Submitted:

31 October 2023

Posted:

03 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Results and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bahavarnia, F., M. Hasanzadeh, D. Sadighbayan and F. Seidi, Recent Progress and Challenges on the Microfluidic Assay of Pathogenic Bacteria Using Biosensor Technology. Biomimetics, 2022, 7.

- Singh, P., V.K. Pandey, S. Srivastava and R. Singh, A systematic review on recent trends and perspectives of biosensors in food industries. Journal of Food Safety, 2023.

- Herrera-Dominguez, M., G. Morales-Luna, J. Mahlknecht, Q. Cheng, I. Aguilar-Hernandez and N. Ornelas-Soto, Optical Biosensors and Their Applications for the Detection of Water Pollutants. Biosensors-Basel, 2023, 13.

- Uhuo, O.V., T.T. Waryo, K.C. Januarie, K.C. Nwambaekwe, M.M. Ndipingwi, P. Ekwere and E.I. Iwuoha, Bioanalytical methods encompassing label-free and labeled tuberculosis aptasensors: A review. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2022, 1234.

- Uniyal, A., G. Srivastava, A. Pal, S. Taya and A. Muduli, Recent Advances in Optical Biosensors for Sensing Applications: a Review. Plasmonics 2023, 18, 735–750. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.C., R.C. Zhang, R.Z. Bi and M. Olivo, Applications of Optical Fiber in Label-Free Biosensors and Bioimaging: A Review. Biosensors-Basel, 2023, 13.

- Khonina, S.N., G.S. Voronkov, E.P. Grakhova, N.L. Kazanskiy, R.V. Kutluyarov and M.A. Butt, Polymer Waveguide-Based Optical Sensors-Interest in Bio, Gas, Temperature, and Mechanical Sensing Applications. Coatings, 2023, 13.

- Ning, S.P., H.C. Chang, K.C. Fan, P.Y. Hsiao, C.H. Feng, D. Shoemaker and R.T. Chen, A point-of-care biosensor for rapid detection and differentiation of COVID-19 virus (SARS-CoV-2) and influenza virus using subwavelength grating micro-ring resonator. Applied Physics Reviews, 2023, 10.

- Wang, R.D., M.L. Yan, M. Jiang, Y. Li, X. Kang, M.X. Hu, B.B. Liu, Z.Q. He and D.P. Kong, Label-free and selective cholesterol detection based on multilayer functional structure coated fiber fabry-perot interferometer probe. Analytica Chimica Acta, 2023, 1252.

- Miyan, H., R. Agrahari, S.K. Gowre, P.K. Jain and M. Mahto, Computational study of 2D photonic crystal based biosensor for SARS-COV-2 detection. Measurement Science and Technology, 2023, 34.

- Taya, S.A., N. Doghmosh, A.H.M. Almawgani, A.T. Hindi, I. Colak, A.A.M. Alqanoo, S.K. Patel and A. Pal, Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor Based on STO and Graphene Sheets for Detecting Two Commonly Used Buffers: TRIS-Borate-EDTA and Dulbecco Phosphate Buffered Saline. Plasmonics, 2023.

- Coco, A.S., F.V. Campos, C.A.R. Diaz, M.C.C. Guimaraes, A.R. Prado and J.P. de Oliveira, Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance-Based Nanosensor for Rapid Detection of Glyphosate in Food Samples. Biosensors-Basel, 2023, 13.

- Wu, B., G.G. Rong, J.W. Zhao, S.L. Zhang, Y.X. Zhu and B.Y. He, A Nanoscale Porous Silicon Microcavity Biosensor for Novel Label-Free Tuberculosis Antigen-Antibody Detection. Nano, 2012, 7.

- Rong, G.G., Y. Q. Zheng, X.Q. Li, M.Z. Guo, Y. Su, S.M. Bian, B.B. Dang, Y. Chen, Y.J. Zhang, L.H. Shen, et al., A high-throughput fully automatic biosensing platform for efficient COVID-19 detection. Biosensors & Bioelectronics, 2023, 220.

- Rong, G., A. Najmaie, J.E. Sipe and S.M. Weiss, Nanoscale porous silicon waveguide for label-free DNA sensing. Biosensors & Bioelectronics 2008, 23, 1572–1576. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, G.G., Y.Q. Zheng, X. Yang, K.J. Bao, F. Xia, H.H. Ren, S.M. Bian, L. Li, B.W. Zhu and M. Sawan, A Closed-Loop Approach to Fight Coronavirus: Early Detection and Subsequent Treatment. Biosensors-Basel, 2022, 12.

- Weiss, S.M. and G.G. Rong, Porous Silicon Waveguides for Small Molecule Detection. Nanoscience and Nanotechnology for Chemical and Biological Defense, 2009, 1016, 185-+.

- Kaliteevski, M., I. Iorsh, S. Brand, R.A. Abram, J.M. Chamberlain, A.V. Kavokin and I.A. Shelykh, Tamm plasmon-polaritons: Possible electromagnetic states at the interface of a metal and a dielectric Bragg mirror. Physical Review B, 2007, 76.

- Sasin, M.E., R.P. Seisyan, M.A. Kalitteevski, S. Brand, R.A. Abram, J.M. Chamberlain, A.Y. Egorov, A.P. Vasil'ev, V.S. Mikhrin and A.V. Kavokin, Tamm plasmon polaritons: Slow and spatially compact light. Applied Physics Letters, 2008, 92.

- Lu, H., Y.W. Li, H. Jia, Z.W. Li, D. Ma and J.L. Zhao, Induced reflection in Tamm plasmon systems. Optics Express, 2019, 27, 5383–5392. [CrossRef]

- Normani, S., F.F. Carboni, G. Lanzani, F. Scotognella and G.M. Paterno, The impact of Tamm plasmons on photonic crystals technology. Physica B-Condensed Matter, 2022; 645.

- Toanen, V., C. Symonds, J.M. Benoit, A. Gassenq, A. Lemaitre and J. Bellessa, Room-Temperature Lasing in a Low-Loss Tamm Plasmon Cavity. Acs Photonics, 2020, 7, 2952–2957. [CrossRef]

- Pyatnov, M.V., R.G. Bikbaev, I.V. Timofeev and S.Y. Vetrov, Model of a tunable hybrid Tamm mode-liquid crystal device. Applied Optics, 2020, 59, 6347–6351. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.J., Y. Huang, S.C. Zhong, T.L. Lin, Z.H. Zhang, Q.M. Zeng, L.G. Yao, Y.J. Yu and Z.K. Peng, Tamm plasmon polaritons induced active terahertz ultra-narrowband absorbing with MoS2. Optics and Laser Technology, 2022; 156.

- Zhang, X.L., J.F. Song, X.B. Li, J. Feng and H.B. Sun, Optical Tamm states enhanced broad-band absorption of organic solar cells. Applied Physics Letters, 2012, 101.

- Elsayed, H.A., T.A. Taha, S.A. Algarni, A.M. Ahmed and A. Mehaney, Evolution of optical Tamm states in a 1D photonic crystal comprising a nanocomposite layer for optical filtering and reflecting purposes. Optical and Quantum Electronics, 2022, 54.

- Ruan, B.X., M. Li, C. Liu, E.D. Gao, Z.B. Zhang, X. Chang, B.H. Zhang and H.J. Li, Slow-light effects based on the tunable Fano resonance in a Tamm state coupled graphene surface plasmon system. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 2023, 25, 1685–1689. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.M., H.A. Elsayed and A. Mehaney, High-Performance Temperature Sensor Based on One-dimensional Pyroelectric Photonic Crystals Comprising Tamm/Fano Resonances. Plasmonics, 2021, 16, 547–557. [CrossRef]

- Sabra, W., H.A. Elsayed, A. Mehaney and A.H. Aly, Numerical optimization of 1D superconductor photonic crystals pressure sensor for low temperatures applications. Solid State Communications, 2022, 343.

- Hao, H.Y., F. Xing and L. Li, Plasmon-based optical sensors for high-sensitivity surface deformation detection of silver and gold. Applied Nanoscience, 2020, 10, 3939–3944.

- Zaky, Z.A., M. Al-Dossari, E.I. Zohny and A.H. Aly, Refractive index sensor using Fibonacci sequence of gyroidal graphene and porous silicon based on Tamm plasmon polariton. Optical and Quantum Electronics, 2023, 55.

- Sansierra, M.C., J. Morrone, F. Cornacchiulo, M.C. Fuertes and P.C. Angelome, Detection of Organic Vapors Using Tamm Mode Based Devices Built from Mesoporous Oxide Thin Films. Chemnanomat, 2019, 5, 1289–1295. [CrossRef]

- Zaky, Z.A., H. Hanafy, A. Panda, P.D. Pukhrambam and A.H. Aly, Design and Analysis of Gas Sensor Using Tailorable Fano Resonance by Coupling Between Tamm and Defected Mode Resonance. Plasmonics, 2022, 17, 2103–2111. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.M., Q. W. Zheng, H.X. Yuan, S.P. Wang, K.Q. Yin, X.Y. Dai, X. Zou and L.Y. Jiang, High Sensitivity Terahertz Biosensor Based on Mode Coupling of a Graphene/Bragg Reflector Hybrid Structure. Biosensors-Basel, 2021, 11.

- Panda, A. and P. D. Pukhrambam, Study of Metal-Porous GaN-Based 1D Photonic Crystal Tamm Plasmon Sensor for Detection of Fat Concentrations in Milk. Micro and Nanoelectronics Devices, Circuits and Systems, 2023, 904, 415–425. [Google Scholar]

- Maji, P.S., M. K. Shukla and R. Das, Blood component detection based on miniaturized self-referenced hybrid Tamm-plasmon-polariton sensor. Sensors and Actuators B-Chemical, 2018, 255, 729–734. [Google Scholar]

- Su, M.Y., K.S. Li, C.F. Wang, L.M. Wu, S. Yang, Q.W. Lin, Y. Li, L.P. Tang and R.L. Zhou, Tamm-plasmon-polariton biosensor based on one-dimensional topological photonic crystal. Results in Physics, 2023, 48.

- Hou, Q.R. and N. Chi, Calculation of surface areas for porous silicon. Modern Physics Letters B, 1999, 13, 1005–1009. [CrossRef]

- Northen, T.R., H.K. Woo, M.T. Northen, A. Nordström, W. Uritboonthail, K.L. Turner and G. Siuzdak, High surface area of porous silicon drives desorption of intact molecules. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry, 2007, 18, 1945–1949. [CrossRef]

- Li, C., H.L. Liao, R. Huang and Y.Y. Wang, A CMOS-compatible silicon substrate optimization technique and its application in radio frequency crosstalk isolation. Chinese Physics B, 2008, 17, 2730–2738. [CrossRef]

- Juneau-Fecteau, A. and L.G. Frechette, Tamm plasmon-polaritons in a metal coated porous silicon photonic crystal. Optical Materials Express, 2018, 8, 2774–2781. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.M. and A. Mehaney, Ultra-high sensitive 1D porous silicon photonic crystal sensor based on the coupling of Tamm/Fano resonances in the mid-infrared region. Scientific Reports, 2019, 9.

- Juneau-Fecteau, A., R. Savin, A. Boucherif and L.G. Frechette, A practical Tamm plasmon sensor based on porous Si. Aip Advances, 2021, 11.

- Vyunishev, A.M., R.G. Bikbaev, S.E. Svyakhovskiy, I.V. Timofeev, P.S. Pankin, S.A. Evlashin, S.Y. Vetrov, S.A. Myslivets and V.G. Arkhipkin, Broadband Tamm plasmon polariton. Journal of the Optical Society of America B-Optical Physics, 2019, 36, 2299–2305.

- Jeng, S.C., Applications of Tamm plasmon-liquid crystal devices. Liquid Crystals, 2020, 47, 1223–1231. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A., S. Kumar, M.K. Shukla, G. Kumar, P.S. Maji, R. Vijaya and R. Das, Coupling to Tamm-plasmon-polaritons: dependence on structural parameters. Journal of Physics D-Applied Physics, 2018, 51.

- Khardani, M., M. Bouaicha and B. Bessais, Bruggeman effective medium approach for modelling optical properties of porous silicon: comparison with experiment. Physica Status Solidi C - Current Topics in Solid State Physics 2007, 4, 1986.

- Khardani, M., M. Bouaicha and B. Bessais, Bruggeman effective medium approach for modelling optical properties of porous silicon: comparison with experiment. Journal of the Optical Society of America B-Optical Physics, 2017, 34, 2128–2139.

- Li, X.W., M.Y. Xiong, Q.L. Deng, X.B. Guo and Y.R. Li, The utility of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein in laboratory diagnosis. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis, 2022; 36.

- Litchfield, M., P. Brookes, A. Ojrzynska, J. Kavi and R. Dawood, Comparison of the clinical sensitivity and specificity of two commercial RNA SARS-CoV-2 assays. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2022, 118, 194–196. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, D.A., J.Y. Wang, M.E. Moeser, T. Starkey and L.Y.W. Lee, A systematic review of the sensitivity and specificity of lateral flow devices in the detection of SARS-CoV-2. Bmc Infectious Diseases, 2021; 21.

- Fox, T., J. Geppert, J. Dinnes, K. Scandrett, J. Bigio, G. Sulis, D. Hettiarachchi, Y. Mathangasinghe, P. Weeratunga, D. Wickramasinghe, et al., Antibody tests for identification of current and past infection with SARSCoV-2. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2022.

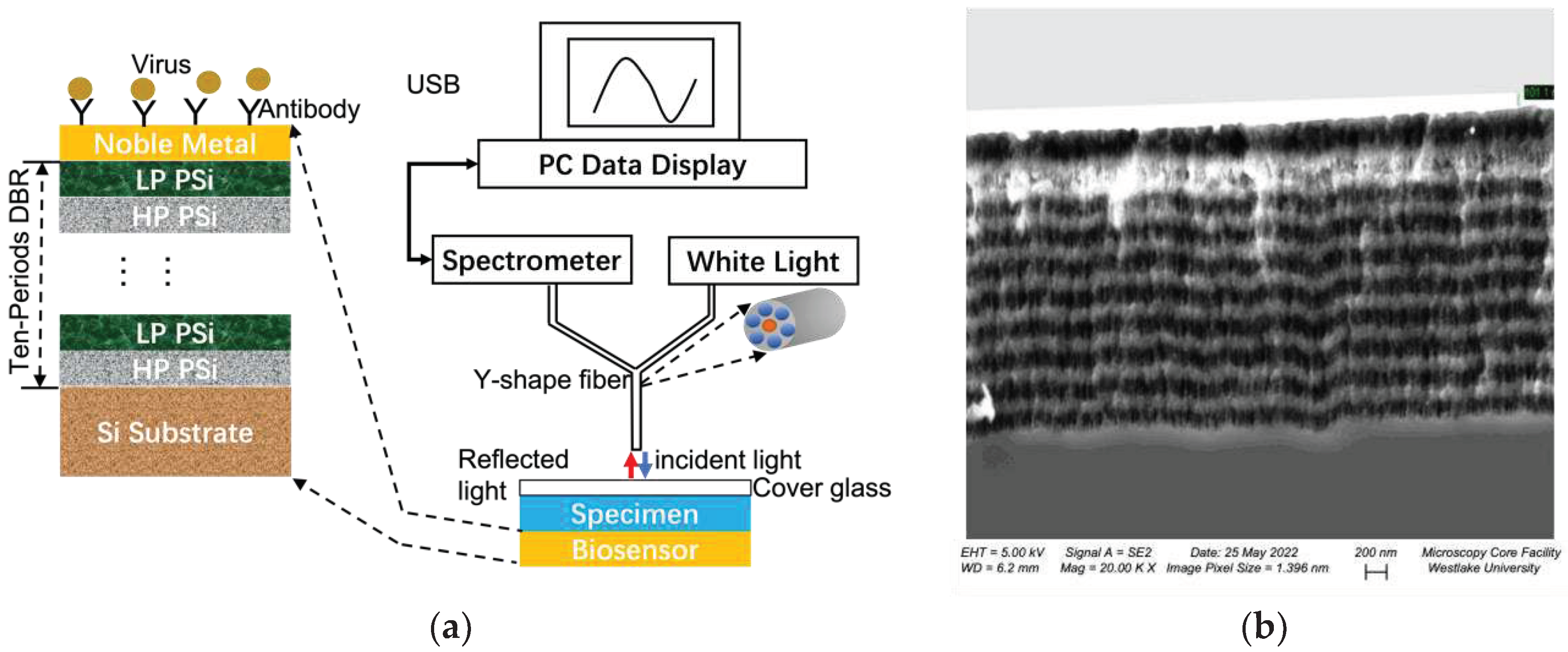

| Structure | Porosity | Current Density | Etch Time | Bruggeman Effective R.I. | Thickness |

| LP PSi | 52% | 5mA/cm2 | 20 seconds | 2.08 | 100 nm |

| HP PSi | 76% | 48mA/cm2 | 6 seconds | 1.41 | 150 nm |

| No. | Step Name | Step Operation |

| 1 | Chip cleaning | Clean the chips using a plasma cleaning machine, ethanol, isopropanol, and ultrapure water, and then place them in a 96 well plate container for later use. |

| 2 | Sulfhydryl proteinA modified chip | Dilute mercapto proteinA (Xlement Cat. No. G60001) with ultrapure water to a working concentration of 50ug/mL, take an appropriate amount of mercapto proteinA solution and add it to the chip surface. Leave at 4°C overnight or 37 ℃ for 2 hours. |

| 3 | Preparation of coating antibody solution | Take COVID-19 N-protein antibody (Xlement Cat. No. C10002), use coupling buffer solution (Xlement Cat. No. S20029) to prepare 50 μg/mL of coating antibody solution. |

| 4 | Chip directed immobilization of antibodies | Take an appropriate amount of 50 μg/mL of coating antibody solution and apply on the surface of the chip and react at 37°C (with shaking) for 20-30 minutes. After reaction, clean the chip twice with Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer solution (pH ~7.4). |

| 5 | Closure | Take an appropriate amount of sealing solution (Xlement Cat. No. G30004) and add it to the surface of the chip. Leave it at 37°C for 30 minutes. After removing and drying the sealing solution, the chips can be used directly for detection assay. Alternatively, perform the following steps before storing chips for future use. |

| 6 | Protection | Take an appropriate amount of protective solution (Xlement Cat. No. G30006) and add it to the surface of the chip. Place it at 37°C for 30 minutes, then remove and dry the protective solution. |

| 7 | Chip drying | Place the modified chip in a 37°C oven and dry for 5 minutes. |

| 8 | Plastic sealing | Use a sealing machine to vacuum seal the wrapped chips and refrigerate them for storage. |

| Technologies | Target | Sensitivity | Specificity | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) [50] | Specific gene sequence, such as ORF1ab | >90% | Nearly 100% | Accurate result, current gold standard, high throughput. | Need clean environment, complex equipment, and staff training, slow turnaround |

| Antigen detection by lateral flow [51] | Viral proteins such as N-proteinOr S-protein | 37.7%-99.2% | 92.4%-100% | Rapid and onsite detection, no need for equipment. | Accurate only in the 1st week of disease onset, low throughput. |

| Antibody detection by lateral flow [52] | Immune globulin such as IgG or IgM | 41.1%-95% | 98.6-99.8% | Rapid and onsite detection, no need for equipment. | Antibody cross-relation with other infections, low throughput. |

| TPP biosensor(this work) | N-protein | >90% | >95% | Rapid and onsite detection, high throughput. | Need handheld or desktopequipment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).