Submitted:

01 November 2023

Posted:

01 November 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Targets of CK2

3. Subunits of CK2 and their diverse roles

4. Inhibitors of CK2

| Name | Status for Clinical Applica-tion | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Compound 58 | Able to overcome drug resistance in cancer treatment. Targets CK2 and BRD4. | [79,80] |

| Compound 60 | Highly selective. Reduces tumor growth and lessens cancer symptoms in vivo and in vitro, with no apparent side effects. It is considered a potential therapeutic in triple-negative breast cancer. Targets CK2 and BRD4. Has potent and balanced activity against BRD4 and CK2. | [79,80] |

| Naphtho[2,1-b:7,6-b′]difuran-2,8-dicarboxylic acid hydrate (CPA), CPB, AMR | High selectivity for CK2 and the kinase PIM. Lack of cell permeability; hence, it cannot be used clinically. | [81] |

| 8-hydroxy-4-methyl-9-nitrobenzol(g)chrome-2-one (NBC) | High selectivity for CK2 and PIM. Induces apoptosis. | [69,82] |

| 1-β-D-2′-deoxyribofuranosyl-4,5,6,7- tetrabromo-1H-benzimidazole (TDB) | High selectivity for CK2 and PIM. Extremely high selectivity indicates it has clinical potential. | [83] |

| Compound 66 | Cytotoxic against cancer cells but not healthy cells. Inhibits the proliferation of various cancer cell lines. Reduces the viability of cancer cells more effectively than CX-4945. It is membrane-permeable and targets CK2 and PIM. | [82] |

| 6-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxybenzylidene)-5-imino-2-(trifluoromethyl)-5H-[1,3,4]thiadiazolo[3,2-a]pyrimidin-7(6H)-one (SRPIN803; CK2 inhibitor XIII). | Inhibits both CK2 and SRPK1, which causes aberrant angiogenesis. Significantly inhibits cell viability in Jurkat cell lines. In vivo studies suggest it prevents the formation of intraocular neovascularization. | [84] |

| 108600 | Inhibitory effect on CK2/TNIK/DYRK1. The inhibitory effect on CK2α’ is ten times stronger than on CK2α. Inhibits tumor growth in breast cancer cells and overcomes chemical resistance. In vitro and in vivo studies suggest it is an optimal inhibitor in clinical settings. | [85] |

5. Implication of CK2 in musculoskeletal disorders

6. Implications of CK2 in Musculoskeletal Cancers

7. Targeting CK2-Substrate interaction

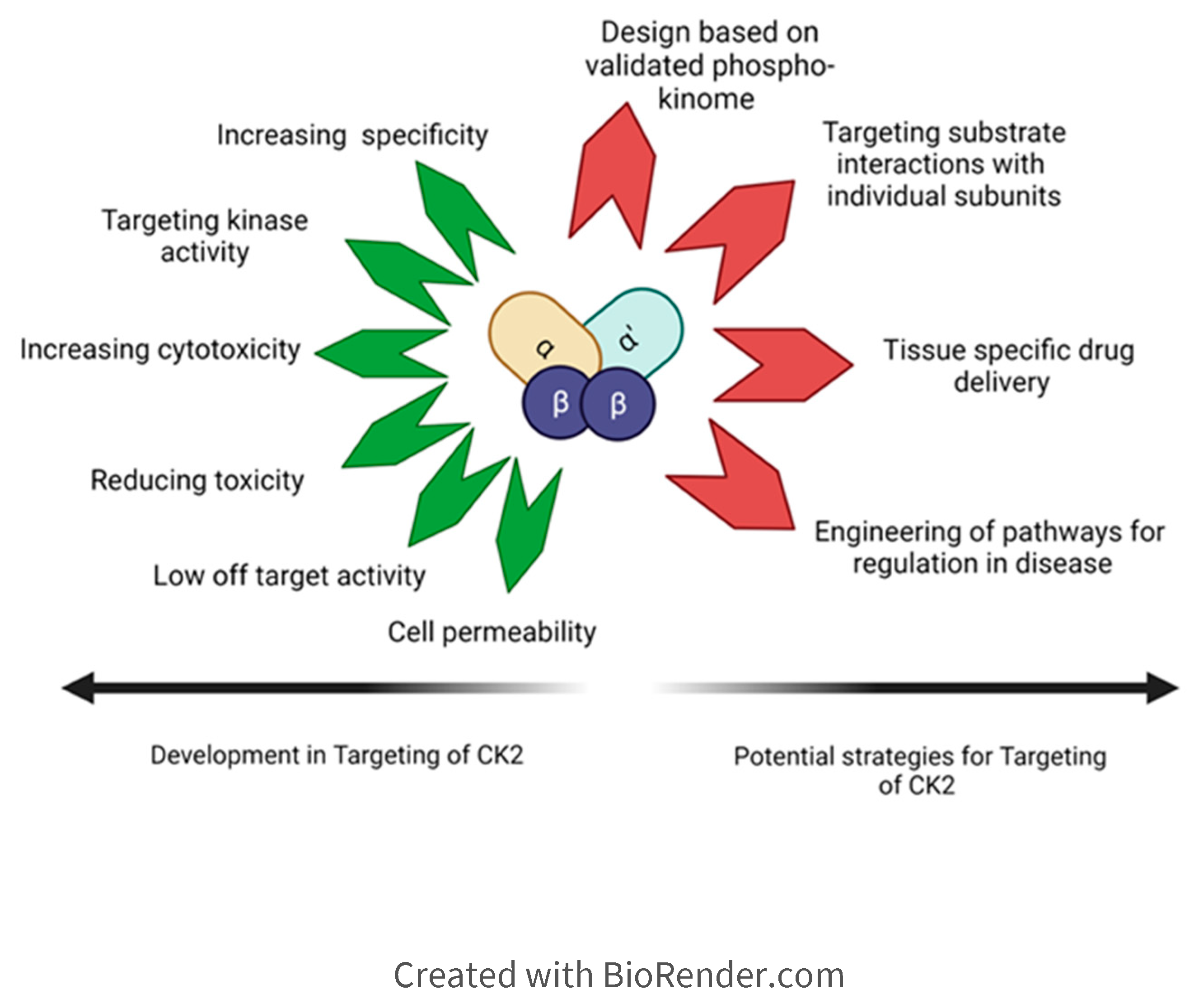

8. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Halloran, D.; Pandit, V.; Nohe, A. The Role of Protein Kinase CK2 in Development and Disease Progression: A Critical Review. J Dev Biol 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgo, C.; D’Amore, C.; Sarno, S.; Salvi, M.; Ruzzene, M. Protein Kinase CK2: A Potential Therapeutic Target for Diverse Human Diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 05 17, 6, 183. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meggio, F.; Pinna, L.A. One-Thousand-and-One Substrates of Protein Kinase CK2? FASEB J 2003, 17, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franchin, C.; Borgo, C.; Zaramella, S.; Cesaro, L.; Arrigoni, G.; Salvi, M.; Pinna, L.A. Exploring the CK2 Paradox: Restless, Dangerous, Dispensable. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2017, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgo, C.; D’Amore, C.; Cesaro, L.; Sarno, S.; Pinna, L.A.; Ruzzene, M.; Salvi, M. How Can a Traffic Light Properly Work If It Is Always Green? The Paradox of CK2 Signaling. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 2021, 56, 321–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinna, L.A. Protein Kinase CK2: A Challenge to Canons. J Cell Sci 2002, 115, 3873–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinna, L.A. Protein Kinase CK2. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 1997, 29, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, M.; Ortega, C.; Sheikh, A.; Lee, M.; Abdul-Rassoul, H.; Hartshorn, K.; Dominguez, I. CK2 in Cancer: Cellular and Biochemical Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutic Target. Pharmaceuticals 2017, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

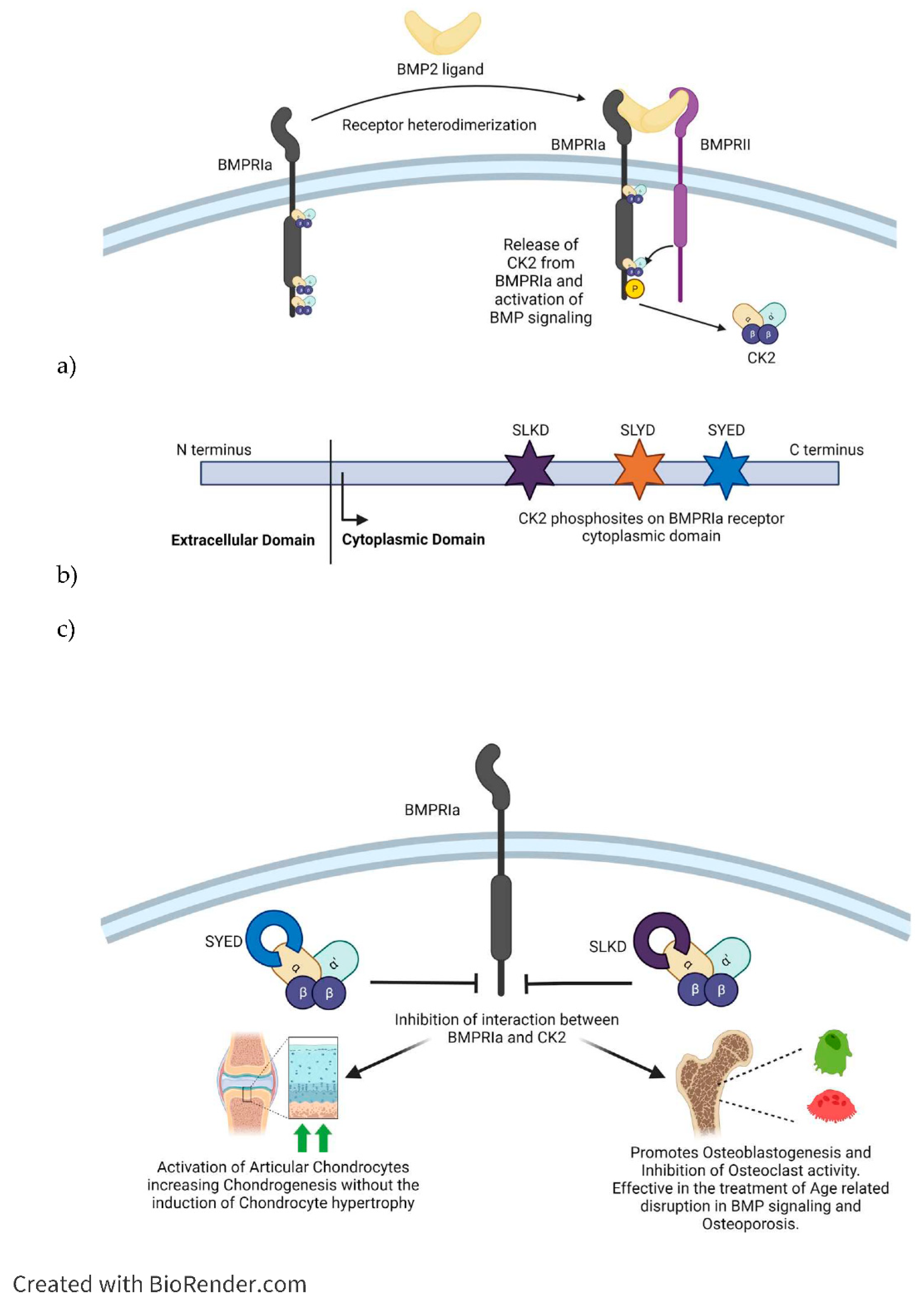

- Bragdon, B.; Thinakaran, S.; Moseychuk, O.; Gurski, L.; Bonor, J.; Price, C.; Wang, L.; Beamer, W.G.; Nohe, A. Casein Kinase 2 Regulates in Vivo Bone Formation through Its Interaction with Bone Morphogenetic Protein Receptor Type Ia. Bone 2011, 49, 944–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Liu, Y.; Xia, R.; Tong, C.; Yue, T.; Jiang, J.; Jia, J. Casein Kinase 2 Promotes Hedgehog Signaling by Regulating Both Smoothened and Cubitus Interruptus. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2010, 285, 37218–37226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, I.; Sonenshein, G.E.; Seldin, D.C. Protein Kinase CK2 in Health and Disease: CK2 and Its Role in Wnt and NF-κB Signaling: Linking Development and Cancer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009, 66, 1850–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.; Pulido, R. The Tumor Suppressor PTEN Is Phosphorylated by the Protein Kinase CK2 at Its C Terminus. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 993–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Qin, H.; Frank, S.J.; Deng, L.; Litchfield, D.W.; Tefferi, A.; Pardanani, A.; Lin, F.-T.; Li, J.; Sha, B.; et al. A CK2-Dependent Mechanism for Activation of the JAK-STAT Signaling Pathway. Blood 2011, 118, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khajuria, D.K.; Reider, I.; Kamal, F.; Norbury, C.C.; Elbarbary, R.A. Distinct Defects in Early Innate and Late Adaptive Immune Responses Typify Impaired Fracture Healing in Diet-Induced Obesity. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1250309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Shen, J.; Li, X.; Bao, Y.; Zhao, T.; Li, B.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Gao, J.; Xie, Z.; et al. Regulatory Effects of Quercetin on Bone Homeostasis: Research Updates and Future Perspectives. Am J Chin Med 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, F.; Chappard, D.; Leroyer, P.; Latour, C.; Mabilleau, G.; Monbet, V.; Cavey, T.; Horeau, M.; Derbré, F.; Roth, M.P.; et al. Differences in Bone Microarchitecture between Genetic and Secondary Iron-Overload Mouse Models Suggest a Role for Hepcidin Deficiency in Iron-Related Osteoporosis. FASEB J 2023, 37, e23245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghadir, A.H.; Gabr, S.A.; Iqbal, A. Hand Grip Strength, Vitamin D Status, and Diets as Predictors of Bone Health in 6-12 Years Old School Children. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2023, 24, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.S.P.; Venturini, L.G.R.; Speck-Hernandez, C.A.; Alabarse, P.V.G.; Xavier, T.; Taira, T.M.; Rodrigues, L.F.D.; Cunha, F.Q.; Fukada, S.Y. AMPKα1 Negatively Regulates Osteoclastogenesis and Mitigate Pathological Bone Loss. J Biol Chem 2023, 105379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Gao, M.; Lei, T.; Huang, F.; Chen, H.; Wu, M. Risk Factors for the Comorbidity of Osteoporosis/Osteopenia and Kidney Stones: A Cross-Sectional Study. Arch Osteoporos 2023, 18, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Sung, E.; Kang, J.H.; Kim, C.H.; Shin, H.; Yoo, E.; Kim, M.; Lee, M.Y.; Shin, S. Association between Body Fat and Bone Mineral Density in Korean Adults: A Cohort Study. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 17462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Han, X.; Wang, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, M.; Liu, M. Differential Metabolites in Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobasheri, A.; Rayman, M.P.; Gualillo, O.; Sellam, J.; van der Kraan, P.; Fearon, U. The Role of Metabolism in the Pathogenesis of Osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2017, 13, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.; Jeong, S.; Kim, H.; Kang, D.; Lee, J.; Kang, S.B.; Kim, J.H. Disease-Modifying Therapeutic Strategies in Osteoarthritis: Current Status and Future Directions. Exp Mol Med 2021, 53, 1689–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comertpay, B.; Gov, E. Immune Cell-Specific and Common Molecular Signatures in Rheumatoid Arthritis through Molecular Network Approaches. Biosystems 2023, 234, 105063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Li, S.; Cao, N.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Sun, C.; Xiao, X.; Yao, J. Intestinal Flora, Intestinal Metabolism, and Intestinal Immunity Changes in Complete Freud’s Adjuvant-Rheumatoid Arthritis C57BL/6 Mice. Int Immunopharmacol 2023, 125, 111090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rea, I.M.; Gibson, D.S.; McGilligan, V.; McNerlan, S.E.; Alexander, H.D.; Ross, O.A. Age and Age-Related Diseases: Role of Inflammation Triggers and Cytokines. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarry, T.; Biniecka, M.; Veale, D.J.; Fearon, U. Hypoxia, Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Free Radic Biol Med 2018, 125, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Bae, Y.S. CK2 Down-Regulation Increases the Expression of Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype Factors through NF-κB Activation. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, M.A.; Andrzejewska, M.; Ruzzene, M.; Sarno, S.; Cesaro, L.; Bain, J.; Elliott, M.; Meggio, F.; Kazimierczuk, Z.; Pinna, L.A. Optimization of Protein Kinase CK2 Inhibitors Derived from 4,5,6,7-Tetrabromobenzimidazole. J Med Chem 2004, 47, 6239–6247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarno, S.; Pinna, L.A. Protein Kinase CK2 as a Druggable Target. Mol Biosyst 2008, 4, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trembley, J.H.; Chen, Z.; Unger, G.; Slaton, J.; Kren, B.T.; Van Waes, C.; Ahmed, K. Emergence of Protein Kinase CK2 as a Key Target in Cancer Therapy. Biofactors 2010, 36, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgo, C.; Ruzzene, M. Protein Kinase CK2 Inhibition as a Pharmacological Strategy. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol 2021, 124, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, E.; Do, H.; Joo, H.-M.; Pyo, S. Induction of Alkaline Phosphatase Activity by L-Ascorbic Acid in Human Osteoblastic Cells: A Potential Role for CK2 and Ikaros. Nutrition 2007, 23, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, M.F.; Lewis Lujan, L.; Iloki Assanga, S. Targeting Sirt1, AMPK, Nrf2, CK2, and Soluble Guanylate Cyclase with Nutraceuticals: A Practical Strategy for Preserving Bone Mass. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, F.; Chua, P.C.; O’Brien, S.E.; Siddiqui-Jain, A.; Bourbon, P.; Haddach, M.; Michaux, J.; Nagasawa, J.; Schwaebe, M.K.; Stefan, E.; et al. Discovery and SAR of 5-(3-Chlorophenylamino)Benzo[c][2,6]Naphthyridine-8-Carboxylic Acid (CX-4945), the First Clinical Stage Inhibitor of Protein Kinase CK2 for the Treatment of Cancer. J Med Chem 2011, 54, 635–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanin, S.; Sandre, M.; Cozza, G.; Ottaviani, D.; Marin, O.; Pinna, L.A.; Ruzzene, M. Chimeric Peptides as Modulators of CK2-Dependent Signaling: Mechanism of Action and off-Target Effects. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015, 1854, 1694–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perea, S.E.; Baladrón, I.; Valenzuela, C.; Perera, Y. CIGB-300: A Peptide-Based Drug That Impairs the Protein Kinase CK2-Mediated Phosphorylation. Semin Oncol 2018, 45, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, G.V.; Rosales, M.; Ramón, A.C.; Rodríguez-Ulloa, A.; Besada, V.; González, L.J.; Aguilar, D.; Vázquez-Blomquist, D.; Falcón, V.; Caballero, E.; et al. CIGB-300 Anticancer Peptide Differentially Interacts with CK2 Subunits and Regulates Specific Signaling Mediators in a Highly Sensitive Large Cell Lung Carcinoma Cell Model. Biomedicines 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirigliano, S.M.; Díaz Bessone, M.I.; Berardi, D.E.; Flumian, C.; Bal de Kier Joffé, E.D.; Perea, S.E.; Farina, H.G.; Todaro, L.B.; Urtreger, A.J. The Synthetic Peptide CIGB-300 Modulates CK2-Dependent Signaling Pathways Affecting the Survival and Chemoresistance of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cell Lines. Cancer Cell Int 2017, 17, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarduy, M.R.; García, I.; Coca, M.A.; Perera, A.; Torres, L.A.; Valenzuela, C.M.; Baladrón, I.; Solares, M.; Reyes, V.; Hernández, I.; et al. Optimizing CIGB-300 Intralesional Delivery in Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer. Br J Cancer 2015, 112, 1636–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Blomquist, D.; Ramón, A.C.; Rosales, M.; Pérez, G.V.; Rosales, A.; Palenzuela, D.; Perera, Y.; Perea, S.E. Gene Expression Profiling Unveils the Temporal Dynamics of CIGB-300-Regulated Transcriptome in AML Cell Lines. BMC Genomics 2023, 24, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, D.; Gao, W.; Hu, H.; Zhou, S. Why 90% of Clinical Drug Development Fails and How to Improve It? Acta Pharm Sin B 2022, 12, 3049–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauro Salvi; Sarno, S.; Cesaro, L.; Nakamura, H.; Pinna, L.A. Extraordinary Pleiotropy of Protein Kinase CK2 Revealed by Weblogo Phosphoproteome Analysis. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 2009, 1793, 847–859. [CrossRef]

- Chojnowski, J.E.; McMillan, E.A.; Strochlic, T.I. Identification of Novel CK2 Kinase Substrates Using a Versatile Biochemical Approach. Journal of visualized experiments 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyenis, L.; Menyhart, D.; Cruise, E.S.; Jurcic, K.; Roffey, S.E.; Chai, D.B.; Trifoi, F.; Fess, S.R.; Desormeaux, P.J.; Núñez de Villavicencio Díaz, T.; et al. Chemical Genetic Validation of CSNK2 Substrates Using an Inhibitor-Resistant Mutant in Combination with Triple SILAC Quantitative Phosphoproteomics. Front Mol Biosci 2022, 9, 909711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

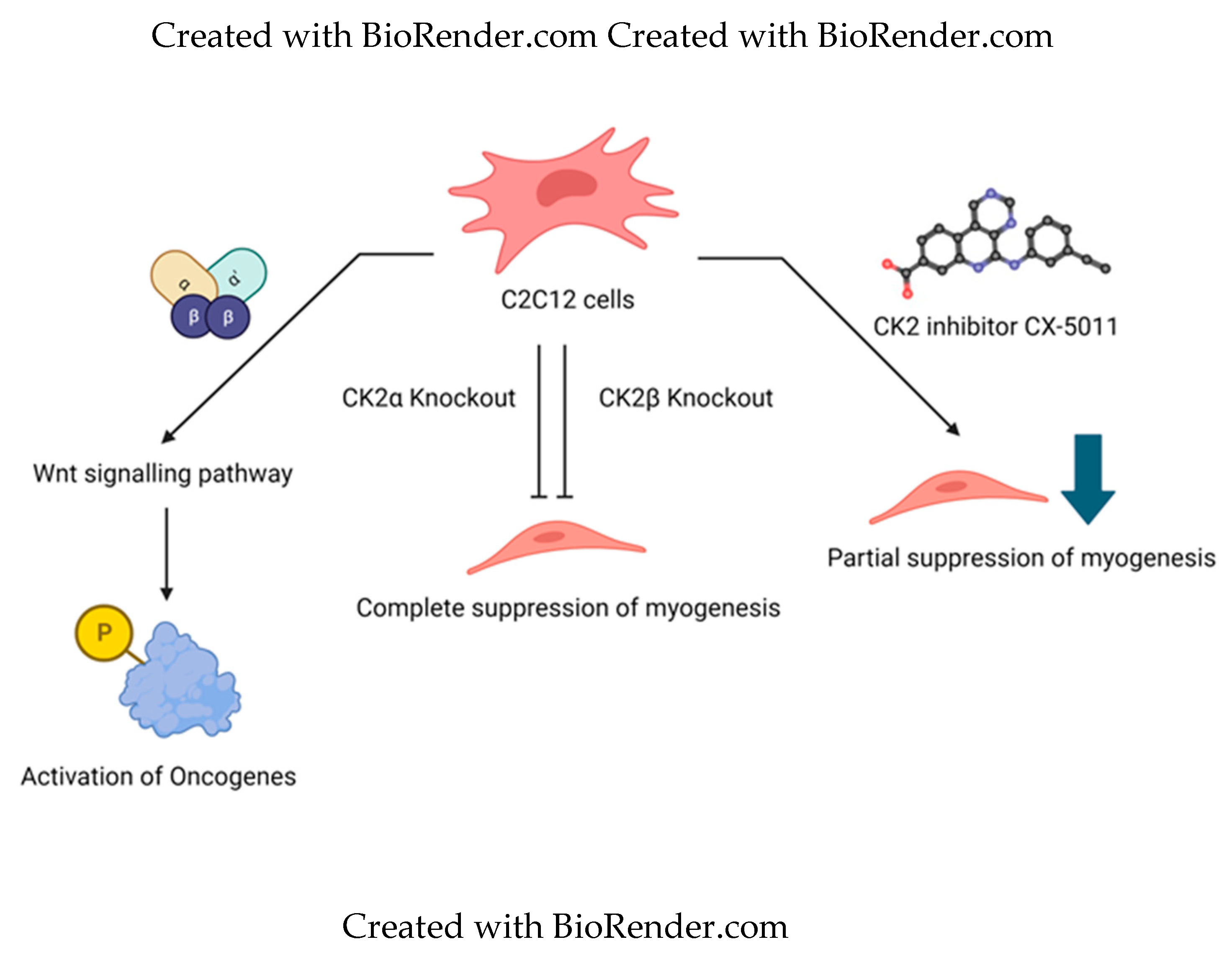

- Salizzato, V.; Zanin, S.; Borgo, C.; Lidron, E.; Salvi, M.; Rizzuto, R.; Pallafacchina, G.; Donella-Deana, A. Protein Kinase CK2 Subunits Exert Specific and Coordinated Functions in Skeletal Muscle Differentiation and Fusogenic Activity. FASEB J 10AD, 33, 10648–10667. [CrossRef]

- Merholz, M.; Jian, Y.; Wimberg, J.; Gessler, L.; Hashemolhosseini, S. In Skeletal Muscle Fibers, Protein Kinase Subunit CSNK2A1/CK2α Is Required for Proper Muscle Homeostasis and Structure and Function of Neuromuscular Junctions. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchin, C.; Borgo, C.; Cesaro, L.; Zaramella, S.; Vilardell, J.; Salvi, M.; Arrigoni, G.; Pinna, L.A. Re-Evaluation of Protein Kinase CK2 Pleiotropy: New Insights Provided by a Phosphoproteomics Analysis of CK2 Knockout Cells. Cell Mol Life Sci 2018, 75, 2011–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Choi, K.; Kang, H.; Lee, S.Y.; Chi, S.W.; Lee, M.S.; Song, J.; Im, D.; Choi, Y.; Cho, S. Identification of a Novel Function of CX-4945 as a Splicing Regulator. PLoS One 2014, 9, e94978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertsuwan, J.; Lertsuwan, K.; Sawasdichai, A.; Tasnawijitwong, N.; Lee, K.Y.; Kitchen, P.; Afford, S.; Gaston, K.; Jayaraman, P.S.; Satayavivad, J. CX-4945 Induces Methuosis in Cholangiocarcinoma Cell Lines by a CK2-Independent Mechanism. Cancers (Basel) 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, M.; Borgo, C.; Pinna, L.A.; Ruzzene, M. Targeting CK2 in Cancer: A Valuable Strategy or a Waste of Time? Cell Death Discov 2021, 7, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, G.; Gou, S. Novel CK2-Specific Pt(II) Compound Reverses Cisplatin-Induced Resistance by Inhibiting Cancer Cell Stemness and Suppressing DNA Damage Repair in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatments. J Med Chem 2021, 64, 4163–4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grygier, P.; Pustelny, K.; Nowak, J.; Golik, P.; Popowicz, G.M.; Plettenburg, O.; Dubin, G.; Menezes, F.; Czarna, A. Silmitasertib (CX-4945), a Clinically Used CK2-Kinase Inhibitor with Additional Effects on GSK3β and DYRK1A Kinases: A Structural Perspective. J Med Chem 2023, 66, 4009–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui-Jain, A.; Drygin, D.; Streiner, N.; Chua, P.; Pierre, F.; O’Brien, S.E.; Bliesath, J.; Omori, M.; Huser, N.; Ho, C.; et al. CX-4945, an Orally Bioavailable Selective Inhibitor of Protein Kinase CK2, Inhibits Prosurvival and Angiogenic Signaling and Exhibits Antitumor Efficacy. Cancer Res 2010, 70, 10288–10298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, A.D.; Sheth, P.R.; Basso, A.D.; Paliwal, S.; Gray, K.; Fischmann, T.O.; Le, H.V. Structural Basis of CX-4945 Binding to Human Protein Kinase CK2. FEBS Lett 2011, 585, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, M.A.; Meggio, F.; Ruzzene, M.; Andrzejewska, M.; Kazimierczuk, Z.; Pinna, L.A. 2-Dimethylamino-4,5,6,7-Tetrabromo-1H-Benzimidazole: A Novel Powerful and Selective Inhibitor of Protein Kinase CK2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004, 321, 1040–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, H.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, S.K. Emodin, an Anthraquinone Derivative Isolated from the Rhizomes of Rheum Palmatum, Selectively Inhibits the Activity of Casein Kinase II as a Competitive Inhibitor. Planta Med 1999, 65, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Huang, S.L.; Dou, W.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J.H.; Shen, Y.; Shen, J.H.; Leng, Y. Emodin, a Natural Product, Selectively Inhibits 11beta-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase Type 1 and Ameliorates Metabolic Disorder in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Br J Pharmacol 2010, 161, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarno, S.; Moro, S.; Meggio, F.; Zagotto, G.; Dal Ben, D.; Ghisellini, P.; Battistutta, R.; Zanotti, G.; Pinna, L.A. Toward the Rational Design of Protein Kinase Casein Kinase-2 Inhibitors. Pharmacol Ther 2002, 93, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozza, G.; Mazzorana, M.; Papinutto, E.; Bain, J.; Elliott, M.; di Maira, G.; Gianoncelli, A.; Pagano, M.A.; Sarno, S.; Ruzzene, M.; et al. Quinalizarin as a Potent, Selective and Cell-Permeable Inhibitor of Protein Kinase CK2. Biochem J 2009, 421, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, A.N.; Debreczeni, J.E.; Fedorov, O.Y.; Nelson, A.; Marsden, B.D.; Knapp, S. Structural Basis of Inhibitor Specificity of the Human Protooncogene Proviral Insertion Site in Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (PIM-1) Kinase. J Med Chem 2005, 48, 7604–7614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathison, C.J.N.; Chianelli, D.; Rucker, P.V.; Nelson, J.; Roland, J.; Huang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Xie, Y.F.; Epple, R.; et al. Efficacy and Tolerability of Pyrazolo[1,5-. ACS Med Chem Lett 2020, 11, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, D.; Baxter, B.; Campbell, B.C.V.; Carpenter, J.S.; Cognard, C.; Dippel, D.; Eesa, M.; Fischer, U.; Hausegger, K.; Hirsch, J.A.; et al. Multisociety Consensus Quality Improvement Revised Consensus Statement for Endovascular Therapy of Acute Ischemic Stroke. Int J Stroke 2018, 13, 612–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licciardello, M.P.; Workman, P. A New Chemical Probe Challenges the Broad Cancer Essentiality of CK2. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2021, 42, 313–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, C.I.; Drewry, D.H.; Pickett, J.E.; Tjaden, A.; Krämer, A.; Müller, S.; Gyenis, L.; Menyhart, D.; Litchfield, D.W.; Knapp, S.; et al. Development of a Potent and Selective Chemical Probe for the Pleiotropic Kinase CK2. Cell Chem Biol 2021, 28, 546–558.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.; Youn, H.; Gao, X.; Huang, B.; Zhou, F.; Li, B.; Han, H. Casein Kinase 2 Inhibition Attenuates Androgen Receptor Function and Cell Proliferation in Prostate Cancer Cells. Prostate 2012, 72, 1423–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, A.G.; Bdzhola, V.G.; Kyshenia, Y.V.; Sapelkin, V.M.; Prykhod’ko, A.O.; Kukharenko, O.P.; Ostrynska, O.V.; Yarmoluk, S.M. Structure-Based Discovery of Novel Flavonol Inhibitors of Human Protein Kinase CK2. Mol Cell Biochem 2011, 356, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, B.; Issinger, O.G. Protein Kinase CK2 in Human Diseases. Curr Med Chem 2008, 15, 1870–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meggio, F.; Pagano, M.A.; Moro, S.; Zagotto, G.; Ruzzene, M.; Sarno, S.; Cozza, G.; Bain, J.; Elliott, M.; Deana, A.D.; et al. Inhibition of Protein Kinase CK2 by Condensed Polyphenolic Derivatives. An in Vitro and in Vivo Study. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 12931–12936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilin, A.; Battistutta, R.; Bortolato, A.; Cozza, G.; Zanatta, S.; Poletto, G.; Mazzorana, M.; Zagotto, G.; Uriarte, E.; Guiotto, A.; et al. Coumarin as Attractive Casein Kinase 2 (CK2) Inhibitor Scaffold: An Integrate Approach to Elucidate the Putative Binding Motif and Explain Structure-Activity Relationships. J Med Chem 2008, 51, 752–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenblatt, D.; Applegate, V.; Nickelsen, A.; Klußmann, M.; Neundorf, I.; Götz, C.; Jose, J.; Niefind, K. Molecular Plasticity of Crystalline CK2α’ Leads to KN2, a Bivalent Inhibitor of Protein Kinase CK2 with Extraordinary Selectivity. J Med Chem 2022, 65, 1302–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brear, P.; De Fusco, C.; Hadje Georgiou, K.; Francis-Newton, N.J.; Stubbs, C.J.; Sore, H.F.; Venkitaraman, A.R.; Abell, C.; Spring, D.R.; Hyvönen, M. Specific Inhibition of CK2α from an Anchor Outside the Active Site. Chem Sci 2016, 7, 6839–6845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iegre, J.; Brear, P.; De Fusco, C.; Yoshida, M.; Mitchell, S.L.; Rossmann, M.; Carro, L.; Sore, H.F.; Hyvönen, M.; Spring, D.R. Second-Generation CK2α Inhibitors Targeting the αD Pocket. Chem Sci 2018, 9, 3041–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, C.; Wang, D.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, N. Recent Advances in the Discovery of CK2 Allosteric Inhibitors: From Traditional Screening to Structure-Based Design. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshima, T.; Niwa, Y.; Kuwata, K.; Srivastava, A.; Hyoda, T.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Kumagai, M.; Tsuyuguchi, M.; Tamaru, T.; Sugiyama, A.; et al. Cell-Based Screen Identifies a New Potent and Highly Selective CK2 Inhibitor for Modulation of Circadian Rhythms and Cancer Cell Growth. Sci Adv 2019, 5, eaau9060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgo, C.; Ruzzene, M. Protein Kinase CK2 Inhibition as a Pharmacological Strategy. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol 2021, 124, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Cao, S.; Zhang, J. Strategies of Targeting CK2 in Drug Discovery: Challenges, Opportunities, and Emerging Prospects. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 2257–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, H.G.; Benavent Acero, F.; Perera, Y.; Rodríguez, A.; Perea, S.E.; Castro, B.A.; Gomez, R.; Alonso, D.F.; Gomez, D.E. CIGB-300, a Proapoptotic Peptide, Inhibits Angiogenesis in Vitro and in Vivo. Exp Cell Res 2011, 317, 1677–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tang, P.; Zou, L.; Chen, J.; Yang, C.; He, G.; Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Chiang, C.M.; Wang, G.; et al. Discovery of Novel Dual-Target Inhibitor of Bromodomain-Containing Protein 4/Casein Kinase 2 Inducing Apoptosis and Autophagy-Associated Cell Death for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Therapy. J Med Chem 2021, 64, 18025–18053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Cao, S.; Zhang, J. Strategies of Targeting CK2 in Drug Discovery: Challenges, Opportunities, and Emerging Prospects. J Med Chem 2023, 66, 2257–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Ramos, M.; Prudent, R.; Moucadel, V.; Sautel, C.F.; Barette, C.; Lafanechère, L.; Mouawad, L.; Grierson, D.; Schmidt, F.; Florent, J.C.; et al. New Potent Dual Inhibitors of CK2 and Pim Kinases: Discovery and Structural Insights. FASEB J 2010, 24, 3171–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarno, S.; Mazzorana, M.; Traynor, R.; Ruzzene, M.; Cozza, G.; Pagano, M.A.; Meggio, F.; Zagotto, G.; Battistutta, R.; Pinna, L.A. Structural Features Underlying the Selectivity of the Kinase Inhibitors NBC and dNBC: Role of a Nitro Group That Discriminates between CK2 and DYRK1A. Cell Mol Life Sci 2012, 69, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukowska-Chojnacka, E.; Wińska, P.; Wielechowska, M.; Poprzeczko, M.; Bretner, M. Synthesis of Novel Polybrominated Benzimidazole Derivatives-Potential CK2 Inhibitors with Anticancer and Proapoptotic Activity. Bioorg Med Chem 2016, 24, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morooka, S.; Hoshina, M.; Kii, I.; Okabe, T.; Kojima, H.; Inoue, N.; Okuno, Y.; Denawa, M.; Yoshida, S.; Fukuhara, J.; et al. Identification of a Dual Inhibitor of SRPK1 and CK2 That Attenuates Pathological Angiogenesis of Macular Degeneration in Mice. Mol Pharmacol 2015, 88, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Padgaonkar, A.A.; Baker, S.J.; Cosenza, S.C.; Rechkoblit, O.; Subbaiah, D.R.C.V.; Domingo-Domenech, J.; Bartkowski, A.; Port, E.R.; Aggarwal, A.K.; et al. Simultaneous CK2/TNIK/DYRK1 Inhibition by 108600 Suppresses Triple Negative Breast Cancer Stem Cells and Chemotherapy-Resistant Disease. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zien, P.; Duncan, J.S.; Skierski, J.; Bretner, M.; Litchfield, D.W.; Shugar, D. Tetrabromobenzotriazole (TBBt) and Tetrabromobenzimidazole (TBBz) as Selective Inhibitors of Protein Kinase CK2: Evaluation of Their Effects on Cells and Different Molecular Forms of Human CK2. Biochim Biophys Acta 2005, 1754, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, J.H.; Yu, H.C.; Nam, S.; Kim, D.C.; Lee, J.H. Casein Kinase 2 Alpha Inhibition Protects against Sepsis-Induced Acute Kidney Injury. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitta, R.T.; Gholamin, S.; Feroze, A.H.; Agarwal, M.; Cheshier, S.H.; Mitra, S.S.; Li, G. Casein Kinase 2α Regulates Glioblastoma Brain Tumor-Initiating Cell Growth through the β-Catenin Pathway. Oncogene 2015, 34, 3688–3699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

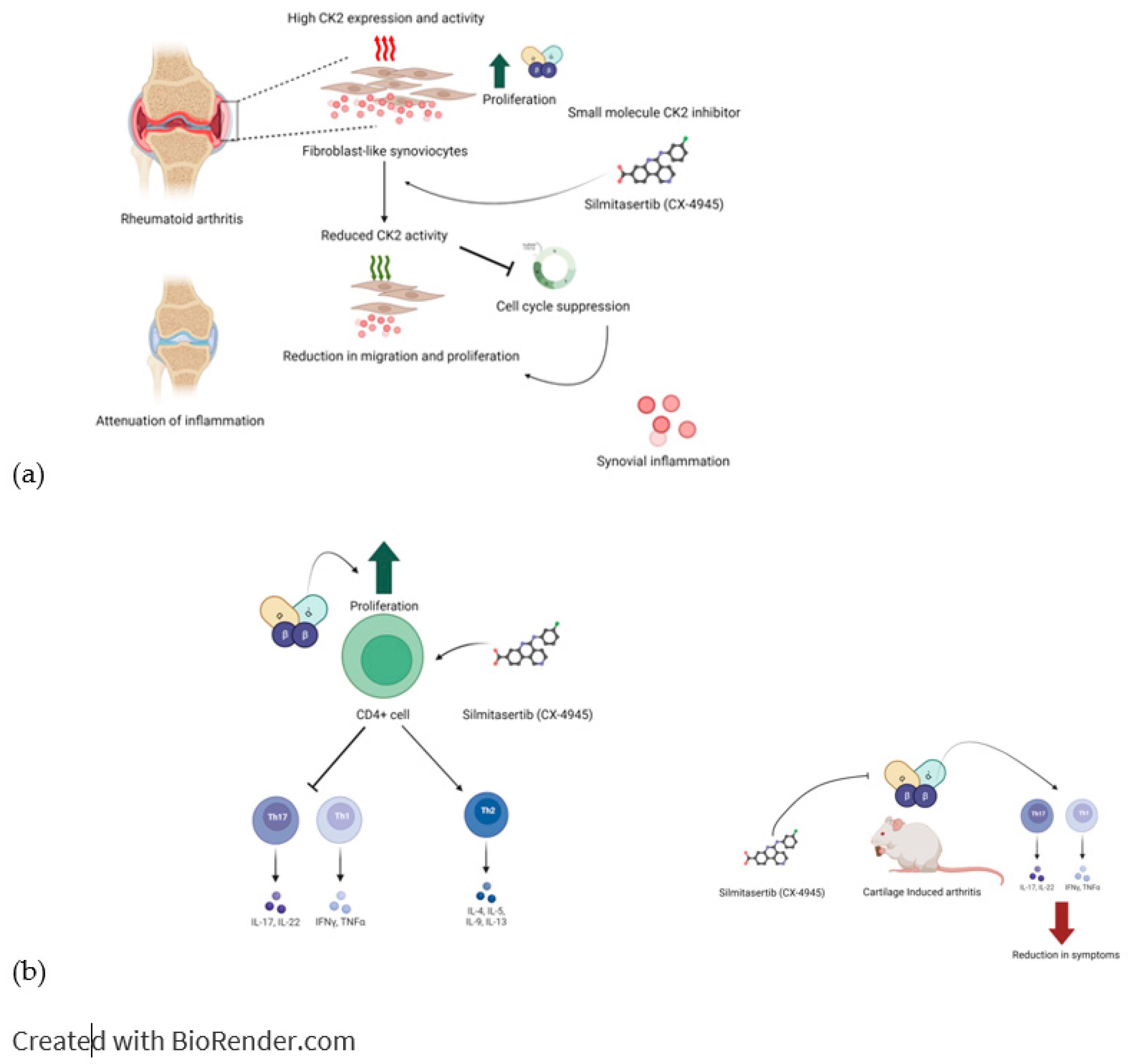

- Ye, H.; Fu, D.; Fang, X.; Xie, Y.; Zheng, X.; Fan, W.; Hu, F.; Li, Z. Casein Kinase II Exacerbates Rheumatoid Arthritis via Promoting Th1 and Th17 Cell Inflammatory Responses. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2021, 25, 1017–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Lei, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, H.; Guo, Z.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Xi, Y.; Peng, X.; et al. CX-4945 Inhibits Fibroblast-like Synoviocytes Functions through the CK2-P53 Axis to Reduce Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Severity. Int Immunopharmacol 2023, 119, 110163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okoumassoun, L.E.; Russo, C.; Denizeau, F.; Averill-Bates, D.; Henderson, J.E. Parathyroid Hormone-Related Protein (PTHrP) Inhibits Mitochondrial-Dependent Apoptosis through CK2. J Cell Physiol 2007, 212, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Rho, J.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Yoo, S.H.; Kim, H.Y.; Chung, W.T.; Yoo, Y.H. Alpha B-Crystallin Protects Rat Articular Chondrocytes against Casein Kinase II Inhibition-Induced Apoptosis. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0166450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.M.; Song, J.D.; Chung, H.T.; Park, Y.C. Protein Kinase CK2 Mediates Peroxynitrite-Induced Heme Oxygenase-1 Expression in Articular Chondrocytes. Int J Mol Med 2012, 29, 1039–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.M.; Sohn, D.H.; Kim, K.; Park, Y.C. Inhibition of Protein Kinase CK2 Facilitates Cellular Senescence by Inhibiting the Expression of HO-1 in Articular Chondrocytes. Int J Mol Med 2019, 43, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Liu, L.; He, F.; Fu, X.; Han, W.; Zhang, L. CKIP-1: A Scaffold Protein and Potential Therapeutic Target Integrating Multiple Signaling Pathways and Physiological Functions. Ageing Research Reviews 2013, 12, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Zhang, L. Physiological Functions of CKIP-1: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapy Implications. Ageing Research Reviews 2019, 53, 100908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhou, H.; Wang, S.; He, C.; Chen, T.; Fang, M.; Li, S.; Kang, S.; Huang, X.; et al. The Effect of QiangGuYin on Osteoporosis through the AKT/mTOR/Autophagy Signaling Pathway Mediated by CKIP-1. Aging (Albany NY) 2022, 14, 892–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Wu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, G.; Pan, X. The Role of CKIP-1 in Osteoporosis Development and Treatment. Bone & Joint Research 2018, 7, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P.-L.; Cui, A.-Y.; Hsu, C.-J.; Peng, R.; Jiang, N.; Xu, X.-H.; Ma, Y.-G.; Liu, D.; Lu, H.-D. Global, Regional Prevalence, and Risk Factors of Osteoporosis According to the World Health Organization Diagnostic Criteria: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Osteoporos Int 2022, 33, 2137–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lu, C.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Guo, B.; Li, D.; Liang, C.; Dang, L.; Pan, X.; et al. Targeting Osteoblastic Casein Kinase-2 Interacting Protein-1 to Enhance Smad-Dependent BMP Signaling and Reverse Bone Formation Reduction in Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 41295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

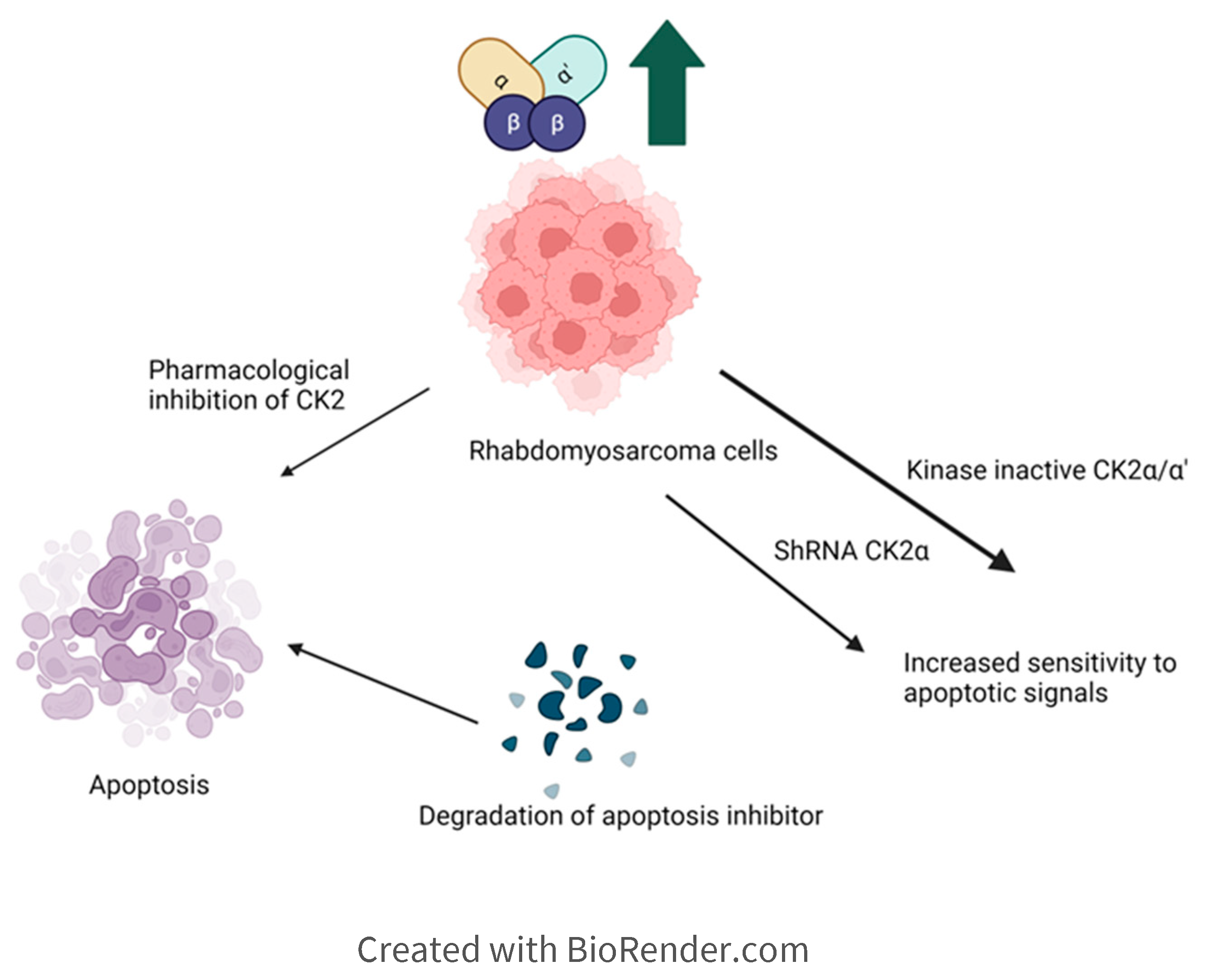

- Izeradjene, K.; Douglas, L.; Delaney, A.; Houghton, J.A. Influence of Casein Kinase II in Tumor Necrosis Factor-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand-Induced Apoptosis in Human Rhabdomyosarcoma Cells. Clinical Cancer Research 2004, 10, 6650–6660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Setoguchi, T.; Tsuru, A.; Saitoh, Y.; Nagano, S.; Ishidou, Y.; Maeda, S.; Furukawa, T.; Komiya, S. Inhibition of Casein Kinase 2 Prevents Growth of Human Osteosarcoma. Oncol Rep 2017, 37, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisberg, A.; Ellis, R.; Nicholson, K.; Moku, P.; Swarup, A.; Dhurjati, P.; Nohe, A. Mathematical Modeling of the Effects of CK2.3 on Mineralization in Osteoporotic Bone: Mathematical Modeling of the Effects of CK2.3. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol. 2017, 6, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkiraju, H.; Bonor, J.; Nohe, A. CK2.1, a Novel Peptide, Induces Articular Cartilage Formation in Vivo. J Orthop Res 4AD, 35, 876–885. [CrossRef]

- Akkiraju, H.; Srinivasan, P.P.; Xu, X.; Jia, X.; Safran, C.B.K.; Nohe, A. CK2.1, a Bone Morphogenetic Protein Receptor Type Ia Mimetic Peptide, Repairs Cartilage in Mice with Destabilized Medial Meniscus. Stem Cell Res Ther 04 18, 8, 82. [CrossRef]

- Halloran, D.; Pandit, V.; MacMurray, C.; Stone, V.; DeGeorge, K.; Eskander, M.; Root, D.; McTague, S.; Pelkey, H.; Nohe, A. Age-Related Low Bone Mineral Density in C57BL/6 Mice Is Reflective of Aberrant Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 Signaling Observed in Human Patients Diagnosed with Osteoporosis. IJMS 2022, 23, 11205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidner, H.; Yuan Gao, V.; Dibert, D.; McTague, S.; Eskander, M.; Duncan, R.; Wang, L.; Nohe, A. CK2.3, a Mimetic Peptide of the BMP Type I Receptor, Increases Activity in Osteoblasts over BMP2. IJMS 2019, 20, 5877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrathasha, V.; Weidner, H.; Nohe, A. Mechanism of CK2.3, a Novel Mimetic Peptide of Bone Morphogenetic Protein Receptor Type IA, Mediated Osteogenesis. IJMS 2019, 20, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Status for Clinical Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Silmitasertib (CX-4945) | The most selective CK2 inhibitor. Promotes apoptosis while inhibiting the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and the cell cycle progression. It has little toxicity. It is in Clinical use. | [54,55] |

| dimethylamino-4,5,6,7-1H-tetrabromobenzimidazole (DMAT) | Permeates cell membranes and induces apoptosis in the Jerkat cell line. | [29,56] |

| Emodin | It’s a natural anthraquinone derivative extracted from rhubarb. Inhibits CK2. | [57,58,59] |

| Quinalizarin | One of the most selective CK2 inhibitors. Polar interactions are established with CK2 in at least three hydroxyl groups. Inhibits CK2 and promotes apoptosis in HEK-293 and Jurkat cells. | [60] |

| IC20 | Extremely high selectivity for CK2alpha. It doesn’t show cytotoxicity in cancer cells. Binds at multiple sites with CK2. | [61] [62,63] |

| SGC-CK2-1 | High selectivity and cell-membrane permeable CK2 inhibitor. Used as a cellular probe to investigate how CK2 functions in the cell. It has little inhibitory effect on the proliferation of most cancer cells, and it is only effective against a small subset of cancer cells. | [64,65] |

| Tetrabromocinnamic Acid (TBCA) | Promotes apoptosis in Jurkat cancer cells. Suppresses platelet aggregation/secretion and the cell cycle progression in prostate cancer cells. | [66] |

| 4-(6,8-Dibromo-3-hydroxy-4-oxo-4H-chromo-2-yl)-benzoic acid (FLC26) | Mild increase in selectivity over the predecessor compound FLC21. Permeable to cell membranes and caused a significant increase in apoptosis in PANC-1 cells. | [67,68] |

| 3,8-dibromo-7-hydroxy-4-methylchromen-2-one (DBC) | Cell permeable and induces apoptosis in Jurkat cells. | [69,70] |

| CAM4066 | Poor cell membrane permeability. However, a synthetic methyl ester derivative, pro-CAM4066, increases its cell permeability, making it effective against cancerous tumors. Similar to KN2, but less selective and therefore less optimal as an inhibitor of CK2. Acts on the αD region and ATP-binding sites of CK2. The moiety bound to the ATP binding site forms a hydrogen bond with Lys68 and two water molecules. The moiety in the αD site interacts with Pro159 and a conserved water molecule. The linker forms a network of hydrogen bonds. | [71,72,73] |

| CAM4712 | Has high cell permeability and anti-proliferation effects. | [74,73] |

| GO289 | High selectivity for CK2, with little inhibitory effect on other kinases. Extremely selective, ideal for clinical use. Inhibition of the phosphorylation sites of multiple clock proteins and suppressed the growth/proliferation of cells of a diverse array of cancers. CK2α and CK2α′ are the primary targets of. | [75] |

| HY1-Pt | Derived from CX-4945. Extremely high selectivity, ideal for clinical use. Reversed cisplatin-induced drug resistance. Suppresses DNA damage repair in cancer cells. It also inhibited the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway while activating the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. Displayed no toxicity to healthy hepatocytes and could be used as a therapeutic for NSCLC. | [52] |

| Name | Status for Clinical Applica-tion | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| CIGB-300 |

Cell-permeable. Inhibits angiogenesis and metastasis. Used in early clinical trials in combination with chemoradiotherapy as a therapeutic against cervical cancer. Administered by injection into the tumor. Targets the phosphoacceptor domain. Releases histamine from the cells, possibly due to higher intracellular calcium levels in the cell. | [37] |

| 4,5,6,7-tetrabromobenzotriazole (TBBt) | Moderately effective as an anti-cancer drug. Induces apoptosis in tumor cells. Inhibits CK2α subunit. Used in Sepsis-Induced Acute Kidney Injury. | [86,87] |

| 4,5,6,7-tetrabromobenzimidazole (TBBz) | Able to target specific molecular forms of CK2. It is more effective in inducing apoptosis and necrosis in tumor cells compared to TBBt. Inhibits CK2α subunit activity. Tested in Glioblastoma Cell lines. | [86,88] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).