Submitted:

06 November 2023

Posted:

07 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

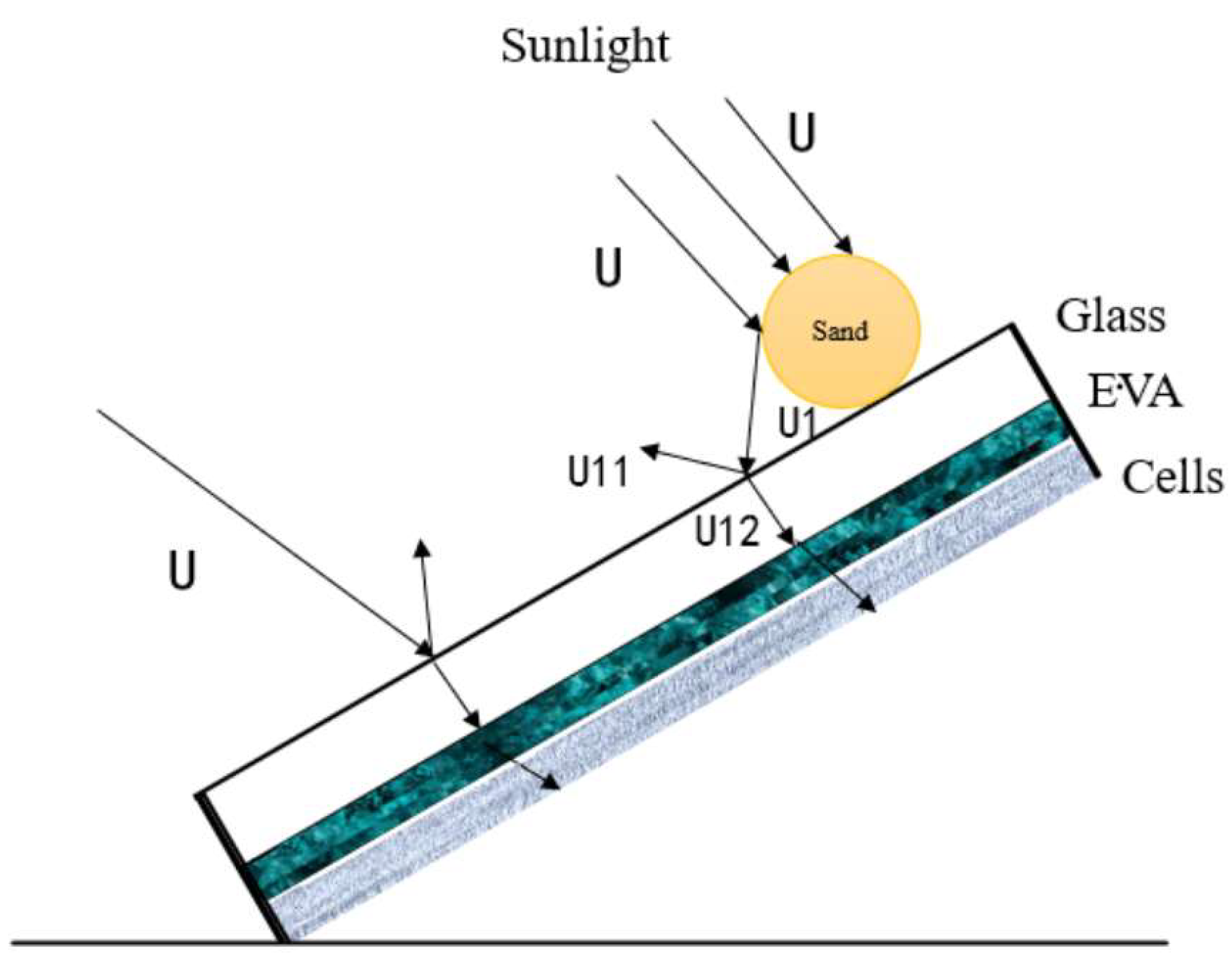

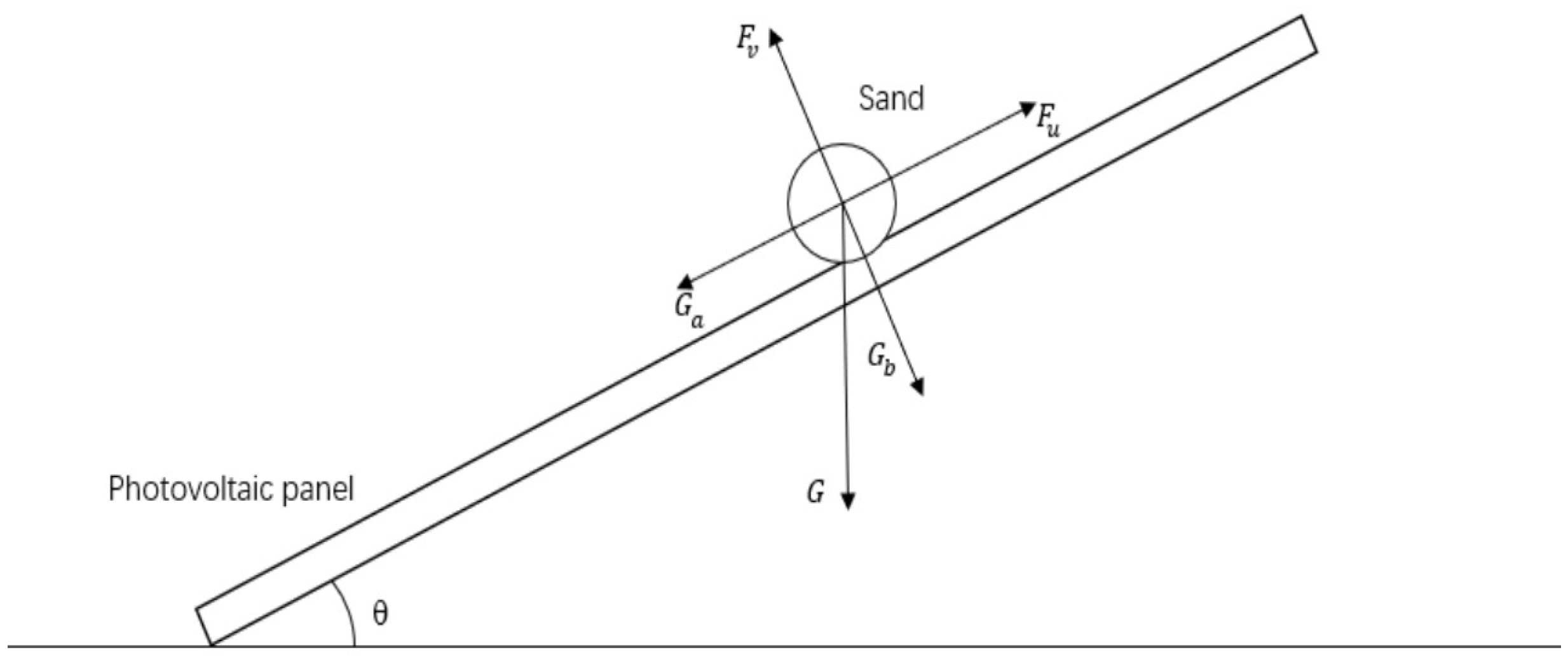

2. Model Formulation and Boundary Conditions

3. Experimental Tests

3.1. Experimental Setup

3.2. Analysis of Experimental Results

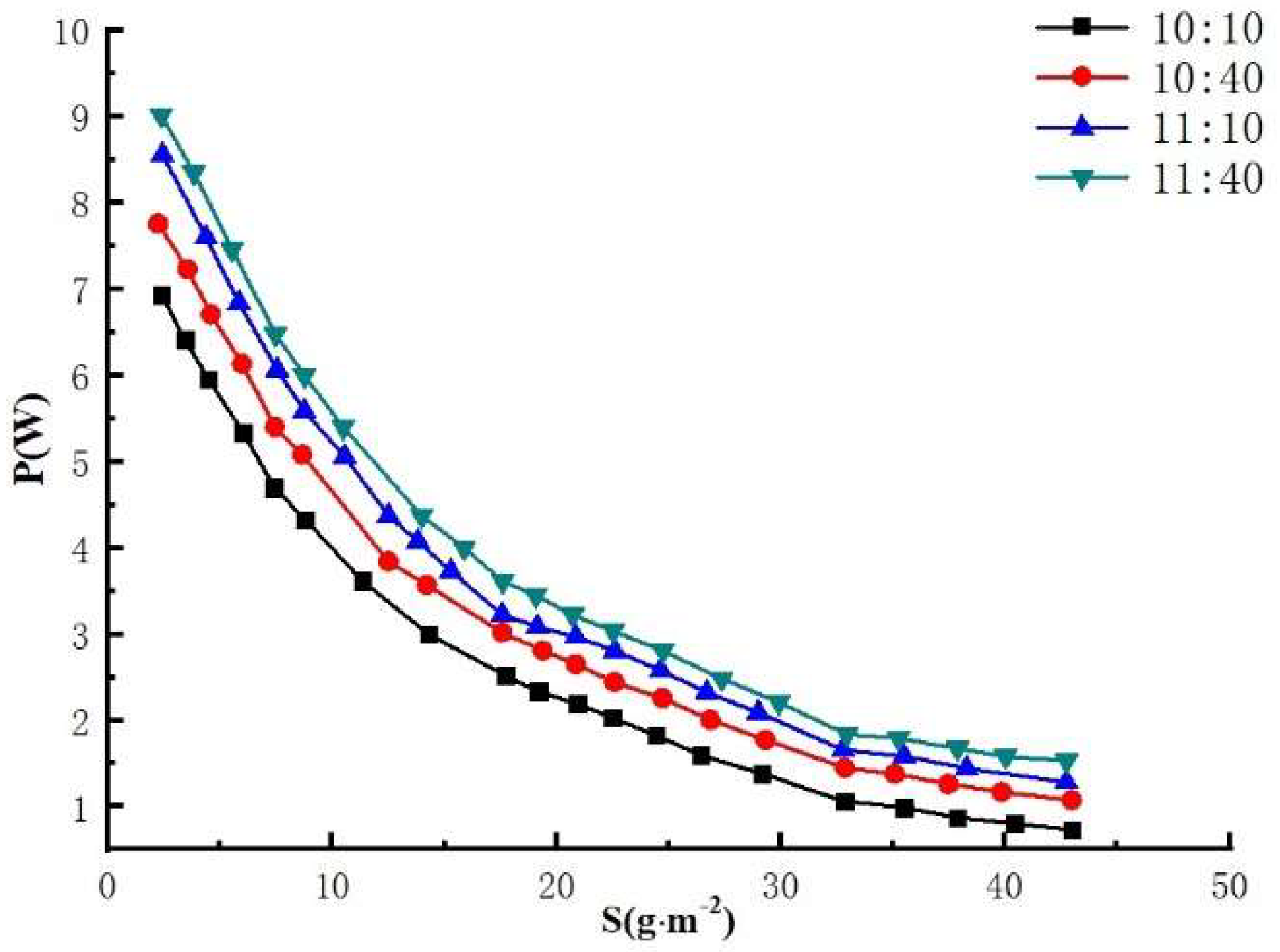

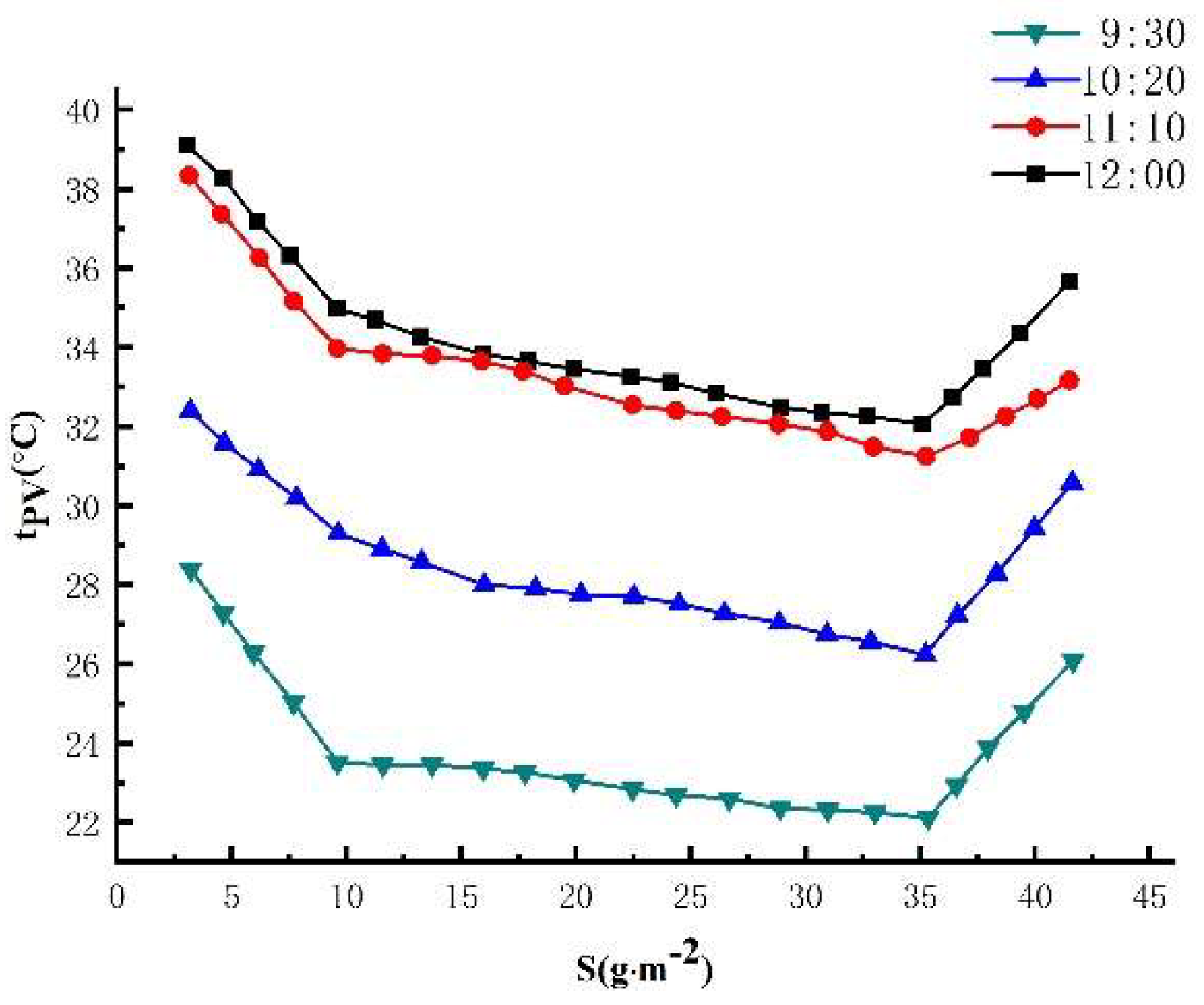

3.2.1. Effect of different sand density on the maximum output power of photovoltaic modules

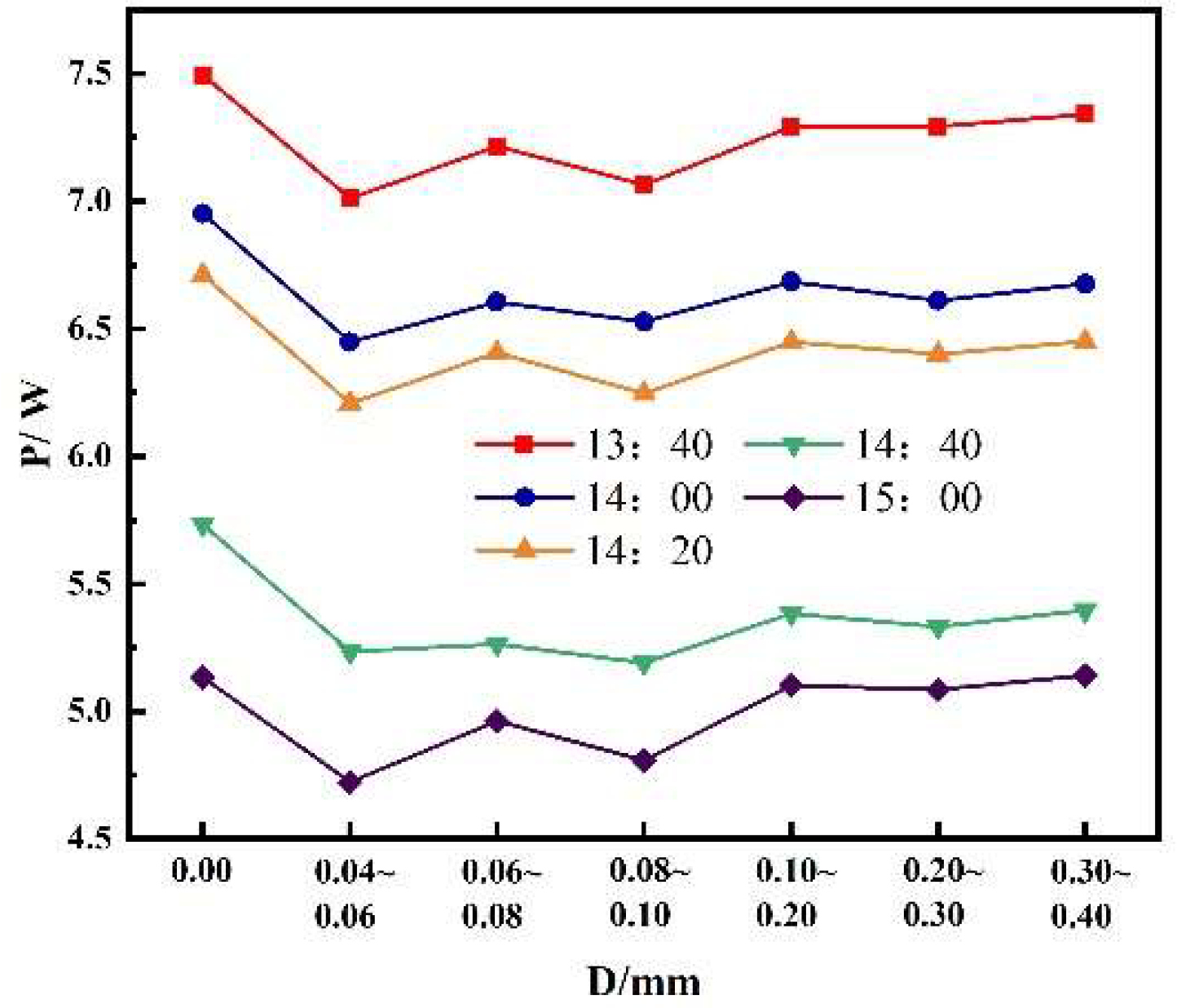

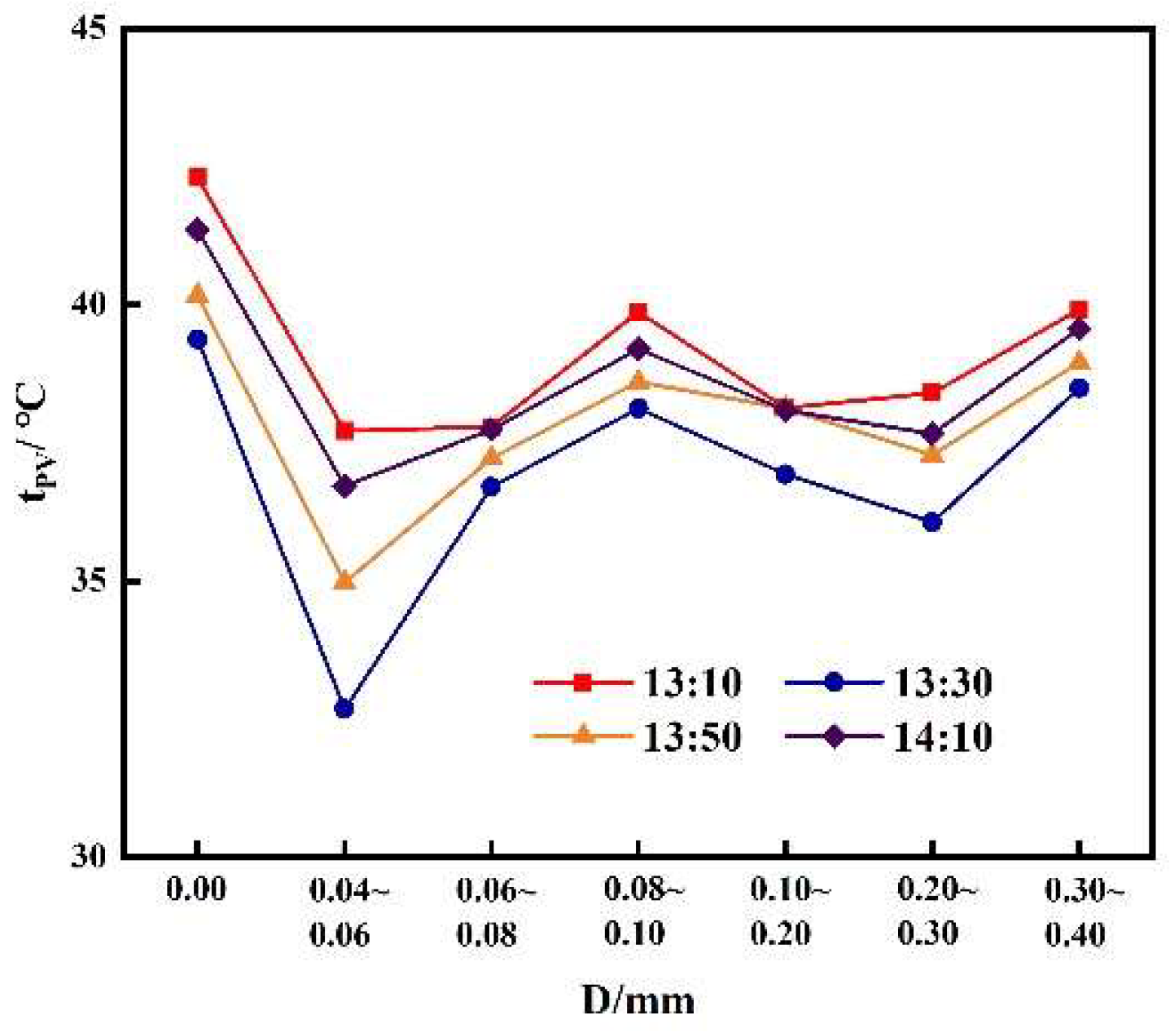

3.2.2. Effect of different sand particle sizes on the maximum output power of photovoltaic modules with the same sand quality

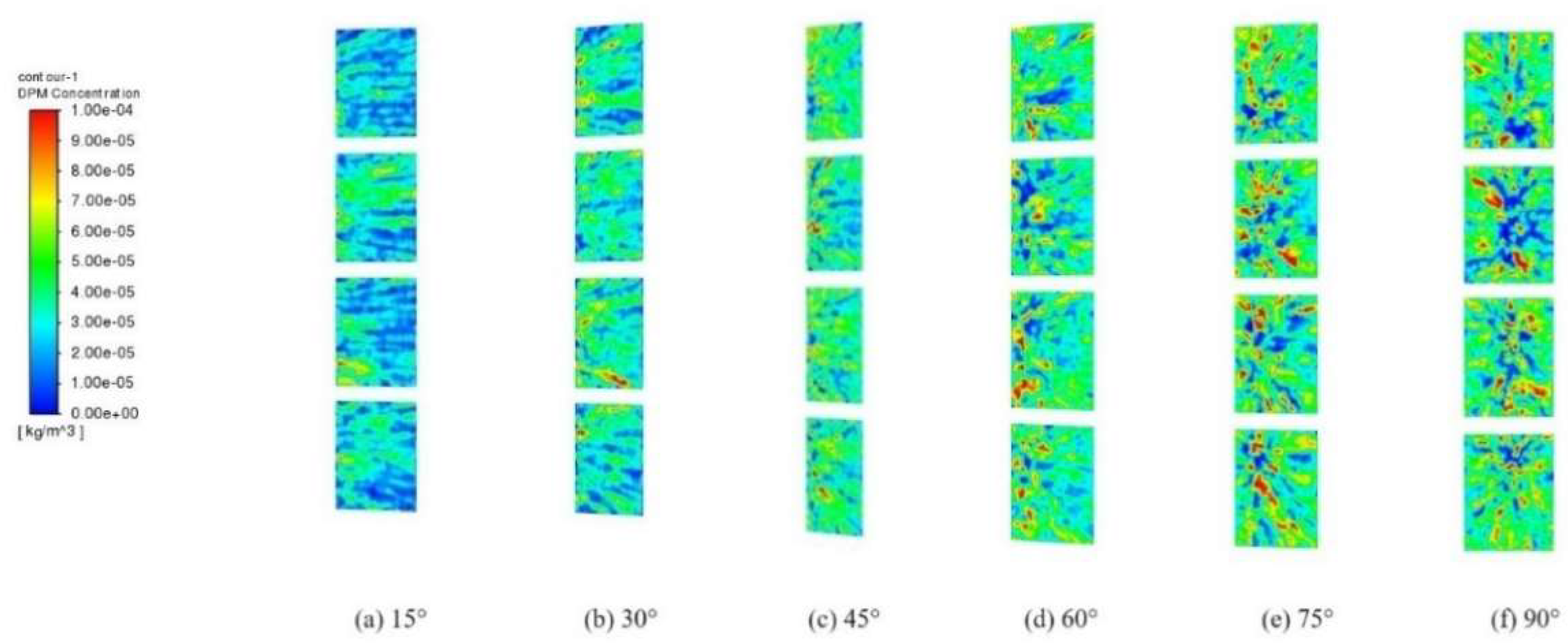

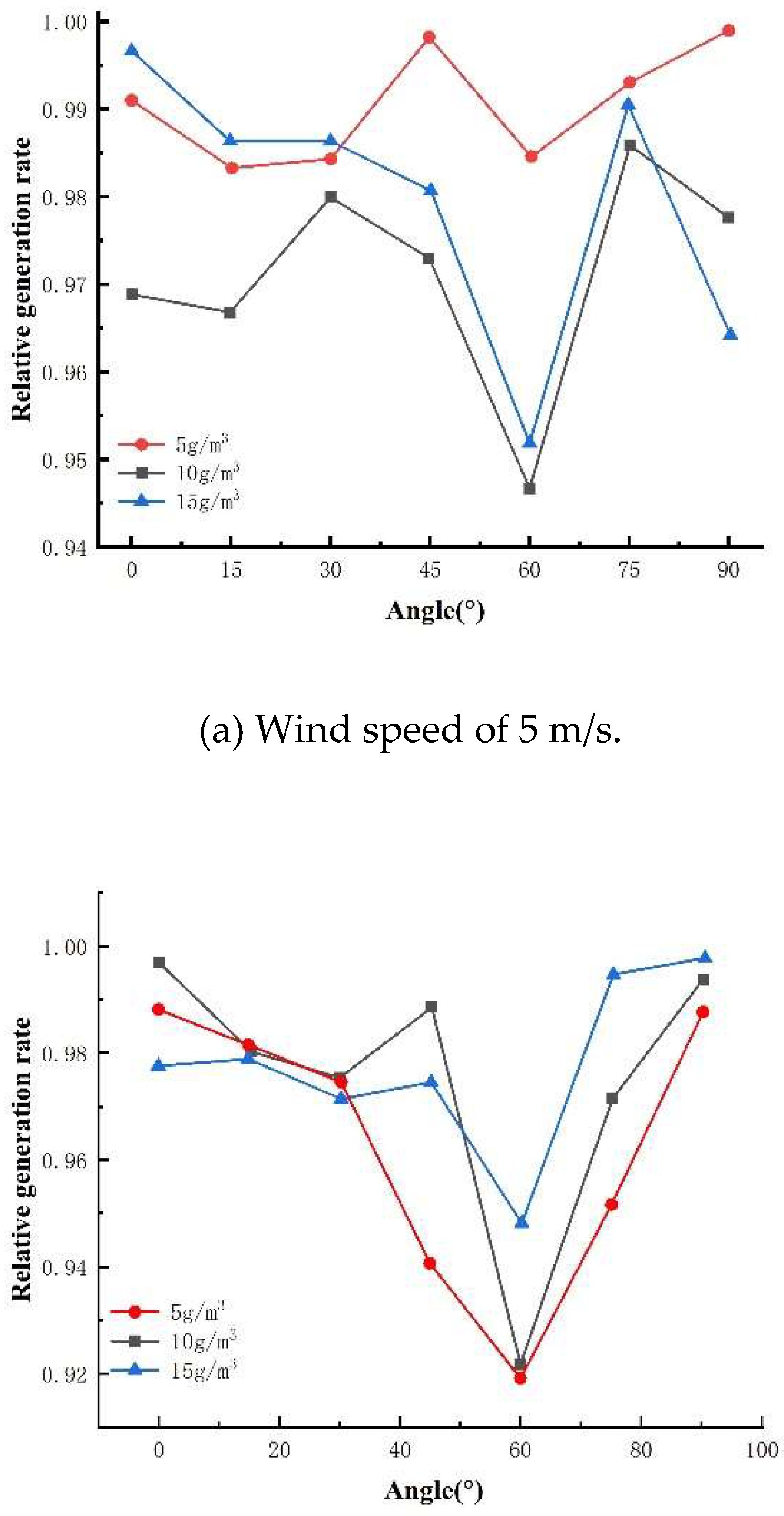

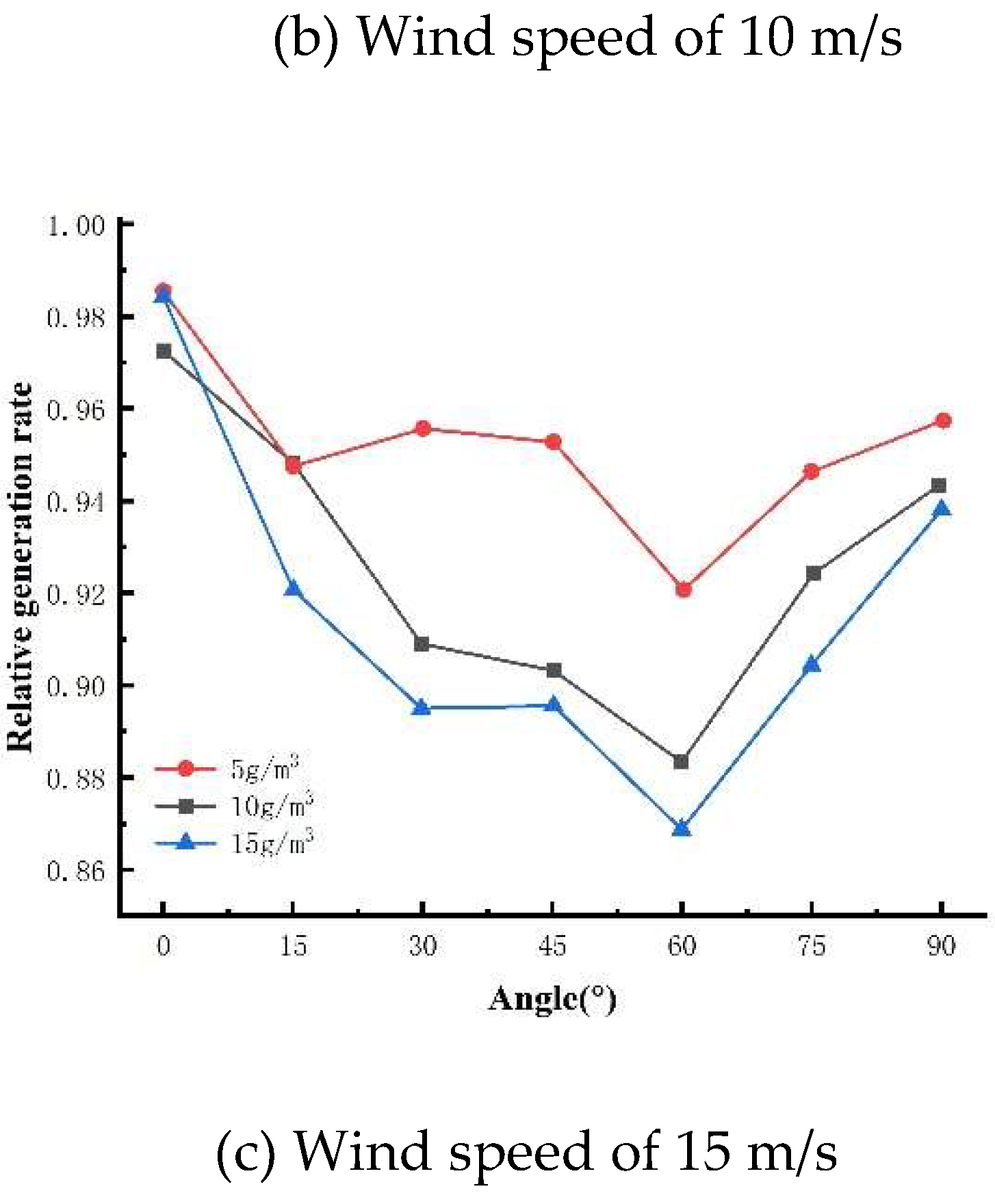

3.2.3. Experimental results and analysis of the relationship between mounting inclination and sand accumulation on the surface of photovoltaic modules

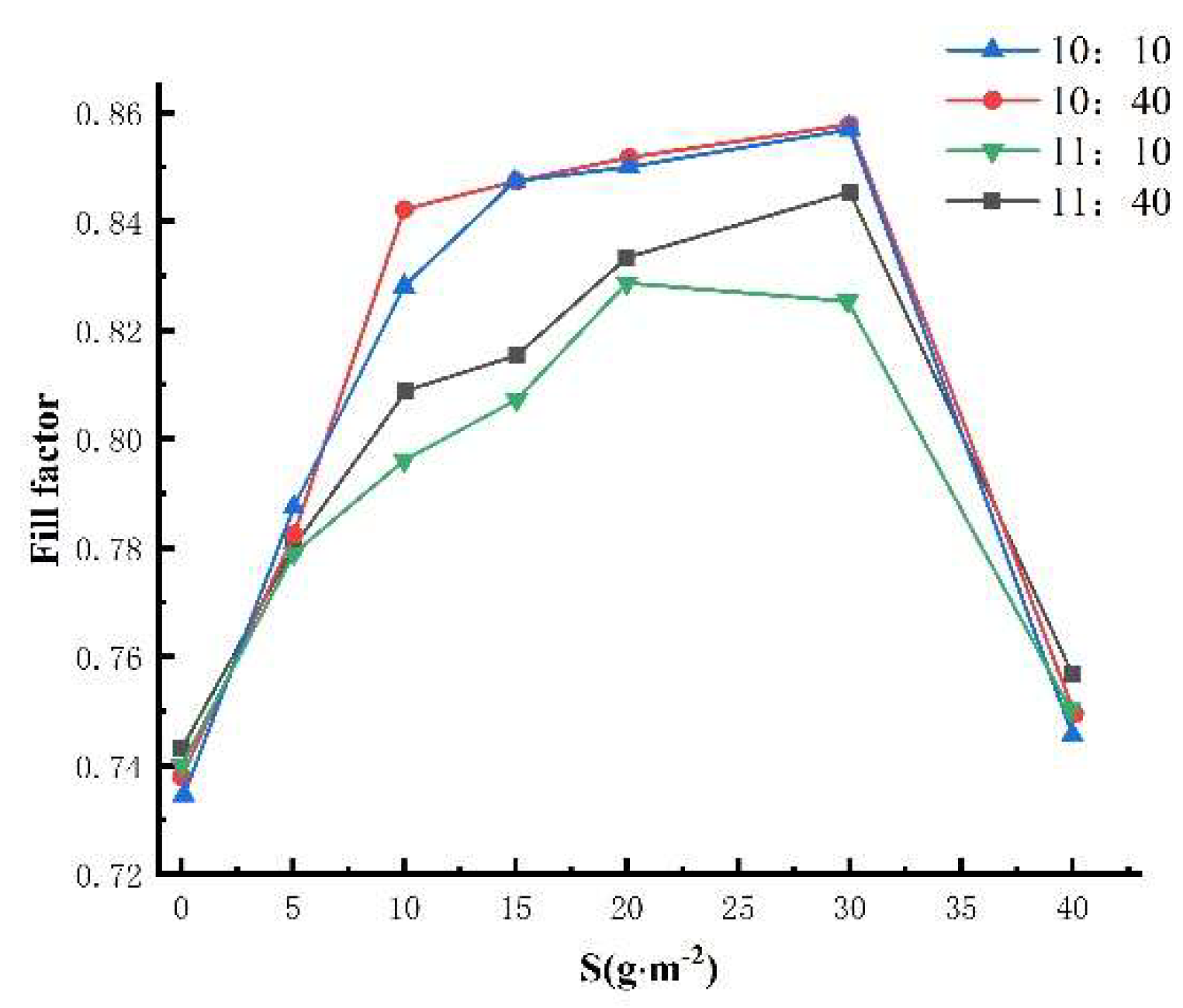

3.2.4. Influence of different sand density on the filling factor of photovoltaic modules

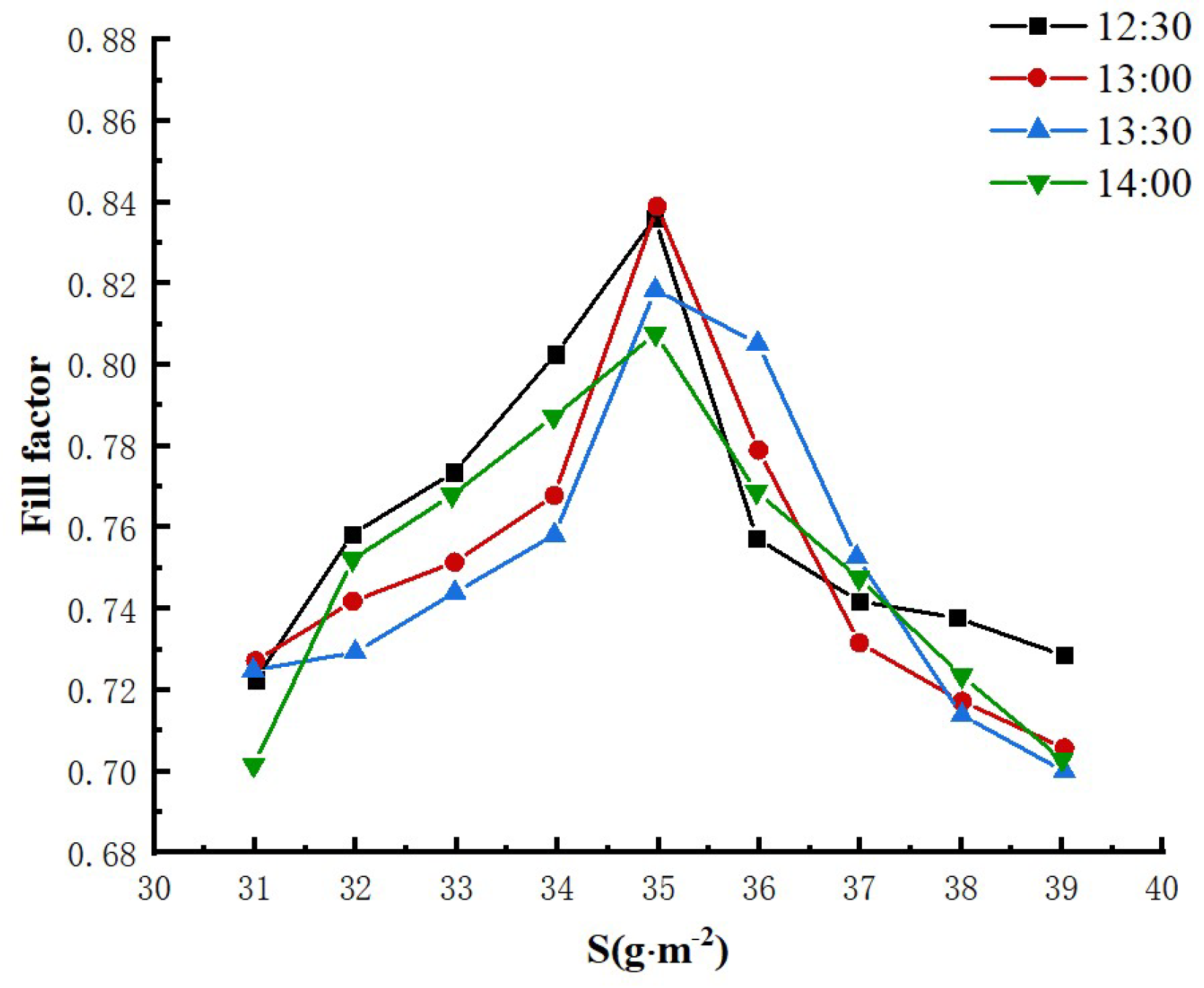

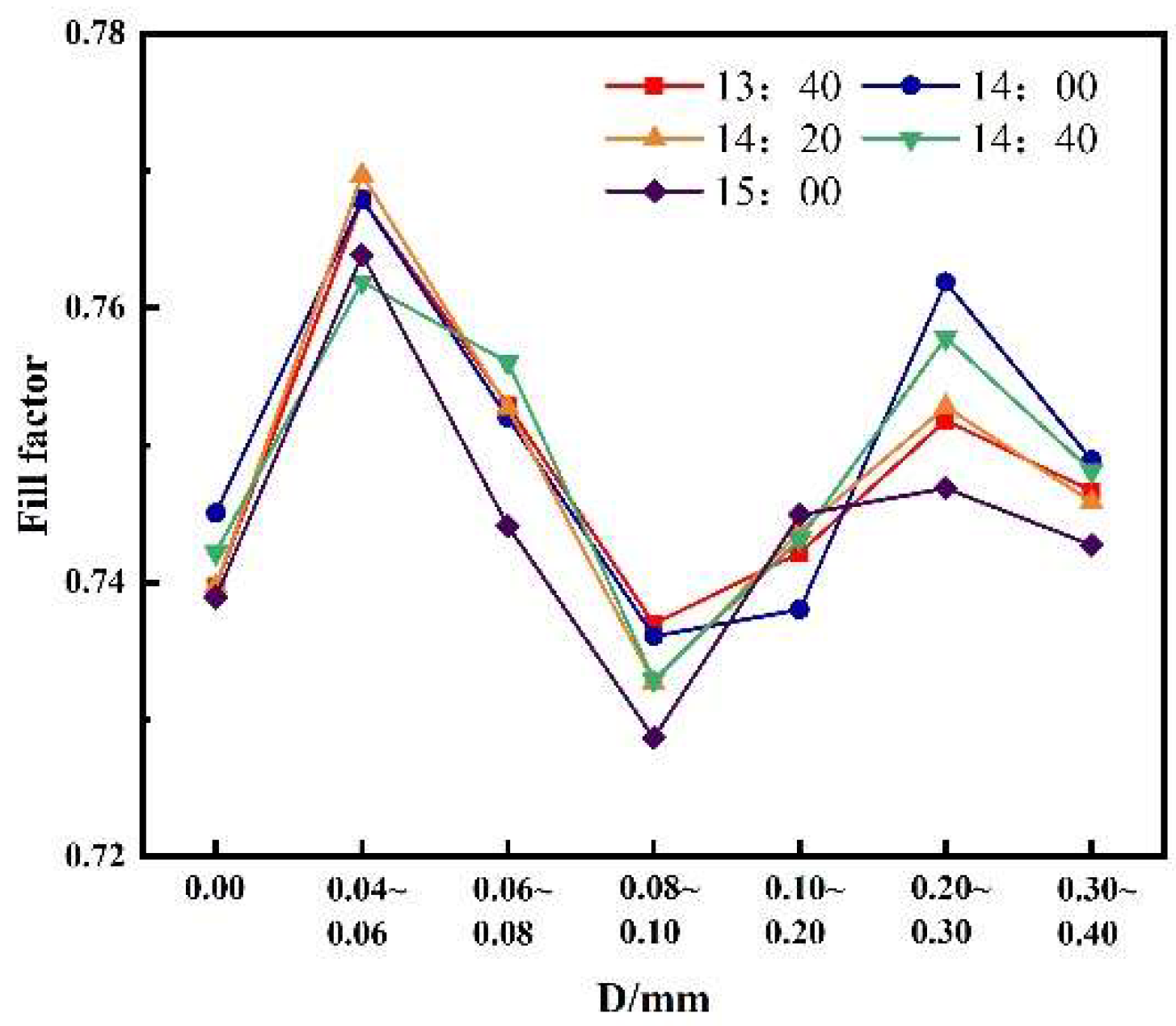

3.2.5. Influence of different sand particle sizes on the filling factor of photovoltaic modules with the same sand quality.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, M.Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.M. Experimental study on effect of desert sand on temperature performance of photovoltaic modules. Journal of Solar Energy 2020, 41, 293–298. [Google Scholar]

- Said, S.A.M.; Walwil, H.M. Fundamental studies on dust fouling effects on PV module performance. Sol Energy 2014, 107, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, B.; Messaoud, H.; Abdelkader, C.; Mohammed, M.; Salah, L.; Mohammed, S.; Nadir, B.; Mourad, O.; Attoui, I. Analysis and evaluation of the impact of climatic conditions on the photovoltaic modules performance in the desert environment. Energy Conversion and Management 2015, 106, 1345–1355. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, M.; Abderrezzaq, Z.; Ahmed, B.; Seyfallah, K. Effect of sand dust accumulation on photovoltaic performance in the Saharan environment: southern Algeria (Adrar). Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2019, 26, 259–268. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.Y.; Li, S.Y.; J., J.M.; Liu, T.S.; Wu, H.Z.; Juan Wang, Li, X.C. The influence of dust deposition on the temperature of soiling photovoltaic glass under lighting and windy conditions. Solar Energy 2020, 199, 491–496. [CrossRef]

- Amirpouya Hosseini, Mojtaba Mirhosseini, Reza Dashti. Analytical study of the effects of dust on photovoltaic module performance in Tehran, capital of Iran.

- Yue, G.W.; Bei, W.; Jia, H.N. Theoretical simulation and wind tunnel experiment in wind-blown sand movement. Arid Land Geography 2014, 37, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, Y.M.; Zu, R.P.; Wang, R. Effects of moisture content on sand flow in Hobq desert; a wind tunnel simulation. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 2016, 30, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Bai, J.B.; Hao, Y.Z. Effect of surface area ash of photovo-Itaic module on its power generation performance. Power System and Clean Energy 2012, 28, 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Bai, J.B.; Cao, Y. Effect of ash accumulation on the performance of roofing photovoltaic power plant. Renewable Energy 2013, 31, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.X.; Wang, H.; Li, S.J. Effect of dust deposition on power generation performance of photovoltaic modules. Distributed Energy 2017, 2, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.J.; Tian, R.; Guo, L. Research on the ash accumulation characteristics of photovoltaic module and its transmission attenuation law. Journal of Agricultural Engineering 2019, 35, 242–250. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tian, Z. Experimental Study on the Effect of Dust Deposition on Photovoltaic Panels[J]. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dida M, Boughali S, Bechki, D., et al. Output power loss of crystalline silicon photovoltaic modules due to dust accumulation in Saharan environment. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 124, 109787. [CrossRef]

- Lasfar, S.; Haidara, F.; Mayouf, C. Study of the influence of dust deposits on photovoltaic solar panels: Case of Nouakchott. Energy for Sustainable Development 2021, 63, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S. S.; Faraji, J.; Nazififard, M. The experimental analysis of dust deposition effect on solar photovoltaic panels in Iran's desert environment. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2021, 47, 101542. [Google Scholar]

- Dhaouadi, R.; Al-Othman, A.; Aidan, A.A. A characterization study for the properties of dust particles collected on photovoltaic (PV) panels in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. Renewable energy 2021, 171, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. ; Delan; LI, D. Effects of ash accumulation and light intensity on the output power of photovoltaic modules. Journal of Agricultural Engineering 2019, 35, 203–211.

- Yao, W.; Han, X.; Huang, Y. Analysis of the influencing factors of the dust on the surface of photovoltaic panels and its weakening law to solar radiation — A case study of Tianjin. Energy 2022, 256, 124669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndeto, M.P.; Wekesa, D.W.; Njoka, F. Aeolian dust distribution, elemental concentration, characteristics and its effects on the conversion efficiency of crystalline silicon solar cells. Renewable Energy 2023, 208, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodakaram-Tafti, A.; Yaghoubi, M. ;Experimental study on the effect of dust deposition on photovoltaic performance at various tilts in semi-arid environment. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2020, 42, 100822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, U.; Al-Sulaiman, F.A.; Yilbas, B.S. Characterization of dust collected from PV modules in the area of Dhahran, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and its impact on protective transparent covers for photovoltaic applications. Solar Energy 2017, 141, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.L.; Li, Y.J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, R.S.; Guo, S.C.; Zhang, P.; Du, P.J. Solar photovoltaic program helps turn deserts green in China: Evidence from satellite monitoring. Journal of Environmental Management, 2022; 324, 116338. [Google Scholar]

- Adinoyi, M.J.; Said, S.A.M. Effect of dust accumulation on the power outputs of solar photovoltaic modules. Renewable Energy 2013, 60, 633–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hangan, S.A.B.A. A comparative investigation of the TTU pressure envelope. Numerical versus laboratory and full scale results. Wind & structures, 2002.

- Baetke, F.; Werner, H.; Wengle, H. Numerical simulation of turbulent flow over surface-mounted obstacles with sharp edges and corners. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics 1990, 35, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.A. General temperature dependence of solar cell performance and implications for device modelling. Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications 2003, 11, 333–340. [Google Scholar]

- Ai-Hasan, A.Y. A new correlation between photovoltaic panels efficiency and amount of sand dust accumulated on their surface. Renewable Energy 2001, 22, 525–540. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso -Garcia, M.C.; Ruiz, J.M. Experimental study of mismatch and shading effects in the I -V characteristic of a photovoltaic module. Solar Energy Materials 2006, 90, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.L.; Florschuetz, L.W. Cost studies on terrestrial photovoltaic power systems with sunlight concentration. Solar Energy 2019, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schill, C.; Brachmann, S.; Koehl, M. Impact of soiling on IV curves and efficiency of PV-modules. Sol. Energy 2015, 112, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoplakie; Palyvos, J.A. On the temperature dependence of photovoltaic module electrical performance: A review of efficiency/power correlations. Solar Energy 2009, 83, 614–624. [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.L.; Florschuetz, L.W. Cost studies on terrestrial photovoltaic power systems with sunlight concentration. Solar Energy 2019, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyah, A.; Horenstein, M.N.; Mazumder, M.K. Energy yield loss caused by dust deposition on photovoltaic panels. Sol. Energy 2014, 107, 576–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldellis, J.K.; Kapsali, M.; Kavadias, K.A. Temperature and wind speed impact on the efficiency of PV installations. Experience obtained from outdoor measurements in Greece. Renew. Energy 2014, 66, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yang, A.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Si, Z. Experimental study on the influence of multi-factor coupling on the surface temperature of photovoltaic modules. J. Solar Energy 2019, 40, 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Maghami, M.R.; Hizam, H.; Gomes, C.; Radzi, M.A.; Rezadad, M.I.; Hajighorbani, S. Power loss due to soiling on solar panel: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev 2016, 59, 1307–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.L.; Wang, X.J.; Zuo, J. Renewable energy in buildings in China –a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 2013, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Boundary condition setting | |

|---|---|

| Sand particles incidence mode | Surface |

| PV module surface particle deposition method | Trap |

| Inlet speed | 5m/s、10m/s、15m/s |

| Gravity acceleration | 9.81kg/m3 |

| Particle Size D/mm | Percentage % | Particle Size D/mm | Percentage /% |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00~0.02 0.02~0.04 0.04~0.06 0.06~0.08 0.08~0.10 0.10~0.20 0.20~0.30 0.30~0.40 |

0.00 0.05 0.36 1.01 13.90 82.51 1.92 0.15 |

0.40~0.50 0.50~0.60 0.60~0.70 0.70~0.80 0.80~0.90 0.90~1.00 >1.00 |

0.02 0.02 0.02 0.02 0.01 0.01 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).