. Investigating the practical implementation of the proposed control scheme in real-world power systems and conducting extensive field testing would provide valuable insights. In addition, the AVR system can be considered as an important field of study in which it can play a critical role in the realization of the efficient voltage regulation in smart grids. Additionally, the integration of emerging technologies, such as machine learning and artificial intelligence, into AVR control systems may offer opportunities for further enhancement. The quest for more efficient, stable, and responsive AVR systems remains a vibrant field of research with potential breakthroughs on the horizon.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the original arithmetic optimization algorithm.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the original arithmetic optimization algorithm.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of pattern search method.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of pattern search method.

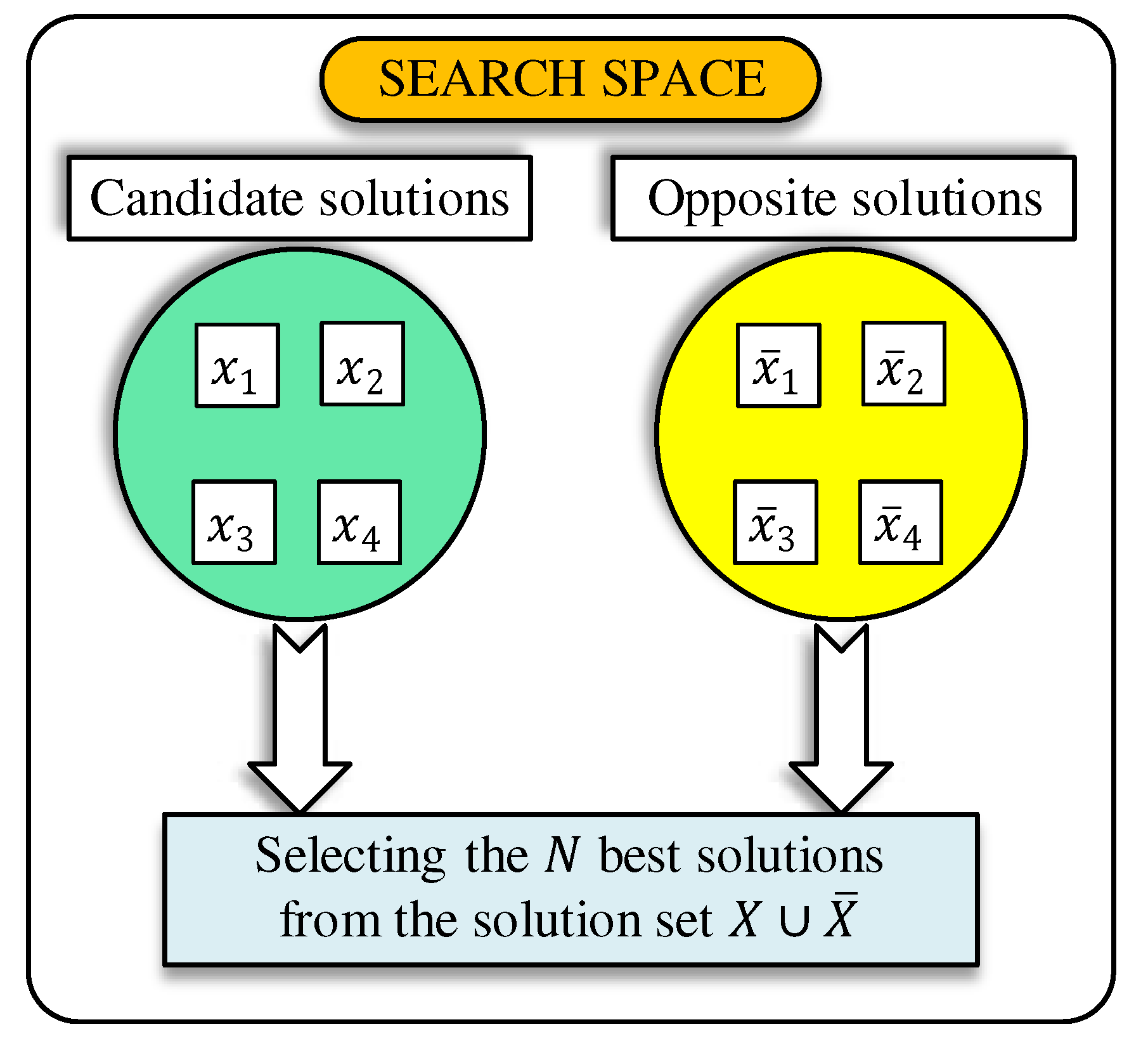

Figure 3.

Working principle of OBL mechanism.

Figure 3.

Working principle of OBL mechanism.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of proposed b-AOA algorithm.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of proposed b-AOA algorithm.

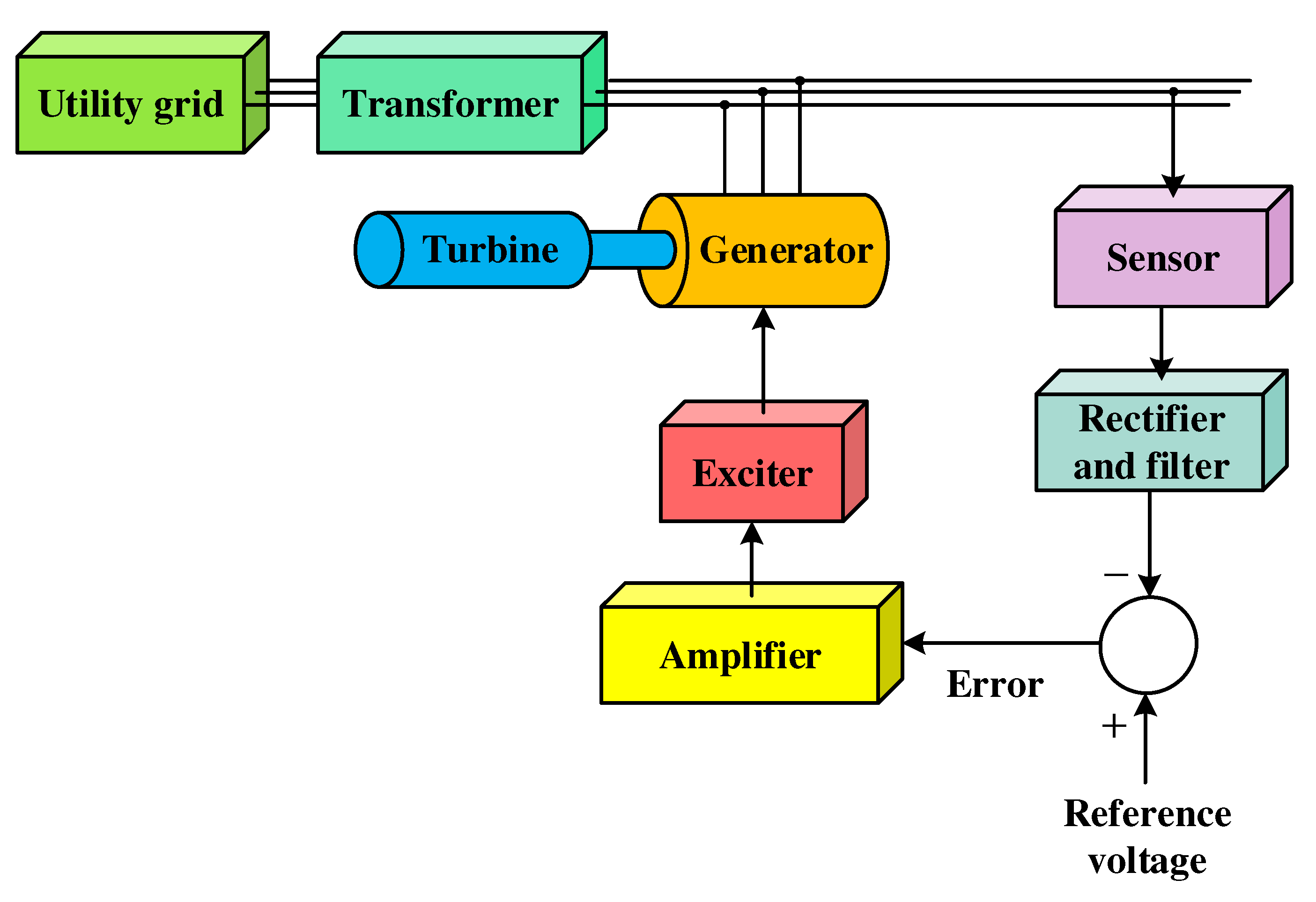

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of a typical AVR system.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of a typical AVR system.

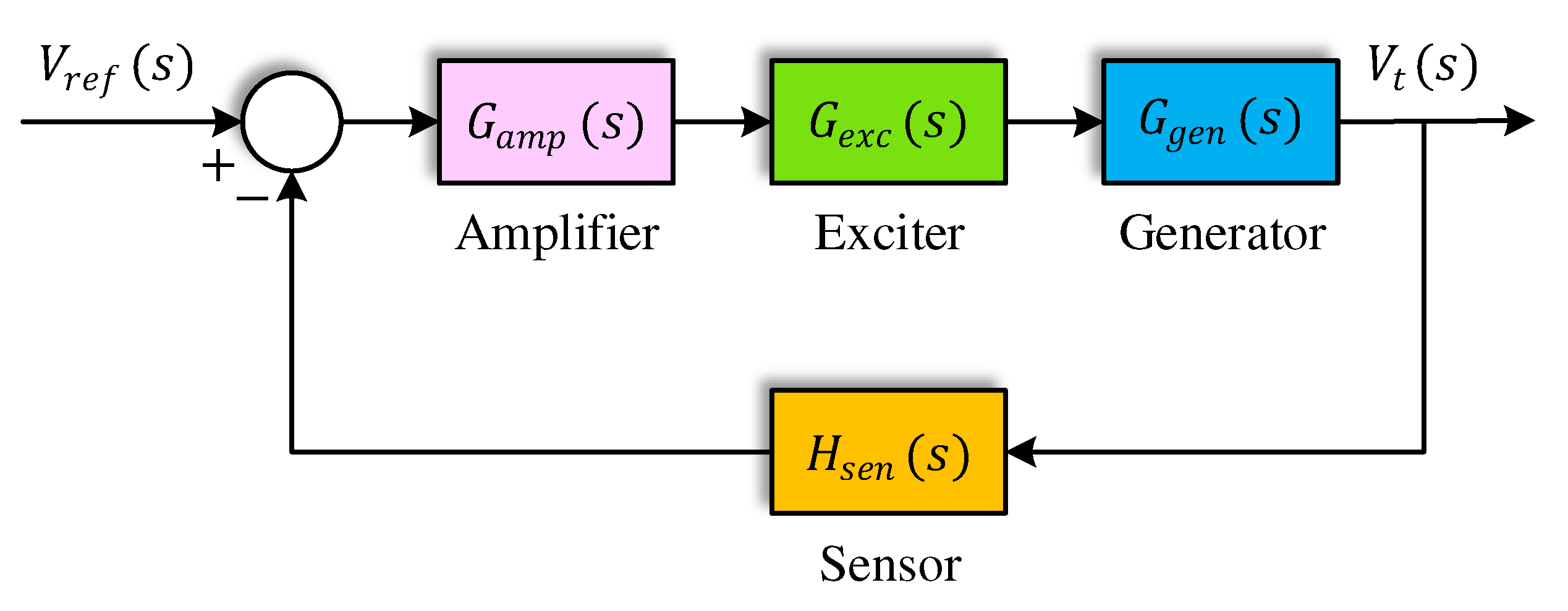

Figure 6.

An Uncontrolled AVR system.

Figure 6.

An Uncontrolled AVR system.

Figure 7.

Pole-zero map of uncontrolled AVR system.

Figure 7.

Pole-zero map of uncontrolled AVR system.

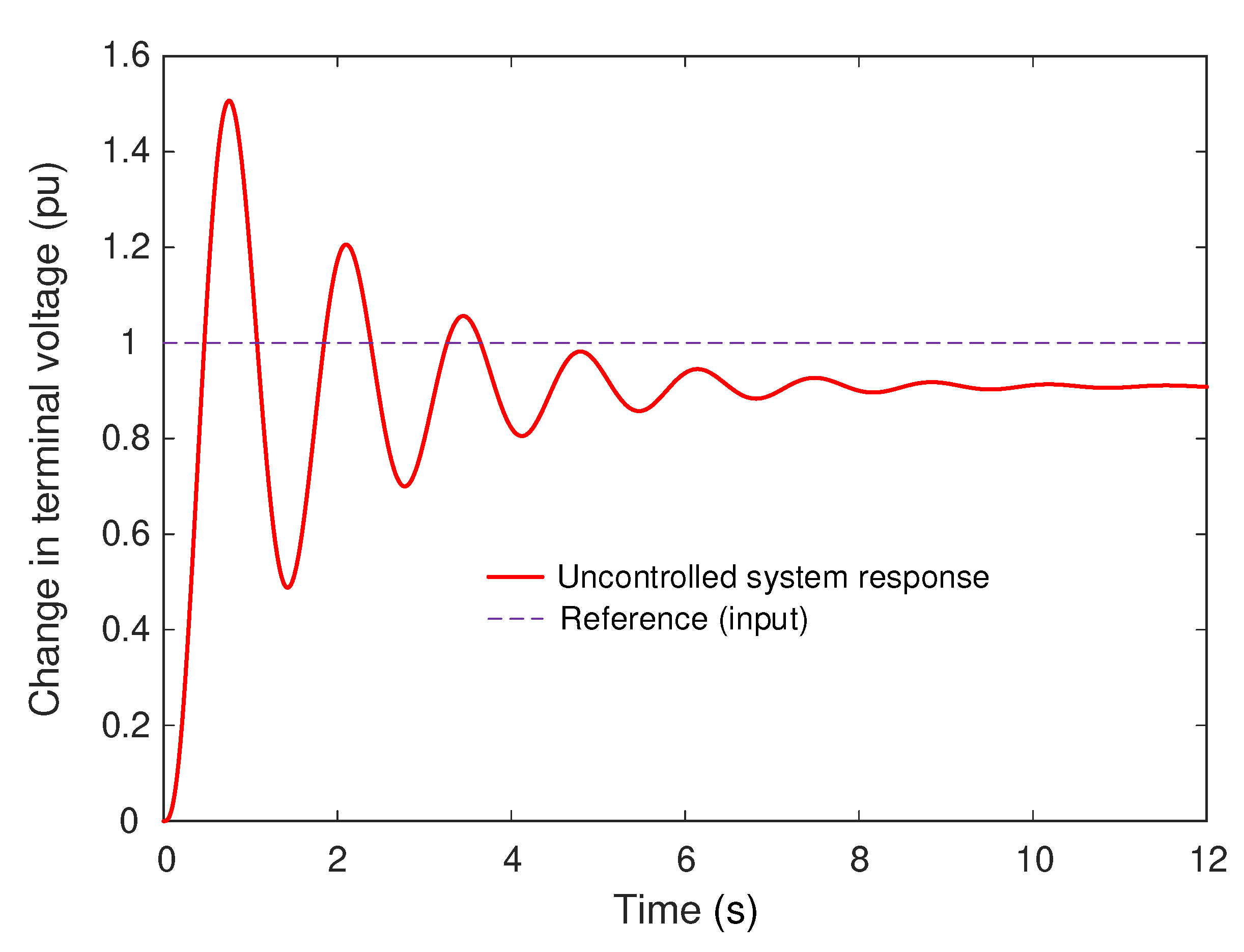

Figure 8.

Step response of the uncontrolled AVR system.

Figure 8.

Step response of the uncontrolled AVR system.

Figure 9.

Open loop Bode plot of the uncontrolled AVR system.

Figure 9.

Open loop Bode plot of the uncontrolled AVR system.

Figure 10.

Block diagram of PIDND2N2 controller.

Figure 10.

Block diagram of PIDND2N2 controller.

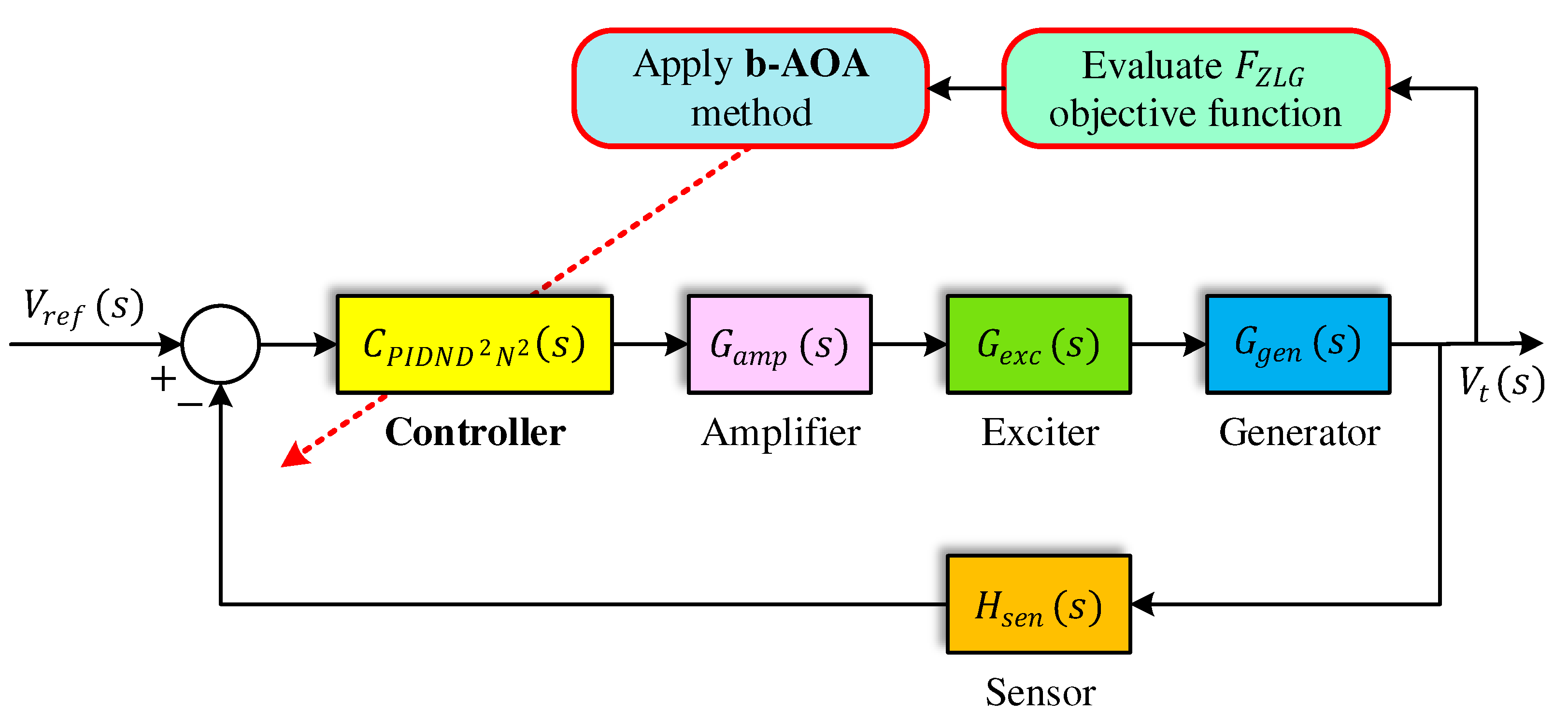

Figure 11.

The block diagram of the implementation of the proposed approach to AVR system.

Figure 11.

The block diagram of the implementation of the proposed approach to AVR system.

Figure 12.

Convergence curve for b-AOA and original AOA

Figure 12.

Convergence curve for b-AOA and original AOA

Figure 13.

Step response of b-AOA and AOA-tuned PIDND2N2 controllers for the change in the terminal voltage.

Figure 13.

Step response of b-AOA and AOA-tuned PIDND2N2 controllers for the change in the terminal voltage.

Figure 14.

Open loop Bode diagrams for b-AOA and AOA-tuned PIDND2N2 controllers

Figure 14.

Open loop Bode diagrams for b-AOA and AOA-tuned PIDND2N2 controllers

Figure 15.

Comparative step response of different control approaches for AVR system

Figure 15.

Comparative step response of different control approaches for AVR system

Figure 16.

Comparative Bode diagrams of different control approaches for AVR system

Figure 16.

Comparative Bode diagrams of different control approaches for AVR system

Table 1.

Properties of the adopted unimodal benchmark functions.

Table 1.

Properties of the adopted unimodal benchmark functions.

| Name |

Function |

Dimension |

Evaluation interval |

Global minimum |

| Sphere |

|

30 |

|

0 |

| Schwefel 2.2 |

|

30 |

|

0 |

| Schwefel 1.2 |

|

30 |

|

0 |

| Schwefel 2.21 |

|

30 |

|

0 |

| Rosenbrock |

|

30 |

|

0 |

| Step |

|

30 |

|

0 |

| Quartic |

|

30 |

|

0 |

Table 2.

Properties of the adopted multimodal benchmark functions.

Table 2.

Properties of the adopted multimodal benchmark functions.

| Name |

Function |

Dimension |

Evaluation interval |

Global minimum |

| Schwefel |

|

30 |

|

−1.2569E+04 |

| Rastrigin |

|

30 |

|

0 |

| Ackley |

|

30 |

|

0 |

| Griewank |

|

30 |

|

0 |

| Penalized |

|

30 |

|

0 |

| Penalized2 |

|

30 |

|

0 |

Table 3.

Properties of the adopted fixed-dimensional multimodal benchmark functions.

Table 3.

Properties of the adopted fixed-dimensional multimodal benchmark functions.

| Name |

Function |

Dimension |

Evaluation interval |

Global minimum |

| Foxholes |

|

2 |

|

0.998 |

| Kowalik |

|

4 |

|

3.0749E−04 |

| Six-Hump Camel |

|

2 |

|

−1.0316 |

| Branin |

|

2 |

|

0.39789 |

| Goldstein-Price |

|

2 |

|

3 |

| Hartman 3 |

|

3 |

|

−3.8628 |

| Hartman 6 |

|

6 |

|

−3.322 |

| Shekel 5 |

|

4 |

|

−10.1532 |

| Shekel 7 |

|

4 |

|

−10.4029 |

| Shekel 10 |

|

4 |

|

−10.5364 |

Table 4.

Properties of the compared algorithms (population size, total iteration number, values of other control parameters).

Table 4.

Properties of the compared algorithms (population size, total iteration number, values of other control parameters).

| Algorithm |

Population size |

Total iteration number |

Values of other control parameters |

| b-AOA |

30 |

500 |

, , , , , , ,

|

| AOA [5] |

30 |

500 |

, , ,

|

| SCA [19] |

30 |

500 |

|

| INFO [20] |

30 |

500 |

,

|

| MPA [21] |

30 |

500 |

,

|

Table 5.

Comparative statistical results obtained from unimodal benchmark functions.

Table 5.

Comparative statistical results obtained from unimodal benchmark functions.

| Function |

Algorithm |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

Best |

Worst |

|

b-AOA |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| AOA |

0.00029656 |

0.0011413 |

3.9226E−38 |

0.0060134 |

| SCA |

16.537 |

36.426 |

9.5633E−06 |

175.47 |

| INFO |

1.0185E−53 |

4.997E−54 |

3.3545E−55 |

2.0178E−53 |

| MPA |

4.0116E−23 |

6.3963E−23 |

3.6461E−25 |

2.7727E−22 |

|

b-AOA |

8.5996E−241 |

0 |

4.333E−320 |

2.2954E−239 |

| AOA |

2.8674E−186 |

0 |

9.6235E−296 |

8.6022E−185 |

| SCA |

0.021241 |

0.031567 |

0.00013767 |

0.13042 |

| INFO |

1.0943E−26 |

3.6605E−27 |

4.7283E−27 |

1.9892E−26 |

| MPA |

2.6444E−13 |

2.8514E−13 |

8.2406E−15 |

1.2622E−12 |

|

b-AOA |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| AOA |

1.6011 |

3.3816 |

1.3815E−07 |

16.177 |

| SCA |

8640.8 |

4939.5 |

1709.5 |

20103 |

| INFO |

1.4606E−50 |

1.1602E−50 |

8.6654E−52 |

3.9712E−50 |

| MPA |

9.9612E−05 |

0.00022346 |

7.2658E−09 |

0.001186 |

|

b-AOA |

9.0422E−244 |

0 |

1.2808E−253 |

2.6479E−242 |

| AOA |

0.15416 |

0.094877 |

0.014632 |

0.36318 |

| SCA |

37.033 |

13.087 |

12.166 |

61.964 |

| INFO |

2.1028E−27 |

1.4215E−27 |

3.5852E−28 |

7.4954E−27 |

| MPA |

2.7542E−09 |

1.5152E−09 |

3.1553E−10 |

6.0257E−09 |

|

b-AOA |

0.61615 |

1.8814 |

3.0737E−09 |

6.3967 |

| AOA |

28.693 |

0.27549 |

27.902 |

29.18 |

| SCA |

1.3673E+05 |

3.2682E+05 |

107.54 |

1175700 |

| INFO |

22.585 |

0.51711 |

21.298 |

23.462 |

| MPA |

25.268 |

0.45451 |

24.487 |

26.042 |

|

b-AOA |

2.4395E−12 |

9.2009E−13 |

1.086E−12 |

5.8521E−12 |

| AOA |

3.7524 |

0.33331 |

3.0561 |

4.4582 |

| SCA |

14.254 |

13.542 |

4.7191 |

55.025 |

| INFO |

1.2654E−08 |

3.7987E−08 |

3.9266E−11 |

2.07E−07 |

| MPA |

4.1868E−08 |

2.2575E−08 |

1.3296E−08 |

1.2965E−07 |

|

b-AOA |

3.629E−05 |

2.8489E−05 |

6.8524E−07 |

0.00010771 |

| AOA |

9.4896E−05 |

7.1313E−05 |

2.0672E−06 |

0.00029718 |

| SCA |

0.099158 |

0.090509 |

0.0085847 |

0.44986 |

| INFO |

0.0015937 |

0.0012634 |

0.00017227 |

0.0049221 |

| MPA |

0.0013495 |

0.00060352 |

0.00041966 |

0.0026601 |

Table 6.

Comparative statistical results obtained from multimodal benchmark functions.

Table 6.

Comparative statistical results obtained from multimodal benchmark functions.

| Function |

Algorithm |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

Best |

Worst |

|

b-AOA |

−12536 |

172.87 |

−12569 |

−11623 |

| AOA |

−7980.7 |

446.84 |

−9196.5 |

−7230.3 |

| SCA |

−3848.4 |

286.86 |

−4371 |

−3283.7 |

| INFO |

−8630.7 |

700.38 |

−9763.3 |

−7101.2 |

| MPA |

−8736.9 |

438.15 |

−9687.9 |

−7946.9 |

|

b-AOA |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| AOA |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| SCA |

29.308 |

30.189 |

0.13996 |

122.46 |

| INFO |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| MPA |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

b-AOA |

8.8818E−16 |

0 |

8.8818E−16 |

8.8818E−16 |

| AOA |

8.8818E−16 |

0 |

8.8818E−16 |

8.8818E−16 |

| SCA |

14.208 |

8.3212 |

0.043401 |

20.382 |

| INFO |

8.8818E−16 |

0 |

8.8818E−16 |

8.8818E−16 |

| MPA |

1.7196E−12 |

1.1519E−12 |

2.7045E−13 |

5.8482E−12 |

|

b-AOA |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| AOA |

194.12 |

65.896 |

72.408 |

323.52 |

| SCA |

0.84569 |

0.41164 |

0.23545 |

1.9083 |

| INFO |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| MPA |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

b-AOA |

2.1943E−13 |

1.5539E−13 |

5.0331E−14 |

6.0379E−13 |

| AOA |

0.29154 |

0.053809 |

0.14538 |

0.43947 |

| SCA |

52428 |

1.5261E+05 |

1.0947 |

614430 |

| INFO |

1.4456E−09 |

2.8117E−09 |

5.3463E−12 |

1.1459E−08 |

| MPA |

0.00014286 |

0.0005059 |

2.4157E−09 |

0.0023059 |

|

b-AOA |

3.1668E−12 |

2.4141E−12 |

7.6907E−13 |

9.0849E−12 |

| AOA |

2.4484 |

0.16915 |

2.1217 |

2.8078 |

| SCA |

1.0872E+05 |

2.7869E+05 |

2.2042 |

1305400 |

| INFO |

0.063752 |

0.14273 |

3.2034E−10 |

0.69157 |

| MPA |

0.012215 |

0.036876 |

2.8969E−08 |

0.19763 |

Table 7.

Comparative statistical results obtained from fixed-dimensional multimodal benchmark functions.

Table 7.

Comparative statistical results obtained from fixed-dimensional multimodal benchmark functions.

| Function |

Algorithm |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

Best |

Worst |

|

b-AOA |

0.998 |

1.5701E−17 |

0.998 |

0.998 |

| AOA |

8.3696 |

3.2389 |

0.998 |

12.671 |

| SCA |

1.795 |

0.9859 |

0.998 |

2.9821 |

| INFO |

2.1111 |

2.5903 |

0.998 |

10.763 |

| MPA |

0.998 |

1.515E−16 |

0.998 |

0.998 |

|

b-AOA |

0.00030749 |

1.4923E−15 |

0.00030749 |

0.00030749 |

| AOA |

0.015417 |

0.025604 |

0.00037189 |

0.11249 |

| SCA |

0.0010661 |

0.00037002 |

0.0005829 |

0.0015477 |

| INFO |

0.0024352 |

0.0060863 |

0.00030749 |

0.020363 |

| MPA |

0.00030749 |

4.3122E−15 |

0.00030749 |

0.00030749 |

|

b-AOA |

−1.0316 |

1.9902E−16 |

−1.0316 |

−1.0316 |

| AOA |

−1.0316 |

6.0816E−07 |

−1.0316 |

−1.0316 |

| SCA |

−1.0316 |

3.7905E−05 |

−1.0316 |

−1.0315 |

| INFO |

−1.0316 |

6.5843E−16 |

−1.0316 |

−1.0316 |

| MPA |

−1.0316 |

4.4024E−16 |

−1.0316 |

−1.0316 |

|

b-AOA |

0.39789 |

0 |

0.39789 |

0.39789 |

| AOA |

0.40987 |

0.009864 |

0.39844 |

0.43767 |

| SCA |

0.40026 |

0.0023543 |

0.39797 |

0.40949 |

| INFO |

0.39789 |

0 |

0.39789 |

0.39789 |

| MPA |

0.39789 |

9.5078E−15 |

0.39789 |

0.39789 |

|

b-AOA |

3 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

| AOA |

6.6 |

9.3351 |

3 |

30 |

| SCA |

3 |

5.4359E−05 |

3 |

3.0002 |

| INFO |

3 |

8.6883E−16 |

3 |

3 |

| MPA |

3 |

2.1709E−15 |

3 |

3 |

|

b-AOA |

−3.8628 |

2.4116E−15 |

−3.8628 |

−3.8628 |

| AOA |

−3.8523 |

0.0038518 |

−3.8593 |

−3.842 |

| SCA |

−3.8547 |

0.0024361 |

−3.861 |

−3.8495 |

| INFO |

−3.8628 |

2.6823E−15 |

−3.8628 |

−3.8628 |

| MPA |

−3.8628 |

2.4945E−15 |

−3.8628 |

−3.8628 |

|

b-AOA |

−3.322 |

2.1608E−13 |

−3.322 |

−3.322 |

| AOA |

−3.0471 |

0.091025 |

−3.1762 |

−2.8234 |

| SCA |

−2.8784 |

0.34163 |

−3.1199 |

−1.6747 |

| INFO |

−3.2784 |

0.058273 |

−3.322 |

−3.2031 |

| MPA |

−3.322 |

1.7554E−11 |

−3.322 |

−3.322 |

|

b-AOA |

−10.153 |

7.6605E−13 |

−10.153 |

−10.153 |

| AOA |

−3.5023 |

1.1997 |

−6.0307 |

−1.8035 |

| SCA |

−2.6202 |

2.0715 |

−7.8686 |

−0.49728 |

| INFO |

−9.1039 |

2.4723 |

−10.153 |

−2.6305 |

| MPA |

−10.153 |

4.1471E−11 |

−10.153 |

−10.153 |

|

b-AOA |

−10.403 |

1.1144E−12 |

−10.403 |

−10.403 |

| AOA |

−3.5619 |

1.2118 |

−6.8762 |

−1.4002 |

| SCA |

−3.2023 |

1.8303 |

−5.9956 |

−0.52105 |

| INFO |

−9.0488 |

2.7774 |

−10.403 |

−2.7659 |

| MPA |

−10.403 |

5.9857E−11 |

−10.403 |

−10.403 |

|

b-AOA |

−10.536 |

3.2315E−12 |

−10.536 |

−10.536 |

| AOA |

−3.8733 |

1.6156 |

−6.5892 |

−1.5825 |

| SCA |

−3.7421 |

1.7935 |

−6.1434 |

−0.94135 |

| INFO |

−9.0039 |

3.151 |

−10.536 |

−2.4217 |

| MPA |

−10.536 |

2.5368E−11 |

−10.536 |

−10.536 |

Table 8.

Boundaries for PIDND2N2 Controller parameters.

Table 8.

Boundaries for PIDND2N2 Controller parameters.

| Bound |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lower |

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

0.001 |

50 |

50 |

| Upper |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

2000 |

2000 |

Table 9.

Statistical performance of b-AOA and original AOA for AVR system.

Table 9.

Statistical performance of b-AOA and original AOA for AVR system.

| Algorithm |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

Best |

Worst |

| b-AOA |

0.0065138 |

9.3497E−05 |

0.0063522 |

0.0067022 |

| AOA |

0.0078863 |

0.00012395 |

0.0076825 |

0.0081212 |

Table 10.

Optimal parameters of PIDND2N2 controller obtained via b-AOA and original AOA algorithms

Table 10.

Optimal parameters of PIDND2N2 controller obtained via b-AOA and original AOA algorithms

| Optimized by |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| b-AOA |

4.8723 |

2.0240 |

1.8094 |

0.15049 |

1595.2 |

1971.2 |

| AOA |

3.9448 |

2.1188 |

1.6757 |

0.13014 |

1544.2 |

871.72 |

Table 11.

Transient response performance metrics for b-AOA and AOA-tuned PIDND2N2 controllers.

Table 11.

Transient response performance metrics for b-AOA and AOA-tuned PIDND2N2 controllers.

| Design method |

Rise time (s) |

Settling time (s) |

Overshoot (%) |

| b-AOA-tuned PIDND2N2 |

0.033485 |

0.050752 |

0 |

| AOA-tuned PIDND2N2 |

0.037393 |

0.057523 |

0.043859 |

Table 12.

Frequency response performance metrics for b-AOA and AOA-tuned PIDND2N2 controllers.

Table 12.

Frequency response performance metrics for b-AOA and AOA-tuned PIDND2N2 controllers.

| Design method |

Phase margin (°) |

Gain margin (dB) |

Bandwidth (rad/s) |

| b-AOA-tuned PIDND2N2 |

70.797 |

28.888 |

64.820 |

| AOA-tuned PIDND2N2 |

69.810 |

23.368 |

57.819 |

Table 13.

Comparative numerical values for transient response of different control approaches.

Table 13.

Comparative numerical values for transient response of different control approaches.

| Design method |

Rise time (s) |

Settling time (s) |

Overshoot (%) |

| b-AOA-tuned PIDND2N2 |

0.033485 |

0.050752 |

0 |

| AOA-tuned PIDND2N2 |

0.037393 |

0.057523 |

0.043859 |

| SCA-tuned PID [23] |

0.1472 |

0.84133 |

11.425 |

| WOA-tuned PIDA [24] |

0.32772 |

0.49543 |

1.6483 |

| SMA-tuned FOPID [25] |

0.087541 |

0.4979 |

15.998 |

| PSO-tuned PIDD2 [26] |

0.092935 |

0.16347 |

0.0025797 |

Table 14.

Comparative numerical values for frequency response of different control approaches.

Table 14.

Comparative numerical values for frequency response of different control approaches.

| Design method |

Phase margin (°) |

Gain margin (dB) |

Bandwidth (rad/s) |

| b-AOA-tuned PIDND2N2

|

70.797 |

28.888 |

64.820 |

| AOA-tuned PIDND2N2

|

69.810 |

23.368 |

57.819 |

| SCA-tuned PID [33] |

52.596 |

20.300 |

14.821 |

| WOA-tuned PIDA [34] |

67.671 |

26.123 |

6.7076 |

| SMA-tuned FOPID [35] |

49.142 |

20.193 |

23.914 |

| PSO-tuned PIDD2 [36] |

79.638 |

Infinite |

23.503 |

Table 15.

Transient response performance of the proposed approach with respect to recently reported other efficient methods.

Table 15.

Transient response performance of the proposed approach with respect to recently reported other efficient methods.

| Ref. |

Year |

Used controller type |

Tuning method |

Rise time (s) |

Settling time (s) |

Overshoot (%) |

| Proposed |

PIDND2N2 |

b-AOA |

0.033485 |

0.050752 |

0 |

| [27] |

2023 |

FOPID |

MPA |

0.0833 |

0.1106 |

0.55 |

| [28] |

PID |

h-ASPSO |

0.3097 |

0.4679 |

1.2476 |

| [44] |

TIλDND2N2

|

EO |

0.03752 |

0.0596 |

0.4128 |

| [6] |

FOPIDD2

|

RSA |

0.0487 |

0.0806 |

0 |

| [29] |

2022 |

PIDND2N2

|

iRUN |

0.0399 |

0.0626 |

0 |

| [30] |

PID-F |

SOS |

0.267 |

0.371 |

0.007 |

| [31] |

2DOF fractional-order PI |

WOA |

1.12 |

1.74 |

1.17 |

| [32] |

PID |

L-RSANM |

0.3076 |

0.4669 |

0.9582 |

| [15] |

FOPID |

ChBWO |

0.1103 |

0.169 |

1.1838 |

| [33] |

Fuzzy PID |

GA |

0.1857 |

0.2963 |

1.0407 |

| [34] |

2021 |

FOPID with fractional filter |

SCA |

0.1230 |

0.1670 |

0.1262 |

| [35] |

PIDD2

|

SA-MRFO |

0.0535 |

0.0798 |

0.7562 |

| [14] |

PID |

SMA |

0.3149 |

0.4817 |

0.6071 |

| [36] |

FOPID |

GBO |

0.0885 |

0.653 |

11.3 |

| [37] |

Sigmoid PID |

NSCA |

0.498 |

0.579 |

2.2 |