1. Introduction

Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO) [

1] is a fascinating research field in which the ultimate goal consists of discovering solutions fulfilling multiple, often conflicting, objectives simultaneously [

1]. Since the task is extremely complex or even impossible, compromise solutions are taken into account, which are referred to as Pareto-optimal [

2]. By definition, a Pareto-optimal solution is “a set of ’non-inferior’ solutions in the objective space defining a boundary beyond which none of the objectives can be improved without sacrificing at least one of the other objectives” [

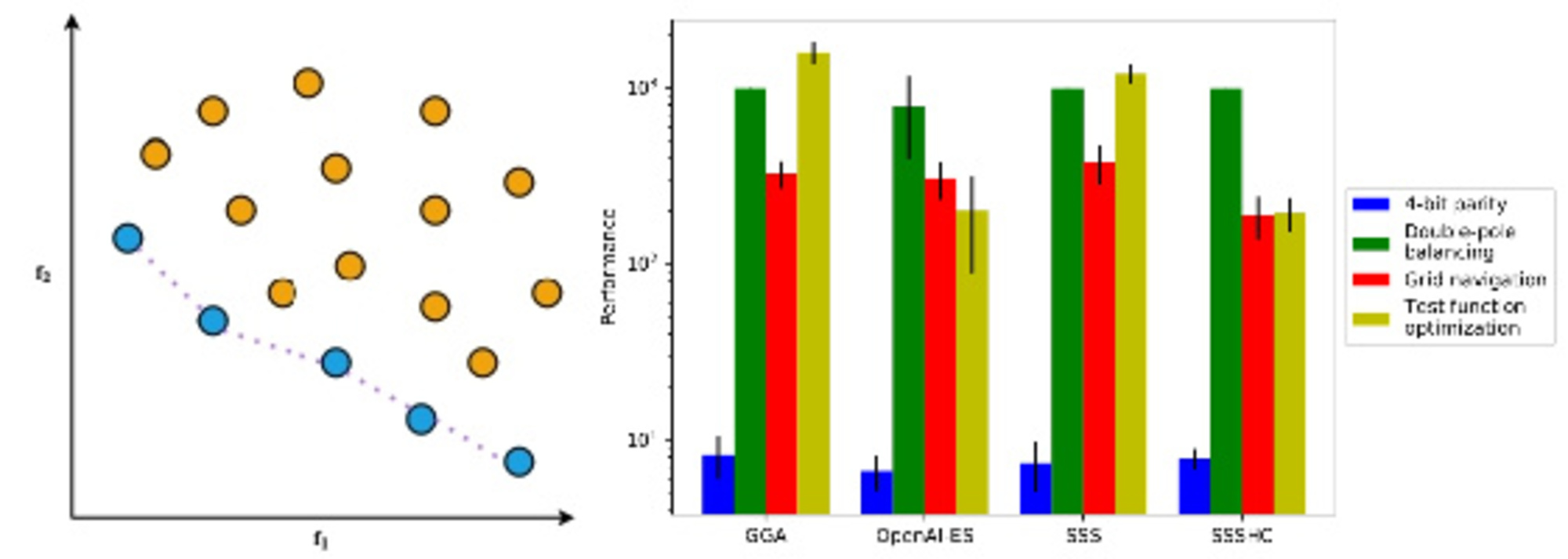

3]. An illustration of the concept of Pareto optimality is provided in

Figure 1.

Several techniques have been proposed to solve MOO problems, such as Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) [

4,

5,

6], Genetic Algorithms (GAs) [

7,

8,

9] or swarm intelligence approaches [

10,

11,

12]. For example, the authors in [

13] applied GAs to discover Pareto-optimal solutions for a Supply Chain Network (SCN) design problem. Their analysis indicates the feasibility of the approach in the context of a Turkish company producing plastic products. Applications of GAs to MOO of test functions can be found in [

14,

15,

16]. In [

17,

18], the OpenAI Evolutionary Strategy (OpenAI-ES) [

19] has been used to cope with a MOO problem requiring a swarm of AntBullet robots [

20] to simultaneously locomote and aggregate: the authors show that robots develop a good locomotion capability, while aggregation is obtained very rarely. This underscores the difficulty of optimizing both objectives at the same time.

Specific algorithms have been developed to address MOO with regard to test function optimization, such as Multi Objective Genetic Algorithm (MOGA) [

21], Niched Pareto Genetic Algorithm (NPGA) [

22], Nondominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) [

23] and Vector Evaluated Genetic Algorithm (VEGA) [

24]. In particular, NSGA-II [

23] enables to discover optimized solutions for test functions defined in [

24,

25] by exploiting non-dominated sorting, diversity-preservation and elitism combined with typical mutation and crossover operators from GAs. VEGA [

24] represents a variant of a classic GA tailored for MOO scenarios. Specifically, the solution evaluation produces a vector of fitness values, one for each objective, and selection is made by choosing non-dominated solutions according to Pareto optimality. To this end, the whole population is split into sub-populations (one for each objective) from which the best individuals are selected. Finally, recombination and mutation of selected solutions allow to generate the new population and ensure diversity.

An interesting field related to MOO involves the discovery of effective controllers to manage different problems belonging to the same class. For example, the authors in [

26] propose an approach called Shared Modular Policy (SMP) in which a global policy is used to control different modular neural networks. In particular, each module is responsible for the control of a single actuator based on current sensory readings and shared information in the form of current reward function. Experiments performed on robot locomotors characterized by diverse morphologies (e.g., Halfcheetah, Hopper, Humanoid, Walker2D) demonstrate the validity of the approach and a good generalization capability on new morphologies. Another worthwhile example can be found in [

27], in which the authors propose an approach to discover a single controller for a class of dynamical systems. Specifically, through in-context learning [

28], the authors demonstrate that an effective controller for a specific numerical problem can be immediately applied to a different problem within the same class, with no need for fine-tuning.

This work is halfway between MOO and the evolution of a single controller for multiple problems. In more detail, we present a comparative study of four EAs — Generational Genetic Algorithm (GGA) [

29], OpenAI-ES [

19], Stochastic Steady State [

30] and Stochastic Steady State with Hill-Climbing (SSSHC) [

31] — that must discover a single neural network controller capable to minimize simultaneously four benchmark problems: (i) 4-bit parity, (ii) double-pole balancing, (iii) grid navigation and (iv) test function optimization. Although using methods specifically tailored for MOO scenarios like NSGA-II or VEGA could be rather intuitive, we decided instead to put emphasis on the usage of general and relatively simple EAs [

32] to assess how effective they are at sampling the search space and discovering optimized solutions for the MOO scenario. Moreover, the considered algorithms proved successful with respect to the benchmark problems addressed in isolation [

30,

31,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Our results clearly demonstrate that OpenAI-ES and SSSHC outperform GGA and SSS thanks to their propensity to reduce the size of weights, which is pivotal in the considered scenario. Furthermore, detailed analysis of the performance on the individual benchmark problems reveal that all the algorithms focus mainly on the minimization of test functions, which allows to quickly optimize performance. Interestingly, SSSHC achieves better performance than OpenAI-ES with respect to grid navigation and test function optimization, while the opposite is true for 4-bit parity and double-pole balancing. This implies that relatively simple strategies can perform similarly to more sophisticated algorithms.

The key contributions of this research are listed as follows:

a new MOO scenario is introduced, which entails benchmark problems like 4-bit parity, double-pole balancing, grid navigation and test function optimization;

a comparison of some state-of-the-art EAs on the defined MOO scenario is proposed;

OpenAI-ES and SSSHC emerge as more effective than GGA and SSS at dealing with the novel MOO scenario;

SSSHC outperforms OpenAI-ES with respect to grid navigation and test function optimization, while the opposite is true for 4-bit parity and double-pole balancing;

OpenAI-ES has an intrinsic propensity to reduce the size of weights/parameters, which is paramount to discover effective solutions in the considered domain;

the definition of the MOO scenario highlights the existence of a non-negligible relationship between problems and algorithms.

The paper starts with a thorough description of the benchmark problems, the considered EAs, the neural network controller and the experimental settings in

Section 2. Then, a detailed illustration of the outcomes is provided in

Section 3, which are further discussed in

Section 4. Finally,

Section 5 reports the main findings and potential future research ideas.

3. Results

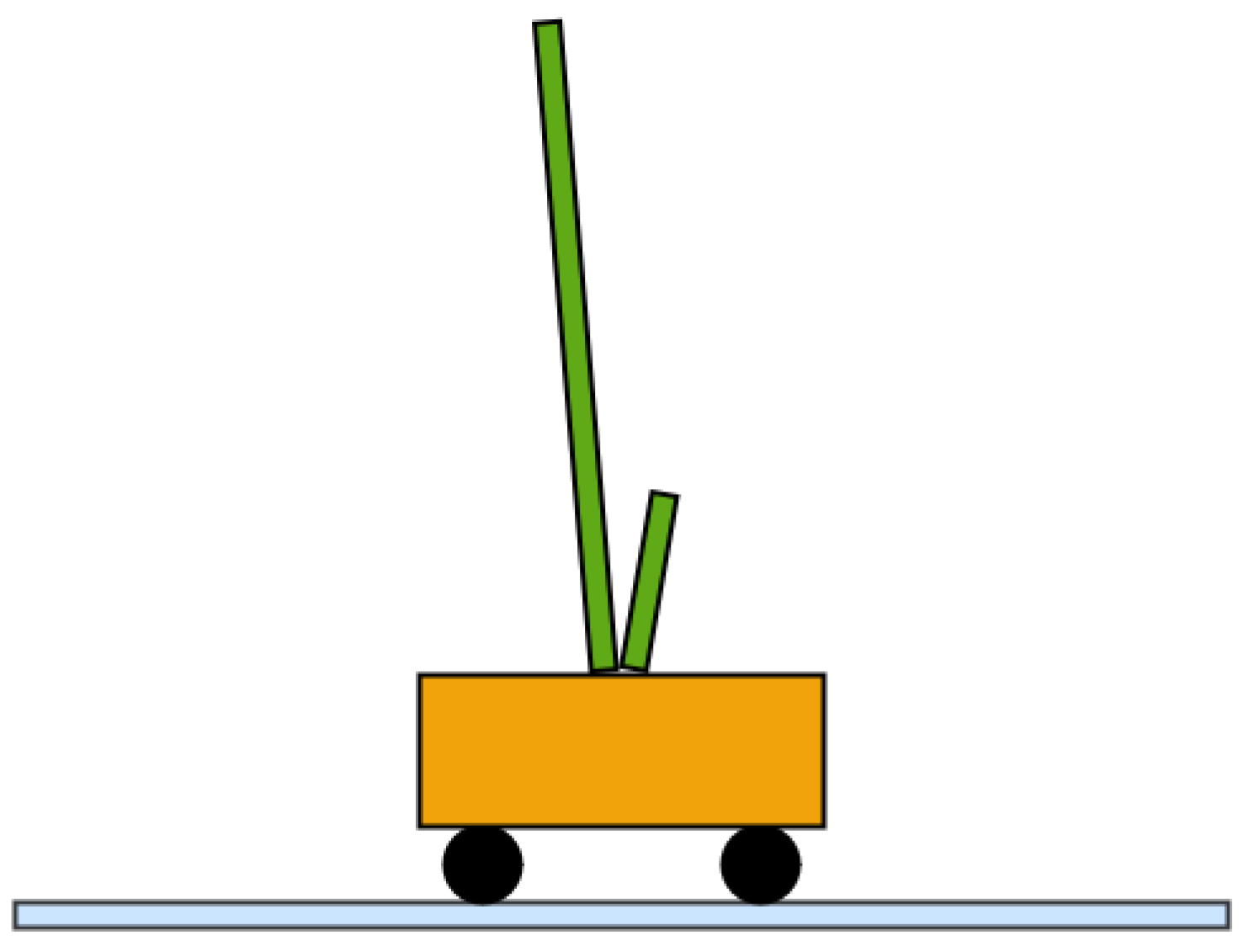

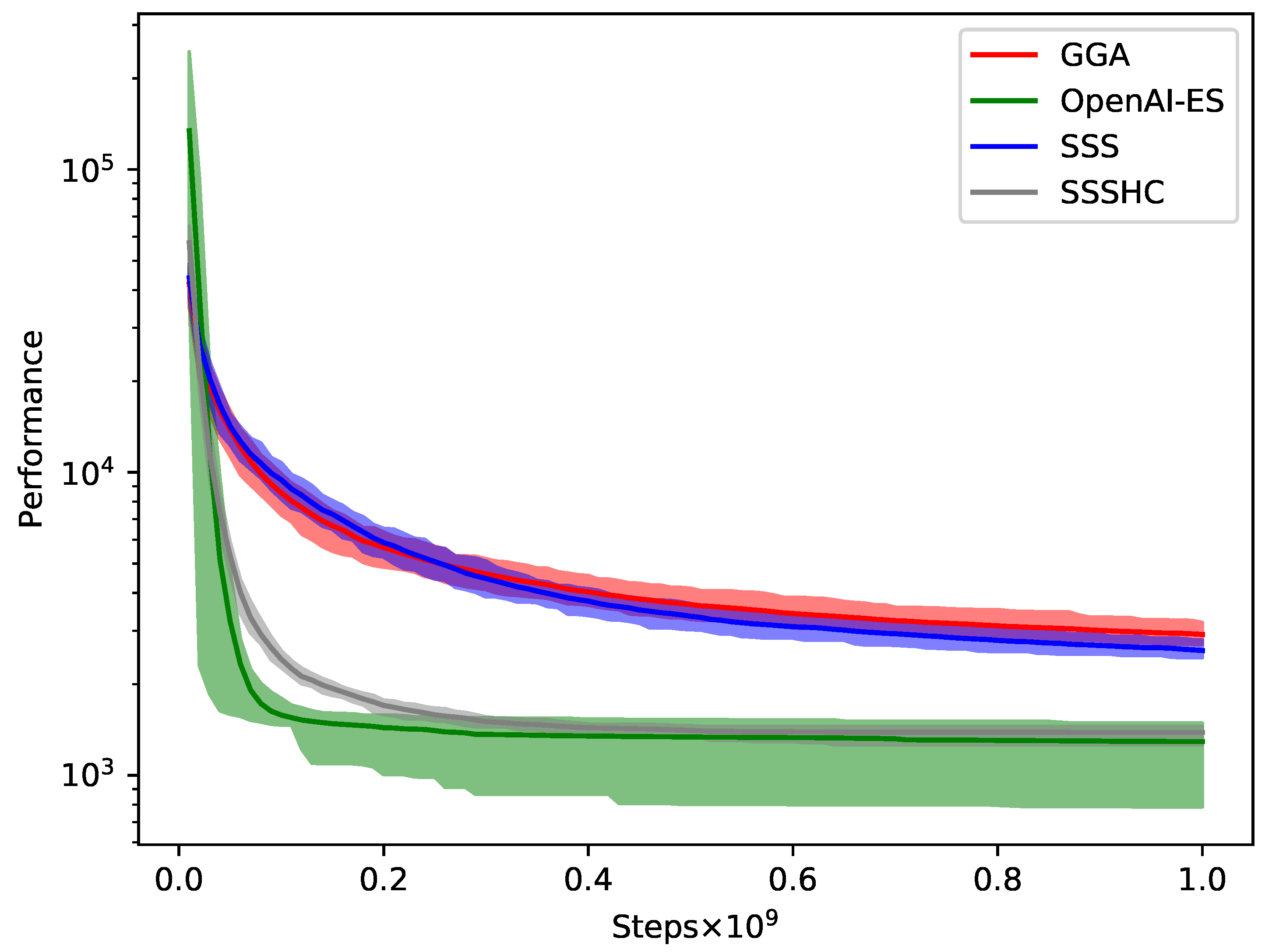

The performance comparison is shown in

Table 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. Clearly, OpenAI-ES and SSSHC strongly outperform GGA and SSS (Kruskal-Wallis H test,

, see

Table 6), which indicates their capability to discover more effective solutions for the considered MOO scenario. As can be seen in

Figure 6, OpenAI-ES and SSSHC quickly reduce the fitness in the first

evaluation steps and then almost stabilize after

evaluation steps. This implies that both algorithms manage to identify the direction in the search space corresponding to an optimized performance. Conversely, the fitness curves of GGA and SSS show a slower drop, which prevents them from further optimization.

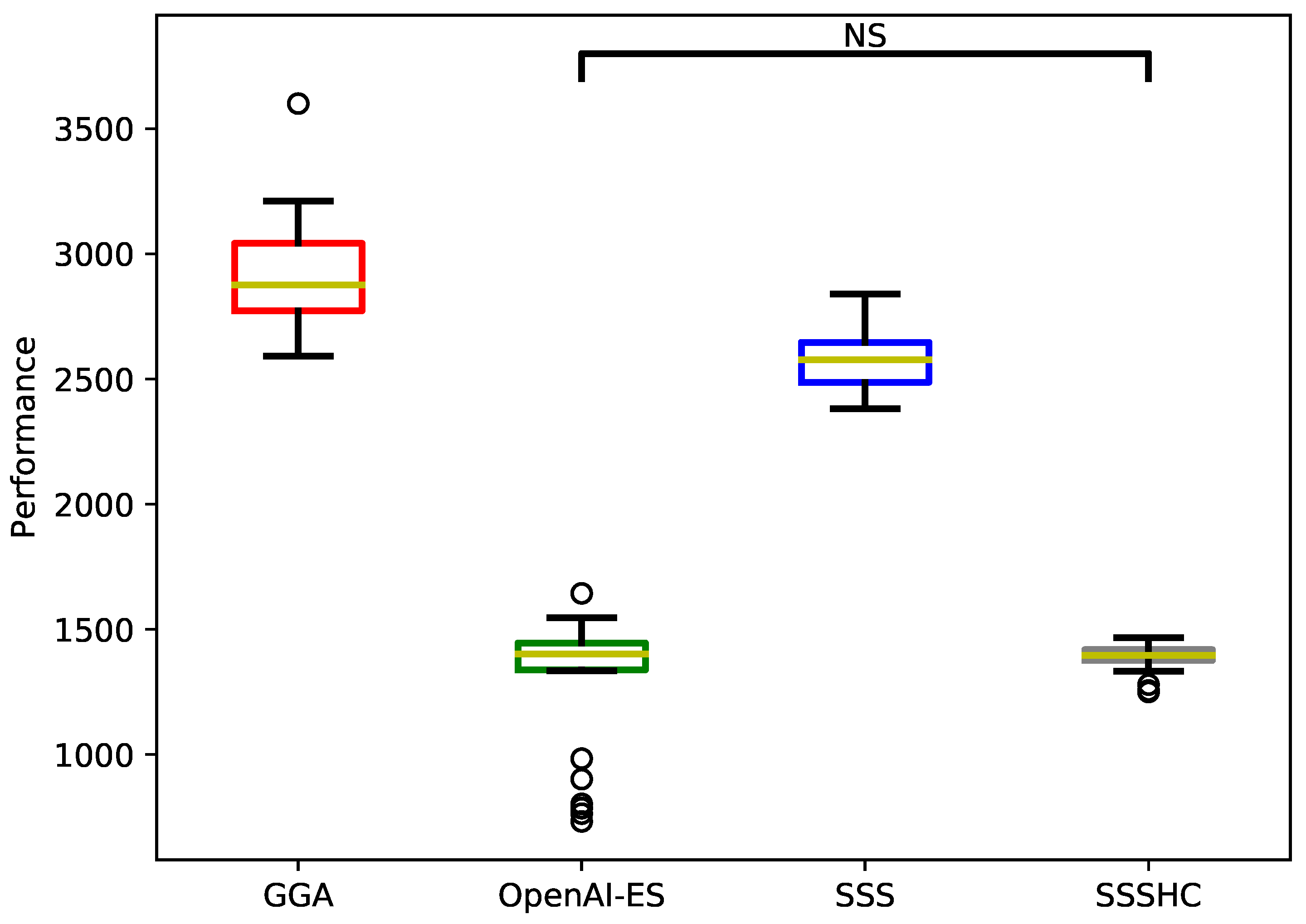

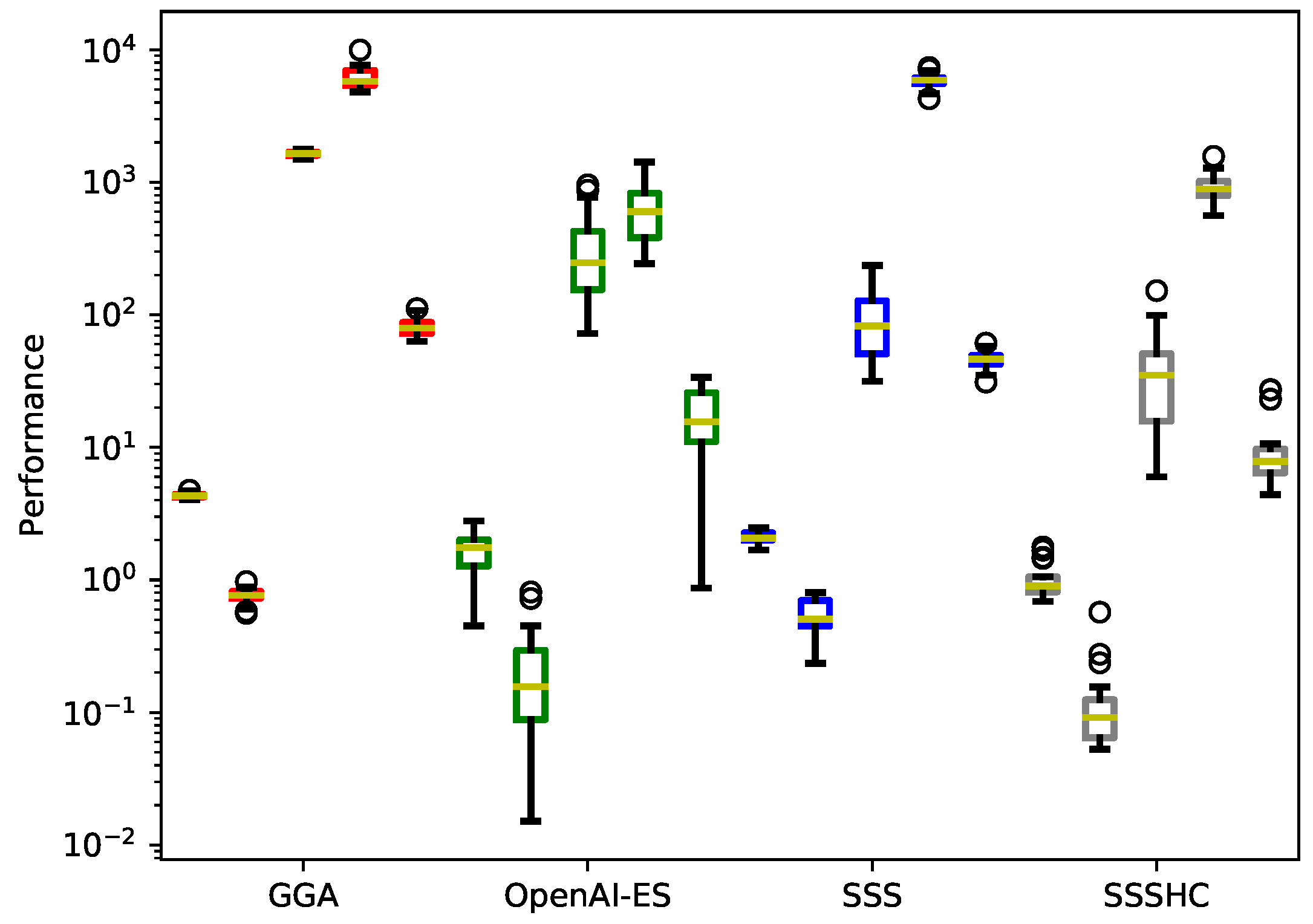

Notably, OpenAI-ES and SSSHC have similar performance (Mann-Whitney U test,

, see also

Figure 7 and

Table 6). Therefore, a relatively simple strategy like SSSHC is not inferior to a more sophisticated algorithm like OpenAI-ES, which exploits historical information to channel the search in the space of possible solutions. By looking at the outcomes reported in

Figure 7, OpenAI-ES manages to find solutions with performance below 1000 (see bottom outliers in

Figure 7), while SSSHC does not reach similar performance levels.

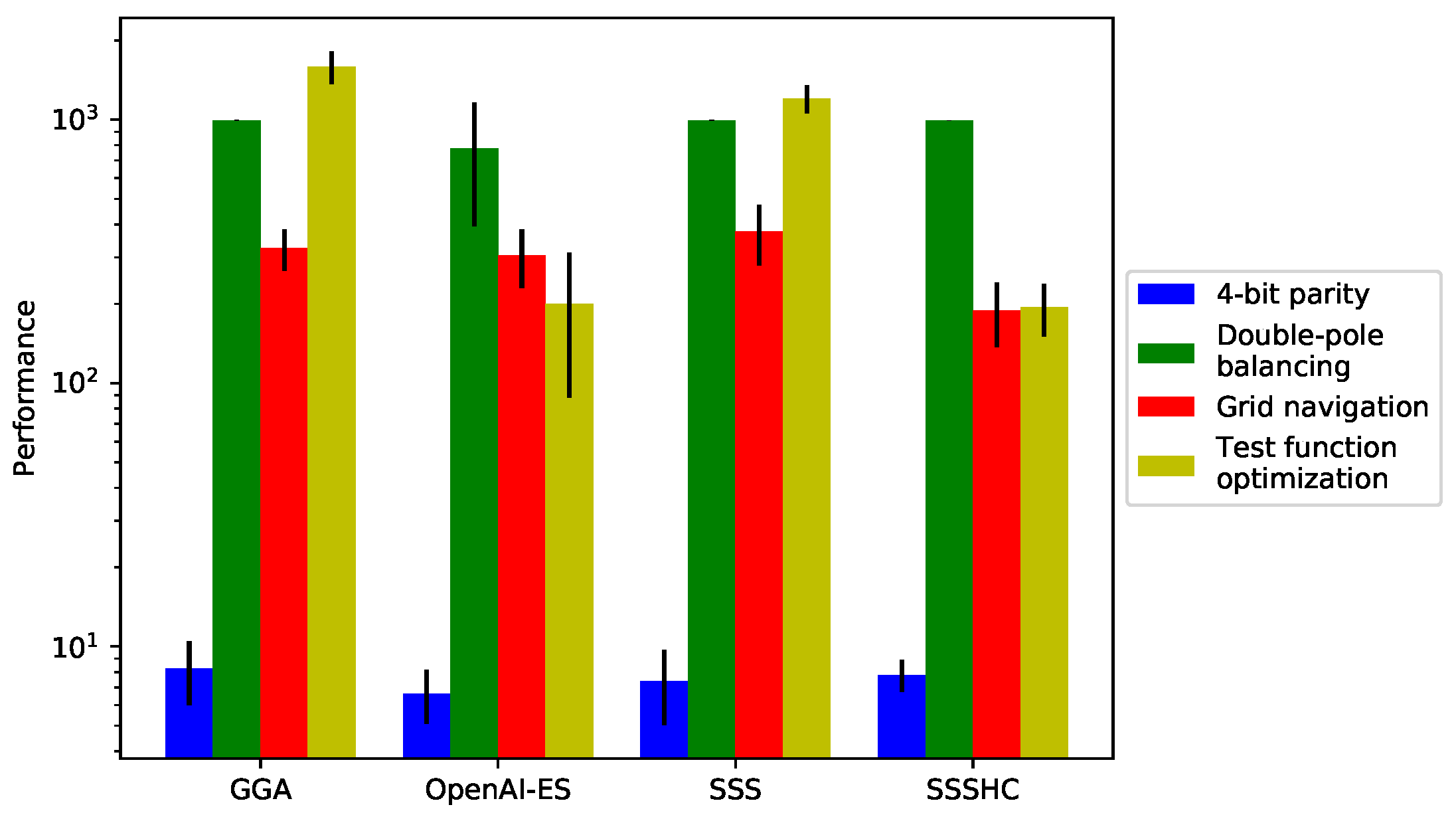

We corroborate our results by delving into the fitness achieved by the different algorithms with regard to the specific problems. As highlighted in

Figure 8 and

Table 7, OpenAI-ES achieves the best results in the 4-bit parity and double-pole balancing problems, while SSSHC bests other algorithms with respect to grid navigation and test function optimization. In particular, OpenAI-ES and SSSHC succeed in the minimization of test functions, which allows to quickly reduce fitness (see also

Figure 6). Instead, GGA and SSS fail in finding similar solutions. Furthermore, SSSHC is notably superior to the other algorithms in the grid navigation problem (Kruskal-Wallis H test,

). Interestingly, OpenAI-ES is the only algorithm that manages to discover improved solutions in the double-pole balancing problem (Kruskal-Wallis H test,

, see also

Figure 8 and

Table 7).

Lastly, we investigate the performance of the different algorithms with respect to Ackley, Griewank, Rastrigin, Rosenbrock and Sphere functions, as illustrated in

Figure 9 and

Table 8. Notably, OpenAI-ES is more effective than other algorithms in optimizing the Rosenbrock function (Kruskal-Wallis H test,

), whereas SSSHC bests other algorithms with respect to the remaining four test functions (Kruskal-Wallis H test,

). GGA and SSS achieve poor performance in this context, particularly concerning the Rosenbrock function (see

Table 8).

Overall, the reported analysis clearly reveals a superior performance of OpenAI-ES and SSSHC over GGA and SSS. This is related to their capability to decrease weights, as shown in

Table 9. In particular, the former algorithms evolve controllers with a limited weight size, which is paramount for the test function optimization. Nevertheless, this tendency prevents the algorithms from finding effective solutions with respect to the other problems, particularly double-pole balancing. This is especially true for SSSHC (see

Figure 8 and

Table 7). OpenAI-ES and SSS have similar weight sizes, but their performance is notably different. This can be explained by considering that OpenAI-ES exploits historical information to effectively sample the search space, while SSS does not adopt similar mechanisms.

4. Discussion

The presented results show that two algorithms emerge as more suitable options for the considered MOO scenario. A noteworthy aspect regards the different level of complexity between OpenAI-ES and SSSHC. In fact, the former method exploits mirrored sampling [

96] and historical information to identify the search direction in the space of solutions. Conversely, SSSHC is a memetic algorithm that seeks to refine selected solutions through single gene mutations. Despite the simplicity, SSSHC works well in this scenario. However, the approach presents benefits and drawbacks: on one hand, modifying one gene at a time eliminates the risk of disruptive effects, since only adaptive mutations are retained. On the other hand, the process does not exclude failures in the attempt of improving solution performance and is costly in terms of number of evaluation steps.

OpenAI-ES has an intrinsic propensity to reduce the size of weights even when weight decay is not applied, as in the case of our experiments. This turns out to be crucial in the considered domain, as well as in other domains like robot locomotion [

33] and swarm robotics [

80]. Conversely, SSSHC exploits single gene mutations performed during refinement to progressively reduce the weight size.

GGA and SSS do not manage to achieve performance comparable to the other algorithms. Specifically, they fail in discovering effective solutions for test function optimization, particularly with respect to the Rosenbrock function. This can be explained by considering that both GGA and SSS seek to enhance performance through mutation and crossover operators, and do not have explicit techniques to reduce weights. As a consequence, they might require longer evolutionary processes in order to find more effective solutions.

Another relevant insight concerns the types of solutions discovered by the considered EAs. In particular, we observe that all the algorithms mainly focus on test function optimization, which allows to quickly enhance performance, and almost ignore the remaining problems. This is strongly related to the remarkable different magnitudes of the fitness values in the worst case (see

Table 10): because test function optimization is three order of magnitude bigger than double-pole balancing and grid navigation, the fitness function defined in Eq.

12 is minimized when the component

is strongly reduced. As a consequence, the algorithms evolve solutions mostly addressing test function optimization and do not manage to improve performance with respect to the other objectives.

Overall, our results underscore a non-negligible relationship between problem and algorithm. In fact, although OpenAI-ES, SSS and SSSHC proved effective at optimizing double-pole balancing in previous studies [

30,

31,

33,

35], the definition of the performance measure for the considered MOO scenario guides EAs to different evolutionary paths, in which one of the objectives dominate the others.

5. Conclusions

Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO) concerns the identification of solutions capable of optimizing multiple conflicting objectives at the same time. Because the discovery of a global optimum is not trivial, if not impossible, Pareto-optimal solutions are typically taken into account. Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) have demonstrated a great ability to deal with MOO scenarios, since they provide effective solutions without any prior knowledge about the considered domains. A partially related research field lies in the search for a single controller able to address different problems within the same class. The main advantage is the possibility of transferring acquired knowledge on a given problem to others, without further fine-tuning. The approach is similar to transfer learning [

97], which proved valuable in Deep Learning (DL) applications [

98,

99,

100].

This work delves into the definition of a novel MOO scenario and the analysis of how some state-of-the-art works address it. Specifically, we compared GGA, OpenAI-ES, SSS and SSSHC with respect to the evolution of a single neural network controller able to simultaneously optimize four benchmark problems: (i) 4-bit parity, (ii) double-pole balancing, (iii) grid navigation, and (iv) test function optimization. The definition of the scenario makes the overall problem challenging, since the multiple objectives conflict with each other. Furthermore, the controller is used differently depending on the specific problem: for example, the connection weights determine the action to be executed in the double-pole balancing or grid navigation problems, while they represent the input vector for the test functions to be optimized. Outcomes indicate that OpenAI-ES and SSSHC best the other algorithms, since they are more effective at sampling the search space. In particular, OpenAI-ES exploits symmetric sampling and historical information, whereas SSSHC benefits from single-gene mutations. Interestingly, a relatively trivial algorithm like SSSHC is not inferior to a modern and sophisticated method like OpenAI-ES in this context. Instead, SSSHC is better than OpenAI-ES with respect to grid navigation and test function optimization, while the opposite is true for 4-bit parity and double-pole balancing. In addition, OpenAI-ES and SSSHC manage to reduce weight size more efficiently than GGA and SSS, a worthwhile feature in the considered domain.

As future research directions, we plan to incorporate algorithms specifically tailored for MOO domains, such as NSGA-II and VEGA, for future comparisons. This will provide a comprehensive analysis of the most suitable methods for MOO. Furthermore, modifications of the problem formulation in Eq.

12 will be object of future studies, particularly through either the usage of different coefficient values for the different objectives, or the normalization of the fitness functions defined in Eqs.

1,

2,

3 and

10. In addition, further experiments in which parameter settings are systematically varied will be performed, aiming to validate our analysis more thoroughly. Finally, future works could investigate different scenarios (e.g., robotics, classic control) in order to extend and, possibly, generalize the considerations reported here.

Figure 1.

Explanation of Pareto optimality in a two-objective optimization (e.g., functions and ) scenario: non-dominated solutions (blue circles) are Pareto-optimal and lie on the so-called Pareto front (purple dotted curve). Remaining solutions (orange circles) are dominated by those belonging to the Pareto front.

Figure 1.

Explanation of Pareto optimality in a two-objective optimization (e.g., functions and ) scenario: non-dominated solutions (blue circles) are Pareto-optimal and lie on the so-called Pareto front (purple dotted curve). Remaining solutions (orange circles) are dominated by those belonging to the Pareto front.

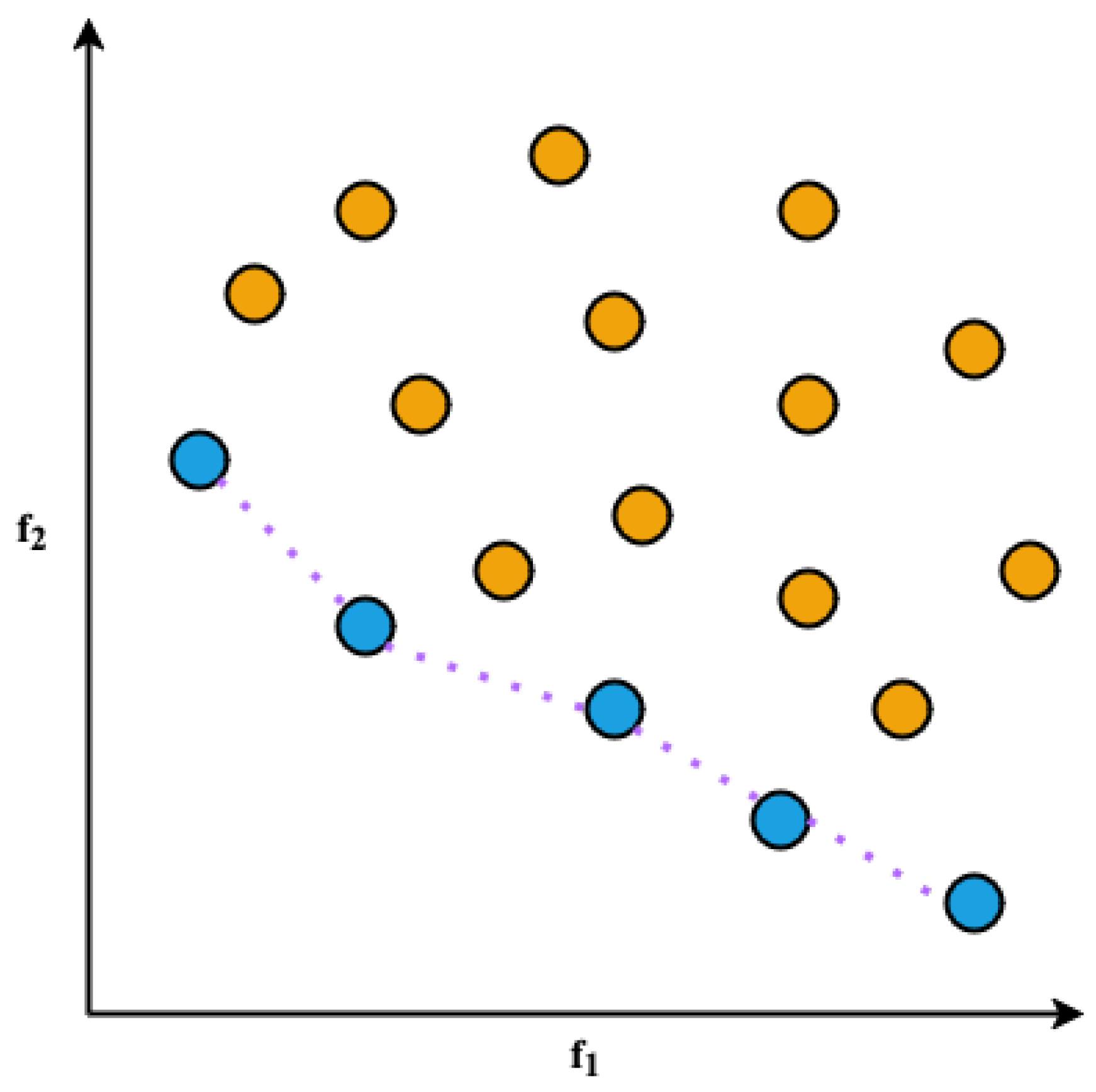

Figure 2.

Illustration of the 4-bit parity problem: given a 4-bit input string, the goal is to return 1/0 when the number of 1-bits is even/odd. It is worth noting that the parity value for a sequence made of 0-bits only is 1.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the 4-bit parity problem: given a 4-bit input string, the goal is to return 1/0 when the number of 1-bits is even/odd. It is worth noting that the parity value for a sequence made of 0-bits only is 1.

Figure 3.

Double-pole balancing problem: two poles are placed (green rectangles) are placed on the top of wheeled mobile cart (orange rectangle), which can move on a horizontal surface (light blue rectangle).

Figure 3.

Double-pole balancing problem: two poles are placed (green rectangles) are placed on the top of wheeled mobile cart (orange rectangle), which can move on a horizontal surface (light blue rectangle).

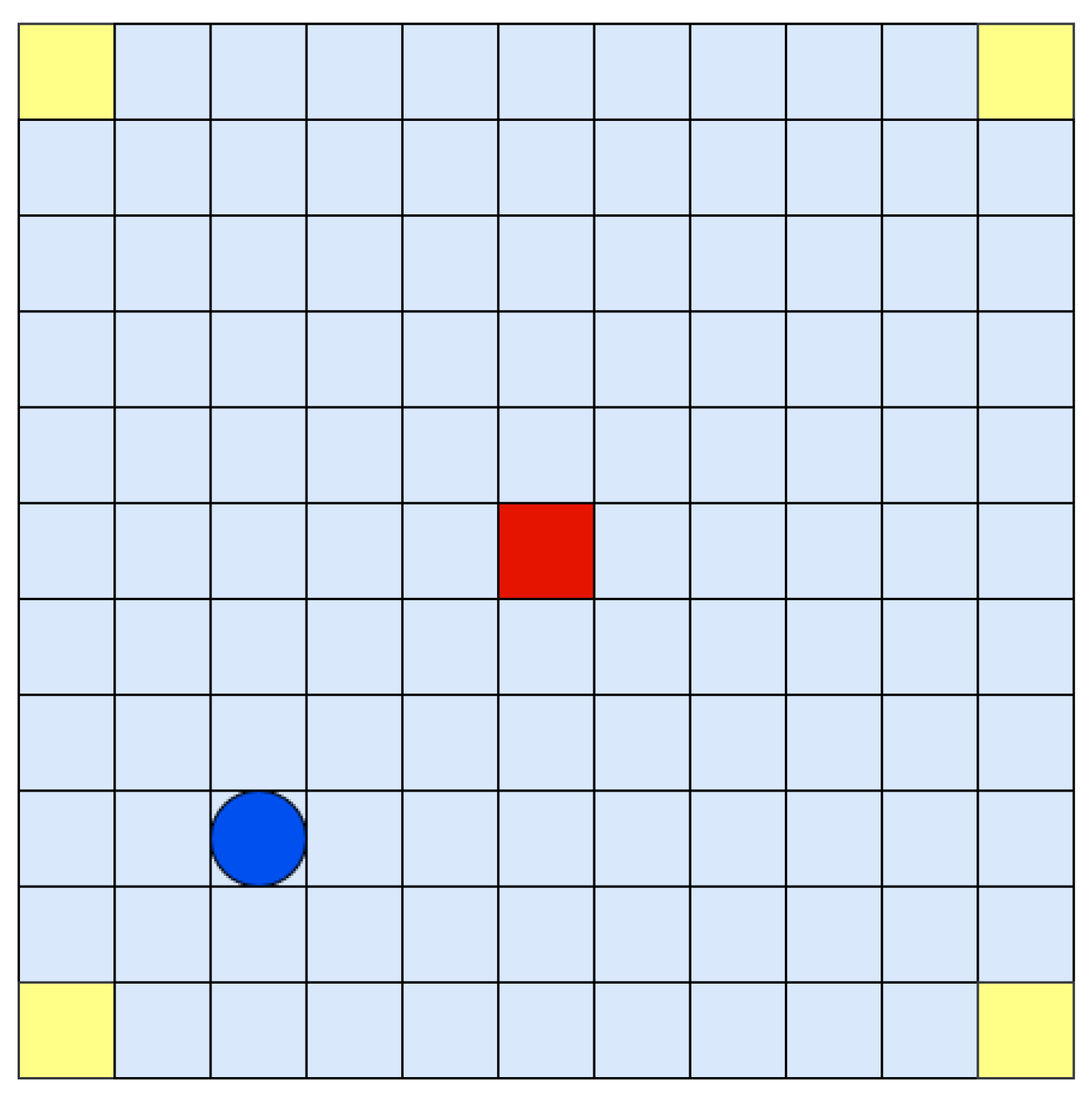

Figure 4.

Grid navigation problem: an agent (red circle) has to navigate in a grid world. The agent starts from one of four possible initial locations (yellow squares) and its goal is to reach the target location (red square). The agent can move left, up, right or bottom.

Figure 4.

Grid navigation problem: an agent (red circle) has to navigate in a grid world. The agent starts from one of four possible initial locations (yellow squares) and its goal is to reach the target location (red square). The agent can move left, up, right or bottom.

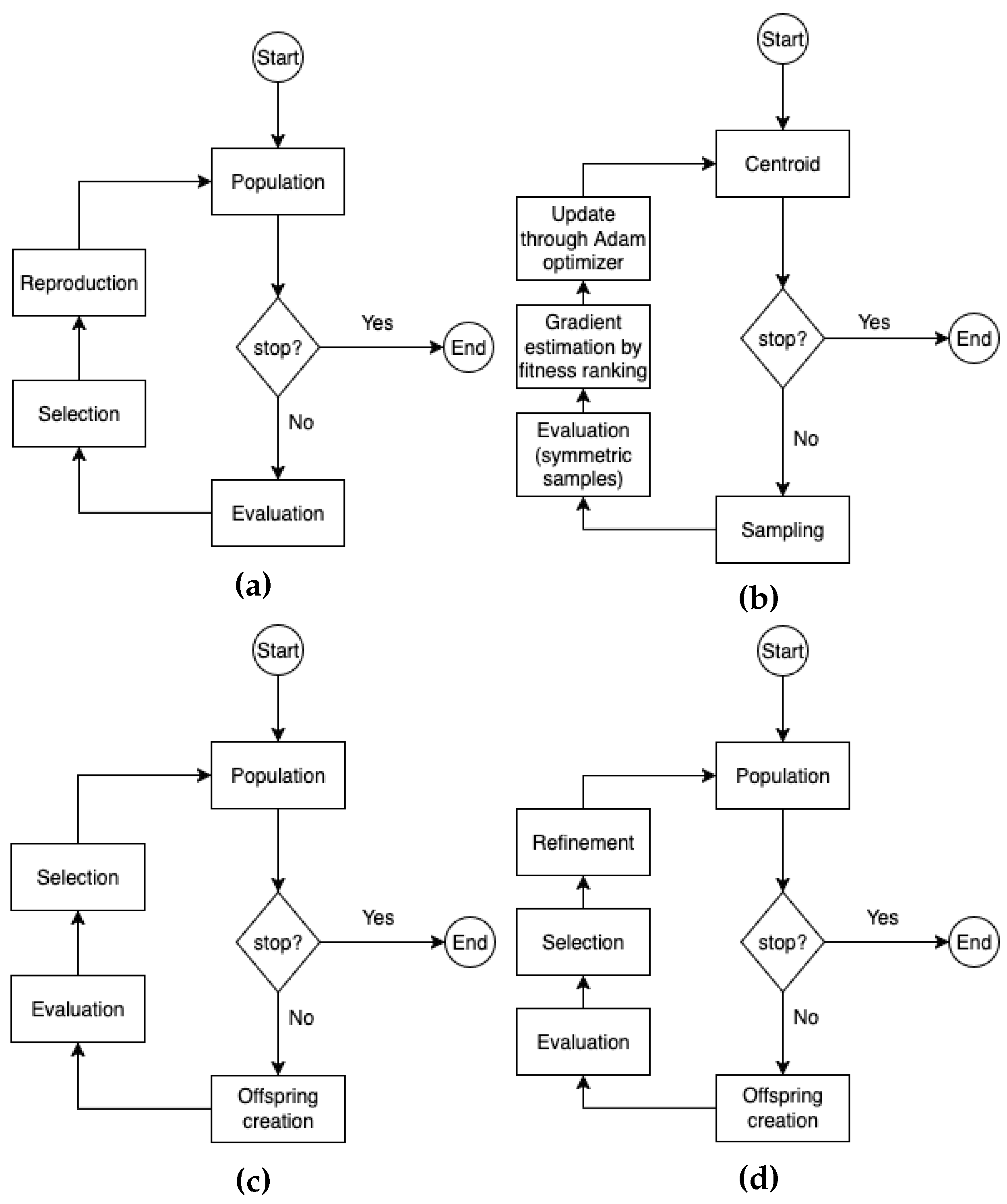

Figure 5.

Schematic of the considered EAs. (a) GGA; (b) OpenAI-ES; (c) SSS; (d) SSSHC.

Figure 5.

Schematic of the considered EAs. (a) GGA; (b) OpenAI-ES; (c) SSS; (d) SSSHC.

Figure 6.

Performance of GGA, OpenAI-ES, SSS and SSSHC during evolution. The shaded areas are bounded in the range (first and third quartiles of data). We use the logarithmic scale on the y-axis to improve readability. Fitness is averaged over 30 replications.

Figure 6.

Performance of GGA, OpenAI-ES, SSS and SSSHC during evolution. The shaded areas are bounded in the range (first and third quartiles of data). We use the logarithmic scale on the y-axis to improve readability. Fitness is averaged over 30 replications.

Figure 7.

Final performance achieved by the different methods (see

Table 5). Boxes are bounded in the range

, with the whiskers extending to data within

. Medians are indicated with yellow lines. The notation

indicates that the fitness values of the two considered methods do not statistically differ (Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction,

, see also

Table 6).

Figure 7.

Final performance achieved by the different methods (see

Table 5). Boxes are bounded in the range

, with the whiskers extending to data within

. Medians are indicated with yellow lines. The notation

indicates that the fitness values of the two considered methods do not statistically differ (Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction,

, see also

Table 6).

Figure 8.

Analysis of the algorithm performance on the different problems. Black lines mark the standard deviations. We use the logarithmic scale on the y-axis to improve readability. Bars denote the average fitness from 30 replications.

Figure 8.

Analysis of the algorithm performance on the different problems. Black lines mark the standard deviations. We use the logarithmic scale on the y-axis to improve readability. Bars denote the average fitness from 30 replications.

Figure 9.

Algorithm performance on the Ackley, Griewank, Rastrigin, Rosenbrock and Sphere test functions. Boxes are bounded in the range , with the whiskers extending to data within . Medians are indicated with yellow lines. We use the logarithmic scale on the y-axis to improve readability. Data represents the average fitness from 30 replications.

Figure 9.

Algorithm performance on the Ackley, Griewank, Rastrigin, Rosenbrock and Sphere test functions. Boxes are bounded in the range , with the whiskers extending to data within . Medians are indicated with yellow lines. We use the logarithmic scale on the y-axis to improve readability. Data represents the average fitness from 30 replications.

Table 1.

Parameters characterizing the double-pole balancing problem. The track extremes are placed at -2.4 m and 2.4 m, respectively. We denote the absence of information with the symbol “-”.

Table 1.

Parameters characterizing the double-pole balancing problem. The track extremes are placed at -2.4 m and 2.4 m, respectively. We denote the absence of information with the symbol “-”.

| Parameter |

Length |

Mass |

| Track |

4.8 m |

- |

| Cart |

- |

1.0 kg |

| Long pole |

1.0 m |

0.5 kg |

| Short pole |

0.1 m |

0.05 kg |

Table 2.

Initialization of the state variables in each trial of the double-pole balancing problem.

Table 2.

Initialization of the state variables in each trial of the double-pole balancing problem.

|

x |

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

-1.944 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2 |

1.944 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 3 |

0 |

-1.215 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 4 |

0 |

1.215 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 5 |

0 |

0 |

-0.10472 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 6 |

0 |

0 |

0.10472 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

-0.135088 |

0 |

0 |

| 8 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.135088 |

0 |

0 |

Table 3.

Encoding of the input () and output () neurons used for 4-bit parity, double-pole balancing and grid navigation problems. Symbols are defined as follows: concerning 4-bit parity, (with ) states for the generic bit of the input string, whereas indicates the network output used to check parity. As regards double-pole balancing, x refers to the cart position, and denote the angle of the long and short poles, respectively, and is a flag indicating whether the trial might prematurely be stopped because either the cart is going out of the track () or the pole angles are above , while is the force applied to the cart that determines its motion. Lastly, with respect to grid navigation, the symbols and represent, respectively, the position of the agent and of the target locations, is the grid size and is the direction of the agent in the grid (with ).

Table 3.

Encoding of the input () and output () neurons used for 4-bit parity, double-pole balancing and grid navigation problems. Symbols are defined as follows: concerning 4-bit parity, (with ) states for the generic bit of the input string, whereas indicates the network output used to check parity. As regards double-pole balancing, x refers to the cart position, and denote the angle of the long and short poles, respectively, and is a flag indicating whether the trial might prematurely be stopped because either the cart is going out of the track () or the pole angles are above , while is the force applied to the cart that determines its motion. Lastly, with respect to grid navigation, the symbols and represent, respectively, the position of the agent and of the target locations, is the grid size and is the direction of the agent in the grid (with ).

| Problem |

|

|

|

|

|

| 4-bit parity |

|

|

|

|

|

| Double-pole balancing |

|

|

|

alert |

|

| Grid navigation |

|

|

|

|

|

Table 4.

List of parameter settings used for the different algorithms. Symbol refers to the number of replications, indicates the number of evaluation steps (i.e., the length of evolution), denotes the number of solutions forming the population. Concerning GGA, and represent, respectively, the number of reproducing solutions (i.e., the ones that have been selected) and the number offspring generated by each selected solution. The symbol is the mutation rate (i.e., the probability to modify one gene), while refers to the probability of performing (asexual) crossover. With respect to OpenAI-ES, denotes the learning rate and is the number of samples extracted from the Gaussian distribution. The symbol indicates the number of refinement iterations performed by SSSHC. Lastly, the symbol refers to the range of connection weights.

Table 4.

List of parameter settings used for the different algorithms. Symbol refers to the number of replications, indicates the number of evaluation steps (i.e., the length of evolution), denotes the number of solutions forming the population. Concerning GGA, and represent, respectively, the number of reproducing solutions (i.e., the ones that have been selected) and the number offspring generated by each selected solution. The symbol is the mutation rate (i.e., the probability to modify one gene), while refers to the probability of performing (asexual) crossover. With respect to OpenAI-ES, denotes the learning rate and is the number of samples extracted from the Gaussian distribution. The symbol indicates the number of refinement iterations performed by SSSHC. Lastly, the symbol refers to the range of connection weights.

| Parameter |

GGA |

OpenAI-ES |

SSS |

SSSHC |

|

30 |

|

|

|

100 |

1 |

50 |

50 |

|

10 |

- |

|

|

- |

|

Yes |

- |

Yes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

|

|

- |

|

- |

|

- |

20 |

- |

|

- |

5 |

|

|

Table 5.

Fitness analysis of the different algorithms. Data is the average of 30 replications of the experiments. Best performance is reported in bold.

Table 5.

Fitness analysis of the different algorithms. Data is the average of 30 replications of the experiments. Best performance is reported in bold.

| GGA |

OpenAI-ES |

SSS |

SSSHC |

| 2915.823 [206.120] |

1291.433 [268.231] |

2581.040 [117.146] |

1384.418 [57.312] |

Table 6.

Statistical comparison between the considered methods according to the Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction, with significant differences indicated in bold. Table is symmetrical with respect to the main diagonal. The symbol “-” marks the absence of the corresponding entry. Data is the average of 30 replications of the experiments.

Table 6.

Statistical comparison between the considered methods according to the Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction, with significant differences indicated in bold. Table is symmetrical with respect to the main diagonal. The symbol “-” marks the absence of the corresponding entry. Data is the average of 30 replications of the experiments.

| |

GGA |

OpenAI-ES |

SSS |

SSSHC |

| GGA |

- |

|

|

|

| OpenAI-ES |

|

- |

|

|

| SSS |

|

|

- |

|

| SSSHC |

|

|

|

- |

Table 7.

Analysis of the performance collected by the different algorithms with regard to 4-bit parity, double-pole balancing, grid navigation and test function optimization. Bold values correspond to the best outcomes. Data is the average of 30 replications of the experiments.

Table 7.

Analysis of the performance collected by the different algorithms with regard to 4-bit parity, double-pole balancing, grid navigation and test function optimization. Bold values correspond to the best outcomes. Data is the average of 30 replications of the experiments.

| Problem |

GGA |

OpenAI-ES |

SSS |

SSSHC |

| 4-bit parity |

8.233 [2.246] |

6.633 [1.538] |

7.367 [2.331] |

7.800 [1.078] |

| Double-pole balancing |

994.654 [2.199] |

778.279 [384.148] |

993.708 [2.394] |

993.725 [1.601] |

| Grid navigation |

325.167 [57.660] |

306.142 [75.842] |

377.092 [97.762] |

188.908 [51.606] |

| Test function optimization |

1587.770 [223.944] |

200.379 [111.980] |

1202.873 [147.151] |

193.986 [43.340] |

Table 8.

Analysis of the performance collected by the different algorithms with regard to the Ackley, Griewank, Rastrigin, Rosenbrock and Sphere test functions. Last row reports the average fitness and the standard deviation. Bold values correspond to the best outcomes. Data is the average of 30 replications of the experiments.

Table 8.

Analysis of the performance collected by the different algorithms with regard to the Ackley, Griewank, Rastrigin, Rosenbrock and Sphere test functions. Last row reports the average fitness and the standard deviation. Bold values correspond to the best outcomes. Data is the average of 30 replications of the experiments.

| Test function |

GGA |

OpenAI-ES |

SSS |

SSSHC |

| Ackley |

4.331 [0.179] |

1.673 [0.586] |

2.107 [0.184] |

0.994 [0.282] |

| Griewank |

0.765 [0.094] |

0.217 [0.193] |

0.546 [0.146] |

0.120 [0.098] |

| Rastrigin |

1643.956 [66.687] |

332.113 [245.317] |

97.339 [53.305] |

39.996 [32.509] |

| Rosenbrock |

6207.401 [1112.739] |

650.228 [317.946] |

5868.017 [702.571] |

918.511 [209.908] |

| Sphere |

82.393 [12.567] |

17.665 [9.097] |

46.356 [6.654] |

10.307 [6.656] |

| Average |

1587.769 [2444.544] |

200.379 [314.326] |

1202.873 [2354.027] |

193.985 [374.800] |

Table 9.

Analysis of the weight size of the controllers evolved with the different EAs. Data is the average of 30 replications of the experiments.

Table 9.

Analysis of the weight size of the controllers evolved with the different EAs. Data is the average of 30 replications of the experiments.

| GGA |

OpenAI-ES |

SSS |

SSSHC |

| 0.316 [0.047] |

0.083 [0.045] |

0.124 [0.045] |

0.018 [0.015] |

Table 10.

Worst fitness value that can be obtained in each considered problem.

Table 10.

Worst fitness value that can be obtained in each considered problem.

| 4-bit parity |

Double-pole balancing |

Grid navigation |

Test function optimization |

| 16 |

1000 |

500 |

6450690.655 |